Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection from Urban Green Spaces

2.2. Study Area Details

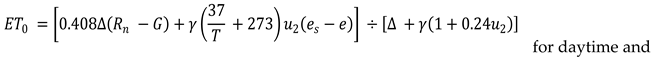

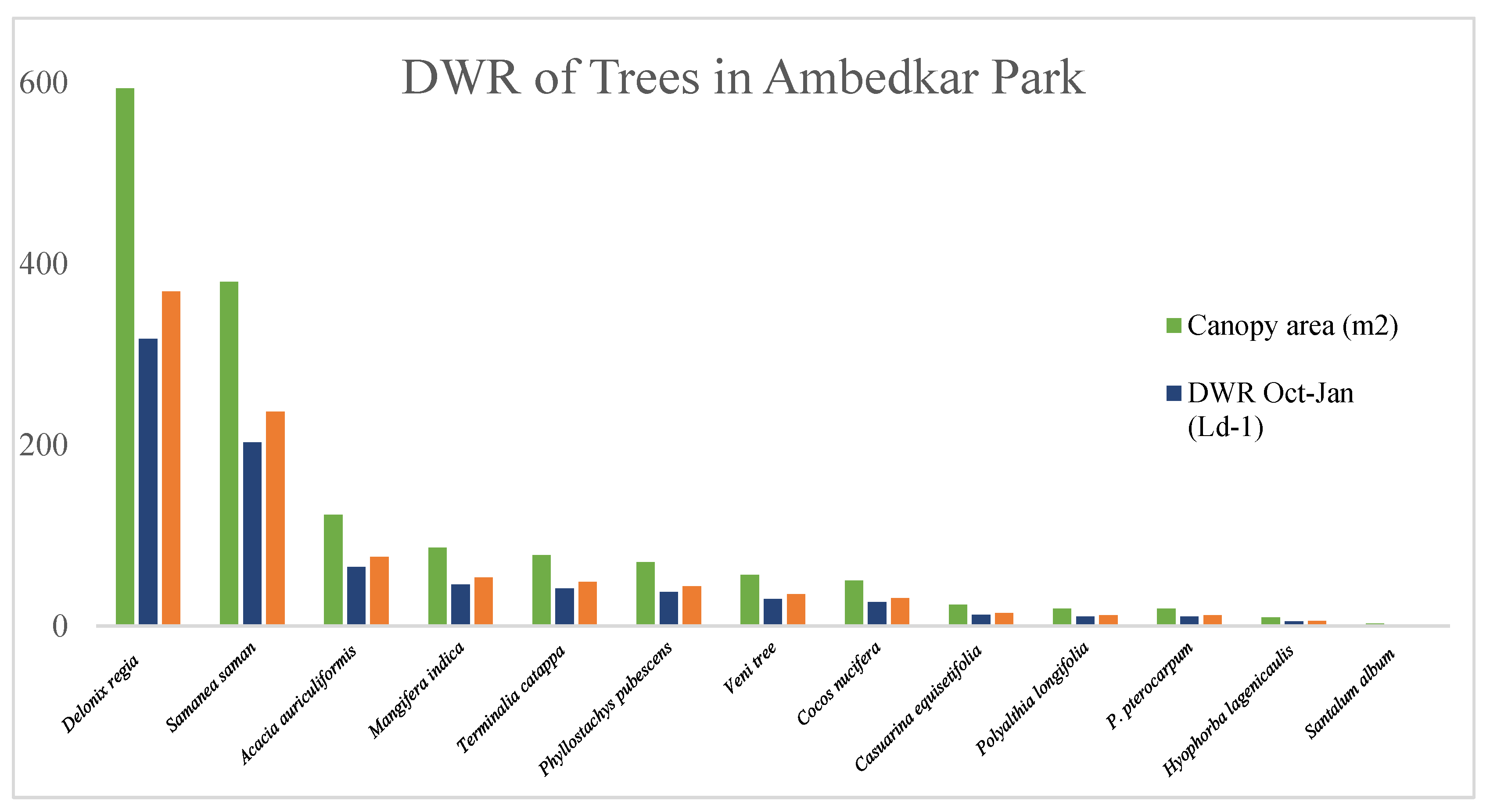

2.3. Derivation of ETo for Panaji Region

2.4. Calculation of Water Requirements of Trees

2.5. Calculation of Water Requirements of Hedge Plants

2.6. Calculation of Water Requirements of Lawns (=Groundcover)

3. Results

3.1. Determination of Evapotranspiration Rates

3.2. Daily Water Requirements (DWR) of Lawn and Groundcover

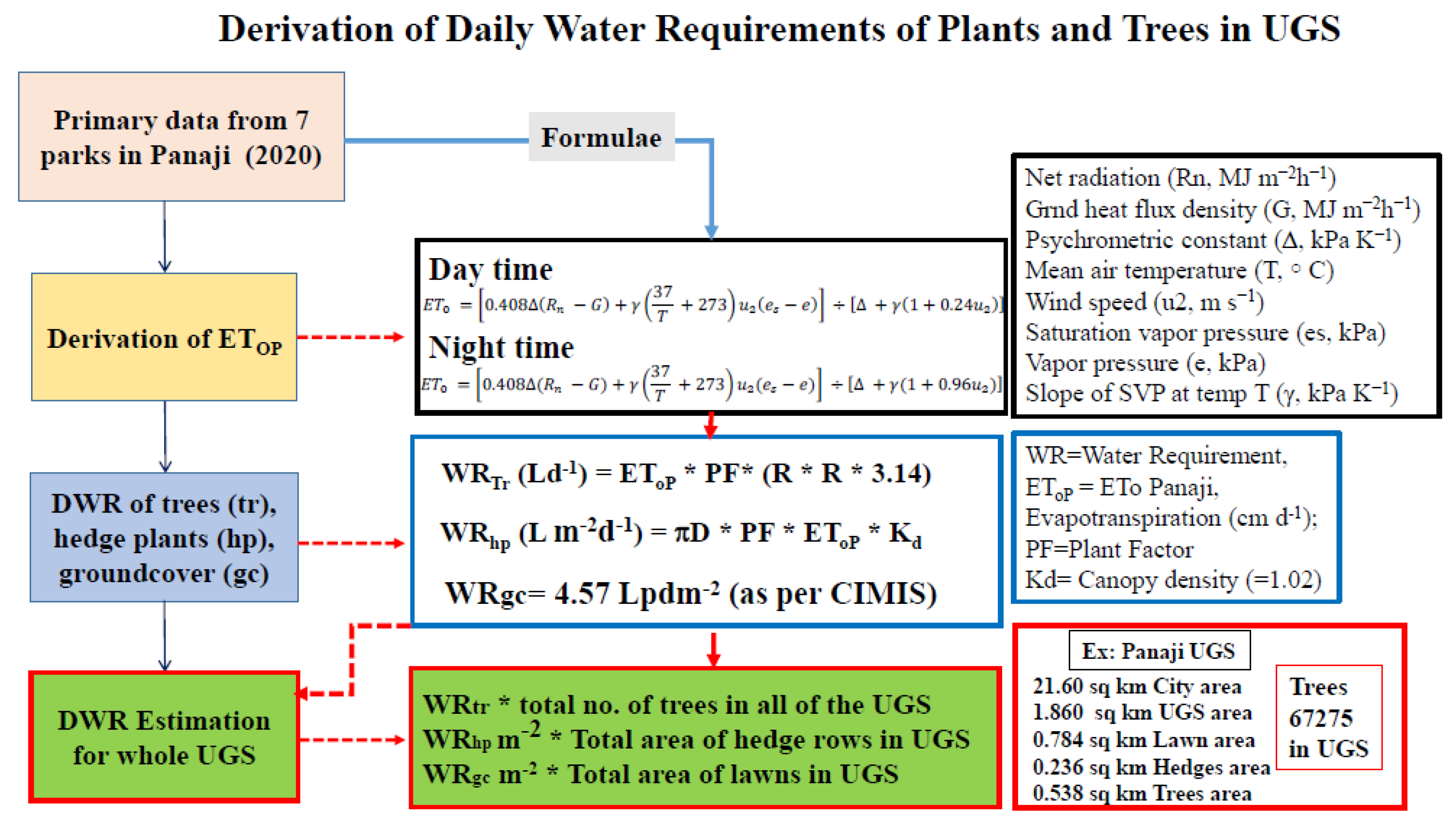

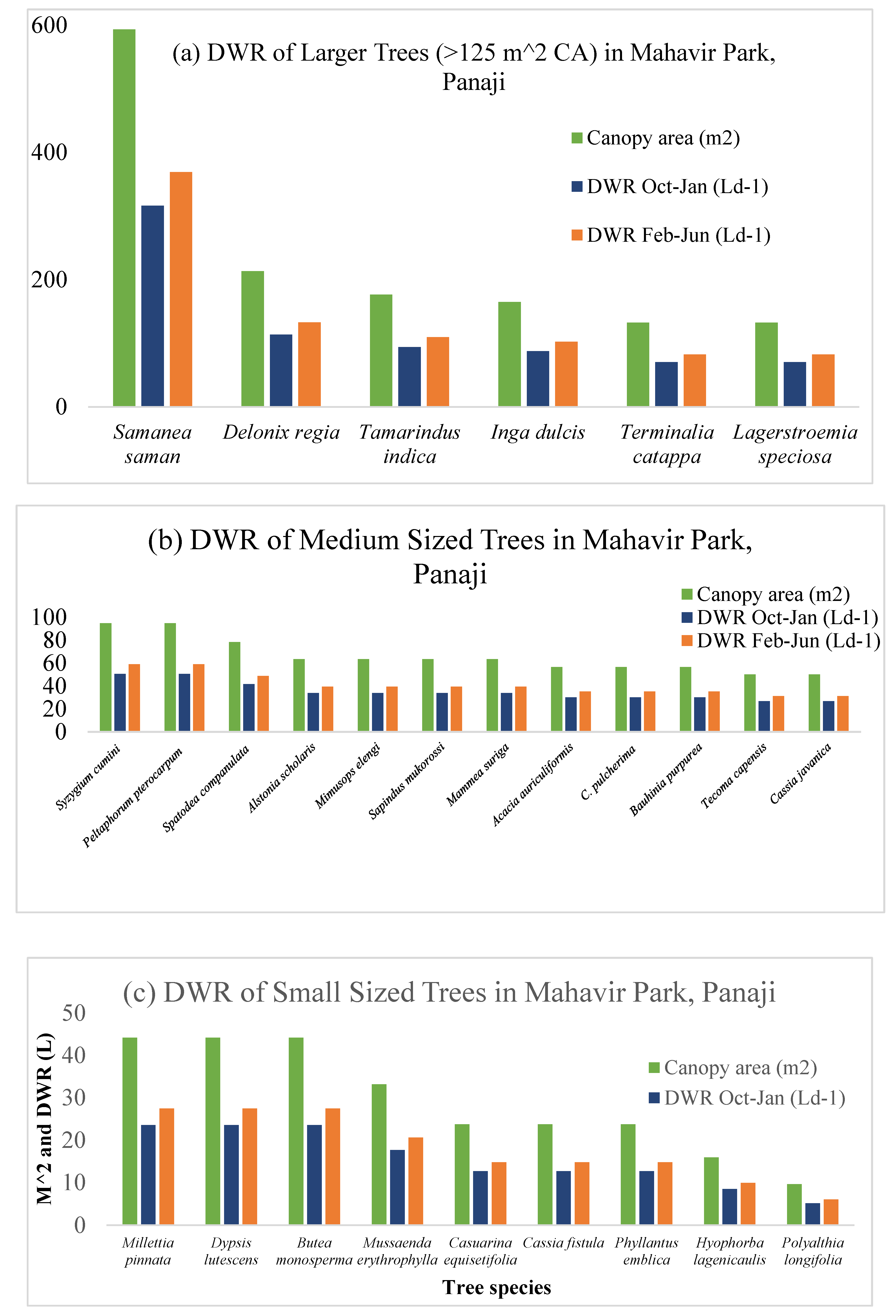

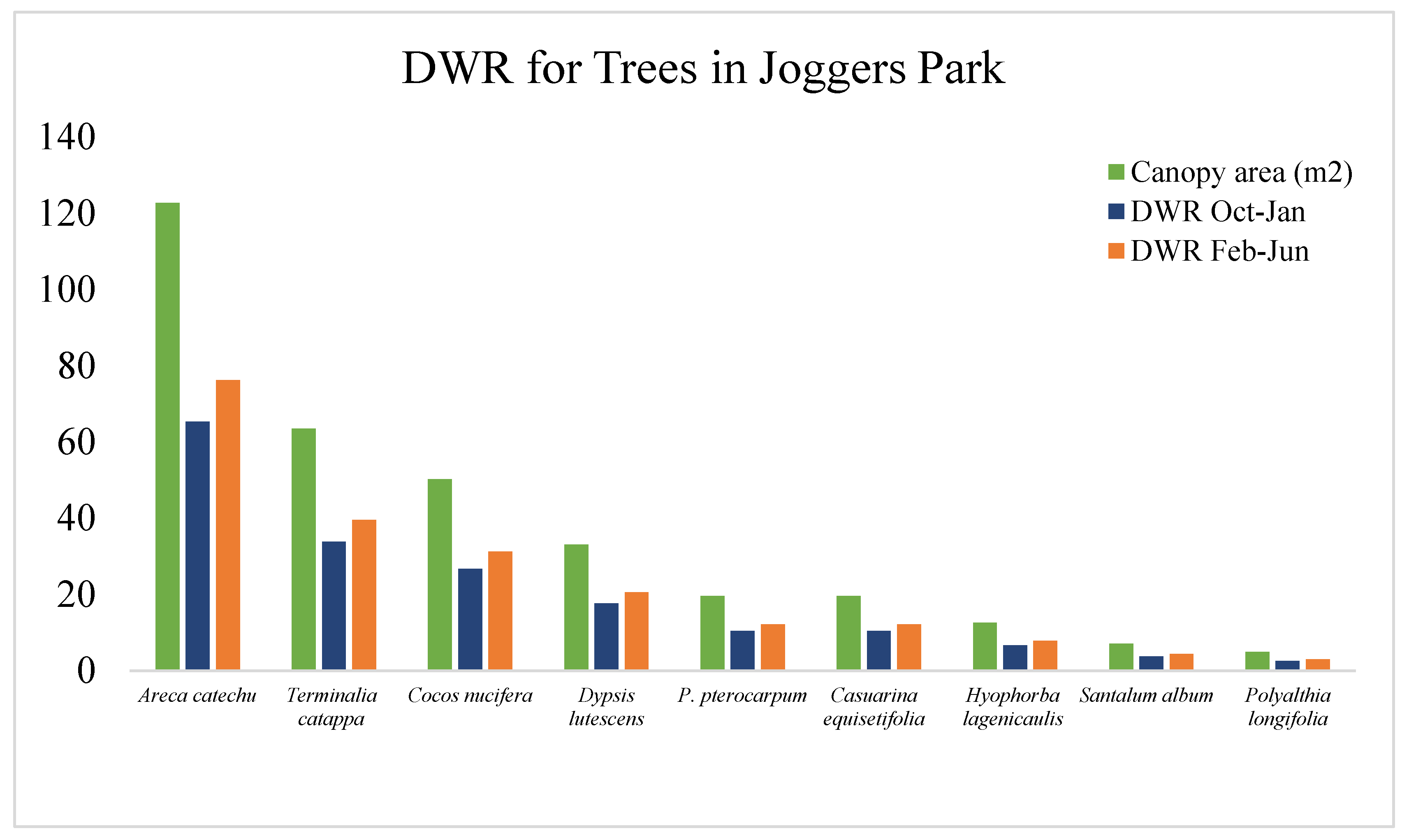

3.3. Canopy Areas and Water Requirements of Different Species of Trees

3.4. Regression Relationships

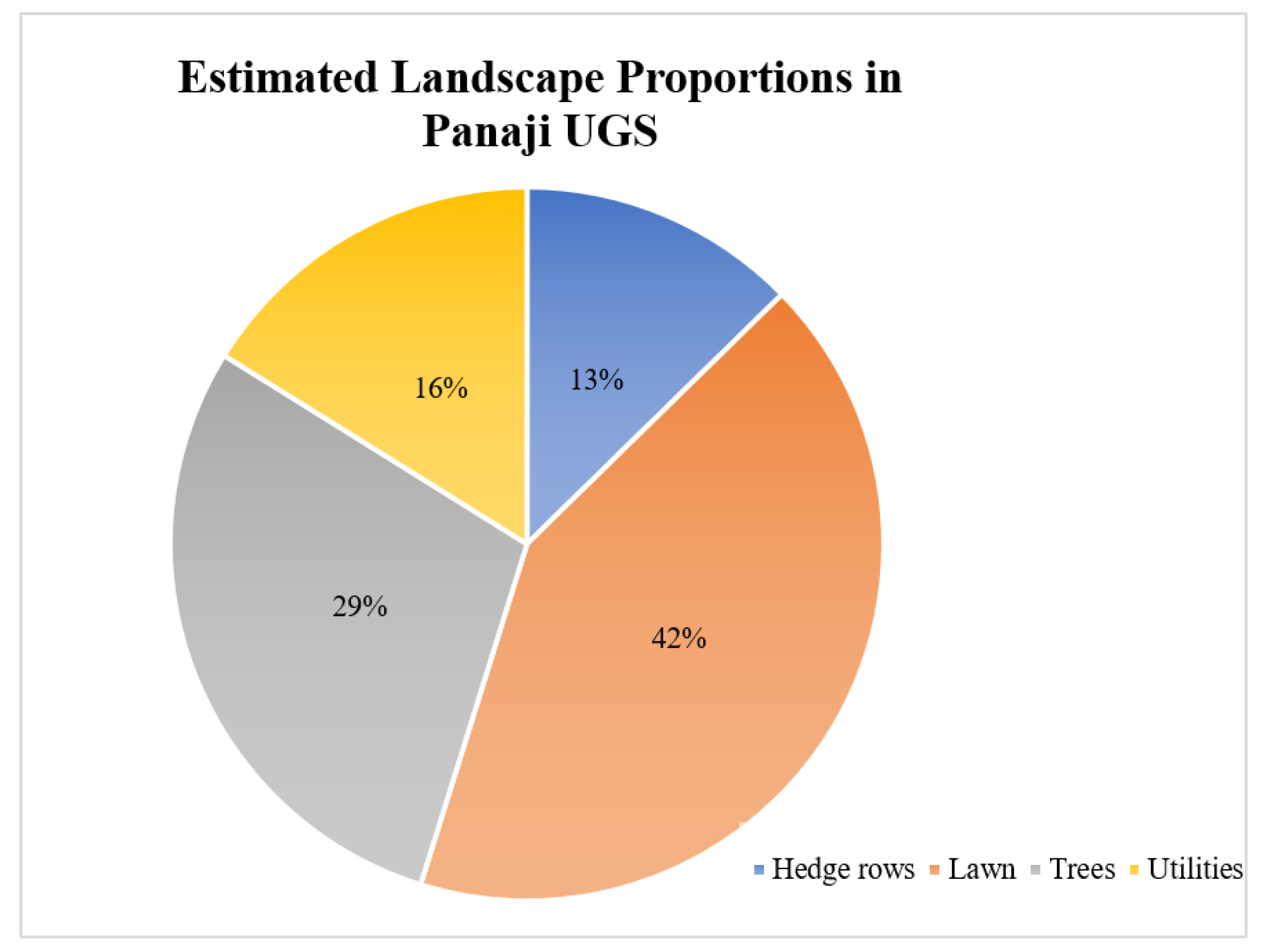

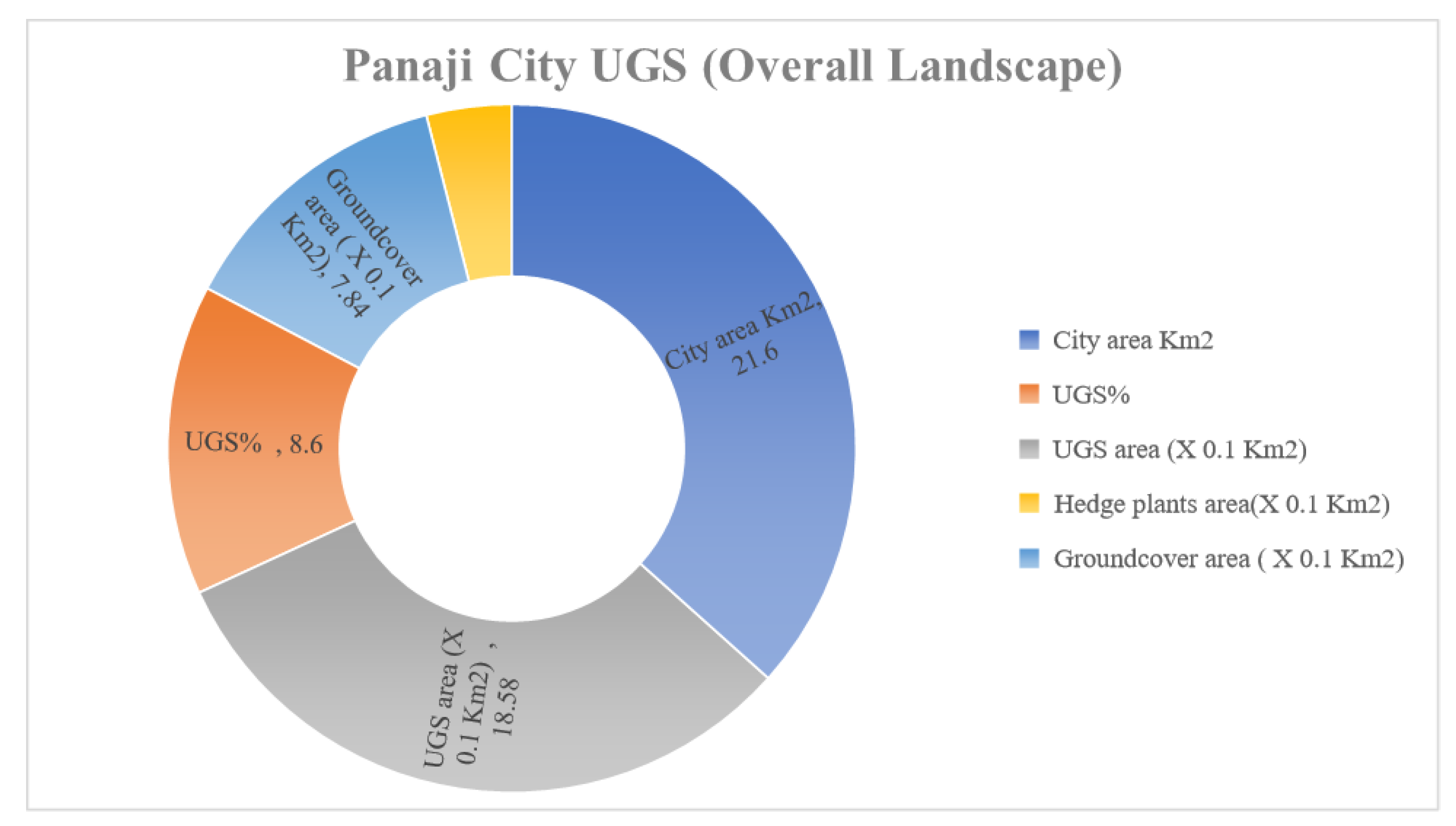

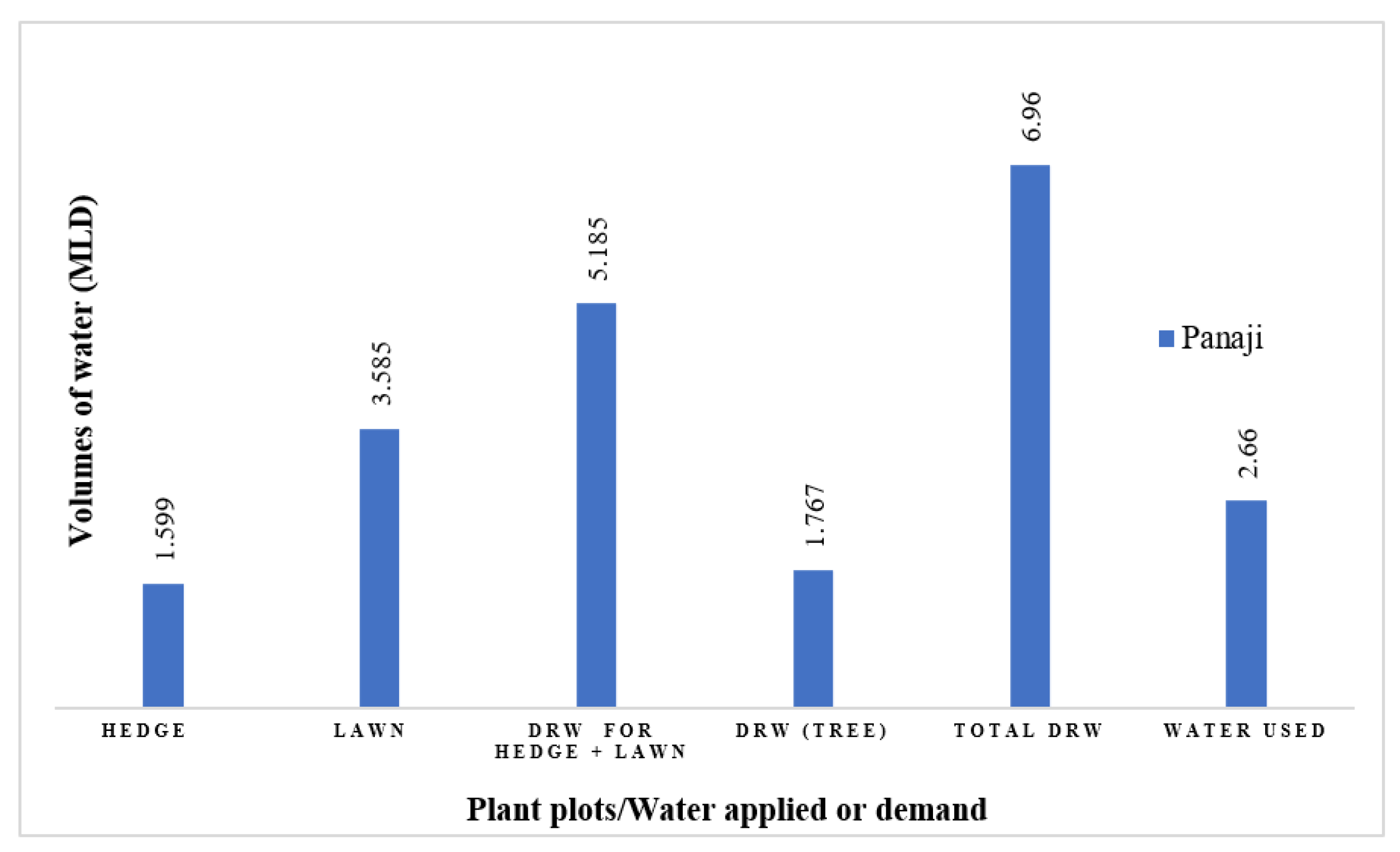

3.5. DWR in the UGS of Panaji City

