1. Introduction

In settlement areas, urbanization has converted natural permeable land into impervious cover. The amount of impervious land in urban areas ranges from 20% in residential areas to as much as 85% in commercial areas [

1]. These areas, such as parking lots, concrete roads, and cemented surfaces, prevent infiltration of water through the soil. Such process has significant impact on numerous biotic and abiotic components in the environment including watershed hydrology and water resources quality [

2]. In streams, these impacts include higher peak stream flows which increases channel incision, bank erosion, and increased transport of sediment and other nonpoint pollutants [

3]. Urban stormwater runoff in the United States of America is the leading concern of water quality impairment and it is also the third largest source of water impairment overall [

4]. Urbanization's extensive transformation of natural landscapes into impervious surfaces underscores the urgent need to address the environmental challenges associated with urban stormwater runoff, particularly its profound effects on hydrology and water quality.

Stormwater runoff mainly consists of suspended solids, heavy metals and chlorides, while it may also contain oil, grease and other related hydrocarbons [

5]. Heavy metals in stormwater are products of vehicular emission and industrial activities. They can be found in one to two order magnitudes greater than sewage effluent [

6]. The sources of heavy metals in vehicular emissions include lead deposits from lead oxides, zinc from tire wear; copper, chromium and nickel from the wear of the plating, bearings, brake linings and other moving parts of the vehicle [

7]. Roofing materials can also be significant sources of these pollutants, depending on the type of roofing material and atmospheric deposition parameters [

8,

9]. The impacts of urban storm runoff on the receiving water bodies depend on the ambient quality of the receiving water and the quantity of the water pollutants entering that water body [

10]. Lead typically accumulates in stream sediments and can affect fish survival, growth, and reproduction [

11]. Zinc and copper at certain concentrations are toxic to fish and macroinvertebrates as well [

12]. Cadmium and chromium are mutagenic and carcinogenic to aquatic life [

13]. Excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus causes algal blooms, which can increase algal turbidity thus blocking sunlight and decay of excess biomass can consume stream dissolved oxygen [

14]. Oil and grease can affect fish reproduction. Sediment particles deposited by storm runoff or resulting from channel erosion can endanger fish survival and reproduction [

15], it can cover the stream bottom reducing available spawning habitat [

16]. Therefore, the diverse pollutants in stormwater runoff, including heavy metals, hydrocarbons, nutrients, and sediments, pose significant ecological threats to aquatic ecosystems, underscoring the critical need for effective mitigation strategies to protect water quality and aquatic life.

Eastern Texas’s unique geographic location, influencing by movements of seasonal air masses, including subtropical west winds, tropical storms, and a subtropical high-pressure system, makes it is prone to hurricane [

17]. During recent decades, such extreme precipitation event has increased in its frequency and intensity in eastern Texas [

18], leading to heave storm and flooding risk has been more dramatically [

19]. These climatic trends exacerbate the impacts of urbanization on watershed hydrology and water resources, as increased impervious cover amplifies stormwater runoff and diminishes natural infiltration processes [

20]. Elevated runoff volumes overwhelm stormwater infrastructure, increasing the risk of flash flooding and pollutant transport into receiving water bodies. This has profound implications for water quality, including the introduction of heavy metals, nutrients, and sediments, which degrade aquatic habitats and threaten biodiversity. Furthermore, the altered hydrologic regime contributes to stream channel instability, erosion, and sedimentation, further impacting watershed health.

Rain gardens, a best management practice (BMP), mitigate urban stormwater impacts by enhancing infiltration, reducing runoff, and improving water quality [

21,

22,

23]. These shallow, vegetated depressions capture and retain stormwater for infiltration, aquifer recharge, pollutant removal, and peak flow reduction [

24]. Their design includes runoff conveyance, pretreatment, treatment, and maintenance [

25] while mimicking natural hydrologic processes such as infiltration, filtration, adsorption, and decomposition (Prince George’s County Department of Environmental Sciences, 1993). Additionally, their vegetation provides both functional hydrological benefits and aesthetic value (Dietz and Clausen, 2005).

Over the past two decades, numerous studies have demonstrated the multifunctional benefits of rain gardens, including improving microclimate, enhancing urban biodiversity by supporting plants and insects, and contributing to air quality improvement [

26]. Recent research has focused on optimizing rain garden designs to enhance pollutant removal efficiency, such as implementing two-stage tandem rain gardens for improved retention [

27], integrating polyculture plantings to increase pollutant removal rate [

28], and modifying soil fauna to enhance microbial activity and pollutant breakdown [

29]. These advancements highlight the ongoing efforts to refine rain garden functionality, making them more effective and adaptable for sustainable urban stormwater management.

Despite extensive research on BMPs, rain garden studies in recent five years are more focus on temperate regions [

30]. However, their application in regions prone to extreme precipitation events, such as the subtropical climate of eastern Texas, remains underexplored. Given the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events in this area, evaluating the performance of rain gardens in such environments is critical to understanding their effectiveness under variable hydrological conditions.

