Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Literature on XaaS

2.1. Advantages of XaaS

2.2. Economies of Scale Linked to Ownership

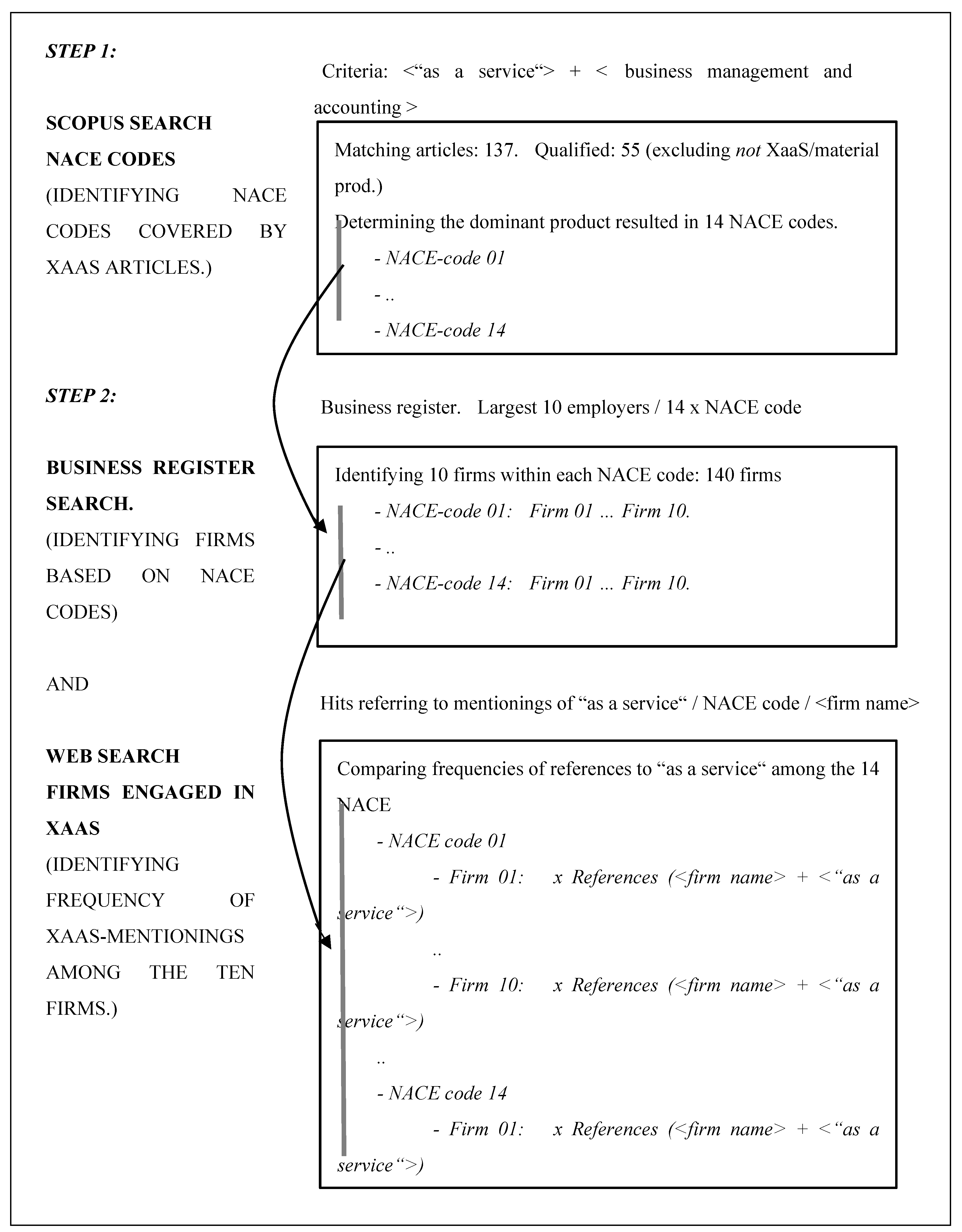

3. Methodology

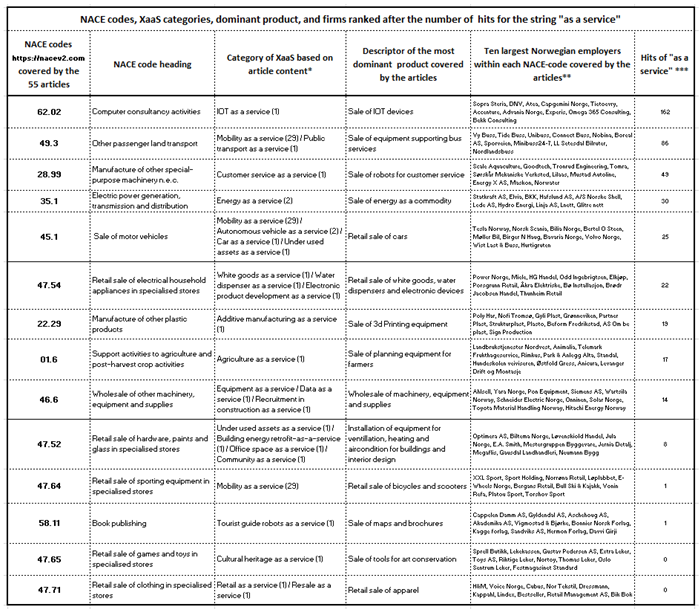

Research Step 1

Research Step 2

- -

- The first criterion is examined by using the search engine “proff.no”. This search engine is linked to the Norwegian government’s official company register where NACE codes are included as search criteria9. Here we identify the ten largest employers10 among the limited liability companies registered within each of the 14 NACE codes identified in research step 1 (140 firms in total).

- -

- The second criterion is included by conducting a Google search on any text mentioning <name of firm> and the text <“as a service”>. We