4. Discussion

4.1. Need for Background Details of Microclimate Factors

4.2. Importance of Establishing Regional ETo

4.3. Considerations for Assessing Water Requirements in the UGS

4.4. DWR for Trees, Hedges and Groundcover

4.5. Need for Treated Wastewater Use in UGS in Reducing Groundwater Extraction

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Abrus precatorius | 27 | Jatropha curcas |

| 2 | Acacia catechu | 28 | Justicia adhatoda |

| 3 | Acorus calamus | 29 | Justicia gendarussa |

| 4 | Aegle marmelos | 30 | Lawsonia inermis |

| 5 | Aloe barbadensis | 31 | Mimusops elengi |

| 6 | Alstonia scholaris | 32 | Mesua ferrea |

| 7 | Andrographis paniculata | 33 | Moringa oleifera |

| 8 | Annona muricata | 34 | Murraya koenigii |

| 9 | Annona squamosa | 35 | Ocimum tenuiflorum |

| 10 | Artemisia vulgaris | 36 | Phyllanthus emblica |

| 11 | Asparagus racemosus | 37 | Phyllanthus fraternus |

| 12 | Azadirachta indica | 38 | Pogostemon cablin |

| 13 | Bacopa monnieri | 39 | Piper longum |

| 14 | Boerhavia diffusa | 40 | Piper nigrum |

| 15 | Bryophyllum pinnatum | 41 | Rauvolfia serpentina |

| 16 | Butea monosperma | 42 | Saraca asoca |

| 17 | Cassia fistula | 43 | Stevia rebaudiana |

| 18 | Catharanthus roseus | 44 | Strychnos nux-vomica |

| 19 | Centella asiatica | 45 | Syzygium cumini |

| 20 | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | 46 | Terminalia arjuna |

| 21 | Cissus quadrangularis | 47 | Terminalia bellirica |

| 22 | Ficus racemosa | 48 | Terminalia chebula |

| 23 | Garcinia indica | 49 | Tinospora cordifolia |

| 24 | Gloriosa superba | 50 | Vitex negundo |

| 25 | Gymnema sylvestre | 51 | Withania somnifera |

| 26 | Hemidesmus indicus | 52 | Zanthoxylum rhetsa |

| Common name | Botanical Name |

| Golden duranta | Duranta erecta |

