1. Introduction

Water is a crucial medium for human exploration and research, covering approximately 71% of Earth’s surface. Underwater video recording plays a vital role in marine biology research, underwater archaeology, and ecological surveys [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, due to the physical properties of water, such as light absorption, scattering, suspended particles, and other factors,underwater videos typically suffer from poor visibility, color distortion, and low contrast [

5], which significantly hinder their practical applications. Traditional underwater video enhancement methods primarily rely on image processing algorithms to enhance each frame independently. While these methods have achieved some success in improving video quality, they face several key challenges. First, processing each frame independently ignores the inherent temporal continuity and style consistency between frames in a video, which may lead to temporal artifacts and inconsistent enhancement effects. The emergence of UVEB [

6] provides a large-scale (4K) high-resolution underwater video enhancement dataset and introduces UVE-Net, which converts current frame information into convolution kernels and passes them to adjacent frames to achieve effective inter-frame information exchange. However, the UVE-Net model is massive, requiring substantial computational resources and parameters, resulting in slow training processes and limited practical applications.

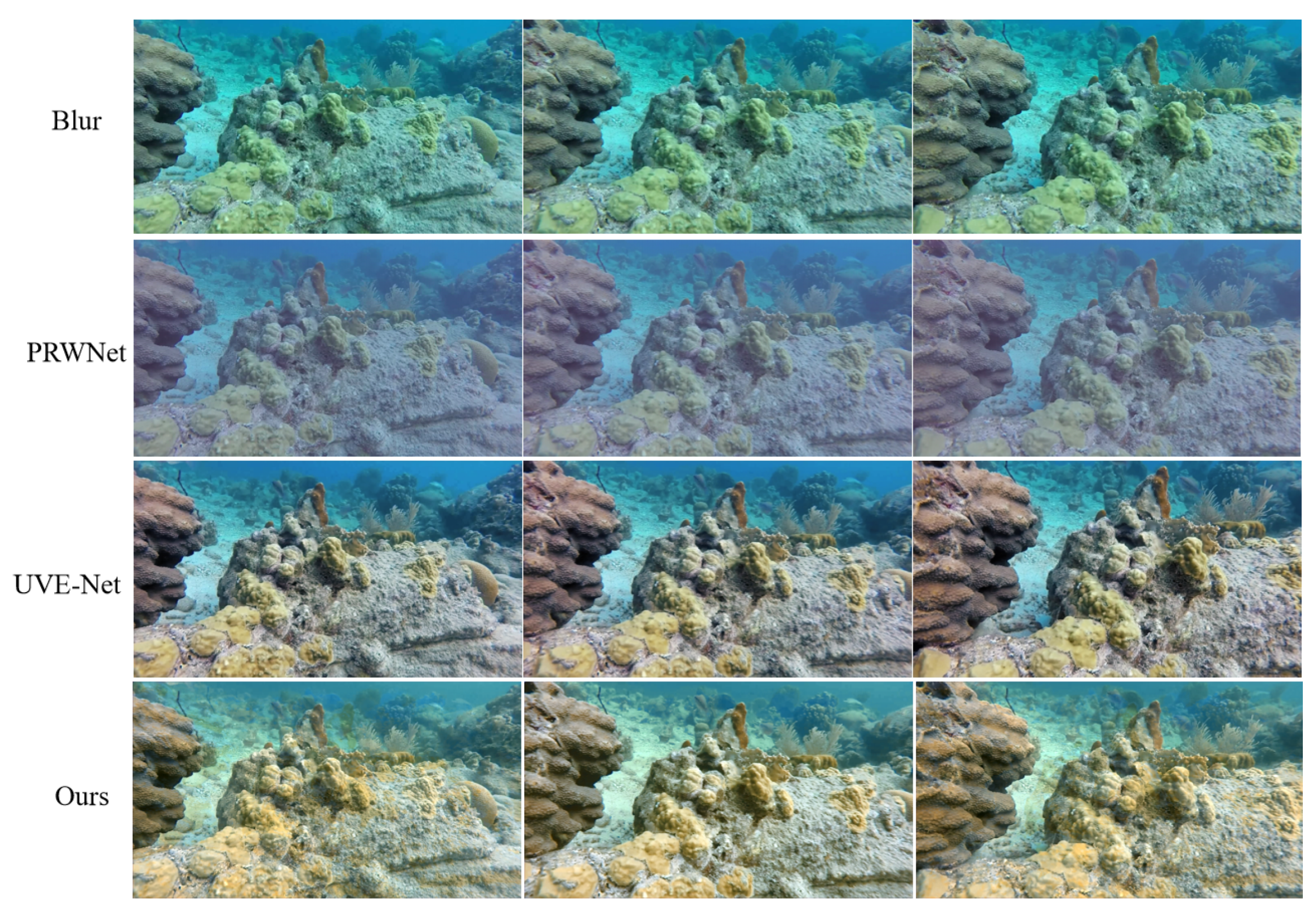

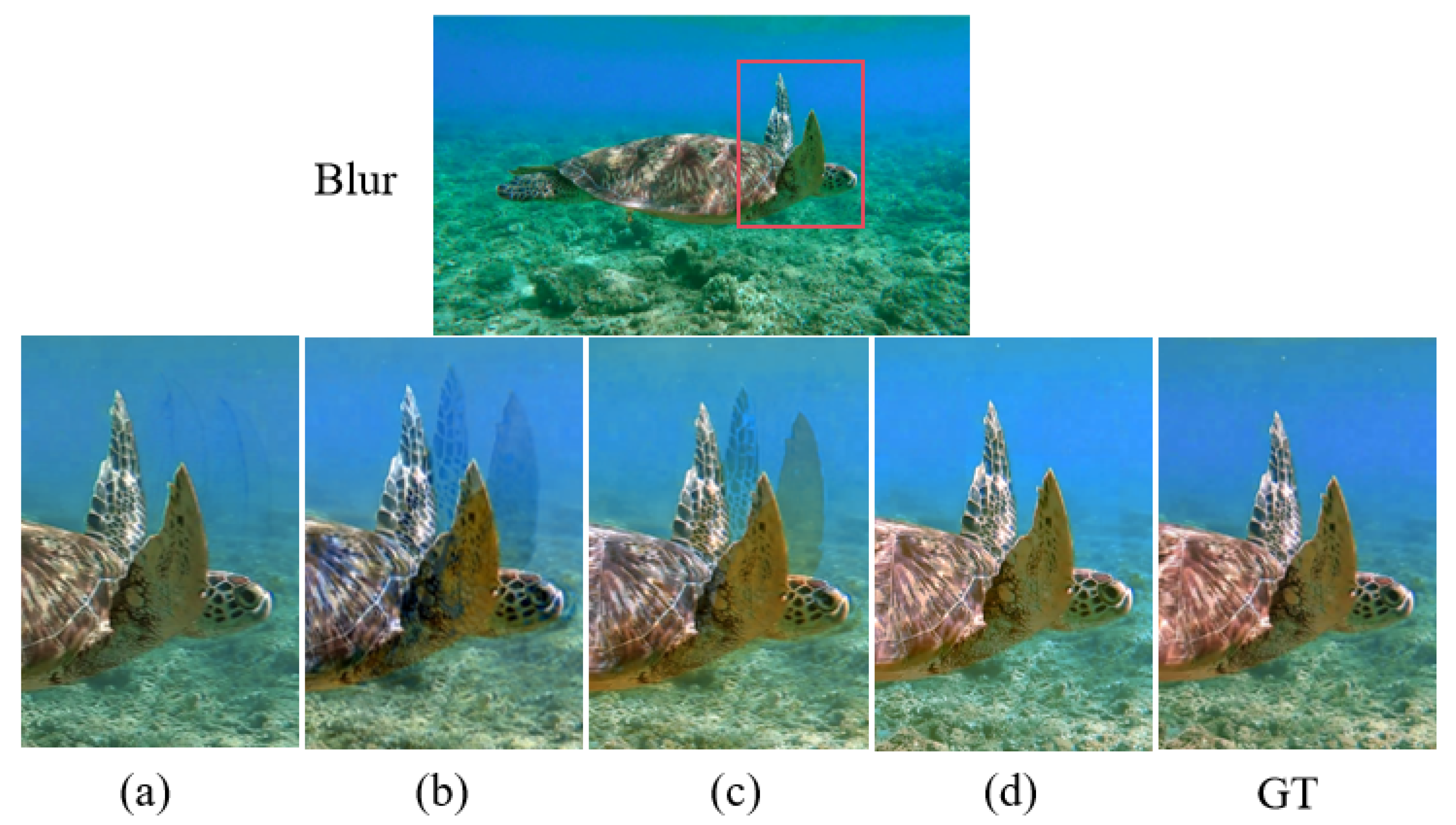

To address these limitations, we propose a novel underwater video enhancement framework that efficiently processes video sequences while maintaining temporal coherence. Our method introduces a dual-channel mechanism that first divides long video sequences into multiple shorter image sequences for input. For each image sequence, we extract the middle frame and enhance it using multi-scale and multi-channel attention mechanisms. The multi-channel processing better extracts image color features for enhancement, while multi-scale processing captures image details at different scales to enhance image detail enhancement. After enhancing the middle frame of the image sequence, the enhancement effect is propagated to adjacent frames through two complementary pathways. The effectiveness of our dual-channel mechanism is demonstrated in

Figure 1, where we compare our method against existing approaches (UVE-Net [

1] and PRWNet [

7]) on a challenging underwater scene. As shown, our method better preserves the natural color and detail of underwater structures while effectively removing blur and color distortion present in the original frames.

