Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/ Objectives: Vaccination against influenza and pertussis in pregnant women protects mother and child through the transfer of protective antibo‐ dies across the placenta. However, pregnant women’s vaccine hesitancy is a major barrier to achieve satisfactory vaccination coverage in many developed countries. Methods: Greek pregnant women’s vaccination knowledge, attitudes, and practices were recorded. Sampling across country’s districts was applied to achieve geographic representativeness. Results: Questionnaires from 474 mothers were collected. Their mean age was 34 (±5) years. Vaccination uptake was 16.8% and 45.7%, for pertussis and influenza respectively. During their recent pregnancy, 68.9% and 27.1% of the responders had been informed by their gynecologists regarding influenza and pertussis maternal immunization, respectively, indicating that gynecologists miss to inform a significant rate of pregnant women. According to multiple logistic regression, women who gave birth during spring (OR: 2.29 vs. winter delivery, p=0.042) and those with an MSc or PhD (OR: 2.93 vs. school graduates, p=0.015) were more likely to receive influenza vaccination. Factors favoring influenza vaccination included doctorʹs recommendation (OR: 18.86, p<0.001), being not/somewhat afraid of potential vaccine side effects during pregnancy (OR: 2.09, p=0.012), considering flu as relatively/very dangerous during pregnancy (OR: 8.05, p<0.001), and flu vaccine as relatively/completely safe (OR: 4.37, p<0.001). Doctorʹs recommendation (OR: 29.55, p<0.001) and considering pertussis a relatively/very serious risk to the motherʹs health during pregnancy (OR: 6.00, p=0.002) were factors associated with pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. Conclusions: Education of both expectant mothers and obstetricians is urgently needed to increase immunization coverage during pregnancy. Low influenza vaccination coverage among women delivering during winter and low pertussis immunization rates, in combination with low recommendation rates for both vaccines strongly indicate that Greek obstetricians focus on maternal health alone. Their perspectives play an instrumental role in vaccine acceptance during pregnancy, shaping the immunization inclusion maps.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

Evaluation of Knowledge

3. Results

3.1. Influenza Maternal Vaccination

3.2. Pertussis Maternal Vaccination

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Tdap | tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine |

| KAP study | Knowledge-Attitudes-Practices study |

| CLEO | Collaborative Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Outcomes Research |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| MSc | Master of Science |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| HCP | Healthcare practitioner/provider/professional |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

References

- Orenstein WA, Douglas RG, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR. Immunizations in the United States: success, structure, and stress. Health affairs. 2005;24(3):599-610.

- Smith TC. Vaccine Rejection and Hesitancy: A Review and Call to Action. Open forum infectious diseases. 2017;4(3):ofx146.

- MacDonald NE, Hesitancy SWGoV. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161-4.

- (SAGE SAGoE. meeting of the Strategic advisory group of experts on immunization, april 2014 – conclusions and recommendations. 2014.

- Marshall H, McMillan M, Andrews RM, Macartney K, Edwards K. Vaccines in pregnancy: The dual benefit for pregnant women and infants. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(4):848-56.

- Fouda GG, Martinez DR, Swamy GK, Permar SR. The Impact of IgG transplacental transfer on early life immunity. ImmunoHorizons. 2018;2(1):14-25.

- Regan AK, Munoz FM. Efficacy and safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy: realizing the potential of maternal influenza immunization. Expert review of vaccines. 2021;20(6):649-60.

- Kennedy ED, Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, Lu PJ, Singleton JA, Bridges CB. Monitoring seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S9-16.

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months --- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60(41):1424-6.

- Munoz FM. Safety of influenza vaccines in pregnant women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S33-7.

- Razzaghi H. Influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, April 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020;69.

- Lindley MC. Vital signs: burden and prevention of influenza and pertussis among pregnant women and infants—United States. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019;68.

- Properzi S, Carestia R, Birettoni V, Calesso V, Marinelli B, Scapicchi E, et al. Vaccination of pregnant women: an overview of European policies and strategies to promote it. Frontiers in public health. 2024;12:1455318.

- Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, et al. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295-301.

