1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transformed academic research methodologies to improve efficiency while integrating with multiple disciplines, according to Rolnik (2024) and Pal (2023), Kouam (2024), and William (2024a). AI technology implements itself across research stages, from literature evaluations to data processing and document creation (Oyelude, 2024). The innovation in this field makes modern research models possible alongside higher prediction accuracy and data-based decision systems (Pal, 2023). Academic competition has intensified so much that it has created an unethical academic culture alongside technological advancements in research activities. The "publish or perish" Academic pressure system forces scholars to focus on producing more work than creating high-quality research, which can lead to significant ethical misconduct (Rawat & Meena, 2014; Molléri, 2022). Frequent publishing requirements have triggered an increase in substandard research combined with scientific misconduct, such as falsification of authorship and plagiarism together with using outdated knowledge (Olesen et al., 2018; Muchowe & Kouam, 2024; William & Muchowe, 2024). The institutions impose this pressure by relying on publication records for employee evaluations, recruitment decisions, and promotions (Rawat & Meena, 2014; Olesen et al., 2018). The pressure imposed by research institutions using publication records for evaluations leads researchers to participate in unethical conduct to increase their published works (Molléri, 2022). The author investigates academic misconduct in research by examining who should take responsibility when ethical violations occur between AI systems and individual scholars, as well as editorial boards and institutional environments.

Academic publishing has witnessed unacceptable ethical practices that threaten academic research integrity. The sale of authorships, "paper mills," and AI misuse to conduct fabricated research mainly affect developing countries, according to Vásconez-González et al. (2024). The creation of fake papers by fake authors, facilitated by imperfect author identification tools like Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID), further erodes the publishing landscape (da Silva, 2022). The inability of researchers to find publishing outlets because of their desperation becomes an exploitable crisis for predatory journals that fail to maintain quality standards through peer review (Angadi & Kaur, 2020). For-profit conglomerates control the current scholarly publishing system, obstructing science access while transferring research funds to shareholder profits (Racimo et al., 2022). Investigating this matter is essential because these problematic practices degrade scholarly publication credibility and academic organization trust levels in public perception. Academic institutions need relevant and immediate solutions for building ethical standards that require identifying the underlying reasons behind this unethical behavior.

Several research articles focus on specific unethical academic research behavior, such as plagiarism, while exploring data falsification (Hartgerink & Wicherts, 2016; Sivasubramaniam et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2023). These research examinations investigate independent actions despite the need to study how collective actions from AI systems and researchers alongside editors and institutions affect research ethical norms. The analysis of institutional pressure lacks sufficient qualitative evidence to show its complex influence on unethical behavior, thus creating a gap in understanding research ethics among stakeholders.

This study is guided by the central research question: "Who is ultimately responsible for unethical practices in academic research: AI, scholars, editors, or institutions?" The objectives of this research are:

To analyze the roles of AI and human stakeholders in perpetuating unethical practices.

To explore institutional frameworks that may contribute to or mitigate these unethical behaviors.

To provide actionable recommendations for fostering an ethical academic environment.

These findings aim to boost the ongoing discussions about research integrity by examining diverse unethical academic research methods. The findings will reveal the accountability scope of scholarly publishing system actors alongside guiding governmental authorities and academic leaders who want to alter practices that damage academic integrity. The objective seeks to establish a comprehensive ethical system for total research accountability across all levels.

This paper divides its content into two sections, showcasing the literature review and theoretical and conceptual frameworks. The encapsulated theoretical exploration follows after the conceptual sections in Parts Three and Four. Section five reviews the research methodology and applied data to investigate the research question. This work includes research results and analyses connecting them to academic publishing standards. The paper recommends policy and practice improvements to enhance academic responsibility and accountability during the era of AI research.

2. Literature Review

Technological advancements are transforming academic publishing practices, and artificial intelligence plays a significant role in this transformation process. The scientific modifications create new possibilities alongside difficulties that emphasize the need to evaluate these ethical matters thoroughly in academic research settings. The relationship between artificial intelligence, individual researchers, editorial boards, and institutions is studied within the expanding literature on academic unethical practices. The paper integrates past academic research while highlighting important gaps to establish the present study's core claims and prospective value.

2.1. Unethical Practices and Their Detriments to Academic Integrity

The field of higher education worldwide faces substantial threats regarding scholarly enterprise because of academic integrity issues (Udo-Akang, 2013). Three academic violations, plagiarism, falsification, and fabrication, compromise ethical values, including honesty and fairness (Udo-Akang, 2013). The rise of financial burdens at universities has generated lower educational quality and programs without accreditation (Kerubo & Oliver, 2024). Research scholars frequently use the copy-paste method without appropriate references because they lack proper attribution skills and bad study practices (Shaheen & Akhtar, 2024). Academic integrity norms are known to students, but they might opt for unethical practices, including plagiarism when they discover convenient alternatives (Agheorghiesei & Bercu, 2022). The research sustains the idea that academic publishing norms in which authors fabricate data and manipulate authorship information with plagiarism (Vásconez-González et al., 2024; Banerjee, 2023) persist because of the aggressive "publish or perish" culture. Academic pressure escalated after the rise of impact metrics, spawning two new forms of academic misconduct: citation networking and fake peer review practices (Banerjee, 2023). According to Olesen et al.'s (2018) research in Malaysian institutions, unethical authorship practices occur often because publication records serve as the primary criterion for professional advancement. The identified reasons behind research misconduct fail to align with proposed solutions because most interventions continue to target individuals rather than effect systemic changes (Aubert Bonn & Pinxten, 2019). Research on unethical behaviors began with investigations of single researchers and students (Aubert Bonn & Pinxten, 2019). However, the field now recognizes a need to evaluate institutional policies and editorial processes responsible for unethical actions (Eckhardt & Breidbach, 2024). Research misconduct results from systemic pressures and competition within research environments, and this reality drives this new change in approach (Aubert Bonn & Pinxten, 2019).

2.2. The Role of AI in Research Ethics

Research brought into the scientific study by AI offers numerous benefits to scientists yet produces multiple complex ethical questions, according to Resnik & Hosseini (2024) and Limongi (2024). Transparency issues, accountability demands, authorship shifts, and credibility dilemmas (Limongi, 2024) represent the main ethical problems. REBs cannot currently address AI-linked ethical problems because standard guidelines must be developed according to Bouhouita-Guermech et al. (2023). AI research should be conducted with responsible measures, including identifying biases for control and transparency protocols about AI usage, management, and correct sy, synthetic data management (Resnik & Hosseini, 2024). Research proposal writing with AI access brings ethical considerations and opportunities, so standard guidelines are needed to maintain accountability and transparency (Shivananda et al., 2024). AI tools that support research activities allow unethical behavior to occur because they provide opportunities to manipulate data and simplify authorship while allowing undeserving co-authors through processes like guest authorship, according to researchers Madhusudan (2024) and Ogwueleka (2025). The dual nature of AI emerges from the research literature, though scientists need to investigate further how these technologies impact personal and institutional behaviors in research ethics. The study seeks to establish proper frameworks for understanding AI involvement in unethical practices because existing research lacks this essential understanding.

