Plain Language Summary

Plain Language Title

Identifying and Treating High Levels of Cortisol Activity in Patients Who Have Diabetes: A Case Series

Plain Language Summary

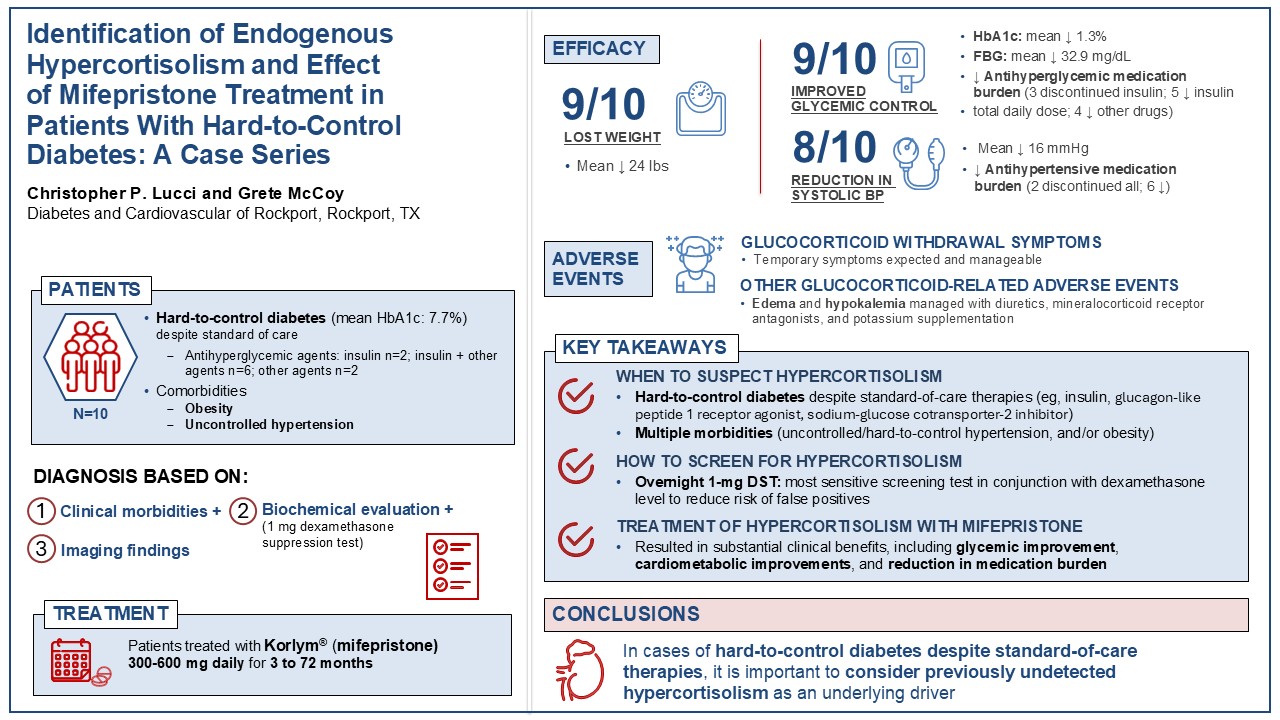

Some patients with diabetes struggle to control their blood sugar levels, even when they follow their doctor’s advice and take the prescribed medications. When diabetes is hard to manage, it can also make it more difficult to keep blood pressure under control. This can lead to serious problems like heart attacks and strokes. Some researchers believe that having too much cortisol in the body, which is called hypercortisolism, might be why it is harder for some patients to control their diabetes.

In this paper, we discuss 10 patients with diabetes from our medical practice who had trouble achieving recommended blood sugar goals. We suspected that high cortisol might be the reason because of other health problems the patients had, such as obesity and high blood pressure.

We used a simple blood test to measure the cortisol levels in our patients. All 10 patients were diagnosed with hypercortisolism and given a medication called mifepristone, which reduces the effects of cortisol. After starting the medication, 9 patients lost weight and 9 patients also had improved blood sugar levels. Eight patients were able to stop taking insulin or take less of it. Blood pressure improved in 8 patients, including 6 who required fewer blood pressure medications and 2 who stopped taking blood pressure medications completely.

Some patients had mild and expected side effects from mifepristone, such as fatigue, nausea, or headaches. However, we were able to help them by adjusting how much mifepristone they took or by managing their symptoms.

It is important for doctors to check if cortisol may be the cause of their patients’ poorly controlled diabetes. Treating these patients with mifepristone may help them better manage their diabetes and improve their long-term health.

1. Introduction

Endogenous hypercortisolism (Cushing syndrome) is a multisystemic, heterogeneous disease caused by prolonged exposure to excess cortisol. [

1,

2] Classical overt features typically associated with hypercortisolism include easy bruising, purple striae, and facial plethora. However, patients with hypercortisolism may not exhibit these physical features, requiring diagnosis stimulated by clinical suspicion.[

3] Hypercortisolism affects all organ systems, resulting in a spectrum of morbidities that include diabetes, hypertension, abnormal blood clotting, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidities, metabolic disorders, osteopenia and osteoporosis, neuropsychiatric disorders, and sexual dysfunction.[

4] Patients with hypercortisolism have an approximately 3-fold elevated risk of mortality compared with the general population.[

5]

Diabetes is a frequent complication of hypercortisolism. Abnormalities of glucose metabolism occur in ~50% of patients with hypercortisolism and contribute to excess morbidity and mortality.[

