2 study groups of 20 patients with Eaton stage 1-2 trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis diagnosed by x-ray and visit to the hand surgeon were taken into consideration.

10 patients were treated with manual therapy, pumps, massage and functional and proprioceptive exercises explained verbally.

10 patients were treated with manual therapy, pumps, massage and functional and proprioceptive exercises using a specific App.

Both groups were treated with 1 session per week for 3 weeks, 1 session every 15 days for 3 times and the last one at 3 weeks for a total of 7 sessions in 3 months including follow ups at 5 and 12 weeks.

Both groups underwent: functional assessment, functional neoprene brace for activities of daily living, education, manual therapy and exercises.

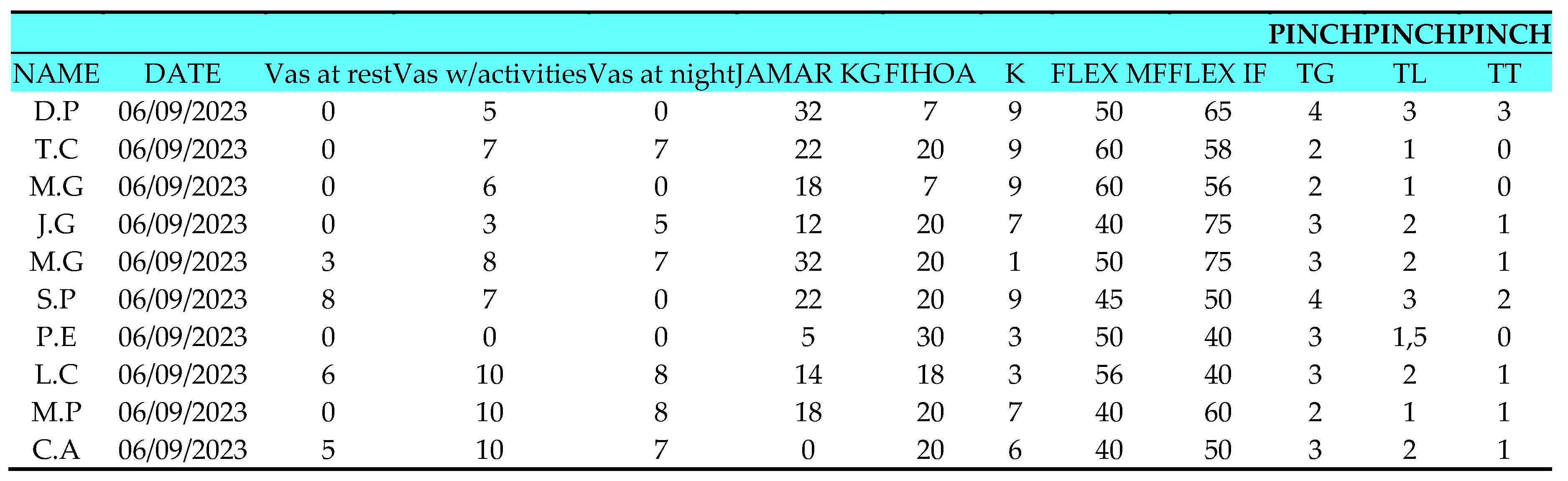

GROUP 0

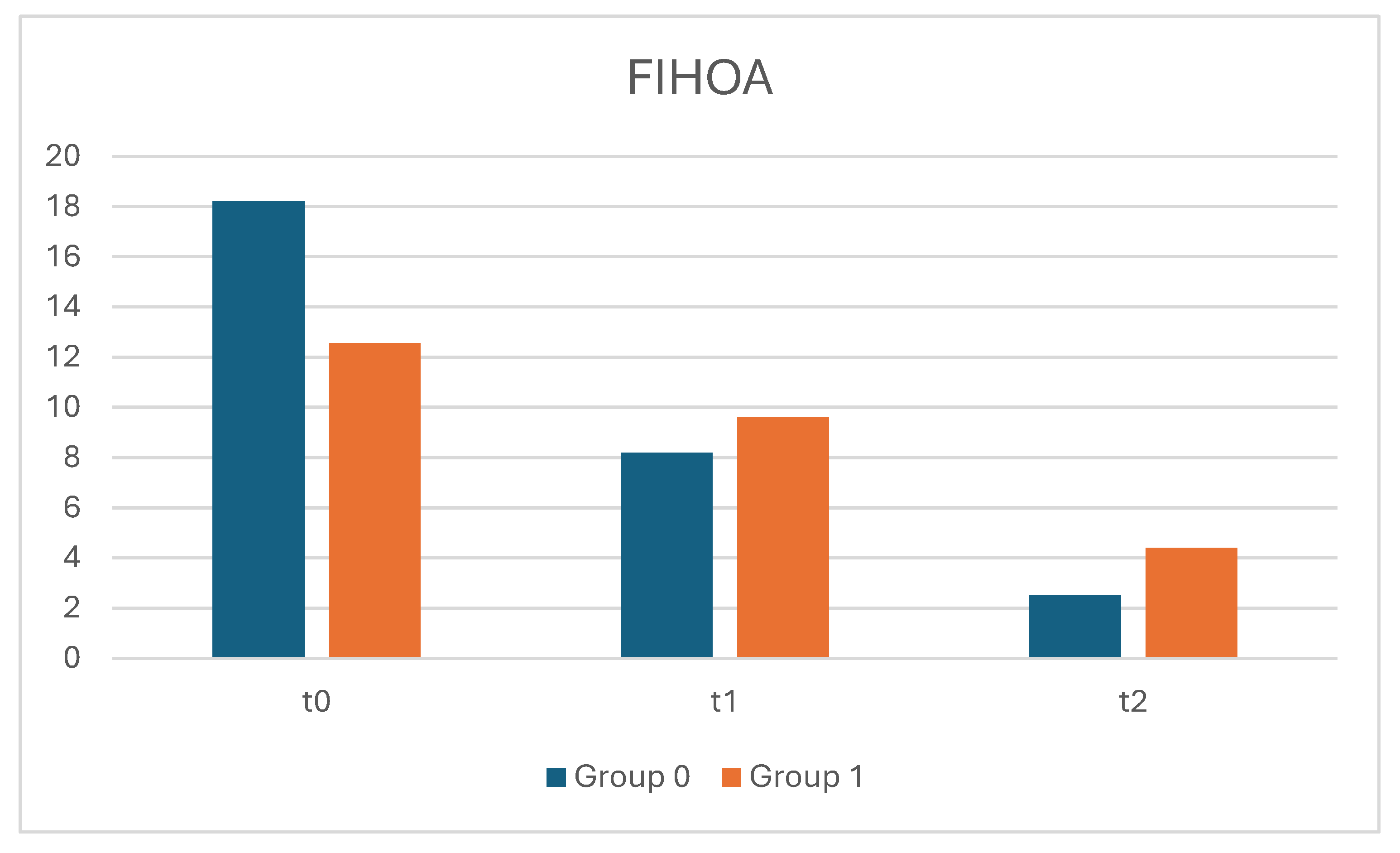

The control group (T0) consists of 10 patients (3 male and 7 female) with an average age of 68 (ranging from 52 to 82 years). The affected hand is the right hand for all patients, and 6 out of 10 do not report pain at rest. During Activities of Daily Living (ADL), 9 patients report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale ranging from 5 to 10, with 3 patients at a level of 10 and only 1 at a level of 0. Nighttime pain is reported by 6 patients, ranging from 5 to 8, while 4 patients do not experience pain. On the FIHOA scale (where a score of 0 means no movement difficulty, 1 means slight difficulty, 2 means significant difficulty, and 3 means impossible), the average score is 18.2, with scores ranging from 7 to a maximum of 30. Thumb opposition, measured using the K scale (where K10 is the maximum score), shows that only 1 patient had a score of K1, and 4 out of 10 patients scored K9. The remaining patients had scores ranging from K3 to K7. Active range of motion (ROM) for thumb flexion (measured with a finger goniometer) ranges from 40 to 60 degrees for the metacarpophalangeal joint, and from 40 to 75 degrees for the interphalangeal joint. Grip strength, measured in kilograms with a Jamar dynamometer, shows an average strength of 17.5 kg, ranging from 5 to 22 kg, with only 1 patient at 0 kg. Pinch Test results show that the average strength for the tip-to-tip pinch is 2.9 kg (ranging from 2 to 4 kg), for the lateral pinch it is 1.85 kg (ranging from 1 to 3 kg), and for the three-jaw chuck pinch it is 0.85 kg (ranging from 0 to 2 kg).

