Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

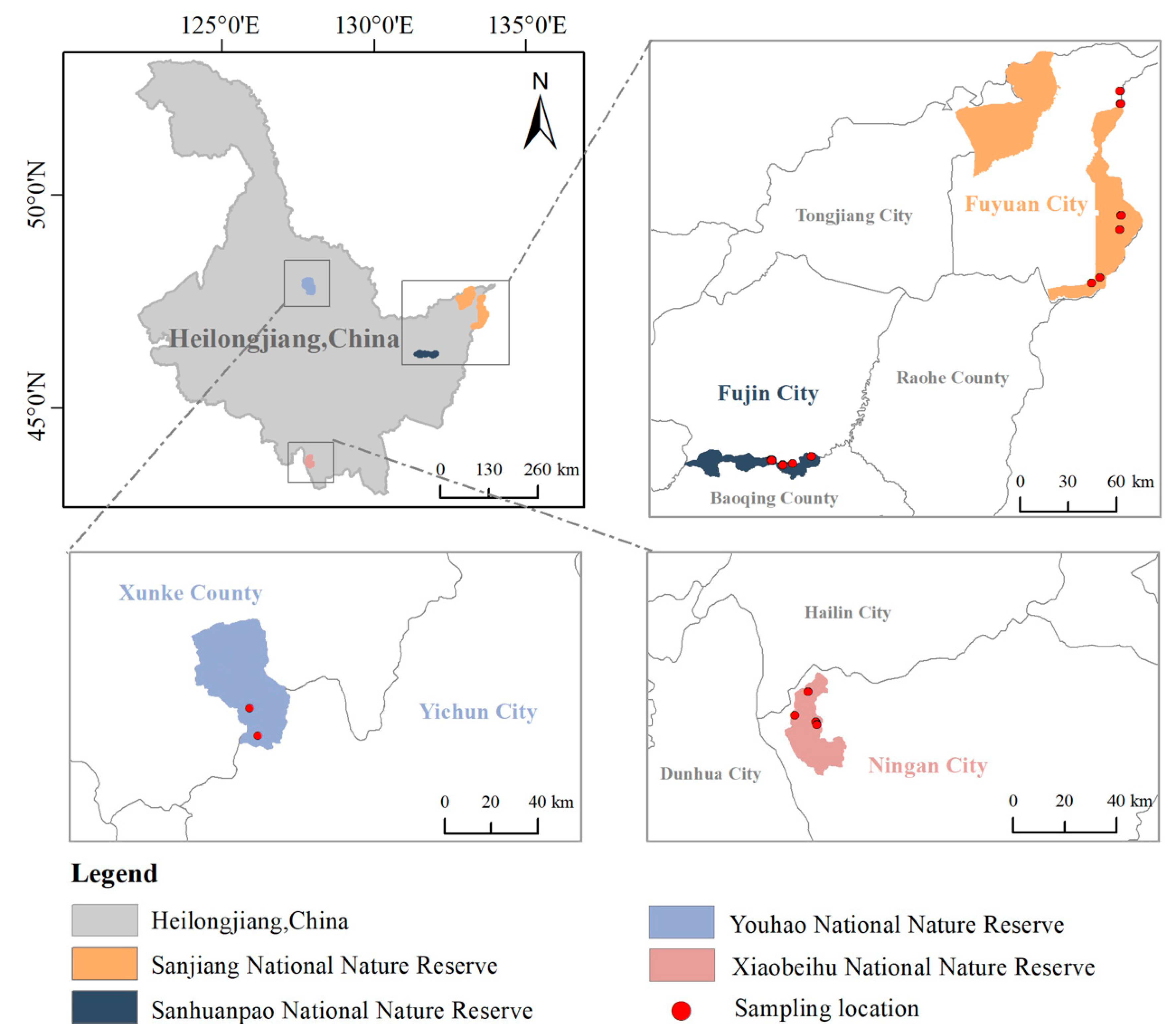

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Methods

2.2.1. Plant Sample Collection and Species Combinations

2.2.2. Leaf Spectra Measurement

2.2.3. Spectral Difference Analysis

2.2.4. Measurement and Analysis of Chemical and Morphological Traits

2.2.5. Impacts of Sample Size and Species Combinations Setup

2.2.6. Prediction of Leaf Traits by Leaf Spectra

3. Results

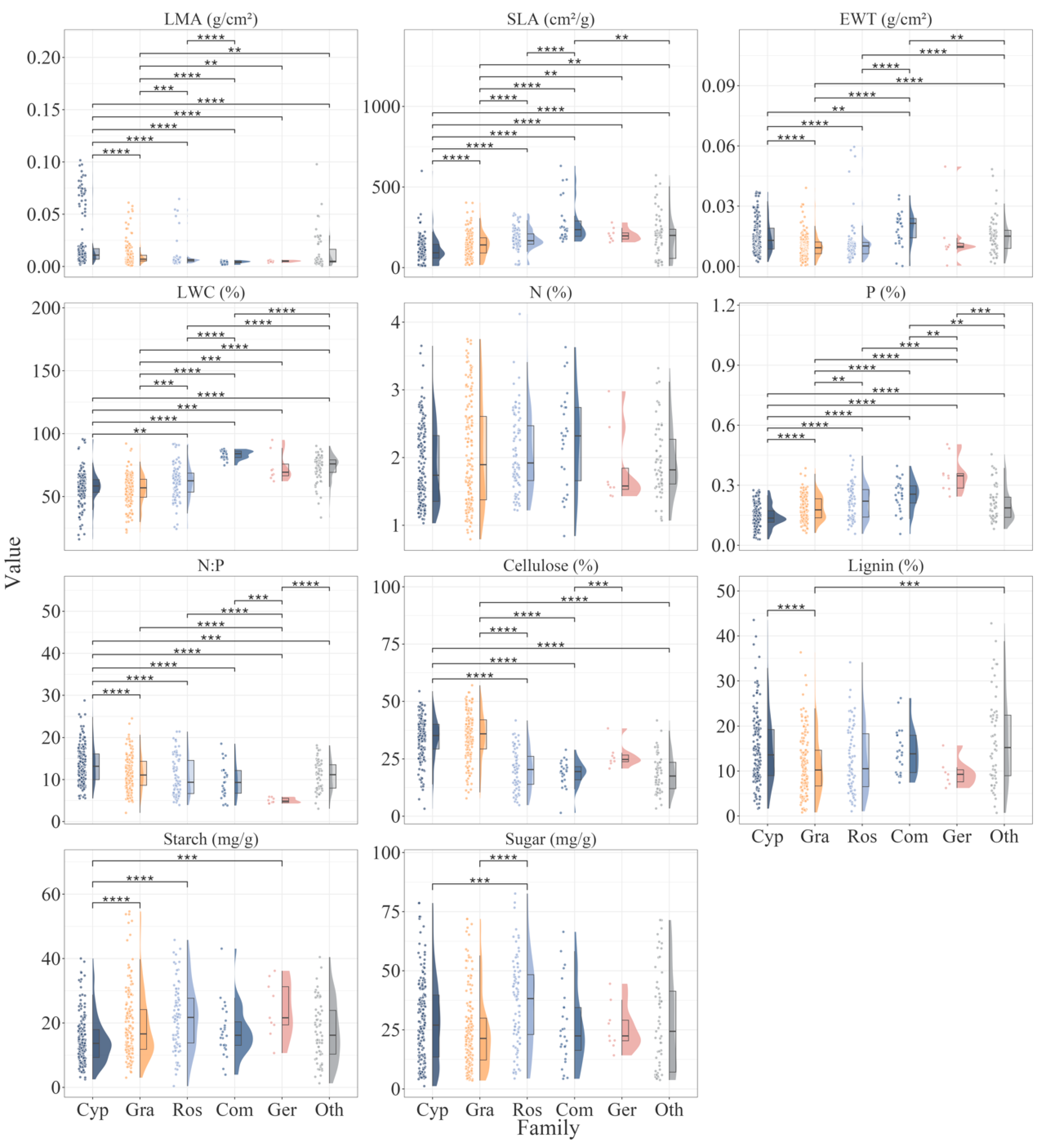

3.1. Traits Variation Among Families

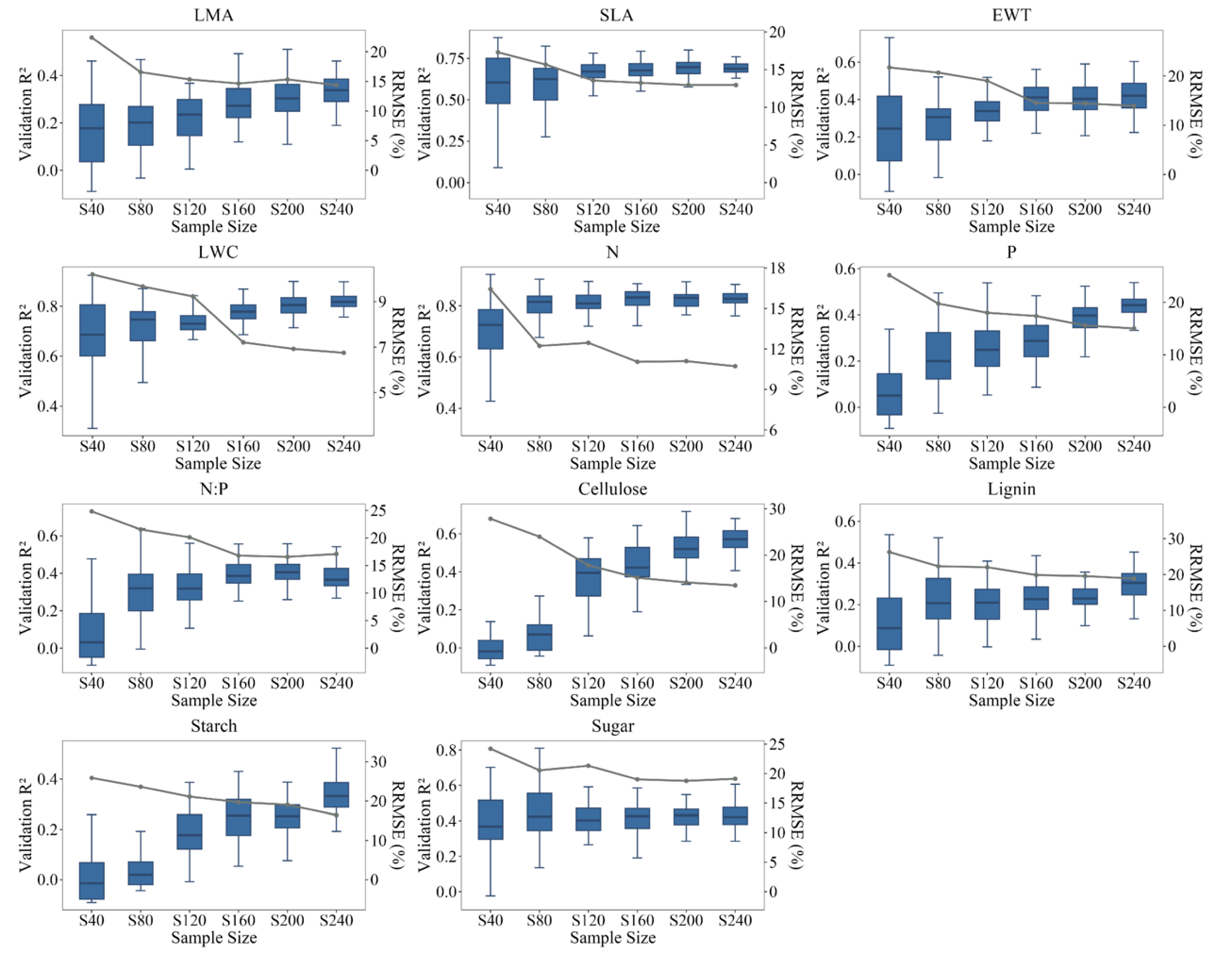

