1. Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) continue to impose severe health and socioeconomic burdens on vulnerable populations worldwide. Among these, trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma parasites presents a significant diagnostic challenge [

1], particularly in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Conventional diagnosis via manual microscopy of blood smears is not only labor-intensive and subjective but also dependent on specialized expertise, often resulting in delays in diagnosis and treatment. This scenario underscores the urgent need for automated, reliable, and scalable diagnostic tools [

2].

Recent advances in deep learning have transformed medical imaging and real-time object detection. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and, in particular, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) [

3] family of models have demonstrated exceptional speed and accuracy in various detection tasks. Our previous work, YOLO-Para [

4], adapted a custom YOLOv8 framework for malaria parasite detection, successfully capturing subtle morphological features in challenging microscopy images. Building on that success, we now extend our approach to the domain of trypanosome detection.

In this work, we introduce YOLO-Tryppa, a tailored detection framework explicitly engineered for the identification of Trypanosoma brucei. YOLO-Tryppa incorporates targeted architectural modifications designed to improve the localization of small parasites, which are prevalent in the Tryp dataset [

5]. We used the YOLOv11m architecture and proposed several key modifications, like the use of ghost convolutions instead of standard convolutional layers, to reduce computational complexity while maintaining accuracy. Additionally, on the one hand, we introduced a dedicated

P2 prediction head to specialize in detecting small objects, and, on the other hand, we removed the prediction head for larger objects, thereby aligning the architecture with the specific characteristics of trypanosome images.

The development and evaluation of YOLO-Tryppa are supported by the Tryp dataset [

5], a comprehensive collection of microscopy images with meticulously annotated bounding boxes for Trypanosoma brucei. This dataset captures the diverse and complex presentations of the parasite, providing a robust benchmark for assessing detection performance. By tailoring the YOLO-Para architecture with these strategic modifications, our work demonstrates the adaptability of deep learning models in medical diagnostics. It contributes a valuable tool for enhancing disease screening in resource-constrained environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the related work on Trypanosoma detection. Section 3 describes the materials and methods used in this study, including the dataset description, the design and implementation of YOLO-Tryppa, and the architectural changes to optimize small object detection. Then, Section 4.2, presents the experimental evaluation and the obtained results. Finally, in Sections 5 and 6 , we discuss the current limitations of our detection approach and outline future research directions.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the literature on object detection in medical imaging, focusing on parasite detection in microscopy images, establishing the context for our proposed YOLO-Tryppa framework, designed to enhance the detection of Trypanosoma brucei brucei in resource-constrained settings. Specifically, this section is organized into four subsections: Section 2.1 addresses the historical progression of object detection methods in medical imaging, including the transition to deep learning; Section 2.2 presents the unique challenges and methodologies associated with parasite detection in microscopy images; Section 2.3 explores the role of attention mechanisms in enhancing detection accuracy by focusing on salient image features; finally, Section 2.4 examines lightweight object detection models suitable for resource-constrained environments.

2.1. Evolution of Object Detection in Medical Imaging

Traditional approaches in medical imaging relied heavily on handcrafted features and classical computer vision techniques [

6]. While these methods offered early insights, their performance was often hindered by sensitivity to noise and variability in clinical data. The advent of CNNs [

7] marked a paradigm shift by enabling robust, hierarchical feature extraction directly from raw images. This breakthrough originated the development of R-CNN [

8], Fast R-CNN [

9], and single-shot detectors, which collectively improved both detection accuracy and processing speed [

10]. Modern deep learning architectures have redefined object detection by making an effective balance between high accuracy and real-time performance. Models such as the YOLO family [

3], Faster R-CNN [

9], and RetinaNet [

11] employ end-to-end training pipelines that predict bounding boxes and class probabilities directly from full images [

4,

12]. These models have been successfully adapted to medical imaging contexts by fine-tuning them to capture subtle pathological features despite challenges like low contrast and variable morphology [

13]. Custom modifications and transfer learning strategies have further bolstered their applicability to specialized tasks, including the detection of parasitic infections.

2.2. Parasite Detection in Microscopy Images

Detecting parasites in microscopy images is inherently challenging due to the low contrast between parasites and surrounding tissues, high morphological variability, and the presence of imaging artifacts [

14]. Trypanosomiasis, a significant public health concern, affects regions across South America, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa [

15]. The disease, transmitted by blood-sucking insects such as tsetse flies and tabanids, impacts both humans and animals, leading to serious zoonotic consequences. Although molecular techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunological assays remain the gold standard for detection, they demand skilled personnel, involve multiple processing steps, and require expensive equipment [

16]. In contrast, microscopic examination offers a rapid and cost-effective diagnostic alternative. However, its low sensitivity and the variability in interpretation among technicians underscore the need for automated, computer-aided diagnostic (CAD) systems [

17,

18]. The integration of artificial intelligence in CAD systems holds promise for standardizing and accelerating the detection process, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Current state-of-the-art research on parasite detection in microscopy images predominantly focuses on the identification of malaria parasites. For instance, in [

19], three pre-trained models alongside transfer learning techniques are employed to accurately identify and classify malaria parasites. Similarly, in [

20], a CNN, integrated with a random forest algorithm, is utilized for detecting Plasmodium malaria parasites. With regard to Trypanosoma localization, random forest-based machine learning approaches are applied in [

21] to extract features from microscopy images, facilitating the identification and quantification of the parasite. Additionally, Jung et al. [

22] use the ResNet18 model on datasets derived from microscope video recordings of blood smears to detect the presence or absence of parasites. Furthermore, in [

23], ResNet50 was utilized for identifying Trypanosoma in images, and the trained model was further validated as an autonomous screening system using a vector database constructed with images processed through the K-Nearest Neighbor algorithm.

