1. Introduction

Differential Evolution (DE) is a simple and effective evolutionary algorithm used to solve global optimization problems in continuous space. It has also been adapted for use in discrete, most commonly binary, spaces. The original version was defined for single-objective optimization and was later extended to multi-objective optimization. This line of research, which goes in many directions, highlights the significance of this metaheuristic.

In this paper, we focus our research on differential evolution for single-objective optimization in continuous space. It was introduced in 1996 by Storn and Price. Since then, numerous modifications and improvements have been proposed. This trend continues to the present day and has been especially noticeable in recent years. In the variety of algorithm improvements, it is difficult to determine which one represents a truly significant enhancement. In the paper, we examine the improvements of the DE algorithm that have been published primarily in the past year of algorithm development.

Each year at the Conference of Evolutionary Computation (CEC), a competition for single-objective real parameter numerical optimization is held, in which DE-based algorithms hold a prominent place. In the year 2024, among the six competing algorithms, four were derived from DE. These four are of particular interest to us in this paper. One algorithm from the recent past is also included in comparison to assess whether 2024 brings significant progress in development.

In literature, algorithms are compared using different statistical techniques to perform single-problem and multiple-problem analysis. Non-parametric statistical tests are commonly used as they are less restrictive than parametric tests. In this paper, we adapted the same tests and add the Mann-Whitney U-score test, which has been used to determine the winners in the most recent CEC 2024 competition. The computation of the U-score in our research slightly differs from that used in CEC 2024, as will be described later in the paper. The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides the necessary background knowledge to understand the main ideas of the paper. This section outlines the basic DE algorithm and includes brief descriptions of the statistical tests used in the research. Related work is discussed in

Section 3. The algorithms used for comparison are described in

Section 4, where their main components are highlighted. The algorithms are complex, with several integrated mechanisms and applied settings. Complete descriptions of them are provided with references to the original papers in which they were defined.

Section 5 outlines the methodology for the comparative analysis. Extensive experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the comparative algorithms are presented in

Section 6. This section also discusses the obtained results.

Section 7 highlights the most promising mechanisms integrated into algorithms under research. Finally,

Section 8 summarizes the findings and concludes the paper, offering suggestions for future research directions.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Differential Evolution

In this subsection, we review the DE algorithm [

1,

2], as it serves as the core algorithm for the further advancements studied in this paper. An optimization algorithm aims to identify a vector

so as to optimize

.

D is the dimensionality of the function

f. The variables’ domains are defined by their lower and upper bounds:

.

DE is a population-based algorithm where each individual in the population is represented by a vector . denotes the population size, and g represents the generation number. During each generation, DE applies mutation, crossover, and selection operations to each vector (target vector) to generate a trial vector (offspring).

Mutation generates the mutant vector

according to

Indexes

are randomly selected within the range

and they are pairwise different among each other and from index

i.

Crossover generates a new vector

is the

j-th evaluation of the uniform random generator number.

is a randomly chosen index.

Selection performs a greedy selection scheme:

The initial population is selected uniformly at random within the specified lower and upper bounds defined for each variable . The algorithm iterates until the termination criterion is satisfied.

Subsequently, in addition to (

1) and (

2), other mutation and crossover strategies were proposed in literature [

3,

4,

5]. Although the core DE has significant potential, modifications to its original structure were recognized as necessary to achieve substantial performance improvements.

2.2. Statistical Tests

DE belongs to the stochastic algorithms that can return a different solution in each run, as they use random generators. Therefore, we run the stochastic algorithms several times and statistically compare the obtained results. Based on this, we can then say that a given algorithm is statistically better (worse) than another algorithm with a certain level of significance.

Statistical tests designed for statistical analyses are classified into two categories: parametric and non-parametric. Parametric tests are based on assumptions that are most probably violated when analyzing the performance of stochastic algorithms based on computational intelligence. For this reason, in this paper, we use several non-parametric tests for pairwise and multiple comparisons.

To infer information about two or more algorithms based on the given results, two hypotheses are formulated, the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . The null hypothesis is a statement of no difference, whereas the alternative hypothesis represents the presence of a difference between algorithms. When using a statistical procedure to reject a hypothesis, a significance level is set to determine the threshold at which the hypothesis can be rejected. Instead of predefining a significance level (), the smallest significance level that leads to the rejection of can be calculated. This value, known as the p-value, represents the probability of obtaining a result at least as extreme as the observed one, assuming is true. The p-value provides insight into the strength of the evidence against . The smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence against . Importantly, it achieves this without relying on a predetermined significance level.

The simple sign test for pairwise comparison assumes that if the two algorithms being compared have equivalent performance, the number of instances where each algorithm outperforms the other would be roughly equal. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test does not merely count the wins for each algorithm; rather, it ranks the differences in performance and makes the statistics based on these rankings. This test takes the mean performance from multiple runs for each benchmark function of the two algorithms. Unlike parametric tests, where the null hypothesis assumes the equivalence of means, these tests define the null hypothesis () as the equivalence of medians.

The Friedman test is a non-parametric test used to detect differences in the performance of multiple algorithms across multiple benchmark functions. It is an alternative to the repeated-measures ANOVA when the assumptions of normality are not met. In this test, the null hypothesis states that the medians of the different algorithms are equivalent, while the alternative hypothesis suggests that at least two algorithms have significantly different medians. To compute the test statistic, the performance of each algorithm is ranked for each problem, and the average rank across all problems is then calculated for each algorithm. In post-hoc analysis (e.g., the Nemenyi test) following the Friedman test, the critical distance is a threshold used to determine whether the difference in performance is statistically significant.

