1. Introduction

The fiducial Newcomb-Benford law (NBL) [

1,

2] is well-established for standard positional notation (PN) [

3]. It states that the first digits of randomly chosen original data typically outline a logarithmic curve in diverse fields irrespective of their physical units; series of raw natural values usually are nearly scale-invariant, i.e., geometric [

4]. The law must be valid for any place-value numeral system if it is fundamental. This paper provides the formulas for bijective numeration (BN) [

5], suggesting that NBL might account for an elementary principle.

Suspicion about the authenticity of the number cero [

6] suggests that BN [

7] is likely more natural than standard PN, the number system we use daily. BN is a zero-free and unambiguous number system, contrasting with standard PN; every natural number has a unique representation using the symbols

. (Watch the notation; we display the radix underlined to denote BN instead of standard PN.)

Every NBL rule for standard PN has a bijective counterpart. BN is a notably more efficient notation than standard PN due to its compactness, especially for the smaller radices

. An enumerated list of

-ary bijective numerals is automatically in "shortlex" order, with

bijective

-ary numbers of length

[

8]. For instance, the sequence of 11 ternary bijective numbers

, from decimal

to

, has

numbers of length 2.

BN is a natural consequence of NBL, which can originate from a primordial inverse-square law [

9]. This "canonical" probability mass function (PMF) might be the sought-after cause of NBL [

10]. Under the tail of the canonical PMF, we find information based on the concept of likelihood; probability is a relative likelihood. The theory has fundamentally a twofold manifestation, namely the NBL for the global ("rational", discrete, and harmonic) and local ("real", continuous, and logarithmic) domains.

Departing from (where ), the probability of a natural variable falling into is a harmonic likelihood, namely the bucket’s width relative to the base’s support width , where , , and is the nth harmonic number. The base is a global referent that changes the status of a number to a globally computable elemental entity denominated a "quantum". When the bucket is , we obtain the global NBL of a generic quantum q, , where and . Thus, the mass of a quantum is a rational number representing the harmonic improbability of an elemental gap. When has a colossal value, a "coding source " must establish a local referent to normalize its information separated from the surrounding environment, changing the status of a quantum to a locally computable elemental entity denominated a "digit". The probability of a quantum falling into is the bin’s width relative to the radix support’s width . When the bin is , we arrive at , where is a digit such that .

The only symbol in the bijective unary is 1; contrary to standard PN, this numeral system is not exceptional and can result from the natural continuation of a radix reduction process. In the bijective binary, 1 occupies (global) and (local), while 2 occupies and , respectively. Likewise, 1 in the bijective nonary occupies (global) and (local), while 9 occupies and , respectively. The harmonic plot is always steeper than the logarithmic one.

This double-scale theory unites efficiency and entropy. "The lowest digits maintain distinctness from the surroundings thanks to their solid entropic support. The more significant digits are vulnerable and give rise to more transitions..." From the information perspective, whereas the first quanta or digits make the difference irrespective of the string length, the last ones might provide negligible, even arbitrary, information [

11].

We back this claim by delving into the sums of Kempner’s curious harmonic series [

12], which echo the bijective harmonic scale traced by the global NBL. This outcome is absolute because every Kempner series is infinite, and the calculations consider every possible numerical chain. Short numerical chains or low quantum densities are accessible and cheap, producing heavy harmonic terms that condense the space. In contrast, long chains or high densities are "rare" and deliver slender harmonic terms.

For instance, while the specific digits involved in a constraining numeral do not matter, the length of such a numeral does; the law favors against and this against because 12345 is less probable than 1234 and this is less probable than 234. Likewise, while removing the harmonic decimal terms that include less than of 5’s in the denominator makes a harmonic series converge, missing the terms including of 5’s does not impede the divergence of the depleted harmonic series.

Our study of the depleted and constrained harmonic series allows us to conclude that a conservative policy of significands and positions might exist inherent to universal computation, restricting the resolution of PN to preclude unnecessary precision. Consequently, we conjecture that the natural span of a positional system in base is , a measure of the physical quantity of tractable numerals. Beyond this computational resolution, quanta could be haphazard for practical purposes.