Thus, the main purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of raingardens as structural BMPs by measuring the surface runoff water quality in eastern Texas, USA. We hypothesized that 1) Rain gardens effectively reduce pollutant concentrations in stormwater runoff; 2) Variations in pollutant removal efficiency are influenced by site-specific factors such as soil composition and local geology. By this, we measured stormwater runoff from parking lots and buildings for various water quality parameters, including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), fluoride (F-), chloride (Cl-), nitrate (NO3), nitrite (NO2), phosphate (PO4), sulfate (SO4), salts, carbonates, bicarbonates, sodium (Na), potassium (K), aluminum (Al), boron (B), calcium (Ca), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), copper (Cu) iron (Fe) lead (Pb) magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn), before it entered the rain gardens. After flowing through the rain garden, we measured water quality was again to determine the effectiveness of rain gardens in reducing/ treating NPS pollutants in urban stormwater runoff.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

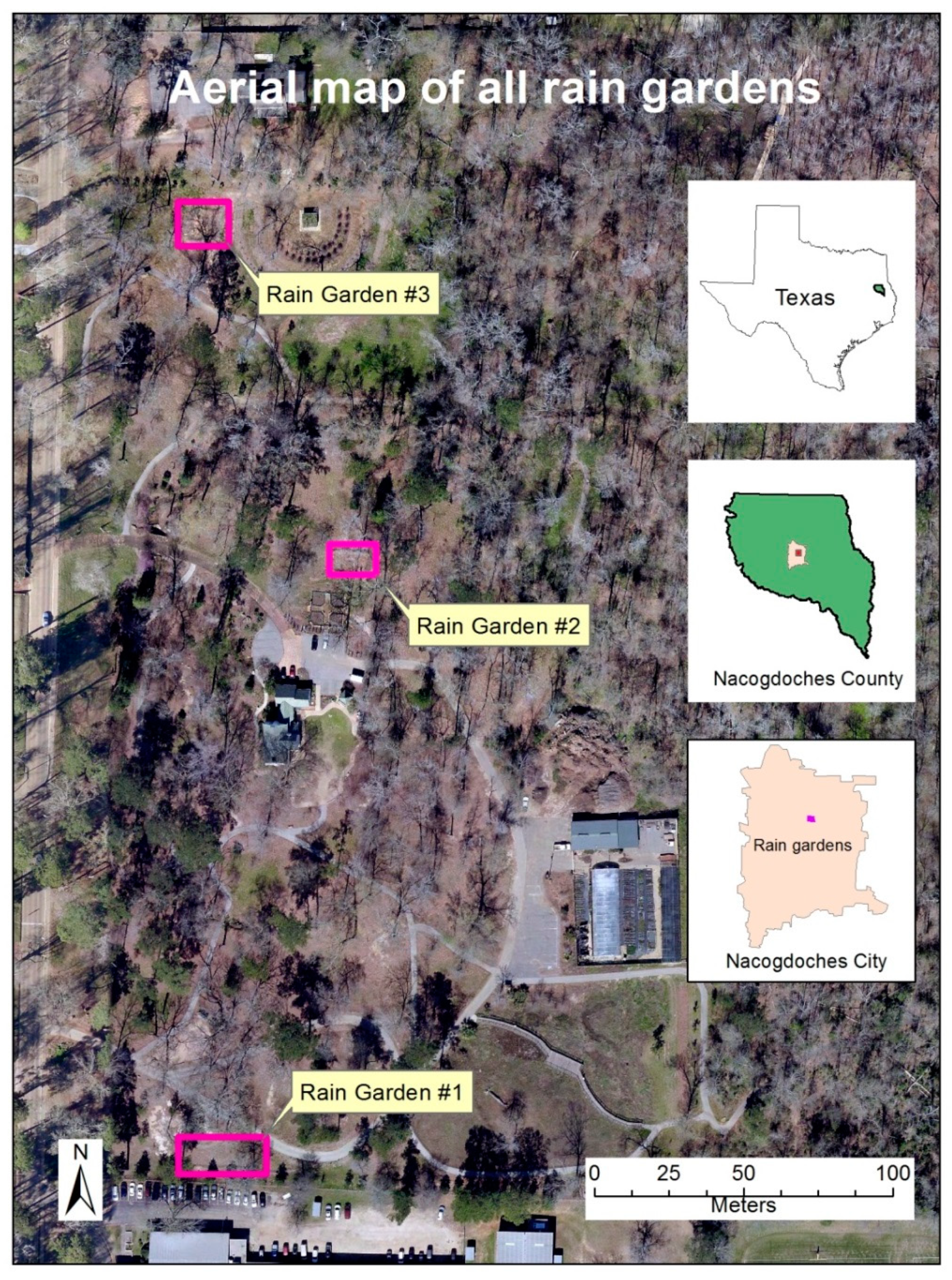

The study was conducted at the Pineywoods Native Plant Center (PNPC), located on the northern edge of Stephen F. Austin State University (SFASU) in Nacogdoches, Texas, USA (31° 36' 11"N; 94° 39' 19" W). The PNPC spans 17 hectares and consists of a mix of uplands, mesic mid-slopes, and wet creek bottomlands. The area has a humid subtropical climate, characterized by hot summers and cool winters. Annual rainfall is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year, with April and May receiving the highest precipitation.