2.3. Integration of Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms have become critical in enhancing CNN architectures for medical image analysis. These mechanisms enable models to focus selectively on the most relevant regions within an image, with techniques such as spatial, channel, and self-attention [

24] significantly improving the accuracy of feature localization while mitigating the impact of background noise. This targeted approach reduces the rate of false positives and improves the detection of subtle and dispersed features [

25,

26]. Moreover, recent innovations in attention module design facilitate dynamic feature-weighting during training and inference stages, thereby further optimizing detection performance. This capability is particularly essential for the accurate identification of parasites in complex microscopy images [

27].

2.4. Lightweight Object Detectors

Deploying object detection models in resource-constrained environments, such as field clinics and remote laboratories, necessitates architectures that balance accuracy with computational efficiency [

28,

29,

30]. Traditional deep learning-based object detectors, such as Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet, offer high detection accuracy but require substantial processing power, making them less suitable for real-time applications on edge devices [

31,

32]. To address this limitation, lightweight object detectors have been developed to provide real-time performance with reduced computational overhead [

33].

Models like MobileNet-SSD [

34] leverage depthwise separable convolutions and parameter-efficient architectures to maintain detection accuracy while significantly lowering inference time. The YOLO family, particularly custom YOLO architectures specialized for efficient resource utilization [

35], has demonstrated promising results in mobile and embedded AI applications by reducing model complexity without drastically compromising performance. Similarly, EfficientDet [

36] employs a compound scaling strategy to optimize network depth, width, and resolution, making it a viable choice for medical imaging tasks where both precision and efficiency are crucial.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we detail the materials and methods employed in the development and evaluation of YOLO-Tryppa. First, in Section 3.1, we describe the acquisition, preparation, and annotation of the Tryp dataset, which comprises microscopy images of unstained thick blood smears. Next, Section 3.2 outlines the experimental setup, including the design of the detection framework and training strategies, with a comparison of single-stage and two-stage object detectors. Section 3.3 presents the metrics and procedures used to evaluate the robustness and accuracy of YOLO-Tryppa, focusing on standard object detection measures such as AP, AP50, and the F1 score. Lastly, Section 3.4 provides a detailed explanation of ghost convolution, an efficient computational technique integrated into the model for reducing complexity without compromising performance.