The control group (T1) consists of 10 patients (3 male and 7 female) with an average age of 68 (ranging from 52 to 82 years). The affected hand is the right hand for all patients except 2, who do not report pain at rest. During ADL, 5 patients report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale ranging from 5 to 8, while the other 5 report no pain. Nighttime pain is reported by 2 patients at levels 5 and 6 on the Vas scale, while 8 patients do not experience nighttime pain. On the FIHOA scale, the average score is 8.2, ranging from 3 to 17. Thumb opposition, measured using the K scale, ranges from K7 to K10. Active range of motion shows that thumb flexion ranges from 50 to 72 degrees for the metacarpophalangeal joint and from 45 to 82 degrees for the interphalangeal joint. Grip strength, measured with a Jamar dynamometer, shows an average strength of 20.1 kg, ranging from 5 to 35 kg. Pinch Test results show that the average strength for the tip-to-tip pinch is 3.3 kg (ranging from 2 to 4 kg), for the lateral pinch it is 2.4 kg (ranging from 1 to 3 kg), and for the three-jaw chuck pinch it is 1.4 kg (ranging from 1 to 2 kg).

The control group (T2) consists of 10 patients (3 male and 7 female) with an average age of 68 (ranging from 52 to 82 years). The affected hand is the right hand for all patients, and none of the patients report pain at rest. During ADL, 3 patients do not experience pain, while the other 7 report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale ranging from 2 to 5. No patients report nighttime pain. On the FIHOA scale, the average score is 2.5, ranging from 0 to 7. Thumb opposition, measured using the K scale, ranges from K9 to K10. Active range of motion shows that thumb flexion ranges from 50 to 75 degrees for the metacarpophalangeal joint and from 47 to 80 degrees for the interphalangeal joint. Grip strength, measured with a Jamar dynamometer, shows an average strength of 25.3 kg, ranging from 7 to 40 kg. Pinch Test results show that the average strength for the tip-to-tip pinch is 4.1 kg (ranging from 3 to 5 kg), for the lateral pinch it is 3 kg (ranging from 1 to 4 kg), and for the three-jaw chuck pinch it is 2.2 kg (ranging from 1 to 3 kg).

