1. Introduction

This manuscript focuses on the core concepts rooted on tensor theory and category theory, integral components of mathematical logic, topology, algebraic geometry, foundations and philosophy. These mathematical disciplines hold significant relevance in elucidating innovative mathematical and scientific ideas. Here, we expand upon foundational tensor and category theory concepts.

In 1975, Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro and Tullio Levi-Civita’s seminal work, “Methodes de Calculs Differentiel Absolute et Leur Application”

1, marked a significant milestone in the development of tensor calculus, now recognized as tensor theory. Over time, diverse investigations have delved into tensor theory’s intersections with mathematical analysis, differential geometry, and topology, including the study by

2, which introduced tensors with maximal symmetries, extending into realms like representation theory, computer science, computational complexity, and algebraic geometry. In this paper, we further advance the concepts established in prior research by extending the tensor framework. Specifically, we introduce the generalized tensor index, a versatile descriptor encompassing various tensor indices. This novel notation, is useful to describe concepts beyond tensors which only have input vectors and their dual vectors. In particular, E. J. Cartan [

3], proposed the triality as an extension of the concept of duality of vector spaces. In this work we extend the concept to the D-ality, which extends further the concepts of dualities, and trialities.

Category theory provides a vantage point akin to a “far-distant observer view” in mathematics [

4], where intricate details fade into obscurity, revealing previously hidden patterns. It beckons us to ponder: How does the direct sum of vector spaces relate to the least common multiple of numbers? What unites free groups, fields of fractions, and discrete topological spaces? Category theory not only explores these inquiries but also unveils profound connections in mathematics and physics that elude closer scrutiny [

5]. This document draws inspiration from modern category theory Definitions [

6] and refines them, ushering in a new perspective. In particular, we redefine categories with brevity, introduce the concept of a signature, and employ graphical representations. These novel viewpoints shed fresh light on categories, akin to how algebra bridges diverse mathematical realms. Moreover, contemporary developments in category theory have given rise to sophisticated notions like

∞-categories,

∞-functors, and

∞-cosmoi [

7,

8], expanding the horizons of mathematical exploration.

The concept of fractional derivatives was introduced by a letter written to Guillaume de l’Hôpital by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1695. It found applications on fractional dynamical systems [

9]. Then it found applications in fractional differential geometrical aspects [

10,

11]. In particular, Calcagni [

12], focused on explaining that the fractional derivative describes a new sub-manifold to a point of an original manifold, which is not the same sub-manifold as the one described by a standard derivative. Fractional calculus was successfully applied to physics [

13] and in particular to quantum mechanics, creating the concepts of fractional schrodinger equation[

14]. In this study we develop further fractional calculus, and we introduce generalised tensors which have the concept of fractional differentials. In extend we develop further tensor calculus and tensor theories.

Furthermore, we establish a linkage between category theory, tensor theory, and set theory, investigating amalgamations of sets, tensors, categories, functors, and their extended counterparts. We will forge categories and functors employing generalized tensors, crafting categorial tensors (tensors with categories as elements) and functorial tensors (tensors with functors as elements).

Category theory and tensor theory, with their rich contemporary and recent applications spanning fields like physics, as evidenced in Feynman diagrams [

15], cosmology, and the study of functors of actions [

16], statistics, and computer science

3, as well as epidemiology

4, underscore their paramount significance. Thus, it is imperative to further cultivate and solidify the foundational concepts within category and tensor theories, encompassing the fundamental notions of categories, functors, tensors, and their multifaceted interplay.

According to the criteria presented in [

19], our manuscript is a description of a good, important, and novel mathematical and philosophical concepts for the following reasons. We describe the criteria and then we give at least one Example from our paper, that renders our work mathematically and philosophically important. The satisfied criteria are the following:

Good mathematical problem solving (e.g., a major breakthrough on an important mathematical problem); This paper solves the problem of how to find further what are the foundations of tensor theory and category theory, by implementing generalised concepts within these theories, and ultimately combining them.

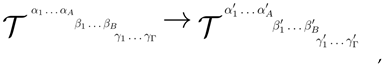

Good mathematical technique (e.g., a masterful use of existing methods or the development of new tools); We use the substitution method, where the simple index is substituted with an index of index and so on. We construct generalised components of the tensors which results to the generalised tensor theory structures. We also use the substitution method to both category theory and tensor theory to create the generic concepts such as tensorial set, setorial tensor, tensorial category, categorial tensor, tensorial functor, and functorial tensor.

