1. Introduction

MAX phases represent a compelling class of materials defined by their unique structure and exceptional combination of properties. Comprising three-element carbides or nitrides with the general formula M

n+1AX

n, where M denotes an early transition metal, A is an element from groups 13–16, and X is carbon or nitrogen, these ternary compounds have garnered significant attention due to their characteristics reminiscent of both metals and ceramics [

1,

2]. Their properties include notable corrosion resistance, thermal stability, high flexural strength, and exceptional fracture toughness, which position them as promising candidates for a variety of applications [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]

The structural integrity of MAX phases stems from their nanolayered crystal architecture, characterized by a hexagonal unit cell (space group P6

3/

mmc). This arrangement features MX octahedra interspersed with A-atom layers, facilitating enhanced electrical and thermal conduction alongside mechanical robustness. As interest in these materials rises, diverse synthetic strategies have emerged, including electrochemical and hydrothermal methods, sol-gel processes, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Among these, sintering techniques are particularly favored due to their straightforward operational framework, well-established in powder metallurgy, and the accessibility of precursor materials [

8].

Various sintering approaches possess distinct advantages and limitations. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis, while straightforward, leads to granular material structures due to the absence of pressure during formation [

9]. Cold sintering, though advantageous for its simplicity, suffers from extended synthesis duration [

10]. Microwave sintering faces challenges related to power distribution and the necessity for specialized equipment [

11]. Conversely, Spark Plasma Synthesis (SPS) presents a compelling alternative that addresses these issues. SPS permits rapid heating and shortened sintering times while facilitating energy efficiency and controlled structures with low grain sizes [

8]. Notably, this method enables synthesis at lower temperatures than the melting points of initial powders, considerably speeding up production cycles [

12].

Furthermore, sintering methods provide the capacity to synthesize doped MAX phases through the substitution of precursor material with chosen dopant [

13]— a process that could lead to diverse modifications in properties. Transition metal (TM) doping is particularly promising, potentially enhancing mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, catalytic performance, and inducing magnetic ordering at sufficient doping levels [

14,

15,

16] . This makes TM-doped MAX phases more attractive for the broad range of applications. Ti

2AlC doping by TMs is of particular interest, as it allows considerable modification of its mechanical [

17] and corrosion properties [

15] as well as thermal stability [

18]. However, synthesis of TM-doped MAX-phases is challenging due to their instability resulting from high number of electrons in transition metal atoms and formation of thermodynamically stable competing phases [

19]. Thus, determining TM doping possibilities and limits is crucial for advancing MAX-phases applications into new domains.

This study examines the impact of sintering temperature, precursor ratios, and the incorporation of doping transition metals (Mo, Ta, Hf, W, Y, Mn) on the formation of the Ti2AlC phase via spark plasma sintering. Additionally, we investigate the purity of the resultant materials and define the thresholds for integrating various dopants, such as Mo, Ta, Hf, W, Y, and Mn, into the Ti2AlC lattice. Our findings facilitate the design of advanced MAX phase materials tailored for specific applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sintering Temperature Optimisation

Titanium carbide TiC, metal titanium Ti, and aluminium carbide Al4C3 were used as precursors to synthesise undoped Ti3AlC2. To obtain samples, at the first stage, mixing and homogenization of a precursors taken in stoichiometric ratios required for Ti3AlC2 formaiton was carried out. Preparation of precursors mixture was performed by dry grinding. The synthesis of the mixture was carried out by mechanochemical grinding in a ball mill under the following conditions: the speed is 300 rpm, the cycle time is 20 minutes of mixing, 10 minutes break. The mixing time was 10 hours, the total time was 15 hours. The ratio of the mass of precursor to the mass of the balls was 1:10.

The synthesis of the target phases from the homogenized powders was carried out by the SPS method, by consolidating the powders on the SPS-515S in-stallation of the company “Dr.Sinter·LABTM" (Japan), according to the general approach: 3 g of powder was placed in a graphite mold (working diameter 15 mm), pressed (pressure 20.7 MPa), then the workpiece was placed in a vacuum chamber (10−5 atm), then sintered. The sintered material was heated with a unipolar low-voltage pulsed current in the On/Off mode, with a frequency of 12 pulses/2 pauses, i.e. the pulse packet duration was 39.6 ms and the pause was 6.6 ms. The temperature of the SPS process was controlled using an optical py-rometer (the lower limit of determination is 650 °C), focused on an open window located in the middle of the plane of the outer wall of the mold with a depth of 5.5 mm. Graphite foil with a thickness of 200 μm was used to prevent baking of the consolidated powder to the mold and plungers, as well as for unhindered extraction of the obtained sample. The mold was wrapped in a heat-insulating fabric to reduce heat loss during heating. The geometric dimensions of the obtained cylindrical matrix shapes are: diameter 15 mm, height 4–10 mm (depending on the type of mold and sintering modes). To determine the effect of the sintering temperature on the composition of the resulting SPS sample, the consolidation of powders obtained by dry grinding was carried out at temperatures of 1200 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C. The heating rate was adjusted in stages: 300 °C/min in the tempera-ture range from 0 to 650 °C, then 50 °C/min from 650 °C and above. The sample was kept at the synthesis temperature for 10 minutes and then cooled to room temperature for 30 minutes. We denote the samples synthesized at 1200 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C as Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200, Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1300, and Ti(7):TiC(5): Al4C3(1)-1400, respectively. Here and in subsequent notations, numbers in parentheses denote the molar ratios of the corresponding components.

2.2. Optimisation of Excess Aluminium Content for Ti2AlC Synthesis

To study the influence of excess aluminium on the yield of the target phase, Ti2AlC was synthesized with an excess of aluminium carbide. Three samples were prepared with an excess of Al4C3 of 10 mol.%, 30 mol.% and 50 mol.%.

Subsequently, the synthesis was carried out by the SPS method in the same way as obtaining the 312-phase described above. The sintering operating temperature was 1300 °C. We denote the samples synthesized at various degrees of aluminium carbide excess as Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.1), Ti(7):TiC(1): Al4C3(1.3), and Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3 (1.5).

2.3. Synthesis of Doped MAX Phases

To obtain transition-metal-doped MAX phases, we used method of Ti substitution by the corresponding ligands in the Ti2AlC compound at the precursor mixture preparation stage. We added Mo, Ta, HfC, W, Y, Mn as dopants. The substitution continued to the limit of incorporation of the TM into the MAX-phase structure. Subsequently, the synthesis of doped MAX phases was carried out similarly to the method described in section 2.1.

Mo-doped samples are denoted as Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mo(0.7) and Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mo(1.4). Ta-doped MAX-phases are denoted as Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(0.7), Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(1.4), Ti(4.9):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(2.1), and Ti(3.5):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(2.5). Hf-doped materials are named Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):HfC(0.7) and Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):HfC(1.4). W-doped samples are denoted as Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):W(0.7) and Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):W(1.4). Y-doped materials are named Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Y(0.7) and Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Y(1.4). Mn-doped samples are denoted as Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mn(0.7) and Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mn(1.4).

2.4. Sample Characterization

The obtained materials were characterized by the method of powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Germany). The survey was carried out with a copper X–ray tube at a current of 15 mA and a voltage of 40 kV (Cu Kα1 radiation at 1.5406 Å). The linear 1D detector Vantec-1 was used as a reflection detector. The survey was carried out in the range of angles 2θ from 5° to 62° with a step of ∆2θ = 0.02° and a signal accumulation time of 35.4 s per point.

The morphology of the obtained samples as well as the elemental composi-tion was determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on a Thermal Scientific SCIOS 2 device (USA), with a energy dispersion spectral analysis (EDX) detector.

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Temperature on the Yield of the Target Phase

To study the effect of the SPS sintering temperature on the formation of the MAX-phase of Ti

3AlC

2 and on the presence of impurities, the samples were sintered at temperatures in the range of 1200–1400 °C.