In DUVE-Net,the first pathway is the residual-based repair pathway. Within the same short image sequence, frames exhibit temporal continuity and style consistency, so the enhancement effects needed for other frames share similarities with the enhancement effects obtained from the middle frame. Therefore, the enhancement effects needed for other frames can be derived from the middle frame’s enhancement effects through inter-frame relationships. By calculating the difference between the enhanced and original middle frame, we obtain the enhancement effect residual of the middle frame. Considering the differences between frames, we calculate the inter-frame residual by comparing the middle frame with remaining adjacent frames. By applying convolution to the inter-frame residual as weight parameters for the middle frame’s enhancement effect residual, we can obtain independent enhancement effects for each frame, which can be added to the corresponding original frames to achieve enhanced results. The residual-based repair pathway effectively transmits the enhancement effects of the middle frame.

The second pathway is the convolution-based repair pathway, which generates adaptive convolution kernels from the enhanced middle frame to process the original adjacent frames. Each original frame independently uses the enhanced middle frame to generate convolution kernels for convolution, allowing the middle frame’s detail information to be transmitted to each frame. This design achieves effective inter-frame information transfer. The convolution-based repair pathway focuses more on the details in the enhancement effect transmission, reducing the impact of inter-frame differences.

The main contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

1. We propose a novel underwater video enhancement framework that explicitly considers inter-frame relationships, ensuring temporal consistency in enhancement results.

2. We introduce a dual-channel mechanism combining residual-based repair pathway and convolution-based repair pathways, which effectively propagates enhancement information from middle frames to adjacent frames.

