1. Introduction

It has become increasingly evident that the understanding of numerous facets of cell biology and DNA physiology necessitates an interdisciplinary approach, encompassing biology, synthetic biology, and electronics.

The flux of the interfacing processes is bidirectional: the electronic circuits have the capacity to mimic the biological schematics, and vice versa, and the interpretation of the events ruling the biological processes can be supported by the electronic devices. The mapping, modelling, and design of biological structures could quickly become dependent on a bio-electronic approach that combines automated design, modelling, analysis, simulation, and quantitative fitting of measured data [

1,

2,

3].

Simple circuit schemes have been devised for regulating precise molecular homeostasis through synthetic biological operational amplifiers functioning in living cells [

4]. In this way, the combination of electronics and cell biology promises novel strategies to control cell processes. Therefore, deeper insights into cell physiology and the application of technological solutions to several cell system alterations can be achieved only by relying on the fundamentals of the quantum world [

5,

6].

A great part of the current biological knowledge is based on studies carried out under non-physiological conditions, such as those derived from the protein chain reaction (PCR), neglecting to reflect the impact of the high temperature on cells. Furthermore, many of the mechanisms involving the motion of the proteins along with a 2 meters-long structure, the DNA, wrapped onto histones and confined into a micrometer space, the nucleus, are still debated and subject of theorization [

7,

8].

We believe that these gaps could be filled by opening our minds to new horizons. The current prospective review has the ambitious intent of tracing unexplored paths for understanding the proteins-DNA interplay. Our standpoint is based on the experimentally acquired personal experience: the discovery and characterization of the Nuclear Aggregates of Polyamines (NAPs), which are supramolecular structures enveloping the DNA as briefly surveyed in the following specific paragraph [

9]. In our opinion, the discovery of NAPs has been delayed by their supramolecular nature. However, the self-assembly of polyamines in a phosphate-rich chemical environment and their wrapping onto the DNA strands should be recognized as an obvious chemical event, since Coulomb interactions and weak interactions simply rule it.

NAPs were described by us about twenty years ago [

10] as supramolecular aggregates interacting with DNA, reproduced

in vitro [

10,

11], and investigated structurally and functionally with the key contribution by scientists with multidisciplinary expertise [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The polyamine–phosphate interaction that we described for the first time in 2002 [

10] has been largely reported in several biological settings [

20,

21] as well as in the field of bio-inspired material science [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In this review, we will focus our coverage on the possibility that the presence of NAPs provides native DNA with a long electronic circuit.

The DNA conductive abilities have been long investigated to explain some mechanisms of DNA physiology as well as to devise possible nanotechnological applications. DNA-based nanowires have been considered for several decades as an alternative to silicon-based microelectronics, which could enable reducing the size of current devices by a thousand-time factor. The possible high rates of charge transfer have been explored for both native and modified DNA strands. However, based on direct measurements, only short DNAs can transport the electronic charges [

28,

29,

30,

31]. An overlap between the π orbitals of neighboring base pairs has been firstly and for a long time considered the structural factor underlying the mechanisms of charge transport, being the most plausible from a theoretical point of view. However, it became evident soon that not all base couplings were effective for charge transfer, as the insertion of A:T base pairs into constructs having GC-rich domains decreased their conductance exponentially with the length of the A:T base pairs sequences [

32]. The semiconducting activity seems limited to the G - G coupling, since the stacking of an alternative series of five guanines resulted in the best DNA base conductive asset, although further elongation of guanine blocks did not determine a coherent charge transport across the DNA [

28,

29,

30,

32].

More recently, the “traditional” theory linked to the base-to-base charge transfer has taken a hit. The research team led by Daniel Porath [

33] demonstrated a charge-transport of relatively high current (tens of nano-amperes) through single 30-nm-long double-stranded DNA. However, the presence of even a single discontinuity (‘nick’) in both strands determined the suppression of the electron current, despite the absence of any discontinuity among the coupling of the bases. Therefore, the authors established that “the backbones mediate the long-distance conduction in dsDNA, contrary to the common belief in DNA electronics” [

28,

29,

30,

31,

33]. In the backbones, the only possible electron hopping stems from the phosphate ions [

34,

35,

36], and consequently, the world of DNA electronics seems to be advanced from the bases to the phosphate era.

On the other side, it should be considered that charge transport processes strongly depend on the environmental conditions and that the experimental context (vacuum, nitrogen atmosphere, and cryogenic temperature) of the above-described referenced works is very different from the cellular environment. Therefore, the outcomes of these studies cannot be directly applied to cell physiology. Furthermore, when charge transport happens in such a complicated environment as a living cell, one should consider many types of charge flow due to negative or positively charged ions that happen in parallel, whose influence, as a rule, cannot be evaluated in the experimental setting. However, all the above-mentioned works certainly contributed to the knowledge advancement in this challenging research field.

Anyway, why electronics is so important for cellular functions?

For at least a century of investigations, nerve electrophysiology has been well-defined and it has been established that nerve transmission is a fast electro-conductive phenomenon, since a nerve impulse can travel up to 288 km/h. The fastest transmission occurs in nerves having a myelin sheath, and the sensory nerves are faster than the motor ones [

37]. Differently, the functions of the cell nucleus regulated electronically appear more complex and enigmatic; thus, for their better understanding, it is necessary to widen the frame to the cell as a whole.

2. The Electronic Domain of a Cell

In one second, a single cell in the human body performs about 10 million chemical reactions, which overall require about one picowatt of power and is approximately 10,000 times more energy-efficient than any nanoscale digital transistor, the fundamental building block of electronic chips [

38].

Such energetic effort is sustained by mitochondria, highly specialized subcellular structures. All cells in the human body, except the erythrocytes, contain one or more, sometimes several thousand-mitochondria. The main role of mitochondria is to produce the chemical energy needed by eukaryotic cells, providing ATP through the phosphorylation of ADP. This process relies on respiration and plays a key role in regulating cellular metabolism [

39]. The central set of reactions involved in ATP production is collectively known as the citric acid cycle, or the Krebs cycle. ATP is extremely rich in chemical energy, especially stowed between the second and third phosphate groups. The conversion of ATP into ADP plus one inorganic phosphate releases 12 kCal/mole energy

in vivo. Such a relatively massive release of energy from the cleavage of a single chemical bond, along with the whole cycle of charging and discharging, is what makes ATP so versatile and valuable to all forms of life.

ATP-ADP system can be charged up at one site and transported to another site for discharge, somewhat like a dry cell battery [

40]. The transport of ATP and electrons is intrinsically linked. The electron transport chain is accomplished by a series of protein complexes and electron carrier molecules within the inner membrane of mitochondria that generate ATP for energy. Electrons are passed along the chain of contiguous protein complexes until they are donated to oxygen. During the passage of electrons, protons are pumped out of the mitochondrial matrix across the inner membrane and into the intermembrane space. The accumulation of protons in the intermembrane space creates an electrochemical gradient that causes protons to flow down the gradient and back into the matrix through ATP synthase. This movement of protons provides the energy for the production of ATP [

41].