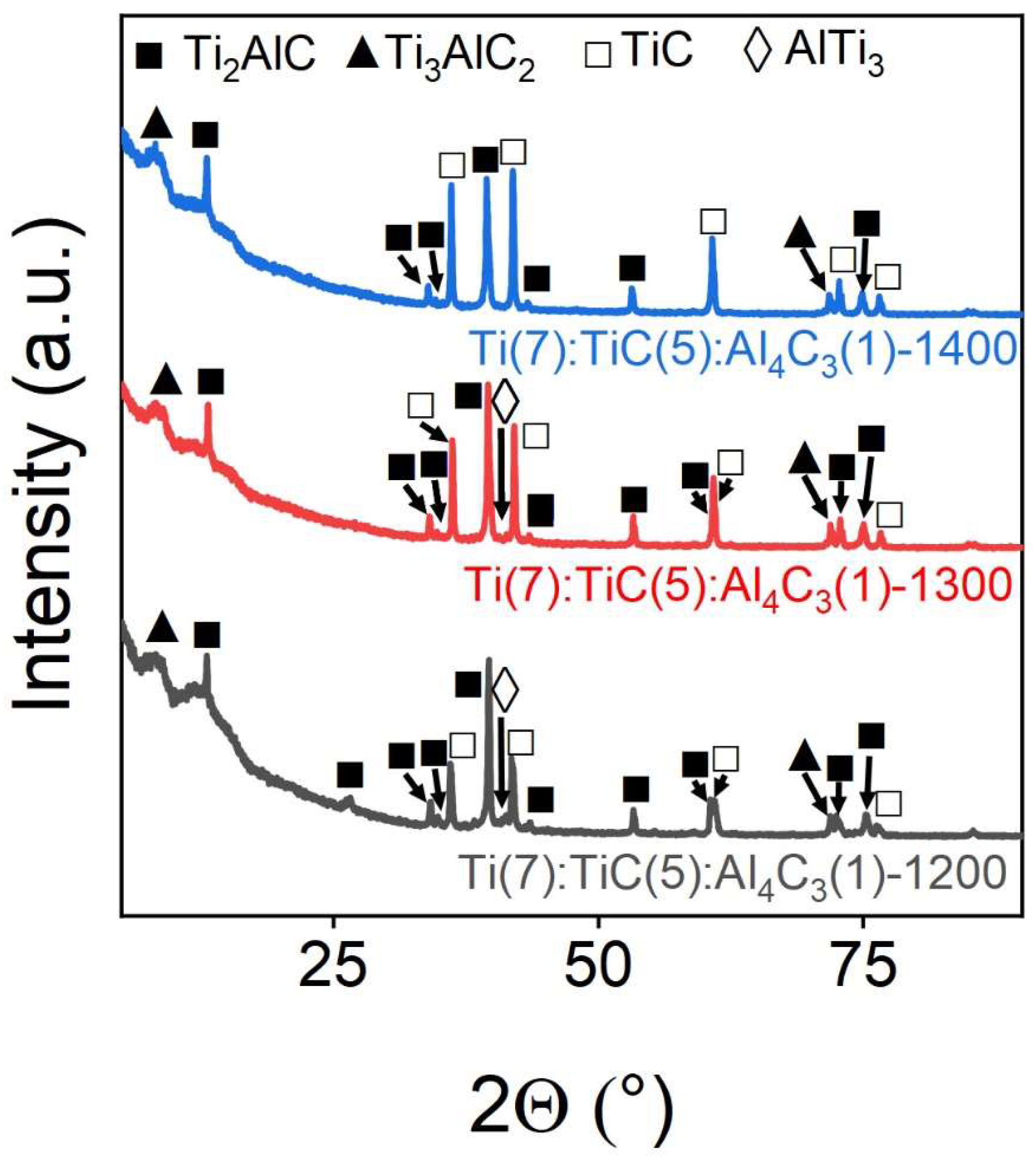

Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the obtained samples. It can be seen that the tem-perature of 1200 °C is insufficient for the formation of a good-quality MAX-phase Ti

3AlC

2: on the X-ray diffractogramm, the reflections corresponding to the Ti

3AlC

2 phase have a low intensity relative to the Ti

2AlC and TiC phase, which are formed simultaneously with the target phase. With an increase in the sintering temperature to 1300 °C, an increase in the relative intensity of the main reflections of the target Ti

3AlC

2 phase is observed, which indicates the increased proportion of the target phase. However, as temperature reached 1400 °C samples flowed out of graphite molds in the furnace. At the same time, all samples exhibit reflections of the TiC and Ti

2AlC phases, which indicate insufficient energy of the system for the synthesis of the Ti

3AlC

2 phase.

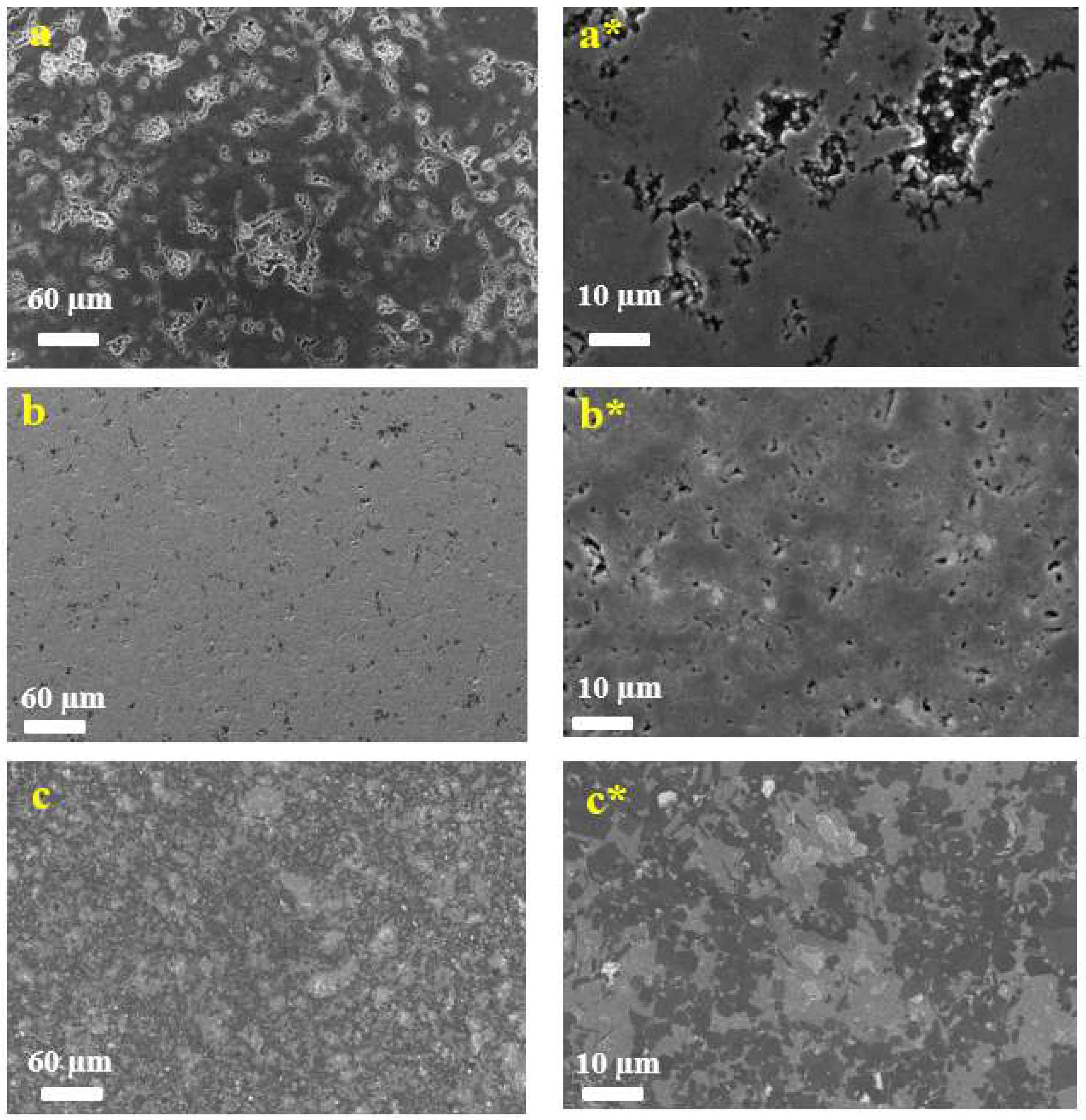

Figure 2 shows the surface morphology of samples of Ti

3AlC

2 stoichiometric composition obtained at various temperatures. For the samples obtained at 1300 °C and 1400 °C, we observe a block structure with separate scales on the surface.

