1. Introduction

Adequate sleep is crucial to well-being and optimal daytime functioning. Sleep serves a lot of important purposes such as memory and learning, aiding attention, clearing up neuronal wastes like beta-amyloid, improving cardiovascular, metabolic and immune functions, amongst others [

1,

2].

However, the provision of essential services such as extended work hours, on- and off- office work, and shift-work, which is part of doctor’s care may disrupt sleep health, in terms of timing, efficiency, quality recommended period i.e., at least 7 to 9 hours per night in adults [

3].

Shift work as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO), is a method of work-schedule, in which the period of work by workers follow each other without break, So that the organization can operate for 24hours, and have personnel to cover for both day and night time [

4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and ILO 2016 global estimates revealed that 398,000 and 347,000 persons died from stroke and heart disease respectively, as consequences of working for 55 hours or more a week [

5]. Barger et al.,[

6] stated that in the United States of America, among resident doctors (RD), working for more than 48 hours a week was linked with an increased risk of medical errors, occupational injuries e.g., needle stick injuries and motor vehicular accidents. Heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, poor immunity, cognitive impairment, cancer etc. are documented long term consequences of shift work and poor sleep [

7].

Sleep disturbances is a distressing and disabling condition that affects many people, and can affect the quality of work of intern doctors (ID) and RD. Balogun et al., [

8] reported that the mean weekly work duration of Nigerian RD is 106.5 ± 50.4 hours, and a significant percentage of RD, work for about 24 hours straight during weekday-calls 854 (77.3%) and 48–72 hours during weekends-calls 568 (51.4%).

Doctors in the junior cadre, especially ID and junior residents in Nigeria mostly bear the brunt as they spend more time in the hospital with more stringent work schedules including call hours. Therefore, they have a higher risk of acute and chronic sleep deprivation, insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders. Some Doctors use stimulants like coffee, kolanut, energy drinks, tea amongst others to keep awake and alert and as a buffer for work related stress [

9,

10].

The main purpose of this research is to study and understand the influence of extended workload on ID and RD’s sleep quality, pattern and duration.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: This study employed a cross-sectional design through purposive sampling. The study population included medical and dental interns as well as resident doctors in various institutions across the country.

Study Setting: The study was conducted at various hospitals comprising of Federal Teaching Hospitals (FTHs) State Teaching Hospitals (STHs), Federal Medical Centers (FMCs), as well as Specialist Hospitals (SHs), General Hospitals (GH) and Private Hospital (PH)s across the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria.

Ethical Considerations: Ethical clearance was obtained for the study from the Ethics and Research Committee of Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife, with protocol number ERC/2024/04/15.

Study Duration: The study was conducted over a period of three months between May 2024 and July 2024.

Study Procedure: The data collection tool is a 32-item electronic questionnaire that was designed using Google Forms. The questionnaire was electronically distributed via emails and social media platforms, including WhatsApp and Telegram, to various hospitals across the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria. Participation in the study was voluntary, and no incentive was offered for participation. The questionnaire had no personal identifying information. Consent to participate in the study was implied by completing the questionnaire and submitting responses.

The Survey Questionnaire: The survey consisted of four sections. The first section contained information on the sociodemographic parameters about the respondents such as their age, gender, institution, department and current rotation. The second section included sleep and health history about the respondents. In the third section, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used to assess daytime sleepiness of the respondent. The fourth section included the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) for those respondents in which insomnia is one their sleep problem. Also, the excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), clinical insomnia, burnout symptoms and work hours were assessed.

Measures

The ISI consists of seven questions that were added up to determine the final score. Participants who scored 0–7, 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 on the ISI were classified as having “no clinically significant insomnia,” “subthreshold insomnia,” “moderate clinical insomnia,” and “severe clinical insomnia,” respectively.

