Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions:

- Comparing DoS accuracy achieved from different ML models?

- Can a better autoencoder be generated to achieve efficacy/accuracy for DoS attacks?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Basics

- A network intrusion detection system (NIDS) may include both hardware (sensors) and software (console) components that oversee and monitor network traffic packets at various points in order to detect potential intrusions or anomalies.

- A Host Intrusion Detection System (HIDS) is installed on a single computer or server, known as the host, and alone monitors activity occurring within that system. Despite its limitation to a single system, HIDS outperforms NIDS in capabilities by inspecting encrypted data crossing the network, including system configuration databases, registries, and file characteristics.

- A Cloud Intrusion Detection System combines cloud, network, and host-layer components. The cloud layer supports demand-based access to a shared group or application programming interface (API) by providing secure authentication.

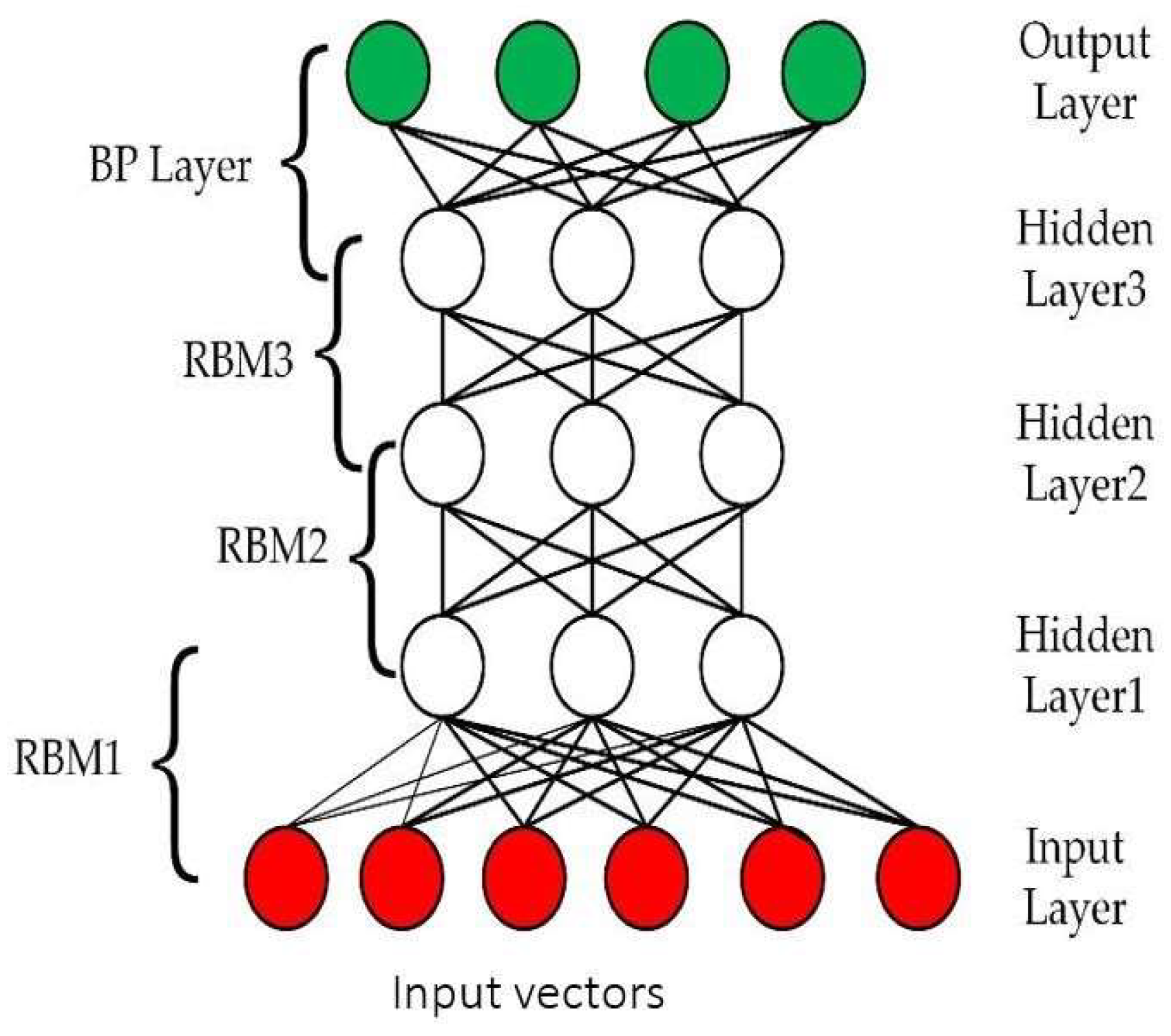

2.2. NIDS Using DNN

2.3. NIDS Using Deep Autoencoders

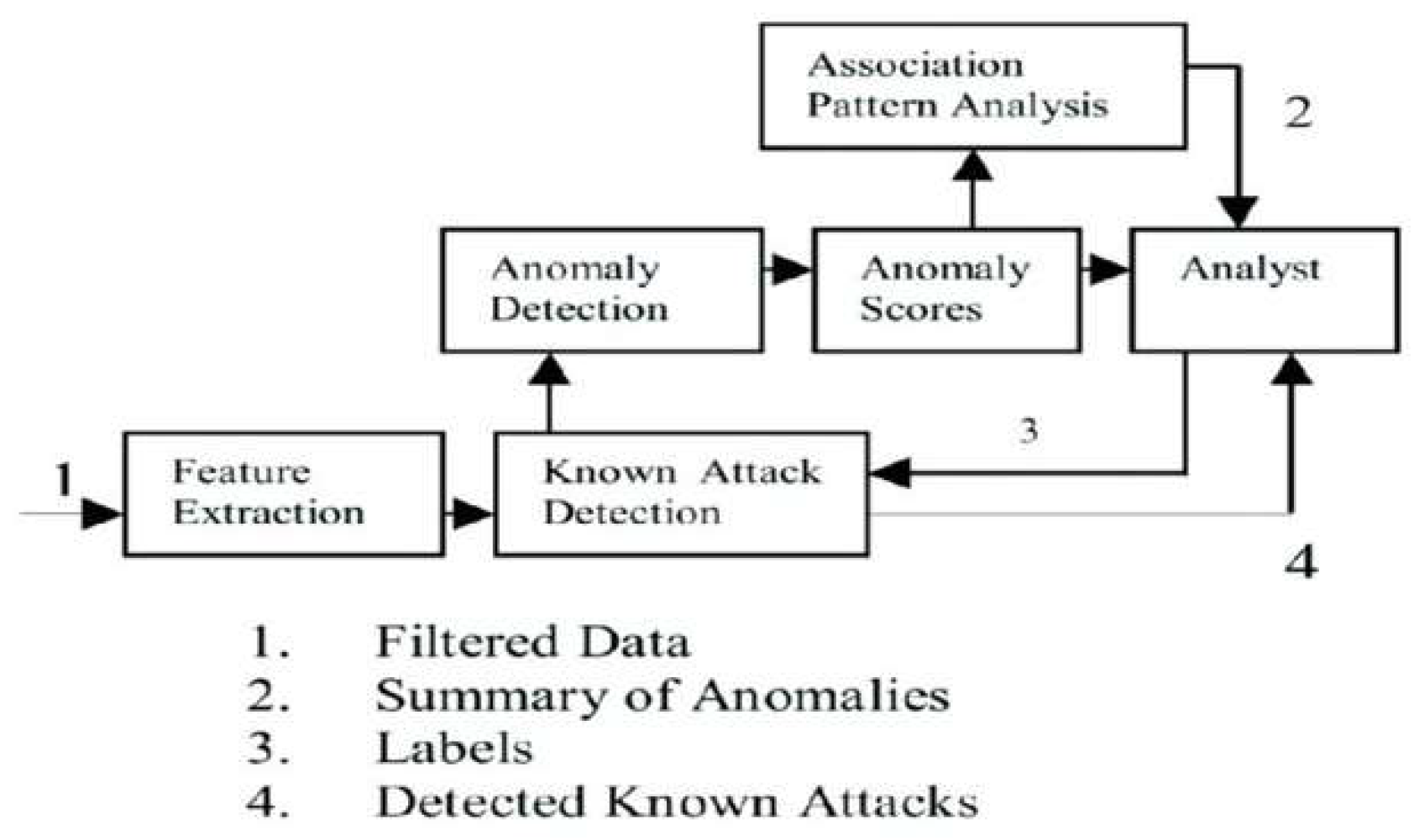

3. Proposed Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

- The data has been filtered to serve as the input, allowing for an extraction of feature patterns.

