1. Introduction

Currently, more than one billion people worldwide, or about 15% of the population, are affected by some kind of disability, and the number of people with various dysfunctions is increasing due to ageing populations and better diagnosis as well as assessment systems [1]. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2], adopted in 2006 by the United Nations and ratified by all countries of the European Union, ensures the full inclusion of people from this group by increasing their participation in public spaces, including improved accessibility to various leisure activities. Accessible tourism is becoming increasingly popular, with more and more attractions, hotels or restaurants declaring that they are open to people with disabilities.

Changes in the perception of disability and a growing awareness of the barriers faced by people with special needs have made accessibility of different spheres of life an increasingly important topic in the public debate, calling for the abandonment of discriminatory practices against any group of people who differ in any respect from the general public and for assistance to integrate them [3]. The increase in the number of people who are officially recognised as having a disability is an important signal to politicians, planners and businesses to adapt spaces to their needs. Physical activity, which includes tourism, is extremely important for people with special needs [4]. In recent years, tourism has become an important way for people with disabilities to integrate and actively participate in society [5], moreover, tourism and recreation is one form of rehabilitation [6].

In the context of tourism, accessibility means providing equal opportunities to enjoy tourist services, which is important both in established tourist destinations such as Barcelona, Venice, Prague or Krakow in Poland [7,8], but also those that are less recognisable but have great tourist potential, of which the Świętokrzyskie region is an example.

2. Characteristics of the Study Area

The Świętokrzyskie region (

Figure 1) is distinguished by its unspoilt natural environment, varied landscape, extensive forest cover, numerous watercourses and interesting historical monuments, museums and relics. Particularly valuable here are the remains of former industrial plants and ancient technology sites, including the UNESCO-listed ‘Reserve Krzemionki’ - a striped flint mine from the Neolithic period. Among the many attractive towns in the region, historical cities such as Kielce, Opatów and Sandomierz stand out. Its potential attractiveness is evidenced by the presence of numerous natural attractions with the Świętokrzyski National Park located in some of the oldest mountains in Europe, covered in rocky debris. Nearly 51% of the region is under legal protection. A frequently visited attraction is the Raj cave with its rich dripstone formations. There are also two health resorts - Busko Zdrój and Solec Zdrój [9].

In terms of the percentage of area under protection and the number of historical monuments, the Świętokrzyskie Region is one of the richest areas in Poland in terms of natural and cultural assets.

However, the region is poor in comparison to other areas of Poland, its inhabitants have low incomes and its demographic structure is unfavourable. In this context, sustainable tourism has the potential to play a key role in supporting the local economy, strengthening employment and improving the quality of life of local communities. It is one of the most rarely visited regions in Poland by tourists. Therefore, promoting tourism diversity is a key element of the region’s sustainable tourism strategy. It assumes diversification of the tourist offer and creation of new tourism products based on experiences, as well as providing adequate space for people with disabilities. These activities can contribute to attracting new categories of tourists to the region. Promoting aspects of sustainability and ecology can attract tourists from abroad [10]. The accessibility of tourism facilities is important not only for people with disabilities, but also for their families, friends and carers, which in total constitutes a large group of potential tourists.

Inclusion is often seen as an indicator of a region’s overall level of social and civilisational development, which influences its image and perception as an attractive place for tourists. Inclusion of people with disabilities in tourism life has an economic dimension in addition to the social aspect [7,8], as it expands the potential customer base for local services and products. Research on the accessibility of tourism for people with disabilities is crucial not only from a social point of view, but also from an economic point of view. Creating a more inclusive tourism offer contributes to an increase in the number of tourists, which has a positive impact on the local economy.

3. Literature Review

A review of the literature indicates that there are numerous terminological controversies in the area of people with disabilities and the sphere of their inclusion in social and economic life.

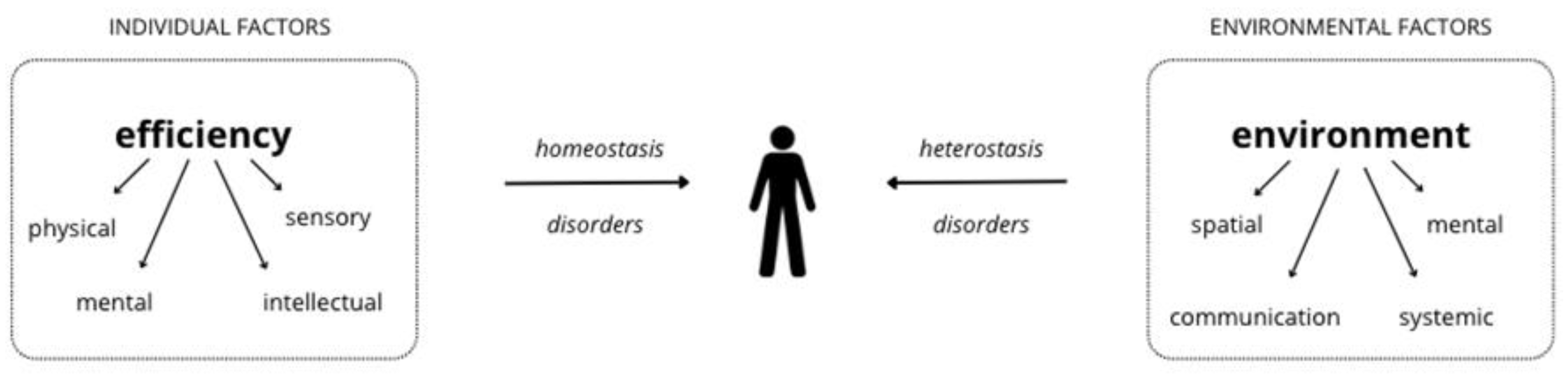

The concept of disability is socially constructed [11,12,13], and among the multitude of closely related words, words such as disability or handicap appear, which have a pejorative tinge and allow a negative social attitude towards a person affected by disability. The elimination of these terms should be at the heart of the fight against exclusion and discrimination. Also the disability community demands to be referred to primarily by the term ‘person with a disability’, in order to emphasise that disability is one of the many special characteristics of a person and is a manifestation of human diversity [6]. At the same time, it is a complex concept influenced by both personal and environmental factors (

Figure 2).

From the preamble of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, it follows, inter alia, that ‘disability is an evolving concept and (...) results from the interaction between persons with dysfunctions and the human and environmental attitudinal barriers that impede their full and effective participation in society, on an equal basis with others’ [14].

It is extremely important to consider the limited bodily capacity that determines disability together with the conditions of the environment in which the person functions. The relational nature indicates that it is possible to improve the functioning of people with disabilities when changes are made to the environment, which involves the removal of barriers. At the same time, it should be emphasised that persons with disabilities have the same needs as persons without disabilities [15], and therefore every democratic state should strive for social cohesion and minimisation of inequalities by ensuring unrestricted access to public and commercial services, provided by the private sector, municipal and state entities [3]. Among these services is tourism, which is widely accessible to people with disabilities in high quality of life countries such as the Netherlands, Canada, the UK and the Scandinavian countries. The ‘VisitEngland’ programme in the UK, for example, promotes accessible tourism by certifying disability-friendly destinations and creating a comprehensive database of such facilities [15].

The need for collaboration between stakeholders to enable people with different requirements - related to mobility, sight, hearing and cognitive dimensions - to function independently with dignity is pointed out by many works [16,17,18].

Such collaboration involves providing universally designed tourism products and services and providing universally designed access to spaces.

Research on accessible tourism addresses a variety of interrelated aspects related to travel, some of which are related to transport [17,18], availability of accommodation [19] and tourist attractions [7].It is also important for tour operators that people with disabilitiess often travel in the off-season, with at least one companion, and are willing to incur significant expenses for the trip. However, tourism for people with disabilities requires the creation of a special offer, profiled for different types of disabilities and the accessibility of attractions, accommodation facilities and infrastructure in the reception regions. An example of an analysis of accessibility for people with disabilities on a local scale is the development of accessible tourism offers on the Istrian peninsula in Croatia [20].

The COVID-19 pandemic period showed that the use of modern technology could effectively increase the accessibility of tourist attractions and especially museum facilities for people with disabilities. Smartphones with audio descriptors and the ability to directly translate texts into sign languages or online communication tools are just a few examples of the use of technology to increase accessibility [21]. These solutions have been used especially in museums, which were mostly closed during the pandemic due to sanitary restrictions [23].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Aim and Methods of the Study

The aim of this study is to assess the degree of accessibility of 20 flagship tourist attractions in the Świętokrzyskie region for people with mobility, sight and hearing impairments, and to propose actions to improve this accessibility. The developed recommendations for improving the accessibility of the tourist attractions and their management can be used in social policy as an important element of inclusion [11].

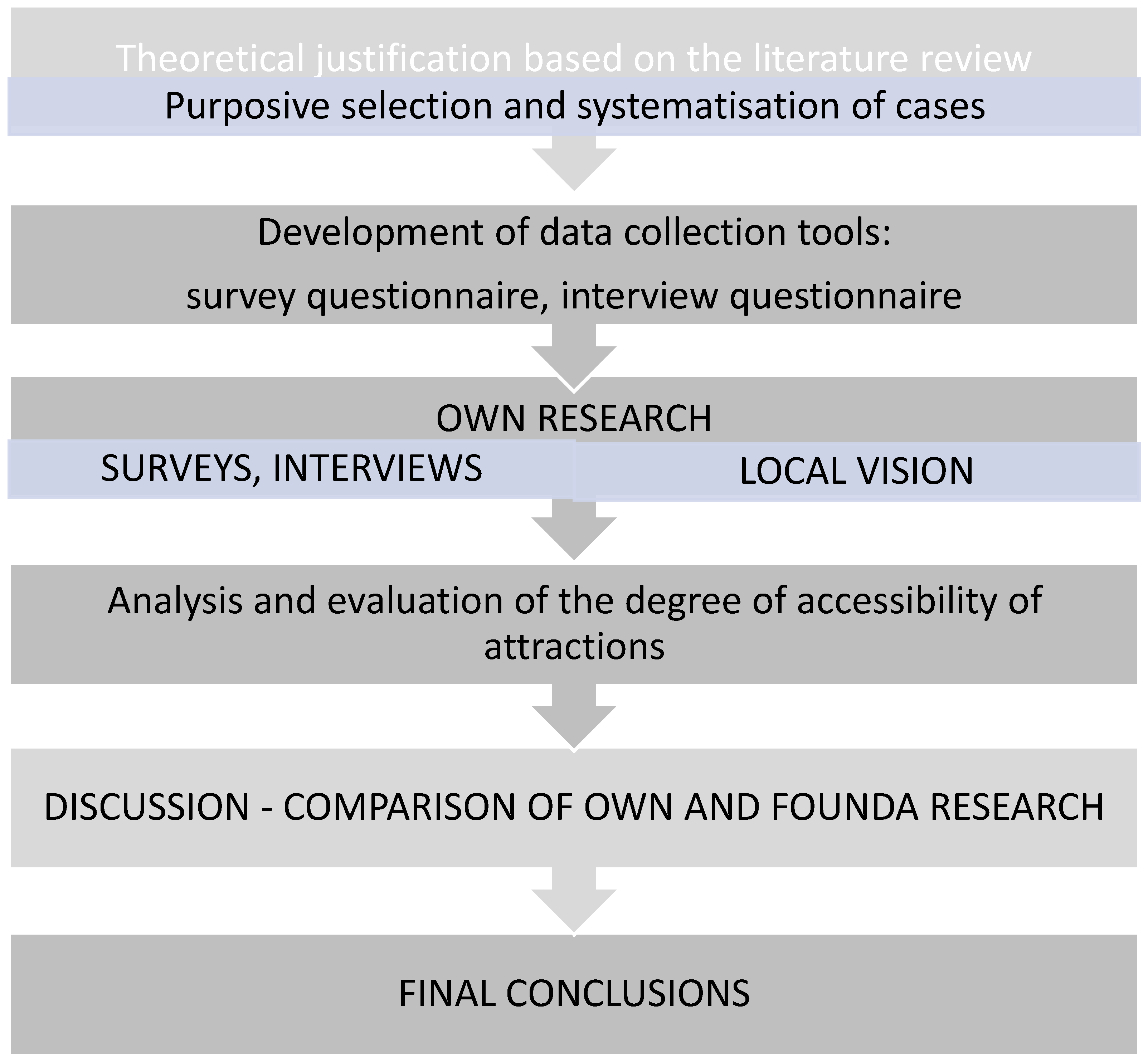

Figure 3 illustrates the general scheme of the research procedure.

