1. Introduction

Cannabis (

Cannabis sativa L.), belonging to the

Cannabaceae family, represents a perennial flowering herb that is indisputably regarded as one of the most ancient plants cultivated and utilized by humans for a multitude of applications, encompassing nourishment, textiles, and pharmacological remedies [

1].

The potential economic and ecological sustainability of cannabis as a crop depends on extensive research into operational methodologies. Traditionally, the scope of research has been limited by legislative restrictions. Recent changes in laws across various regions are now paving the way for more comprehensive studies. These could lead to new insights into cannabis cultivation techniques.

For most of the plants, environmental stresses, particularly drought, significantly hinder plant growth and agricultural productivity due to climate change. Drought stress is identified as a major abiotic stress that adversely affects various physiological processes in plants, including leaf growth, enzyme activity, and photosynthetic efficiency, ultimately leading to reduced productivity [

2].

It is noted that all stages of plant development, from germination to maturity, can be affected by drought stress, influenced by factors such as species and environmental conditions. The physiological response of plants to drought conditions is a complex phenomenon influenced by various factors, and it encompasses the signaling pathways mediated by abscisic acid (ABA) along with several downstream regulatory mechanisms such as stomatal closure, cuticle thickening, and the production of specialized metabolites [

3,

4].

During the vegetative phase, water stress significantly impacts biomass accumulation in hemp, leading to reduced plant height, leaf expansion, and stem diameter, particularly affecting fiber quality. It also alters chemical composition, decreasing cellulose content and increasing lignification. Drought can reduce hemp biomass production by up to 45% and results in changes to plant architecture, characterized by shorter internodes and less lateral branching [

5].

The reproductive phase is highly sensitive to drought, leading to various effects such as delayed or early flowering, reduced inflorescence size and quantity, decreased pollen production in males, increased flower abortion in females, and changes in cannabinoid and terpene content [

6]. In dioecious varieties, drought can affect the male-to-female plant ratio, impacting seed production. Moderate water stress during flowering may enhance bioactive compound concentrations [

6]. During seed filling and maturation, drought can significantly reduce seed quantity and size, alter chemical composition, and decrease seed viability and vigor. Water stress can also lower oil content in hemp seeds by 15-20% and change essential fatty acid proportions [

7].

Water stress during the flowering phase of cannabis significantly alters the plant’s secondary metabolism, affecting the biosynthesis and accumulation of cannabinoids [

6]. This is crucial for crops aimed at producing inflorescences rich in bioactive compounds for medical and industrial uses. Under drought conditions, hemp increases the production of protective compounds, such as volatile terpenes that lower leaf temperature [

8], flavonoids with antioxidant properties, and specific secondary metabolites that enhance stress resistance [

9]. These adaptations result in notable changes in the cannabinoid profile and concentration in hemp [

10,

11].

Moderate water stress during flowering can enhance cannabinoid concentrations in cannabis plants, particularly Cannabidiol (CBD). Researches shown that maintaining substrate moisture at 60-70% of field capacity can increase CBD levels by 12-15% due to improved gene expression and a consequent greater production of trichomes [

6]. However, severe water stress (below 40% field capacity) negatively affects CBD concentrations by inhibiting plant metabolism [

12].

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) responses to water stress vary by genotype, with moderate stress potentially increasing THC levels by 8-20%, and some varieties showing increases up to 25% [

6]. Moderate stress also raises the THC:CBD ratio, favoring THC production [

9]. In industrial hemp with low THC levels, prolonged water stress may cause THC concentrations to exceed legal limits [

13].

Water stress also significantly affects the production of minor cannabinoids and terpenes in plants [

14]. The terpene profile can change with an increase in volatile monoterpenes (myrcene, limonene, pinene) and enhanced sesquiterpenes (beta-caryophyllene, α-humulene) when subjected to moderate stress [

15]. It must be remembered that altered relationships between terpene classes strongly affect organoleptic properties and potential pharmacological effects [

16].

Understanding the impact of water availability on plant performance and phytochemical composition is crucial for improving cultivation methods, particularly in controlled-environment agriculture and medicinal cannabis production. This study aims to identify key phases where water stress most significantly affects yield and cannabinoid production, offering insights for water management to optimize water use efficiency, maintain product quality, and ensure chemical consistency.

These findings can help develop evidence-based irrigation strategies, contributing to more sustainable and resource-efficient cannabis production systems, with important implications for pharmaceutical applications and product standardization. Such responses can confer significant advantages, especially when the metabolites possess economic value [

17].