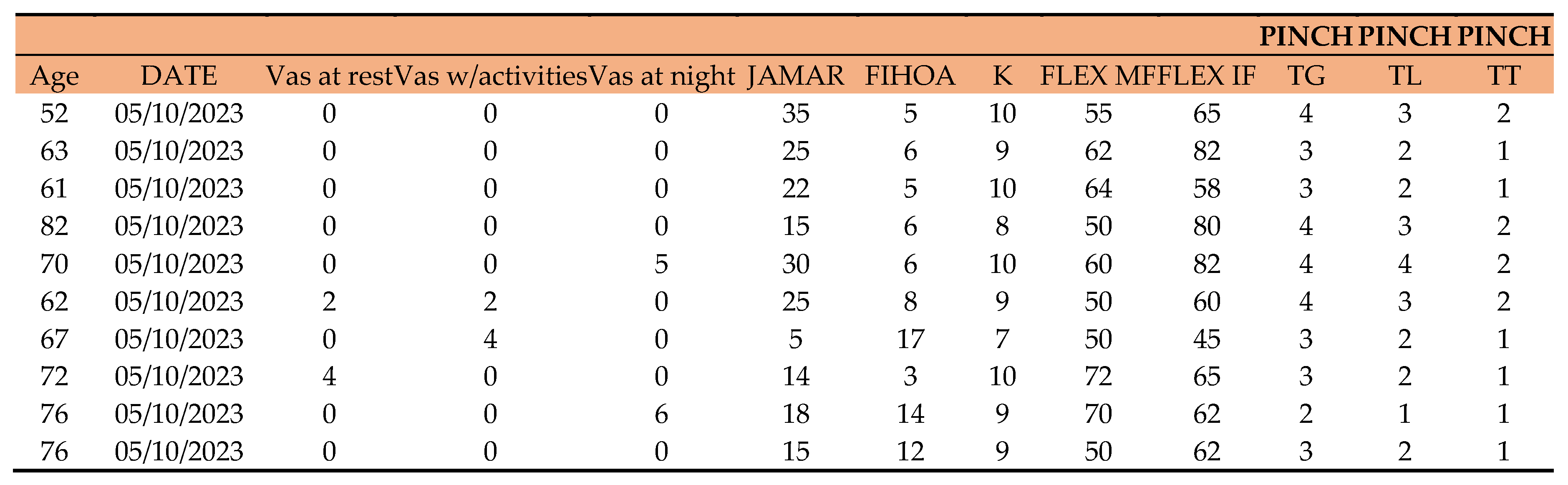

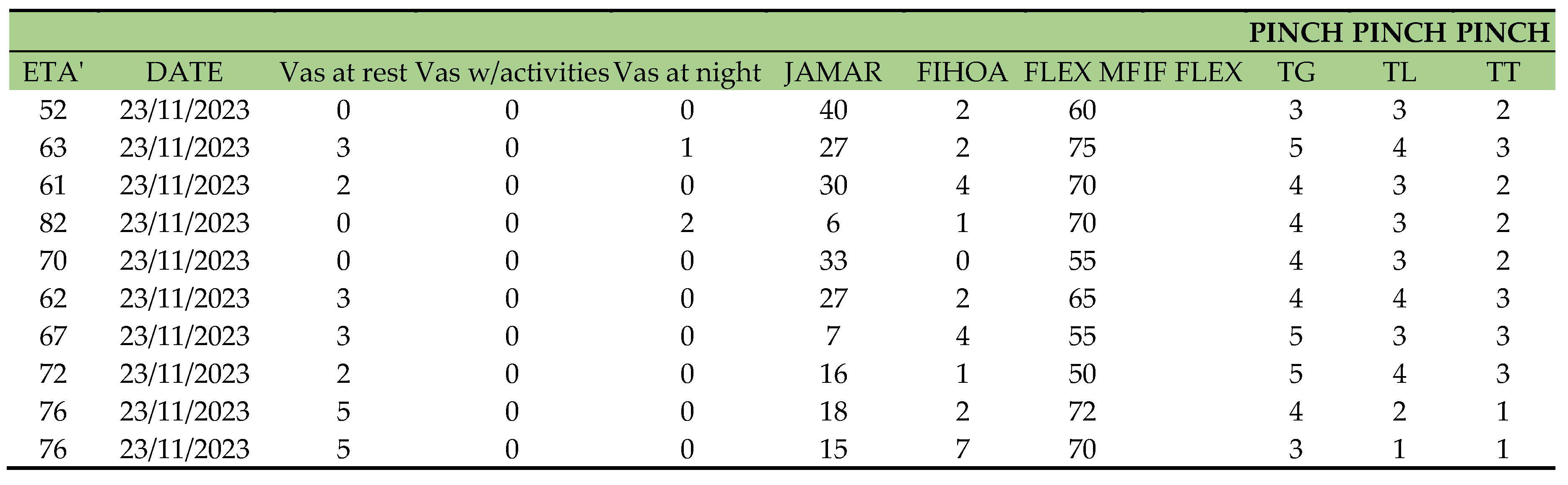

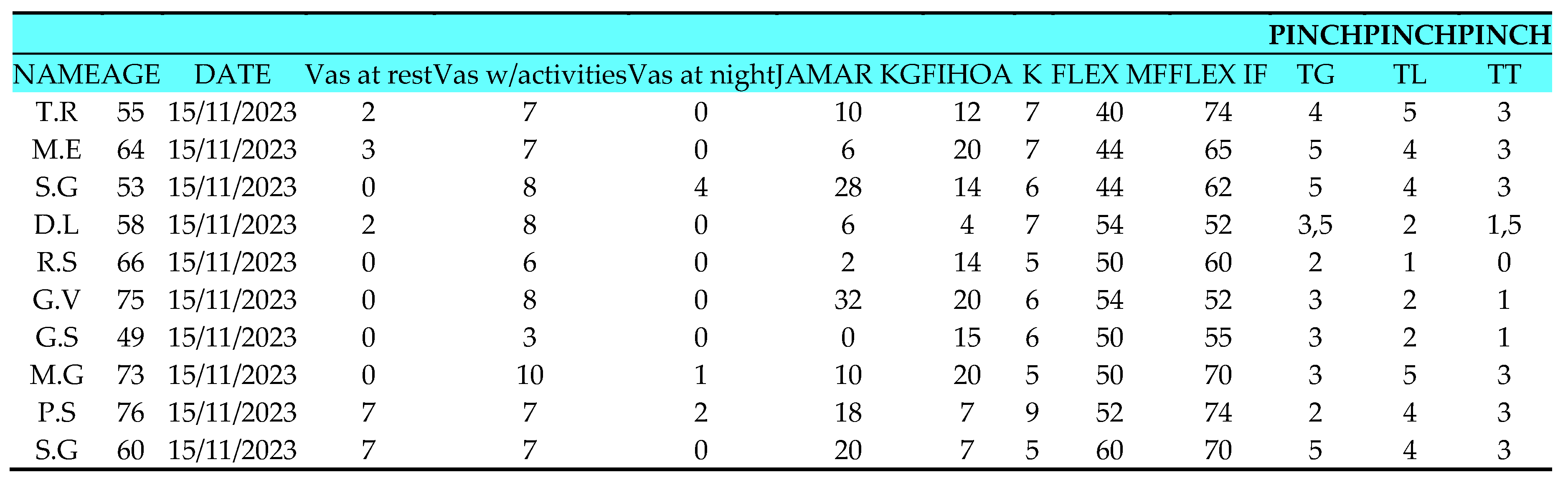

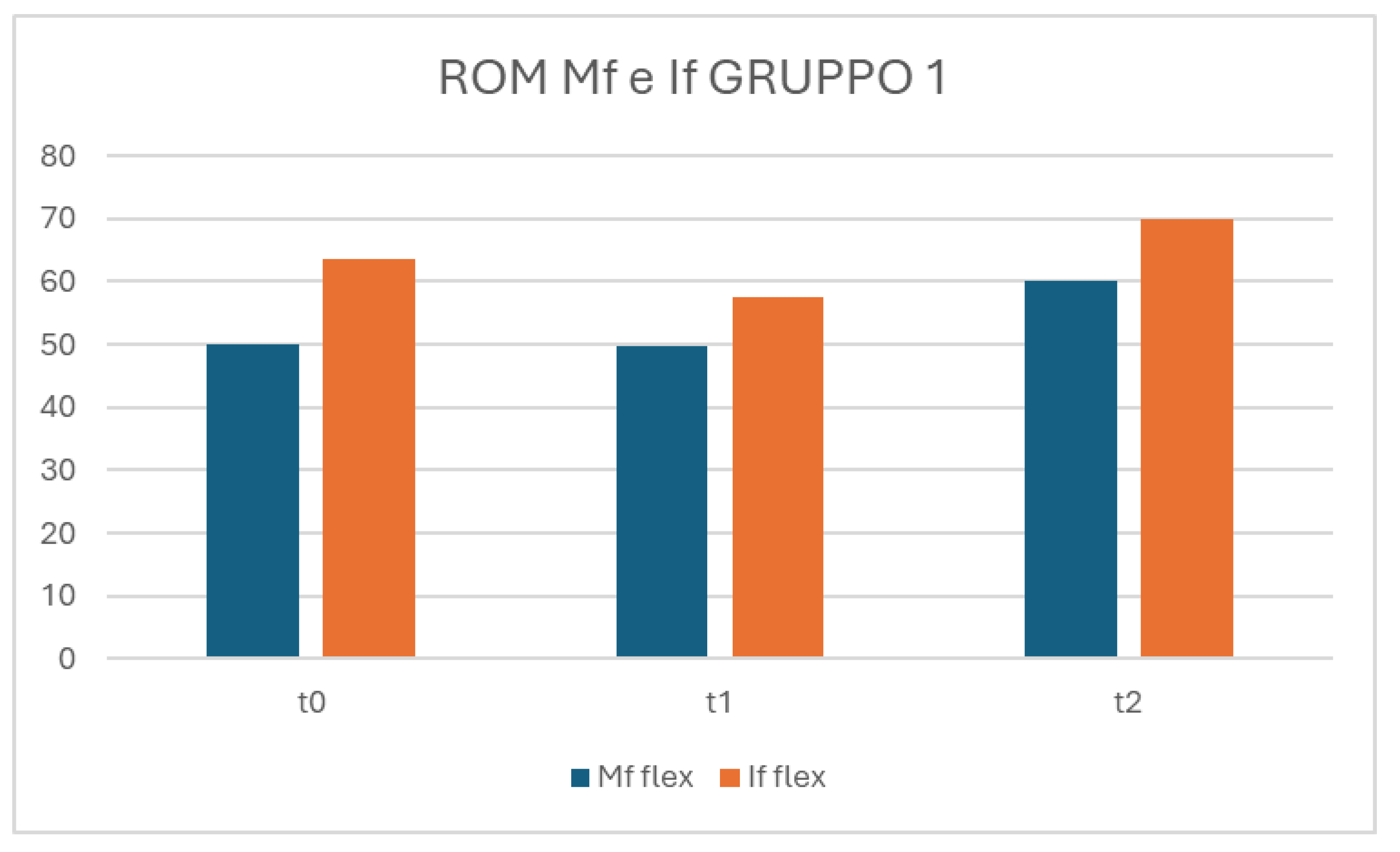

GROUP 1

The control group (T0) consists of 10 patients (2 males and 8 females) with an average age of 63 (ranging from 53 to 76 years). The affected hand is the right hand for 8 patients, with 5 out of 10 not reporting pain at rest. During activities of daily living (ADL), all patients report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale, ranging from 1 to 3, with only 1 patient at 10. Nighttime pain is reported by 3 patients, ranging from 1 to 4, while 7 patients do not experience pain at night. On the FIHOA scale (where a score of 0 means movement possible without difficulty, 1 possible with slight difficulty, 2 possible with significant difficulty, and 3 impossible), the average score is 13.3, ranging from 4 to 20. In thumb opposition measured on the K scale (where K10 is the maximum), the range is between K5 and K9. In active range of motion (ROM), flexion (measured with a finger goniometer) of the metacarpophalangeal (MF) joint ranges from 40 to 60 degrees, while flexion of the interphalangeal (IF) joint ranges from 52 to 74 degrees. Jamar strength in kilograms (Kg): the average grip strength measured with Hand Grip is 13.2 kg, ranging from 2 to 32 kg, with only 1 patient at 0. Pinch Test results: Tip Grip (TG) strength has an average of 3.5 kg, ranging from 2 to 5 kg; lateral pinch strength (TL) has an average of 3.3 kg, varying between 1 and 6 kg; terminal pinch strength (TT) has an average of 2.15 kg, varying between 0 and 5 kg.

The control group (T1) consists of 10 patients (2 males and 8 females) with an average age of 63 (ranging from 53 to 76 years). The affected hand is the right hand for 8 patients. Resting pain is reported by only 3 patients at 2 on the Vas scale. During ADL, 9 patients report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale, ranging from 2 to 8. Nighttime pain is reported by 2 patients at 4 and 2 on the Vas scale. On the FIHOA scale, the average score is 9.6, ranging from 3 to 15. In thumb opposition measured on the K scale, the range is between K6 and K10, with 2 patients reaching K10. In active ROM, flexion of the MF joint ranges from 50 to 60 degrees, while flexion of the IF joint ranges from 52 to 74 degrees. Jamar strength in kilograms: the average grip strength measured with Hand Grip is 14.6 kg, ranging from 2 to 35 kg. Pinch Test results: TG strength has an average of 3.9 kg, ranging from 2 to 5 kg; TL strength has an average of 2.4 kg, ranging between 1 and 6 kg; TT strength has an average of 1.4 kg, ranging between 0 and 5 kg.

The control group (T1) consists of 10 patients (2 males and 8 females) with an average age of 63 (ranging from 53 to 76 years). The affected hand is the right hand for 8 patients. Resting pain is reported by only 1 patient, during ADL 8 patients report varying levels of pain on the Vas scale, ranging from 2 to 4, with two patients at 0 on the Vas scale. Nighttime pain is not reported. On the FIHOA scale, the average score is 4.4, ranging from 1 to 10, with only 1 patient at 0. In thumb opposition measured on the K scale, the range is between K7 and K10, with 5 patients reaching K10. In active ROM, flexion of the MF joint ranges from 55 to 70 degrees, while flexion of the IF joint ranges from 60 to 80 degrees. Jamar strength in kilograms: the average grip strength measured with Hand Grip is 16.2 kg, ranging from 4 to 40 kg. Pinch Test results: TG strength has an average of 4.6 kg, ranging from 2 to 6 kg; TL strength has an average of 4.4 kg, ranging between 2 and 6 kg; TT strength has an average of 3.3 kg, ranging between 1 and 5 kg.

Table 7.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA FIHOA, FIHOAt1, FIHOAt2.