count how many qualified matches there are per product category (NACE code). Google is in this text not used to assess research results, or to consider specific claims, but to compare the relative number of matches in searches for “as a service” and a particular firm name. If there is a bias in the data or weights that Google relies on, we would not assume that this would create a systematic bias among the NACE codes in our sample.

The Validity of This Design

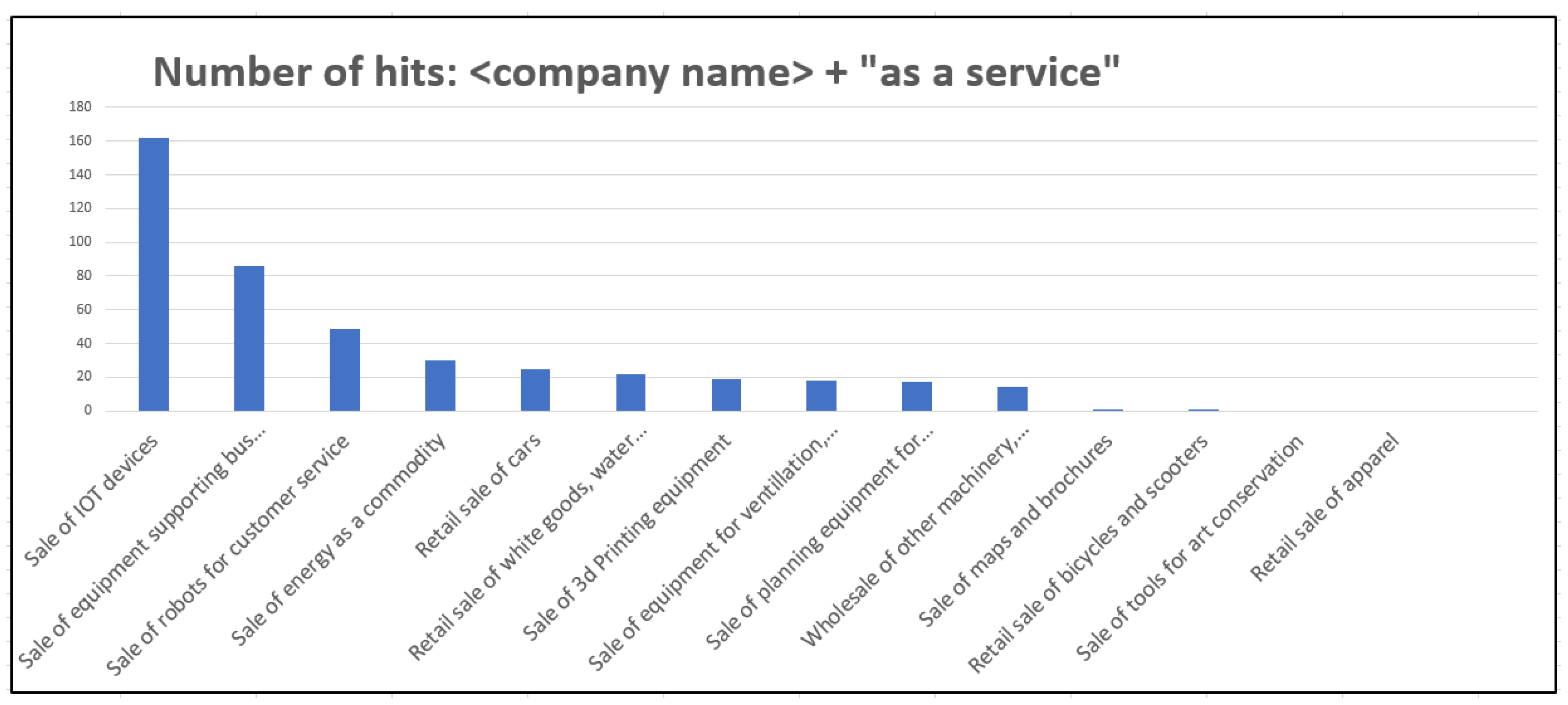

4. Results

- -

- Energy as a service / Sale of energy as a commodity,

- -

- Equipment as a service / Wholesale of machinery, equipment, and supplies

- -

- Tourist guide robots as a service / Sale of maps and brochures

- high value products, demanding maintenance, or

- allowing real-time monitoring.

