Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

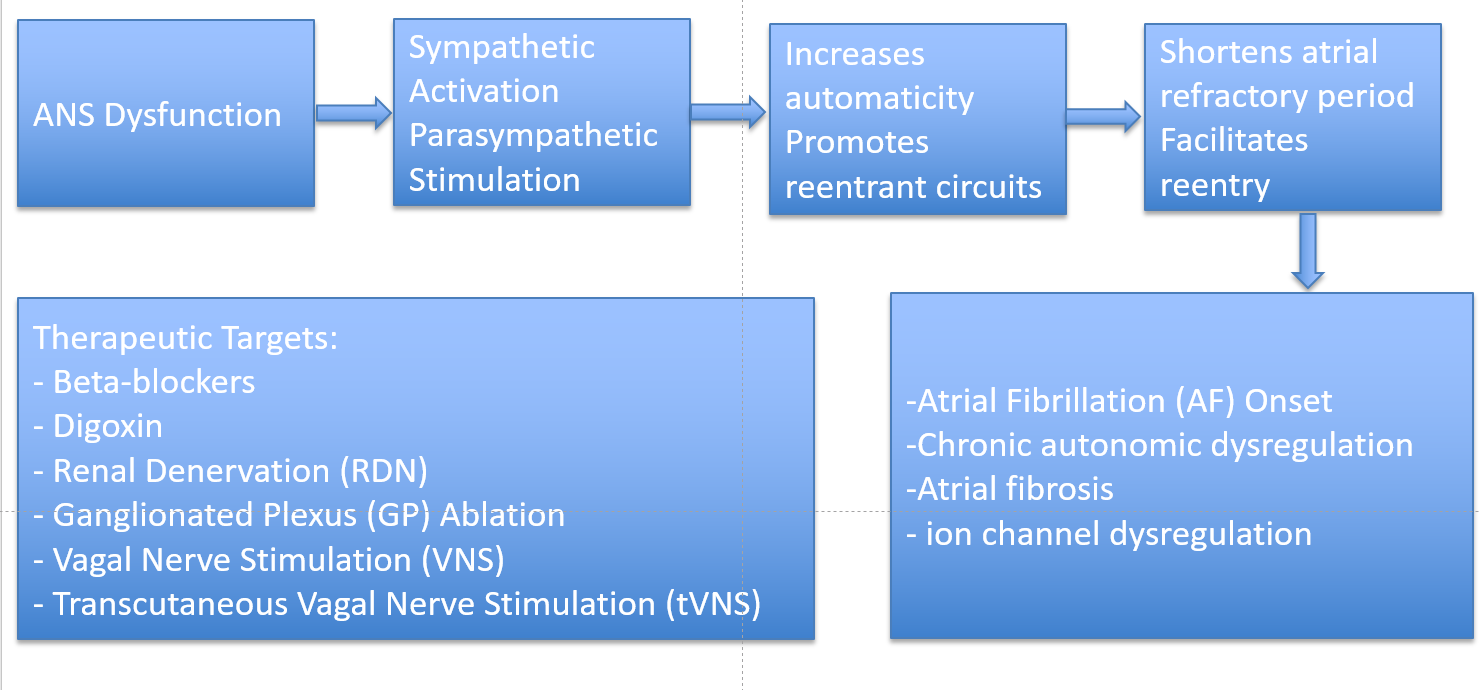

Sympathovagal Interactions in AF

Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and Atrial Fibrillation

Parasympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and Atrial Fibrillation

Mechanistic Insights (Fibrosis, Ion Channels, Ganglia)

Neural Remodeling and Atrial Fibrosis

Role of the Cardiac Autonomic Ganglia

Therapeutic Targets Modulating the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) in Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

Established Pharmacological Modulation (Beta-blockers, Digoxin)

Catheter-Based Autonomic Modulation

Renal denervation (RDN)

