1. Introduction

Rational design of catalytic surfaces is of paramount importance in heterogeneous catalysis and nanotechnology [

1,

2]. This is because the tailored design of adsorbate-surface systems can find applications in catalysis, nanotechnology and materials science [

3]. Particularly when these systems are composed of monoatomic adsorbates and the surface is made from transition and noble metals [

4]. Therefore the better understanding of possible surface structures of adsorbates on metal surfaces and the design of new material coatings, with particular surface termination and therefore tailored properties, is desirable in many fields [

5]. Thus far the understanding of adsorption on metal surfaces on the microscopic level has relied on computer models and DFT calculations to which experimentalist do not have readily accessibility [

6]. We have previously shown that physical molecular models can have some advantages with respect to computer models as the teacher, researcher or student can manipulate the physical molecular model in ways that is currently not possible in computer simulations [

7]. Perhaps, in the future there will be some computer models of catalytic surfaces where the structure of adsorbates can be altered during the course of the calculation by the influence of a user action. Such efforts are currently underway via virtual reality techniques [

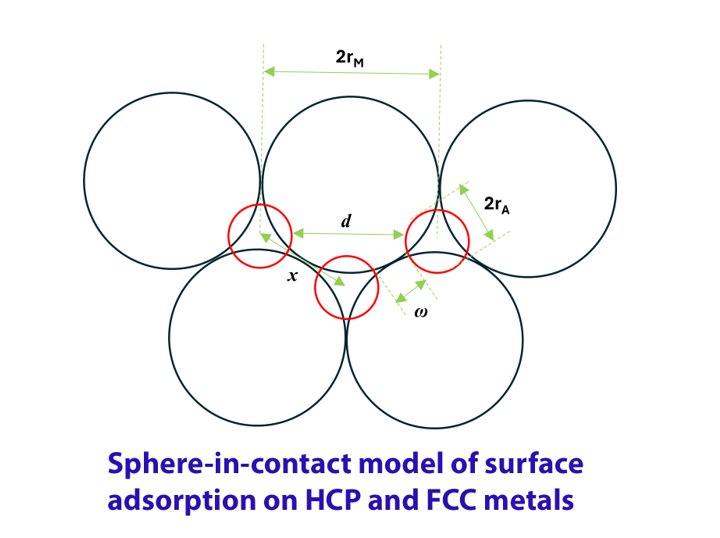

8]. Nevertheless, the use of inexpensive physical molecular models is desirable in research and education. For this reason we have used the sphere-in-contact model to study the structure of monoatomic adsorbates on the surface of close-packed metals.

The sphere-in-contact model is a molecular model in which the atoms are represented by their atomic radius [

9]. These spheres are in contact at a single point when there is a formation of a chemical bond between atoms. This model has been shown to have certain advantages over other molecular models such as the ball-and-stick model where the electron density volume of the molecular structure is underestimated. Also in the wireframe model (e.g. stick model) the volume that the electron density has is completely absent and we can only see the connectivity of the atoms. The other model broadly used in chemistry was developed by Robert Corey, Linus Pauling, and Walter Koltun and is called the space filling model (also known as CPK model) [

10]. In this model the atoms have their van der Waals (VdW) radius. This model is useful when we want to understand the packing of molecules in self-assembled molecular structures on surfaces, as the molecules or particles have the correct separation due to weak interactions such as London dispersion forces [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However it does not allow the proper modelling of doped materials as the void space in the structures is smaller than the actual space due to the electron density, which is correctly represented better in the sphere-in-contact model.

We have shown previously that the sphere-in-contact model can be used in research for example to understand the structure of carbon on curved surfaces, such as the hemispherical cap of carbon nanotubes [

7,

16]. It has also been used to reveal the molecular channels in rhombohedral graphite structures, which can find use as an X-ray radiation filter [

17]. We have also used sphere-in-contact models to model the complete reaction mechanism of heterogeneous catalytic reactions, where the adsorbates, the metal nanoparticle and the substrate are explicitly shown in miniature models of heterogeneous catalysts [

18]. When the sphere-in-contact model uses different radius for the atoms of structure then we can model almost anything with atomic precision. This could be organic molecules, organometallic complexes, biomolecules and doped materials. Additionally, it has also been used to understand the position of nanoparticles on metal close-packed surfaces [

18]. We have recently shown that sphere-in-contact models can be used to understand the number of (100) and (111) sites that a nanoparticle has on its exposed surface, when such NPs are deposited on flat hexagonal, trigonal and cubic surfaces of HCP and FCC lattices [

19].