Each mitochondrion is surrounded by a layer of a strong static electric field (EF). Thus, since mitochondria occupy about 22 % of the overall cellular volume, the cytosolic medium is under the influence of a strong static EF [

42]. The EF of cytosol was evaluated by 30 nm “photonic voltmeters”, 1000-fold smaller than traditional voltmeters, which enabled a complete three-dimensional EF profiling throughout the entire volume of living cells [

43,

44]. These devices can be calibrated externally and then exploited to determine the EF inside any living cell or cellular compartment, ascertaining that the EF (-3.3 x 10

6 V/m) from the mitochondrial membranes penetrates much deeper into the cytosol than previously estimated. The EF associated with the polarized mitochondrial membrane dropped significantly and rapidly at increasing distances, and although the cytosol EF intensity never achieved the maximal value measured at the mitochondrial level, the EF was still measurable several microns away from the mitochondria [

43]. Cunningham

et al. [

44] determined a radially directed EF from the nuclear membrane into the cell membrane, evidencing the decline of the EF at increasing distance from the nuclear membrane, as well as its local perturbation caused by spontaneous transient depolarizations in mitochondrial membrane potential. Transient openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [

45,

46] are believed to produce these rapid changes in the membrane potential (ranging from <10 mV to>100 mV) and hence, they are named mitochondrial flickers [

47].

Mitochondria have been considered, since ever, the battery apparatus of the cell. The interest in these organelles has been recently rekindled by several research lines concerning cell bioelectronics. A deeper exploration of their way of functioning, and the acquired awareness of their role as very powerful energy donors, consent -only now- to fully understand that mitochondria support cell functions considered unbelievable so far.

2.1. The Mitochondrion Can Be Imagined as a Tesla-Type Battery Supply

Mitochondria have a smooth outer membrane and a wrinkled inner membrane that has inward projected folds, known as the cristae. Until recently, it has been believed that the purpose of the inner membrane's wrinkly texture was simply to increase the surface area for energy production and that each mitochondrion was a single battery since conventional microscopy had been seeing that cells function properly with a small number of very extended mitochondria.

Wolf

et al. [

48] changed this viewpoint by visualizing the inner side of mitochondria by utilizing the airyscan super-resolution microscopy, thus mapping the energy production and the internal voltage distribution. Of note, both the images and the measures indicated that each crista is electrically independent, functioning as an autonomous battery since if one of them was damaged and stopped functioning, the others maintained their membrane potential. Within individual cristae, clusters of proteins, such as MICOS complex and OPA1 [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62], control and regulate the boundaries. In electronic terms, these proteins separate the cristae from their neighbors acting as electrical insulators, essential for the maintenance of a specific transmembrane potential (Δψm). In turn, Δψm for cristae of a single mitochondrion varies, indicating that cristae function as independent bioenergetics units. It has been already established that, when cells are depleted of the protein clusters, mitochondria turn into one giant “battery”, becoming sensitive to damage and energetically less efficient [

63,

64,

65].

All these pieces of evidence indicate that the energetic apparatus of the mitochondrion works like a Tesla vehicle battery apparatus: an array of microscopic batteries, functioning in a very sophisticated assembly of several thousand small individual cells connected electrically in a series and parallel combination [

66]. These small batteries, arranged in a large network, let the vehicles rapidly charge, efficiently cool, and quickly use a large amount of power to accomplish their tasks, all characteristics required for a physiologically working cell.

2.2. The Cellular Response Times Are Shorter Than Imagined

Sun

et al. [

67] demonstrated that the rapid up-regulation of endogenous mechanoresponsive genes depends on the demethylation of the histone H3 lysine-9 trimethylated (H3K9me3). After a cell was stretched through a magnetic bead, they recorded that mechanoresponsive endogenous genes transcription factor early growth response 1 (Egr-1) and Caveolin 1(Cav1) were directly activated by the force exerted at the cell surface in less than one millisecond, without requiring cytoplasmic intermediates, enzymes, or signaling molecules. Namely, force-induced up-regulation of the transcription at the nuclear interior is associated with the demethylation of H3K9me3, whereas no transcriptional up-regulation of H3K9me3 was recorded near the nuclear periphery, where H3K9 histones are already highly methylated. Therefore, histone demethylation is associated with Pol II recruitment and increases the force-induced transcription of Egr-1 and Cav1 inside the nuclei. The force-induced transcription up-regulation occurred at low force frequency, i.e., 10-20 Hz rather than 100 Hz, and the gene activation started very shortly after a cell was stretched and hundreds of times faster than chemical signals can travel: in comparison, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) or Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) signaling takes ~5-10 sec to diffuse/translocate into the nucleus to activate genes, hundreds of times slower than force-induced gene activation [

68]. Confirming their previous results [

69], these authors also showed that the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene activation is detected within 10-15 sec after the force application using the 5'-probes. Being the rate of transcription ~50 bps per second, so that after 10-15 sec 500-750 bps are transcribed, it was suggested that gene activation starts as soon as the chromatin is stretched. Overall, the transcription starts <1 ms after the chromatin stretching, probably via nearby RNA Pol II recruitment and/or stalled RNA Pol II activation (Ning Wang, personal communication, 08 Apr 2020). These data suggest that positive charges function as brakes and negative charges as speeding factors of the rotational movement of H3 histones, through the methylation-demethylation system [

67].

Messenger proteins are additional examples of surprisingly fast movements in the cellular setting. The localization and movements of a messenger protein are highly regulated by Coulomb interactions between a radially directed EF (from the cell nucleus into the cell membrane) and the net protein charge (determined by isoelectric point, phosphorylation state -each phosphate adds roughly 2 negative charges- and the cytosolic pH). In fact, due to the Coulomb interactions of the phosphorylated negatively charged dominions with an intracytoplasmic EF, messenger proteins were found to move rapidly (<0.1 s) from the cell membrane to the perinuclear cytoplasm [

44]. The time scales of the above-described biological processes refer to not directly related macroscopic or microscopic events that, in all cases, are very fast.

From an electronic point of view, all these data indicate that a relevant part of cell physiology is based on Coulombic forces and that an efficient circuit of electrons has to be assured to the DNA for such rapid responses to a variety of stimuli [

9]. However, any comparison to silicon-based logic or memory devices in the cellular and nuclear context should be made with the awareness that the bulk solid-state electronic processes and the complex chemical reactions in aqueous solutions operate in substantially different environments.

3. Electron Current Is Crucial for the Nucleus's Physiology

Despite a detectable cell membrane-to-nuclear membrane-oriented electronic flux corresponding to defined electric lines of force, in the cytoplasm a true electron circuit originating from the mitochondrial electron source is not present. Differently, well-defined conductive systems have been explored in the cell nucleus.

As stated in the Introduction section, DNA has been considered an interesting model of a bioorganic circuit. However, the semiconductive abilities of natural and engineered DNA constructs resulted unsupported. Anyway, from the great number of studies produced it appears clear that the electron circulation through π–π moieties depends on the ordered alignment of aromatic moieties since their semiconducting features originate from intra-supramolecular interactions [

28,

70]. Explicitly, native and non-native DNA bases are not properly connected to guarantee an efficient and continuous charge transfer, as it would be needed for a true circuit deputed to work physiologically.

Another factor that precludes the charge transfer is the alignment of the moieties onto the double strands that are essentially "insulated", as the periphery of the bases is flanked by the poorly conducting sugars [

30]. Strikingly, the intra-base conductivity has been recently confirmed by an investigation based on the interruption of the backbone integrity due to the presence of two nicks, one per strand, which abolished the DNA conductivity [

33].

It is possible to conclude, that the ideal factors for an efficient DNA-based electronic circuit are two: 1) a perfect stacking of aromatic structures and 2) the presence of well-aligned phosphate ions. Both these conditions can be met by a supramolecular structure forming nanotubes that envelop the strands and take full contact with the DNA bases and backbone phosphates, as we have pointed out in NAPs nanotubes.