3.2. Model Performance of Different Sample Sizes

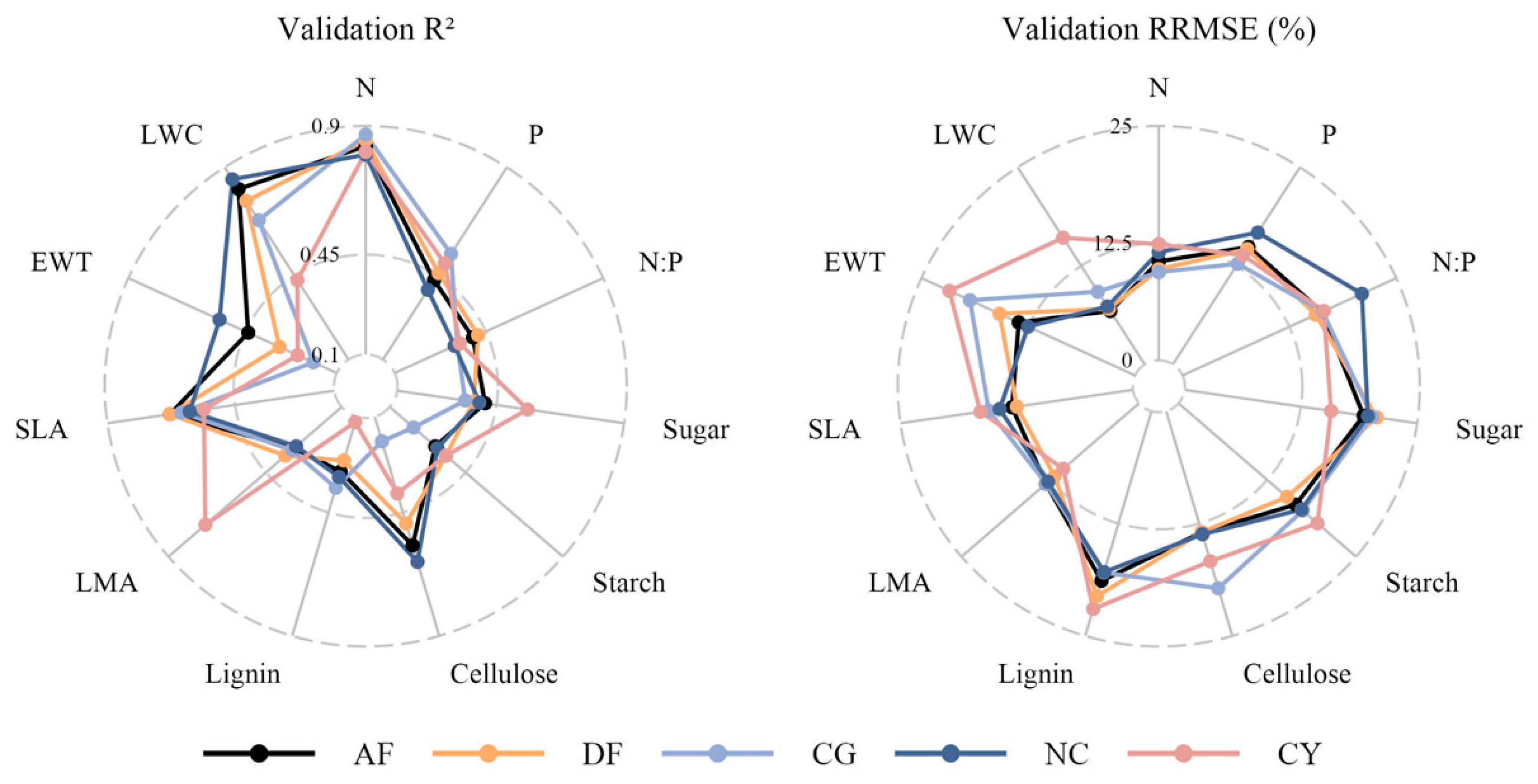

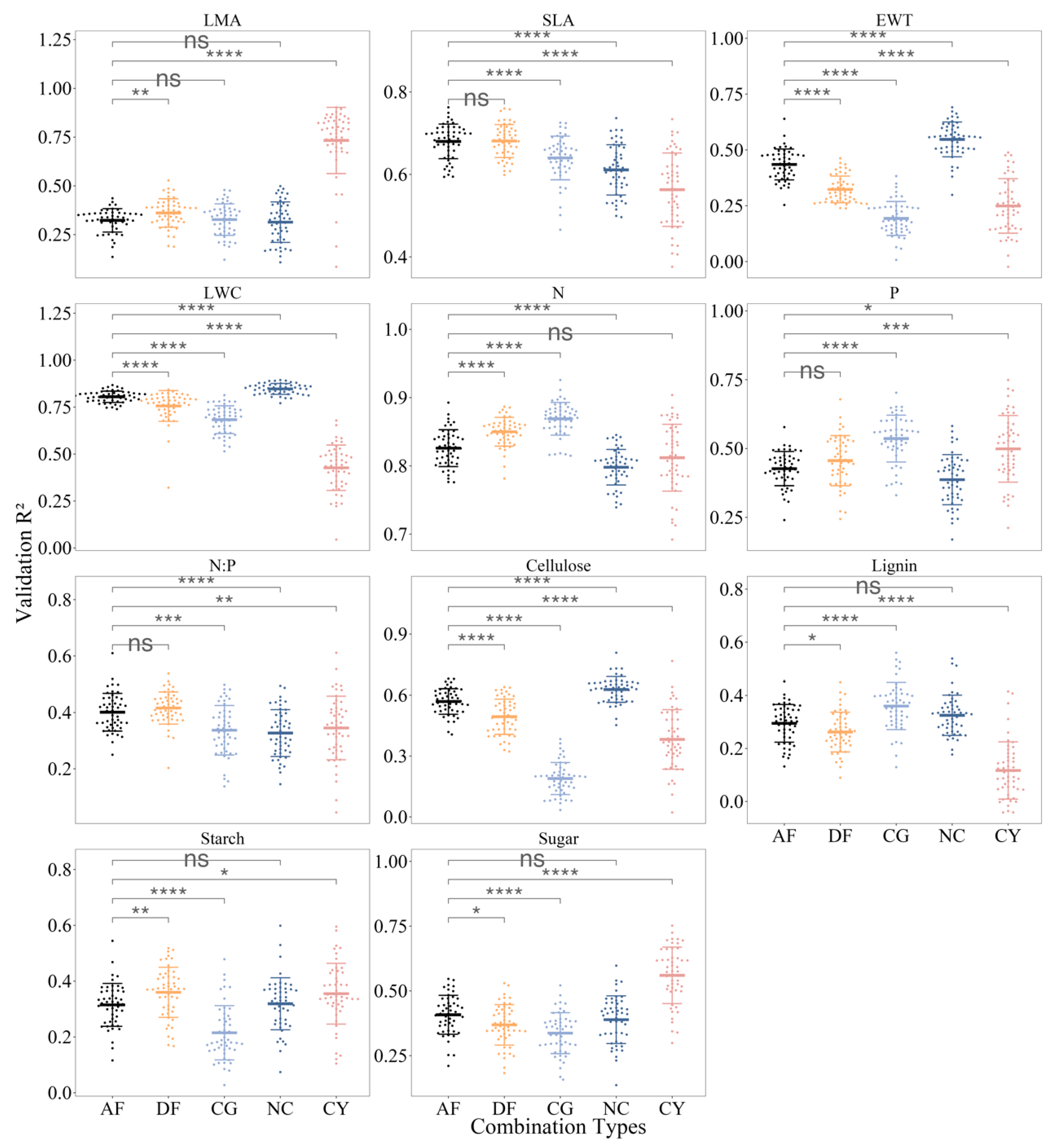

3.3. Model Performance for Different Species Combinations

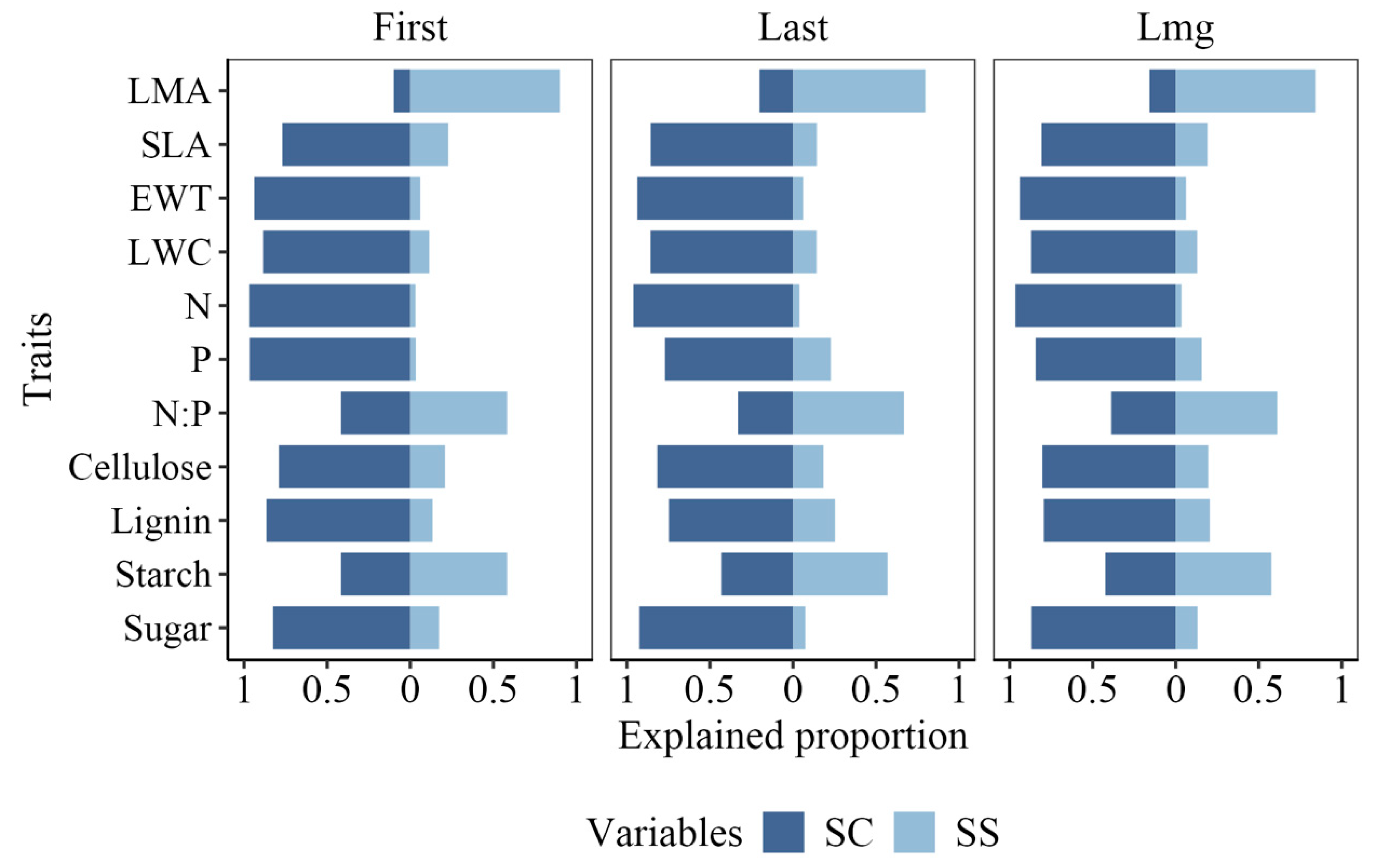

3.4. Variable Importance of PLSR Models for Different Species Combinations

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimal Sample Size for High Predictive Accuracy of PLSR Model

4.2. Species Combinations Played a More Substantial Role in Predicting Most Traits

4.3. N and LWC Can Be More Accurate Predicted by Leaf Spectra of Aquatic Plants

