1. Introduction

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) was once a cornerstone of the multimodal treatment for metastatic germ cell tumors (GCTs) of the testis, following its technical refinement in the 1960s and 1970s. Its significance diminished with the introduction of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. However, due to growing concerns over the severe long-term side effects of chemotherapy, RPLND is recently regaining importance. The most frequent indication for RPLND now occurs in the post-chemotherapy setting. Additionally, RPLND is increasingly used for primary cases with low-volume lymphadenopathy where tumor markers are not elevated. Open RPLND (O-RPLND) has thus far been the standard procedure, representing a complex and potentially morbid treatment modality, particularly in the post-chemotherapy setting. The recognized risks associated with RPLND include intraoperative hemorrhage from large vessel laceration, damage to neighboring organs, postoperative ileus, chylous ascites, and retrograde ejaculation. The reported complication rate in the primary setting is approximately 10–20%.

Over the past two decades, minimally invasive approaches have been reported to decrease procedure-related morbidity. The first robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (R-RPLND) was performed in 2006 at Geisinger Medical Center in Pennsylvania . In several studies, R-RPLND demonstrated promising potential as a safe treatment for germ cell tumors (GCT), with comparable oncologic efficacy to open RPLND, especially when conducted by experienced surgeons in specialized centers. The key advantages of R-RPLND over open RPLND include shorter operating time, reduced postoperative pain, and decreased hospital stays (HS), which facilitate quicker recovery. In the post-chemotherapy setting, R-RPLND also appears feasible, with an acceptable complication rate and low conversion rates to open surgery.

With the increasing worldwide availability of robotic surgery facilities, increased attention has been directed toward the learning curve associated with this novel technological approach. The aim of this study was to evaluate the first series of R-RPLNDs performed in our institution, analyze associations between clinico-oncological features and surgical results, and, particularly, examine the learning curve of a single surgeon. We hypothesized that the complications rate would be associated with oncological characteristics and that increasing experience would translate into decreases in operation time (OT), estimated blood loss (EBL), and the frequency of operative complications.

2. Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the first consecutive 30 R-RPLNDs performed for GCTs at our center during 2020 to 2024. The cases were identified by the institutional electronic patient record system. All R-RPLND was performed using the DaVinci X/Xi System through a transperitoneal approach with the patient in Trendelenburg position, and the robot is docked over the patient’s head. All operations were performed by one single surgeon (CW).

Patient demographics (age, BMI), tumor characteristics including pathology of primary tumor were recorded along with pre-operative staging analysis of largest transverse diameter of retroperitoneal nodes, clinical stage, IGCCCG risk-group classification, and previous chemotherapy regimens were recorded. Additionally, the surgical field (unilateral/bilateral), OT, EBL, HS, and final pathology of resected specimen and lymph node count were documented. OT was defined as the time interval from first incision to last stitch. Complications within 90 days following surgery were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo Classification. Grade I–II complications were defined as minor and grade IIIa–V as major. The median time of follow-up was noted, as well as the occurrence of relapse or other untoward events. For statistical analysis, the patients were categorized into three groups: group A (consecutive cases 1-10), group B (cases 11-20), and group C (cases 21-30). We determined the median values and interquartile ranges (IQR) of OT, HS, EBL, lymph node count, as well as complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system for the entire patient population and for each of the three patient categories. The results of the three patient categories were compared to each other using the Kruskal-Wallis-Test. Logistic regression analyses were used to analyze independent variables such as case number (CN), clinical stage (CS), chemotherapy status, preoperative retroperitoneal mass size, final histology, and body mass index (BMI). The comparisons between the groups involved both univariate and multivariate analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. R-Studio (Posit Software, PBC formerly RStudio, PBC, 2024) was used for analysis, and DATAtab (DATAtab Team 2024, Online Statistics Calculator. DATAtab e.U. Graz, Austria) was used for graphical analysis.

All study activities were conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association as amended by the 64th General Assembly (2013). Ethical approval was provided by the Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg (PV7288).

3. Results

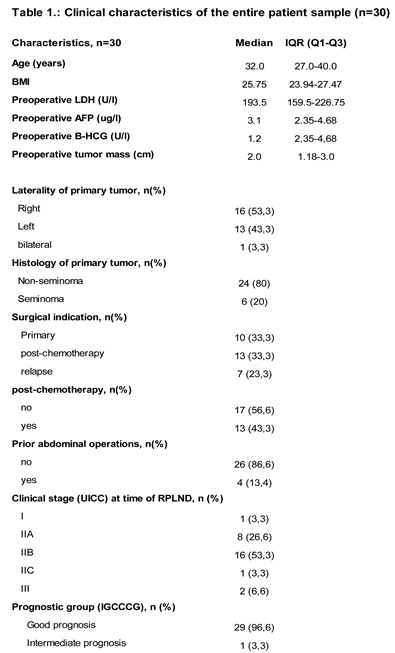

The first 30 patients with GCT undergoing R-RPLND in our institution were retrospectively included in this study. Their clinical details are summarized in

Table 1.