The primary contributing areas to the three rain gardens are upgradient parking lots and building rooftops (

Figure 1). Each rain garden was designed to accommodate runoff from different infrastructure types and varied in size. Rain Garden 1 primarily receives runoff from the Raguet Elementary School parking lot, while Rain Garden 2 is supplied with runoff from the main office parking lot of the PNPC. Rain Garden 3 receives runoff from the Music Preparatory building parking lot at SFASU.

Rain garden 1 is located on the soil of Attoyac-urban land complex (soil unit 8) with 0–4% slopes [

31]. The major soil components include 40% urban land, 40% Attoyac and similar soils, and 20% minor components. The parent material consists of loamy alluvium with a moderately high to high saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) of 1.45–5.03 cm/hr. Rain Garden 2 is situated on Trawick-Urban Land Complex soils (Soil Unit 65) with 8–20% slopes. The major soil components include 55% Trawick and similar soils, 30% urban land, and 15% minor components. The parent material is clayey residuum weathered from glauconite and sandstone. The Ksat is moderately high (0.51–1.45 cm/hr.), and the available water capacity is low (14.22 cm). Rain Garden 3 is located on a combination of Nacogdoches-Urban Land Complex soils (Soil Unit 47) and Trawick-Urban Land Complex soils (Soil Unit 65). For Soil Unit 47, the composition consists of 45% Nacogdoches and similar soils, 35% urban land, and 20% minor components. The parent material is clayey residuum weathered from glauconite sandstone. The Ksat is moderately high (0.51–1.45 cm/hr.), and the available water capacity is 22.61 cm.

2.2. Rain Garden Design

The contributing area for each rain garden was determined through site evaluation and geospatial hydrological analysis. Rain gardens were constructed in accordance with the Knox County, Tennessee Stormwater Management Manual, prepared by AMEC Earth & Environmental Inc. [

22]. Based on the guidelines outlined in this manual, the contributing areas for each rain garden were calculated to ensure optimal stormwater retention and treatment capacity (

Table 1).

2.3. Structural Design

The flow of stormwater through a rain garden treatment system, beginning at the parking lot, serves as the primary source of runoff. The runoff water passed through multiple structures within the rain gardens before reaching the outflow, where treated water was collected for quality analysis. The first component of the system was an instrument box equipped with a Thermo Scientific® 1000 mL HDPE Nalgene® stormwater sampler and a Hobo® U24-001 temperature and conductivity data logger. An untreated runoff from the parking lot was first collected in the water sampler inside the instrument box for analysis before entering the rain garden for treatment.

A 0.15 m drainage pipe transported water from the pre-treatment instrument box into the rain garden, where it flowed onto the surface and temporarily pooled within a designated ponding zone, enclosed by a 0.25 m high berm. This area was planted with native eastern Texas vegetation; however, nitrogen-fixing plants were intentionally excluded from both the rain garden and the surrounding berm. The stormwater then infiltrated through the mulch and sand layers, where natural treatment processes such as sedimentation, adsorption, and microbial activity occurred.

Water percolating through these layers accumulated at the base of the rain garden and was directed through a series of 0.1 m drainage pipes before reaching the outflow instrument box. The outflow structure was equipped with the same sampling and monitoring equipment as the inflow, ensuring consistency in data collection for water quality analysis.

2.4. Cross Sectional Structure

The cross-sectional area of the rain gardens is divided into two major zones: the rooting zone and the drainage zone, comprising five distinct structural elements. The rooting zone consists of a mulch layer and sand layer. The mulch layer, approximately 0.15 m thick, is composed of dry leaves and finely shredded hardwood chips applied uniformly. This layer serves multiple functions, including filtering pollutants, preventing soil erosion, and supporting microbial activity for pollutant degradation. Beneath the mulch layer, the 0.9 m sand layer acts as an infiltration medium, slowing runoff and promoting water percolation.

The drainage zone, located below the rooting zone, consists of three key layers: filter fabric, gravel, and perforated pipes. The filter fabric separates the rooting and drainage zones, providing additional filtration while acting as a root barrier and preventing organic matter from clogging the drainage system. Below this, a 0.2 m pea gravel bed (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) enhances stormwater storage capacity and prevents waterlogging in the upper layers. At the bottom, 0.1 m perforated drainage pipes, spaced 0.9 m apart, facilitate passive gravity drainage. These pipes are connected to a main discharge pipe that directs treated stormwater downgradient.

A selection of native plants, including Echinacea purpurea, Tradescantia humilis, Scutellaria ovata, Salvia lyrate, Phlox divaricate, and Chasmanthium latifolium, were planted in the rain gardens due to their low maintenance requirements, pollutant uptake capacity, and adaptability to local growing conditions. These species also provide habitat and food sources for native fauna while enhancing the visual appeal of the rain gardens. No nitrogen-fixing plants were included, ensuring that nitrogen levels in the system were influenced solely by the soil and incoming stormwater.