3.1. Dataset

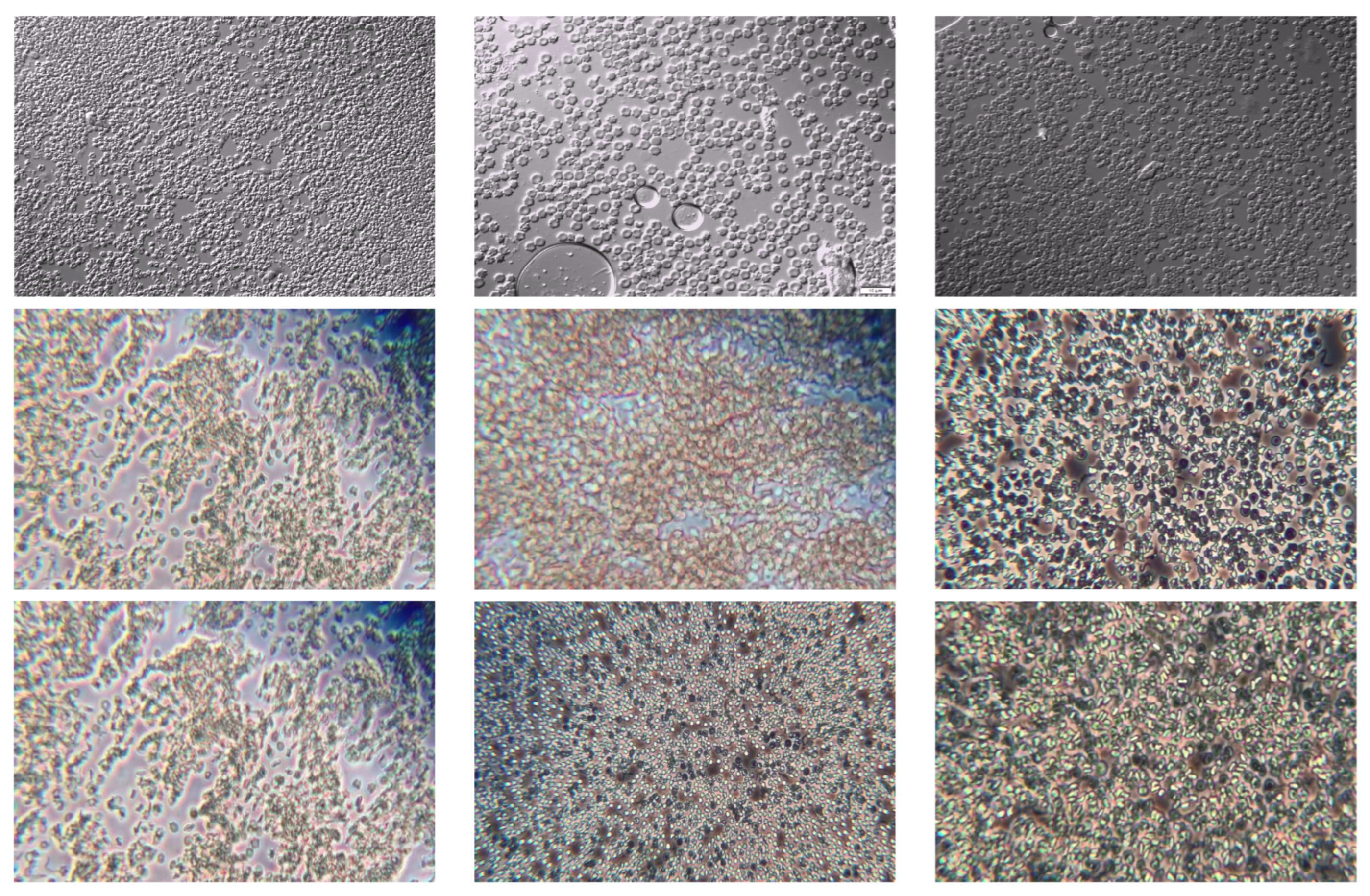

The Tryp dataset [

5] is, to the best of our knowledge, the first and most comprehensive collection of microscopy images of unstained thick blood smears specifically curated for the detection of Trypanosoma parasites. It comprises 3,085 annotated images of infected (positive) and 93 images from non-infected (negative) blood samples. The images were acquired using two different microscopy setups, namely, the IX83 inverted Olympus microscope and the Olympus CKX53 microscope, yielding varying resolutions:

,

, and

pixels.

Annotations, provided as tight bounding boxes around the parasite regions, were generated through a two-stage process using both Roboflow and Labelme, ensuring high consistency and quality. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets following a 60:20:20 ratio for the annotated images.

Figure 1 presents a representative selection of images from the dataset.

3.2. Object Detectors

Object detection methods in computer vision can be broadly categorized into single-stage and two-stage approaches, each offering distinct trade-offs between speed and accuracy. Single-stage detectors, such as YOLO [

3] and SSD [

37], perform object localization and classification in a single forward pass. This direct regression of bounding boxes and class probabilities from full images enables high processing speeds, making them suitable for real-time applications. However, this approach may sometimes compromise localization accuracy, particularly when detecting small or densely clustered objects. In contrast, two-stage detectors exemplified by architectures like Fast R-CNN [

8] and Faster R-CNN [

9] employ an initial stage to generate region proposals followed by a second stage that refines these proposals through classification and bounding box regression. Although this two-step process generally incurs higher computational costs and longer inference times, it tends to yield superior localization precision. The selection between these methods ultimately depends on the application’s specific requirements, balancing the need for speed against the demand for accuracy.

3.3. Detection Metrics

In evaluating detection performance, it is essential to quantify both the accuracy of object localization and the reliability of classification. Two standard metrics used in object detection are Average Precision (AP) and AP50. These metrics are built upon the concepts of True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). Here, TP represents correctly detected objects, FP corresponds to incorrect detections, and FN denotes objects that were missed by the detector. The decision on whether a predicted bounding box is a TP or an FP is based on the Intersection over Union (IoU) criterion, which measures the overlap between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth. An IoU threshold of 0.5 is typically employed, meaning that if the IoU exceeds 0.5, the detection is considered a match.

Average Precision quantifies the area under the precision-recall curve. Precision (

P) is defined as in the following Equation (1):

while recall (

R) is defined as in Equation (2):

Different pairs of precision and recall values are obtained by varying the detection confidence threshold, which can be plotted to form the precision-recall curve. The AP is then computed as defined in Equation (3):

where

is the precision as a function of recall. AP provides a comprehensive measure of detection performance, with higher values indicating a better balance between precision and recall.

AP50 is a specific case of AP where the IoU threshold is fixed at 0.5. This metric, denoted as AP50, evaluates detection performance under the condition that a predicted bounding box is considered a true positive if its IoU with a ground truth box is at least 0.5. AP50 is widely used because it offers a straightforward evaluation that balances localization and classification accuracy, making it a common baseline in object detection benchmarks.

To balance the trade-off between precision and recall, we compute the F1 score (F1). As defined in Equation (4), it is the harmonic mean between P and R:

3.4. Ghost Convolution

Ghost convolution is an innovative approach to reduce the computational cost of standard convolutional operations [

38]. Traditional convolutional layers generate a large number of output feature maps by applying numerous convolution kernels, many of which can be redundant. The core idea behind ghost convolution is that a significant portion of these feature maps can be approximated through inexpensive linear operations rather than computed directly via costly convolutions.

In practice, the process begins by applying a standard convolution to the input feature map to produce a compact set of intrinsic feature maps. These intrinsic maps capture the essential features of the input. Instead of directly computing all desired feature maps, ghost convolution synthesizes additional, or ghost, feature maps by applying a cheap linear transformation to the intrinsic features. This transformation is typically realized using operations such as depthwise convolutions.

Mathematically, if

X represents the input feature maps and

denotes the convolution kernels for generating the intrinsic feature maps, then the intrinsic features

are computed as in Equation (5):

Subsequently, an inexpensive linear operation

G is applied to

to generate the ghost features

, so that the final output

Y can be approximated (see Equation (6)) by:

This strategy preserves the essential information captured by the intrinsic features and enriches the representation with additional details while significantly reducing the number of parameters and floating-point operations required. The result is a more efficient convolutional layer that maintains performance while offering substantial computational savings.

