1. Introduction

The beginning of pharmaceutical manufacturing date back to pre-classic antiquity (3000 B.C), with compounded formulas (customized medications prepared by the combining and mixing of ingredients) using willow bark as an analgesic containing acetylsalicylic acid, which is now known worldwide as aspirin [

1]. In the 17th and 18th centuries, therapeutic innovations came to Europe from America and the East resulting in the chemical revolution of Lavoisier, the discovery by Edward Jenner of a vaccine against smallpox and the creation of the first non-official pharmaceutical standards [

1].

These developments marked the transition from traditional remedies, which lacked quality control, to a more scientific approach to medicine [

2]. This shift laid the foundation for modern pharmaceutical practices, driven by advancements in scientific analysis and manufacturing techniques fundamental for determining the efficacy and safety of medications [

2]. And these transformations were driven by the need for more standardized and reproducible medicinal products, ensuring consistency in treatment outcomes and today, drug preparation, analysis and treatment guidelines are standardized through pharmacopoeias, which are official publications regulating the quality of pharmaceutical drugs, excipients and flavoring agents [

1,

3]. These pharmacopeias specify testing methods, purity criteria, storage instructions, composition, and concentration to ensure uniformity in remedies approved by regulatory authorities, while upholding obligatory quality standards [

1,

3].

However, despite these significant advancements in both pharmaceutical manufacturing and quality control, such as, ventilation and cleanroom technologies, including HEPA filtration in air and water systems, single-pass airflow systems and automated sterilization with hydrogen peroxide vapor and UV light, challenges remain in ensuring consistent product quality and regulatory compliance [

4,

5].

Numerous cases of microbial contamination in pharmaceuticals have been reported, leading to severe health consequences. For example, in 2012, an outbreak of fungal meningitis in the United States was linked to contaminated steroid injections produced by the New England Compounding Center, resulting in over 750 infections and 64 deaths [

6]. Other incidents have involved bacteria such as

Burkholderia cepacia between 2016 and 2017 which was detected in 59 nursing facilities with 162 cases of bloodstream infections (BSI) and sepsis derived from contaminated saline flush syringes from an American manufacturer, which led to a national-scale recall [

7]. Another common contaminant is

Ralstonia pickettii commonly found in contaminated water used in pharmaceutical production and in 2015, 29 BSI were reported due to a specific lot of saline injections that was contaminated with the previously mentioned bacteria, leading to an eventual recall of 761 saline solutions in the same medical center [

8].

This issue, which is widely described in the literature, requires continuous vigilance and improvement in microbiological control measures as it can happen at any stage of the drug manufacturing, distribution, or dispensing process [

5]. Additionally, microbial contamination results in substantial financial losses due to equipment contamination, production stoppages, and subsequent investigations [

9].

An increasing number of hospitalized patients, both adults and pediatric, require pharmaceutical products that may not always be available due to quality control issues or supply shortages. A 2023 survey of 1,497 hospitals across 36 European countries revealed that 95% still experience shortages, compared to 86% in 2014 [

10,

11]. Manufacturing problems accounted for 67% of these shortages, with antimicrobials being the most in-demand category at 76% [

10,

11]. Despite this, reports of microbial contamination in pharmaceuticals within Europe remain critically under reported with many reports unable to identify the responsible microorganism [

12].

This review aims to assess the most recent methods for microbiological analysis in pharmaceuticals intended for human use and to compare with recent alternative pharmacopoeias like the United States Pharmacopoeia for discrepancies. It also examines pharmaceutical recall trends due to microbiological contaminations in Europe from January of 2020 to December of 2024, categorizing the recalls by types based on the free text descriptions posted by the European competent authorities (ECA) [

13] in addition to the United Kingdom [

14] and Switzerland [

15] within the recall announcements to conduct exploratory analyses for researchers interested in pharmaceutical manufacturing challenges.

Data indicated that approximately 70% of reported contamination cases lack specific microorganism identification, hindering effective monitoring and corrective measures. Among identified contaminants, B. cepacia and R. pickettii were the most prevalent, aligning with global trends reported by regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA). While recalls due to microbiological contamination showing a significant increase, particularly in 2023 and early 2024, with sterile products, including solutions for infusion and eye drops, being the most affected. The primary causes were non-compliance with sterility standards, contamination risks from raw materials, and inadequate environmental control measures during production. These findings also highlight growing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance (AMR) linked to pharmaceutical waste disposal and the potential role of preservatives in horizontal gene transfer.

2. Regulatory Framework and their challenges

In Europe, regulatory frameworks such as the EMA and the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare (EDQM) play a crucial role in setting and enforcing standards to ensure the microbiological integrity of pharmaceutical products [

16,

17].

The quality, safety and efficiency of all products intended for human use (i.e., pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, medical devices, water, foods and beverages), are under strict regulations which must be upkept to be placed on the market and the fulfillment of these requirements is obtained through peer reviewed, validated, standardized and controlled processes. These processes adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), hygiene standards, data collection and continuous training and inspections of personnel involved as reported by several European legislations [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Microbiological control of both sterile and non-sterile pharmaceuticals is essential to assure both the quality and safety of products intended for human use and must be specifically regulated and continuously updated [

23,

24].

This is essential because when microbial contamination does occur either by bacteria or fungi, they can cause serious harm to patients, including infection, sepsis, and other life-threatening conditions [

25]. Furthermore, microbial contamination can compromise drug stability, degrade active pharmaceutical ingredients or excipients, and alter formulation pH [

26,

27]. In nonsterile medicines, such as tablets, oral solutions, and topical creams, among other products, contamination can arise from both direct sources including raw materials (e.g., excipients, active pharmaceutical ingredients, water or packing material), manufacturing environment (air, surface, or operators), and manufacturing equipment [

26,

28]. Additionally, indirect sources include inadequate storage conditions (i.e., contamination during storage and/or transportation) and improper handling of medicines (i.e., contamination during their usage) [

26,

28].