In the entire patient population (n=30), the median OT (first incision to last stitch) was 186.5 min, EBL was 100 ml, length of s was 6.5 days The median size of retroperitoneal lymph nodes on preoperative CT (largest axial lymph node diameter) was 2 cm, lymph node yield was n=13, the median number of GCT-harboring positive lymph nodes was 2. There were two (6,6%) major perioperative complications, both in pcRPLNDs. One (3.3%) was a conversion to an open procedure secondary to hemorrhage from aortic laceration rescued by aortic grafting (Grade IIIb). The other was a hemorrhage from vena cava laceration, which was oversewn without conversion (Grade IIIa). Postoperatively, 7 (23,3%) Grade II complications were noticed, one postoperative anemia requiring blood transfusion, three patients with prolonged lymphorrea (all primary R-RPLND), two patients with chylus ascites (one primary and one pcRPLND), and one transient paresis of the legs. No patient needed extra percutaneous drainage. There were no Clavien–Dindo grade 4 or 5 complications among all R-RPLND cases.

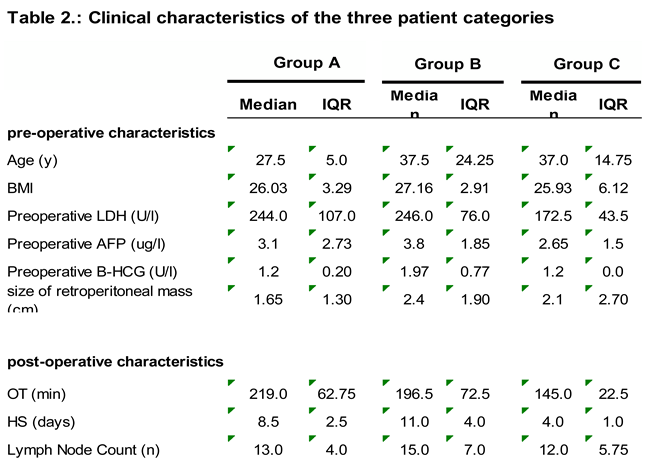

The comparison of results among the three patient groups are listed in

Table 2.