3.5. The Proposed Architecture: YOLO-Tryppa

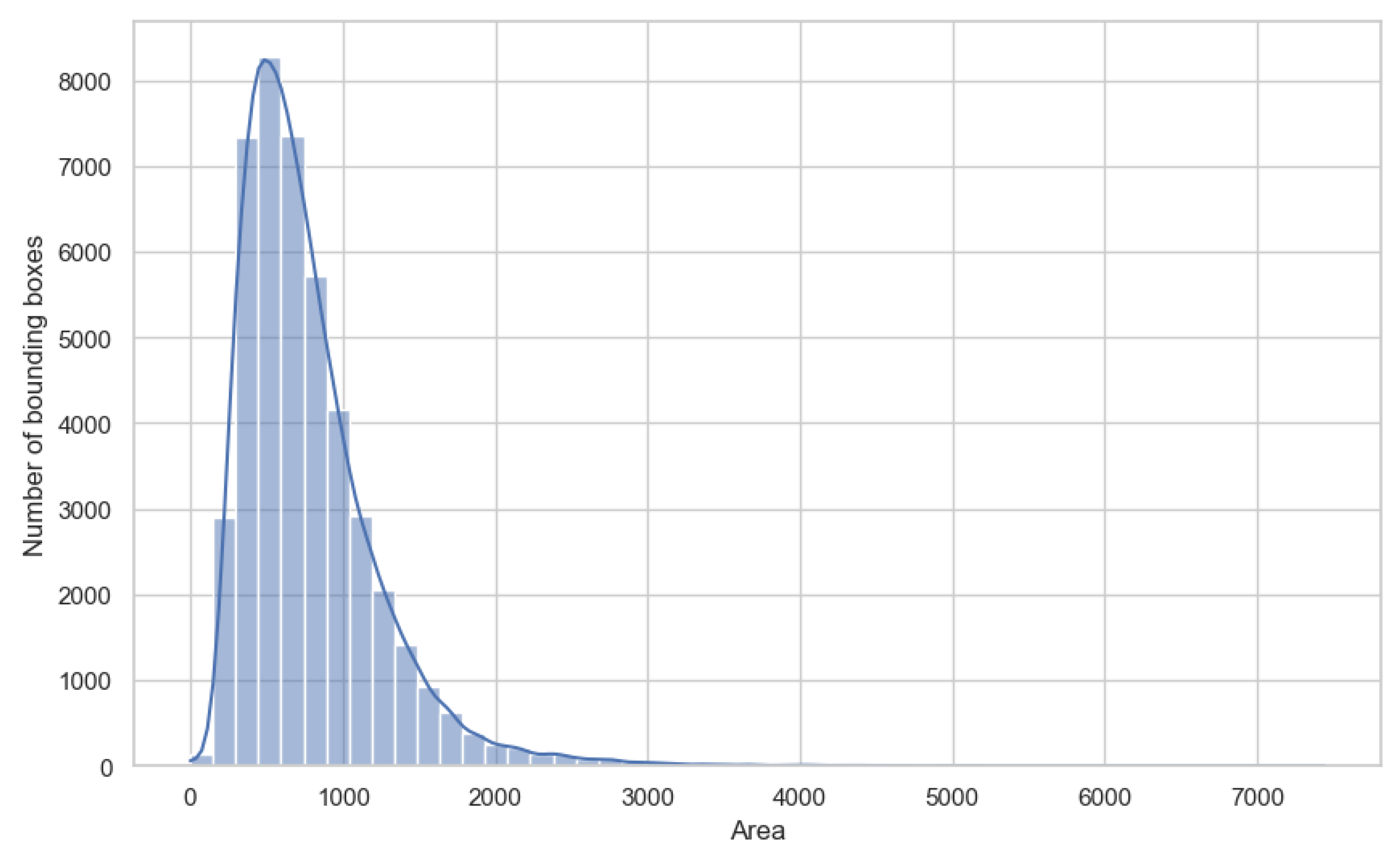

Our efforts in designing the YOLO-Tryppa architecture were directed toward two primary objectives: first, to enhance the localization of small parasites in blood smear images, and second, to develop models that are both lightweight and capable of real-time performance. To justify the first objective, we present in

Figure 2 the area distribution following the COCO standard [

39]. The distribution clearly reveals a bias toward small objects, with

of the objects classified as small having an area less than

pixels and the remaining

classified as medium-sized with areas between

and

pixels.

