Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population and Sampling

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

- Z is the Z-score for a 95% confidence level (1.96)

- p is the response proportion (0.5)

- q=1−p=0.5

- E is the margin of error (0.05)

2.3. Pilot Study

2.4. Survey Questionnaire Tool, Locations and Delivery

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Knowledge About Influenza Infection and Prevention Measures

3.2. Knowledge About MIV Uptake During Pregnancy

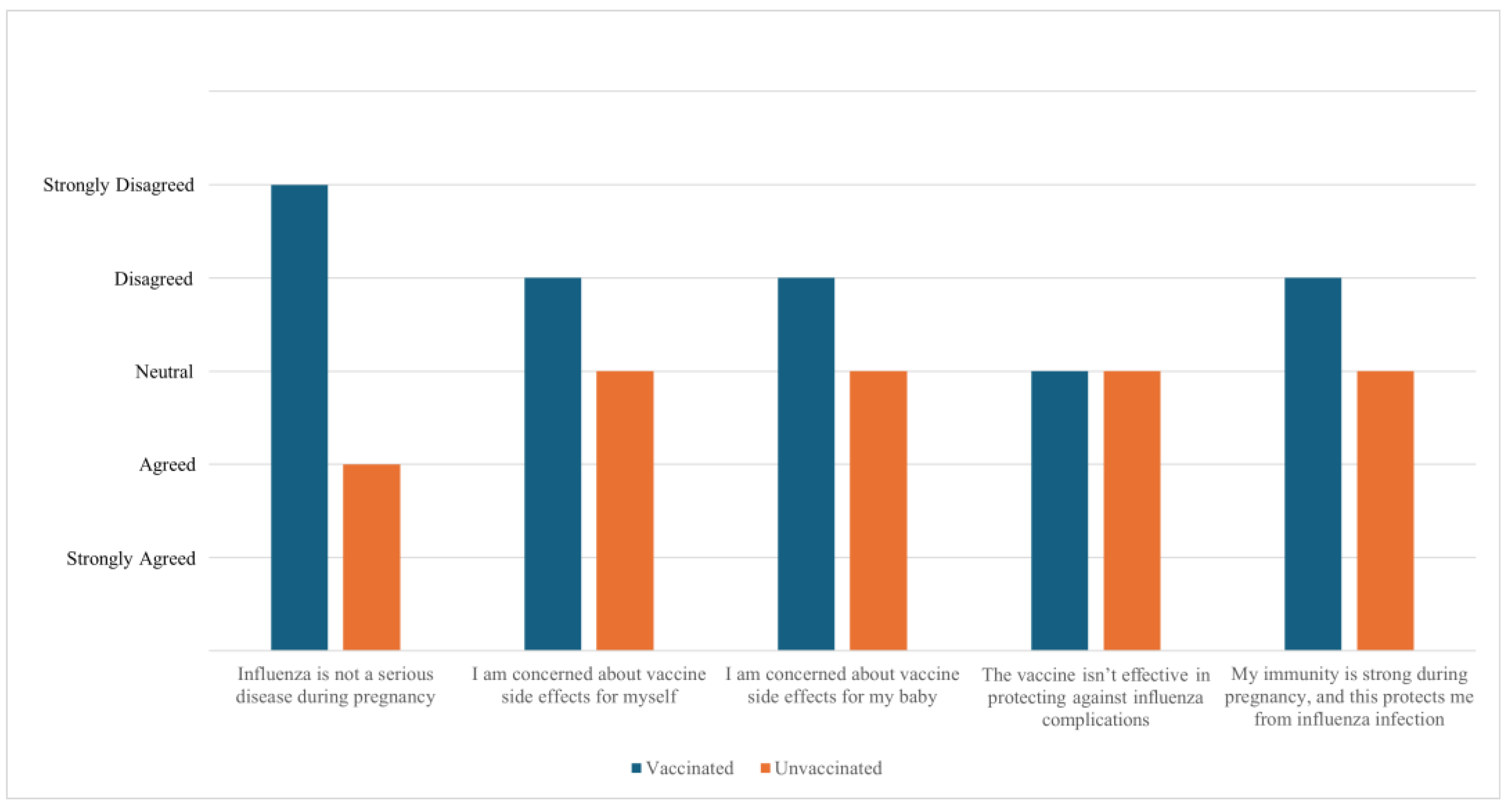

3.2. Perceptions and Attitudes of Vaccinated Participants Toward MIV Uptake

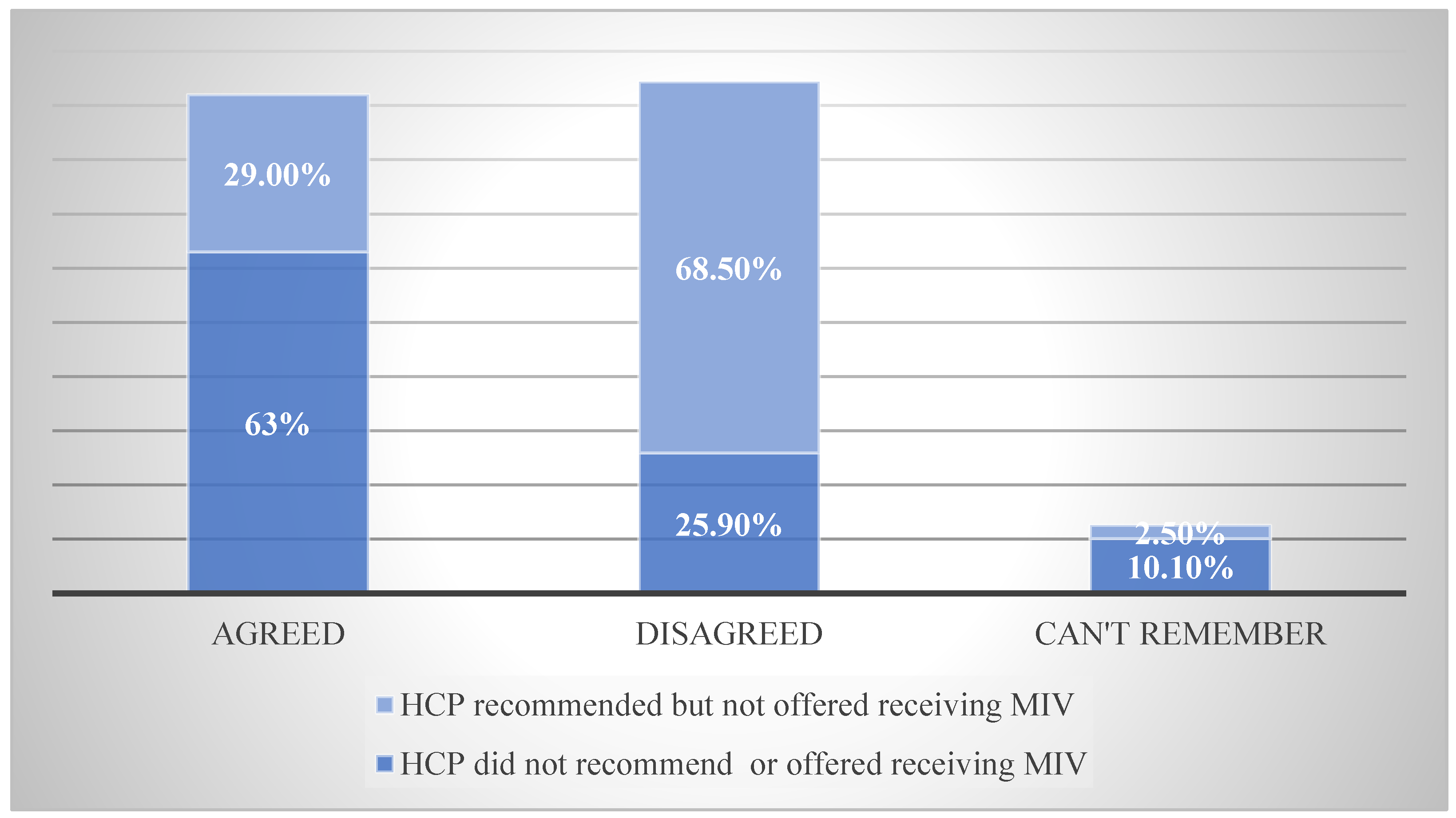

3.2. HCPs Recommendations and Provision of MIV

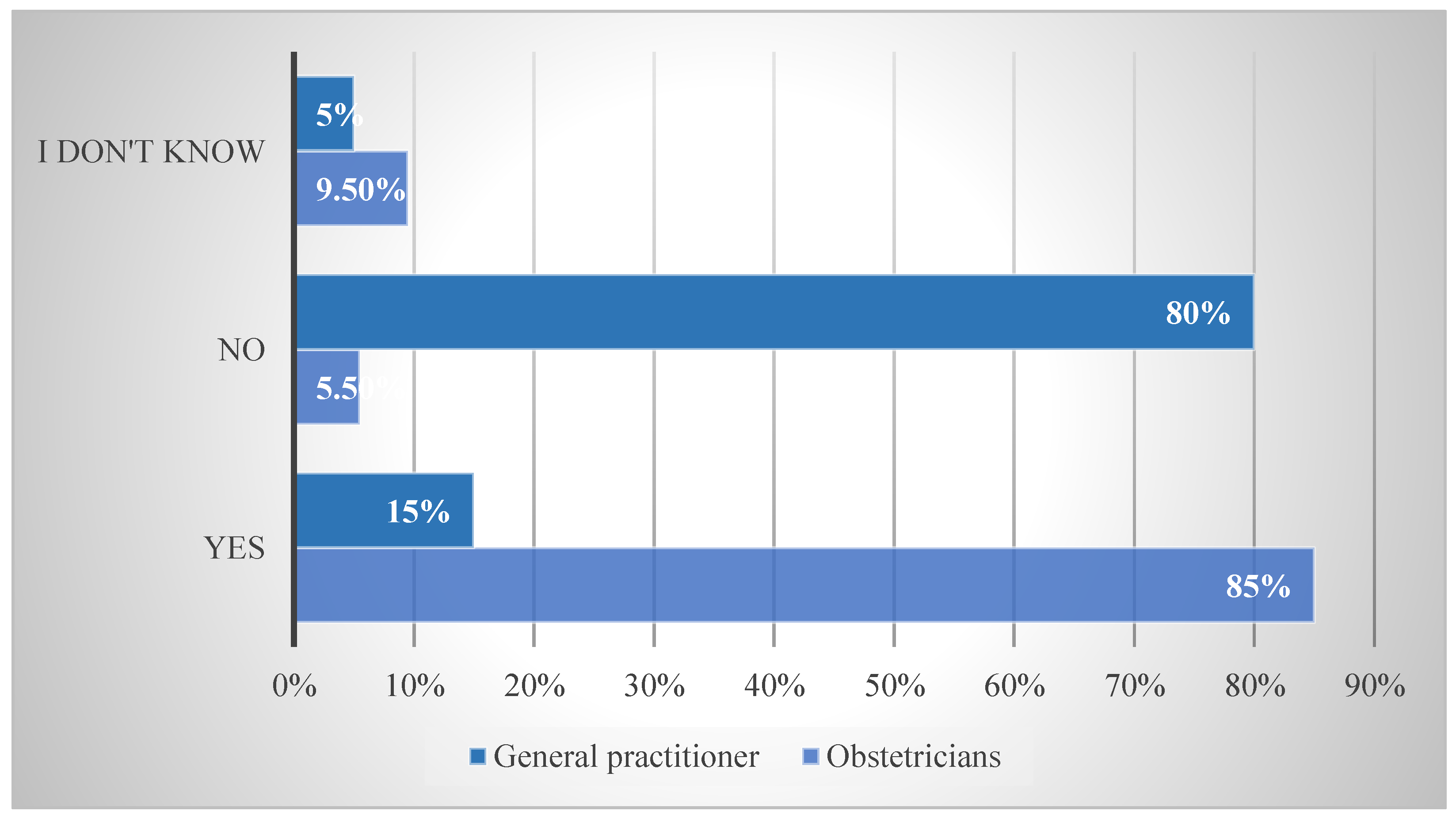

3.2. Influence of Different HCPs Toward MIV

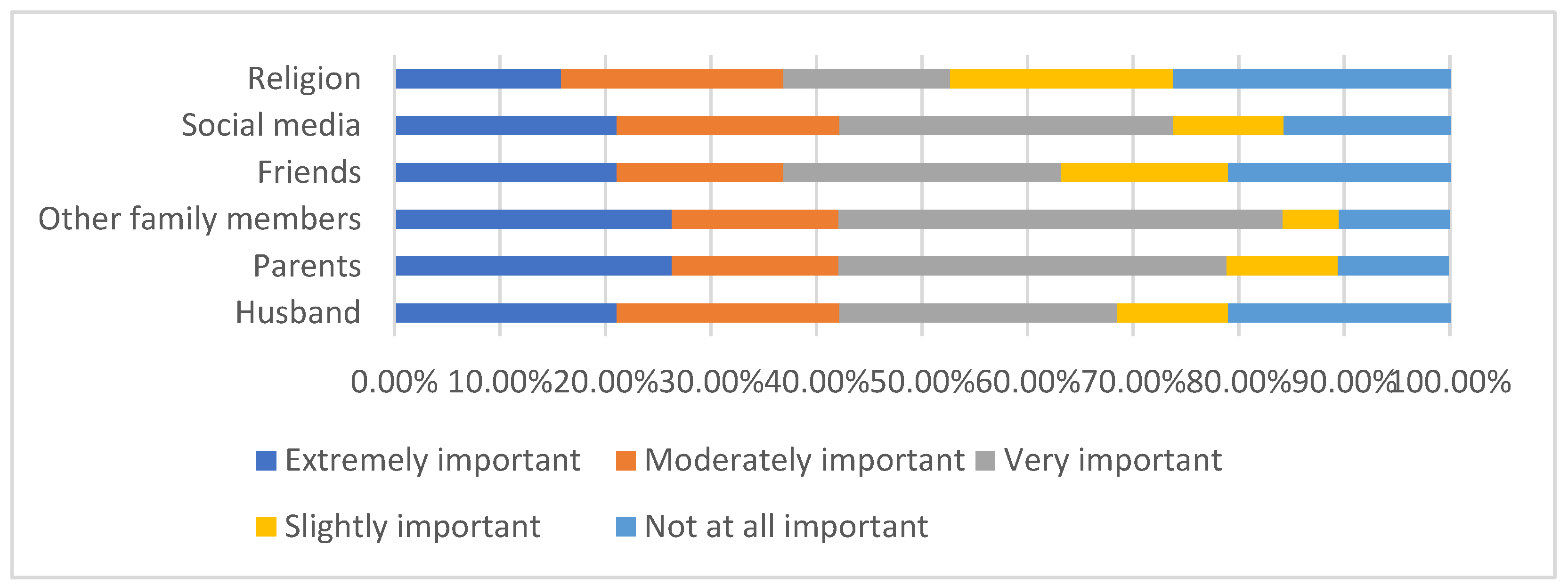

3.2. Importance of Different Influences on Pregnant Women’s Perceptions Toward MIV Uptake