2. Results

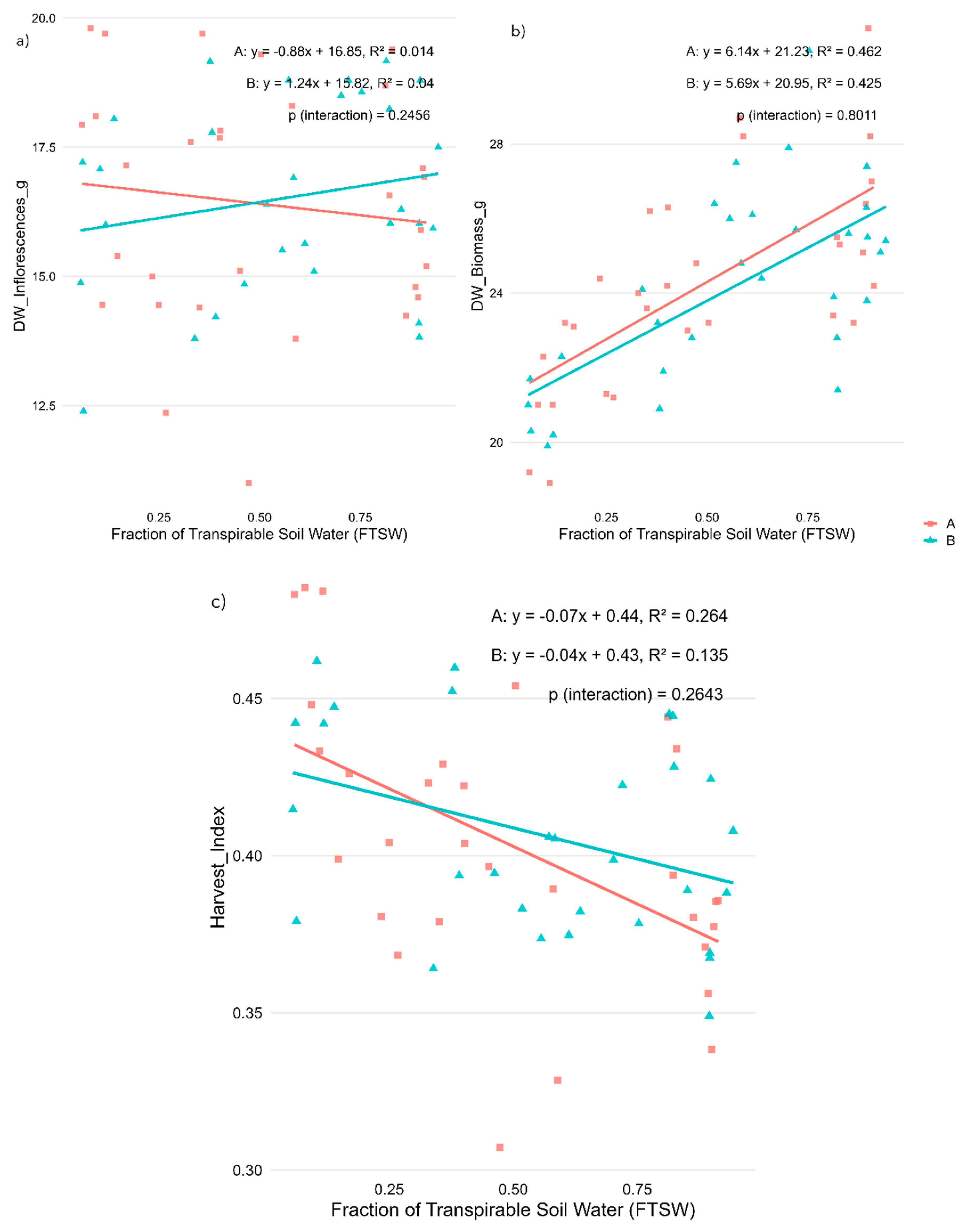

2.1. Regression Analysis on Biomass Allocation and Cannabinoid Profiles for Stress During Vegetative Phase

Regression analysis revealed that water availability, expressed as the Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water (FTSW), significantly influenced plant morphological traits and cannabinoid concentrations in

Cannabis sativa L., with distinct responses observed between the two CBD-dominant varieties. The results are presented in

Figure 1 (panels a-c).

Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g) did not show a significant correlation with water availability in either variety (

Figure 1a), suggesting that dry yield remained relatively stable under different levels of water stress. In contrast, total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g) exhibited a strong positive correlation with Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water (FTSW), indicating that biomass accumulation increased under well-watered conditions in both ‘Fenomoon’ (R² = 0.462, p < 0.001) and ‘Harlequin’ (R² = 0.425, p < 0.001) (

Figure 1b). The harvest index, representing the proportion of biomass allocated to reproductive tissues, resulted in a negative correlation with FTSW, increasing significantly with increasing water stress, particularly in ‘Fenomoon’ (R² = 0.264, p < 0.01), suggesting that drought stress altered the plant’s biomass allocation strategy by favouring reproductive maintenance over vegetative investment (

Figure 1c).

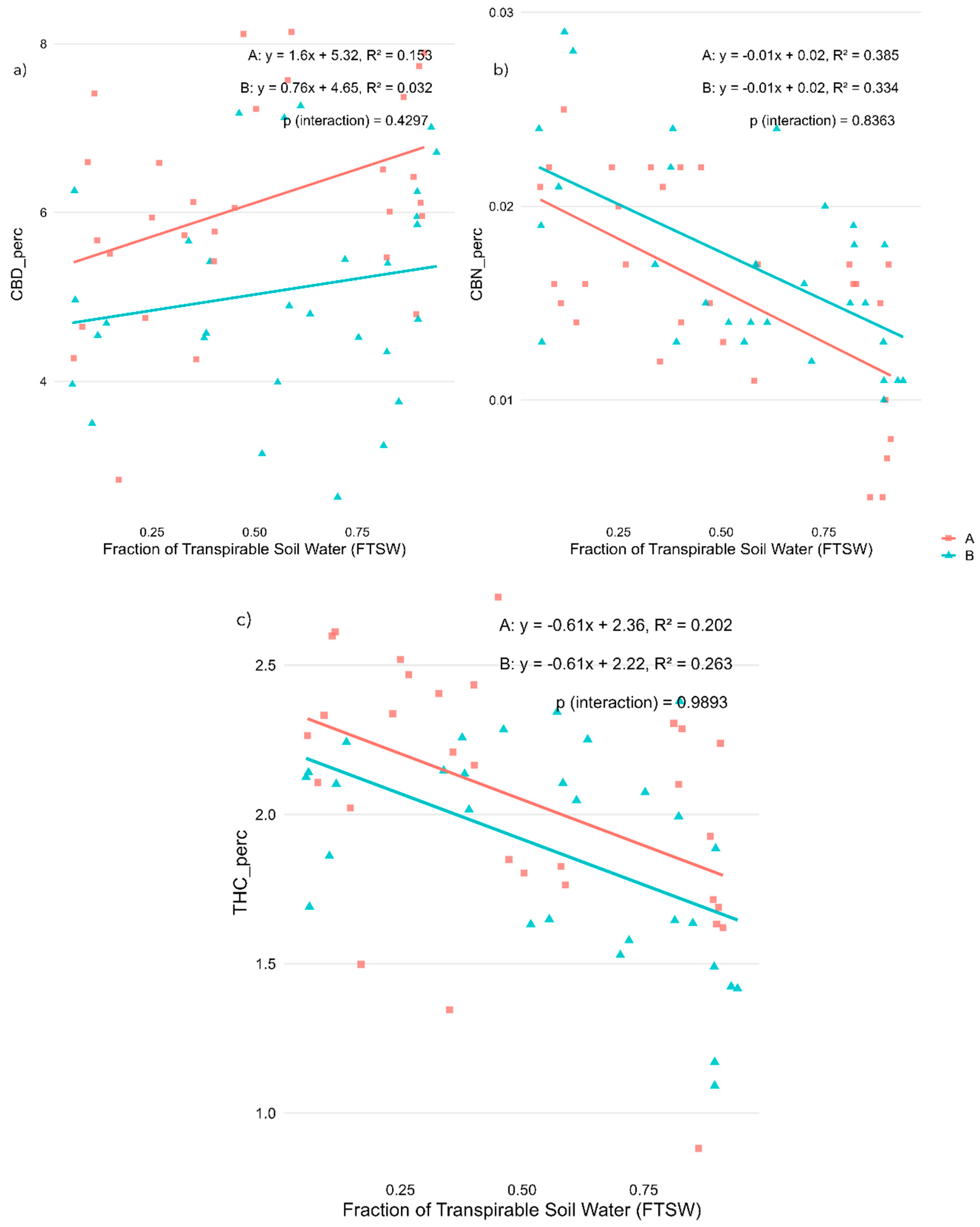

Cannabinoid concentrations also responded to water availability (

Figure 2, panels a-c). Cannabidiol (CBD) content showed a tendency to decline with increasing stress in ‘Fenomoon’ (R² = 0.153, p < 0.05), while no significant correlation was observed in ‘Harlequin’ (

Figure 2a). In contrast, both cannabinol (CBN) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentrations increased under water stress, as evidenced by their negative correlations with FTSW in both varieties. The strongest associations were found for CBN (R² = 0.385 in ‘Fenomoon’, R² = 0.334 in ‘Harlequin’; p < 0.001 for both;

Figure 2b), while THC content also increased significantly under stress conditions (R² = 0.202 in ‘Fenomoon’, R² = 0.263 in ‘Harlequin’;

Figure 2c). These results suggest that cannabinoid synthesis and degradation pathways are highly responsive to water availability, with possible implications for phytochemical consistency in medicinal cannabis production.

Notably, no significant Stress × Variety interactions were observed for any variable, suggesting a comparable response pattern across varieties (

Table 1).