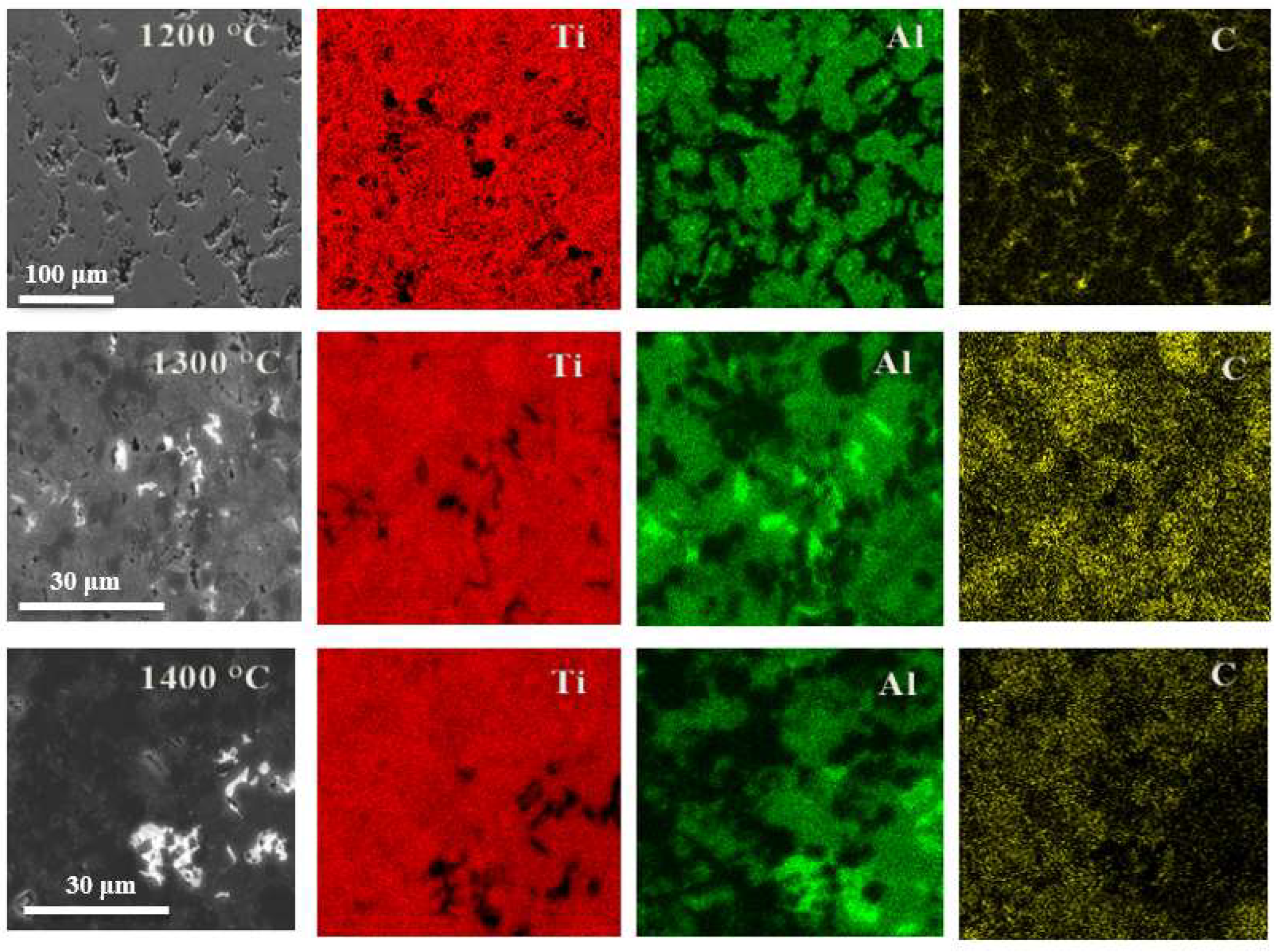

The formation of various crystalline phases (both the target MAX phase and the parasitic phases) was demonstrated above by the PXRD method. However, since the elemental composition of these phases differs significantly, it is possible to estimate their spatial distribution in samples using EDX mapping of SEM images (

Figure 3).

In the samples obtained at 1200 °C, titanium is distributed fairly evenly, while aluminium is distributed in islands. It shows that in this sample there is a large amount of titanium, which did not react with aluminium during the formation of the MAX phase, but remained in the precursor form of titanium carbide TiC, which corresponds to the PXRD data shown in

Figure 1.

In the samples obtained at 1300 °C, we observe the most uniform distribution of all three elements—titanium, aluminium, and carbon—which indicates the highest yield of the target phase, which in turn is confirmed by the PXRD data shown in

Figure 1. However, the maps of this sample again show areas where there is no aluminium, but titanium and carbon are present (evidence of the precursor titanium carbide).

In samples obtained at 1400 °C, we find instead the areas with aluminium but no titanium and carbon, which hints at the formation of metallic aluminium.

The quantitative content of elements in the synthesized samples was determined by the EDX method, the obtained element ratios are presented in

Table 1.

It can be seen that the relative concentrations of the elements largely depend on the temperature of sintering. It is also seen that despite the fact that at the synthesis stage the precursors were mixed in stoichiometric ratios (in terms of target chemical elements), in the final samples the ratios between the elements are far from stoichiometric. The sample synthesized at 1300 °C is the closest to the stoichiometric ratio 3:1:2. It should be noted that in all cases we observe a superstoichiometric content of titanium and carbon with a lack of aluminium. This is probably due to the fact that during spark plasma sintering, more fusible aluminium carbide can volatilize (evaporate). To compensate for this effect, the possibility of using additional (superstoichiometric) aluminium to further increase the yield of the target MAX phase in the samples was investigated.

3.2. The Effect of the Precursor Ratio on the Yield of Ti2AlC

Results presented in

Section 3.1 show that sintering of the components mixed in the ratio reuqired for the synthesis of stiochiometric 312 phase results in a relatively large yield of the 211 phase. Furthermore, the amount of the 211 phase increases with increasing temperature, as shown by the variation in the intensity of the XRD reflections of the Ti₂AlC phase. Consequently, it can be concluded that the energy of the system is insufficient to convert the mixture of precursors into Ti₃AlC₂.

