1. Introduction

Due to the ongoing demand for quality, speed and wide application range of modern mobile phones, the wireless technologies have significantly advanced [

1]. This is a continuous process that began in the late nineties and is strongly related to the extensive installation of base stations [

2]. Due to the development of communication protocols for mobile phone devices, the cellular network providers have constructed network infrastructures over a wide range of frequency bands referenced collectively as 2G, 3G, 4G, and 5G communications. Despite that 5G is regarded as a faster and more secure technology than the previous communication technology systems, the new 5G technology is very new [

3] and the suggested frequency range from 24

to 60

(

electromagnetic waves) has not developed all its full potential because the corresponding base stations have not been extensively constructed yet. Due to its very recent development, 5G technology makes advantage of recently opened frequencies or frequencies already assigned to 3G or 4G [

3]. Especially in Greece even the specific 5G frequency range between 24.25

and 29.5

have not be developed satisfactory yet. Despite 5G allows for antenna array technologies of improved directivity, reduced latency and increased data transmission speeds [

3], the 3G and 4G frequency band technologies are still dominant in Greece and this despite the fact that the network providers indicate 5G technology in the mobile smartphone devices. Mobile phones have undergone a remarkable rise in use over the past twenty years with over 80% of people owning and using mobile phone devices [

4]. It is nearly hard to imagine a world without smartphones given how commonplace such devices have become in the everyday life [

5]. A primary factor that boosts this growing trend, is the extensive internet access and the applications that are nowadays available by all cellular network providers [

6]. Despite however the widespread usage of mobile phones, there is a growing unawareness of the hazards associated with the exposure to radiofrequency (RF) electromagnetic fields (EMF) [

7]. This gives rise to concerns over the possible health consequences that result from extended exposure to radiofrequency radiation emanating from mobile devices [e.g [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The problem however, is restricted not only to mobile phones and the corresponding 2G-5G frequency range, but rather extends to the effects due to various sources and a wide range of frequency bands. Due to the international interest on the health effects of the electromagnetic fields, reputed worldwide organisations, such as the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection and the International Committee on Electromagnetic Safety of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) have issued guidelines [

7,

12,

13,

14] which address the potential health risks due to the exposure of the general population to electromagnetic fields, as well as related safety precautions [

15]. The ICNIRP’s guidelines are not regulatory. They rather set scientifically justified standards and a set of basic restrictions and reference levels [

15]. The legislative organisation for Greece is European Union. European Union’s legal area is strict and challenging, but the regulatory limits of 2010 [

16] are based on the 2010 ICNIRP’s report [

12] and those of 1998 [

17], to the 1998 ICNIRP’s report [

13]. Only some updates of technical standards refer to the current ICNIRP’s 2020 guidelines [

7]. The cellular network in Greece by far cannot be characterised as structured. In the last twenty years, the cellular network providers have changed names and ownership twice. Companies with many subscribers do not exist any more, while nowadays, three main providers have the majority of subscribers. In the last five years some fibre optics television providers try to get into the optical telephony and the mobile phone activity. The Hellenic state did not manage to control this boost. As a result, telecommunications antennas and receivers in big cities like Athens, have been installed without specific control and the same is the case for the cellular receivers and emitters. Several cellular type antennas are hidden in places that cannot be easily traced, such as billboards, tablets and signs. Any attempt from the state to rationalise this situation has not yet paid off. As a result the exposure of the Greek population to RF EMF from mobile phones is not known, neither the effects of the different usage scenarios of the mobile phones. The responsible Greek authority is the Hellenic Committee on Radiation Protection with offices within the Demokritos research centre of Greece, in Athens. This Committee may conduct checks by order of another authority or institution. Therefore, the research on mobile phone usage in Greece and, especially, Athens is limited. Hence there is a scientific gap which, importantly, is not of local character. Indeed, the papers of the last years focus on the negative effects of driving and using phone [

18,

19], the use of GPS smartphone data to achieve certain actions [

20], in urban sensing [

21], in mobile security [

22], the use among pupils [

23], students [

24] and older people [

25], the impact of mobile phone technology on humans [

26] and crime applications [

27] and various mobile applications development. Contemporary papers on the effects of mobile phone radiation focus on base stations [

28] and on human head models [

29]. Although the aim of this paper is not to provide a comprehensive review of the subject, it becomes evident from the above that there is restricted focus on the different scenarios of the usage of mobile phones and the corresponding effects. In view of the international interest on the potential negative health consequences of radiofrequency electromagnetic fields, this paper reports electric field spectrum measurements for mobile phones operating in Athens Greece in contract with the main cellular providers of Greece. The electric field measurements are conducted with the Narda SRM-3006 instrument for four distinct ways of usage and for two different distances at 0

m and 1

m from the mobile phone. The dataset comprises eighty two mobile different phones from various vendors and cellular network providers of Greece (three total). The aim is to provide a scientific basis for further investigation of the effects that the the phone usage has on the emitted electromagnetic radiation in the nearby environment and also a foundation for more comprehensive EMF measurements, especially in Greece. In the following, the usage ways, the methodology for the electric field measurements and the statistical analysis of the research are described in

Section 2. Selected spectrum electric field measurements together with the results from the statistical analysis and the discussion are given in

Section 3. The conclusions of the study are presented in

Section 4 and the evaluation and the limitations are given in

Section 5.

3. Results and Discussion

Noteworthy variations are found in the electric field spectra. All types of measurements, i.e.,