3.2. Recommendations to Enhance the Uptake of MIV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

|

Group |

Sub-group | responses |

|---|---|---|

| Demography | Nine questions. | Choose one answer |

| Questions about influenza and influenza prevention during pregnancy | Influenza infection’s preventive measures. | Yes No I do not know |

| Knowledge of MIV provision in Kuwait. | Agree Disagree I do not now |

|

| In the third to sixth questions, about the timing and form in which knowledge about MIV was delivered. | Choose one answer. | |

| Questions about influenza vaccination during pregnancy | Questions about vaccination history, including MIV and COVID-19 vaccines. | Yes No I cannot remember |

| The rule of the different specialists of HCPs in MIV recommendations. | Participants can select all answers that apply (can be more than one). | |

| Vaccinated participants were asked thirteen questions about their perception of MIV. | Likert Scale of five responses for the importance. | |

| Seventeen questions to be answered by non-vaccinated participants about their perception of MIV. | Likert scale of five responses for the agreement with a statement. |

|

| Six questions about how the perception of non-vaccinated participants could be changed for future acceptance of MIV uptake. Vaccinated and non-vaccinated participants answered this category. | Likert scale of six responses for importance, participants can choose a “Not applicable” answer. |

Appendix A.2

| Influenza Statement | Median | Q1-Q3 | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza is not a serious disease during pregnancy | 4.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| I am concerned about vaccine side effects for myself | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| I am concerned about vaccine side effects for my baby | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| The vaccine isn’t effective in protecting against influenza | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| My immunity is strong during pregnancy, and this protects me from influenza. | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

Appendix A.3

| Influenza Statement | Median | Q1-Q3 | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza is not a serious disease during pregnancy | 5.0 | 4.0-5.0 | 1.0 |

| I am concerned about vaccine side effects for myself | 4.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| I am concerned about vaccine side effects for my baby | 4.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| The vaccine isn’t effective in protecting against influenza | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

| My immunity is strong during pregnancy, and this protects me from influenza. | 4.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 1.0 |