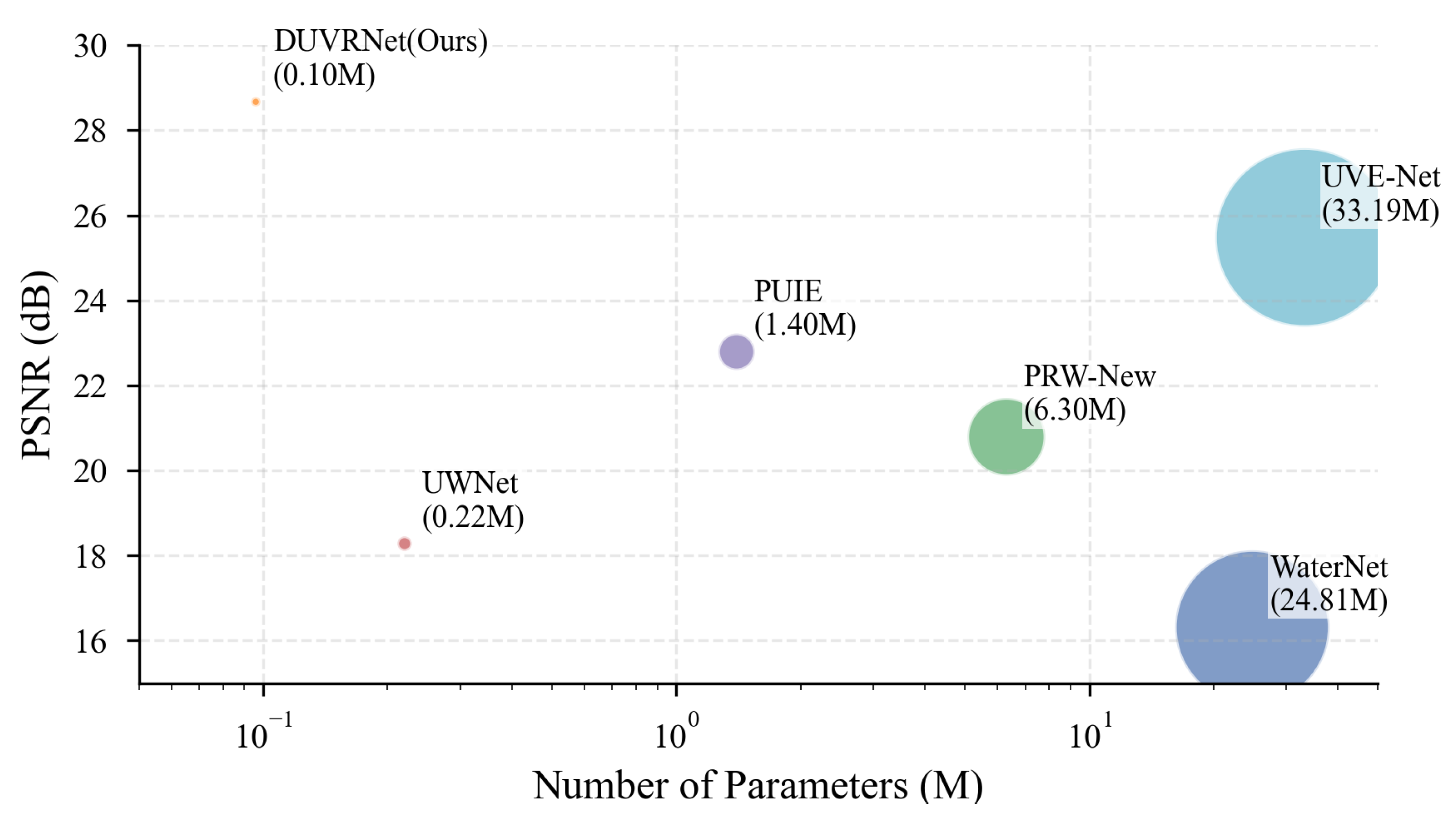

3. Our method achieves remarkable parameter efficiency, requiring only

parameters while maintaining high-quality enhancement effects for 4K underwater videos.As shown in

Figure 2, our DUVR-Net achieves superior PSNR performance with significantly fewer parameters compared to existing methods.

4. Extensive experiments on real underwater videos demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in terms of both visual quality and computational efficiency.

2. Related Work

2.1. Underwater Image Enhancement Methods

Underwater Image Enhancement methods can be broadly categorized into physical model-based methods, physical model-free methods, and deep learning-based methods. Physical model-based methods construct models by considering image degradation factors in specific environments, thereby reversing or compensating for degradation effects and improving image quality [

8,

9,

10]. Physical model-free methods directly adjust image pixel values through histogram equalization [

11] and color balance, bypassing the complex optical propagation models to enhance underwater images through direct manipulation of pixel intensity distributions and color characteristics. With the successful application of deep learning in computer vision tasks, various innovative architectures have emerged. Notable networks include WaterNet [

12], which employs adaptive filters [

13] and CNNs [

14] for quality improvement; Ucolor [

15], which utilizes medium transmission-guided multi-color space embedding; and FA+Net [

16], which incorporates color enhancement and pixel attention modules. Transformer-based [

17] solutions such as U-shape [

18] have also demonstrated excellence in capturing global features and handling long-range dependencies. Recent lightweight networks developed based on generative adversarial networks, such as FspiralGAN10 [

19], are more suitable for resource-constrained environments. Although these networks have made significant progress, challenges still persist in color distortion correction, texture preservation, and computational efficiency. In the field of UIE, balancing quality and efficiency remains a more critical issue.

2.2. Underwater Video Enhancement Methods

Early underwater video enhancement methods primarily extended single-frame image enhancement algorithms to video processing through frame-by-frame processing. Although some methods improved efficiency through fast filtering algorithms or lightweight deep networks, this independent frame processing often led to temporal artifacts and inter-frame flickering. To address these issues, researchers began exploring temporal relationships between frames. For instance, Ancuti et al. [

20] introduced temporal bilateral filtering to achieve inter-frame smoothing, while Li et al. [

21] extended video dehazing algorithms to underwater scenarios. Qing et al. [

22] proposed a spatiotemporal information fusion method to estimate consistent transmission maps and background light.Meanwhile, recent advances in video restoration have provided new insights for underwater video enhancement. Researchers have proposed various models to capture inter-frame relationships and aggregate temporal information, including optical flow estimation, deformable convolutions, and cross-frame attention layers. Notable examples include Shift-Net14 [

23], which introduces grouped spatiotemporal displacement to implicitly capture inter-frame correspondences, and UVE-Net [

2], which innovatively transforms frame information into convolution kernels for efficient inter-frame information exchange. Inspired by these approaches, we propose DUVR-Net, a dual-path method that simultaneously utilizes residual compensation and transformative convolution kernels for underwater video enhancement.