Ganglionated Plexi (GP) Ablation

Neuromodulation Therapies

Stellate Ganglion Modulation

Vagal Modulation Strategies

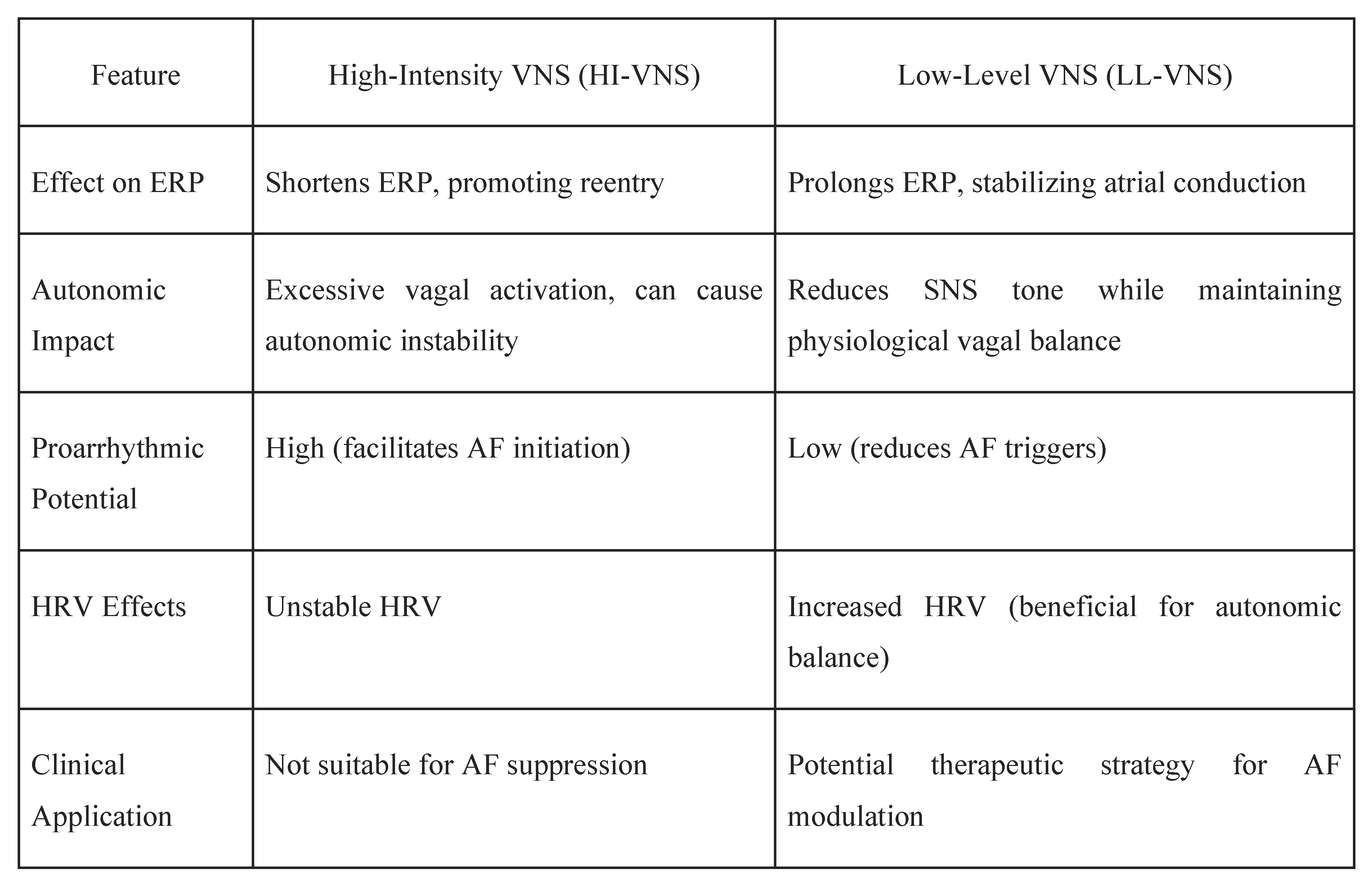

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS)

- Modulation of systemic inflammation, with evidence suggesting reductions in inflammatory markers that are known to contribute to atrial fibrosis and AF persistence [51].

Clinical Evidence Supporting tVNS in AF

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Li X, Liu Z, Jiang X, Xia R, Li Y, Pan X, Yao Y, Fan X. Global, regional, and national burdens of atrial fibrillation/flutter from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis using the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. J Glob Health. 2023 Nov 22;13:04154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndakotsu A, Dwumah-Agyen M, Patel M. The bidirectional relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation: Pathophysiology, diagnostic challenges, and strategies - A narrative review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024 Dec;49(12):102873. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linz D, Elliott AD, Hohl M, Malik V, Schotten U, Dobrev D, Nattel S, Böhm M, Floras J, Lau DH, Sanders P. Role of autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2019 Jul 15;287:181-188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnagarin R, Kiuchi MG, Ho JK, Matthews VB, Schlaich MP. Sympathetic Nervous System Activation and Its Modulation: Role in Atrial Fibrillation. Front Neurosci. 2019 Jan 23;12:1058. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen PS, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Nattel S. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2014 Apr 25;114(9):1500-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberk B, Haemers P, Morillo C. The autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation-pathophysiology and non-invasive assessment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024 Jan 4;10:1327387. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gussak G, Pfenniger A, Wren L, Gilani M, Zhang W, Yoo S, Johnson DA, Burrell A, Benefield B, Knight G, Knight BP, Passman R, Goldberger JJ, Aistrup G, Wasserstrom JA, Shiferaw Y, Arora R. Region-specific parasympathetic nerve remodeling in the left atrium contributes to creation of a vulnerable substrate for atrial fibrillation. JCI Insight. 2019 Oct 17;4(20):e130532. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksu T, Skeete JR, Huang HH. Ganglionic Plexus Ablation: A Step-by-step Guide for Electrophysiologists and Review of Modalities for Neuromodulation for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2023 Jan;12:e02. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zicha S, Tsuji Y, Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Nattel S. Beta-blockers as antiarrhythmic agents. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;(171):235-66. [PubMed]