,

and

fluctuate with frequency

f in all ways of usage (

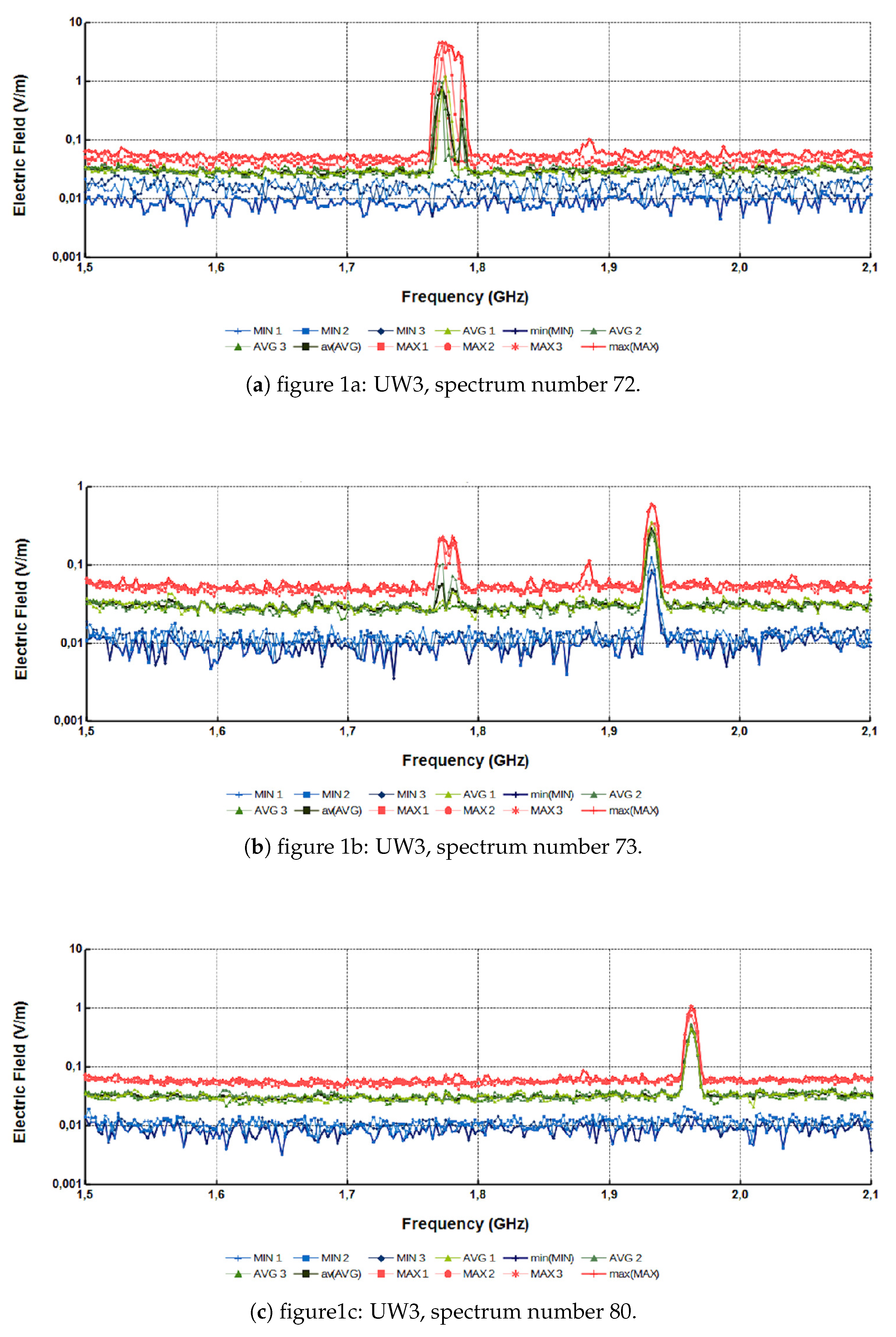

Table 1). Three characteristic cases are shown in

Figure 1. As mentioned in the caption of this figure, this specific experiment has been repeated three times to estimate possible deviations in

,

and

spectra measurements. As can be observed from

sub-figure a of

Figure 1, a single peak is found in both

and

in all three repetitions as well as in the average values of

[av(AVG)] (for each frequency) and the maximum values of

[max(MAX)] (for each frequency). All these peaks are between 1,76

and 1,80

. These peaks range between 0,080

and 8,0

(two significant figures). These peaks are not found in any spectrum measurement of

nor in the minimum values of

[min(MIN)]. The case of

sub-figure b of

Figure 1 is different. One peak is found in the same frequency range as the one of

sub-figure a, namely between 1,76

and 1,80

(three significant figures) but this is mild since the

and

are between 0,0080

and 0,14

. As with

sub-figure a, peaking is not found in

spectra or in minimum values of

[min(MIN)]. On the other hand, a second higher peak is observed in all values (

,

,

, [min(MIN)], [av(AVG)] and [max(MAX)] for frequencies between 1,92

and 1,95

. In

sub-figure c of

Figure 1 there is a single peak in

and

in all three repetitions. Single peak is observed also in [av(AVG)] and [max(MAX)]. The single peak in all these values is slightly shifted in respect to the second peak of

sub-figure b. Indeed the corresponding frequency range is between 1,95

and 1,97

. The electric field of these peaks is between 0,090

and 1,0

. The reader may note here that there were no expectations beforehand about these electric field peaks and the differentiations between them. Hence they rely on the measurements. The peaking alterations (both in electric field and frequency range) may be attributed to the different specifications of each mobile phone and the cellular network parameters that the providers set or change. Taking into account that the mobile network in Greece is not developed systematically and with a strict structure, the reader may find another explanation for these observations. Despite that only three sub-figures are provided the situation is similar within all data set. These issues are discussed later in text after additional calculations. The most significant finding from

Figure 1 is that the call with a mobile phone imposes significant increase in the electric field mainly in

and

. This increase can reach significant electric field values (e.g

sub-figure a) and, as will presented later, this increase may be quite high. This increase is not known by the users and may be of importance in respect to the exposure to electric fields from mobile communications. Concluding with the results from

Figure 1, it can be supported that the electric field spectra measurements provide information on the number of peaks, the corresponding frequency range and electric field value. These are deemed of significance.The above electric field range is within the international range [e.g. [

4,

30,

31,

32] and references therein].

From the data presented so far, it becomes evident that the

versus

f spectra measurements are the most important ones in terms of radiation exposure. In this sense,

