Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Physicochemical Properties of Nanoparticles Influencing Oxidative Stress

2.1. NP Size and Surface Area

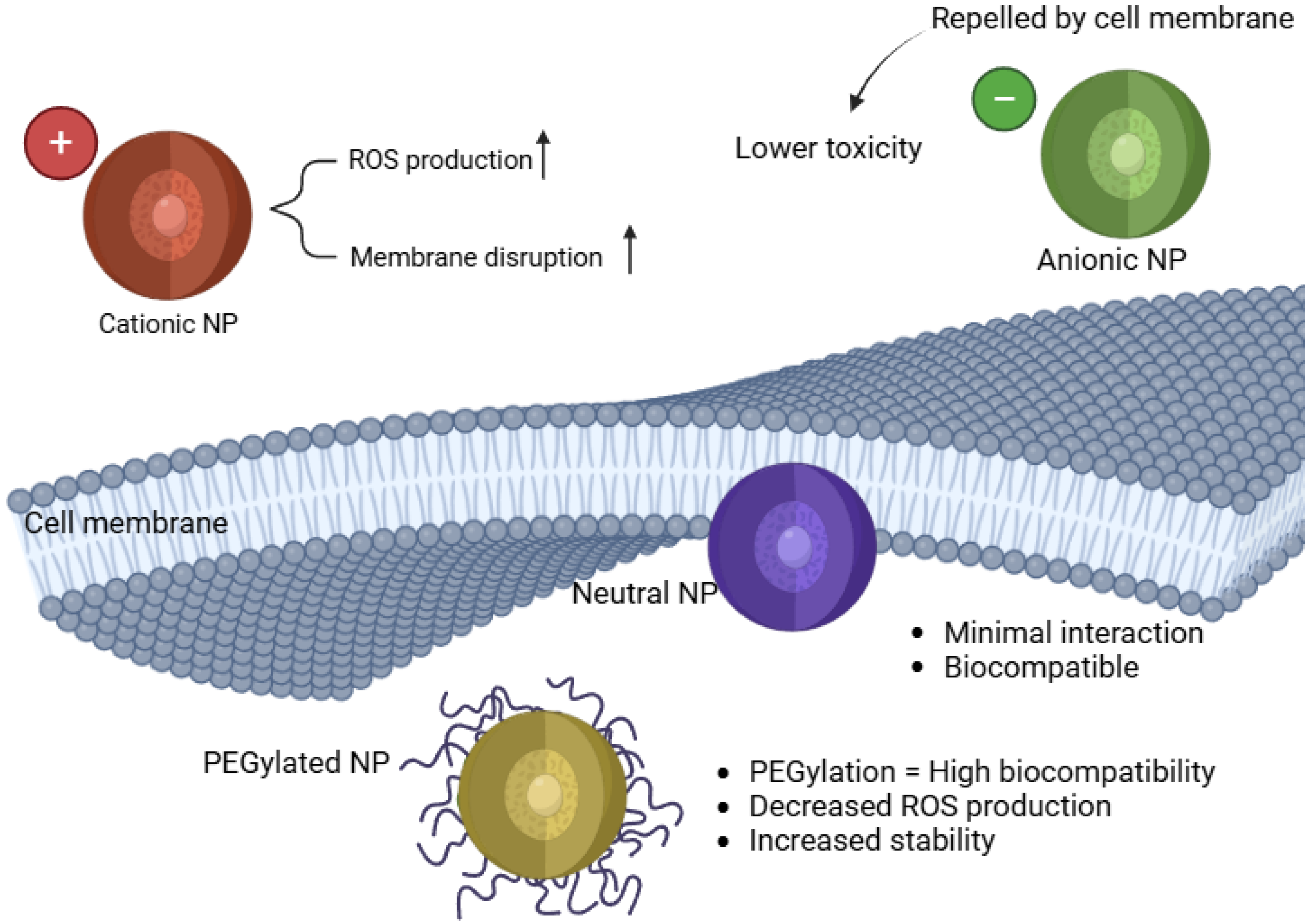

2.2. Surface Charge and Coating Effects

3. Oxidative Stress Pathways Activated by Nanoparticles in Zebrafish

3.1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptotic Pathways

3.2. Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation

3.3. Genotoxicity and Lipid Peroxidation

4. Experimental Approaches for Assessing Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish

4.1. Biochemical Assays for ROS and Antioxidant Activity

4.2. Gene expression Analysis of Oxidative Stress Pathways

4.3. Histopathological and Imaging Techniques

4.4. Behavioral and Physiological Endpoints

5. Pharmaceutical Applications of Nanoparticles Using Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Models

5.1. Nanoparticles as Antioxidant Therapeutics in Pharmaceutical Sciences

5.2. Natural Antioxidants Used in NP Formulations

5.3. Drug Delivery and Biocompatibility Testing

5.4. Balancing Toxicity versus Therapeutic Potential

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| CAT | Catalase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| DCFDA | 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Eustress and Distress in Redox Homeostasis; Elsevier Inc., 2019; ISBN 9780128131466.