6] Cortisol excess can be an underlying driver of diabetes, with direct and indirect effects on glucose metabolism resulting in insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. The prevalence of hypercortisolism in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is significant and has been reported in approximately 5%-10% of patients,[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] with an up to 3.5 times higher prevalence in patients with advanced T2D taking multiple medical therapies, insulin, or concomitant antihypertensive medications.[

12] CATALYST (NCT05772169) is a prospective, multicenter, US-based study to assess the prevalence of hypercortisolism in approximately 1000 patients with difficult-to-control T2D, defined as HbA1c 7.5%-11.5% despite multiple therapies.[

13] Preliminary findings presented at the 84th American Diabetes Association (ADA) Scientific Sessions (June 24, 2024) indicated that the prevalence of hypercortisolism in the CATALYST population was 24% (253/1055).[

14] In addition, the likelihood of hypercortisolism was approximately two times higher in the CATALYST patients who had ≥2 anti-hyperglycemic and ≥2 anti-hypertensive medications (odds ratio: 1.871 [95% CI: 1.406, 2.491]).[

14]

Due to the diverse multisystemic presentation and nonspecific nature of many of the symptoms, patients with hypercortisolism may go undiagnosed for many years, resulting in significant unmet needs and burden of illness.[

15] An understanding of hypercortisolism and its clinical presentation is therefore crucial for early diagnosis and timely treatment to improve patient outcomes. Given the prevalence of T2D, it is neither practical nor recommended to perform mass screening for hypercortisolism. Screening an enriched population with a high pretest probability of hypercortisolism, however, may be warranted. Based on the CATALYST prevalence data, the enriched population includes patients with difficult-to-control T2D despite multiple antihyperglycemic and antihypertensive medications.[

14]

Specific guidance for hypercortisolism screening and treatment among patients with diabetes is lacking. In this case series, we present 10 patients with hard-to-control diabetes, despite aggressive standard-of-care combination therapies. We discuss the clinical characteristics of hypercortisolism in these patients. Finally, we present clinical outcomes following the treatment with mifepristone (Korlym

®, Corcept Therapeutics), a competitive glucocorticoid receptor antagonist indicated to control hyperglycemia secondary to hypercortisolism in adult patients with endogenous Cushing syndrome who have glucose intolerance/T2D and have failed surgery or are not candidates for surgery.[

16] Treatment outcomes included weight loss, improved blood pressure (BP) and glycemic control, and reduction in antidiabetic and antihypertensive medication burden. This case series provides information that may assist clinicians in understanding when to suspect hypercortisolism as an underlying condition in their patients who struggle with the hard-to-control diabetes.

2. Case Series Description

Patients

Patients in this case series had hard-to-control diabetes (type 1 diabetes [T1D] or T2D) with multiple comorbidities despite receiving standard-of-care treatment. Because of the difficulties in managing these patients’ dysglycemia, clinical suspicion was high for hypercortisolism, and they were screened for cortisol excess. Consent to treat and publish was obtained from each patient or the patient’s representative. Approval from an Institutional Review Board or ethics committee was not required as this was a retrospective case series from a single clinical practice site.

2.1. Screening and Diagnosis of Hypercortisolism

Hypercortisolism was diagnosed based on the patient’s clinical findings (physical exam and comorbidities), biochemical evaluations, and imaging. The 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) with a serum cortisol threshold of 1.8 µg/dL was used as the screening test for hypercortisolism because of its high sensitivity.[

17,

18] To avoid false-positive results, patients with recent exposure to exogenous steroids (within 2 months of DST) were excluded. Measurement of serum dexamethasone with a cutoff of 140 ng/dL was frequently used alongside the DST to ensure adequate cortisol suppression.[

19] Additional supportive assessments included morning plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) levels and imaging to localize the source. Because there are no guidelines for specific ACTH and DHEA-S levels for patients with adrenal adenomas, low to low-normal ACTH and DHEA-S levels were used to exclude a pituitary or ectopic source of hypercortisolism. Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed for patients with an ACTH level >5 pg/mL.[

20,

21] Confirmation of adrenal etiology was obtained by abdominal computed tomography (CT) using an adrenal protocol.[

18]

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Baseline data were collected at the last clinic visit prior to the start of mifepristone and included patient demographics and characteristics, laboratory findings, imaging results, and medication history. The details of mifepristone treatment, including duration and dosage, as well as changes in patients’ weight, glycemic control, and blood pressure during treatment were recorded. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was used to assess the percentage of time in range (CGM-TIR; glucose 70-180 mg/dL) and change in the mean amplitude of glycemic excursions. Medication burden was assessed as the total daily dose (TDD) of insulin and as the number of other antiglycemic and antihypertensive medications. For antiglycemic and antihypertensive combination therapies, each medication was counted separately. Renal functions were carefully monitored with regular assessments of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR),[

22] serum creatinine, and urinary albumin. The occurrence of adverse events, including glucocorticoid withdrawal symptoms (GWS),[

23] were also documented.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics – Hard-to-Control Diabetes, Obesity, and Uncontrolled Hypertension

Ten patients (5 women, 5 men) with a mean age of 67.6 (range 46-76) years were included in this case series (