This article’s field of study is information, probability, and number theory. First, we describe the global and local NBL theory for BN, unveiling that both laws are length- and position-invariant. Then, we substantiate that the set of Kempner’s "curious" series conforms to the global NBL for BN. Further, we surmise a universal resolution resolution, i.e., the prospect of a position threshold ascribed to a natural PN system.

2. The Global NBL for BN

This subsection follows the same plot thread developed in [

9]’s section "The rational (global) version of NBL".

A sample of numerical chains encoded using bijective

-ary satisfies the global NBL if the leading quantum falls in bucket

relative to the area swept by base

with probability

where

and

. When

and

we obtain the probability with base

of leading quantum

q.

Definition 1.

A leading quantum q is said to satisfy the global NBL for bijective -ary numeration if it occurs with probability

Thus, NBL for the standard PN in base corresponds to NBL for bijective -ary numeration.

Example 1. We obtain , , , , , and , where "" symbolizes the bijective decimal base. Owing to and , the odds constitute an essential sharing out.

The entropy of PMF (1), , is the expected value (weighted arithmetic mean) of the harmonic likelihood function, namely (where is the digamma), evaluated at x’s probability mass reciprocal.

Definition 2. The global NBL entropy is given by the formula

Example 2. , , , , and .

When

acquires a gargantuan value, we can take the summation as an integral and the harmonic number function as the natural logarithm, so that the "differential entropy" [

13] of the global NBL approximately tends to

Thus, the global entropy is finite, which agrees with the Bekenstein bound in physics [

14].

The probability of picking a chain of any length starting with c is the likelihood gap it induces on the -ary harmonic scale.

Definition 3. A leading numerical chain c is said to satisfy the global NBL for bijective -ary numeration if it occurs with probability

This occurrence probability becomes (1) when c is a base’s quantum.

Example 3. The probability that a bijective decimal chain starts with 11 (e.g., ) and (e.g., ) is and , respectively.

Definition (3) allows us to derive the following PMF.

Definition 4. A numerical dataset is said to satisfy the global NBL for BN if the probability of picking a length-l bijective -ary chain starting with the quantum q, where and , is

Example 4. The probability of running into 1 to 3 as the first quantum of a bijective ternary chain with length 5 is , and the chances of choosing 1 to as the first quantum of a bijective decimal chain with length 2 is .

Watch that (4) boils down to (1) if , meaning that the global NBL is length-invariant beside base-invariant.

Definition (3) also allows us to derive the following PMF.

Definition 5.

A numerical dataset is said to satisfy the global NBL for BN if the probability of runing into q as the p-th quantum of a bijective -ary chain, where and , is

Example 5. The probability of getting 1 to 3 as the fifth quantum of a bijective ternary chain is , and the chances of encountering 1 to as the second quantum of a bijective decimal chain is .

Watch that (5) boils down to (1) if

, meaning that the global NBL is position-invariant beside base-invariant.