The ESS was used to measure subjective sleepiness. The test comprises eight situations in which we rate the patient’s tendency to become sleepy on a scale of 0 (no chance of dozing) to 3 (high chance of dozing). The participant’s total score is a sum of the eight questions. Participants were scored and categorized into one of five categories: Low level of normal daytime sleepiness (score 0-5), Higher level of normal daytime sleepiness (score 6-10), Mild excessive daytime sleepiness (score 11-12), Moderate excessive daytime sleepiness (score 13-15) and Severe excessive daytime sleepiness (score 16-24).

Data Analysis: Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 18 software. Bivariate analysis was done with Pearson’s chi-square, t-test, ANOVA, Mann Whitney and Kruskal Wallis test as appropriate. Jonckheere–Terpstra test was used to compare the weekly work hours in the Insomnia Severity Score categories. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This statistical approach allowed for the evaluation of the relationships between various factors, such as sleep duration and the occurrence of sleep-related issues, across the resident doctors and interns.

3. Results

A total of 280 respondents participated in this study. The RD make up three-quarters 208 (74.3%) while ID make up a quarter 72 (25.7%). Compared to dental officers, medical RD 109 (52.5%) and medical ID 63 (87.5%) were the majority. More than 80% of the respondents were from federal institutions. The mean age for RD and ID were 35.827 (5.237) and 27.111 (3.507) respectively. The mean duration of residency training and internship for RD and ID were 40.8 (34.97) months and 148.3 (92.67) days respectively (

Table 1).

The mean ESS score for RD and ID were 11.04 (4.702) and 10.91 (4. 202) respectively while the mean ISI score for RD and ID was 9.77 (6.659) and 11.3 (6.143) respectively. The prevalence of high daytime sleepiness score was 75 (38.7%) in RD and 21 (36.2%) in ID. The prevalence of severe EDS was 39 (20.1%) among RD and 7 (12.1%) among ID. Also, 62 (34.6%) of respondents have sub-threshold insomnia, 36 (20.1%) have moderate insomnia while 11 (6.1%) have severe insomnia (

Table 2).

The prevalence of both frequent and very frequent experience of burnout symptoms was 96 (47.7%). Fatigue was present in 196 (88.3%), loss of motivation in 120 (67.8%) and suicidal thoughts in 6 (2.7%). Hopelessness or depression was present in 25 11.3%), inability to make decision was 44 (19.8%), moody and irritable symptom was reported in 125 (56.3%), and feeling exhausted in 139 (62.6%) (

Table 3)

