Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Gas Chromatography

1.2. Gas Chromatography-Flame Ionisation Detection

1.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

1.4. Gas Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry

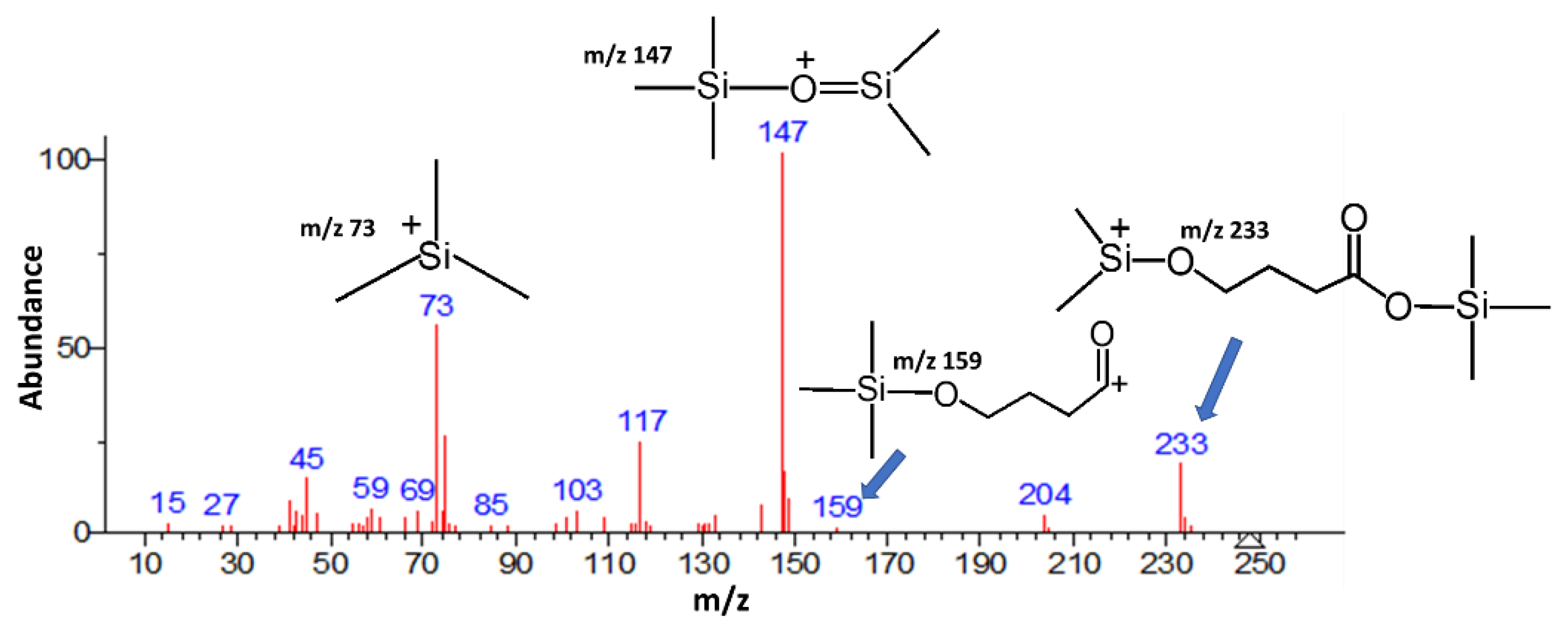

1.5. Derivatisation

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Ethanol

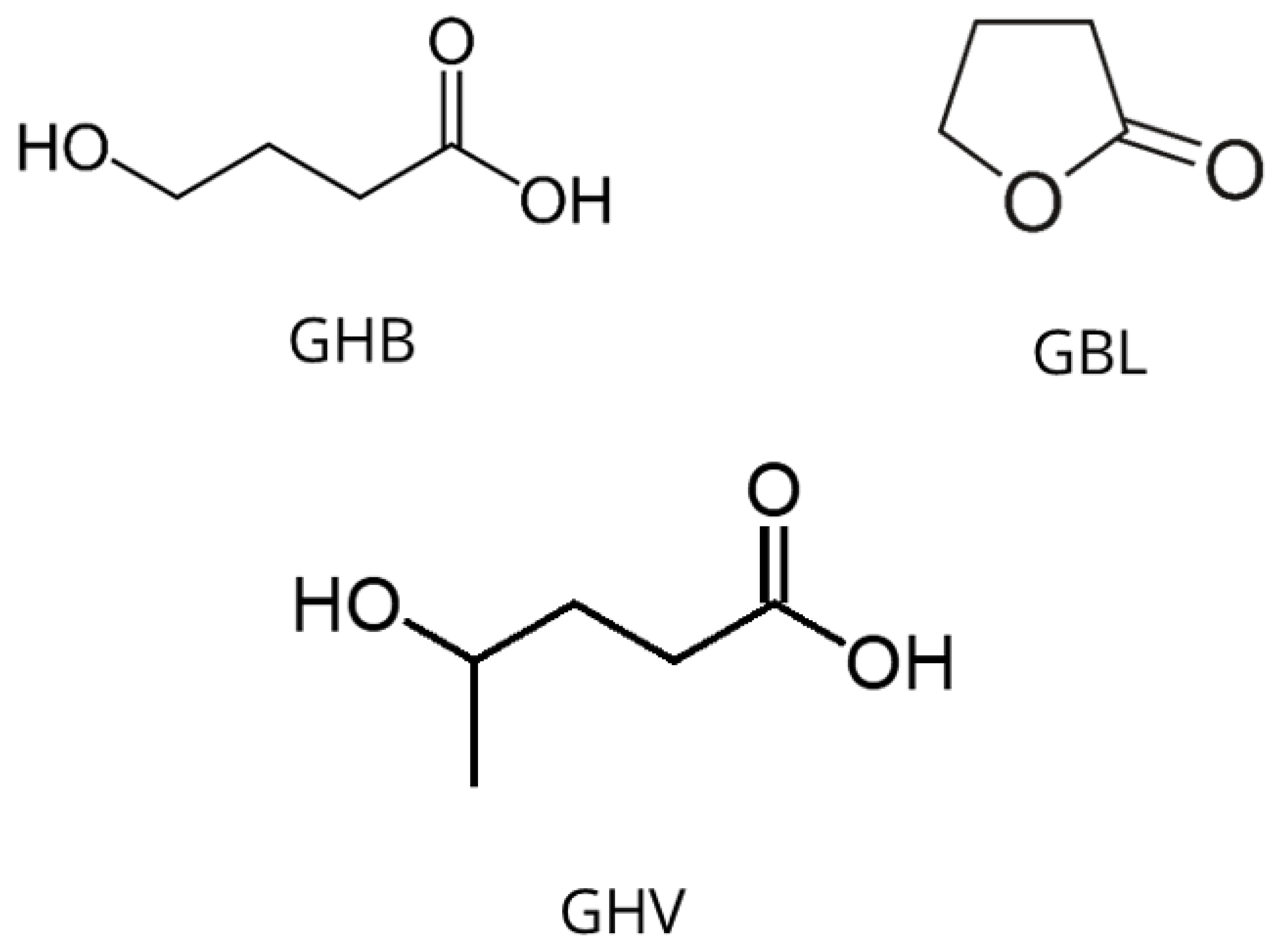

3.2. Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid and Gamma-Butyrolactone

