2.3. QSAR and Docking Results

The QSAR evaluation of the SINA-MEM compound compared to its parent molecules shows that it has no expected mutagenicity and carcinogenicity (see

Table 4). Also, it has moderate probability for hepatotoxicity (0.5750) and oral toxicity (0.4847), which is higher than the one of its parents and on pair with the other. It has high probability of intestinal absorption (0.9434) as its parents but lower oral bioavailability (0.5571). The compound has high probability to cross the blood brain barrier (0.9426) as its parents. Its subcellular localization is expected to be the mitochondria.

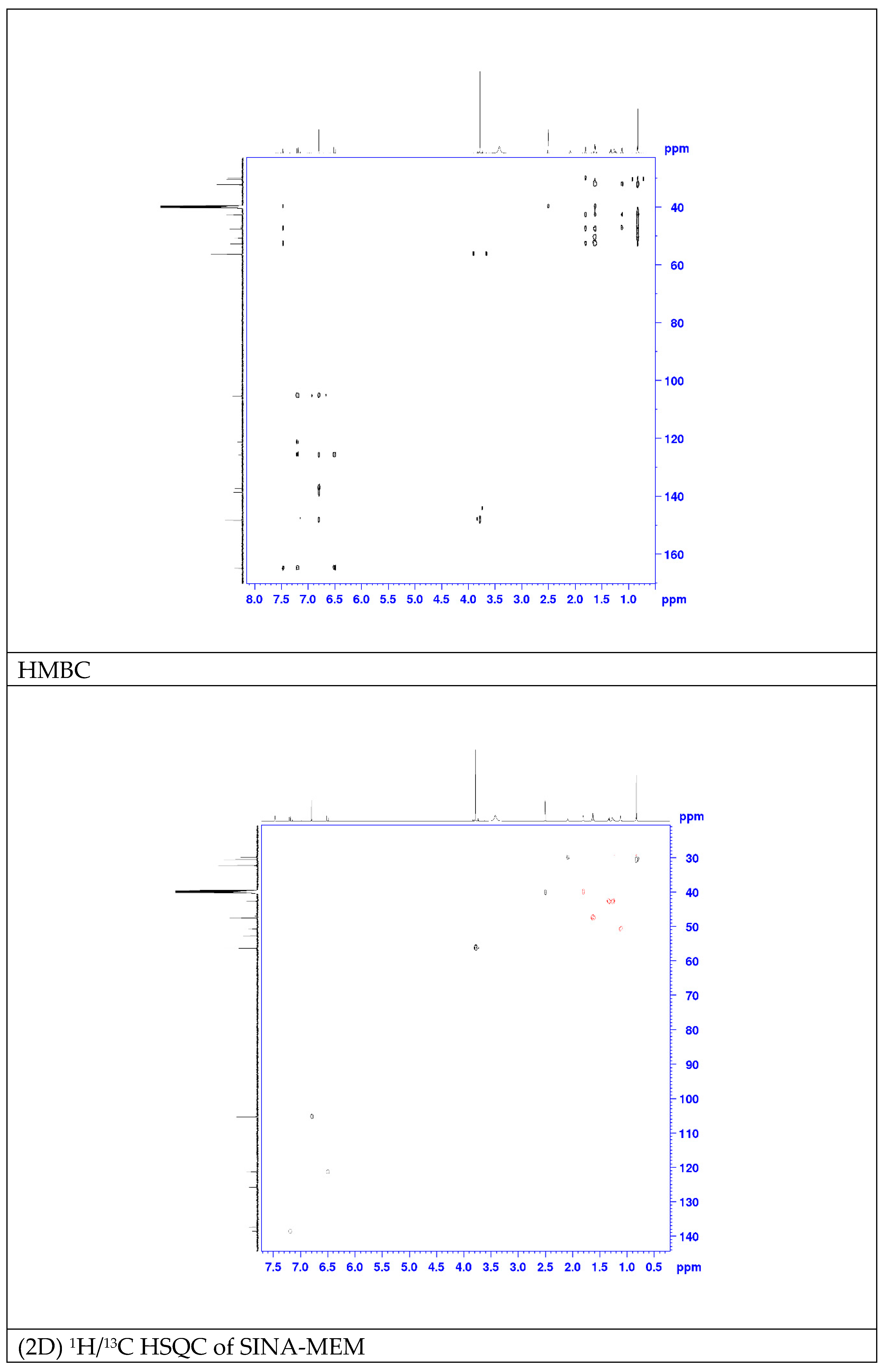

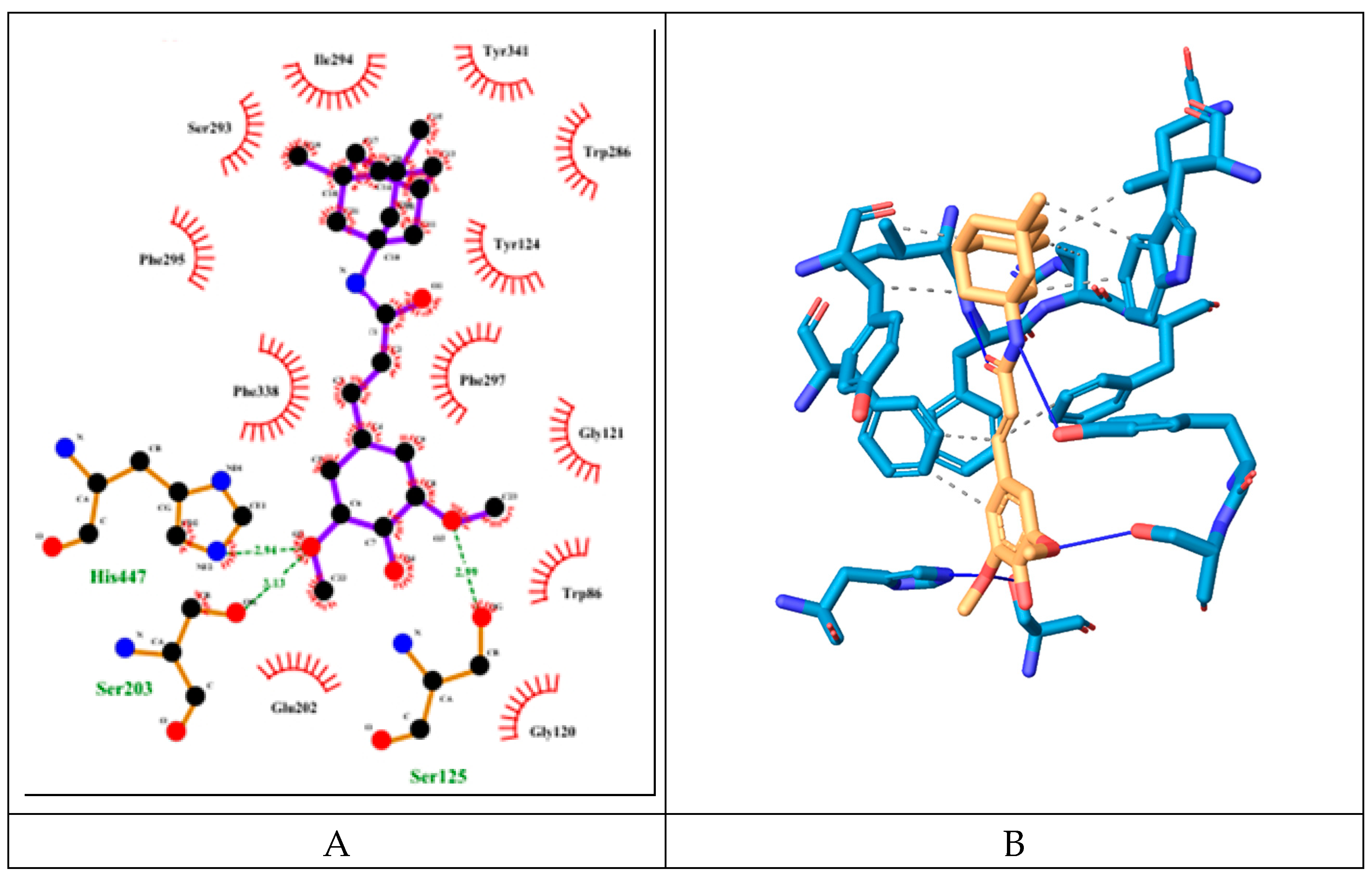

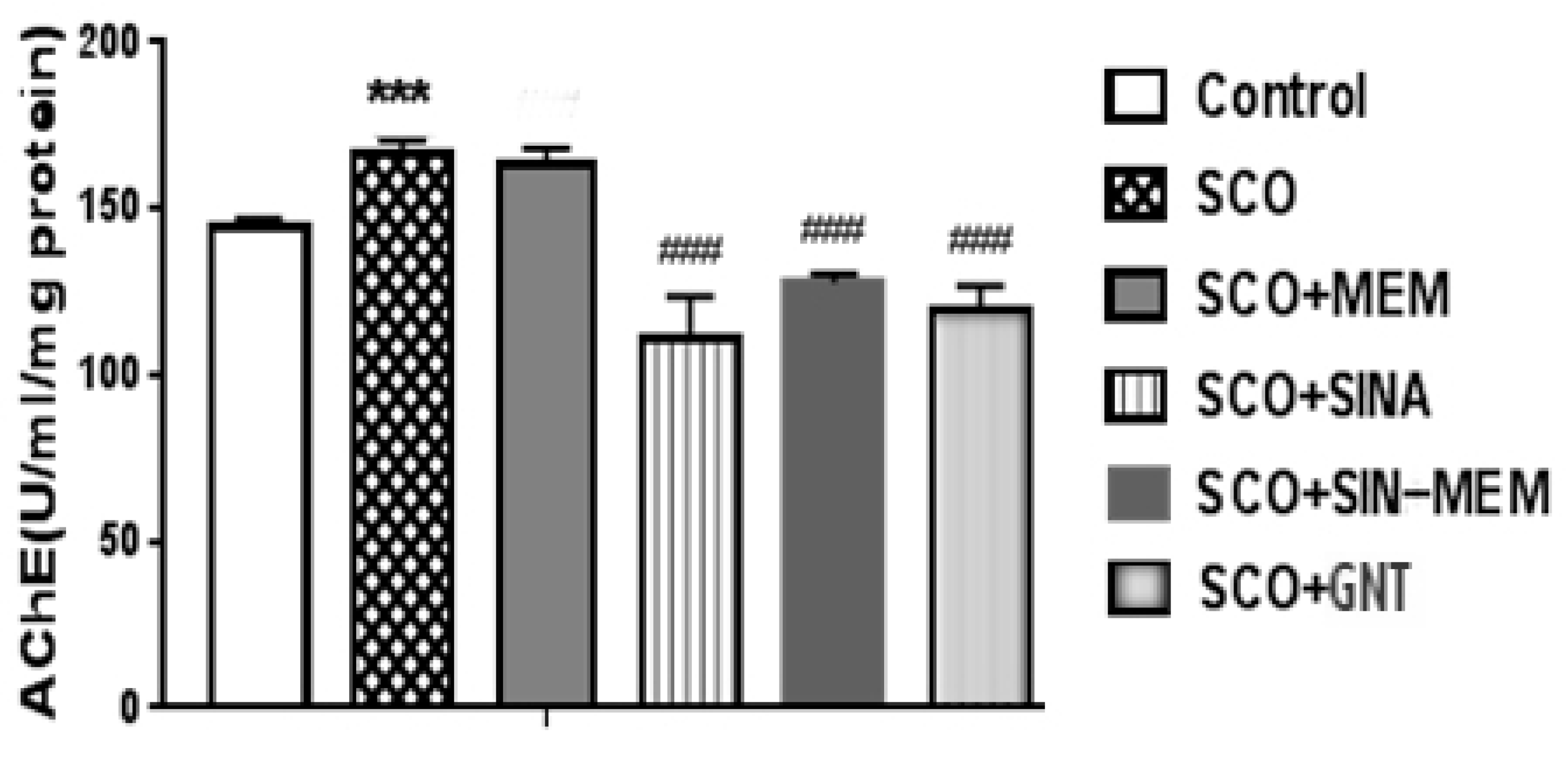

The in silico experiments with molecular docking revealed that all of the tested substances can interact with the active site of one of the key target enzymes in the management of AD – acetylcholinesterase (AChE).

The active site of AChE is unusual one and is deeply recessed at the bottom of a relatively long gorge (approximately 20A) [Deb, et al., 2012]. It can be divided to several subsites each with different amino acid residues namely: a). catalytic triad called also esteratic subsite, encompassing the residues Ser203, His447, Glu334; b). acyl binding pocket (ABP) - Trp236, Phe295, Phe297, Phe338; c). peripheral anionic subsite (PAS) - Asp74, Tyr124, Ser125, Trp286, Tyr337, Tyr341; d). anionic subsite - Trp86, Tyr133, Glu202, Gly448, Ile451; e). oxyanion hole - Gly121, Gly122, Ala204, and other residues of the omega loop (Thr83, Asn87, Pro88) (see