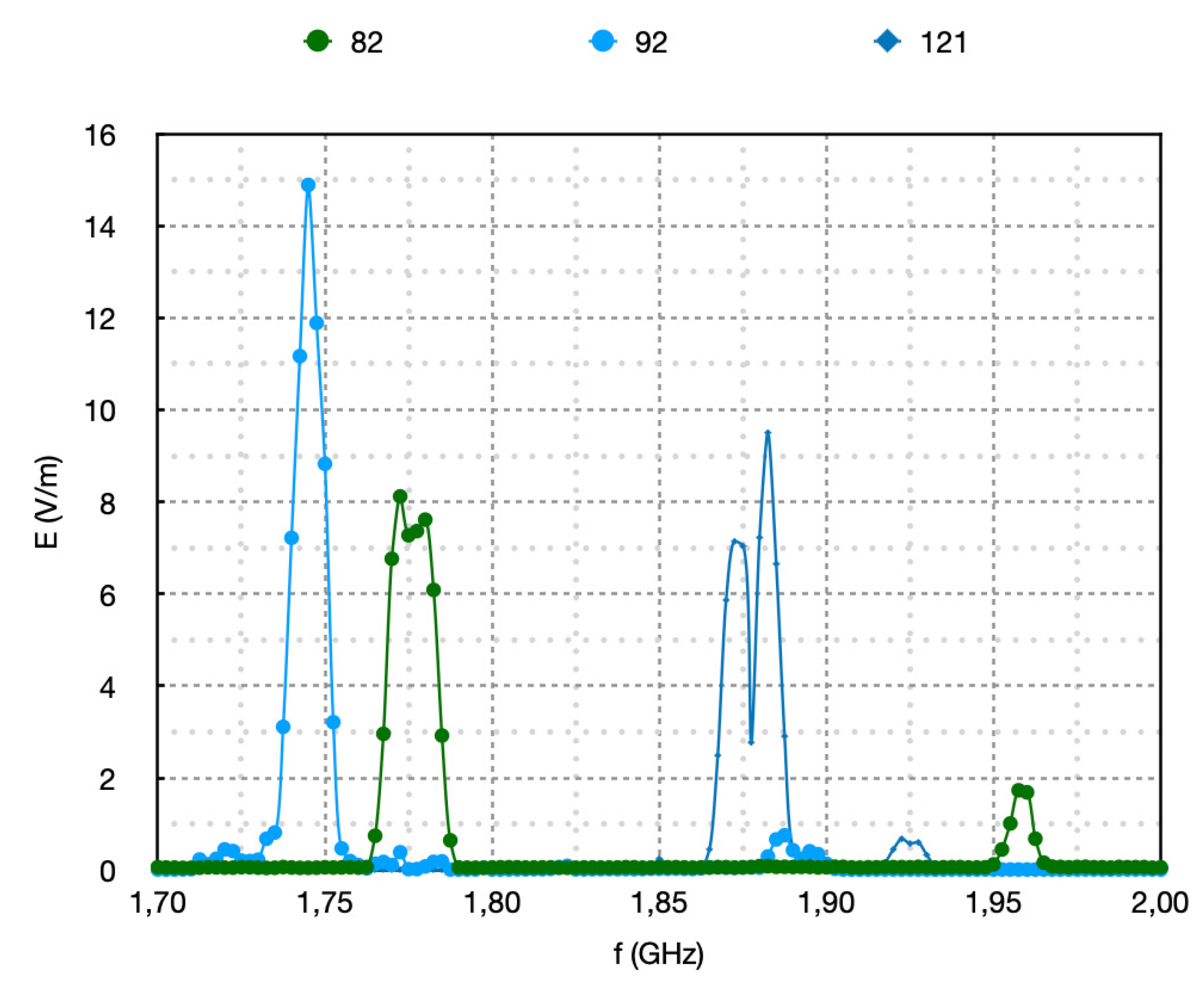

Figure 2 presents characteristic cases of the highest measured peaks of

. The figure presents the electric field spectra from three worst case scenarios. The frequency range here is limited between 1,70

and 2,00

so as to have a clearer view on the peaks. No peak curve functions are employed because these figures present only the basic tendencies.Statistical associations will be presented later in text. It can be observed that spectrum number 92 reaches a maximum of 15

during call. This value is well above the electric field values (in

) presented in the systematic review Ramirez-Vazquez et al. [

33]. According to this review, a maximum electric field of 1,64

is associated with a intensity of 7100

,a maximum electric field of 5,00

with the value of 66400

and the maximum

value of 15,0

(spectrum 92 in

Figure 2) is associated to the a value of 199000

, namely approximately 200

or 0,2

. This latter value is much times lower than the 200

exposure limit proposed by IEEE and ICNIRP [

3],however for frequencies

6

-300

. The estimated intensity values are (even on their maximum) lower (or very lower) than the maximum permissible electromagnetic radiation levels from base station towers, namely 3000

for USA and 500

for India [

28]. The exposure levels from the above figures are within the exposure value range reported in Australia [

34] with the latter reference reporting values up to 1

for the AM exposure, however for 1 minute measuring intervals.Interesting is also,as expected, that these exposures are much lower than the outdoor exposure levels reported by Paniagua-Sánchez et al. [

35] for comparable frequency range.These estimations are in the upper limits of exposure because they are based on the maximum measured electric field of the worst case scenario of phones of

Figure 2. In this sense they rather serve as an indication of the maximum exposure that might occur during calling. The reader should however note in association, that for frequencies between 100

and 6

the health effects from radiofrequency electric fields are expressed as a function of the incident electromagnetic power per tissue mass (

) and only above 6

as a function incident power density (

) [

3,

7].This restricts the above worst case estimations.