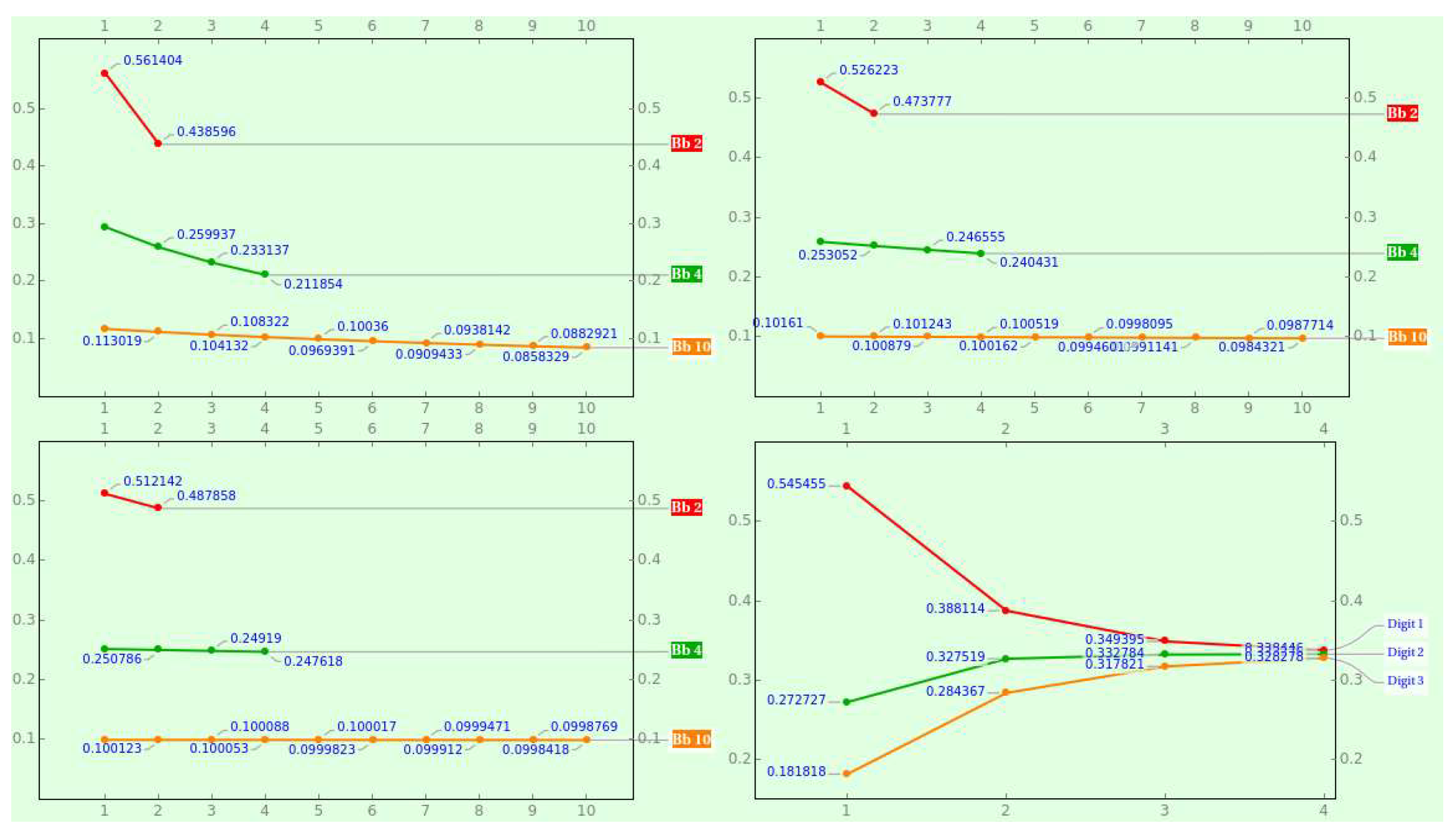

Figure 1 shows the PMF of various bijective bases for consecutive positions and the hyperbolic progression of the bijective ternary digits as the position increases.

3. The Local NBL for BN

This subsection follows the plot thread developed in [

9]’s section "The fiducial (local) NBL".

The ratio between the area under the hyperbola delimited by the bin

and the radix support

is

We arrive at the NBL for BN by putting and .

Definition 6.

A sample of numerals expressed in bijective -ary PN satisfies the local NBL if the leading digit d occurs with probability

Thus, the NBL with radix corresponds to the bijective -ary numeration’s NBL.

Example 6. The standard ternary system assigns to 1 and 2 the probabilities and , which is the PMF of bijective binary numeration. In the usual case where the radix is , the standard decimal system assigns to digits 1 and 9 probabilities of and . In contrast, the bijective decimal numeration assigns to digits 1 and probabilities of and . On the other hand, the local bijective ternary numeration assigns to 1, 2, and 3 the probabilities , , and , contrasting with the percentages , , and the global bijective ternary numeration assigns.

The entropy of PMF (6) for radix , , is the expected value (weighted arithmetic mean) of the likelihood function () evaluated at x’s probability mass reciprocal.

Definition 7. The local NBL entropy is given by the formula

Example 7. , , , , and .

Because and we assume that is a positive natural number, the local entropy is finite, in agreement with the Bekenstein bound.