Figure 5). The omega loop is a disulphide-linked loop (Cys69 - Cys96) that covers the active site of AChE, which is buried at the bottom the gorge.

In order to compare the docking results parameters and how the studied substances interact and probably can inhibit the AChE enzyme we used one of the established and clinically approved AChE inhibitors – galantamine – as referent molecule [Atanasova, et al., 2015].

The hybrid molecule has relatively low binding energy of -8.61 kcal/mol and forms several hydrogen bonds with few amino acid residues which are part of the active sites of the enzyme. All of these hydrogen bonds are formed with participation of the oxygen atoms from the sinapoyl moiety. Two of these bonds are with amino acid residues His447 and Ser203 part of the catalytic triad, the other hydrogen bond is with Ser125 (PAS).

The molecule also engages in several hydrophobic interactions with the following AChE amino acid residues (some of them are part of its active sites): Trp286 (PAS), Leu289, Ile294, Arg296, Phe297 (ABP), Phe338 (ABP), Tyr341 (PAS).

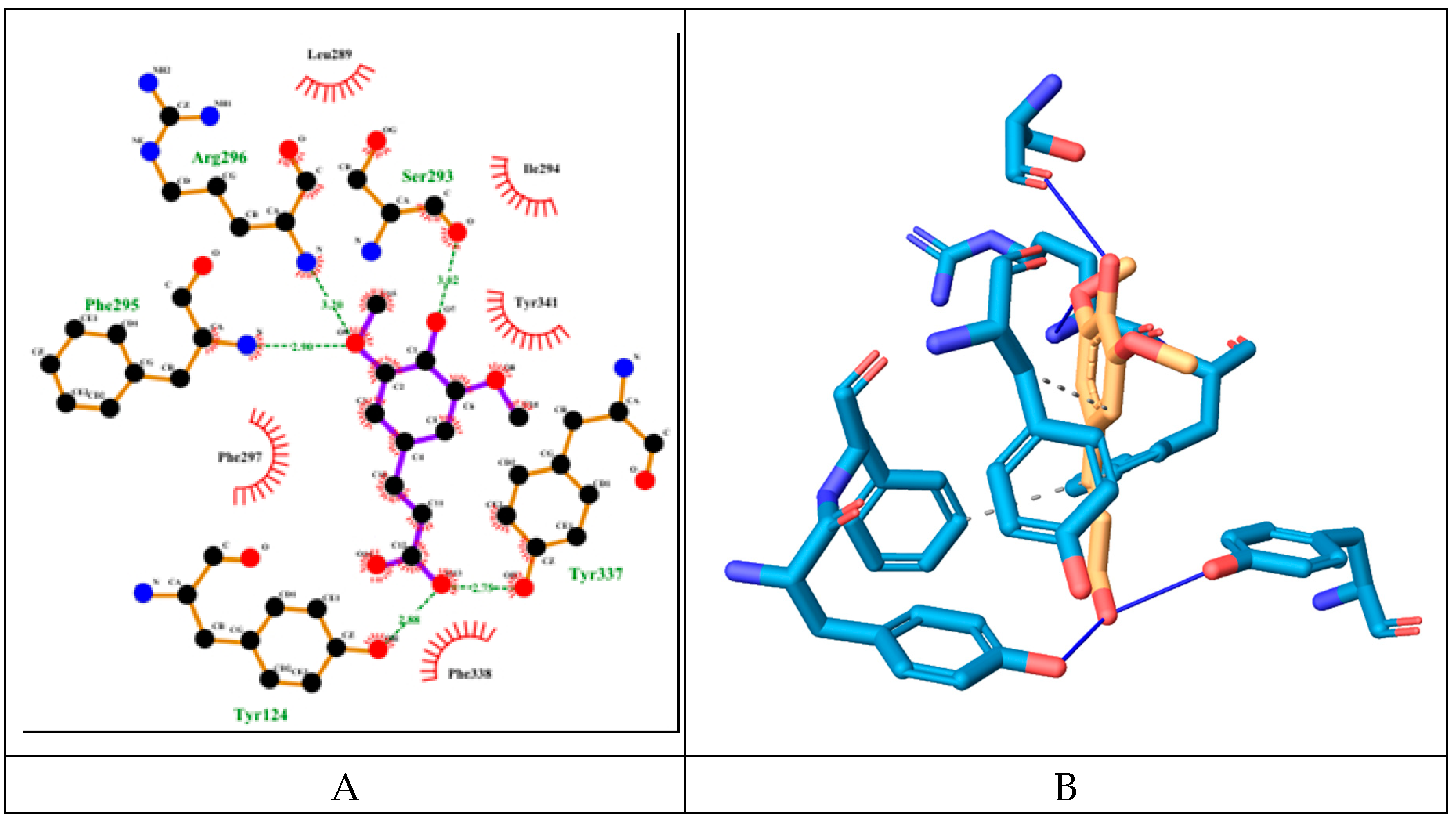

The SINA has binding energy of -5.36 kcal/mol which is higher than the one of the hybrid molecule. However it forms more hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acid residues at the AChE catalytic center (see

Figure 6). These amino acids are Tyr124 (PAS), Ser293, Phe295 (ABP), Arg296, Tyr337 (PAS). It engages in hydrophobic interactions with the following amino acid residues: Phe297 (ABP), Phe338 (ABP), Tyr341 (PAS).