Furthermore, the physicochemical properties of nonsterile medicine can also increase or decrease the proliferation of microorganisms with high-water-content formulations (e.g., solutions, suspensions, emulsions) and neutral to slightly acidic pH can promote microbial growth, while products with preservatives or antimicrobial accompanied with low-water-content forms (e.g., tablets, powders, capsules) are less susceptible to microbial growth [

29].

For sterile medicines such as solutions for infusion, injections and ophthalmic products, contamination can cause irreversible damage during the production and storage process, and noncompliance with sterility can often be detrimental to the patient’s health and even to their lives as many are immunocompromised [

30].

Microbial contamination is then exacerbated by the emergence of AMR, a growing global threat that has been significantly underestimated by the European Commission (EC). Based on the EC's own conservative estimates, AMR has caused the deaths of 400,000 European Union (EU) citizens since 2001 [

31]. Globally, AMR was responsible for 1.27 million deaths in 2019, with projections indicating that the global death toll could reach 10 million per year by 2050 [

31].

In addition, many pharmaceuticals that are given to patients or clients are not fully consumed by patients and improper disposal by pharmaceutical companies further contributes to environmental contamination as a lack of awareness regarding proper disposal methods has resulted in large quantities of unused or expired medications laden with antibiotics, resistance genes, and preservatives being discharged into wastewater and landfills posing risks to ecosystems and public health [

32].

As these pharmaceuticals persist in the environment, their components, including preservatives, can interact with microbial populations, resulting in AMR being developed which remains poorly understood, with recent studies indicating that sub-lethal concentrations of preservatives may promote horizontal transfer of AMR genes [

33]. Additionally, some microorganisms develop resistance through genetic mutations that modify their cell walls or alter enzymes responsible for antibiotic degradation, compounding the challenge of effective microbiological control [

34].

3. Microbiological Testing in Pharmaceuticals

Given these rigorous regulations, ensuring effective microbiological testing remains a critical challenge. The Ph. Eur. and the USP provide harmonized yet distinct microbiological testing guidelines, dividing methods into those for sterile and non-sterile products [

23]. The first section (Ph. Eur. 2.6.1) is for parenteral medicines or products that are required to be free from any viable microorganisms by applying methods such as membrane filtration or direct inoculation and is based on the aseptic inoculation of samples into fluid thioglycollate medium or Soybean-Casein Digest medium and incubation for up to 14 days with high-turbidity bacterial density (over 10

7 CFU/mL) (CFU = colony-forming units) indicating the presence of microorganisms [

23].

While largely aligned with USP Chapter 71 on sterility testing, key differences exist. For example, is the use in the Ph. Eur. of

Clostridium sporogenes (ATCC 19404 or 11437) and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027) as the standard anaerobe microorganisms, while USP permits as an alternative to

C. sporogenes the bacteria

Bacteroides vulgatus (ATCC 8482) and

Kocuria rhizophila (

Micrococcus luteus) ATCC 9341 as an alternative for

P. aeruginosa. As for neutralization and method suitability USP explicitly details β-lactamase validation for penicillin/cephalosporin testing while Ph. Eur. does not [

23,

35].

The second section (Ph. Eur. 2.6.12 and 2.6.13) is related to non-sterile pharmaceuticals which may include oral and topical formulations. These guidelines define strict limits on microbial presence, measured through total aerobic microbial count (TAMC), total yeast and mold count (TYMC), and specific pathogen testing [

23]. These methods are harmonized with USP chapters 61 and 62, and do not present significant differences [

35].

Among the many harmonized methods (Ph. Eur. 5.1.6), the counting of bacterial CFUs on agar plate by membrane filtration is the most common, while application of the “most probable number” is used when the other methods have failed with both requiring a long incubation time (1–3 days) [

23]. In agar, colonies may be formed by several related species of bacteria, and full identification takes up to seven days, whereas with the use of the “most probable number” method an approximate number of bacteria can be detected in a diluted test sample by measuring turbidity after incubation [

23].

In addition to the traditional methods, rapid methods exist for faster results and enable the detection of slow growing microorganisms compared to traditional culture-based techniques and fall into three main categories: growth-based methods, direct measurement, and cell component analysis [

23].

Growth-based methods, such as electrochemical detection [

36], gas monitoring [

23], bioluminescence [

37], chemiluminescence [

37], turbidimetry [

38], Radiometry using radioactive

14C [

37], ATP bioluminescence assay using luciferase enzyme [

39] and chromogenic media [

40], rely on microbial metabolism or proliferation to generate detectable signals [

23].

Direct measurement techniques, including solid phase and flow cytometry [

41], direct epifluorescent analysis [

42], and autofluorescence [

42], enable rapid detection of individual microorganisms without requiring growth [

23].

Cell component analysis encompasses phenotypic approaches, such as immunological assays [

38], fatty acid profiling [

43], Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy [

44] and biochemical assays [

45], as well as genotypic techniques like direct hybridization [

46], nucleic acid amplification (e.g., PCR) [

47], and genetic fingerprinting (e.g., RFLP, PFGE, VNTR) [

48].

Emerging molecular-based techniques not yet harmonized in the European pharmacopeias are revolutionizing rapid microbial detection one such example is NGS enabling the rapid and precise sequencing of DNA and RNA to identify microbial communities in mixed samples, although with complex pipelines and expensive equipment and regents [

49]. Several others have been developed but not yet used in the context of microbial detection in pharmaceuticals like microarray technology and especially MALDI-TOF MS which is an advanced technique that ionizes biomolecules for mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) analysis without fragmentation, enabling rapid, accurate detection of peptides, lipids, and oligonucleotides and identification of microorganism [

50,

51].

Although not microorganisms, bacterial endotoxins pose significant risks in parenteral products, eye drops, and medical devices. Endotoxins are highly pyrogenic, capable of triggering severe immune responses and septic shock [

52].

