1. Introduction

Vancomycin is a hydrophilic antibiotic belonging to the hydrophilic glycopeptide family [

1], with bactericidal activity against Gram-positive microorganisms as the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [

2], which are common in lower respiratory tract infections. These characteristics have positioned to the vancomycin as one of the most used antibiotics in the intensive care units (ICUs) [

3].

Vancomycin is mainly administered intravenously, where its absorption in not required, and with a pharmacokinetic profile characterized by either two or three compartment model. Based on different studies, and due its renal elimination, certain ranges have been established to study the vancomycin behavior. For instance, in patients with preserved kidney function, the alpha distribution phase may last 30-60 minutes, while the half-life in the beta elimination phase varies from 6 to 12 hours [

4]. The binding of vancomycin to plasma proteins is variable (range of 10-82%), with an average of 50-55% [

5], where its total volume distribution has been described in ranges of 0.4-1.0 L/kg. However, and depending on the physiopathological condition of patients, these parameters can vary dramatically [

6], affecting the efficacy of vancomycin.

Concerning the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models, several studies have demonstrated that the ratio between the area under the 24-h concentration-time curve (AUC

0–24) to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), is the best predictor model for vancomycin activity [

7]. However, this approximation does not consider the physiopathological changes in critical patients, where hypoalbuminemia, changes in volume distribution, renal dysfunction and alterations in tissue penetration are frequent [

8,

9]. Moise-Broder et al. observed that AUC

0–24/MIC values of ≥400 present successful outcomes in patients with S. aureus-associated pneumonia [

10], while lower values are associated with a poor eradication of the infection, longer treatment duration and high mortality rate [

11]. The optimal serum vancomycin trough concentration has been defined as ≥10 mcg/mL, and 15-20 mcg/mL for pathogens with MIC between 1-1.5 mcg/mL or complicated infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis and nosocomial pneumonia) [

12]. Levels <10 mcg/mL are associated with resistance generation, while levels >20 mcg/mL have been linked with toxic effects, mainly nephrotoxicity [

13,

14].

In general, vancomycin administration is done empirically and by intermittent infusions, as no clinical superiority has been demonstrated with prolonged or continuous infusion [

15]. This therapeutic scheme assumes that optimum concentrations with an adequate AUC

0–24 are obtained before fourth or fifth dose (second or third day), which generally coincides with the equilibrium or Steady-State (SS) in patients with preserved renal function [

16,

17]. However, in critically ill-patients, who may often have renal dysfunction, the vancomycin half-life increases, and the administration intervals must be modified, taking several days before SS is reached. This is a very delicate problem, because their critical conditions may be aggravated very rapidly without an adequate treatment. In this context, it has been reported that an initial vancomycin loading dose is useful to achieve adequate serum concentrations and an adequate AUC

0–24 from the first day of treatment, thus avoiding the appearance of resistance, therapeutic failure, and achieving a faster clinical response [

18,

19].

Therefore, in critically ill-patients is crucial to adapt the vancomycin treatment to their special condition to obtain efficacy form day one, considering this individually also for loading and maintenance dosing [

20]. The aim of this study was to individualize a dosage regimen of vancomycin in a cohort of Chilean critical patients by using a population pharmacokinetic software with the aim to optimize the pharmacological treatment, to offer a greater therapeutic success, patient safety and minimizing antibiotic resistance due to the selective pressure of susceptible microorganisms.

2. Results

2.1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

173 patients were admitted to the ICU, which 51 met the inclusion criteria of the clinical study (29.5% of the total). Out of these 51, 36 were male and 15 were female, with an average age of 56.19 ± 14.16 years and with stable estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Concerning to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II classification system for the severity score was 21 in the group of patients, in a scale between 0-30. The most prevalent pathologies in patients were high blood pressure (23%), cancer disease (18%) and type-II Diabetes Mellitus (17%). All these characteristics are detailed in

Table 1.

2.2. Vancomycin Treatment Characteristics

31 patients started with an empirical therapy and 20 with targeted therapy.