2.5. Water Sample Collection

Water samples were collected in Thermo Scientific® 1000 ml HDPE Nalgene® stormwater sampler installed in the inflow and outflow collection boxes. Water collected in each bottle was transferred to a sample bottle which was then brought to the laboratory for chemical analyses. The water sampler inside the mounting kit automatically shuts off using a ball float valve after the bottle is full thus preventing dilution with later runoff.

Water samples collected from the rain gardens were taken to the SFASU Soil, Plant and Water Analysis Laboratory for preservation and analyses. Individual samples were analyzed for water quality parameters including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), fluoride (F-), chloride (Cl-), nitrate (NO3), nitrite (NO2), phosphate (PO4), sulfate (SO4), salts, carbonates, bicarbonates, sodium (Na), potassium (K), aluminum (Al), boron (B), calcium (Ca), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), copper (Cu) iron (Fe) lead (Pb) magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn).

2.6. Conductivity and Temperature Measurement

Electrical conductivity and temperature were measured in the rain garden using a Hobo® U24-001 temperature and conductivity data logger. The loggers were placed inside the instrument box along with the mounting kit. and recorded conductivity standardized to 25°C. Data were offloaded after each qualifying event using a HOBO® waterproof shuttle (U-DTW-1).

2.7. Raingarden Soil Sampling

During the construction process, all three rain gardens were filled with material from the same source. However, an evaluation was necessary to ensure that the difference in performance among rain gardens was not attributable to variations in soil materials. Therefore, soil samples were randomly collected from the mulch layer and the top 30 cm of the sand layer. A total tissue digestion method was used to analyze the samples for nutrients and various metals. To analyze the difference in the soil of the rain gardens, an ANOVA test was performed. All normally distributed soil data were analyzed using the F- test (α = 0.05) and non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis’s test (α = 0.05).