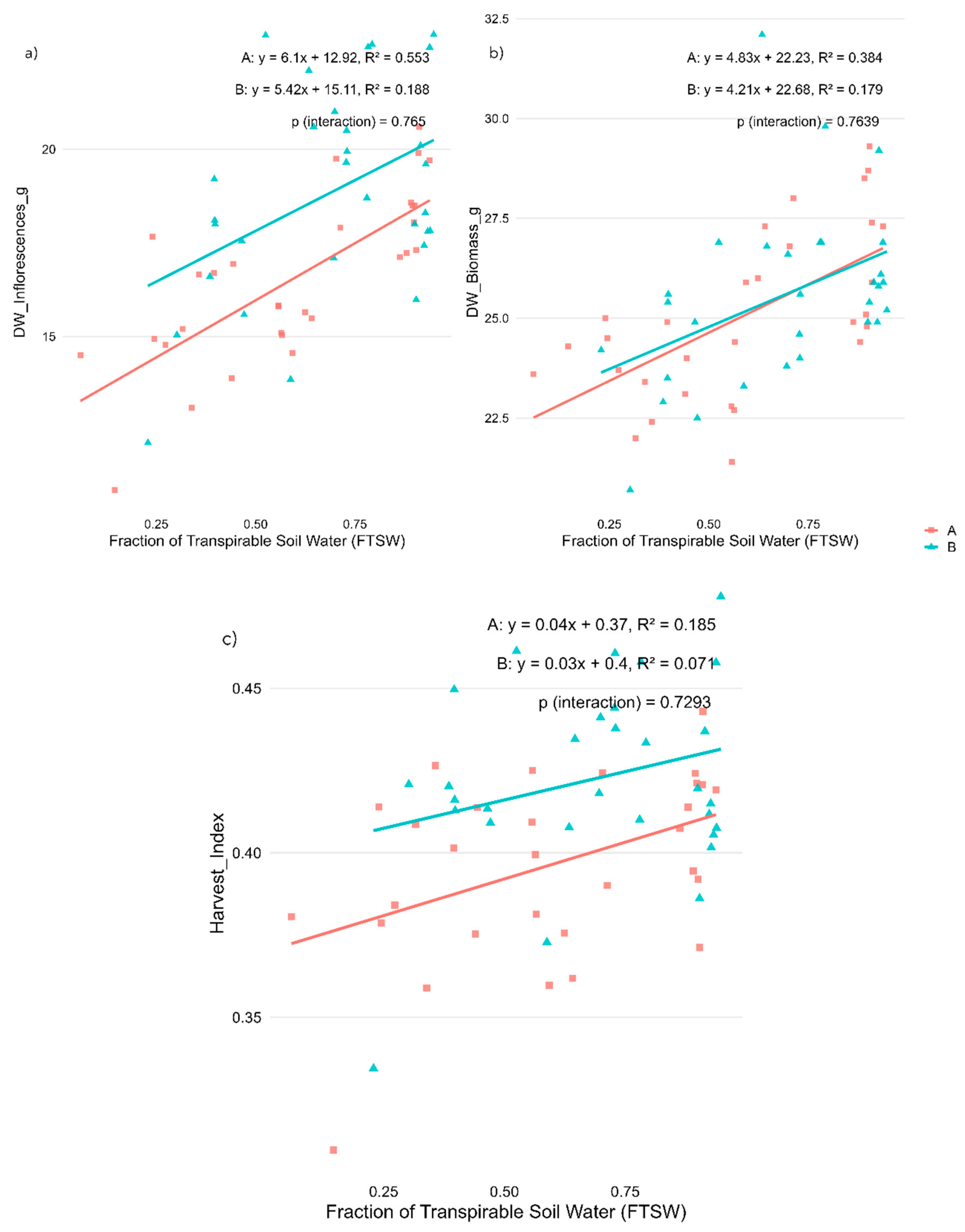

2.2. Regression Analysis on Biomass Allocation and Cannabinoid Profiles for Stress During Vegetative Phase

Regression analysis indicated that water stress applied during the flowering stage significantly affected both morphological traits and cannabinoid profiles in Cannabis sativa L., with responses differing between the two varieties.

Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g) increased significantly with water availability in ‘Fenomoon’ (R² = 0.553, p < 0.001) and to a lesser extent in ‘Harlequin’ (R² = 0.188, p < 0.05), indicating reduced reproductive biomass accumulation under drought conditions (

Figure 3a). Total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g) also showed a positive correlation with FTSW in both varieties (R² = 0.384 in Variety A and 0.179 in Variety B, p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively), confirming that vegetative growth was impaired by water deficit (

Figure 3b). Harvest index showed a weaker but positive correlation with FTSW, significant in ‘Fenomoon’ (R² = 0.185, p < 0.05) and no significant in ‘Harlequin’, suggesting a possible shift in biomass allocation under stress, though less clearly defined than in the vegetative-stage experiment (

Figure 3c).

Among cannabinoids, CBD concentration (CBD_perc) showed a moderate positive correlation with FTSW in both varieties (R² = 0.147 in Variety A, p < 0.05; R² = 0.217 in Variety B, p < 0.01), indicating a decrease in CBD levels under increasing water stress conditions (

Figure 4a). Conversely, CBN (CBN_perc) showed very weak and non-significant correlations in both varieties (

Figure 4b), suggesting that water stress during flowering had limited influence on cannabinoid degradation in this stage. THC content (THC_perc) followed a similar trend to CBD, with slightly weaker correlations (R² = 0.146 in Variety A, p < 0.05; R² = 0.127 in Variety B, p > 0.05), again indicating a slight reduction in THC under higher stress levels (

Figure 4c).

These results confirm that morphological parameters are more responsive to water availability than cannabinoid concentrations, and that inflorescence yield is especially vulnerable to water deficits during flowering. Importantly, no significant interaction between variety and FTSW was observed, suggesting that both varieties responded in a relatively similar way to water stress at this stage (

Table 2).

2.3. Analysis of Metabolite Profiles

To evaluate the effects of water stress and genotype on the terpene composition of Cannabis sativa inflorescences, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was first performed on the rank-transformed terpene data to reduce dimensionality. The first 27 and 24 principal components were retained for the vegetative and flowering stages, respectively, capturing at least 99% of the total variance in each case.

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) conducted on the selected principal components revealed that genotype (Variety) had a highly significant effect on overall terpene composition during both the vegetative and flowering stages (Pillai’s Trace, p < 0.001), confirming the strong genetic determinism of varietal aromatic profiles. Water stress level also produced a significant multivariate effect (vegetative: p < 0.001; flowering: p < 0.001), indicating that the irrigation regime modulated the terpene blend. Furthermore, a Variety × Stress level interaction was statistically significant in both stages (vegetative: p = 0.025; flowering: p = 0.003), suggesting that the response of terpene profiles to water stress is genotype-specific.

Despite these significant global effects, univariate ANOVAs results suggested that the effect of water stress on the composition of volatile compounds in Cannabis depends primarily on the type of compound and the phenological stage (

Table 3). The major compounds, highlighted in yellow in the following table, appear to be mainly influenced by variety, while the impact of water stress on them is minimal or even absent. This suggests that the composition of key compounds such as myrcene, limonene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and caryophyllene is genetically determined and remains relatively stable under different environmental conditions. Among them, only caryophyllene oxide shows a significant response to water stress, indicating that certain key molecules may still be modulated by external factors, though to a limited extent.