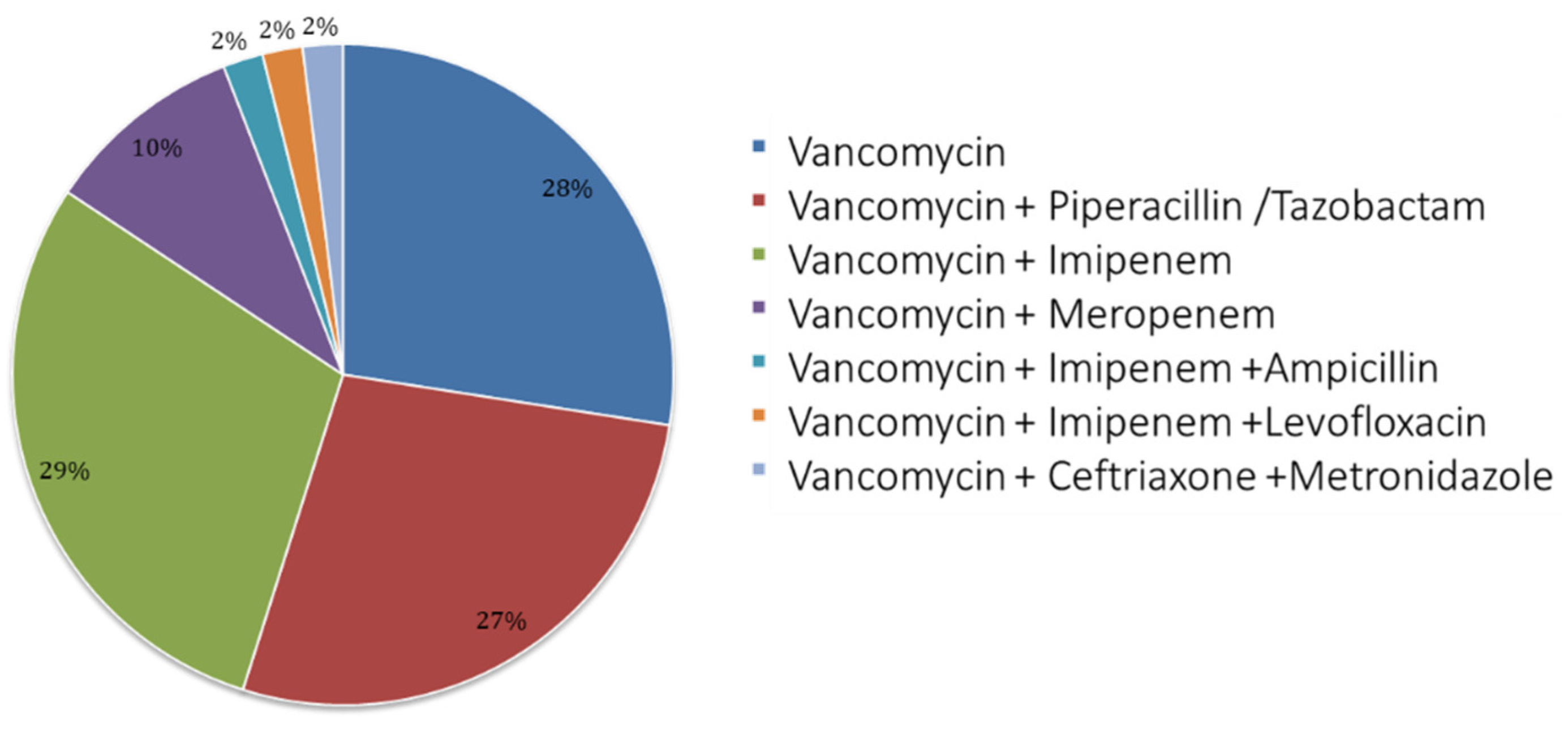

Figure 1 shows details of the vancomycin use and treatment scheme; mostly, patients received bi-therapy with Imipenem (29%), after monotherapy (28%) and then tri-therapy associated to piperacillin/tazobactam (27%).