Note that (6) is also valid for the unary numeral system, unlike in standard PN;

assigns the probability of

to 1. The scale of a system "encoding" data in the bijective unary is linear, i.e., has no curvature. In BN, (re)coding from unary into

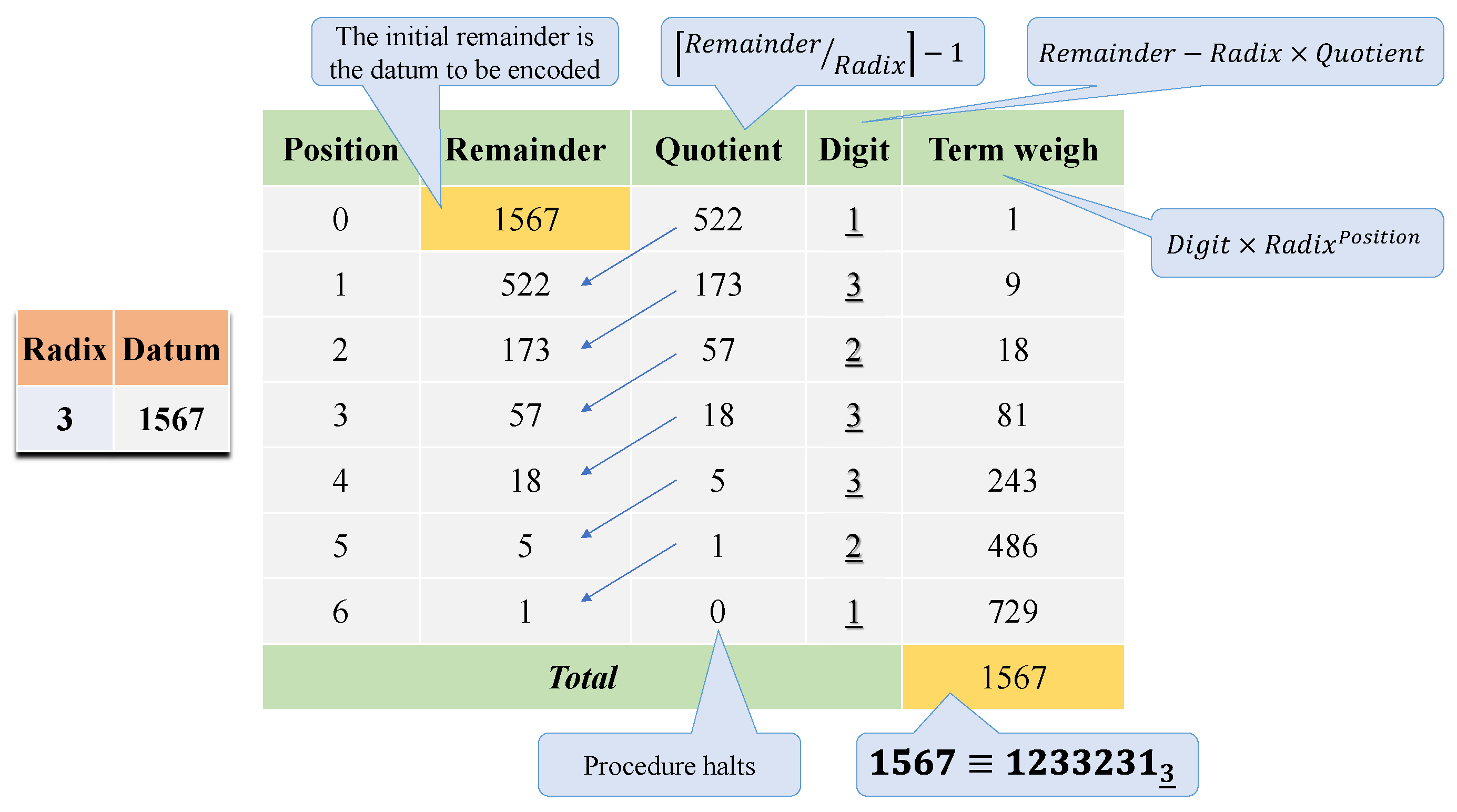

-ary means summing the number of ones and executing an iterative procedure based on Euclidean division;

Figure 2 describes the encoding algorithm that converts the representation of 1567 into

.

We can generalize the PMF given by (6) to the probability of getting a leading -ary numeral of any length. It is the likelihood gap it induces on the logarithmic scale.

Definition 8. A leading numeral n is said to satisfy the local NBL for bijective -ary numeration if it occurs with probability

Example 8. The probability that a bijective decimal numeral starts with "", say or , is .

Definition (8) allows us to derive the following PMF.

Definition 9.