Good mathematical insight (e.g., a major conceptual simplification or the realisation of a unifying principle, heuristic, analogy, or theme); In this study, we considered a heuristic argument to construct a generic concepts such as the generalised tensor, as well as the categorial tensor and the tensorial category, but the unifying principle of the method of substitution.

Good mathematical discovery (e.g., the revelation of an unexpected and intriguing new mathematical phenomenon, connection, or counterExample); This study finds an unexpected results such as the generalised tensor, as well as the connections between the concepts of category theory and tensor theory, such as the tensorial category and categorial tensor.

Good mathematical application (e.g., to important problems in physics, engineering, computer science, statistics, etc., or from one field of mathematics to another); This study finds important applications in physics since it connects the concepts of category theory and tensor theory, and their combinations, since both category theory and tensor theory find applications in physics. Furthermore, we expect that the combination of the concepts between the two theories will find further applications in physics.

Rigorous mathematics (with all details correctly and carefully given in full); This paper is mathematical rigorous, since it construct every Definition, Theorems, and proofs in detail.

Beautiful mathematics (e.g., the amazing identities of Ramanujan, results which are easy (and pretty) to state but not to prove); The construction of the Definition of the generalised concepts in tensor theory and category theory, such as functors of functors, generalised tensor, categorial tensor, and tensorial category are easy to state, but difficult to prove, since we need to make several substitution in their individual components.

Elegant mathematics (e.g., Paul Erdos concept of proofs from The Book, achieving a difficult result with a minimum of effort); The construction of the Definition of the generalised concepts in tensor theory and category theory, such as generalised tensor, categorial tensor, and tensorial category, with the minimum effort, i.e., using the simple substitution method makes them easy to prove, and creates a difficult result. We also use the functor of proof, which is a generalisation of the substitution method, in order to prove the Theorem 1.

Creative mathematics (e.g., a radically new and original technique, viewpoint, or species of result); The structure of the Definitions of the generalised concepts in category theory and tensor theory, such as generalised tensor, setorial tensor, and tensorial set shows the creativity of our work. The creativity is also shown by the connection between the category theory and tensor theory with the creation of categorial tensor and tensorial category. We have created the functor of proof.

Useful mathematics (e.g., a lemma or method which will be used repeatedly in future work on the subject); The method of substitution of simple components with more generalised ones was used, and it is going to be used in the future repeatedly. The generalised tensors are used to compress information, more than a standard tensor does. Generalised tensors are capturing aspects of fractional geometry, in a economical way.

Deep mathematics (e.g., a result which is manifestly non-trivial, for instance by capturing a subtle phenomenon beyond the reach of more elementary tools); The creation of the generic concepts of generalised tensor, with and without the use of fractional derivatives, categorial tensor, and tensorial category, as a foundation, as well as the application of connecting category theory and tensor theory show the mathematical deepness of our study.

The structured path of this paper is as follows.

Section 2 introduces fresh insights into tensor theory. In

Section 3, we present the properties of these tensors. In

Section 4, we describe the geometrical interpretation of the general tensors using fractional derivatives in

Section 4, while in

Section 4.1, we describe the geometrical interpretation in some generic way. In

Section 5 we shed light on noteworthy applications stemming from tensor and category theories. Lastly, in

Section 6, we draw our paper to a close.

2. Tensor Theory

In this section, we present a review of the Definition of a tensor, and we develop further some novel Definitions on generalised tensors concepts.

2.1. Standard Tensor Definitions

In this section, we introduce the standard tensor Definitions, that we are going to generalise in the next sessions.

Definition 1.

The generalization of the dual vector is called a tensor and is defined as the multi-linear object that maps distinct vectors and dual vectors to a scalar. A tensor of type is a multilinear representation that maps p dual vectors and q vectors to , and we write

Example 1. A tensor represents a real number vector. Thus can be recognized as a dual vector. A tensor of type is a vector. If ω represents a map of two binary vectors and a vector to a scalar, i.e., , then it is a (1,2) tensor.

Definition 2. The set of all tensors of type (q,p) is called the tensor space of type (q,p) and it is denoted with .

Definition 3.

Let two tensors, and . Then the tensor product is defined as

or

and it is the element of the tensor space, . Thus we write .