Consequently, the bacterial endotoxins test (BET) is a critical safety measure [

53]. Traditionally, BET methods, although still reliant on Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) derived from horseshoe crab blood, have brought up conservation concerns and driven the development of recombinant BET (rBET) methods, such as those using recombinant Factor C (rFC) [

54].

The Ph. Eur. has been a forefront in adopting these non-animal methods, including rFC-based assays under Chapter 2.6.32 since January 2021, reflecting a commitment to sustainable and ethical testing practices but in contrast, the USP only recently granted compendial status to rBET methods in Chapter 86, nevertheless creating up until now regulatory discrepancies and additional burdens for global pharmaceutical companies, as a lack of harmonization between the Ph. Eur. and USP complicates regulatory submissions [

54].

Some other harmonized methods for microbiological stability also overlook key tests, such as water activity in non-sterile drug products, which helps identify microorganisms capable of proliferating, and container-closure integrity in sterile products, which ensures a sterile environment and controls oxygen availability [

55].

And while USP chapters 922, 1112, and 1207 cover water activity and container-closure integrity testing, the Ph. Eur. lacks dedicated chapters for these methods, referencing them only in general chapters 3.2.9. and 3.2.1. [

23,

35].

4. Europe’s State of Microbial Contaminations

Despite several quality control methods, microbial contamination in pharmaceutical products remains a critical concern for public health and regulatory bodies in Europe [

12]. While comprehensive, up-to-date statistics specific to Europe are limited, available data and further studies can provide insight into trends and common contaminants [

12].

A cross-sectional study of all current recalls, market withdrawals, and safety alerts published by the European competent authorities pertaining to drugs was conducted. A manual review of all the recalls was also conducted to extract additional information including name of product and type, reason for contamination, and responsible contamination in Europe between January 2020 and December 2024.

Between 2012 and 2019, most FDA drug recalls in America were due to unidentified microbial contamination, accounting for 77% in non-sterile and 87% in sterile drugs [

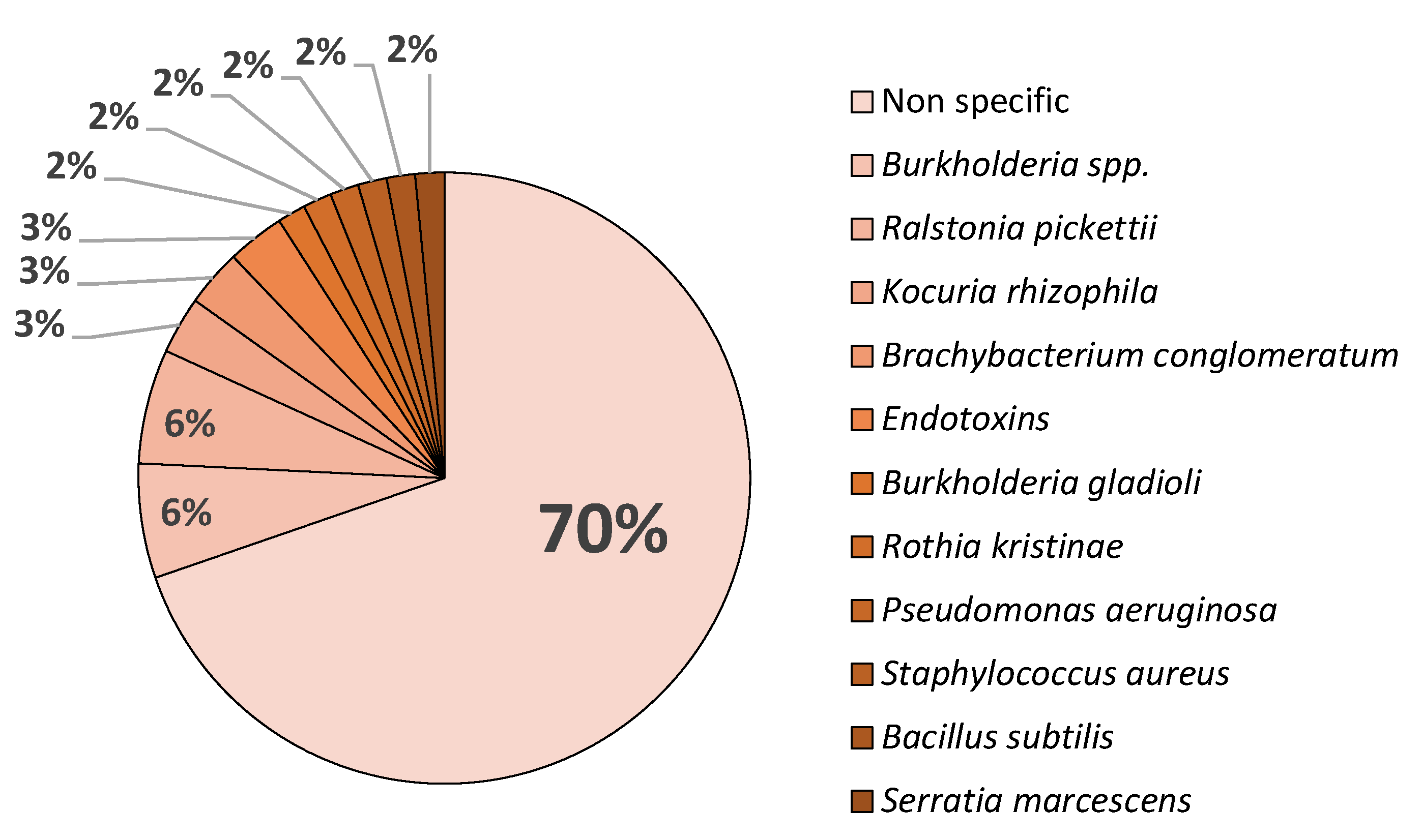

56]. These results align with the data collected for Europe between January 2020 and December 2025, as shown in

Figure 1, which indicates that 70 % of contaminants belong to unidentified microbial contamination.