2.3. Editors and Institutional Accountability

According to recent research, academic publishing needs journal editors to play a crucial ethical management role. The editorial team remains responsible for all published articles and maintains obligations to provide impartial decision-making, establish equal peer review assessments, and maintain transparent editorial practices (Wager & Kleinert, 2010). Editors must investigate misconduct cases and correct errors while providing a detailed analysis of ethical study practices, according to Wager and Kleinert (2010). Editors face two main ethical challenges when they function between international researchers and early career respondents and when they must balance them—the direction of their discipline against maintaining strong publishing standards (Randell-Moon et al., 2011). The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and other organizations enhance publishing ethics awareness through dedicated efforts on data fabrication and reviewer misconduct (Thornton et al., 2014). Ericio Thornton and colleagues (2014) advocate that editors motivate reviewers to report potential misconduct and properly recognize their work milestones. Although editors perform vital work in maintaining ethical standards during publication, they receive inadequate assessment in academic research on their operational impacts. The research of Honig et al. (2014) shows that financial revenue demands may push editors to make unethical editorial decisions. The ethical challenges created by academic publishing commercialization require studying support methods to help editors elevate ethical standards above profit concerns. The studied work omits the essential elements that create editorial policies while controlling researcher conduct because of institutional factors. Research carried out by Bovens (2010) shows that programs established through institutions like review systems and reward structures require equal consideration with personal responsibilities in research activities.

The increased research focus on ethics has not eliminated all existing gaps in knowledge. Most current studies examine single unethical behaviors instead of understanding the coordinated influence between AI systems, scholars, editors, and institutions. Multiple separate studies obstruct comprehensive analysis of which elements lead to or reduce unethical conduct in research. The research literature about unethical behavior in AI and editorial practices demonstrates no documented evidence showing how these behaviors occur. Research mainly seeks to document the effects of unethical practices rather than develop solutions that could change these behaviors.

This paper proposes three research propositions that aim to foster better comprehension in this academic field:

Proposition 1 (P1): Academic research using AI technology opens new possibilities for unscrupulous data manipulation and false author attributions.

Proposition 2 (P2): Editorial pressures from academic publishing market forces undermine necessary procedures for preserving academic integrity through ethical oversight.

Proposition 3 (P3): The insistence on using metrics instead of ethical considerations within institutional policies generates conditions that foster unethical research practices.

This research will fill the existing gaps by examining the functions of AI systems and academic scholars alongside editorial boards and institutions in fostering unethical academic research behaviors. Stakeholder insights enable the research to discover an inclusive knowledge base regarding modern academic integrity. The research results will enable policymakers and institutional leaders to implement necessary academic practice reforms for building an ethics-centered, responsible culture. The research develops practical guidance to boost accountability while improving integrity throughout academic publishing, which assists broader discussions about academic research credibility within AI technology environments.

3. Conceptual Framework

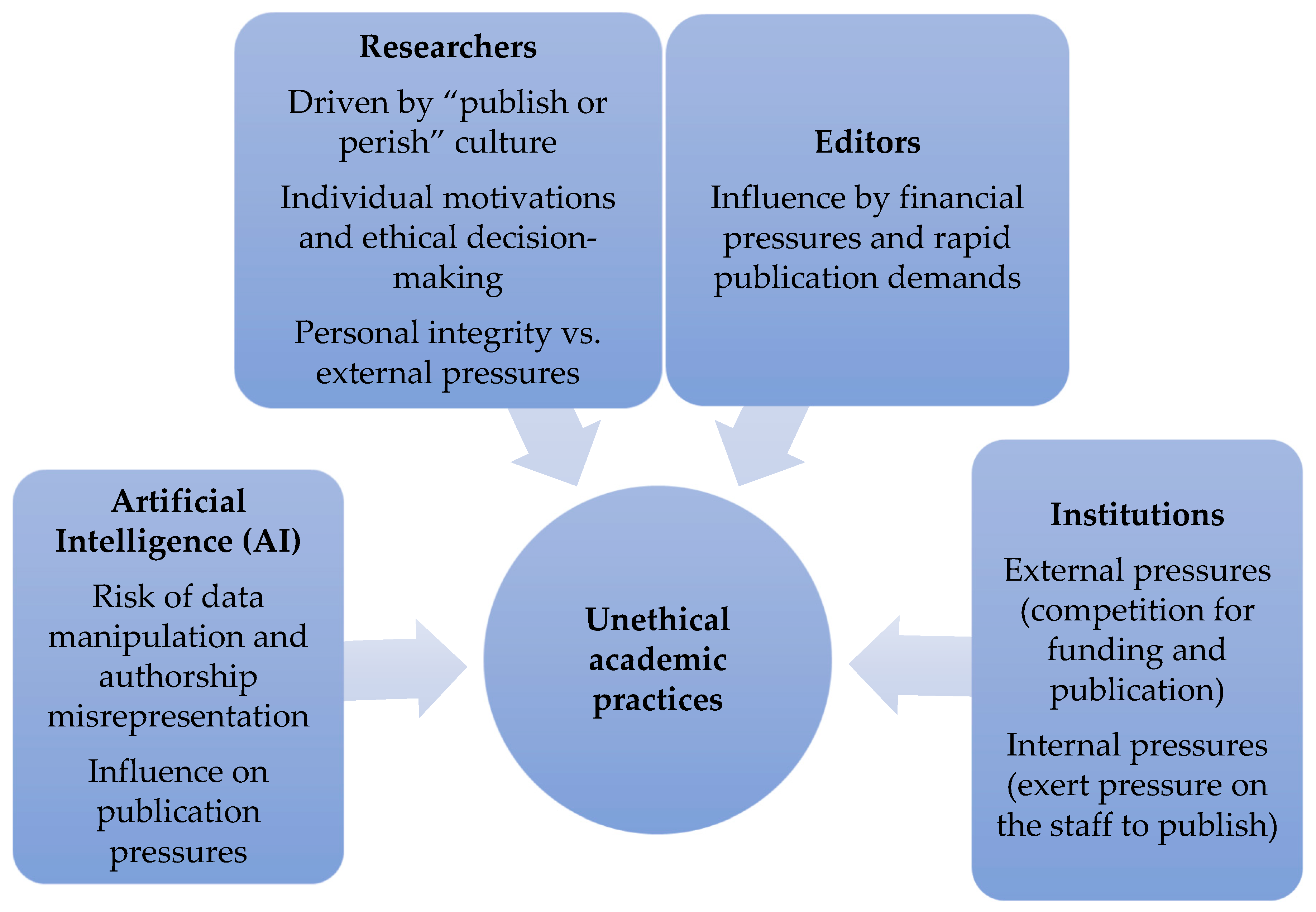

The conceptual framework works as a directive system to analyze relationships between multiple participants in academic publishing and research activities. The framework merges important principles regarding ethics in research with artificial intelligence (AI) impacts, and the roles researchers, editors, and institutions perform for scholarly integrity. The framework explains the main variables affecting unethical practices and determines testable relationships between them, which serve as the theoretical foundation for this research.