2.3. Loading and Maintenance Doses Analyzed by the Antibiotic Kinetics® Software

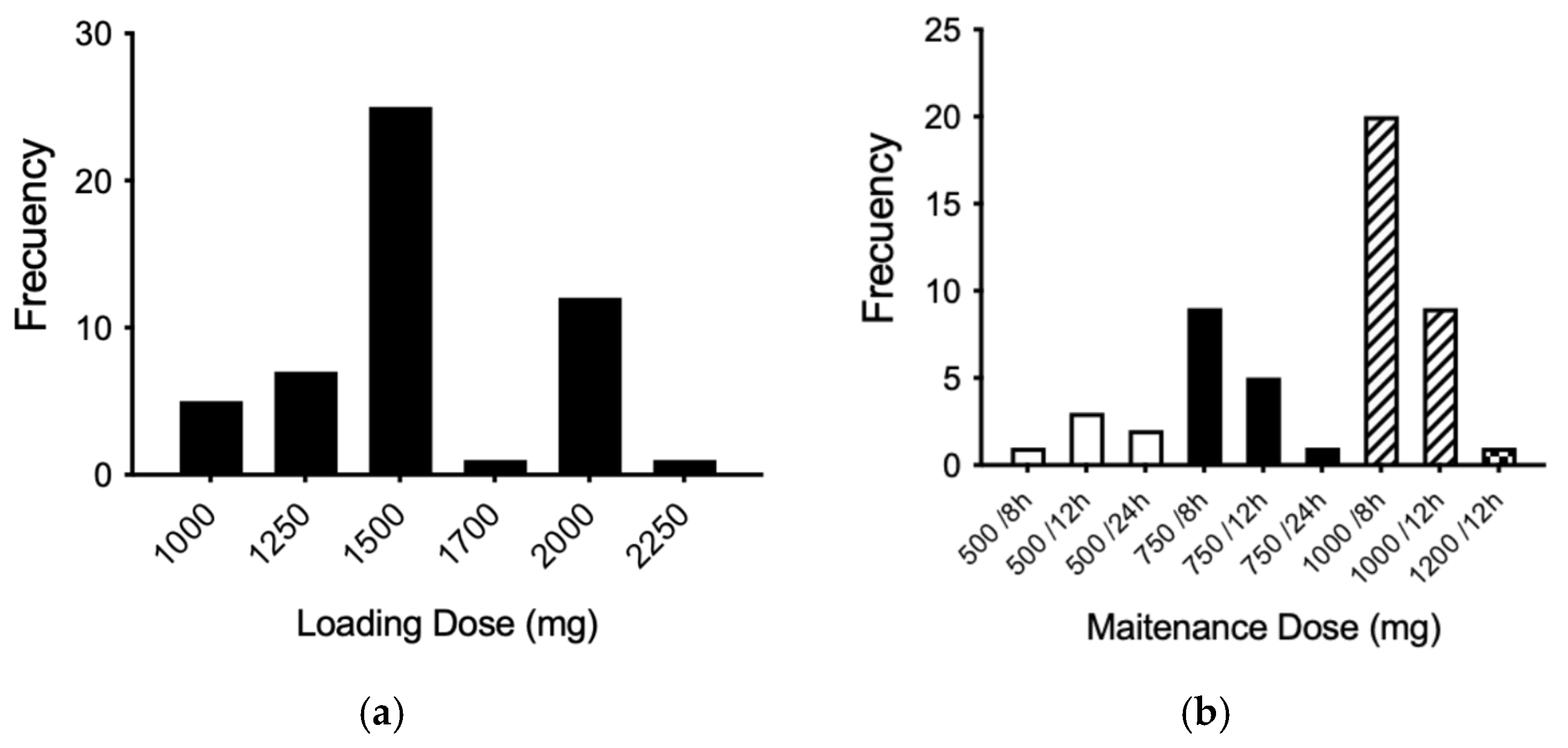

According to the theoretical population pharmacokinetic model established by the Antibiotic Kinetics

® software, the most prescribed loading dose was 1,500 mg, followed by 2,000 mg (

Figure 2a). In addition, the most widely used maintenance dose was 1,000 mg every 8 hours (three times a day), followed by the dose of 1,000 mg every 12 hours and the dose of 750 mg every 8 hours (

Figure 2b).