3. Methods

3.1. Overview of DUVR-Net

The input to DUVR-Net consists of consecutive frames

from an underwater video, where t denotes the index of the middle frame, and

represents the total number of input frames. The output of DUVR-Net comprises enhanced consecutive underwater video frames

. The operation of DUVR-Net can be formulated as shown in Equation (

1):

and

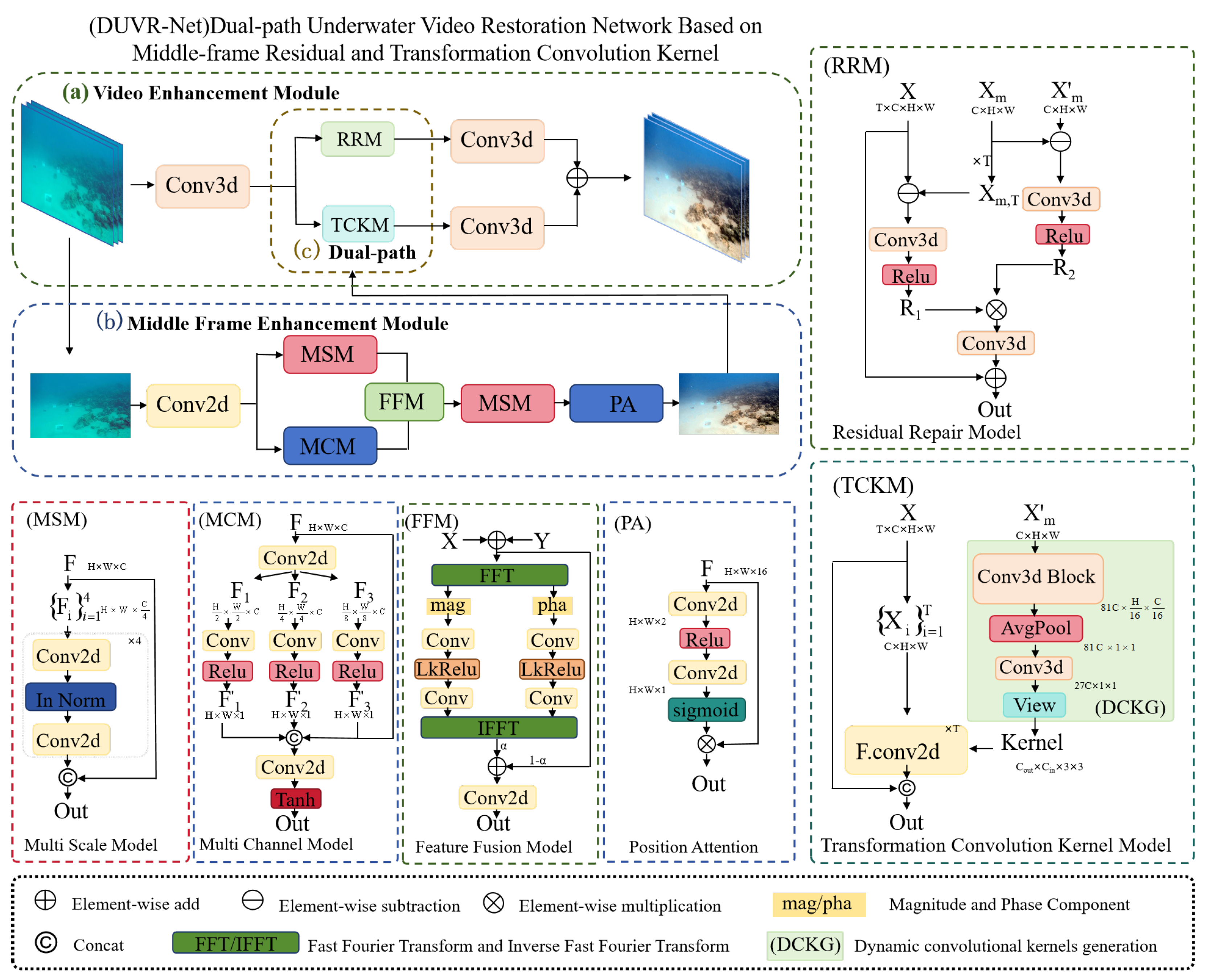

denote the original low-quality underwater videos and their corresponding enhanced versions, respectively.The overall architecture of DUVR-Net is illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.2. Middle Frame Enhancement Module

The Middle Frame Enhancement Module primarily focuses on enhancing individual middle frames, with its network architecture specifically designed for image-mode enhancement. To address the challenges of contrast deficiency and color distortion during the enhancement process, we adopt the enhancement strategy from FA+Net [

16], implementing a dual-branch enhancement mode comprising multi-channel and multi-scale pathways during middle frame enhancement. The multi-channel branch transforms the input into features with varying channel dimensions to better capture color feature distributions across RGB channels. In the multi-scale branch, the input is converted into features with different heights and widths, utilizing

convolutions to perform consecutive processing of individual image pixels, which not only reduces the parameter burden but also better captures color information for each pixel. The information fusion of the dual branches is accomplished through Inverse Fourier Transform [

24], with a hyperparameter

controlling the fusion ratio between spatial and frequency domain information.Subsequently, the fused features undergo fine-grained enhancement through the serial application of multi-scale modules and spatial attention mechanisms, ultimately producing the enhanced middle frame.