Table 7.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA FIHOA, FIHOAt1, FIHOAt2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

4973.2 |

1 |

779.49 |

17 |

108.4622 |

8.509e-09*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

4.4 |

1 |

779.49 |

17 |

0.0969 |

0.7593256 |

| Time |

1319.7 |

2 |

344.44 |

34 |

65.1351 |

2.348e-12 *** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

184.1 |

2 |

344.44 |

34 |

9.0842 |

0.0006906 *** |

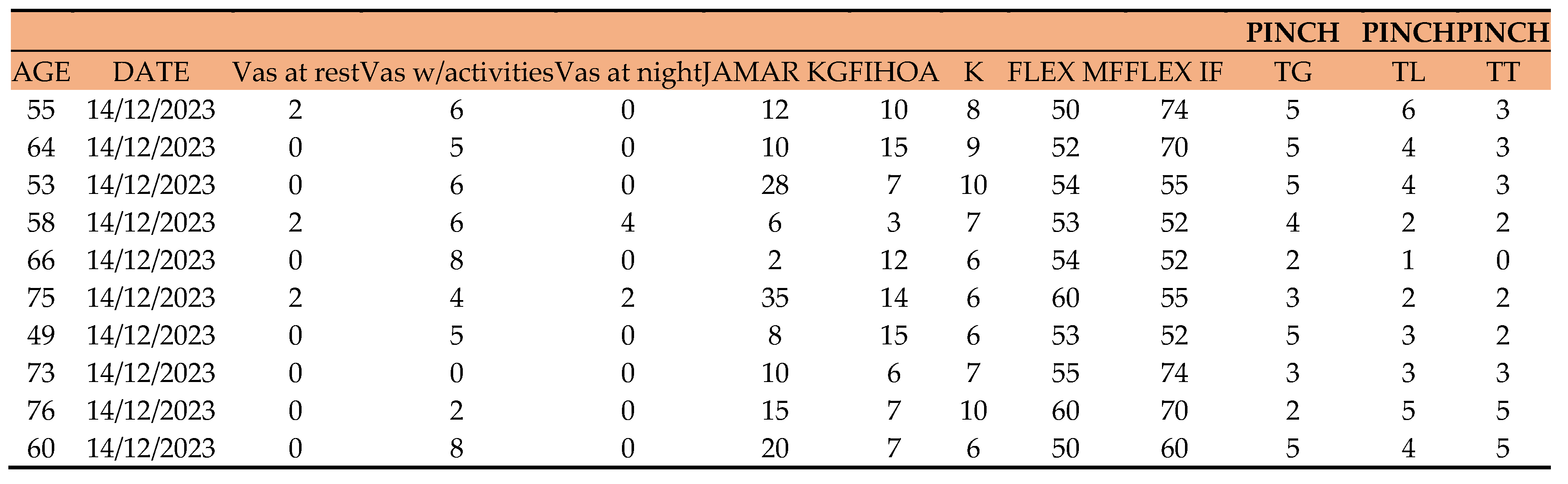

The FIHOA model shows that factor 1 of the group does not have a significant effect on the outcome. The FIHOAt1 and FIHOAt2 models, which include time as a variable, show a significant effect of time on the outcome. In particular, the FIHOAt2 model also shows a significant effect of the interaction between factor 1 of the group and time on the outcome. This suggests that factor 1 of the group has a time-dependent effect on the outcome.

Table 8.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA FLEX.IF, FLEX.IFt1, FLEX.IFt2.

Table 8.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA FLEX.IF, FLEX.IFt1, FLEX.IFt2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

247298 |

1 |

3913.7 |

18 |

1137.3915 |

< 2.2e-16 *** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

49 |

1 |

3913.7 |

18 |

0.2235 |

0.6420497 |

| Time |

737 |

2 |

1478.3 |

36 |

8.9748 |

0.0006881 *** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

338 |

2 |

1478.3 |

36 |

4.1142 |

0.0245931 * |

The ANOVA analysis shows that both Intercept and Time are statistically significant, with p values <0.001. However, Factor 1 - Group is not statistically significant, with a p value of 0.642. Additionally, the interaction between Factor 1 - Group and Time is statistically significant, with a p value of 0.0245. This suggests that Time has a significant effect on the outcome of the variables FLEX.IF...9, FLEX.IF...22, FLEX.IFt2, while the Factor Group does not have a significant effect. However, there is a significant interaction between Factor Group and Time, which may indicate that the effect of Time on the variables depends on the Group to which the observation belongs.

Table 9.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA JAMAR.KG, JAMAR.KGt1, JAMAR.KGt2.

Table 9.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA JAMAR.KG, JAMAR.KGt1, JAMAR.KGt2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

19046.0 |

1 |

4966.3 |

18 |

69.0309 |

0.0000001424 *** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

595.3 |

1 |

4966.3 |

18 |

2.1578 |

0.15911 |

| Time |

298.1 |

2 |

1070.8 |

36 |

5.0116 |

0.01202 * |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

62.4 |

2 |

1070.8 |

36 |

1.0489 |

0.36077 |

The factor 1, namely "Group", does not have a significant effect on the model, with an F value of 2.1578 and a p-value of 0.15911.

Time has a significant effect on the model, with an F value of 5.0116 and a p-value of 0.01202.

The interaction between "Group" and time does not have a significant effect on the model, with an F value of 1.0489 and a p-value of 0.36077. In summary, the intercept and time are significant factors in the model, while "Group" and the interaction between "Group" and time do not have a significant effect on the outcome.

Table 10.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA K, K.t1, K.t2.

Table 10.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA K, K.t1, K.t2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

3840.0 |

1 |

67.067 |

18 |

1030.6163 |

<2.2e-16*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

9.6 |

1 |

67.067 |

18 |

2.5765 |

0.1259 |

| Time |

98.8 |

2 |

76.133 |

36 |

23.3590 |

0.0000003138*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

6.4 |

2 |

76.133 |

36 |

1.5131 |

0.2339 |

Factor 1 - Group has a value of 9.6 with a Df of 1 and an SS den of 67.067. The F test has a value of 2.5765 with a Pr (>F) of 0.1259, which does not reach a level of statistical significance (). The factor "Time" has a value of 98.8 with a Df of 2 and an SS den of 76.133. The F test has a value of 23.3590 with a very low Pr (>F), indicating a very high statistical significance (**). Factor 1 - Group:Time has a value of 6.4 with a Df of 2 and an SS den of 76.133. The F test has a value of 1.5131 with a Pr (>F) of 0.2339, indicating that there is no statistical significance.

In conclusion, the "Intercept" factor and the "Time" factor are both statistically significant, while the factor 1 - Group is not. The factor 1 - Group:Time is not statistically significant.

Table 11.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TG, TGt1, TGT2 .

Table 11.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TG, TGt1, TGT2 .

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

832.54 |

1 |

43.775 |

18 |

342.3341 |

3.676e-13*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

5.10 |

1 |

73.775 |

18 |

2.0988 |

0.1646 |

| Time |

13.12 |

2 |

13.650 |

36 |

17.3077 |

5.411e-06*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

0.06 |

2 |

13.650 |

36 |

0.0769 |

0.9261 |

In particular, time seems to have a significant effect on the data, while the Group factor does not seem to have a significant impact. There is no significant interaction between the Group factor and Time. Overall, these conclusions suggest that time is an important factor influencing the data, while the Group factor and the interaction between Group and Time do not have a significant effect.

Table 12.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TL, TLt1, TLt2.

Table 12.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TL, TLt1, TLt2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

561.20 |

1 |

61.175 |

18 |

165.1275 |

1.664e-10*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

24.70 |

1 |

61.175 |

18 |

7.2689 |

0.01477* |

| Time |

13.41 |

2 |

13.150 |

36 |

18.3536 |

3.199e-06*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

0.61 |

2 |

13.150 |

36 |

0.8327 |

0.44308 |

Factor 1 (Group) has a significant effect on the outcome (F=7.2689, p=0.01477), indicating that there is a significant difference between the groups considered in the study. Time has a significant effect on the outcome (F=18.3536, p=3.199e-06), indicating that there are significant variations over time. There is no significant interaction effect between Factor 1 and time (F=0.8327, p=0.44308), suggesting that the effect of the group on the outcome does not vary over time. In summary, we can conclude that there are significant differences between the groups considered in the study and significant variations over time, but the effect of the group on the outcome does not vary over time.

Table 13.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TT, TTt1, TTt2.

Table 13.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA TT, TTt1, TTt2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

268.817 |

1 |

50.283 |

18 |

96.2287 |

0.0000000120*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

24.067 |

1 |

50.283 |

18 |

8.6152 |

0.008846** |

| Time |

15.633 |

2 |

12.467 |

36 |

22.5722 |

0.0000004434*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

0.233 |

2 |

12.467 |

36 |

0.3369 |

0.716208 |

The intercept and Time have a significant effect on the model, while factor 1 (Group) has a significant effect only in TT, TTt1, and TTt2. The interaction between Factor 1 (Group) and Time does not seem to significantly influence the model in any of the three cases.