Three research questions were also formulated:

Q1 - Are the main attractions of the Świętokrzyskie Region accessible to people with disabilities and for which types of disability facilities have been created,

Q2 - What is the degree of accessibility of attractions for people with disabilities,

Q3 - What actions are taken to improve the accessibility of tourist facilities for people with disabilities and social inclusion of people with disabilities.

4.2. Research Methods

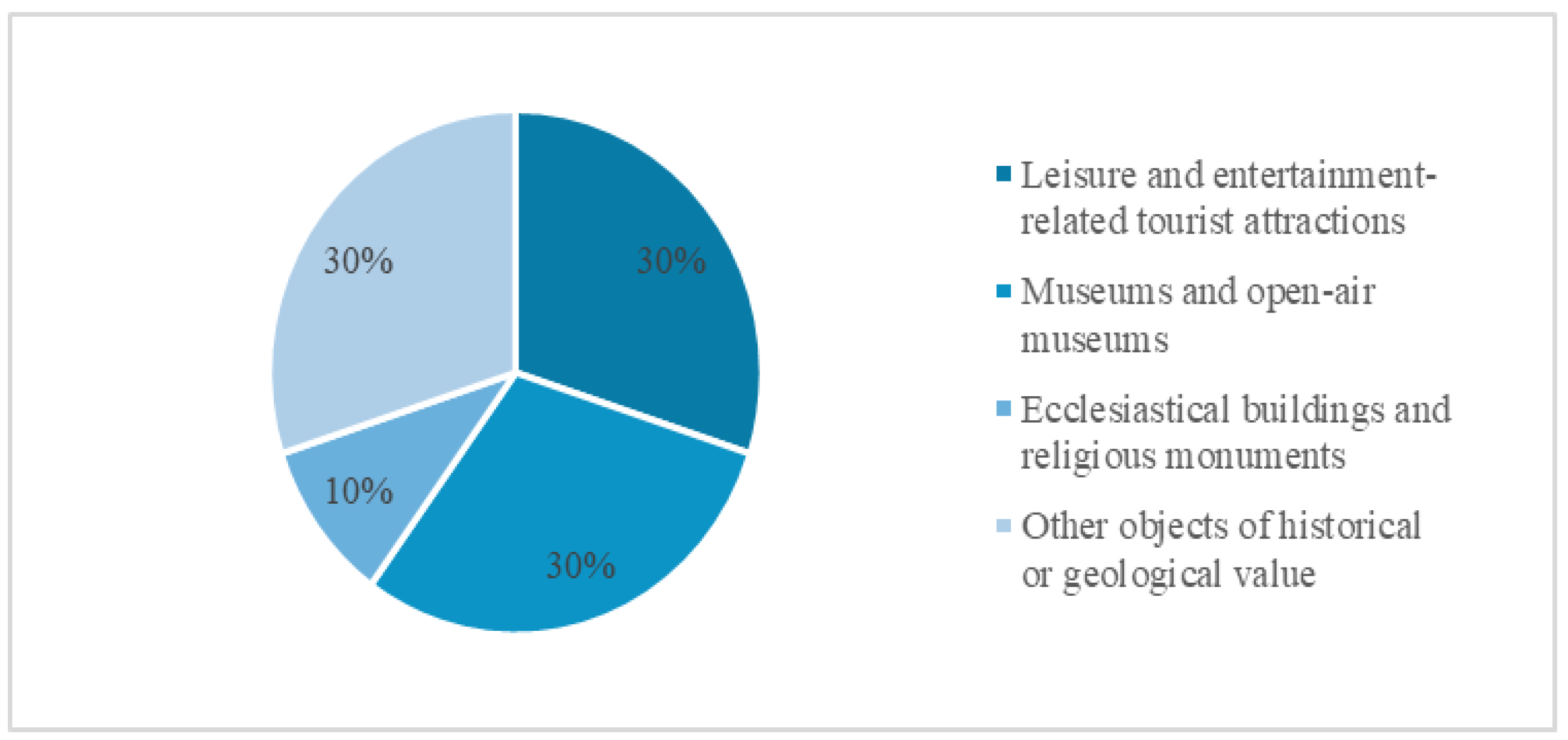

The research procedure consisted of eight steps. It began with an analysis of literature and internet sources related to the subject of the article. The scope of the research was limited to people with three types of disabilities, i.e., motor, sight and hearing. This was intentional, as more and more tourists with very different types of disabilities - wheelchair users, visually impaired, hearing impaired and deaf - can be found on tourist routes [5]. The selection of the twenty tourist attractions in the Świętokrzyskie region (

Figure 4) was also purposive and based on the report on attendance at tourist attractions in 2023 [22]. The selected attractions represented 4 different types of attractions:

1. leisure and entertainment facilities,

2. museums and open-air museums,

3. sacred sites,

4. historical and geological sites.

Their location in the region is illustrated in

Figure 4, and the percentage share in the studied set of attractions in

Figure 5.

The tools for data collection were survey and interview questionnaires modelled on other works on accessible tourism [7] and obtained from guides on accessibility standards for buildings for people with disabilities [23,24].

The questionnaire questions included the presence of adaptations in the facilities for selected disability groups and, in the absence of such adaptations, the reason for this and the plans related to increasing accessibility. Access to information and visitors’ interest in the accessibility of the facility for people with disabilities were also investigated. The survey, conducted in spring 2024, was oriented towards obtaining information from the managers of the various attractions through oral interviews.

In order to verify the accuracy of the completion of the questionnaires and to avoid the phenomenon of apparent adaptation [12], a site visit was carried out, confronting the answers obtained with the visitors’ own observations on site. In addition, photographs depicting typical facilities at the attractions analysed have been included to illustrate the ways in which facilities have been adapted for people with disabilities. Photographs can be both a source of data and a tool for data extraction, in our research they provide a document illustrating the state of adaptation of the attraction at the time the photograph was taken.

A 4-point quantitative scale was used to analyse the results of the study, which allowed us to assess the degree of accessibility of the attractions for people with disabilities on the basis of the audit [25]. A similar quantitative scale to that used in the evaluation of tourist attractions of Krakow [8] was used, with scores ranging from 0 to 3 points. An explanation of the criteria for awarding the individual scores is provided in

Table 1.

The number of points assigned was determined by the number and type of amenities at the facility, including the percentage of staff who are trained to cater for people with special needs and the adaptation of the website and/or the inclusion of accessibility information on the facilities. The auditors carried out an assessment of the impact of the inventoried facilities on ensuring the accessibility of the various attractions by assigning a value to each. On the scale adopted, 0 meant an object was completely unadapted for people with disabilities and 3 meant an object was fully or definitely adapted for people with the surveyed dysfunctions. Scale values of 1 and 2 indicate partial adaptation of the attraction (

Table 1).

5. Results of the Survey

5.1. Types of Facilities Used at Tourist Attractions

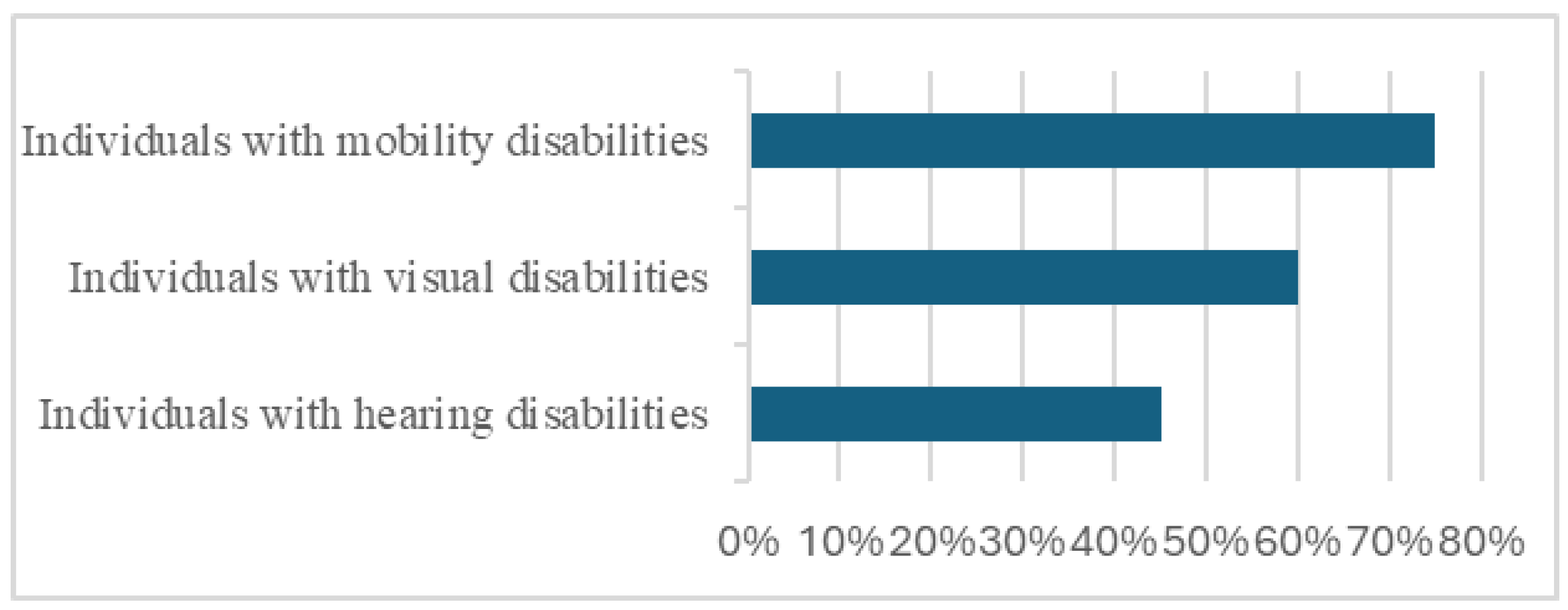

The main focus of the research was on the accessibility of the facilities at the facilities for the various groups with disabilities. The largest number, 15 sites (75%), have facilities for people who have mobility difficulties, 12 sites (60%) have located facilities for the blind and visually impaired, and nine attractions (45%) have adaptations for the deaf and hearing impaired (

Figure 6).