In this study we show how the sphere-in-contact model can be used to model surface interactions during the adsorption of monoatomic elements (e.g. H, C, N, S, O) on hexagonal metal surfaces of HCP and FCC lattices. The question we address with these models is what are the possible structures of monoatomic adsorbates for a given surface coverage (θ) and which is the lowest energy configuration. This is a question with great interest in surface chemistry, heterogeneous catalysis and nanotechnology.

2. Materials and Methods

We have used marbles of different size and colour and a template that would hold the marbles in a hexagonal close packed structure. The marbles are transparent so that we can observe the underlying structure beneath the adsorbates, such as the three-fold hollow sites in FCC and HCP lattices and the four-fold hollow sites in HCP lattices. We used a different colour of the atoms in the metal surface and for the atoms in the adsorbate layer and a different radius for the spheres. The marbles have the natural tendency to arrange in a hexagonal close packed pattern by lateral repulsive interactions, which can be enforced by a lateral movement of the template frame. We have then added blue marbles of a different radius and let them obtain various surface structures by moving them manually with our hands. This process is not entirely dictated by the user-marble interaction but also by the adsorbate marble-marble interaction that in some cases results in a simultaneous movement of the marbles in a row. Also due to repulsion the adsorbates cannot reside in the nearest neighbhour three-fold hollow sites. This of course depends on the atomic radius of the adsorbate and smaller atoms such as hydrogen may actually reside at nearby 3-fold hollow positions.

As far as we know this modelling technique using spheres of different size to model surface adsorption phenomena through physical molecular models has not been previously published elsewhere.

The adsorbate surface coverage (θ) was calculated by the assumption that we have a full coverage (i.e. θ = 1) when each surface metal atom has one adsorbate atom bound to it. So the equation of surface coverage is,