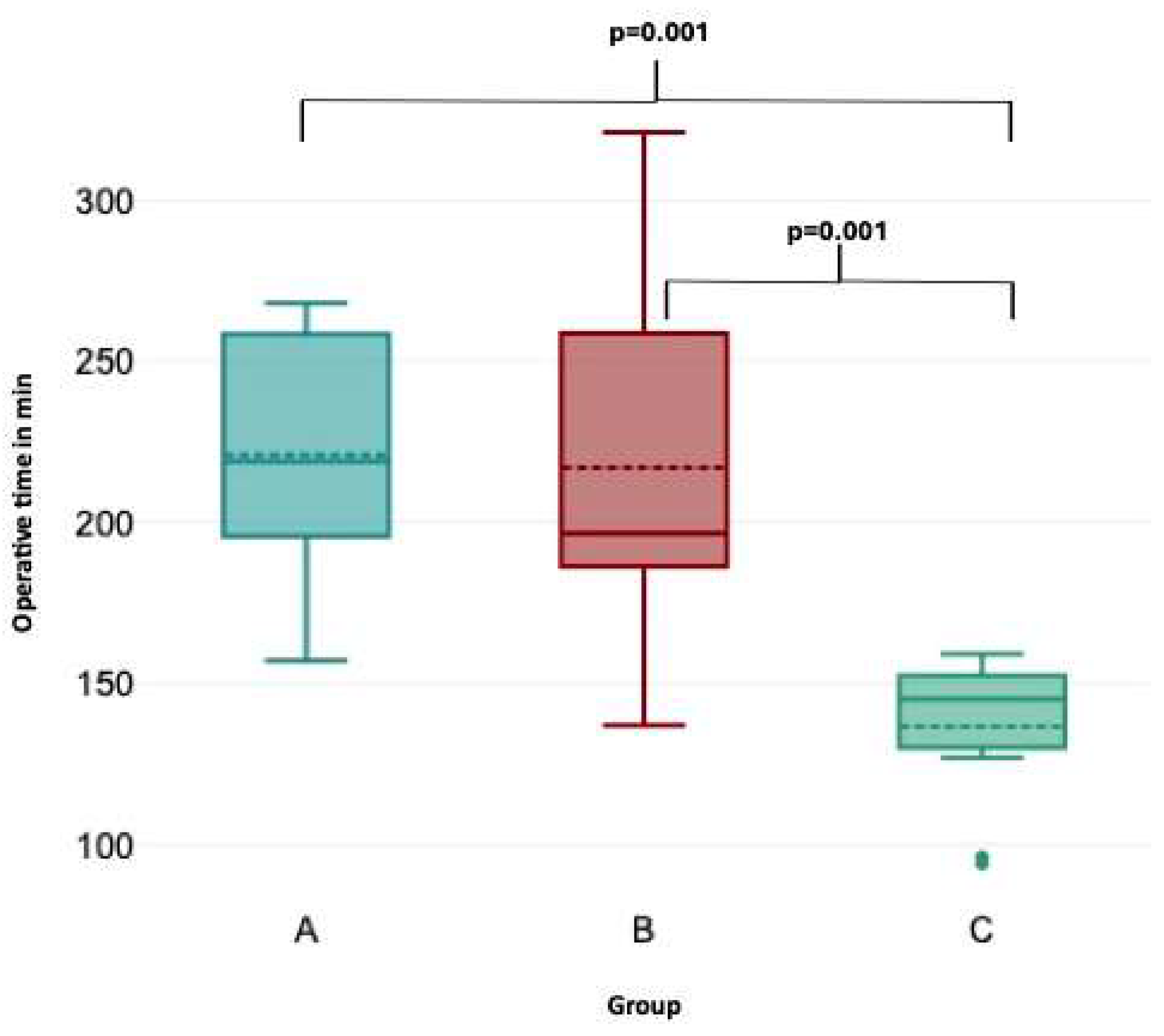

OT (

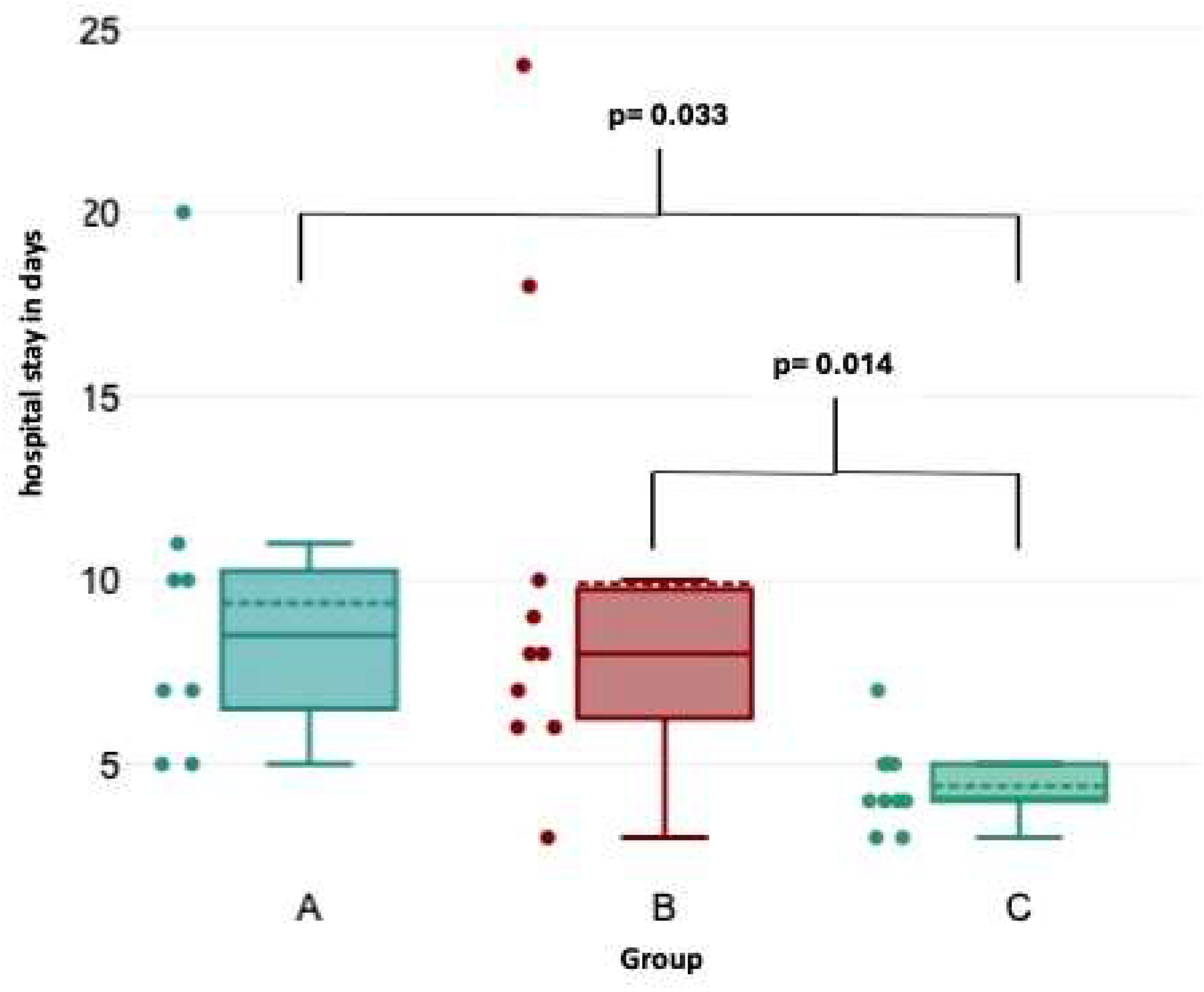

Figure 1) was significantly shorter in group C than in groups A and B (Kruskal-Wallice-Test p <0,001). Likewise, HS (