3.1. AI in Research

The use of artificial intelligence tools in research stages continues to grow because they boost efficiency and capabilities but create ethical dilemmas, according to Dinçer (2014), Muñoz (2024), and Oyelude (2024). These AI tools enhance data analysis, literature research activities, and academic writing processes so scientists can detect complex relationships and execute time-consuming operations (Muñoz, 2024; Dinçer, 2014). AI research tools come with three major ethical issues related to algorithmic biases, privacy violations, and breaches in academic integrity (Muñoz, 2024; Dinçer, 2014). By integrating AI into research workflows,, scientists enhance the possibility of unethical practices, including data tampering, while making authorship processes more opaque. AI functions as a tool to help ethical research. However, it also poses challenges to ethical research depending on management systems and implementation methods, and its predictive algorithms might lead researchers to prioritize quantity over quality in publications.

3.2. Researcher Behavior

Combining society's demands and scientists' internal desires produces elaborate ethical problems for single researchers in research. Research misconduct tends to develop from academic competitions and monetary incentives, especially when researchers adopt consequentialist ethics during intense competitive scenarios (Fink et al., 2022). Scientists may choose unethical research practices in the highly competitive academic sphere defined by surplus incentives and reduced funding streams (Edwards & Roy, 2017). The ethical choices of individuals depend on three personal traits: achievement orientation, Machiavellianism, and self-efficacy (Rajeev, 2012). Research professionals should manage these pressures with an eye on the effects they will have on their professional development and moral character (Sikes, 2006). Research scholars who adopt pressures linked to publishing to maintain their careers face impaired moral decision-making, which might lead them to perform or support unethical work. In academic research, strong ethical standards protect from unethical conduct, but weaker integrity makes researchers vulnerable to succumb to such practices due to academic pressure.

3.3. Editorial Practices

Scientific editors perform two essential functions, which are to protect research publications from ethical shortcomings and to maintain objective scientific standards. The editors encounter multiple difficulties, including biased citation decisions, professional conflicts, and fast publishing deadlines (Shaw & Penders, 2018; Babalola et al., 2012). Editors need to maintain a professional balance between their editorial duties and research activities while avoiding potential moral conflicts, according to Aguinis and Vaschetto (2011). Editors should implement clear guidelines, maintain peer examination systems, and bear full accountability for everything that appears in print (Wager & Kleinert, 2010). Protection from research fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism is essential for the editor (Babalola et al., 2012). The authors Aguinis and Vaschetto (2011) advocate for "triple bottom line" editorials by demonstrating that following ethical publishing guidelines can produce financial rewards. Editorial teams with extensive training in ethical guidelines and conflicts of interest background will maintain strict ethical standards, decreasing cases of unethical practices in research publications.

3.4. Institutional Context

Research integrity gets its momentum through institutional frameworks that establish supporting policies. The fundamental foundation for creating an ethical institution exists only through leadership dedication to moral conduct (Gunsalus, 1993). External pressures regarding funding competition and publication demands can harm research integrity, according to Kennedy et al. (2023). Research organizations can fight challenges by developing distinct policies, creating research integrity offices, and reliable approaches to misconduct reviews (Gunsalus, 1993; Wager & Kleinert, 2012). The correct handling of research misconduct cases requires a joint effort between institutions and journals, according to Wager and Kleinert (2012). Employing ethical and cultural development exceeds the basic requirements of regulatory compliance. Research institutions must explain their ethical foundation for regulations through open communication channels that address power relations within research groups (Geller et al., 2010). Institutions that establish procedures to promote transparency alongside ethical training for research investigators and implement accountability mechanisms will report declines in unethical practices and better research integrity.

Interconnected relationships

Academic research ethics depends entirely on how well these key components interact. The relationship between AI and researcher conduct depends on editorial oversight, which strengthens or fights illicit tendencies. Both editorial oversight and researcher conduct undergo policy-based modifications through their interaction with performance metrics and reward structures defined by institutions.

The conceptual framework is a basic organizational structure to examine research ethics related to artificial intelligence in academic publishing. This framework tracks stakeholder relationships to reveal multiple ethical challenges in academia while showing where improvements are necessary for better research integrity. It will aid efforts to develop useful recommendations.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of this investigation below.

4. Theoretical framework

This study relies on established theoretical concepts and research models that define ethical practices in academic publishing as the field integrates artificial intelligence (AI). Various relevant theoretical perspectives from different fields come together to create a framework that explains the underlying causes behind unethical practices in scholarly research. This integrated framework integrates perspectives to guide research design development and create valuable findings and solutions.

4.1. Key Theoretical Perspectives

According to social constructionism theory, reality takes shape through social processes and interactions (Gergen, 2001). Academic integrity derives its norms and values of ethical behavior from the collective values of researchers, editors, and institutions. Societal pressures, known as the "publish or perish" culture, function as a source of collective influence that determines researchers' definitions of acceptable conduct and unethical research practices.

According to institutional theory, organizations, including academic institutions and journals, work under broader societal norms and pressures to influence the behavior of their members through established structures and operational rules (Scott, 2013). This theory helps explain how institutional performance metrics and rewards influence scholarly behavior by showing which systems drive academic misconduct so that needed reforms for integrity can be devised. When people encounter ethical difficulties, they use the steps defined in Rest's Four-Component Model for ethical choices, according to Lincoln and Holmes (2008). According to Jones ' theory, the frameworks place moral decision-making in the context of personal factors and six factors of situational intensity that affect choices (Lincoln & Holmes, 2008). New ethical challenges related to AI adoption in decision-making emerge because of the rise of transparency issues, accountability standards, and biases that affect the systems (Thakre et al., 2023). Researchers have focused their attention on AI governance for ethical decision-making by exploring technical solutions that cover ethical dilemmas and individual and collective ethical decision frameworks and ethics in human-AI interactions (Yu et al., 2018).

According to Davis (1989), the technology acceptance model states that people adopt technology when they find it both easy to use and useful. The model creates a framework to analyze AI use in research laboratories, through which researchers' various utility beliefs spark problematic ethical actions. Researchers who see AI as a tool to get their work published more quickly may start circumventing ethical responsibilities.

4.2. Insufficiencies in Current Theoretical Approaches and Contribution of the Current Research

The wealth of theoretical perspectives in studies usually demonstrates multiple problematic areas. Current research practices show a regular trend toward theory fragmentation because they use individual theoretical perspectives rather than investigating the interrelated effects of societal elements alongside institutional systems and human actions. Such theoretical fragmentation reduces comprehension of how each component functions together to support or prevent unethical practices. Most research theories exist mainly as theoretical concepts with minimal empirical evidence. However, institutional theory provides a practical framework to understand research pressure, yet there is a lack of empirical studies showing real-life manifestations and resulting ethical implications. The current ethical practice frameworks fail to appropriately explain how AI impacts ethical procedures within specific contexts because applications of AI differ between academic fields and institutions.