3. Results and Discussion

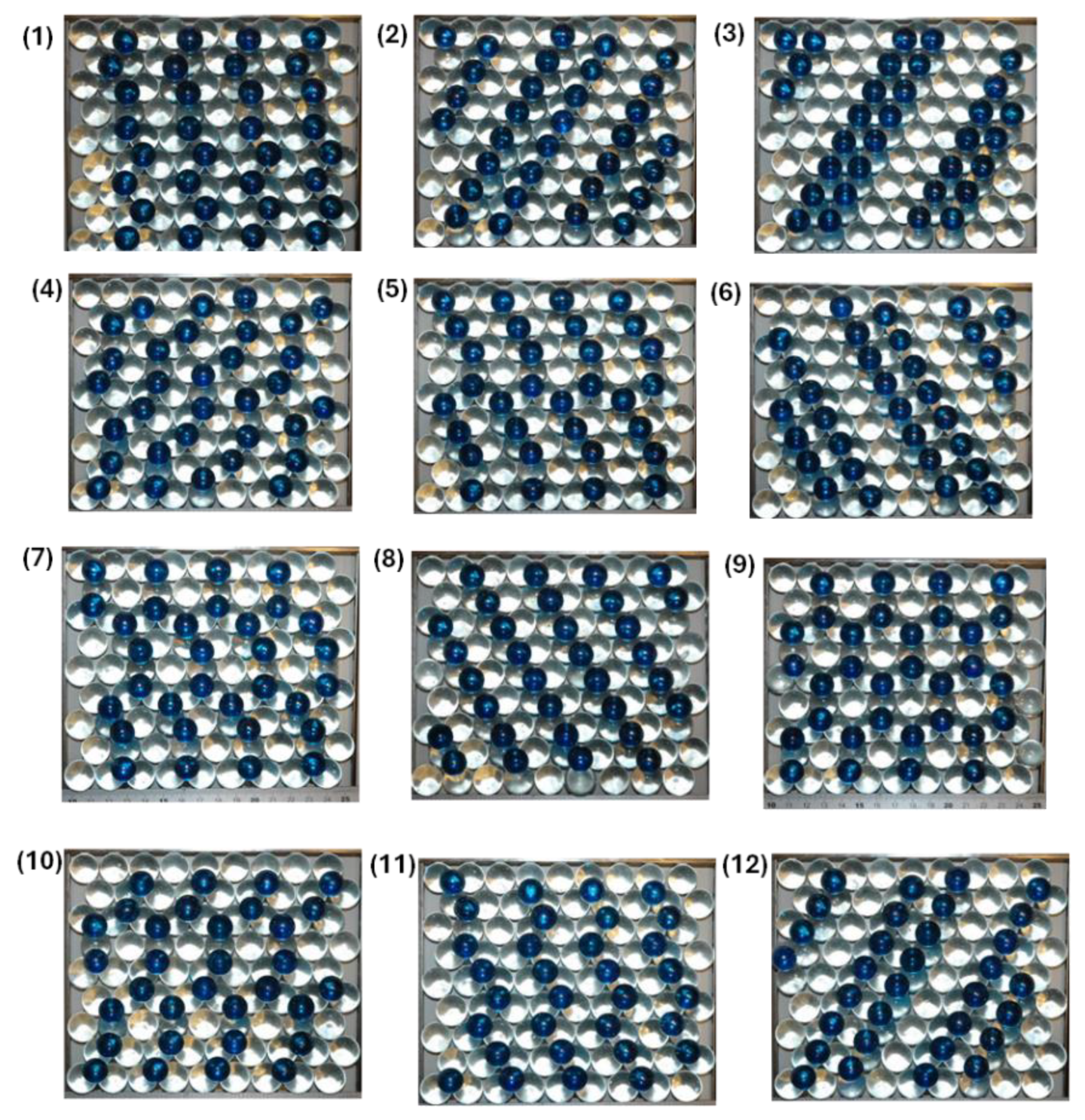

We have placed 81 colourless marbles in a rectangular template and allowed them to obtain their minimum energy configuration, which is a hexagonal closed packed structure. The sphere-in-contact models we have used are shown in

Figure 1. All these models have the same surface coverage which is θ = 0.39 ML. This hexagonal closed packed structure is the surface termination of both hexagonal closed packed (HCP) and face centered cubic (FCC) crystals. However, similar models can be built for the body centered cubic (BCC) structure. This means that all metals which have usually one of these three crystal structures can be modelled this way and the structure of adsorbates can be studied in an interactive way. Furthermore, steps and adatoms can be modelled within the sphere-in-contact model by adding a second layer of metal atoms or by adding an atom on the terrace of the metal surface, respectively. We have also prepared sphere-in-contact models with atom vacancies (e.g. defects). However, the adsorption at the surface defect is difficult to model with these models as the actual bonding is not present between these spheres and therefore some configurations such as bridge bonding can not hold the adsorbate in place. Therefore the modeling of adsorbates to vacancy sites has to rely on computer simulations primarily using density functional theory (DFT). However, these attributes suggest that this simplistic physical molecular model can help us in the study of most adsorbate – metal surface systems and it can have a great visual advantage over computer simulations when it comes to teaching the adsorption of monoatomic elements on the surface of metals and nanoparticles.

In some cases a whole row of adsorbates can move simultaneously and form a new surface configuration in these physical sphere-in-contact models. These adsorbate-adsorbate interactions and the way the adsorbate atoms move on the surface to obtain new low energy positions is educationally very interactive and a fast method of exploring many possible adsorbate surface configurations.

We note here that this model works better for the adsorption of adsorbates in three-fold hollow sites, which is also the site that has usually has the highest adsorption energy (e.g. the most exothermic adsorption energy) compared to bridged and atop adsorption, which is also a possibility especially when the adsorbate surface coverage increases and adsorbates are pushed due to repulsive interactions to these higher energy structures, that include both atop and bridged adsorption. We have previously studied the adsorption of CO on Pd nanoparticles and observed some of these trends in the adsorption energy of 3-fold-hollow being generally greater than the bridged and top CO bound to the surface of the NP [

20]. If the crystal termination is due to a BCC crystal then the strongest adsorption site is usually the four-fold hollow site followed by the bridged and the atop. These trends in adsorption energy we have previously shown are similar in large NPs that have well defined surfaces and in small transition and noble metal clusters. However the smaller clusters usually have more negative adsorption energies due to the unsaturated nature of the metal atoms on the cluster and the tendency to form stronger adsorbate metal bonds [

21].