2.4. Analysis of Vancomycin Pharmacokinetics by Using the Antibiotic Kinetics® Software

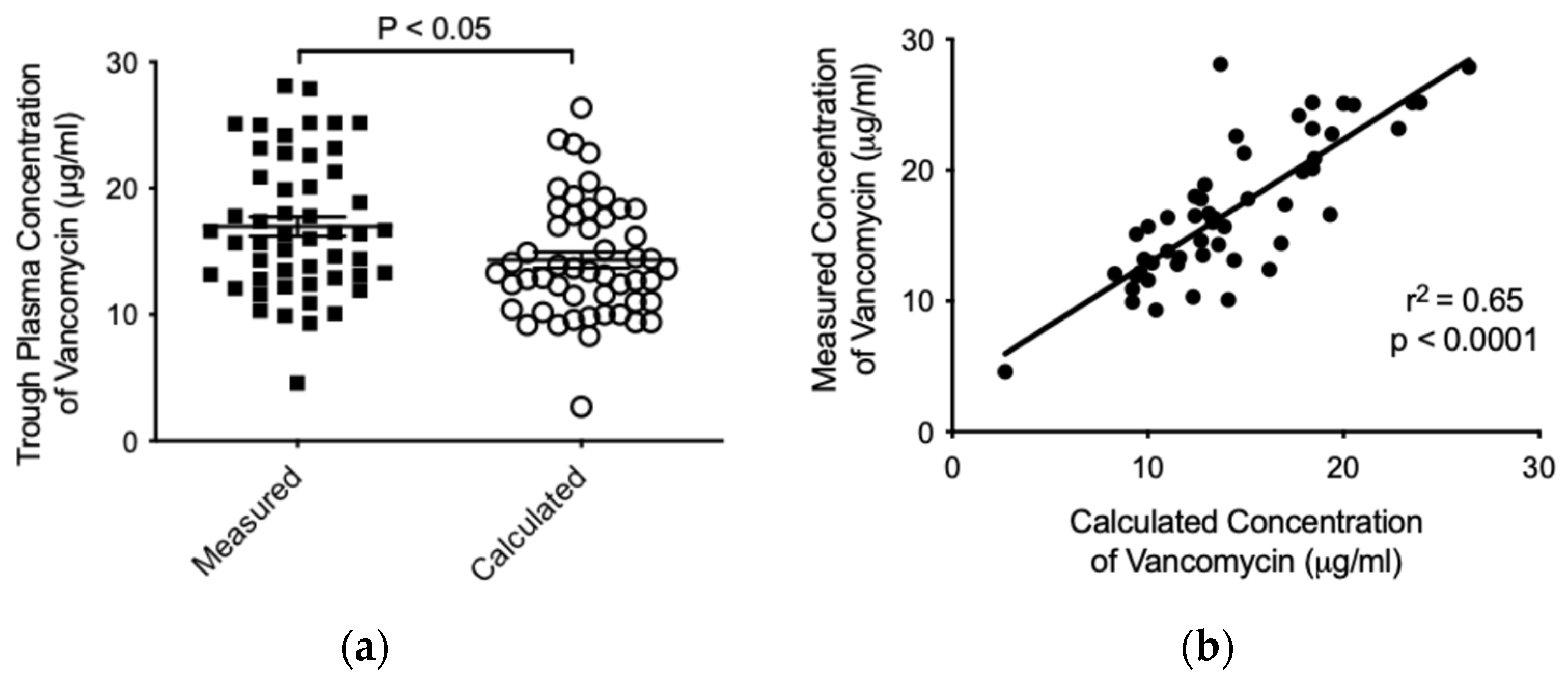

The average trough concentration measured for vancomycin in patients was higher in comparison to the calculated concentration by the Antibiotic Kinetics

® software (16.98 ± 5.423 versus 14.33 ± 4.630 μg/mL, respectively, p<0.05) (

Figure 3a). Finally, and with the aim to determine whether there was a relation among calculated and measured trough concentrations of vancomycin, we studied both variables showing a significant positive correlation (r

2 = 0.65; p<0.0001) (

Figure 3b). This tendency was verified independently for both genders (data no shown). Importantly, no vancomycin-associated adverse effect was observed in the patients during the treatment.