- Gkentzi D, Katsakiori P, Marangos M, Hsia Y, Amirthalingam G, Heath PT, et al. Maternal vaccination against pertussis: a systematic review of the recent literature. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2017;102(5):F456-F63.

- Neofytou A. Knowledg, Attitudes and Practices of pregnant women regarding maternal pertussis immunization during pregnancy and prevention of congenital infections in Greece, 2019.

- Gkentzi D, Zorba M, Marangos M, Vervenioti A, Karatza A, Dimitriou G. Antenatal vaccination for influenza and pertussis: a call to action. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2021;41(5):750-4.

- Saw SM, Ng TP. The design and assessment of questionnaires in clinical research. Singapore medical journal. 2001;42(3):131-5.

- Taber KS. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education. 2018;48(6):1273-96.

- Homer CSE, Javid N, Wilton K, Bradfield Z. Vaccination in pregnancy: The role of the midwife. Frontiers in global women's health. 2022;3:929173.

- Bharj KK, Luyben A, Avery MD, Johnson PG, Barger MK, Bick D. An agenda for midwifery education: advancing the state of the world׳ s midwifery. Midwifery. 2016;33:3-6.

- Taskou C, Sarantaki A. Knowledge and Attitudes of Healthcare Professionals Regarding Perinatal Influenza Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023;11(1).

- MacDougall DM, Halperin SA. Improving rates of maternal immunization: challenges and opportunities. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(4):857-65.

- Munoz FM, Jamieson DJ. Maternal immunization. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;133(4):739-53.

- Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, Tazare J, Chico RM, Paterson P, et al. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2020;15(7):e0234827.

- Wiley KE, Massey PD, Cooper SC, Wood NJ, Ho J, Quinn HE, et al. Uptake of influenza vaccine by pregnant women: a cross-sectional survey. Medical Journal of Australia. 2013;198(7):373-5.

- Yuen CYS, Tarrant M. Determinants of uptake of influenza vaccination among pregnant women–a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(36):4602-13.

- Alhendyani F, Jolly K, Jones LL. Views and experiences of maternal healthcare providers regarding influenza vaccine during pregnancy globally: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. PloS one. 2022;17(2):e0263234.

- Lutz CS, Carr W, Cohn A, Rodriguez L. Understanding barriers and predictors of maternal immunization: Identifying gaps through an exploratory literature review. Vaccine. 2018;36(49):7445-55.

- Webb H, Street J, Marshall H. Incorporating immunizations into routine obstetric care to facilitate Health Care Practitioners in implementing maternal immunization recommendations. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2014;10(4):1114-21.

- Khalil A, Samara A, Campbell H, Ladhani SN, Amirthalingam G. Recent increase in infant pertussis cases in Europe and the critical importance of antenatal immunizations: We must do better…now. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2024;146:107148.

- Principi N, Bianchini S, Esposito S. Pertussis Epidemiology in Children: The Role of Maternal Immunization. Vaccines. 2024;12(9):1030.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Increase of pertussis cases in the EU/EEA, 8 May 2024. Stockholm: ECDC; 2024. © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, 2024. Catalogue number: TQ-02-24-500-EN-N, ISBN: 978-92-9498-717-4, DOI: 10.2900/831122.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (groups) | |