While

B. cepacia followed by

R. pickettii being the most frequently identified bacteria in recalls [

56]. This matches with the data from FDA and EMA due to

Burkholderia spp. being the most frequently identified contaminants in pharmaceutical products [

57]. A study analyzing FDA recall data from 1998 to 2006 found that 22% of non-sterile product recalls were due to

Burkholderia contamination [

58], this trend although with a much lower sample size is observed in Europe with a total of 8% belonging to

Burkholderia spp. in both sterile and non-sterile pharmaceutical withdrawal, as shown in

Figure 1, while also being the prevalent isolated microorganism.

The presence of about 12% of all identified microbiological contaminants being gram-negative bacteria is also strongly associated in sterile pharmaceuticals with high water content (solutions for infusion and eye drops), while both gram-positives and negatives are capable of surviving and remain viable in dry environments for months, in the case of

Staphylococcus aureus,

P. aeruginosa and

Serratia marcescens [

9].

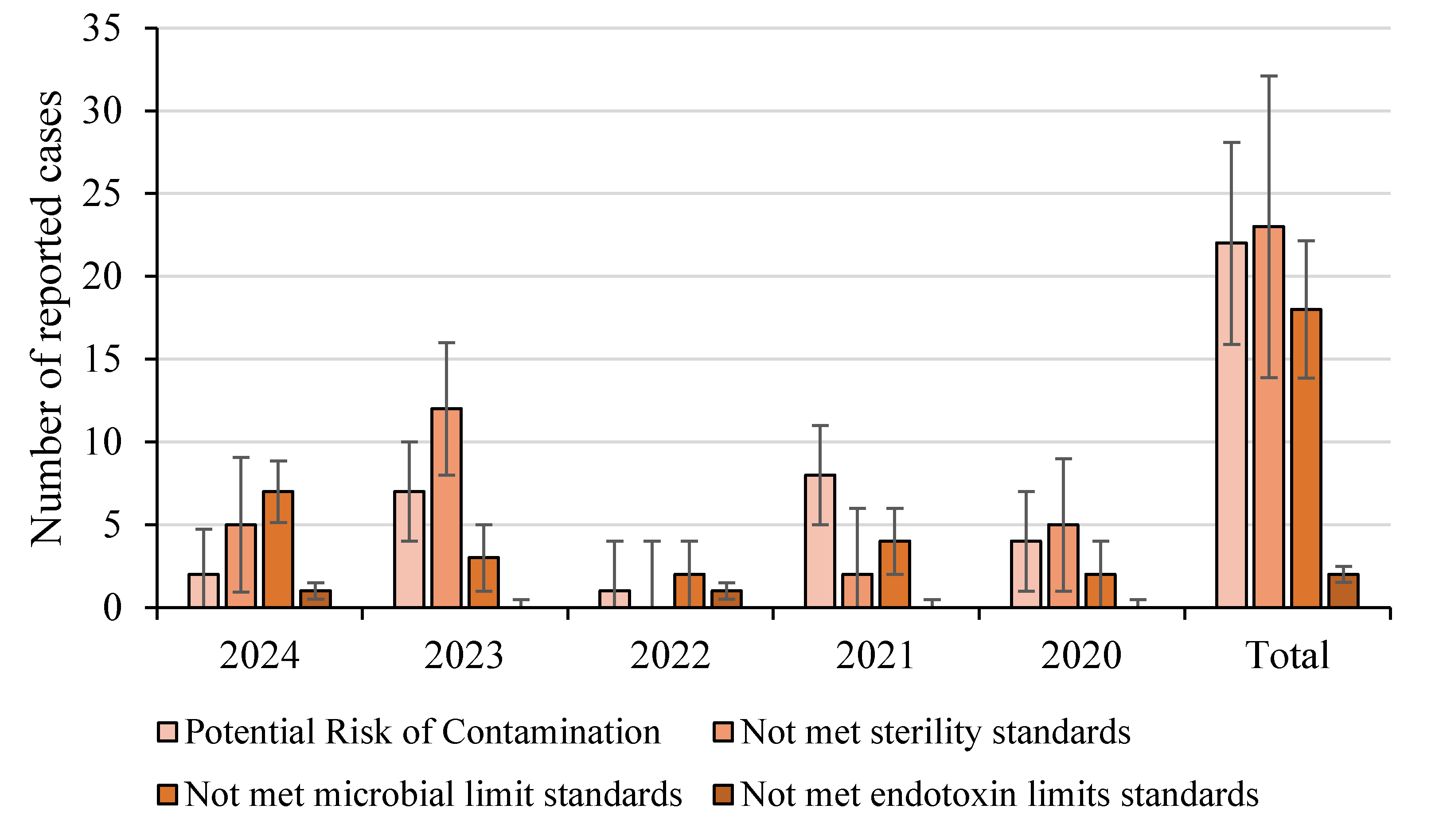

Examining the trend for pharmaceutical withdrawal between 2020 and 2021, microbial contamination-related recalls remained steady. This was likely due to COVID-19 disruptions affecting manufacturing and regulatory inspections while in 2022, there was a noticeable increase in recalls, with the pharmaceutical sector experiencing a 7.7% rise compared to the previous year, and compared to the data collected, few were due to microbial contaminations, shown in

Figure 2 [

59].

This upward trend continued into 2023, marking the fifth consecutive year of rising pharmaceutical recalls in Europe, with microbial contamination being a significant contributor. In the first quarter of 2024, European product recalls reached their highest quarterly total in over a decade, with the pharmaceutical sector seeing a 9.5% increase compared to the previous quarter, shown in

Figure 2 with a significant increase in sterility failures [

60].