3. Discussion

Vancomycin is one of the most used antibiotics in health systems worldwide, which represents a challenge of its blood levels monitoring and continuous revisions of its different intravenous administration strategies in critically ill-patients. All of this, to achieve a more efficient clinical response by reaching therapeutic concentrations as soon as possible, as well as avoiding the appearance of resistance, and avoiding therapeutic failure [

21]. Such practices also have a cost effectiveness impact, which supports improved management processes and optimization of resources [

22].

Vancomycin treatment is widely used in many patients with impaired renal function and in these cases the measurement of plasma levels of the drug should be carefully monitored by each patient. This avoids toxicity, obtaining subtherapeutic plasma concentrations and avoiding further resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics [

23,

24].

In the study, the majority of the individuals included were male (70.6%), therefore, to objectify the great disparity by gender, the Department of Statistics of our center was asked for the list of admissions and discharges during the study period, and it was observed that there were a greater number of male patients (60.1%), thus our sample was nearly representative of the admissions in the period. It is worth mentioning that at our center there is a high complexity Maternity and Gynecology Unit that cares to many the population of Santiago and where many of these patients are admitted to the intensive care unit due to gynecological complications during pregnancy. Considering that one of the exclusion criteria in this study was the pregnancy of women, it could explain this gender disparity. Besides, this specific group has big changes in volumes of distribution and purification clearances, among other variations [

25,

26].

From

Figure 3 the trough values of plasma vancomycin concentrations predicted through the theoretical population model Antibiotic Kinetics

® are approximately within a range of safety for the patient [

27,

28]. The trough concentrations calculated by this model are generally lower when compared with trough values of measured serum vancomycin concentrations, considering the total population of patients monitored during the period covered by this study. However, the used population pharmacokinetic model is an efficient predictor of serum vancomycin concentrations measured by immunological method [

18,

22]. It is important to note that most patients which are routinely given vancomycin doses often reach concentrations outside the suggested therapeutic range for treatment of serious infectious diseases in critically ill patients [

8,

29,

30]. In addition, pharmacokinetic variables in critically ill-patients of extreme ages, with a special physiopathological condition, sex, weight, height, etc., are subject to a higher inter-variability [

31,

32]. For example, volume distribution and clearance elimination for vancomycin are altered in overweight patients, which conditions the dose adjustment in this group of patients [

33]. However, and considering that these variables can be adjusted by the Antibiotic Kinetics

® program, this adjustment was not considered because the new pharmacokinetic variables would be operator-dependent values, generating a possible bias when making the respective comparison between measured and calculated value.

In this study it was decided to assume standard pharmacokinetic variables for all patients studied [

34]. However, our results guide the use of individualized doses for each patient, compared to the dose usually used for all adult subjects. In addition, the patient’s characteristics (age, weight, height, underlying pathologies, etc.) and other pharmacokinetic variables (e.g. plasma protein binding) that may alter the plasma concentrations of vancomycin required to treat serious infections should be considered depending on the site of action [

35]. This could be explained by the wide range of plasma protein binding that vancomycin possesses, according to the nutritional status and degree of renal dysfunction that the individual may present. In addition, it should be considered that the volume of distribution to be considered when predicting a theoretical trough level significantly impacts the result of the real value obtained in blood [

33]. This is explained by the wide distribution of vancomycin, depending on anthropometric characteristics, severity condition and renal function of the patient. It is also important to consider that a single compartment model is assumed [

36]. Despite, having used higher doses than those usually administered, no patient presented or manifested any adverse event associated with vancomycin dosage and all the subjects studied were able to complete satisfactorily their antibacterial treatment, supporting the experimental strategy used to ensure patient safety. In general, monitoring of plasma concentrations in critical patients is essential considering the serious adverse events associated with and described using vancomycin (deterioration of kidney function, among others).