The Mann-Whitney U-score test, which is also called the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, is another non-parametric statistical test used to compare two algorithms and determine whether one tends to have higher values than the other. The test ranks all results from both algorithms together. It calculates the sum of ranks for each algorithm. The test statistic (U) is derived from these rank sums. A significance test determines if the observed rank differences are unlikely under the null hypothesis, which assumes the two algorithms have identical distributions.

Readers interested in a more detailed explanation of statistical tests are advised to the literature [

6,

7]. Our research focuses on the results at the end of the optimization process, while others also consider the convergence of their results as it is also a desirable characteristic [

8].

3. Related Works

One of the first DE surveys was published by Neri and Tirronen in 2010 [

9], and another in 2011 by Das and Sugathan [

10]. The first one includes some experimental results obtained with the algorithms available at that time. The second review reviews the basic steps of the DE, discusses different modifications defined at that time, and also provides an overview of the engineering applications of the DE. Both surveys stated that DE will remain an active research area in the future. The time that followed confirmed this, as noted by the same authors who published the updated survey 5 years later [

3]. Several years later, Opara and Arabas in [

4] provided a theoretical analysis of DE and discussed the characteristics of DE genetic operators coupled with an overview of the population diversity and dynamics models. In 2020, Pant et al. [

5] published another survey of the literature on DE, which also provided a bibliometric analysis of DE. Some papers review specific components of DE. DE is very sensitive to its parameter settings, the authors in [

11,

12,

13,

14] reviewed parameter control methods. Piotrowski et al. [

15] analyzed population size settings and adaptation. Parouha and Verma reviewed hybrids with DE [

16]. Zhongqiang et al. [

17] made an exhaustive listing of more than 500 nature-inspired meta-heuristic algorithms. They also empirically analyzed 11 newly proposed meta-heuristics with a high number of citations, comparing them against 4 state-of-the-art algorithms, 3 of which were DE-based. Their results show that 10 out of 11 algorithms are less efficient and robust than 4 state-of-the-art algorithms, they are also inferior to them in terms of convergence speed and global search ability. Cited papers show that over time DE has evolved in many different directions and remains one of the most promising optimization algorithms. The present paper analyzes the DE algorithms which were proposed very recently. The focus is on their mechanisms and performance.

The algorithms proposed in the literature are very diverse in terms of exploration and exploitation capabilities, so it is important how we evaluate and compare them. In [

6], Derrac et al. give a practical tutorial on the use of statistical tests developed to perform both pairwise and multiple comparisons for multi-problem analysis. Traditionally algorithms are evaluated using non-parametric statistical tests with the sign test, the Friedman test, the Mann-Whitney test, and both the Wilcoxon Signed Rank and Rank Sum tests are among the most commonly used. They are based on ordinal results, like the final fitness values of multiple trials. Convergence speed is also an important characteristic of the optimization algorithm. A trial may also terminate upon reaching a predefined target value. In such cases, the outcome is characterized by both the time taken to achieve the target value (if achieved) and the final fitness value. The authors in [

8] propose a way to make existing non-parametric tests to compare both the speed and accuracy of algorithms. They demonstrate trial-based dominance using the Mann-Whitney U test to compute U-scores with trial data from multiple algorithms. The authors demonstrate that U-scores are much more effective than traditional ways to rank solutions of algorithms. Non-parametric statistical methods are time-consuming and primarily focus on mean performance measures. To use them, raw results of algorithms in comparison are needed. Goula and Sotiropoulo [

18] propose a multi-criteria decision-making technique to evaluate the performances of algorithms and rank them. Multiple criteria included best, worst, median, mean, and standard deviation of the error values. They employed equal weighting because the true weights of criteria are generally unknown in practice.

To perform a comparative analysis of algorithms, the selection of problems on which the algorithms are evaluated is crucial [

19]. During the last 20 years, several problem sets were defined. CEC’17 seems to be the most difficult, as it contains a low percentage of unimodal functions (7%), and a high percentage (70%) of hybrid or composition functions.

If we compare our research with related works, we would highlight the following: We conduct an in-depth comparison of the latest DE-based algorithms proposed in 2024 with the basic DE algorithm and the jSO algorithm [

20]. The analysis includes a wide range of dimensions:

,

,

, and

. To the best of our knowledge, such an in-depth analysis has not yet been performed.

4. Algorithms in the Comparative Study

In this section, we briefly describe the algorithms in comparison. We expose their main characteristics. Readers interested in detailed descriptions of the algorithms are encouraged to study given references. All algorithms are based on the original DE.

4.1. jSO

jSO was proposed in 2017 [

20]. It significantly improves the performance of basic DE. Its denominator is the SHADE algorithm [

21], proposed in 2013, which introduces external achieve

A into DE to enrich population diversity. The archive

A saves target vectors if trial vectors improve them. SHADE algorithm also introduces a history-based adaptation scheme for adjusting

and

. Successful

and

are saved into historical memory by using the weighted Lehmer mean in each generation. Using the external archive, the mutant vector is generated using a ”DE/currect-to-pbest/1” mutation strategy. In 2014, LSHADE [

22] added a linear population size reduction strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. Afterward, the iL-SHADE [

23] algorithm modifies its memory update mechanisms using an adjustment rule that depends on the evolution stage. Higher values for

and lower values for

F were propagated at the early stages of evolution with the idea of enriching the population diversity. It also uses linear increase greediness factor

p. jSO is based on iL-SHADE. It introduces a new parameter

to the scaling factor

F to the mutation strategy for tuning the exploration and exploitation ability. A smaller factor

is applied during the early stages of the evolutionary process, while a larger factor

is utilized in the later stages. Using a parameter

, jSO adapts a new weighted version of the mutation strategy ”DE/currect-to-pbest-w/1”.