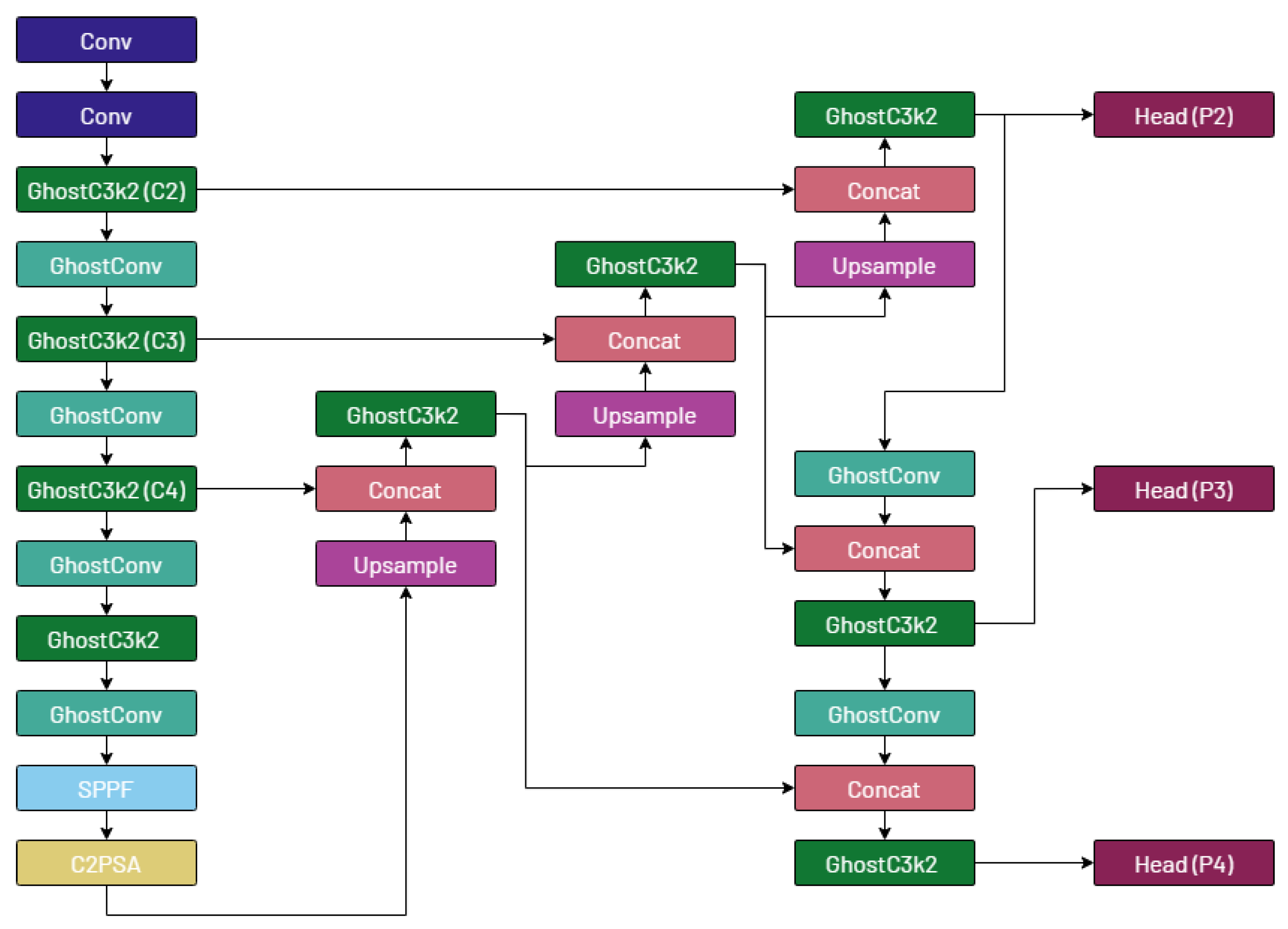

Building upon our previous work [

4], detectors for small parasites require the use of the lower layers of the backbone in the chosen base architecture. However, doing so increases the number of parameters in the specialized architectures due to additional prediction heads and a higher number of GFLOPs. Therefore, to build our YOLO-Tryppa, we start from the YOLOv11m architecture, which offers a reliable trade-off between performance and real-time capabilities [

40].

We then substitute all convolutional layers in the model architecture, including submodules, with ghost convolutions except for the first two layers, similarly to the work of Cao et al. [

35]. Next, we add a prediction head called

P2 and introduce a novel branch stemming from the

C2 feature map [

3] that is specialized for detecting small objects. Finally, we remove the

P5 prediction head, which is designed for larger objects that are absent from the considered dataset.

The proposed YOLO-Tryppa architecture is visually represented in

Figure 3.

4. Experimental Evaluation

This section presents the full range of experiments performed toward a reliable and fast Trypanosoma detection. Specifically, in Section 4.1, we detail the experimental setup, including the hardware, training parameters, and the optimization techniques used. Section 4.2 provides a comprehensive evaluation of detection performance across different YOLO architectures, highlighting the comparative advantages of YOLO-Tryppa. Section 4.3 presents an ablation study to isolate and analyze the impact of individual architectural components on model performance. Finally, Section 4.4 presents qualitative results that visually demonstrate the effectiveness of YOLO-Tryppa in detecting Trypanosoma parasites under challenging conditions, complementing quantitative evaluations.

4.1. Experimental Setup

Our experiments were performed on a workstation featuring an RTX 4060 Ti GPU with 16GB of VRAM and an Intel Core i5-13400 processor. Each model was trained for 40 epochs using a learning rate of

, and the best-performing models were selected based on the highest AP score on the validation set. A batch size of 16 was used for training each model, except for the YOLO Para architecture. Due to memory constraints for the YOLO Para variants, a batch size of 1 was employed. The YOLO-Tryppa architecture was developed using the Ultralytics repository [

3]. We also included the original YOLOv11 augmentation setup and kept the image size to match the COCO standard of

. For optimization, we combined the AdamW optimizer with the original YOLOv11 loss, incorporating three components: distributed focal loss, bounding box regression loss, and class probability loss. Its loss is defined in Equation (7):

where

quantifies the difference between predicted and true class probabilities via cross-entropy, ensuring accurate categorization,

minimizes the error between predicted and actual bounding boxes using metrics like IoU, and

adjusts weights for challenging samples to improve detection accuracy. The model’s multi-stage design further refines feature extraction for superior object detection [

41].

