Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Preclinical Studies of the Gut-Lung Axis in Pulmonary Hypertension

2. Clinical Evidence of the Gut-Lung Axis in PAH

3. Potential Approaches to Modulate the Gut-Lung Axis to Treat PAH

4. Contribution of Infections in PAH Pathogenesis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, Nicolls MR. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;115:165-175. [CrossRef]

- Sweatt AJ, Hedlin HK, Balasubramanian V, Hsi A, Blum LK, Robinson WH, Haddad F, Hickey PM, Condliffe R, Lawrie A, et al. Discovery of Distinct Immune Phenotypes Using Machine Learning in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124:904-919. [CrossRef]

- Steiner MK, Syrkina OL, Kolliputi N, Mark EJ, Hales CA, Waxman AB. Interleukin-6 overexpression induces pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2009;104:236-244, 228p following 244. [CrossRef]

- Soon E, Crosby A, Southwood M, Yang P, Tajsic T, Toshner M, Appleby S, Shanahan CM, Bloch KD, Pepke-Zaba J, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II deficiency and increased inflammatory cytokine production. A gateway to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:859-872. [CrossRef]

- Savai R, Pullamsetti SS, Kolbe J, Bieniek E, Voswinckel R, Fink L, Scheed A, Ritter C, Dahal BK, Vater A, et al. Immune and inflammatory cell involvement in the pathology of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:897-908. [CrossRef]

- Furness JB, Kunze WA, Clerc N. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. II. The intestine as a sensory organ: neural, endocrine, and immune responses. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G922-928. [CrossRef]

- Castro GA, Arntzen CJ. Immunophysiology of the gut: a research frontier for integrative studies of the common mucosal immune system. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:G599-610. [CrossRef]

- Thenappan T, Khoruts A, Chen Y, Weir EK. Can intestinal microbiota and circulating microbial products contribute to pulmonary arterial hypertension? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317:H1093-H1101. [CrossRef]

- Van Hul M, Cani PD, Petitfils C, De Vos WM, Tilg H, El-Omar EM. What defines a healthy gut microbiome? Gut. 2024;73:1893-1908. [CrossRef]

- Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2369-2379. [CrossRef]

- Trankle CR, Canada JM, Kadariya D, Markley R, De Chazal HM, Pinson J, Fox A, Van Tassell BW, Abbate A, Grinnan D. IL-1 Blockade Reduces Inflammation in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure: A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Phase IB/II Pilot Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:381-384. [CrossRef]

- Toshner M, Church C, Harbaum L, Rhodes C, Villar Moreschi SS, Liley J, Jones R, Arora A, Batai K, Desai AA, et al. Mendelian randomisation and experimental medicine approaches to interleukin-6 as a drug target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022;59. [CrossRef]

- Zamanian RT, Badesch D, Chung L, Domsic RT, Medsger T, Pinckney A, Keyes-Elstein L, D'Aveta C, Spychala M, White RJ, et al. Safety and Efficacy of B-Cell Depletion with Rituximab for the Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis-associated Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204:209-221. [CrossRef]

- Callejo M, Mondejar-Parreño G, Barreira B, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Morales-Cano D, Esquivel-Ruiz S, Moreno L, Cogolludo Á, Duarte J, Perez-Vizcaino F. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Affects the Rat Gut Microbiome. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9681. [CrossRef]

- Hong W, Mo Q, Wang L, Peng F, Zhou Y, Zou W, Sun R, Liang C, Zheng M, Li H, et al. Changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome in a rat model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Bioengineered. 2021;12:5173-5183. [CrossRef]

- Luo L, Chen Q, Yang L, Zhang Z, Xu J, Gou D. MSCs Therapy Reverse the Gut Microbiota in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Mice. Front Physiol. 2021;12:712139. [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Wang L, Mo Q, Peng F, Hong W, Zhou Y, Sun R, Li H, Liang C, Zhao D, et al. Disease-associated gut microbiome and metabolome changes in rats with chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1022181. [CrossRef]

- Luo L, Yin H, Gou D. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Changes in Three Pulmonary Hypertension Rat Models. Microorganisms. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Zhou D, Miao J, Zhang C, Li X, Feng H, Xing Y, Zhang Z, Bao C, Lin Z, et al. Microbiome and metabolome dysbiosis of the gut-lung axis in pulmonary hypertension. Microbiol Res. 2022;265:127205. [CrossRef]