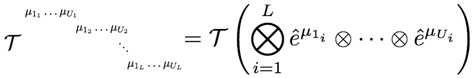

By introducing a basis for the tensors

as

we can write the tensor in the form of components. Therefore, we write

or we can also write

A tensor in a d-dimensional space will have

components. A tensor acts on a set of vectors

and dual vectors

as

Another operation that tensor have is the operation of contraction. A contraction of first order of a tensor of

-rank is a map between a tensor of

-rank to a tensor of

-rank, and we write

Therefore a contraction of k-order of a tensor of

-rank is a map between a tensor of

-rank to a tensor of

-rank, and we write

2.2. Generalisation of a Tensor

We can think of a generalisation of a tensor, by simply introducing a collection of distinct vectors, among which there are vectors and dual vectors, and a map between the collection of vectors to the collection of generic number set. Below we express these ideas in Theorems and proofs.

Theorem 1 (Informa).

Let be a generic generalised tensor, be a generic vector, and be a generic number set, then the generic generalised tensor maps the generic vector to the generic number set, and we write

Proof. To prove Theorem 1, we consider that the (

) rank tensor is a map between the combination of vectors,

V to the real number set,

and we write in functional notation:

By considering the simple functor of substitution

as follows

we have that the generic generalised tensor,

is a map between the generic vector,

to the generic number set,

and we write

□

In other words we can state the previous Theorem in a more detailed way.

Theorem 2.

In accordance with informal Theorem 1, let be a generic generalised tensor, and be a generic number set. Let be a generic vector, denote an element of the generic vector, with generic index, , where i is the index of j which is the index of the indices of k, of the indices, ℓ, for any , and is the lower bound of the lowest index i, while is the maximum bound of the highest index, , and

be a generic vector product operator. If the generic vector is constructed via

then the generic generalised tensor maps the generic vector to the generic number set, and we write

or in short

Proof. Sketch. To prove Theorem 1 , we consider the following. Let (

) rank tensor be a map between the combination of vectors,

V to the real number set,

and we write in functional notation:

or in more detail

where the vector

while the generic vectors is

By considering the simple functor of substitution, as defined in [

20], we write

we have that the generalised tensor,

is a map between the generic vector,

to the generic number set,

and we write

□

Proof. To prove the Theorem 2, in formal mathematical language, we consider the following. The tensor of vectors and their duals is defined, as stated before in

Section 2.1, as

To generalise this concept, we introduce the space between upper, U, and lower, L, indices by assuming that we have the first upper layer of indices,

, then

, and so on up to the lowest layer of indices,

, and we write

where

is the basis of the (

)-rank tensor, which is simply defined as

Therefore, the generalised tensor is simply written as

Note that if this tensor has dimension

d, then it will have

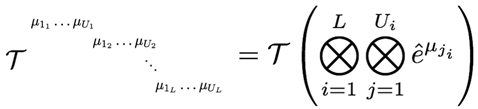

components. In this case, we write the generalised tensor in functor notation as

This means in functor notation that we have the vector

, where the index

specifies each vector for every

j, while the index

i indicates the indexation or how lower is the index from the most upper index. Now we generalise the initial value of the indices,

Considering another layer of generalisation of the generalised tensor, we can think of the generic generalised tensor,

, using the functor notation as

where

is a generic vector, and

denotes the index of the indices,

ℓ, namely a generalised index,

. Now what we need to do is that we can build another layer of generalisation since the previous generic generalised tensor only maps the combination of vectors to the real numbers

. Therefore we can make the generic generalised tensor to map the combination of vectors to the complex numbers,

, or a generic space of numbers named as

, therefore we have that the generic generalised tensor is defined as

At this instance, we can define the generic vector

and in details the generic vector is written as

where

, and

i is the index of

j which is the index of the indices of

k, and

is the lower bound of the lowest index,

i, and

the maximum bound of the highest index

. Consider that the generic vector is defined as

. Therefore, by collecting this information together, it is easy to show that the generic generalised tensor is simply the map between the generic vector to the generic number set, written in generic notation as

□

Remark 1.

The basis vector of this generic generalised tensor is defined as

where denotes the components of basis vector.

2.3. Generic Generalised Tensor in Respect of Indices

We can think of a generalisation of a tensor, by simply introducing a collection of distinct vectors, among which there are vectors and dual vectors, and a map between the collection of vectors to the collection of generic number set. Below we express these ideas in Theorems and proofs.