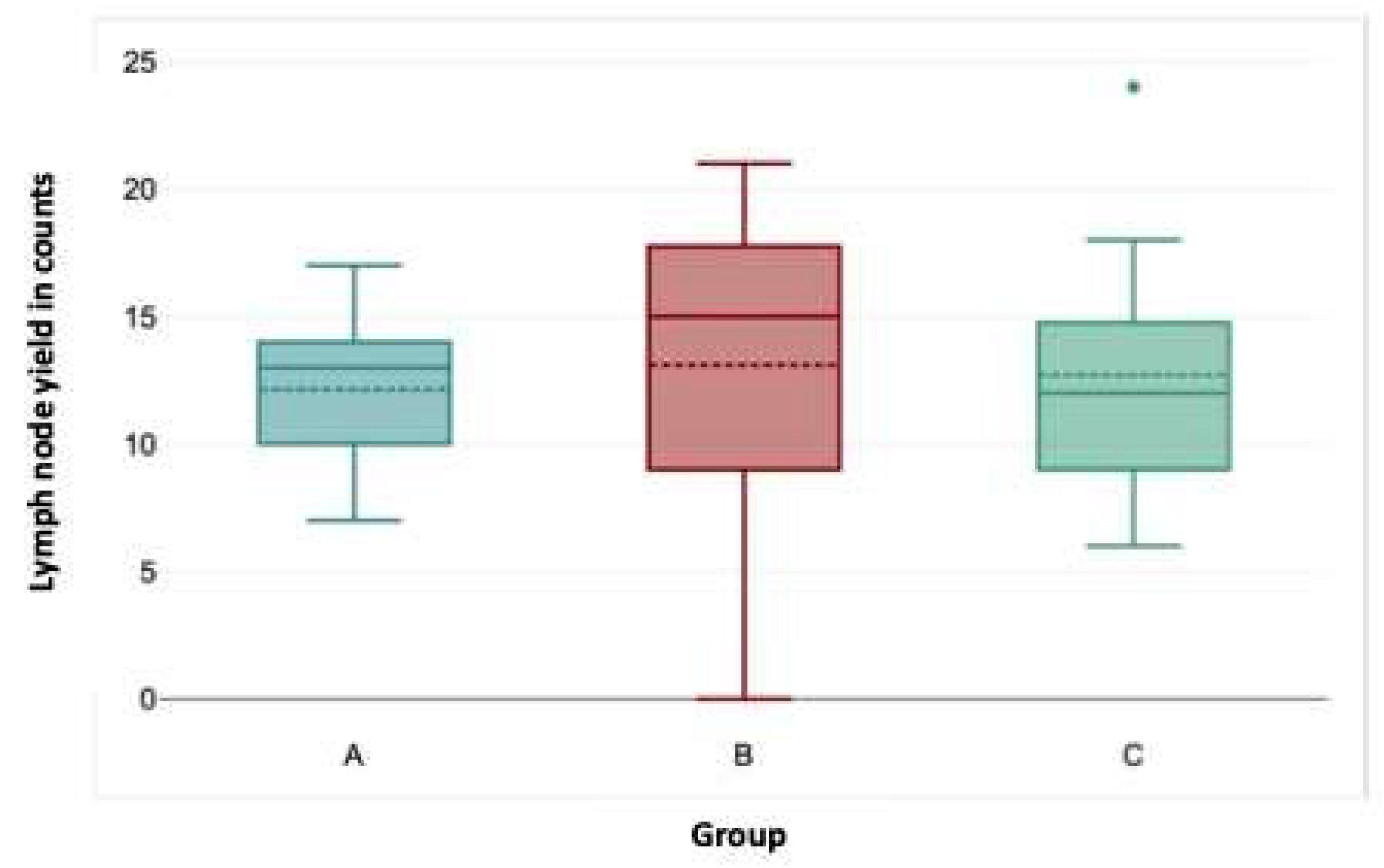

Figure 2) was significantly shorter in group C compared to the other groups (p=0.033 for group A-C; p=0.014 for group B-C). Lymph node yield was not significantly different in numbers between groups A-C (

Figure 3).

By contrast, no significant differences among the groups was seen for EBL (p = 0.461), lymph node yield (p = 0.942), positive lymph nodes (p= 0.5275), preoperative mass size (p=0.963), and preoperative LDH, AFP and ß-HCG (p=0.405, p=0.370 and p=0.735, respectively). Furthermore, groups A to C were not statistically different regarding the relative proportion of post-chemotherapy procedures, clinical stages, and prior abdominal operations (p= 0.877, p=0.231, p=0.757, respectively).