3.3. Video Enhancement Module

The video enhancement module takes as input a sequence of consecutive frames from a short underwater video, along with their corresponding enhanced high-quality intermediate frame. The output is the enhanced consecutive underwater video frames corresponding to this input sequence.The enhancement is achieved by propagating information from the enhanced middle frame to the remaining frames through residual and Transformation convolution kernels.

3.3.1. Residual Repair Model

The Residual Modification Model (RMM) aims to extract the enhancement effects obtained from the middle frame and modify these effects according to the differences between each frame and the middle frame, subsequently applying the modified results to the input frame sequence. The RMM takes as input both a consecutive frame sequence requiring enhancement and its enhanced middle frame. By extracting, customizing, and propagating the enhancement effects instead of enhancing each frame individually, this approach significantly reduces the model’s computational complexity and parameter count.

The key operations of RMM are as follows, given the feature and the enhanced middle frame derived from .

Middle frame enhancement residual(

) extraction:

Inter-frame residual(

) calculation:

Residual modulation(

),⊙ represents Element-wise multiplication:

Enhancement effect integration:

In summary, the complete processing of RMM can be expressed as:

3.3.2. Transformation Convolution Kernel Model

The transformation convolution kernel converts the enhanced intermediate frame into a 3×3 convolution kernel through Dynamic Convolution Kernels Generation (DCLG) and applies convolution operation to the current frame, thereby obtaining information from the enhanced intermediate frame and achieving inter-frame information transfer.The process of TCKM can be expressed as:

where

represents the features of the input consecutive frames.

represents the enhanced middle frame derived from

.

represents convolution.

3.4. Loss Function

We calculate the loss of the middle frames and video as the total loss function

:

where

refers to Charbonnier Loss [

25],

refers to Perceptual Loss [

26],

refers to

Loss [

27].

is the GT of sample

, and

is the GT of

.

is a weighting parameter that controls the contribution of video-related losses, and its value increases as the number of epochs grows.

4. Results

4.1. Settings

4.1.1. Dataset

We used the large-scale high-resolution Underwater Video Enhancement Baseline (UVEB) [

2] released on July 7, 2024, as our data source. The UVEB dataset comprises videos from multiple countries, encompassing various scenes and video degradation types to accommodate diverse and complex underwater environments. Due to the extensive size of the UVEB dataset, we utilized the first 150 pairs of video sequences in our experiment, consisting of 150 source videos and 150 target videos. By extracting one frame every six frames, we obtained a total of 16,836 images, including 8,418 source image sequences and 8,418 target image sequences. The ratio of training set to test set was set at 9:1, resulting in 7,563 images for training and 855 images for testing.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

Our experiments are implemented using the PyTorch [

28] framework with two NVIDIA Tesla V100-SXM2-16GB GPUs. We use an ADAM optimizer for network optimization. The initial learning rate is set to

. The total number of epochs is 100. The batch size is 4, and the patch size of input video frames is 512×512, with each sequence containing either 3 or 5 frames.

4.2. Comparisons with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.2.1. Quantitative Comparison

In quantitative measurement, we use peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), structural similarity index (SSIM), and mean square error (MSE) [

29] as metrics for image quality. Floating point operations (FLOPs) [

30] and parameter count (Params) [

31] serve as indicators of model efficiency and performance. From these quantitative results, our method outperforms others in terms of image quality. As shown in

Table 1, for 4K video, our model uses the minimal computational and parameter resources, in the same order of magnitude as FA+Net, which has the smallest model size in image processing tasks. DUVRNet has only 1/350 of the parameter count of UVE-Net while improving the PSNR metric by 3.19dB, demonstrating the superiority and feasibility of this algorithm