Appendix A.4

| HCP’ recommendations | Median | Q1-Q3 | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is important to get a recommendation from my family physician about MIV | 4.0 | 1.75-5.0 | 3.0 |

| It is important to get a recommendation from my obstetrician about MIV | 5.0 | 3.75-5.0 | 1.0 |

Appendix A.5

| Social Relations’ Influence | Median | Q1-Q3 | IQR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husband | 3.0 | 2.0-4.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Parents | 3.0 | 2.0-4.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Other family members (mother-in-law, sisters, etc.) | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Friends | 3.0 | 3.0-4.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Social media | 3.0 | 2.0-4.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Religion | 3.0 | 2.0-4.0 | 1.0 | |||

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding flu viruses [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; 2019 [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/index.htm.

- Somerville L, Basile K, Dwyer D, Kok J. The impact of influenza virus infection in pregnancy. Future Microbiol. 2018; 13:263–74. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- World Health Organization. Maternal health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_3.

- United Nations. SDG media zone – the importance of vaccines [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/?p=86081.

- Gautret P, Bauge M, Simon F, Benkouiten S, Parola P, Brouqui P. Pneumococcal vaccination and Hajj. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(10): e730.

- Feldman C, Abdulkarim E, Alattar F, Al Lawati F, Al Khatib H, Al Maslamani M, et al. Pneumococcal disease in the Arabian Gulf: recognizing the challenge and moving toward a solution. J Infect Public Health. 2013; 6:401–9. [CrossRef]

- AlEnizi A, AlSaeid K, Alawadhi A, Hasan E, Husain E, AlFadhli A, et al. Kuwait recommendations on vaccine use in people with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Int J Rheumatol. 2018; 2018:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Mayet A, Al-Shaikh G, Al-Mandeel H, Alsaleh N, Hamad A. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers associated with the uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(1):76–82. [CrossRef]

- Barry M, Aljammaz K, Alrashed A. Knowledge, attitude, and barriers influencing seasonal influenza vaccination uptake. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2020; 2020:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Otieno N, Nyawanda B, Otiato F, Adero M, Wairimu W, Atito R, et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza and influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Kenya. Vaccine. 2020;38(43):6832–8. [CrossRef]

- Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, Wichmann O. Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine. 2014;32(33):4131–9. [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi A, Mereckiene J, Fitzgerald M, Cotter S. Determinants of influenza and pertussis vaccine uptake in pregnant women in Ireland: A cross-sectional survey in 2017/18 influenza season. Vaccine. 2019;37(43):6390–6.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Tailoring immunization programmes for seasonal influenza (TIP FLU) - a guide for increasing pregnant women’s uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination (2017) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2021 May 17]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/publications/2017/tailoring-immunization-programmes-for-seasonal-influenza-tip-flu-a-guide-for-increasing-pregnant-womens-uptake-of-seasonal-influenza-vaccination-2017.

- Adeyanju GC, Engel E, Koch L, et al. Determinants of influenza vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Med Res. 2021; 26:116. [CrossRef]

- Yuen C, Dodgson J, Tarrant M. Perceptions of Hong Kong Chinese women toward influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Vaccine. 2016;34(1):33–40. [CrossRef]

- Okoli GN, Reddy VK, Al-Yousif Y, Neilson CJ, Mahmud SM, Abou-Setta AM. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(6):997–1009.

- Ahluwalia IB, Jamieson DJ, Rasmussen SA, D’Angelo D, Goodman D, Kim H. Correlates of seasonal influenza vaccine coverage among pregnant women in Georgia and Rhode Island. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:949–55. [CrossRef]

- Payandeh Sh, Nabavi N, Movahedinia S, Poudineh V, Afzoon S, Malakoti N. Pregnant women’s knowledge, attitude, practice, and barriers associated with the uptake of influenza vaccination: a systematic review. Health Provid. 2023;3(1):37–54.

- Smith S, Sim J, Halcomb E. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding influenza vaccination: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2016;25(19–20):2730–44. 21. [CrossRef]

- Dhaouadi S, Kharroubi G, Cherif A, Cherif I, Bouguerra H, Bouabid L, et al. Knowledge attitudes and practices toward seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women during the 2018/2019 influenza season in Tunisia. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(3): e0265390. 22.