A numerical dataset is said to satisfy the local NBL for BN if the probability of picking a length-l bijective -ary numeral starting with the digit d, where and , is

Example 9. The probability of picking 1 to 3 as the first digit of a bijective ternary numeral with length 5 is , and the probability of choosing 1 to as the first digit of a bijective decimal numeral with length 2 is .

Owing to (9) boils down to (6) if

, the local NBL is length-invariant beside radix-invariant.

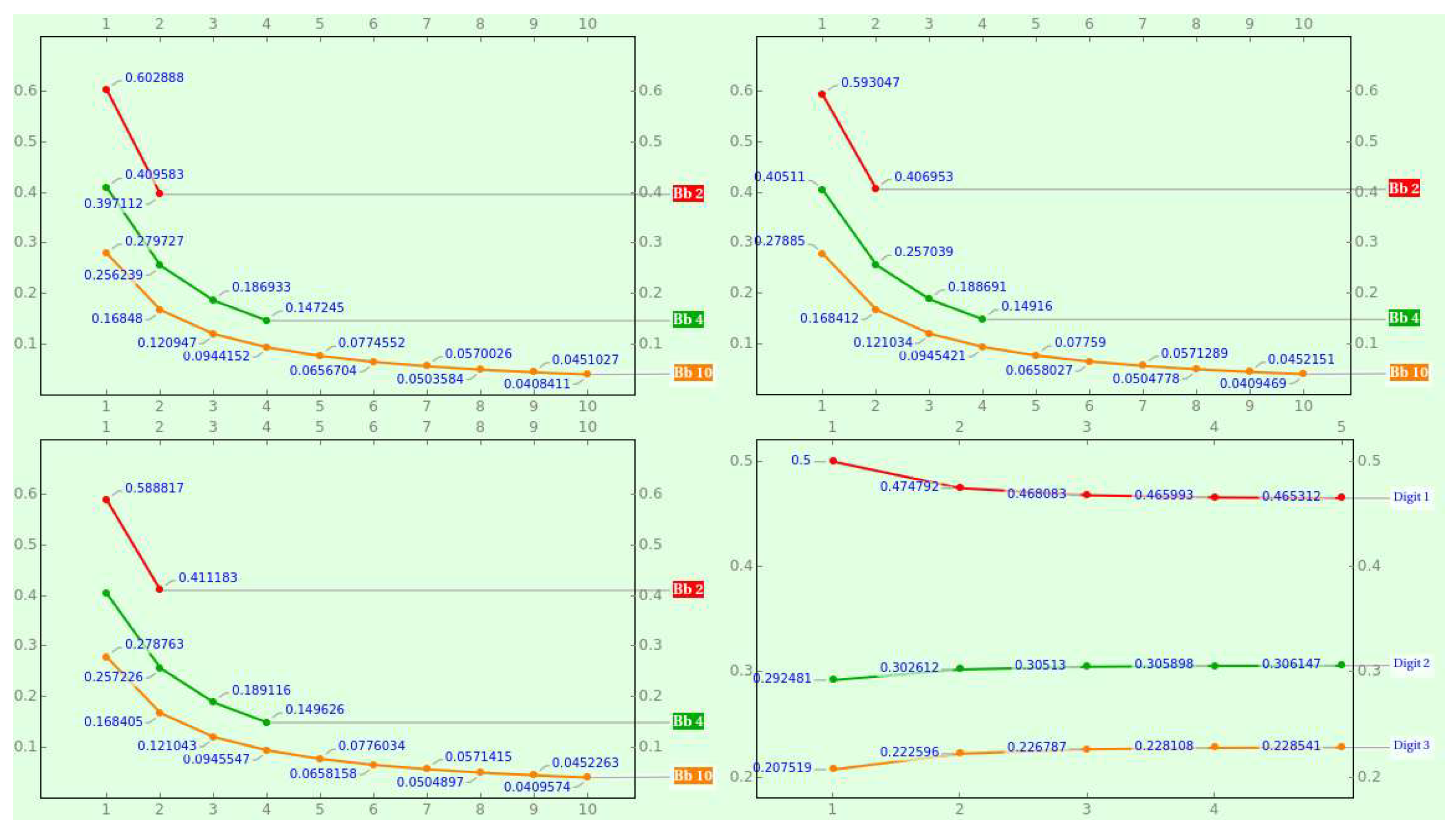

Figure 3 shows the PMF of various bijective radices for consecutive lengths and the hyperbolic progression of the bijective ternary digits as the numeral’s length expands.