In contrast, the minor compounds are much more affected by water stress, in both the vegetative and reproductive phases. This suggests that stress conditions alter the plant’s secondary metabolism, either enhancing or inhibiting the synthesis of specific volatile compounds. For instance, benzaldehyde, ethylbenzene, and p-xylene exhibit notable changes under stress conditions, indicating shifts in metabolic pathways. Interestingly, for some of these compounds, the response to stress varies between the two varieties, highlighting an interaction between variety and stress level. This is particularly evident for bicyclo [2.2.1]hept-2-ene, 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl), γ-elemene, and α-caryophyllene, which show distinct patterns between the two cultivars. This indicates that the two varieties react differently to the same environmental conditions, which could have important implications for selecting varieties best suited to water-limited environments.

Differences also emerge between the vegetative and reproductive phases, with more pronounced responses to water stress observed during the reproductive stage. This is likely due to the plant’s increased metabolic investment in the synthesis of secondary metabolites at this stage, which play a crucial role in both the aroma and therapeutic properties of Cannabis. Some compounds, such as borneol, copaene, and guaiol, exhibit stress-induced variations only in one of the two phases, suggesting that the regulation of volatile synthesis is closely linked to the plant’s developmental stage.

3. Discussion

3.1. Plant Growth and Biomass Allocation under Water Stress

Water stress significantly influenced biomass accumulation and allocation in both experiments, though its effects were more pronounced when applied during the flowering stage. During the vegetative stress phase, the dry inflorescence weight remained largely unaffected by water availability, suggesting that early drought did not significantly impair final floral biomass accumulation, possibly due to compensatory growth during the subsequent flowering phase. In contrast, when water stress was imposed during the flowering stage, dry inflorescence weight responded more sensitively, with a marked decrease in reproductive biomass under stress, especially in ‘Fenomoon’. This finding is consistent with research in other aromatic and medicinal plants (e.g., basil, mint, Salvia) where late water stress leads to reduced flower biomass and essential oil yield [

9,

18].

In the vegetative-stage experiment, total dry biomass positively correlated with water availability (R² = 0.462 in Variety A, R² = 0.425 in Variety B; p < 0.001), suggesting that vegetative growth was highly responsive to water limitation. A similar trend was observed during flowering, albeit with lower effect sizes (R² = 0.384 and 0.179 for variety A and B, respectively), indicating that early-stage water availability exerts a stronger influence on final biomass production than late-stage stress. These results align with previous studies reporting the heightened vulnerability of vegetative tissues to early drought events due to their role in establishing photosynthetic capacity and resource acquisition systems [

19,

20]

Of particular interest is the behaviour of the harvest index during the two growth phases in cannabis. In the early phase, water stress induces a reduction in biomass accumulation [

21]. Consequently, when the plant is rehydrated, it exhibits a smaller biomass structure. At flowering the plant allocates a greater proportion of photosynthates to the development of reproductive structures, namely the inflorescences. As a result, the harvest index tends to increase, as the total biomass accumulated during the vegetative phase is lower. In other words, the denominator of the harvest index is reduced [

5].

Conversely, when water stress occurs during the reproductive phase, particularly at flowering, the plant is unable to sustain inflorescence growth due to the stress conditions [

10]. Consequently, the harvest index tends to decrease, as the numerator, representing the inflorescence weight, increases only marginally [

11].

3.2. Cannabinoid Profiles under Different Stress Conditions

In terms of cannabinoid production, the results show a complex relationship between stress and cannabinoid content during both the vegetative and flowering phases.

During the vegetative stage, cannabidiol (CBD) content decreased moderately with increasing stress in Variety A (R² = 0.153, p < 0.05), indicating a potential sensitivity of CBD biosynthesis to early water limitations. In contrast, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content increased with stress in both varieties (R² = 0.202 in Variety A and 0.263 in Variety B), suggesting that stress during vegetative development may trigger a metabolic shift favouring THC accumulation. In particular, a review by Gorelick and Bernstein (2017) [

22] discussed how various abiotic stresses, such as water deficit and heat, influence resin accumulation in Cannabis plants. They proposed that glandular trichomes and their resinous secretions play a protective role, acting as a biochemical barrier to mitigate environmental stressors, which may explain the observed increase in THC levels under stress. Cannabinol (CBN) levels also increased under vegetative stress (R² = 0.385 and 0.334, respectively, p < 0.001), likely reflecting higher precursor availability (THC) and possible oxidative degradation under stressful conditions.

Under stress applied during the flowering stage, a similar pattern was observed. CBD content decreased with increasing water stress in both varieties, with a moderate correlation in Variety A (R² = 0.147, p < 0.05) and a stronger and more significant effect in Variety B (R² = 0.217, p < 0.01). However, in this case the THC content did not show a statistically significant response to water stress, and CBN levels remained mostly stable, indicating that the plant’s metabolic response during flowering may prioritize reproductive development over secondary metabolite modulation, or that stress was insufficient in intensity or duration to trigger significant biochemical changes at this stage.

3.3. Terpene Modulation under Water Stress

The results of this study highlight the complex interplay between genotype and water availability in shaping the terpene composition of

Cannabis sativa L. inflorescences. Multivariate analyses confirmed that genotype exerts a dominant influence on terpene profiles, reinforcing the notion that the core chemical fingerprint of each variety is genetically determined [

23]. The significant effects observed for variety, water stress level, and their interaction, across both the vegetative and flowering stages, indicate that irrigation conditions also contribute to shaping terpene expression, although to a lesser extent than genetic background.

Interestingly, while multivariate models detected global shifts in terpene composition, univariate analyses revealed that these differences were primarily attributable to variations in minor compounds, rather than in the main aromatic constituents. This finding suggests that the biosynthesis of the most abundant terpenes—such as α-pinene, β-myrcene, D-limonene, and β-caryophyllene—remains largely unaffected by water stress, maintaining a stable core aromatic profile even under varying environmental conditions. This stability is particularly relevant from an agronomic and commercial perspective, as it ensures consistency in the varietal aroma and therapeutic potential, even when plants are subjected to moderate water deficit.

The greater plasticity of minor terpenes under stress conditions may reflect a more dynamic role for these compounds in the plant’s adaptive or defensive responses. While their individual concentrations are relatively low, minor volatiles often have high olfactory impact and could contribute to subtle but perceptually relevant modifications in aroma. Such changes may also have implications for the pharmaceutical properties of cannabis, given the bioactivity attributed to several of these secondary metabolites.

Overall, the findings indicate that while water stress can modulate the fine composition of the terpene bouquet, it does not compromise the identity-defining aromatic traits of the varieties, which are robustly preserved. This suggests that carefully managed irrigation strategies can help balance water use efficiency without negatively impacting the quality attributes of the final product. From a production standpoint, understanding which components of the terpene profile are stable and which are sensitive to stress can inform cultivation practices aimed at maximising both sustainability and product uniformity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted in a greenhouse at the University of Padua, located in Legnaro, Italy. The trial began on 6 December 2024, using rooted cuttings with at least three true leaves from two different varieties of Cannabis sativa L. (Chemotype III, cannabidiol (CBD)-dominant). A total of 120 radicated cuttings, 4 weeks old, were cultivated in parallel, with plants spatially divided into two sections of the greenhouse due to logistical constraints. For this reason, the study was structured and analysed as two independent experiments. In the first experiment, 60 cuttings were cultivated to evaluate the effects of water stress during the vegetative stage, while in the second experiment, 60 cuttings were cultivated to evaluate the effects of water stress during the flowering stage.