- Nikalje, A. Nanotechnology and Its Applications in Medicine. Med chem. 2015, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-González, J. A Master Regulator of Oxidative Stress - The Transcription Factor Nrf2; 2016; ISBN 978-953-51-2838-0.

- Etheridge, M.L.; Campbell, S.A.; Erdman, A.G.; Haynes, C.L.; Wolf, S.M.; McCullough, J. The Big Picture on Nanomedicine: The State of Investigational and Approved Nanomedicine Products. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2013, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.A.; Kevadiya, B.D.; Bajwa, N.; Singh, P.A.; Zheng, H.; Kirabo, A.; Li, Y.L.; Patel, K.P. Role of Nanoparticle-Conjugates and Nanotheranostics in Abrogating Oxidative Stress and Ameliorating Neuroinflammation. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroumand, Z.; Golmakani, N.; Boroumand, S. Clinical Trials on Silver Nanoparticles for Wound Healing. Nanomed. J 2018, 5, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Saikia, S.K. Oxidative Stress in Fish: A Review. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 12, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed Azab, A.; A Adwas, Almokhtar; Ibrahim Elsayed, A. S.; A Adwas, A.; Ibrahim Elsayed, Ata Sedik; Quwaydir, F.A. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Mechanisms in Human Body. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 6, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.; Ward, A.C. Zebrafish as a Model to Evaluate Nanoparticle Toxicity. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutalik, C.; Nivedita; Sneka, C. ; Krisnawati, D.I.; Yougbaré, S.; Hsu, C.C.; Kuo, T.R. Zebrafish Insights into Nanomaterial Toxicity: A Focused Exploration on Metallic, Metal Oxide, Semiconductor, and Mixed-Metal Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, P.; Colombo, A.; Bengalli, R.; Gualtieri, M.; Zanoni, I.; Blosi, M.; Costa, A.; Mantecca, P. Functional Silver-Based Nanomaterials Affecting Zebrafish Development: The Adverse Outcomes in Relation to the Nanoparticle Physical and Chemical Structure. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2521–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugoni, V.; Camporeale, A.; Santoro, M.M. Analysis of Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. J. Vis. Exp. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormousoglou, M.; Efthimiou, I.; Antonopoulou, M.; Fetzer, D.L.; Hamerski, F.; Corazza, M.L.; Papadaki, M.; Santzouk, S.; Dailianis, S.; Vlastos, D. Investigation of the Genotoxic, Antigenotoxic and Antioxidant Profile of Different Extracts from Equisetum Arvense L. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourabit, S.; Fitzgerald, J.A.; Ellis, R.P.; Takesono, A.; Porteus, C.S.; Trznadel, M.; Metz, J.; Winter, M.J.; Kudoh, T.; Tyler, C.R. New Insights into Organ-Specific Oxidative Stress Mechanisms Using a Novel Biosensor Zebrafish. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lungu-Mitea, S.; Oskarsson, A.; Lundqvist, J. Development of an Oxidative Stress in Vitro Assay in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Cell Lines. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, N.; Long, D.; Cao, Y. The Uses of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) as an in Vivo Model for Toxicological Studies: A Review Based on Bibliometrics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugasan Kuppuswamy, J.; Seetharaman, B. Monocrotophos Based Pesticide Alters the Behavior Response Associated with Oxidative Indices and Transcription of Genes Related to Apoptosis in Adult Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Brain. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2020, 13, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharani, P.V.; Lian Wu, Y.; Gong, Z.; Valiyaveettil, S. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Models. Nanotechnology 2008, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YEŞİLBUDAK, B. Toxicological Aspects and Bioanalysis of Nanoparticles: Zebrafish Model. Open J. Nano 2023, 8, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G.; Stone, V.; Donaldson, K. Toxicology of Nanoparticles: A Historical Perspective. Nanotoxicology 2007, 1, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Bhargava, C.S.; Dubey, V.; Mishra, A.; Singh, Y. Silver Nanoparticles: Biomedical Applications, Toxicity, and Safety Issues. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 2, 2455–2698. [Google Scholar]