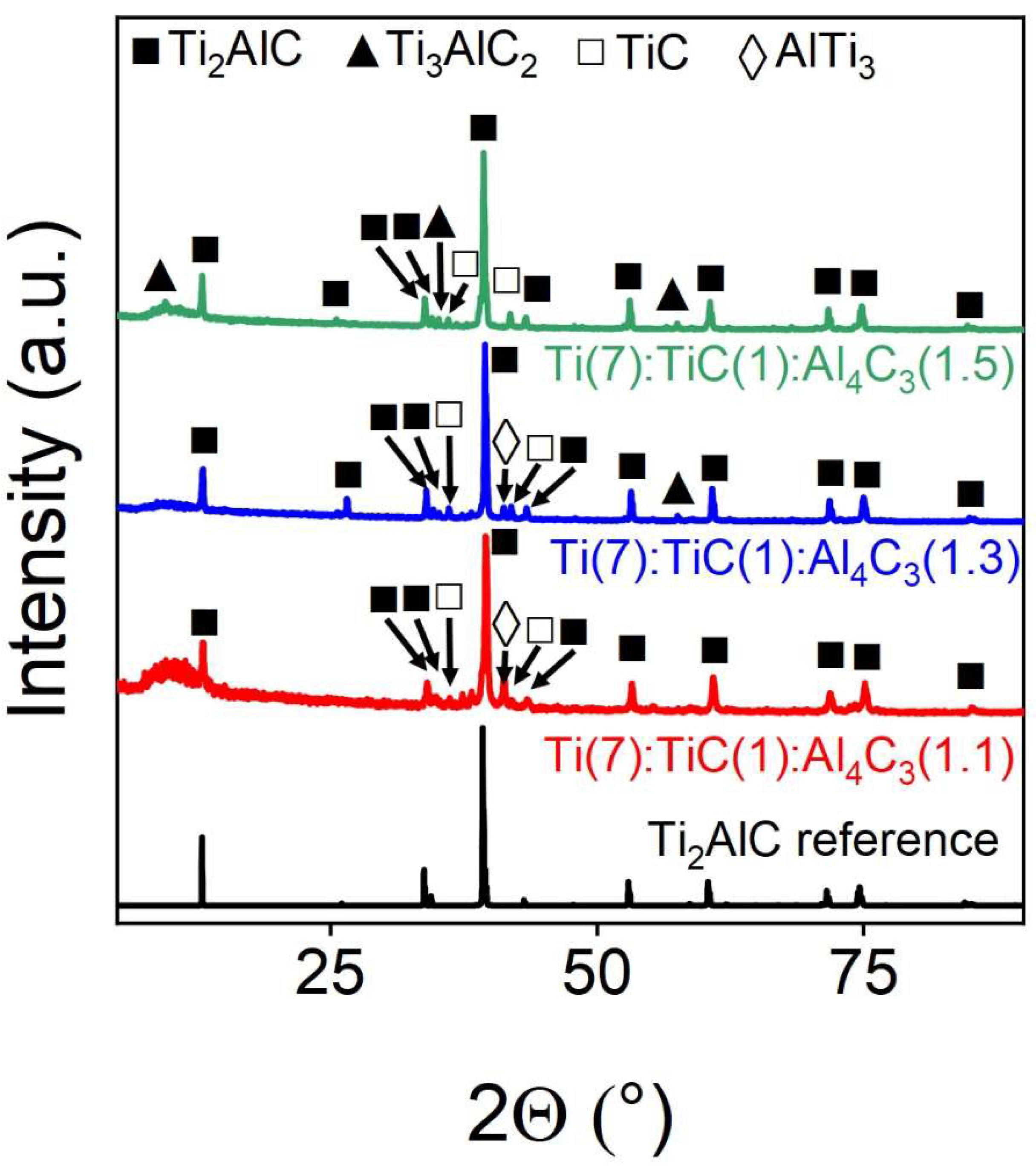

Thus, the effect of the Al

4C

3 content in the initial mixture on the yield of the target Ti

2AlC phase was further investigated by obtaining samples with a super-stoichiometric aluminium carbide content of 10, 30, and 50 mol.%. PWRD`s of the obtained samples are shown in

Figure 4. It was found that the highest yield of the target phase is obtained when 1.3 fractions of Al

4C

3 is introduced into the initial composition. With a 10% increase, the reflections of the AlTi

3 intermetallic phase increases, and with a 1.5-fold increase in concentration, reflections of the Ti

3AlC

2 phase appear.

The content of various crystalline phases in the synthesized samples was determined by refinement by the Rietveld method and is presented in

Table 2. It can be seen that additional, superstoichiometric aluminium in the amount of 30 % mol. introduced into the precursor mixture helps to increase the yield of the target phase to more than 90%.

3.3. The Effect of Doping Additives on MAX-Phases

To elaborate on the possibility of doped MAX-phase synthesis via SPS, optimal conditions allowing for 90.32% Ti2AlC synthesis were modified by the addition of transition metals.

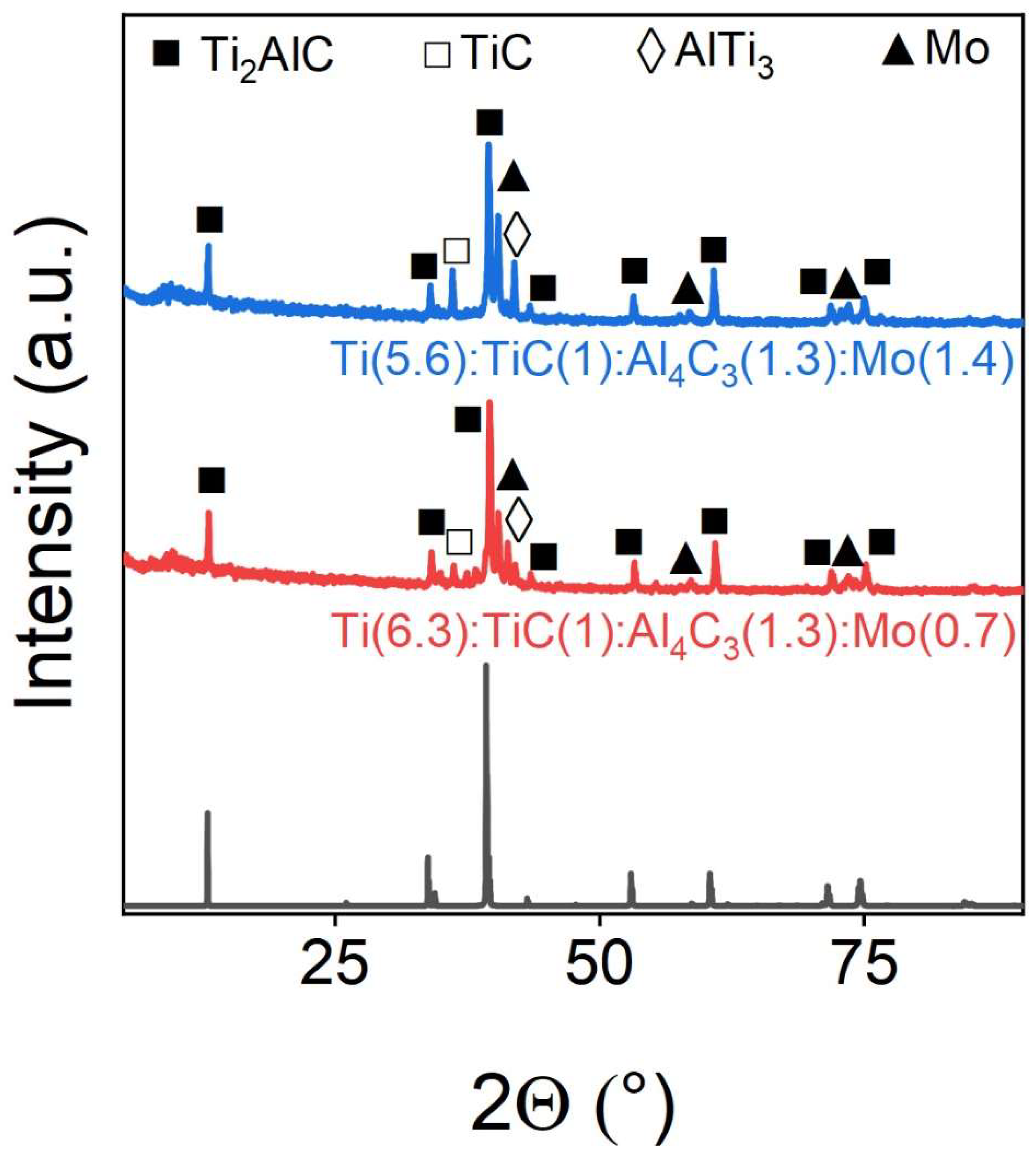

Figure 5 shows X-ray diffraction patterns of Mo- doped Ti

2AlC. It can be seen that molybdenum practically does not integrate into the MAX-phase structure. The peaks of metallic molybdenum are clearly visible. This is also confirmed by the phase composition data obtained by the Rietveld refinement method, presented in

Table 3.

It can be seen that almost all doping molybdenum exist in an individual metallic crystalline form after synthesis.