- either low value products, or

- moderate or no maintenance demand, or

- products where real-time monitoring is difficult.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

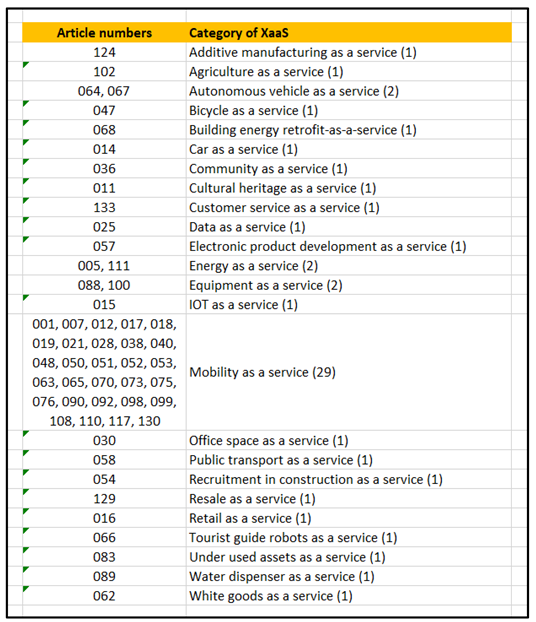

Appendix A. The XaaS Categories Included in the Scopus Search Result of Peer Reviewed

|

| 1 | Based on the description of the concepts in Merriam Webster dictionary and Wikipedia, we may distinguish between three service models: To ”rent” something refers to a customer possessing a good in return for a periodic payment. To “lease” something may cover a rent agreement but is typically used when there are additional conditions to be fulfilled and/or when the customer has an option to purchase the good after a given period. To “license” something is to receive a formal permission – often granted by a public authority – to utilise or control a good for a given period. |

| 2 | In SaaS vendors manage all tasks linked to the customer’s access and upgrading of software. In IaaS vendors provide and operate the hardware their customers need. In “platforms as a service”, vendors provide the hardware and the operating system used by the customer’s developer (e.g. Waters, 2005 and Chai, 2022). |

| 3 | The reference; “Right of disposal“ is here understood in the meaning of Merriam Webster; “authority to make use of as one chooses“. |

| 4 | Business services are also being included a spart oft he XaaS economy in some texts. Goldman and Sachs describe companies that facilitate outsourcing as “servicer companies“ (Goldman Sachs, 2018). |

| 5 | The SCOPUS search used the following search string; “(TITLE-ABS-KEY ("economies of scale") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("economy of scale")) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("everything as a service") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("XaaS") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("servitization") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("product service-system"))“ |

| 6 | The search string used in Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY ("as a service" ) AND PUBYEAR > 2020 AND DOCTYPE ( ar ) AND SUBJAREA ( busi ) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "cloud" ) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "software" ) AND NOT SUBJAREA ( comp ) |

| 7 | The coding of most dominant NACE code was done with the assistance of Chat GPT-4. Chat GPT-4 was given access to the NACE nomenclature (four digits) and then a prompt, including the dominant product in the peer-review article was submitted. Chat GPT-4 returned the most relevant NACE codes. All results were checked and confirmed manually to prevent any mistakes or misunderstandings. Finally, the researcher determined the dominant NACE code/product in each article. |

| 8 | This phrase is common in Norway and has no exact equivalent in Norwegian. |

| 9 | ”Proff” is a brand for the Norwegian market owned by the Finish company Enento. Proff relies on several public databases in Norway: https://innsikt.proff.no/kilder/

|

| 10 | The number of employees was chosen as a criterion because alternatives such as turnover, or market value, could be linked to funds or accumulated turnover in holding companies with firm names that are not relevant for the debate on management strategies and contract models. |

| 11 | This is shown in the the data file including the results from the search on proff.no. (See link in the appendix.) |

| 12 | Link to the full list of articles: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1LoDBgJZGDo_i3Gwo4nKGY6TmtLpR3oHV/edit

|

| 13 |

Link to Table 4, including the column with the URLS to all the proff.no searches:

|

| 14 |

Link to the overview of all Google searches for firms and “as a service”:

|

References

- Aboulamer, A. Adopting a circular business model improves market equity value. Thunderbird International Business Review 2017, 60, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardagna, C.A.; Damiani, E.; Frati, F.; Rebeccani, D.; Ughetti, M. Scalability patterns for platform-as-a-service. In 2012 IEEE Fifth International Conference on Cloud Computing, 2012; pp. 718–725. [CrossRef]