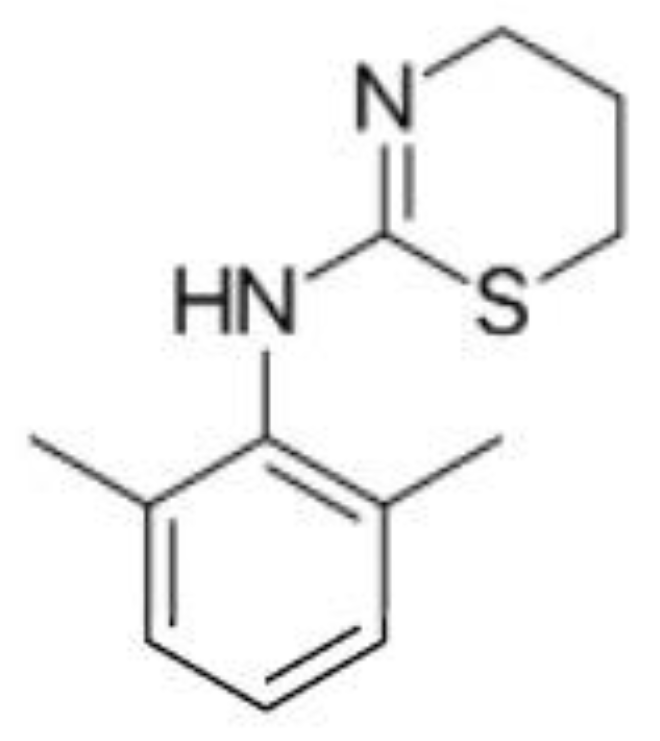

3.3. Xylazine

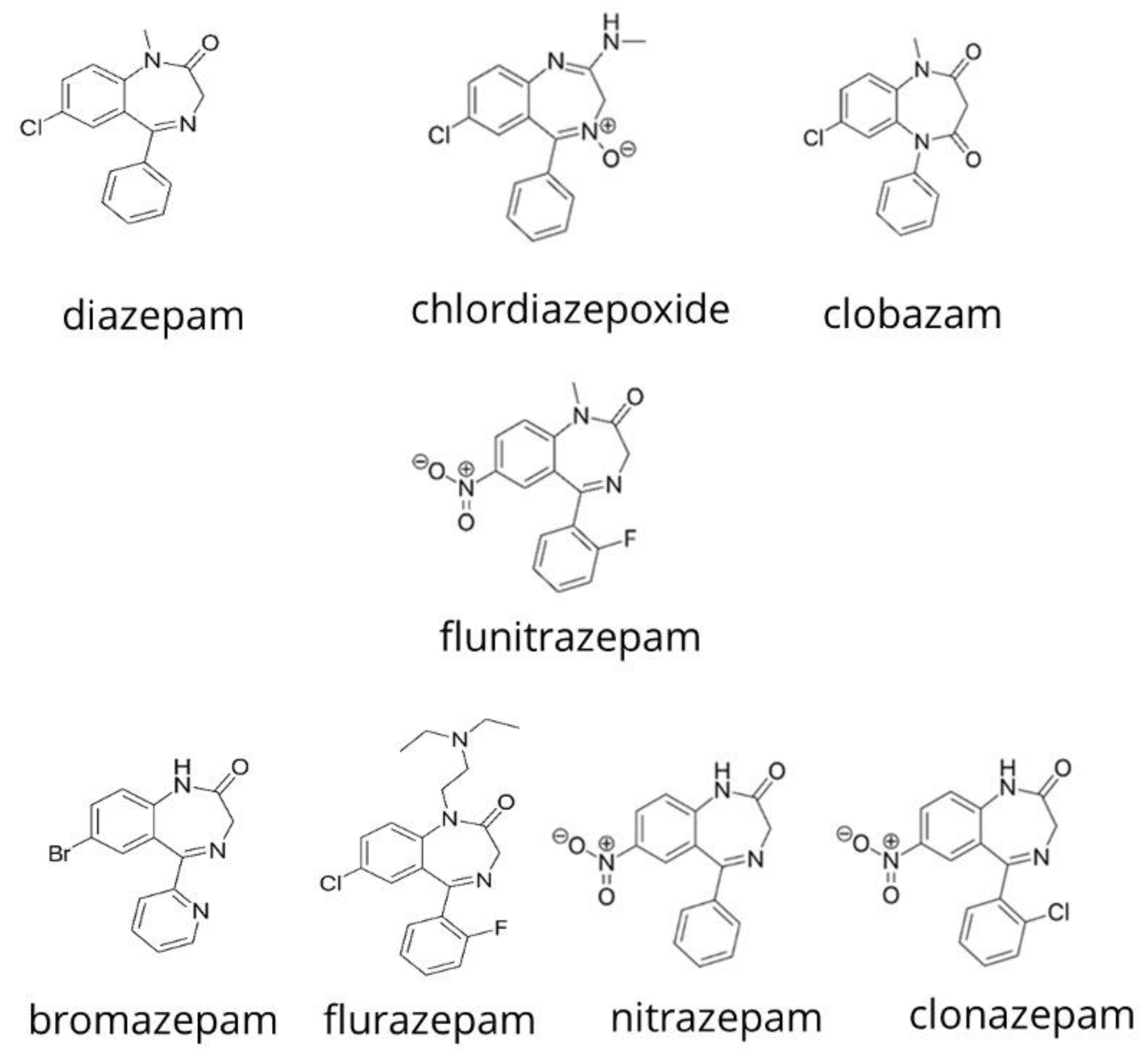

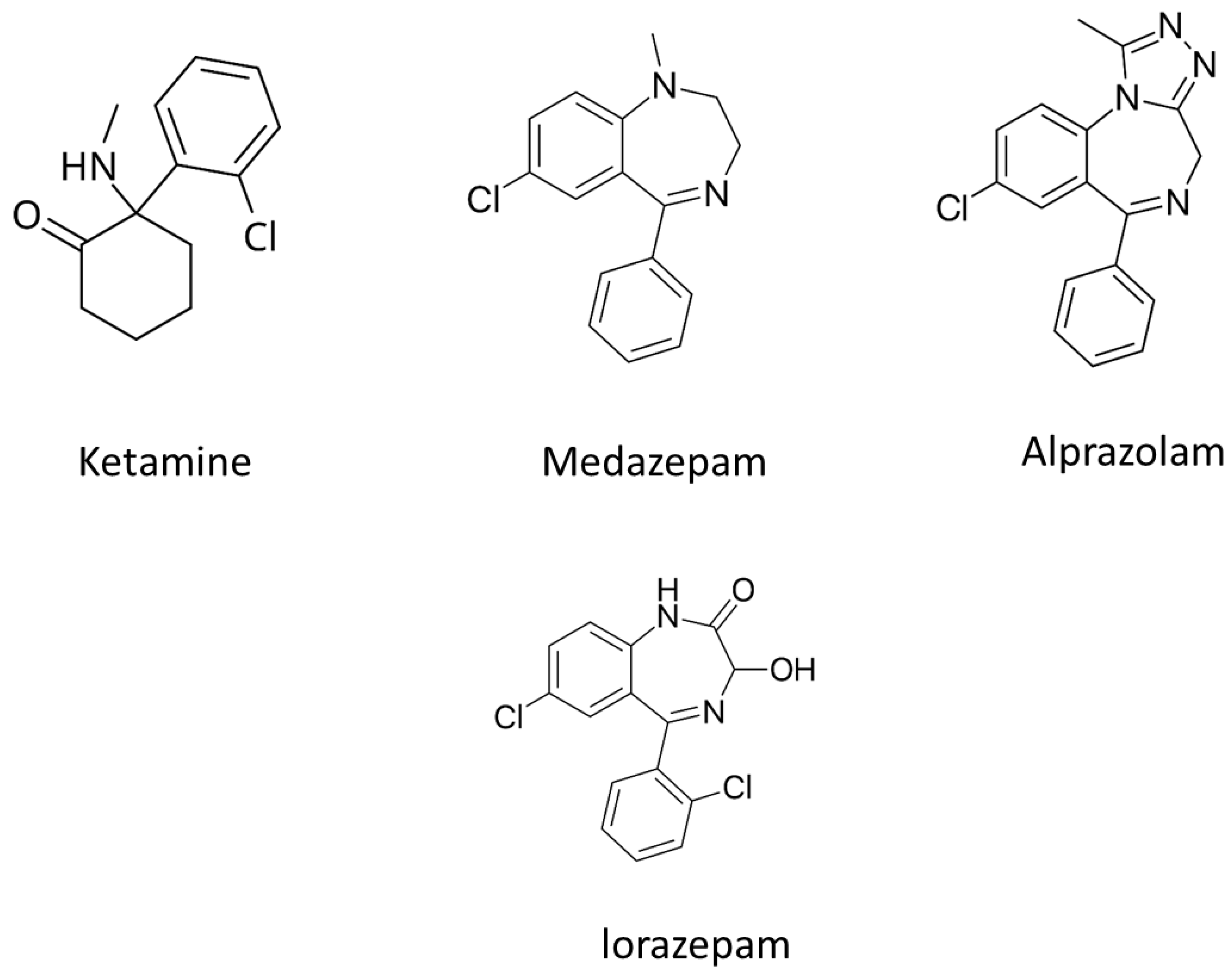

3.4. Benzodiazepines

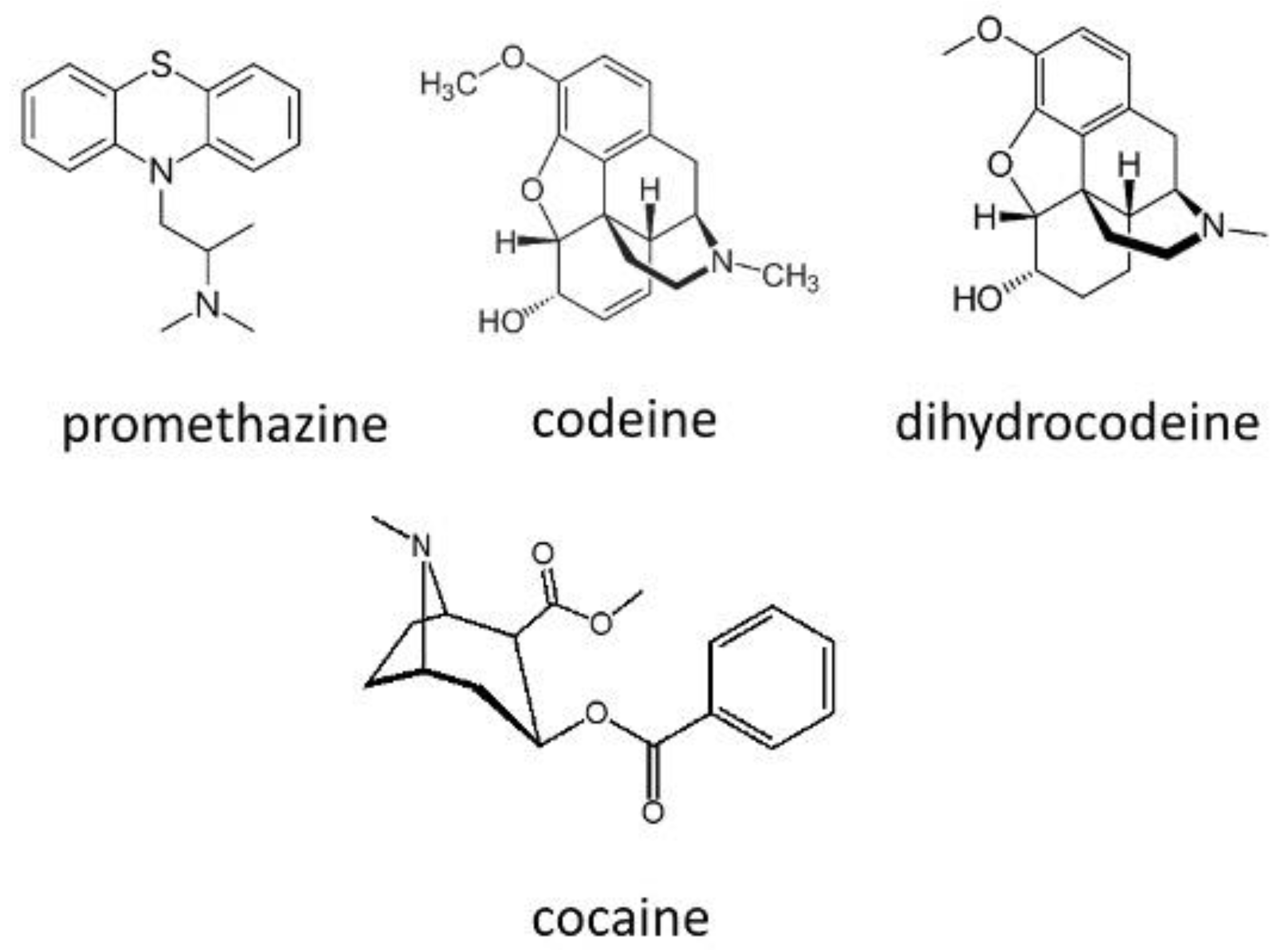

3.5. Other Drugs

| Analytes | Sample Matrix | Derivatisation | Sample Pre-Treatment | Type of GC | LOD/LOQ (mg/L) | Comments | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHB | Beer, wine, rum, Tequila, fruit juice and tonic water | BSTFA 1% TMCS | Ion-exchange solid phase extraction. | SIM GC-MS. HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm I.D, 0.25 µm film | LOQ 0.0067 and LOD 0.0045. | Internal standard GHB-d6. Naturally occurring levels of GHB determined. | [41] |

| GHB | Tonic water and lemon-flavored tonic water | MSTFA | liquid-liquid extraction with acidified ethyl acetate | MRM GC–MS/MS. HP-5MS column 30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.025 µm). | LOQ 0.0025 and LOD 0.0013 | Internal standard GHB-d6. Naturally occurring levels of GHB determined. | [42] |

| GHB and GBL | Beer, juice, spirits, liqueurs, sherry, port, white and red wine | TMS for GHB and conversion via acidification to give total GBL. | LLE with chloroform. | Full scan GC-MS and GC-FID. DB5 MS capillary column, 30 m x 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness. | GHB LOD 3.0 | Internal standard GHB-d6. Naturally occurring levels of GHB and GBL determined. | [43] |