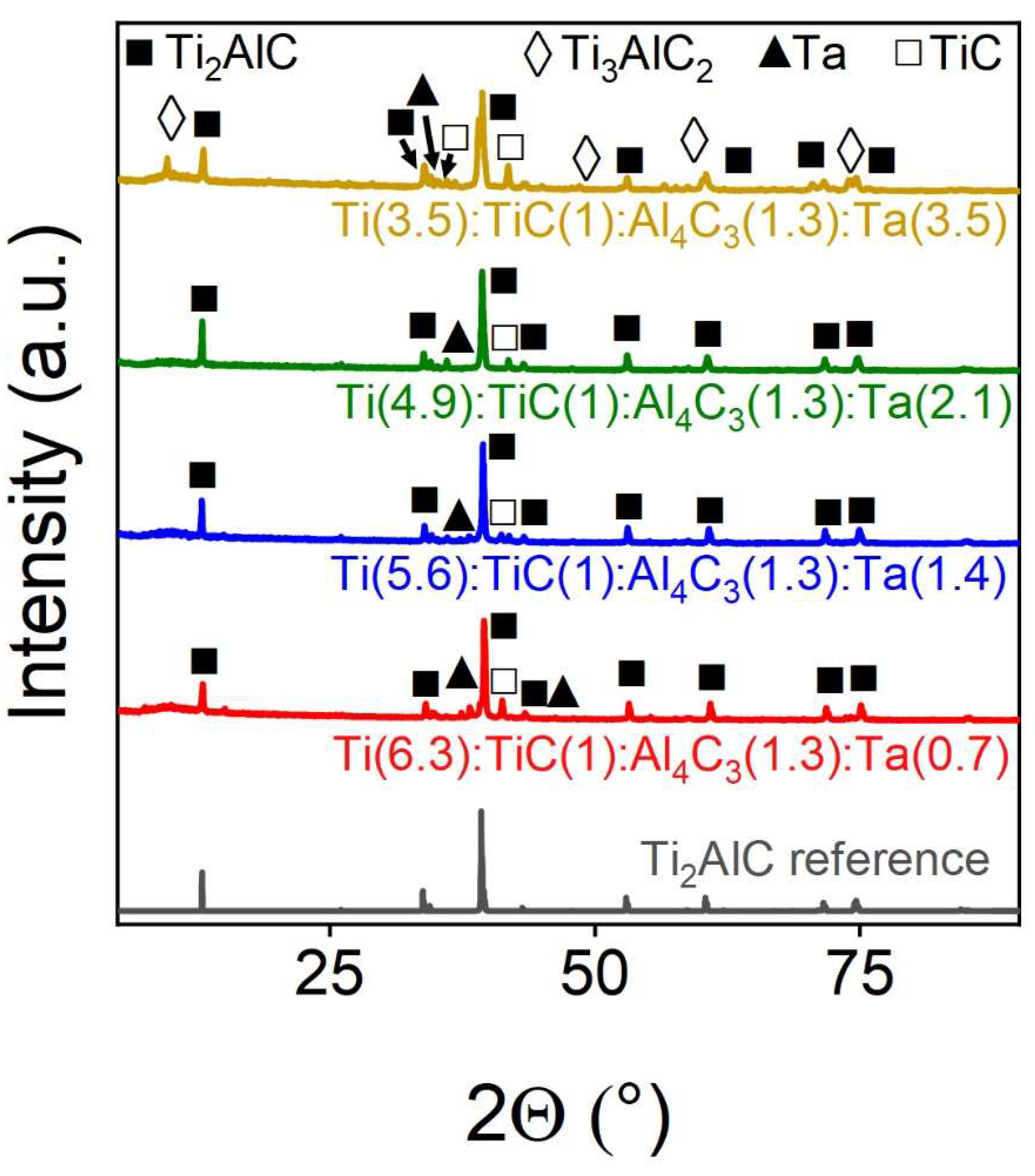

Tantalum, on the contrary, is efficiently integrated into the structure of the MAX phase of Ti

2AlC (

Figure 6 and

Table 4). Thus, with the introduction of up to 30% tantalum, samples with a target phase yield of about 90% are obtained. Moreover, the more tantalum is introduced into the precursor mixture, the greater the yield of the target phase we observe. And when 50% of titanium is replaced by, tantalum is added to the composition, it is possible to obtain about 50% of the 312 MAX phase of Ti

3AlC

2, which previously could not be obtained by other methods. However, as shown in

Table 4, the sample with higher Ta content demonstrates the mixture of both 211 and 312 phases as well as other phases including metallic Ta and titanium carbide, which indicates that SPS synthesis of Ta-doped MAX-phases requires further optimisation.

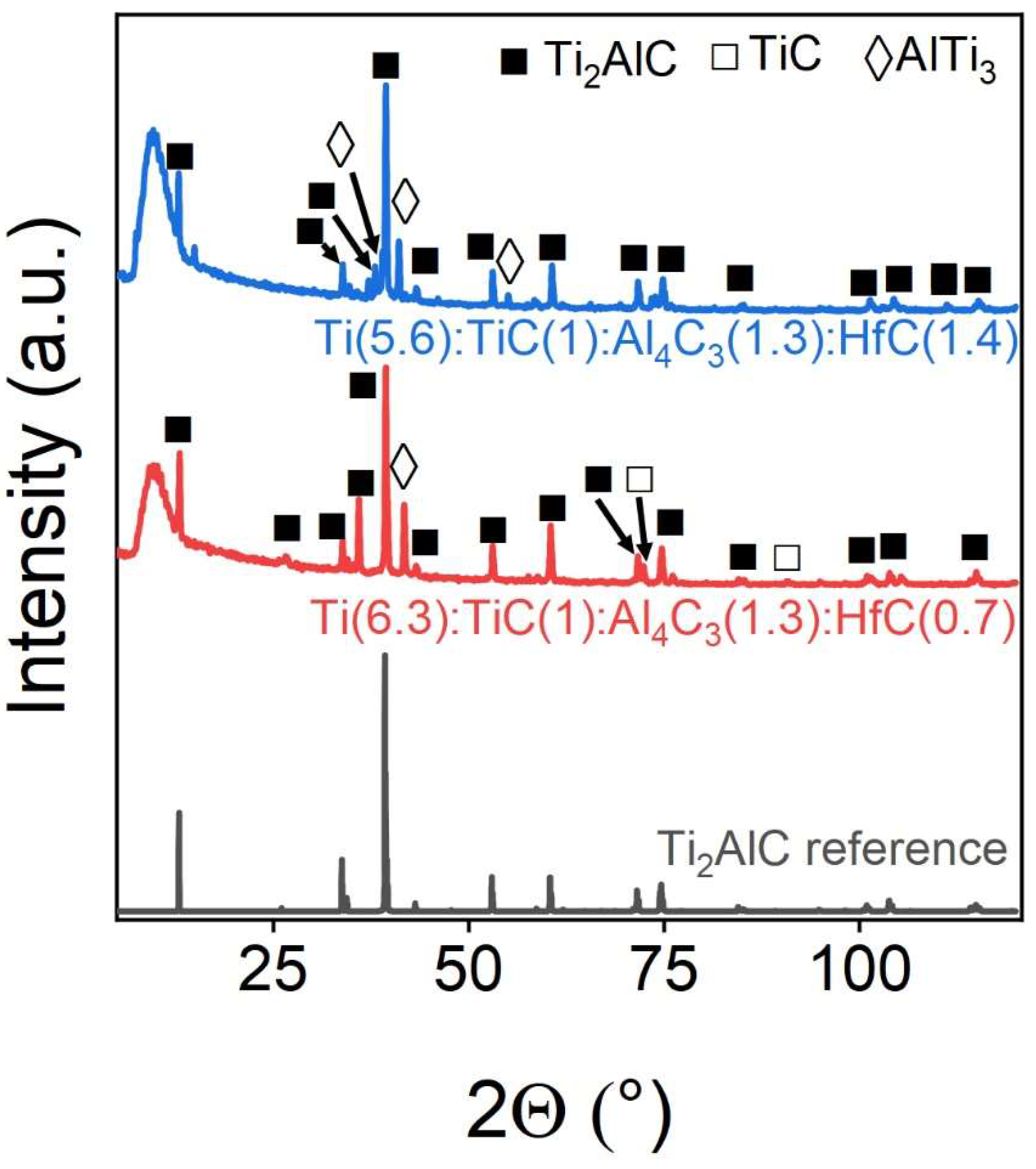

Hafnium can also be effectively integrated into the MAX phase, but only in limited quantities.