- Check the association anomaly pattern analysis.

- Mark labels after analysis.

- Detect known attack results.

3.2. Pre-processing

3.3. Training

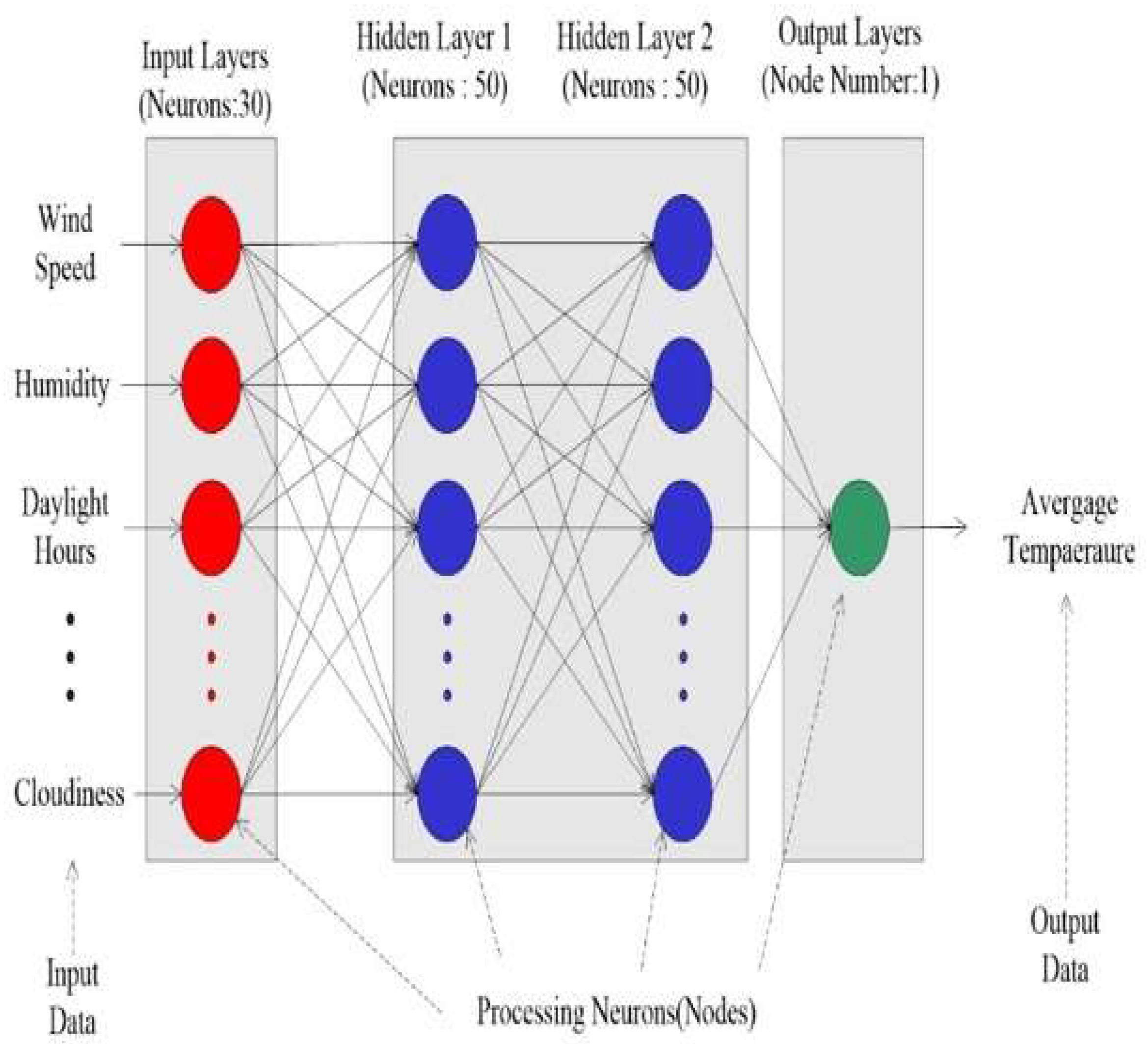

3.4. Modelling IDSEA-NIDS.

- Answer(Xi): The actual or true value for the ii-th observation.

- Answer(Xi)−Predict(Xi)Answer(Xi)Answer(Xi)Answer(Xi)−Predict(Xi): The relative error between the true and predicted values.