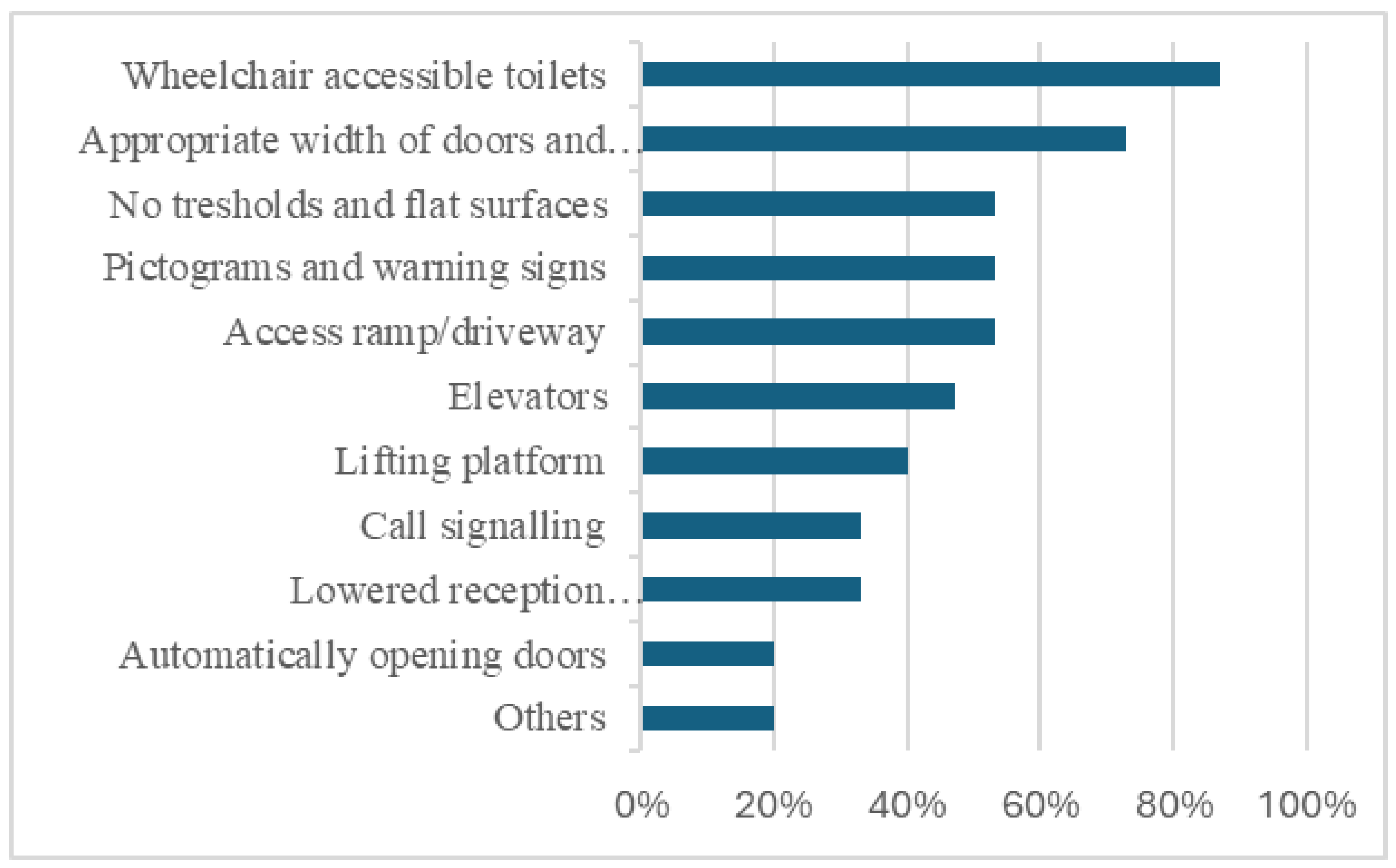

Among the facilities for people with mobility disabilities (

Figure 6), the presence of an adapted toilet and adequate width of corridors and doors were most frequently found. Flat surfaces, pictograms, access ramps and lifts are also common. Some attractions also have lifts, paging signals or lowered counters. Unfortunately, only 3 (20%) venues had automatic opening doors, and other adaptations included a so-called stairlift and specially adapted buses for wheelchair users.

Figure 7.

Amenities for people with mobility disabilities at selected attractions in Swietokrzyskie Voivodeship, n=15 (100%) (own study).

Figure 7.

Amenities for people with mobility disabilities at selected attractions in Swietokrzyskie Voivodeship, n=15 (100%) (own study).

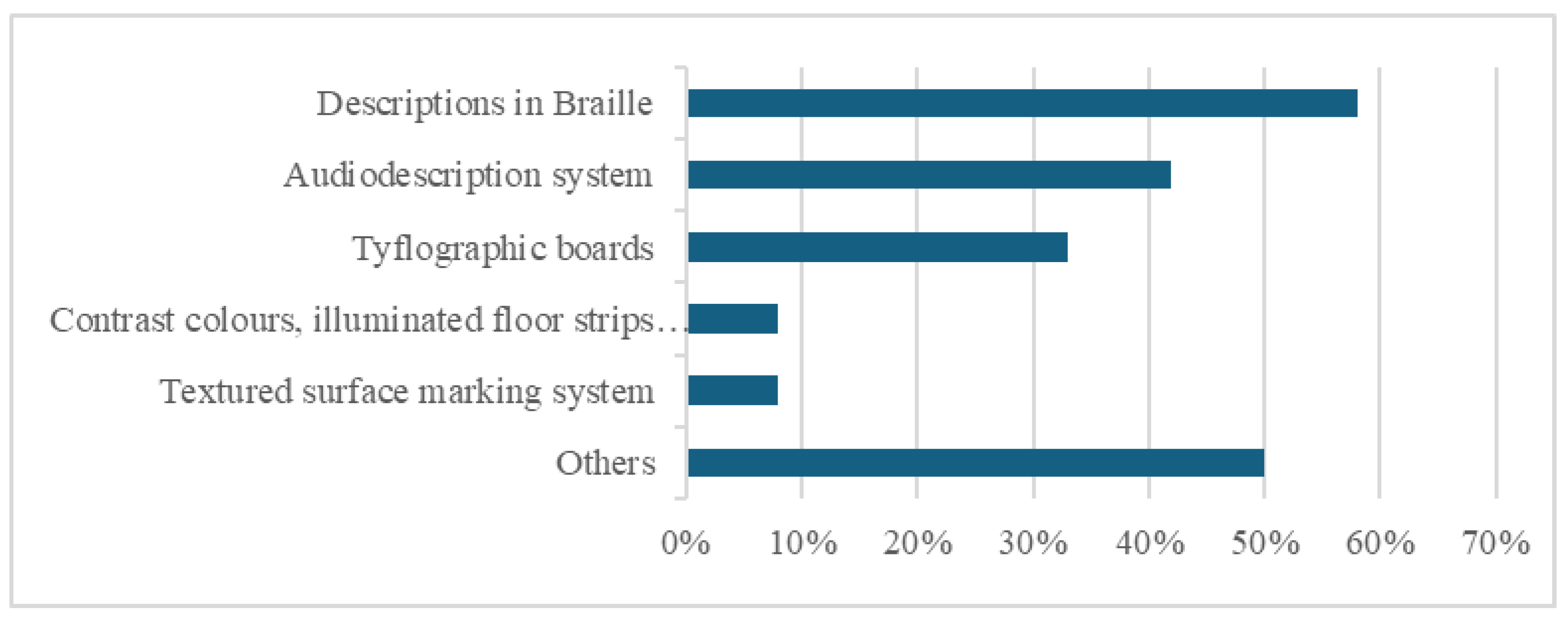

For the blind and visually impaired, the presence (

Figure 8) Braille descriptions and audiodescription systems, including the use of beacons. 4 (33%) of the attractions included tryflographic plans. Only 1 (8%) attraction chose to use contrasting colours and illuminate floor and ceiling mouldings. A textured surface signage system was also encountered once. An interesting solution was the use of information boards with QR codes.

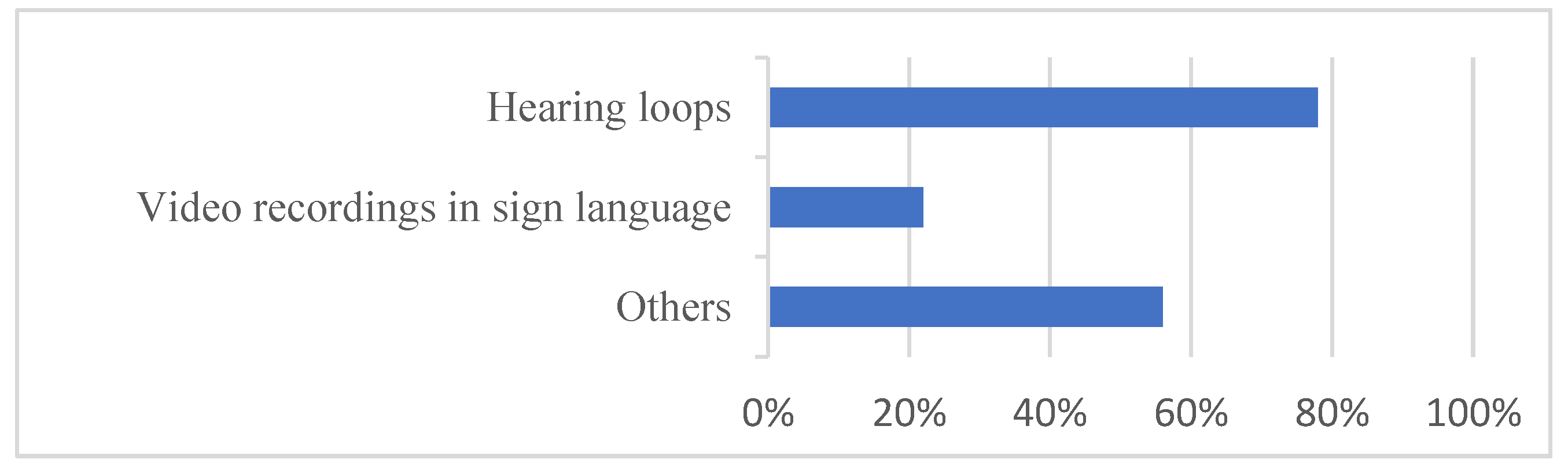

An induction loop for people with hearing difficulties (

Figure 9) has 7 (78%) facilities. In only 2 (22%) of the venues can we encounter video material in sign language. There are also videos with subtitles and the possibility to visit with a guide who speaks sign language or an interpreter is provided.

Most of the facilities surveyed have a designated parking area, including flat access to the pavement. A problematic issue is the low percentage of staff who are trained to deal with people with disabilities. Half of the staff are competent in this area in only 20% of the facilities. Each facility has its own website, 58% of which is adapted for use by people with special needs and 63% of which contains information on the accessibility of the facility for people with disabilities. Only 2 attractions have facilities for people with other types of disabilities, in the form of a so-called ‘blue zone’ and an educational offer adapted for audiences with intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorders.

According to the custodians, in 8 facilities the said amenities were already planned at the construction stage, and in 7 facilities modifications were necessary to introduce them. When asked about the reasons for not adapting the facility, the surveyed custodians most often indicated a financial barrier and the historic nature of the building, which requires the approval of the conservation officer. However, most of the attractions’ custodians declare that they want to be accessible and intend to make some effort to do so in the near future.

5.2. Assessment of the Adjustment of Attractions to the Needs of People with Disabilities in the Świętokrzyskie Region

Table 2 presents the previously mentioned division of selected tourist attractions of Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship into 4 categories and the results of the assessment of the degree of accessibility for the 3 groups with disabilities. The number of visitors to these attractions in 2023 is also given.

5.3. Attractions for Recreation and Entertainment

Six facilities were classified in the category related to leisure and entertainment. Of these, the best suited to accommodate all three groups of people with disabilities is the Koziołek Matołek European Tale Centre in Pacanów. This children’s cultural centre has been in operation since 2010 and consists of a main building with an outdoor garden and the ‘Fairy Tale Academy’ Educational Park. A dedicated parking area connects to the carefully designed circulation routes, which are of adequate width and have no thresholds (Photo 1).The mobility impaired can use several adapted toilets. A special lift is also installed in the main building. During guided tours, there can be one wheelchair user per group, unless accompanied by an assistant, in which case this limit does not apply.

An audioguide system is available during tours of the Fairy Tale World exhibition, upon prior notification of this need to staff. It is also possible to guide a blind person to a specific section. The centre has a website tailored to the needs of people with disabilities, which includes a switch to change the font size or alter the contrast. The website also includes a detailed accessibility statement. There are instructional videos on how to navigate the entire centre in sign language. Induction loops have also been installed on the site (Photo 12), but there is no possibility for guided tours in sign language.

The Mineral Pools in Solec-Zdrój are the only pools in Poland to use sulphurous healing water. The pools were opened in January 2013, so they are a modern investment. The sulphide brine, which is found in the Solec pools, has properties alleviating osteoarthritis and spinal diseases, analgesic, in addition to having a positive effect on the skin, making it more flexible. Due to the spa functions of this attraction, it has been adapted almost entirely for people with disabilities. There are ramps, lifts, toilets for people with disabilities, platforms and lifts, as well as automatically opening doors. Specially adapted changing rooms are planned. In contrast, there is a lack of adaptations for the blind and visually impaired as well as the deaf and hearing impaired.

In this category, the most popular attraction is the Bałtów Jura Park, opened in 2004, which after expansion covers an area of around 100 hectares and is the most diverse in terms of types of attractions in Poland. Smooth movement is facilitated by numerous ramps and appropriate marking. Only in a few places is the presence of a strong attendant desirable. Lowered checkout counters and adapted toilets are standard on the complex. A very interesting solution is to allow tourists to visit the Upper Zwierzyniec on board of an American schoolbus (Photo 2). Out of the seven vehicles available, one is wheelchair accessible and can accommodate five people with disabilities at a time. However, the facility does not have any adaptations aimed strictly at visually or hearing impaired visitors.