4.2. Experimental Results

To ensure fairness and comparability across experiments, we first train both the large and medium-sized YOLO architectures (versions 5, 8, and 11) using the same experimental setup as our proposed YOLO-Tryppa architecture. This strategy was adopted not only to maintain fairness but also to investigate whether increasing the number of parameters and, consequently, the complexity and size of the models can lead to enhanced detection performance. The full range of analyzed metrics and experiments is depicted in

Table 1.

Our experiments reveal that the larger counterpart exhibits inferior performance for each off-the-shelf model. Notably, YOLOv8 displays the most significant variability, with the medium-sized model achieving an AP50 of

compared to only

for the large model. Nonetheless, the baseline models outperform the other three architectures, RetinaNet, Faster R-CNN, and YOLOv7, by

in terms of AP50. It is important to note that both RetinaNet and Faster R-CNN used a larger image size of

in the previous state-of-the-art approach [

5].

Similarly, the results obtained with the YOLO Para models follow trends analogous to those of the off-the-shelf models while surpassing the highest-scoring YOLOv8m and YOLOv11m. In particular, the YOLO Para SP architecture reaches an AP50 of . However, YOLO Para models are characterized by approximately four times the GFLOPs compared to the two best off-the-shelf models.

Finally, YOLO-Tryppa emerges as the best-performing model in terms of AP50, achieving a score of . Remarkably, it requires only million parameters, the lowest among the selected architectures, and GFLOPs, despite incorporating the computationally demanding P2 prediction head.

4.3. Ablation Study

An ablation study was conducted using the YOLOv11m baseline as a reference to evaluate the impact of individual architectural components.

Table 2 summarizes the changes in the AP50 metric resulting from our proposed key modifications. Starting from the YOLOv11m baseline AP50 of

, replacing standard convolution layers with ghost convolutions slightly reduced the AP50 to

, despite significantly lowering the parameter count and GFLOPs. In contrast, adding the dedicated

P2 prediction head, specifically designed to improve the detection of small objects, increased the AP50 to

. Further changes, such as integrating a CBAM [?] module or adding a

P1 prediction head for extremely small objects, caused a decline in performance. Consequently, the final YOLO-Tryppa architecture, which incorporates ghost convolutions, the

P2 prediction head, and the removal of the

P5 prediction head—without the additional CBAM or

P1 head—delivers the best balance. This configuration achieves an AP50 of

, the lowest parameter count, and reduced computational complexity. These results highlight that carefully selecting and refining architectural components can significantly enhance the detection of small Trypanosoma parasites.