- Sharma RK, Oliveira AC, Yang T, Kim S, Zubcevic J, Aquino V, Lobaton GO, Goel R, Richards EM, Raizada MK. Pulmonary arterial hypertension-associated changes in gut pathology and microbiota. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6. [CrossRef]

- Nijiati Y, Maimaitiyiming D, Yang T, Li H, Aikemu A. Research on the improvement of oxidative stress in rats with high-altitude pulmonary hypertension through the participation of irbesartan in regulating intestinal flora. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:4540-4553. [CrossRef]

- Adak A, Maity C, Ghosh K, Mondal KC. Alteration of predominant gastrointestinal flora and oxidative damage of large intestine under simulated hypobaric hypoxia. Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52:180-186. [CrossRef]

- Ranchoux B, Bigorgne A, Hautefort A, Girerd B, Sitbon O, Montani D, Humbert M, Tcherakian C, Perros F. Gut-Lung Connection in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:402-405. [CrossRef]

- Prisco SZ, Eklund M, Moutsoglou DM, Prisco AR, Khoruts A, Weir EK, Thenappan T, Prins KW. Intermittent Fasting Enhances Right Ventricular Function in Preclinical Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e022722. [CrossRef]

- Sharma RK, Oliveira AC, Yang T, Karas MM, Li J, Lobaton GO, Aquino VP, Robles-Vera I, de Kloet AD, Krause EG, et al. Gut Pathology and Its Rescue by ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2) in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:206-216. [CrossRef]

- Gaowa N, Panke-Buisse K, Wang S, Wang H, Cao Z, Wang Y, Yao K, Li S. Brisket Disease Is Associated with Lower Volatile Fatty Acid Production and Altered Rumen Microbiome in Holstein Heifers. Animals (Basel). 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Zhang H, Liu Y, Long Y. The Role of Gut and Airway Microbiota in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:929752. [CrossRef]

