1. Introduction

How bad would an existential catastrophe be? Many authors argue that, in expectation, it would be astronomically bad because it would prevent enormous numbers of people from living in the long-term future (Bostrom, 2013; Geaves & MacAskill, 2021). As a result, these authors argue that there are vast moral gains to reducing existential risks: the threat of existential catastrophes, which ensure “the premature extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life or the permanent and drastic destruction of its potential for desirable future development” (Bostrom 2013, p. 15). Based on these arguments, existential risk reduction becomes a top priority (or the top priority) for someone who wishes to do the most impartial good they can.

However, prominent arguments in favor of this conclusion generally don’t account for uncertainty about the future’s total

net intrinsic value. That is, these arguments usually don’t consider the potential existence of negative value (such as suffering) in the long-term future, which would reduce the long-term future’s total net value. The astronomical value of existential risk mitigation arises from

longtermism, (roughly) the notion that most of the moral value of our actions lies in their effects on the long-term future (Greaves & MacAskill, 2021). Prominent arguments for longtermism tend to rely on a bifurcated premise claiming that the expected value of the long-term future has a vast magnitude and a robustly positive sign (Beckstead, 2013; Bostrom, 2013; Geaves & MacAskill, 2021). This paper examines this premise’s second prong: How robust is longtermism and existential risk reduction to uncertainty about the future's total

net value? Because this examination explores arguments related to cluelessness and its implications, I will refer to this uncertainty as

axiological cluelessness, (roughly) our

pro tanto cluelessness about the axiological nature of the long-term future—in particular, its net value.

1

In the next section (

Section 2), I survey the landscape of arguments for existential risk reduction to identify their assumptions about the long-term future’s axiological nature, and I provide a

prima facie argument for these assumptions. In

Section 3, I argue for the plausibility of the notion that we’re entirely clueless about humanity’s future state in thousands, millions, or billions of years. In

Section 3, I also argue in favor of placing a high subjective probability (credence) on the notion that we’re somewhat clueless about humanity’s state over these timescales. In

Section 4, I examine how

complete cluelessness about humanity’s long-term future state impacts the expected value and cost-effectiveness of (most) existential risk reduction. In

Section 5, I examine how

limited cluelessness impacts these measures. In

Section 6, I discuss the implications of my findings on longtermism and for the actions of an altruist. Finally, in

Section 7, I summarize my findings and provide my final thoughts.

2. Existential Risk and the Astronomical Value Thesis

Let us begin by examining prominent arguments for existential risk reduction and teasing out their axiological assumptions. Beckstead (2013) uses humanity’s expected lifespan (by his estimate, 10 billion years) to estimate the value of existential risk reduction, writing:

Decreasing the probability of a particular risk by one in a million would result in an additional 10,000 expected years of civilization, and that would be at least 100 times better than making things go twice as well during this period (p. 68).

Similarly, using an estimate of the expected number of future human lives (calculated assuming humanity remains on Earth for one billion years), Bostrom (2013) argues:

Even if we use the most conservative [population estimate], which entirely ignores the possibility of space colonisation and software minds, we find that… the expected value of reducing existential risk by a mere one millionth of one percentage point is at least a hundred times the value of a million human lives (pp. 18–19).

We can see that both Beckstead and Bostrom use proxies for the expected value of humanity’s continued existence: Beckstead uses our species’s expected lifespan, and Bostrom uses the expected future population of humans. However, we might believe these proxies miss an important consideration: the intrinsic value (for the purposes of this paper, welfare) of these humans’ lives, which Beckstead and Bostrom implicitly assume are all net positive. Greaves and MacAskill (2021) recognize this assumption, stating:

Assuming that on average people have lives of significantly positive welfare, according to total utilitarianism… premature human extinction would be astronomically bad… Even if there are ‘only’ 1014 lives to come (as on our restricted estimate), a reduction in near-term risk of extinction by one millionth of one percentage point would be equivalent in value to a million lives saved; on our main estimate of 1024 expected future lives, this becomes ten quadrillion (1016) lives saved (pp. 10–11).

This appears to improve upon the proxies of Beckstead and Bostrom; we now assume the long-term future’s expected value is the number of future humans with significantly positive welfare. Still, we might be missing a relevant consideration: the value of the lives of other moral patients. Greaves and MacAskill’s estimate of the long-term future’s expected value assumes there are no non-human moral patients—whose existence appears plausible and whose welfare may significantly alter the future’s expected value (Browning & Veit, 2022; O’Brien, 2024). Additionally, the estimated value of existential risk reduction proposed by Greaves and MacAskill, Bostrom, and Beckstead rely on the assumption that “on average people have lives of significantly positive value” holding throughout the entire expected duration of humanity’s existence, which they estimate to be 100 million, one billion, and 10 billion years, respectively. However, we might not be confident—clueless even—about the assumption that 100 million, one billion, or 10 billion years from now, “on average people have lives of significantly positive value.”

2

Taking the arguments of Beckstead, Bostrom, Greaves, and MacAskill together, we see that prominent arguments for existential risk mitigation tend to rely on a bifurcated premise that I will call the Astronomical Value Thesis (AVT), which is a claim about the long-term future’s magnitude and a (often implicit) claim about its sign. In this context, “long-term” describes thousands to millions to billions of years. More formally, I will describe the AVT as follows.

Astronomical Value Thesis: (1) the

magnitude of the long-term future’s expected net value is large (to a decision-relevant extent), and (2) the

sign of the long-term future’s expected net value is positive.

3

The AVT certainty appears plausible at first glance—the notion that the future will be better than the present has a compelling prima facie case. Many believe that human well-being has increased dramatically over time, as suggested by various historical trends, including increasing global life expectancy, improvements in qualitative experience (e.g., having access to clean water, abundant food, and insulated housing), and dropping rates of death from lethal infectious diseases among children, gender lifespan inequality, and (perhaps) violence (Pinker, 2011; Roser & Ortiz-Ospina, 2016; Our World in Data, 2024a; Our World in Data, 2024b).

Additionally, many believe that humanity’s morals have been progressing over time. Peter Singer (2011, pp. 96–124) is currently the most prominent philosopher who has proposed a criterion for assessing moral progress: the size of our “moral circle,” which roughly refers to the set of things we consider moral patients. He argues that an expanding moral circle is a component of moral progress because many moral atrocities have been fueled by tendencies to exclude groups from moral consideration (Anthis & Paez, 2021). He further argues our moral circle has expanded from our tribe to all humans, as supported by various sociological and historical examples.