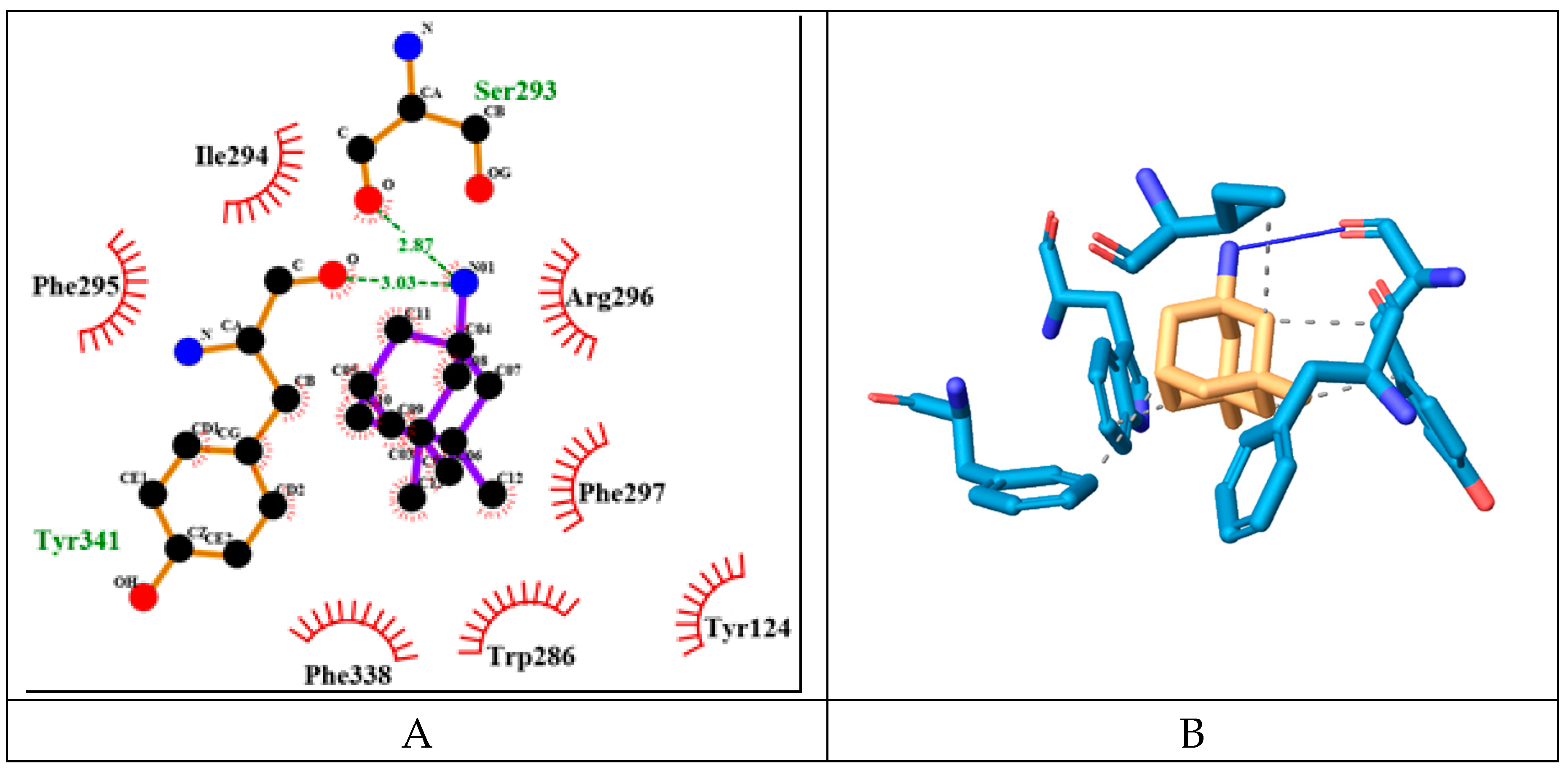

MEM has relatively low binding energy of -8.02 kcal/mol. It forms two hydrogen bonds with Ser293 and Tyr341 (PAS) through its only nitrogen atom (see

Figure 7). It also engages in hydrophobic interactions with Trp286 (PAS), Ile294, Phe297 (ABP), Phe338 (ABP), Tyr341 (PAS).

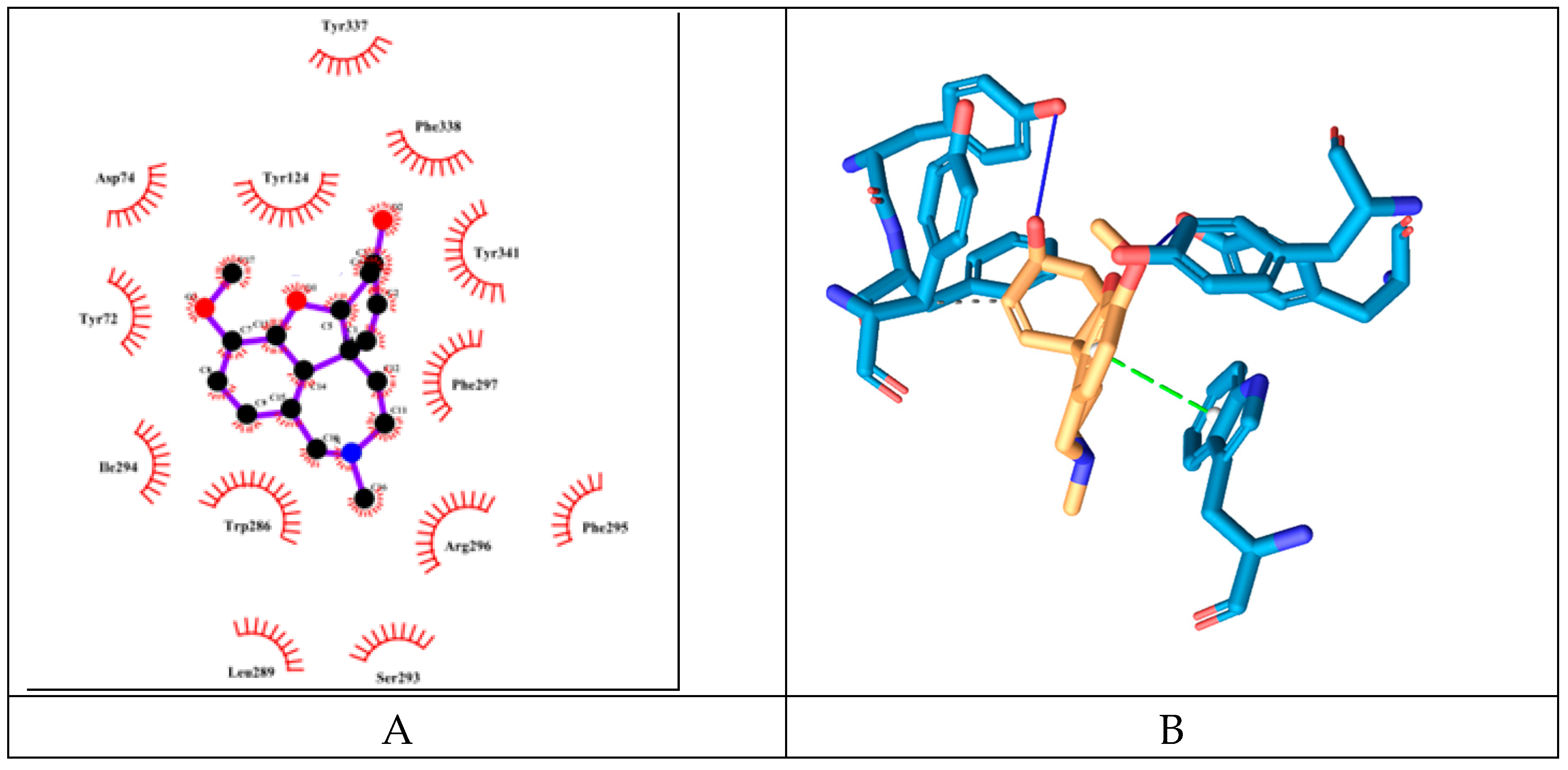

Galantamine has binding energy of -8.79 kcal/mol which is the lowest among the tested molecules. It forms 3 hydrogen bonds (but longer than 3,19A, therefore probably are not counted by the 2D-plotting software). These bonds are with the amino acid moieties Tyr72, Tyr124 (PAS), Tyr337 (PAS) (see

Figure 8). It engages in hydrophobic interactions with Phe338 (ABP), Tyr341 (PAS). However, unlike the other molecules it also interacts through

pi-stacking.