The Kadzielnia nature reserve has undergone revitalisation in recent years. The reserve has an amphitheatre, which regularly hosts cultural events (concerts, cabaret evenings) and an Underground Tourist Route, which can only be visited with a guide. A circular, flat trail runs through the reserve, which is adapted to the needs of people with impaired mobility - there are no stairs or other obstructions in the area, and a car park is provided that is adapted to their needs. Other facilities such as a toilet for people with disabilities are missing, and a section of the path is gravel, which can be a problem after heavy rainfall due to the unstable surface. The wheelchair learning track should be singled out. This is the implementation of the winning idea of the Kielce Civic Budget. The track allows wheelchair users to practise moving around in different conditions, as well as practising overcoming the obstacles they have to face in their everyday life [26]. Unfortunately, the facility is not adapted for visually and hearing impaired visitors. Despite assurances from the attraction’s operator about the presence of tiflographic signs and Braille descriptions, these could not be found during the verification visit.

In 2012, the Sabat Krajno Miniature Park was established at the foot of the Łysica Mountain which is an extensive leisure and entertainment complex. The park is partially adapted to the needs of people with impaired mobility. Flat paths, lowered counters, suitably adapted toilets and a stairlift enable tourists in a wheelchair to reach the furthest parts of the Miniature Park, as well as to enter the restaurant. Unfortunately, it is located on a hill and the steep slope when viewing the miniatures can be a problem for wheelchair users. The park has no adaptations for the blind and visually impaired, but some miniatures can be touched. The park has no adaptations for the deaf and hearing impaired.

The

graduation tower in Busko-Zdrój, built in 2020, is one of the largest and most modern brine graduation towers in Poland. Among all the facilities surveyed, it has by far the most comfortable, automatically opening doors and specially adapted gates (

Figure 3). On the first floor, there is an observation deck from where the panorama of the health resort can be enjoyed. However, it is inaccessible for people with mobility difficulties, as several stairs have to be climbed. These stairs are the only barrier, as once they have been climbed, for example with the help of a stairlift, the upper floor is fully accessible as it is flat and wide. The health house, with its pump room and year-round mini graduation tower and orangery, is accessible to people with mobility difficulties, as is the graduation tower’s surroundings in the form of park greenery. The facility does not have any facilities aimed at the blind and visually impaired or the deaf and hearing impaired.

5.4. Museums and Open-Air Museums

Museums and open-air museums is another category represented by six sites in the surveyed collective. It is worth noting that it is here that the only site from the Świętokrzyskie Region is located, which is the Krzemionki Prehistoric Striped Flint Mining Region, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019 [27]. The site has undergone refurbishment to make it more accessible to people with disabilities. It has many facilities for people who have mobility problems (Photo 5). Specially designated and signposted parking spaces, adapted toilet facilities, adjustment of the width of the exhibition halls. A special, shorter section of the underground tourist route has been dedicated to people in wheelchairs, which can be accessed by a lift located within the Zenon shaft. Visually impaired visitors have the opportunity to touch replicas of the monuments while visiting the permanent exhibition (Photo 8). Large print and Braille inscriptions have also been placed. This exhibition is also audio-visualised, using granular paint that can be felt underfoot. Multimedia kiosks present an expanded version of information about the exhibition. A guided tour of the site is only possible, but there is no sign language interpreter available and, despite the significant adaptation of the exhibitions in the main building, exploring the reserve in the open air and inside the mine is considerably difficult for people with sight and hearing difficulties.

The Kielce Countryside Museum is the Ethnographic Park in Tokarnia, founded in 1976. Its adaptation to the needs of people with mobility impairments was rated 2 points. There are toilets for people with disabilities, flat paths, a wide entrance and a car park with a pavement. A handicap is the single thresholds leading to some exhibits, which are an architectural barrier related to the original architectural design of the historic buildings. In addition, the uneven terrain can make it difficult to navigate in a wheelchair, especially during bad weather. However, it is possible to use ramps to access selected facilities.

This attraction is well adapted to the needs of visually impaired visitors, mainly due to the project ‘Adaptation of the offer of the Kielce Countryside Museum to the needs of the blind and visually impaired’, carried out in 2020. It has a number of facilities, such as Braille signs at every object in the park (Photo 10), signs on the toilets and ticket offices, and tri-fold guides available for free hire at the ticket office, which enable a blind person to learn the shape of the buildings depicted in the museum. In addition, a sensory chamber has been opened in the museum where replicas of the exhibits can be touched, and three types of dedicated educational activities have been introduced for blind and partially sighted people: In addition, staff have been trained to assist this group of customers. The museum is a little less well prepared for hearing impaired visitors, as the only item that can be mentioned here are miniature receivers together with earphones for the hearing impaired (DLR-01R) available ‘on request’. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the museum has a good website and a detailed accessibility statement.

Another flagship of the Świętokrzyskie Region is the Henryk Sienkiewicz Museum in Oblęgorek, the palace that the Nobel Prize-winning writer received as a gift from the nation in 1900. A ramp allows wheelchair users to access the ground floor, where there is also a toilet for people with disabilities. There are no architectural barriers on the ground floor. Unfortunately, the stairs to the first floor prevent people with mobility impairments from seeing the museum exhibition. An excellent audiodescription programme has been developed for visually impaired visitors ( Photo 9), and induction loops have been provided for people with hearing disabilities. In this museum, according to the auditors, the staff are by far the best prepared and trained to inform and assist people with disabilities.

The National Museum in Kielce is a multi-departmental institution with a 100-year tradition. Accessibility studies were carried out in the former Krakow Bishops’ Palace in Kielce. It is a residence with original 17th and 18th century interiors. The museum offers a number of facilities, such as adapted: lifts, toilets, a ramp and a staircase platform (Photo 6). This allows a person in a wheelchair to visit the Palace Interiors and the upper floor of the Gallery of Polish Painting and European Decorative Arts. The museum received only 1 point in the assessment of adaptation to the needs of the blind and visually impaired. Such a low score is due to the lack of Braille descriptions and other adaptations in the exhibition area, and only a single tyflographic board with a description adapted to the needs of this group of people, on the ground floor, near the ticket offices (Photo 7). For the hearing impaired, induction loops have been installed and sign language video material is available.

The Mieczysław Radwan Museum of Ancient Świętokrzyskie Metallurgy in Nowa Słupia was opened in 1960 to protect an archaeological site which reveals the relics of 45 bloomeries. The building has been extended several times and in 2016 was transformed into a modern facility with a number of adaptations for people with disabilities. This museum achieved the maximum rating for adaptations for people with mobility impairments, with wide corridors, a lowered counter in the reception area, lifts, toilets adapted to the needs of people with disabilities. A person in a wheelchair can reach any part of the museum. It is worth mentioning the adaptation of the website to the needs of the blind and visually impaired (special contrast adjustment, possibility to listen to the content of the website by a voiceover), and the deaf (valuable information). Within the museum, it is possible to borrow an audiodescription system, as well as listen to a voiceover describing the exhibition. Unfortunately, other adaptations are missing. The situation is similar with facilities for the hearing impaired and the deaf, where, apart from subtitles on the screened films, there are no other accommodations.

The Sandomierz Castle Museum, on the other hand, is not accessible to people with disabilities. However, it is worth noting that the museum’s manager is aware of the problem, an accessibility audit has recently been carried out and efforts are being made to obtain funding to adapt the facility for people with special needs from the European Funds for Infrastructure, Climate and Environment 2021-2027 programme.

5.5. Sacral Monuments

The research was conducted at two religious sites that are particularly popular with visitors. The Łysa Góra Monastery was visited by more than 320,000 people in 2023; the shrine has been an important centre of Christianity for many years. The site, due to its location and historical value, is not adapted for people with mobility impairments. A special parking space has been prepared, but there is no pavement, and the multitude of thresholds and stairs make it difficult for a person in a wheelchair to move around the monastery. Despite this, people with mobility impairments visit the sanctuary every day or several times a week. The staff is characterised by a great willingness to help and an empathetic approach to visitors, but this does not compensate for the lack of real adaptations. The facility does have some facilities for the blind and visually impaired - these include Braille boards and tylograph plans. It is worth mentioning the facility’s well-designed website, adapted to the needs of people with visual impairments. The facility does not have any adaptations for the deaf and hearing impaired.

Better adapted to the needs of people with disabilities is the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Sorrows Queen of Poland in Kalkowo-Godów. A person using a wheelchair can easily access the main parts, including the chapels and places of worship, thanks to an access ramp and flat surfaces. The surroundings of the sanctuary, which include the Stations of the Cross and the mini zoo, are also manageable for people with mobility problems. The three-storey building dedicated to Pope John Paul II, which hosts numerous cultural and religious events and provides accommodation for pilgrims, has a lift and a call sign. Unfortunately, one of the most important attractions, i.e., the Lourdes Grotto, is completely inaccessible to the disabled due to the numerous stairs. There are some Braille descriptions and induction loops for those with sight and hearing problems. The hosts of the site have declared that they do not intend to introduce any new facilities in the near future.

5.6. Other Historical and Geological Sites

The final category is made up of sites that do not fall into any of the previous three, but are undoubtedly a showpiece of the region. One that stands out is the Royal Castle in Chęciny, which was probably built at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries and now has the status of a ‘permanent ruin’. The facility is not suitable for visitors with mobility impairments. It is accessed by a series of steep stairs. It has one adaptation for the blind and visually impaired, which is QR codes (Photo 11). The QR codes, however, are not convex and are not guided by a system of textured surface badges, which can make it very difficult for a blind person to find the code. The facility does not have any adaptations for the deaf and hearing impaired.

The ruins of Krzyżtopór castle in Ujazd are the remains of one of the largest palace buildings in Europe, built between 1621 and 1644 before Versailles. Despite its historic nature, it has several facilities for the mobility impaired. Special parking spaces have been located right next to the ticket offices. The courtyard of the château is gravel but flat, and it is possible to move between levels by means of a lift and lift platform (Photo 4). An additional toilet has also been provided. Unfortunately, access to the basement has not been provided for people who are unable to climb the stairs themselves. This historical monument is not ready for the blind and visually impaired, and only an induction loop has been provided for those with hearing difficulties.

The Neolithic Settlement in Kopiec opened in 2020 and is well adapted in terms of accessibility for people with reduced mobility. As part of the project ‘Accessible Tourism in the Municipality of Iwaniska’, a number of measures have been taken to make the site friendly for all visitors. Special paths have been prepared for people with mobility impairments to move between the reconstructed buildings, and checkout counters and toilets have been adapted. For visually impaired visitors, the settlement offers guides to assist and support them, providing verbal descriptions of the exhibits and the opportunity to touch some of the objects for a fuller historical experience. The guides, however, are not prepared to work with deaf and hearing impaired visitors.

The Raj Cave, located in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, is one of the region’s best-known tourist attractions, even though it is a nature reserve with limited access. Tours take place in groups with a guide. Due to the nature of the cave environment - narrow corridors, high humidity and low temperatures - it is very difficult for people in wheelchairs. The only adaptation is the sanitary facilities. It was declared that a parking area is planned. There are no special assistive devices for the blind or visually impaired. The guides conduct the tour in narrated form, which can be a challenge for people who have a hearing impairment.

Two attractions located in Sandomierz were also included in this category - the Underground Tourist Route was under renovation during the audit and reaching the ticket offices was difficult. The attraction includes historic cellars, corridors and chambers up to 12 metres underground and is difficult to navigate for people with limited mobility due to numerous stairs, level differences and narrow passages and the lack of any facilities. There are no facilities for the blind or deaf. The Opatów Gate is also not adapted to any extent for the three disability groups surveyed. Visitors wishing to reach the ticket offices and information desk encounter an architectural barrier in the form of a steep staircase right from the start.