| GHB | Water, Coca Cola, beer, lemonade. | On-fibre derivatisation with BSTFA/TMCS (99:1). | SPME. | GC-MS. A 30-m HP5-MS column with a 0.25 µm film thickness and 0.25 mm | LOQ 1.5. | Internal standard GHB-d6. | [44] |

| GHB and GBL | Water, beer, wine, liquor, coca cola and mixed drinks. | On-fibre derivatisation with BSTFA/TMCS (99:1). | Total vaporisation SPME. | Full scan GC-MS. Extracted ion profiles were used to identify the analyte. | LOD 1.0. | [46] | |

| GHB | Beverage samples and hair. | BSTFA 1% | Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction with ethyl acetate following adjustment to pH 4.3 with ammonium dihydrogen phosphate. | GC-MS/MS. DB-5MS capillary column (30m × 0.32mm ID, 0.25 μm film. | LOD 0.0005. | Internal standard GHB-d6. | [47] |

| GHB | Water, Tropicanas cranberry juice cocktail with Barton s vodka, Coca Cola, Guinness Stouts beer, Coors Lights beer, and Willi Haags Riesling. | BSTFA + TMCS | Dilution in internal standard solution. | GHB was quantitated using the peak area of the ion at m/z 233 and derivatized GHV was quantitated using the peak area of the ion at m/z 117. HP-5, 30 m x 0.25 mm i.d. x 0.25 µm film. | 1.0 pg on column. | Internal standard 1,5-pentanediol. Reverse phase HPLC also investigated. | [48] |

| Xylazine | Energy drink, a carbonated drink, and a fruit-based drink. | None | LLE with dichloromethane following adjustment to pH 11 using 13% sodium hydroxide solution. | Full-scan GC-MS and GC-FID. 5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane (HP5) capillary column (30 m × 0.32 μm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness, | LOD and LOQ were reported at 0.08 and 0.26 respectively by GC-FID. | Internal standard 2,2,2-triphenylacetophenone | [50] |

| Diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, flunitrazepam, bromazepam, flurazepam, nitrazepam, and clonazepam. | Milk-based alcoholic drinks (whiskey creams). | None. | QuEChERS based extraction. | SIM GC-MS. HP-5MS (30 m 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness | LOD and LOQ were in the range of 0.02–0.1 and 0.1–0.5, respectively. | Internal standard medazepam. | [51] |

| Flunitrazepam, clonazepam, alprazolam, diazepam and Ketamine | Peach juice and beer. | None. | LLE with chloroform: isopropanol 1:1 (v/v). | Full scan GC-MS (m/z 50–600). Ion extracted chromatograms used. HP-5MS 30 m x 250 µm i.d. x 0.25 µm film. | LOD between 1.3 and 34.2. LOQ 3.9 and 103.8. | Internal standard medazepam. | [52] |

| Diazepam, midazolam, and alprazolam | Tap water, fruit juices, and urine | None. | SPE combined with dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction | GC-FID. HP-5 30 m x 0.32 mm and 0.25 µm film thickness | LODs of between 0.00002 - 0.00005 | [54] | |

| Diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and ketamine | Flavoured milk, juice, water, tea and beer | None. | Fabric phase sorptive extraction (FPSE) | Full scan GC-MS with subsequent processing to give ion-extracted chromatograms | LODs of between 0.020–0.069 | Food samples of chocolate, cream, and cake also investigated. | [55] |