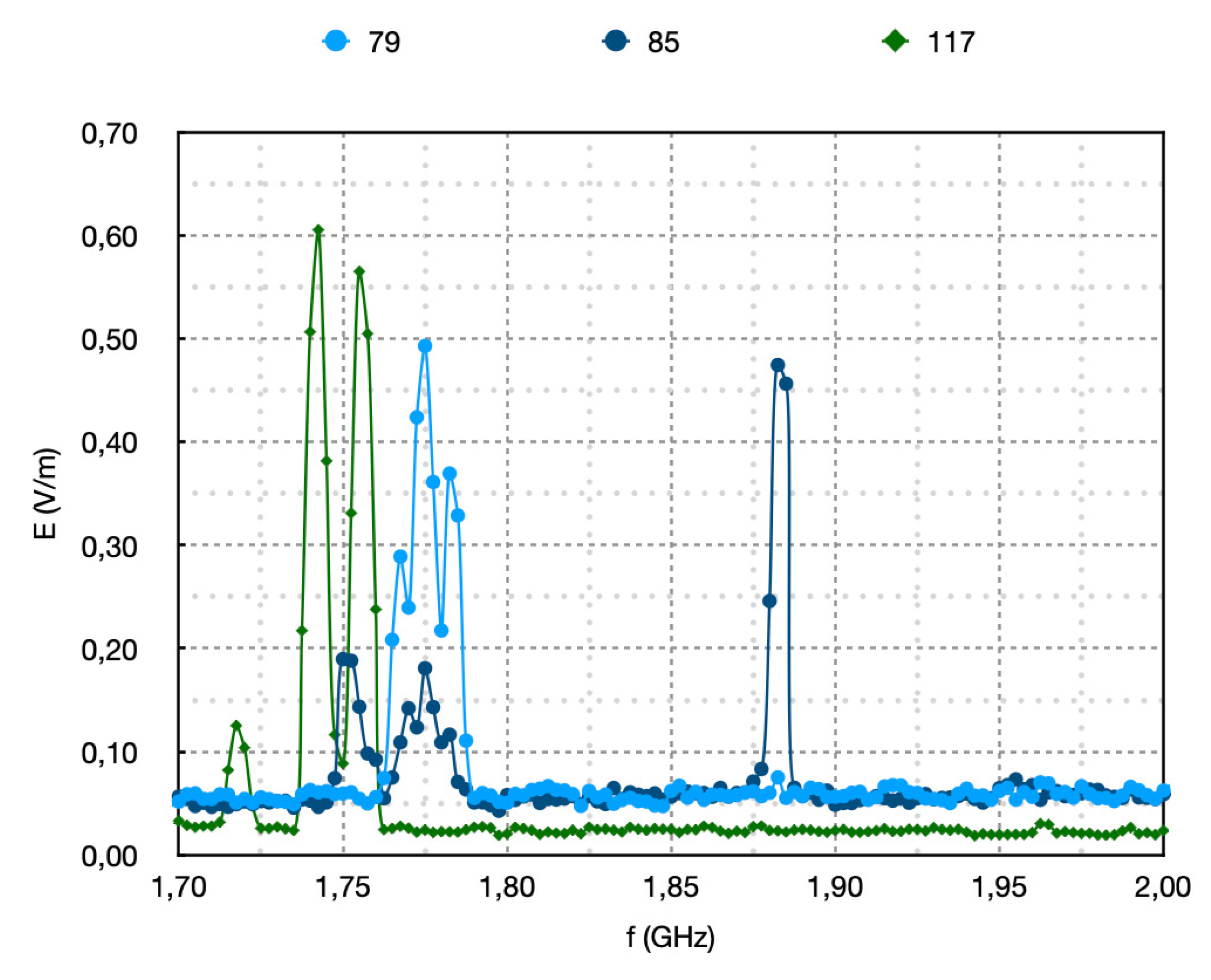

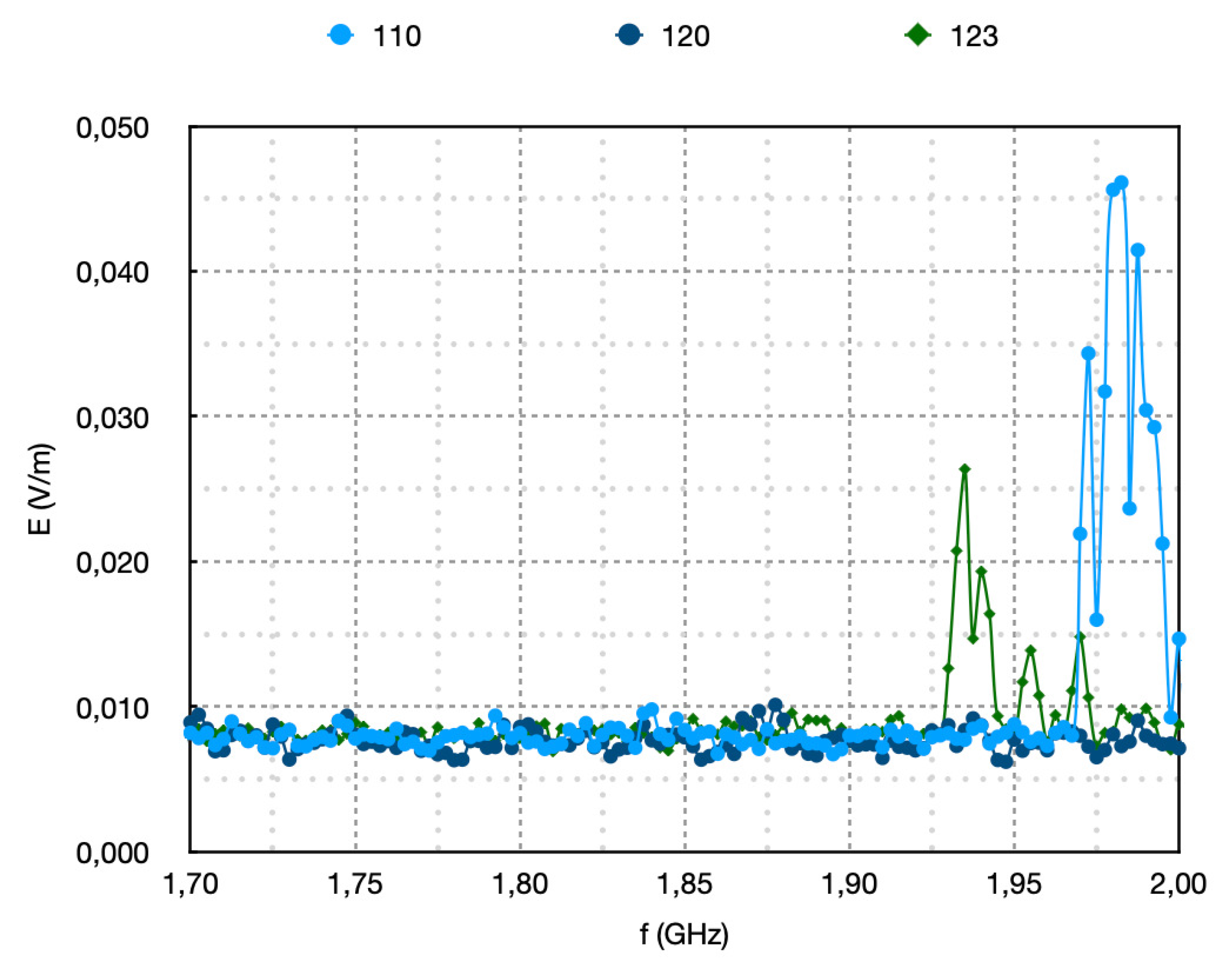

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the medium and mild case scenarios in terms of electric field measurements. The focus is also here on the maximum electric field values. Spectrum 117 peaks at 0,61

, spectrum 79 at 0,50

and spectrum 85 at 0,46

.The maximum electric field values of spectrum 110 is 0,045

and of 123 0,021

. Spectrum 120 has no peak in

. However apart from the vertical axis alterations, the reader may also focus on the differentiations in the horizontal axis, i.e.,the changes in the frequency ranges of the peaks. Observing the frequencies of

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 it is clear that the ranges of the peaks is not systematic. This observation has been expressed already in the discussion of

Figure 1. Specifically in

Figure 2,in all cases (spectra 82,92,121) there is a main peak in different frequencies and a second small peak, again in different frequency ranges.The situation of

Figure 3 is different. Spectrum 117 has three peaks, two main and one minor between 1,72

and 1,74

.Spectrum 79 has one peak between 1,76

and 1,79

, but interestingly, the two minor peaks of spectrum 85 are in the same ranges of the high peaks of spectra of 79 and 117, whereas its main peak is between 1,86

and 1,88

. Peaks of electric field spectra various frequencies are reported by other researchers as well [

30,

31,

32,

36,

37].