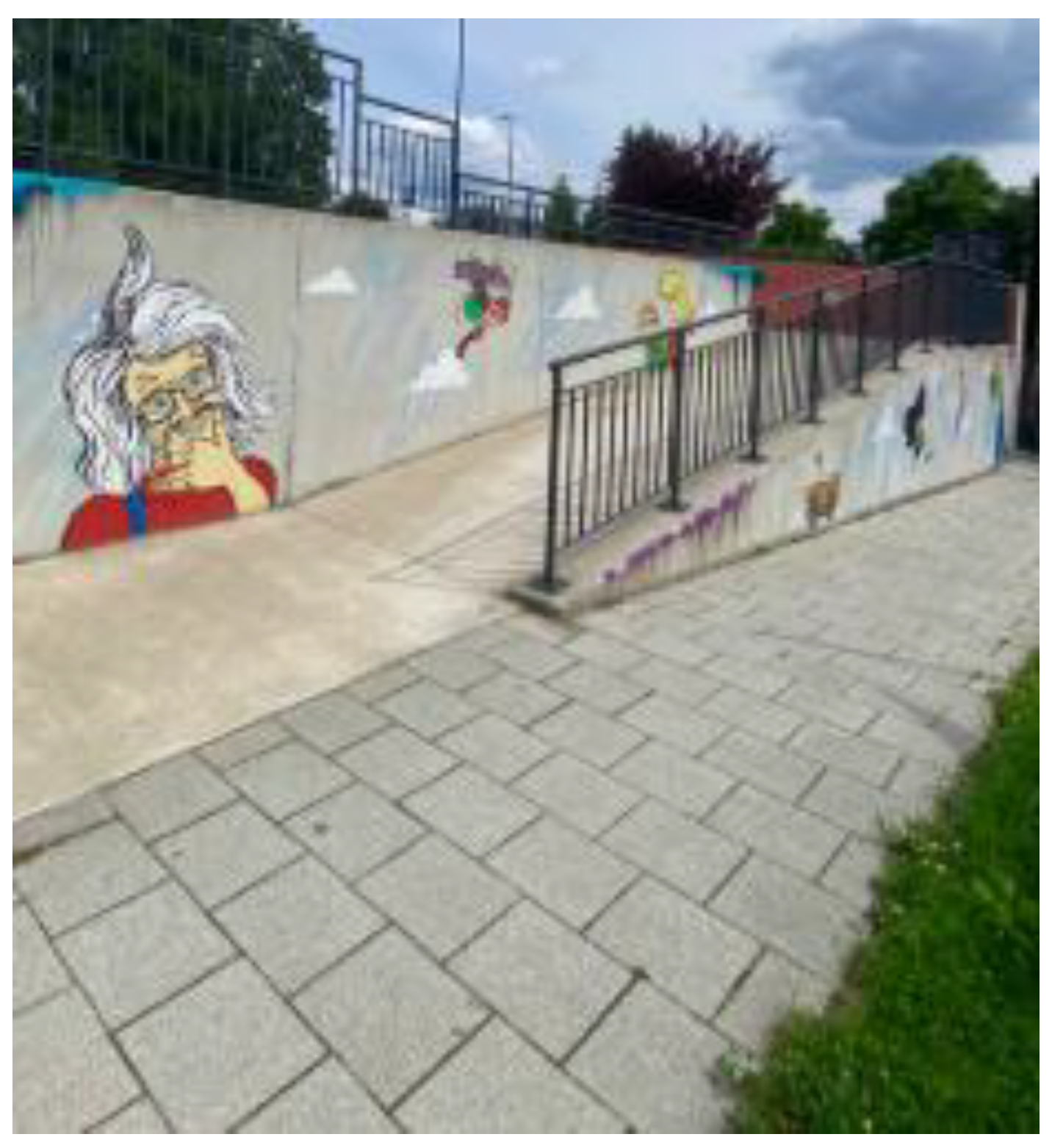

Photo 1.

Wheelchair ramps at the Koziołek Matołek European Tale Centre in Pacanów (photo. K. Chwaja).

Photo 1.

Wheelchair ramps at the Koziołek Matołek European Tale Centre in Pacanów (photo. K. Chwaja).

Photo 2.

Wheelchair accessible bus at the JuraPark in Bałtów (photo B. Chwaja).

Photo 2.

Wheelchair accessible bus at the JuraPark in Bałtów (photo B. Chwaja).

Photo 3.

Specially adapted, wide entrance gates at the Graduation Tower in Busk-Zdrój (photo. K. Chwaja).

Photo 3.

Specially adapted, wide entrance gates at the Graduation Tower in Busk-Zdrój (photo. K. Chwaja).

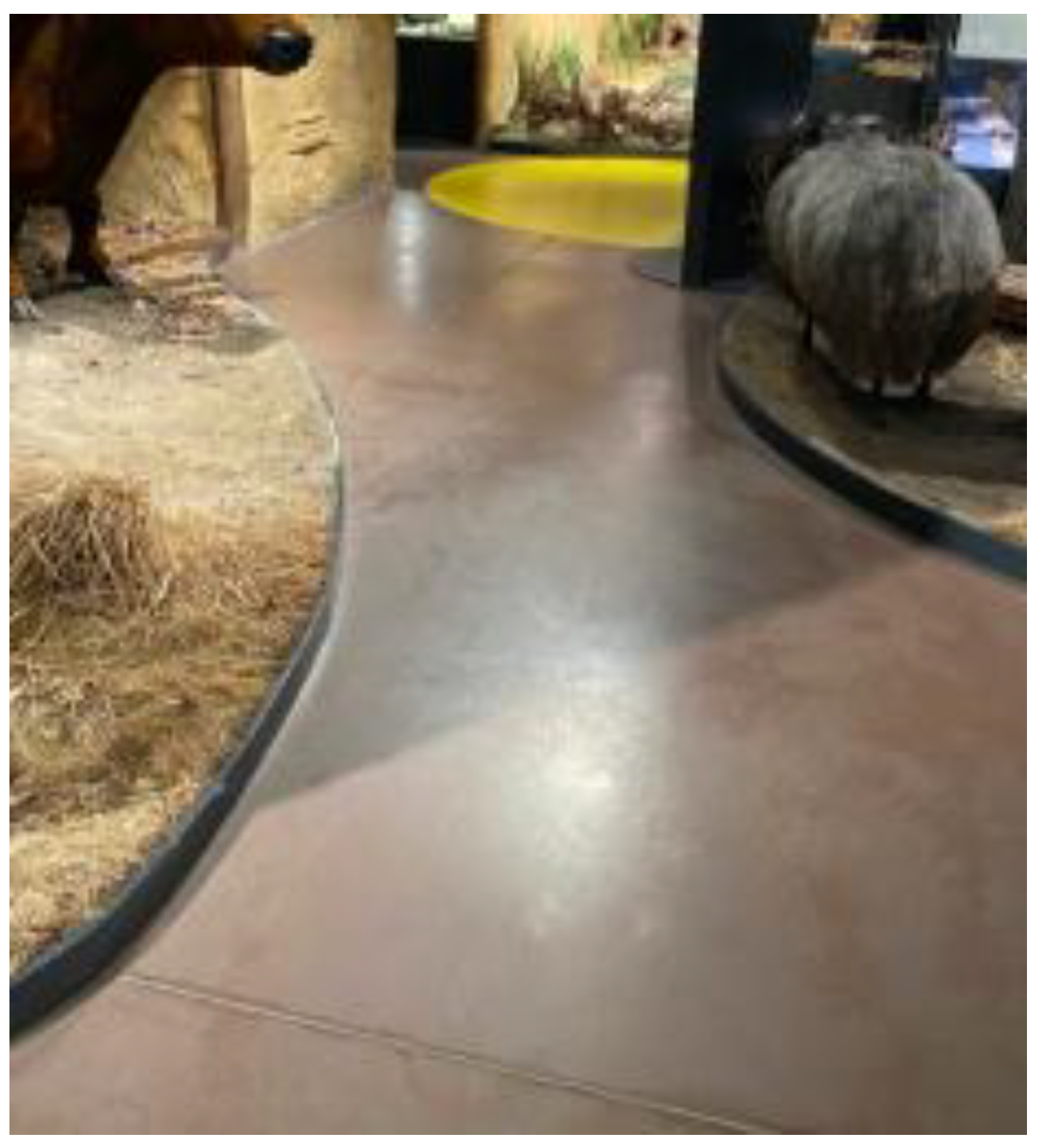

Photo 5.

Wide passageways between exhibits in the Opatów Krzemionki (photo K. Chwaja).

Photo 5.

Wide passageways between exhibits in the Opatów Krzemionki (photo K. Chwaja).

Photo 4.

Lift crane at Krzyżtopór Castle (photo B. Chwaja).

Photo 4.

Lift crane at Krzyżtopór Castle (photo B. Chwaja).

Photo 6.

The staircase platform at the National Museum in Kielce (photo. I. Marczak).

Photo 6.

The staircase platform at the National Museum in Kielce (photo. I. Marczak).

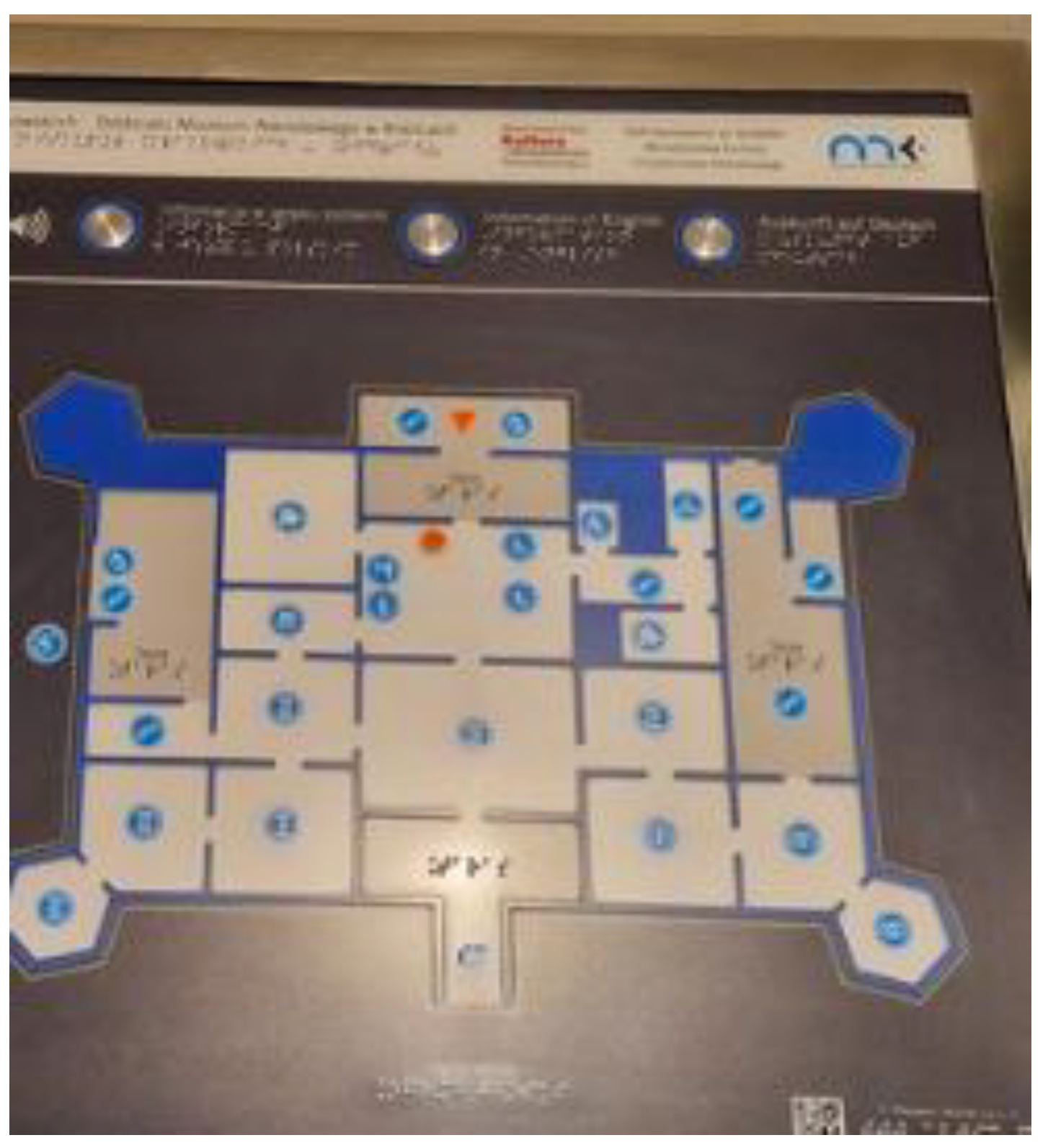

Photo 7.

Tiflographic plan in the National Museum in Kielce (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 7.

Tiflographic plan in the National Museum in Kielce (photo I. Marczak).