Together, these “outside view” considerations of historical trends form a compelling prima facie case for the second prong of the AVT. Since projecting current trends into the future is often more accurate than chance (and about as good as experts’ forecasts), it appears plausible that we should expect the long-term future to have a positive expected value (from a welfarist consequentialist perspective), seeing that human well-being may have increased over time and that our morals may have progressed over time (Tetlock, 2005). We can also conduct an “inside view” analysis using specific reasoning about the future, independent of historical trends. We might believe in fundamental principles that (directly or indirectly) drive human behavior or societal development, creating an asymmetry of moral or social progress in favor of the impartial good over time.

In short, the prima facie case for the second prong of the AVT argues that historical trends, principles governing human behavior, or both indicate that the long-term future value will be net positive and robustly so. Since the future’s value has an enormous magnitude and a positive sign, this makes existential risk mitigation profoundly important relative to other pursuits, as curbing existential risks will ensure that this astronomically positive value is realized.

I will not confidently deny the AVT, but I have some reservations about it.

4 In this paper, taking a welfarist consequentialist perspective, I will focus on the notion that, even if we assume that the universe’s total net value has increased over time and that humanity has morally progressed over time, we might not be able to make any valid predictions about the expected value of the long-term future. This paper will refer to this problem as

axiological cluelessness, an umbrella term that encompasses a strong form of axiological cluelessness and a weak one.

5 For this paper, they will be defined as follows:

Strong Axiological Cluelessness: We are entirely ignorant about the axiological state of the future thousands, millions, or billions of years from now, leaving us with an uninformative prior and evidential symmetry about the long-term future’s total net value.

Weak Axiological Cluelessness: We are ignorant about the axiological state of the future thousands, millions, or billions of years from now to such an extent that it is wise to account for this uncertainty in our decisions (e.g., by adjusting our expected value calculations).

3. The Perils of Projection

This section argues that strong axiological cluelessness may be plausible and that weak axiological cluelessness appears probable. Disadvantageously to both forms of axiological cluelessness, I assume that, on balance, we believe that the universe’s total net value has been increasing and morality has been progressing over time. Thus, if these trends continue, the long-term future will be astronomically net positive, in expectation. However, I argue that extrapolating any trend over millennia and beyond may not hold. Similarly, general principles behind human behavior or societal development may become invalid at some point in the future. I’ll share some theoretical and empirical arguments to support this conclusion.

On the theoretical side, Karl Popper (1994) proposes a three-step argument. (1) Popper argues that the course of human history is strongly influenced by developments in human knowledge, from scientific truths to political and moral ideas. (2) Popper logically proves that growth in human knowledge is fundamentally impossible to predict. While his proof is lengthy, it can be summarized as follows: any future knowledge that we could know right now is not future knowledge.

6 It’s present knowledge. There’s a fundamental self-reference issue.

7 As a result, his proof indicates that no human or society can predict its own future states of knowledge. (3) Popper concludes that since (1) humanity’s history is largely contingent on its growth in knowledge, and (2) growth in human knowledge is fundamentally unpredictable, we cannot forecast the future course of human history. Popper’s argument suggests that we cannot forecast the net value of society over the long term—or at least that such forecasts are highly limited.

Perhaps we don’t buy Popper’s theoretical argument or its application to the long-term future’s total net value. Still, it seems that, for empirical reasons alone, we (currently) may not have any ability to predict the very distant future’s net value.

Across research fields, forecasts face rapidly declining reliability over time. Granger and Jeon (2007) evaluate a range of quantitative, verifiable

8 long-term forecasts, finding that forecasting even 30 years in the future is extremely difficult due to “major breaks” in trends (pp. 12–13); Armstrong et al. (2014) evaluate long-term predictions of developments in AI, concluding that long-term predictions are unreliable and should indicate greater uncertainty; and Bernard (2020) attempts to quantitatively forecast long-term outcomes, finding that predictions sour once they span ten years.

Focusing on quantitative economic forecasts, we see that projections face more uncertainty than they let on, producing predictions that become untrustworthy after only ten years or less (Christensen et al., 2018; Masayuki, 2019). In fact, the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook only extends its forecasts up to two years into the future (International Monetary Fund, 2024 p. 10).

Even quantitative predictions that closely track science, including population projections and global warming models, don’t extend beyond 80 to 130 years from now (Wuebbles et al., 2017; Paltsev et al., 2021; United Nations, 2022). This is primarily not for lack of concern about the far future; it’s because these predictions become unreliable beyond this point.

The US Global Change Research Program states that “uncertainty in future [global warming] projections is relatively high… These uncertainties increase the further out in time the projections go” (Heyhoe et al., 2017, ch. 4). Hence, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) places low confidence on many of its forecasts for 2100—less than 80 years from now. It even indicates that there is “no robust evidence” for multiple variables in 80-year forecasts (IPCC, 2021 p. 115).

Similarly, in quantitative population projections (which are influenced by fewer crucial variables), the Population Reference Bureau states that “uncertainty in the underlying assumptions grows over time” (Kaneda & Bremner, 2014 p. 2). In fact, “Some demographers argue that population forecasts should not be made over longer horizons than 30 years or so, due to the rapid increase in uncertainty of forecasts beyond this point” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2000 ch. 7). This increasing uncertainty decreases accuracy over time, as historical observations indicate (Ritchie, 2023).

Perhaps the most thorough forecasting analysis comes from Phillip Tetlock, who spent 20 years studying the accuracy of political and economic forecasts of domain experts. Regarding long-term forecasts, he concludes:

[T]here is no evidence that geopolitical or economic forecasters can predict anything ten years out beyond the excruciatingly obvious… These limits on predictability are the predictable results of the butterfly dynamics of nonlinear systems. In my [expert political judgment] research, the accuracy of expert predictions declined toward chance five years out (Tetlock & Gardner, 2015).

But perhaps we think Tetlock’s experts aren’t good enough. Unfortunately, the long-term accuracy of an elite, highly accurate group of forecasters, dubbed “superforecasters,” has yet to be measured (Tetlock et al., 2023). Still, existing research suggests that their accuracy will drop to chance after sufficiently long time horizons (plausibly ones shorter than a century). Forecasts that aggregate the predictions of multiple experts see a notable drop in accuracy when made over 25-year horizons. While superforecasters’ long-term accuracy is expected to be 25% to 40% higher (due to being more accurate than aggregate forecasts over every observed time horizon), there is no indication that their forecasts’ accuracy will decrease more slowly over time (Tetlock & Gardner, 2015; Tetlock et al., 2023). Additionally, forecasts made by superforecasters one year ahead of their resolution have roughly double the error score as those made right before the event (Karvetski, 2021). If this trend roughly holds for horizons beyond one year, we should expect superforecasters to become no better than chance when forecasting over time spans shorter than a century.