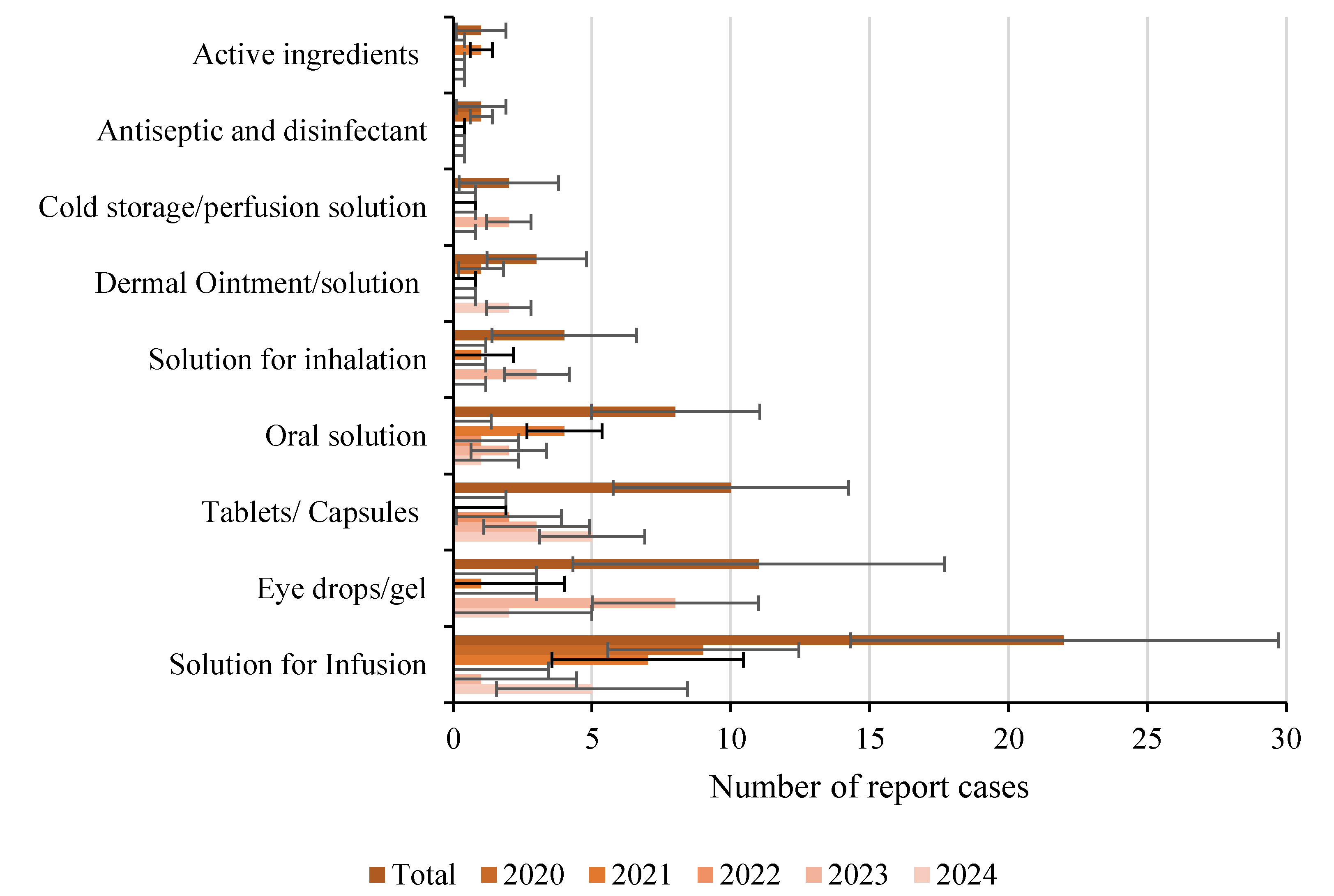

Additionally, the total number of withdrawals were most attributed to potential risks of contamination, (e.g., water supply contamination, container sterility failure, raw material contaminants), followed closely behind by non-compliance with sterility standards in sterile medication and microbial limits in non-sterile medication, with few report cases of endotoxin presence.

Many recalls stemmed from GMP deficiencies, highlighting the need for stricter microbiological controls in pharmaceutical manufacturing. However, these recalls also highlight shortcomings among the ECA in fully adhering to pharmaceutical standards, as a key issue is the lack of transparency in not providing to the general public complete reports detailing not only the specific microorganisms present in the contaminations but also the reason for the recall, as a “potential risk of contamination” can apply to both sterile and non-sterile pharmaceuticals, explaining why the total number of reported cases appears similar across both categories, with sterile pharmaceutics like solutions for infusion and eye drops being the most impacted as shown in

Figure 3.

This challenge not only exist in Europe but also in the USA due to the high frequency of recalls by the FDA indicating inadequate awareness of microbial contamination risk and poor implementation of relevant control programs with substantial evidence such as warning letters, alert notifications, and failures suggesting a direct relationship between the level of environmental control and the product’s final quality either it being sterile or non-sterile [

61,

62].

Of note is a study conducted between 2012 and 2014 by analyzing FDA drug recalls showed close to three thousand drug recalls, with the most common reason being contamination making up to 50% of recalls, followed by mislabeling, adverse reaction, defective product, and incorrect potency [

63].

5. Future Directions

As traditional microbial methods present challenges such as sample handling difficulties, culture-dependent limitations, and misidentification risks, future innovations must focus on overcoming these obstacles [

64,

65]. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning, emerges as a pivotal tool in addressing complex microbiological challenges, particularly in optimizing data for techniques like MALDI-TOF MS for microbial identification and AMR providing rapid, reliable, and cost-effective solutions for pharmaceutical microbiology [

66].

Beyond identification methods, innovative antimicrobial prophylactic strategies are also needed as alternatives or complements to chemical preservatives in pharmaceuticals and one potential solution is bacteriocins which are natural antimicrobial peptides produced by lactic acid bacteria that although still underexplored, evidences suggest bacteriocins offer high specificity against common contaminants, exhibit non-cytotoxicity in mammalian cells, and may help avoid antibiotic resistance [

67,

68].