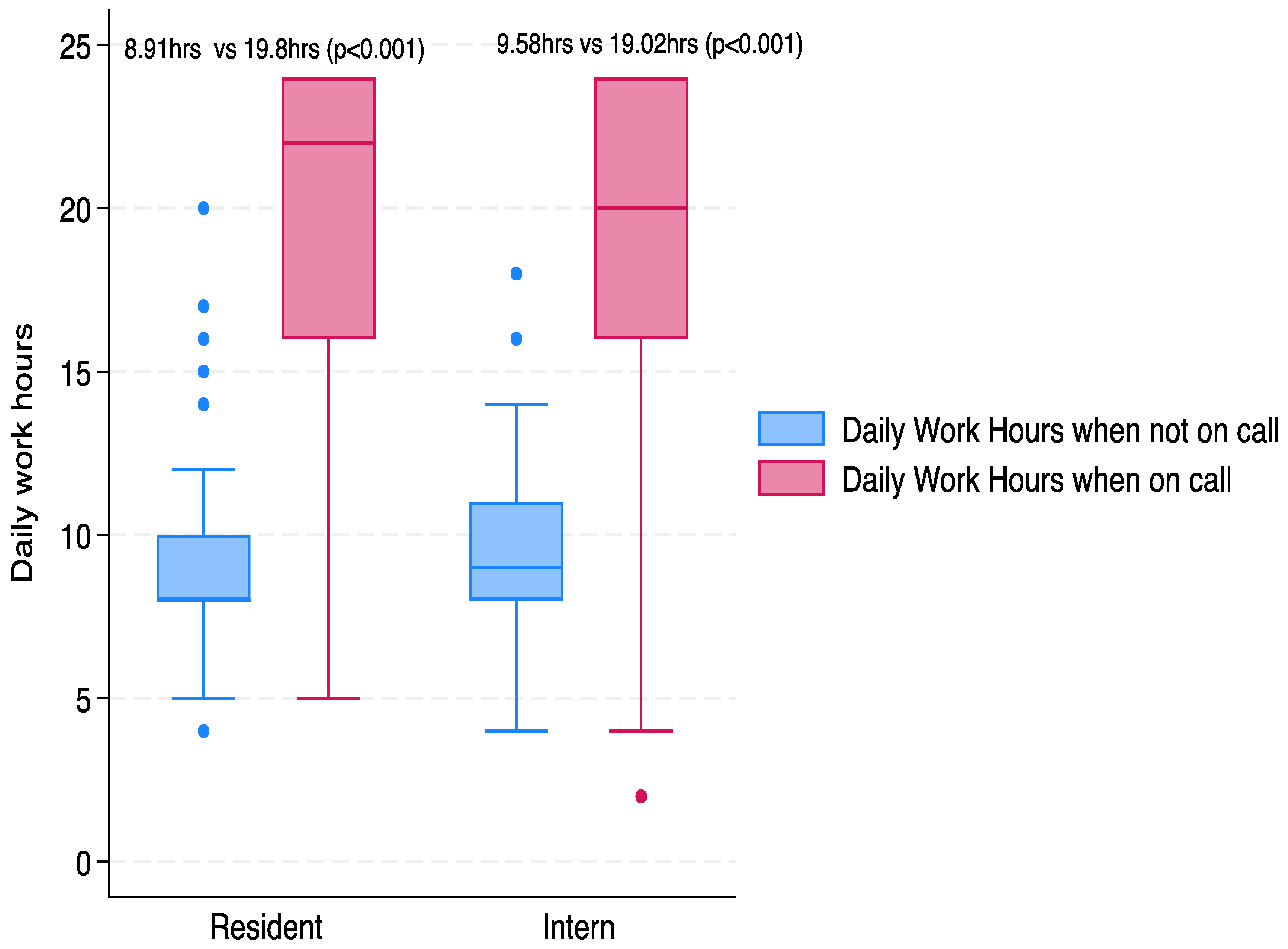

The amount of work hours per day when not on call for was RD 8.914 (2.118) hours and ID was 9.576 (2.343) hours. The amount of work hours per day when on call for RD was 19.804 (5.101) hours and ID was 19.017 (5.680) hours. The average number of days on calls per week was 2.963 (2.757) days and 3.931 (3.977) days for RD and ID respectively (

Figure 1).

The average hours of daily sleep before internship or residency were 8.096 (1.300) hours and 7.847 (1.544) hours for RD and ID respectively. The average hours of daily sleep during internship or residency were 5.529 (1.120) hours and 5.319 (1.085) hours for RD and ID respectively. About 91.8% of RD and ID did not have sleep problem before residency or internship. Whereas, 47.1% of respondents reported sleep problem during residency or internship. A total of 155 (74.5%) residents and 48 interns (66.7%) are unwilling to see a sleep doctor. (

Table 4).