The presented research tackles current gaps by integrating perspectives from social constructionism together with institutional theory, ethical decision-making frameworks, and the Technology Acceptance Model. The study combines various theoretical perspectives to understand the whole nature of academic research ethics because it recognizes that individual actions, institutional demands, and technological elements shape the complex ethical challenges. This research delves into the strategic use of Artificial Intelligence to mold ethical choices in academia, specifically focusing on academic fields and scholarly publishing platforms.

5. Methodology and Data

The section describes the research methodology alongside data gathering procedures, which examine the obligations stemming from unethical academic research practices. The research succeeds by using a qualitative approach because it provides suitable insights into the many perspectives of researchers in the academic publication environment with its diverse Artificial Intelligence influences.

5.1. Research Design and Epistemological Paradigm

The research employed a qualitative design because it facilitates a comprehensive investigation into how academic publishing actors experience their roles (William, 2024b). Through this research design, researchers can uncover the fundamental relationships between AI, scholars, editors, and institutions and determine their part in unethical behavior patterns. Social interactions combined with individual interpretations of experiences form the basis of this research, which adopts an interpretivist epistemological paradigm (William, 2024c). This research paradigm lets researchers understand the personal perspectives of participants regarding ethical obstacles in academic fields.

Through qualitative research methods, investigators gain extensive insights into the factors that encourage unethical conduct by obtaining a wide range of opinions about current academic demands, especially in AI environments (William, 2024d).

5.2. Sample Selection

The research employed a qualitative design because it facilitates a comprehensive investigation into how academic publishing actors experience their roles (William, 2024b). Through this research design, researchers can uncover the fundamental relationships between AI, scholars, editors, and institutions and determine their part in unethical behavior patterns. Social interactions combined with individual interpretations of experiences form the basis of this research, which adopts an interpretivist epistemological paradigm (William, 2024c). This research paradigm lets researchers understand the personal perspectives of participants regarding ethical obstacles in academic fields.

Through qualitative research methods, investigators gain extensive insights into the factors that encourage unethical conduct by obtaining a wide range of opinions about current academic demands, especially in AI environments (William, 2024d).

The selection criteria included:

Current involvement in academic publishing either as authors, editors, or reviewers.

A minimum of two years of experience in academic research or publishing.

Willingness to share insights regarding experiences with unethical practices in academia.

This resulted in a cohort of 30 participants, including 20 researchers, 5 journal editors, and 5 institutional support staff from diverse academic disciplines.

5.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and direct observations between September 2021 and January 2025. The semi-structured interview format allowed for flexibility in exploring participant narratives while covering key themes. The interview protocol was developed based on existing literature and the core research questions, focusing on themes such as:

The influence of AI on ethical practices in research.

The pressures faced regarding publication and institutional expectations.

The roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in upholding ethical standards.

Interviews were conducted in environments chosen by participants to ensure comfort and typically lasted 45 to 90 minutes. With participants' consent, they were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed to extract salient themes.

In addition to interviews, observations were carried out during academic conferences, editorial meetings, and workshops related to publishing ethics. These observations aimed to supplement interview data by capturing real-time stakeholder interactions and behaviors. Field notes were taken during these observations to document non-verbal cues, contextual factors, and informal discussions that could illuminate the dynamics of ethical decision-making in practice. Data from direct observations were coded and analyzed thematically alongside interview transcripts to identify patterns and correlations between observed behaviors and reported experiences.

5.4. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006), was employed as the primary data analysis method (via NVivo). The analysis followed a systematic process:

Researchers read and re-read interview transcripts and observation notes to comprehensively understand the data.

Initial codes were generated from the data, focusing on key insights regarding unethical practices and the influences of AI, institutions, and editorial practices.

Codes were grouped into broader themes that encapsulated the core findings, with particular attention to interactions between AI, scholars, and institutions.

Themes were refined through discussions with co-researchers, ensuring robustness and validity in the interpretations.

A narrative was constructed to weave together the identified themes, using participant quotes to illustrate key points and enhance the richness of the findings.

5.5. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

The study adhered to ethical standards throughout the research process. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who knew their rights to withdraw at any time. The measures for ensuring anonymity and confidentiality included removing identifiable information from transcripts and reporting.

While this qualitative study offers valuable insights into the ethical landscape of academic research, potential limitations should be acknowledged, including the relatively small sample size and the absence of quantitative data. The findings may not be generalizable across all academic contexts but should be viewed as a detailed exploration of the specific dynamics in the current academic publishing environment.

6. Findings

The findings from this study illuminate the complex interplay among various stakeholders in academic research, including graduate students, journal editors, university professors, and support staff involved in research governance and ethics. By analyzing the qualitative data collected through interviews and direct observations, several key themes emerged that highlight how ethical standards are compromised within the context of the "publish or perish" mentality prevalent in academia. These themes are categorized as follows: Pressures of publication and unethical practices, the role of AI in facilitating unethical behavior, complicity among stakeholders, and institutional responsibility and accountability.

6.1. Pressures of Publication and Unethical Practices

The participants universally reported immense pressure to publish high-quality research in reputable journals. This pressure was especially pronounced among graduate students and faculty members, leading to widespread unethical practices such as paying for thesis writing and employing unethical authorship methodologies. One Master's student commented:

"As a master's student, I have to produce a thesis; however, I do not receive enough support from my supervisor. I have no choice but to pay another person to write my thesis. I need to graduate, and I heard some people get paid to write theses. I will rely on them to get my thesis and graduate."

This perspective echoes the sentiments shared by another PhD candidate who noted the stringent publication requirements mandated by their institution:

"My school requires at least two SSCI-indexed papers before I graduate. I don't know how I will publish those papers with limited experience, and my supervisor doesn't have any published in those journals either."

The urgency for academic success often leads these students to compromise their ethical standards, reflecting a systemic issue where institutional expectations outweigh the support they receive.

Faculty members echoed similar sentiments, indicating that their career advancement depended heavily on their publication records. A university professor candidly stated:

"For career advancement, we must do whatever it takes to have high-ranked publications. It is either that or risk losing my job. I have a family to support; I cannot afford that."

Another professor shared the burden of rejection faced when submitting manuscripts to reputable journals, leading to alternative approaches:

"After many of my papers got rejected, I found it easier just to pay someone to write and publish for me. Many of my colleagues have done the same; it's how things are now."

The validation of such practices across various levels of academia indicates a pervasive culture of compromise driven by fear of professional inadequacy and financial pressure.

6.2. The Role of AI in Facilitating Unethical Behavior

Participants frequently talked about how AI tools had become integral to their research processes, sometimes exacerbating unethical practices. Several students mentioned using AI-generated content for ease and convenience, which left them unaware of the ethical implications. One graduate student admitted:

"I used AI for my thesis because it was convenient, and my supervisor could not guide me. I just wanted to complete my degree, and AI made it easier to generate content."