Currently, various guidelines recommend achieving AUC

0–24/MIC values between 400 and 600 as a safety and efficacy target for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections [

17]. In clinical practice, monitoring vancomycin trough plasma concentrations can help ensure appropriate therapeutic outcomes and enhance patient safety in the individualized management of critically ill patients. Despite the limited number of patients included in this study, we suggest that it is crucial to consider additional variables—such as pathophysiology, comorbidities, infection site, and pharmacokinetic variability—which play a key role in accurate dosing. Typically, vancomycin dosing and regimens are applied uniformly across patients. However, we emphasize the need for personalized treatment strategies to optimize therapeutic responses in critically ill patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects and Patient Selection

Patient selection was done at the ICU of the Hospital Clínico San Borja Arriarán, an adult tertiary hospital, between May and December 2015. The research was authorized by the Ethics Committees of the University of Chile, Faculty of Medicine (resolution on 11/08/2015) and the Central Metropolitan Health Service (resolution on 20/05/2015). This research was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Hospital.

We included patients with severe sepsis receiving empirical or directed treatment with intravenous vancomycin, according to the physician prescription, and patients in whom adequate measurement of serum vancomycin levels could be performed. On the other hand, we excluded pregnant women and patients on renal replacement therapy or in stage 5 for chronic kidney disease.

4.2. Vancomycin Loading Dose and Patients Follow-Up

Vancomycin intravenous treatment was initiated according to the clinical condition of patients and in schemes of monotherapy or combined with other antimicrobials (bi- or tri-therapy), which was indicated by the treating physician and validated by the infectious disease team. The criteria of vancomycin use involved an empirical therapy or a targeted therapy in patients with isolated microorganism and sensitivity to vancomycin treatment. However, the latter group also includes other patients with concomitant infection or those who started targeted therapy after starting the empirical one.

The theoretical calculation for vancomycin loading and maintenance doses was carried out by using the Antibiotic Kinetics

® software [

37], which uses anthropometric variables and laboratory analyses suggesting a dose regimen for a specific antibiotic through population variables. For vancomycin, it was proposed a Bayesian mono-compartmental model, after monitoring the drug serum levels and adjusting the further antibiotic treatment [

30,

38,

39].

It is important to note that in the ICU there is a strict and permanent monitoring of all clinical and laboratory parameters by system (renal, hepatic, cardiac, respiratory, metabolic function, etc.). Therefore, and because the potential risk of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity, continuous monitoring of eGFR was performed for each patient by using the Cockcroft-Gault (CG) equation, as well as the 6-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD-6v) formula. To minimize adverse drug reactions an active pharmacovigilance system carried out by pharmacists at ICU was done [

40].

4.3. Vancomycin Plasma Concentration Assay

After the loading dose and during the subsequent maintenance doses of vancomycin, blood samples were obtained. The collections were performed 30 minutes before the next dose (trough level), and plasma levels of vancomycin were measured by ADVIA Centaur® CP immunoassay system (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany).

4.4. Data Analysis and Statistic

Correlation data among calculated versus the measured trough concentrations for vancomycin was done by using Graph Prim 5.0f, and their difference was tested by Mann Whitney-nonparametric test. P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.

5. Conclusions

Here, a vancomycin dosage regimen was successfully introduced on an individual basis for each critically ill patient within the usual clinical practice by the treating physician. The introduction of this dosage regimen for vancomycin ensured its efficiency and safety, reducing the possibility of generating in-hospital resistance due to antibiotic pressure and reducing the risk of therapeutic failure due to inadequate doses. No risks or adverse events occurred during the treatment associated with this practice and therapeutic effectiveness was achieved with vancomycin through a population-based pharmacokinetic model, considering the conventional procedure of dosage by the treating physician.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.A. and A.V.; methodology, J.S.A.; software, C.A.A.; validation, L.Q., A.V. and C.A.A.; formal analysis, P.A. and C.A.A.; investigation, J.S.A., and A.V.; resources, J.S.A. and A.V.; data curation, J.S.A. and C.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.A. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, P.A., L.Q. and C.A.A; visualization, C.A.A.; supervision, L.Q.; project administration, J.S.A. and L.Q.; funding acquisition, C.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by the National Agency of Research and Development (ANID) - Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (Fondecyt) Regular 1231909 (C.A.A.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Chile, Faculty of Medicine (resolution on 11/08/2015) and the Central Metropolitan Health Service (resolution on 20/05/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (or their representants) involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All the data produced or examined in this study are available within the article and its

supplementary online materials. For additional information, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APACHE |