In each experiment, 30 cuttings of ‘Fenomoon’ (Variety A) and 30 of ‘Harlequin’ (Variety B) were transplanted into 4.5 L perforated pots containing 2 kg of a substrate composed of peat and sand (1:1 v/v). A felt pad was placed at the bottom of each pot to prevent substrate and water loss through drainage holes. The greenhouse was maintained at temperatures between 22°C and 27°C. Natural sunlight provided the primary source of illumination, supplemented by high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamps, which enhanced light intensity and regulated the photoperiod. Each block was equipped with two HPS lamps, ensuring an 18-hour light and 6-hour dark cycle, with an average supplementary PPFD of 250 µmol/m²/s. Plants were irrigated with water during the first 8 Days After Transplant (DAT) and subsequently with a nutrient solution “CANNA Aqua Vega (solution A + B) (CANNA, Oosterhout, Netherlands)” (EC 0.8 S/cm, pH 5.7). In both experiments, the plants were induced into flowering at 63 DAT by adjusting the photoperiod to 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark and the nutrient solution was changed to a specific one for the flowering phase “CANNA Aqua Flores (solution A + B) (CANNA, Oosterhout, Netherlands)” (EC of 1.6S/cm and pH 5.8).

The experiment was conducted following a split-plot design with two replicates (Block 1 and 2). Each block was divided into two main plots, one for variety A and the other for variety B, with 15 plants of each variety per block. Within each main plot, the three stress levels were randomly assigned as subplots: control (C) at 90% of pot capacity, moderate stress (M) at 60% of pot capacity, and severe stress (S) at 30% of pot capacity. Each treatment included five sub-replicates (plants). Pot capacity (PC) was determined gravimetrically by saturating three representative pots with water and letting them drain overnight, resulting in a water-holding capacity of an average of 460 g per pot

1. In this way, the target weight for each pot was calculated before the stress period began. All pots were irrigated to saturation and weighted. The target weight for each pot was calculated by subtracting 460*0.1 grams for control plants, 460*0.4 grams for plants under moderate stress, and 460*0.7 grams for those under severe stress.

Water stress during the vegetative stage was initiated at 38 DAT. At this point, all pots were weighed at pot capacity (PC), and irrigation was withheld, allowing the pots to dry until they reached their respective target weights, corresponding to 90%, 60%, or 30% of PC. Once the target weights were reached, irrigation was adjusted to maintain the target moisture level for 10 consecutive days. Pots were weighed daily at 14:30 to monitor water loss due to evapotranspiration. After the stress period, pots were rehydrated to pot capacity and irrigated uniformly until the end of the experiment.

In the second experiment, water stress during flowering was initiated at 84 DAT. The protocol was identical to that used during the vegetative stage. Irrigation was withheld until pots reached their respective target weights for 90%, 60%, or 30% of pot capacity. Once the target weights were achieved, the target moisture levels were maintained for 10 consecutive days. After the stress period, pots were rehydrated to pot capacity and irrigated uniformly until the end of the experiment.

After a 118-day growth cycle, the inflorescences were harvested, and their fresh weight was recorded. They were then dried at 30°C for 7 days, ensuring humidity levels were below 10%, after which their dry weight was measured. The dried inflorescences were milled. Cannabinoid and terpene contents were analysed in the laboratory using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

At the end of the experiment, the plants without inflorescences were no longer irrigated and were left to die due to water scarcity. A plant was considered “dead” when severe wilting occurred, preventing recovery even if irrigation was resumed. The pots without aboveground biomass were also weighed to determine the actual wilting point (WP) for each pot.

Although plants were initially assigned to predefined stress levels, the statistical analysis on biomass parameters and cannabinoids content was not conducted on categorical treatments. Instead, plant responses were analyzed in relation to the actual available water for each pot, calculated as Transpirable Soil Water (TSW), following Sinclair and Ludlow (1986)[

24]. TSW was determined as the difference between pot weight at pot capacity (PC), pot weight at wilting point (WP), and plant biomass. As root biomass could not be isolated from the substrate, aerial dry weight was used as a proxy. Correlation analyses were then performed to quantify the plant response to actual water availability.

In this study, we opted to use the Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water (FTSW) as our measure of soil water availability. FTSW is a normalized index of soil water content that ranges from 1 (field capacity) to 0 (wilting point)[

24]. This metric was chosen for several reasons: First, FTSW provides a more plant-centric approach to water stress, as it directly relates to the amount of water available for plant transpiration [

25]. Second, it allows for standardized comparisons across different soil types and plant species, as it accounts for variations in soil water holding capacity [

26]. Third, FTSW has been shown to correlate well with physiological responses in plants, making it a robust indicator of plant water status [

27]. Lastly, the use of FTSW enables more accurate modeling of plant responses to water stress, as it captures the non-linear nature of plant water use efficiency as soil dries [

28]. These factors make FTSW a valuable tool for assessing plant-water relations in our experimental context.

4.2. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The cannabinoid and terpene contents inflorescence were analyzed in the laboratory using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). To extract plant secondary metabolites (PSMs), 2 g of ground inflorescence material from each sample was placed in 20 mL of analytical-grade dichloromethane (CD₂Cl₂) and mixed for 30 minutes. The chemical composition of all samples was determined using a gas chromatography system fitted with an Agilent J&W DB-5MS column (60 m or 30 m in length, 320 μm internal diameter, and 0.50 μm film thickness). Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The GC oven temperature was initially held at 40°C for 2 minutes, then increased to 160°C at a rate of 3°C/min, followed by a ramp of 10°C/min to 250°C, where it was maintained for 5 minutes. The separated components were analyzed by a mass spectrometer. The temperatures of the MSD transfer line, ion source, and quadrupole mass analyzer were set to 280°C, 230°C, and 150°C, respectively. Ionization was performed at 70 eV, and mass detection was carried out in scan mode, covering an m/z range from 30 to 500. Data processing was completed using Mass Hunter software combined with the NIST library (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) within the RStudio environment. To assess the effect of water stress on plant traits and secondary metabolite production, linear regression analyses were performed using stress level (measured as a continuous variable) as the independent variable. Separate regression models were fitted for each variety to explore genotype-specific responses. The coefficient of determination (R²) and p-values were calculated for each model, and significance levels were indicated using asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Additionally, an interaction term between stress and variety (Stress × Variety) was included in a separate model to test whether the response slopes significantly differed between the two varieties.

Graphical outputs were generated using ggplot2, showing regression lines, data points, R² values, and corresponding p-values. Summary tables of R² values and statistical significance for each trait and variety are reported in the Results section.