4.2. jSOa

jSOa algorithm was proposed in 2024 [

24]. It proposes a more progressive update of external archive

A. In the SHADE algorithm, and subsequently in the jSO algorithm, when archive

A reaches a predefined size, space for new individuals is created by removing random individuals. A newly proposed jSOa introduces a more systematic approach for storing outperformed parent individuals in the archive of the jSO algorithm. When the archive reaches its full capacity, the individuals within it are sorted based on their functional values, dividing the archive into two sections: better and worse individuals. The newly outperformed parent solution is then inserted into the "worse" section, ensuring that better solutions are preserved while the less effective individuals in the archive are refreshed. Notably, the new parent solution can still be inserted into the archive, even if it performs worse than an existing solution already in the archive. Using this approach, 50% of better individuals in the archive are not replaced. Except for the archive, the other steps of the jSO algorithm remain unchanged in jSOa.

4.3. mLSHADE-LR

The mLSHADE-LR algorithm was also proposed in 2024 [

25]. Its core algorithm is LSHADE, which was extended into the LSHADE-EpSin algorithm with an ensemble approach to adapt the scaling factor using an efficient sinusoidal scheme [

26]. Additionally, LSHADE-EpSin uses a local search method based on Gaussian Walks, which is used in later generations to improve exploitation. In LSHADE-EpSin, a mutation strategy DE/current-to-pbest/1 with an external archive is applied. LSHADE-cnEpSin [

27] is the improved version of LSHADE-EpSin, which uses a practical selection for scaling parameter

F and a covariance matrix learning with Euclidean neighborhoods to optimize the crossover operator. mLSHADE-RL further enhances LSHADE-cnEpSin algorithm. It integrates three mutation strategies such as ”DE/current-topbest-weight/1” with archive, ”DE/current-to-pbest/1” without archive, and ”DE/current-to-ordpbest-weight/1”. It has been shown that multi-operator DE approaches adaptively emphasize better-performing operators at various stages. mLSHADE-RL [

25] also uses a restart mechanism to overcome the local optima tendency. It consists of two parts: detecting stagnating individuals and enhancing population diversity. Additionally, mLSHADE-RL applies a local search method in the later phase of the evolutionary procedure to enhance the exploitation capability.

4.4. RDE

RDE algorithm was also proposed in 2024 [

28]. Just like the previously introduced algorithms, RDE can also be understood as an improvement of the LSHADE algorithm. Like other algorithms, starting with SHADE, it uses an external archive. The research has demonstrated that incorporating multiple mutation strategies is beneficial; however, adding all-new strategies does not necessarily guarantee the best performance. RDE uses a hybridization of two mutation strategies, ”DE/current-to-pbest/1” and ”DE/current-to-order-pbest/1” strategies. The allocation of population resources between the two strategies is governed by an adaptive mechanism that considers the average fitness improvement achieved by each strategy. In RDE, parameters

F and

are adapted similarly to how they are in jSO. In LSHADE-RSP, the use of a fitness-based rank pressure was proposed for the first time [

29]. The idea is to correct the probability of different individuals being selected in DE, with rank indicators assigned to each of them. In RDE, the selection strategy from LSHADE-RSP was slightly modified, as it is based on three instead of two terms.

4.5. L-SRTDE

Like the previous three algorithms, L-SRTDE was also proposed in 2024 [

30]. It focuses on one of the most important parameters of the DE, the scaling factor. L-SRTDE adapts its value based on the success rate, which is defined as the ratio of improved solutions in each generation. The success rate also influences the parameter of the mutation strategy, which determines the number of top solutions from which the randomly chosen one is selected. Another minor modification in L-SRTDE is the usage of repaired crossover rate

. The idea is that instead of using the sampled crossover rate

for crossover, the actual

value is calculated as the number of replaced components divided by the dimensionality

D. All other characteristics of the L-SRTDE algorithm are taken from the L-NTADE algorithm [

31], which introduces the new mutation strategy, called ”r-new-to-ptop/n/t” and significantly alters the selection step.

5. Methodology

The purpose of the analysis is to evaluate the performance of recent DE-based algorithms. To evaluate their contributions we include both two well-established baselines and promising new algorithms. To maintain depth in the analysis without overwhelming complexity, we limited the selection of algorithms to recent CEC competition. In addition to the four DE-based algorithms from CEC’24, the basic DE and jSO algorithms were used as baselines. jSO is incorporated in the comparison, as it ranked in second place in the CEC 2017 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real Parameter Numerical Optimization. jSO is also a highly cited algorithm, as many authors use it as a baseline algorithm for further development.

The selected algorithms were analyzed separately for each problem dimension: 10, 30, 50, and 100. They were run on all test problems a predetermined number of times. The best error value every evaluations was recorded for each run. Run finished after a maximum number of function evaluations was reached. The maximum number of evaluations was determined based on the problem’s dimensionality and is the same for all algorithms.