It is therefore evident that this sphere-in-contact model is useful in understanding and presenting the adsorption of monoatomic adsorbates on the surface of metals. It can show the formation of various adsorbate adlayers with different adsorption configuration and long range ordering of monoatomic adsorbates on metal surfaces. It can also help in the study of surface diffusion of adsorbates in a way that it minimises the repulsive interactions between adsorbates.

The fact that we use a different atomic radius for the adsorbates and the metal atoms makes possible the measurement of the interatomic distances between the adsorbate atoms and calculate the repulsive interaction energy as a function of pairwise interactions using Coulomb’s law. These calculations follow in the subsequent section.

Analytical Equations of the Repulsive Interaction Energy of Monoatomic Adsorbates in the Sphere-in-Contact Model

Calculating the repulsive interaction energy in the sphere-in-contact model is possible by assuming that monoatomic adsorbates on the surface of a metal usually repel each other when they are adsorbed in nearby positions. Induced dipole – induced dipole interactions such as London dispersion forces will not be significant as the adsorbate atoms need to be in physical contact to have the appearance of such electron cloud polarization effects. These repulsions are due to the valence electron cloud of adsorbates that is partially negatively or positively charged and since there is not an attractive interatomic interaction between the adsorbates such as dipole-dipole, ion-dipole or ion-ion interactions the only interaction left to evaluate is the Coulombic interaction between negatively or positively partial charges on the surface of adsorbate atoms. This partial charge (δ) can be assumed to be smeared over the surface of a sphere with an atomic radius of the adsorbate atom. But to make the model of pairwise interactions even simpler we can assume that the partial negative charge or positive partial charges of the adsorbate atoms is at a point charge that is positioned at the nearest distance of the interacting adsorbate atoms. By making this assumption we can calculate the pairwise repulsive interaction energy as a summation of Coulomb terms that include all the surface adsorbates in a certain adsorption configuration of these adsorbates on the surface of HCP and FCC metals. As this interaction energy has a 1/r dependence it is fair to assume that it becomes realtivly small at distances that exceed the fourth nearest neighbour. Therefore in this sphere-in-contact model we include only pairwise interactions up to the third nearest neighbour. Additionally we model the adsorption at low surface coverages and this suggests that the monoatomic adsorbates will bind to three-fold hollow sites.

This simplification is based on empirical evidence concerning the adsorption of hydrogen and carbon dioxide on metal surfaces. On Pt(111) the adsorption of atomic hydrogen has been found to be the most exothermic on the three-fold hollow site with ΔG = -0.333 eV at θ = 1/16 ML compared to ΔG = -0.285 eV at bridge and ΔG = -0.255 eV at atop sites [22]. Additionally on detailed DFT simulations we performed on Pd NPs for CO adsorption we found that adsorption is more exothermic in the following order 3-fold hollow > bridge > atop. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that on metallic HCP and FCC surfaces the adsorption of adsorbates will start on three-fold hollow sites at low coverages and then move to bridge and atop sites as the coverage increases. Since the surface coverage used in our models was 0.39 ML it is valid to assume that the monoatomic adsorbates are bound to the 3-fold hollow site of hexagonal close packed metal surfaces.

Coulomb’s law for the force between interacting particles is

where F is the electric force (units = N), k is the Coulomb constant (8.988x10

9 Nm

2/C

2),

,

the point charges on the particles in C and r the distance of separation between the particles in m. As we will model the repulsive interaction between the adsorbates using a partial charge located at the nearest distance points of the adsorbates spheres this energy is more exothermic when the particle separation is small. The interaction energy (U) of Coulomb's law is given by,