- Azcarate-Aguerre, J.F.; Conci, M.; Zils, M.; Hopkinson, P.; Klein, T. Building energy retrofit-as-a-service: A Total Value of Ownership assessment methodology to support whole life-cycle building circularity and decarbonisation. Construction Management and Economics 2022, 40, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Evans, S.; Neely, A.; Greenough, R.; Peppard, J.; Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Braganza, A.; Wilson, H.; et al. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of engineering manufacture 2007, 221, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Friedrich, R.; Bash, C.; Goldsack, P.; Huberman, B.; Manley, J.; Patel, C.; Ranganathan, P.; Veitch, A. Everything as a Service: Powering the New Information Economy. Computer 2011, 44, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumers, M.; Dickens, P.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. The cost of additive manufacturing: Machine productivity, economies of scale and technology-push. Technological forecasting and social change 2016, 102, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Rauter, R. Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organisation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 140, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. On taxation and the control of externalities. The American Economic Review 1972, 62, 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Benlian, A.; Hess, T. Opportunities and risks of software-as-a-service: Findings from a survey of IT executives. Decision support systems 2011, 52, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, M.; Rondini, A.; Pezzotta, G. A systematic review of value metrics for PSS design. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchi, G.; Cugno, M.; Castagnoli, R. Economies of Scale and Network Economies in Industry 4.0. Symphonya. 0. Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management 2018, (2), 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Canback, S.; Samouel, P.; Price, D. Do diseconomies of scale impact firm size and performance? A theoretical and empirical overview. ICFAI Journal of Managerial Economics 2006, 4, 27–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, W. Software as a Service (SaaS). Text on TechTarget.com. 2022. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcloudcomputing/definition/Software-as-a-Service?vgnextfmt=print.

- Chandler, A.D. The visible hand. The Managerial Revolution in American Business; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1977.

- Chen, S.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Hsu, C. A new approach to integrate internet-of-things and software-as-a-service model for logistic systems: A case study. Sensors 2014, 14, 6144–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudary, S.P. “An introduction to interaction-first businesses”. Chapter one in Chourday, S.P. (ed.) Platform Scale: How an emerging business model helps startups build large empires with minimum investment. Platform Thinking Labs. 2015.

- Chui, M.; Manyika, J.; Miremadi, M. Where machines could replace humans-and where they can’t (yet). McKinsey Quarterly 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The Nature of the Firm/Coase Ronald H. Economics 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cognite, A.S. “The digital twin: The evolution of a key concept of industry 4.0.”. Blog article. 2021. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.cognite.com/en/blog/digital-twin-evolution-1.

- Cooper, T. The durability of consumer durables. Business Strategy and the Environment 1994, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Coony, R.; Gould, S.; Daly, A. “Guidelines for life cycle cost analysis”. Published by Stanford University in October 2005. 2005.

- Dhebar, A. Preinstalled functionality as a service. Business Horizons 2023, 66, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. “Everything-as-a-service. Modernising the core through a service lens”. Deloitte University Press Update. 2017. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/tech-trends/2017/everything-as-a-service.html.

- Deloitte Insights. “Enterprise IT: Thriving in disruptive times with cloud and as-a-service. Deloitte Everything-as-a-Service Study, 2021 edition.” 2021. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/technology/enterprise-it-as-a-service.html.

- Economicsonline.co.uk. Website on economics. Posted article: “Economies of scale”. 2022. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/business_economics/economies_of_scale.html/.

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. Report. 2013. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf.

- Fallahi, S.; Mellquist, A.C.; Mogren, O.; Listo Zec, E.; Algurén, P.; Hallquist, L. Financing solutions for circular business models: Exploring the role of business ecosystems and artificial intelligence. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 32, 3233–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogliatto, F.S.; Da Silveira, G.J.; Borenstein, D. The mass scustomisation decade: An updated review of the literature. International Journal of production economics 2012, 138, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes Insights. The Big Promise of Everything-As-A-Service: Ongoing Revenue, Smarter Services. AI Issue 2, published 21st of September 2018. 2018. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/insights-intelai/2018/09/21/the-big-promise-of-everything-as-a-service-ongoing-revenue-smarter-services/.

- Fortune Business Insights. Everything as a Service Market Size. 2023. Downloaded text from website, August 2024. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/everything-as-a-service-xaas-market-102096.