- Yang Z, Qi X, Li G, Wu N, Qi B, Yuan M, Wang Y, Hu G, Yang Q. The type of exercise most beneficial for quality of life in people with atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025 Jan 9;11:1509304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scridon, A. Autonomic imbalance and atrial ectopic activity-a pathophysiological and clinical view. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1058427. Published 2022 Dec 2. [CrossRef]

- Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):659-666. [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi M, De Ruvo E, Sgueglia M, Lavalle C, Canestrelli S, Politano A, Jacomelli I, Golia P, Crescenzi C, De Luca L, Panuccio M, Fagagnini A, Calò L. Atrial fibrillation and sympatho-vagal imbalance: from the choice of the antiarrhythmic treatment to patients with syncope and ganglionated plexi ablation. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2023 Apr 26;25(Suppl C):C1-C6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denham NC, Pearman CM, Caldwell JL, et al. Calcium in the Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1380. Published 2018 Oct 4. [CrossRef]

- Călburean PA, Osório TG, Sieira J, et al. High parasympathetic activity as reflected by deceleration capacity predicts atrial fibrillation recurrence after repeated catheter ablation procedure. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021;60(1):21-29. [CrossRef]

- Nattel S, Burstein B, Dobrev D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008 Apr;1(1):62-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asuka E, Arole O, Ndakotsu A. Extensive Atrial Fibrosis and Recalcitrant Atrial Fibrillation: A Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Cureus. 2025;17(2):e79169. Published 2025 Feb 17. [CrossRef]

- Wu CH, Hu YF, Chou CY, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 level and outcome after catheter ablation for nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(1):10-15. [CrossRef]

- Molenaar P, Christ T, Ravens U, Kaumann A. Carvedilol blocks beta2- more than beta1-adrenoceptors in human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(1):128-139. [CrossRef]

- Pasternak B, Svanström H, Melbye M, Hviid A. Association of treatment with carvedilol vs metoprolol succinate and mortality in patients with heart failure [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Nov;174(11):1875]. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1597-1604. [CrossRef]

- Lund LH, Benson L, Dahlström U, Edner M, Friberg L. Association between use of β-blockers and outcomes in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JAMA. 2014;312(19):2008-2018. [CrossRef]

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, Deswal A, Eckhardt LL, Goldberger ZD, Gopinathannair R, Gorenek B, Hess PL, Hlatky M, Hogan G, Ibeh C, Indik JH, Kido K, Kusumoto F, Link MS, Linta KT, Marcus GM, McCarthy PM, Patel N, Patton KK, Perez MV, Piccini JP, Russo AM, Sanders P, Streur MM, Thomas KL, Times S, Tisdale JE, Valente AM, Van Wagoner DR; Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024 Jan 2;149(1):e1-e156. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, Di Lenarda A, Hanrath P, Komajda M, Lubsen J, Lutiger B, Metra M, Remme WJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Scherhag A, Skene A; Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial Investigators. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003 Jul 5;362(9377):7-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp-Pedersen C, Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of metoprolol and carvedilol on cause-specific mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure--COMET. Am Heart J. 2005;149(2):370-376. [CrossRef]

- Bristow MR, Gilbert EM, Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fowler MB, Hershberger RE, Kubo SH, Narahara KA, Ingersoll H, Krueger S, Young S, Shusterman N. Carvedilol produces dose-related improvements in left ventricular function and survival in subjects with chronic heart failure. MOCHA Investigators. Circulation. 1996 Dec 1;94(11):2807-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, C. The role of nebivolol in the management of hypertensive patients: from pharmacological profile to treatment guidelines. Future Cardiol. 2021;17(8):1421-1433. [CrossRef]

- Kitzman DW, Sahadevan J, Higginbotham MB, et al. Effect of Nebivolol on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