| <25 | 21 (4.6%) |

| 25-29 | 73 (16.0%) |

| 30-34 | 143 (31.4%) |

| >=35 | 218 (47.9%) |

| Nationality | |

| Greek | 395 (84.2%) |

| Other | 74 (15.8%) |

| Number of children | |

| 1 | 184 (44.2%) |

| 2 | 183 (44.0%) |

| 3 | 40 (9.6%) |

| 4 | 8 (1.9%) |

| 5 | 1 (0.2%) |

| Season of labor | |

| Winter | 103 (23.2%) |

| Spring | 113 (25.4%) |

| Summer | 114 (25.6%) |

| Autumn | 115 (25.8%) |

| Living region | |

| Athens | 169 (37.2%) |

| Another Greek city | 177 (39.2%) |

| Another Greek town | 107 (23.6%) |

| Family state | |

| Unmarried | 28 (6.0%) |

| Married/cohabitation agreement | 435 (92.5%) |

| Divorced/Estranged | 7 (1.5%) |

| Insurance | |

| No | 17 (3.6%) |

| Yes | 451 (96.4%) |

| Are you considered a high-risk group; | |

| No | 414 (97.6%) |

| Yes | 10 (2.4%) |

| Maternal education level | |

| School graduate | 146 (36.7%) |

| Technical school graduate | 81 (20.6%) |

| University graduate | 93 (23.5%) |

| MSc/PhD§ | 76 (19.2%) |

| Mother’s profession | |

| Public worker | 73 (15.4%) |

| Private worker | 203 (42.9%) |

| Free lancer | 70 (14.8%) |

| Unemployed | 56 (11.8%) |

| Other | 71 (15.1%) |

| Healthcare practicioner’s (HCP’s) recommendation regarding influenza vaccination during pregnancy | |

| No | 146 (31.1%) |

| Yes | 324 (68.9%) |

| HCP’s recommendation regarding influenza vaccination during pregnancy | |

| No | 341 (72.9%) |

| Yes | 127 (27.1%) |

| Knowledge score | N=439 |

| Mean [Standard Deviation (SD)] | 7 (2) |

| Median [Interquartile Range (IQR)] | 8 (7-9) |

| Min-Max | 0-9 |

| Knowledge score (categories) | |

| Low/Intermediate | 106 (24.3%) |

| High | 331 (75.7%) |

| Vaccine uptake during pregnancy | Crude Logistic | Adjusted Logistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ration (OR) [95% Confidence Intervals (CI)] | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Infant’s age | 1.33 (0.96-1.83) | - | - | |

| Mean (SD) and Median (IQR) for Women with no Vaccine Uptake (n=214) | 0.7 (0.6) and 0.5 (0.2-0.9) | - | - | - |

| Mean (SD) and Median (IQR) for Women with Vaccine Uptake (n=187) | 0.8 (0.6) and 0.7 (0.3-1.0) | - | - | - |

| n (%) | ||||

| Maternal age (groups) | ||||

| <25 | 5 (23.8%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| 25-29 | 27 (37.0%) | 1.88 (0.62-5.70) | 1.55 (0.30-7.99) | 0.603 |

| 30-34 | 74 (52.1%) | 3.48 (1.21-10.02)* | 2.35 (0.48-11.57) | 0.292 |

| >=35 | 104 (48.1%) | 2.97 (1.05-8.40)* | 1.24 (0.26-5.97) | 0.793 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Greek | 193 (49.2%) | 2.57 (1.48-4.46)* | 1.00 (0.41-2.45) | 0.998 |

| Other | 20 (27.4%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 82 (45.3%) | 1 | - | - |

| 2 | 92 (50.3%) | 1.22 (0.81-1.84) | - | - |

| >=3 | 17 (34.7%) | 0.64 (0.33-1.24) | - | - |

| Season of labor | ||||

| Winter | 50 (48.5%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| Spring | 65 (58.6%) | 2.29 (1.03-5.07)* | 2.29 (1.03-5.07) | 0.042 |

| Summer | 49 (43.0%) | 0.95 (0.45-2.03) | 0.95 (0.45-2.03) | 0.900 |

| Autumn | 40 (35.4%) | 0.59 (0.27-1.29) | 0.59 (0.27-1.29) | 0.189 |

| Living region | ||||

| Athens | 85 (50.9%) | 1 | - | |

| Another Greek city | 75 (42.6%) | 0.72 (0.47-1.10) | - | - |

| Another Greek town | 47 (43.9%) | 0.76 (0.46-1.23) | - | - |

| Family state | ||||

| Unmarried | 7 (25.0%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Married/cohabitation agreement | 204 (47.2%) | 2.68 (1.12-6.45)* | 0.73 (0.18-2.92) | 0.660 |

| Divorced/Estranged | 3 (42.9%) | 2.25 (0.40-12.62) | 1.17 (0.10-14.32) | 0.904 |

| Insurance | ||||

| No | 2 (11.8%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 212 (47.0%) | 6.65 (1.50-29.43)* | 1.27 (0.17-9.40) | 0.814 |