Table 1). Among the 10 patients, 1 was overweight (body mass index [BMI] 28 kg/m

2, 5 were obese (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m

2) and 4 were extremely obese (BMI >35 kg/m

2). Two patients had clinical signs of hypercortisolism (eg, moon facies, rapid weight gain). At baseline, all patients had impaired glucose control with either T1D (2/10 patients) or T2D (8/10 patients). The patients had poor glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) control (mean 7.7%) and elevated fasting blood glucose (mean 155.5 mg/dL), despite the use of antihyperglycemic medications in all 10 patients: insulin alone (2/10), insulin with additional antihyperglycemic medications (6/10), or antihyperglycemic medications without insulin (2/10). CGM-TIR data prior to the start of mifepristone were available for 7 patients, with CGM-TIR values ranging from 36%-79%. All patients were hypertensive at baseline (mean systolic BP of 138.3 mmHg) despite ongoing treatments with up to 5 antihypertensive medications At baseline, mean eGFR and serum creatinine were 65.9 mL/min (range 36-104 mL/min) and 1.12 mg/dL (range 0.5-2.01 mg/dL), respectively. An eGFR of <60 mL/min was observed in 6 patients and a serum creatinine >1.4 mg/dL was seen in 3 patients, indicating various degrees of renal impairment.

Data are shown as mean (min, max) unless otherwise noted. aData available for 7 patients. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CGM-TIR, continuous glucose monitoring time-in-range; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Diagnosis of Hypercortisolism – Comorbidity Considerations, Biochemical Evaluation, Imaging

Due to the clinical suspicion based on the patients’ multiple comorbidities (hard-to-control diabetes, hypertension, obesity) despite standard-of-care therapies, patients were screened for hypercortisolism using the 1-mg overnight DST. Hypercortisolism, biochemically defined by post-DST cortisol ≥1.8 µg/dL was found in 9/10 patients (

Table 2). Details of one patient (Patient 4) who had post-DST cortisol of 1.2 µg/dL with clinical suspicion of hypercortisolism (longstanding [10+ years] uncontrolled T2D and uncontrolled hypertension under extensive medications, weight gain, obesity) are presented in the

Patient details section below. Additional measurements of plasma ACTH (mean 7.6 pg/mL) and serum DHEA-S (mean 46.9 µg/dL) were performed to assess the source of hypercortisolism. Pituitary MRI was performed in patients who had an ACTH level >5 pg/mL and was negative for all 5 patients who had the imaging performed. Adrenal CT imaging confirmed the presence of adrenal adenomas in 4/10 patients. All 4 patients had an appropriate surgical consultation. After consultation, 2 patients elected to undergo surgery. One received mifepristone preoperatively as a bridge treatment. The other was not deemed to be a good surgical candidate due to elevated cardiometabolic risk and was started on mifepristone to improve their surgical candidacy. The 2 other patients declined surgery and opted for medication treatment.

3.2. Treatment Response with Mifepristone

With the diagnosis based on comorbidities, biochemical evaluation, and imaging, hypercortisolism was treated in all patients with mifepristone. Patients were initiated on mifepristone 300 mg daily, with a titration of 300-mg increments after 1 month as needed. From baseline to the final follow-up of mifepristone treatment (duration ranging from less than 3 months to 72 months), patients experienced significant clinical improvements, such as weight loss, better glycemic control, improved BP control, and a reduction in medication usage (