Hence, it appears that forecasts, whether technological, economic, scientific, or “super,” should not be expected to hold after hundreds, thousands, millions, or billions of years. Yet, in existing estimates of the future’s expected value, the timespan during which humanity is implicitly forecasted to enjoy (on average) significantly net positive welfare reaches from 100 million to 10 billion years (Newberry, 2021 pp. 11–12; Greaves & MacAskill, 2021 pp. 10–11; Beckstead, 2013 p. 68). This timescale is many orders of magnitude longer than the point at which trustworthy forecasts in various fields become unreliable, giving us a good reason to doubt the key axiological assumption underpinning these expected value calculations—that our average long-term descendant has a life of significantly positive value. By extension, we might also doubt the conclusions of these expected value calculations, even if we assume the existence of trends and principles unfavorable to axiological cluelessness.

9

The very long-run unreliability of our forecasts detailed above plausibly leaves us with strong axiological cluelessness—an uninformative prior and evidential symmetry. The lack of any reliable forecasts with which to understand the axiological distribution of very distant future states plausibly leaves us with no information about this particular distribution, creating an uninformative prior. Similarly, our lack of trustworthy forecasts to sway our credences in favor of one future state over another suggests that we may face evidential symmetry.

4. Strong Axiological Cluelessness

In this section, I investigate the following questions: What happens to the expected value of the long-term future if we subscribe to strong axiological cluelessness? How might this affect the cost-effectiveness and desirability of existential risk mitigation? Please note that this section only considers strong axiological cluelessness—the notion that we’re entirely ignorant about the axiological state of the long-term future. I will discuss weak axiological cluelessness in the next section (

Section 5).

4.1. Expected Value of Humanity’s Continued Existence into the Long-Term Future Under Strong Axiological Cluelessness

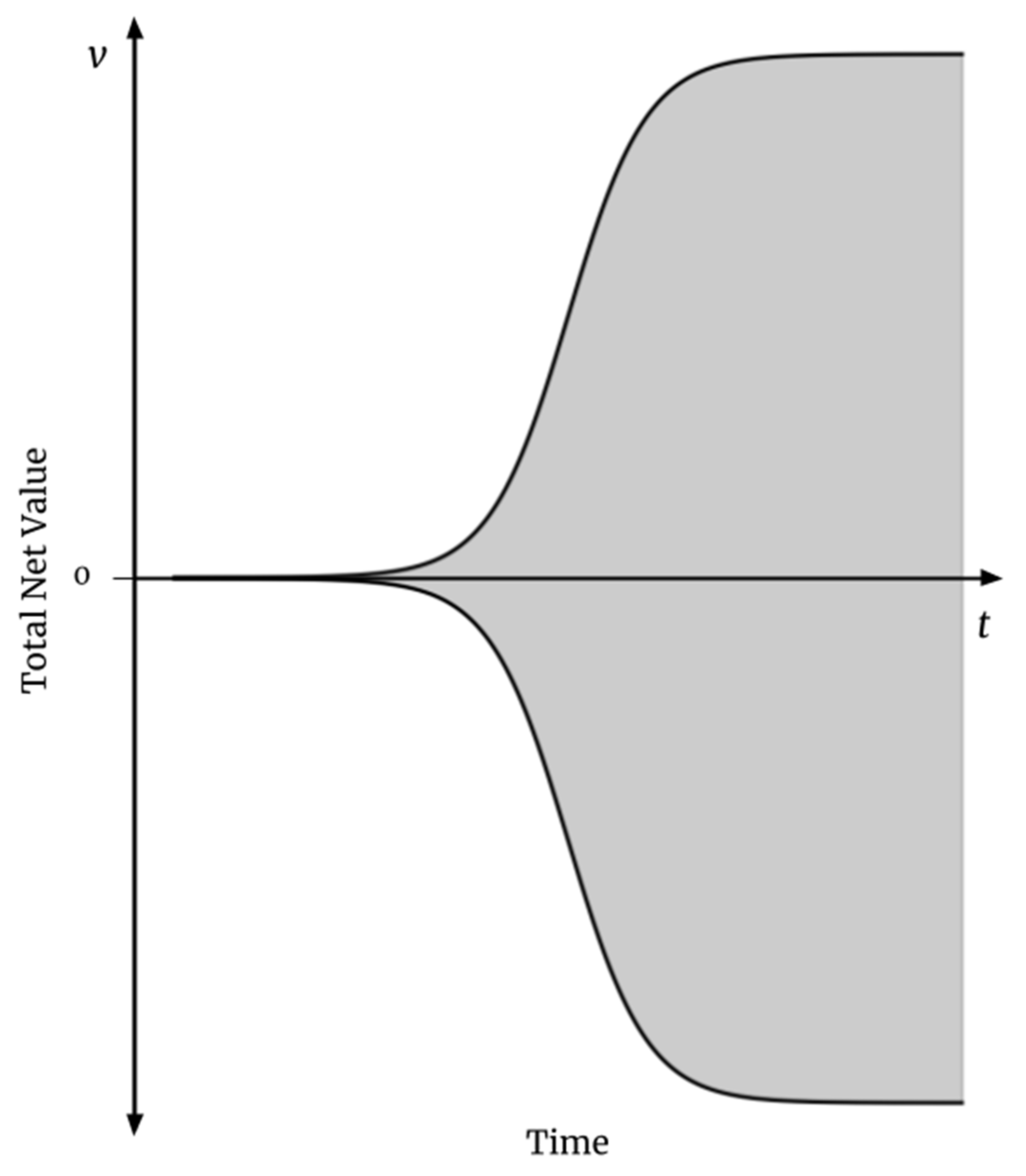

Consider

Figure 1, a simplified illustration that depicts the total value over vast time horizons, assuming logistic growth that leaves the population of moral patients hovering around its carrying capacity. We can think of the shaded region as the landscape of possible axiological outcomes.

The intermediate total net values in the shaded areas may arise in futures with astronomical positive and astronomical negative values (leaving intermediate net values), in futures with positive/negative values with a small magnitude, or in futures where the total net value oscillates up and down over time.

Now let us consider the probability of these possible outcomes. Say you buy the above arguments in favor of strong axiological cluelessness—that is, you believe that, over vast time horizons, we have no ability to predict future events, behaviors, or societal structures, meaning we can’t assign higher probabilities to good futures than we do to bad ones. If you’re rational, according to Bayesian epistemology, you will describe the probability distribution of the long-term future’s total new value as being symmetric around zero. This is because, under these assumptions, we have no reliable information about the long-term future’s total net value, leaving us with an uninformative prior and evidential symmetry. Applying the principle of indifference to this particular case, when examining two possibilities—the future’s total net value being either positive or negative—we should place equal probabilities on both possibilities (50%) because we have no reason to believe futures with positive total net value are more or less likely than futures with negative total net value (Williamson, 2018).