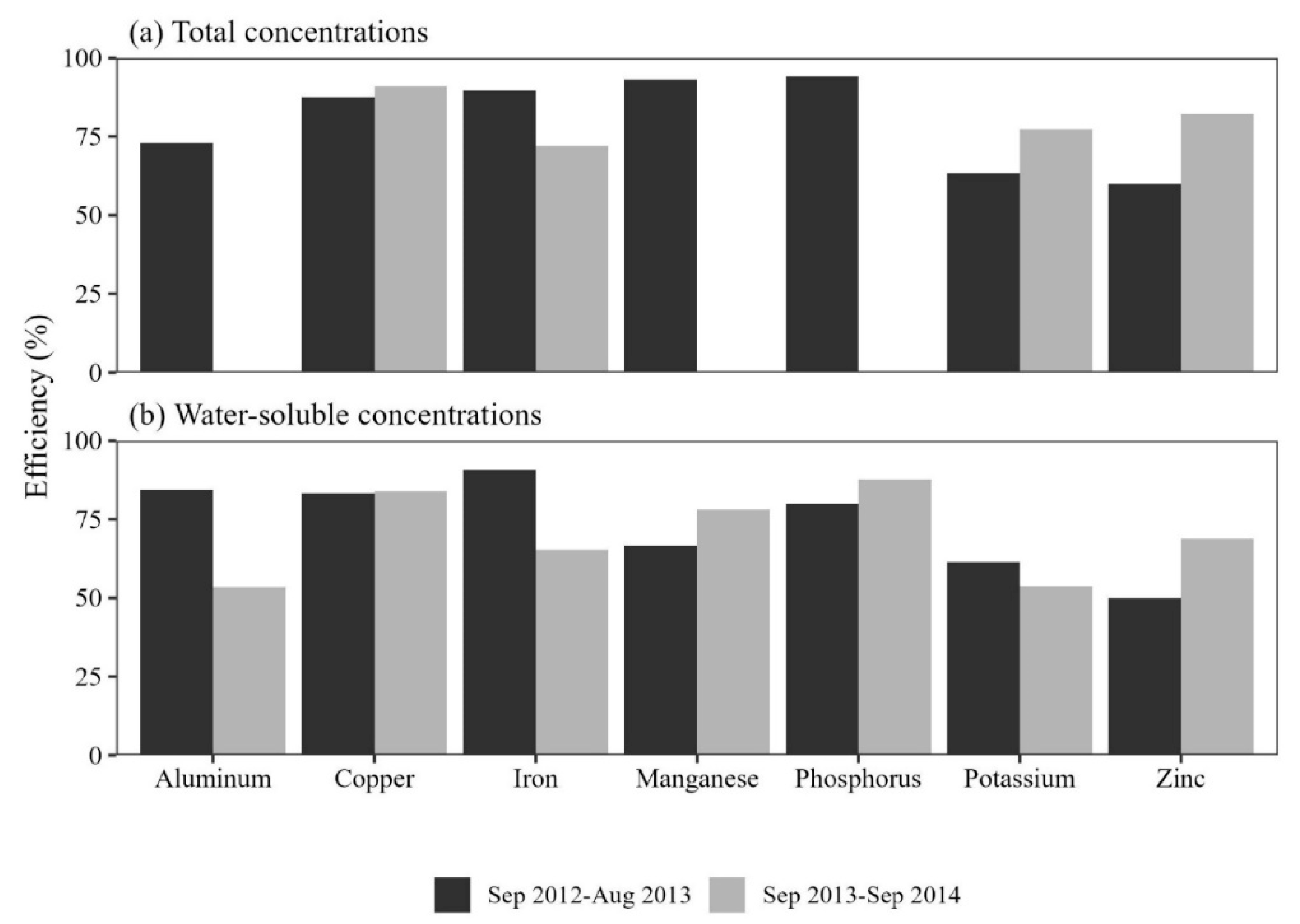

2.8. Sample Period Analysis

Two distinct sample periods were evaluated. The first period ranged from September 2012 to August 2013. This period signified the time immediately following construction. During this interval, it was anticipated that the performance of the rain garden would be non-representative as the vegetation was not fully established [

21]. The second period extended from September 2013 through September 2014. This represented the first year after vegetation establishment. The results presented herein focus on the second period, although comparisons are made with the first period to evaluate overall performance of the rain gardens [

32].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for water quality parameters by rain garden. The water quality parameters before and after stormwater enters the rain garden were compared. Parameter concentrations were compared with the water quality standards established by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and USEPA. The Shapiro-Wilks test for normality was conducted prior to performing any other statistical test. If the water sample data were normally distributed, then a parametric test (paired t-test) was conducted between contrasting rain gardens. For all non-normally distributed water sample data, the non-parametric Kruskal-Walli’s test was performed (α = 0.05). For concentrations below the method detection limit for a given chemical analysis, one-half of the method detection limit was utilized for calculation and statistical analysis. Pollutant removal efficiency was also evaluated and calculated for the rain gardens using the Formula (1):

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of rain gardens in managing non-point source pollution in eastern Texas by analyzing water quality parameters at inflow and outflow points. Results showed that the rain gardens significantly reduced the concentrations of aluminum, copper, iron, potassium, zinc, boron, manganese, phosphorus, fluoride, and phosphate at the outflow, achieving a pollutant removal efficiency exceeding 50%. Similar removal efficiencies have been reported in rain garden systems, including one in Kurukshetra, India, which incorporated 75% topsoil and 25% compost and achieved a 49% pollutant removal efficiency [

35]. A hybrid rain garden system in Korea, tested with synthetic runoff, demonstrated a 56% removal efficiency for heavy metals [

36]. The mean concentrations of most water quality parameters were significantly lower in the outflow than in the inflow, confirming the effectiveness of rain gardens in treating urban stormwater runoff. Additionally, runoff estimates were calculated using the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Curve Number (CN) method to assess potential relationships between runoff volume and outflow concentrations, but no significant correlation was identified. Most water quality parameters in the outflow met the surface runoff standards established by the USEPA and TCEQ, reinforcing the viability of rain gardens as a sustainable stormwater management practice.

Total and water-soluble concentrations of most metals were lower in outflow water than in inflow, demonstrating the rain gardens’ effectiveness in metal pollutant removal. Significant reductions in copper, zinc, and iron align with documented decreases in metal concentrations observed in bioretention systems designed for stormwater treatment [

37]. Similarly, sandy substrates combined with organic amendments have been associated with reductions in heavy metal concentrations exceeding 50% [

38]. Pollutant removal in rain gardens occurs through multiple mechanisms, including filtration, adsorption, precipitation, and biological treatment [

39], all of which likely contributed to the reductions observed in this study. Bioretention systems remain among the most widely implemented best management practices for urban stormwater control, effectively reducing runoff volume, peak flows, and pollutant loads, including heavy metals.

In contrast, lead and arsenic showed no significant removal, which is consistent with Trowsdale and Simcock [

40], who reported limited lead and arsenic reduction in bioretention systems due to their low mobility under typical pH conditions. The lack of significant removal may be attributed to the relatively low initial concentrations of these metals in the inflow, as well as their strong affinity for particulate matter rather than dissolved phases, which reduces their susceptibility to filtration and adsorption processes in the rain garden substrates [

41].

However, aluminum and magnesium concentrations were higher in the outflow than in the inflow, likely due to underlying geological conditions or differences in fill material composition across the three study sites. Ponded runoff in the rain gardens was exposed to Weches Formation rock, known to contain elevated aluminum and magnesium levels due to its glauconitic and clay-rich composition [

42]. The leaching of aluminum and magnesium from the Weches Formation could have contributed to the increased outflow concentrations, similar to observations of elevated dissolved metal concentrations in outflow water resulting from interactions with underlying geological substrates [

43].

Laboratory analysis of the rain garden soil revealed significant differences in manganese concentrations among the three sites. The mulch layer in Rain Gardens 2 and 3 contained substantially higher manganese concentrations (1,762.96 mg/L and 1,775.46 mg/L, respectively) than in Rain Garden 1 (710.42 mg/L), with statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001). In the sand layer, manganese concentrations also varied significantly, with Rain Garden 2 having the highest (243.20 mg/L), followed by Rain Garden 3 (106.25 mg/L) and Rain Garden 1 (54.39 mg/L). These variations may have contributed to the manganese levels detected in the outflow, as bioretention media composition strongly influences manganese and other metal leaching [

44].