- Caloudova, H.; Hodkovicova, N.; Sehonova, P.; Blahova, J.; Marsalek, B.; Panacek, A.; Svobodova, Z. The Effect of Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions on Zebrafish Embryos (Danio Rerio). Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2018, 39, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Teulon, J.-M.; Godon, C.; Chantalat, L.; Moriscot, C.; Cambedouzou, J.; Odorico, M.; Ravaux, J.; Podor, R.; Gerdil, A.; Habert, A.; et al. On the Operational Aspects of Measuring Nanoparticle Sizes. Nanomaterials 2018, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Scalisi, E.M.; Pecoraro, R.; Cardaci, V.; Privitera, A.; Truglio, E.; Capparucci, F.; Jarosova, R.; Salvaggio, A.; Caraci, F.; et al. Effects of Carnosine on the Embryonic Development and TiO2 Nanoparticles-Induced Oxidative Stress on Zebrafish. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, L.; Arabeyyat, Z.H.; Xin, Q.; Paunov, V.N.; Dale, I.J.F.; Mills, R.I.L.; Rotchell, J.M.; Cheng, J. Silver Nanoparticles in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos: Uptake, Growth and Molecular Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Sharma, G.; Lee, S.S. Zebrafish: A Complete Animal Model to Enumerate the Nanoparticle Toxicity. J. Nanobiotechnology 2016, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Ilan, O.; Albrecht, R.M.; Fako, V.E.; Furgeson, D.Y. Toxicity Assessments of Multisized Gold and Silver Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Embryos. Small 2009, 5, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondarenko, O.; Juganson, K.; Ivask, A.; Kasemets, K.; Mortimer, M.; Kahru, A. Toxicity of Ag, CuO and ZnO Nanoparticles to Selected Environmentally Relevant Test Organisms and Mammalian Cells in Vitro: A Critical Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1181–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Thorat, S.T.; Gunaware, M.A.; Kumar, P.; Reddy, K.S. Unraveling Gene Regulation Mechanisms in Fish: Insights into Multistress Responses and Mitigation through Iron Nanoparticles. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ortiz, J.R.; Gonzalez, C.; Esquivel, K. Magnetic Iron Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Surface Enhancements, and Biological Challenges. Processes 2022, 10, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, W.; He, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Toxicity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to Zebrafish Embryo: A Physicochemical Study of Toxicity Mechanism. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2010, 12, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, S.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.C.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Mechanism. Nano-Micro Lett. 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavitri, N.G.; Syahbaniati, A.P.; Primastuti, R.K.; Putri, R.M.; Damayanti, S.; Wibowo, I. Toxicity Evaluation of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Green Synthesized Using Papaya Extract in Zebrafish. Biomed. Reports 2023, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahaby, S.A.; Farag, M.R.; Alagawany, M.; Taha, H.S.A.; Varoni, M.V.; Crescenzo, G.; Mawed, S.A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) Induce Cytotoxicity in the Zebrafish Olfactory Organs via Activating Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis at the Ultrastructure and Genetic Levels. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovrižnych, J.A.; Sotńikóva, R.; Zeljenková, D.; Rollerová, E.; Szabová, E.; Wimmerov́a, S. Acute Toxicity of 31 Different Nanoparticles to Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Tested in Adulthood and in Early Life Stages - Comparative Study. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2013, 6, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.J.; Sheng, J.; Hosseinian, F.; Willmore, W.G. Nanoparticle Effects on Stress Response Pathways and Nanoparticle–Protein Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.L.; Cronholm, P.; Gustafsson, J.; Möller, L. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Are Highly Toxic: A Comparison between Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooi, M.E.; Cappendijk, V.C.; Cleutjens, K.B.J.M.; Kessels, A.G.H.; Kitslaar, P.J.E.H.M.; Borgers, M.; Frederik, P.M.; Daemen, M.J.A.P.; van Engelshoven, J.M.A. Accumulation of Ultrasmall Superparamagnetic Particles of Iron Oxide in Human Atherosclerotic Plaques Can Be Detected by in Vivo Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circulation 2003, 107, 2453–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Liman, R.A.D.; Ruallo, J.M.S.; Villaflores, O.B.; Ger, T.-R.; Hsiao, C.-D. Potential Toxicity of Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Mohamed, A.S.R.