10 Since we’re assuming strong axiological cluelessness, any past trends of social development cannot be assumed to continue. In addition, our complete ignorance about specific future developments prevents us from rationally updating our uninformative, indifferent prior in favor of positive future states.

This brings the

long-term future’s expected value down from 10

28 (or higher) to zero. By extension, ignoring indirect effects on non-human beings, the expected value of decreasing the probability of human extinction (or a permanent reduction in the size of the human population) becomes (very roughly) the number of humans that will die in such an event multiplied by the percentage reduction in the risk of these outcomes.

11

Hence, accepting strong axiological cluelessness prompts expected value estimates that are astronomically lower than those we considered above, which assume that the future only contains positive values. This may pose a challenge to strong longtermism, as I’ll discuss further in

Section 6 (“Implications”). If we find this conclusion absurd, we have two choices. First, we could deny strong axiological cluelessness, claiming that we can, to some extent (I will examine this extent later), make valid forecasts about humanity’s situation in thousands, millions, or billions of years. Alternatively, we could abandon Bayesian epistemology, the principle of indifference, or the application of either to this particular case, viewing this conclusion as a

reductio ad absurdum of one or both of these methods of using probability to quantify our utter ignorance in this case.

To see why we reach these lower expected value estimates and why it may impact our decisions, consider two deals. The first is contingent on the outcome of a fair coin flip. If the coin turns up heads, you get one billion dollars (a value of 10

9). If tails, you pay one billion dollars (a value of -10

9). In this deal, if you’re rational, you won’t place a higher probability on positive values than you’ll place on negative values.

12 In the second deal, a random number from one to ten will be drawn from a hat. If the number is greater than one (a 90% probability), you get ten dollars (a value of 10). If the number is one (a 10% probability), you pay ten dollars (a value of -10).

Calculating the expected value of the first deal, we multiply each value by its probability, yielding 500,000 and -500,000, respectively. Then, adding these values, we end up with an expected value of zero. Using the same process, the expected value of the second deal is 8 dollars.

13 Hence, despite having a value of a small

magnitude, the second deal’s high probability of having a positive

sign makes it preferable to the first deal, which has values of an enormous magnitude but is no more likely to have a positive sign than it is to have a negative sign.

These deals are far from perfect analogies to existential risk reduction and short-term interventions.

14 Still, they illustrate how uncertainty about the sign of the future’s value may influence our conclusions and perhaps challenge longtermism. Let’s explore this further by investigating a more concrete and decision-relevant case: an example of the cost-effectiveness of (most) existential risk reduction.

4.1.1. Objections

Seeking to refute this conclusion, one may object to the principle of indifference, pointing to its paradoxical nature in certain scenarios involving continuous quantities (e.g., see Gillies (2000, p.38-42)). However, assuming strong axiological cluelessness, indifference-based reasoning is rationally applicable to this particular case (even if not in general) because, while the long-term future’s total net value is a continuous quantity, any possible long-term future state has a precise, equally plausible counterpart (for instance, every utopia has an equally plausible dystopia)). It is intuitive to place equal credence in precise-counterpart cases such as this. This intuitive conclusion holds despite the paradoxical tendencies of a completely general principle of indifference (Greaves, 2016).

One might object that our lived experience indicates that human lives are seldom net-negative—suffering extreme and frequent enough to make one better off never having been born is rare.

15 There may be a fundamental characteristic of our biology that prevents humans from living in such abject suffering. This would not simply be a trend, meaning we can expect it to continue into the long-term, and our probability distribution over possible future states should be centered at a total net value greater than zero.

I have a few thoughts on this subject, although I believe it remains unsettled. First, the biological predilection for net-positive lives stated here assumes hedonism, which we might not believe fully encapsulates welfare (see, e.g., Feldman, 2004; Moore, 2019). Intuitively, it appears less plausible that a similar asymmetry favoring net-positive welfare exists for other accounts of welfare, such as preference satisfaction. Second, we may be less confident about the welfare of potentially digital descendants and that of far future non-human animals, both of which, in expectation, may exist in significant numbers relative to the biological human population (Browning & Veit, 2022; O’Brien, 2024; Bostrom, 2013; Bostrom, 2014; Greaves & MacAskill, 2021 p. 9; Newberry, 2021 p. 11–12). Regarding non-human animals, the prevailing view in welfare biology is that wild animals likely experience more suffering than happiness (Ng, 1995; Horta, 2012; Horta, 2015; Tomasik, 2015a; Johannsen, 2020; Faria, 2022), and many argue that most farmed animals also have net-negative lives (see, e.g., Bramble & Fischer, 2015; Plant, 2022; Singer, 2023). Third, evolutionary psychology has identified various ways that certain negative subjective experiences may be favored by natural selection, which suggests that humans aren’t necessarily wired to enjoy net-positive lives and could evolve more frequent or intense negative subjective experiences over time (Lazarus, 1991; Marks & Nesse, 1994; Ekman & Davidson, 1994; Nesse, 2000; Nesse & Ellsworth, 2009; Hagen, 2011; Rantala & Luoto, 2022). Finally, it appears plausible that risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks) are more likely than we expect, as these threats may present themselves in many ways, and our expectations about the future may be influenced by optimism bias and directionally motivated reasoning (Tomasik, 2015b; Althaus & Gloor, 2016). Ultimately, even if human lives are scarcely net negative, regardless of their conditions, it appears plausible that we should feel uncertain—or even clueless—that this will result in a future with a robustly net positive value.

4.2. Cost-Effectiveness of (most) Existential Risk Reduction Under Strong Axiological Cluelessness

One of the most-cited discussions of biological existential risk (biorisk) mitigation comes from Piers Millett and Andrew Snyder-Beattie (2017). As seen in

Table 1, under the models Millett and Snyder-Beattie propose, biorisk reduction appears cost-effective; it has a lower cost per life-year saved than

$100—the estimated cost per life-year saved of charity evaluator GiveWell’s top global health charities—on all estimates but one (GiveWell, 2024).

Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s methodology has been critiqued before (Thorstad, forthcoming). But it remains to be said how axiological cluelessness affects its conclusions. Millett and Snyder-Beattie examine a

$250 billion investment in strengthening global healthcare infrastructure to meet international standards for this century, expecting this to reduce the existential risk this century by 1%. They estimate the cost-effectiveness of this investment with the equation

C/

NLR, where

C is the

$250 billion cost,

N is the number of expected biological catastrophes per century without the intervention (with upper and lower bounds estimated using three models),

L is the estimated number of life-years lost in such a catastrophe, 10

16, all of which are implicitly assumed to be net positive, and

R is the reduction in risk, bringing

N down to 0.99

N (a 1% relative risk reduction).