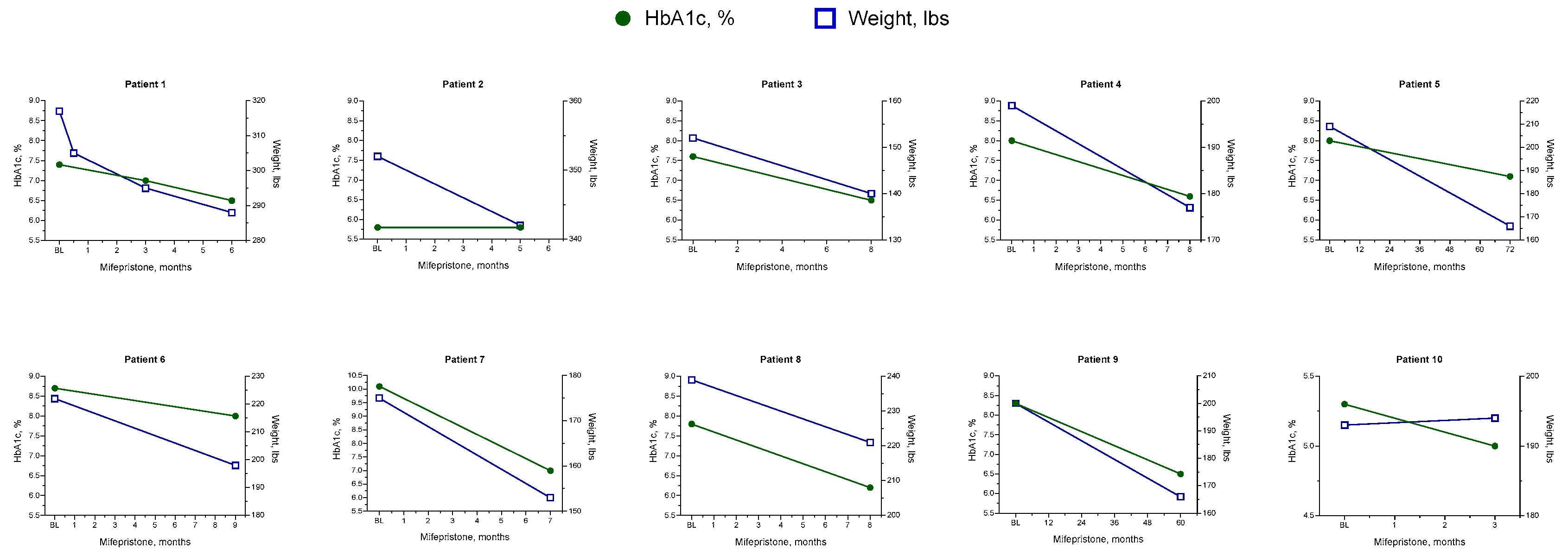

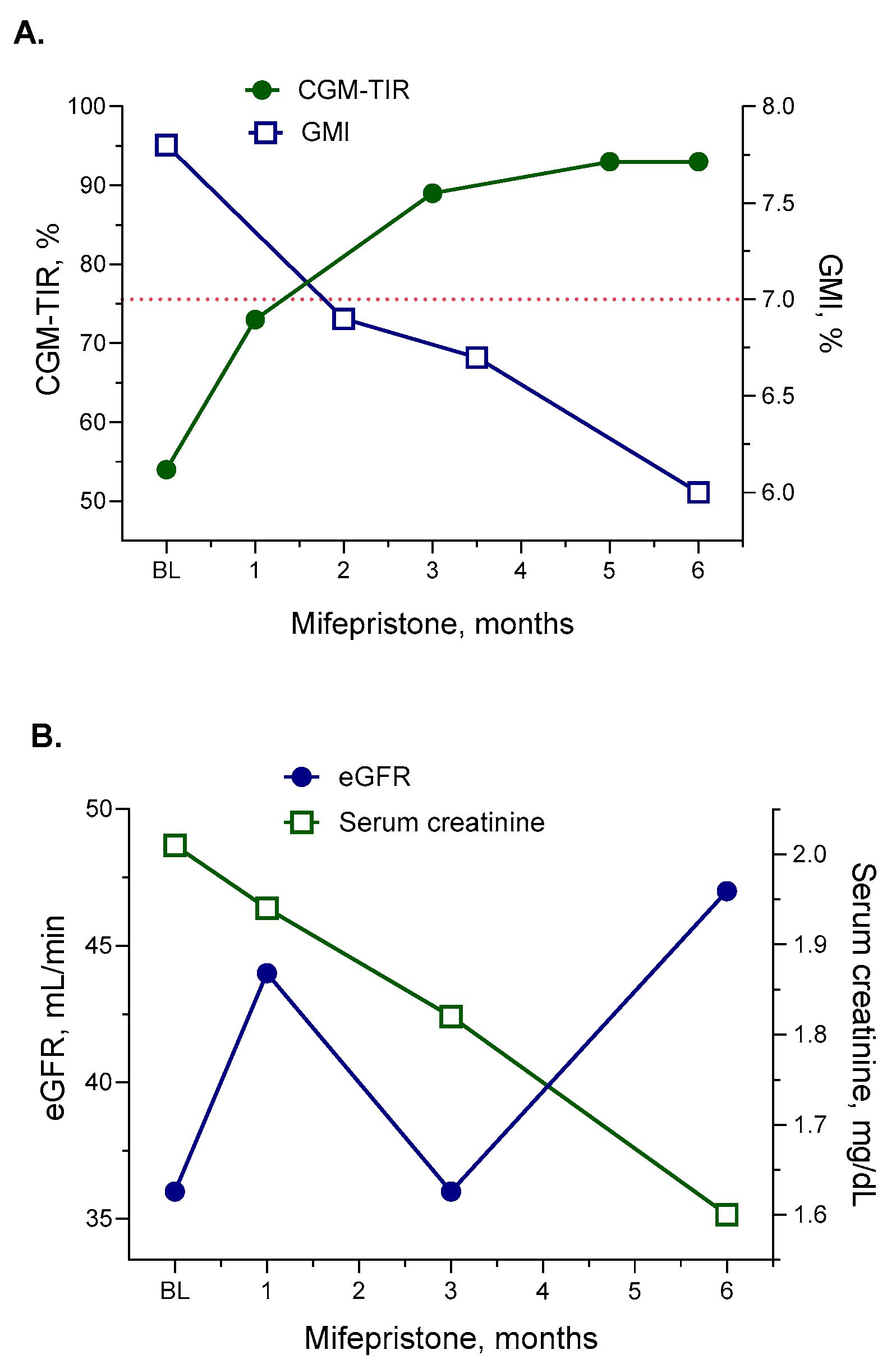

Table 3). Nine patients lost weight, with an average weight loss of 24 lbs (range: 10-43 lbs). Improvements in HbA1c and fasting blood glucose (FBG) were also seen in 9 patients, with a mean reduction of 1.3% (range: 0.3%-3.1%) in HbA1c and a mean reduction of 32.9 mg/dL (3.1-99 mg/dL) in FBG. All 7 patients who wore continuous glucose monitors had improved CGM-TIR, with a mean increase of 19.4% (range: 7%-43%). In addition, improvements in glycemic control were achieved with a reduction in antihyperglycemic medications (

Table 4). At their last follow-up while on mifepristone, 3 of the 8 patients who were taking insulin at baseline had completely discontinued insulin therapy. For the 5 patients who continued to take insulin, all had decreased their insulin TDD. Two patients, both with T1D and insulin resistance, decreased their insulin TDD and stopped using continuous insulin pumps. No patients added insulin or increased their insulin TDD after starting on mifepristone, and 4 patients decreased the number of their other antidiabetic medications (

Table 4).

All patients had hypertension at baseline, and at the end of mifepristone treatment systolic BP was reduced in 8 patients (mean reduction: 16 mmHg [range: 2-36 mmHg]) (

Table 3). Antihypertensive medications were reduced in 8 patients; 6 patients required fewer medications, and 2 patients discontinued all antihypertensive medications entirely (

Table 4).