Elevated calcium concentrations in the outflow were likely due to the dissolution of calcium from the underlying soil. The parent material in Rain Gardens 2 and 3 consists of sandstone containing silica and calcium carbonate as cementing agents, which undergoes weathering and releases calcium into percolating water. In regions where the parent material comprises sandstone cemented with CaCO₃, chemical weathering processes can release calcium into percolating water. The dissolution of calcite, a common form of CaCO₃, in sandstone has been studied to understand its impact on reservoir properties. Research indicates that calcite dissolution rates in reservoir sandstones can be significant, leading to increased calcium levels in the surrounding water [

45]. The elevated concentrations of calcium, sodium, and manganese can also alter pH and electrical conductivity, influencing the solubility and mobility of other metals. Higher pH values, such as those observed in the outflow in this study, can enhance metal precipitation and adsorption processes, ultimately improving the removal efficiency of certain heavy metals [

46].

The performance of the rain gardens improved from Year 1 to Year 2 of the study. During the first year, vegetation was still establishing, but by the second year, woody perennials had matured, increasing pollutant uptake and enhancing overall stormwater treatment efficiency. Metal and nutrient removal efficiency in rain gardens has been shown to significantly improve as plant root systems develop and microbial communities become more active, reinforcing the role of vegetation maturity in optimizing bioretention performance over time[

47].

Variability in removal rates among the rain gardens was influenced by differences in initial inflow water conditions and site-specific factors, particularly for aluminum, iron, manganese, sodium, boron, nitrate, and nitrite. This variation aligns with research indicating that rain garden performance is site-dependent and affected by hydrologic conditions, substrate composition, and pollutant loading rates [

48]. Future studies should consider long-term monitoring and controlled experiments to further isolate the effects of substrate composition, vegetation type, and hydrologic variability on pollutant removal efficiency.

Figure 1.

Aerial map showing the locations of rain gardens 1, 2, and 3 on the Stephen F. Austin State University campus in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. The map indicates the contributing drainage areas for each rain garden, including surrounding impervious surfaces such as parking lots, sidewalks, and buildings. These contributing areas were the primary sources of stormwater runoff sampled during the study.

Figure 1.

Aerial map showing the locations of rain gardens 1, 2, and 3 on the Stephen F. Austin State University campus in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. The map indicates the contributing drainage areas for each rain garden, including surrounding impervious surfaces such as parking lots, sidewalks, and buildings. These contributing areas were the primary sources of stormwater runoff sampled during the study.

Figure 2.

Installation of drainage pipes and pea gravel layer during the construction phase of Rain Garden 2 in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. After excavation, perforated drainage pipes were placed at the base of the rain garden to facilitate excess water outflow. The pea gravel layer, approximately 0.2 meters thick, was then evenly distributed over the pipes to enhance drainage efficiency and prevent clogging. This foundational layer supports proper water infiltration and contributes to the overall functionality of the rain garden system.

Figure 2.

Installation of drainage pipes and pea gravel layer during the construction phase of Rain Garden 2 in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. After excavation, perforated drainage pipes were placed at the base of the rain garden to facilitate excess water outflow. The pea gravel layer, approximately 0.2 meters thick, was then evenly distributed over the pipes to enhance drainage efficiency and prevent clogging. This foundational layer supports proper water infiltration and contributes to the overall functionality of the rain garden system.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the efficiency (%) of pollutant removals for water soluble (WS) and total concentrations (TC) for rain gardens during first (plant establishment, Sep. 2012-Aug. 2013) and second (Sep. 2013-Sep. 2014) years of study at three rain gardens in Nacogdoches, Texas, USA. Blank bars are left because some of the parameters were removed in specific rain garden.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the efficiency (%) of pollutant removals for water soluble (WS) and total concentrations (TC) for rain gardens during first (plant establishment, Sep. 2012-Aug. 2013) and second (Sep. 2013-Sep. 2014) years of study at three rain gardens in Nacogdoches, Texas, USA. Blank bars are left because some of the parameters were removed in specific rain garden.

Table 1.

Contributing area, impervious area, percentage of impervious area, calculated bed area, and constructed bed area (in square meters) for the three rain gardens.

Table 1.

Contributing area, impervious area, percentage of impervious area, calculated bed area, and constructed bed area (in square meters) for the three rain gardens.

| Calculated area |

Rain garden 1 (m2) |

Rain garden 2 (m2) |

Rain garden 3 (m2) |

| Contributing area (A) |

3807 |

2663 |

2635 |

| Cumulative area of all impervious surfaces on the site impervious area (IA) |

1290 |

724 |

1015 |

| Calculated bed area (AF) |

97 |

66 |

69 |

| Constructed Bed area |

154 |

89 |

92 |

| Percent impervious area (I) |

33.90% |

27.20% |

38.5 |

Table 3.

Monthly precipitation (mm) during the study period and long-term average precipitation (1901-2009) from the Stephen F. Austin State University/National Weather Service weather station.

Table 3.