Having raw results for all algorithms, five statistical measures were calculated: best, worst, median, mean, and standard deviation of the error values. The algorithms were evaluated using the following statistical tests: Wilcoxon signed ranks test, Friedman test, and Mann-Whitney U-score test. It is important to note that the computation of the U-score in this article differs from the U-score used in the CEC 2024 competition [

8,

32]. In our study, we applied the classic Mann-Whitney U-test, whereas the U-score in the CEC 2024 competition incorporates the "target-to-reach" value. Convergence speed was also analyzed using convergence plots.

6. Experiments

We conducted experiments in which we empirically evaluated the progress brought by the improvements to the DE algorithm over the past year. We included the following algorithms: basic DE, jSO [

20], jSOa [

24], mLSHADE-LR [

25], RDE [

28], and L-SRTDE [

30]. Although the authors of the algorithms have published some results, we conducted the runs ourselves in the study based on the publicly available source code of the algorithms. The experiments were performed following the instructions: experiments with the dimensions

,

,

, and

were done; each algorithm was run 25 times for each test function, and the average error of the best individual in the population was computed; each run stopped either when the error obtained was less than

or when the maximal number of evaluations

was achieved.

6.1. CEC’24 Benchmark Suite

CEC’24 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real Parameter Numerical Optimization was based on the CEC’17 benchmark suite, which is a collection of 29 optimization problems which are based on shifted, rotated, non-separable, highly ill-conditioned, and complex functions. The benchmark problems aim to replicate the behavior of real-world problems, which often exhibit complex features that basic optimization algorithms may struggle to capture. The functions are:

unimodal functions: Bent Cigar function and Zakharov function. Unimodal functions are theoretically the simplest and should present only moderate challenges for well-designed algorithms.

simple multimodal functions: Rosenbrock’s function, Rastrigin’s function, expanded Scaffer’s F6 function, Lunacek Bi_Rastrigin function, non-continuous Rastrigin’s function, Levy function, and Schwefel’s function. Simple multimodal functions, characterized by multiple optima, are rotated and shifted. However, their fitness landscape often exhibits a relatively regular structure, making them suitable for exploration by various types of algorithms.

hybrid functions formed as the sum of different basic functions: Each function contributes a varying weighted influence to the overall problem structure across different regions of the search space. Consequently, the fitness landscape of these functions often varies in shape across different areas of the search space.

composition functions formed as a weighted sum of basic functions plus a bias according to which component optimum is the global one: They are considered the most challenging for optimizers because they extensively combine the characteristics of sub-functions and incorporate hybrid functions as sub-components.

The search range is

. The functions are treated as black-box problems.

Table 1 presents function groups.

6.2. Results

In this subsection, we present experimental results using three metrics for a comparison of algorithms, namely the U-score, the Wilcoxon’s test, and the Friedman’s test. The experimental results were obtained on 29 benchmark functions for six selected algorithms (DE, jSO, jSOa, mLSHADE-LP, RDE, and L-SRTDE) on four dimensions (10, 30, 50, and 100). The main experimental results are summarized in the rest of this subsection, while additional detailed and collected results are placed in the Supplementary Materials:

Tables S1–S24 present the best, worst, median, mean, and standard deviation values after maximal number of function evaluations for six algorithms on 29 benchmark functions.

Convergence speed graphs are depicted in Figures S1–S16.

6.2.1. U-score

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the U-score values for six algorithms on 29 benchmark functions for dimensions

,

,

, and

, respectively. For each function, the rank of each algorithm is presented in

red. At the bottom of the table, a sum of the U-score values and a sum of ranks, RS, are shown.

6.2.2. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

Overall U-score values for each dimension are collected in

Table 6. In this table, ”Total” indicates a sum of the U-scores values over all dimensions (higher value is better), while ”totalRS” summarizes ranks of algorithms (lower value is better). Based on these results, we can see that L-SRTDE has the first rank, followed by RDE, jSOa, jSO, mLSHADE-LR, and DE. Although the U-score values in this paper differ slightly from those in the CEC 2024 competition due to differences in the computation procedure, as explained earlier, the ranking of the algorithms remains unchanged.

We also analyzed the performance of the algorithms across different function families (see

Table 1). To achieve this, we sum the U-score values of the algorithms for each function family and identify the best-performing algorithm for each function family across different problem dimensions. The obtained results are collected in

Table 7. For dimension 10, all algorithms perform equally well on unimodal functions. For multimodal functions, L-SRTDE achieves the best results, while jSOa outperforms all others on hybrid functions. For composition functions, RDE exhibits the best performance. For dimension 30, all algorithms, except for the original DE, perform equally well on unimodal functions. L-SRTDE is the top performer for both multimodal and hybrid functions, whereas RDE remains the best choice for composition functions. Similar trends are observed for dimension 50. However, for dimension 100, L-SRTDE outperforms all other algorithms across all function families except for unimodal functions, where jSOa achieves the best results.

The Wilcoxon Sign-rank test is used to compare two algorithms, and the number of all pairwise comparisons for six algorithms per one dimension is

. Altogether we have 60 comparisons. Usually, we only compare the newly designed algorithm with other algorithms, which reduces the number of comparisons. We chose L-SRTDE to compare it with other algorithms and the summarized results are presented in

Table 8. For each dimension, the comparison using the Wilcoxon sign-rank test with

of the L-SRTDE algorithm with other algorithms, and the summarized results are presented as +/≈/−. Sign ’+’ means that L-SRTDE performs significantly better than the compared algorithm, ’−’ means that L-SRTDE performs significantly worse than the compared algorithm, while ≈ means that there is no significant difference between compared algorithms. Detailed results are shown in Tables

S25,

S26,

27, and

28, while summarized results are collected in

Table 8. The L-SRTDE algorithm shows superiority over all other algorithms in all dimensions. The latter can be seen from the lines labeled ’Total’, which contain the sum of the values for each individual algorithm according to the dimension.