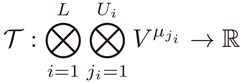

Theorem 3.

In generic notation, the generic generalised tensor, is the tensor which maps the generic vector, , to the generic number set, , and we write

In other words we can state the previous informal Theorem in a more detailed way.

Theorem 4.

In accordance with the informal Theorem 3, the generic generalised tensor, , is the tensor which maps the generic vector, , to the generic number set, , and we write

when the generic vector is defined as

where denotes an element of the generic vector, with generic index, , where i is the index of j which is the index of the indices of k, which is the index of ℓ, for any , where , and is the lower bound of the lower index, i, while, is the bound of the highest index, . We also consider that is the generic tensorial product of generic vector elements .

Proof. The proof of Theorem 3 and Theorem 4 are exactly the same as the proves of the previous Theorems, Theorem 1 and Theorem 2, respectively. The two distinctions are the following

All indices in Theorem 4 belong to the collection of the generic numbers, , instead to the integer number set, .

The generalised tensor, , in the proof of Theorem 3, is substituted by the generic generalised tensor, , in the proof of Theorem 4.

□

3. Properties

In this section we review the concept of the Definition of a tensor using using 1-forms and partial derivatives, and their corresponding transformations. Then we introduce the concept of generalised tensors, using 1-forms, partial derivatives, and fractional partial derivatives. Then we construct the transformation of generalised tensors, using 1-forms, partial derivatives, and fractional partial derivatives. We construct the tensors via the infinitesimal elements and their corresponding derivatives.

3.1. Definition of Standard Tensors

A

-rank tensor is defined as

while a

-rank tensor is defined as

A

-rank tensor is defined as

A

-rank tensor is defined as

3.2. Definition of Generalised Tensors

Let , be indices.

We consider the generalised

-rank tensor as

where we have used the notation of the fractional derivative,

to consider the index,

, which is in between the upper index,

and the lower index,

.

We consider the generalised

-rank tensor as

where

.

We consider the generalised

-rank tensor as

in which tensor there are

ranks. Note that we have partial derivatives in which the denominator of the fraction of the derivative is one more than the number of fractional derivatives that the tensor is defined on.

Note the previous tensor can be describe with

L ranks in a more compact form as follows. Let

are indices. In particular we can built a generalised (

)-rank tensor as

where we have defined

where

i index defines the type of rank, while

j index defines the amount of indices in the specific rank. Note that

i is the index which defines the amount of fractional derivative, i.e., how many times the indices is lowered from the upper index,

. Note also that the power

defines the level of fractional derivative. For Example we have

the one

zth fractional derivative, while

the three

zth fractional derivative.

3.3. Transformation

We introduce the concept of transformations of standard tensors. Then we construct the transformation of generalised tensors, using 1-forms, partial derivatives, and fractional partial derivatives.

3.3.1. Transformation of standard tensors

The

-rank tensor is transformed as

The

-rank tensor is transformed as

A

-rank tensor is transformed as

A

-rank tensor is transformed as

3.4. Transformations of Generalised Tensors

We consider the generalised -rank tensor, the generalised -rank, and the generalised -rank tensor.

This generalised

-rank tensor is transformed as follows:

This

-rank generalised tensor is transformed as

where

The generalised

-rank tensor, defined in Equation (

50), is transformed as

where

The generalised

-rank tensor, defined in Equation (

51), is transformed as

where

3.5. Basic Operations

We introduce the concept of basic operations of standard tensors. Then we construct the basic operations of generalised tensors, using 1-forms, partial derivatives, and fractional partial derivatives.