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Lai, S.Y.; Fuller, C.D.; Shah, R.; Butler, R.T.; Weber, R.S. Ultra-small Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide (USPIO) Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Benign Mixed Tumor of the Parotid Gland. Clin. Case Reports 2021, 9, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, J.T.; Stark, D.D. Iron Oxide-Enhanced MR Imaging of the Liver and Spleen: Review of the First 5 Years. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1990, 155, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.; Zhang, M.; Kim, K. Quantum Dots and Their Interaction with Biological Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.R.; Zhu, Y.X.; Duan, Q.Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, F.G. Nanomaterials Meet Zebrafish: Toxicity Evaluation and Drug Delivery Applications. J. Control. Release 2019, 311–312, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, P.; Bao, X.; Su, P. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Mediated the Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Embryos. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielo, I.; Rando, G.; Giacobello, F.; Sfameni, S.; Castellano, A.; Galletta, M.; Drommi, D.; Rosace, G.; Plutino, M.R. Synthesis, Shemical–Physical Characterization, and Biomedical Applications of Functional Gold Nanoparticles: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, V.; Varunkumar, K.; Ravikumar, V.; Rajaram, R. Target Delivery of Doxorubicin Tethered with PVP Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles for Effective Treatment of Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kus-Liśkiewicz, M.; Fickers, P.; Ben Tahar, I. Biocompatibility and Cytotoxicity of Gold Nanoparticles: Recent Advances in Methodologies and Regulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, R.; Yang, B.; Wu, C.; Liao, M.; Ding, R.; Wang, Q. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Damage in the Liver and Kidney of Rats Following Exposure to Copper Nanoparticles for Five Consecutive Days. Toxicol. Res. (Camb). 2015, 4, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.Y.; Tai, Z.P.; Liu, J.X. Copper Nanoparticles and Silver Nanoparticles Impair Lymphangiogenesis in Zebrafish. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaharwar, U.S.; Meena, R.; Rajamani, P. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Induced Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Lymphocytes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Jenkins, G.J.S.; Asadi, R.; Doak, S.H. Potential Toxicity of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPION). Nano Rev. 2010, 1, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, H.; Shanmugam, V. A Review on Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Green Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle: Mechanism-Based Approach. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, S.; DeGiovanni, P.; Piel, B.; Rai, P. Cancer Nanomedicine: A Review of Recent Success in Drug Delivery. Clin. Transl. Med. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amora, M.; Schmidt, T.J.N.; Konstantinidou, S.; Raffa, V.; De Angelis, F.; Tantussi, F. Effects of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Zebrafish. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derfus, A.M.; Chan, W.C.W.; Bhatia, S.N. Probing the Cytotoxicity of Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.; Brodziak-Dopierała, B.; Loska, K.; Stojko, J. The Assessment of Toxic Metals in Plants Used in Cosmetics and Cosmetology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lungu, I.-I. Catechin-Zinc-Complex: Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Assessment. Farmacia 2023, 71, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marana, M.H.; Poulsen, R.; Thormar, E.A.; Clausen, C.G.; Thit, A.; Mathiessen, H.; Jaafar, R.; Korbut, R.; Hansen, A.M.B.; Hansen, M.; et al. Plastic Nanoparticles Cause Mild Inflammation, Disrupt Metabolic Pathways, Change the Gut Microbiota and Affect Reproduction in Zebrafish: A Full Generation Multi-Omics Study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.T.; Ozkemahli, G.; Shahbazi, R.; Erkekoglu, P.; Ulubayram, K.; Kocer-Gumusel, B. The Effects of Polymer Coating of Gold Nanoparticles on Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, C.; Simmet, T.; Syrovets, T. Role of Nanoparticle Surface Charge in Their Toxicity. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 575, 02009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, J.; Turcotte, P.; Gagnon, C.; Peyrot, C.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Gagne, F. The Influence of Surface Coatings of Silver Nanoparticles on the Bioavailability and Toxicity to Elliptio Complanata Mussels. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amora, M.; Raffa, V.; De Angelis, F.; Tantussi, F. Toxicological Profile of Plasmonic Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandarinezhad, S.; Wani, I.A.; Nourollahileilan, M.; Khosla, A.; Ahmad, T. Review—Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles/Nanocomposites as Electrochemical Biosensors for Cancer Detection. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 047504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batir-Marin, D.; Boev, M.; Cioanca, O.; Mircea, C.; Burlec, A.F.; Beppe, G.J.; Spac, A.; Corciova, A.; Hritcu, L.; Hancianu, M. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Enhancing Properties of Selective Equisetum Extracts. Molecules 2021, 26, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatero, I.; Casals, E.; Niemi, R.; Özliseli, E.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Sahlgren, C. Analyses in Zebrafish Embryos Reveal That Nanotoxicity Profiles Are Dependent on Surface-Functionalization Controlled Penetrance of Biological Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Kievit, F.M.; Cho, Y.-C.; Mok, H.; Press, O.W.; Zhang, M. Effect of Cationic Side-Chains on Intracellular Delivery and Cytotoxicity of PH Sensitive Polymer–Doxorubicin Nanocarriers. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, N.; Jahan, N.; Khalil-ur-Rahman; Anwar, T. ; Qureshi, H. Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles: Optimization, Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity, and Cytotoxicity Study by Hemolysis Assay. Front. Chem. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, L.; Johansen, P.L.; Koster, G.; Zhu, K.; Herfindal, L.; Speth, M.; Fenaroli, F.; Hildahl, J.; Bagherifam, S.; Tulotta, C.; et al. Zebrafish as a Model System for Characterization of Nanoparticles against Cancer. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercombe, L.; Veerati, T.; Moheimani, F.; Wu, S.Y.; Sood, A.K.; Hua, S. Advances and Challenges of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daraee, H.; Etemadi, A.; Kouhi, M.; Alimirzalu, S.; Akbarzadeh, A. Application of Liposomes in Medicine and Drug Delivery. Artif. Cells, Nanomedicine, Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TYAl-Abdullah, Z.; Al-Shawi, A.A.A.; Aboud, M.N.; Abdulaziz, B.A.A.; Al-Furaiji, H.Q.M.; Luaibi, I.N. Synthesis and Analytical Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles Using Microwave-Assisted Extraction System and Study Their Application in Degradation. J. Nanostructures 2020, 10, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, R.; Hwang, S.; Park, T.; Min, K.A.; Shin, M.C. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of PEGylated Starch-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhanced Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostovei, A. Practical Aspects of the Use of Acrylic Biomaterials in Dental Medical Practice. Med. Mater. 2022, 2, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, K.; Witcomb, M.J.; Scurrell, M.S. Polymer Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles: A Photochemical Synthesis Route. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 4459–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Tong, L.; Li, K.; Dong, Q.; Jing, J. Copper-Nanoparticle-Induced Neurotoxic Effect and Oxidative Stress in the Early Developmental Stage of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghibi, F.; Khalaj, A.; Mosaddegh, M.; Malekmohamadi, M.; Hamzeloo-Moghadam, M. Cytotoxic Activity Evaluation of Some Medicinal Plants, Selected from Iranian Traditional Medicine Pharmacopoeia to Treat Cancer and Related Disorders. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, G.; Deng, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, B.; Cao, Z.; Lu, H. Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Hepatic Dysfunction through the Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H.J.; Gillies, S.L.J.; Verdon, R.; Stone, V.; Henry, T.; Tran, L.; Tucker, C.; Rossi, A.G.; Tyler, C.R. Application of Transgenic Zebrafish for Investigating Inflammatory Responses to Nanomaterials: Recommendations for New Users. F1000Research 2023, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoud, H.A.; Ali, D.; Yaseen, K.N.; Almukhlafi, H.; Alothman, N.S.; Almutairi, B.; Almeer, R.; Alyami, N.; Alkahtani, S.; Alarifi, S. Dose-Dependent Variation in Anticancer Activity of Hexane and Chloroform Extracts of Field Horsetail Plant on Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, G.; He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J. Effects of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles on Developing Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2016, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochaa*, A.C.P.T.G.M.R.F.M.T.L. The Zebrafish Embryotoxicity Test (ZET) for Nanotoxicity Assessment: From Morphological to Molecular Approach. 2019, 110, 10–11.