Table 14.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS WITH ACTIVITIES VAS WITH ACTIVITIES T1, VAS WITH ACTIVITIES T2.

Table 14.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS WITH ACTIVITIES VAS WITH ACTIVITIES T1, VAS WITH ACTIVITIES T2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

1188.15 |

1 |

181.1 |

18 |

118.0933 |

0.000000002448*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

10.42 |

1 |

181.1 |

18 |

1.0353 |

0.3224 |

| Time |

201.70 |

2 |

162.4 |

36 |

22.3559 |

0.000000488176*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

7.23 |

2 |

162.4 |

36 |

0.8017 |

0.4564 |

Time has a significant effect on VAS scores. There are no significant differences between the groups in the effect on VAS scores. There is no significant effect of the interaction between group and time on VAS scores.

Table 15.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS AT REST, VAS AT REST T1, VAS AT REST T2.

Table 15.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS AT REST, VAS AT REST T1, VAS AT REST T2.

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

54.150 |

1 |

62.167 |

18 |

15.6788 |

0.0009188*** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

0.017 |

1 |

62.167 |

18 |

0.0048 |

0.9453834 |

| Time |

45.700 |

2 |

122.733 |

36 |

6.7023 |

0.0033544** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

0.233 |

2 |

122.733 |

36 |

0.0342 |

0.9663898 |

The analysis of variance indicates that time has a significant effect on the outcome (p=0.0033544), while group and the interaction between group and time do not have a significant effect (p=0.9453834 and p=0.9663898 respectively). This suggests that rest has a significant impact on the outcome, while the type of group does not seem to greatly influence the outcome.

Table 16.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS AT NIGHT, VAS AT NIGHT T1, VAS AT NIGHT T2 .

Table 16.

Inter-group data analysis ANOVA VAS AT NIGHT, VAS AT NIGHT T1, VAS AT NIGHT T2 .

| |

Sum |

Sq num |

Df Error |

SS den |

Df F value |

Pr (>F) |

| Intercept |

72.600 |

1 |

90.067 |

18 |

14.5093 |

0.0012851** |

| Factor 1 - Group |

26.667 |

1 |

90.067 |

18 |

5.3294 |

0.0330511* |

| Time |

61.900 |

2 |

114.933 |

36 |

9.6943 |

0.0004284*** |

| Factor 1 – Group:Time |

35.833 |

2 |

114.933 |

36 |

5.6119 |

0.0075602** |

The NIGHT VAS T1 shows a significant difference between groups; the NIGHT VAS T2 shows a significant difference between groups and a significant time effect; the NIGHT VAS shows a significant time effect and a significant interaction between group and time. However, it is important to note that the NIGHT VAS T2 has the lowest p-value, indicating that it may be the most significant.

INTRA-GROUP VARIATION ANALYSIS

To evaluate the differences within the various follow-ups for individual groups, the student t-test was used for normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon test for non-normally distributed variables.

Table 17.

GROUP 0 intra-group variation analysis.

Table 17.

GROUP 0 intra-group variation analysis.

| |

p-value T0-T2 |

p-value T1-T2 |

p-value T0-T1 |

| FIHOA |

0.0000547 |

0.00135 |

0.000159 |

| K |

0.00392 |

0.0886 |

0.0174 |

| TG |

0.013 |

0.528 |

0.0368 |

| TL |

0.00944 |

0.111 |

0.0318 |

| VAS WITH ACTIVITIES |

0.0016 |

0.000256 |

0.0185 |

Table 18.

GROUP 1 intra-group variation analysis.

Table 18.

GROUP 1 intra-group variation analysis.

| |

p-value T0-T2 |

p-value T1-T2 |

p-value T0-T1 |

| FIHOA |

0.0000669 |

0.000473 |

0.0234 |

| K |

0.013 |

0.00911 |

0.000725 |

| TG |

0.00183 |

0.00953 |

0.132 |

| TL |

0.000173 |

0.00105 |

0.726 |

| VAS WITH ACTIVITIES |

0.256 |

0.116 |

0.101 |

In group 0, the variable FIHOA shows significant differences between T0 and T2, T1 and T2, and T0 and T1.

In group 0, the variable K shows significant differences between T0 and T1 and between T1 and T2, but not between T0 and T2.

In group 0, the variables TG and TL show significant differences only between T0 and T1. • In group 0, the variable VAS WITH ACTIVITIES shows significant differences between T0 and T2 and between T1 and T2, but not between T0 and T1.

In group 1, the variable FIHOA shows significant differences between T0 and T2 and between T1 and T2, but not between T0 and T1.

In group 1, the variable K shows significant differences between T0 and T1 and between T0 and T2, but not between T1 and T2.

In group 1, the variable TG shows significant differences between T0 and T2, but not between T1 and T2, and between T0 and T1.

In group 1, the variable TL shows no significant differences between any time periods.

In group 1, the variable VAS WITH ACTIVITIES shows no significant differences between any time periods.

To evaluate Jamar, pinch, and flex mf and if, we will move on to the Wilcoxon test.

Table 19.

GROUP 0 intra-group variation analysis.

Table 19.

GROUP 0 intra-group variation analysis.

| WILCOXON’S TEST |

p-value |

t0-t1 |

t1-t2 |

t0-t2 |

| FLEX IF |

0.0165 |

|

|

0.859 |

| FLEX MF |

0.0142 |

|

|

0.01424 |

| JAMAR |

0.0564 |

0.05639 |

0.0168 |

0.06584 |

| TT |

0.0263 |

0.02627 |

0.01356 |

0.05334 |

| VAS AT NIGHT |

0.0335 |

0.03501 |

0.3711 |

0.03351 |

| VAS AT REST |

0.176 |

0.1756 |

0.3711 |

0.1003 |

Table 20.

GROUP 1 intra-group variation analysis.

Table 20.

GROUP 1 intra-group variation analysis.

| WILCOXON’S TEST |

p-value |

t0-t1 |

t1-t2 |

t0-t2 |

| FLEX IF |

0.292 |

|

|

0.008969 |

| FLEX MF |

0.00583 |

0.005825 |

|

|

| JAMAR |

0.223 |

0.2228 |

0.1346 |

0.1221 |

| TT |

0.0568 |

0.05676 |

0.08897 |

0.01264 |

| VAS AT NIGHT |

0.181 |

1 |

0.3711 |

0.1814 |

| VAS AT REST |

0.0975 |

0.1975 |

0.3458 |

0.09751 |

For the FLEX IF parameter, the two groups show significant differences only at time t0-t2, with a p-value of 0.008969 for Group 1.

For the FLEX MF parameter, the two groups show significant differences only at time t0-t2, with a p-value of 0.00583 for Group 1.

For the JAMAR parameter, the two groups do not show significant differences at any of the considered times.

For the TT parameter, the two groups show significant differences at time t0-t2, with a p-value of 0.01264 for Group 1.

For the VAS AT NIGHT parameter, the two groups do not show significant differences at any of the considered times.

For the VAS AT REST parameter, the two groups do not show significant differences at any of the considered times.

Figure 1.

In the FIHOA, there is an increase in group 0 that decreases at t1 and t2.

Figure 1.

In the FIHOA, there is an increase in group 0 that decreases at t1 and t2.