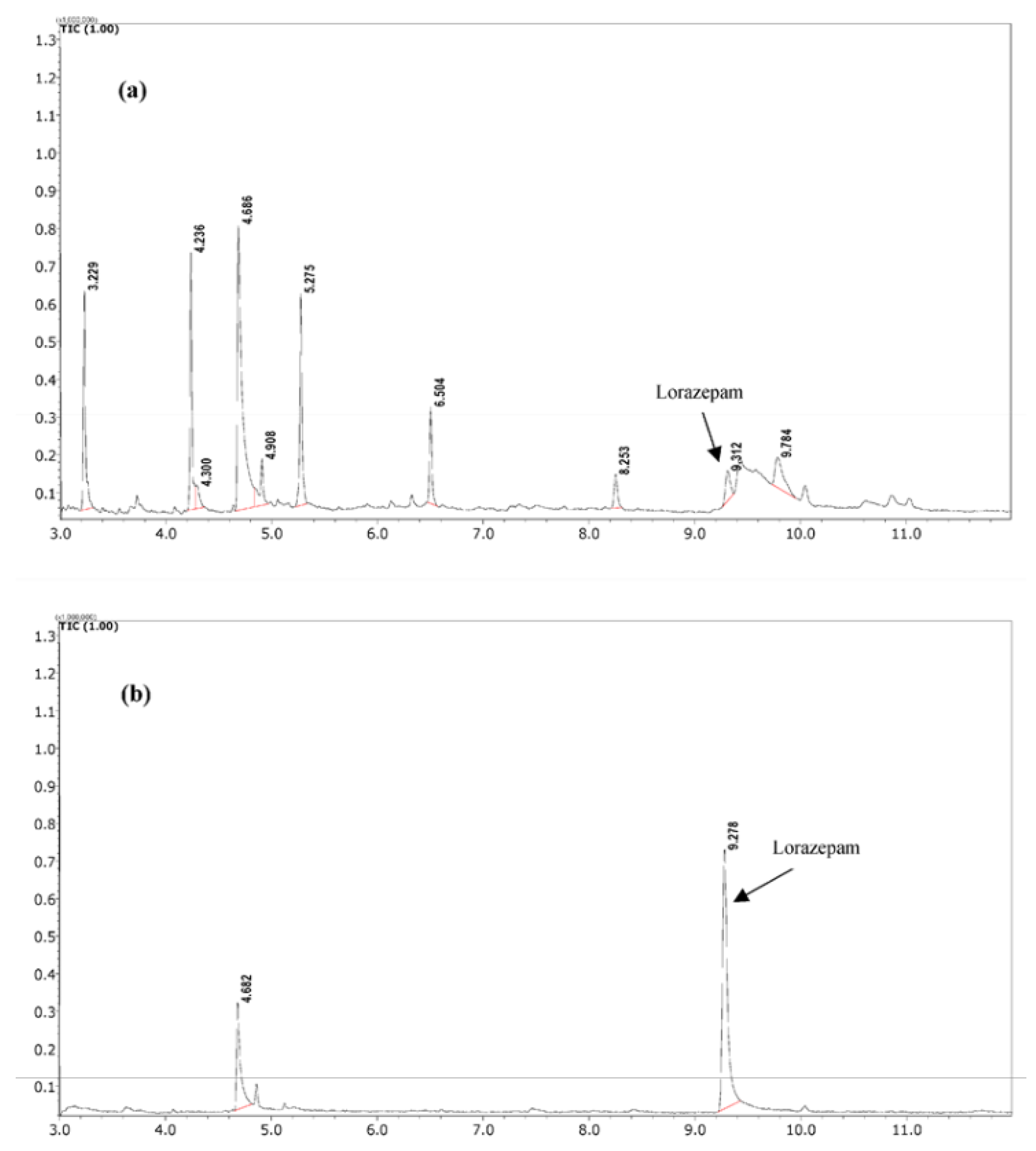

| Lorazepam | Tea | None. | Cellulose paper sorptive extraction (CPSE) | GC-MS in the SIM mode using m/z 275, 303, 239. Txi-5Sil MS capillary column (30 m length x 0.25 mm internal diameter x 0.25 µm film thickness) with a stationary phase of 95% dimethylpolysiloxane and 5% phenyl. | LOD 0.05 | Cream biscuits also investigated. | [56] |

| Codeine and promethazine | “Dirty Sprite” beverage formulated from a mixture of soft drink, and cough medicine. | None. | LLE with 1-chlorobutane following adjustment to pH ≥9 with ammonium hydroxide solution. | Full scan and SIM GC-MS. DB-5 ms, 30 m, i.d. 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm | LOD/LOQ were 0.3/0.9 for cocaine, 0.3/1.0 for promethazine, 0.3/1.0 for dihydrocodeine, and 0.3/1.0 for codeine, respectively. | Dihydrocodeine, and cocaine also determined. Internal standards: promethazine-D3, codeine-D3, cocaine-D3 and dihydrocodeine-D6. | [57] |