- Tang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X. Toxic Effects of TiO2 NPs on Zebrafish. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, M. Dysfunction of Various Organelles Provokes Multiple Cell Death after Quantum Dot Exposure. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, Volume 13, 2729–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Song, J.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Silver Nanoparticles Induce Liver Inflammation through Ferroptosis in Zebrafish. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamboungou, J.; Canedo, A.; Qualhato, G.; Rocha, T.L.; Vieira, L.G. Environmental Risk of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle and Cadmium Mixture: Developmental Toxicity Assessment in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, S.; Botha, T.L.; Wepener, V. Influence of Different Functionalized CdTe Quantum Dots on the Accumulation of Metals, Developmental Toxicity and Respiration in Different Development Stages of the Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensado-López, A.; Fernández-Rey, J.; Reimunde, P.; Crecente-Campo, J.; Sánchez, L.; Torres Andón, F. Zebrafish Models for the Safety and Therapeutic Testing of Nanoparticles with a Focus on Macrophages. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Ren, X.; Zhu, R.; Luo, Z.; Ren, B. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Oxidative DNA Damage and ROS-Triggered Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis in Zebrafish Embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 180, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Y.; Torres-Duarte, C.; Oviedo, M.J.; Hirata, G.A.; Huerta-Saquero, A.; Vazquez-Duhalt, R. Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidation Induced by Different Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Organs. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2015, 13, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denluck, L.; Wu, F.; Crandon, L.E.; Harper, B.J.; Harper, S.L. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Is Likely a Driver of Copper Based Nanomaterial Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Yan, S.J. Silver Nanoparticles Have Lethal and Sublethal Adverse Effects on Development and Longevity by Inducing ROS-Mediated Stress Responses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, B.; Martins, M.; Samamed, A.C.; Sousa, D.; Ferreira, I.; Diniz, M.S. Toxicity Evaluation of Quantum Dots (ZnS and CdS) Singly and Combined in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario-Parés, U.; Castañaga, L.; Lacave, J.M.; Oron, M.; Reip, P.; Berhanu, D.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Cajaraville, M.P.; Orbea, A. Comparative Toxicity of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (CuO, ZnO and TiO2) to Developing Zebrafish Embryos. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2014, 16, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Demir, H.V. Color Science of Nanocrystal Quantum Dots for Lighting and Displays. Nanophotonics 2013, 2, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, D.; Signore, A.; Araneda, O.; Contreras, H.R.; Concha, M.; García, C. Toxicity and Differential Oxidative Stress Effects on Zebrafish Larvae Following Exposure to Toxins from the Okadaic Acid Group. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part A 2020, 83, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackmann, C.; Santos, M.M.; Rainieri, S.; Barranco, A.; Hollert, H.; Spirhanzlova, P.; Velki, M.; Seiler, T.-B. Novel Procedures for Whole Organism Detection and Quantification of Fluorescence as a Measurement for Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Larvae. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; He, Q.; Hou, H.; Han, J.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Cen, J.; Liu, K. Oxidative Stress-mediated Developmental Toxicity Induced by Isoniazide in Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrells, S.; Toruno, C.; Stewart, R.A.; Jette, C. Analysis of Apoptosis in Zebrafish Embryos by Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence to Detect Activated Caspase 3. J. Vis. Exp. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Tang, M. Progress on the Toxicity of Quantum Dots to Model Organism-zebrafish. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Yu, Y.; Shi, H.; Tian, L.; Guo, C.; Huang, P.; Zhou, X.; Peng, S.; Sun, Z. Toxic Effects of Silica Nanoparticles on Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae. PLoS One 2013, 8, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, F.; Uapipatanakul, B.; Lee, J.-S.; Hung, S.-M.; Huang, J.-C.; Pang, Y.-C.; Muñoz, J.E.R.; Macabeo, A.P.G.; Chen, K.H.-C.; Hsiao, C.-D. Co-Treatment of Copper Oxide Nanoparticle and Carbofuran Enhances Cardiotoxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascallar, M.; Alijas, S.; Pensado-López, A.; Vázquez-Ríos, A.J.; Sánchez, L.; Piñeiro, R.; de la Fuente, M. What Zebrafish and Nanotechnology Can Offer for Cancer Treatments in the Age of Personalized Medicine. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, S.; Chauhan, S.; Marcharla, E.; Alphonse, C.R.W.; Rajaretinam, R.K.; Ganesan, S. Developmental Toxicity and Neurobehavioral Effects of Sodium Selenite and Selenium Nanoparticles on Zebrafish Embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 266, 106791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, S.; Bhat, F.A.; Raja Singh, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Elumalai, P.; Das, S.; Patra, C.R.; Arunakaran, J. Gold Nanoparticle-Conjugated Quercetin Inhibits Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, Angiogenesis and Invasiveness via EGFR/VEGFR-2-Mediated Pathway in Breast Cancer. Cell Prolif. 2016, 49, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioanca, O.; Lungu, I.; Batir-marin, D.; Lungu, A.; Marin, G.; Huzum, R.; Stefanache, A.; Sekeroglu, N.; Hancianu, M. Modulating Polyphenol Activity with Metal Ions: Insights into Dermatological Applications. 2025, 1–18.