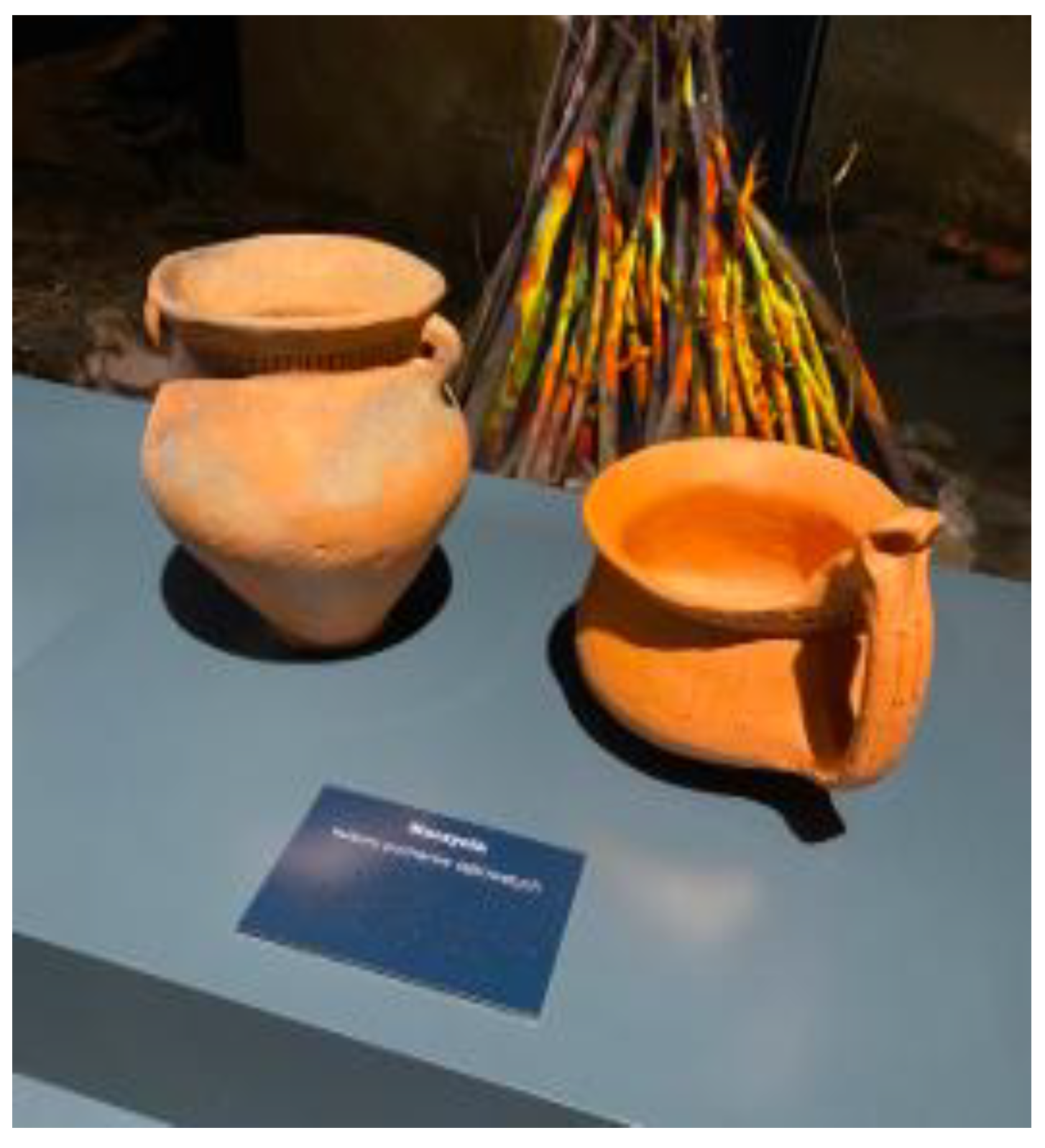

Photo 8.

Exhibits designed to be touched and labelled in Braille at Krzemionki Opatowskie (photo. K.Chwaja).

Photo 8.

Exhibits designed to be touched and labelled in Braille at Krzemionki Opatowskie (photo. K.Chwaja).

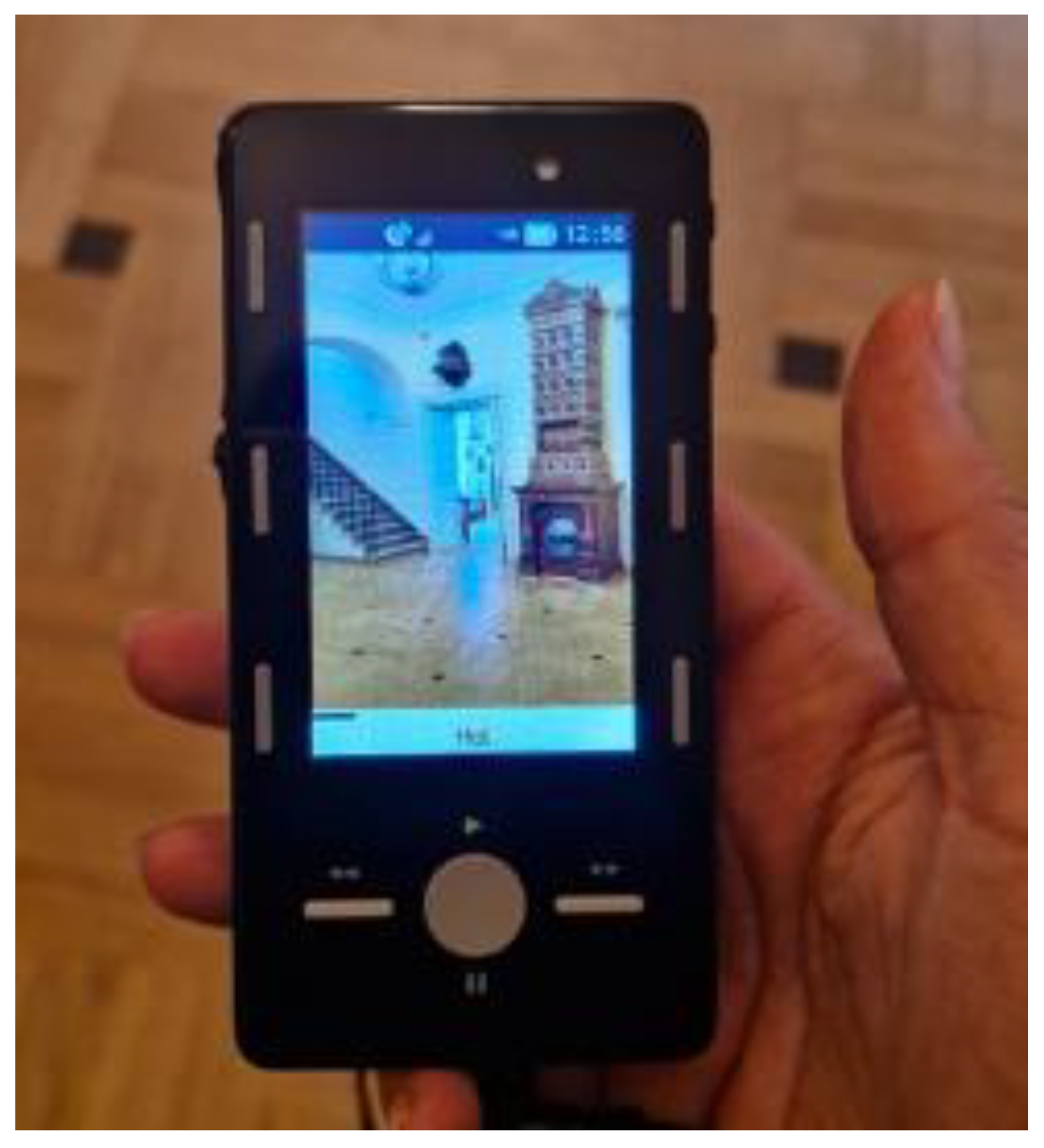

Photo 9.

The audiodescription programme at the Henryk Sienkiewicz Museum in Oblęgorek (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 9.

The audiodescription programme at the Henryk Sienkiewicz Museum in Oblęgorek (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 10.

Convex pictograms and Braille descriptions at the Kielce Village Museum (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 10.

Convex pictograms and Braille descriptions at the Kielce Village Museum (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 11.

Links with QR codes in Chęciny Castle (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 11.

Links with QR codes in Chęciny Castle (photo I. Marczak).

Photo 12.

Marking out the induction loop at the European Fairy Tale Centre in Pacanów (photo K. Chwaja).

Photo 12.

Marking out the induction loop at the European Fairy Tale Centre in Pacanów (photo K. Chwaja).

6. Actions for the Inclusion of the People with Disabilities in the Świętokrzyskie Region

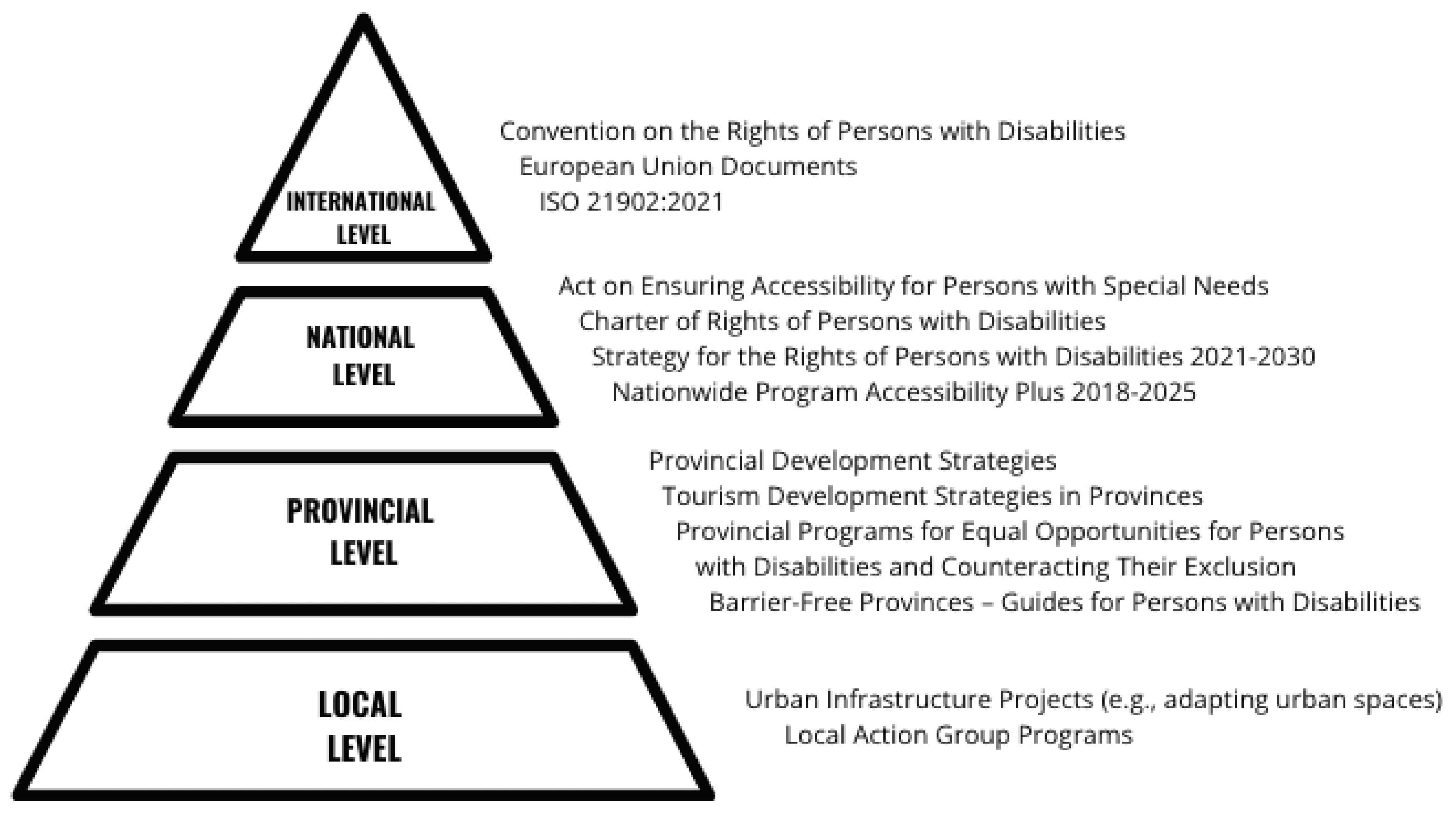

The problems of people with special needs are addressed at different levels of governance (

Figure 8). From the perspective of international law, one of the most important documents is the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2]. However, the way in which individual countries implement the recommendations contained at the highest levels is extremely important [28]. In Poland, Article 32 of the Constitution guarantees the right to equality, including the provision of equal opportunities and prohibition of discrimination, while according to Article 69, people with disabilities are to be provided with support from the state [29]. The topic of inclusion is addressed by the Act on Ensuring Accessibility for Persons with Special Needs [30] and the Charter of Rights of Persons with Disabilities [31].