16

If we face axiological cluelessness,

L decreases. Ignoring indirect effects, assuming strong axiological cluelessness, and assuming that all currently living humans have net-positive lives,

L becomes 4 ✕ 10

11 (using the current human population of eight billion alongside Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s assumption that reducing non-extinction biorisks saves 50 life-years per life). The results are shown in

Table 2.

This increases the cost per life-year saved of biorisk reduction by orders of magnitude, now failing to match that of GiveWell’s top charities ($100) on all estimates but one, often being over ten times less cost-effective than GiveWell's top global health recommendations. It appears that existential risk reduction (aside from the smaller class of s-risk reduction) is not a particularly cost-effective endeavor compared to highly cost-effective global health charities if we accept strong axiological cluelessness.

To recap, in this section, we’ve seen that subscribing to strong axiological cluelessness, the notion that we are entirely ignorant about the total net value of the future over sufficiently long time horizons, may have important ramifications: it decreases the expected value of humanity’s continued existence into the long-term future to zero, and it makes (most) existential risk reduction less cost-effective than certain alternative interventions focused on improving the near-term future.

5. What If I Don’t Buy Strong Axiological Cluelessness?

But perhaps you don’t buy the argument in

Section 3 for strong axiological cluelessness. In other words, you think we’re not entirely ignorant about humanity’s distant-future state and, therefore, we’re able to place different probabilities on net-positive long-term future states than we place on net-negative ones. In this case, to reach the AVT and its cost-effectiveness stipulations, how high must we believe the probabilities of good future states of affairs are relative to bad ones? I’ll first theoretically model the expected value of the long-term future, accounting for uncertainty about its total net value, to determine the probability we must place on the long-term future being net positive to reach the AVT. Then, I’ll consider a more practical, decision-relevant case by returning to the Millet & Snyder-Beattie biorisk reduction cost-effectiveness model and determining the probability we must place on the long-term future being net positive for (most) existential risk mitigation to appear more cost-effective than GiveWell’s top charities.

5.1. Expected Value of Humanity’s Continued Existence into the Axiologically Uncertain Long-Term Future

In this subsection, I explore how likely we need to believe net-positive futures are for the long-term future to have astronomical value using two probability distributions. My model indicates that, for large future population sizes, only a slight increase in the probability of net-positive futures is needed to achieve astronomical value, but for smaller future populations, this probability must be much higher. This suggests that longtermism is sensitive to our estimates of future populations and the extent of our uncertainty about the future.

I consider two models for the future’s total net value. Under these models, I calculate the total probability of the future’s total net value being greater than or equal to zero required for the future’s expected value to be greater than or equal to 1014, conditional on the future population size reaching the estimates below. I’ll call this the “probability needed for astronomical value.” While this choice is somewhat arbitrary, I use this number because it’s the lowest estimate of the future’s expected value used to support the astronomical value of existential risk reduction (Greaves & MacAskill, 2021).

For simplicity and to reduce computational intensity, I consider 100 possible long-term futures. In the first, 100% of the population of moral patients enjoys net-positive lives; in the second, 99% of lives are net positive, while 1% are net negative; and so on, until we reach an astronomically disvaluable long-term future in which 100% of lives are net negative. Then, I construct two different probability distributions over these possible futures: one with a constant probability distribution over total net value, and one with a normal probability distribution (bell curve) that favors intermediate total net values (meaning the highest probability is a total net value of zero), as seen in Figure 2.

Next, I evaluate how much we must shift each of these probability distributions in favor of more preferable futures to reach an astronomical total net expected value. For the constant probability distribution, I increase the total probability of futures with a total net value greater than or equal to zero (which I’ll call p) and spread this uniformly over the distribution, in turn uniformly reducing the probabilities of futures with a total net value less than or equal to zero (which sum to 1 – p).

For each probability distribution, after shifting it in favor of positive total net values until we reach astronomical expected value estimates, I take note of

p, representing the total probability of the future having a total net value greater than zero required for the AVT. This is because, when dealing with these astronomical numbers, the aggregate probability of total net values greater or less than zero (as opposed to individual probabilities) dominates the expected value calculation. The results are shown in

Table 3.

No matter what probability we assign to net-positive futures, astronomical value (as defined above) is unattainable under the long-term population projections of Geruso & Spears (2023). For the other population estimates, as mentioned above, the aggregate probability of states with a total net value greater or less than zero dominates the expected value calculations. As a result, both probability distributions agree on the probability of net-positive futures needed for astronomical value, which ranges from 50.0000000000001% to 100%, depending on the future population. This range of probabilities suggests that accounting for our uncertainty about the future’s axiological state makes longtermism somewhat more sensitive to the expected future population than it first appears to be.

17

If we deny strong axiological cluelessness and believe that humanity’s expected future population exceeds some 10

16 to 10

18 people, longtermism appears fairly robust to axiological cluelessness (i.e., we only have to believe that net-positive futures are very slightly more likely than negative ones). On the other hand, if we believe the future’s expected population is smaller, axiological cluelessness may significantly lower the expected value of the long-term future, lest we believe the future is highly likely to have a net positive total value—which, as I argued in

Section 3, appears implausible, since we’re almost certainly at least somewhat clueless about the state of society thousands, millions, or billions of years in the future.

5.2. Cost-Effectiveness of (Most) Existential Risk Reduction Under Weak Axiological Cluelessness

How does this affect the cost-effectiveness estimates we saw above? Indecisively seeking an answer, I calculate (within an order of magnitude) the probability we must place on the long-term future being net positive for existential risk mitigation to be more cost-effective than GiveWell’s top charities.

Adhering closely to my methodology in

Section 5.1, I consider 100 possible futures. In the first, 100% of the life-years saved by the prevention of biological extinction (10

16, in line with Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s estimate) are net positive; in the second, 99% of life-years saved are net positive, while 1% are net negative; and so on, until we reach a future where 100% of life-years saved are net negative. Hence, in this modified model,

L is the expected net-positive life years saved. Then, I construct a constant probability distribution over these futures.

18> Finally, I gradually increase the aggregate probability of futures with more net-positive life-years saved than negative ones, spreading this uniformly over the distribution (thereby decreasing the probability of futures with more net-negative life-years saved than positive ones).