- Agraharam, G.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Nanoencapsulated Myricetin to Improve Antioxidant Activity and Bioavailability: A Study on Zebrafish Embryos. Chemistry (Easton). 2021, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatti Justino, A.; Prado Bittar, V.; Luiza Borges, A.; Sol Peña Carrillo, M.; Sommerfeld, S.; Aparecida Cunha Araújo, I.; Maria da Silva, N.; Beatriz Fonseca, B.; Christine Almeida, A.; Salmen Espindola, F. Curcumin-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles Attenuate AAPH-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity via Reduction of Lipid Peroxidation and Modulation of Antioxidant Parameters in a Chicken Embryo Model. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 646, 123486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, A.; Harshitha, M.; Kalladka, K.; Chakraborty, G.; Maiti, B. Exploring the Potential of Curcumin - Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for Angiogenesis and Antioxidant Proficiency in Zebrafish Embryo ( Danio Rerio ). Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, J.; El-Aneed, A. Properties, Engineering and Applications of Lipid-Based Nanoparticle Drug-Delivery Systems: Current Research and Advances. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 1237–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, S. ; Neves; Lúcio; Martins; Lima Novel Resveratrol Nanodelivery Systems Based on Lipid Nanoparticles to Enhance Its Oral Bioavailability. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2013, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, B.; Johnson, M.; Walker, M.; Riley, K.; Sims, C. Antioxidant Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Biology and Medicine. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dowding, J.M.; Klump, K.E.; McGinnis, J.F.; Self, W.; Seal, S. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Applications and Prospects in Nanomedicine. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1483–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani Asl, S.; Amiri, I.; Samzadeh- kermani, A.; Abbasalipourkabir, R.; Gholamigeravand, B.; Shahidi, S. Chitosan-Coated Selenium Nanoparticles Enhance the Efficiency of Stem Cells in the Neuroprotection of Streptozotocin-Induced Neurotoxicity in Male Rats. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 141, 106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Choudhary, N.; Nathiya, D.; Thakur, V.; Gupta, R.; Pramanik, S.; Kumar, P.; Gupta, N.; Patel, A. Recent Advances in Nanotechnology for Parkinson’s Disease: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Future Perspectives. Front. Med. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humulescu, I.; Flutur, M.M.; Cioancă, O.; Mircea, C.; Robu, S.; Marin-Batir, D.; Spac, A.; Corciova, A.; Hăncianu, M. Comparative Chemical and Biological Activity of Selective Herbal Extracts. Farmacia 2021, 69, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi Syahputra, R.; Dalimunthe, A.; Utari, Z.D.; Halim, P.; Sukarno, M.A.; Zainalabidin, S.; Salim, E.; Gunawan, M.; Nurkolis, F.; Park, M.N.; et al. Nanotechnology and Flavonoids: Current Research and Future Perspectives on Cardiovascular Health. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 120, 106355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, L.; Yoncheva, K. Resveratrol—A Promising Therapeutic Agent with Problematic Properties. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tărăboanță, I.; Burlec, A.F.; Stoleriu, S.; Corciovă, A.; Fifere, A.; Batir-Marin, D.; Hăncianu, M.; Mircea, C.; Nica, I.; Tărăboanță-Gamen, A.C.; et al. Influence of the Loading with Newly Green Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Equisetum Sylvaticum on the Antibacterial Activity and Surface Hardness of a Composite Resin. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xue, X.; Miao, X. Antioxidant Effects of Quercetin Nanocrystals in Nanosuspension against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in a Zebrafish Model. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.A.A.; Saleh, A.M. Applications of Nanoparticle Systems in Drug Delivery Technology. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourian, P.; Yazdani, G.; Ashraf, S.S.; Frounchi, M.; Mashayekhan, S.; Kiani, S.; Kakkar, A. Effect of Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticles on Their Intracellular Uptake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Tony To, S.S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J. Advances in Lipid-Based Drug Delivery: Enhancing Efficiency for Hydrophobic Drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1475–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, R.; Rasul, A.; Asghar, S.; Kovács, A.; Berkó, S.; Budai-Szűcs, M. Lipid Nanoparticles: An Effective Tool to Improve the Bioavailability of Nutraceuticals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, H.F.; Shurbaji, S.; Zakaria, Z.Z.; Hasan, M.H.; Goracinova, K.; Korashy, H.M.; Yalcin, H.C. Reduced Cardiotoxicity of Ponatinib-Loaded PLGA-PEG-PLGA Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Xenograft Model. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei Mirakabad, F.S.; Nejati-Koshki, K.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Yamchi, M.R.; Milani, M.; Zarghami, N.; Zeighamian, V.; Rahimzadeh, A.; Alimohammadi, S.; Hanifehpour, Y.; et al. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles as Cancer Drug Delivery Systems. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deenathayalan, U.; Nandita, R.; Kavithaa, K.; Kavitha, V.S.; Govindasamy, C.; Al-Numair, K.S.; Alsaif, M.A.; Cheon, Y.P.; Arul, N.; Brindha, D. Evaluation of Developmental Toxicity and Oxidative Stress Caused by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Zebra Fish Embryos/ Larvae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 4954–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučuk, N.; Primožič, M.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Sustainable Biodegradable Biopolymer-Based Nanoparticles for Healthcare Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Tian, S.; Cai, Z. Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Early Life Stages. PLoS One 2012, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanoparticle Type | Small Size (≤20 nm) | Medium Size (20–50 nm) | Large Size (>50 nm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Moderate ROS | Minimal ROS | [11,19,22,25] |