It can be supported from Figure 1, 2, 3 and 4 that making a call with a mobile phone yields to peaking in the electric field () which is associated with significant increase in the electric field’s intensity () and an additional exposure of the mobile phone user. The associated effects are, rationally and experimentally, stronger for , milder for and even milder (if not negligible) for the measurements with NARDA SMR-3006. That are the findings.Up to now the results are discussed quantitatively and comparatively without any attempt of statistical testing. The presentation up to now has focused only on the tendencies of the measured quantities and their differentiations. Hereafter, in the consensus of the findings so far, further statistical tests are applied to the collected data.

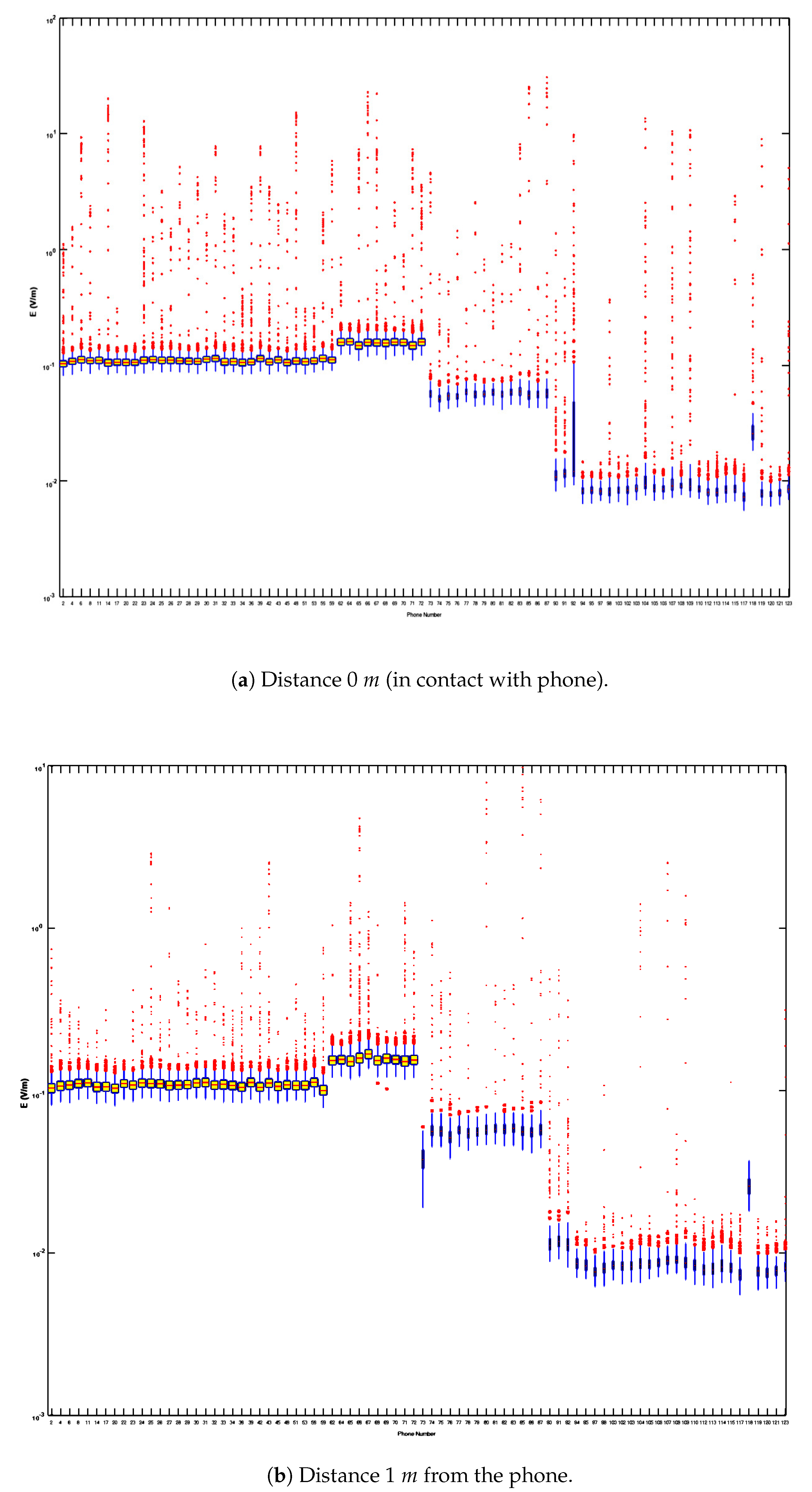

Figure 5 presents the Box and Whiskers plots of the eighty two (82) phones that are from completely different vendors. The data set is presented both at 0

m distance (contact with phone) and at 1

m distance from the phone. The data of every Box and Whiskers plot is extracted to ASCII format for convenience in testing. A first important observation from the phones of this figures is that the in-box distribution shape of each Box and Whiskers plot is symmetric implying a normal distribution of electric field values. In order to test if this is valid for the whole Box and Whiskers dataset of

Figure 5, the median (Q2,50

th percentile) of each plot is compared to the calculated average value of each distribution of electric fields via a paired t-test, omitting however the outliers, namely all the values above

, where

is the interquartile range, namely the total distance between Q1 (25

th percentile) and Q3 (50

th percentile).Under this restriction, the median and the average values of each Box and Whiskers plot do not differ significantly, both for the 0

m (p<0,01) and for the 1

m dataset (p<0.05). As a further normality test, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test is employed in the Q1-Q3 parts via R. The data of