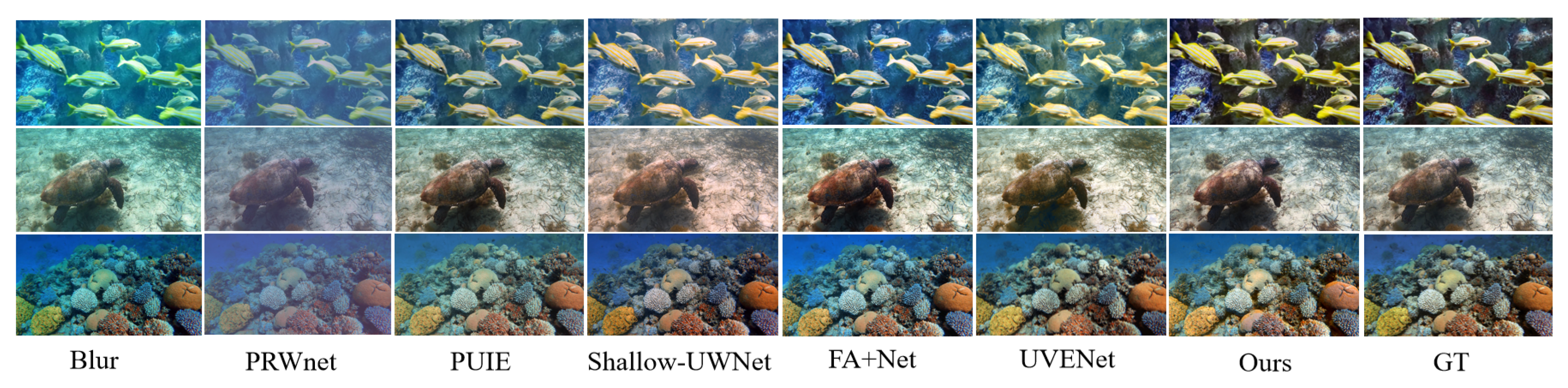

4.2.2. Qualitative Comparison

As shown in

Figure 4, we visually compared our network enhancement results with other methods. Due to its simple network structure, PRW-Net cannot adequately restore underwater images, resulting in enhanced images with low saturation. The enhancement results presented by PRW-Net appear unnatural in color and generally too dark. In contrast, our method demonstrates superior ability in removing color distortion while restoring appropriate brightness levels.

4.3. Ablation Studies

4.3.1. Effectiveness of Middle Frame Enhancement Module

To explore the impact of the middle frame enhancement module on the entire network, we replaced it with a residual neural network and examined the effects of this substitution. As shown in

Table 2, MFEM represents the Middle Frame Enhancement Module in the model. Comparing columns (a) and (d) in the

Table 2, MFEM enables the network to achieve better quality improvement with fewer parameters. Additionally, as demonstrated in

Figure 5, our implemented MFEM exhibits superior capability in recovering color and brightness information in the images.

4.3.2. Effectiveness of RRM and TCKM

The results in columns (b), (c) and (d) of

Table 2 verify the effectiveness of RRM and TCMK. From columns (b) and (d), we observe that the introduction of the RRM module not only reduces the MSE from 1.935 to 0.882 but also accelerates the inference time. The visual results in

Figure 5 demonstrate that the absence of RRM and TCKM modules may lead to imprecise enhancement effects, resulting in artifacts such as ghosting and color distortion. The incorporation of both RRM and TCKM modules contributes to faster and better enhancement performance.

5. Discussion

Compared to traditional frame-by-frame processing methods, DUVR-Net not only has a smaller model parameter count but also demonstrates the capability to process 4K videos. The model shows considerable potential in practical applications such as marine research and underwater archaeology. It can provide high-quality input for downstream tasks like underwater object detection.Although DUVR-Net is specifically tailored for underwater videos, its network architecture is still based on image enhancement networks. The dual-channel mechanism primarily functions to propagate image enhancement effects to adjacent frames. Therefore, in specific scenarios (such as scenes with intense motion), there might be certain limitations. Future work will focus on incorporating other advanced technologies (such as adaptive parameter adjustment) to make the model more adaptable to multi-environmental tasks. Additionally, attention will be paid to optimizing the enhancement strategy for intermediate frames.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we present DUVR-Net, a lightweight model for 4K underwater video enhancement that aims to overcome the limitations of previous frame-by-frame enhancement methods. Our approach employs a dual-channel strategy that effectively reduces computational complexity by separately transmitting enhanced color content with attention mechanisms and restored details. DUVR-Net currently has the smallest parameter count among underwater video enhancement models, while experiments validate its superior performance in underwater video enhancement tasks. We believe that DUVR-Net provides new design concepts and directions for underwater video enhancement, with practical applications in marine research and underwater archaeology.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, X.C. and Y.W.; methodology, X.C., Y.W. and T.W.; validation, Y.W., J.L. and Y.Y.; data curation, X.C. and K.-T.L.; writing original draft preparation, X.C. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, X.C., Y.W. and Y.G.; visualization, Y.Y. and T.W.; supervision, X.C. and Y.G.; project administration, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Science and Technology Project: Industrial Foresight and Key Core Technologies—Competitive Project under grant No. BE2022132.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to researchers from Ocean University of China and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology for providing Underwater Video Enhancement Benchmark.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UVEB |