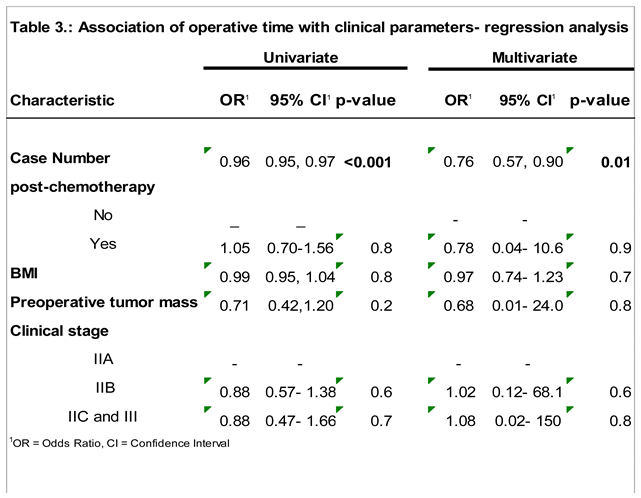

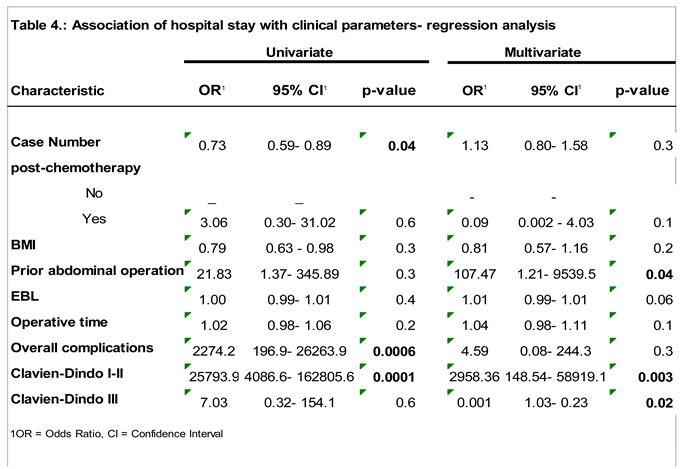

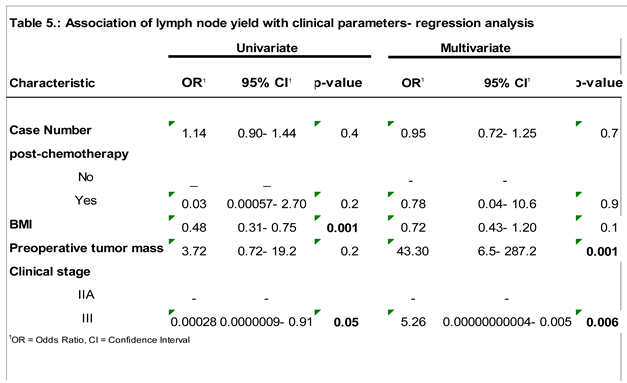

The significantly shorter OT with increasing consecutive case numbers was confirmed in multivariate analysis (

Table 3, p=0.01). HS was significantly affected by overall complications (p=0.0006), but only by low-grade complications (p=0.0001), not by high-grade complications (p=0.6). In multivariate regression analysis, HS was significantly longer with low-grade complications (p=0.003) and high-grade complications (p=0.02). In addition, uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis regarding complications did not disclose any predicting factor for overall complications, low-grade or high-grade complications, respectively. Remarkably, higher lymph node counts and positive lymph node did not impact the frequency of chylus ascites (Clavien Dindo II). The results of uni- and multivariate analysis are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Pathological and Oncological Outcome

In the entire patient population, final pathology of R-RPLND specimens revealed viable tumor in 24 (80%) patients, thereof teratoma in 9 (30%), embryonal carcinoma in 9 (30%), one primitive neuroendocrine tumor (PNET) (3,3%), seminoma in 4 (13,3%), and one (3,3%) with mixed histology of seminoma and embryonal carcinoma patients, respectively. 5 Patients with pc-RPLND (20%) had fibrosis/necrosis, histologically. One patient with suspected lymph node metastasis of seminoma (3,3%) had no malignancy detected (pN0). The median follow-up was 16 months. Eleven (35%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Two (6,4%) patients recurred following R-RPLND. One patient developed an extensively bulky retroperitoneal disease 1 month after R-RPLND, and he was subsequently submitted to high-dose chemotherapy. One relapsed with teratoma in the retrocrural space and at the cranial border of the previous R-RPLND template 13 months postoperatively. He was rescued with open redo-RPLND.