- Fryer, V. “The History of SaaS: From Emerging Technology to Ubiquity.” 2020. Blog article posted on bigcommerce.com. Downloaded, August 2025. Available online: https://www.bigcommerce.com/blog/history-of-saas/.

- Generes, T.O. Get Ready For The Product-As-AService Revolution. 2020. Article in Forbes October 15, 2020. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/servicenow/2020/10/15/get-ready-for-theproduct-as-a-service-revolution/?sh=1b720e3f4226.

- Goldhar, J.D.; Jelinek, M. Plan for economies of scope. Harvard Business Review 1983, 61, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Sachs. “The Everything-as-a-service economy”. 2017. Report (92 pages) published by The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. Downloaded in October 2025. Available online: https://knowen-production.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/attachment/file/5276/Global%2BMarkets%2BInstitute_%2BThe%2BEverything-as-a-Service%2BEconomy%2B.pdf.

- Häckel, B.; Karnebogen, P.; Ritter, C. AI-based industrial full-service offerings: A model for payment structure selection considering predictive power. Decision Support Systems 2022, 152, 113653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldi, J.; Whitcomb, D. Economies of scale in industrial plants. Journal of Political Economy 1967, 75, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleberg, D.; Martinac, I. Indoor Climate as a Service: A sdigitalised approach to building performance management. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 588, No. 3, p. 032013). IOP Publishing. 2020.

- Han, J.; Heshmati, A.; Rashidghalam, M. Circular economy business models with a focus on servitisation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K. Text published on Linkedin. Rolls-Royce & Jet Propulsion-as-a-Service. 2015. Downloaded, August 2025. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rolls-royce-jet-propulsion-as-a-service-kristofer-hunt.

- Ipacs, D. “The History of Cloud Computing: Tracing Its Evolution and Impact”. 2023. Text posted on the website of bluebirdinternational.com. Downloaded, August 2025. Available online: https://bluebirdinternational.com/history-of-cloud-computing/.

- Ingham, S. “public good”. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2018. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/public-good-economics.

- Iqbal, R.; Butt, T.A. Safe farming as a service of blockchain-based supply chain management for improved transparency. Cluster Computing 2020, 23, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaczynska, E.; Outterson, K.; Mestre-Ferrandiz, J. Business Model Options for Antibiotics: Learning from Other Industries. Boston Univ. School of Law, Public Law Research Paper No. 15-05. 2015.

- Janssen, M.; Joha, A. Challenges for adopting cloud-based software as a service (saas) in the public sector. ECIS 2011 Proceedings. 80. 2011. Downloaded March 2025. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/80/.

- Krancher, O.; Luther, P.; Jost, M. Key affordances of platform-as-a-service: Self-sorganisation and continuous feedback. Journal of Management Information Systems 2018, 35, 776–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.H.; Wirtz, J. AI in Customer Service – A Service Revolution in the Making. In Artificial Intelligence in Customer Service: Next Frontier for the Global World; Sheth, J., Jain, V., Mogaji, E., Ambika, A., Eds.; McMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, P.; Keeble, J.; McNamara, R. Circular advantage: Innovative business models and technologies to create value in a world without limits to growth. Accenture Strategy. 2014. Downloaded in October 2024. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2022-02/Accenture-Circular-Advantage-Innovative-Business-Models-Technologies-Value-Growth.pdf.

- Lacy, P.; Rutqvist, J. Waste to wealth: The circular economy advantage; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2015; Volume 91. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Fu, D.; Zhu, J.; Dasmalchi, G. Cloud computing: IT as a service. IT professional 2009, 11, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Linux Information Project (linfo.org). “Economies of scale definition”. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: http://www.linfo.org/economies_of_scale.html.

- London Printer Rentals. Article on their website: Photocopier Leasing & Photocopier Rental. 2023. Downloaded in August 2024. Available online: https://www.londonprinterrentals.com/printer-rental-photocopier-leasing/photocopier-leasing-photocopier-rental/.

- Manavalan, E.; Jayakrishna, K. A review of Internet of Things (IoT) embedded sustainable supply chain for industry 4.0 requirements. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 127, 925–953. [Google Scholar]

- Manvi, S.S.; Shyam, G.K. Resource management for Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) in cloud computing: A survey. Journal of network and computer applications 2014, 41, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, J. The effect of income growth on the mix of purchases between disposable goods and reusable goods. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2007, 31, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorato, L. “Beyond the asset: The future of the product as a service”. 2018. Article in Leasing Life. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.dllgroup.com/us/en-us/-/media/Project/Dll/United-States/Images/New-Blogs/Product-as-a-service-new-normal-for-equipment-manufacturers/2018LeasingLifeAprilEditionProductasaService.pdf.