Regarding the terpenes analysis, due to the high dimensionality of the terpene dataset (64 compounds) relative to the sample size, a multivariate statistical approach was adopted to evaluate treatment effects. Prior to analysis, all terpene values were converted to ranks, in order to reduce the influence of scale variability and non-normal distributions commonly observed in GC-MS metabolite data. This non-parametric transformation allowed for a robust assessment of relative shifts in compound abundance across treatments.

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the rank-transformed terpene dataset to reduce dimensionality and summarize overall variance. The PCA was conducted using the FactoMineR package in R, with standardized input data (scale.unit = TRUE) [

29]. The first principal components (PCs), which collectively explained 99% of the total variance (- 27 for vegetative phase and 24 for flowering phase), were retained for further analysis.

Subsequently, a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was applied to the selected principal components to test for the effects of Block, Variety, Stress level, and their interaction. The MANOVA was conducted using Pillai’s trace test. This approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of how water stress and genotype influence the overall terpene composition, while accounting for multicollinearity and dimensionality reduction.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that water stress significantly influences the morphological development and phytochemical profile of Cannabis sativa L. Chemotype III, with effects varying according to stress intensity, developmental stage, and genotype. Morphological analyses revealed that water-limited conditions alter biomass allocation, with increased vegetative growth and reduced reproductive investment, particularly under flowering-stage stress, as indicated by the decline in harvest index.

Cannabinoid composition was also modulated by water availability. CBD concentrations decreased with increasing stress, whereas THC content increased under vegetative stress, suggesting a stress-induced shift in secondary metabolism. Additionally, CBN levels rose under stress, likely reflecting enhanced oxidative degradation of THC. These biochemical responses highlight the dynamic nature of cannabinoid pathways under abiotic stress and their potential implications for therapeutic efficacy.

The analysis of volatile compounds in Cannabis under water stress shows that major terpenes (e.g., myrcene, limonene, α-pinene, caryophyllene) are largely determined by genetic factors, with minimal impact from water stress [

30]. However, among the major terpenes, caryophyllene oxide is the only compound to show some responsiveness to water stress [

31]. Multivariate analysis indicates that the varietal aromatic profile remains stable under different irrigation treatments, suggesting strong genetic control over primary terpene composition.

In contrast, minor volatile compounds are more sensitive to water stress, especially during the reproductive phase. Compounds like benzaldehyde, ethylbenzene, and p-xylene show significant changes under stress, reflecting shifts in metabolic pathways[

32]. The response to stress varies between Cannabis varieties, demonstrating an interaction between genotype and stress level. For example, certain compounds, such as bicyclo [2.2.1]hept-2-ene and γ-elemene, show distinct stress-induced variations depending on the cultivar.

Water stress affects the plant’s metabolism differently in the vegetative and reproductive stages, with the reproductive phase showing more pronounced responses due to the plant’s increased investment in secondary metabolite production. Some compounds, like borneol, copaene, and guaiol, exhibit stress-induced variations only in the reproductive phase, emphasizing the link between secondary metabolism and developmental stage. Other compounds, including benzeneacetic acid ethyl ester and 1,6,10-dodecatriene, show significant changes across different stress levels, supporting the role of environmental factors in shaping minor volatile profiles. While major terpenes remain stable, minor volatile compounds are highly responsive to water stress, with some exhibiting differential responses across Cannabis varieties. This highlights the importance of careful irrigation management, as water availability significantly influences the chemical composition of minor volatiles. Controlled water stress can help optimize both aromatic and therapeutic properties of Cannabis, and breeding programs could focus on selecting genotypes with greater resilience to water deficits while maintaining desirable terpene profiles.

Overall, these findings underscore the importance of integrated cultivation strategies that consider irrigation timing, water management, and genetic selection to optimize both yield quality and chemical consistency in cannabis production systems. A better understanding of how water stress affects key agronomic and phytochemical traits is essential for sustainable and standardized production, particularly in medicinal and high-value aromatic applications.

-

1In a previous experiment using the constructed substrate, the percentage of water at the permanent wilting point was determined (expressed as the percentage of water relative to the dry weight of the soil dried at 105°C). This determination was conducted in a pot cultivation experiment with lettuce. This means that the value was not exactly the same across the three treatments, as it was not possible to analytically determine the weight at the wilting point a priori, but only at the end of the experiment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; methodology, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; validation, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; formal analysis, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; investigation, M.C.F., and I.L.; resources, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; data curation, M.C.F. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, M.C.F., I.L. and S.B.; visualization M.C.F. and S.B., supervision, S.B.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B.” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by DOR - Universtity of Padova - funds 2024, Scientific coordinator: Prof. Stefano Bona

Data Availability Statement

The original data used for the analysis are present in the supplementary materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all cooperators for their technical support in conducting the experiments and analysis, especially Christine Mayr Marangon, Michele Ongarato, Marco Perin and Marco Sommacal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pant, S.P.; Joshi, S.; Bisht, D.; Bisht, M. Exploring the Historical, Botanical, and Taxonomical Foundations of Cannabis. In Cannabis and Derivatives; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 3–36. ISBN 978-0-443-15489-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response Mechanism of Plants to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic Acid Dynamics, Signaling, and Functions in Plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogawat, A.; Yadav, B.; Chhaya; Lakra, N. ; Singh, A.K.; Narayan, O.P. Crosstalk between Phytohormones and Secondary Metabolites in the Drought Stress Tolerance of Crop Plants: A Review. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Fracasso, A.; Struik, P.C.; Yin, X.; Amaducci, S. Water- and Nitrogen-Use Efficiencies of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) Based on Whole-Canopy Measurements and Modeling. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, D.; Dixon, M.; Zheng, Y. Increasing Inflorescence Dry Weight and Cannabinoid Content in Medical Cannabis Using Controlled Drought Stress. HortScience 2019, 54, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriese, U.; Schumann, E.; Weber, W.E.; Beyer, M.; Brühl, L.; Matthäus, B. Oil Content, Tocopherol Composition and Fatty Acid Patterns of the Seeds of 51 Cannabis Sativa L. Genotypes. Euphytica 2004, 137, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, M.; Charvoz, C.; Dujourdy, L.; Baldovini, N.; Filippi, J.-J. Multidimensional Analysis of Cannabis Volatile Constituents: Identification of 5,5-Dimethyl-1-Vinylbicyclo [2.1.1]Hexane as a Volatile Marker of Hashish, the Resin of Cannabis Sativa L. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1370, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinwächter, M.; Selmar, D. New Insights Explain That Drought Stress Enhances the Quality of Spice and Medicinal Plants: Potential Applications. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannabis Sativa, L. - Botany and Biotechnology; Chandra, S., Lata, H., ElSohly, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-54563-9. [Google Scholar]