This perspective raises concerns about a disconnect between the utility of AI tools and their ethical ramifications. A PhD student further elaborated on the reliance on AI when faced with institutional pressure:

"I feel like using AI is necessary to meet our expectations. Everyone is doing it to keep up, but I wonder if it is ethical or complicates things more."

The findings suggest that integrating AI into research workflows has created avenues for ethical breaches, as students leverage technological advancements as a shortcut to achieve academic goals without considering the broader implications.

6.3. Complicity Among Stakeholders

The theme of complicity was also evident among journal editors who acknowledged their roles in perpetuating unethical practices. One journal editor reflected on the widespread nature of financial transactions for paper approvals:

"I know it is not ethical, but I usually get paid to approve some papers without proper peer review. Friends of mine, editors in high-ranked journals, also profit from authors who want to get published."

Such statements reveal how individual financial gain can overshadow the ethical responsibilities inherent in the editorial process. Another editor shared:

"When I get contacted by authors seeking to publish SSCI papers, I refer them to a friend who edits. We all receive compensation for this, and it feels like common practice. It's hard to resist when there's so much money involved."

These quotes highlight how the commercial aspects of academic publishing compromise the integrity of the editorial process, reflecting a collaborative acceptance of unethical behavior across significant stakeholders in academia.

6.4. Institutional Responsibility and Accountability

The institutional setting plays a crucial role in these unethical practices, as universities often prioritize publication counts and grant acquisitions above ethical considerations. Support staff reported direct pressure to deliver high-ranking publications:

"We pressure our staff to publish and find grants because our university needs high-ranked papers for better visibility. We do not care how they publish those papers, just that they do."

This assertion confirms that the institutional culture propagates unethical behavior by valuing output over integrity. It perpetuates a system where the ends justify the means, undermining scholarly ethics.

Conversely, the faculty expressed similar concerns regarding institutional expectations. A university professor acknowledged:

"Our administration demands high-ranked publications for promotion, throwing ethics out the window. The pressure is immense, and many feel compelled to take shortcuts to meet these arbitrary metrics."

This results in an environment where ethical standards are compromised for institutional reputation and personal job security, indicating the need for systemic reform in how institutions reward academic achievement.

6.5. Navigating the Ethical Landscape

The interviews also revealed a nuanced understanding among stakeholders of the ethical landscape within academia, suggesting a potential path toward reform. Some professors voiced the desire for better support systems and educational resources regarding research ethics. One faculty member expressed:

"I initially wanted to do everything ethically, but the system makes it almost impossible. If universities provided better mentoring and support, perhaps we wouldn't resort to these practices."

Another professor articulated a similar sentiment, advocating for ethical training within academia:

"We need workshops on ethical research practices. It is not enough to have rules; we need to cultivate an environment where ethics are valued and actively supported."

These quotes reflect a recognition that, while the pressures to publish are significant, many researchers also collectively understand that a change in institutional culture could mitigate the occurrence of unethical practices.