The occurrence of specific sleep disorders for resident doctors and interns was low before residency and internship. Nightmares were present in two doctors (0.7%), insomnia in 18 (6.4%) and sleep breathing problems in one doctor (0.4%). The prevalence of specific sleep disorders increased during residency or internship with nightmares present in 11 (3.9 %), insomnia in 115 (41.4%) and sleep breathing problem in 11 (3.9%). Insomnia was the most common sleep disorder reported by both resident doctors and interns in 115 doctors (41.1%). (

Table 5)

4. Discussion

The study found that among RD and ID in Nigerians hospitals, the average ESS scores was 11.04 and 10.91, average ISI scores were 9.77 and 11.3, high day time sleepiness was 38.7% and 36.2%, severe EDS was 20.1% and 12.1%, respectively. Also, 34.6% have sub-threshold insomnia while 26.2% have either moderate or severe insomnia

Indeed, these findings are grievous and worrisome. The findings demonstrate a substantial burden of sleep disturbances, including EDS and insomnia, among RD and ID in Nigerian hospitals. It highlights the impact of heavy workloads and stressful work environments on sleep quality and overall well-being of doctors. The high EDS, ESS and ISI scores raises concerns on patient care and personal safety. The significant level of daytime sleepiness, may affect cognition, reduce clinical performance, and increase medical errors with compromised patient outcomes. The higher occurrence of sleep disruption among RD underscores the differences in responsibilities, work intensity, and work hours, and reflect the need for targeted interventions.

A study by Philibert et al. [

9] evaluated the impact of the 2003 duty hour limits for medical residents in the United States, set by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). These regulations capped residents’ work hours at 80 hours per week, averaged over four weeks, with shifts limited to 24 hours. The study found that while the new limits improved residents' quality of life and reduced work hours, there was a tradeoff in clinical exposure and reduced time for teaching. The authors emphasized the need to balance duty hour restrictions with the educational needs of residency programs.

Similarly, a study by Wyman et al. [

10] examined the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) on surgical training in the UK. While the EWTD successfully reduced working hours to 40 hours per week, concerns arose about insufficient hands-on clinical experience. The authors recommended adjustments to the directive to ensure adequate training while safeguarding residents' health. Despite various countries implementing work hour regulations for healthcare workers, there are currently no established recommendations for Nigerian resident doctors and interns.

Disruption in sleep-wake cycle leads to impaired mental and physical functioning, increased non-communicable diseases i.e., cardiovascular (e.g., high blood pressure, arrythmias), endocrine (e.g., obesity, diabetes), mental (e.g., anxiety, depression), and immune dysfunction, strained family and social cycle, and mood swings

Similarly, Ramar et al.,[

1] in a review of sleep health stated that insufficient sleep impairs cognitive function, cardiovascular health, immune function, and mental well-being, and is linked to chronic diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and stroke. The study calls for policies that promote sleep health, especially for healthcare workers in high-stress environments like medical residency, where adequate sleep is crucial for both personal well-being and quality patient care. This is consistent with other studies highlighting the impact of shift work and long hours on sleep patterns. Worley

2 in a review of sleep health and public safety stated that increased chronic diseases e.g., diabetes and obesity, anxiety, depression, reduced productivity, and emphasized the need for educational, clinical, and policy interventions.

We showed that both RD and ID work for long hours, averaging 9 hours daily when not on call, and more than 19 hours when on call. On average, RD are on call for 2.9 days in a week, while ID have 3.9 days call in a week. These findings have the potential to be disastrous. Other researches which show that extended shifts contribute to insufficient sleep, impairing decision-making, slower response time, reduced decision-making time and increasing professional errors [

2,

5,

6]. Sleep deprivation in high-pressure healthcare environments is linked to health risks like ischemic heart disease and stroke. These findings underscore the need for work-hour reforms to protect healthcare workers' health and patient safety, emphasizing the importance of regulating work hours and implementing systemic changes to improve well-being and reduce errors. There was also an increase in sleep disorders particularly insomnia, nightmares and sleep related breathing problems. This finding may be associated with increased weight gain; however, this requires further investigation. Nightmares might be related to the stress of residency and internship, stress of going for professional exams, juggling the demands of residency and family.