At the last follow-up on mifepristone, eGFR had increased in 7 patients by an average of 17.4 mL/min (range: 1-33 mL/min). Serum creatine had decreased in 7 patients, by an average of 0.23 mg/dL (range 0.06-0.51 mg/dL) (

Table 3). eGFR decreased in 3 patients (mean decrease 22 mL/min) who had baseline eGFR of 89-104 mL/min, which may indicate normalization of mild hyperfiltration. One patient was diagnosed with gross proteinuria after starting mifepristone despite also having increased eGFR and decreased creatinine levels.

Three patients eventually underwent adrenalectomy. Two patients received mifepristone for 3 and 7 months, respectively, and then underwent adrenalectomy. One patient with a CT-confirmed adrenal source of cortisol excess was referred for additional testing and was diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma. Mifepristone was discontinued and the patient underwent surgery.

3.3. Glucocorticoid Withdrawal Syndrome

Patients with hypercortisolism may experience signs and symptoms of GWS (ie, nausea, fatigue, headache) after treatment with a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, especially during the first 3 months (“cortisol withdrawal phase”).[

23] In this case series, 8 patients reported temporary and manageable symptoms of GWS. The patients continued to receive mifepristone and were provided medication for symptom management as necessary. In all 8 patients, GWS had resolved or was resolving at the time of their last follow-up. All patients with GWS also experienced BP variability requiring multiple medication adjustments. However, once GWS had resolved, all patients demonstrated improved BP control (

Table 2). No patients had primary adrenal insufficiency during mifepristone treatment. Edema and hypokalemia were seen in 8 patients each. All patients received treatment with diuretics and potassium supplementation as needed. One patient required hospitalization for hypokalemia after 3 months of treatment. This patient reported muscle cramps and nausea and was found to have a potassium value of 2.8 mmol/L. She received potassium supplementation in the hospital and her symptoms resolved. She discontinued mifepristone bridge therapy and underwent adrenalectomy approximately 1 month later.

4. Patient Details

Patient 1

Patient 1 was a 67-year-old man with uncontrolled T2D characterized by hyperglycemia and hypertension despite aggressive treatment, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and a history of deep vein thromboses. The patient was receiving treatment with several medications, including antihyperglycemic medications (insulin, empagliflozin, glipizide, metformin, semaglutide), antihypertensive medications (metoprolol succinate, valsartan plus hydrochlorothiazide), and lipid-lowering medication (atorvastatin). Despite receiving treatment with semaglutide, a highly effective GLP-1 receptor agonist (RA), this patient had very little weight loss and failed to meet his glycemic goal. At baseline, the patient’s weight and BMI were 317 lbs and 49.6 kg/m

2, respectively, and his HbA1c and glucose monitoring index (GMI) were 7.4% and 7.8%, respectively (

Figure 2A). At baseline, CGM over 16 days showed a CGM-TIR (glucose 70-180 mg/dL) of 54%, time over range (glucose >180 to ≤250 mg/dL) of 38%, and time in severe hyperglycemia (glucose >250 mg/dL) of 8%. The patient’s average (SD) glucose level was 187 (38) mg/dL, with considerable variability during waking hours. Renal function at baseline showed evidence of impairment, with an eGFR of 36 mL/min (

Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Changes in HbA1c and weight with mifepristone plus standard-of-care treatment.

Figure 1.

Changes in HbA1c and weight with mifepristone plus standard-of-care treatment.

Hypercortisolism was confirmed in this patient with a post-DST serum cortisol level of 1.8 µg/dL with an adequate dexamethasone level of 420 ng/dL. His ACTH was 9.4 pg/mL, suggesting an adrenal cortisol source, although CT scanning revealed no adrenal abnormalities.

Patient 1 started mifepristone 300 mg once daily for 4 months, followed by an increase in dosage to 600 mg once daily. The dose was well tolerated, and the patient experienced rapid and sustained improvements in weight, glycemic control, and renal function (

Figure 2). After 1 month of treatment, he lost 12 lbs. His glycemic control improved, with his FBG decreasing by 35 points to 127 mg/dL, and his CGM-TIR improving to 73%. eGFR had increased to 44 mL/min, and serum creatinine had decreased to 1.94 mg/dL. After 6 months of mifepristone treatment, he had lost a total of 29 lbs and his CGM-TIR had further improved to 93%, with considerably improved variability in glucose levels during waking hours (

Figure 2A). Renal function also continued to show signs of improvement with mifepristone plus standard-of-care therapy, with an eGFR and serum creatinine of 47 mL/min and 1.6 mg/dL, respectively, after 6 months of treatment (

Figure 2B). The patient experienced a transient drop in eGFR between 1 and 3 months of mifepristone treatment, possibly attributable to concomitant treatment with empagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor. SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to induce an initial acute dip in eGFR, after which eGFR typically returns toward baseline and stabilizes over time.[

24] This patient did not experience symptoms of GWS during treatment with mifepristone.

Patient 4

Patient 4 was a 68-year-old man with longstanding (>10 years) uncontrolled T2D and hypertension despite intensive treatment with combination therapies. He also had multiple comorbidities, including obesity, CKD, depression, and insomnia. At his initial workup, the patient’s weight and BMI were 203 lbs and 33.0 kg/m2, respectively, and he had an HbA1c of 8%. Baseline CGM showed a TIR of 73%, with high glucose variability and excessive excursions. At the initial visit, he had been receiving intensive treatments with insulin (TDD 40 U/day) for 10 years. In addition, he was also taking empagliflozin, pioglitazone, and tirzepatide for glycemic control, and amlodipine, azilsartan medoxomil plus chlorthalidone, and diltiazem for hypertension. This patient had evidence of renal impairment at baseline with an eGFR of 51 mL/min and a serum creatinine of 1.49 mg/dL.