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation |

| AUC0–24 |

Area under the 24-h concentration-time curve |

| CG |

Cockcroft-Gault |

| eGFR |

Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ICU |

Intensive care units |

| MDRD-6v |

6-Variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease |

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| PK/PD |

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic |

| SS |

Steady-State |

References

- Gopalakrishnan, A.V.; Sunish, S.C.; Mathew, B.S.; Prabha, R.; Mathew, S.K. Stability of Vancomycin in Whole Blood. Ther Drug Monit 2021, 43, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moellering, R.C. Vancomycin: A 50-Year Reassessment. Clin Infect Dis 2006, 42 (Suppl. 1), S3–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Castro, D.; Dresser, L.; Granton, J.; Fan, E. Pharmacokinetic Alterations Associated with Critical Illness. Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Krekels, E.H.J.; Smit, C.; van Dongen, E.P.A.; Brüggemann, R.J.M.; Knibbe, C.A.J. How to Dose Vancomycin in Overweight and Obese Patients with Varying Renal (Dys)Function in the Novel Era of AUC 400-600 Mg·h/L-Targeted Dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet 2024, 63, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaert, M.; Spriet, I.; Allegaert, K.; Smits, A.; Vanstraelen, K.; Peersman, N.; Wauters, J.; Verhaegen, J.; Vermeersch, P.; Pauwels, S. Factors Impacting Unbound Vancomycin Concentrations in Different Patient Populations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 7073–7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, T.; Mizokami, F.; Fukami, K.; Ito, K.; Shibasaki, M.; Nagamatsu, T.; Furuta, K. The Influence of Severe Hypoalbuminemia on the Half-Life of Vancomycin in Elderly Patients with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin Interv Aging 2013, 8, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.-H.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, H.; Lee, M.J.; Jung, Y.; Kim, G.; Hwang, J.-H.; Kim, N.-H.; Kim, M.; Kim, C.-J.; et al. Impact of Area under the Concentration-Time Curve to Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Ratio on Vancomycin Treatment Outcomes in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteraemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015, 46, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.M.; Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J. Antimicrobial Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Issues in the Critically Ill with Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Clin 2011, 27, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulldemolins, M.; Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J.; Rello, J. Antibiotic Dosing in Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome. Chest 2011, 139, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise-Broder, P.A.; Forrest, A.; Birmingham, M.C.; Schentag, J.J. Pharmacodynamics of Vancomycin and Other Antimicrobials in Patients with Staphylococcus Aureus Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004, 43, 925–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullar, R.; Davis, S.L.; Levine, D.P.; Rybak, M.J. Impact of Vancomycin Exposure on Outcomes in Patients with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia: Support for Consensus Guidelines Suggested Targets. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 52, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Oda, K.; Shoji, K.; Hanai, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Fujii, S.; Hamada, Y.; Kimura, T.; Mayumi, T.; Ueda, T.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Vancomycin in the Framework of Model-Informed Precision Dosing: A Consensus Review by the Japanese Society of Chemotherapy and the Japanese Society of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Munakata, S.; Tokimatsu, I.; Hattori, N.; Kotani, T.; Kusumoto, S.; Sagara, H.; Kato, M. Prediction of Area Under the Curve from Urinary Vancomycin Concentrations Measured Using a Simple Method. AAPS J 2025, 27, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasowski, E.J.; Murray, K.P.; Trinh, T.D.; Finch, N.A.; Pogue, J.M.; Mynatt, R.P.; Rybak, M.J. Identification of Vancomycin Exposure-Toxicity Thresholds in Hospitalized Patients Receiving Intravenous Vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e01684-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.-J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.-X. Continuous versus Intermittent Infusion of Vancomycin in Adult Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016, 47, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Norris, R.; Barras, M.; Roberts, J.; Morris, R.; Doogue, M.; Jones, G.R.D. Therapeutic Monitoring of Vancomycin in Adult Patients: A Consensus Review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society Of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Biochem Rev 2010, 31, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rybak, M.J.; Le, J.; Lodise, T.P.; Levine, D.P.; Bradley, J.S.; Liu, C.; Mueller, B.A.; Pai, M.P.; Wong-Beringer, A.; Rotschafer, J.C.; et al. Therapeutic Monitoring of Vancomycin for Serious Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections: A Revised Consensus Guideline and Review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Adults and Children. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 52, e18–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.F.; Murray, B.E. Point: Vancomycin Is Not Obsolete for the Treatment of Infection Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 44, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, O.; Plaza-Plaza, J.C.; Ramirez, M.; Peralta, A.; Amador, C.A.; Amador, R. Pharmacokinetic Assessment of Vancomycin Loading Dose in Critically Ill Patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e00280-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, N.; Martín-Suárez, A.; Pérez, M.P.; González, F.M.; Fernández de Gatta, M.D.M. Vancomycin Dosing Assessment in Intensive Care Unit Patients Based on a Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Simulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010, 70, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, R.; López Cortés, L.E.; Molina, J.; Cisneros, J.M.; Pachón, J. Optimizing the Clinical Use of Vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 2601–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaijamorn, W.; Wanakamanee, U. Pharmacokinetics of Vancomycin in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Continuous Venovenous Haemodialysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014, 44, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, T.R.; Silinskie, K.M.; Hite, M.S.; Bress, J. Pharmacokinetics of Vancomycin in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Sustained Low-Efficiency Dialysis. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaid, A.S.; Hites, M.; Lipman, J.; Taccone, F.S.; Roberts, J.A. Effect of Obesity on the Pharmacokinetics of Antimicrobials in Critically Ill Patients: A Structured Review. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016, 47, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrami, B.; Najmeddin, F.; Mousavi, S.; Ahmadi, A.; Rouini, M.R.; Sadeghi, K.; Mojtahedzadeh, M. Achievement of Vancomycin Therapeutic Goals in Critically Ill Patients: Early Individualization May Be Beneficial. Crit Care Res Pract 2016, 2016, 1245815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momattin, H.; Zogheib, M.; Homoud, A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Safety and Outcome of Pharmacy-Led Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring. Chemotherapy 2016, 61, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeseker, M.; Croes, S.; Neef, C.; Bruggeman, C.; Stolk, L.; Verbon, A. Evaluation of Vancomycin Prediction Methods Based on Estimated Creatinine Clearance or Trough Levels. Ther Drug Monit 2016, 38, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J. Pharmacokinetic Issues for Antibiotics in the Critically Ill Patient. Crit Care Med 2009, 37, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Tanaka, K.; Komori, K.; Sadamitsu, D. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Criteria and Vancomycin Dose Requirement in Patients with Sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2013, 39, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmisky, D.E.; Griffiths, C.L.; Templin, M.A.; Norton, J.; Martin, K.E. Evaluation of a New Vancomycin Dosing Protocol in Morbidly Obese Patients. Hosp Pharm 2015, 50, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prybylski, J.P. Vancomycin Trough Concentration as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masich, A.M.; Kalaria, S.N.; Gonzales, J.P.; Heil, E.L.; Tata, A.L.; Claeys, K.C.; Patel, D.; Gopalakrishnan, M. Vancomycin Pharmacokinetics in Obese Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hal, S.J.; Paterson, D.L.; Lodise, T.P. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Vancomycin-Induced Nephrotoxicity Associated with Dosing Schedules That Maintain Troughs between 15 and 20 Milligrams per Liter. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, J.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Ensom, M.H.H. Vancomycin Loading Doses: A Systematic Review. Ann Pharmacother 2015, 49, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, P.; Heintz, S.J.; Heintz, B.H. Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring for Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Receiving Intermittent Hemodialysis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2015, 72, 1856–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbPK Patient Data. Available online: http://rxkinetics.net/abpk.aspx (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Reardon, J.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Ensom, M.H.H. Vancomycin Loading Doses: A Systematic Review. Ann Pharmacother 2015, 49, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Oh, J.M.; Cho, E.M.; Jang, H.J.; Hong, S.B.; Lim, C.M.; Koh, Y.S. Optimal Dose of Vancomycin for Treating Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pneumonia in Critically Ill Patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 2011, 39, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.; Amador, C.; Plaza, J.C.; Correa, G.; Amador, R. Assessment of an active pharmacovigilance system carried out by a pharmacist. Rev Med Chil 2014, 142, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).