| Au NPs | Pro-inflammatory Effects | Minimal Effects | Low ROS | [19,26,27] |

| Cu NPs | DNA Damage | Inflammation | Low ROS | [28] |

| Fe NPs | Cellular Damage | Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Low ROS | [29,30] |

| ZnO NPs | Apoptosis | Moderate ROS | Low ROS | [31,32,33,34] |

| TiO₂ NPs | Neurotoxicity, Behavioral Disruptions | Moderate ROS | Minimal ROS | [23,24] |

| CuO NPs | Genotoxicity | Cellular Stress | Minimal ROS | [35,36,37] |

| Fe₂O₃ NPs | DNA Fragmentation | Cellular Inflammation | Low ROS | [36,38,39,40,41] |

| CdSe QDs | DNA Damage, Apoptosis | Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Low ROS | [42,43] |

| ZnS QDs | Phototoxicity, Lipid Peroxidation | DNA Damage | Limited Cytotoxicity | [42,43] |

| Nanoparticle Type | Affected Organ/System | Mechanism of Toxicity | Key Biomarkers/ Cytokines | Observed Effects | Case Study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ NPs | Liver, Gills | ROS Overproduction, Antioxidant Enzyme Suppression | ↓ SOD, ↓ CAT, ↑ MDA | Oxidative stress-mediated toxicity | TiO₂ NPs reduced SOD and CAT activity in zebrafish liver cells | [24,48] |

| CuO NPs | Brain | Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Apoptotic Pathways | ↑ p53, ↑ Caspase-3, ↓ ATP | ROS-induced neurotoxicity | CuO NPs triggered apoptosis in zebrafish brain tissue via mitochondrial damage | [48,75,76] |

| Fe₂O₃ NPs | Gills, Immune System | NF-κB Activation, Inflammatory Response | ↑ IL-8, ↑ IL-1β, ↑ NF-κB | Respiratory dysfunction, chronic inflammation | Fe₂O₃ NPs caused NF-κB-mediated inflammation in zebrafish gills | [29,77] |

| AgNPs | Liver | Hepatotoxicity, Cytokine Overexpression | ↑ TNF-α, ↑ IL-6 | Liver inflammation, oxidative damage | AgNPs upregulated TNF-α and IL-6 in zebrafish liver cells | [29,77,78] |

| ZnO NPs | Muscle, Liver | DNA Damage, Lipid Peroxidation | ↑ DNA Strand Breaks, ↑ MDA | Chromosomal instability, apoptosis | ZnO NPs induced DNA double-strand breaks in zebrafish embryos | [8,34] |

| CdSe QDs | Brain, Muscle | Genotoxicity, Lipid Peroxidation | ↑ XRCC1, ↑ p53 | DNA fragmentation, neuronal dysfunction | CdSe QDs caused DNA strand breaks in zebrafish larvae | [9,26,79] |

| Technique | Purpose | Application in Zebrafish | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent ROS Detection (DCFDA Assay) | Measures intracellular ROS levels | Used to quantify oxidative stress in zebrafish tissues | AgNP-exposed zebrafish embryos show significant ROS increase in brain and liver | [87,94,95] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Ultrastructural analysis of NP localization and organelle damage | Identifies mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, and vacuolization | TiO₂ NPs accumulate in hepatic mitochondria, leading to apoptosis | [72,96] |

| Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining | Histopathological assessment of tissue damage and inflammation | Detects necrosis, epithelial degeneration, and immune cell infiltration | CuO NP exposure causes epithelial damage and chronic inflammation in zebrafish gills | [97] |

| TUNEL Assay (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) | Identifies apoptotic DNA fragmentation | Used to assess neurotoxicity and genotoxicity in zebrafish tissues | CdSe QD exposure leads to increased TUNEL-positive cells in zebrafish brain | [98,99] |

| Type of Antioxidant-Functionalized NP | Mechanism of Action | Effect in Zebrafish Models | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol-coated NPs (quercetin, catechins) | Enhance oxidative stress resistance by scavenging ROS | Reduce ROS levels and increase antioxidant enzyme activity in zebrafish tissues | [57,115,116] |

| Resveratrol-loaded liposomes | Improve bioavailability and stability of antioxidant compounds | Prevent lipid peroxidation and DNA damage in oxidative stress-exposed zebrafish embryos | [110,117] |

| Plant-derived antioxidant NPs | Provide biocompatible approaches for reducing oxidative toxicity | Decrease apoptosis and inflammatory response in zebrafish liver and brain tissues | [118,119] |

| Liposomal curcumin NPs | Target oxidative damage by decreasing ROS accumulation and restoring mitochondrial function | Reduce oxidative damage in zebrafish liver tissue and improve metabolic activity | [108,109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).