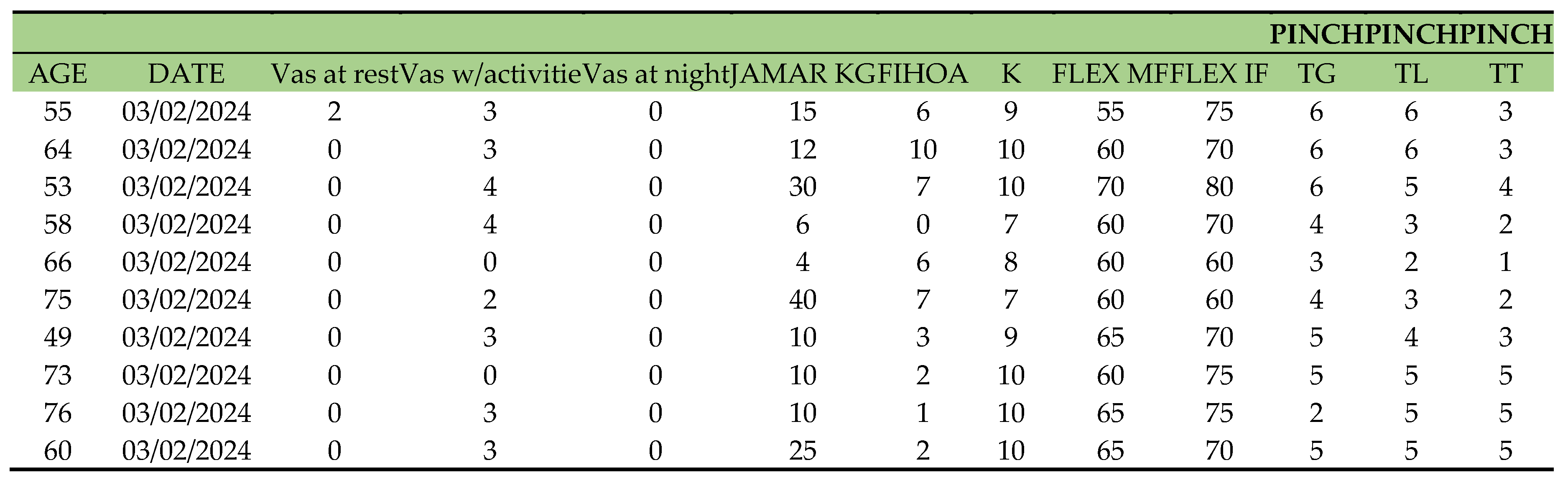

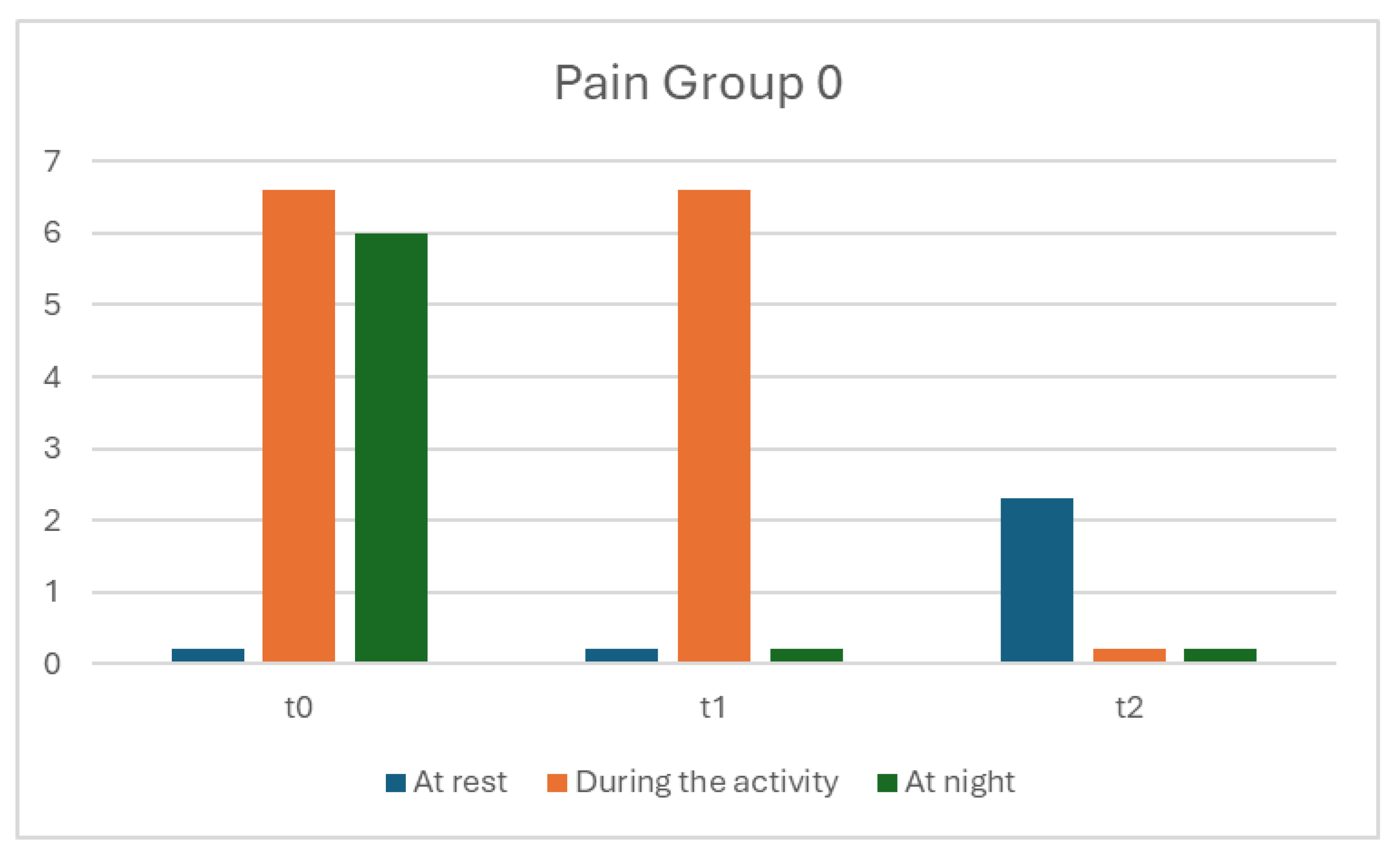

Figure 2.

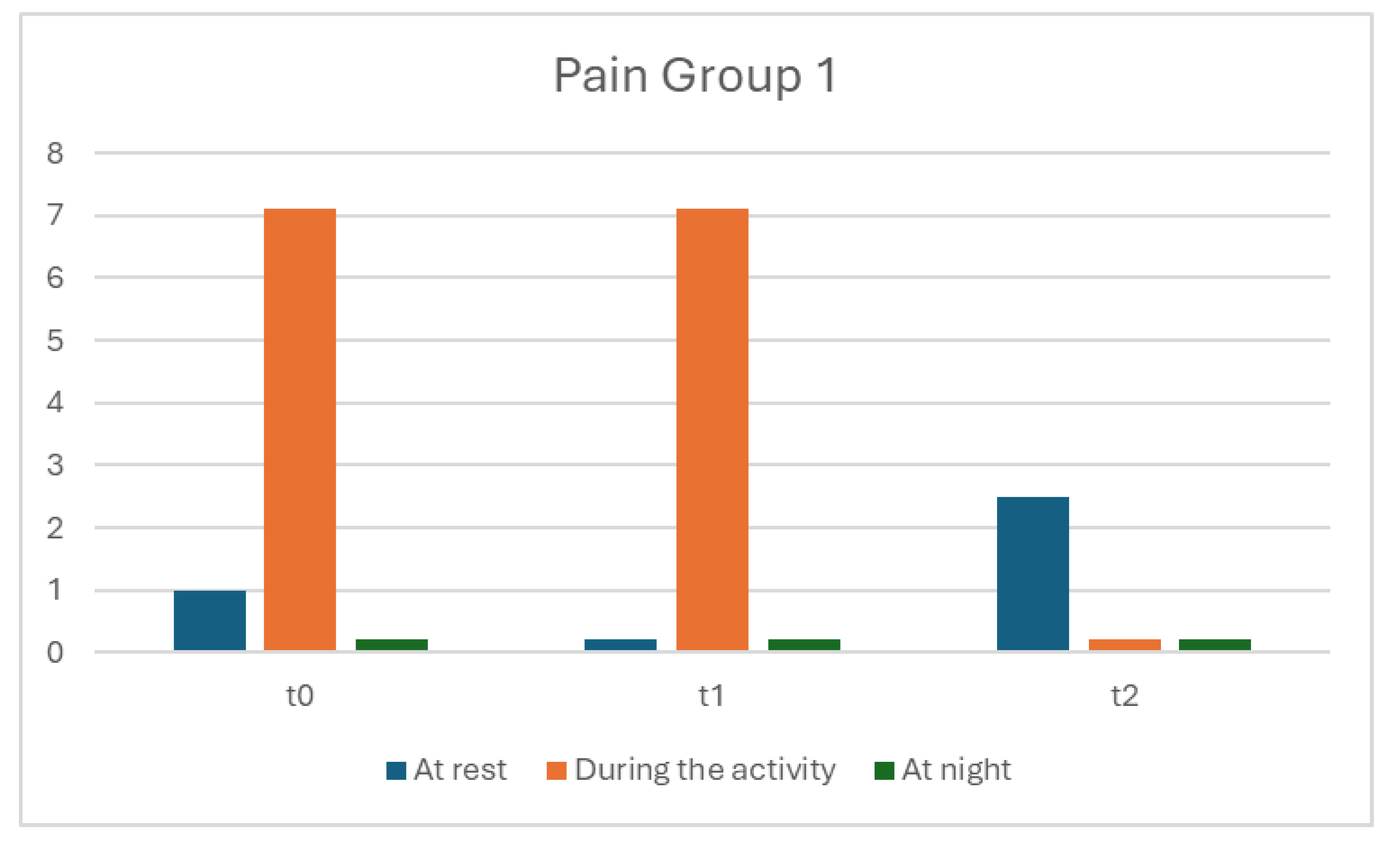

A and B: In the evaluation of pain, we see how both evaluation groups started with high levels of pain during activities, with significant differences compared to the rest and nighttime VAS (group 0 had high levels during the night unlike group 1, while the rest VAS was low). The situation slightly changed at t1 but still showed high VAS levels during activities. By t3, the situation stabilized with significant improvement for both groups.