I stop this process once biorisk reduction becomes more cost-effective than GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness estimates of its top global health charities (

$100 per life-year saved) on the majority (four out of six) of the estimates produced by the models of Millett and Snyder-Beattie. Since Millett and Snyder-Beattie use only one estimate of the number of life years in the future, I estimate only one probability: we must place a 50.1% probability on the expected long-term life years saved by biorisk reduction being more net positive than net negative for biorisk reduction to perhaps be more cost-effective than GiveWell’s top charity recommendations.

19 These cost-effectiveness estimates are shown in

Table 4, alongside the original estimates of Millett and Snyder-Beattie and the estimates from

Section 4.2, calculated assuming strong axiological cluelessness (a 50% probability on the notion that biorisk reduction, in the long-term, saves more net positive life years than net-negative ones).

It’s worth noting the limitations of these estimates. First, the weakly axiologically clueless estimates use Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s estimated expected future number of human life-years (10

16). As we saw in

Section 5.1, the expected value of (most) existential risk mitigation (and thereby its cost-effectiveness) appears quite sensitive to the expected number of future lives (or life-years). Second, Thorstad (forthcoming) proposes some plausible reasons why Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s model overestimates the cost-effectiveness of biorisk reduction. Finally, the model ignores indirect effects (such as those on non-human beings).

With those limitations in mind, if we deny strong axiological cluelessness, (most) existential risk reduction appears robust to uncertainty about the net value of these life years. We must believe that it’s only 0.1% more likely that reducing biorisk saves mostly net-positive lives (in expectation) than the opposite for doing so to be more cost-effective than GiveWell’s top global health charities.

To recap this section, I first calculated the expected value of the long-term future accounting for uncertainty about its total net value, finding that the probability of net-positive futures needed for its value to reach 1014 ranges from 50.00000001% to 100%. This suggests that the expected value of (most) existential risk mitigation is fairly sensitive to the expected future population: if we believe the future’s expected population exceeds some 1018, the expected value of (most) existential risk reduction appears robust to weak axiological cluelessness; but if we believe the expected future population is smaller, weak axiological cluelessness may significantly reduce the expected value of (most) existential risk reduction. Second, I estimated the cost-effectiveness of reducing biological extinction risk (biorisk) under uncertainty about the net value of future lives, finding that the probability of net-positive futures needed for biorisk reduction’s cost-effectiveness to be higher than GiveWell’s top charities is 50.1%. This indicates that (most) existential risk reduction is quite robust to uncertainty about the future’s total net value—if we ignore indirect effects, believe that, in expectation, the future holds 1016 human life-years, and don’t alter mathematical assumptions that have been challenged by Thorstad (forthcoming).

6. Implications

How might all of this inform the actions of an altruist? How does it affect longtermism? In

Section 4, we saw that strong axiological cluelessness brings the expected value of humanity’s continued existence into the long-term future from 10

24 (or higher) down to zero. This makes preventing most existential risks less desirable relative to other means of saving lives. Let us consider how this might affect longtermism. The principal argument for strong longtermism relies on the intermediate claim that:

The highest far-future ex ante benefits that are attainable without net near-future harm are many times greater than the highest attainable near-future ex ante benefits (Greaves and MacAskill, 2021 p. 4).

Section 4 suggests that strong axiological cluelessness may pose a challenge to strong longtermism. This is because ways of improving the distant future other than existential risk reduction may be more difficult to identify or make very long-lasting progress on, as illustrated by Tarsney (2023a). Indeed, Greaves and MacAskill anticipate this issue, writing:

The example of [artificial superintelligence] risk also ensures that our argument goes through even if, in expectation, the continuation of civilisation into the future would be bad (Althaus and Gloor 2018; Arrhenius and Bykvist 1995: ch. 3; Benatar 2006). If this were true, then reducing the risk of human extinction would no longer be a good thing, in expectation. But in the AI lock-in scenarios we have considered, there will be a long-lasting civilisation either way. By working on AI safety and policy, we aim to make the trajectory of that civilisation better, whether or not it starts out already ‘better than nothing’ (2021 p. 18).

While the particular argument Greaves and MacAskill propose is reasonably robust to axiological cluelessness, there are two things worth highlighting. First, as mentioned above, it appears plausible that methods of improving the long-term future other than existential risk reduction are less tractable than improving the near-term (Tarsney, 2023a). Second, it’s important to highlight the conditions under which strong longtermism holds if we assume strong axiological cluelessness. Specifically, if the expected value of the future is zero or lower, then only the risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks) in the set of existential risks, such as “the AI lock-in scenarios,” are astronomically important, not other existential risk mitigation.

20 Additionally, it appears plausible that restricting the astronomical value of existential risk mitigation to s-risks (which we may reduce by small percentages relative to other existential risks) increases the extent to which longtermism relies on fanaticism, the idea that we should choose to maximize expected value, even if this is driven by a tiny probability of astronomical value (Wilkinson, 2022; Russell, 2023; Beckstead & Thomas, 2023; Tarsney, 2023a; Tarsney, 2023b).

Section 5 indicates that these challenges to longtermism may hold under weak axiological cluelessness, depending on three things: the expected future population; the extent to which we believe we are clueless about humanity’s situation in thousands, millions, or billions of years; and mathematical assumptions identified by Thorstad (forthcoming). This suggests that reducing our uncertainty about the expected future population size would be relevant to altruistic decisions.

7. Conclusion

This paper examined the robustness of longtermism and existential risk reduction to uncertainty about the future's total net intrinsic value. The Astronomical Value Thesis (AVT), which underpins many arguments for longtermism existential risk mitigation, asserts that the long-term future's expected net value is both enormous in magnitude and positive in sign. However, this thesis is sensitive to what I call axiological cluelessness: (roughly) our pro tanto ignorance about the long-term future's net value.

Using theoretical reasoning about trends and chaotic systems alongside empirical evidence about the lifespan of reliable forecasts, I presented an argument for two forms of axiological cluelessness: one strong, one weak.

Strong axiological cluelessness claims that we are entirely ignorant about the long-term future's net value, which indicates that the expected value of humanity’s long-term future is zero. If we assume strong axiological cluelessness, I find that the cost-effectiveness of most existential risk reduction is significantly reduced, often being orders of magnitude more expensive than GiveWell’s top global health charities.

Under weak axiological cluelessness, where we assume some degree of long-term future predictability, the expected value and cost-effectiveness of existential risk reduction appear sensitive to our assumptions about the expected future population and the likelihood of net-positive futures. If we believe that the expected future population is astronomically large (above roughly 1016 to 1018 lives), longtermism remains robust; however, if the expected future population is smaller, the probability we place on the long-term future’s value being net positive seems to become quite critical.