In this study, 50% have burnout symptoms while fatigue, poor motivation and feeling of exhaustion was present in more than 65% of the participants. Also, suicidal ideation depression, poor decision, and mood swing were documented. This is consistent with studies by Itani et al.,[

3] and Zee et al., [

12] which found that shift work disrupts circadian rhythms, contributing to sleep disorders and fatigue. In healthcare, these factors contribute to burnout, reduced patient safety, and long-term health issues. The studies call for interventions such as better scheduling and sleep education to mitigate the health risks of irregular work hours, particularly for medical residents.

Additionally, Adamu et al., [

9] explored stimulant use among physicians as a coping mechanism for sleep deprivation. While stimulants like caffeine or prescription medications may temporarily reduce fatigue, they can have harmful long-term effects. This highlights the need for systemic changes to reduce excessive working hours and promote healthy sleep practices, as relying on stimulants is an unsustainable solution to insufficient rest.

Balogun et al., [

8] studied the work schedules of Nigerian RD and found significant concerns about long hours and lack of sleep. Many Nigerian residents experience exhaustion due to demanding schedules, which negatively impact their health and the quality of care they provide. These findings align with other research, reinforcing the need for revisions to medical work schedules to reduce fatigue and improve safety.

Prior to beginning residency or internship, both resident doctors and interns averaged 7.8 and 8.0 hours of sleep per night, respectively. These figures align with the recommended 7 to 9 hours of sleep for adults to maintain optimal health [

1]. During this time, over 90% of residents and interns reported no significant sleep issues, such as insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness, indicating that they were generally well-rested and free from sleep disturbances before entering their demanding medical training.

However, these sleep patterns shifted dramatically once their residency or internship began. The average sleep duration decreased sharply to 5.3 hours for interns and 5.5 hours for residents. This significant reduction is consistent with the long hours and high demands typical of medical training. Previous studies have documented the disruptive effects of shift work and extended working hours on sleep [

2,

3] and the findings here mirror that trend. Sleep deprivation in these settings is well-documented, often leading to fatigue, burnout, and diminished cognitive and physical performance [

6]. The fact that more than 50% of resident doctors and interns reported experiencing sleep problems, such as insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness, during their residency or internship is concerning. This is in stark contrast to the over 90% who had no sleep issues prior to their training. The increase in sleep disturbances can be attributed to the combination of sleep deprivation, high stress, and irregular work schedules inherent in medical training [

12]. These factors create an environment conducive to sleep disturbances, which can exacerbate both physical and mental health challenges.

The reluctance of a large proportion of interns and residents to seek help from sleep specialists is also noteworthy and concerning as 74.5% of residents and 66.7% of interns were unwilling to see a sleep doctor. This reluctance may stem from several factors, including a lack of awareness about the long-term effects of sleep deprivation, a stigma surrounding sleep and mental health issues in the medical field, or the prevailing culture of overwork and self-sacrifice in healthcare. Many residents and interns may prioritize their clinical duties over their own health, feeling that seeking help for sleep problems is secondary to their patient care responsibilities [

9,

10].

The findings suggest the urgent need for systemic changes in the way medical training is structured. Implementation of workplace policies to regulate call-period, increase number of RD and ID that is available, provide quality call-rooms for adequate rest periods between work-period, could lower both mental and physical work. Furthermore, increasing access to workplace, support counseling and stress management programs can increase coping mechanisms. These changes could help maintain cognitive performance, reduce the risk of burnout, and enhance patient safety. The data also highlight the importance of addressing sleep health in medical training programs. Sleep education, promoting the recognition of sleep disorders, and reducing the stigma around seeking help could encourage interns and residents to seek professional assistance when needed. Policy changes, for instance, increasing access to sleep medicine specialists, integrating sleep management into wellness programs, and revising work schedules will promote sleep health.

5. Conclusions

The study showed that both RD and ID in Nigeria experience poor sleep quality, with high ESS and ISI scores. They also have burnout symptoms. Thus, the burden of poor sleep health is high which may negatively affect work and quality patient care.