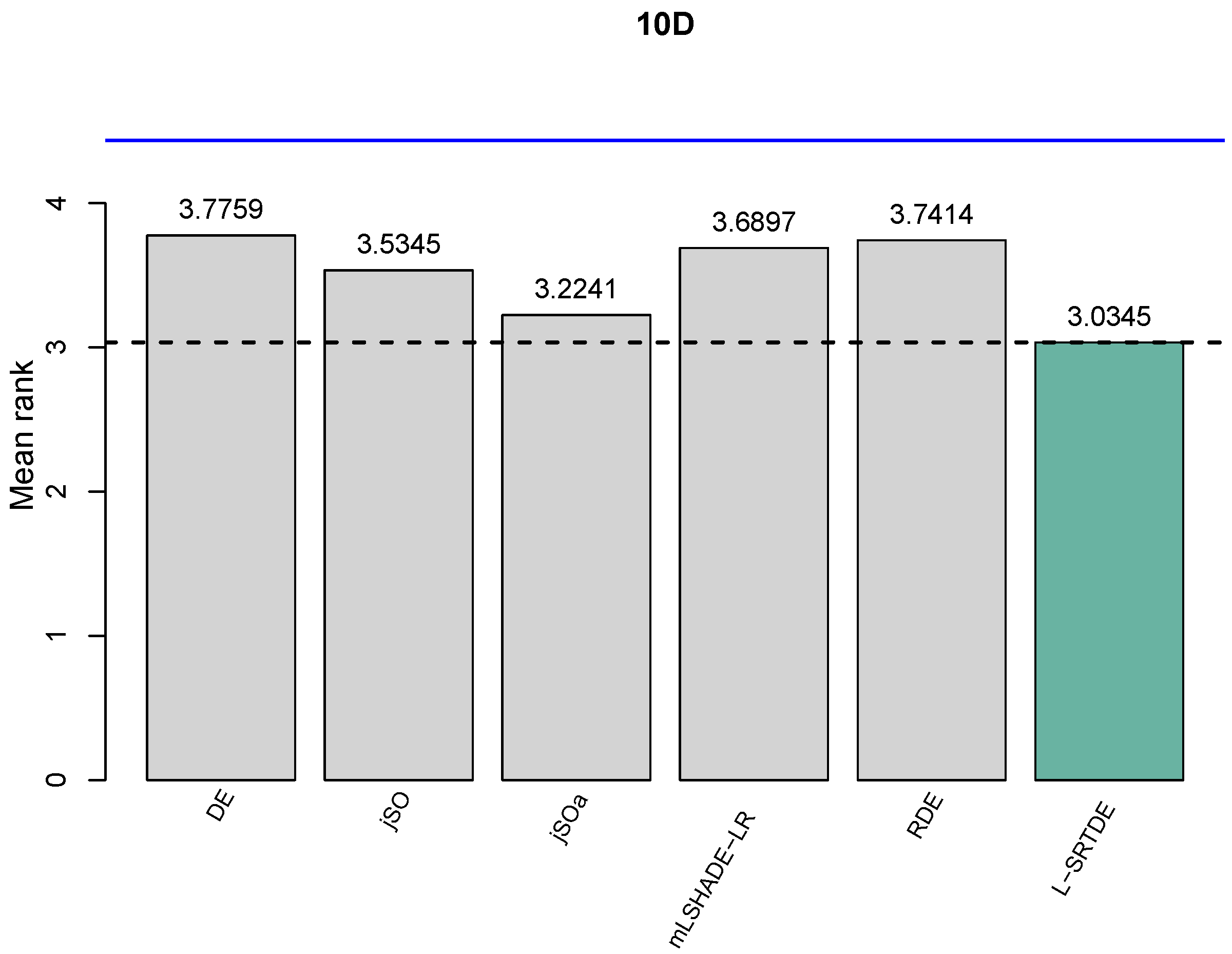

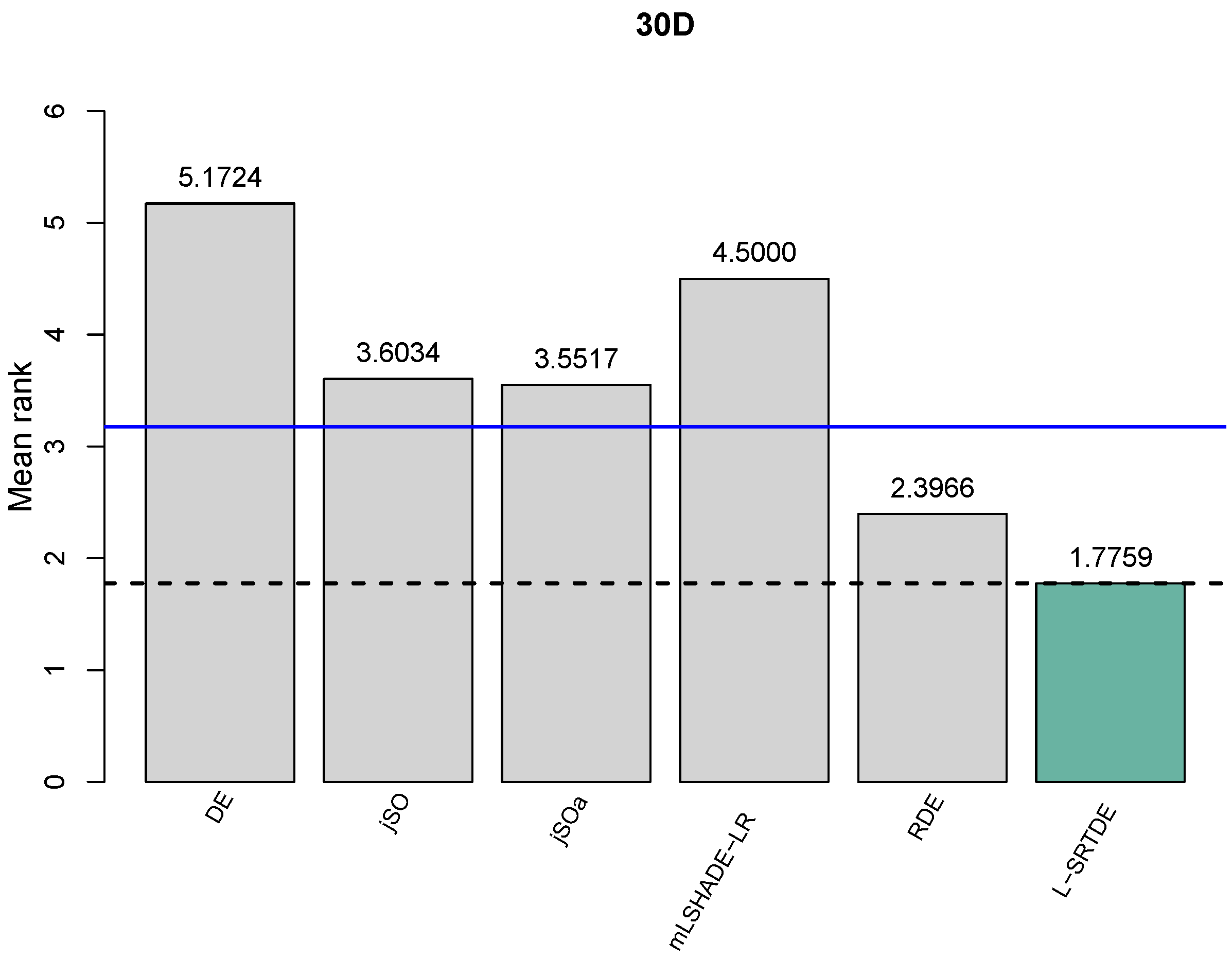

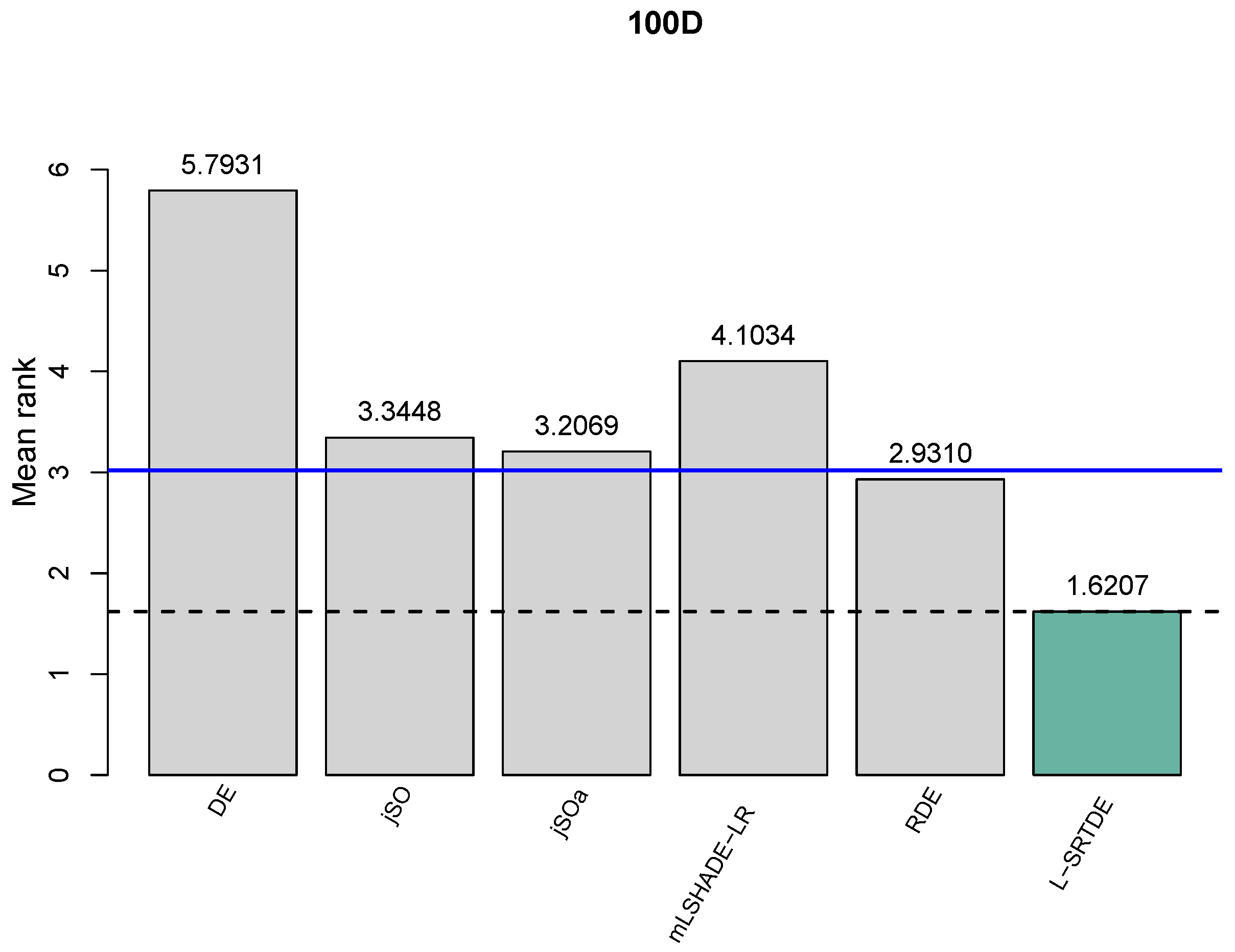

6.2.3. Friedman’s Test

As a third test to compare the algorithms, we used the Friedman test. The obtained results for each dimension are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 and and

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12. A critical distance indicates that there exists a statistical difference among two compared algorithms if the difference of their Friedman rank values is smaller than the critical value. We plot a dotted line of the best-obtained algorithm and the blue line to show the critical distance compared to the best-performed algorithm, which is depicted in green.

Figure 1 shows the comparison for

, and we can see that all six algorithms are below the critical distance from L-SRTDE, which is the best algorithm. It means, there are no significant differences among all six algorithms.

Table 9 tabulates Friedman ranks, shows a performance order in column Rank, and at the bottom of the table, the

and

p values of the Friedman test are reported. If the

p-value is lower than predefined significance level (

) it indicates that the algorithms have statistical significant performances.

The obtained results for

,

, and

are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively. One can see that L-SRTDE is statistically better than DE, jSO, jSOa, and mLSHADE-LR, while there is no statistical difference between L-SRTDE and RDE. This holds for each dimension of

,

, and

.

On , we can also see that algorithms RDE, jSOa, and jSO are close to the blue line (i.e., critical distance), and RDE is the only one that is slightly below the blue line.

In general, all three tests that were used in the comparison of six algorithms report very consistent comparison results for each dimension.

7. Discussion