Figure 5 between Q1 and Q3 qurtiles satisfy the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test both at 0

m (

) and at 1

m (

). Since the data are normal without the outliers and median and average values do not differ significantly (as observed and as consequently rational from the normality test), further comparison can be performed in the view that the median value (Q2,50

th percentile) is the average (statistically equal) and the (found) symmetric Q1-Q2 and Q2-Q3 interquartile ranges are the corresponding error bars. In this viewpoint, each median (average) value has error

).The reader should note here two facts. First,through this treatment the non-outlier data can be compared as averages±errors.Second, through this all outliers are surely excluded and due to this any possible bias.All spectra follow a normal distribution and for this reason one way ANOVA is further applied via R. The null hypothesis is that all

N=82 values have equal means and emerge from a distribution of equal variances. The degrees of freedom are

=1 (one independent measurement set, one statistical treatment) and

=81 (

82-1

81).The critical F value for a=0.01 (1% significance⇒99 % confidence interval) and degrees of freedom

=1 and

=81 is

=6,958. Now, calculated F statistic for the 0

m dataset equals 3,440 and for the 1

m data set equals 4,442.Since both

F=3,440<

=7,085 (0

m data) and

F=4,442<

=7,085 (1

m data), it can be supported that both for the distance of 0

m (in contact with the phone) and for 1

m the median (averages) of the 82 Box and Wiskers plots are statistically equal both for 0

m and for 1

m. The reader should note here that from the ANOVA application it follows that all the distributions have equal variances.As another observation it seems that the boxplot data are organised in four Q1-Q3 groups with different average Q1-Q3

. This is due to the process of collecting the measurements. Each measurement set lasts 1 hour for the total of all measurements, namely the four usage ways and the two distances,not taking into account the time for storing,analysing,presenting,software creation and debugging.Because of these, the measurement number of each phone corresponds more or less to its technology. To the viewpoint of the authors this is an issue of the evolution of this research and not a general tendency and for this reason it is not deemed of importance for the claims already given and those presented later in text.This can be further comprehended by the fact that the technological specifications of each phone are not given due to ethical reasons that emerge both for the protection of the vendors names and the identification of non-public data.

The need for omitting the outlier data of

Figure 5 so as to succeed the normality tests, shows how significantly the outliers bias the whole data set. On the other hand the distribution of the outliers in

Figure 5 is much closer to the Box and Whiskers plot of the 1

m dataset than the one of the 0

m dataset.To check this statistically,the outliers range is calculated for every spectrum of

Figure 5 as the difference between the maximum value and the lowest potential value for outliers which equals

. In this manner the outlier range,

,is calculated as

, In this way,82 values of

are calculated for the 0

m data and another 82

values for the 1

m data.Since the outliers mainly affect the deviation of the data from normality,it is rational that the distribution of

is a-priory not normal.Indeed the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test of

give p-values above 0,1 namely (p>0,1 for

values both at 0

m and at 1

m).In order to statistically if

at 0

m is less than the on at 1

m the Wilcoxon signed-rank test can be used and is further employed.The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between

at 0

m and 1

m.

z-value for

N=82 phone and ranking the difference between

at 0

m in reference to the one at 1

m is

15,537 and

. The positive sign of

z implies that

at 0

m is deviates more than the one at 1

m.Therefore calling with a mobile phone being positioned it at 1

m from the ear, yields to lower deviations of

namely to lower maximum values of

and to lower deviations from the mainstream tendencies. In another interpretation the outlier at 0

m are denser and with higher deviations. This means that using a phone in contact with the ear yields to potentially higher effects.