Figure 7 shows experimental PXRD`s, and

Table 5 shows the corresponding phase compositions of the samples obtained by Rietveld refinement. It can be seen that when 10% hafnium is introduced, it is completely embedded in the MAX-phase structure, whereas when its concentration increases to 20%, additional peaks appear in the region of 35–38°, which may indicate the presence of metallic hafnium or a precursor form, hafnium carbide.

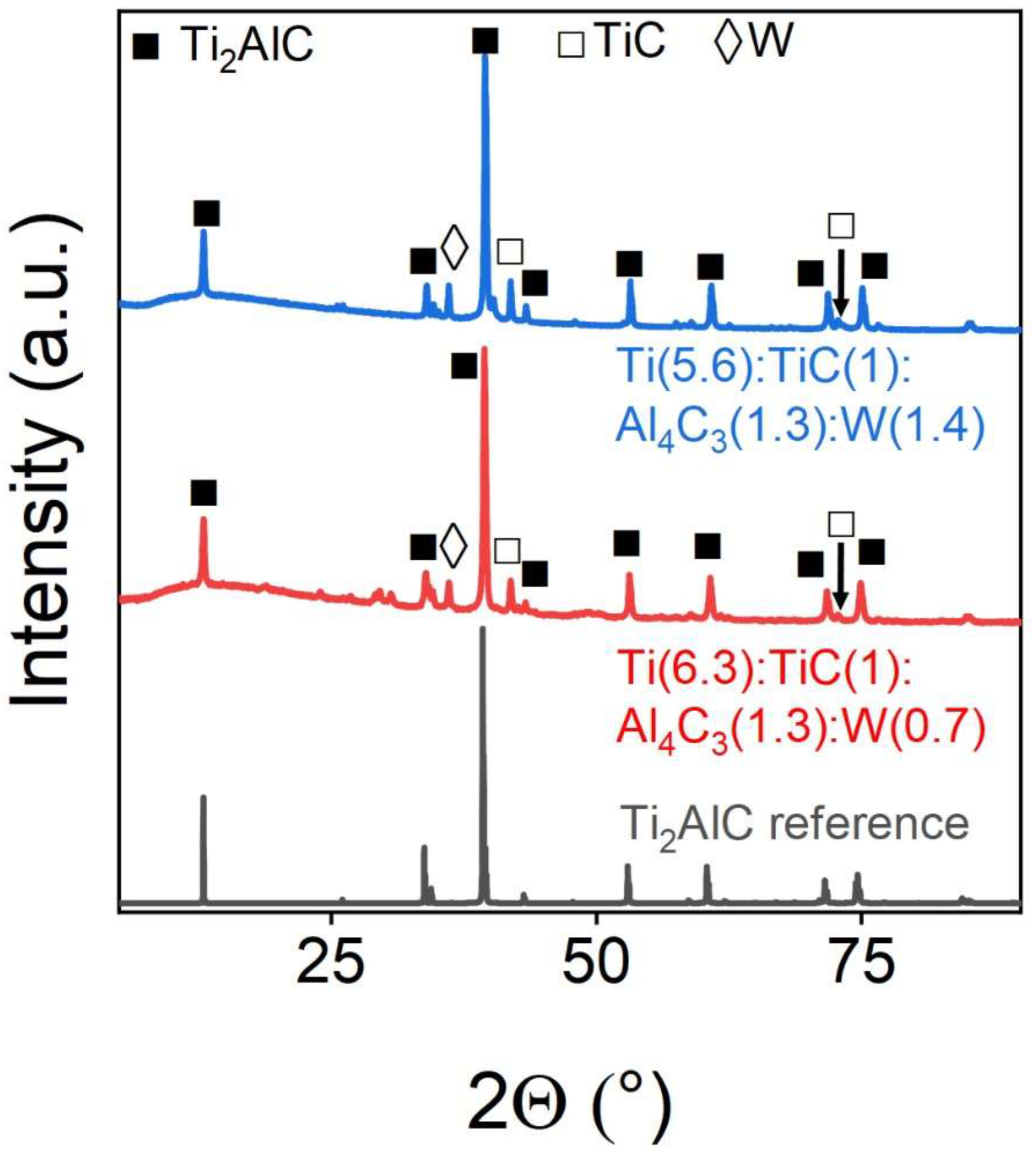

Tungsten can also be embedded in the MAX-phase crystal lattice of Ti

2AlC.

Figure 8 and

Table 6 show the corresponding PXRD`s and the Rietveld refine-ment of the phase composition based on them. Tungsten is completely integrated into the structure, while the intensity of the AlTi

3 intermetallic reflex increases by 20% compared to the pure MAX phase of Ti

2AlC.

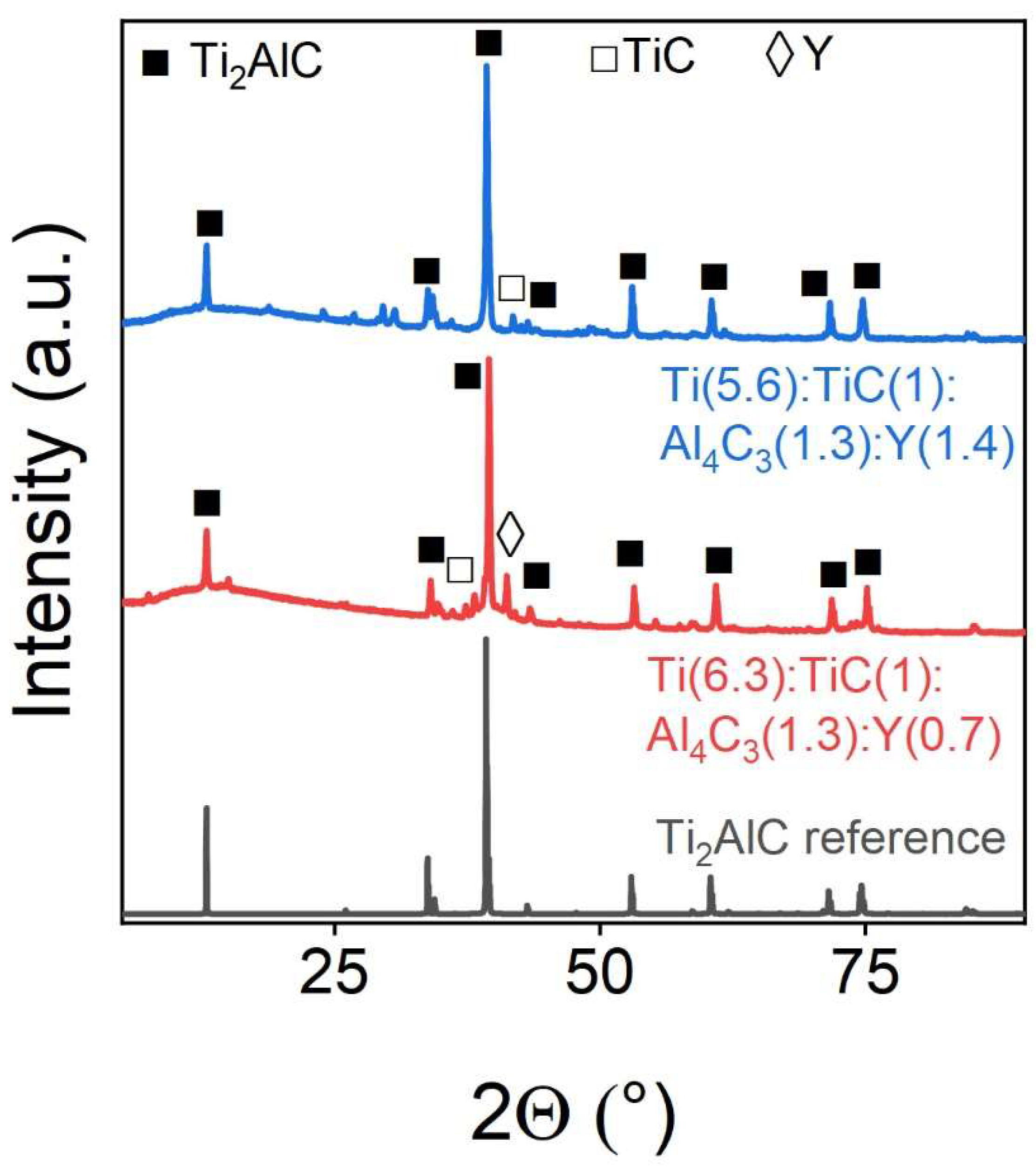

Yttrium is also well integrated into the MAX-phase structure.