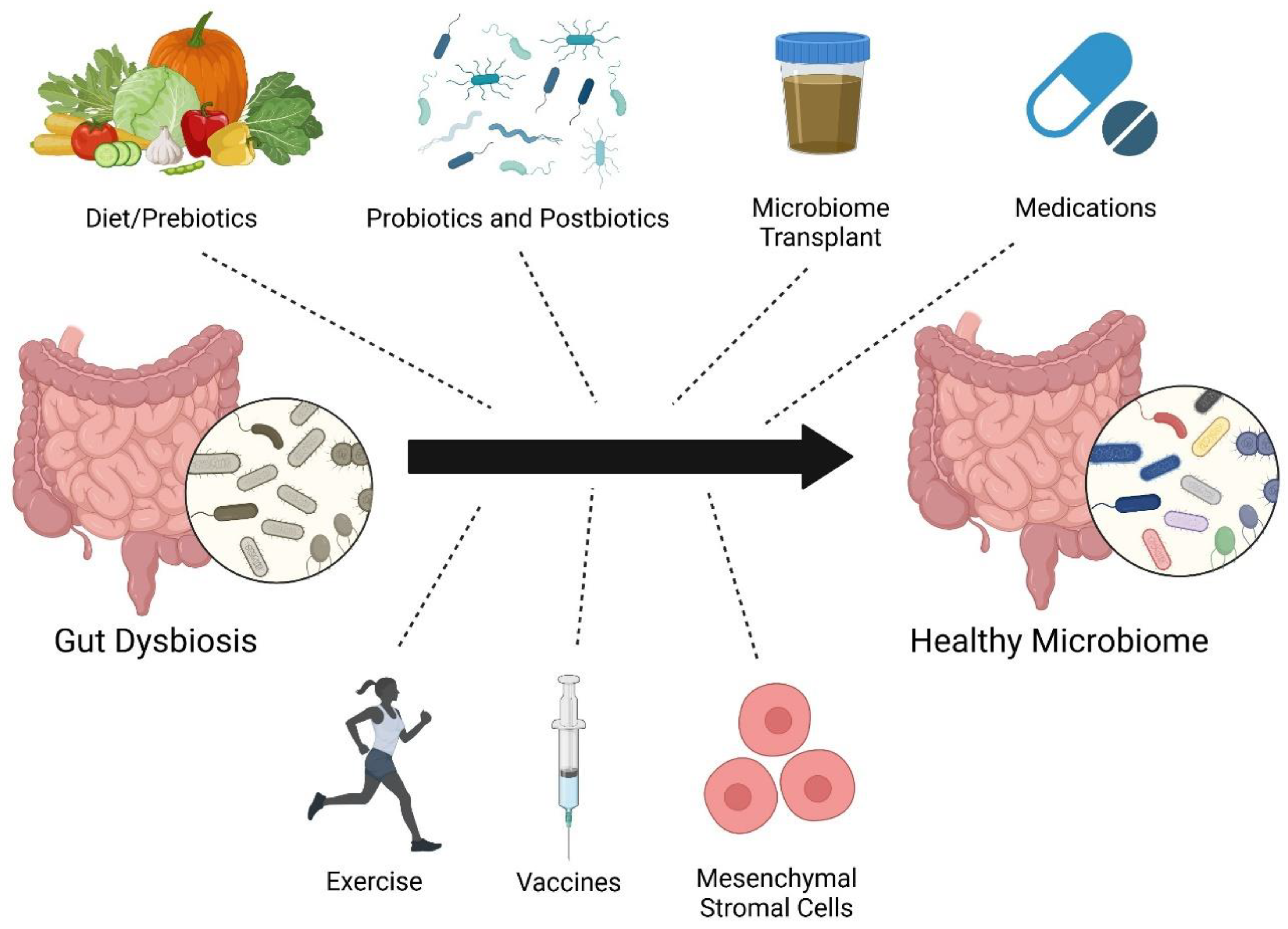

- Sanada TJ, Hosomi K, Shoji H, Park J, Naito A, Ikubo Y, Yanagisawa A, Kobayashi T, Miwa H, Suda R, et al. Gut microbiota modification suppresses the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension in an SU5416/hypoxia rat model. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020929147. [CrossRef]

- Lawrie A, Hameed AG, Chamberlain J, Arnold N, Kennerley A, Hopkinson K, Pickworth J, Kiely DG, Crossman DC, Francis SE. Paigen diet-fed apolipoprotein E knockout mice develop severe pulmonary hypertension in an interleukin-1-dependent manner. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1693-1705. [CrossRef]

- Brittain EL, Talati M, Fortune N, Agrawal V, Meoli DF, West J, Hemnes AR. Adverse physiologic effects of Western diet on right ventricular structure and function: role of lipid accumulation and metabolic therapy. Pulm Circ. 2019;9:2045894018817741. [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov NV, Kostyunina DS, Macori G, Dillon E, Brady T, Sundaramoorthy G, Connolly C, Blanco A, Fanning S, Brennan L, et al. High-Soluble-Fiber Diet Attenuates Hypoxia-Induced Vascular Remodeling and the Development of Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension. Hypertension. 2023;80:2372-2385. [CrossRef]

- Mamazhakypov A, Weiß A, Zukunft S, Sydykov A, Kojonazarov B, Wilhelm J, Vroom C, Petrovic A, Kosanovic D, Weissmann N, et al. Effects of macitentan and tadalafil monotherapy or their combination on the right ventricle and plasma metabolites in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020947283. [CrossRef]

- Krautkramer KA, Fan J, Bäckhed F. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:77-94. [CrossRef]

- Karoor V, Strassheim D, Sullivan T, Verin A, Umapathy NS, Dempsey EC, Frank DN, Stenmark KR, Gerasimovskaya E. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Attenuates Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling and Inflammation in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [CrossRef]

- 2022 Annual World Congress of the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute. In: Pulm Circ. © 2022 The Authors. Pulmonary Circulation published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute.; 2022.

- Pulgarin A, Alabdallat M, Methe B, Morris A, Al Ghouleh I. Abstract 18631: Mechanistic Insight on the Protective Role of Microbiome-Derived Butyrate in Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation. 2023;148:A18631-A18631. doi: doi:10.1161/circ.148.suppl_1.18631.