| Acalypha | Acalypha wilkesiana |

| Eranthemum | Eranthemum pulchellum |

| Allamanda | Allamanda cathartica |

| Panama Rose | Arachnothryx leucophylla |

| Gardenia | Gardenia jasminoides |

| Tutia | Solanum sisymbriifolium |

| Dracena | Dracaena marginata |

| Bouganvilla | Bougainvillea spp |

| Croton | Codiaeum variegatum |

| Areca Palm | Dypsis lutescens |

| Pentas | Pentas lanceolata |

| Balsam | Impatiens balsamina |

| Agave | Agave americana |

| Hibiscus | Hibiscus rosa-sinensis |

| Spider plants | Chlorophytum comosum |

| Local name | Botanical name | Family |

| Gardenia | Gardenia jasminoides | Rubiaceae |

| Tutia | Solanum sisymbriifolium | Solanaceae |

| Panama Rose | Arachnothryx leucophylla | Rubiaceae |

| Almonda | Allamanda cathartica | Apocynaceae |

| Croton | Codiaeum variegatum | Euphorbiaceae |

| Golden duranta | Duranta erecta | Verbenaceae |

| Eranthemum | Eranthemum pulchellum | Acanthaceae |

| Nerium | Nerium oleander | Apocynaceae |

| Ixora | Ixora coccinea | Rubiaceae |

| Hibiscus | Hibiscus rosa-sinensis | Malvaceae |

| Red and green dressina | Dracaena marginata | Asparagaceae |

| Althernatum | Althernatum sp | |

| Balsam | Impatiens balsamina | Balsaminaceae |

| Jocupus Rendulus |

References

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. (1998). Chapter 4—Determination of ETo. FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/x0490e/x0490e08.htm#.

- Beeson, R. Modeling Irrigation Requirements for Landscape Ornamentals. HortTechnology 2005, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, R.C. Development of a Simple Reference Evapotranspiration Model for Irrigation of Woody Ornamentals. HortScience Horts 2012, 47, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA). (2020). NOCAP. http://cgwa-noc.gov.in/LandingPage/index.htm.