At screening, the patient had a post-DST serum cortisol of 1.2 µg/dL with adequate dexamethasone level of 759 ng/dL. Abdominal CT was not performed due to the DST result below the 1.8 µg/dL diagnostic cutoff. However, the patient’s uncontrolled T2D and hypertension despite multiple medications strongly suggested hypercortisolism as an underlying cause. Despite the below-threshold DST results and consultation with the patient explaining his eligibility for treatment under current testing conventions, the patient strongly advocated for treatment due to his frustration with his long-term health burdens.

Patient 4 was started on mifepristone 300 mg/day. After 1 month of treatment, the patient was able to decrease his insulin TDD and his dosage of azilsartan and chlorthalidone. Mifepristone was increased to 600 mg/day, after which the patient was able to discontinue insulin for the first time in 10 years. After 8 months of treatment with mifepristone plus standard-of-care treatment, the patient had lost 22 lbs, his HbA1c had decreased by 1.4 points to 6.6%, and his CGM-TIR had increased to 86%. In addition, the patient was able to stop taking empagliflozin and metformin, decrease his dose of pioglitazone, and discontinue amlodipine. Along with other standard-of-care treatments, his renal function showed evidence of improvement, with an increase in eGFR from 51 to 84 mL/min and a decrease in creatinine from 1.49 mg/dL to 0.98 mg/dL.

The patient experienced GWS of fatigue and edema beginning 3-4 weeks after starting mifepristone. He continued to receive mifepristone and had finerenone and potassium supplementation added to his regimen. His symptoms of GWS had resolved at follow-up.

5. Discussion

This case series highlights the importance and clinical benefits of identifying previously undetected hypercortisolism in patients with T1D or T2D. Patient characteristics associated with higher risks of hypercortisolism include hard-to-control diabetes despite standard-of-care therapy and hypertension. Identification of hypercortisolism in patients with T2D is important for effective management of the cardiometabolic complications associated with glucocorticoid excess.[

25,

26,

27]

The estimated US prevalence of diagnosed T2D in 2011-2015 was 9.5% in adults age ≥20 years of age, equivalent to 21.8 million persons, increasing to approximately 20% in adults aged ≥65 years.[

28] Given the high prevalence of T2D, mass screening for hypercortisolism in all diabetic patients is neither feasible nor recommended. It may, however, be possible to identify those patients with T2D who are at higher risk of hypercortisolism. For example, the risk of hypercortisolism is up to 3.6 times higher in patients with advanced T2D, defined as T2D requiring multiple therapies, insulin, or concomitant antihypertensive medications.[

12,

14]

Most (9/10) patients in this case series had a DST result ≥1.8 µg/dL, consistent with their presenting symptoms, including hard-to-control diabetes and hypertension. Hypercortisolism exists along a continuum, with cardiometabolic risks that increase with the duration and severity of hypercortisolism.[

29] Notably, it is important to interpret the post-DST results as a continuous variable, rather than a categorical (yes/no) variable.[

18] As demonstrated in Patient 4’s case details, even moderately elevated cortisol can significantly affect patient health. The treatment course reported for Patient 4 illustrated a real-world individualized and holistic treatment approach using shared decision making. Although assessment of serum cortisol levels after initiation of the cortisol modulator mifepristone is not useful, the global improvements in metabolic and cardiovascular dysfunction seen are consistent with a reduction in cortisol activity and restoration of normal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning.[

30]

Administration of mifepristone 300-600 mg once daily to the patients in this case series resulted in weight loss and improvements in glycemic control and BP. Patients also were able to reduce their overall medication burden, including discontinuation of insulin treatment or decreasing their insulin TDD, with reductions in other antihyperglycemic medication and antihypertensive medications. Strategies for managing cortisol withdrawal symptoms, titration considerations, and hypertension management during mifepristone treatment were discussed. These findings suggest that mifepristone is a valuable therapeutic option for patients with hypercortisolism and hard-to-control diabetes, particularly those with challenging metabolic derangements.

In the CATALYST study, the prevalence of hypercortisolism in patients with difficult-to-control T2D was 24% (253/1055) based on the preliminary findings presented at the 84th ADA Scientific Sessions (June 24, 2024).[

14] This finding indicates that patients with difficult-to-control T2D represent an at-risk population with a high pretest probability of hypercortisolism. Additional research suggests that mifepristone may act as an insulin sensitizer in patients with impaired glucose tolerance. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study found that short-term administration of mifepristone 200 mg/day capsules to 16 patients with impaired glucose tolerance who did not have hypercortisolism as assessed by 24-hour urinary free cortisol (24-hr UFC), was associated with significant improvement in insulin sensitivity at the adipose tissue level.[

31] Of note, many patients with autonomous cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas have normal 24-hr UFC values.[

18]

Several patients in our case series had impaired baseline renal function, a serious comorbidity, which factored in our decision to treat. Based on the eGFR and serum creatinine test results, there appeared to be a trend towards improved renal function. However, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios (UACR) were variable, and one patient had newly diagnosed gross proteinuria, despite increased eGFR and decreased creatinine. Therefore, we cannot make conclusions about improvements in renal function with mifepristone treatment, although we believe the data are of interest and warrant further studies.