Logistic regression analysis for relapse showed that no factor (Case number, post-chemotherapy, CS, preoperative mass size, lymph node count, positive lymph nodes, or complications) has an impact on relapse rates in the entire population (n=30). Also, group ranking (categories A to C) had no significant impact on relapse rate (Kruskal-Wallice test p= 0.126).

4. Discussion

Our study evaluates the learning curve for R-RPLND in the primary and post-chemotherapy testicular cancer setting with regard to various peri- and post-operative parameters. To the best of our knowledge, this study constitutes the first assessment of distinct groups of case numbers (in chronological sequence) within the learning curve.

The crucial result of the present study is that robotic RPLND is a feasible procedure with a low complication rate and acceptable oncological outcome, but it requires a learning curve for each surgeon embarking on this procedure. Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated that robotic RPLND outperforms traditional approaches by significantly reducing perioperative complications [

4,

5].

Our findings clearly indicate a significant reduction in OT and HS with increasing surgeon experience. One other study found that OT is predicted to decrease by one hour after performing 44 cases, highlighting the importance of experience in improving efficiency [

6]. But, OT is also much influenced by the individual surgeon’s experience and talent, with some surgeons achieving faster reductions in time than others [

6].

An important aspect of the learning curve is that increasing case numbers were associated with fewer overall complications. The rate of major complications (Clavien Dindo III, IV) is 6.6% in our series. Previous reports suggested significantly lower overall complication rates in the R-RPLND group than in the O-RPLND group, but similar major (Grade ≥III) complication rates, in approximately 5-11% of cases, respectively [

4,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Our complication rate also compares well with the complication rate of 14.4% reported in a German series of 146 pcRPLNDs and with an 8.8% complication rate in 35 primary O-RPLND [

11]. Nason et al.. reported a low complication rate (3.7% minor, 11.1% major) for R-RPLND [

1]. In 2020, a literature survey revealed Clavien Dindo II/ IV complication rates in pc-RPLND in up to 23%, with the lowest rates in institutions with high case loads [

11]. Our study, which included both pcRPLND and primary resections, demonstrated complication rates that can be compared to the O-RPLND series. Reported overall complication rates for O-RPLND ranged from 16.6% to 37.9%, while major complications occurred in 8.3% of cases [

3,

5,

12]. In our study, the most common complication was lymph leakage (minor complication). Consequently, patient safety is not compromised during a surgeon’s early case sequence numbers for this procedure [

6].

The total lymph node count is an important performance measure in oncologic surgery [

6]. The number of lymph nodes retrieved during R-RPLND was comparable to or higher than that retrieved during L-RPLND, indicating effective oncological control [

4,

7]. Total lymph node count has also been shown to be an independent predictor of recurrence in the post-chemotherapy RPLND setting. Our series has shown that the total lymph node count was higher with increased BMI and CS III, and it was also significantly higher in larger preoperative mass size and CS III, as found in multivariate analysis. The positive lymph node count was only influenced by the post-chemotherapy setting in the univariate analysis. However, the lymph node count did not change within the case numbers. This suggests that lymph node count is not affected by the earlier stages of the learning curve [

6,

13].

As shown in the present study, the occurrence of relapses was not associated with any particular risk factor, and it is also not affected by the learning curve, proving a safe short-term oncological outcome. Notably, several other studies revealed no difference in recurrence rates between robotic-assisted and standard open RPNLD [

3,

14,

15,

16].

The introduction of robotic surgery has revolutionized the field of urological oncology, with several studies demonstrating a lot of benefits of robot-assisted approaches in general urology compared to open surgery [

17,

18,

19]. The surgical platform for robot-assisted surgery has enabled many surgeons to join a popular trend in minimally invasive surgery, which offers prospective benefits to patients, such as shorter HS, earlier recovery, less pain, and operational benefits to surgeons [

20].

After the first R-RPLND in 2006, several comparisons have proved its non-inferiority to standard O-RPLND regarding oncological outcomes [

1,

2,

21,

22,

23]. Meanwhile, R-RPLND demonstrated its superiority over O-RPLND in perioperative outcomes, especially with respect to OT, EBL, and HS. Several recent reports have considered RPLND a de-escalating approach aiming to maintain the traditional excellent oncologic result while minimizing treatment burden and toxicity [

3,

21,

24]. In fact, R-RPLND involves the potential of a paradigm shift in the management of testicular cancer, particularly in patients with clinical stage I-II nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT) requiring surgical intervention [

8,

25]. Nevertheless, the goals of any innovative surgical technique are reproducibility and safety. Understanding the learning curve of R-RPLND could benefit experienced robotic surgeons in preparation for the critical surgical steps, which will ensure patient safety and oncologic efficacy [

6]. The current literature indicates that R-RPLND is both safe and feasible in the primary and post-chemotherapy settings, as well as short-term oncological outcome [

1,

3,

26,

27].