| Are you considered a high-risk group; | ||||

| No | 183 (44.5%) | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 7 (70.0%) | 2.91 (0.74-11.40) | - | - |

| Maternal education level | ||||

| School graduate | 55 (38.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Technical school graduate | 34 (41.5%) | 1.15 (0.66-1.99) | 1.33 (0.58-3.04) | 0.495 |

| University graduate | 53 (42.7%) | 1.21 (0.74-1.97) | 0.98 (0.46-2.10) | 0.958 |

| MSc/PhD§ | 73 (64.6%) | 2.95 (1.77-4.93)* | 2.93 (1.23-7.00) | 0.015 |

| Paternal education level | ||||

| School graduate | 77 (36.8%) | 1 | - | - |

| Technical school graduate | 41 (50.6%) | 1.76 (1.05-2.95)* | - | - |

| University graduate | 51 (54.8%) | 2.08 (1.27-3.42)* | - | - |

| MSc/PhD§ | 42 (56.8%) | 2.25 (1.31-3.86)* | - | - |

| Mother’s profession | ||||

| Public worker | 42 (57.5%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Private worker | 92 (45.8%) | 0.62 (0.36-1.07) | 0.48 (0.21-1.06) | 0.071 |

| Free lancer | 31 (44.9%) | 0.60 (0.31-1.17) | 0.86 (0.31-2.39) | 0.775 |

| Unemployed | 24 (43.6%) | 0.57 (0.28-1.16) | 0.94 (0.31-2.93) | 0.922 |

| Other | 25 (35.2%) | 0.40 (0.20-0.79)* | 0.91 (0.30-2.71) | 0.864 |

| Father’s profession | ||||

| Public worker | 39 (58.2%) | 1 | - | - |

| Private worker | 107 (46.3%) | 0.62 (0.36-1.07) | - | - |

| Free lancer | 56 (40.9%) | 0.50 (0.27-0.90)* | - | - |

| Other | 8 (32.0%) | 0.34 (0.13-0.89)* | - | - |

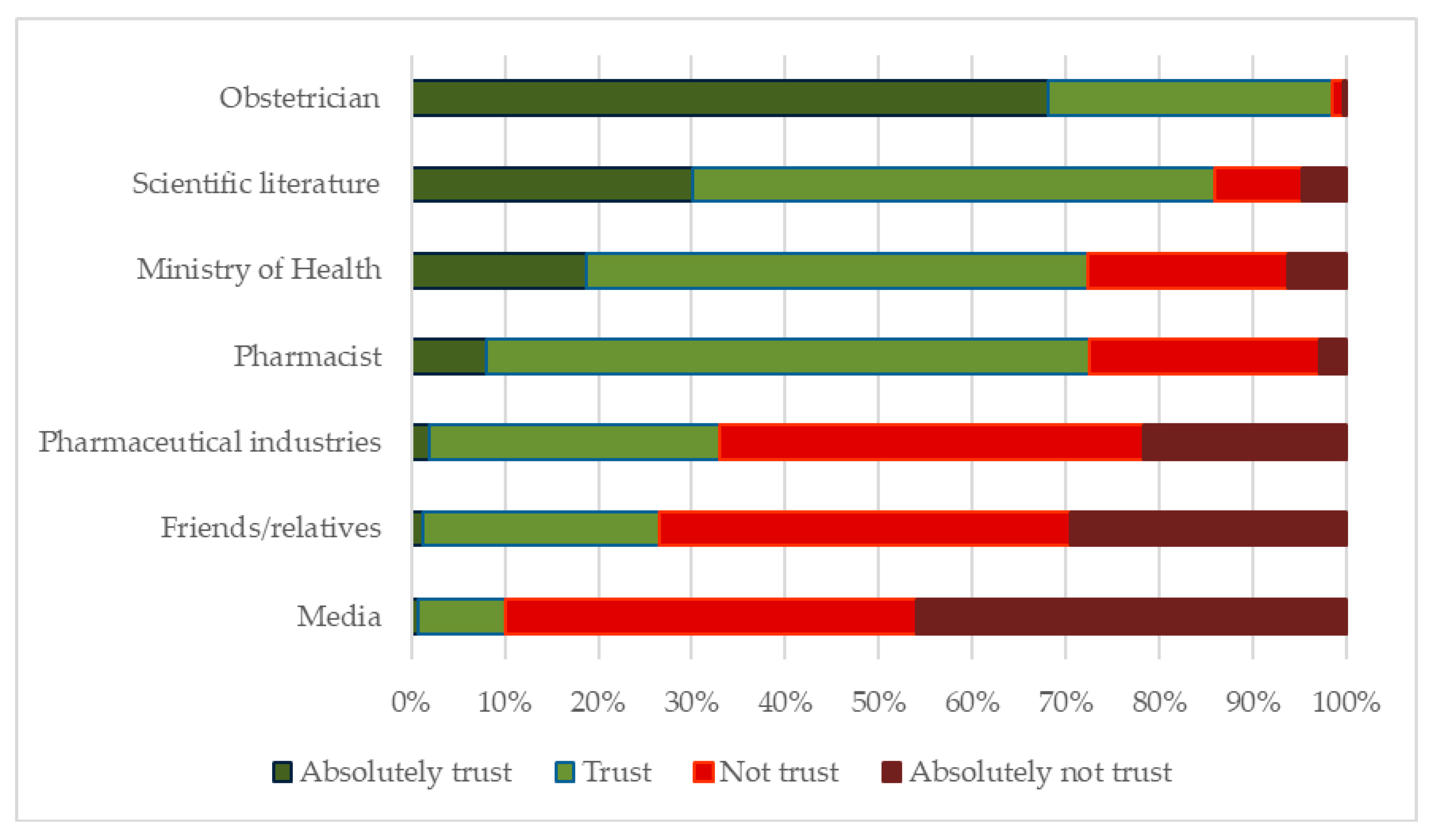

| HCP’s recommendation regarding influenza vaccination during pregnancy | ||||

| No | 13 (9.0%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 201 (62.4%) | 16.87 (9.14-31.13)* | 18.86 (8.61-41.31) | <0.001 |