- Montes, J.O.; Olleros, F.X. Microfactories and the new economies of scale and scope. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2019, 31, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Vieira, M.; Ruiz, A.A.; Navarro, D. New business models for pharmaceutical research and development as a global public good: Considerations for the WHO European Region. Oslo Medicines Initiative technical report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Downloaded March 2025. Available online: https://repository.graduateinstitute.ch/record/300339?v=pdf.

- Moore, J. Article on corporate website. The Steps Of Installing An Entrance Mat. 2019. Downloaded in August 2024. Available online: https://www.thehouseidreamof.com/the-steps-of-installing-an-entrance-mat/.

- Neely, A.; Benedettini, O.; Visnjic, I. The servitisation of manufacturing: Further evidence. In “18th European operations management association conference (Vol. 1)”. 2011.

- Ong, O. Corporate newsletter. The Top 10 Bottleless Water Cooler Manufacturers In The USA. 2021. Downloaded in August 2023. Available online: https://www.sourcifychina.com/top-water-cooler-manufacturing-compare/.

- Perzanowski, A.; Schultz, J. The end of ownership: Personal property in the digital economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J., II. Mass Customisation: The New Frontier in Business Competition; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, Massachusetts, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Victor, B.; Boynton, A.C. Making mass customisation work. Harvard business review 1993, 71, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rabetino, R.; Kohtamäki, M.; Gebauer, H. Strategy map of servitisation. International Journal of Production Economics 2017, 192, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddats, C.; Kowalkowski, C.; Benedettini, O.; Burton, J.; Gebauer, H. Servitisation: A contemporary thematic review of four major research streams. Industrial Marketing Management 2019, 83, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V. “Economies of Scale, Economies of Scope.”. 2012. Published on Ribbonfarm.com. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2012/10/15/economies-of-scale-economies-of-scope/.

- Ryan, S. “EaaS, Everything as a service”. 2019. Article published in Medium.com. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/eaas-everything-as-a-service-5c12484b0b4e.

- Santa-Maria, T.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Baumgartner, R.J. How do incumbent firms innovate their business models for the circular economy? Identifying micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 1308–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, G. Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe. Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the McKinsey Center for Business and Environment 2016, 1-22. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthurFoundation_Growth-Within_July15.pdf.

- Sousa, B.; Arieiro, M.; Pereira, V.; Correia, J.; Lourenço, N.; Cruz, T. ELEGANT: Security of Critical Infrastructures With Digital Twins. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 107574–107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnicek, N. Platform capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stahel, W.R. The product life factor. An Inquiry into the Nature of Sustainable Societies: The Role of the Private Sector. Series: Mitchell Prize Papers, NARC. 1982.

- Stahel, W.R. The Performance Economy. Second edition. Palgrave Macmillan. 2010.

- Svensson, N.; Funck, E.K. Management control in circular economy. Exploring and theorising the adaptation of management control to circular business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 233, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systemiq. «Everything as a service”. 2021. Report published on website. Downloaded, February 2025. Available online: https://www.systemiq.earth/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/XaaS-MainReport.pdf.

- Taneja, H. The end of scale. MIT Sloan Management Review 2018, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- The Business Research Company. Everything as a Service Market Set to Reach $1660.21 Billion by 2029 with 21% Yearly Growth. 2025. Statistics published on openpr.com. Downloaded March 2025. Available online: https://www.openpr.com/news/3888699/everything-as-a-service-market-set-to-reach-1660-21-billion.

- Tsai, W.; Bai, X.; Huang, Y. Software-as-a-service (SaaS): Perspectives and challenges. Science China Information Sciences 2014, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight types of product–service system: Eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from usProNet. Business strategy and the environment 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alstyne, M.W.; Parker, G.G.; Choudary, S.P. Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy. Harvard business review 2016, 94, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ostaeyen, J.; Van Horenbeek, A.; Pintelon, L.; Duflou, J.R. A refined typology of product–service systems based on functional hierarchy modeling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 51, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. European management journal 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, D.A.; Negro, S.O.; Verweij, P.A.; Kuppens, D.V.; Hekkert, M.P. Exploring barriers to implementing different circular business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 222, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, T. Text published on Linkedin. Why Tires-as-a-Service will become more important (TaaS). 2020. Downloaded, August 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-tires-as-a-service-become-more-important-taas-theo-de-vries-1c/.