- Corporation of the City of Panaji, & CRISIL Risk and Infrastructure Solutions Limited. (2015, February). Revised City Development Plan for Panaji, 2041. Imagine Panaji. http://imaginepanaji.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Revised-City-Development-Plan-for-Panaji-2041-2.pdf.

- Costello, L.R.; Jones, K.S.; McCreary, D.D. Irrigation effects on the growth of newly planted oaks (Quercus spp.). Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 2005, 31, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, L.R.; Matheny, N.P.; Clark, J.; Jones, K.S. (2000). A Guide to Estimating Irrigation Water Needs of Landscape Plantings in California, the Landscape Coefficient Method and Wucols III. University of California Cooperative Extension, California Department of Water Resources: Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Kjelgren, R.; Beeson, R.; Pittenger, D.; Montague, T. Simplified Landscape Irrigation Demand Estimation: SLIDE Rules. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2016, 32, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, H.; Beecham, S.; Kazemi, F.; Hassanli, A. A review of ET measurement techniques for estimating the water requirements of urban landscape vegetation. Urban Water Journal 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannkuk, T.R.; White, R.H.; Steinke, K.; Aitkenhead-Peterson, J.A.; Chalmers, D.R.; Thomas, J.C. Landscape Coefficients for Single- and Mixed-species Landscapes. HortScience Horts 2010, 45, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Cordery, I.; Iacovides, I. Improved indicators of water use performance and productivity for sustainable water conservation and saving. Fuel and Energy Abstracts 2012, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, D.R.; Shaw, D.A. Estimating water needs of urban landscapes 2010, 45, S96–S96.

- Pittenger, D.R.; Shaw, D.A.; Hodel, D.R.; Holt, D.B. Responses of Landscape Groundcovers to Minimum Irrigation. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 2001, 19, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, D.; Shaw, D. (2013). Making Sense of ET Adjustment Factors for Budgeting and Managing Landscape Irrigation. https://www.irrigation.org/IA/FileUploads/IA/Resources/TechnicalPapers/2013/MakingSenseOfETAdjustmentFactorsForBudgetingAndManagingLandscapeIrrigation.pdf.

- Qaderi, M.M.; Martel, A.B.; Dixon, S.L. Environmental Factors Influence Plant Vascular System and Water Regulation. Plants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaiah, M. (2021). Role of treated wastewater in mitigating urbanization impacts and maintaining regulatory ecosystem services. Ph D Thesis, Hokkaido University.

- Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R. Urban Green Spaces and Their Need in Cities of Rapidly Urbanizing India: A Review. Urban Science 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R.; Kumar, P. Treated Wastewater Use for Maintenance of Urban Green Spaces for Enhancing Regulatory Ecosystem Services and Securing Groundwater. Hydrology 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R.; Rahman Md, M. Land Cover Influences on LST in Two Proposed Smart Cities of India: Comparative Analysis Using Spectral Indices. Land 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.C.; Dukes, M.D. (2010). Residential benchmarks for minimal landscape water use. Gainesville, FL. Agricultural and Biological Engineering Dept., Univ. of Florida UF Water Institute, USA, 49.

- Rosa, R.; Dicken, U.; Tanny, J. Estimating evapotranspiration from processing tomato using the surface renewal technique. Biosystems Engineering 2013, 114, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. (2018, December 13). Tumkur: A Smart City in the Making. Silicon India. https://www.siliconindia.com/news/general/Tumkur-A-Smart-City-in-the-Making-nid-206312-cid-1.html.

- Shaw, D.A.; Pittenger, D. Performance of landscape ornamentals given irrigation treatments based on reference evapotranspiration. Acta Horticulturae 2004, 664, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.L.; Pedras, C.; Montazar, A.; Henry, J.M.; Ackley, D. Advances in ET-based landscape irrigation management. Agricultural Water Management: Priorities and Challenges 2015, 147, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.; Pruitt, W. (1992). Evapotranspiration data management in California. 128–133.

- Staats, D.; Klett, J.E. Water conservation potential and quality of non-turf groundcovers versus Kentucky bluegrass under increasing levels of drought stress. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 1995, 13, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCANR (2020). Estimating Tree Water Requirements. https://ucanr.edu/sites/UrbanHort/Water_Use_of_Turfgrass_and_Landscape_Plant_Materials/Estimating_Water_Requirements_of_Landscape_Trees.

| Park | Area (m2) | No of species | Ground cover (m2) | Source of water | Daily water used (L) | Annual litter fall (tons) | #of staff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trees (Total number) | Ornamental (hedge length; m) | |||||||

| Kala Academy | 10630 | 21 (300) | 6 (400) | 2675 | Borewell | 10000 | 15 | 6 |

| North Goa Range Forest Park | 5000 | 18 (390) | 6 (200) | 2250 | Borewell | 4800 | 10 | 3 |

| South Goa Range Forest Park | 6500 | 9 (200) | 52 medicinal | 1625 | Borewell | 8400 | 6* | 5 |

| Mahavir Park | 18312 | 27 (3130) | 17 (3000) | 6410 | Borewell | 15000 | 60 | 22 |

| Art Park | 18999 | 0 | 0 | Not watered | 0 | 30 | ||

| Garcia da Orta Garden | 4000 | 12 (180) | 6 (450) | 1500 | Corporation water + Borewell | 4000 | 6 | 5 |

| Ambedkar Park | 10000 | 15 (400) | 17 (1800) | 6500 | Treated wastewater | 16000 | 25 | 12 |

| Joggers Park | 11500 | 8 (400) | 12 (2600) | 6900 | Borewell | 36000 | 12 | 22 |

| Month | Rn | PC | Tmin | Tmax | Td | ws (m s−1) |

SVP slope kPa K−1 |

SVP | VP e, kPa | EToG day-time |

EToG night-time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 28.9 | 0.067 | 20.3 | 31.5 | 19 | 1.194 | 0.198 | 3.36 | 3.4 | 8.213 | 6.829 |

| Feb | 32.3 | 0.067 | 21.0 | 31.4 | 20 | 1.278 | 0.201 | 3.39 | 3.4 | 9.180 | 7.564 |

| Mar | 35.7 | 0.067 | 23.4 | 32.1 | 23 | 1.278 | 0.218 | 3.78 | 3.7 | 10.395 | 8.500 |

| Apr | 38.1 | 0.067 | 25.8 | 33 | 24 | 1.472 | 0.236 | 4.17 | 4.1 | 11.233 | 9.227 |

| May | 38.7 | 0.067 | 27.0 | 33.4 | 25 | 2.083 | 0.245 | 4.35 | 4.3 | 11.199 | 8.676 |