The classic DE algorithm lacks the sophisticated mechanisms introduced in the algorithms, which were proposed later. While it is generally effective, it struggles with maintaining diversity and balancing exploration and exploitation without additional enhancements. It does not have adaptive mechanisms for F and , leading to suboptimal parameter tuning. It does not have an external archive or hybrid strategies, limiting diversity control. It does not use a restart mechanism, making it prone to premature convergence.

The ranking of compared algorithms reflects each algorithm’s ability to balance exploration and exploitation, maintain population diversity, and adapt to different stages of evolution. L-SRTDE leads due to its success rate-driven adaptation, refining both mutation and scaling. The repaired crossover rate () refines the crossover mechanism, ensuring more effective variation across dimensions. RDE follows closely, leveraging hybrid strategies and adaptive resource allocation. It combine ”DE/current-to-pbest/1” and ”DE/current-to-order-pbest/1”. The key improvement is in how resources are allocated between these strategies—an adaptive mechanism evaluates their average fitness improvement and adjusts accordingly. Additionally, RDE incorporates rank pressure-based selection, refining the probability of selecting individuals based on fitness ranks. jSOa stands out for its archive management, ensuring stability. Instead of randomly deleting older solutions, jSOa divides the archive into ”better” and ”worse” sections based on functional values, ensuring that stronger solutions are preserved while allowing some weaker solutions to be refreshed. This more structured archive update leads to better diversity retention without compromising convergence speed. jSO remains strong, though jSOa refines its archive. mLSHADE-LR’s multi-operator approach seems to be powerful.

Each of these algorithms offers unique strengths, but L-SRTDE currently represents the most advanced evolutionary strategy in this group of algorithms.

8. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive review of state-of-the-art algorithms based on Differential Evolution (DE) that have been proposed in recent years, including jSO, jSOa, mLSHADE-LP, RDE, and L-SRTDE, along with classic DE. We examined the key mechanisms incorporated into these algorithms and systematically compared their performance. Specifically, we identified shared and unique mechanisms among the algorithms.

To ensure robust performance evaluation, we employed statistical comparisons, which provide reliable insights into algorithm efficacy. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized for pairwise comparisons, while the Friedman test was applied for multiple comparisons. Additionally, the Mann-Whitney U test was incorporated to enhance the statistical rigor of our analysis. We also performed a cumulative assessment of the six algorithms and evaluated their performance across different function families, including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions.

The experimental evaluation was conducted on benchmark problems defined for the CEC’24 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real Parameter Numerical Optimization. We analyzed problem dimensions of 10, 30, 50, and 100, running all algorithms on our own with parameter settings as recommended by the original authors.

The key findings from our experiments indicate that all three statistical tests consistently ranked the algorithms in the following order: L-SRTDE achieved the highest rank, followed by RDE, jSOa, jSO, mLSHADE-LP, and classic DE. Notably, a similar ranking was obtained by the method proposed in [

8], which was also employed for algorithm ranking in CEC 2024 [

32]. However, CEC 2024 competition was performed only at dimension

[

32]. We extend the analysis to a lower dimension (

) as well as higher dimensions (

and

). The analysis across different function families ranks the algorithms slightly differently at dimension

; however, at

, L-SRTDE remains the best across all function families.