- Saloner, A.; Bernstein, N. Response of Medical Cannabis (Cannabis Sativa L.) to Nitrogen Supply Under Long Photoperiod. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 572293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, N.; Bernstein, N. Shape Matters: Plant Architecture Affects Chemical Uniformity in Large-Size Medical Cannabis Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E. Cannabis, 0 ed.; CRC Press, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4987-6164-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Y.; Tang, Q.; Xin, P.; Liu, T.; Yan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zang, G. Genome-Wide Expression Profiles of Hemp ( Cannabis Sativa L.) in Response to Drought Stress. Int. J. Genomics 2018, 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusià, J.; Peñuelas, J. Changes in Terpene Content and Emission in Potted Mediterranean Woody Plants under Severe Drought. Can. J. Bot. 1998, 76, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanuš, L.O.; Hod, Y. Terpenes/Terpenoids in Cannabis: Are They Important? Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2020, 3, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.B. Taming THC: Potential Cannabis Synergy and Phytocannabinoid--terpenoid Entourage Effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1344–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, K.A. Influence of Water Stress on Growth, Essential Oil, and Chemical Composition of Herbs: Ocimum Sp. Int. Agrophysics 2006, 20, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, M.M.; Maroco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding Plant Responses to Drought—from Genes to the Whole Plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Drought Stress in Plants: An Overview. In Plant Responses to Drought Stress; Aroca, R., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-32652-3. [Google Scholar]

- Amaducci, S.; Zatta, A.; Pelatti, F.; Venturi, G. Influence of Agronomic Factors on Yield and Quality of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) Fibre and Implication for an Innovative Production System. Field Crops Res. 2008, 107, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, J.; Bernstein, N. Chemical and Physical Elicitation for Enhanced Cannabinoid Production in Cannabis. In Cannabis sativa L. - Botany and Biotechnology; Chandra, S., Lata, H., ElSohly, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-54563-9. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.D.; McKernan, K.; Pauli, C.; Roe, J.; Torres, A.; Gaudino, R. Genomic Characterization of the Complete Terpene Synthase Gene Family from Cannabis Sativa. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0222363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.; Ludlow, M. Influence of Soil Water Supply on the Plant Water Balance of Four Tropical Grain Legumes. Funct. Plant Biol. 1986, 13, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R. Theoretical Analysis of Soil and Plant Traits Influencing Daily Plant Water Flux on Drying Soils. Agron. J. 2005, 97, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Turner, N. Osmotic Adjustment in Expanding and Fully Expanded Leaves of Sunflower in Response to Water Deficits. Funct. Plant Biol. 1980, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Lebon, E.; Voltz, M.; Wery, J. Relationships between Plant and Soil Water Status in Vine (Vitis Vinifera L.). Plant Soil 2005, 266, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Milroy, S.P. Soil-Water Thresholds for the Responses of Leaf Expansion and Gas Exchange: A Review. Field Crops Res. 1996, 47, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR : An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulvio, F.; Pieracci, Y.; Ascrizzi, R.; Bassolino, L.; Flamini, G.; Paris, R. Insights into Terpenes Profiling and Transcriptional Analyses during Flowering of Different Cannabis Sativa L. Chemotypes. Phytochemistry 2025, 229, 114294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payment, J.; Cvetkovska, M. The Responses of Cannabis Sativa to Environmental Stress: A Balancing Act. Botany 2023, 101, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, K.; Zubay, P.; Németh-Zámboriné, É. What Shapes Our Knowledge of the Relationship between Water Deficiency Stress and Plant Volatiles? Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020, 42, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the vegetative stage on morphological traits in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g), (b) Total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g), and (c) Harvest index. Regression lines represent the relationship between stress levels (expressed as Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water, FTSW) and each trait for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are reported in each panel.

Figure 1.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the vegetative stage on morphological traits in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g), (b) Total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g), and (c) Harvest index. Regression lines represent the relationship between stress levels (expressed as Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water, FTSW) and each trait for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are reported in each panel.

Figure 2.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the vegetative stage on cannabinoid concentrations in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Cannabidiol (CBD), (b) Cannabinol (CBN), and (c) Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content, expressed as a percentage of inflorescence dry weight. Regression lines illustrate the relationship between stress level (FTSW) and cannabinoid concentration for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are indicated in each plot.

Figure 2.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the vegetative stage on cannabinoid concentrations in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Cannabidiol (CBD), (b) Cannabinol (CBN), and (c) Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content, expressed as a percentage of inflorescence dry weight. Regression lines illustrate the relationship between stress level (FTSW) and cannabinoid concentration for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are indicated in each plot.

Figure 3.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the flowering stage on morphological traits in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g), (b) Total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g), and (c) Harvest index. Regression lines represent the relationship between stress levels (expressed as Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water, FTSW) and each trait for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are reported in each panel.

Figure 3.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the flowering stage on morphological traits in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Dry inflorescence weight (DW_Inflorescences_g), (b) Total dry biomass (DW_Biomass_g), and (c) Harvest index. Regression lines represent the relationship between stress levels (expressed as Fraction of Transpirable Soil Water, FTSW) and each trait for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are reported in each panel.

Figure 4.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the flowering stage on cannabinoid concentrations in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Cannabidiol (CBD), (b) Cannabinol (CBN), and (c) Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content, expressed as a percentage of inflorescence dry weight. Regression lines illustrate the relationship between stress level (FTSW) and cannabinoid concentration for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are indicated in each plot.

Figure 4.

Effects of water availability (FTSW) during the flowering stage on cannabinoid concentrations in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties. (a) Cannabidiol (CBD), (b) Cannabinol (CBN), and (c) Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content, expressed as a percentage of inflorescence dry weight. Regression lines illustrate the relationship between stress level (FTSW) and cannabinoid concentration for each variety (A, red squares: ‘Fenomoon’; B, blue triangles: ‘Harlequin’). P-values for the interaction term (Stress × Variety) are indicated in each plot.

Table 1.

Summary of linear regression analyses between stress levels (FTSW) and plant morphological and chemical parameters in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties during the vegetative stage. The table reports the coefficient of determination (R²) and corresponding significance levels for each variety (A: ’Fenomoon’; B: ’Harlequin’), as well as the p-value for the interaction between Stress and Variety (Stress × Variety). Asterisks indicate significance levels of the regression models: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Summary of linear regression analyses between stress levels (FTSW) and plant morphological and chemical parameters in two CBD-dominant Cannabis sativa L. varieties during the vegetative stage. The table reports the coefficient of determination (R²) and corresponding significance levels for each variety (A: ’Fenomoon’; B: ’Harlequin’), as well as the p-value for the interaction between Stress and Variety (Stress × Variety). Asterisks indicate significance levels of the regression models: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

| Variable |

R² - A |

p value - A |

R² - B |

p value - B |

p value - Interaction |

R² - Total |

p value - Total |

| DW_Inflorescences_g |

0.014 |

|

0.040 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

| DW_Biomass_g |

0.462 |

*** |

0.425 |

*** |

|

0.435 |

*** |

| Harvest_Index |

0.264 |

** |

0.135 |

* |

|

0.194 |

*** |

| CBD_perc |

0.153 |

* |

0.032 |

|

|

0.047 |

|

| CBN_perc |

0.385 |

*** |

0.334 |

*** |

|

0.332 |

*** |

| THC_perc |

0.202 |

* |

0.263 |

** |

|

0.239 |

*** |

Table 2.

Summary of regression analysis between water availability and agronomic and phytochemical parameters under flowering-stage water stress. R² values and corresponding significance levels (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001) are reported for each variable and variety (A and B), along with the p-value for the interaction term (Stress × Variety). The table also includes overall R² and p-values calculated without distinction between varieties. The variables include yield components and cannabinoid percentages measured at harvest.