- Tieleman RG, Blaauw Y, Van Gelder IC, De Langen CD, de Kam PJ, Grandjean JG, Patberg KW, Bel KJ, Allessie MA, Crijns HJ. Digoxin delays recovery from tachycardia-induced electrical remodeling of the atria. Circulation. 1999 Oct 26;100(17):1836-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiade M, Adams KF Jr, Colucci WS. Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2004 Jun 22;109(24):2959-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane AD, Militello M, Faulx MD. Digoxin is still useful, but is still causing toxicity. Cleve Clin J Med. 2024 Aug 1;91(8):489-499. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg JS, Shabanov V, Ponomarev D, Losik D, Ivanickiy E, Kropotkin E, Polyakov K, Ptaszynski P, Keweloh B, Yao CJ, Pokushalov EA, Romanov AB. Effect of Renal Denervation and Catheter Ablation vs Catheter Ablation Alone on Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence Among Patients With Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation and Hypertension: The ERADICATE-AF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020 Jan 21;323(3):248-255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atti V, Turagam MK, Garg J, Lakkireddy D. Renal sympathetic denervation improves clinical outcomes in patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation and history of hypertension: A meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019 May;30(5):702-708. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawar K, Mohammad A, Johns EJ, Abdulla MH. Renal denervation for atrial fibrillation: a comprehensive updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2022 Oct;36(10):887-897. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt DL, Vaduganathan M, Kandzari DE, et al. Long-term outcomes after catheter-based renal artery denervation for resistant hypertension: final follow-up of the randomised SYMPLICITY HTN-3 Trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10361):1405-1416. [CrossRef]

- Arora R, Doshi S, Wilber DJ. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and targets for catheter ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2017;50(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Patterson E, Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Lazzara R. Triggered firing in pulmonary veins initiated by in vitro autonomic nerve stimulation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(6):624-631. [CrossRef]

- Gordon D, Kim S, Brooks AG, Sugumar H, Lau DH, Sanders P. Autonomic Modulation in Atrial Fibrillation: Where Are We in 2021? Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30(10):1516-1525. [CrossRef]

- Oh S, Zhang Y, Bibevski S, Marrouche NF, Natale A, Mazgalev TN. Vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: role of the posterior left atrium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(4):366-374. [CrossRef]

- Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Corbucci G, Artyomenko S, Turov A, Shirokova N, Karaskov A, Steinberg JS. Selective ganglionated plexi ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(9):1257-1264. [CrossRef]

- Driessen AHG, Berger WR, Krul SPJ, et al. Ganglion Plexus Ablation in Advanced Atrial Fibrillation: The AFACT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(11):1155-1165. [CrossRef]

- Katritsis DG, Pokushalov E, Romanov A, et al. Autonomic denervation added to pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(24):2318-2325. [CrossRef]

- Duytschaever M, Demolder A, El Haddad M, et al. Ganglionated Plexi Ablation Added to Pulmonary Vein Isolation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: A Multicenter Randomized Trial (GAPP-AF). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(28):2841-2849. [CrossRef]

- Lei Q, Jiang Z, Shao Y, Liu X, Li X. Stellate ganglion, inflammation, and arrhythmias: a new perspective on neuroimmune regulation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1453127. Published 2024 Sep 12. [CrossRef]

- Shen MJ, Zipes DP. Role of the autonomic nervous system in modulating cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2014;114(6):1004-1021. [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi M, Shivkumar K. The role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;50(6):404-419. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa H, Scherlag BJ, Patterson E, Ikeda A, Lockwood D, Jackman WM. Pathophysiologic basis of autonomic ganglionated plexus ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(12 Suppl):S26-S34. [CrossRef]

- Groenendyk J, Mandler A, Luan D, et al. Management of Rapid Atrial Fibrillation Using Stellate Ganglion Blockade. JACC Case Rep. 2024;29(18):102530. Published 2024 Sep 18. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Scherlag BJ, Yu L, Sheng X, Zhang Y, Ali R, Dong Y, Ghias M, Po SS. Low-level vagosympathetic stimulation: a paradox and potential new modality for the treatment of focal atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Dec;2(6):645-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakis S, Humphrey MB, Scherlag BJ, et al. Low-level transcutaneous electrical vagus nerve stimulation suppresses atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(9):867-875. [CrossRef]

- Stavrakis S, Stoner JA, Humphrey MB, et al. TREAT AF (Transcutaneous Electrical Vagus Nerve Stimulation to Suppress Atrial Fibrillation): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6(3):282-291. [CrossRef]

- Premchand RK, Sharma K, Mittal S, Monteiro R, Dixit S, Libbus I, DiCarlo LA, Ardell JL, Rector TS, Amurthur B, KenKnight BH, Anand IS. Autonomic regulation therapy via left or right cervical vagus nerve stimulation in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the ANTHEM-HF trial. J Card Fail. 2014 Nov;20(11):808-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongkees BJ, Immink MA, Finisguerra A, Colzato LS. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (tVNS) Enhances Response Selection During Sequential Action. Front Psychol. 2018 Jul 6;9:1159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakis S, Chakraborty P, Farhat K, et al. Noninvasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2024;10(2):346-355. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).