This has multiple implications. First, it suggests that our prioritization of existential risk reduction relative to other interventions should account for axiological cluelessness. Second, it indicates that reducing risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks) that overlap with existential risks offers far more value, in expectation, than other existential risk reduction. However, if we believe that such risks are more difficult to reduce than other existential risks, axiological cluelessness may increase the extent to which longtermism relies on tiny probabilities of astronomical payoffs. Finally, this paper suggests a need for further research and debate on the validity of the AVT and the extent of our axiological cluelessness, as these considerations are directly relevant to our priorities and altruism.

In conclusion, I believe the axiological assumptions of longtermism and existential risk reduction require some adaptation in light of our epistemic limitations about the long-term future’s net value—or that compelling arguments against the existence of such epistemic limitations are in order. It is unclear exactly what conclusion these adaptations or arguments will lead us to, making them all the more worthwhile.

References

- Althaus, David, and Gloor, Lukas. 2016. “Reducing risks of astronomical suffering: A neglected priority.” Center on Long-Term Risk. Available online: https://longtermrisk.org/reducing-risks-of-astronomical-suffering-a-neglected-priority/.

- Anthis, Jacy Reese and Paez, Eze. 2021. “Moral circle expansion: A promising strategy to impact the far future.” Futures.

- Armstrong et al. 2014. “The errors, insights and lessons of famous AI predictions – and what they mean for the future” Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 26:317-342.

- Beckstead, Nicholas. 2013. On the overwhelming importance of shaping the far future. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University. Available online: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/40469/PDF/1/play/.

- Beckstead, Nick and Thomas, Teruji. 2023. “A paradox for tiny probabilities and enormous values.” Noûs 58:431–455.

- Bernard, D.R. 2020. “Estimating long-term treatment effects without long-term outcome data.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 11-2020.

- Bostrom, Nick. 2013. “Existential risk prevention as a global priority.” Global Policy 4:15–31.

- —. 2014. Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Bramble, Ben and Fischer, Bob. 2015. The moral complexities of eating meat. Oxford University Press.

- Browning, H. & Veit, W. (2022). “Longtermism and animals.” Preprint.

- Christensen et al. 2018. “Uncertainty in forecasts of long-run economic growth.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:5409–5414.

- Ekman, Paul. and Davidson, Richard J. 1994. The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press.

- Faria, Catia. 2022. Animal ethics in the wild: Wild animal suffering and intervention in nature. Cambridge University Press.

- Feldman, Fred. 2004. “Classic objections to hedonism.” In Pleasure and the good life: Concerning the nature, varieties, and plausibility of hedonism, 38–54. Oxford University Press.

- Geruso, Michael, and Spears, Dean. 2023. “With a whimper: Depopulation and longtermism.” Population Wellbeing Initiative Working Paper 2304.

- Gillies, Donald. 2000. Philosophical theories of probability. Routledge.

- GiveWell. 2024. “GiveWell's cost-effectiveness analyses.”. Available online: https://www.givewell.org/how-we-work/our-criteria/cost-effectiveness/cost-effectiveness-models.

- Granger, Clive W.J. and Jeon, Yongil. 2007. “Long-term forecasting and evaluation.” International Journal of Forecasting 23:539–551.

- Greaves, Hilary. 2016. “Cluelessness.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 116:311–339.

- Greaves, Hilary and MacAskill, William. 2019. “The case for strong longtermism.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper 7-2019.

- Hagen, Edward H. 2011. “Evolutionary theories of depression: A critical review.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 56:716–726.

- Heyhoe et al. 2017. “Climate models, scenarios, and projections.” In technical report, Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I.

- Horta, Oscar. 2010. “Debunking the idyllic view of natural processes: Population dynamics and suffering in the wild.” Télos 17:73-88.

- —. 2015. “The problem of evil in nature: Evolutionary bases of the prevalence of disvalue.” Relations 3:17-32.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2021. “Climate change 2021: The physical science basis.” Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2024. World economic outlook: April 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2024/04/16/world-economic-outlook-april-2024.

- Johannsen, Kyle. 2020. Wild animal ethics: The moral and political problem of wild animal suffering. Routledge.

- Kaneda, Toshiko and Bremner, Jason. 2014. “Understanding population projections: Assumptions behind the numbers.” Technical report, Population Reference Bureau.

- Karvetski, Christopher W. 2021. “Superforecasters: A decade of stochastic dominance.” Technical White Paper, October 2021. Good Judgment Inc. Available online: https://goodjudgment.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Superforecasters-A-Decade-of-Stochastic-Dominance.pdf.

- Lazarus, Richard S. 1991. Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- Marks, Isaac M., and Nesse, Randolph M. 1994. “Fear and fitness: An evolutionary analysis of anxiety disorders.” Ethology and Sociobiology 15:247-261.

- Masayuki, Morikawa. 2019. “Uncertainty in long-term economic forecasts.” RIETI Discussion Paper Series 19-J-058.

- Millett, P., and Snyder-Beattie, A. 2017. “Existential risk and cost-effective biosecurity.” Health Security 15:373–380.

- Moore, Andrew. 2019. “Hedonism.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/hedonism/.

- Muehlhauser, Luke. 2019. “How feasible is long-range forecasting?” Technical report, Open Philanthropy.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2000. Beyond six billion: Forecasting the world's population. The National Academies Press.

- Nesse, Randolph M., and Ellsworth, Phoebe C. 2009. “Evolution, emotions, and emotional disorders.” American Psychologist 64:129–139.

- Nesse, Randolph M. 2000. “Is depression an adaptation?” Archives of General Psychiatry 57:14-20.

- Newberry, Toby. 2021 “How many lives does the future hold?” Global Priorities Institute Technical Report No. T2-2021.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang. 1995. “Towards welfare biology: Evolutionary economics of animal consciousness and suffering.” Biology and Philosophy 10:255–285.

- Our World in Data. 2024a. “Life expectancy.”. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy.

- —. 2024b. “Childhood Deaths from the Five Most Lethal Infectious Diseases Worldwide.”. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/childhood-deaths-from-the-five-most-lethal-infectious-diseases-worldwide.

- O’Brien, Gary David. 2024. “The case for animal-inclusive longtermism.” Journal of Moral Philosophy (published online ahead of print 2024). [CrossRef]

- Paltsev et al. 2021. Global change outlook 2021. MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

- Pinker, Steven. 2011. The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. Penguin Books.

- Plant, Michael. 2022. “The meat eater problem.” Journal of Controversial Ideas 2:1–21.

- Popper, Karl. 1950. “Indeterminism in quantum physics and in classical physics.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 1:117–133.

- —. 1994. The poverty of historicism. Routledge Classics.

- Rantala, Markus J., and Luoto, Severi. 2022. “Evolutionary perspectives on depression.” In Evolutionary Psychiatry: Current Perspectives on Evolution and Mental Health 117-133. Cambridge University Press.