Definition (8) also allows us to derive the following PMF.

Definition 10. A numerical dataset is said to satisfy the local NBL for BN if the probability of runing into d as the p-th digit of a bijective -ary numeral, where and , is

Example 10. The chance of picking 1 to 3 as the fifth digit of a bijective ternary numeral is

, and the probability of choosing 1 to as the second digit of a bijective decimal numeral is .

Owing to (10) boils down to (6) if , the local NBL is position-invariant beside radix-invariant.

4. Depleted and Constrained Harmonic Series

The global NBL for BN suddenly appears in the set of Kempner’s curious series. We say a series is curious when the infinite summation of a harmonic series, divergent, is depleted by constraining its terms to satisfy specific convergence conditions. For example, consider the harmonic series missing the terms where "66" appears in their denominator. Most researchers in this fieldwork use decimal representation, but we can generalize the results to any base. Although their terminology refers to the items of a unit fraction’s denominator as digits, for us, these are quanta of a chain because we are handling terms of a harmonic series.

The point is that most depletions result in an absolute mass because a harmonic series is on the verge of divergence. In particular, a harmonic series becomes convergent by omitting a single quantum. For example, the shrunk harmonic series without the terms in which "4" appears anywhere in the decimal representation of the denominator is of the Kempner series. Offhand, convergence comes up because we withdraw most of the terms; of the terms contain a "4" if the random variable ranges from 0 to 9, have at least one "4" if the random variable ranges from 0 to 99, and eventually, most of the terms of any random chain with 100 quanta will contain at least one "4" and will not sum.

Notwithstanding, this explanation is misleading. The weight of the long chains containing a given quantum is lower than that of the short chains. A

series converges slowly [

15] due to the relative and geometrically low contribution of large numerical chains containing

N to the total.

Table 1 summarizes the outcomes of approximated calculations from 1 (

) to

(

). The most stunning feature of the Kempner summations (second column) is that they outline a curve that decreases harmonically.

Every quantum eliminates the same number of terms. means not that "1" is in more terms than "2" or "3" but a heavier mass attributed to the terms with the minor quanta; if we take out , the resulting summation is smaller than when we take out or , and "" is the quantum that contributes less to the total. Note also that although "" is taken as "0" for calculation purposes, the value of proves that BN is underneath.

Considering that a Kempner series is infinite and the set of Kempner series embraces all quanta q represented in bijective decimal, how could we find a better proof that a default probability potential outlines a hyperbolically decreasing function of q?

Since a curious series converges by default of unit fraction terms, the mass share of a quantum globally depends on the reciprocals of the Kempner summations; the third column of the table includes ’s reciprocals normalized to (e.g., ’s relative mass is ). We must underline the relevance of these summations and percentages, reflecting the mass of every quantum irrespective of where it is, in contrast with the global NBL, which indicates the probability mass of a quantum at a given position in a given base.

We introduce two caveats to analyze the NBL weights (fourth column). First, the Kempner distribution conforms with NBL via the average of NBL distributions for different positions, which is NBL, too [

16]. For instance,

is, in principle, the average of quantum 1’s probabilities at first (

), second (

), third (

), fourth (

), et cetera position according to (5). Second, because the distribution of the

nth quantum quickly tends to be uniform (

for each of the ten quanta from the fifth position), we must suspect that there exists a threshold position above which the contributions to the quantum’s weight do not count; otherwise, the resulting mean distribution will end up reaching uniformity despite the differences that the Benford distribution makes at the first positions. Consequently, the last column calculates

as the NBL frequency averaged only over the first nine positions. Averaging ten positions also gives an excellent approximation (with a mean error of

) to the distribution of Kempner masses, but nine positions deliver the minimal total mean error of

.

Can we extrapolate this result in

to any value of

? If affirmative, PN would ignore a natural significand’s quanta from the

th place, agreeing with claims often made by mathematicians [

17], physicists [

18,

19], and engineers [

20] about the illogicality of a PN system carrying excessive digits in calculations of any type, regardless of the discipline.