The basic operations include, tensor product, contraction, raising or lowering an index

3.5.1. Standard Tensor Product

We consider the

-rank tensor, S , and the

-rank tensor, T. Then, the standard tensor product, ⊗, is defined as

3.5.2. Standard Tensor Contraction

We consider the

-rank tensor, S , and the

-rank tensor, T. Then, the standard tensor contraction of tensor, S, is defined as follows. The contraction of the first index is defined as

The contraction up to p-index is defined as

The contraction up to p-up index and q-down index of two tensor is defined as

3.5.3. Standard Tensors’ Lowering and Rising Indices

We consider the

-rank tensor, S , and the

-rank tensor, T. Then, the standard tensor contraction of tensor, S, is defined as follows. The lower the first p upper indices rising the first q lower indices is defined as

The contraction up to p-index is defined as

The contraction up to p-up index and q-down index of two tensor is defined as

3.5.4. Generalised Tensor Contraction

We consider the generalised

- rank tensor, which is given via

Then the contraction of this object from

-rank tensor to a

-rank tensor, is given by

We consider the generalised

-rank. The contraction from generalised

-rank to generalised

-rank is given by

We consider the generalised

-rank tensor. The contraction from generalised

-rank to generalised

-rank is given by

3.5.5. Generalised Tensors’ Lowering and Rising Indices

We can consider the tensor

Then we can consider a standard metric, which is

which the upper indices will increase one layer upwards an index of a tensor, while the lower, will move an index one layer downward for a tensor.

Then we can make the tensor to have the upper index to move to the middle, while the middle to move to the upper layer by the following operation

while we can also have

or

Then we can lower and upper the indices as follows

We consider the

-rank tensor, S , and the

-rank tensor, T. Then, the standard tensor contraction of tensor, S, is defined as follows. The lower the first p upper indices rising the first q lower indices is defined as

The contraction up to p-index is defined as

The contraction up to p-up index and q-down index of two tensor is defined as

4. Geometrical Interpretation of Generalised Tensors Using Fractional Derivatives

In this section, we introduce the geometrical interpretation of the generalised tensors.