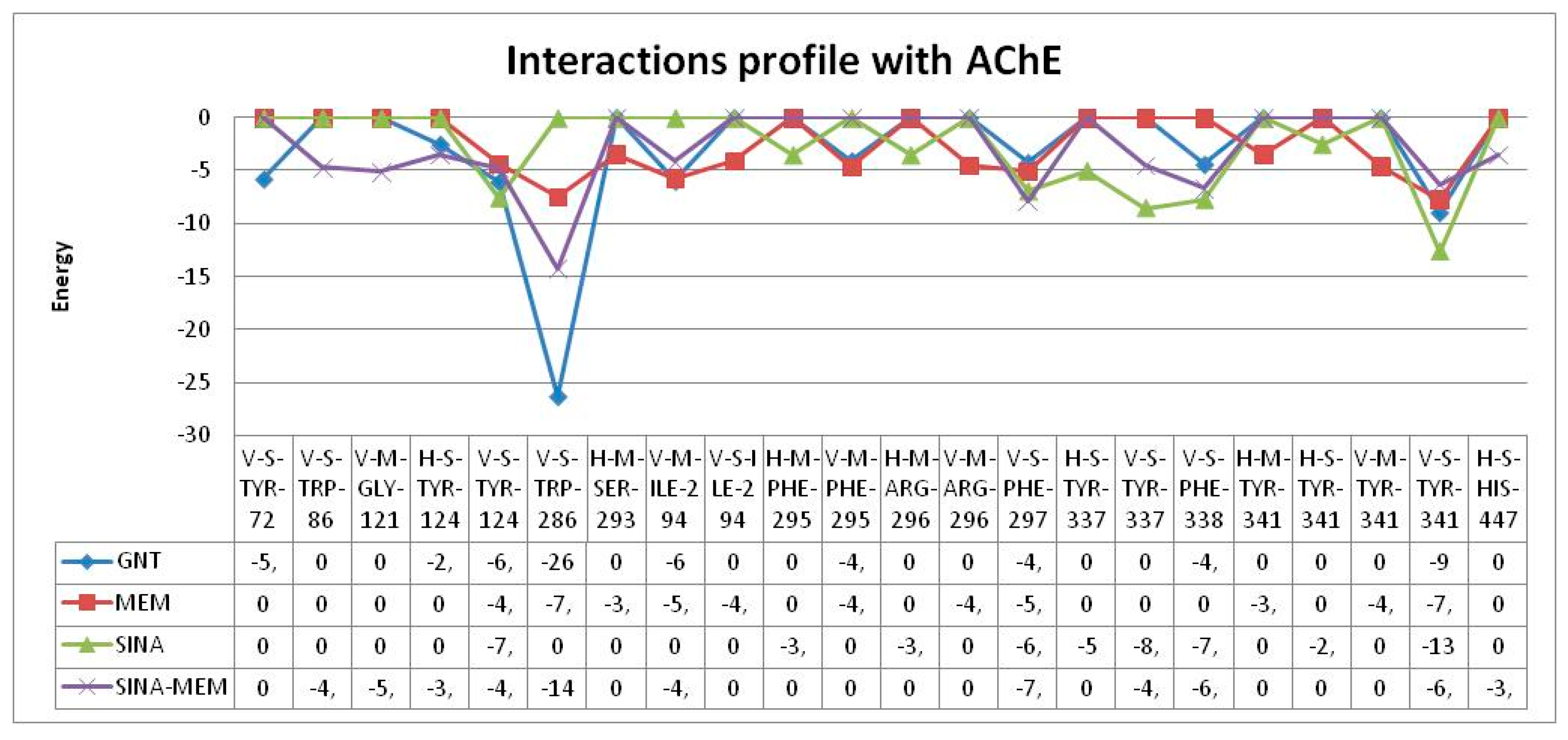

As we can see all of the molecules regardless their similarities interact differently with the active site of AChE. SINA-MEM forms hydrogen bonds with residues from CT and PAS, while SINA forms such bonds with residues from ABP and PAS, and MEM only with residues from PAS. The pattern of hydrophobic interactions also differs. The common residues for SINA-MEM, MEM and SINA are Phe297 (ABP), Phe338 (ABP), Tyr341 (PAS). SINA-MEM interacts with 4 more residues than SINA and with 2 more than Mem.

As for the Galantamine additionally it differs from the rest by the pi-stacking interaction. All of the tested molecules have hydrophobic interactions with Phe338 (ABP) and Tyr341 (PAS). And none of them interacts with the oxyanion hole, anionic subsite and omega loop. Only SINA-MEM interacts with the catalytic triad.

The detailed results of the re-docking experiments generated similar profile of the interaction of the amino-acid residues (see

Figure 9).

Most of the tested compounds have relatively low binding energy below -8.0 kcal/mol. Only SINA has higher value of -5.36 kcal/mol. In comparison the acquired conformations of ACH have binding energy in the range above -4.80 kcal/mol (see

Table 5).

According to Silman and Sussman [Silman & Sussman, 2008] there is narrowing in the middle of the active site gorge, produced by the juxtaposition of Phe330 and Gly121, whose cross-section they estimate to be ∼5 Å. So probably bigger than acetylcholine molecules can pass through such obstacle but only if their 3D structure is planar and/or sufficiently flexible. MEM and its synthesized analogue SINA-MEM are the bulkiest molecules among the tested batch. The approximate distance between the carbon atoms of its methyl moieties is 5 A, similar to the one between the nitrogen in the amino group and the carbons from the methyl groups.

So regardless that the MEM has rather low value of the binding energy of the interaction with the active site of AChE in reality we cannot benefit from such affinity simply because the molecule is spatially obscured with the access to this site.

However, the situation with the other bulky molecule - the MEM hybrid SINA-MEM is different. This molecule comprises of two bulky moieties connected by long carbon chain. Howbeit one of these bulky moieties – the aromatic ring from the sinapic acid – has mostly planar structure and is less likely to be obscured by the gorge narrowing. In fact in all of the found docking conformations for this molecule that bind to the amino acid residues in the AChE active site this moiety is the one inserted in it, while the MEM one remains outside or at its entrance. As it can be seen from the 2D-plotting diagram the sinapic acid moiety is behind the Gly121 amino acid residue, while the MEM one remains outside the active center.

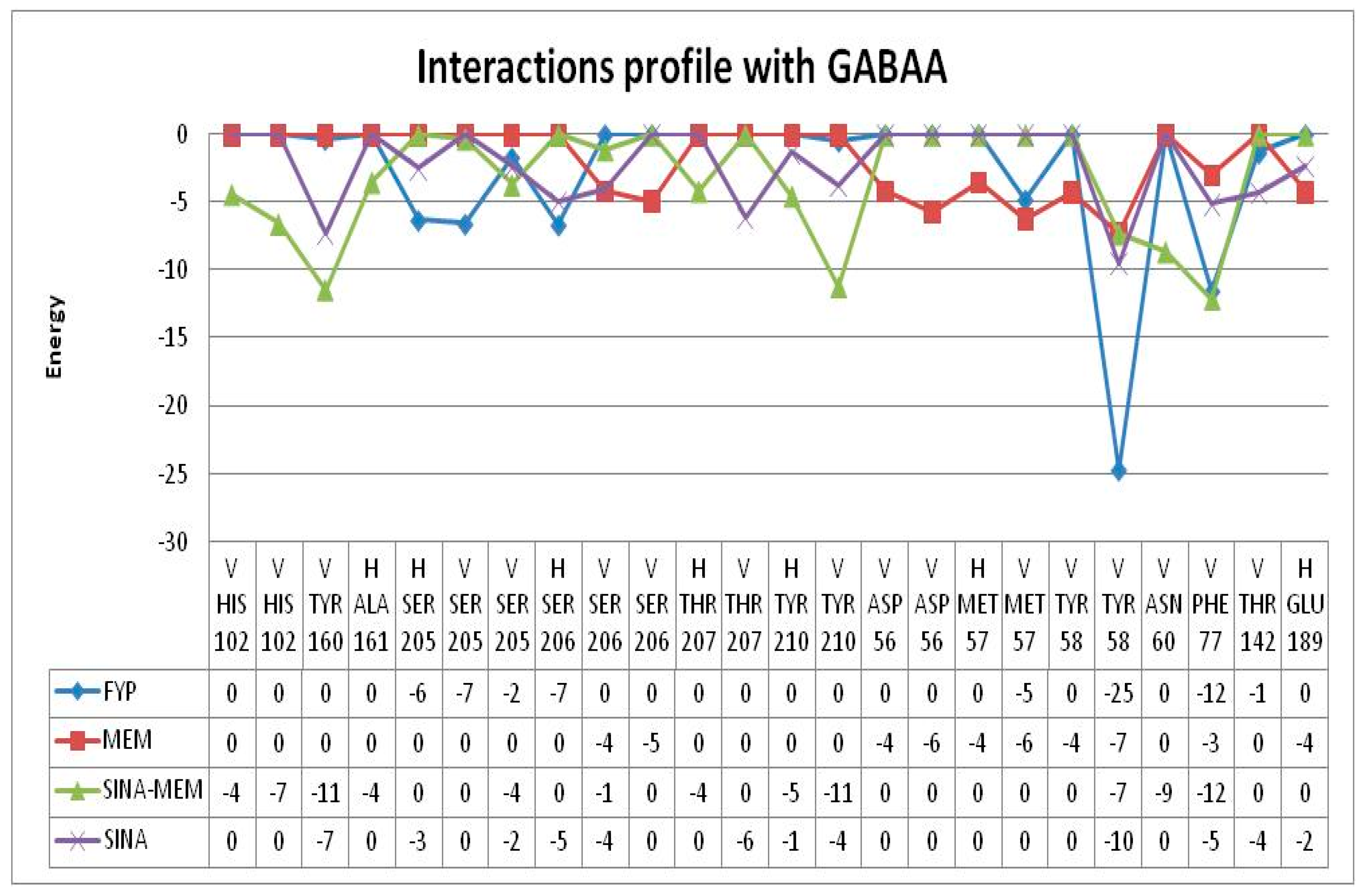

Docking simulations were also performed with another possible molecular target in the brain – the GABAA receptors. These receptors are part of the GLIC-family and form ion channels in the neuronal membranes. Since this type of protein complexes are notoriously hard for study until recently there was no 3D protein structure of them available for the scientific community. Recently the 3D structure of human GABAA receptor was published [Miller & Aricescu, 2014; Zhu et al., 2018], followed by chimera 3D assembly for mouse [Laverty et al., 2017].