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLSR | Partial Least Squares Regression |

| LWC | Leaf Water Content |

| LA | Leaf Area |

| SLA | Specific Leaf Area |

| EWT | Equivalent Water Thickness |

| LMA | Leaf Mass per Area |

| N | Nitrogen |

| P | Phosphorus |

| LDMC | Leaf Dry Matter Content |

| VIS | Visible light |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared Radiation |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| RFR | Random Forest Regression |

| XBHNNR | Xiaobeihu National Nature Reserve |

| SHPNNR | National Nature Reserve |

| SJNNR | Sanjiang National Nature Reserve |

| YHNNR | Youhao National Nature Reserve |

| S40 | 40 samples |

| S80 | 80 samples |

| S120 | 120 samples |

| S160 | 160 samples |

| S200 | 200 samples |

| S240 | 240 samples |

| AF | All-families |

| DF | Dominant-families |

| NC | Non-Cyperaceae |

| CG | Cyperaceae-Gramineae |

| CY | Cyperaceae |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RRMSE | Relative Root Mean Square Error |

| VIP | Variable Importance of Projections |

References

- Violle, C., et al., Let the concept of traits be functional! Oikos, 2007. 116.

- Butler, E.E., et al., Mapping local and global variability in plant trait distributions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018. 114(51): p. 10937-10946.

- Ferrier, S. and A. Guisan, Spatial modelling of biodiversity at the community level. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2006. 43(3): p. 393-404.

- Clark, C.M., et al., Testing the Link between Functional Diversity and Ecosystem Functioning in a Minnesota Grassland Experiment. Plos One, 2012. 7(12): p. e52821.

- Thomas, H.J.D., et al., Global plant trait relationships extend to the climatic extremes of the tundra biome. Nature Communications, 2020. 11(1): p. 1351.

- Kattge, J., et al., TRY plant trait database – enhanced coverage and open access. Global Change Biology, 2020. 26(1): p. 119-188.

- Michaletz, S.T., et al., The energetic and carbon economic origins of leaf thermoregulation (vol 2, 16129, 2016). Nature Plants, 2016(9): p. 2.

- Poorter, H.N., L.W. U.Poorter, and R. I. J.Villar, Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. The New Phytologist, 2009. 182(4): p. 565.

- Díaz, S., et al., The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature, 2015. 529: p. 167-171.