| Jun | 38.6 | 0.067 | 25.2 | 30.8 | 25 | 1.833 | 0.22 | 3.78 | 3.8 | 10.947 | 8.556 |

| July | 38.5 | 0.067 | 24.6 | 29.3 | 25 | 2.861 | 0.209 | 3.57 | 3.6 | 10.193 | 7.135 |

| Aug | 38.1 | 0.067 | 24.4 | 29 | 25 | 2.639 | 0.206 | 3.53 | 3.6 | 10.147 | 7.230 |

| Sep | 36.4 | 0.067 | 24.2 | 29.6 | 25 | 1.556 | 0.208 | 3.58 | 3.6 | 10.296 | 8.236 |

| Oct | 33.2 | 0.067 | 24.0 | 31.2 | 24 | 0.972 | 0.216 | 3.76 | 3.7 | 9.799 | 8.469 |

| Nov | 29.6 | 0.067 | 22.4 | 32.2 | 22 | 1.056 | 0.212 | 3.75 | 3.6 | 8.655 | 7.384 |

| Dec | 27.9 | 0.067 | 21.0 | 32 | 20 | 0.917 | 0.204 | 3.46 | 3.5 | 8.126 | 7.037 |

| Park | Kala Academy | NGRF Office Park | SGRF Office Park | Mahavir Park+Art Park | Garcia da Orta Garden | Ambedkar Park | Joggers Park |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Area (m2) | 10630 | 5000 | 6500 | 37211 | 4000 | 10000 | 11500 |

| Trees (n^) | 250 | 290 | 180 | 3130 | 150 | 480 | 400 |

| Hedge area (m2) | 360 | 160 | 800 | 2700 | 405 | 1620 | 2340 |

| lawn (m2) | 2675 | 2250 | 1625 | 6410 | 1500 | 6500 | 6900 |

| Road/lanes/parking lot (m2) | 4300 | 1200 | 2800 | 6000 | 600 | 750 | 2500 |

| Hedges area (%) [A] | 3.39 | 3.20 | 12.31 | 7.26 | 10.13 | 16.2 | 20.35 |

| Lawn area (%) [B] | 25.17 | 45 | 25.00 | 17.23 | 37.50 | 65 | 42.61 |

| Road/parking area (%) [C] | 40.46 | 24 | 43.08 | 16.13 | 15.00 | 7.50 | 21.74 |

| sum of [A]+ [B] +[C] | 69.01 | 72.20 | 80.38 | 40.61 | 62.62 | 88.70 | 84.70 |

| Area covered by trees (%) | 31.99 | 27.80 | 19.62 | 59.39 | 37.38 | 11.30 | 15.30 |

| Area covered by trees (m2) | 3295 | 1390 | 1275 | 22101 | 1495 | 1130 | 1760 |

| No of trees | 250 | 290 | 180 | 3130 | 150 | 480 | 400 |

| Area available per tree (m2) | 13.18 | 4.79 | 7.08 | 7.09 | 9.97 | 2.36 | 4.40 |

| Park$ | Area (m2) | Trees (n^) |

Hedge area (m2) | lawn (m2) | Current supply (LPD) | Daily Water Requirement (Litres per Day. LPD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trees# | Hedges | Lawn | Demand | ||||||

| Kala Academy | 10630 | 250 | 360 | 2675 | 10000 | 5991.25 | 2437.20 | 12224.75 | 20653.20 |

| NGRF Office Park | 5000 | 290 | 160 | 2250 | 4800 | 6949.85 | 1083.20 | 10282.50 | 18315.55 |

| SGRF office Park | 6500 | 180 | 800* | 1625 | 6000 | 4313.70 | 5416.00 | 7426.25 | 17155.95 |

| Mahavir Park+Art Park | 37211 | 3130 | 2700 | 6410 | 8400 | 75010.45 | 18279.00 | 29293.70 | 122583.20 |

| Garcia da Orta Garden | 4000 | 150 | 405 | 1500 | 15000 | 3594.75 | 2741.85 | 6855.00 | 13191.60 |

| Ambedkar Park | 10000 | 480 | 1620 | 6500 | 4000 | 11503.20 | 10967.40 | 29705.00 | 52175.60 |

| Joggers Park | 11500 | 400 | 2340 | 6900 | 16000 | 9586.00 | 15841.80 | 31533.00 | 56960.80 |

| Total | 84841 | 4880 | 8385 | 27860 | 64200 | 116949.20 | 56766.45 | 127320.20 | 301035.90 |

| Tree (scientific name) | Number | Height (m; range) | Canopy dia (m; Range) | Girth circumference (cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | ±SD | ||||

| Casuarina (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 1485 | 18-22 | 5-6 | 23 | 102.35 | 19.24 |

| Acacia (Acacia auriculiformis) | 510 | 7-10 | 8-9 | 18 | 129.56 | 13.81 |

| Karanj (Millettia pinnata) | 294 | 15-18 | 7-8 | 15 | 126.73 | 21.3 |

| Shankar (Caesalpinia pulcherima) | 147 | 8-11 | 8-9 | 12 | 101.67 | 10.47 |

| Badam (Terminalia catappa) | 129 | 6-8 | 12-14 | 12 | 102.92 | 8.908 |

| Ashok (Polyalthia longifolia) | 89 | 6-9 | 3-4 | 10 | 76.40 | 6.168 |

| Apto (Bauhinia purpurea) | 87 | 11-15 | 8-9 | 11 | 119.18 | 17.14 |

| Jambal (Syzygium cumini) | 74 | 9-11 | 10-12 | 11 | 124.09 | 21.61 |

| Tecoma (Tecoma capensis) | 53 | 7-9 | 7-9 | 11 | 112.36 | 14.42 |

| Gulmohar (Delonix regia) | 44 | 16-19 | 15-18 | 10 | 198.10 | 15.99 |

| Saton (Alstonia scholaris) | 27 | 8-10 | 8-10 | 10 | 112.90 | 17.77 |

| Taman (Lagerstroemia speciosa) | 26 | 10-12 | 12-14 | 9 | 138.78 | 9.935 |

| Peltophorum (Peltaphorum pterocarpum) | 25 | 17-19 | 10-12 | 16 | 80.50 | 8.422 |