4. The Nuclear Aggregates of Polyamines

In native conditions, the double helix strands are enveloped by a polymeric system of nanotubes formed by the polyamines and phosphate self-assembled in cyclic, pseudo-aromatic, structures, namely the Nuclear Aggregates of Polyamines (NAPs) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. NAPs have the potential characteristics of a powerful electronic apparatus able to assist the DNA in fulfilling its functions [

9]. The basic structure is due to the formation of circular monomers constituted by the electrostatic interaction of polyamine N-termini and phosphate ions. The structural equilibrium of these compounds is reached through cyclization, as indicated by the appearance of an absorption band at 280 nm in assembled NAPs, which is lacking in isolated polyamines. Three compounds, named large (l), medium (m), and small (s) according to their gel permeation chromatography estimated mass of ~8000, 5000, and 1000 Da, respectively, were isolated from the nuclear extracts of many different cells [

10]. The polyamine-phosphate self-aggregation can be easily reproduced in vitro in conditions mimicking the physiologic ones also without the DNA strands template, thus forming cyclic monomers, the in vitro NAPs (

ivNAPs), which share molecular weights, DNA interactive abilities and functions with the extractive counterparts, demonstrating to be their suitable substitutes [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The NAPs-DNA complexation is regulated by the negative charges of the backbone phosphates. However, hydrogen bonds, stacking, and other weak interactions regulate the alignment of the circular basic elements onto minor DNA grooves. The final effect is the formation of tubular structures enveloping the entire DNA [

12,

13].

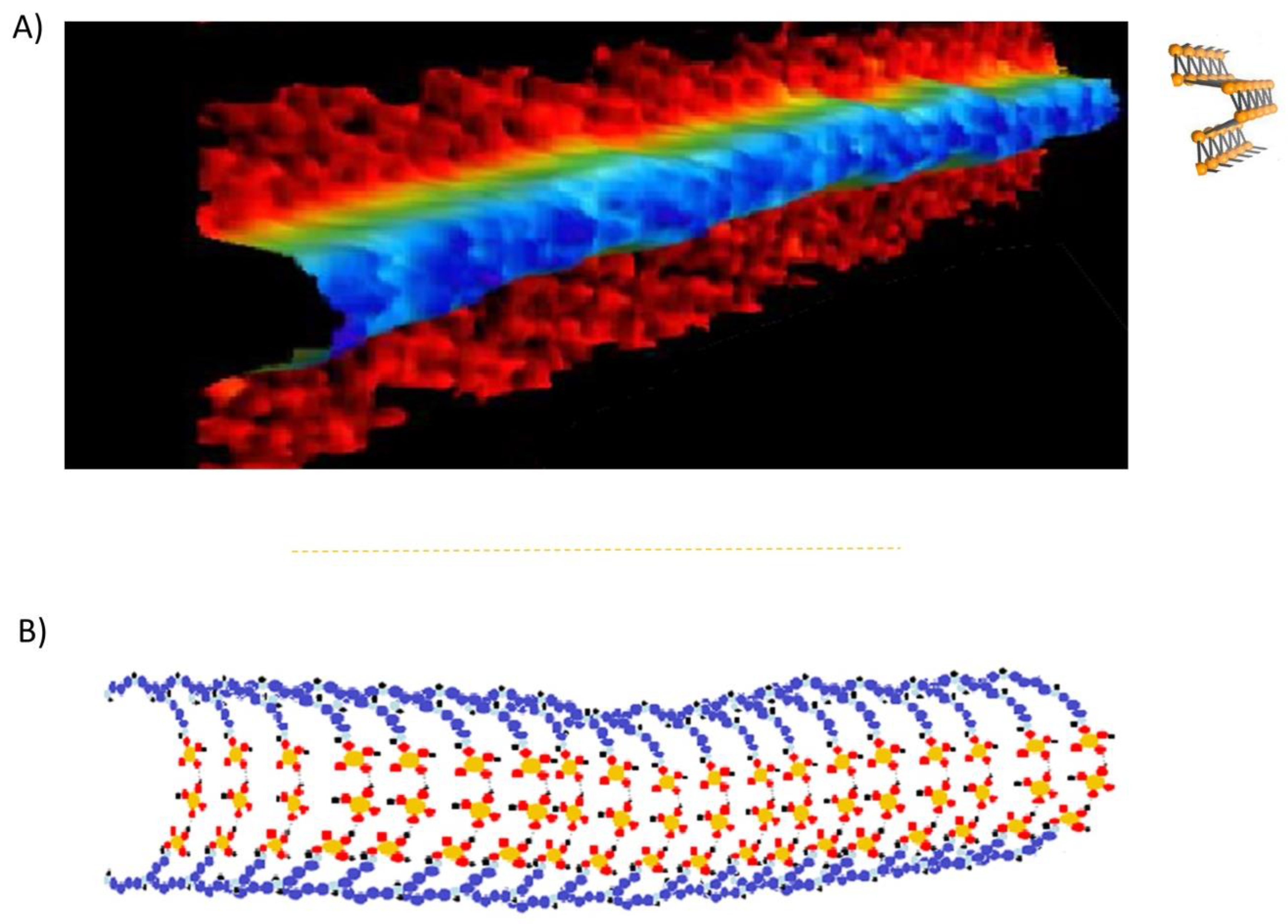

The NAP polymeric assembly onto the DNA is strictly dependent on the interaction with the strands, and the backbone phosphate is probably directly involved in their structuration in the DNA groves. The three molecular assemblies we have detected and characterized are mono-cyclic or penta-cyclic structures. The complexation of each one of the three NAPs onto the DNA strands assists the conformational transitions of DNA, ascribed to A, B, or Z DNA forms, respectively (

Figure 1 a, b). This complex structuration results in a nanotubular frame that wraps and protects the DNA strands from DNase-induced degradation and potentially from γ-radiation, in a condition of dynamic assistance during the conformational movements [

10,

12,

13,

17]. Atomic Force Microscopy images of the NAPs wrapping genomic DNA are shown in

Figure 2.

These structures, synergistic with the DNA strands, have peculiarities that distinguish them from carbon nanotubes, which are practically formed by a 2D graphene sheet rolled up to form a hollow cylinder. The properties of carbon nanotubes include high thermal and electrical conductivity and mechanical resistance [

71]. However, graphene-based materials and structures [

72] cannot assemble and disassemble at physiological conditions, as the NAPs nanotubes do. Furthermore, NAPs have a conductivity track, a sort of nanoribbon phosphorene [

73] structure in their external face that is essential for the protein-DNA interaction [

16].

4.1. Nuclear Aggregates of Polyamines as Possible Semiconductors

A semiconducting material with excess electrons, typically obtained by phosphorus contamination, is named an n-type semiconductor. Given their chemical and structural characteristics NAPs might be considered a typical semiconducting material that, due to the phosphorus doping, assumes the ability to produce additional free electrons that can be displaced by neighboring atoms. Upon application of an electric potential across the n-type semiconductor, electrons move from the negative to the positive poles [

74]. In "organic" semiconductors formed by aromatic moieties [

75], the delocalized electrons are, according to the "frontier molecular orbital theory” [76], shifted among interacting molecular orbitals in such a way that the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) supplies the entire negative charge coming from the electron pairs, while correspondingly the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) operates as an acceptor [

77], thus enabling a directional electronic flow, provided that a nonzero energy gap between HOMO and LUMO occurs [

78,

79,

80].