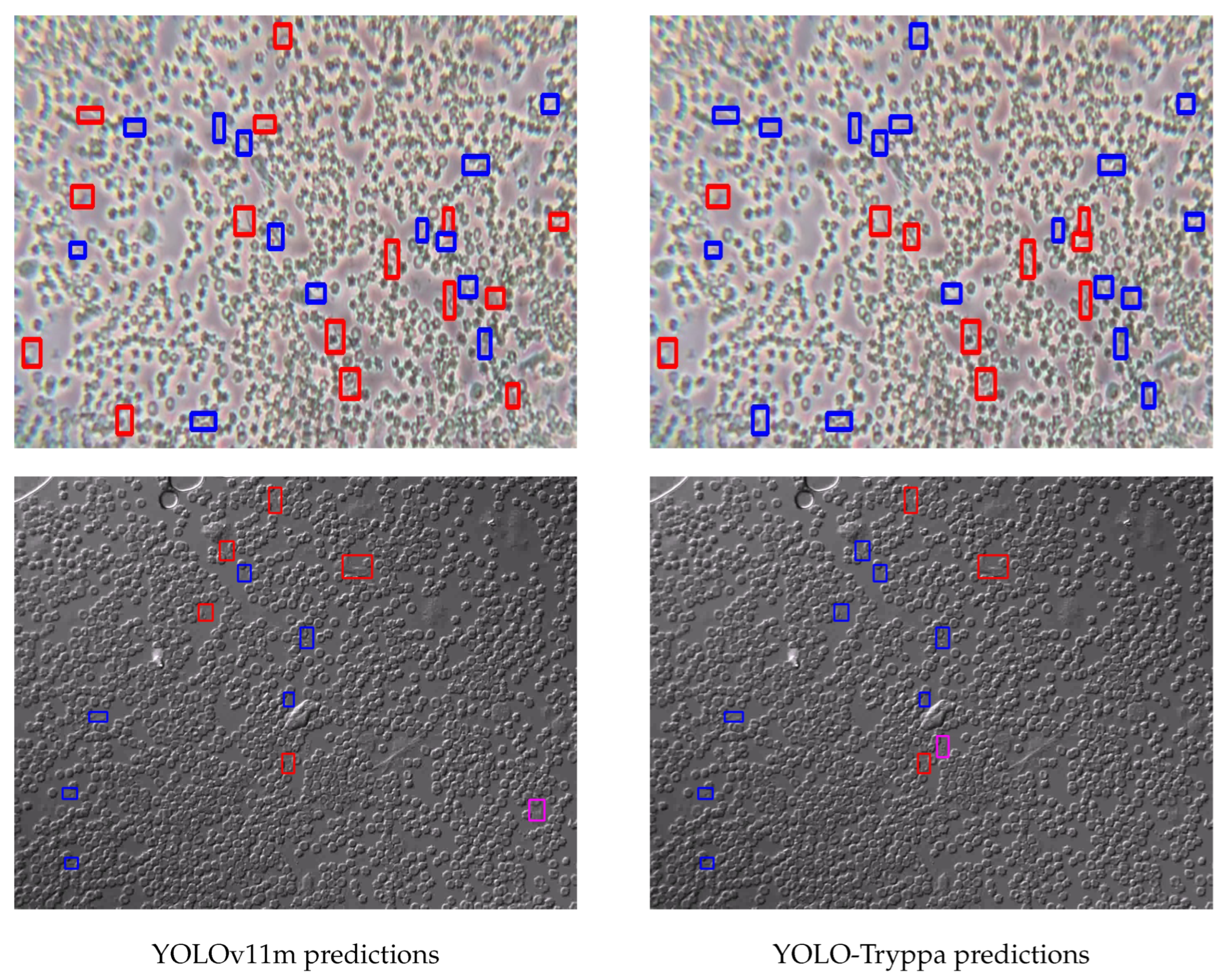

4.4. Qualitative Results

In addition to quantitative evaluations, we present a qualitative analysis to further demonstrate the effectiveness of YOLO-Tryppa.

Figure 4 presents representative examples where the model successfully localizes Trypanosoma parasites under challenging conditions, including low contrast, overlapping structures, and noisy backgrounds. These results demonstrate the model’s ability to capture subtle localized features, primarily enabled by the dedicated

P2 prediction head, which reduces FPs and ensures precise detection.

A clear trend emerges from the examples: while both models tend to under-predict, YOLO-Tryppa consistently outperforms its off-the-shelf counterparts by detecting a higher number of parasites. This improvement is visually apparent in

Figure 4 and quantitatively supported by the highest recall score.

5. Limitations

The proposed YOLO-Tryppa framework, while demonstrating improved performance in detecting small Trypanosoma parasites, has several inherent limitations. One notable constraint is the limited diversity and scale of the Tryp dataset, which may not fully capture the broad variability encountered in real-world clinical samples. Additionally, substituting standard convolutional layers with ghost convolutions, although effective in reducing computational cost, can compromise the model’s ability to capture complex feature details in highly challenging imaging conditions. The current architecture’s performance under extreme noise, significant variations in parasite morphology, or scenarios with overlapping structures remains to be further validated. Future research should consider integrating more robust data augmentation techniques and additional architectural refinements to address these challenges and improve the overall generalizability of the model.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, YOLO-Tryppa represents a significant advancement in the automated detection of Trypanosoma parasites in microscopy images. By leveraging ghost convolutions and a dedicated P2 prediction head, the framework achieves a balanced trade-off between high detection accuracy and computational efficiency, outperforming several baseline models while maintaining a low parameter count and GFLOPs. The experimental results underscore the potential of this tailored deep learning approach in addressing critical challenges in medical diagnostics, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Despite the limitations noted, the promising outcomes of YOLO-Tryppa encourage future enhancements and its integration into clinical workflows, ultimately contributing to more rapid and reliable disease screening and improved patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z., D.A.M.; methodology, L.Z., A.L.,D.A.M.; Investigation, L.Z., A.L., D.A.M. and C.D.R.; software, L.Z., D.A.M.; writing—original draft, L.Z., A.L. ,D.A.M.; writing—review and editing, L.Z., A.L., D.A.M. and C.D.R.; supervision, A.L., C.D.R.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.5 - Call for tender No.3277 published on December 30, 2021 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU. Project Code ECS0000038 - Project Title eINS Ecosystem of Innovation for Next Generation Sardinia - CUP F53C22000430001- Grant Assignment Decree No. 1056 adopted on June 23, 2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR). This work has also been partially supported by the project DEMON, “Detect and Evaluate Manipulation of ONline information,” funded by MIUR under the PRIN 2022 grant 2022BAXSPY (CUP F53D23004270006, NextGenerationEU), and by project SERICS (PE00000014) under the NRRP MUR program funded by the EU-NGEU (NextGenerationEU).

Data Availability Statement

All the material used and developed for this work is available at the following

GitHub repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NTDs |

Neglected tropical diseases |

| CNNs |

Convolutional neural networks |

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| CAD |

Computer-aided diagnostic |

| AP |

Average Precision |

| TP |

True Positives |

| FP |

False Positives |

| FN |

False Negatives |

| P |

Precision |

| R |

Recall |

References

- Matthews, K.R. The developmental cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei. Journal of cell science 2005, 118, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanase, J.; Triantaphyllou, E. A systematic survey of computer-aided diagnosis in medicine: Past and present developments. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 138, 112821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J.; Chaurasia, A. Ultralytics YOLO.

- Zedda, L.; Loddo, A.; Di Ruberto, C. A deep architecture based on attention mechanisms for effective end-to-end detection of early and mature malaria parasites in a realistic scenario. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2025, 186, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzaku, E.T.; Mohammed, M.A.; Ozbulak, U.; Won, J.; Hong, H.; Krishnamoorthy, J.; Van Hoecke, S.; Magez, S.; Van Messem, A.; De Neve, W. Tryp: a dataset of microscopy images of unstained thick blood smears for trypanosome detection. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, A.; Singh, Y.; Neeru, N.; Kaur, L.; Singh, A. A Survey on Deep Learning Approaches to Medical Images and a Systematic Look up into Real-Time Object Detection. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 29, 2071–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 1409.1556 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, jun 2014; pp. 580–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates, Inc., Vol. 28. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, L.; Domingues, I.; Mendes, M. Study on Data Partition for Delimitation of Masses in Mammography. Journal of Imaging 2021, 7, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, 2017. IEEE Computer Society, 2017, October 22-29; pp. 2999–3007. [CrossRef]