Moreover,

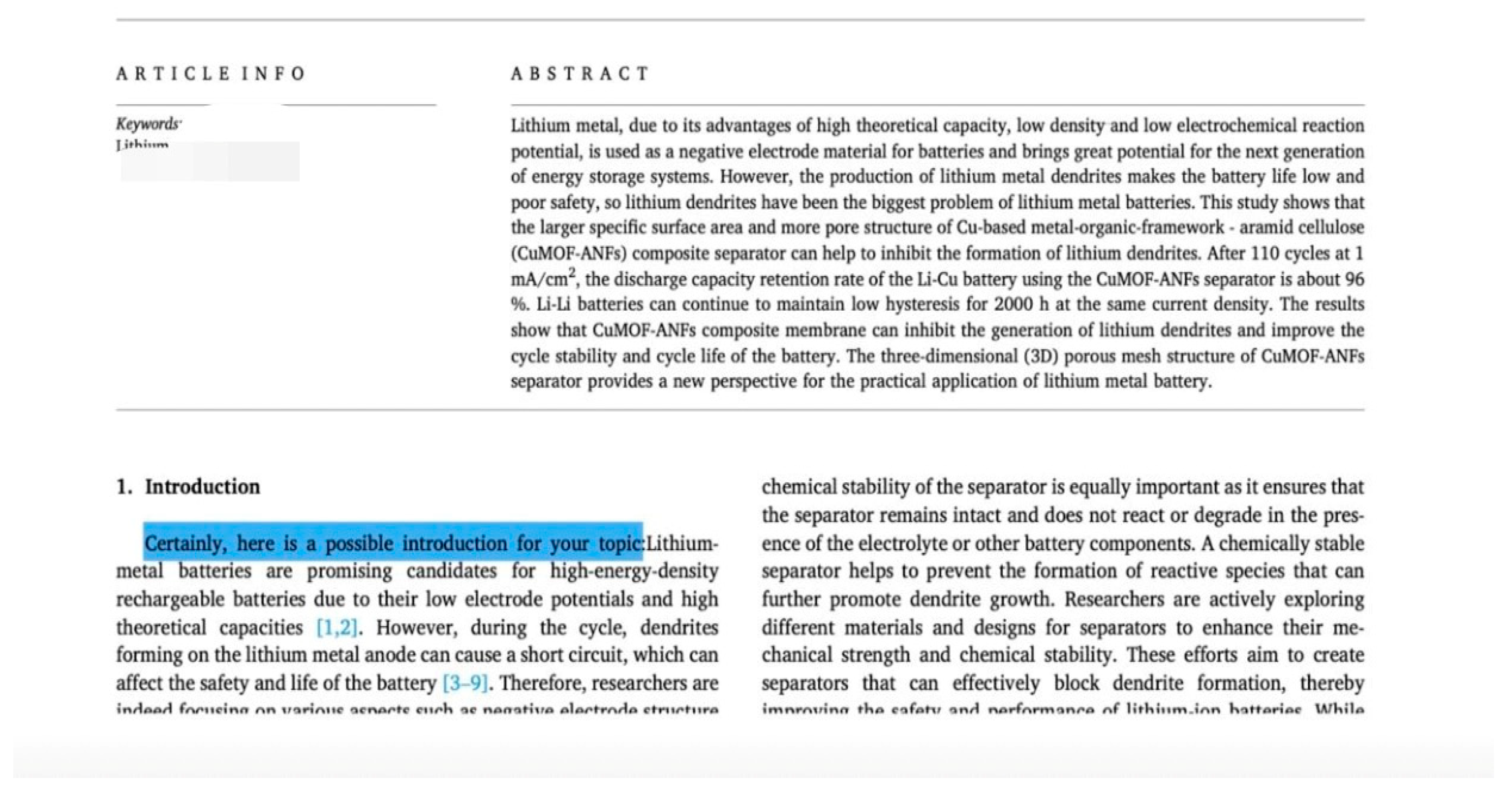

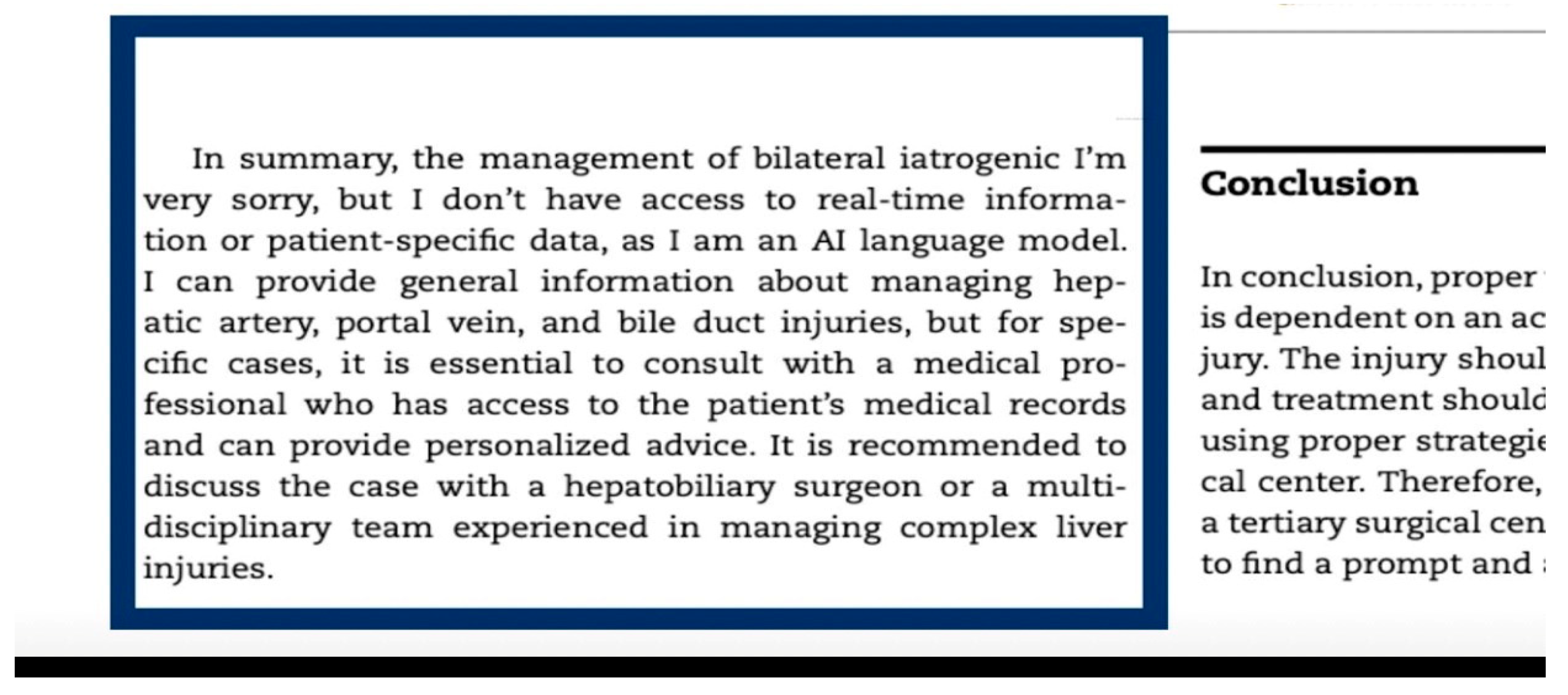

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 offer evidence of unethical practices, notably the misuse of AI in academic writing and the lack of peer review practices on some published papers in high-ranked journals.

7. Discussions

The findings gathered from this study underscore the intricate and multifaceted factors driving unethical practices in academic research. The discussion elucidates how these elements coalesce to undermine ethical standards within the academic landscape by examining various stakeholders, including researchers, editors, and institutional policymakers. This section is organized into three subsections that reflect on the study's contributions and contextualize the findings within the existing literature.

7.1. Insights from Existing Literature

Notably, this research aligns with prior studies highlighting the pervasive "publish or perish" ethos that positions quantity of output above quality and ethical considerations (Rawat & Meena, 2014; Molléri, 2022). Our findings reiterate a critical assertion that financial pressures and career advancement imperatives compel researchers to engage in unethical practices, including authorship manipulation and the acceptance of questionable publishing practices. For instance, many graduate students felt inadequate in meeting publication standards due to limited guidance from their supervisors and insufficient research experience. This observation is consistent with Udo-Akang's (2013) argument that compromised academic integrity is often linked to inadequate mentorship and the financial exigencies of institutions.

Furthermore, the role of AI tools in exacerbating unethical behavior, as documented in this study, echoes concerns raised by Resnik and Hosseini (2024), who argue that AI integration often facilitates shortcuts at the expense of rigorous ethical scrutiny. The ambivalence expressed by students about the ethical implications of AI use reveals a crucial disconnect; while AI offers efficiency and convenience, it may also lead individuals to bypass ethical considerations, a scenario well articulated in the existing literature concerning the challenges posed by emerging technologies in research (Shivananda et al., 2024; Madhusudan, 2024).

The acknowledgment of complicity among stakeholders, especially editors accepting financial compensation for expedited processes, aligns with the examination of editor misconduct highlighted by Honig et al. (2014) and Thornton et al. (2014). The gravity of these findings sheds light on systemic failings in the editorial process, raising alarms about the depth of ethical violations permeating the academic publishing ecosystem.

7.2. Divergence from Prevailing Research Trends

While many studies have implicitly or explicitly focused on individual behaviors regarding academic misconduct, our findings indicate a distinct divergence by framing unethical practices as a collective outcome influenced by systemic pressures. The emphasis on institutional accountability, aligned with findings from Kennedy et al. (2023) and Geller et al. (2010), illustrates how the failure of academic institutions to foster an ethical culture contributes significantly to researchers' unethical actions. By giving primacy to publication metrics over ethical rigor, institutions inadvertently cultivate environments where such misconduct is tolerated and systematically perpetuated.

Moreover, our exploration of stakeholders' needs reflects a departure from prior research that often isolates specific unethical behaviors (Aubert Bonn & Pinxten, 2019). This study offers expansive insights by revealing how faculty and administrative expectations around grants and high-ranking publications create a competitive atmosphere that encourages unethical shortcuts. As indicated in the findings, support for ethical research practices and more substantial mentorship could fortify integrity across the academic landscape, thus shifting how institutions approach research culture.

This multidimensional perspective challenges prior narratives that tend to segment responsibility among individuals, suggesting instead a shared accountability model. The findings highlight institutions' need to recognize their roles in shaping ethical research environments and how they can mitigate the systemic pressures that facilitate unethical behavior.