The limitations of our study relate to its retrospective design and to the still small number of cases for assessing the learning curve. Some selection bias may be associated with the fact that patients chosen for R-RPLND mostly had limited disease characteristics. Patients with extended disease or large volume retroperitoneal masses were subjected to open RPLND during the study period. To further identify how these learning curves affect training requirements for residents and fellows, a study examining junior staff is necessary to answer these questions further [

6]. Generally, the learning curve in robotic surgery is multifaceted and influenced by factors such as the surgical procedure type, prior surgical experience, number of cases performed, and the metrics used to assess proficiency [

28]. Surgeons generally experience rapid improvement in the initial cases, followed by a plateau as they gain more experience [

29]. Understanding this learning curve is crucial for optimizing outcomes, enhancing surgical proficiency, and ensuring patient safety.

While current data are encouraging, further research, especially prospective randomized trials, is needed to confirm these findings and assess the true efficacy and oncological safety of R-RPLND, as well as further investigation into optimal patient selection for R-RPLND. Specifically, long-term outcomes are currently still little understood. Continuous data collection and analysis are essential for refining patient selection criteria and optimizing surgical techniques for R-RPLND [

8,

9].

In Addition, advancements in technology and training methodologies hold promise for shortening the learning curve of R-RPLND. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) platforms can enhance preoperative planning and intraoperative navigation, whereas artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms can provide real-time guidance and error prevention. Additionally, the development of standardized curricula and centralized databases for R-RPLND outcomes will enable more precise benchmarking and knowledge-sharing.

Nevertheless, R-RPLND appears to be a safe and feasible alternative to open surgery for appropriately selected patients with GCT [

7,

30].

5. Conclusions

R-RPLND for GCT shows a clear learning curve, with significant advancement in OT, HS, and complication rates as surgeons gain experience. While early oncological outcomes are promising, further research is needed to confirm these findings and establish R-RPLND as a standard treatment option. The establishment of standardized curricula and centralized databases for R-RPLND is essential for precise benchmarking and effective knowledge sharing. This will lead to improved patient outcomes, enhanced research opportunities, and consistent care across medical centers. Overall, R-RPLND shows promising potential as a safe and effective treatment for GCT, particularly when performed by experienced surgeons in specialized centers.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee Ärztekammer Hamburg, approval number [PV7288].

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from participants to participate in the study. .

Author Contributions

Markus Angerer and Klaus Peter Dieckmann contributed to the study’s conception and design. Christian Wülfing supervised the whole project. Markus Angerer and Klaus Peter Dieckmann performed the data collection and material preparation; Markus Angerer contributed to the statistical analysis. Klaus Peter Dieckmann and Markus Angerer wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Markus Angerer, Klaus Peter Dieckmann, and Christian Wülfing participated in manuscript editing and discussion. All authors have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