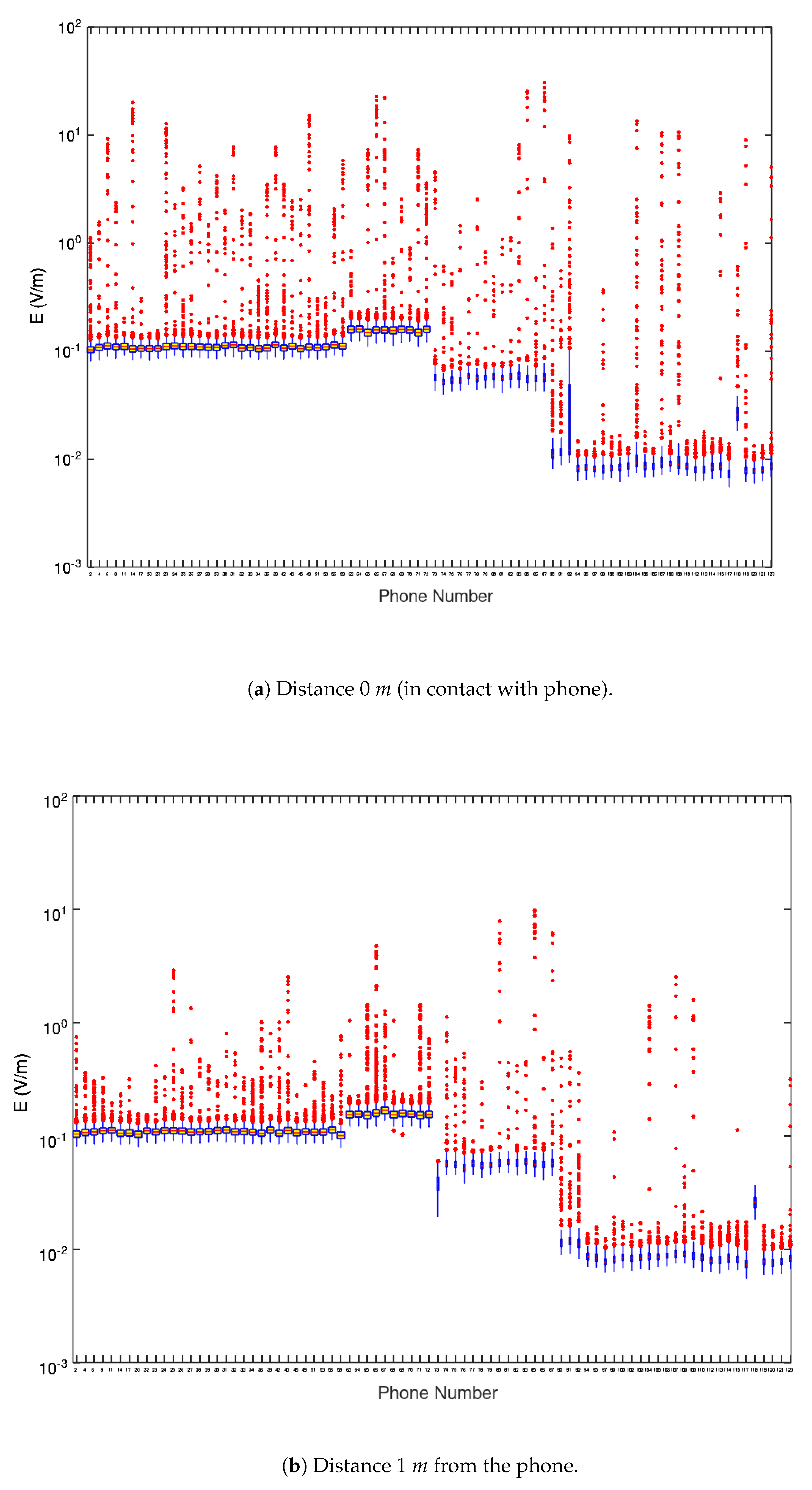

Figure 6 presents the Box and Whiskers plots of the measured

of the total dataset of the 123 phones at 0

m and at 1

m (total 256 spectra). As mentioned in this figure 41 phones (123 total- 82 different phones) are from same vendors as the phones of

Figure 5, but from a different provider. Due to this the 123 are organised in the same four Q1-Q3 groups as those of

Figure 5.The statistical methodology of the previous two paragraphs is followed here as well.For this case

N=123.Omitting the outliers and by employing the ASCII outputs of the Q1-Q3 parts of the 2*123=256 Box and Whiskers plots of

Figure 6, it is found that the main 123 Q1-Q3 parts pass the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test, both for the 0

m dataset (

) and for the 1

m dataset (

). As the above analysis,the null hypothesis is that all

-spectra have equal means and emerge from a distribution of equal variances. The degrees of freedom are also

=1 (one independent measurement set, one statistical treatments) and

=122 (

123-1

122).The critical F value for a=0.01 (1% significance⇒99 % confidence interval) and degrees of freedom

=1 and

=122 is

=6.847. The calculated F statistic for the 0

m dataset equals 4,526 and for the 1

m data set equals 5,426. Since both

F=4,526<

=6,847 (0

m data) and

F=4,526<

=6,847 (1

m data), it can be supported that both for the distance of 0

m (in contact with the phone) and for 1

m the median (averages) of the 123 Box and Whiskers plots are statistically equal both for 0

m and for 1

m. Further, as above, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test is employed to test

at 0

m and at 1

m.Again the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between

at 0

m and 1

m. Here

18,152 and

for the Wilcoxon test.

z is again positive and hence the 0

m data set has higher

in comparison to the 1

m dataset. Therefore from the whole dataset it can be supported once more, that speaking with the phone in contact with the ear yields to denser and greater deviations and therefore it more probable to encounter high maximum

values which means that it more probable to have higher exposures speaking near the phone.

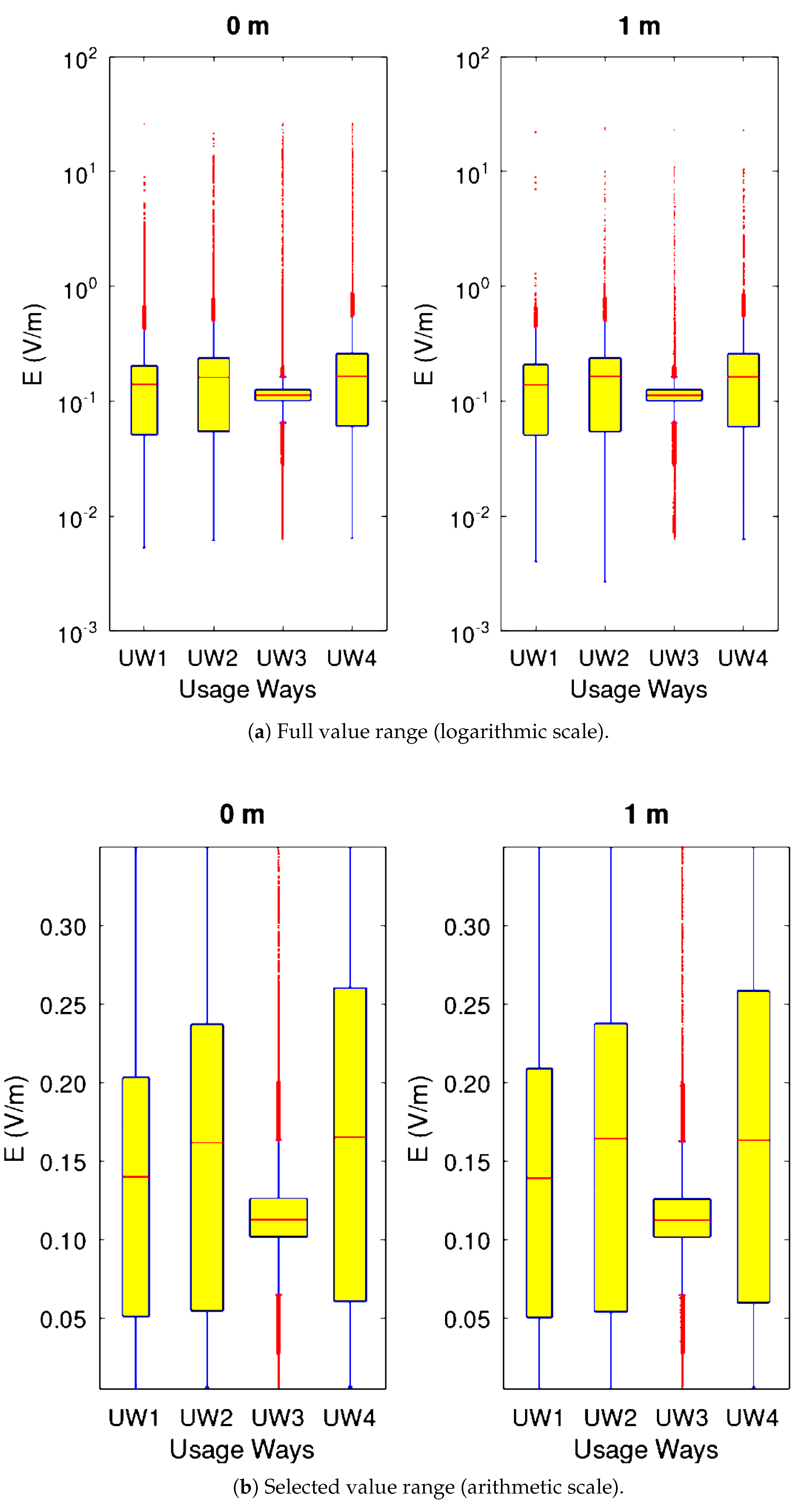

Figure 7 presents the Box and Whiskers plots for the usage ways of

Table 1. To derive this figure the data of all 123 phones were distributed to the usage ways they correspond,generating hence eight (8) tabular data, four (4) referring to 0