However, the strict contiguity among homogenous monomers is a requirement for charge transfer, which seems not to be met by natural DNA bases. In contrast, NAPs have homogenously stacking monomers able to assemble also without the DNA strand template [

15], so probably allowing the long-range charge transfer along the nanotubes [

9]. Furthermore, the disposition of rows of phosphate ions in these pseudo-aromatic structures [

19] could ensure the necessary negative doping for an effective progression of the electron charges.

Unfortunately, a direct evaluation of an electric charge transfer depending on the NAPs-DNA structuration has not yet been achieved, and this goal seems very challenging to reach, due to the supramolecular and frail nature of NAP super-aggregation strictly dependent on physiological parameters. Nonetheless, independent of the experimental evidence, the theoretical bases and the morphological results obtained with the use of AFM indicate that NAPs may support an additional important function related to an underlying electronic circuit: the protein motion along the DNA strands (

Figure 3) [

9,

16].

4.2. Nuclear Aggregates of Polyamines and nuclear proteins

Based on experimental evidence [

12,

16] protein-DNA super-aggregation is permitted by the interaction of the positive charges of the proteins and the outward phosphates of NAPs [

19]. The outer surface of the nanotubes has charged elements, which are utilizable for protein interaction due to the presence of phosphate–phosphate complexes (

Figure 3) [

19,

81,

82]. This highly negatively charged region for the presence of the phosphate–phosphate complexes establishes, using strong hydrogen bonds that counteract the repulsive Coulombic forces [

82], a sort of phosphorene nanoribbon [

73] elongated along the double helix, that can potentially be utilized as a track for a carrier-mediated system (

Figure 4) [

9]. Notably, although phosphates are virtually able to engage single hydrogen bonds per side, they have a very high degree of mobility under the repulsive Coulombic force and, therefore, form an unrestricted streamflow of negative charges. The cooperation of several carrying modules [

9] in protein motion has to be considered mandatory since in the Z-DNA form, which is the type of DNA involved in active tasks such as gene expression and transcription [

83], there is the cooperation of a 5-nanotube-super-aggregates (

Figure 1) [

10,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

18]. A negative charge setting of the DNA side interacting with proteins is indispensable for the activation of the hypothesized carrying apparatus (

Figure 4) [

9].

HMGB1 proteins, histones, and in general all binding proteins, have two major possibilities for modifying the charges of their interactive sites through phosphate groups, as they can interact electrostatically -negatively (2e

−) charged phosphate ions

vs positively (1H

+) charged amino groups-, and/or to become phosphorylated at the amino acid (serine, lysine, and threonine) [

84,

85,

86,

87]. Both these possibilities are triggered by the establishment of hydrogen bonds among phosphate–phosphate groups, as a phospho-protein moiety maintains its propensity of establishing hydrogen bonds with the reactive groups [

88,

89,

90,

91]. This carrying system transfers the protein alongside the DNA up to the sequence-specific DNA-binding domain destination [

91], employing a piece of machinery made of phosphates (

Figure 4) working as an industrial robot. Recently, D’Acunto hypothesized that the ability of proteins to identify consensus sequences in DNA is based on the quantum entanglement [

92,

93] of π-π electrons between DNA nucleotides and protein amino acids. More explicitly, recognition and interaction should rely on π-π interactions established between the DNA nucleobases and the aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Phe, His, or Trp) of the proteins.

The quantum entanglement has now crossed the boundary of the infinitesimal world since purely quantum mechanical phenomena of “large” objects [

94,

95] have been demonstrated: vibrating aluminum membranes akin to two tiny drums, each around 10 micrometers long, provided the first direct evidence of quantum entanglement between macroscopic objects [

96]. Apart from possible practical applications, these experiments address how far the observation of distinct quantum phenomena can push into the macroscopic realm [

97]. The structure of NAPs fits well with this perspective.

Linear protein translation is not the only transfer function attributable to NAPs. The rotation of histones too might be similarly regulated, since the angular momentum is the rotational equivalent of the linear momentum [

9].

All these considerations point to phosphate ions as crucial elements of DNA electrophysiology.

4.3. Role of Phosphates in electronic DNA conductivity

Phosphorene, a monolayer of black phosphorus [

98,

99,

100], is a 2D nanomaterial that shows excellent conductive abilities in analogy with graphene structuration and is considered a promising natural semiconductor for biomedical applications. Furthermore, the high carrier mobility and large fundamental direct band gap of phosphorene make it a promising material for applications in electronics. Phosphorene nanoribbons have been produced to enhance the phosphorene application in nanoelectronics [

73]. Interestingly, DNA bases have shown interactive abilities in phosphorene surface [

99] and phosphorene nanoribbon-based experiments [

101]. The interaction of DNA bases with phosphorene nanoribbons and the nanoribbon-like configuration of phosphates located in the apical region of NAPs disposed along the DNA grooves bring further support to the hypothesis that proteins assume fast-moving capacity alongside the DNA using the NAPs intermediation, and this can happen without the impairment of an efficient base-protein recognition necessary for a correct reading process.

Phosphorene nanoribbons [

73] and the phosphate-phosphate hydrogen-bonded series found in the apical region of NAPs (the nanoribbon-like phosphorene) differ for the type of inter-phosphate bonding and, consequently, for the charge transfer pathways. In doped zig-zag nanoribbons, the conductance mostly originates from the charge travelling through the chemical bonding at the proximity of zigzag edges [

102] and is characterized by a strong anisotropy in the transport properties along with the zigzag and armchair directions [

103]. In NAPs, the electron transfer across the hydrogen bond interfaces that hold on each phosphate with the adjacent one could be even more efficient. It has been demonstrated that the electron transfer across an H-bond may occur via a proton-coupled or proton-uncoupled pathway with a transfer efficiency comparable to that of one of the π conjugated bridges and superior to σ bonds [

104].

The existence of a phosphate-phosphate electronic track assured by NAPs enveloping the DNA is also based on theoretical calculations of e-hopping distances. The electron hopping over the aligned phosphates should overcome the distance of about 3 Angstroms, the length of a hydrogen bond [

105] to establish a current of electrons, and this seems the case of NAPs-DNA complexes since the possible extent of an electron hopping ranges from 10 to 40 Angstroms [

106]. The long-range electron transfer studied in “Porphyrin Oligomer Bridged Donor−Acceptor (D-B-A) Systems” [

107] is a possible model for understanding which way electrons run across the NAPs pseudo phosphorene nanoribbons. Over long distances, the electron transfer between the donor (D) and the acceptor (A) requires an intermediate bridge (B), since electrons are very unlikely to travel through space. In this D−B−A system, the bridge functions as the conducting medium sustaining the electronic communication between the D and the A sites. The bridge also confers spatial separation of the charges, ultimately creating a long-lasting charge-separated state. Accordingly, in the past decade, a vast variety of molecular bridges have been designed, and their ability to mediate either electron or energy transfer has been investigated. Among them, π-conjugated bridges have shown promising potential for many applications, due to their high degree of electronic delocalization [

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113]. A supramolecular system may be ideally suited for electron transfer (see

Figure 5) [

9]. These systems can operate at physiological temperatures [

107] and are composed of monomeric super-assembled modules that exhibit defined electronic delocalization. Additionally, the donor, acceptor, and bridge states within these systems are nearly resonant [

107]. All of these characteristics are potential features of NAPs nanotubes.