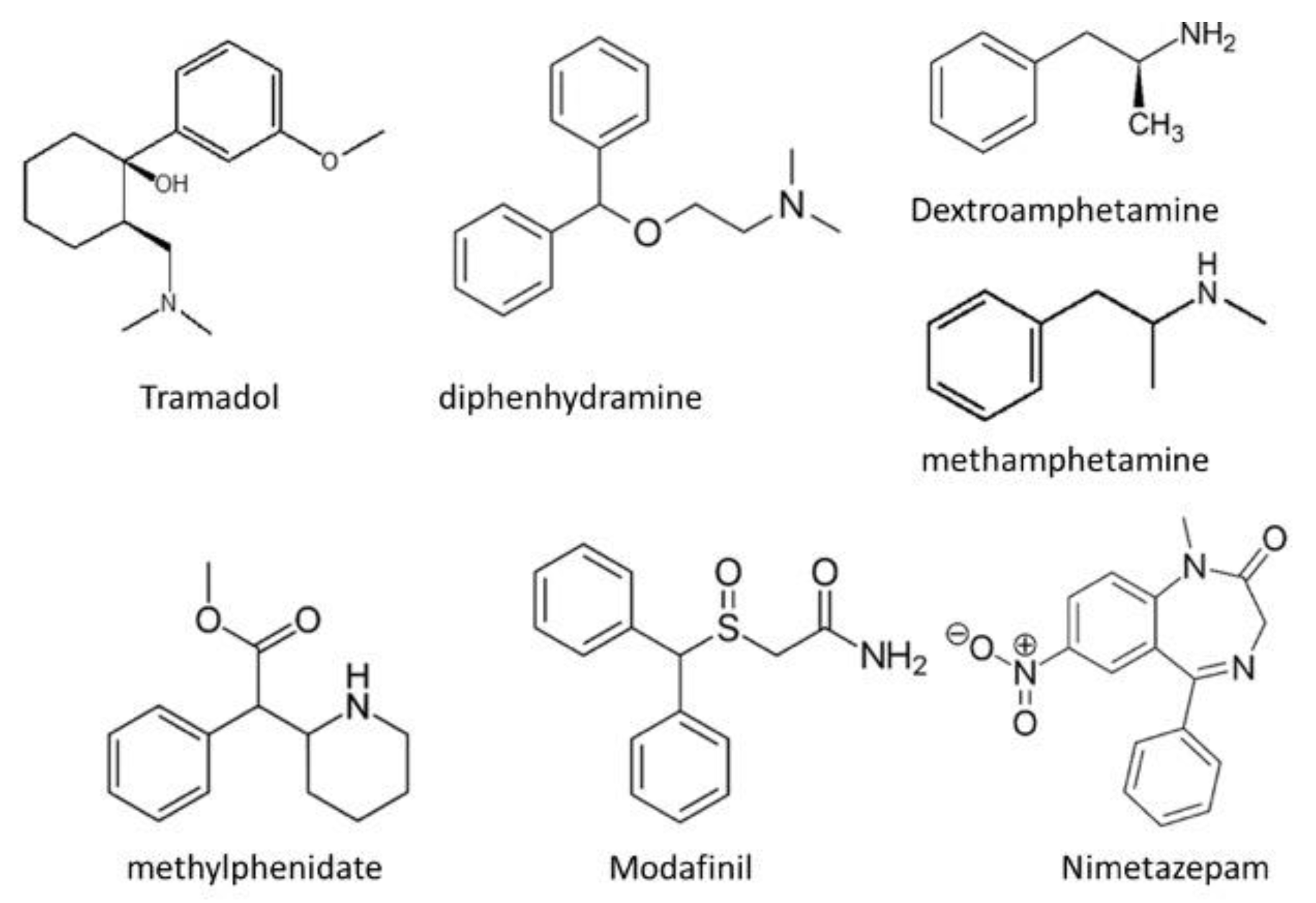

| Tramadol, caffeine, diphenhydramine, codeine, and promethazine | “Lean Cocktail” An improvised drink containing prescription drugs. | None. | Beverage filtered and diluted five times in methanol and introduced to the GC. | GC-FID. DB-5 capillary analytical column (30 m x 0.25 mm i.d. x 0.25 µm film thickness. | LOD 1.25 for tramadol and codeine and 2.5 for caffeine, diphenhydramine, and promethazine. LOQ 2.5 for tramadol and 5.0 for the other analytes. | “Dilute and shoot” method employed. | [59] |

| Dextroamphetamine, methamphetamine, methylphenidate, and modafinil. | Cappuccino, espresso, Nescafe coffee, energy drinks, ginseng drinks. | None. | GO@ZIF-8 MOF MIP SPME | GC-MS in the SIM mode. Column 25 m × 0.32 mm film thickness of 0.5 μm. | LOD between s0.000023 and 0.000033 | Breakfast cereal, dark chocolate, gummi candies, truffles, marshmallows and toffee also investigated. | [60] |

| ketamine, nimetazepam, and xylazine | Mineral water, carbonated drink, tea, beer, and orange juice | None. | Optimised VADLLME procedure | 5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane (HP-5) capillary column (30 m × 0.32 μm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). | LOD, nimetazepam 0.16; ketamine and xylazine, 0.08. LOQ ranged from 0.26 to 0.53. | Internal standard 2,2,2-triphenylacetophenone. | [61] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,4-BD | 1,4-butanediol |

| BSA | N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide |

| BSTFA | N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide |

| CAF | Caffeine |

| COD | Codeine |

| CPSE | Cellulose paper sportive extraction |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DLLME | Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction |

| DPH | Diphenhydramine |

| ECD | Electron capture detector |

| EI | Electron ionization |

| EIC | Ion extracted chromatogram |

| FID | Flame ionization |

| FPD | Flame photometric detector |

| FPSE | Fabric phase sorptive extraction |

| GBL | Gamma-butyrolactone |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| GC-FID | Gas chromatography flame ionization detector |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography mass spectrometry |

| GC-MS/MS DFSA |

Gas chromatograph tandem mass spectrometry. Drug-facilitated sexual assault |

| GC×GC | Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography |

| GHB | Gamma-hydroxybutyrate |

| GHV | Gamma-hydroxyvalerate |

| GO@ZIG-8 MOF | Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

| LLE | Liquid-liquid extraction |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantitation |

| MIP | Molecular imprinted polymers |

| MOF | Metal-organic framework |

| MRM | Multiple reaction monitoring |

| MSTFA | N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide |

| PRO | Promethazine |

| SIM | Selected ion monitoring |

| SPE | Solid phase extraction |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| TMCS | Trimethylchlorosilane |

| TMS | Trimethylsilyl |

| TMSCI | Trimethylsilyl chloride |

| TRA | Tramadol |

| TV-SPME | Total vaporization solid-phase microextraction |

| VADLLME-GC | Vortex-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction-gas chromatography |

References

- Forsberg, C.; Gray, C. Girls Just Want to be Safe: An Analysis of Drugged Drinking and Prevention Amongst Students at the University of South Carolina. Senior Theses 2023, 640. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/640 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Swan, S.C.; Lasky, N.V.; Fisher, B.S.; Woodbrown, V.D.; Bonsu, J.E.; Schramm, A.T.; Warren, P.R.; Coker, A.L.; Williams, C.M. Just a Dare or Unaware? Outcomes and Motives of Drugging (“Drink Spiking”) Among Students at Three College Campuses. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 253-264. [CrossRef]

- House of Commons Home Affairs Committee. Spiking Ninth Report of Session 2021–22; Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 April 2022. Available online: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/21969/documents/165662/default/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Offences against the Person Act 1861. Chapter 100. Legislation.gov.uk. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/100/section/23 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Criminal Justice Act 1988. Chapter 33. Legislation.gov.uk. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/33/section/39 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Sexual Assaults Act 2003. Chapter 42. Legislation.gov.uk. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/section/61/notes#:~:text=The%20offence%20applies%20both%20where,into%20B's%20drink%20than%20A (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Germain, M.; Desharnais, B.; Motard, J.; Doyon, A.; Bouchard, C.; Marcoux, T.; Audette, E.; Muehlethaler, C.; Mireault, P. On-site drug detection coasters: an inadequate tool to screen for GHB and ketamine in beverages. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 352, 111817. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, G.M.; Milić, L.; Endro, A.A.; Simić, M.; Nikolić, I.; Savić, M.; Savić, S. Textile-based wearable device for detection of date rape drugs in drinks. Text. Res. J. 2024, 94, 763–776. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Guidelines for the Forensic Analysis of Drugs Facilitating Sexual Assault and Other Criminal Acts. United Nations. Available online: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/scientists/guidelines-for-the-forensic-analysis-of-drugs-facilitating-sexual-assault-and-other-criminal-acts_new.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Brettell, T.A.; Lum, B.J. Analysis of drugs of abuse by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Analysis of Drugs of Abuse 2018, pp. 29–42.