We surmise that a bijective

b-ary chain

c that fulfills

is physically elusive. The universe in base

would cope with at most

nesting levels, each distinguishing between

b possible quanta. The "physical resolution"

would estimate the scope of quanta a computational system like the cosmos can naturally operate, much as a native resolution describes the number of pixels a screen can display.

In [

21], the author contrives an efficient algorithm for summing a series of harmonic numbers whose denominator contains no occurrences of a particular numerical chain. As a result of the calculations, a harmonic series in base

b omitting a chain of length

n (regardless of its specific quanta) might converge approximately to

This conjecture means that the contribution of linearly more extended chains to an endless series is geometrically lesser. For instance, the harmonic series where we impede the occurrence of the decimal numeral "314159" is about , whereas the same sum omitting "only" "3" is , times as low. Thus, large numerical chains would be exponentially inconsequential.

More general constraints allow several occurrences of a given quantum to calculate summations positively. Let

be the sums of the

b-ary reciprocals of naturals that have precisely

n instances of the quantum

q. For example, omitting the terms whose denominator in decimal representation contains one or more 6 is the particular case

. The sequence of values

S decreases and tends to

regardless of

q [

22].

Except for the gap from to , where the total increases, the summation falls as we raise the constraining quantity of quanta. What is the reason? It is not that we get more terms with n qs than terms containing qs, but that the longer the chain, the lighter the contribution. Furthermore, when , , whereas if , , i.e., increments of n near the origin produce significant drops and vice versa, increments of n far from the origin produce negligible drops. Although we have not statistically tested "the number of quanta" for compliance with NBL, we can again conclude that while small is a synonym for solid and discernible, huge numerical chains are fragile and hardly convey differences.

Instead of imposing absolute constraints, we can allow in a term arbitrarily many quanta

q irrespective of the position and number so long as the proportion of

qs remains below a fixed parameter

. In [

23], the authors prove that the series converges if and only if

. In decimal, while Kempner’s original series implies

, where no term containing a given quantum contributes to the summation, the complete harmonic series means

, where any density is allowed, i.e., we keep all the reciprocals.

For instance, if we consider the constraint "allow a rate of of 7s at most", the term disappears ( of 7s), but neither (no 7s) nor ( of 7s) does. While the series converges in , it no longer converges above the threshold . Note that the archetype of the Pareto law appears naturally; on average, of the unit fractions, those with the highest quantum density, offset the remaining . Moreover, this result engages with our surmise concerning the physical resolution of a universal computational system. Again, densities of b quanta or more are intractable. A PN system must restrict itself to chains with less than b quanta to guarantee the operability of coded data and avoid overflow conditions.

5. Conclusion

The canonical PMF is a probability inverse-square law that, taken as a brute fact, allows us to derive the global and local NBL. The canonical PMF, NBL subsidiaries, and PN run in parallel.

All the NBL formulas of standard PN are translatable to BN. For example, the standard and bijective decimal system global and local laws are similar but different, meaning that the precision of NBL is nonessential, while the supporting positional scale is what matters. In particular, the global NBL with standard base corresponds to the global NBL with bijective base (def. 1 and def. 3), and the local NBL with standard radix corresponds to the local NBL with bijective radix (def. 6 and def. 8).

In contrast with standard PN, the BN expressions of NBL have a very high level of generality, to the point that both are length- (def. 4 and def. 9) and position-invariant (def. 5 and def. 10), in addition to other well-known invariances. We also provide the formula for the harmonic entropy of the global NBL (def. 2), which is not evident, and the logarithmic entropy of the local NBL (def. 7).

We have proved that the Kempner distribution reflects the global version of NBL for BN and confirms a fundamental tendency toward minor numbers. The study of constrained harmonic series mainly teaches us that the specific digits involved in the restraining chain do not matter, whereas its length does. More generally, long chains or high densities of quanta are "rare" and deliver slender harmonic terms. In contrast, short chains or low quantum densities are regular and cheap, producing heavy harmonic terms that lead to convergence of the series if eliminated. In other words, only usual and economic constraints can impede the divergence of a harmonic series. More generally, positions with decreasingly lower exponents on a harmonic or logarithmic scale have exponentially less and less weight; a natural resolution in PN plausibly exists.