Figure 2.

A and B: In the evaluation of pain, we see how both evaluation groups started with high levels of pain during activities, with significant differences compared to the rest and nighttime VAS (group 0 had high levels during the night unlike group 1, while the rest VAS was low). The situation slightly changed at t1 but still showed high VAS levels during activities. By t3, the situation stabilized with significant improvement for both groups.

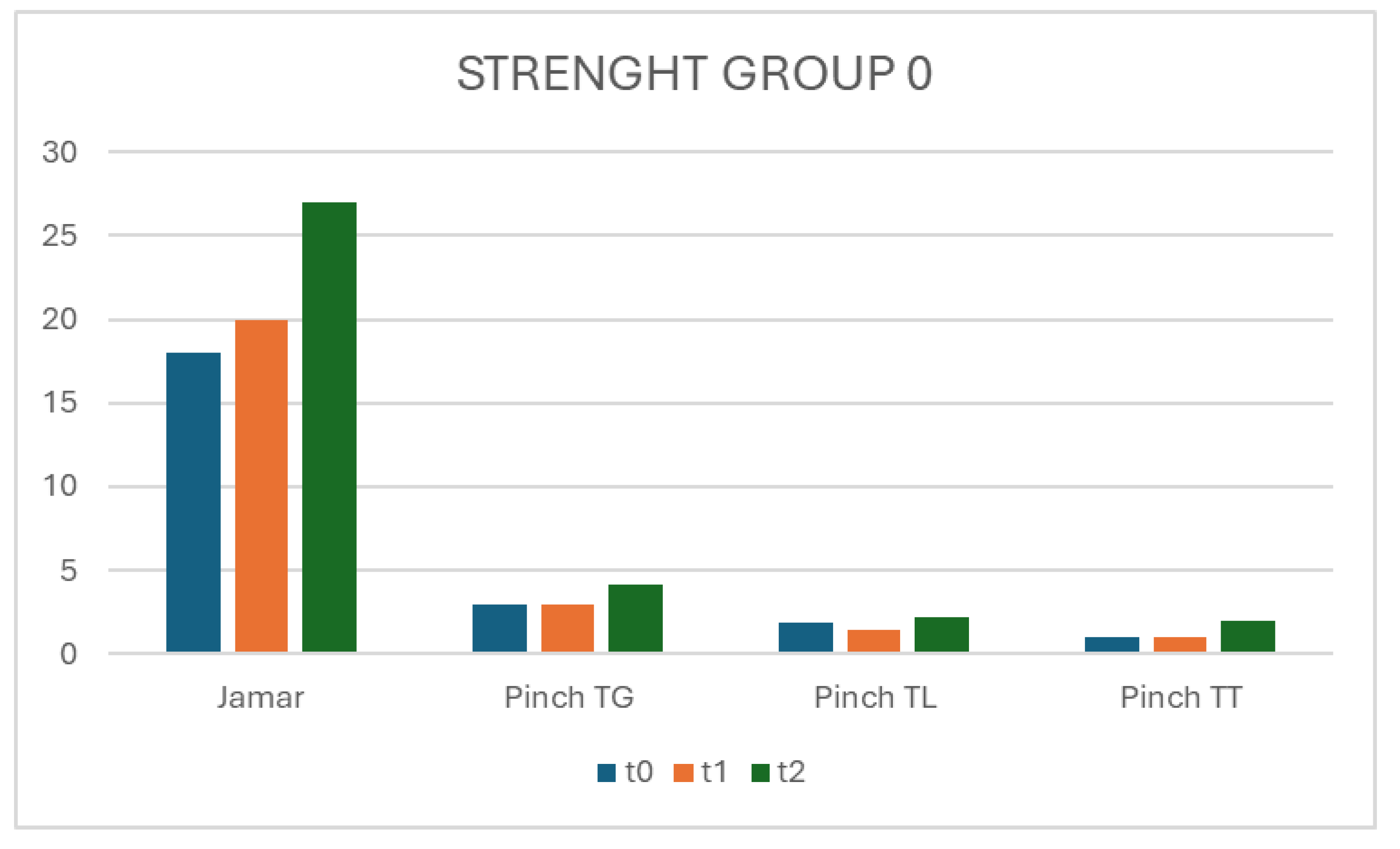

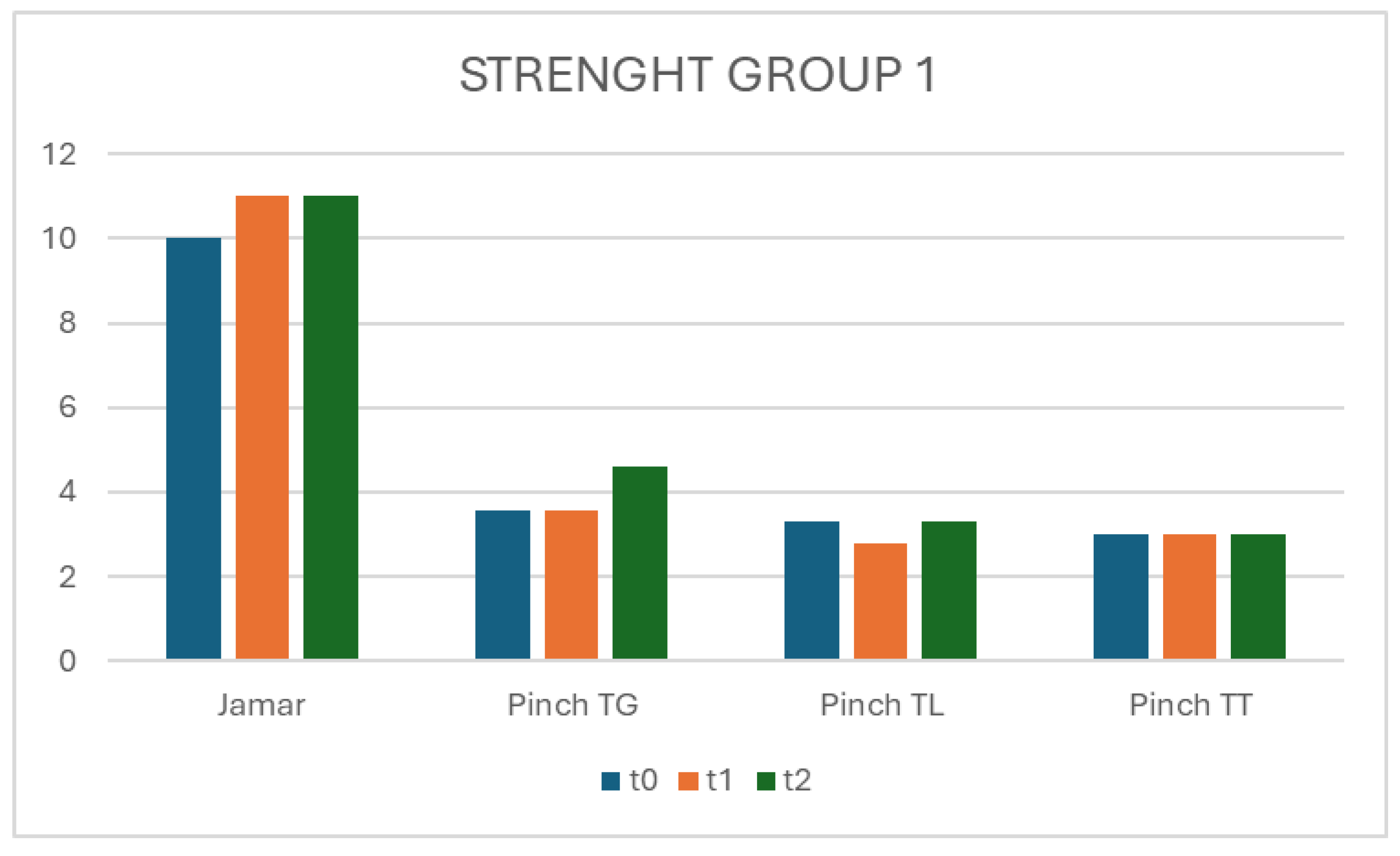

Figure 3.

A and B: In the evaluation of hand grip strength in both groups at T1, the strength ranged from 10-18 kg, increasing from T2 to T3 with a value of 27kg for group 0 and 11kg for group 1.

Figure 3.