Far reaching changes are needed in health care institutions to address the health and well-being of healthcare professionals, ensuring that their physical and mental health is not compromised by the demands of their training, and improve patient safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S., A.O., O.O., O.E.O., A.O.I., A.O., U.C.E., F.I.A., Y.B.A., K.K., K.M., M.A.K.; methodology, A.A.S., A.O., O.O., O.E.O., A.O.I., A.O., U.C.E., F.J.O., M.A.K.; formal analysis, A.A.S., A.O., O.O., O.E.O., K.M., F.J.O.; data curation, A.A.S., A.O., O.O., A.O.I., A.O., F.I.A., U.C.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.S., A.O., O.O., O.E.O., A.O.I., A.O., U.C.E., F.I.A.; writing—review and editing, P.O.O., M.B.F., Y.B.A., F.J.O., J.A.E.E., K.K., K.M., M.A.K..; supervision, P.O.O., M.B.F., Y.B.A., F.J.O., J.A.E.E., K.K., K.M., M.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant or financial support for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, and not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained for the study from the Ethics and Research Committee of Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife, with protocol number ERC/2024/04/15.

Informed Consent Statement

Consent to participate in the study was implied by completing the questionnaire and submitting responses.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESS |

Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| ID |

Intern Doctors |

| ILO |

International Labour Organization |

| ISI |

Insomnia Severity Index |

| RD |

Resident Doctors |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Ramar, K.; Malhotra, R.K.; Carden, K.A.; Martin, J.L.; Abbasi-Feinberg, F.; Aurora, R.N.; Kapur, V.K.; Olson, E.J.; Rosen, C.L.; Rowley, J.A.; et al. Sleep is essential to health: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worley, S.L. The Extraordinary Importance of Sleep: The Detrimental Effects of Inadequate Sleep on Health and Public Safety Drive an Explosion of Sleep Research. P T. 2018, 43, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Itani, O.; Kaneita, Y. The association between shift work and health: a review. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2016, 14, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conditions of Work and Employment Programme Conditions of Work and Employment Programme Shift Work. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_170713.pdf.

- Pega, F.; Náfrádi, B.; Momen, N.C.; Ujita, Y.; Streicher, K.N.; Prüss-Üstün, A.M.; Descatha, A.; Driscoll, T.; Fischer, F.M.; Godderis, L.; et al. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 154, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barger, L.K.; Weaver, M.D.; Sullivan, J.P.; Qadri, S.; Landrigan, C.P.; A Czeisler, C. Impact of work schedules of senior resident physicians on patient and resident physician safety: nationwide, prospective cohort study. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyman, M.G.; Huynh, R.; Owers, C. The European Working Time Directive: Will Modern Surgical Training in the United Kingdom Be Sufficient? Cureus 2022, 14, e21797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogun, S.; Ubom, A.; Adesunkanmi, A.; Ugowe, O.; Idowu, A.; Mogaji, I.; Nwigwe, N.; Kolawole, O.; Nwebo, E.; Sanusi, A.; et al. Nigerian Resident Doctors' Work Schedule. Niger. J. Clin. Pr. 2022, 25, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibullah, A.; Muhammad, M.A.; Kabiru, M.; Kabiru, M.D.; Abdulfatai, T.B. Predictors of stimulants use among physicians in a Nigerian tertiary health institution in Sokoto, Northwest Nigeria. J. Neurosci. Behav. Heal. 2018, 10, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokaya, A.G.; Mutiso, V.; Musau, A.; Tele, A.; Kombe, Y.; Ng’ang’a, Z.; Frank, E.; Ndetei, D.M.; Clair, V. Substance Use among a Sample of Healthcare Workers in Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2016, 48, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philibert, I.; Chang, B.; Flynn, T.; Friedmann, P.; Minter, R.; Scher, E.; Williams, W.T. The 2003 Common Duty Hour Limits: Process, Outcome, and Lessons Learned. J. Grad. Med Educ. 2009, 1, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zee, P.C.; Abbott, S.M. Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2020, 26, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).