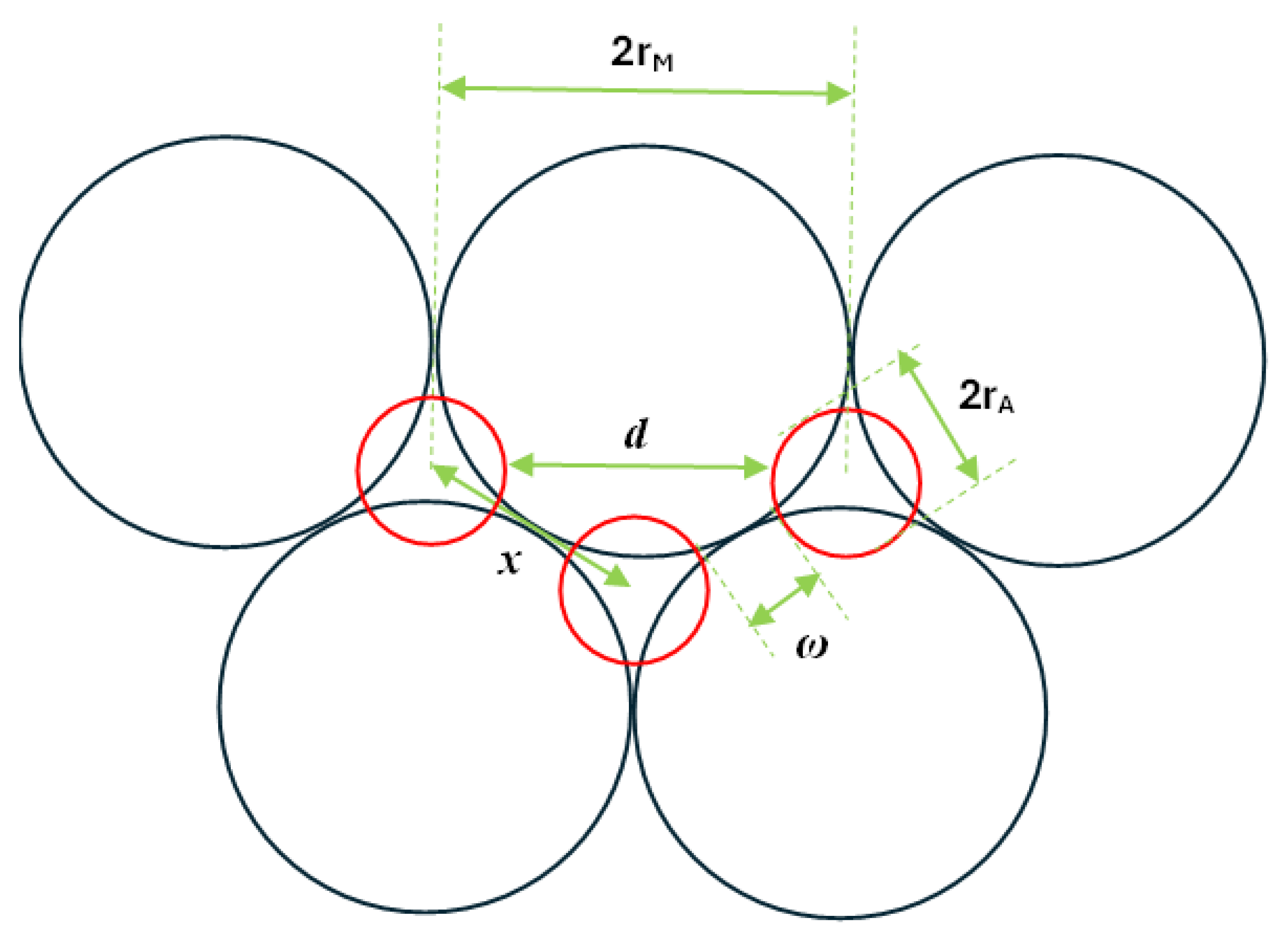

The pairwise interactions will be modelled this way with a summation of all interacting adsorbate particles that are in nearest neighbour, second nearest neighbour and third nearest neighbour three-fold hollow sites. When the point charges are assumed to be on the surface of the adsorbate spheres, at points that are defined by a line being the nearest distance between the adsorbate spheres, then the distance between the nearest neighbours is ω, d and φ, as shown in

Figure 2.

The energy of the repulsive Coulomb interaction energy will be proportional to how close the adsorbate spheres (i.e. atoms) are when they are located in 3-fold hollow sites. This provides the possibility of modelling surface adsorption on large surface unit cells with various adsorption configurations. These sphere-in-contact models can show very large scale ordering phenomena during the adsorption of monoatomic species on metal surfaces that are either hexagonal close packed (HCP) with a stacking sequence of ABABAB or face centered cubic (FCC) with a stacking sequence of ABCABC. Some metals that belong to these lattices are for HCP, Mg, Zn, Cd, Ti, Co, Be and Zr and for FCC, Au, Ag, Pt, Ir, Al, Cu, Ni and Pb, respectively.