- 3.

- MMM: Total number of observations.

- 4.

- Predict(Xi): The predicted value for the ii-th observation.

4. Dataset and Discussions

4.1. Steps

| Train | Test |

| Dimensions of DoS: (113270, 123) | Dimensions of DoS: (17171, 123) |

| Predicted attacks | Actual attacks |

| 0 1 |

0 9676 35 1 7177 283 |

- Accuracy: Measures the overall correctness of the model’s predictions.

- Precision: Evaluates the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions.

- Recall: Assesses the model’s ability to identify all actual positive instances (sensitivity).

- F1-Score: Combines precision and recall into a single metric to reflect a balanced performance.

| Predicted attacks | Actual attacks |

| 0 1 |

0 9473 238 1 2095 5365 |

- Accuracy: Assesses the overall proportion of correct predictions, providing a general measure of model performance.

- Precision: Indicates the accuracy of positive predictions by the model, reducing false positives.

- Recall: Measures the model’s sensitivity in identifying true positive instances, minimizing false negatives.

- F1-Score: Combines precision and recall to give a balanced evaluation of the model’s classification capabilities.

| Accuracy | 0.92345 (+/- 0.02134) |

| Precision | 0.91234 (+/- 0.01876) |

| Recall | 0.93456 (+/- 0.02457) |

| F1-Score | 0.92345 (+/- 0.02012) |

- Accuracy: Evaluated the overall correctness of the model’s predictions.

- Precision: Measured the proportion of true positive classifications among predicted positives.

- Recall: Assessed the model’s sensitivity in detecting all actual positive instances.

- F1-Score: Provided a harmonic mean of precision and recall for a balanced performance assessment.

| Predicted attacks | Actual attacks |

| 0 1 | 0 9422 289 1 1573 5887 |

| Accuracy | 0.92534 (+/- 0.02456) |

| Precision | 0.91245 (+/- 0.02345) |

| Recall | 0.93756 (+/- 0.02134) |

| F1-Score | 0.92456 (+/- 0.02212) |

- Denial-of-Service (DoS)

- Probe Attacks

- Remote-to-Local (R2L) Attacks

- User-to-Root (U2R) Attacks

| Predicted attacks | Actual attacks |

| 0 1 | 0 9598 113 1 1775 5685 |

- Accuracy: Provided the overall correctness of predictions across folds.

- Precision: Measured the proportion of true positives among predicted positives, reducing false positives.

- Recall: Evaluated the classifier’s sensitivity in identifying all actual positive instances.

- F1-Score: Calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced assessment of model performance.

| Accuracy | 0.92150 (+/- 0.01230) |

| Precision | 0.92340 (+/- 0.01456) |

| Recall | 0.91560 (+/- 0.01080) |

| F1-Score | 0.91920 (+/- 0.01120) |

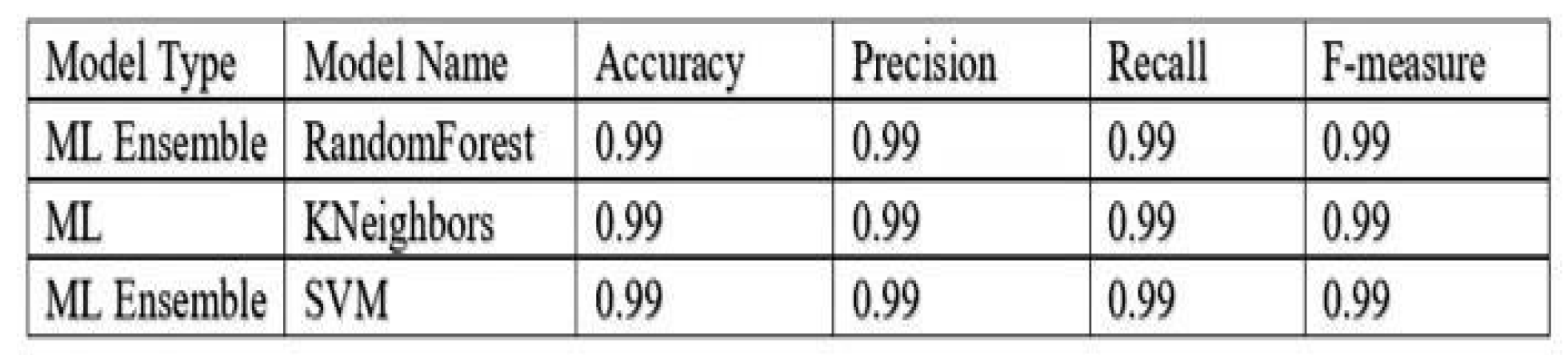

5. Experimental Results and Discussions

6. Conclusions

References

- James P Anderson. 1980. Computer security threat monitoring and surveillance. Technical Report, James P. Anderson Company (1980).