A Strategy for Persons with Disabilities has been developed for the period 2021-2030, and a National Accessibility Plus Programme is in operation for the period 2018-2025. Documents at the provincial level include Provincial Development Strategies and also Tourism Development Strategies for their area. At the same time, provincial programmes for equalising opportunities for people with disabilities and counteracting their exclusion are being created, as well as dedicated guides.

Figure 10.

The place of accessible tourism at different levels of governance (own elaboration based on [28]).

Figure 10.

The place of accessible tourism at different levels of governance (own elaboration based on [28]).

Social inclusion is also a challenge for the tourism industry, for which services for seniors are indicated among the predicted trends, alongside luxury services, experience tourism and sustainable, environmentally and climate-friendly services [32]. It should be emphasised that the involvement of multiple stakeholder groups is needed to provide universal solutions. Actions at the local level are extremely important, as this is where the real effects of actions become most visible, e.g., one good example of a municipal infrastructure project adapted for people with disabilities is the ‘Barcelona Accesible’ project [33]. This project introduced a range of solutions such as the upgrade of architectural barrier-free spaces, a low-floor bus fleet and digital accessibility tools. As has been rightly pointed out, there is a wealth of publications on disability and accessibility of tourist attractions in various regions of Poland [8], but no comprehensive overview regarding the Świętokrzyskie Region [34].

In the Świętokrzyskie Region, under the Act on Ensuring Accessibility for Persons with Special Needs, there is a Social Council for Persons with Disabilities, which is primarily responsible for providing an opinion on draft resolutions and programmes adopted by the Voivodeship Council in terms of their impact on persons with disabilities [35]. Creating favourable conditions for people with disabilities has found a place in the Strategy for Tourism Development in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship 2014-2020 [36] and in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2030+ [37].

Table 3 presents selected objectives and activities that are related to the inclusion of people with disabilities in tourism in the study region.

In both Strategies for the Development of Tourism in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship for 2014-2020, priority directions of actions are addressed to people with disabilities, such as, among others, improving communication accessibility, eliminating architectural barriers and ensuring digital and information accessibility. In terms of social policy, the programme for equalisation of opportunities for persons with disabilities and counteracting their social exclusion, as well as assistance in the implementation of tasks for the employment of people with disabilities for 2021-2026 [37] has been written down. Funding is also provided for projects that improve accessibility for people with disabilities. These investments include upgrading public infrastructure, adapting public buildings and developing accessible transport services and public spaces. Funds are earmarked for eliminating architectural barriers, introducing facilities for people with reduced mobility and improving digital accessibility [39]. As part of the project ‘Improving the accessibility of tourist information about the Świętokrzyskie region for people with disabilities’, the Świętokrzyska Regional Tourist Organisation carried out training dedicated to the staff of Tourist Information Centres and Points on serving tourists with disabilities, adapting websites including

www.swietokrzyskie.travel for the needs of people with disabilities, in accordance with the WCAG 2.0 standard at AA level. As part of this project, an audioguide was created, mainly aimed at blind people, which presents the biggest attractions of the voivodeship [39]. As early as 2009, a guide for the disabled, ‘Świętokrzyskie without barriers’ [40], was developed, which included suggested routes intended mainly for people with impaired mobility, but unfortunately due to a number of changes including new admission prices and renovations of sites, such as the rebuilding of Krzemionki Opatowskie. This guide differs in content from those for other regions in Poland, such as Krakow [41] and the Silesia region [42].

Physical and mental fitness is an important part of human well-being, therefore preventing disability and social exclusion should be in everyone’s interest. With increasing computerisation, there is an opportunity to design new technological solutions aimed at people with disabilities, such as beacons. It is a technology that promotes equal opportunities and helps, among other things, to collect and transmit information, which use translates into communication and navigation, including in tourism [13].

Actions to increase the level of participation of people with disabilities in tourism and recreation have a positive impact on both the physical and psychological spheres of people with disabilities [43].

7. Discussion

Confronting the results obtained with other research on Krakow’s flagship attractions, it appears that museums are by far the group of attractions best adapted to accommodate tourists with disabilities [8]. Comparing the two surveys, in both the Lesser Poland and Świętokrzyskie regions, we find that the facilities in the attractions are mainly geared towards people with mobility impairments, and much less so towards the needs of people with sight and hearing impairments. In a 2010 comparison of tourist facilities adapted to the needs of people with disabilities, the Świętokrzyskie region reached a distant place (only 3% of facilities have such adaptations) [44]. It was also found to have the lowest density of adapted tourist routes for people with disabilities compared to other regions [45]. Our study shows a significant improvement in this respect, having made significant changes to the accessibility of tourist facilities in recent years. The renovation of the Krzemionki Opatowskie Underground Route, the opening of modern museums such as the Museum of Ancient Metallurgy in Nowa Słupia or the Legends Park, the renovation and upgrading of the route around the Kadzielnia Nature Reserve are just a few of the many tourism development measures for the region in 2019-2024. Consequently, the tourist accessibility of the region for people with disabilities has increased significantly.

Measures for social inclusion are confirmed by a decrease in unemployment among people with disabilities, and an increase in economic activity in this group of people [46] and the employment rate. This indicates an increasing need for self-realisation and independence among people with disabilities, which may manifest itself in a desire to meet needs in other areas as well. Tourism has a positive impact on maintaining activity, improving cognitive function, fulfilling the need to explore and generally improving wellbeing in older people [47]. Among them, people with disabilities are a large group, so adapting tourist attractions to their requirements will undoubtedly enable them to realise their need to explore the world without fear for their own safety and health [48].

There is a need to assess the adaptation of facilities to meet the needs of people with intellectual disabilities and those with special needs related to neurological developmental disorders such as autism. These groups also represent a significant proportion of society and continue to experience social exclusion [49]. Disability should not define a person, as the medical approach does, as a passive recipient of support, but should be an equal member of society [48]. Therefore, barriers need to be removed by introducing practices aimed at including these groups and counteracting their isolation from society [50]. One such practice will be to enable this group to enjoy the benefits of tourism, by adapting tourist attractions to their special needs. Tourism for the intellectually disabled is an important therapeutic element, allows the development of interpersonal contacts, and allows for more complete social integration [51]. Therefore, there is a need to continue research with other groups of people with disabilities

Creating accessibility to tourist attractions is one way to increase the attractiveness or competitiveness of a tourist destination [52,53]. Such an opportunity for the Świętokrzyskie Region is unanimously perceived by all local stakeholders, i.e., local authorities, the tourism industry (managers of attractions, accommodation and catering facilities, tourism organizers) and, above all, people with disabilities.

Indeed, the development of inclusive tourism aims not only to expand access to consumption, production and benefit sharing in existing tourism destinations, but also to redraw the tourism map to create new places of experience and interaction [54]. Inclusive tourism encompasses a wide range of actors in a variety of settings seeking to expand the circle of people involved in tourism creation, tourism consumption and tourism benefit sharing. In many cases, these initiatives involve new geographic areas of tourism[55,56].

8. Responses to Research Questions

Q1 - Are the main attractions of the Świętokrzyskie region accessible to people with disabilities and for which types of disabilities facilities have been created

The research conducted indicates that the level of adaptation of selected tourist attractions to the needs of different groups with disabilities varies. None of the surveyed facilities is fully ready to accommodate people with disabilities with mobility, vision and hearing impairments. Recreation and entertainment attractions with the highest attendance are the best adapted for the mobility impaired, but lack facilities for the visually and hearing impaired. Museums and open-air museums are by far the best adapted for people with visual and hearing impairments. In other facilities, fewer facilities are dedicated to these people, indicating the need to increase efforts for their inclusion. In the case of people with visual impairments, it is worthwhile to introduce guides who provide assistance and support, providing verbal descriptions of exhibits and the ability to touch some objects, enabling a more complete historical experience. Guides should be prepared to work with the hearing impaired, providing sign language interpretation or providing detailed visual and textual explanations, among other things.

Q2 - What is the degree of accessibility of attractions for people with disabilities

The degree of accessibility of tourist attractions in the Świętokrzyskie region for people with disabilities varies and depends on the type of limitations that visitors face. However, none of the surveyed facilities are fully adapted for any of the analyzed groups. The surveyed attractions are best prepared for people who have mobility problems, to a lesser extent for the blind and visually impaired, and to the least extent for the hearing and deaf. The main barriers to adapting the facilities are due to financial constraints and the need to preserve the historic character of the buildings, which often requires the approval of a preservationist. Despite these difficulties, many attraction managers say they are willing to further improve accessibility, which can contribute to the inclusiveness of tourism in the Region.

Q3 - What measures are being taken to improve the accessibility of tourist facilities for people with disabilities

The problems of people with special needs are included in the development strategies of the Świętokrzyskie Region. Priority courses of action relate to improving communication accessibility, eliminating architectural barriers and ensuring digital and information accessibility. In terms of social policy, a program to equalize opportunities for people with disabilities and prevent their social exclusion is being implemented. Funding is also provided for projects that improve accessibility for people with disabilities.

9. Conclusions

In recent years, the number of people with disabilities in the world and in Poland has been steadily increasing, and changing attitudes toward this group of people and growing awareness of the barriers they face have made accessibility to various spheres of life, including tourism, an increasingly important issue. This is evident in the policies pursued at various levels, where attention is paid to measures to create accessibility of infrastructure and services for all citizens.

Research on the accessibility of tourist attractions for people with disabilities people enriches the multidimensional picture of the issue of inclusion in tourism. Tourism plays an important role not only as a form of physical activity, but also as a tool for social integration and rehabilitation. In the context of the Świętokrzyskie Region, which has significant tourism potential, the issue of adapting the main tourist spots to the needs of people with disabilities takes on particular importance. Many custodians pointed to financial barriers and limitations due to the historic nature of the sites as major obstacles to fully adapting the attractions. These constraints are particularly difficult to overcome in the case of historic sites, where the need to preserve the authenticity of historic buildings often interferes with the introduction of modern amenities.It is encouraging that creating accessible space is now standard at the planning stage of new facilities. It is encouraging that nowadays the creation of accessible space is standard at the planning stage of new facilities.

Another of the significant problems revealed in the survey is the inadequate training of staff in handling people with disabilities. The surveyed facilities found a low percentage of staff with adequate competence in this area. In a small number of cases, staff were adequately prepared, which underscores that the implementation of comprehensive training programs to better serve and ensure the comfort of all visitors is a must. In places where modern technologies such as audiodescription, induction loops and beacons have been used, clear benefits for people with disabilities have been noted. These technological innovations have significantly improved the quality of tours, indicating the potential for further implementation as an effective tool in improving the accessibility of tourist attractions. A growing awareness of the need to improve accessibility and a willingness to make changes was also noted at many sites. The custodians’ declarations regarding future plans indicate a positive attitude toward the integration of people with disabilities, which is a promising sign for the future development of tourism in the region.

In conclusion, the results of the survey indicate an urgent need to continue efforts to improve the accessibility of tourist attractions in the Świętokrzyskie Region. Improving accessibility will not only affect the quality of life of people with disabilities, but will also contribute to the attractiveness of the region, which may have long-term economic and social benefits. Increasing the number of tourists from this group will not only bring economic benefits, but will also improve the perception of the region as a modern and inclusive place, ready to welcome all visitors, regardless of their disabilities. In order to achieve these goals, it will be necessary to further engage local authorities and tourism facility managers in implementing strategies for the inclusion of people with disabilities.

10. Theoretical and Practical Significance of the Research

The assessment of the accessibility of attractions for people with disabilities presented in this article contributes to the identification of problems related to access to heritage for people with special needs. The results of the study are therefore part of the phenomenon of social inclusion and inclusive tourism. The activities described above, which aim to make attractions accessible to different groups of people with disabilities, and the implementation of technical, organizational and informational facilities, provide a case study of good practices for attraction managers. The results of our research indicate the need for further analysis to identify barriers to the development of accessibility in tourist attractions and to seek solutions for learning and dissemination of good practices.