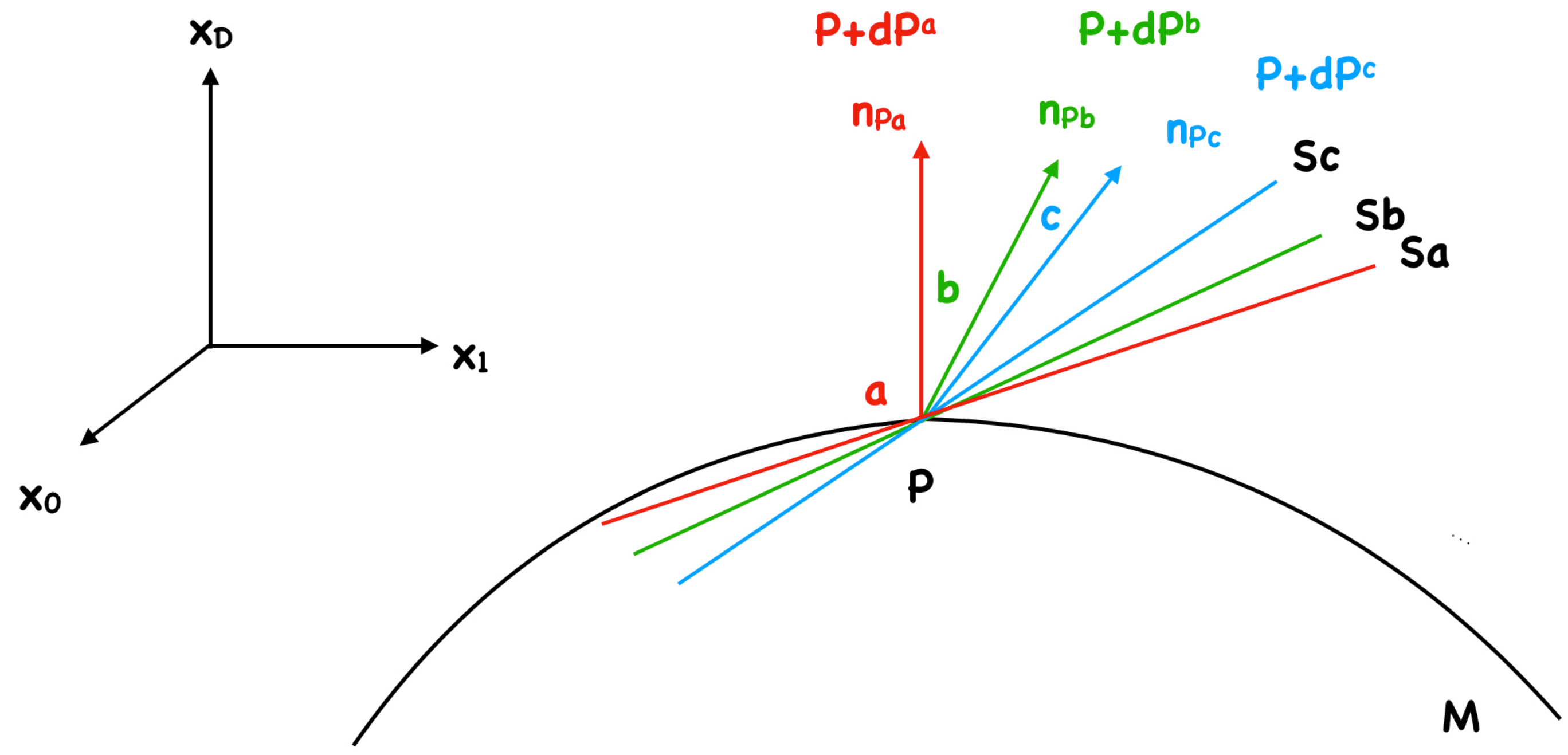

Following [

12], we propose the following geometrical interpretation of fractional derivatives.

Let

be a Manifold, of D-dimensions, with

coordinates. Let

be a point, and

is an infinitesimal space away from this point,

. Then the actual derivative will construct a tangent sub-manifold,

, to this point, according to the operation on any functor,

, that passes from

, to be

Then this derivative will have an associated normal vector which is perpendicular to the tangent sub-manifold, . This normal vector is n.

Now a fractional derivative, of fraction,

a, will have a derivative at point

, as

which will correspond to a Tangent sub-manifold

, with a vector which has some angle,

.

Then we can have a submanifold, which corresponds to a fractional derivative of fraction,

b, or

c and so on. We illustrate this result to

Figure 1.

Following the duality to triality extension [

3], we can extend triality to any D-ality property.

Remark 2. The and -rank tensors conceptualise in tensor formalism the concept of triality of vectors [3]. Note that the and -rank tensors conceptualise in tensor formalism the concept of Ω-ality and Z-ality relations of vectors spaces, which is an extension of the work of triality found in [3].

4.1. Geometrical Interpretation

Let’s consider the following generalised tensor:

This generalised tensor correctly represents a tensor with three indices, where:

- is the upper index.

- is the middle index.

- is the lower index.

4.1.1. Geometrical Interpretation of a Tensor with Three Indices: One Up, One Middle, One Down

To interpret a tensor with three indices one upper, one middle, and one lower. Let’s think about what each index represents geometrically:

1. Traditional Tensors:

- Contravariant Index (Upper Index ): Represents components that transform oppositely to coordinate transformations (basis vectors), such as vectors.

- Covariant Index (Lower Index ): Represents components that transform similarly to coordinate transformations (dual basis vectors), such as covectors or one-forms.

2. “Middle” Index Interpretation:

- The “middle” index suggests a different kind of interaction or relationship that isn’t purely contravariant or covariant in the traditional sense.

In the following subsubsection we represent some possible interpretations.

4.1.2. Geometric Interpretation Possibilities

- Transformation Between Two Different Spaces or Layers:

1) A tensor with three indices can be thought of as an operator that takes input from one vector space and maps it to another while taking into account a transformation or relationship given by the middle index.

2) For Example, if the upper index corresponds to a contravariant vector in one vector space, and the lower index corresponds to a covariant vector in another space, the middle index could represent a mapping or transformation between these two spaces. This is akin to a mixed transformation tensor or an object that mediates between two different layers of geometric structures.

- Multi-Layered Tensor Product or Interaction: The “middle” index could represent an intermediate interaction between the upper and lower indices. For Example, in a physical context, if the upper and lower indices represent different fields or states, the middle index could represent a coupling constant, an intermediate field interaction, or a basis that bridges the contravariant and covariant components. This interpretation might be used in areas like quantum field theory or complex geometrical structures where such intermediate states or interactions are crucial.

- Higher-Order Differential Forms or Geometrical Objects: In differential geometry, higher-order tensors often involve combinations of forms and vectors. The “middle” index might represent an additional layer of structure that combines aspects of both vectors and covectors. In this case, the tensor might represent a higher-order differential form that acts differently depending on the direction of the middle index.

- Curvature-like Structures: In more abstract geometrical frameworks (such as those in advanced differential geometry or complex manifold theory), the “middle” index could denote a type of curvature or torsion that acts upon different tensor components. It might represent how a space curves or twists differently depending on the position or layer represented by the middle index. This can be seen as a generalization of objects like the Riemann curvature tensor.