- Morales KF, Menning L, Lambach P. The Faces of Influenza Vaccine Recommendation: A Literature Review of the determinants and barriers to health providers’ recommendation of influenza vaccine in pregnancy. Vaccine. 2020;38(31):4805–15. 23. [CrossRef]

- Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, Wichmann O. Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine. 2014; 32(33):4131-9. 24. [CrossRef]

- Bödeker B, Betsch C, Wichmann O. Skewed risk perceptions in pregnant women: the case of influenza vaccination. BMC public health. 2015 Dec;15(1):1-1. [CrossRef]

- Maltezou HC, Koutroumanis PP, Kritikopoulou C, Theodoridou K, Katerelos P, Tsiaousi I, et al. Knowledge about influenza and adherence to the recommendations for influenza vaccination of pregnant women after an educational intervention in Greece. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(5):1070-4. [CrossRef]

- Tuells J, Rodríguez-Blanco N, Torrijos JL, Vila-Candel R, Bonmati AN. Vaccination of pregnant women in the Valencian Community during the 2014-15 influenza season: a multicentre study. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31(4):344.

- Vila-Candel R, Navarro-Illana P, Navarro-Illana E, Castro-Sánchez E, Duke K, Soriano-Vidal FJ, et al. Determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women in Valencia, Spain. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Castillo E, Patey A, MacDonald N. Vaccination in pregnancy: Challenges and evidence-based solutions. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021; 76:83-95. [CrossRef]

- Prospero E, Galmozzi S, Paris V, Felici G, Barbadoro P, D’Alleva A, et al. Factors influencing refusal of flu vaccination among pregnant women in Italy: Healthcare workers’ role. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2019;13(2):201-7. [CrossRef]

- Maurici M, Dugo V, Zaratti L, Paulon L, Pellegrini MG, Baiocco E, et al. Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women toward flu vaccination: a cross-sectional survey. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(19):3147-50. [CrossRef]

- Bergenfeld I, Nganga S, Andrews C, Fenimore V, Otieno N, Wilson A, et al. Provider perspectives on demand creation for maternal vaccines in Kenya. Gates Open Res. 2018;2(34). [CrossRef]

- Marcus JA. Patient-physician relationships. In: Philosophy and Medicine. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008. p. (Humanizing Modern Medicine, vol 99).

- Barnard J, Dempsey A, Brewer S, Pyrzanowski J, Mazzoni S, O’Leary S. Facilitators and barriers to the use of standing orders for vaccination in obstetrics and gynecology settings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):69. e1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman J, Attwell K, Hauck Y, Omer S, Danchin M. Vaccine discussions in pregnancy: interviews with midwives to inform design of an intervention to promote uptake of maternal and childhood vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(11):2534–43. 2. [CrossRef]

- Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, Tazare J, Chico RM, et al. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(7): e0234827. [CrossRef]

- Taksdal SE, Mak DB, Joyce S, Tomlin S, Carcione D, Armstrong PK, Effler PV. Predictors of uptake of influenza vaccination: a survey of pregnant women in Western Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(8):582-6. 4.

- Greyson D, Dubé È, Fisher WA, Cook J, Sadarangani M, Bettinger JA. Understanding influenza vaccination during pregnancy in Canada: attitudes, norms, intentions, and vaccine uptake. Health Educ Behav. 2021;48(5). [CrossRef]

- Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:1-7. 2.

- Kaoiean S, Kittikraisak W, Suntarattiwong P, Ditsungnoen D, Phadungkiatwatana P, Srisantiroj N, Asavapiriyanont S, Chotpitayasunondh T, Dawood FS, Lindblade KA. Predictors for influenza vaccination among Thai pregnant women: The role of physicians in increasing vaccine uptake. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2019;13(6):582-92. 3. [CrossRef]

- Alhendyani F, Jolly K, Jones LL. Views and experiences of maternal healthcare providers regarding influenza vaccine during pregnancy globally: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(2): e0263234. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Xie R, Yang C, Rainey J, Song Y, Greene C. Identifying ways to increase seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in China: A qualitative investigation of pregnant women and their obstetricians. Vaccine. 2018;36(23):3315–22. 2. [CrossRef]

- Khan AA, Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, Siddiqui M, Sultana S, Ali AS, Zaidi AK, Omer SB. Influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in urban slum areas, Karachi, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5103–9. [CrossRef]

- Wilson RJ, Chantler T, Lees S, Paterson P, Larson H. The patient–healthcare worker relationship: how does it affect patient views towards vaccination during pregnancy? In: Health and health care concerns among women and racial and ethnic minorities. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2017. p. 59–77. 4.