- Ritchie, Hannah. 2023. “The UN has made population projections for more than 50 years – how accurate have they been?” Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/population-projections.

- Roser, Max, and Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban. 2016. “Global health.”. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/health-meta.

- Russell, Jeffrey Sanford. 2023. “On two arguments for fanaticism.” Noûs 58:565–595.

- Singer, Peter. 2011. The expanding circle: Ethics, evolution, and moral progress. Princeton University Press.

- —. 2023. Animal liberation now: The definitive classic renewed. Harper Perennial.

- Tarsney, Christian. 2023a. “The epistemic challenge to longtermism.” Synthese 201:1–37.

- —. 2023b. “Against anti-fanaticism.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 15-2023.

- etlock, Philip E., and Gardner, Dan M. 2015. Superforecasting: The art and science of prediction. Crown Publishing Group.

- Tetlock, Philip E. 2005. Expert political judgment: How good is it? How can we know? Princeton University Press.

- Tetlock et al. 2023. “Long-range subjective-probability forecasts of slow-motion variables in world politics: Exploring limits on expert judgment.” Futures & Foresight Science 6:1–22.

- Thorstad, David. forthcoming. “Mistakes in the moral mathematics of existential risk.” Ethics.

- Tomasik, Brian. 2015a. “The importance of wild-animal suffering.” Relations 3:133-152.

- —. 2015b. “Risks of astronomical future suffering.” Center on Long-Term Risk. Available online: https://longtermrisk.org/risks-of-astronomical-future-suffering/.

- United Nations. 2024. World population prospects 2024. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- US Census Bureau. 2024. “US population clock.”. Available online: https://www.census.gov/popclock/.

- Wilkinson, Hayden. 2022. “In defense of fanaticism.” Ethics 132:832–862.

- Williamson, Jon. 2018. “Justifying the principle of indifference.” European Journal for Philosophy of Science 8:559–586.

- Wuebbles et al. 2017. “Executive summary.” In technical report, Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I.

Notes

| 1 |

I’m thankful to David Thorstad for his feedback on this description. |

| 2 |

Further on in their paper, Greaves and MacAskill (2021) discuss the ramifications of this assumption. I will address this in section six of this paper: “Implications.” |

| 3 |

By “to a decision-relevant extent,” I mean that the net expected value of humanity’s continued existence must be large enough to shift the decision of someone who aims to do the most impartial good they can with limited resources. For instance, the future’s net expected value is large to a decision-relevant extent if it means that existential risk mitigation saves more net-positive lives per dollar than other interventions do. |

| 4 |

I haven’t discussed the following reservations in this paper, but I believe they deserve a brief mention. First, it appears plausible that, due to the suffering of non-human beings, total net value has not increased over time, turning the “outside view” consideration against astronomically positive expected value in the future. Second, plausible criteria for moral progress outside of Singer’s tell a less clear story about moral progress. Third, it may be difficult to trust criteria for moral progress developed after events that may have determined our moral views and used ex post. |

| 5 |

I thank Adeoluwawumi Adedoyin for his assistance in revising this description. |

| 6 |

Popper (1950) offers the original proof, and this summary of it is described by Popper (1994, p. 9). |

| 7 |

I’m thankful to Christopher Clay for his assistance with revising this explanation. |

| 8 |

I emphasize the verifiability of these (and other) quantitative forecasts because judging the accuracy of long-term forecasts is difficult when made in qualitative terms (Muehlhauser, 2019). |

| 9 |

Even if we think AI might become capable of reliable long-term forecasts, we do not yet have these forecasts, and we do not know what they will predict, or their implications for the future’s total net value. Hence, this possibility does not undermine strong axiological cluelessness until such forecasts are made. Until then, we should account for our enormous—or complete—uncertainty about the long-term future’s total net value. |

| 10 |

I emphasize that the principle of indifference is only being applied to this particular case to avoid objections to a general form of the principle of indifference. I discuss further in Section 4.1.1. On a separate note, because the future’s total net value qualifies as a continuous random variable, we can effectively ignore the possibility of the long-term future’s total net value being zero, as there is zero probability of the future net value being exactly equal to zero. |

| 11 |

While strong axiological cluelessness permits us to consider the value of humans expected to live in the foreseeable future, I omit this value for two reasons. First, precisely estimating the number of years that our forecasts about the future’s net value remain accurate is outside of this paper’s scope. Second, this omission does not affect the point I intend to illustrate, as it appears implausible that the future’s expected population over the next millennium or so is astronomically large. |

| 12 |

Assuming that a rational agent subscribes to Bayesian epistemology and the principle of indifference or other methods of assigning probabilities that produce the same outcome. |

| 13 |

(10 × 0.9) + (-10 × 0.1) = 8 |

| 14 |

First, this example uses single point-estimate probabilities of two outcomes instead of a probability distribution over many possible states. Second, the exact probability of short-term interventions having a negative value is not necessarily 10 percent; it may be higher or lower. Finally, as mentioned above, with no certainty about the long-term future’s net value, ignoring indirect effects on non-human beings, the expected value of decreasing the probability of human extinction (or a permanent reduction in the size of the human population) becomes the number of humans that will die in such an event (eight billion for human extinction) multiplied by the percentage reduction in the risk of these outcomes. |

| 15 |

I’m deeply grateful to David Thorstad for pressing me on this subject. |

| 16 |

Millett and Snyder-Beattie use the expected size of the human population, assuming a constant population of ten billion people on Earth for one million years to derive the estimated life-years lost (L) in a biological existential catastrophe. |

| 17 |

For instance, arguing for strong longtermism, Greaves and MacAskill (2021) write, “higher [future population] numbers would make little difference to the arguments of this paper” (p. 9). |

| 18 |

In this case, I did not create a normal probability distribution for modeling simplicity. As indicated by Table 3, this omission should not affect the results. |

| 19 |

I say “perhaps” because Thorstad (forthcoming) proposes other plausible reasons why Millett and Snyder-Beattie’s model overestimates the cost-effectiveness of biorisk reduction. If these reasons were accounted for, the probability that we assign to futures full of net-positive life-years would need to rise to offset the reduced cost-effectiveness of such a revised model. |

| 20 |

To clarify which existential risks are robust to strong axiological cluelessness, I’ll explain the distinction between s-risks and existential risks (x-risks). Neither of these two concepts are a subset of the other, but they sometimes overlap, such that a risk is considered both an s-risk and an x-risk, as in the prospect of “AI lock-in” (Althaus & Gloor, 2016). If we subscribe to strong axiological cluelessness, it is only in the reduction of risks considered to be both s-risks and x-risks that astronomical gains are to be found. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).