Monthly precipitation (mm) during the study period and long-term average precipitation (1901-2009) from the Stephen F. Austin State University/National Weather Service weather station.

| Month |

2013-2014 |

1901-2009 |

Difference |

| September |

147.1 |

85.1 |

62.0 |

| October |

179.6 |

89.2 |

90.4 |

| November |

68.1 |

34.0 |

34.1 |

| December |

58.7 |

121.0 |

-62.3 |

| January |

44.5 |

103.9 |

-59.5 |

| February |

58.4 |

101.7 |

-43.3 |

| March |

90.9 |

99.5 |

-8.6 |

| April |

36.8 |

112.6 |

-75.8 |

| May |

178.1 |

127.3 |

50.8 |

| June |

56.9 |

98.3 |

-41.4 |

| July |

106.2 |

87.4 |

18.8 |

| August |

39.6 |

70.0 |

-30.4 |

| September |

103.9 |

85.1 |

18.8 |

| Total |

1168.7 |

1125.1 |

43.6 |

Table 4.

Mean water-soluble concentrations (mg/L) for metals in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

Table 4.

Mean water-soluble concentrations (mg/L) for metals in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

| |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

| Parameter |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

| Copper |

0.047 |

0.010 |

0.051 |

0.011 |

0.050 |

0.008 |

| Zinc |

0.013 |

0.007 |

0.015 |

0.006 |

0.022 |

0.007 |

| Arsenic |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.000 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Lead |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.000 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

| Iron |

0.286 |

0.679 |

0.248 |

0.086 |

0.245 |

0.181 |

| Aluminum |

0.641 |

19.311 |

4.360 |

2.029 |

2.138 |

14.124 |

| Magnesium |

2.883 |

5.521 |

4.280 |

23.575 |

2.679 |

10.540 |

| Manganese |

0.005 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.003 |

0.024 |

0.026 |

| Boron |

0.023 |

0.026 |

0.035 |

0.062 |

0.022 |

0.044 |

| Sodium |

5.013 |

8.191 |

3.986 |

14.848 |

2.820 |

18.081 |

Table 5.

Total concentrations (mg/L) for metals in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values indicate concentrations that are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

Table 5.

Total concentrations (mg/L) for metals in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values indicate concentrations that are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

| |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

| Parameter |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

| Copper |

0.095 |

0.008 |

0.071 |

0.059 |

0.069 |

0.007 |

| Zinc |

0.032 |

0.010 |

0.034 |

0.008 |

0.036 |

0.006 |

| Arsenic |

0.002 |

0.003 |

0.005 |

0.001 |

0.002 |

0.001 |

| Lead |

0.006 |

0.004 |

0.005 |

0.002 |

0.008 |

0.004 |

| Iron |

1.060 |

2.150 |

2.995 |

0.843 |

1.478 |

1.023 |

| Aluminum |

1.127 |

23.641 |

3.944 |

2.380 |

12.368 |

6.365 |

| Magnesium |

2.279 |

4.433 |

3.135 |

19.161 |

2.394 |

7.686 |

| Manganese |

0.129 |

0.214 |

0.372 |

0.982 |

0.241 |

0.439 |

| Boron |

0.572 |

0.883 |

2.453 |

0.265 |

0.791 |

0.018 |

| Sodium |

3.136 |

6.223 |

4.589 |

8.507 |

1.736 |

8.986 |

Table 6.

Mean concentrations (mg/L) for nutrients and other parameters in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values indicate concentrations that are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

Table 6.

Mean concentrations (mg/L) for nutrients and other parameters in samples collected from September 2013 through September 2014 for three rain gardens at the Piney Woods Native Plant Center in Nacogdoches, TX, USA. Bold underlined values indicate concentrations that are significantly greater within each rain garden pair (inflow vs outflow) at α = 0.05.

| |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

| Parameter |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

Inflow |

Outflow |

| Total Phosphorus |

0.021 |

0.215 |

0.327 |

0.437 |

0.357 |

0.639 |

| Dissolved Phosphorus |

0.130 |

0.040 |

0.145 |

0.032 |

0.234 |

0.002 |

| Nitrate |

0.745 |

0.802 |

0.167 |

3.924 |

0.305 |

2.616 |

| Nitrite |

1.778 |

1.317 |

5.073 |

10.376 |

7.091 |

4.461 |

| Total Potassium |

1.243 |

1.882 |

5.327 |

1.761 |

6.246 |

1.419 |

| Dissolved Potassium |

2.484 |

3.647 |

5.327 |

3.980 |

6.735 |

3.113 |

| Total Calcium |

24.082 |

41.950 |

12.120 |

76.572 |

8.961 |

57.325 |

| Dissolved Calcium |

26.456 |

49.006 |

15.560 |

81.820 |

9.213 |

67.789 |

| Total Sulfur |

1.842 |

3.343 |

2.124 |

8.717 |

1.487 |

5.136 |

| Dissolved Sulfur |

2.308 |

3.180 |

2.199 |

8.954 |

1.748 |

6.001 |

| pH |

7.342 |

7.545 |

7.030 |

7.497 |

6.789 |

7.352 |

| Electrical conductivity |

185.700 |

329.200 |

215.000 |

702.600 |

162.100 |

550.100 |

| Bicarbonate |

93.161 |

187.400 |

78.299 |

358.400 |

47.502 |

242.700 |

| Fluoride |

0.261 |

0.260 |

0.289 |

0.174 |

0.311 |

0.311 |

| Chloride |

1.233 |

2.118 |

1.279 |

6.386 |

2.901 |

12.899 |

Table 7.