Figure 9 and

Table 7 show the corresponding PXRD`s and the refinement of the phase composition based on them by the Rietveld method. It can be seen that an increase in the concentration of the doping element leads to a more pristine material. In this regard, yttrium acts similarly to tantalum.

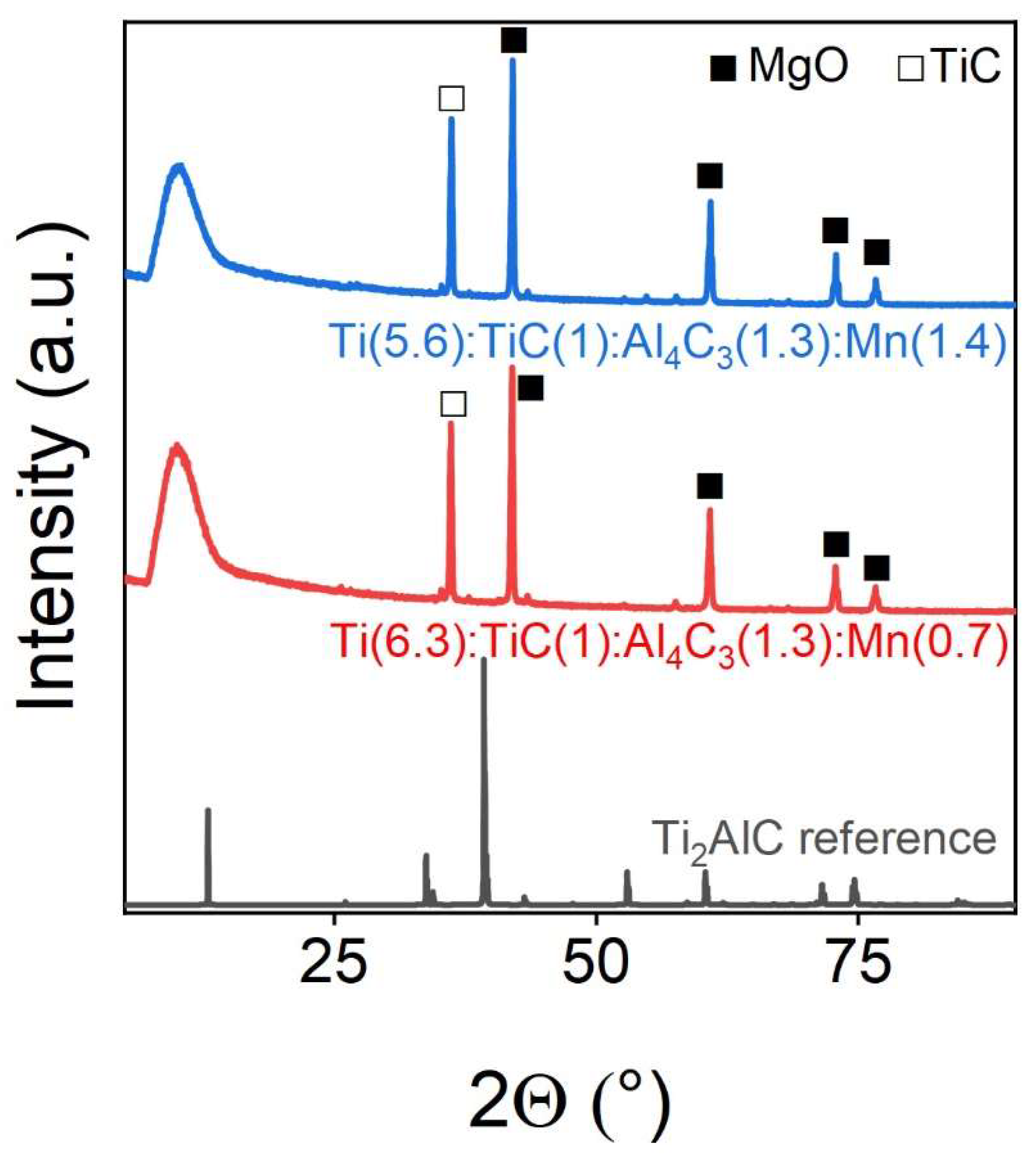

Manganese, when introduced into the MAX phase of Ti

2AlC, does not al-low the target phase to form at all, which is clearly visible on the PXRD`s shown in

Figure 10. Thus, there is no main peak of Ti

2AlC in the 40° region, while after sintering by the SPS method, titanium carbide with magnesium oxide is obtained according to the results of XRD. The phase composition of the samples is shown in

Table 8.

Obtained data indicates that Mo and Mn cannot be incorporated into Ti

2AlC phase, while Ta, Hf, W, Y efficiently substitute Ti atoms in the obtained (Ti

2-xTM

X)AlC (TM = Ta, Hf, W, Y). Substitution possibility depends on the mismatch between the radii of host and substituent ions [

20]. However, there are additional factors affecting the stability of resulting compound, such as valence electron concentration [

21] and thermodynamic stability [

22]. Analysis of activation and phase transformation processes is typically required for the assessment of the possibility of substituted phases [

22]. We hope that current work will pave the way to the computational analysis of TM-substituted MAX-phases.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Ti₂AlC MAX-phase ceramics can be synthesized via spark plasma sintering with controlled precursor compositions and optimized thermal conditions. A 30% excess of Al₄C₃ and a sintering temperature of 1300 °C were found to maximize phase purity, achieving over 90% yield. Doping studies revealed that Ta, Hf, W, and Y can be successfully incorporated into the Ti₂AlC lattice, whereas Mo and Mn remain as separate phases, limiting their applicability in direct substitution. Our results refine the understanding of phase stability in transition metal-doped MAX phases, paving the way for tailored material design in structural and functional applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. Arsenin; Formal analysis, A. Vyshnevyy and A. Bolshakov; Investigation, M. Gurin, E. Kolodeznikov and A. Syuy; Methodology, D. Shtarev, A. Bolshakov and A. Syuy; Supervision, A. Syuy; Validation, I. Zavidovskiy, A. Bolshakov and A. Syuy; Visualization, A. Arsenin; Writing – original draft, M. Gurin, D. Shtarev, I. Zavidovskiy, A. Vyshnevyy and A. Syuy.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (FSMG-2024-0014) and Russian Science Foundation, grant 22-79-10312.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, Z.M. Progress in Research and Development on MAX Phases: A Family of Layered Ternary Compounds. International Materials Reviews 2011, 56, 143–166. [CrossRef]

- Eklund, P.; Beckers, M.; Jansson, U.; Högberg, H.; Hultman, L. The M+1AX Phases: Materials Science and Thin-Film Processing. Thin Solid Films 2010, 518, 1851–1878. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.W.; Ma, X.; Tang, G.; Miao, B.; Niu, J. Fabrication and Mechanical Properties of Cr2AlC MAX Phase Coatings on TiBw/Ti6Al4V Composite Prepared by HiPIMS. Materials 2021, 14, 826. [CrossRef]

- Alruqi, A.B. Engineering the Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Ti3AlC2, Hf3AlC2, Hf3GaC2, (ZrHf)3AlC2, and (ZrHf)4AlN3 MAX Phases via the Ab Initio Method. Crystals 2025, 15, 87. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.W.; Ma, X.; Tang, G.; Paudel, R. Structural Stability, Electronic, Mechanical, Phonon, and Thermodynamic Properties of the M2GaC (M = Zr, Hf) MAX Phase: An Ab Initio Calculation. Materials 2020, 13, 5148. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Li, Y.-Y. Synthesis of High-Purity Silicon Carbide Nanowires by a Catalyst-Free Arc-Discharge Method. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 10294–10297. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bei, G. Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review. Materials 2017, 10, 366. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Kashkarov, E.B.; Travitzky, N.; Syrtanov, M.S.; Lider, A.M. Sintering of MAX-Phase Materials by Spark Plasma and Other Methods. J Mater Sci 2021, 56, 1980–2015. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Liang, B.; Wang, M. Investigation of Formation Mechanism of Ti3SiC2 by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2013, 41, 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, A.; Mercadelli, E.; Gondolini, A.; Sanson, A. Exploring the Potential of Cold Sintering for Proton-Conducting Ceramics: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 5116. [CrossRef]