The docking with the classic benzodiazepine flumazenil revealed that the ligand binds to the benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors with binding energy of -7.55 kcal/mol.

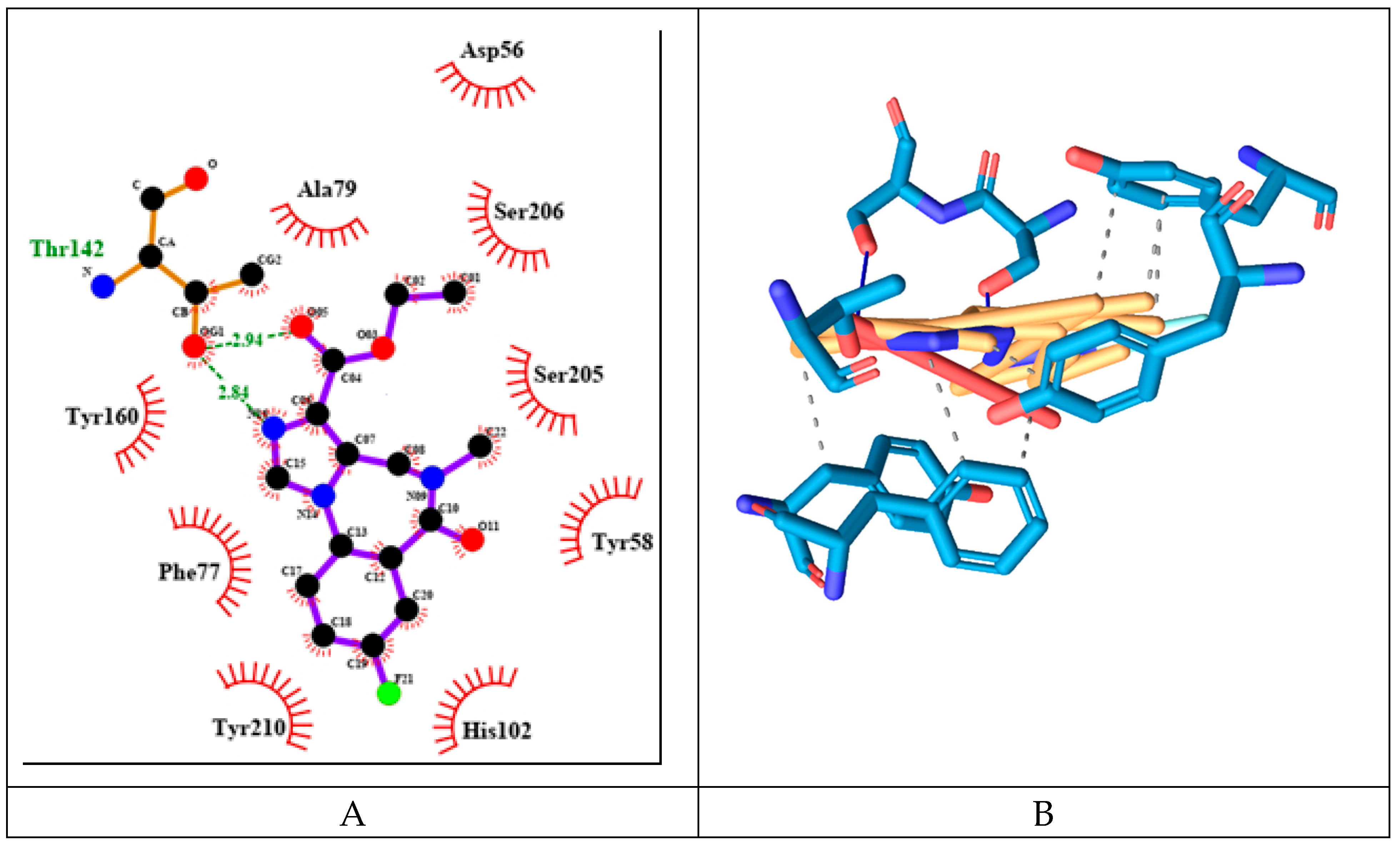

Flumazenil forms with three hydrogen bonds with both protein chains (α and γ) with the following amino acid residues: Thr142γ, Ser205α and Ser206α. It also has 7 hydrophobic interactions with Tyr58γ, Phe77γ, Tyr160α and Tyr210α (see

Figure 10).

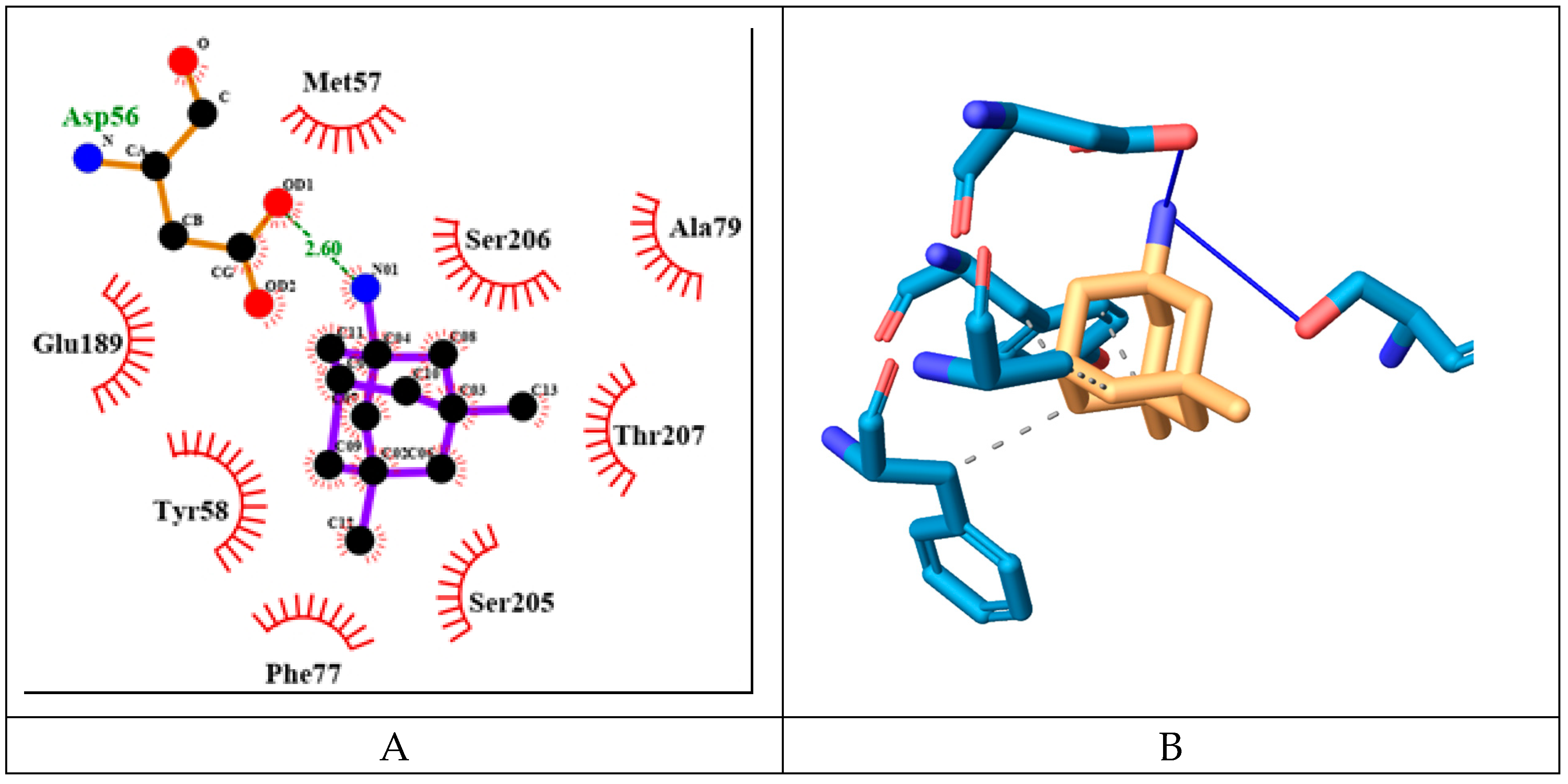

MEM has slightly higher binding energy of -7.37 kcal/mol than flumazenil. It forms fewer hydrogen bonds amino acids from both protein chains namely: Asp56γ and Ser206α (see

Figure 11). It has 4 hydrophobic interactions with amino acids from γ protein chain: Tyr58, Phe77 and Ala79.