4.1.3. Conclusion

The tensor with three indices – one upper, one middle, and one lower – could represent a variety of complex geometric or physical structures, depending on the specific nature and transformation properties of the “middle” index. It might denote a transformation between different vector spaces, an intermediate interaction, or even a curvature-like structure that combines and interacts with different geometrical objects or fields. The precise interpretation depends on the context in which this tensor is being used.

5. Applications

Immediate trivial applications of generalised tensor, are similar to the ones of standard tensors. In particular, generalised tensors can be used to compress the information of multiple tensors, much like tensors compress the information of vectors, and much like the vectors compress the informations of scalars. Note also that the structure of information of a vector from scalars, has immediate geometrical implications and interpretations. In the same way the generalised tensors have also geometrical implications and interpretations. However, we will not discuss these concepts in this study, and we will focus on expanding the more abstract applications. In particular, in this section, we construct informal Definitions and their corresponding Examples for combinations of tensors, generalised tensors, generic generalised tensors, categories, functors, and sets.

5.1. Sets and tensors

Basically a tensorial set is the standard application of the Definition of a set which is applied to tensors.

Definition 4. Informally, a tensorial set is a collection of tensors.

Example 2.

Let and be two tensors with distinct ranking and number of elements. Then a tensorial set is defined as

On the other hand, we can define a novel concept, the concept of the setorial tensor.

Definition 5. A setorial tensor, is a tensor with elements sets, using a generic operation between the sets, denoted with o.

Example 3.

Let’s consider an Example of a setorial tensor of (2,2)-rank. Let be the elements of the ith setorial tensors, and j,k indices show the element position of the set in respect of the setorial tensor. These elements are basically distinct sets. Let the operation between these sets be the union operation . Let a setorial tensor be defined as

Let another setorial tensor be defined as

Then, we can define two operation between the two setorial tensors, the summation or sum, and the product operations. The generic summation operation is defined as

where

is the union of set, and .

Furthermore we can define the generic product operation between two setorial tensors. In this case, we consider both the union operation, ∪, and the intersection operation ∩. The generic product operation between two setorial tensors can be defined as

where

are the corresponding union and intersections of the corresponding combinations of sets, .

5.2. Categories and tensors

Basically a tensorial category is the standard application of the Definition of a category which is applied to tensors.

Definition 6. A tensorial category, , is a category with elements which are tensors and a morphism between the tensors which is a functor built with the tensor product.

Example 4.

We can construct the tensorial category which is given by the following signature:

where and are the standard properties of composition, identity, and associativity, while is the collection of objects which objects are tensors, and is the collection of morphisms which is basically the tensorial product.

On the other hand, we can define a novel concept, the concept of categorial tensor.

Definition 7. A categorial tensor, is a tensor with elements which are categories, and a generic morphism between categories, i.e., a functor F.

Example 5.

Since categories are used as entities and functors as map from one such entity to another then a functorial tensor can map a collection of categorial vectors to a category.

where is the target category, is the source category, and the index is just a name in these two cases.

This lead us to the construction of the generalised tensor of categories written as:

which means

. Having this generalised tensor, we can proceed to a more generic generalised tensor.

Now we can build the generic generalised tensor of categories by considering another layer of generalisation, in which we have index of the index of the index repeatedly. We consider the aforementioned index, . This is basically defined as

or

or

where is a vector with category elements, and is the target category.

5.3. Functors and tensors

Basically a tensorial functor is the standard application of the Definition of a functor which is applied to tensors.

Definition 8. A tensorial functor is a functor which is constructed with tensorial product which maps tensor elements from one set to a real number.

Example 6.

Let be a functor and T a tensor. Then, is a tensorial functor if

where

is a simple tensor, as defined by Equation (1).

Another Example of a tensorial functor would be a tensorial functor which is applied to a generic generalised tensor.

Definition 9. A tensorial functor is a functor which is constructed with generic tensorial product which maps tensor elements from one set to a generic number, .

Example 7.

Let be a functor and a generic generalised tensor. Then, is a generic generalised tensorial functor if

where

is a generic generalised tensor, as defined by Equation (41).

On the other hand, we can define a novel concept, the concept of the functorial tensor.