- Bruno S, Nachira L, Villani L, Beccia V, Di Pilla A, Pascucci D, Quaranta G, Carducci B, Spadea A, Damiani G, Lanzone A. Knowledge and beliefs about vaccination in pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022; 10:903557. 5. [CrossRef]

- Bessi A, Zollo F, Del Vicario M, Puliga M, Scala A, Caldarelli G, et al. Users polarization on Facebook and YouTube. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(8):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Jones CE, Munoz FM, Spiegel HM, Heininger U, Zuber PL, Edwards KM, Lambach P, Neels P, Kohl KS, Gidudu J, Hirschfeld S. Guideline for collection, analysis and presentation of safety data in clinical trials of vaccines in pregnant women. Vaccine. 2016;34(49):5998–6006. [CrossRef]

| Demography | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–22 years | 10 | 3.7 |

| 23–27 years | 50 | 18.4 | |

| 28–32 years | 83 | 30.5 | |

| 33–37 years | 69 | 25.4 | |

| 38–42 years | 45 | 16.5 | |

| > 42 years | 15 | 5.5 | |

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 199 | 73.2 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 73 | 26.8 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 254 | 93.4 |

| Christian | 18 | 6.6 | |

| Buddhism | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Highest level of education | None | 0 | 0.0 |

| Primary school | 4 | 1.5 | |

| Middle school | 13 | 4.8 | |

| High school | 20 | 7.4 | |

| Higher education | 235 | 86.4 | |

| Weeks of pregnancy | 1-13 weeks | 17 | 6.4% |

| 14-26 weeks | 21 | 7.9% | |

| 27-40 weeks | 126 | 47.2% | |

| Recently delivered | 103 | 38.6% | |

| Is this your first pregnancy? | Yes | 70 | 26.3 |

| No | 196 | 73.7 | |

| Received influenza vaccine during current/most recent pregnancy | Yes | 22 | 8.1 |

| No | 250 | 91.9 | |

| Received any vaccines during previous pregnancies (for women with multiple pregnancies) | Yes | 19 | 9.4 |

| No | 93 | 34.19 | |

| Can’t remember | 160 | 79.2 |

| Influenza Prevention Techniques | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Getting the influenza vaccine | Yes | 118 | 43.4 |

| No | 99 | 36.4 | |

| I don’t know. | 55 | 20.2 | |

| Taking vitamin supplements | Yes | 232 | 85.3 |

| No | 25 | 9.2 | |

| I don’t know. | 15 | 5.5 | |

| Eating ginger and/or garlic | Yes | 147 | 54.0 |

| No | 72 | 26.5 | |

| I don’t know. | 53 | 19.5 | |

| Having a healthy lifestyle | Yes | 201 | 73.9 |

| No | 49 | 18.0 | |

| I don’t know. | 22 | 8.1 | |

| Hand washing/hand hygiene | Yes | 249 | 91.5 |

| No | 12 | 4.4 | |

| I don’t know. | 11 | 4.0 | |

| Knowledge score equal to median or below | 160 | 58.8 | |

| Knowledge score above the median | 112 | 41.2 | |

| MIV Knowledge | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza vaccines during pregnancy can protect me from complications from influenza infection, such as hospital admission. | Agree | 91 | 33.5 |

| Disagree | 64 | 23.5 | |

| I don’t know. | 117 | 43.0 | |

| Influenza vaccination during pregnancy can protect my new-born baby against influenza infection during their first months of life | Agree | 58 | 21.3 |

| Disagree | 76 | 27.9 | |

| I don’t know. | 138 | 50.7 | |

| Influenza infection during pregnancy is a serious disease. | Agree | 62 | 22.8 |

| Disagree | 127 | 46.7 | |

| I don’t know. | 83 | 30.5 | |

| Knowledge score equal to or below median | 230 | 92 | |

| Knowledge score above the median | 20 | 8 | |

| Influence of Measures to Enhance MIV Uptake | Median | Q1-Q3 | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| My obstetrician advises me to get vaccinated | 5.0 | 4.0-5.0 | 1.0 |

| I get information on the safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy in the form of posters, leaflets and ministry of health social media channels | 4.0 | 3.0-5.0 | 2.0 |

| I get information about the seriousness of influenza for pregnant women and neonates in the form of posters, leaflets and ministry of health social media channels | 5.0 | 4.0-5.0 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).