Underwater Video Enhancement Benchmark |

| RRM |

Residual Repair Model |

| TCKM |

Transformation Convolution Kernel Model |

| MSM |

Multi Scale Model |

| MCM |

Multi Channel Model |

| FFM |

Feature Fusion Model |

| PA |

Position Attention |

| DCLG |

Dynamic Convolution Kernels Generation |

| MFEM |

Middle Frame Enhancement Module |

References

- Li, J.; Xu, W.; Deng, L.; Xiao, Y.; Han, Z.; Zheng, H. Deep Learning for Visual Recognition and Detection of Aquatic Animals: A Review. Rev. Aquacult. 2023, 15, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, A.; Lennon, M.; Thomas, N.; Gueguen, S.; Petit, T.; Lorho, T.; Hubert-Moy, L. Airborne Hyperspectral Imaging for Submerged Archaeological Mapping in Shallow Water Environments. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Myung, H.; Choi, H. T. Vision-Based Object Detection and Tracking for Autonomous Navigation of Underwater Robots. Ocean Eng. 2012, 48, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K. L.; Chow, J. S.; Hope, A.; Quinzin, M. C.; Cantner, K. A.; Amon, D. J.; McClain, C. R. Low-Cost, Deep-Sea Imaging and Analysis Tools for Deep-Sea Exploration: A Collaborative Design Study. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 873700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W. Underwater Vision Enhancement Technologies: A Comprehensive Review, Challenges, and Recent Trends. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 3594–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kong, L.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Z.; Yu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, B. Uveb: A Large-Scale Benchmark and Baseline Towards Real-World Underwater Video Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024; pp. 22358–22367. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, F.; Li, B.; Zhu, X. Efficient Wavelet Boost Learning-Based Multi-Stage Progressive Refinement Network for Underwater Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021; pp. 1944–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Hu, E.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Xiong, H.; Liu, Y. Visibility Restoration for Real-World Hazy Images via Improved Physical Model and Gaussian Total Variation. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 18, 181708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Tan, J.; Li, Y. Multi-Purpose Oriented Single Nighttime Image Haze Removal Based on Unified Variational Retinex Model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 1643–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single Image Haze Removal Using Dark Channel Prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 33, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, A. S. A.; Isa, N. A. M. Underwater Image Quality Enhancement Through Integrated Color Model with Rayleigh Distribution. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 27, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, C.; Ren, W.; et al. An Underwater Image Enhancement Benchmark Dataset and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 29, 4376–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Fast Implementations of LMS Adaptive Filters. IEEE Trans. Acoust., Speech, Signal Process. 1980, 28, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. E. Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Anwar, S.; Hou, J.; Cong, R.; Guo, C.; Ren, W. Underwater Image Enhancement via Medium Transmission-Guided Multi-Color Space Embedding. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 4985–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ye, T.; Bai, J.; et al. Five A+ Network: You Only Need 9K Parameters for Underwater Image Enhancement. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08824. 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A. N.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Zhu, C.; Bian, L. U-Shape Transformer for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 3066–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Guan, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, P.; Zheng, H. Underwater Image Enhancement Based on a Spiral Generative Adversarial Framework. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 218838–218852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancuti, C. O.; Ancuti, C.; De Vleeschouwer, C.; Bekaert, P. Color Balance and Fusion for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 27, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Anwar, S.; Porikli, F. Underwater Scene Prior Inspired Deep Underwater Image and Video Enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 98, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Yu, F.; Xu, X.; Huang, W.; Jin, J. Underwater Video Dehazing Based on Spatial–Temporal Information Fusion. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 27, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheung, K. C.; See, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. A Simple Baseline for Video Restoration with Grouped Spatial-Temporal Shift. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023; pp. 9822–9832. [Google Scholar]

- Frigo, M.; Johnson, S. G. FFTW: An Adaptive Software Architecture for the FFT. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP’98; 1998; Vol. 3; pp. 1381–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Roth, S.; Black, M. J. A Quantitative Analysis of Current Practices in Optical Flow Estimation and the Principles Behind Them. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2014, 106, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016; pp 694–711.

- Zhao, H.; Gallo, O.; Frosio, I.; Kautz, J. Loss Functions for Image Restoration with Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2016, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Chintala, S. Pytorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A. C. Mean Squared Error: Love It or Leave It? A New Look at Signal Fidelity Measures. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2009, 26, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A. G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861. 2017.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Drews, P.; Nascimento, E.; Moraes, F.; Botelho, S.; Campos, M. Transmission Estimation in Underwater Single Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2013; pp. 825–830. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, A.; Swarnakar, A.; Mittal, K. Shallow-UWNet: Compressed Model for Underwater Image Enhancement (Student Abstract). In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2021; Vol. 35; pp. 15853–15854. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Ma, K. K. Uncertainty Inspired Underwater Image Enhancement. In European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022; pp 465–482.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).