5. Conclusions

Investigation of the structure and functions of biological systems, especially DNA, can be improved by applying electronic principles. Cell functions are accomplished with the energetic support of the mitochondrial apparatus that works in every single cell like a powerful coordinated reservoir of energy and electrons. Active electron fluxes occur in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Signal proteins rapidly migrate from the cell membrane to the nucleus under the driving force of electronic gradients and DNA-binding proteins may quickly shuttle along the strands at the board of nanocarriers that, utilizing nanotubular structures enveloping the strands as a scaffold, are guided by quantum entanglements to their appropriate sites of interaction onto the DNA bases. Protection, rotation onto the histones, and conformational changes of the DNA strands are also assured by these supramolecular nanotubes functioning as effective electronic circuits. A big part of this scenario is already established and the remaining is within reach. NAPs play a central role in this.

The self-organization of polyamines and phosphate ions that constitutes an important example of a noncovalent association in the biological setting [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

21] is also replicated in to design of new materials [

23,

25,

27,

114,

115,

116]. New scenarios in the applicative field could be disclosed by the exploitation of the phosphate-phosphate interactions. Recent experiments have confirmed that phosphorene nanoribbons are inherently both semiconducting and magnetic without the need for low temperatures or doping. This discovery opens up new possibilities for spintronic devices that utilize electron spin instead of charge. Consequently, it paves the way for the development of innovative computing technologies, quantum devices, flexible electronic items, and next-generation transistors [

117]. In that matter, Wong's team proposed a "Unipolar n-Type Black Phosphorus" transistor [

118].

However, 2D semiconducting materials are costly and have not completely satisfactory performances [

119]. Differently, the NAP system potentially has many suitable applications in biomaterials and nanoelectronics since NAPs are cheap, flexible, scalable, and biodegradable materials [

11]. For example, long circuits could be easily realized utilizing agarose gel tracts obtained by the migration of genomic DNA pre-incubated with each one of the three NAPs [

9].

Long-range π−π conjugation has been considered a prerequisite for the identification and design of organic semiconductors [

120,

121,

122]. In this perspective, Irimia-Vladu

et al. [

123] showed that hydrogen-bonded molecules are promising candidates for the establishment of a novel class of organic semiconductors: “When the purity, the long-range order and the strength of chemical bonds, are considered, then the hydrogen-bonded organic semiconductors are the privileged class of materials having the potential to compete with inorganic semiconductors”. They further state: “The hydrogen-bonded ones are air-stable materials, easily processable into thin films characterized by a long-range order and resemble their covalently bonded inorganic counterparts”. We believe that we have found one of these - the NAPs- wrapping the genomic DNA. Further research is needed to detect and demonstrate the electronic conductivity of the DNA-NAPs complex; however, the necessary experiments are challenging to conduct in a biological environment.

The NAPs-DNA protein transfer system, which should be regarded as a strictly physiological apparatus, has intriguing similarities with a newly developed smart device consisting of protein-based motors that move along DNA nanotubes by utilizing biomolecular motor dynein and DNA-binding proteins. This nano-construct allowed researchers to arrange binding sites along the track, control the direction of movement locally, and achieve multiplexed cargo transport using different motors. The integration of these microscale technologies has resulted in the creation of cargo sorters and integrators that can automatically transport molecules according to programmed DNA sequences on branched DNA nanotubes [

124]. Furthermore, hybrid black phosphorus hydrogels are now considered promising and innovative for biomedical applications [

125,

126].

All these advancements are consistent with the innovative perspective opened by our research work.

Finally, in the current era in which the nano-chips are at the base of any possible advancement in technology and biomedicine, and their production by major economic and technological powers –i.e., the U.S.A and China- seems to be ended in the bottleneck of the dependence from the technological industry of a single "small" state -i.e., Taiwan-, it is mandatory to explore new scenarios [

127,

128].

We believe that a deeper exploration of biosystems, particularly DNA nanocircuits, aimed at maximizing their potential, could be both useful and sustainable. Nature is a remarkable teacher, and following its guidance would be wise.

Abbreviations

AFM, atomic force microscopy; Cav1, Caveolin 1; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; EF, electric field; EGF, epidermal growth factor; Egr-1, early growth response 1; HMGB1, High Mobility Group Box 1; HOMO, highest occupied molecular orbital; H3K9me3, histone H3 lysine-9 trimethylated; His, histidine; LUMO, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; MICOS, mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system; NAP, nuclear aggregates of polyamines; OPA1, optic atrophy 1; PDFGF, platelet-derived growth factor; Phe, phenylalanine; Trp, tryptophan; Tyr, tyrosine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.A. methodology, G.I. and G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.A.; writing—review and editing, G.I. and G.P. and L.D.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Teo, J.J.Y.; Sarpeshkar, R. The Merging of Biological and Electronic Circuits. iScience 2020, 23, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selberg, J.; Gomez, M.; Rolandi, M. The Potential for Convergence between Synthetic Biology and Bioelectronics. Cell Syst 2018, 7, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, Z.; Meloni, G.N.; Tran, P.; Zerfass, C.; Sena, G.; Hayashi, Y.; Grant, M.; Contera, S.A.; Minteer, S.D.; Kim, M.; et al. Bioelectrical understanding and engineering of cell biology. J R Soc Interface 2020, 17, 20200013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Teo, J.; Banerjee, A.; Chapman, T.W.; Kim, J.; Sarpeshkar, R. A Synthetic Microbial Operational Amplifier. ACS Synth Biol 2018, 7, 2007–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, A.; Adams, B.; Ringsmuth, A.K.; Ferretti, M.; Gruber, J.M.; Hendrikx, R.; Schuld, M.; Smith, S.L.; Sinayskiy, I.; Kruger, T.P.J.; et al. The future of quantum biology. J R Soc Interface 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, J.; Lilliu, S. Quantum Biology. Scientific Video Protocols 2020, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendandi, A.; Dante, S.; Zia, S.R.; Diaspro, A.; Rocchia, W. Chromatin Compaction Multiscale Modeling: A Complex Synergy Between Theory, Simulation, and Experiment. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimatore, G.; Tsuchiya, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Kasperski, A.; Giuliani, A. Self-organization of whole-gene expression through coordinated chromatin structural transition. Biophysics Reviews 2021, 2, 031303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino, L. Native DNA electronics: is it a matter of nanoscale assembly? Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12268–12275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, L.; Di Luccia, A. Polyamines interact with DNA as molecular aggregates. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS 2002, 269, 4317–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luccia, A.; Picariello, G.; Iacomino, G.; Formisano, A.; Paduano, L.; D'Agostino, L. The in vitro nuclear aggregates of polyamines. The FEBS journal 2009, 276, 2324–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, L.; di Pietro, M.; Di Luccia, A. Nuclear aggregates of polyamines are supramolecular structures that play a crucial role in genomic DNA protection and conformation. The FEBS journal 2005, 272, 3777–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino, L.; di Pietro, M.; Di Luccia, A. Nuclear aggregates of polyamines. IUBMB Life 2006, 58, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Picariello, G.; D'Agostino, L. DNA and nuclear aggregates of polyamines. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2012, 1823, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacomino, G.; Picariello, G.; Sbrana, F.; Di Luccia, A.; Raiteri, R.; D'Agostino, L. DNA is wrapped by the nuclear aggregates of polyamines: the imaging evidence. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacomino, G.; Picariello, G.; Sbrana, F.; Raiteri, R.; D'Agostino, L. DNA-HMGB1 interaction: The nuclear aggregates of polyamine mediation. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1864, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Picariello, G.; Stillitano, I.; D'Agostino, L. Nuclear aggregates of polyamines in a radiation-induced DNA damage model. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2014, 47, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picariello, G.; Iacomino, G.; D'Agostino, L. Phosphate-Induced Polyamine Self-Assembly. In Encyclopedia of Biomedical Polymers and Polymeric Biomaterials, Mishra, M., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, 2015; Volume 8, pp. 5951–5964. [Google Scholar]