- Rybakov, K.I.; Olevsky, E.A.; Krikun, E.V. Microwave Sintering: Fundamentals and Modeling. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 1003–1020. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.R.; Wu, A.V.D.K.-H. Synthesis of Ti2AlC by Spark Plasma Sintering of TiAl–Carbon Nanotube Powder Mixture. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2010, 490, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Syuy, A.; Shtarev, D.; Lembikov, A.; Gurin, M.; Kevorkyants, R.; Tselikov, G.; Arsenin, A.; Volkov, V. Effective Method for the Determination of the Unit Cell Parameters of New MXenes. Materials 2022, 15, 8798. [CrossRef]

- Du, C.-F.; Xue, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Liu, W. Mo-Doped Cr-Ti-Mo Ternary o-MAX with Ultra-Low Wear at Elevated Temperatures. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2022, 42, 7403–7413. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Han, G.; Zhang, W. Preparation, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance Behavior of (Zr, Mo, Cr)-Doped Ti3AlC2 Ceramics. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 20694–20705. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, Q.; Kuang, Y. Excellent CoOx Hy /C Oxygen Evolution Catalysts Evolved from the Rapid In Situ Electrochemical Reconstruction of Cobalt Transition Metals Doped into the V2 SnC MAX Phase at A Layers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 1116–1125. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Du, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Lu, X.; Guan, C.; Zhao, Z. Trends in Structural, Electronic and Elastic Properties of Ti2AC (A = Al, Zn, Cu, Ni) Based on Late Transition Metals Substitution. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2023, 662, 414936. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y. Nb Doping in Ti3AlC2: Effects on Phase Stability, High-Temperature Compressive Properties, and Oxidation Resistance. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2017, 37, 3641–3645. [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.P.; Mallett, S.; Juelsholt, M.; Pazniak, H.; Wiedwald, U.; Page, K.; Birkel, C.S. Structure Determination and Magnetic Properties of the Mn-Doped MAX Phase Cr2 GaC. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 6082–6091. [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, E.; Fabbri, E.; Bi, L.; Rupp, J.L.M.; Lippert, T.; Pergolesi, D.; Traversa, E. Effect of Dopant–Host Ionic Radii Mismatch on Acceptor-Doped Barium Zirconate Microstructure and Proton Conductivity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 9739–9747. [CrossRef]

- Distl, B.; Stein, F. Ti-Al-Based Alloys with Mo: High-Temperature Phase Equilibria and Microstructures in the Ternary System. Philosophical Magazine 2024, 104, 28–54. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Li, S.; Bai, S. Enhancing Phase Stability in Low-Activation TiVTa-Based Alloys Through CALPHAD-Guided Design. JOM 2025, 77, 1524–1535. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples of stoichiometric Ti3AlC2 composition obtained at various sintering temperatures. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 1.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples of stoichiometric Ti3AlC2 composition obtained at various sintering temperatures. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 2.

SEM images of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples obtained at various temperatures: 1200 °C (a, a*), 1300 °C (b, b*), and 1400 °C (c, c*).

Figure 2.

SEM images of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples obtained at various temperatures: 1200 °C (a, a*), 1300 °C (b, b*), and 1400 °C (c, c*).

Figure 3.

SEM images of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples obtained at various temperatures and mapping the distribution of various elements obtained by X-ray energy dispersion spectroscopy mapping.

Figure 3.

SEM images of Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200/1300/1400 samples obtained at various temperatures and mapping the distribution of various elements obtained by X-ray energy dispersion spectroscopy mapping.

Figure 4.

Experimental powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.1/1.3/1.5), samples obtained at different concentrations of superstoichiometric aluminium. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 4.

Experimental powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.1/1.3/1.5), samples obtained at different concentrations of superstoichiometric aluminium. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 5.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Mo-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 5.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Mo-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 6.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ta-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 6.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ta-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 7.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Hf-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 7.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Hf-doped samples. The marks above the reflections indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 8.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of W-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 8.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of W-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 9.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Y-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 9.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Y-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 10.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Mn-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Figure 10.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Mn-doped samples. The marks above the reflexes indicate the corresponding target and impurity phases.

Table 1.

The content of elements in the samples of Ti3AlC2 stoichiometric compositions synthesized at various sintering temperatures.

Table 1.

The content of elements in the samples of Ti3AlC2 stoichiometric compositions synthesized at various sintering temperatures.

| Sample |

Atomic Content of the Elements, at. % |

Ti:Al:C Ratio (Normalized to Aluminium) |

| Ti |

Al |

C |

| Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1200 |

46.13 ± 0.09 |

11.71 ± 0.03 |

42.16 ± 0.10 |

3.94:1:3.6 |

| Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1300 |

48.09 ± 0.09 |

14.72 ± 0.03 |

37.20 ± 0.10 |

3.27:1:2.53 |

| Ti(7):TiC(5):Al4C3(1)-1400 |

47.53 ± 0.09 |

12.70 ± 0.03 |

39.77 ± 0.10 |

3.74:1:3.13 |

Table 2.

Phase composition of samples depending on the content of Al4C3.

Table 2.

Phase composition of samples depending on the content of Al4C3.

| Sample |

Ti2AlC, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

AlTi3, wt.% |

Ti3AlC2, wt.% |

| Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.1) |

86.18 |

2.48 |

11.34 |

- |

| Ti(7):TiC(1): Al4C3(1.3) |

90.32 |

4.17 |

5.51 |

- |

| Ti(7):TiC(1):Al4C3 (1.5) |

70.22 |

1.62 |

- |

28.16 |

Table 3.

Phase composition of Mo-doped samples.

Table 3.

Phase composition of Mo-doped samples.

| Sample |

Ti2AlC, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

AlTi3, wt.% |

Mo, wt.% |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mo(0.7) |

79.6 |

3.4 |

8.7 |

8.3 |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mo(1.4) |

71.11 |

14.43 |

- |

14.46 |

Table 4.

Phase composition of Ta-doped samples.

Table 4.

Phase composition of Ta-doped samples.

| Sample |

Ti2AlC, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

Ta, wt.% |

Ti3AlC2, wt.% |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(0.7) |

83.36 |

13.48 |

3.15 |

- |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(1.4) |

89.06 |

8.56 |

2.39 |

- |

| Ti(4.9):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(2.1) |

93.89 |

7.03 |

4.05 |

- |

| Ti(3.5):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Ta(2.5) |

45.62 |

2.77 |

0.61 |

51.00 |

Table 5.

Phase composition of Hf-doped samples.

Table 5.

Phase composition of Hf-doped samples.

| Sample |

Ti2AlC, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

AlTi3, wt.% |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):HfC(0.7) |

82.24 |

17.76 |

- |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):HfC(1.4) |

90.51 |

- |

9.49 |

Table 6.

Phase composition of W-doped samples.

Table 6.

Phase composition of W-doped samples.

| Sample |

Weight content of the phase, % |

| Ti2AlC |

TiC |

W2C |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):W(0.7) |

93.81 |

6.0 |

0.18 |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):W(1.4) |

91.61 |

7.9 |

0.49 |

Table 7.

Phase composition of Y-doped samples.

Table 7.

Phase composition of Y-doped samples.

| Sample |

Ti2AlC, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

Y, wt.% |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Y(0.7) |

88.91 |

4.36 |

6.74 |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Y(1.4) |

97.79 |

2.21 |

- |

Table 8.

Phase composition of Mn-doped Ti2AlC samples.

Table 8.

Phase composition of Mn-doped Ti2AlC samples.

| Sample |

MgO, wt.% |

TiC, wt.% |

| Ti(6.3):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mn(0.7) |

75.7 |

24.3 |

| Ti(5.6):TiC(1):Al4C3(1.3):Mn(1.4) |

61.5 |

38.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).