m distance and the other four (4) to 1

m distance. Thereafter, each tabular data was converted to a separate column data, forming hence a total eight (8) columns containing all data, sequentially one after the other and corresponding again to four columns for 0

m distance and four columns for the 1

m distance.To avoid bias from zero (i.e., no data) the zeros were neglected from all column data.It is evident that each Box and Whiskers bar is constructed by a large non-zero column data (e.g. for UW3,

=93408 rows at 0

m and

=91152 rows at 1

m). Therefore, the Box and Whiskers plots of

Figure 7 contain the maximum useful information available from the whole dataset. However, this column re-arrangement applies both to the partial

Q1-Q3 data and the corresponding outliers. In another interpretation there is a ninety degree rotation of the partial

rows and a merging of these rotated rows.This is actually a representation of

space to

where

R is the set of real numbers.Through this the Box and Whiskers plot per usage way and distance is achieved (

Figure 7), however at the cost of interference from outliers. This aspect may explain why the full non-zero column dataset for the usage ways UW1,UW2 and UW4 do not satisfy the Kolmogorov-Smirnov both for the 0

m distance and the 1

m distance, in contrary to findings of partial data (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). On the other hand, the main Q1-Q3 part of the Box and Whiskers plot of the data of usage way UW3 (procedure of making a call) of

Figure 7 satisfies the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test at

both for the 0

m and the 1

m columns despite that the outlier interference is also present in UW3.This may be due to the fact that several sets of partial Q1-Q3 parts in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are gathered on the upper parts only. This behaviour, is not found in the partial UW1,UW2 and UW4 data where the outliers are also positive and negative (not shown here all these for brevity reasons).The reader should note here that in a previous work (for a different phone dataset) some

group values were found to follow the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test also for UW1,UW2 and UW4 [

38].However the total phones in each group were few (below 25) and for this reason this approach was not sought in the present paper.

Since the columnar data of the usage ways UW1,UW2 and UW4 do not behave normally they can be compared only visually via the corresponding boxplots. Focusing only on the usage ways UW1,UW2 and UW4,it is observed that both the median values,as well as the Q1 (25% quartile) and Q3 (75% quartile) values are higher in both UW2 and UW4 than those of UW1 (stand-by). This is valid both at 0

m and at 1

m. In the logarithmic plot (

subfigure a,

Figure 7) no differentiation is observed in the median and Q1,Q3 values between UW2 and UW4. However in the corresponding arithmetic plot (

subfigure b,

Figure 7), it is observed that the median in UW4 is slightly higher than the median of UW2 and this is more evident for Q1 and Q3 values between UW2 and UW4.This tendency is observed both at 0

m and at 1

m.Comparing the columnar data of UW1,UW2 and UW4 between 0

m and 1

m no differentiation is found in the Q1-Q3 ranges or the median value. When focusing on the logarithmic scale a similar observation is found as in the discussion of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The number outilers at 0

m are significant more at 0

m compared to those at 1

m.This is valid when comparing each usage way (UW1 or UW2 or UW4) at 0

m vesrus at 1

m. As has been already supported the possibility of addressing high

is higher or, alternatively, the maximum

at 0

m is higher than the one at 1

m. The outlier density at 0

m is also higher.The minimum

value for UW2 is higher that the minimum of

of UW1 but for 1

m this completely opposite. This contradictory observation might reflect the fact that the effect of all ouliers included in the columnar data is higher at 1

m than in 0

m.This potential tendency might also explain why the minimum

at 0

m does not differ from the minimum

at 1

m.Therefore it may be supported that when using a mobile phone for making a call (without answering) to higher electric field values than those of during phone standby and slightly higher electric fled values when ending the call until the phone finally returns to the standby mode.

Focusing solely on UW3 columnar data which behave normally it is observed that the

values of UW3 are slightly lower at 1

m than those at 0

m. The corresponding descriptive statistics for

are presented in

Table 2. Due to the data transformational and the space representation of the previous paragraph the statistical testing of the previous sections discussing the outcomes from of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 cannot be employed. Apart from the reasons already given in the above paragraph there is also another reason. Indeed, the outliers of UW3 sub-figures

Figure 7 are different even from the set of all outliers of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 altogether.Therefore

Q1-Q3 columnar data at 0

m and at 1

m can be statistically checked by other criteria.Since the UW3 Q1-Q3 data follow the normal distribution but have different total values (

=93408 rows at 0

m and

=91152 as mentioned). The sample t-test can hence be employed because the data values between 0

m and 1

m independent,they consist a random sample from potential data measurement and the data are normally distributed.The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between the

Q1-Q3 columnar data at 0

m and at 1

m, i.e., there is no difference when making a call with a mobile phone in contact with the ear and at 1

m away.The one-tailed alternative hypothesis states that the

Q1-Q3 value at 1

m away is less than the

Q1-Q3 value at 0

m. As mentioned there are

=93408 degrees of freedom at 0

m and

=91152 at 1

m.The degrees of freedom for the sample t-test are

=93408+91152-2=184558 and the t-student critical value for an one-tail test at

a=0,05 (95% confidence interval) is

=1,646. The

t value from the UW3 Q1-Q3 data between 0

m and 1

m is

=3,789. Since

the null hypothesis can be rejected, hence

Q1-Q3 values at 0

m are different from the ones at 1

m. Accounting the results of

Table 2, it may be supported that

at 0

m is greater than

at 1

m, there therefore the findings already discussed for the comparisons between 0

m and 1

m are verified from

Figure 7.Therefore making a call with a mobile phone yields to significant electric fields than in standby,making a call without reply, or returning to standby after the end of call. These claims are supported by different aspects of the analysis of the collected electric field database from mobile phones in Greece. Despite the electromagnetic background from the extended use of mobile phones by users, the present study supported the claims from different analysis aspects.