- Costa, Y.R.S.; Lavorato, S.N.; Baldin, J.J.C.M.C. Violence against women and drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA): A review of the main drugs. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2020, 74, 102020. [CrossRef]

- Burrell, A.; Woodhams, J.; Gregory, P.; Robinson, E. Spiking Prevalence and Motivation. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Amy-Burrell/publication/373895390_Spiking_Prevalence_and_Motivation/links/6501dadd9763a22fa3df74e0/Spiking-Prevalence-and-Motivation.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Scott-Ham, M.; Burton, F.C. Toxicological findings in cases of alleged drug-facilitated sexual assault in the United Kingdom over a 3-year period. J. Clin. Forensic Med. 2005, 12, 175–186. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, C.G.; Jorge, O.Q.; Landeira, A.C. Alleged drug-facilitated sexual assault in a Spanish population sample. Forensic Chem. 2017, 4, 61-66. [CrossRef]

- Orts, M.P.; van Asten, A.; Kohler, I. The Evolution Toward Designer Benzodiazepines in Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Cases. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2023, 47, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Gharedaghi, F.; Hassanian-Moghaddam, H.; Akhgari, M.; Zamani, N.; Taghadosinejad, F. Drug-Facilitated Crime Caused by Drinks or Foods. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 8, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hyver, K.J.; Sandra, P. High Resolution Gas Chromatography, 1989, 3rd edition, Hewlett Packard, 3-28 – 3 29.

- Stafford, D.T.; Brettell, T.A. Forensic Gas Chromatography; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780203016411/0203016416.

- Phillips, D.J.; Caparella, M.; El Fallah, Z.; Neue, U.D. Small particle columns for faster high performance liquid chromatography. Waters Column 1996, 6, 1–7. Available online: https://www.waters.com/webassets/cms/library/docs/wc6-2-1.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Pellizzari, E.D. Electron capture detection in gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1974, 98, 323–361. [CrossRef]

- Burgett, C.A.; Smith, D.H.; Bente, H.B. The nitrogen-phosphorus detector and its applications in gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1977, 134, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Hyver, K.J.; Sandra, P. High Resolution Gas Chromatography; 3rd ed.; Hewlett Packard: 1989; pp. 48–416.

- Snow, N. Flying High with Sensitivity and Selectivity: GC–MS to GC–MS/MS. LCGC North America 2021, 39, 61-67.

- de Hoffmann, E. Tandem mass spectrometry: a primer. J. Mass Spectrom. 1996, 31, 129-137.

- Harvey, D.J.; Vouros, P. Mass spectrometric fragmentation of trimethylsilyl and related alkylsilyl derivatives. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2020, 39(1-2), 105–211. [CrossRef]

- Rontani, J.-F.; Aubert, C. Unexpected peaks in electron ionisation mass spectra of trimethylsilyl derivatives resulting from the presence of trace amounts of water and oxygen in GC-QTOF systems. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 33, 741–743.

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Nouri, N.; Khorram, P. Derivatization and microextraction methods for determination of organic compounds by gas chromatography. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 55, 14-23. [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, P.; Śliwińska, M.; Dymerski, T.; Wardencki, W.; Namieśnik, J. Application of Gas Chromatography to Analysis of Spirit-Based Alcoholic Beverages. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2015, 45, 201–225. [CrossRef]

- Musshoff, F., Chromatographic methods for the determination of markers of chronic and acute alcohol consumption, J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 2002, 781, 457-480. [CrossRef]

- Cerioni, A.; Mietti, G.; Cippitelli, M.; Ricchezze, G.; Buratti, E.; Froldi, R.; Cingolani, M.; Scendoni, R. Validation of a Headspace Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detection Method to Quantify Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) for Forensic Practice. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 133. [CrossRef]

- Ndikumana, E.; Niyonizera, E.; Kabera, J.N.; Pandey, A. Analysis of Methanol and Ethanol Content in Illegal Alcoholic Beverages using Headspace Gas Chromatography: Case Studies at Rwanda Forensic Institute. Braz. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 11, 18–33. [CrossRef]

- Dufayet, L.; Bargel, S.; Bonnet, A.; Boukerma, A.K.; Chevallier, C.; Evrard, M.; Guillotin, S.; Loeuillet, E.; Paradis, C.; Pouget, A.M.; Reynoard, J.; Vaucel, J.-A. Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB), 1,4-Butanediol (1,4BD), and Gamma-Butyrolactone (GBL) Intoxication: A State-of-the-Art Review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 142, 105435. [CrossRef]

- The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order. 2009. Available online: http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2009/draft/ukdsi_9780111486610_en_1 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Savino, J.O.; Turvey, B.E. Rape Investigation Handbook; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2011; p. 335.

- Mason, P.E.; Kerns, W.P. II. Gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) intoxication. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2002, 9, 730–739.

- Weng, T.-I.; Chen, L.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chen, G.-y.; Mou, C.-W.; Chao, Y.-L.; Fang, C.-C. Characteristics of patients with analytically confirmed γ-hydroxybutyric acid/γ-butyrolactone (GHB/GBL)-related emergency department visits in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 1914–1920. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Gamma-butyrolactone (GBL): Critical Review Report, Agenda item 4.3. Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, World Health Organisation, 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/4_3_Review.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- Ciolino, L.A.; Mesmer, M.Z.; Satzger, R.D.; Machal, A.C.; McCauley, H.A.; Mohrhaus, A.S. The chemical interconversion of GHB and GBL: Forensic issues and implications. J. Forensic Sci. 2001, 46, 1315–1323. [CrossRef]

- UK Home Office, Circular 004/2022: Gamma-Butyrolactone (GBL) and 1,4-Butanediol (1,4-BD): revocation of rescheduling. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/circular-0042022-gamma-butyrolactone-gbl-and-14-butanediol-14-bd-revocation-of-rescheduling/circular-0042022-gamma-butyrolactone-gbl-and-14-butanediol-14-bd-revocation-of-rescheduling Accessed 29/12/2024.