- Smart, S.M., et al., Leaf dry matter content is better at predicting above-ground net primary production than specific leaf area. Functional Ecology, 2017. 31: p. 1336-1344.

- Thomson, E.R., et al., Multiscale mapping of plant functional groups and plant traits in the High Arctic using field spectroscopy, UAV imagery and Sentinel-2A data. Environmental Research Letters, 2021. 16(5): p. 055006.

- Inge, J., et al., Arctic shrub effects on NDVI, summer albedo and soil shading. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2014. 153: p. 79-89.

- Rogers, A., et al., A roadmap for improving the representation of photosynthesis in Earth system models. New Phytologist, 2017. 213: p. 22-42.

- Fatichi, S., et al., Modelling carbon sources and sinks in terrestrial vegetation. New Phytologist, 2018. 221(2): p. 652-668.

- Rebelo, A.J., et al., Can wetland plant functional groups be spectrally discriminated? Remote Sensing of Environment, 2018. 210: p. 25-34.

- Marín, S.d.T., et al., Spectral signatures of conifer needles mainly depend on their physical traits. Polish journal of ecology, 2016. 64: p. 1-13.

- Jacquemoud, S. and S. Ustin, Leaf Optical Properties. 2019: Cambridge University Press.

- Katja, K., D. Gradinjan, and A. Gaberik, Epiphyton alters the quantity and quality of radiation captured by leaves in submerged macrophytes. Aquatic Botany, 2015. 120(05): p. 229-235.

- Khaled, R.A.H., et al., Variation in leaf traits through seasons and N-availability levels and its consequences for ranking grassland species. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2005. 16(4): p. 391-398.

- Katja, K., et al., Do Reflectance Spectra of Different Plant Stands in Wetland Indicate Species Properties? The Role of Natural and Constructed Wetlands in Nutrient Cycling and Retention on the Landscape, 2015: p. 73-86.

- Lukes, P., et al., Optical properties of leaves and needles for boreal tree species in Europe. Remote Sensing Letters, 2013. 4(7-9): p. 667-676.

- Serbin, S.P., et al., Spectroscopic determination of leaf morphological and biochemical traits for northern temperate and boreal tree species. Ecological Applications, 2014. 24(7): p. 1651-1669.

- Verrelst, J., et al., Optical remote sensing and the retrieval of terrestrial vegetation bio-geophysical properties – A review. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry & Remote Sensing, 2015. 108: p. 273-290.

- Liu, N., et al., Multi-year hyperspectral remote sensing of a comprehensive set of crop foliar nutrients in cranberries. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2023. 205: p. 135-146.

- Feilhauer, H., G.P. Asner, and R.E. Martin, Multi-method ensemble selection of spectral bands related to leaf biochemistry. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2015. 164: p. 57-65.

- Liu, N., et al., Hyperspectral imagery to monitor crop nutrient status within and across growing seasons. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2021. 255.

- Chlus, A. and P.A. Townsend, Characterizing seasonal variation in foliar biochemistry with airborne imaging spectroscopy. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2022. 275: p. 113023.

- Thornley, R.H., et al., Prediction of grassland biodiversity using measures of spectral variance: a meta-analytical review. Remote Sensing, 2023. 15(3): p. 668.

- Kothari, S., et al., Predicting leaf traits across functional groups using reflectance spectroscopy. New Phytologist, 2023. 238(2): p. 549-566.

- Wang, Z., et al., Mapping foliar functional traits and their uncertainties across three years in a grassland experiment. Remote Sensing of Environment: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2019. 221: p. 405-416.

- Schmidtlein, S. and F.E. Fassnacht, The spectral variability hypothesis does not hold across landscapes. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2017. 192(1): p. 114-125.

- Hacker, P.W., et al., Variations in accuracy of leaf functional trait prediction due to spectral mixing. Ecological Indicators, 2022. 136: p. 108687. Ecological Indicators.

- Helsen, K. , et al., Evaluating different methods for retrieving intraspecific leaf trait variation from hyperspectral leaf reflectance. Ecological Indicators 2021,108111.

- Maberly, S.C. and B. Gontero, Trade-offs and Synergies in the Structural and Functional Characteristics of Leaves Photosynthesizing in Aquatic Environments. 2018: p. 307-343.

- Lehnert, L.W., et al., Hyperspectral Data Analysis in R: the hsdar Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 2018. 89(12): p. 1-23.

- Bhattacharyya, A., On a measure of divergence between two statistical populations defined by their probability distributions. Bull.calcutta Math.soc, 1943. 35: p. 99-109.