6. Clinical Implications

6.1. When to Suspect Hypercortisolism – Distinguishing Clinical Characteristics of Patients with T2D and Hypercortisolism

In patients with advanced T2D, several distinguishing clinical characteristics could indicate the existence of previously undetected hypercortisolism. The absence of the physical features of Cushing syndrome should not be taken as evidence that hypercortisolism is absent. Instead, physicians should be attentive to a constellation of morbidities that can signal hypercortisolism, including an inability to achieve glycemic control with aggressive treatment for insulin resistance and/or with multiple medications. Excess cortisol impacts tissues and organs that antidiabetic medications target. For example, cortisol excess counteracts the production of GLP-1 and the action of GLP-1 on insulin secretion and reduces the efficacy of GLP-1 RA treatment. When a patient’s diabetes is only partially responsive to known effective medications it is important to consider hypercortisolism as a potential underlying driver of T2D that is hard to control, Other factors that should trigger clinical suspicion of hypercortisolism include the presence of uncontrolled or difficult-to-control hypertension, or an inability to lose weight even with GLP-1 RA therapy.

6.2. How to Screen for Hypercortisolism

The 1-mg DST, with adequate dexamethasone levels, is the most sensitive first-line screening test for hypercortisolism.[

17] All well-known causes leading to inaccurate DST results, such as the use of exogenous steroids within 2 months of the DST, should be avoided. Serum dexamethasone levels, measured alongside serum cortisol post-DST, should be above 140 ng/dL to ensure sufficient serum cortisol suppression and therefore reduce the risk of false positives.[

17,

19] With discordant biochemical results, such as a DST result <1.8 µg/dL, careful attention to the patient’s constellation of symptoms and treatment history is crucial.

6.3. Treatment of Hypercortisolism in Patients with T2D

The importance of treating underlying hypercortisolism in patients with hard-to-control diabetes should not be underestimated. Treatment benefits of mifepristone seen in this case series included improvements in body weight/BMI, fasting glucose levels, HbA1c, and BP. Treatment should be initiated with the recommended dose of 300 mg, administered orally once daily. Careful and gradual titration was typically initiated after 1 month of treatment and was based on tolerability and adverse reactions.

6.4. Assessment of Treatment Effectiveness in Glycemic Control

Because mifepristone does not decrease cortisol production, treatment efficacy must be assessed clinically.[

32] In addition to changes in HbA1c, changes in CGM-TIR and glucose excursion should also be considered as assessments of glucose control. CGM is important during insulin down-titration, especially if GLP-1 agonists are introduced or up-titrated at the same time, to avoid hypoglycemia. Reduction in insulin dosage is also an important measure of treatment outcome and as an indicator of reduction in medication burden. Some patients will not completely stop all antidiabetic medications. GLP-1 agonists should be continued given their protective benefit against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).[

33] Similarly, SGLT2 inhibitors should be continued in patients with a diagnosis of proteinuria to help reduce complications of congestive heart failure or CKD.[

34]

6.5. Glucocorticoid Withdrawal Symptoms – What to Expect and How to Manage

Since patients may have had hypercortisolism for some time, treating HCPs should be attentive for GWS. These are analogous to symptoms seen in patients abruptly ceasing exogenous steroid use and are expected in patients treated with a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist. The time window for the development of GWS is approximately 3 months after the initial response to glucocorticoid receptor antagonism, and is relatively consistent. It is important to note that GWS can be managed. Importantly, GWS are temporary and typically resolve as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovers.[

23] Pretreatment consultation with the patient is essential in setting appropriate expectations.

It is also important to consider hypertension management during mifepristone treatment for hypercortisolism. All patients included in this case series had hypertension at baseline, and all had either a reduction in systolic BP and/or had reached their target goal BP with a reduction in the number of antihypertensive medications. It should be noted that patients who experience GWS may also experience BP variability, requiring multiple adjustments to their antihypertensive medications. However, BP typically stabilizes once GWS has resolved.

This case series represents real-world clinical practice. Additional findings from the prospective CATALYST study will help further inform clinicians on how to identify and treat hypercortisolism in patients with hard-to-control diabetes. For many patients with a positive imaging finding, surgery is the first-line treatment approach for hypercortisolism; however, for patients who may not be eligible for surgery or who may not elect to undergo surgery, or in cases where the hypercortisolism source has not yet been determined, medical treatment is a valuable option.

7. Conclusions

Overall, this case series emphasizes the importance of considering hypercortisolism as a differential diagnosis and potential underlying driver in cases of challenging, hard-to-control diabetes. Addressing hypercortisolism with mifepristone resulted in significant clinical benefits, including improvements in cardiometabolic parameters and reductions in medication burden.

Author Contributions

CPL and GM oversaw the clinical care of the patients. CPL was responsible for conceptualization. CPL and GM were responsible for data curation and analysis; contributed to the writing of the article; revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the final version of the manuscript; and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the publication of this article: writing and editorial support for this manuscript was funded by Corcept Therapeutics.

Patient Consent Statement

Written informed consent for the inclusion of patient details was obtained from the 10 patients included in this report. Any potentially identifying patient details have been removed.

Availability of Data and Materials

The laboratory and diagnostic findings for these cases are presented in the tables.

Acknowledgments

Huixuan Liang, PhD (Corcept Therapeutics, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and John Watson, PhD, Sarah Mizne, PharmD, and Don Fallon, ELS (Woven Health Collective, New York, NY, USA) provided medical writing and editorial support, which was funded by Corcept Therapeutics. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ “Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: 2022 Update.”