- Huang Y, Lin F, Tang R, Bao C, Zhou Q, Ye K, Shen Y, Liu C, Hong C, Yang K, et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2022;66:452-460. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Zeng Q, Gao J, Yang B, Zhou J, Li K, Li L, Wang A, Li X, Liu Z, et al. High-circulating gut microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide is associated with poor prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Open. 2022;2:oeac021. [CrossRef]

- Videja M, Vilskersts R, Korzh S, Cirule H, Sevostjanovs E, Dambrova M, Makrecka-Kuka M. Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Protects Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism and Cardiac Functionality in a Rat Model of Right Ventricle Heart Failure. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:622741. [CrossRef]

- Levy M, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Metabolites: messengers between the microbiota and the immune system. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1589-1597. [CrossRef]

- Roager HM, Licht TR. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3294. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira AC, Yang T, Li J, Sharma RK, Karas MK, Bryant AJ, de Kloet AD, Krause EG, Joe B, Richards EM, et al. Fecal matter transplant from Ace2 overexpressing mice counteracts chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12015. [CrossRef]

- Wedgwood S, Warford C, Agvatisiri SR, Thai PN, Chiamvimonvat N, Kalanetra KM, Lakshminrusimha S, Steinhorn RH, Mills DA, Underwood MA. The developing gut-lung axis: postnatal growth restriction, intestinal dysbiosis, and pulmonary hypertension in a rodent model. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:472-479. [CrossRef]

- Prisco SZ, Blake M, Kazmirczak F, Moon R, Vogel N, Moutsoglou D, Thenappan T, Prins KW. Restructures the Micro/Mycobiome to Combat Glycoprotein-130 Associated Microtubule Remodeling and Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. bioRxiv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alcayaga-Miranda F, Cuenca J, Khoury M. Antimicrobial Activity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Current Status and New Perspectives of Antimicrobial Peptide-Based Therapies. Front Immunol. 2017;8:339. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Ni B, Liu Q, He F, Li L, Zhong X, Zheng X, Lu J, Chen X, Lin H, et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental colitis by normalizing the gut microbiota. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:475. [CrossRef]

- Ocansey DKW, Wang L, Wang J, Yan Y, Qian H, Zhang X, Xu W, Mao F. Mesenchymal stem cell-gut microbiota interaction in the repair of inflammatory bowel disease: an enhanced therapeutic effect. Clin Transl Med. 2019;8:31. [CrossRef]

- Liu A, Li C, Wang C, Liang X, Zhang X. Impact of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on the Gut Microbiota and Microbiota Associated Functions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Evidence on Animal Models. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;19:981-992. [CrossRef]

- Kim KC, Lee JC, Lee H, Cho MS, Choi SJ, Hong YM. Changes in Caspase-3, B Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma-2, Interleukin-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Expression after Human Umbilical Cord Blood Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transfusion in Pulmonary Hypertension Rat Models. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:79-92. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad SA, Abbas AY, Saidu Y, Fakurazi S, Bilbis LS. Therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells and secretome in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biochimie. 2020;168:156-168. [CrossRef]

- Abudukeremu A, Aikemu A, Yang T, Fang L, Aihemaitituoheti A, Zhang Y, Shanahaiti D, Nijiati Y. Effects of the ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas axis on gut flora diversity and intestinal metabolites in SuHx mice. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1412502. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Rigatto K, Gazzana MB, Knorst MM, Richards EM, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK. Altered Gut Microbiome Profile in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;75:1063-1071. [CrossRef]

- Jose A, Apewokin S, Hussein WE, Ollberding NJ, Elwing JM, Haslam DB. A unique gut microbiota signature in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A pilot study. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12051. [CrossRef]

- Moutsoglou DM, Tatah J, Prisco SZ, Prins KW, Staley C, Lopez S, Blake M, Teigen L, Kazmirczak F, Weir EK, et al. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients Have a Proinflammatory Gut Microbiome and Altered Circulating Microbial Metabolites. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207:740-756. [CrossRef]

- Dong W, Ma L, Huang Q, Yang X, Mei Z, Kong M, Sun Z, Zhang Z, Li J, Zou J, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in pulmonary hypertension in highlanders and lowlanders. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, Radjabzadeh D, Wang J, Demirkan A, Le Roy CI, Raygoza Garay JA, Finnicum CT, Liu X, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53:156-165. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Tan JS, Xu J, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Duan A, Huang Z, Zhang S, Gao L, et al. Causal impact of gut microbiota and associated metabolites on pulmonary arterial hypertension: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24:185. [CrossRef]