Therefore the net repulsive Coulomb interaction energy is given by the summation of first, second and third nearest neighbour interactions between adsorbates adsorbed at the three-fold hollow sites of close-packed FCC and HCP metal surfaces given by,

Nearest distance between adsorbates in the second closest 3-fold hollow positions is given by,

where

is the radius of the metal atoms and

the radius of the adsorbate which is depicted in

Figure 2.

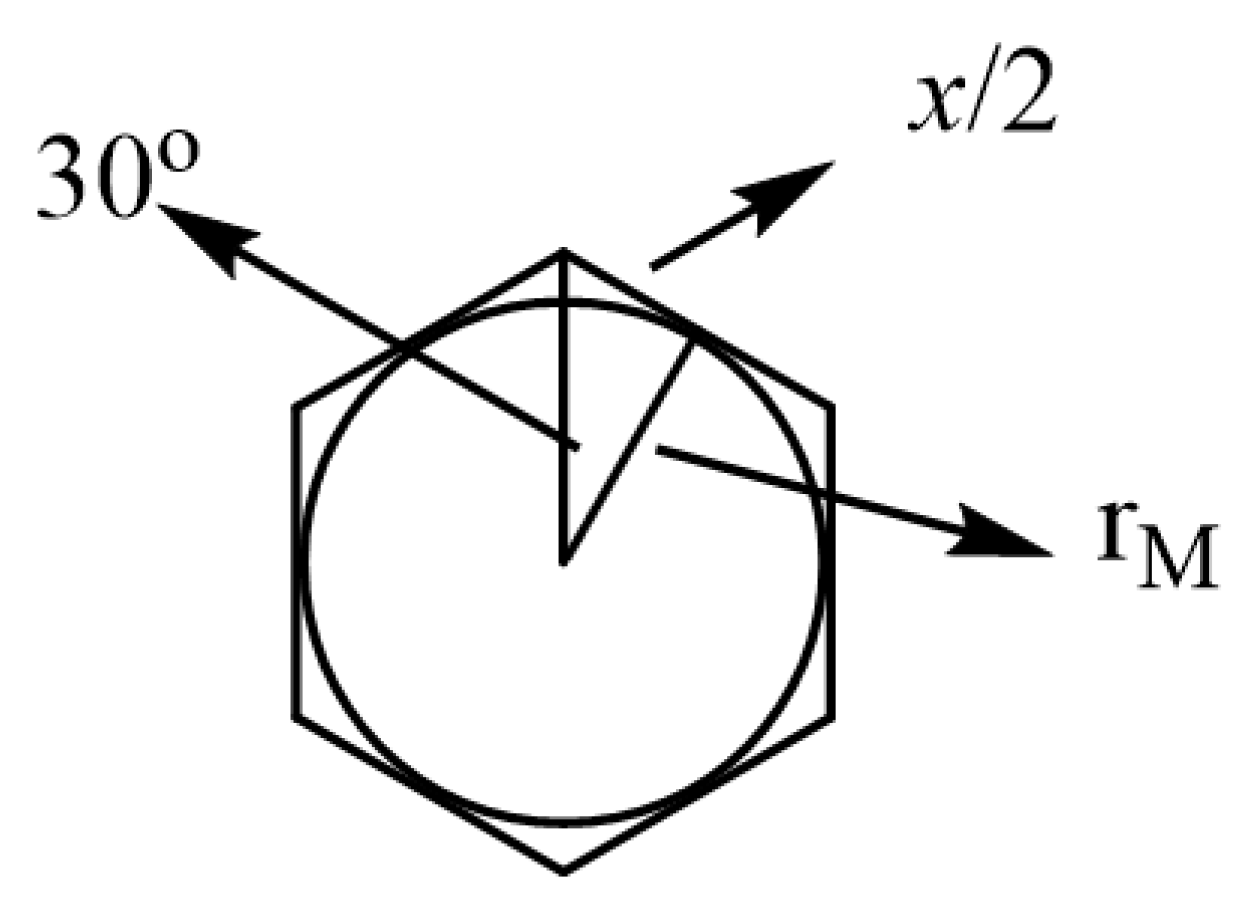

The centers of the adsorbate spheres in nearest neighbour sites has a distance of x. If you consider the six nearest neighbour distances that surround each metal atom, then these form a regular hexagon shown in

Figure 3.