| Categories Knowledge score | ||||

| Low/Intermediate | 11 (10.4%) | 1 | - | - |

| High | 192 (58.0%) | 11.93 (6.16-23.11)* | - | - |

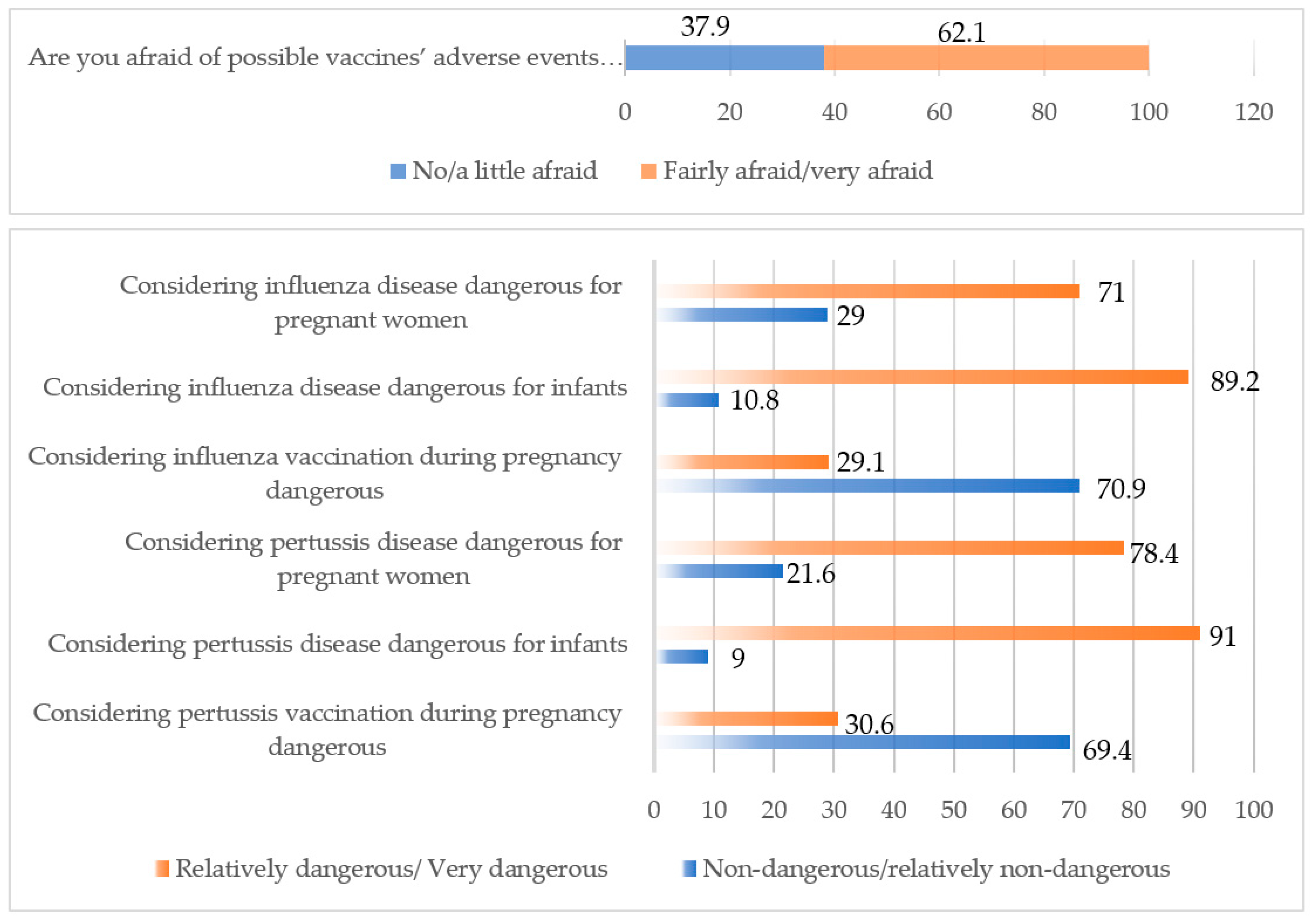

| Are you afraid of possible vaccines’ adverse events during pregnancy | ||||

| No/a little afraid | 104 (58.8%) | 2.39 (1.63-3.50)* | 2.09 (1.18-3.70) | 0.012 |

| Fairly afraid/very afraid | 108 (37.4%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Considering influenza disease dangerous for pregnant women | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 30 (22.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 185 (55.4%) | 4.35 (2.74-6.88)* | 8.05 (3.81-17.03) | <0.001 |

| Considering influenza disease dangerous for infants | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 9 (18.0%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 206 (49.2%) | 4.41 (2.09-9.29)* | 0.89 (0.29-2.72) | 0.838 |

| Considering influenza vaccine dangerous for pregnant women | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 185 (55.9%) | 4.43 (2.80-7.03)* | 4.37 (2.27-8.41) | <0.001 |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 30 (22.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Vaccine uptake during pregnancy | Crude Logistic | Adjusted Logistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Infant’s age | 0.85 (0.54-1.35) | - | - | |

| Mean (SD) and Median (IQR) for Women with no Vaccine Uptake (n=214) | 0.7 (0.6) and 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | - | - | - |

| Mean (SD) and Median (IQR) for Women with Vaccine Uptake (n=187) | 0.7 (0.5) and 0.6 (0.3-0.9) | - | - | - |

| n (%) | ||||

| Maternal age (groups) | ||||

| <25 | 4 (21.0%) | 1 | - | - |

| 25-29 | 10 (13.9%) | 0.60 (0.17-2.20) | - | - |

| 30-34 | 29 (20.4%) | 0.96 (0.30-3.12) | - | - |

| >=35 | 32 (14.9%) | 0.66 (0.21-2.11) | - | - |

| Nationality | ||||

| Greek | 68 (17.5%) | 1.31 (0.64-2.69) | - | - |

| Other | 10 (13.9%) | 1 | - | - |

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 38 (21.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 23 (12.7%) | 0.54 (0.31-0.95)* | 0.55 (0.27-1.14) | 0.111 |