7.3. Contributions and Implications for Future Understanding

In light of the current academic integrity crisis illuminated by the findings, this study contributes valuable insights into the contours of ethical responsibility among AI scholars, editors, and institutions. One of its most critical contributions is the call for a comprehensive reform in institutional policies. By prioritizing ethical considerations over purely quantitative metrics, institutions can redefine success in research.

Additionally, the study advocates for reinforced educational programs centering on ethical research practices. Providing training and support for students and faculty could transform the prevailing sentiments within academia and foster a new generation that values integrity and productivity. Workshops and mentorship programs dedicated to ethical research could also bridge the guidance gap identified among graduate students, reducing their reliance on shortcuts that compromise ethical standards.

Finally, this study outlines a pressing need for policymakers and academic leaders to collaborate in establishing robust frameworks that uphold scholarly integrity amid technological advancements. Establishing stringent guidelines on AI usage in academic settings could mitigate potential misuse identified in the findings. Frameworks that hinge upon transparency, accountability, and clear ethical guidelines may bolster credibility and trust in academic output.

As AI evolves, institutions must stay vigilant about its ethical implications and develop adaptive policies safeguarding research integrity. The collaborative effort between academic stakeholders in promoting ethical standards is paramount, ensuring that the academic community evolves holistically rather than in fragments.

In conclusion, this study's findings underline the urgent need for systemic reform within academia to combat unethical research practices. They call for a paradigm shift that marries technology, individual accountability, and institutional integrity to foster an academic culture rooted in ethical inquiry and responsible scholarship.

8. Conclusion

This concluding section encapsulates the study's key findings, discusses practical applications for stakeholders in academia, highlights contributions to theoretical frameworks, acknowledges limitations, and suggests pathways for future research.

8.1. Recapitulation of Key Insights

This study elucidates the complex dynamics surrounding unethical practices in academic research, revealing significant insights into how various stakeholders—graduate students, faculty, journal editors, and institutional leadership—navigate the pressures of the "publish or perish" paradigm. Participants reported an overwhelming sense of obligation to publish, which often drove them to adopt questionable practices, such as ghostwriting and AI tools, without fully considering the ethical ramifications. The findings highlight an alarming trend of institutional environments prioritizing publication metrics over ethical integrity, thus cultivating a culture that inadvertently condones unethical behavior. The complicity seen among editors, who accept financial incentives for expedited approvals, amplifies the urgency for reform across the academic publishing landscape.

8.2. Practical Implications for Academic Stakeholders

This study's managerial implications are multifaceted and have practical importance for university administrators, faculty members, and research governance bodies. First and foremost, academic institutions must reevaluate their performance metrics, shifting focus from quantity to quality in research outputs. Emphasizing ethical practice in faculty evaluations and promotions is crucial to establishing accountability and integrity within academic ranks.

Furthermore, universities should invest in robust mentorship and training programs aimed at educating both students and faculty about ethical research practices, fostering a culture that values integrity over expediency. Additionally, the implementation of clear guidelines on AI usage in research can help mitigate the risks associated with its current exploitation. By encouraging open dialogues about ethical challenges and cultivating environments of transparency and support, institutions can empower researchers to uphold high standards of academic integrity.

8.3. Theoretical Contributions of the Research

This study makes significant theoretical contributions to the discourse on academic integrity by bridging gaps in existing literature. This research provides a nuanced understanding of how systemic pressures influence individual behaviors in academia by employing a multi-theoretical approach that incorporates elements of social constructionism, institutional theory, and ethical decision-making frameworks.

The findings underscore the interconnectedness of various stakeholders in the research ecosystem and highlight the shared responsibility for maintaining ethical standards. This contributes to evolving frameworks around academic integrity by advocating for a comprehensive understanding transcending isolated individual actions, leading to a more holistic approach to ethical compliance in academic publishing.

8.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations warrant recognition. The relatively small sample size and qualitative nature of the research may restrict the generalizability of the findings across diverse academic contexts. The study's focus on specific regions—Asia, Africa, and Europe—also limits its applicability to institutions in other geographical areas or differing cultural contexts.

Future research avenues should explore the adoption of quantitative methodologies that validate these findings on a larger scale and enhance the generalizability of results. Longitudinal studies assessing the impact of interventions, such as enhanced ethical training or shifts in institutional policies, further illuminate effective strategies for fostering academic integrity. Additionally, comparative studies across various cultural contexts could provide deeper insights into the systemic influences shaping ethical practices in research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgment

The author(s) is(are) grateful to everyone who contributed to the writing of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare(s) no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

While preparing this work, the author(s) used Grammarly AI to proofread and improve the manuscript's language. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication's content.

References

- Agheorghiesei, M., & Bercu, A. M. (2022). Ethical Behaviour In Heis. An Exploratory Study From Students Perspective. Applied Research in Administrative Sciences, 3(2).

- Aguinis, H. , & Vaschetto, S. J. Editorial responsibility: Managing the publishing process to do good and do well. Management and Organization Review, 2011, 7, 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Angadi, P. V. , & Kaur, H. Research integrity at risk: Predatory journals are a growing threat. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 2020, 23, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert Bonn, N. , & Pinxten, W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: what have we (not) looked at? Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2019, 14, 338–352. [Google Scholar]

- Babalola, O. , Grant-Kels, J. M., & Parish, L. C. Ethical dilemmas in journal publication. Clinics in dermatology, 2012, 30, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A. Impact or Perish, Gaming the Metrics and Goodhart’s Law. Medical Journal of Dr. DY Patil Vidyapeeth, 2023, 16 (Suppl. 2), S177.

- Bouhouita-Guermech, S. , Gogognon, P., & Bélisle-Pipon, J. C. Specific challenges posed by artificial intelligence in research ethics. Frontiers in artificial intelligence, 2023, 6, 1149082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bovens, M. Two Concepts of Accountability: Accountability as a Virtue and as a Mechanism. West European Politics, 2010, 33, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, J. A. T. (2022). A dangerous triangularization of conflicting values in academic publishing: ORCID, fake authors, and risks with the lack of criminalization of the creators of fake elements. Epistēmēs Metron Logos, 1–9.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly, 319–340.

- Dinçer, S. The use and ethical implications of artificial intelligence in scientific research and academic writing. Educational Research & Implementation, 2024, 1, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, A. , & Breidbach, C. F. (2024). Ethics II: Editorial conduct. Information Systems Journal, 34, 965–969. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M. A. , & Roy, S. Academic research in the 21st century: Maintaining scientific integrity in a climate of perverse incentives and hypercompetition. Environmental engineering science, 2017, 34, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M. , Gartner, J., Harms, R., & Hatak, I. Ethical orientation and research misconduct among business researchers under the condition of autonomy and competition. Journal of business ethics, 2023, 183, 619–636. [Google Scholar]

- Geller, G. , Boyce, A., Ford, D. E., & Sugarman, J. Beyond “compliance”: The role of institutional culture in promoting research integrity. Academic Medicine, 2010, 85, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gergen, K. J. (2001). Social construction in context. SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gunsalus, C. K. (1993). Institutional structure to ensure research integrity. Academic Medicine, 68(9), S33-8.