The side of this hexagon is x and the distance from the center of the hexagon to the side of the hexagon is the radius of the metal atom,

. If you also consider the radius of the hexagon then this along with x/2 and

form a 30-60-90 triangle from which you can calculate x from the tangent of the 30° angle. This yields that

So the nearest neighbour distance between the surfaces of the spheres of adsorbates at 3-fold hollow sites of HCP and FCC crystals is given by

Therefore combining Eqns. 6 and 7 yields that the nearest neigbhour distance between adsorbates at three-fold hollows is,

The third nearest neighbour distance between adsorbates is given by the long diagonal of the regular hexagon in

Figure 3 the length of which can be calculated using Pythagoras theorem. So the distance between the point charges of third nearest neighbour adsorbates is given by,

This means that the relative pairwise repulsive interaction energy between adsorbates given from Eqns. 4, 5, 8 and 9 is,

In

Table 1 we evaluate the repulsive interaction energy of the various sphere-in-contact models shown in

Figure 1 using Eqn. 10. In the sphere-in-contact models of

Figure 1 the adsorbates have a radius

and therefore nearest neighbour adsorption is not observed in any of the models. However, second nearest neighbour and third nearest neighbour absorption is observed. The number of pairwise interactions for second (

v2) and third (

v3) nearest neighbour interactions is given in

Table 1 along with the repulsive interaction energy (

Unet) per 1 mol of adsorbates for adsorbates having partial charges of ±0.1 e and ±0.2 e.

As the coverage used in our sphere-in-contact models was θ = 0.39 ΜL therefore we only consider adsorption in the three-fold hollow sites as this is considered a surface coverage that precedes the adsorption of bridge and atop adsorption configurations usually.

Then by using a radius of the metal atom of

= 1.5 Å, the adsorbate

= 1.3 Å and a partial negative charge of ±0.1 e and ±0.2 e for

and

we can calculate using Eqn. 10 the repulsive interaction energy of different surface configurations of adsorbates in the 12 sphere-in-contact models in

Figure 1. The partial charge (δ) of each adsorbate can be positive or negative due to charge transfer to the metal but eitherwise it will result in a repulsive interaction energy between adsorbates. These analytical calculations reveal that surface 9 has the lowest energy configuration for monoatomic adsorbates at a θ of 0.39 ML. This is a surface configuration of the adsorbates with hexagonal symmetry in which all adsorbates are arranged at the third nearest neighbour adsorption sites. We suggest that this adsorption configuration should be sought for in surface imaging techniques (e.g. STM, AFM, LEED) in order to proof that long range ordering of monoatomic adsorbates on HCP and FCC metal surfaces is dictated by repulsive surface interactions between adsorbate atoms, which are minimised at the third nearest neighbour 3-fold hollow sites at coverages of 0.39 ML.

4. Conclusions

We have used the sphere-in-contact model to study the structure of monoatomic adsorbates on hexagonal close-packed surfaces of HCP and FCC metals. This model contains atoms of different radius and colour to represent the atoms of the metal surface and the adsorbate atoms. The study reveals that using this approach we can get the arrangement of the adsorbates on metal surfaces at various coverages and compare structures of different surface adsorbate configurations that were obtain for the same surface coverage. This has useful applications in an educational context but could also be used as a research tool. Using this approach we find that at a surface adsorbate coverage of θ = 0.39 ML monoatomic adsorbates will form a hexagonal surface adlayer in which the adsorbates are at the 3rd nearest neighbour 3-fold hollow sites. This can have useful implications in the use of such adlayers in technological applications such as coatings and arrays of magnetic atoms on surfaces. Furthermore, we anticipate that this approach will help teachers, researchers and students to visualize the structure of adsorbates on metal nanoparticles and surfaces in an experiential and practical way that allows real time manipulation and visualization of repulsive adsorbate-adsorbate interactions. The sphere-in-contact model allows the formation of adsorbate adlayers of different adsorption configurations in an interactive way exploring many possible surface configurations and evaluating which has the lowest energy by the use of analytical trigonometric equations and well established equations in physics.