A and B: In the evaluation of hand grip strength in both groups at T1, the strength ranged from 10-18 kg, increasing from T2 to T3 with a value of 27kg for group 0 and 11kg for group 1.

In the Pinch test at TG, TL and TT, there is an improvement in group 1 compared to group 0 from T0 to T2.

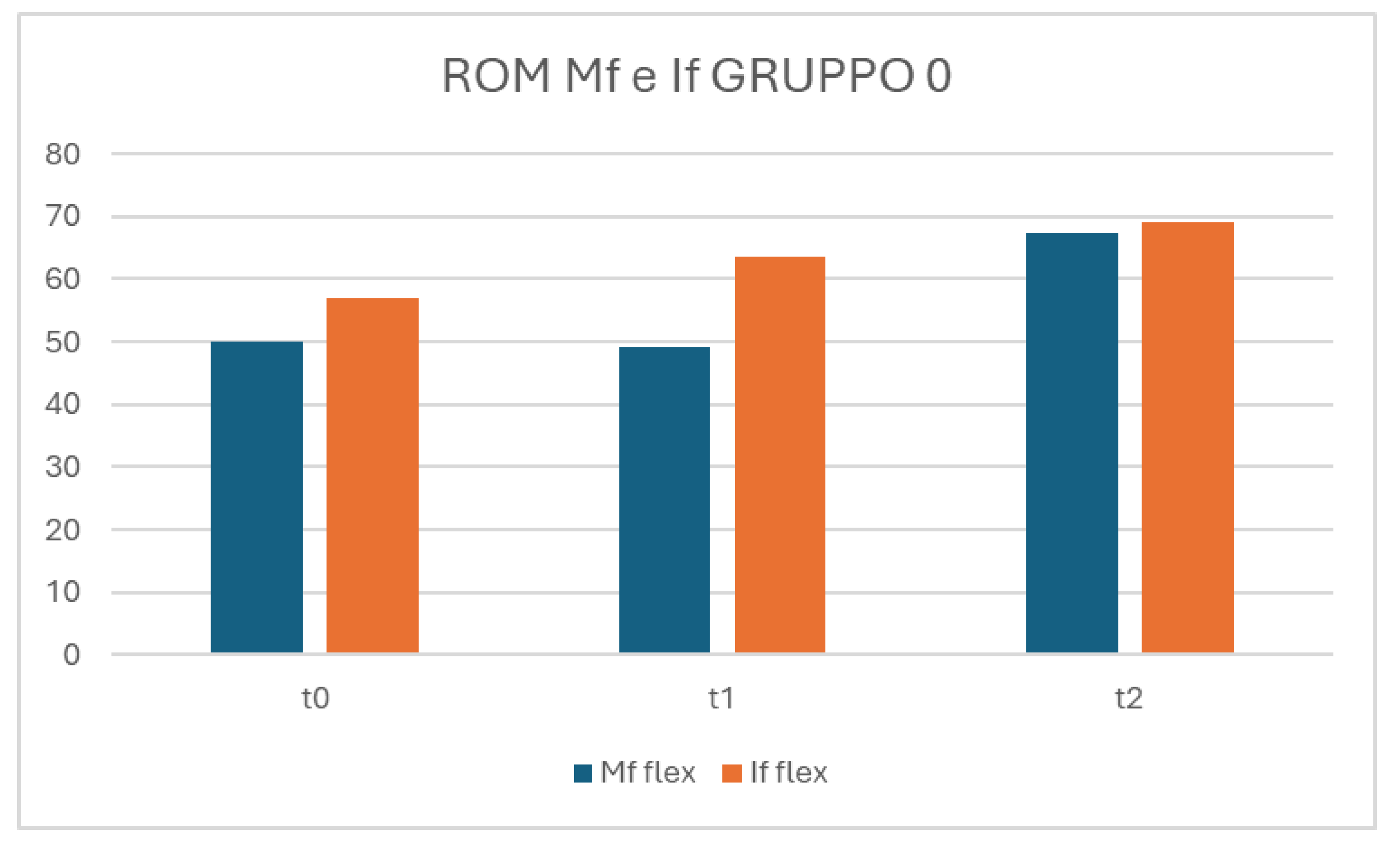

Figure 4.

A and B: In the ROM of flex MF and IF, there is a growing trend highlighted in both groups between t0 and t2, but with improvement in group 1.

Figure 4.

A and B: In the ROM of flex MF and IF, there is a growing trend highlighted in both groups between t0 and t2, but with improvement in group 1.

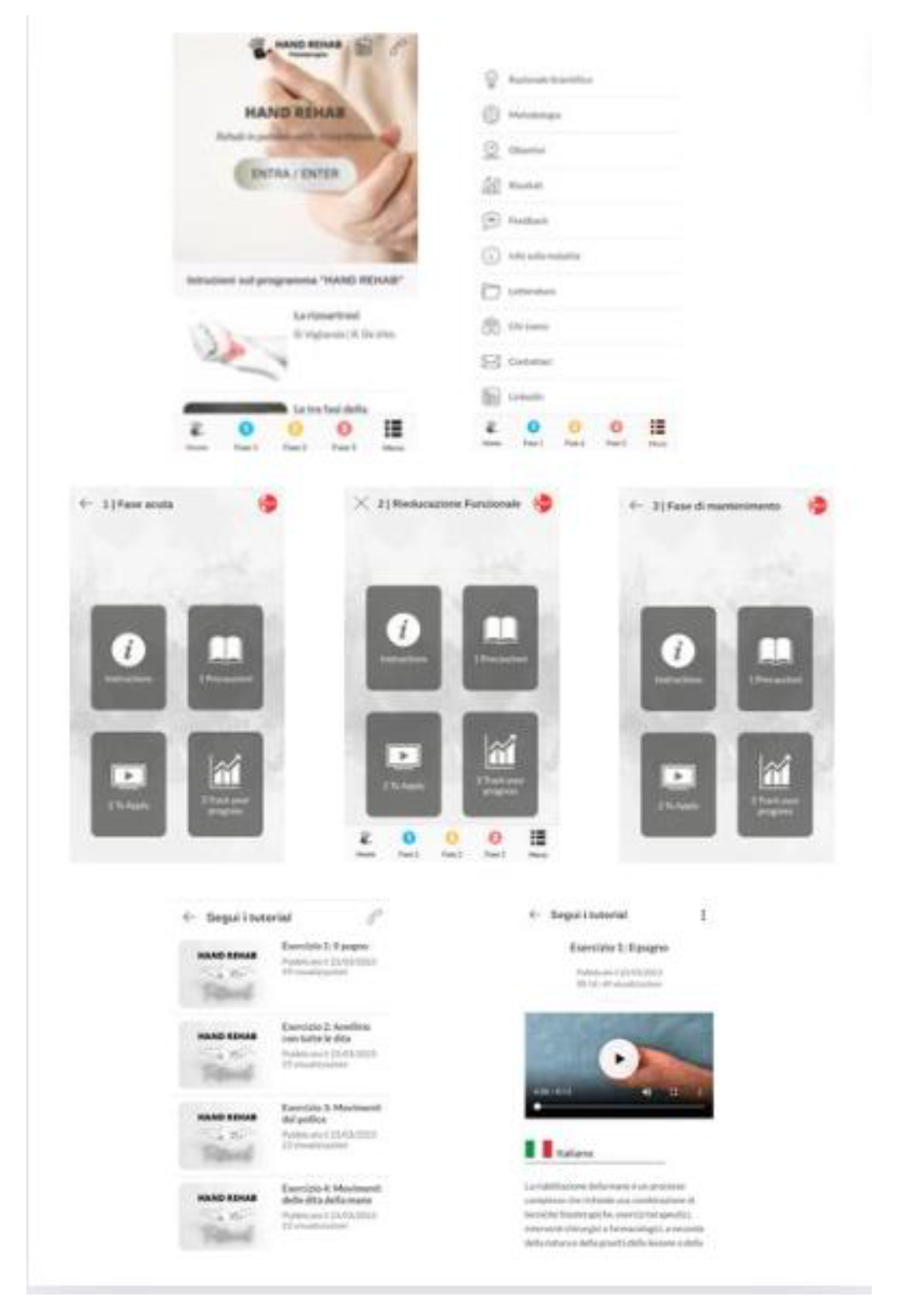

Figure 5.

App Hand Rehab. The first row displays screenshots of the homepage and menu page. The second row shows screenshots of the homepages for phases 1, 2, and 3. The third row includes screenshots of the exercise list for phase 1 and the video page for one of the exercises.

Figure 5.

App Hand Rehab. The first row displays screenshots of the homepage and menu page. The second row shows screenshots of the homepages for phases 1, 2, and 3. The third row includes screenshots of the exercise list for phase 1 and the video page for one of the exercises.