Table 2.

Summary of regression analysis between water availability and agronomic and phytochemical parameters under flowering-stage water stress. R² values and corresponding significance levels (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001) are reported for each variable and variety (A and B), along with the p-value for the interaction term (Stress × Variety). The table also includes overall R² and p-values calculated without distinction between varieties. The variables include yield components and cannabinoid percentages measured at harvest.

| Variable |

R² - A |

p value - A |

R² - B |

p value - B |

p value - Interaction |

R² - Total |

p value - Total |

| DW_Inflorescences_g |

0.553 |

*** |

0.188 |

* |

|

0.348 |

*** |

| DW_Biomass_g |

0.384 |

*** |

0.179 |

* |

|

0.283 |

*** |

| Harvest_Index |

0.185 |

* |

0.071 |

|

|

0.156 |

** |

| CBD_perc |

0.147 |

* |

0.217 |

** |

|

0.067 |

* |

| CBN_perc |

0.002 |

|

0.022 |

|

|

0.004 |

|

| THC_perc |

0.146 |

* |

0.127 |

|

|

0.052 |

|

Table 3.

Statistical significance of the effects of variety (V), water stress (S), and their interaction (V × S) on volatile compounds identified in cannabis inflorescences by GC-MS analysis. The p-values are reported for each compound. The main compounds are highlighted in yellow. Significance levels are indicated as follows: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and “.” for p < 0.1.

Table 3.

Statistical significance of the effects of variety (V), water stress (S), and their interaction (V × S) on volatile compounds identified in cannabis inflorescences by GC-MS analysis. The p-values are reported for each compound. The main compounds are highlighted in yellow. Significance levels are indicated as follows: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and “.” for p < 0.1.

| Compound |

Vegetative |

Flowering |

| Variety |

Stress |

V*S |

Variety |

Stress |

V*S |

| Dimethyl sulfide |

** |

. |

|

|

|

|

| Propanal, 2-methyl- |

*** |

|

|

** |

|

|

| 2,3-Butanedione |

** |

* |

|

|

|

|

| Acetic acid, methyl ester |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| Acetic acid |

*** |

|

|

** |

|

|

| Furan, 3-methyl- |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Butanal, 2-methyl- |

** |

|

|

* |

. |

|

| Propanoic acid |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

| Furan, 2-ethyl- |

*** |

|

|

** |

* |

|

| 2-Butanone, 3-hydroxy- |

*** |

|

|

** |

|

|

| 1-Butanol, 2-methyl- |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

| Butanoic acid |

** |

|

|

** |

. |

|

| 2,3-Butanediol |

*** |

|

|

*** |

. |

|

| Hexanal |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3-Hexen-1-ol, (E)- |

|

|

|

** |

|

|

| 2-Hexenal |

** |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ethylbenzene |

*** |

|

|

** |

** |

|

| 1-Hexanol |

|

. |

|

* |

|

|

| p-Xylene |

*** |

|

|

** |

* |

|

| Heptanal |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Bicyclo [2.2.1]hept-2-ene, 2,7,7-trimethyl- |

*** |

** |

|

*** |

|

|

| .alpha.-Pinene |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Camphene |

*** |

|

|

** |

|

|

| Benzaldehyde |

*** |

. |

* |

** |

|

|

| .beta.-Pinene Phellandreene |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Myrcene |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Acetic acid, hexyl ester |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Benzene, 1-methyl-3-(1-methylethyl)- |

|

*** |

|

|

|

|

| D-Limonene |

*** |

. |

|

*** |

. |

* |

| 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (E)- |

*** |

. |

|

*** |

|

*** |

| 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (Z)- |

*** |

|

* |

*** |

* |

|

| 1,4-Cyclohexadiene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| 1,6-Octadien-3-ol, 3,7-dimethyl- |

** |

|

** |

*** |

|

|

| Phenylethyl Alcohol |

*** |

|

|

*** |

** |

|

| trans-2-Pinanol |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| 2,4,6-Octatriene, 2,6-dimethyl- |

*** |

. |

|

*** |

|

|

| Bicyclo [3.1.1]heptan-3-ol, 6,6-dimethyl-2-methylene- |

*** |

|

. |

|

* |

* |

| 2,7-Octadien-4-ol, 2-methyl-6-methylene-, (S)- |

*** |

|

|

*** |

* |

|

| Borneol |

*** |

|

|

*** |

* |

|

| 3-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (R)- |

|

|

|

* |

|

|

| 3-Cyclohexene-1-methanol, .alpha.,.alpha.4-trimethyl- |

|

|

* |

*** |

*** |

* |

| 6-Octen-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, (R)- |

*** |

|

* |

*** |

|

|

| Benzeneacetic acid, ethyl ester |

* |

|

|

*** |

. |

|

| Bicyclo [2.2.1]heptan-2-ol, 1,7,7-trimethyl-, acetate, (1S-endo)- |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| 3a,7-Methano-3aH-cyclopentacyclooctene, 1,4,5,6,7,8,9,9a-octahydro-1,1,7-trimethyl-, [3aR-(3a.alpha.,7.alpha.,9a.beta.)]- |

*** |

** |

|

*** |

|

|

| Ylangene |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Copaene |

*** |

* |

|

*** |

|

|

| Hexanoic acid, hexyl ester |

*** |

* |

|

*** |

|

|

| Caryophyllene |

*** |

* |

. |

*** |

|

|

| Bicyclo [3.1.1]hept-2-ene, 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)- |

*** |

. |

|

*** |

|

|

| .alpha.-Caryophyllene |

*** |

. |

* |

*** |

|

|

| 1,6,10-Dodecatriene, 7,11-dimethyl-3-methylene-, (E)- |

*** |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-7-methyl-4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (1.alpha.,4a.alpha.,8a.alpha.)- |

*** |

* |

|

|

|

|

| .gamma.-Elemene |

*** |

. |

* |

|

|

|

| Naphthalene, 1,2,4a,5,6,8a-hexahydro-4,7-dimethyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (1.alpha.,4a.alpha.,8a.alpha.)- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| .alpha.-Calacorene |

*** |

* |

|

|

|

|

| 1H-Cycloprop[e]azulene, decahydro-1,1,7-trimethyl-4-methylene-, [1aR-(1a.alpha.,4a.alpha.,7.alpha.,7a.beta.,7b.alpha.)]- |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

| Caryophyllene oxide |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

| Guaiol |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2-Naphthalenemethanol, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydro-.alpha.,.alpha.,4a,8-tetramethyl-, (2R-cis)- |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2-Naphthalenemethanol, decahydro-.alpha.,.alpha.,4a-trimethyl-8-methylene-, [2R-(2.alpha.,4a.alpha.,8a.beta.)]- |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2-Naphthalenemethanol, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-.alpha.,.alpha.,4a,8-tetramethyl-, [2R-(2.alpha.,4a.alpha.,8a.beta.)]- |

*** |

* |

|

|

|

|

| 5-Azulenemethanol, 1,2,3,3a,4,5,6,7-octahydro-.alpha.,.alpha.,3,8-tetramethyl-, [3S-(3.alpha.,3a.beta.,5.alpha.)]- |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| .alpha.-Bisabolol |

*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).