Funding

This research received no external or internal funding.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Surfaces for covering the APC charge of the manuscript to make it available as open access.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare in this study

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ML |

Monolayer |

| HCP |

Hexagonal close packed |

| FCC |

Face centered cubic |

| BCC |

Body centered cubic |

| DFT |

Density functional theory |

| APC |

Article processing charge |

| STM |

Scanning tunneling microscopy |

| AFM |

Atomic force microscopy |

| LEED |

Low energy electron diffraction |

| NP |

Nanoparticle |

| CPK |

Corey-Pauling-Koltun |

| VdW |

Van der Waals |

References

- Wang, Z.; Hu, P. Rational catalyst design for CO oxidation: a gradient-based optimization strategy. Catalysis Science & Technology 2021, 11, 2604-2615. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheng, D.; Cao, D.; Zeng, X.C. Revisiting the universal principle for the rational design of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nature Catalysis 2024, 7, 207-218. [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Halldin Stenlid, J.; Abild-Pedersen, F. Electronic structure factors and the importance of adsorbate effects in chemisorption on surface alloys. Computational Materials 2022, 8, 163. [CrossRef]

- Sprunger, P.T.; Plummer, E.W. The Interaction of Hydrogen with Simple Metal Surfaces. Surface Science 1994, 307-309, 118-123.

- Comer, B.M.; Li, J.; F., A.-P.; Bajdich, M.; Winther, K.T. Unraveling electronic trends in O* and OH* surface adsorption in the MO2 transition-metaloxide series. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 7903.

- Raman, A.S.; Vojvodic, A. Energy Trends in Adsorption at Surfaces. In Handbook of Materials Modeling: Applications: Current and Emerging Materials, Andreoni, W., Yip, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 1321-1341.

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.L., E. Z. Study of the cap structure of (3,3), (4,4) and (5,5)-SWCNTs: Application of the sphere-in-contact model. Carbon 2017, 115, 819-827.

- Extremera, J.; Vergara, D.; Rodríguez, S.; Dávila, L.P. Reality-Virtuality Technologies in the Field of Materials Science and Engineering. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Pullman, D.P.; Catlow, C.R.A. The sphere-in-contact model of carbon materials. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2016, 22, 40. [CrossRef]

- Corey, R.B.; Pauling, L. Molecular models of amino acids, peptides, and proteins. Rev. Sci. Instr. 1953, 24, 621.

- Papadopoulou, A.; Laucks, J.; Tibbits, S. From Self-Assembly to Evolutionary Structures. Architectural Design 2017, 87, 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.; Song, F.; Nguyen, M.-T.; Stöhr, M. Self-assembly of pyrene derivatives on Au(111): substituent effects on intermolecular interactions. Chemical Communications 2014, 50, 14089-14092. [CrossRef]

- Bezryadin, A.; Westervelt, R.M.; Tinkham, M. Self-assembled chains of graphitized carbon nanoparticles. Applied Physics Letters 1999, 74, 2699-2701. [CrossRef]

- Hubmann, A.H.; Dietz, D.; Brötz, J.; Klein, A. Interface Behaviour and Work Function Modification of Self-Assembled Monolayers on Sn-Doped In2O3. Surfaces 2019, 2, 241-256. [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, T.; Blanco, M.; Granozzi, G.; Wandelt, K. Potential Driven Non-Reactive Phase Transitions of Ordered Porphyrin Molecules on Iodine-Modified Au(100): An Electrochemical Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (EC-STM) Study. Surfaces 2018, 1, 12-28. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Loizidou, E.Z. Corrigendum to “Study of the cap structure of (3,3), (4,4) and (5,5)-SWCNTs: Application of the sphere-in-contact model” [Carbon 115 (2017) 819–827]. Carbon 2019, 146, 369-370.

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Pullman, D.P. Study of a rhombohedral graphite X-ray filter using the sphere-in-contact model. Chemical Physics Letters 2019, 734, 136717. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Pullman, D.P. Miniature physical sphere-in-contact models of heterogeneous catalysts and metal nanoparticles. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2023, 29, 312. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D. A study using physical sphere-in-contact models to investigate the structure of close-packed nanoparticles supported on flat hexagonal, square and trigonal lattices. Chemical Physics 2024, 588, 112464. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Willock, D.J.; Thomas, L.; Wilson, K.; Lee, A.F. CO adsorption over Pd nanoparticles: A general framework for IR simulations on nanoparticles. Surface Science 2016, 646, 210-220.

- Zeinalipour-Yazdi, C.D.; Cooksy, A.L.; Efstathiou, A.M. CO adsorption on transition metal clusters: Trends from density functional theory. Surface Science 2008, 602, 1858-1862. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).