- Su L, Wang X, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Yao D, Pan T, Huang X. Exploring the Causal Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Pulmonary Artery Hypertension: Insights From Mendelian Randomization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025:e038150. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Zhang T, Lu W, Duan X, Luo X, Liu S, Chen Y, Li Y, Chen J, Liao J, et al. Altered Airway Microbiota Composition in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:1589-1599. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Zhang T, Xing Y, Lu W, Chen J, Luo X, Wu X, Liu S, Chen L, Zhang Z, et al. Airway delivery of Streptococcus salivarius is sufficient to induce experimental pulmonary hypertension in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2023;180:2102-2119. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Zhong B, Jiang Q, Lu W, Wu H, Xing Y, Wu X, Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Li P, et al. Distinct airway mycobiome signature in patients with pulmonary hypertension and subgroups. BMC Med. 2025;23:148. [CrossRef]

- Salminen S, Collado MC, Endo A, Hill C, Lebeer S, Quigley EMM, Sanders ME, Shamir R, Swann JR, Szajewska H, et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:649-667. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann P. The immunological interplay between vaccination and the intestinal microbiota. NPJ Vaccines. 2023;8:24. [CrossRef]

- Buys R, Avila A, Cornelissen VA. Exercise training improves physical fitness in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:40. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Galán S, Parra V, Cuenca J. Unraveling the pathogenesis of viral-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension: Possible new therapeutic avenues with mesenchymal stromal cells and their derivatives. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2025;1871:167519. [CrossRef]

- Moutsoglou DM. 2021 American Thoracic Society BEAR Cage Winning Proposal: Microbiome Transplant in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:13-16. [CrossRef]