- Picariello, G.; Iacomino, G.; Di Luccia, A.; D'Agostino, L. Mass spectrometric analysis of in vitro nuclear aggregates of polyamines. Rapid communications in mass spectrometry : RCM 2014, 28, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Beuerman, R.; Verma, C.S. Mechanism of polyamine induced colistin resistance through electrostatic networks on bacterial outer membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, K.; Groger, C.; Sumper, M.; Brunner, E. Biomimetic silica formation: analysis of the phosphate-induced self-assembly of polyamines. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2005, 7, 2812–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomozik, L.; Gasowska, A.; Bregier-Jarzebowska, R.; Jastrzab, R. Coordination chemistry of polyamines and their interactions in ternary systems including metal ions, nucleosides and nucleotides. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2005, 249, 2335–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmisollé, W.A.; Irigoyen, J.; Gregurec, D.; Moya, S.; Azzaroni, O. Supramolecular Surface Chemistry: Substrate-Independent, Phosphate-Driven Growth of Polyamine-Based Multifunctional Thin Films. Advanced Functional Materials 2015, 25, 4144–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, V.E.; Martinelli, H.; Ramirez, M.d.l.A.; Ritacco, H.A.; Andreozzi, P.; Moya, S.E. Polyphosphate Poly(amine) Nanoparticles: Self-Assembly, Thermodynamics, and Stability Studies. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2019, 35, 14300–14309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, H.; Montagna, M.; Dianat, A.; Gutierrez, R.; Bobeth, M.; Cuniberti, G. Exploring the organic–inorganic interface in biosilica: atomistic modeling of polyamine and silica precursors aggregation behavior. BMC Materials 2020, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Dangerous liaisons: anion-induced protonation in phosphate–polyamine interactions and their implications for the charge states of biologically relevant surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 8612–8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreozzi, P.; Simó, C.; Moretti, P.; Porcel, J.M.; Lüdtke, T.U.; Ramirez, M.d.l.A.; Tamberi, L.; Marradi, M.; Amenitsch, H.; Llop, J.; et al. Novel Core–Shell Polyamine Phosphate Nanoparticles Self-Assembled from PEGylated Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) with Low Toxicity and Increased In Vivo Circulation Time. Small 2021, 17, 2102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, Y.A.; Voityuk, A.A.; Ratner, M.A. DNA base pair stacks with high electric conductance: a systematic structural search. ACS nano 2012, 6, 8216–8225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Beratan, D.N.; Li, Y.; Tao, N. Engineering nanometre-scale coherence in soft matter. Nat Chem 2016, 8, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genereux, J.C.; Barton, J.K. Mechanisms for DNA charge transport. Chemical reviews 2010, 110, 1642–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Monroy, K.L.; Renaud, N.; Drijkoningen, J.; Cortens, D.; Schouteden, K.; van Haesendonck, C.; Guedens, W.J.; Manca, J.V.; Siebbeles, L.D.; Grozema, F.C.; et al. High Electronic Conductance through Double-Helix DNA Molecules with Fullerene Anchoring Groups. The journal of physical chemistry. A 2017, 121, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu; Zhang; Li; Tao. Direct Conductance Measurement of Single DNA Molecules in Aqueous Solution. Nano Letters 2004, 4, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravel, R.; Huang, H.; Polycarpou, G.; Polydorides, S.; Motamarri, P.; Katrivas, L.; Rotem, D.; Sperling, J.; Zotti, L.A.; Kotlyar, A.B.; et al. Backbone charge transport in double-stranded DNA. Nature nanotechnology 2020, 15, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, R.; Sarma, M. Low-Energy Electron Interaction with the Phosphate Group in DNA Molecule and the Characteristics of Single-Strand Break Pathways. The journal of physical chemistry. A 2015, 119, 10130–10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayer, M.; Mansingh, A. Transport Properties of Semiconducting Phosphate Glasses. Physical Review B 1972, 6, 4629–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.J.; Coelho, M.; Dionísio, M.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Raposo, M. Probing radiation damage by alternated current conductivity as a method to characterize electron hopping conduction in DNA molecules. Applied Physics Letters 2012, 101, 123702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.F. Neurophysiology: a Primer; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpeshkar, R. Ultra low power bioelectronics : fundamentals, biomedical applications, and bio-inspired systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK ; New York, 2010; p. xviii, 889 p. [Google Scholar]