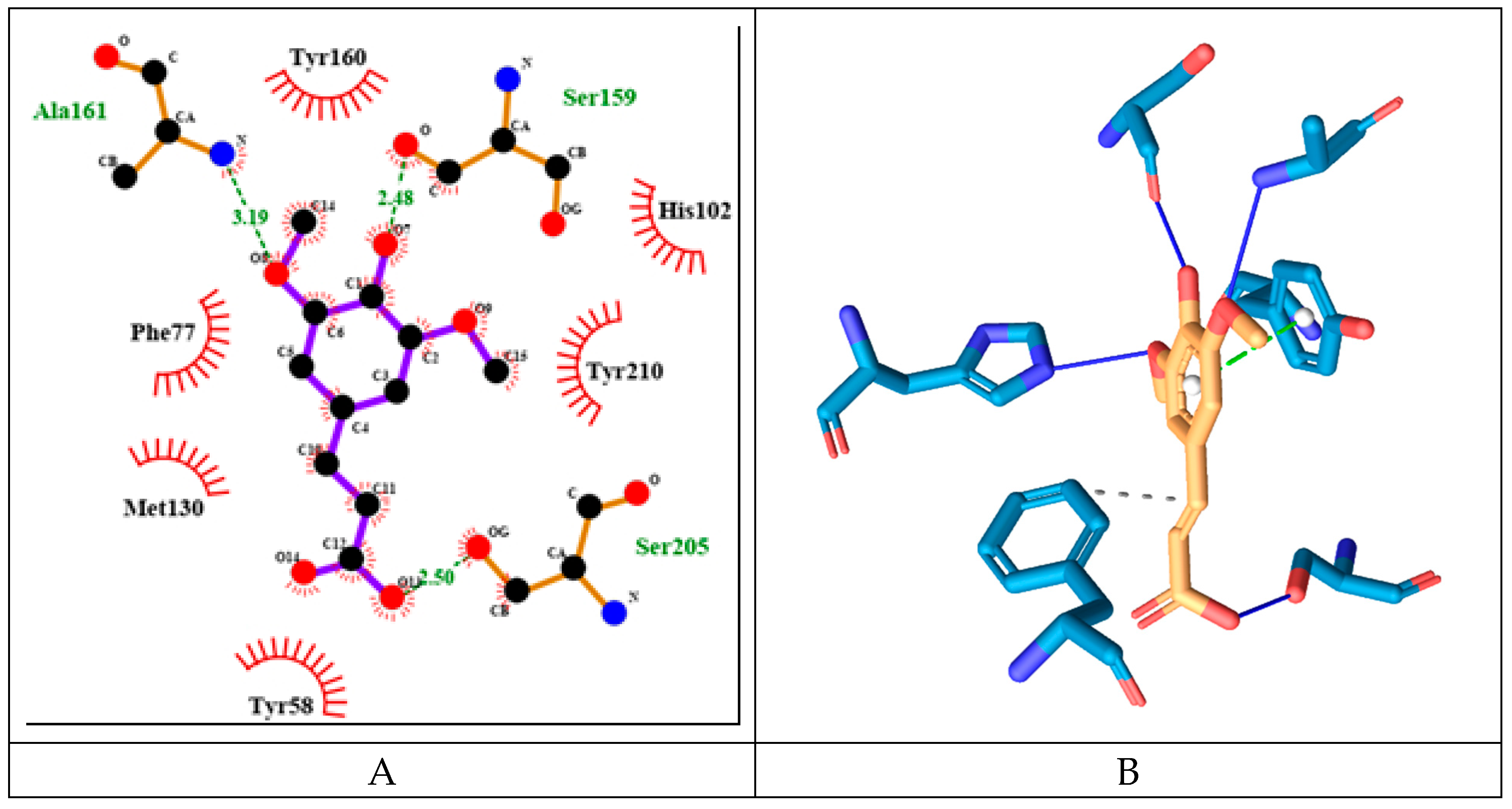

SINA has the lowest binding energy among the tested substances of -5.76 kcal/mol. It forms more hydrogen bonds with amino acids but only from α-protein chain namely: His102, Ser159, Ala161 and Ser205 (see

Figure 12). It has fewest hydrophobic interactions with amino acids only from γ protein chain: Phe77. And unlike the previous compounds it interacts through π-stacking with Tyr210α.

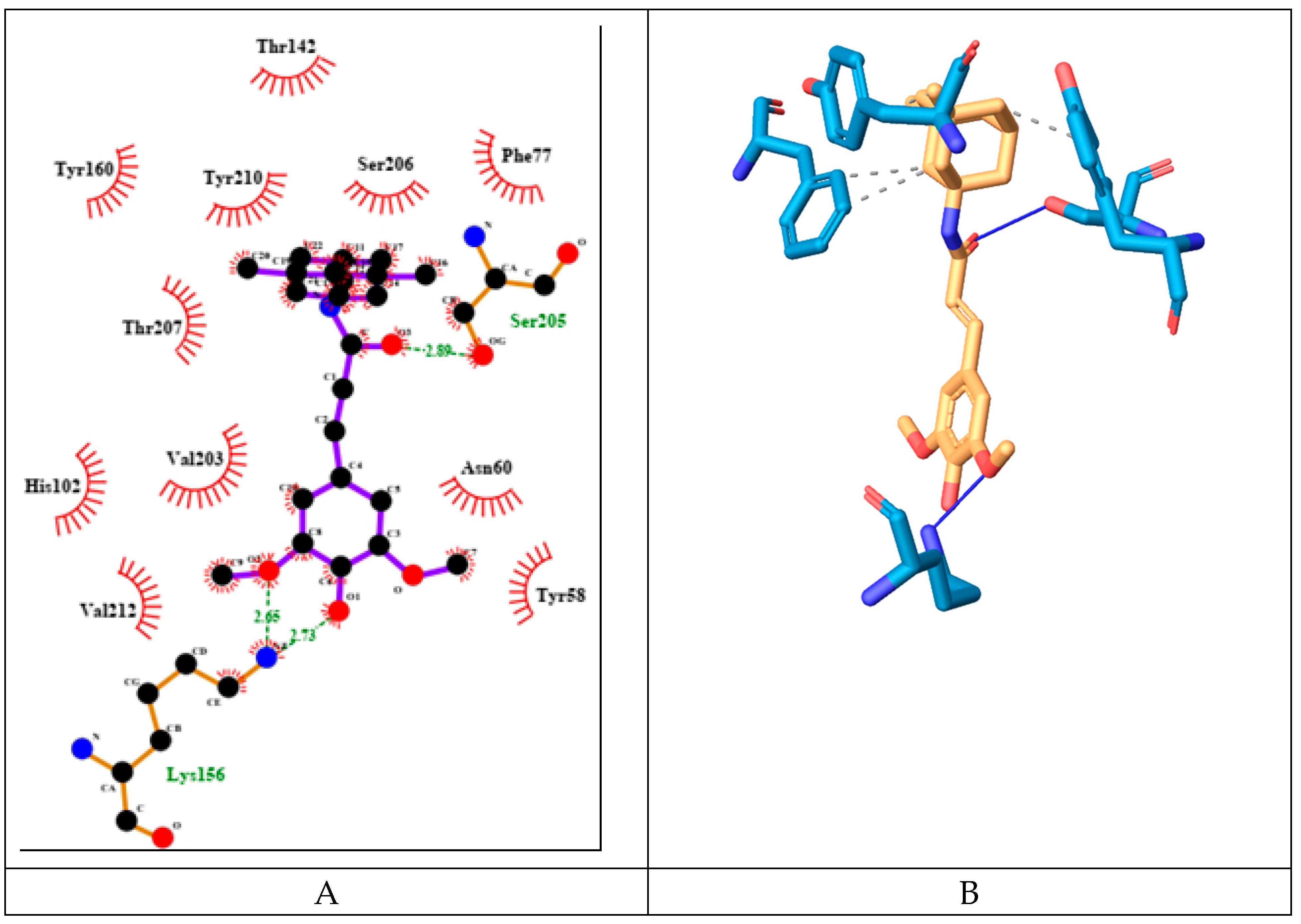

The derivative SINA-MEM scores second by binding energy after flumazenil with value of -7.5 kcal/mol. It forms three hydrogen bonds with amino acids only from α-protein chain namely: Lys156 and Ser205 (see

Figure 13). It has 4 hydrophobic interactions with amino acids from both protein chains: Phe77γ, Tyr160α and Tyr210α.