| >=3 | 6 (12.2%) | 0.52 (0.21-1.31) | 0.52 (0.17-1.62) | 0.261 |

| Season of labor | ||||

| Winter | 19 (18.6%) | 1.20 (0.59-2.43) | - | - |

| Spring | 19 (17.3%) | 1.09 (0.54-2.21) | - | - |

| Summer | 17 (14.9%) | 0.92 (0.45-1.88) | - | - |

| Autumn | 18 (16.1%) | 1 | - | - |

| Living region | ||||

| Athens | 29 (17.6%) | 1 | - | - |

| Another Greek city | 35 (20.1%) | 1.18 (0.68-2.04) | - | - |

| Another Greek town | 12 (11.3%) | 0.60 (0.29-1.23) | - | - |

| Family state | ||||

| Unmarried | 3 (10.7%) | - | - | - |

| Married/cohabitation agreement | 75 (17.6%) | - | - | - |

| Divorced/Estranged | 0 (0.0%) | - | - | - |

| Insurance | ||||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | - | - | - |

| Yes | 78 (17.4%) | - | - | - |

| Are you considered a high-risk group; | ||||

| No | 66 (16.2%) | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1 (10.0%) | 0.57 (0.07-4.61) | - | - |

| Maternal education level | ||||

| School graduate | 19 (13.4%) | 1 | - | - |

| Technical school graduate | 19 (23.5%) | 1.98 (0.98-4.02) | - | - |

| University graduate | 19 (15.3%) | 1.17 (0.59-2.33) | - | - |

| MSc/PhD§ | 21 (18.7%) | 1.49 (0.76-2.94) | - | - |

| Paternal education level | ||||

| School graduate | 32 (15.4%) | 1 | - | - |

| Technical school graduate | 16 (20.0%) | 1.38 (0.71-2.67) | - | - |

| University graduate | 17 (18.5%) | 1.25 (0.65-2.38) | - | - |

| MSc/PhD§ | 12 (16.4%) | 1.08 (0.52-2.23) | - | - |

| Mother’s profession | ||||

| Public worker | 9 (12.7%) | 1 | - | - |

| Private worker | 38 (19.0%) | 1.62 (0.74-3.54) | - | - |

| Free lancer | 10 (14.5%) | 1.17 (0.44-3.08) | - | - |

| Unemployed | 10 (18.9%) | 1.60 (0.60-4.27) | - | - |

| Other | 11 (15.5%) | 1.26 (0.49-3.26) | - | - |

| Father’s profession | ||||

| Public worker | 13 (19.4%) | 1 | - | - |

| Private worker | 39 (17.2%) | 0.86 (0.43-1.73) | - | - |

| Free lancer | 21 (15.3%) | 0.75 (0.35-1.61) | - | - |

| Unemployed | 4 (16.7%) | 0.83 (0.24-2.85) | - | - |

| Other | 13 (19.4%) | 1 | - | - |

| HCP’s recommendation regarding pertussis vaccination during pregnancy | ||||

| No | 14 (4.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 64 (52.0%) | 25.03 (13.18-47.53) | 29.55 (14.11-61.92) | <0.001* |

| Categories Knowledge score | ||||

| Low/Intermediate | 4 (3.8%) | 1 | ||

| High | 71 (21.6%) | 6.95 (2.47-19.52)* | ||

| Are you afraid of possible vaccines’ adverse events during pregnancy | ||||

| No/a little afraid | 38 (21.6%) | 1.74 (1.06-2.84)* | 1.85 (0.93-3.67) | 0.081 |

| Fairly afraid/very afraid | 39 (13.7%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Considering pertussis disease dangerous for pregnant women | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 5 (5.1%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 73 (20.2%) | 4.71 (1.85-12.02)* | 6.00 (1.89-19.05) | 0.002* |

| Considering pertussis disease dangerous for infants | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 3 (7.3%) | 1 | - | - |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 75 (17.9%) | 2.77 (0.83-9.21) | - | - |

| Considering pertussis vaccine dangerous for pregnant women | ||||

| Non-dangerous/relatively non-dangerous | 61 (19.1%) | 1.72 (0.97-3.08) | - | - |

| Relatively dangerous/ Very dangerous | 17 (12.1%) | 1 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).