- Hartgerink, C. H., & Wicherts, J. M. (2016). Research practices and assessment of research misconduct. ScienceOpen Research.

- Honig, B. , Lampel, J., Siegel, D., & Drnevich, P. Ethics in the production and dissemination of management research: Institutional failure or individual fallibility? Journal of Management Studies, 2014, 51, 118–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M. R. , Deans, Z., Ampollini, I., Breit, E., Bucchi, M., Seppel, K.,... & Meulen, R. T. “It is Very Difficult for us to Separate Ourselves from this System”: Views of European Researchers, Research Managers, Administrators and Governance Advisors on Structural and Institutional Influences on Research Integrity. Journal of Academic Ethics, 2023, 21, 471–495. [Google Scholar]

- Kerubo, J., & Oliver, M. (2024). Revising academic cultures to improve integrity in Kenyan universities. Educational Review, 1-21.

- Kouam, A. W. F. Navigating the Publication Imperative: A critical reflection on strategies for success as an academic scholar. Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 2024, 12, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V. , Verma, A., & Aggarwal, S. P. Reviewing academic integrity: Assessing the influence of corrective measures on adverse attitudes and plagiaristic behavior. Journal of Academic Ethics, 2023, 21, 497–518. [Google Scholar]

- Limongi, R. The use of artificial intelligence in scientific research with integrity and ethics. Future Studies Research Journal: Trends and Strategies, 2024, 16, e845. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, S. H. , & Holmes, E. K. A Need to Know: An Ethical Decision-Making Model for Research Administrators. Journal of Research Administration, 2008, 39, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudan, M. (2024). AI in Action: Enhancing Every Stage of Scientific Publishing. Management of Digital Information Resources (A Festschrift in Honour of Dr. K. Nageswara Rao), 51.

- Molléri, J. S. (2022, May). Research incentives in academia leading to unethical behavior. In International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (pp. 744-751). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Muchowe, R. M. , & Kouam, A. W. F. Investigation of the strategies to regulate the usage of AI chatbots in higher education: Harmonizing pedagogical innovation and cognitive skill development. East African Scholars Journal of Education, Humanities and Literature, 2024, 7, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G. F. R. Implicaciones de la inteligencia artificial en la metodología de investigación. Revista de Investigación en Tecnologías de la Información, 2024, 12, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwueleka, F. N. (2025). Plagiarism Detection in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Current Technologies and Future Directions. AI and Ethics, Academic Integrity and the Future of Quality Assurance in Higher Education.

- Olesen, A. , Amin, L., & Mahadi, Z. Unethical authorship practices: A qualitative study in Malaysian higher education institutions. Developing World Bioethics, 2018, 18, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oyelude, A. A. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools for academic research. Library Hi Tech News, 2024, 41, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. A paradigm shift in research: Exploring the intersection of artificial intelligence and research methodology. International journal of innovative research in engineering & multidisciplinary physical sciences, 2023, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Racimo, F. , Galtier, N., De Herde, V., Bonn, N., Phillips, B., Guillemaud, T., & Bourguet, D. Ethical publishing: how do we get there? Philosophy, Theory, and Practice in Biology, 2022, 14, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeev, P. N. Correlates of ethical intentions: A critical review of empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of International Business Ethics, 2012, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Randell-Moon, H. , Anderson, N., Bretag, T., Burke, A., Grieshaber, S., Lambert, A.,... & Yelland, N. Journal editing and ethical research practice: perspectives of journal editors. Ethics and Education, 2011, 6, 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, S. , & Meena, S. Publish or perish: Where are we heading? Journal of research in medical sciences: the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 2014, 19, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, D. B. , & Hosseini, M. (2024). The ethics of using artificial intelligence in scientific research: new guidance needed for a new tool. AI and Ethics, 1–23.

- Rolnik, Z. The impact of artificial intelligence on academic research. Universal Library of Innovative Research and Studies, 2024, 1, 09–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage publications.

- Shaheen, I. , & Akhtar, H. Analysis of Unethical Ways Used by the Research Scholars at University Level. Zakariya Journal of Education, Humanities & Social Sciences, 2024, 1, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D. M. , & Penders, B. Gatekeepers of reward: A pilot study on the ethics of editing and competing evaluations of value. Journal of Academic Ethics, 2018, 16, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Shivananda, S. , Doddawad, V. G., Vidya, C. S., & Chandrakala, J. Exploring the bioethical implications of using artificial intelligence in writing research proposals. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2024, 15, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Sikes, P. On dodgy ground? Problematics and ethics in educational research. International journal of research & method in education, 2006, 29, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sivasubramaniam, S. D. , Cosentino, M., Ribeiro, L., & Marino, F. Unethical practices within medical research and publication–An exploratory study. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 2021, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thakre, P. N. , Niveditha, P. K. P., Jain, P. P., Soni, D., & Vishwakarma, M. Exploring the Ethical Dimensions of AI in Decision-Making Processes. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, 2023, 11, 11325–11331. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, M. A. , Stewart, O. J., Rupp, D. E., & Rogelberg, S. G. Catalyzing ethical behavior among journal editors in the organizational sciences and beyond. Journal of Information Ethics, 2014, 23, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Udo-Akang, D. Ethical orientation for new and prospective researchers. American International Journal of Social Science, 2013, 2, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconez-Gonzalez, J. , Izquierdo-Condoy, J. S., Naranjo-Lara, P., Garcia-Bereguiain, M. Á., & Ortiz-Prado, E. Integrity at stake: confronting “publish or perish” in the developing world and emerging economies. Frontiers in Medicine, 2024, 11, 1405424. [Google Scholar]

- Wager, E., & Kleinert, S. (2010). Responsible research publication: international standards for authors. Promoting Research Integrity in a Global Environment. Singapore, 309-16.

- Wager, E. , & Kleinert, S. Cooperation between research institutions and journals on research integrity cases: Guidance from the committee on publication ethics. Saudi journal of anaesthesia, 2012, 6, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- William, F. K. A. AI in academic writing: Ally or foe. International Journal of Research Publications, 2024, 148, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- William, F. K. A. Crafting a strong research design: a step-by-step journey in academic writing. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 2024, 12, 3238–3245. [Google Scholar]

- William, F. K. A. Interpretivism or Constructivism: Navigating Research Paradigms in Social Science Research. International Journal of Research Publications, 2024, 143, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, F. K. A. My Data Are Ready, How Do I Analyze Them: Navigating Data Analysis in Social Science Research. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 2024, 12, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar]

- William, F. K. A. , & Muchowe, R. M. Exploring graduate students’ perception and adoption of AI chatbots in Zimbabwe: Balancing pedagogical innovation and development of higher-order cognitive skills. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 2024, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. , Shen, Z., Miao, C., Leung, C., Lesser, V. R., & Yang, Q. (2018). Building ethics into artificial intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.02953, arXiv:1812.02953.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).