Comparative study of significantly different total concentration of water quality parameters in rain garden during the first and second year of construction, based on outflow mean concentrations. Mean values highlighted in red indicate that the outflow concentration was higher than the inflow concentration. Mean values highlighted in yellow represent p-values where the inflow concentration was higher than the outflow concentration. Fields without values indicate no significant difference.

Table 7.

Comparative study of significantly different total concentration of water quality parameters in rain garden during the first and second year of construction, based on outflow mean concentrations. Mean values highlighted in red indicate that the outflow concentration was higher than the inflow concentration. Mean values highlighted in yellow represent p-values where the inflow concentration was higher than the outflow concentration. Fields without values indicate no significant difference.

| |

Sep. 2012- Aug. 2013 |

Sep. 2013- Sep. 2014 |

| |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

| Aluminum |

0.022 |

0.003 |

|

0.007 |

0.014 |

|

| Boron |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calcium |

|

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Copper |

|

0.003 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Iron |

0.020 |

<0.001 |

|

0.019 |

0.004 |

|

| Potassium |

|

0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

0.002 |

<0.001 |

| Magnesium |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Manganese |

|

<0.001 |

0.003 |

|

0.001 |

|

| Sodium |

0.008 |

0.007 |

<0.001 |

0.011 |

|

|

| Phosphorus |

|

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

0.006 |

<0.001 |

| Lead |

|

<0.001 |

0.151 |

|

|

|

| Sulfur |

|

0.002 |

<0.001 |

|

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Zinc |

|

0.012 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

Table 8.

Comparative study of significantly different water-soluble concentration of water quality parameters in raingarden during the first and second year of construction, based on mean concentrations. Mean values highlighted in red indicate that the outflow concentration was higher than the inflow concentration. Mean values highlighted in yellow represent p-values where the inflow concentration was higher than the outflow concentration. Fields without values indicate no significant difference.

Table 8.

Comparative study of significantly different water-soluble concentration of water quality parameters in raingarden during the first and second year of construction, based on mean concentrations. Mean values highlighted in red indicate that the outflow concentration was higher than the inflow concentration. Mean values highlighted in yellow represent p-values where the inflow concentration was higher than the outflow concentration. Fields without values indicate no significant difference.

| |

Sep. 2012- Aug. 2013 |

Sep. 2013- Sep. 2014 |

| |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 3 |

| Aluminum |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.037 |

<0.001 |

0.024 |

0.004 |

| Arsenic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Boron |

|

|

|

|

0.010 |

|

| Calcium |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Copper |

|

0.003 |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Iron |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.009 |

0.001 |

|

| Potassium |

|

0.003 |

0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Magnesium |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Manganese |

|

<0.001 |

|

|

0.039 |

0.004 |

| Sodium |

0.020 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Phosphorus |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Lead |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sulfur |

|

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.042 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Zinc |

|

<0.001 |

0.007 |

0.012 |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

Table 10.

Mean concentrations (ppm) from rain garden fill materials by layer. Means preceded by different letters are significantly different at α = 0.05.

Table 10.

Mean concentrations (ppm) from rain garden fill materials by layer. Means preceded by different letters are significantly different at α = 0.05.

| |

Mulch Layer (0- 3 cm depth) |

Sand Layer (3- 24 cm depth) |

| Parameter |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

Rain Garden 1 |

Rain Garden 2 |

| Calcium |

14302.94 a |

11625.48 c |

13349.22 b |

|

|

|

| Magnesium |

710.42 b |

1762.96 a |

1775.46 a |

54.39 c |

243.20 a |

106.25 b |

| Phosphorus |

451.04 c |

527.37 b |

763.39 a |

29.14 c |

75.48 a |

45.43 b |

| Copper |

8.08 a |

6.40 c |

7.66 b |

0.32 a |

0.01 c |

0.17 b |

| Zinc |

44.23 b |

42.91 b |

68.11 a |

2.54 c |

9.62 a |

5.06 b |

| Aluminum |

8793.44 b |

10765.62 a |

9063.87 b |

5762.07 c |

9617.47 a |

6555.66 b |

| Iron |

7367.88 c |

8547.09 b |

9393.83 a |

1365.53 c |

8064.03 a |

3572.73 b |

| Manganese |

177.83 c |

323.04 b |

430.67 a |

9.62 c |

51.64 a |

22.74 b |

| Boron |

12.92 c |

21.46 b |

25.77 a |

0.14 b |

5.60 a |

0.70 b |

| Nitrogen |

43.36 a |

17.96 b |

15.28 c |

1.88 b |

3.75 a |

1.97 a |

| Sodium |

43.23 b |

16.59 c |

50.22 a |

|

|

|