- Waldman, M. Durable goods theory for real world markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2003, 17, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, B. Software as a service: A look at the customer benefits. Journal of Digital Asset Management 2005, 1, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; The Free Press: New York, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| ADVANTAGES OF EVERYTHING AS A SERVICE (XAAS) IN THE LITERATURE | ||

| Advantages | Authors | |

| 1 | Improves customers’ expense model | Stahel (1982), Lin et al. (2009), Benlian & Hess (2011), Janssen & Joha (2011) |

| 2 | XaaS is well adapted to servitization which may boost sales | Vandermerwe & Rada (1988), Neely et al., (2011), Forbes Insights (2018), Raddats et al. (2019), Han et al. (2020), Systemiq, (2021) |

| 3 | Systems for customer and product feedback is easier to implement | Rabetino-et-al. (2017), Krancher et al. (2018) |

| 4 | Mass customisation is easier to implement. | Goldhar & Jelinek (1983), Pine (1993), Pine et al. (1993) |

| 5 | XaaS is well adapted for implementing machine learning and AI | Chui et al. (2016), Cognite (2021), Halleberg & Martinac (2020), Sousa et al. (2021), Kunz & Wirtz (2023) |

| 6 | Increasing flexibility and reduces risks | Stahel (2010), Ardagna et al. (2012), Manvi & Shyam (2014), Tsai et al., (2014) |

| 7 | The suppliers have an incentive to produce higher quality products | Banerjee et al. (2011), Collins et al. (2017), Migliorato, L. (2018), Forbes Insights (2018) |

| 8 | More time-efficient use of products | Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2013), Schulze (2016), Aboulamer (2017) |

| 9 | Incentives for prolonging the life cycle of products | Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2013), Baumgartner & Rauter (2017), Aboulamer (2017), Google (2019) |