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: CPL has been a speaker for Corcept Therapeutics and Novo Nordisk; GM has nothing to declare.

References

- Gadelha M, Gatto F, Wildemberg LE, Fleseriu M. Cushing's syndrome. Lancet. 2023;402(10418):2237-2252.

- Reincke M, Fleseriu M. Cushing syndrome: a review. JAMA. 2023;330(2):170-181.

- Favero V, Cremaschi A, Parazzoli C, et al. Pathophysiology of mild hypercortisolism: from the bench to the bedside. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):673.

- Braun LT, Riester A, Osswald-Kopp A, et al. Toward a diagnostic score in Cushing's syndrome. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:766.

- Limumpornpetch P, Morgan AW, Tiganescu A, et al. The effect of endogenous Cushing syndrome on all-cause and cause-specific mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(8):2377-2388.

- Mazziotti G, Gazzaruso C, Giustina A. Diabetes in Cushing syndrome: basic and clinical aspects. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22(12):499-506.

- Catargi B, Rigalleau V, Poussin A, et al. Occult Cushing's syndrome in type-2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5808-5813.

- Chiodini I, Torlontano M, Scillitani A, et al. Association of subclinical hypercortisolism with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in hospitalized patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153(6):837-844.

- Costa DS, Conceicao FL, Leite NC, Ferreira MT, Salles GF, Cardoso CR. Prevalence of subclinical hypercortisolism in type 2 diabetic patients from the Rio de Janeiro Type 2 Diabetes Cohort Study. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30(6):1032-1038.

- León-Justel A, Madrazo-Atutxa A, Alvarez-Rios AI, et al. A probabilistic model for Cushing's syndrome screening in at-risk populations: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(10):3747-3754.

- Steffensen C, Dekkers OM, Lyhne J, et al. Hypercortisolism in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a prospective study of 384 newly diagnosed patients. Horm Metab Res. 2019;51(1):62-68.

- Aresta C, Soranna D, Giovanelli L, et al. When to suspect hidden hypercortisolism in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Endocr Pract. 2021;27(12):1216-1224.

- DeFronzo RA, Auchus RJ, Bancos I, et al. Study protocol for a prospective, multicentre study of hypercortisolism in patients with difficult-to-control type 2 diabetes (CATALYST): prevalence and treatment with mifepristone. BMJ Open. 2024;14(7):e081121.

- Fonseca V. Results of the CATALYST trial part 1 [oral presentation]. Presented at American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions, June 24, 2024, Orlando, FL. 24 June.

- Page-Wilson G, Oak B, Silber A, et al. Evaluating the burden of endogenous Cushing's syndrome using a web-based questionnaire and validated patient-reported outcome measures. Pituitary. 2023;26(4):364-374.

- KORLYM® (mifepristone) 300 mg Tablets [prescribing information]. Menlo Park, CA: Corcept Therapeutics Incorporated; November 2019.

- Sherlock M, Scarsbrook A, Abbas A, et al. Adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(6):775-820.

- Fassnacht M, Tsagarakis S, Terzolo M, et al. European Society of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines on the management of adrenal incidentalomas, in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2023;189(1):G1-G42.

- Farinelli DG, Oliveira KC, Hayashi LF, Kater CE. Overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test for screening Cushing syndrome and mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS): What happens when serum dexamethasone is below cutoff? How frequent is it? Endocr Pract. 2023;29(12):986-993.

- Kirk LF, Jr., Hash RB, Katner HP, Jones T. Cushing's disease: clinical manifestations and diagnostic evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(5):1119-1127, 1133-1134.

- Nieman LK. Molecular derangements and the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(5):852-877.

- Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737-1749.

- He X, Findling JW, Auchus RJ. Glucocorticoid withdrawal syndrome following treatment of endogenous Cushing syndrome. Pituitary. 2022;25(3):393-403.

- Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZ. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation. 2016;134(10):752-772.

- Di Dalmazi G, Vicennati V, Garelli S, et al. Cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with adrenal incidentalomas that are either non-secreting or associated with intermediate phenotype or subclinical Cushing's syndrome: a 15-year retrospective study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(5):396-405.

- Patrova J, Kjellman M, Wahrenberg H, Falhammar H. Increased mortality in patients with adrenal incidentalomas and autonomous cortisol secretion: a 13-year retrospective study from one center. Endocrine. 2017;58(2):267-275.

- Petramala L, Olmati F, Concistrè A, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in patients with subclinical Cushing. Endocrine. 2020;70(1):150-163.

- Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Geiss LS. Prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. In: Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al., eds. Diabetes in America. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); 2018.

- Araujo-Castro M, Pascual-Corrales E, Lamas C. Possible, probable, and certain hypercortisolism: a continuum in the risk of comorbidity. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2023;84(2):272-284.

- Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):383-395.

- Gubbi S, Muniyappa R, Sharma ST, Grewal S, McGlotten R, Nieman LK. Mifepristone improves adipose tissue insulin sensitivity in insulin resistant individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(5):1501-1515.

- Fleseriu M, Biller BM, Findling JW, Molitch ME, Schteingart DE, Gross C. Mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, produces clinical and metabolic benefits in patients with Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):2039-2049.

- Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(10):653-662.

- van der Aart-van der Beek AB, de Boer RA, Heerspink HJL. Kidney and heart failure outcomes associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18(5):294-306.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).