Definition 10. A functorial tensor, is a tensor with elements functors, and a generic morphism between functors, i.e., a functor of functors .

Example 8.

Let be a collection of tensors of ()-rank, with functors as elements, where . Let is a collection of functors, where the upper index shows which tensor these elements belong to, while the two lower indices, denote the position of the functor inside the tensor. We can construct a simple functorial tensor, , of ()-rank, as

and another one as

Then the morphism between the two tensors would be a functor of functors, denoted with , since this objects represents the morphism which maps a functor to another functor. Then the operation between the two tensor is defined as

where

is the elements of the sum of the two functorial tensors. Diagrammatically, Equation (124) this is written also in the form of functor of functors as

for every .

6. Conclusion

In this study, we have delved into the foundational principles of tensor theory and category, inovatively crafting new concepts based on these fundamentals.

Our work extends prior conventions by generalizing the tensor concept, introducing the versatile generalized tensor index that encapsulates diverse tensor indices. After introducing the concept of transformation of tranditional tensors, we constructed the transformation of generalised tensors using fractional derivatives. Furthermore we describe the geometrical interpretation of these generalised tensors. We’ve also forged a deep connection between category theory and tensor theory, exploring the fusion of sets, tensors, categories, functors, and their extensions. Notably, we’ve introduced novel concepts like setorial tensors, functorial tensors, and categorial tensors. These extensions find applications to partial differention and integration.

In conclusion, this study paves the way for fresh perspectives in mathematical analysis, tensor theory, set theory, functor calculus, category theory, mathematical logic, partial differentiation, integration, physics and philosophy.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by the first author. The first draft of the manuscript was written by first author and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank David Skinner, and Spiros Karagiannis for useful discussions, which helped expand the concepts in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Ricci-Curbastro, G.; Hermann, R.; Ricci, M.; Levi-Civita, T. Ricci and Levi-Civita’s Tensor Analysis Paper: Translation, Comments, and Additional Material 1975.

- Conner, A.; Gesmundo, F.; Landsberg, J.M.; Ventura, E. Tensors with maximal symmetries [2]. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1909.09518, [arXiv:math.RT/1909.09518].

- ELIE JOSEPH CARTAN 1869—1951. In <italic>Differential, Geometry</italic>; JAMES, I. (Eds.) ELIE JOSEPH CARTAN 1869—1951. In Differential Geometry; JAMES, I., Ed.; Pergamon, 1962; pp. 331–355. [CrossRef]

- Samuel Eilenberg. ; MacLane, S. General Theory of Natural Equivalences. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1945, 58, 231–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, J.P. Category Theory. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2023 ed.; Zalta, E.N.; Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2023.

- Leinster, T. Basic Category Theory. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1612.09375, [arXiv:math.CT/1612.09375].

- Riehl, E.; Verity, D. Infinity category theory from scratch. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1608.05314, [arXiv:math.CT/1608.05314]. [CrossRef]

- Riehl, E.; Wattal, M. On ∞-cosmoi of bicategories. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2108.11786, [arXiv:math.CT/2108.11786]. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V. Fractional Dynamics; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Lazopoulos, K.A.; Lazopoulos, A.K. Fractional differential geometry of curves and surfaces. Progress in Fractional Differentiation and Applications 2016, 2, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrill-Shepherd, K.; Naber, M. Fractional differential forms. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2001, 42, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, G. Geometry of fractional spaces. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2012, arXiv:hep-th/1106.5787]16, 549–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. 2001; arXiv:math.CA/math/0110241].

- Laskin, N. Fractional Schrodinger equation. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 056108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinzierl, S. Feynman Integrals. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2201.03593, [arXiv:hep-th/2201.03593]. [CrossRef]

- Ntelis, P.; Morris, A. Functors of Actions. Foundations of Physics 2023, 53, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, T.; Klingler, A. The d-separation criterion in Categorical Probability. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2207.05740, [arXiv:math.ST/2207.05740]. [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Li, X.; Libkind, S.; Osgood, N.D.; Redekopp, E. A Categorical Framework for Modeling with Stock and Flow Diagrams. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2211.01290, [arXiv:cs.LO/2211.01290]. [CrossRef]

- Weisgerber, S. Mathematical Progress — On Maddy and Beyond. Philosophia Mathematica 2022, 31, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierros, N. Advancing categories with functors of functors 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).