Regardless of the number system, we must conceive of positional scales as hyperbolic spaces in a broad sense, harmonic in the first place, and logarithmic in the second place. NBL correlates accessibility with smallness, proximity, scarcity, or brevity. The generality of the NBL expressions for BN reinforces the thesis that this law is comprehensively universal.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This article includes original contributions. Readers can contact the author for further inquiries. The programming code producing the data presented in this study is available on request.

Acknowledgments

We herein express our tribute to some personalities and entities influencing this work. The UNED incited a scientific instinct and a generalistic approach to problem-solving. Working for Indra enabled a pragmatic approach to figuring out any crisis and awareness of the productive character of our universe. We greatly thank José Mira for his capacity for motivation. We apologize in advance for omitting laudable references. We sincerely appreciate those offering comments and critical insight on this version.

Conflicts of Interest

The author (ORCID 0000-0003-3980-5829) declares no conflicts of interest. The author asserts that only scientific rigor, significance, and clarity drive the high-level goals of this work. It contains no known minor or significant incongruencies, errors, or inaccuracies. The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work and declares that he has no competing financial or nonfinancial interests directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication. No personal relationships have influenced the content of this work. It has not been published elsewhere in any form or language, partially or in whole. The author claims to have committed no intentional ethical wrongdoing related to this paper, including self-plagiarism, plagiarism, far-fetched self-citations, conflict of interest, inaccurate authorship declarations, and unacceptable biases concerning the references. This work respects third-party rights such as copyright and moral rights.

References

- Benford, F. The Law of Anomalous Numbers. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 1938, 78, 551–572. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T.P. A Statistical Derivation of the Significant-Digit Law. Statistical Science 1995, 10, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors, the Free Encyclopedia. Positional Notation, 2022. [Online; accessed 11-November-2022].

- Berger, A.; Hill, T.P. What is Benford’s Law? Notices of the AMS 2017, 64, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors, the Free Encyclopedia. Bijective Numeration, 2020.

- Rives, J. The Zero Delusion. ResearchGate (Prepint) 2023, p.60. Universe Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.E. A Number System without a Zero-Symbol. Mathematics Magazine 1947, 21, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, R.R. A Logical Alternative to the Existing Positional Number System. Southwest Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 1995, 1, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, J. The Code Underneath. Axioms 2025, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Hill, T. Benford’s Law Strikes Back - No Simple Explanation in Sight for Mathematical Gem. The Mathematical Intelligencer 2011, 33, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisin, N. Indeterminism in Physics, Classical Chaos and Bohmian Mechanics: Are Real Numbers Really Real? Erkenntnis 2021, 86, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempner, A.J. A Curious Convergent Series. The American Mathematical Monthly 1914, 21, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors, the Free Encyclopedia. Differential entropy, 2024. [Online; accessed 10-September-2024].

- Bekenstein, J.D. A Universal Upper Bound on the Entropy to Energy Ratio for Bounded Systems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, R. Sums of Reciprocals of Integers Missing a Given Digit. The American Mathematical Monthly 1979, 86, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Hill, T.P. The Mathematics of Benford’s Law: a Primer. Statistical Methods and Applications 2021, 30, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildberger, N.J. Finite versus Infinite and Number Systems. In Sociology and Pure Mathematics; Insights into Mathematics, YouTube Channel, 2022.

- Dowek, G. Real Numbers, Chaos, and the Principle of a Bounded Density of Information. In Proceedings of the Theory and Applications. - Computer Science Symposium in Russia; A. A., B.; Shur, A.M., Eds., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; Vol. 7913, LNTCS, [978-3-642-38535-3].

- Santo, F.D., Undecidability, Uncomputability, and Unpredictability; The Frontiers Collection, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; chapter Indeterminism, Causality and Information: Has Physics Ever Been Deterministic?, pp. 63–79. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B. The Cost of Accuracy. Semiconductor Engineering (Low Power - High Performance) 2018.

- Schmelzer, T.; Baillie, R. Summing a Curious, Slowly Convergent Series. The American Mathematical Monthly 2008, 115, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, B. A Curious Result Related to Kempner’s Series. The American Mathematical Monthly 2008, 115, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubeck, B.; Ponomarenko, V. Subsums of the Harmonic Series. The American Mathematical Monthly 2018, 125, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).