All of the tested compounds form hydrogen bonds with one of the polar serine residues at α-chain (Ser205 or Ser206). And all of them have hydrophobic interaction with Phe77γ, which is an important amino acid residue in the benzodiazepine binding pocket [Zhu, et al., 2018]. Among them SINA is the compound with the weakest inhibitory potential, while the rest have estimated inhibitory constants Ki in the range 2.9 - 4.0 (see

Table 6).

The detailed results of the re-docking experiments generated similar profile of the interaction of the amino-acid residues (see

Figure 14).

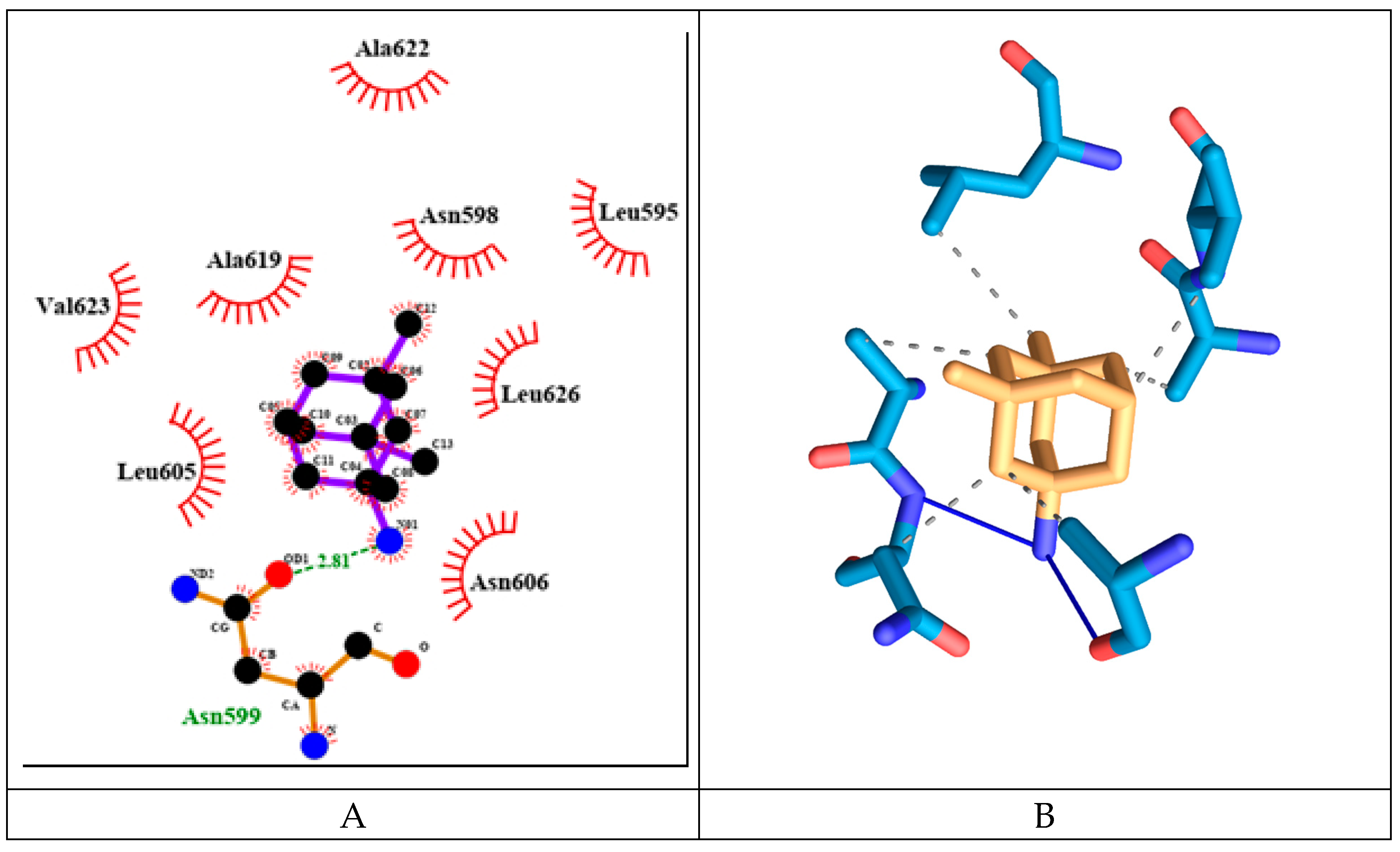

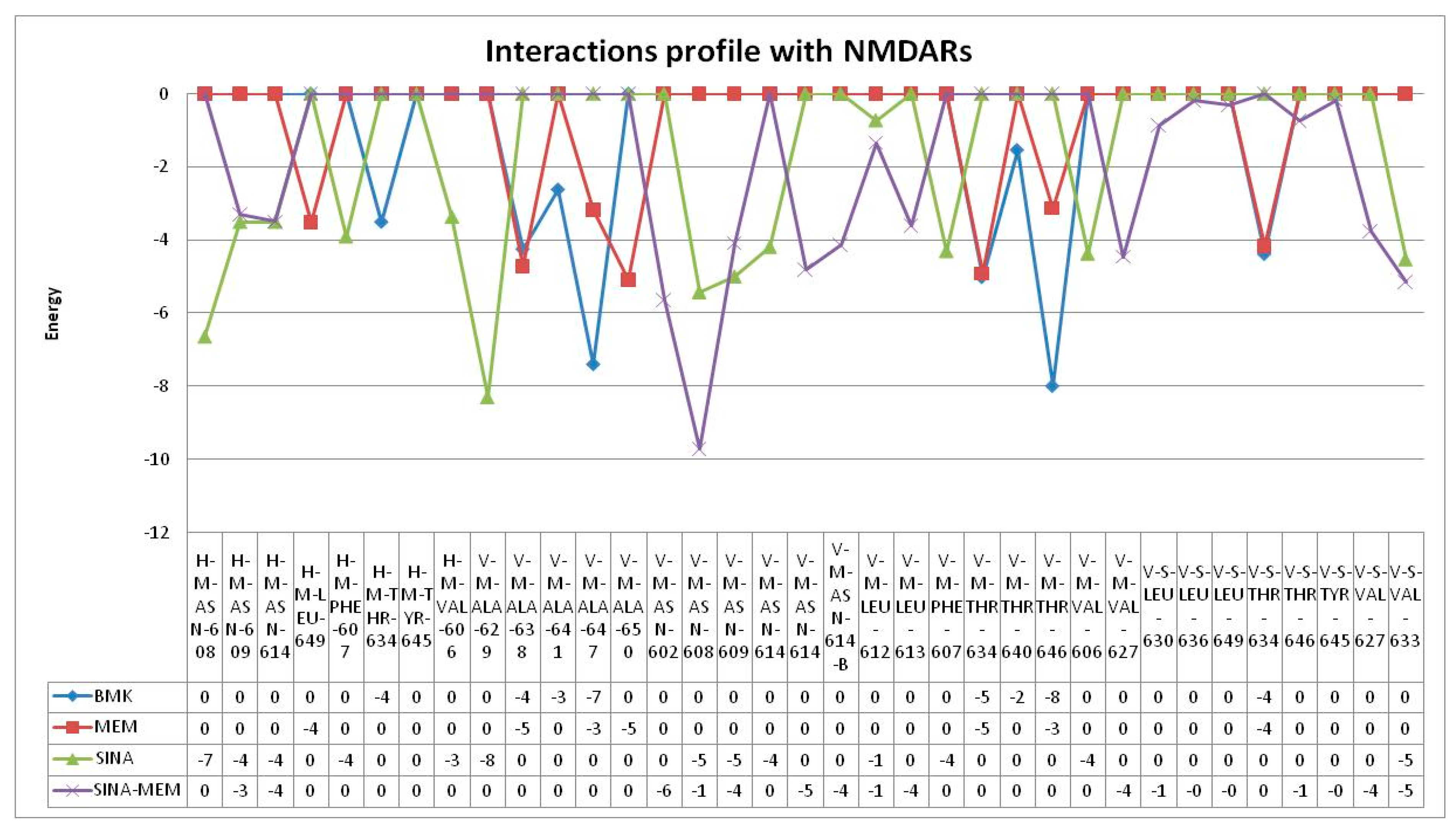

Since MEM is among the very few approved drugs for management of AD as NMDA receptor antagonist and is part of the hybrid molecule, it was decided to be performed docking simulation with the active site of the NMDA receptor.

MEM has relatively weak to moderate binding energy of -6.13 kcal/mol. It forms two hydrogen bonds amino acids from both protein chains namely: Asn599d and Asn606a (see

Figure 15). It has six hydrophobic interactions with amino acids from two protein chains: Asn598d, Asn599d, Ala622d, Val623d, Leu626d and Asn606a.