Another approach would be the implementation of Quality by Design (QbD) approach in microbial risk assessment for pharmaceuticals, that would integrate risk management principles into manufacturing to ensure product safety and quality, by proactively identifying, evaluating, and controlling microbiological risks through critical quality attributes (CQAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs), minimizing contamination risks and enhancing regulatory compliance with techniques such as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to help detect contamination sources and establish preventive measures [

69,

70]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) (Q8, Q9, and Q10) support QbD through a science-based, risk-oriented approach, incorporating the design of experiments and real-time monitoring in order to enhance process understanding, reduces variability, and optimizes efficiency, ultimately improving product safety and efficacy [

70,

71].

A significant remaining challenge is the detection of low-bioburden or viable but non-culturable cells (VBNC), which conventional microbial methods struggle to identify [

72]. Metagenomic sequencing emerges as a powerful tool to address this issue, offering comprehensive microbial profiling. However, global harmonization of such advanced molecular methods is crucial for ensuring their widespread adoption in pharmaceutical microbiology [

72].

By combining AI-driven innovations, alternative antimicrobial strategies, risk-based manufacturing frameworks, and next-generation molecular methods, the future of pharmaceutical microbiology will move towards more accurate, efficient, and regulatory-compliant solutions.

4. Conclusions

The persistence of microbial contamination in pharmaceutical products underscores the complexity of maintaining microbiological quality and stability within the European regulatory framework. Despite stringent guidelines and ongoing advancements in testing methodologies, contamination-related recalls have increased. Furthermore, gaps in regulatory reports from the ECA across the EU reveal inconsistencies, including the lack of specific microbial identification and disparities in pharmacopeial harmonization, particularly in sterility testing. These challenges complicate contamination mitigation efforts, hinder effective risk assessment, and delay corrective actions.

This combined with the growing concern over AMR, linked to pharmaceutical waste disposal and the role of preservatives in gene transfer, adds another layer of concern, demanding more comprehensive regulatory approaches.

Addressing these challenges requires stronger international collaboration, increased investment in rapid microbial detection technologies, and regulatory frameworks that prioritize transparency and adaptability. The consequences of inadequate microbial control are severe, as pharmaceutical facilities may face prolonged shutdowns to investigate contamination sources and implement corrective measures, incurring substantial economic and reputational costs.

Innovative solutions such as AI, next-generation sequencing, and QbD principles offer promising avenues for improving microbiological control. Shifting from a reactive to a proactive approach will be essential in safeguarding pharmaceutical integrity, regulatory compliance, and most critically, patient safety in an increasingly complex and evolving pharmaceutical landscape.

Funding

This research was funded by the Programa Regional Lisboa (LISBOA2030-FEDER-00543200).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding authors

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| BET |

Bacterial endotoxins test |

| CFU |

Colony-forming units |

| CPPs |

Critical process parameters |

| CQAs |

Critical quality attributes |

| EC |

European Commission |

| EDQM |

European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare |

| EMA |

European medicine agency |

| EU |

European Union |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared |

| GMP |

Good Manufacturing Practices |

| ICH |

International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use |

| LAL |

Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate |

| MHRA |

United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency |

| NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

| Ph. Eur. |

European Pharmacopoeia |

| QbD |

Quality by Design |

| rBET |

recombinant BET |

| rFC |

Recombinant Factor C |

| TAMC |

Total aerobic microbial count |

| TYMC |

Total yeast and mold count |

| USP |

United States Pharmacopeia |

| VBNC |

Viable but non-culturable cells |

References

- Rodrigues M, Rodrigues I, Conceição J. Importância dos Medicamentos Manipulados na Terapêutica: Revisão histórica e estado atual. Acta Farm Port 2023;12:51–70.

- Blanco Barrantes J, Quesada MS, Rojas G, Loría A. A Journey through the History of Drug Quality Control, from Greece to Costa Rica. Int J Drug Regul Aff 2021;9:33–47. [CrossRef]

- Tabajara de Oliveira Martins D, Rodrigues E, Casu L, Benítez G, Leonti M. The historical development of pharmacopoeias and the inclusion of exotic herbal drugs with a focus on Europe and Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 2019;240:111891. [CrossRef]

- Hashim Z, Celiksoy V. Pharmaceutical products microbial contamination: approaches of detection and avoidance. Microbes Infect Dis 2024;0:0–0. [CrossRef]

- Ekeleme UG, Ikwuagwu VO, Chukwuocha UM, Nwakanma JC, Adiruo SA, Ogini IO, et al. Detection and characterization of micro-organisms linked to unsealed drugs sold in Ihiagwa community, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Access Microbiol 2024;6:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman CA, Malani AN. Fungal infections associated with contaminated steroid injections. Emerg Infect 10 2016:359–74. [CrossRef]

- Brooks RB, Mitchell PK, Miller JR, Vasquez AM, Havlicek J, Lee H, et al. Multistate Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia Complex Bloodstream Infections after Exposure to Contaminated Saline Flush Syringes: United States, 2016-2017. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:445–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen YY, Huang WT, Chen CP, Sun SM, Kuo FM, Chan YJ, et al. An Outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii Bloodstream Infection Associated with an Intrinsically Contaminated Normal Saline Solution. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017;38:444–8. [CrossRef]

- Eissa, ME. Distribution of bacterial contamination in non-sterile pharmaceutical materials and assessment of its risk to the health of the final consumers quantitatively. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 2016;5:217–30. [CrossRef]

- Casiraghi A, Centin G, Selmin F, Picozzi C, Minghetti P, Zanon D. Critical aspects in the preparation of extemporaneous flecainide acetate oral solution for paediatrics. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:1–12. [CrossRef]

- European Association of Hospital Pharmacists. EAHP 2023 Shortage Survey Report. Eur Assoc Hosp Pharm 2023:1–67.