- Sora-Cardenas, J.; Fong-Amaris, W.M.; Salazar-Centeno, C.A.; Castañeda, A.; Martínez-Bernal, O.D.; Suárez, D.R.; Martínez, C. Image-Based Detection and Classification of Malaria Parasites and Leukocytes with Quality Assessment of Romanowsky-Stained Blood Smears. Sensors 2025, 25, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumarran, D.; Hasikin, K.; Khairuddin, A.S.M.; Ngui, R.; Sulaiman, W.Y.W.; Vythilingam, I.; Divis, P.C.S. An optimised YOLOv4 deep learning model for efficient malarial cell detection in thin blood smear images. Parasites & Vectors 2024, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Jha, M.; Bodapati, S.; Mishra, A.; Chetty, G.; Sahu, P.K.; Mohanty, S.; Padhan, T.K.; Mattoo, J.; Hukkoo, A. Deep Learning for Real-Time Malaria Parasite Detection and Counting Using YOLO-mp. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 102157–102172, Conference Name: IEEE Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, J.; Bonnet, C.; Bauchet, L.; Berteaud, E.; Gruber, A.; Loiseau, H.I.; Engelhardt. Epidemiology of meningiomas. Neuro-Chirurgie 2014, 64, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pépin, J.; Méda, H. The epidemiology and control of human African trypanosomiasis. In Advances in Parasitology; Academic Press, 2001; Volume 49, pp. 71–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetari, R.; Ayari, H.; Sakly, H. Computer-aided diagnosis systems: a comparative study of classical machine learning versus deep learning-based approaches. Knowledge and Information Systems 2023, 65, 3881–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrick, N.; Sahiner, B.; Armato, S.G.; Bert, A.; Correale, L.; Delsanto, S.; Freedman, M.T.; Fryd, D.; Gur, D.; Hadjiiski, L.; et al. Evaluation of computer-aided detection and diagnosis systems. Medical Physics 2013, 40, 087001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnussairi, M.H.D.; İbrahim, A.A. Malaria parasite detection using deep learning algorithms based on (CNNs) technique. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2022, 103, 108316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, Anita Kumar, P. DLRFNet: deep learning with random forest network for classification and detection of malaria parasite in blood smear. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Silva, D.; Milagre, M.; Oliveira, M.; Pereira, T.; Silva, J.; Costa, L.; Minoprio, P.; Junior, R.; Gazzinelli, R.; et al. Automatic detection of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in blood smears using a machine learning approach applied to mobile phone images. PeerJ 2022, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, T.; Anzaku, E.T.; Özbulak, U.; Magez, S.; Van Messem, A.; De Neve, W. Automatic Detection of Trypanosomosis in Thick Blood Smears Using Image Pre-processing and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Human Computer Interaction; Singh, M., Kang, D.K., Lee, J.H., Tiwary, U.S., Singh, D., Chung, W.Y., Eds.; Cham, 2021; pp. 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kittichai, V.; Sompong, W.; Kaewthamasorn, M.; Sasisaowapak, T.; Naing, K.M.; Tongloy, T.; Chuwongin, S.; Thanee, S.; Boonsang, S. A novel approach for identification of zoonotic trypanosome utilizing deep metric learning and vector database-based image retrieval system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, O.B.; Saleem, Y. CSA-Net: Channel and Spatial Attention-Based Network for Mammogram and Ultrasound Image Classification. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2021, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10-17 October 2021; IEEE, 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc., 2017; Vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.; Zhang, Y. A Unifying Framework of Attention-Based Neural Load Forecasting. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51606–51616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, V.; Renuka, A. Deep learning based object detection for resource constrained devices: Systematic review, future trends and challenges ahead. Neurocomputing 2023, 531, 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, F.; Ahmad, S.; Whangbo, T.K. Object detection based on deep learning techniques in resource-constrained environment for healthcare industry. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), feb 2022; pp. 1–7699, ISSN 2767-7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Luo, S.; Han, K.; Yuan, B.; DeMara, R.F.; Bai, Y. An Efficient Real-Time Object Detection Framework on Resource-Constricted Hardware Devices via Software and Hardware Co-design, 2024. arXiv:2408. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, R.; Fatima, I.; Prasad, L.A. A Survey on Real-Time Object Detection Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conferenceon Advances in Electronics, Communication, Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICAECIS), apr2023; pp. 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K. RTMDet: An Empirical Study of Designing Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.07784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, M.; Meng, X.; Xiao, W.; Ju, Q. RefineDetLite: A Lightweight One-stage Object Detection Framework for CPU-only Devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, jun 2020; pp. 2997–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision - ECCV 2016 - 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11-14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I; Leibe, B.; Matas, J.; Sebe, N.; Welling, M., Eds.. Springer, 2016; Vol. 9905, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bao, W.; Shang, H.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, Q. GCL-YOLO: A GhostConv-Based Lightweight YOLO Network for UAV Small Object Detection. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision - ECCV 2016 - 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11-14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer, 2016; 9905, pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, jun 2020; pp. 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1405.0312[cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, K.; Fang, T.; Su, L.; Chen, R.; Fei, X. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation of YOLOv11, YOLOv10, YOLOv9, YOLOv8 and YOLOv5 on Object Detection of Power Equipment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).