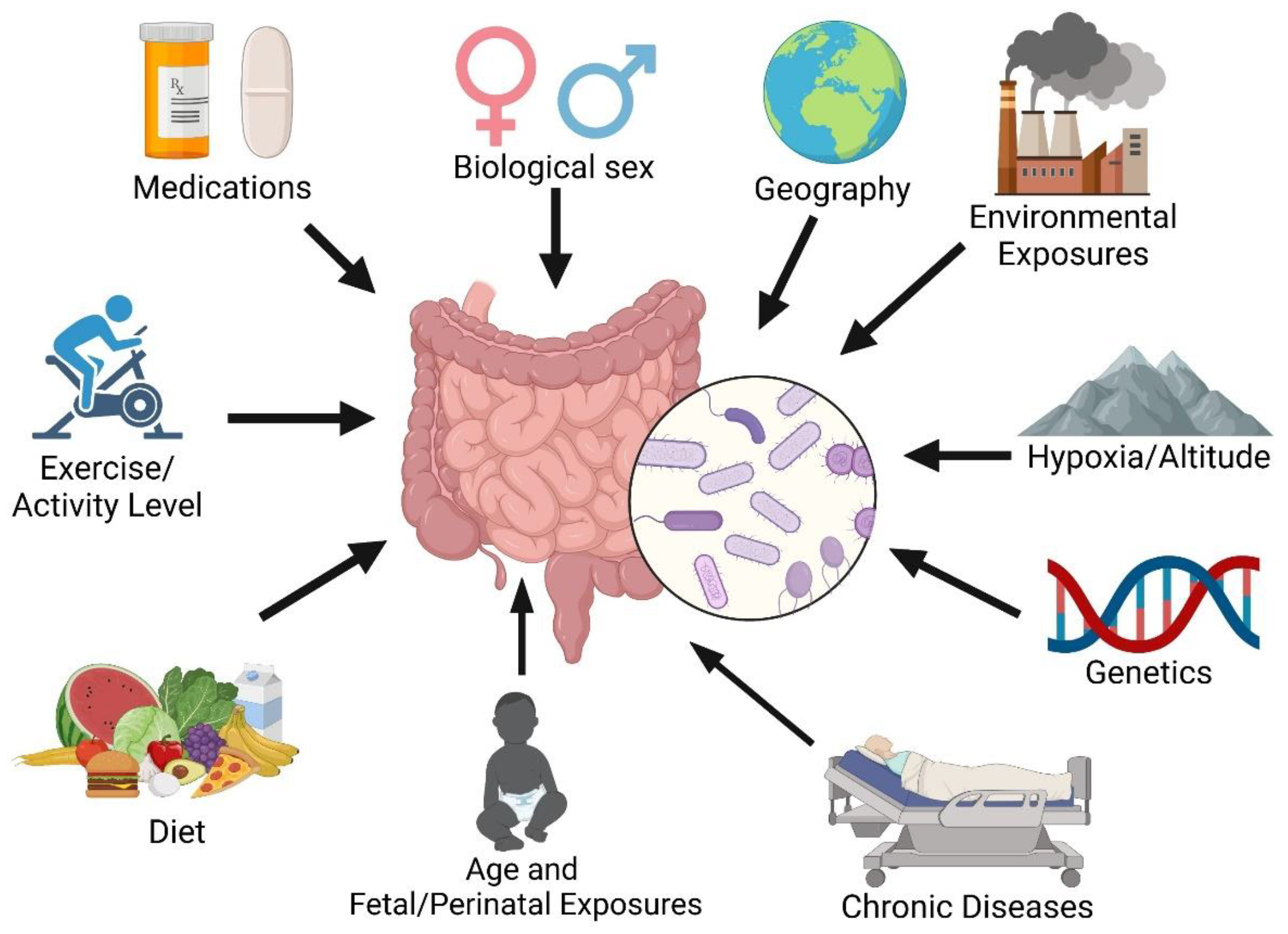

- Ahn J, Hayes RB. Environmental Influences on the Human Microbiome and Implications for Noncommunicable Disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:277-292. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Y, Catheline D, Houeijeh A, Sharma D, Du L, Besengez C, Deruelle P, Legrand P, Storme L. Maternal omega-3 PUFA supplementation prevents hyperoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in the offspring. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315:L116-L132. [CrossRef]

- Marinho Y, Villarreal ES, Loya O, Oliveira SD. Mechanisms of lung endothelial cell injury and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2024;327:L972-L983. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira SD, Almodóvar S, Butrous G, De Jesus Perez V, Fabro A, Graham BB, Mocumbi A, Nyasulu PS, Tura-Ceide O, Oliveira RKF, et al. Infection and pulmonary vascular diseases consortium: United against a global health challenge. Pulm Circ. 2024;14:e70003. [CrossRef]

- Cool CD, Voelkel NF, Bull T. Viral infection and pulmonary hypertension: is there an association? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5:207-216. [CrossRef]

- Pullamsetti SS, Savai R, Janssen W, Dahal BK, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Ghofrani HA, Weissmann N, Schermuly RT. Inflammation, immunological reaction and role of infection in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:7-14. [CrossRef]

- Mizutani T, Ishizaka A, Koga M, Tsutsumi T, Yotsuyanagi H. Role of Microbiota in Viral Infections and Pathological Progression. Viruses. 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Alves JL, Gavilanes F, Jardim C, Fernandes CJCD, Morinaga LTK, Dias B, Hoette S, Humbert M, Souza R. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in the southern hemisphere: results from a registry of incident Brazilian cases. Chest. 2015;147:495-501. [CrossRef]

- Knafl D, Gerges C, King CH, Humbert M, Bustinduy AL. Schistosomiasis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29. [CrossRef]

- Marinho Y, Villarreal ES, Aboagye SY, Williams DL, Sun J, Silva CLM, Lutz SE, Oliveira SD. Schistosomiasis-associated pulmonary hypertension unveils disrupted murine gut-lung microbiome and reduced endoprotective Caveolin-1/BMPR2 expression. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1254762. [CrossRef]

- Almodovar S, Cicalini S, Petrosillo N, Flores SC. Pulmonary hypertension associated with HIV infection: pulmonary vascular disease: the global perspective. Chest. 2010;137:6S-12S. [CrossRef]

- Rocafort M, Gootenberg DB, Luévano JM, Paer JM, Hayward MR, Bramante JT, Ghebremichael MS, Xu J, Rogers ZH, Munoz AR, et al. HIV-associated gut microbial alterations are dependent on host and geographic context. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1055. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).