| Spatodea (Spatodea companulata) | 24 | 13-15 | 9-11 | 13 | 121.08 | 10.28 |

| Oval (Mimusops elengi) | 23 | 7-9 | 8-10 | 11 | 132.09 | 8.608 |

| Palm (Dypsis lutescens) | 16 | 8-11 | 7-8 | 6 | 124.33 | 11.91 |

| Musaenda (Mussaenda erythrophylla) | 15 | 4-6 | 6-7 | 13 | 52.154 | 4.947 |

| Bottle Palm (Hyophorba lagenicaulis) | 13 | 8-12 | 4-5 | 8 | 41.25 | 2.55 |

| Bayo (Cassia fistula) | 13 | 9-12 | 5-6 | 7 | 110.86 | 7.625 |

| Rain tree (Samanea saman) | 11 | 19-23 | 25-30 | 6 | 259.83 | 23.56 |

| Ritha (Sapindus mukorossi) | 9 | 5-7 | 8-10 | 6 | 111.83 | 24.76 |

| Pithecellobium dulce (Inga dulcis) | 5 | 9-12 | 14-15 | 3 | 100.67 | 11.72 |

| Palas (Butea monosperma) | 4 | 7-10 | 7-8 | 3 | 92.50 | 4.95 |

| Avalo (Phyllantus emblica) | 3 | 7-9 | 5-6 | 2 | 64.00 | 0 |

| Chinch (Tamarindus indica) | 2 | 11-12 | 15 | 2 | 164.00 | 11.31 |

| Java cassia (Cassia javanica) | 1 | 7 | 8 | NM | NM | |

| Surang (Mammea suriga) | 1 | 9 | 9 | NM | NM | |

| Tree | Number | Height (m; range) | Canopy diameter (m; Range) | Girth circumference (cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | ±SD | ||||

| Peltophorum, P. pterocarpum | 184 | 10-15 | 3-7 | 22 | 81.67 | 6.64 |

| Casuarina, Casuarina equisetifolia | 92 | 8-11 | 4-7 | 13 | 95.25 | 14.69 |

| Ashoka tree, Polyalthia longifolia | 52 | 10-12 | 3-5 | 8 | 81.57 | 3.69 |

| Bottle palm, Hyophorba lagenicaulis | 48 | 5-8 | 3-4 | 10 | 42.40 | 2.99 |

| Coconut palm, Cocos nucifera | 26 | 7-10 | 7-9 | 12 | 98.17 | 5.97 |

| Badam, Terminalia catappa | 26 | 7-10 | 8-12 | 10 | 102.80 | 8.40 |

| Veni tree, Acacia ferruginea | 12 | 11-15 | 7-10 | 6 | 55.33 | 1.75 |

| Rain tree, Samanea saman | 9 | 20-22 | 20-24 | 4 | 271.00 | 35.35 |

| Acacia, Acacia auriculiformis | 8 | 10-12 | 11-14 | 5 | 118.60 | 0.89 |

| Bamboo, Phyllostachys pubescens | 7 | 8-10 | 7-12 | 18 shoots | 38.22 | 3.04 |

| Mango, Mangifera indica | 6 | 13-16 | 8-13 | 6 | 72.67 | 3.56 |

| Gulmohar, Delonix regia | 6 | 17-19 | 25-30 | 4 | 138.00 | 18.20 |

| Sandalwood, Santalum album | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 24.50 | 2.12 |

| Tree | Number | Height (m; range) | Canopy diameter (m; range) | Girth circumference (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | ±SD | ||||

| Peltophorum, P. pterocarpum | 213 | 12-15 | 3-7 | 11 | 82.46 | 8.99 |

| Coconut palm, Cocos nucifera | 48 | 5-11 | 7-9 | 14 | 95.79 | 7.88 |

| Beetlenut palm, Areca catechu | 42 | 6-10 | 11-14 | 10 | 34.67 | 3.74 |

| Bottle palm (Hyophorba lagenicaulis) | 33 | 5-6 | 3-5 | 6 | 67.33 | 5.79 |

| Ashoka tree, Polyalthia longifolia) | 32 | 10-12 | 2-3 | 8 | 71.50 | 7.09 |

| Palm, Dypsis lutescens | 12 | 3-10 | 4-9 | 8 | 114.25 | 9.47 |

| Casuarina, Casuarina equisetifolia | 10 | 7-10 | 4-6 | 10 | 77.40 | 7.71 |

| Badam, Terminalia catappa | 8 | 6-8 | 8-10 | 5 | 40.60 | 2.07 |

| Sandalwood Santalum album | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 29.00 | 2.83 |

| Independent variable | Dependent variable | Regression Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mahavir Park | |||

| Mean Canopy | DWR Oct-Jan | y = 236.42x - 622.42 | 0.8333 |

| DWR Feb-Jun | y = 275.82x - 726.15 | 0.8333 | |

| Ambedkar Park | |||

| Mean Canopy | DWR Oct-Jan | y = 469.32x - 2230.6 | 0.9417 |

| DWR Feb-Jun | y = 547.55x - 2602.5 | 0.9417 | |

| Joggers Park | |||

| Mean Canopy | DWR Oct-Jan | y = 20.306x + 3.5236 | 0.4358 |

| DWR Feb-Jun | y = 23.69x + 4.1144 | 0.4358 | |

| Parameters | Primary data from 7 Surveyed Parks# | Data of DRW + others |

|---|---|---|

| Panaji | ||

| City area Km2 | 21.60* | |

| UGS% in city area | 8.60* | |

| UGS area; Km2 | 1.858* | |

| Hedge plants area (@12.72% of UGS, Km2 | 8385 | 0.236 |

| Groundcover area (@ 42.23% of UGS; Km2 | 25860 | 0.784 |

| Water used in UGS @ av. 2.6LPD (MLD) | 64000 | 2.66* |

| Hedge DWR @ 6.77L m−2 (MLD) | 56766.45 | 1.599 |

| Groundcover DWR @ 4.57Lm−2 (MLD) | 118180.2 | 3.585 |

| Total DWR (MLD) | 107945.6 | 5.184 |

| % DRW shortage hedge + groundcover | 125952.8 | 51.30 |

| DRW @ for hedge + ground cover (MLD)$$ | 0.184 | 5.185 |

| Trees’ area (28.97±16.30% of UGS; Km2) | 32446 | 0.538 |

| Trees area in ha | 3.25 | 53.82 |

| No of trees [@ 1 tree in 8 (±13) m−2] | 4880 | 67275 |

| Average DRW/tree @ 23.87L (MLD) | 0.117 | 1.606 |

| Trees’ DRW % of available treated water | 15.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).