- Kailath, T., The Divergence and Bhattacharyya Distance Measures in Signal Selection. IEEE Transactions on Communication Technology, 1967. 15(1): p. 52-60.

- Sterher, A.S., et al., Accuracy and limitations for spectroscopic prediction of leaf traits in seasonally dry tropical environments. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2020. 244: p. 111828.

- Sánchez-Azofeifa, G.A., et al., Differences in leaf traits, leaf internal structure, and spectral reflectance between two communities of lianas and trees: Implications for remote sensing in tropical environments. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2009. 113(10): p. 2076-2088.

- Wang, Z., et al., Foliar functional traits from imaging spectroscopy across biomes in eastern North America. The New phytologist, 2020. 228(2): p. 494-511.

- Lindroth, R.L., et al., Effects of genotype and nutrient availability on phytochemistry of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) during leaf senescence. Biochemical Systematics & Ecology, 2002. 30(4): p. 297-307.

- Kruskal, W.H. and W.A. Wallis, Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. JASA: Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1952. 47(269): p. 583-621.

- Yvonne, C. and R.P. Walmsley, Learning and Understanding the Kruskal-Wallis One-Way Analysis-of-Variance-by-Ranks Test for Differences Among Three or More Independent Groups. Physical Therapy, 1997. 77(12): p. 1755-1761.

- Grömping, U., Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo. Journal of statistical software, 2007. 17: p. 1-27.

- Wu, J., et al., Convergence in relationships between leaf traits, spectra and age across diverse canopy environments and two contrasting tropical forests. New Phytologist, 2016. 214: p. 1033-1048.

- Ma, X., et al., Inferring plant functional diversity from space: the potential of Sentinel-2. Remote Sensing of Environment: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2019. 233: p. 111368.

- Svante, W., S. Michael, and E. Lennart, PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemometrics & Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2001. 58(2): p. 109-130.

- Mevik, B.-H., R. Wehrens, and K.H. Liland, pls: Partial Least Squares and Principal Component Regression.R package version 2.8-1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pls. 2013.

- Chen, S., et al., Sparse modeling using orthogonal forward regression with PRESS statistic and regularization. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics. Part B, Cybernetics, 2004. 34(2): p. 898-911.

- Wold, S., PLS for Multivariate Linear Modeling. Chemometric methods in molecular design, 1995: p. 195-218.

- Schweiger, A.K., Spectral field campaigns: planning and data collection. Remote sensing of plant biodiversity, 2020: p. 385-423.

- Kothari, S. and A.K. Schweiger, Plant spectra as integrative measures of plant phenotypes. The Journal of Ecology, 2022.

- Wang, Z., et al., Generality of leaf spectroscopic models for predicting key foliar functional traits across continents: A comparison between physically- and empirically-based approaches. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2023. 293: p. 113614.

- Singh, A., et al., Imaging spectroscopy algorithms for mapping canopy foliar chemical and morphological traits and their uncertainties. Ecological Applications, 2015. 25(8): p. 2180-2197.

- Villa, P., et al., Assessing PROSPECT performance on aquatic plant leaves. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2024. 301: p. 113926.

- Villa, P., et al., Leaf reflectance can surrogate foliar economics better than physiological traits across macrophyte species. Plant Methods, 2021(1).

- Buitrago, M.F., et al., Spectroscopic determination of leaf traits using infrared spectra. International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation, 2018. 69: p. 237-250.

- Sims, D.A. and J.A. Gamon, Estimation of vegetation water content and photosynthetic tissue area from spectral reflectance: a comparison of indices based on liquid water and chlorophyll absorption features. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2003. 84(4): p. 526-537.

- Asner, G.P. and R.E. Martin, Spectral and chemical analysis of tropical forests: Scaling from leaf to canopy levels. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2008. 112(10): p. 3958-3970.

- Shan, Y. Available online: https://figshare.com/s/e3df47ed7b55a57dabb3. 2024.

| XBHNNR | SHPNNR | SJNNR | YHNNR | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyperaceae | 21 | 12 | 94 | 10 | 137 |

| Gramineae | 17 | 44 | 75 | 6 | 142 |

| Geraniaceae | 7 | / | / | / | 7 |

| Compositae | 9 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 18 |

| Rosaceae | 23 | / | 37 | 5 | 65 |

| Others | 6 | 7 | 38 | / | 51 |

| Total | 83 | 66 | 249 | 22 | 420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).