References

- Nason, G.J.; Kuhathaas, K.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Jewett, M.A.S.; O’malley, M.; Sweet, J.; Hansen, A.; Bedard, P.; Chung, P.; Hahn, E.; et al. Robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for primary and post-chemotherapy testis cancer. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 16, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davol, P.; Sumfest, J.; Rukstalis, D. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. Urology 2006, 67, 199.e7–199.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, P.; Hong, A.; Furrer, M.A.; Lee, E.W.Y.; Dev, H.S.; Coret, M.H.; Adshead, J.M.; Baldwin, P.; Knight, R.; Shamash, J.; et al. A comparative study of peri-operative outcomes for 100 consecutive post-chemotherapy and primary robot-assisted and open retroperitoneal lymph node dissections. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ning, Y.; Luo, H.; Qiu, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X. Clinical efficacy and safety of robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1257528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanvadia, R.; Ashbrook, C.; Bagrodia, A.; Lotan, Y.; Margulis, V.; Woldu, S. Population-based analysis of cost and peri-operative outcomes between open and robotic primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for germ cell tumors. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermerhorn, S.M.; Christman, M.S.; Rocco, N.R.; Abdul-Muhsin, H.M.; L'Esperance, J.O.; Castle, E.P.; Stroup, S.P. Learning Curve for Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection. J. Endourol. 2021, 35, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Zeng, Z.; Li, Y.; Gan, L.; Meng, C.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, L. The role of robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 2808–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiester, A.; Nini, A.; Arsov, C.; Buddensieck, C.; Albers, P. Robotic Assisted Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection for Small Volume Metastatic Testicular Cancer. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Muhsin, H.; Rocco, N.; Navaratnam, A.; Woods, M.; L’esperance, J.; Castle, E.; Stroup, S. Outcomes of post-chemotherapy robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular cancer: multi-institutional study. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 3833–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.J.; Guglielmetti, G.B.; Orvieto, M.; Bhat, K.R.S.; Patel, V.R.; Coelho, R.F. Robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy: The state of art. Asian J. Urol. 2021, 8, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, C.G.; Krampe, S.; Matthies, C.; Anheuser, P.; Nestler, T.; Simon, J.; Isbarn, H.; Dieckmann, K.P. Major complications of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in a contemporary cohort of patients with testicular cancer and a review of the literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Santomauro, M.; Biewenga, E.; Nork, J.; Scarborough, P.; Derweesh, I.; Stroup, S.; Castle, E.; Porter, J.; L'Esperance, J. PD15-08 OPEN VERSUS ROBOTIC-ASSISTED LAPAROSCOPIC RETROPERITONEAL LYMPH NODE DISSECTION FOR TESTICULAR CANCER. J. Urol. 2015, 193, e327–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, J.; Barahona, M.; Pla, M.J.; Rovira, J.; Garcia-Tejedor, A.; Gil-Ibanez, B.; Gaspar, H.M.; Sabria, E.; Bartolomé, C.; Marti, L. Robotic Transperitoneal Infrarenal Para-Aortic Lymphadenectomy With Double Docking: Technique, Learning Curve, and Perioperative Outcomes. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.; Abdul-Muhsin, H.; Stroup, S.; Derweesh, I.; Woods, M.; Porter, J.; Castle, E.; L'Esperance, J. MP23-09 ROBOT-ASSISTED LAPAROSCOPIC RETROPERITONEAL LYMPH NODE DISSECTION FOR NON-SEMINOMATOUS TESTICULAR CANCER IN THE PRIMARY SETTING: A RETROSPECTIVE MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS. J. Urol. 2016, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Gu, L.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Y.; et al. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Retroperitoneal Lymph node Dissection for Clinical Stage I Non-seminomatous Germ Cell Tumor of Testis: A Comparative Analysis. Urol J. 2021, 18, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Duplisea, J.J.; Petros, F.G.; González, G.M.N.; Williams, S.B.; Tu, S.-M.; Karam, J.A.; Huynh, T.T.; Ward, J.F. Robotic Postchemotherapy Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection for Testicular Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, T.S.; Allman, B.L.; Johnson, M.; Power, A.; Sheinfeld, J.; Power, N.E. Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection: Anatomical and Technical Considerations from a Cadaveric Study. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, B.H.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Laudone, V.P. A Randomized Trial of Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Cystectomy. New Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Sun, Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of perioperative outcomes comparing robot-assisted versus open radical cystectomy. BMC Urol. 2016, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchulo A, Ali A. Is Robotic-Assisted Surgery Better? AMA J Ethics. 2023 Aug 1;25(8):E598-604.

- Lin, J.; Hu, Z.; Huang, S.; Shen, B.; Wang, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, P.; Jin, X. Comparison of laparoscopic, robotic, and open retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for non-seminomatous germ cell tumor: a single-center retrospective cohort study. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 1877–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, H.; Mansour, A.M.; Psutka, S.P.; Kim, S.P.; Porter, J.; Gaspard, C.S.; Dursun, F.; Pruthi, D.K.; Wang, H.; Kaushik, D. Robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: a systematic review of perioperative outcomes. BJU Int. 2023, 132, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fankhauser, C.D.; Afferi, L.; Stroup, S.P.; Rocco, N.R.; Olson, K.; Bagrodia, A.; Baky, F.; Cazzaniga, W.; Mayer, E.; Nicol, D.; et al. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for men with testis cancer: a retrospective cohort study of safety and feasibility. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol D, Berney DM, Boormans JL, Di Nardo D, Frankhauser CD, Fischer S, et al. EAU Guidelines on Testicular Cancer. EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Paris 2024. ISBN 978-94-92671-23-3.

- Antonelli, L.; Heidenreich, A.; Bagrodia, A.; Amini, A.; Baky, F.; Branger, N.; Cazzaniga, W.; Clinton, T.N.; Daneshmand, S.; Djaladat, H.; et al. Primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in clinical stage 2a/b non-seminomatous germ cell tumour. BJU Int. 2024, 135, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, A.G.; Månsson, M.; Holmberg, G.; Fovaeus, M. Robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer at a national referral centre. BJUI Compass 2022, 3, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, J.M.; van der Poel, H.G.; Kerst, J.M.; Bex, A.; Brouwer, O.R.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; Horenblas, S.; Meijer, R.P. Clinical outcome of robot-assisted residual mass resection in metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumor. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soomro, N.A.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Porteous, A.J.; Ridley, C.J.A.; Marsh, W.J.; Ditto, R.; Roy, S. Systematic review of learning curves in robot-assisted surgery. BJS Open 2020, 4, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernar, L.I.M.; Robertson, F.C.; Tavakkoli, A.; Sheu, E.G.; Brooks, D.C.; Smink, D.S. An appraisal of the learning curve in robotic general surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 4583–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, G.; Goolam, A.S.; Perera, D.; Downey, R.; Leslie, S.; Grimison, P.; Woo, H.; Ferguson, P.; Ahmadi, N. Robotic-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for stage II testicular cancer. Asian J. Urol. 2024, 11, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).