- Home Office. Harsher sentences introduced for ‘spiking’ drugs. 13 April 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/harsher-sentences-introduced-for-spiking-drugs (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Tucci, M.; Stocchero, G.; Pertile, R.; Favretto, D. Detection of GHB at low levels in non-spiked beverages using solid phase extraction and gas chromatography—mass spectrometry. Toxicol. Anal. Clin. 2017, 29, 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.P.; Fais, P. Further Evidence for GHB Naturally Occurring in Common Non-Alcoholic Beverages. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017, 277, e36–e38. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Burgess, V. The presence of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 151, 289–292. [CrossRef]

- Meyers, J.; Almirall, J. Analysis of Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid (GHB) in Spiked Water and Beverage Samples Using Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) on Fiber Derivatization/Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS). J. Forensic Sci. 2005, 50, 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Diekman, J.; Thomson, J.B.; Djerassi, C. Mass spectrometry in structural and stereochemical problems. CLV. Electron impact induced fragmentations and rearrangements of some trimethylsilyl ethers of aliphatic glycols, and related compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 2271-2284. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.E.; Hickey, L.D.; Goodpaster, J.V. Detection of ɣ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and ɣ-butyrolactone (GBL) in alcoholic beverages via total vaporization solid-phase microextraction (TV-SPME) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 846–853.

- Meng, L.; Chen, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, J.; Mei, Y.; Cao, J.; Zheng, K. Application of dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction and GC–MS/MS for the determination of GHB in beverages and hair. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 2020, 1144, 122058. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.W.; Oldfield, L.S.; Hoffman, K.N.; Shakleya, D.M.; Bell, S.C. Comparative Analysis of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate and Gamma-Hydroxyvalerate Using GC/MS and HPLC. J. Forensic Sci. 2007, 52, 383–388. [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.P.; Chen, W.; Wu, H.; Mehta, A.K.; Hernandez, R.J.; Ticku, M.K.; Coop, A.; Koek, W.; France, C.P. Comparison of the Behavioral Effects of Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid (GHB) and Its 4-Methyl-Substituted Analog, Gamma-Hydroxyvaleric Acid (GHV). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005, 78, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, N.S.M.; Teoh, W.K.; Saisahas, K.; Phoncai, A.; Kunalan, V.; Muslim, N.Z.M.; Limbut, W.; Chang, K.H.; Abdullah, A.F.L. Determination of Residual Xylazine by Gas Chromatography in Drug-Spiked Beverages for Forensic Investigation. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2022, 26, 774–787.

- Famiglini, G.; Capriotti, F.; Palma, P.; Termopoli, V.; Cappiello, A. The Rapid Measurement of Benzodiazepines in a Milk-Based Alcoholic Beverage Using QuEChERS Extraction and GC–MS Analysis. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2015, 39, 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Acikkol, M.; Mercan, S.; Karadayi, S. Simultaneous determination of benzodiazepines and ketamine from alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages by GC-MS in drug facilitated crimes. Chromatographia 2009, 70, 1295-1298.

- Gautam, L.; Sharratt, S.D.; Cole, M.D. Drug facilitated sexual assault: detection and stability of benzodiazepines in spiked drinks using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89031. [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, M.; Yamini, Y.; Ebrahimpour, B. SPE coupled with dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction followed by GC with flame ionization detection for the determination of ultra-trace amounts of benzodiazepines. J. Sep. Sci. 2014, 37, 287-294. [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.; Jain, R.; Kabir, A.; Zughaibi, T.; Bajaj, A.; Sharma, S. Exploiting the potential of fabric phase sorptive extraction for forensic food safety: Analysis of food samples in cases of drug facilitated crimes. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137191. [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.; Jain, R.; Kabir, A.; Ghosh, A.; Zughaibi, T.; Chauhan, V.; Koundal, S.; Sharma, S. Cellulose Paper Sorptive Extraction (CPSE) Combined with Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) for Facile Determination of Lorazepam Residues in Food Samples Involved in Drug Facilitated Crimes. Separations 2023, 10, 281. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, W.; Teske, J.; Klintschar, M.; Dziadosz, M. Detection of Pharmaceuticals in “Dirty Sprite” Using Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Drug Test. Anal. 2022, 14, 539-544. [CrossRef]

- Meatherall R. GC-MS quantitation of codeine, morphine, 6-acetylmorphine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, and oxymorphone in blood. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2005, 29, 301-308. [CrossRef]

- Phonchai, A.; Pinsrithong, S.; Janchawee, B.; Prutipanlai, S.; Botpiboon, O.; Keawpradub, N. Simultaneous Determination of Abused Prescription Drugs by Simple Dilute-and-Shoot Gas Chromatography – Flame Ionization Detection (GC-FID). Anal. Lett. 2021, 54, 716-728. [CrossRef]

- Kardani, F.; Khezeli, T.; Rashedinia, M.; Hashemi, M.; Zarei Jelyani, A.; Shariati, S.; Mahdavinia, M.; Noori, S.M.A. Application of GO@ZIF-8 MOF/molecularly imprinted polymer composite for multiple monolithic fiber solid phase microextraction: Determination of illegally added amphetamines in snacks and beverages and quantitation by GC-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106977. [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W.K.; Mohamed Sadiq, N.S.; Saisahas, K.; Phoncai, A.; Kunalan, V.; Md Muslim, N.Z.; Limbut, W.; Chang, K.H.; Abdullah, A.F.L. Vortex-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction-Gas Chromatography (VADLLME-GC) Determination of Residual Ketamine, Nimetazepam, and Xylazine from Drug-Spiked Beverages Appearing in Liquid, Droplet, and Dry Forms. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67, 1836–1845.

- Chen, J.; Kuang, Y.; Feng, X.; Mao, C.; Zheng, J.; Ouyang, G. Solid Phase Microextraction Coupled with Portable Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for On-Site Analysis. Green Anal. Chem. 2024, 11, 100164. [CrossRef]

- Mondello, L.; Cordero, C.; Janssen, H.-G.; Synovec, R.E.; Zoccali, M.; Tranchida, P.Q. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2025, 5, 7.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).