11. Limitations

This research was limited to selected tourist attractions and to three types of disabilities, i.e., mobility dysfunctions, the visually impaired and blind, and the hearing impaired and deaf. To get a more complete picture of the accessibility of attractions, these studies should be continued for other types of disabilities, such as those with mental disabilities. The research focused on only 20 attractions in one region of Poland, and similar research should be considered in other regions to both compare accessibility and promote good practices.

Author Contributions

This article is a joint work of the four authors. Conceptualization KCh, ZK and IM; literature review, KCh, ZK and IM, writing—original draft preparation KCh, BCh and writing—review and editing, IM visualization, KCH, IM, BCh supervision, ZK and KCh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ disability-and-health (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA. 2006.

- Konarska J. Niepełnosprawność w ujęciu interdyscyplinarnym [Disability from an interdisciplinary perspective]. 2019, Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, Kraków.

- Kaganek K. Wybrane uwarunkowania i funkcje turystyki jako determinanty uprawiania turystyki aktywnej przez osoby niepełnosprawne ruchowo, wzrokowo i słuchowo [Selected conditions and functions of tourism as determinants of active tourism by people with motor, visual and hearing disabilities]. Folia Turistica, 2017, 43.

- Preisler M. Turystyka osób niepełnosprawnych [Tourism for people with disabilities]. Studia Periegetica. 2011, 6.

- Kasperczyk T., Walaszek R., Ostrowski A. Turystyka, rekreacja i sport osób niepełnosprawnych–teoria a rzeczywistość [Tourism, recreation and sports for people with disabilities – theory and reality]. Folia Turistica, 2013, 29.

- Kruczek, Z.; Gmyrek, K.; Żizka, D.; Korbiel, K.; Nowak, K. Accessibility of Cultural Heritage Sites for People with Disabilities: A Case Study on Krakow Museums. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 318. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su16010318.

- Kruczek, Z., Gmyrek, K., Chwaja, K., Camona, K. Działania na rzecz dostępności atrakcji turystycznych w Krakowie dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami jako element zrównoważonej polityki turystycznej miasta [Actions for the accessibility of tourist attractions in Krakow for people with disabilities as an element of the city’s sustainable tourism policy]. Turystyka. Zarządzanie, Administracja, Prawo. 2024, 2.

- Kruczek, Z. Polska. Geografia atrakcji turystycznych [Poland. Geography of tourist attractions]. 2011. Proksenia, Kraków.

- Galewska A. Ocena wdrożenia standardów turystyki zrównoważonej w województwie świętokrzyskim [Assessment of the implementation of sustainable tourism standards in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship]. 2023. Polska Organizacja Turystyczna.

- Dudzińska, A. Niepełnosprawność jako obszar interwencji publicznej [Disability as an area of public intervention]. 2021, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

- Berger, P.L., Luckmann, T. Społeczne tworzenie rzeczywistości [Social creation of reality]. 2010. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

- Bajak M. Equal opportunities for people with disabilities in public institutions through beacons. [in:] Oxford Conference Series. 2019, p. 55-71.

- UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2012). https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd (accessed on 8 Feb. 2025).

- Darcy, S., Ambrose, I., Schweinsberg, S., Buhalis, D. Universal Approaches to Accessible Tourism. In: D. Buhalis, S. Darcy (eds.). Accessible Tourism. Concepts and Issues. Bristol: Channel View Publications. 2011, 300–316.

- Zajadacz A. Evolution of models of disability as a basis for further policy changes in accessible tourism. J. Tour. Futures. 2015, 1, 189–202.

- Park, J.; Chowdlhury, S. Investigating the barriers in a typical journey by public transport users with disabilities. J. Transp. Health. 2018, 10, 361–368.

- Załuska, U., Kwiatkowska-Ciotucha, D., Grześkowiak, A. Travelling from Perspective of Persons with Disability: Results of an International Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 19(17). [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S. Inherent complexity: Disability, accessible tourism and accommodation information preferences. 2010, Tour. Manag. 31, 816–826.

- Popovic, D., Slivar, I. Gonan Božac M. Accessible Tourism and Formal Planning: Current State of Istria County in Croatia. 2022, Administrative Sciences, 12: 181. [CrossRef]

- Gaweł Ł. Museums without visitors? Crisis and revival - managing the “digital world” in Polish museums in times of pandemic. Sustainability. 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek Z., Frekwencja w atrakcjach turystycznych w roku 2023 [Attendance at Tourist Attractions in 2023]. Polska Organizacja Turystyczna, Warszawa 2025, Available online, accessed on 28 February 2025.

-

Standardy dostępności budynków dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami, Poradnik [Standards of accessibility of buildings for people with disabilities, Guide]. Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju. 2017, Warszawa.

- Espinosa, R., A., Bonmatí Lledó C. (eds.). Manual de accesibilidad e inclusión en museos y lugares del patrimonio cultural y natural. 2013, Gijón.

- Skalska, T. Identifying quality gaps in tourism for people with disabilities: Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA). Tourism. 2023, 33(1), 41–48. [CrossRef]

- https://www.kielce.eu/pl/aktualnosci/na-kadzielni-powstal-tor-do-nauki-jazdy-na-wozku-inwalidzkim.html (accessed on February 28 2025).

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1599, (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Jankowska, Maria. Prawa osób niepełnosprawnych w międzynarodowych aktach prawnych. Niepełnosprawność–zagadnienia, problemy, rozwiązania [Rights of people with disabilities in international legal acts. Disability – issues, problems, solutions]. 2011, p. 24-45.

- Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [Constitution of the Republic of Poland] 1997. https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/polski/kon1.htm, accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Ustawa o zapewnianiu dostępności osobom ze szczególnymi potrzebami [Act on ensuring accessibility for people with special needs]. 2019. https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190001696 accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Karta Praw Osób Niepełnosprawnych [Disability Rights Bill]. 1997. https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/mp-monitor-polski/karta-praw-osob-niepelnosprawnych-16826971, accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Kociszewski, P. Kształtowanie oferty na rynku turystyki kulturowej przez organizatorów turystyki (na przykładzie turystów seniorów) [Shaping the offer on the cultural tourism market by tourism organizers (on the example of senior tourists)]. Turystyka Kulturowa, 2017, 1.

- Mestres Petit, A., Morera, S., Trujjillo Parra, L. Valladares, M. The Accessibility Chain: a Challenge and an Opportunity for Cities and People with Disabilities. The Journal of Public Space. 2022, 7(2), s. 205–222.

- https://www.swietokrzyskie.pro/informacje-ogolne-podstawa-prawna/, accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Majewska, I., Wilczyński, B., Wilczyński, Ł. Strategia rozwoju turystyki w województwie świętokrzyskim na lata 2015–2020 [Tourism development strategy in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship for the years 2015–202]. 2014, Kielce.

- Majewska, I. i in. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Świętokrzyskiego 2030+ [Development Strategy of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship 2030+]. 2021, Kielce.

-

Wojewódzki program wyrównywania szans osób niepełnosprawnych i przeciwdziałania ich wykluczeniu społecznemu oraz pomocy w realizacji zadań na rzecz zatrudniania osób niepełnosprawnych na lata 2021-2026 [Provincial program for equalizing opportunities for people with disabilities and counteracting their social exclusion and assistance in implementing tasks for the employment of people with disabilities for 2021-2026]. 2021. Kielce. https://www.swietokrzyskie.pro/wojewodzki-program-wyrownywania-szans-osob-niepelnosprawnych-i-przeciwdzialania-ich-wykluczeniu-spolecznemu-oraz-pomocy-w-realizacji-zadan-na-rzecz-zatrudniania-osob-niepelnosprawnych-na-lata-2021/ accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Program Regionalny Fundusze Europejskie dla Świętokrzyskiego 2021-2027 [Regional Programme European Funds for Świętokrzyskie 2021-2027] https://funduszeueswietokrzyskie.pl/poradniki/fundusze-europejskie-dla-swietokrzyskiego-2021-2027/o-programie accessed on 28 February 2025.

- https://swietokrzyskie.travel/aktualnosci/swietokrzyska_informacja_turystyczna_dla_niepelnosprawnych accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Sardey, Y., Ramiączek, D., Fornalczyk, M., Skuta, S. Świętokrzyskie bez barier. Przewodnik dla niepełnosprawnych [Świętokrzyskie without barriers. A guide for the disabled.]. 2009, Media Consulting Agency, Wrocław.

- Kapusta, P. Przewodnik po Krakowie dla turysty z niepełnosprawnościami. [A guide to Krakow for tourists with disabilities]. 2018. Urząd Miasta Krakowa, Biuro ds. Osób Niepełnosprawnych.

-

Śląskie bez barier [Silesia without barriers]. 2022. Śląska Organizacja Turystyczna https://www.slaskie.travel/article/1020295 accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Śledzińska, J. Turystyka osób niepełnosprawnych w Polskim Towarzystwie Turystyczno-Krajoznawczym [Tourism for disabled people in the Polish Tourist and Sightseeing Society], In: Niepełnosprawność–zagadnienia, problemy, rozwiązania, [Disability – issues, problems, solutions]. 2012. PTTK, Warszawa, 2, s. 82.

- Bogucka, A. Przystosowanie bazy turystycznej na potrzeby osób niepełnosprawnych [Adapting the Tourist Base to the Needs of the Disabled]. Ekonomia i Zarządzanie. 2010, 2(3).

- Francuz, S., Calińska-Rogala, D. Ocena przystosowania atrakcji turystycznych dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami w Polsce [Assessment of the Adaptation of Tourist Attractions for the Disabled in Poland]. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie. 2019, 20(2).

- Stolarczyk, P. Osoby niepełnosprawne na rynku pracy w województwie mazowieckim [People with disabilities on the labor market in the Masovian Voivodeship] In; Niepełnosprawność – zagadnienia, problemy, rozwiązania [Disability – Issues, Problems, Solutions]. 2021, Nr III-IV(40-41), PFRON, Warszawa.

- Wiza, A. Aktywność turystyczna osób starszych w kontekście jakości życia [Tourist Activity of the Elderly in the Context of Quality of Life]. Turystyka Kulturowa. 2016, nr 6.

- Woźniak, A. Edukacja dostępna dla wszystkich. Razem zmieniamy śląskie. Biuletyn informacyjny regionalnego programu operacyjnego województwa śląskiego [Education accessible to all. Together we change Silesia. Information bulletin of the regional operational program of the Silesian province]. E-publikacja 2017. https://rpo.slaskie.pl/media/addons/ebiuletyn/?W_numerze___Ekspert_podpowiada___Edukacja_dost%C4%99pna_dla_wszystkich accessed on 28 February 2025.

- Mozdyniewicz, M. Wykluczenie społeczne osób z autyzmem i ich rodzin. [Social exclusion of people with autism and their families], Uniwersytet Jagielloński. 2020, Kraków.

- Chojnacki, K. Turystyka osób niepełnosprawnych intelektualnie jako forma rehabilitacji fizycznej, psychicznej i społecznej [Tourism for people with intellectual disabilities as a form of physical, mental and social rehabilitation]. Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego im. Bronisława Czecha, 2007, Kraków.

- Zajadacz, A. Evolution of models of disability as a basis for further policy changes in accessible tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures. 2015, 1, 189–202. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, M.E., Criado-García, F., Camúñez-Ruíz, J.A., Casado-Pérez, M.,. Accessibility to Cultural Tourism: The Case of the Major Museums in the City of Seville. Sustainability. 2021,13. [CrossRef]

- Lubarska, A. Ocena dostępności przestrzeni turystycznej dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami [Assessment of the accessibility of tourist space for people with disabilities]. PhD thesis. 2022. Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza, Poznań.

- Scheyvens, R., Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development, Tourism Geographies. 2018, 20:4, 589-609. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M., van der Duim, R., Peters, K., Klomp, J. Tourism and Inclusive Growth: Evaluating a Diagnostic Framework. Tourism Planning and Development. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, Z., Gmyrek, K., Ziżka, D., Korbiel, K. Inclusive tourism - an attempt at providing a definition and comparison with other concepts. Literature review [In]: Application of the principles of inclusion in tourism in V4 countries – theoretical definition, research, analysis, recommendations. Eds. I. Hamarneh, R. Marcekova, Z. Kruczek, International Visegrad Fund, and the Pan-European University, 2024, Prague.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).