- Voet, D.; Voet, J.G.; Pratt, C.W. Fundamentals of biochemistry : life at the molecular level, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, N.J, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, P.D. The ATP synthase--a splendid molecular machine. Annual review of biochemistry 1997, 66, 717–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodish, H.F. Molecular cell biology, 4th ed.; W.H. Freeman: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorný, J. Physical aspects of biological activity and cancer. AIP Advances 2012, 2, 011207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyner, K.M.; Kopelman, R.; Philbert, M.A. "Nanosized voltmeter" enables cellular-wide electric field mapping. Biophysical journal 2007, 93, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.; Estrella, V.; Lloyd, M.; Gillies, R.; Frieden, B.R.; Gatenby, R. Intracellular electric field and pH optimize protein localization and movement. PloS one 2012, 7, e36894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, V.; von Stockum, S.; Antoniel, M.; Fabbro, A.; Fogolari, F.; Forte, M.; Glick, G.D.; Petronilli, V.; Zoratti, M.; Szabo, I.; et al. Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase form the permeability transition pore. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 5887–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P.; Richardson, A.P. The mitochondrial permeability transition: a current perspective on its identity and role in ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2015, 78, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Reilly, C.M.; Fogarty, K.E.; Drummond, R.M.; Tuft, R.A.; Walsh, J.V., Jr. Quantitative analysis of spontaneous mitochondrial depolarizations. Biophysical journal 2003, 85, 3350–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.M.; Segawa, M.; Kondadi, A.K.; Anand, R.; Bailey, S.T.; Reichert, A.S.; van der Bliek, A.M.; Shackelford, D.B.; Liesa, M.; Shirihai, O.S. Individual cristae within the same mitochondrion display different membrane potentials and are functionally independent. The EMBO journal 2019, 38, e101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harner, M.; Korner, C.; Walther, D.; Mokranjac, D.; Kaesmacher, J.; Welsch, U.; Griffith, J.; Mann, M.; Reggiori, F.; Neupert, W. The mitochondrial contact site complex, a determinant of mitochondrial architecture. The EMBO journal 2011, 30, 4356–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabl, R.; Soubannier, V.; Scholz, R.; Vogel, F.; Mendl, N.; Vasiljev-Neumeyer, A.; Korner, C.; Jagasia, R.; Keil, T.; Baumeister, W.; et al. Formation of cristae and crista junctions in mitochondria depends on antagonism between Fcj1 and Su e/g. The Journal of cell biology 2009, 185, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppins, S.; Collins, S.R.; Cassidy-Stone, A.; Hummel, E.; Devay, R.M.; Lackner, L.L.; Westermann, B.; Schuldiner, M.; Weissman, J.S.; Nunnari, J. A mitochondrial-focused genetic interaction map reveals a scaffold-like complex required for inner membrane organization in mitochondria. The Journal of cell biology 2011, 195, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Malsburg, K.; Muller, J.M.; Bohnert, M.; Oeljeklaus, S.; Kwiatkowska, P.; Becker, T.; Loniewska-Lwowska, A.; Wiese, S.; Rao, S.; Milenkovic, D.; et al. Dual role of mitofilin in mitochondrial membrane organization and protein biogenesis. Developmental cell 2011, 21, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, M.; Jans, D.C.; Schulz, C.; Denkert, N.; Kroppen, B.; Hoppert, M.; Jakobs, S.; Meinecke, M. Mic10 oligomerizes to bend mitochondrial inner membranes at cristae junctions. Cell metabolism 2015, 21, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Mourier, A.; Yamada, J.; McCaffery, J.M.; Nunnari, J. MICOS coordinates with respiratory complexes and lipids to establish mitochondrial inner membrane architecture. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarani, V.; McNeill, E.M.; Paulo, J.A.; Huttlin, E.L.; Frohlich, F.; Gygi, S.P.; Van Vactor, D.; Harper, J.W. QIL1 is a novel mitochondrial protein required for MICOS complex stability and cristae morphology. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessenberger, M.; Zerbes, R.M.; Rampelt, H.; Kunz, S.; Xavier, A.H.; Purfurst, B.; Lilie, H.; Pfanner, N.; van der Laan, M.; Daumke, O. Regulated membrane remodeling by Mic60 controls formation of mitochondrial crista junctions. Nature communications 2017, 8, 15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampelt, H.; van der Laan, M. The Yin & Yang of Mitochondrial Architecture - Interplay of MICOS and F1Fo-ATP synthase in cristae formation. Microbial cell 2017, 4, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollweber, F.; von der Malsburg, K.; van der Laan, M. Mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system: A central player in membrane shaping and crosstalk. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular cell research 2017, 1864, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frezza, C.; Cipolat, S.; Martins de Brito, O.; Micaroni, M.; Beznoussenko, G.V.; Rudka, T.; Bartoli, D.; Polishuck, R.S.; Danial, N.N.; De Strooper, B.; et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell 2006, 126, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, S.; Enriquez, J.A.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial Cristae: Where Beauty Meets Functionality. Trends in biochemical sciences 2016, 41, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbes, R.M.; van der Klei, I.J.; Veenhuis, M.; Pfanner, N.; van der Laan, M.; Bohnert, M. Mitofilin complexes: conserved organizers of mitochondrial membrane architecture. Biological chemistry 2012, 393, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Koob, S.; Dikov, D.; Vogel, F.; Reichert, A.S. OPA1 functionally interacts with MIC60 but is dispensable for crista junction formation. FEBS letters 2016, 590, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amchenkova, A.A.; Bakeeva, L.E.; Chentsov, Y.S.; Skulachev, V.P.; Zorov, D.B. Coupling membranes as energy-transmitting cables. I. Filamentous mitochondria in fibroblasts and mitochondrial clusters in cardiomyocytes. The Journal of cell biology 1988, 107, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulachev, V.P. Mitochondrial filaments and clusters as intracellular power-transmitting cables. Trends in biochemical sciences 2001, 26, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glancy, B.; Hartnell, L.M.; Malide, D.; Yu, Z.X.; Combs, C.A.; Connelly, P.S.; Subramaniam, S.; Balaban, R.S. Mitochondrial reticulum for cellular energy distribution in muscle. Nature 2015, 523, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S. Mitochondria work much like Tesla battery packs, study finds. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2019-10-mitochondria-tesla-battery.html.

- Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Mohagheghian, E.; Wang, N. Force-induced gene up-regulation does not follow the weak power law but depends on H3K9 demethylation. Science advances 2020, 6, eaay9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, A.Y.; Kain, K.H.; Klemke, R.L.; Tsien, R.Y. Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters of protein tyrosine kinase activities in living cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001, 98, 15003–15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajik, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, F.; Sun, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhou, W.; Singh, R.; Khanna, N.; Belmont, A.S.; Wang, N. Transcription upregulation via force-induced direct stretching of chromatin. Nature materials 2016, 15, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.H.; Ling, Q.D.; Hou, X.Y.; Huang, W. An effective Friedel-Crafts postfunctionization of poly(N-vinylcarbazole) to tune carrier transportation of supramolecular organic semiconductors based on pi-stacked polymers for nonvolatile flash memory cell. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 2120–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gualdron, D.A.; Burgos, J.C.; Yu, J.; Balbuena, P.B. Carbon nanotubes: engineering biomedical applications. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2011, 104, 175–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, L.; Tozzini, V. Engineering 3D Graphene-Based Materials: State of the Art and Perspectives. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, M.C.; Picco, L.; Russell-Pavier, F.S.; Cullen, P.L.; Miller, T.S.; Bartuś, S.P.; Payton, O.D.; Skipper, N.T.; Tileli, V.; Howard, C.A. Production of phosphorene nanoribbons. Nature 2019, 568, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, V.; Bajpai, R.P.; Bharadwaj, L.M. DNA electronics. EMBO reports 2003, 4, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuchi, H. The discovery of organic semiconductors. Its light and shadow. Organic Electronics 2006, 7, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, C.; Salcedo, R. Computational study of electron delocalization in hexaarylbenzenes. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2014, 19, 3274–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, J.O.; Nielsen, M.B.; Becher, J. Tetrathiafulvalene Cyclophanes and Cage Molecules. Chemical reviews 2004, 104, 5115–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. Physicochemical, Electronic, and Mechanical Properties of Nanoparticles. Engineered Nanoparticles 2016, 77–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, T.; Kinjo, T.; Yamakawa, S.; Asahi, R. Study of the conformation of polyelectrolyte aggregates using coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 5991–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Işıklan, M.; Pramanik, A.; Saeed, M.A.; Fronczek, F.R. Anion Cluster: Assembly of Dihydrogen Phosphates for the Formation of a Cyclic Anion Octamer. Cryst Growth Des 2012, 12, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, I.; Alkorta, I.; Molins, E.; Espinosa, E. Electrostatics at the Origin of the Stability of Phosphate-Phosphate Complexes Locked by Hydrogen Bonds. Chemphyschem 2012, 13, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Zhang, S. Z-DNA: the long road to biological function. Nature Reviews Genetics 2003, 4, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.H.; Shin, J.-S. Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling of HMGB1 Is Regulated by Phosphorylation That Redirects It toward Secretion. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 177, 7889–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.J.; Youn, J.H.; Ji, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Lim, K.J.; Choi, J.E.; Shin, J.-S. HMGB1 Is Phosphorylated by Classical Protein Kinase C and Is Secreted by a Calcium-Dependent Mechanism. The Journal of Immunology 2009, 182, 5800–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res 2011, 21, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.; Avvakumov, N.; Côté, J. Histone phosphorylation: a chromatin modification involved in diverse nuclear events. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, D.J.; Chorny, I.; Groban, E.S.; Wong, S.E.; Levine, E.; Rapp, C.S.; Jacobson, M.P. Strengths of Hydrogen Bonds Involving Phosphorylated Amino Acid Side Chains. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2007, 129, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, T. Why nature chose phosphate to modify proteins. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012, 367, 2513–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, R. Contribution of protein phosphorylation to binding-induced folding of the SLBP-histone mRNA complex probed by phosphorus-31 NMR. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, W.M. Regulation of transcription in eukaryotes by DNA-binding proteins. International Journal of Biochemistry 1992, 24, 1885–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhard, M.; Krenn, M.; Zeilinger, A. Advances in high-dimensional quantum entanglement. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Acunto, M. Quantum biology.pi-pientanglement signatures in protein-DNA interactions. Phys Biol 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, S.; Peterson, G.A.; Shojaee, E.; Lecocq, F.; Cicak, K.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Geller, S.; Glancy, S.; Knill, E.; Simmonds, R.W.; et al. Direct observation of deterministic macroscopic entanglement. Science 2021, 372, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier de Lepinay, L.; Ockeloen-Korppi, C.F.; Woolley, M.J.; Sillanpaa, M.A. Quantum mechanics-free subsystem with mechanical oscillators. Science 2021, 372, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelvecchi, D. Minuscule drums push the limits of quantum weirdness. Nature 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.K.; Clerk, A.A. Macroscale entanglement and measurement. Science 2021, 372, 570–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaraiah, V.; Zeng, Q.; Long, Y.; Liu, Z. Black Phosphorus Nanosheets: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications. Small 2016, 12, 3480–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Xie, X.; Duan, G.; Chen, S.H.; Meng, X.-Y.; Zhou, R. Binding patterns and dynamics of double-stranded DNA on the phosphorene surface. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 9430–9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-x.; Zhao, K.-c.; Jiang, J.-j.; Zhu, Q.-s. Research progress on black phosphorus hybrids hydrogel platforms for biomedical applications. Journal of Biological Engineering 2023, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumawat, R.L.; Pathak, B. Individual Identification of DNA Nucleobases on Atomically Thin Black Phosphorene Nanoribbons: van der Waals Corrected Density Functional Theory Calculations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2019, 123, 22377–22383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, Z.; Asgari, R. Charge transport in doped zigzag phosphorene nanoribbons. Physical Review B 2018, 97, 235406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, Z.; Asgari, R. Phosphorene as a nanoelectromechanical material. Physical Review B 2018, 98, 125427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Shen, D.X.; Meng, M.; Mallick, S.; Cao, L.; Patmore, N.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Zou, S.F.; Chen, H.W.; Qin, Y.; et al. Efficient electron transfer across hydrogen bond interfaces by proton-coupled and -uncoupled pathways. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benco, L.; Tunega, D.; Hafner, J.; Lischka, H. Upper Limit of the O−H···O Hydrogen Bond. Ab Initio Study of the Kaolinite Structure. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2001, 105, 10812–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.B.; Winkler, J.R. Long-range electron transfer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 3534–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert Gatty, M.; Kahnt, A.; Esdaile, L.J.; Hutin, M.; Anderson, H.L.; Albinsson, B. Hopping versus Tunneling Mechanism for Long-Range Electron Transfer in Porphyrin Oligomer Bridged Donor-Acceptor Systems. The journal of physical chemistry. B 2015, 119, 7598–7611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.B.; Svec, W.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Wasielewski, M.R. Molecular-wire behaviour in p -phenylenevinylene oligomers. Nature 1998, 396, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, F.; Segura, J.L.; Martín, N.; Guldi, D.M. Exceptionally Small Attenuation Factors in Molecular Wires. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2004, 126, 5340–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.H.; Sinks, L.E.; Kelley, R.F.; Betzen, L.J.; Liu, W.; Weiss, E.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Wasielewski, M.R. Wire-like charge transport at near constant bridge energy through fluorene oligomers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 3540–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre, G.; Giacalone, F.; Segura, J.L.; Martín, N.; Guldi, D.M. Electronic Communication through π-Conjugated Wires in Covalently Linked Porphyrin/C60Ensembles. Chemistry - A European Journal 2005, 11, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghi, G.; Esdaile, L.J.; Anderson, H.L.; Martin, S.; Bethell, D.; Higgins, S.J.; Nichols, R.J. Comparison of the Conductance of Three Types of Porphyrin-Based Molecular Wires: beta,meso,beta-Fused Tapes, meso-Butadiyne-Linked and Twisted meso-meso Linked Oligomers. Adv Mater 2012, 24, 653–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukegawa, J.; Schubert, C.; Zhu, X.; Tsuji, H.; Guldi, D.M.; Nakamura, E. Electron transfer through rigid organic molecular wires enhanced by electronic and electron–vibration coupling. Nat Chem 2014, 6, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzio, N.E.; Pasquale, M.A.; Marmisollé, W.A.; von Bilderling, C.; Cortez, M.L.; Pietrasanta, L.I.; Azzaroni, O. Self-assembled phosphate-polyamine networks as biocompatible supramolecular platforms to modulate cell adhesion. Biomaterials Science 2018, 6, 2230–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Mitta, G.; Marmisolle, W.A.; Albesa, A.G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Azzaroni, O. Phosphate-Responsive Biomimetic Nanofluidic Diodes Regulated by Polyamine-Phosphate Interactions: Insights into Their Functional Behavior from Theory and Experiment. Small 2018, 14, e1702131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoy, G.E.; Piccinini, E.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. The Effect of Amino–Phosphate Interactions on the Biosensing Performance of Enzymatic Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. Analytical chemistry 2022, 94, 13820–13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoka, A.; Clancy, A.J.; Panjwani, N.A.; Cronin, A.; Picco, L.; Aw, E.S.Y.; Popiel, N.J.M.; Eaton, A.G.; Parton, T.G.; Shutt, R.R.C.; et al. Magnetically and optically active edges in phosphorene nanoribbons. Nature 2025, 639, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Incorvia, J.A.C.; McClellan, C.J.; Yu, A.C.; Mleczko, M.J.; Pop, E.; Wong, H.S.P. Unipolar n-Type Black Phosphorus Transistors with Low Work Function Contacts. Nano Letters 2018, 18, 2822–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-Y.; Su, S.-K.; Wong, H.S.P.; Li, L.-J. How 2D semiconductors could extend Moore’s law. Nature 2019, 567, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon, A.; Cahen, D.; Lindsay, S.; Tomfohr, J.; Engelkes, V.B.; Frisbie, C.D. Comparison of Electronic Transport Measurements on Organic Molecules. Adv Mater 2003, 15, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coropceanu, V.; Cornil, J.; da Silva Filho, D.A.; Olivier, Y.; Silbey, R.; Brédas, J.-L. Charge Transport in Organic Semiconductors. Chemical reviews 2007, 107, 926–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchetti, A. π-Conjugated Polymers for Organic Electronics and Photovoltaic Cell Applications. Chemistry of Materials 2011, 23, 733–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia-Vladu, M.; Kanbur, Y.; Camaioni, F.; Coppola, M.E.; Yumusak, C.; Irimia, C.V.; Vlad, A.; Operamolla, A.; Farinola, G.M.; Suranna, G.P.; et al. Stability of Selected Hydrogen Bonded Semiconductors in Organic Electronic Devices. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 6315–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibusuki, R.; Morishita, T.; Furuta, A.; Nakayama, S.; Yoshio, M.; Kojima, H.; Oiwa, K.; Furuta, K. Programmable molecular transport achieved by engineering protein motors to move on DNA nanotubes. Science 2022, 375, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Zhao, K.C.; Jiang, J.J.; Zhu, Q.S. Research progress on black phosphorus hybrids hydrogel platforms for biomedical applications. J Biol Eng 2023, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Kim, S.; Tian, B. Beyond 25 years of biomedical innovation in nano-bioelectronics. Device 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, Crawford; Jarrell, Dillard; Helene, Fouquet; Reynolds., I. Alan Crawford; Jarrell Dillard; Helene Fouquet; Reynolds., I. The World Is Dangerously Dependent on Taiwan for Semiconductors. Available online: https://www.bloombergquint.com/technology/the-world-is-dangerously-dependent-on-taiwan-for-semiconductors.

- Lee, M.; Weng, M.-H.; Jang, S.-L. The Competitiveness and Future Challenge of the Taiwan Semiconductors Industry. In Technology Rivalry Between the USA and China, C.Y. Chow, P., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).