- Santos AMC, Doria MS, Meirinhos-Soares L, Almeida AJ, Menezes JC. A QRM discussion of microbial contamination of non-sterile drug products, using FDA and EMA warning letters recorded between 2008 and 2016. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2018;72:62–72. [CrossRef]

- The European Medicines Agency - National competent authorities (human). EMA 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/eu-partners/eu-member-states/national-competent-authorities-human (accessed February 12, 2025).

- GOV.UK Alerts, recalls and safety information: medicines and medical devices. GOVUK 2025. https://www.gov.uk/drug-device-alerts (accessed January 29, 2025).

- Swissmedic - Batch recalls human medicines. SWISSMEDIC 2025. https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/en/home/humanarzneimittel/market-surveillance/qualitaetsmaengel-und-chargenrueckrufe/batch-recalls.html (accessed February 12, 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/homepage (accessed February 24, 2025).

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare 2025. https://www.edqm.eu/en/ (accessed February 24, 2025).

- Commission E. Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines In: The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union. Eur Comm 2011;4. https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-4_en (accessed February 18, 2025).

- Commission E. Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament on the hygiene of foodstuffs. Eur Comm 2004. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/852/oj/eng (accessed February 18, 2025).

- Commission E. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament on cosmetic products. Eur Comm 2009. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32009R1223 (accessed February 18, 2025).

- Commission E. Regulation (EC) No 83/2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Eur Comm 2001. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2001/83/oj/eng (accessed February 18, 2025).

- Commission, E. Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. Eur Comm 2005. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2005/2073/oj/eng.

- HealthCare ED for the Q of M&. European Pharmacopoeia. 11th Editi. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe; 2025.

- Hałasa R, Turecka K, Smoktunowicz M, Mizerska U, Orlewska C. Application of tris-(4,7-Diphenyl-1,10 phenanthroline)ruthenium(II) Dichloride to Detection of Microorganisms in Pharmaceutical Products †. Pharmaceuticals 2023;16:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Austin PD, Hand KS, Elia M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of microbial contamination of parenteral doses prepared under aseptic techniques in clinical and pharmaceutical environments: An update. J Hosp Infect 2015;91:306–18. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço FR, Bettencourt da Silva RJN. Simplified and Detailed Evaluations of the Uncertainty of the Measurement of Microbiological Contamination of Pharmaceutical Products. J AOAC Int 2024;107:856–66. [CrossRef]

- Ansari FA, Perazzolli M, Husain FM, Khan AS, Ahmed NZ, Meena RP. Novel decontamination approaches for stability and shelf-life improvement of herbal drugs: A concise review. The Microbe 2024;3:100070. [CrossRef]

- Dao H, Lakhani P, Police A, Kallakunta V, Ajjarapu SS, Wu KW, et al. Microbial Stability of Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Products. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018;19:60–78. [CrossRef]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Microbiological Quality Considerations in Non-sterile Drug Manufacturing Guidance for Industry. Food Drug Adm 2021:1–24.

- Song M, Li Q, Liu C, Wang P, Qin F, Zhang L, et al. A comprehensive technology strategy for microbial identification and contamination investigation in the sterile drug manufacturing facility—a case study. Front Microbiol 2024;15:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Rayan, RA. Pharmaceutical effluent evokes superbugs in the environment: A call to action. Biosaf Heal 2023;5:363–71. [CrossRef]

- Endale H, Mathewos M, Abdeta D. Potential Causes of Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance and Preventive Measures in One Health Perspective-A Review. Infect Drug Resist 2023;16:7515–45. [CrossRef]

- Cen T, Zhang X, Xie S, Li D. Preservatives accelerate the horizontal transfer of plasmid-mediated antimicrobial resistance genes via differential mechanisms. Environ Int 2020;138:105544. [CrossRef]

- Naveed M, Chaudhry Z, Bukhari SA, Meer B, Ashraf H. Antibiotics resistance mechanism. Elsevier Inc.; 2019. [CrossRef]

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. United States Pharmacopeia 11th Edition. 11th ed. United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2024.

- Shukla AK, Boruah JS, Park S, Kim B. Rapid Detection and Counting of Bacteria Using Impact Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem C 2024;128:13458–63. [CrossRef]

- Jia K, Ionescu RE. Measurement of Bacterial Bioluminescence Intensity and Spectrum: Current Physical Techniques and Principles. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol., vol. 123, 2015, p. 19–45. [CrossRef]

- Ferone M, Gowen A, Fanning S, Scannell AGM. Microbial detection and identification methods: Bench top assays to omics approaches. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020;19:3106–29. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y, Beahm DR, Ionov S, Sarpeshkar R. Measuring and modeling energy and power consumption in living microbial cells with a synthetic ATP reporter. BMC Biol 2021;19:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Perry, JD. A Decade of Development of Chromogenic Culture Media for Clinical Microbiology in an Era of Molecular Diagnostics. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017;30:449–79. [CrossRef]

- Vanhee LME, D’Haese E, Cools I, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Detection and quantification of bacteria and fungi using solid-phase cytometry. NATO Sci Peace Secur Ser A Chem Biol 2010:25–41. [CrossRef]

- Müller V, Sousa JM, Ceylan Koydemir H, Veli M, Tseng D, Cerqueira L, et al. Identification of pathogenic bacteria in complex samples using a smartphone based fluorescence microscope. RSC Adv 2018;8:36493–502. [CrossRef]

- Cody RB, McAlpin CR, Cox CR, Jensen KR, Voorhees KJ. Identification of bacteria by fatty acid profiling with direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2015;29:2007–12. [CrossRef]