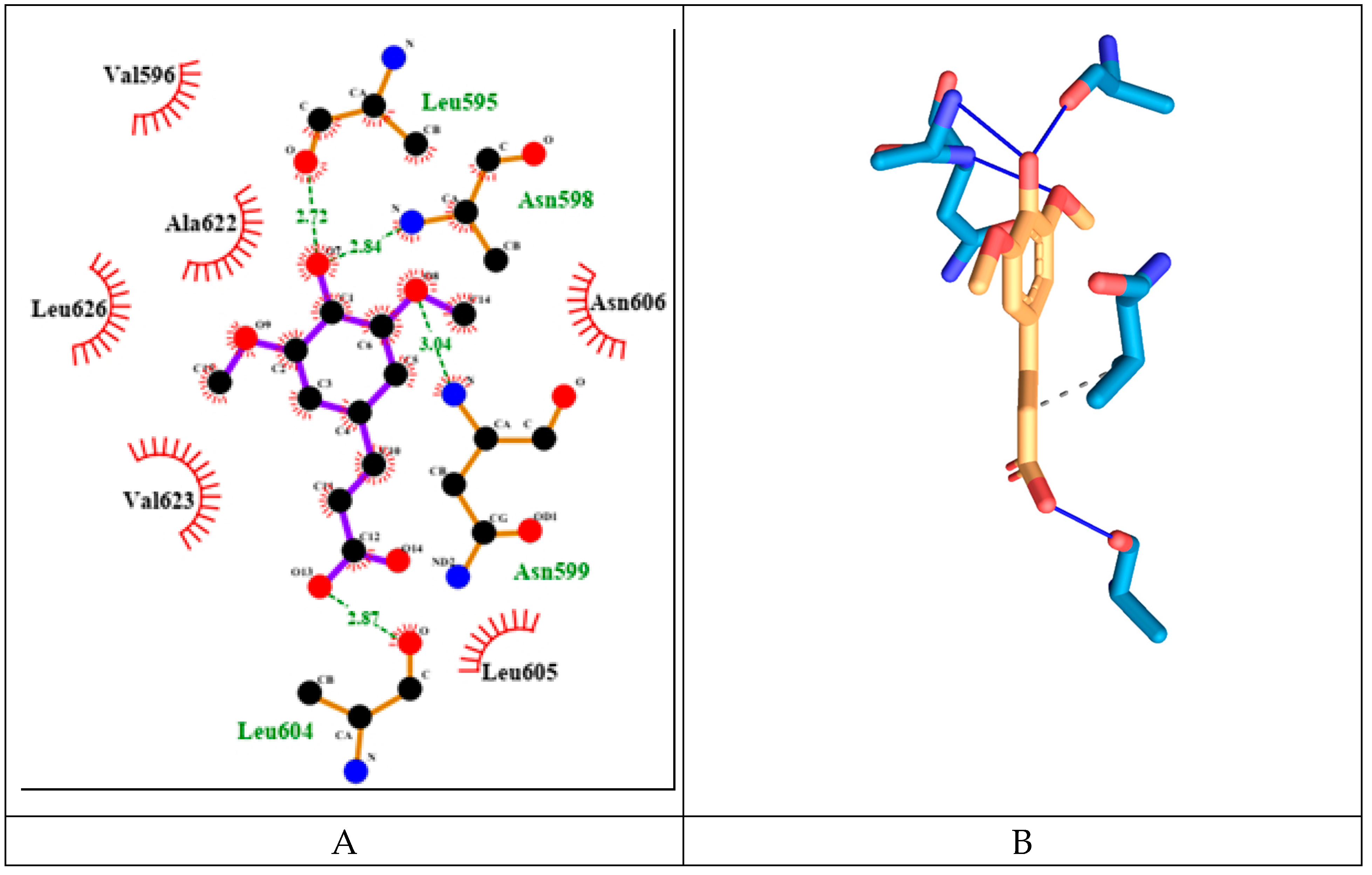

SINA has relatively weak binding energy of -4.59 kcal/mol. It forms four hydrogen bonds amino acids from both protein chains namely: Leu595d, Asn598d, Asn599d and Leu604a (see

Figure 16). It has only one hydrophobic interaction with amino acids from protein chain d: Val623d.

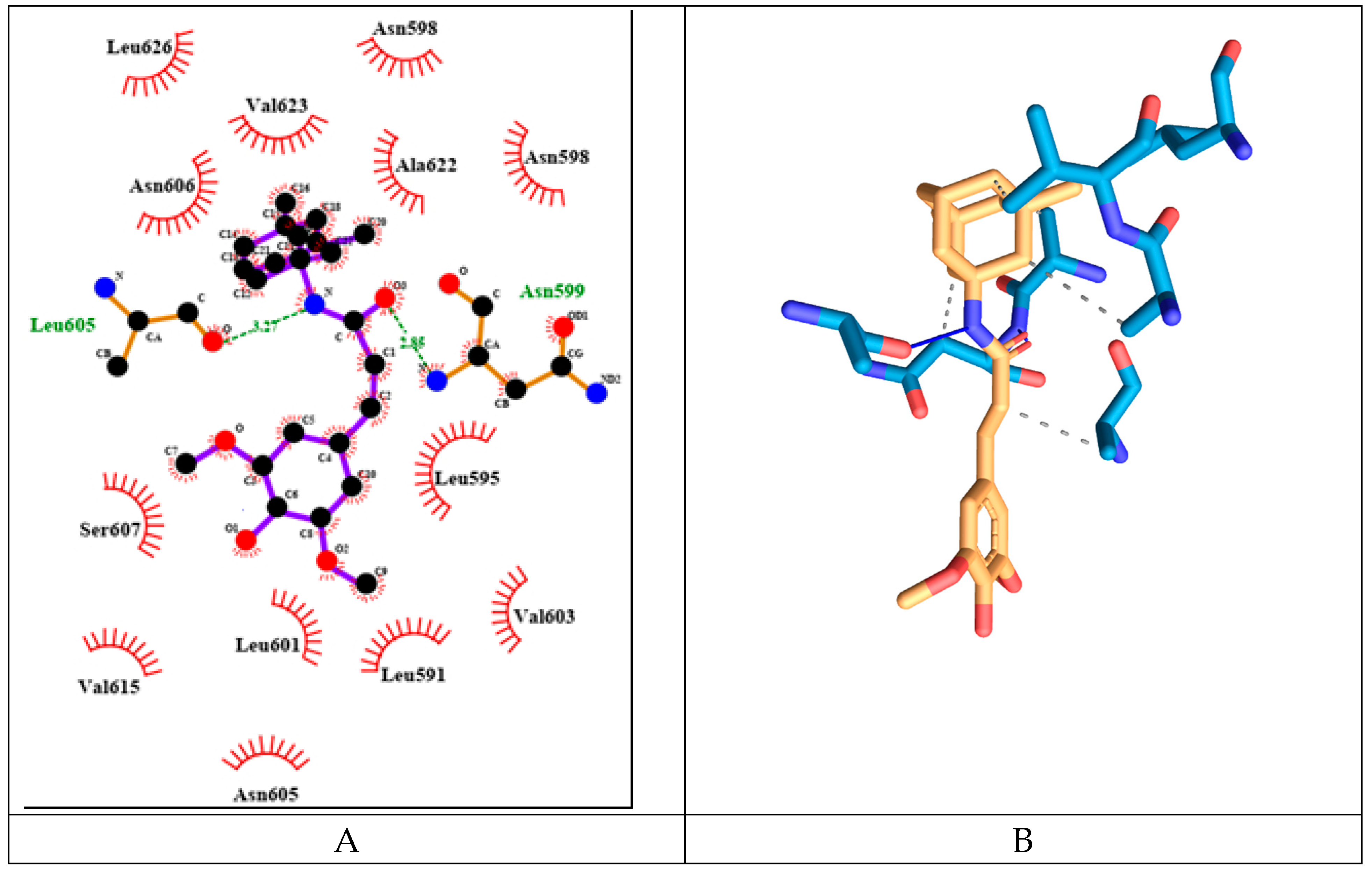

The memantine hybrid molecule has the lowest binding energy among the tested compounds with value -8.91 kcal/mol. It forms two hydrogen bonds amino acids from both protein chains namely: Asn599d and Leu605a (see

Figure 17). It has six hydrophobic interactions with amino acids from one protein chain: Leu595d, Asn598d, Asn599d, Ala622d, Val623d, Leu626d.

It seems that MEM and SINA-MEM rely more on the hydrophobic interactions for binding to the ion channel protein chains and they share most of the amino acid residues they interact with. While the SINA relies more on forming hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acid residues. All of the compounds form hydrogen bonds with the important for the ion channel blockage Asn residues or/and they have hydrophobic interactions with them (Asn598d, Asn599d, Asn606a).

The detailed results of the re-docking experiments generated similar profile of the interaction of the amino-acid residues (see

Figure 18).

Sinapic acid is the weakest ion channel inhibitor with highest binding energy (-4.59 kcal/mol) and estimated inhibitory constant (428.54 µM). While the hybrid molecule SINA-MEM is the most potent inhibitor with lowest binding energy (-8.91 kcal/mol) and estimated inhibitory constant (294.18 nM) (see

Table 7).

It is noteworthy to mention that both MEM and SINA-MEM show preference for binding at the ion channel opening vicinity, while the SINA shows no such trend.