In conclusion, significant progress has been made since the first published Differential Evolution algorithm. The enhanced versions of DE now incorporate a variety of mechanisms, all of which collectively contribute to improved performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.M.; methodology, M.S.M. and J.B.; software, J.B.; validation, M.S.M. and J.B.; investigation, M.S.M. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B. and M.S.M.; writing—review and editing, J.B. and M.S.M.; visualization, J.B. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (research core funding No. P2-0069 — Advanced Methods of Interaction in Telecommunications and P2-0041 — Computer Systems, Methodologies, and Intelligent Services).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available as supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the developers of the jSOa, mLSHADE-LP, RDE, and L-SRTDE algorithms for making their source code publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of global optimization 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Price, K. Differential Evolution: a Practical Approach to Global Optimization; Springer Science & Business Media, 2005.

- Das, S.; Mullick, S.S.; Suganthan, P.N. Recent advances in differential evolution–an updated survey. Swarm and evolutionary computation 2016, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, K.R.; Arabas, J. Differential Evolution: A survey of theoretical analyses. Swarm and evolutionary computation 2019, 44, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Zaheer, H.; Garcia-Hernandez, L.; Abraham, A.; et al. Differential Evolution: A review of more than two decades of research. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 90, 103479. [Google Scholar]

- Derrac, J.; García, S.; Molina, D.; Herrera, F. A practical tutorial on the use of nonparametric statistical tests as a methodology for comparing evolutionary and swarm intelligence algorithms. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2011, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.; García, S.; Rueda, M.; Das, S.; Herrera, F. Recent trends in the use of statistical tests for comparing swarm and evolutionary computing algorithms: Practical guidelines and a critical review. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2020, 54, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.V.; Kumar, A.; Suganthan, P.N. Trial-based dominance for comparing both the speed and accuracy of stochastic optimizers with standard non-parametric tests. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2023, 78, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Tirronen, V. Recent advances in differential evolution: a survey and experimental analysis. Artificial intelligence review 2010, 33, 61–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Suganthan, P.N. Differential evolution: A survey of the state-of-the-art. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2011, 15, 4–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi, E.N.; Dafinescu, V. Parameter control and hybridization techniques in differential evolution: a survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2016, 45, 447–470. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A. Reviewing and benchmarking parameter control methods in differential evolution. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2019, 50, 1170–1184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Dabbagh, R.D.; Neri, F.; Idris, N.; Baba, M.S. Algorithmic design issues in adaptive differential evolution schemes: Review and taxonomy. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2018, 43, 284–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Davila, E.; Haro, E.H.; Casas-Ordaz, A.; Oliva, D.; Avalos, O. Differential Evolution: A Survey on Their Operators and Variants. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, pp. 1–30.

- Piotrowski, A.P. Review of differential evolution population size. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2017, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Parouha, R.P.; Verma, P. State-of-the-art reviews of meta-heuristic algorithms with their novel proposal for unconstrained optimization and applications. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 4049–4115. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wu, G.; Suganthan, P.N.; Song, A.; Luo, Q. Performance assessment and exhaustive listing of 500+ nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2023, 77, 101248. [Google Scholar]

- Goula, E.M.K.; Sotiropoulos, D.G. HRA: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Ranking Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.11617, arXiv:2409.11617 2024.

- Piotrowski, A.P.; Napiorkowski, J.J.; Piotrowska, A.E. Choice of benchmark optimization problems does matter. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2023, 83, 101378. [Google Scholar]

- Brest, J.; Maučec, M.S.; Bošković, B. Single objective real-parameter optimization: Algorithm jSO. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1311–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A. Evaluating the performance of SHADE on CEC 2013 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on evolutionary computation. IEEE; 2013; pp. 1952–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of SHADE using linear population size reduction. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE; 2014; pp. 1658–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Brest, J.; Maučec, M.S.; Bošković, B. iL-SHADE: Improved L-SHADE algorithm for single objective real-parameter optimization. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1188–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Bujok, P. Progressive Archive in Adaptive jSO Algorithm. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Trivedi, A.; et al. A Multi-operator Ensemble LSHADE with Restart and Local Search Mechanisms for Single-objective Optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.15994, arXiv:2409.15994 2024.

- Awad, N.H.; Ali, M.Z.; Suganthan, P.N.; Reynolds, R.G. An ensemble sinusoidal parameter adaptation incorporated with L-SHADE for solving CEC2014 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE; 2016; pp. 2958–2965. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, N.H.; Ali, M.Z.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble sinusoidal differential covariance matrix adaptation with Euclidean neighborhood for solving CEC2017 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE; 2017; pp. 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Zhao, R.; Wang, K.; Gao, S. An Efficient Reconstructed Differential Evolution Variant by Some of the Current State-of-the-art Strategies for Solving Single Objective Bound Constrained Problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16280, arXiv:2404.16280 2024.

- Stanovov, V.; Akhmedova, S.; Semenkin, E. LSHADE algorithm with rank-based selective pressure strategy for solving CEC 2017 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovov, V.; Semenkin, E. Success Rate-based Adaptive Differential Evolution L-SRTDE for CEC 2024 Competition. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovov, V.; Akhmedova, S.; Semenkin, E. Dual-Population Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm L-NTADE. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Ban, X.; Chen, P.; Price, K.V.; Suganthan, P.N.; Wen, X.; Liang, J.; Wu, G.; Yue, C. Performance comparison of CEC 2024 competition entries on numerical optimization considering accuracy and speed. PPT Presentation, 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).