- Tiquia-Arashiro S, Li X, Pokhrel K, Kassem A, Abbas L, Coutinho O, et al. Applications of Fourier Transform-Infrared spectroscopy in microbial cell biology and environmental microbiology: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Front Microbiol 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Arbefeville SS, Timbrook TT, Garner CD. Evolving strategies in microbe identification-a comprehensive review of biochemical, MALDI-TOF MS and molecular testing methods. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024;79:2–8. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi H, Horio K, Kato S, Kobori T, Watanabe K, Aki T, et al. Direct detection of mRNA expression in microbial cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization using RNase H-assisted rolling circle amplification. Sci Rep 2020;10:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Trinh TND, Lee NY. Advances in Nucleic Acid Amplification-Based Microfluidic Devices for Clinical Microbial Detection. Chemosensors 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Jeon S, Lim N, Park S, Park M, Kim S. Comparison of PFGE, IS6110-RFLP, and 24-Locus MIRU-VNTR for molecular epidemiologic typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with known epidemic connections. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2018;28:338–46. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad S, Lohiya S, Taksande A, Meshram RJ, Varma A, Vagha K. A Comprehensive Review of Innovative Paradigms in Microbial Detection and Antimicrobial Resistance: Beyond Traditional Cultural Methods. Cureus 2024;16:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Rychert, J. Benefits and Limitations of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for the Identification of Microorganisms. J Infect 2019;2:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Singhal N, Kumar M, Kanaujia PK, Virdi JS. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: An emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front Microbiol 2015;6:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wespel M, Geiss M, Nägele M, Combé S, Reich J, Studts J, et al. The impact of endotoxin masking on the removal of endotoxin during manufacturing of a biopharmaceutical drug product. J Chromatogr A 2022;1671:462995. [CrossRef]

- Schneier M, Razdan S, Miller AM, Briceno ME, Barua S. Current technologies to endotoxin detection and removal for biopharmaceutical purification. Biotechnol Bioeng 2020;117:2588–609. [CrossRef]

- Baker E, Ponder J, Oberdorfer J, Spreitzer I, Bolden J, Marius M, et al. Barriers to the Use of Recombinant Bacterial Endotoxins Test Methods in Parenteral Drug, Vaccine and Device Safety Testing. Altern to Lab Anim 2023;51:401–10. [CrossRef]

- Cundell, T. What Microbial Tests Should be Considered Stability Test Parameters? Am Pharm Rev 2024;26:18–22.

- Jimenez L. Analysis of FDA Enforcement Reports (2012-2019) to Determine the Microbial Diversity in Contaminated Non-Sterile and Sterile Drugs. Am Pharm Rev 2019. https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/518912-Analysis-of-FDA-Enforcement-Reports-2012-2019-to-Determine-the-Microbial-Diversity-in-Contaminated-Non-Sterile-and-Sterile-Drugs/ (accessed February 17, 2025).

- Tavares M, Kozak M, Balola A, Sá-Correia I. Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria: A feared contamination risk in water-based pharmaceutical products. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020;33. [CrossRef]

- Sutton S, Jimenez L. A Review of Reported Recalls Involving Microbiological Control (2004-2011) with Emphasis on FDA Considerations of Objectionable Organisms. Am Pharm Rev 2012. https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/38382-A-Review-of-Reported-Recalls-Involving-Microbiological-Control-2004-2011-with-Emphasis-on-FDA-Considerations-of-Objectionable-Organisms/ (accessed February 17, 2025).

- European product recalls break records for fifth consecutive year in 2023. Sedwick 2024. https://www.sedgwick.com/press-release/european-product-recalls-break-records-for-fifth-consecutive-year-in-2023/?loc=eu.

- European product recalls on track to reach a 10-year high in 2024. Sedwick 2024. https://www.sedgwick.com/en-gb/press-release/european-product-recalls-on-track-to-reach-a-10-year-high-in-2024/?loc=eu (accessed February 17, 2025).

- Sandle, T. Review of FDA warning letters for microbial bioburden issues (2001-2011). Pharma Times 2012;44:29–30.

- Jain SK, Jain RK. Review of fda warning letters to pharmaceuticals: Cause and effect analysis. Res J Pharm Technol 2018;11:3219–26. [CrossRef]

- Hall K, Stewart T, Chang J, Kelly Freeman M. Characteristics of FDA drug recalls: A 30-month analysis. Am J Heal Pharm 2016;73:235–40. [CrossRef]

- Alsulimani A, Akhter N, Jameela F, Ashgar RI, Jawed A, Hassani MA, et al. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Microbial Diagnosis. Microorganisms 2024;12:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Elshafei, AM. Exploring the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Revolutionizing Microbial Diagnostics. Asian J Res Infect Dis 2024;15:79–90. [CrossRef]

- Tsitou VM, Rallis D, Tsekova M, Yanev N. Microbiology in the era of artificial intelligence: transforming medical and pharmaceutical microbiology. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 2024;38. [CrossRef]

- Cheruvari A, Kammara R. Bacteriocins future perspectives: Substitutes to antibiotics. Food Control 2025;168:110834. [CrossRef]

- Darbandi A, Asadi A, Mahdizade Ari M, Ohadi E, Talebi M, Halaj Zadeh M, et al. Bacteriocins: Properties and potential use as antimicrobials. J Clin Lab Anal 2022;36:1–40. [CrossRef]

- Kaleem AM, Koilpillai J, Narayanasamy D. Mastering Quality: Uniting Risk Assessment With Quality by Design (QbD) Principles for Pharmaceutical Excellence. Cureus 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Sangshetti JN, Deshpande M, Zaheer Z, Shinde DB, Arote R. Quality by design approach: Regulatory need. Arab J Chem 2017;10:S3412–25. [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Qual Guidel 2025. https://www.ich.org/ (accessed February 25, 2025).

- Newby, P. The Significance and Detection of VBNC Microorganisms. Am Pharm Rev 2007. https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/113051-The-Significance-and-Detection-of-VBNC-Microorganisms/ (accessed February 27, 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).