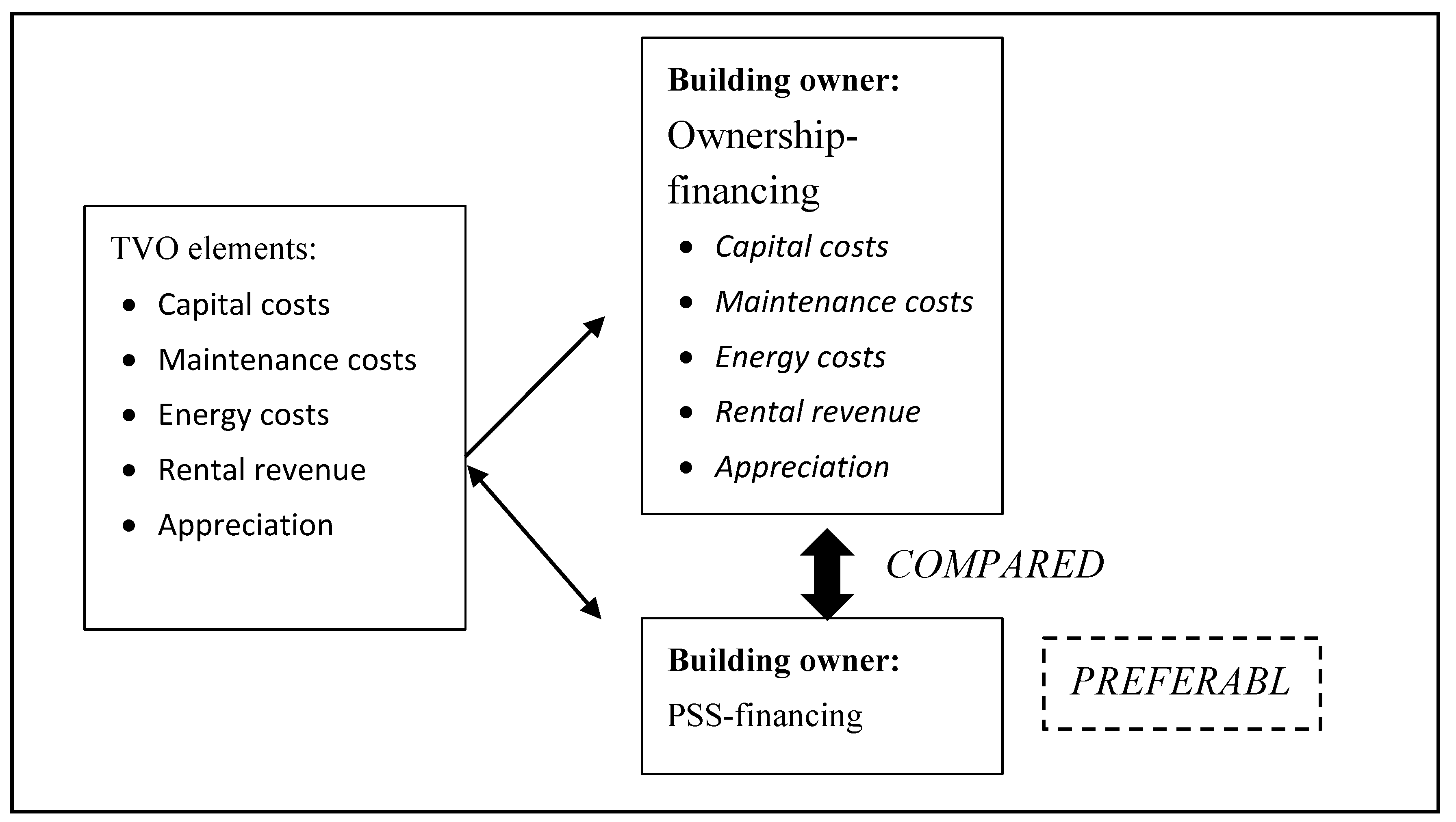

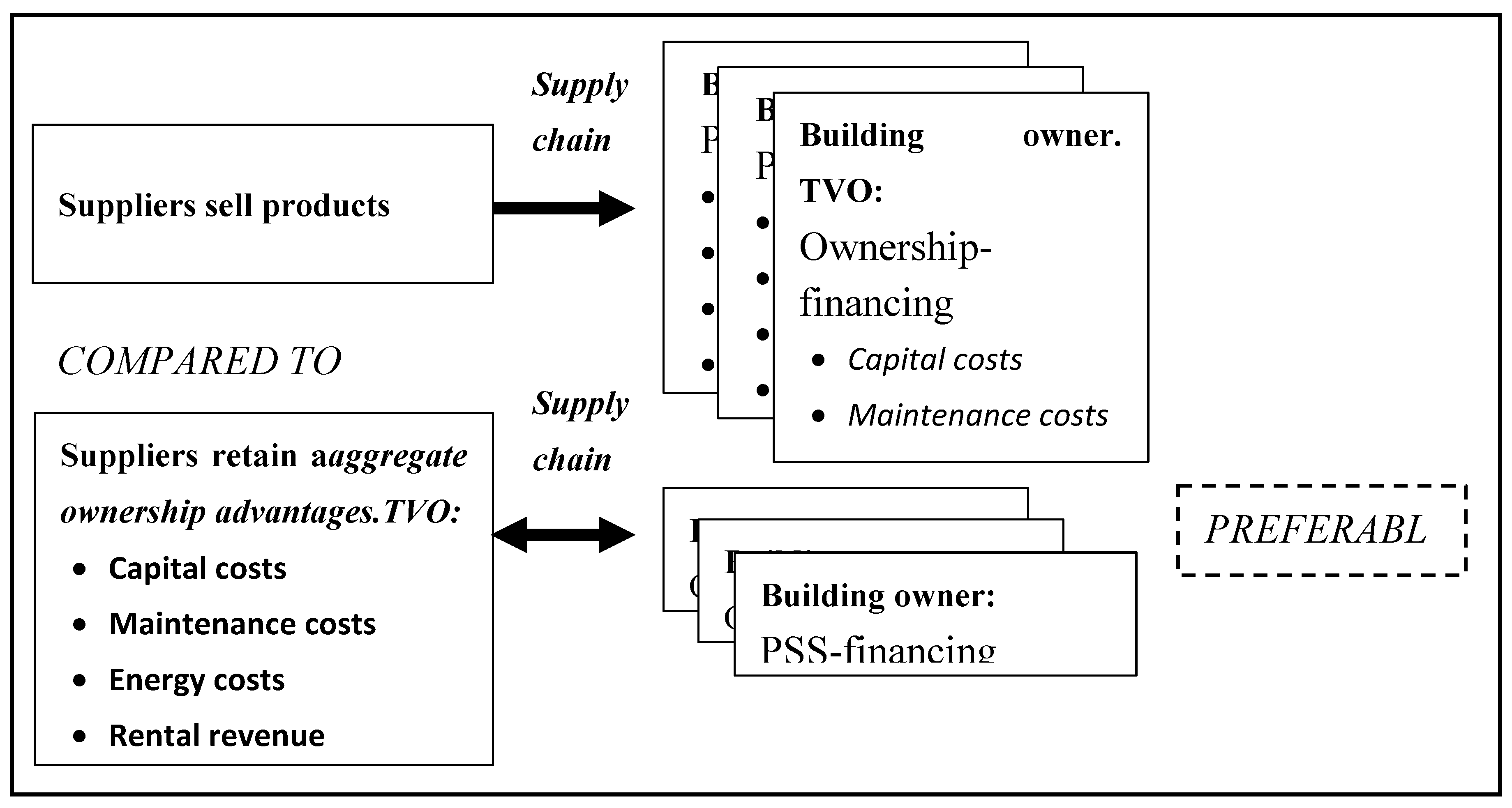

| The five elements of Total Value of Ownership (TVO) |

|---|

| 1. Capital costs linked to the initial investment and to project specific investment costs. |

| 2. Maintenance costs, costs of product upgrading, and training of both people and AI machines. |

| 3. Energy costs |

| 4. Value of operating revenue, including rental revenue and revenues from licensing and leasing |

| 5. Value of property appreciation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).