- Lirim Ashiku and Cihan Dagli. 2021. Network Intrusion Detection System using Deep Learning. Procedia Computer Science185 (2021), 239-247. Big Data, IoT, and AI for a Smarter Future. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bengio, P. Simard, and P. Frasconi. 1994. Learning longterm dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 5, 2 (1994), 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Jianfang Cao, Chenyan Wu, Lichao Chen, Hongyan Cui, and Guoqing Feng. 2019. An improved convolutional neural network algorithm and its application in multilabel image labeling. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2019 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Li Deng. 2011. An Overview of Deep-Structured Learning for Information Processing. In Proc. Asian-Pacific Signal Infor-mation Proc. Annual Summit Conference (APSIPA-ASC) (proc. asian-pacific signal information proc. annual summit conference(apsipa-asc)ed.).1– 14.https://www.microsoft.com/enus/research/publication/anoverview-of-deep-structuredlearning-for-information-processing/.

- Dumitru Erhan, Aaron Courville, Yoshua Bengio, and Pascal Vincent. 2010. Why Does Unsupervised Pre-training Help Deep Learning?. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth InternationalConference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 9), Yee Whye Teh and Mike Titterington (Eds.). PMLR, ChiaLagunaResort,Sardinia,Italy,201–208. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v9/erhan10a.html.

- Hosein Fanai and Hossein Abbasimehr. 2023. A novel combined approach based on deep Autoencoder and deep classifiers for credit card fraud detection. Expert Systems with Applications 217 (2023), 119562. [CrossRef]

- Ivo Frazão, Pedro Abreu, Tiago Cruz, Helder Araújo, and Paulo Simões. 2019. Cyber-security Modbus ICS dataset. IEEE Dataport (2019).

- Mohammad Imtiyaz Gulbarga, Selcuk Cankurt, Nurlan Shaidullaev, and AL Khan. 2023. Deep Learning (DL) Dense Classifier with Long Short-Term Memory Encoder Detection and Classification against Network Attacks. In 2023 17th Inter-national Conference on Electronics Computer and Computation(ICECCO).1–6. [CrossRef]

- Min-Joo Kang and Je-Won Kang. 2016. Intrusion Detection System Using Deep Neural Network for In-Vehicle Network Security. PLOS ONE 11, 6 (06 2016), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- H.G. Kayacik, A.N. Zincir-Heywood, and M.I. Heywood. 2003. On the capability of an SOM based intrusion detection system. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2003., Vol. 3. 1808–1813 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- Al Khan, Remudin Reshid Mekuria, and Ruslan Isaev. 2023. Applying Machine Learning Analysis for Software Quality Test. In 2023 International Conference on Code Quality (ICCQ).1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yuancheng Li, Rong Ma, and Runhai Jiao. 2015. A hybrid malicious code detection method based on deep learning. International Journal of Security and Its Applications 9, 5 (2015), 205–216.

- Guisong Liu, Zhang Yi, and Shangming Yang. 2007. A hierarchical intrusion detection model based on the PCA neural networks. Neurocomputing70,7(2007),1561–1568. AdvancesinComputational Intelligence and Learning. [CrossRef]

- Mantas Lukoševičius. 2012. Self-organized reservoirs and their hierarchies. In Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning–ICANN 2012: 22nd International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Lausanne, Switzerland, September 11-14, 2012, Proceedings, Part I 22. Springer, 587–595.

- Yisheng Lv, Yanjie Duan, Wenwen Kang, Zhengxi Li, and Fei- Yue Wang. 2015. Traffic Flow Prediction With Big Data: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 16, 2 (2015), 865–873. [CrossRef]

- Ines Ortega-Fernandez, Marta Sestelo, Juan C Burguillo, and Camilo Pinon-Blanco. 2023. Network intrusion detection system for DDoS.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).