1. Introduction

Laparoscopic urological surgery has undergone significant advancements and is now the standard approach for managing a wide range of urological conditions. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic techniques offer numerous benefits, including reduced morbidity, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and superior cosmetic outcomes. These advantages have led to the widespread adoption of laparoscopic surgery by both urologists and patients. However, this approach is not without risks, and complications, though rare, can be severe [

1,

2]. Among these, major vascular injury (MVI) is the most critical, often requiring immediate intervention and conversion to open surgery [

3,

4,

5]. This review focuses on the incidence, risk factors, and management strategies for MVI in laparoscopic urological surgery.

2. Incidence and Risk Factors

Vascular injuries are a common complication in laparoscopic urological surgeries, accounting for about half of all laparoscopic complications [

6]. MVI, though rare, is the most serious of these injuries, with an incidence ranging from 0.01% to 0.64% 7,8 . Despite its low frequency, MVI can be life-threatening and requires prompt recognition and management. The most commonly affected vessels include the abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, and their major branches, such as the iliac and mesenteric vessels [

9,

10].

Studies suggest that major complications in laparoscopic surgery are uncommon, with an overall incidence of about 2% [

7,

8,

11,

12]. Among these, vascular injuries are relatively rare, with an incidence ranging from 0.22% to 1.1% [

13]. However, they have a high mortality rate, accounting for 8% to 17% of deaths [

14]. Furthermore, most vascular injuries require immediate conversion to open surgery for repair [

15].

A study involving 5,347 patients who underwent laparoscopic urological surgery reported MVI in the abdominal aorta (2 patients) and the external iliac vein (1 patient) [

16]. Additionally, Cheng et al. identified MVI cases involving the renal artery (1 case), inferior mesenteric artery (2 cases), external iliac artery (1 case), common iliac artery (1 case), superior mesenteric artery (1 case), and the vena cava (7 cases) [

17].

MVI in laparoscopic urological surgeries most frequently occurs during initial laparoscopic entry, particularly with the insertion of the Veress needle or the first trocar [

18]. This can result in Veress needle puncture, significant blood loss, and air embolism [

19]. Other reported causes of MVI include excessive traction, ultrasonic scalpel injuries, Hem-o-lock clip disconnection or malfunction, and Endo-GIA stapler failure.

3. Management Strategies

Cheng et al. propose a systematic approach to managing MVI in laparoscopic urological surgery to minimize adverse outcomes [

17]. The following steps are recommended:

1. Rapid Identification and Control of Bleeding: Locate the injury site and control hemorrhage through clamping or compression.

2. Maintenance of Clear Visualization: Clear the surgical field to ensure optimal visibility after controlling bleeding.

3. Preparation for Resuscitation: Coordinate with support staff and prepare for fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion.

4. Adjustment of Pneumoperitoneum Pressure: Increase pneumoperitoneum pressure to reduce venous bleeding in certain cases.

5. Placement of Additional Trocars: Insert additional trocars to facilitate further intervention and repair.

6. Exposure and Dissection of Vessels: Adequately expose the injured vessel to prepare for subsequent repair.

7. Clamping and Suturing: Identify the exact bleeding site and perform clamping or suturing to achieve hemostasis.

8. Vessel Occlusion: Temporarily occlude the vessel using a bulldog clamp before repair.

Conversion to Open Surgery: Convert to open surgery if laparoscopic repair is not feasible or secure

MVI is an absolute surgical indication for immediate conversion to open surgery [

15]. Immediate laparoscopic or open repair of injured vessels is the most critical intervention [

20], while compression or clamping serves as an effective temporary measure [

21]. Therefore, the primary management strategies for MVI include rapid control of bleeding, repair of the injured vessel, and conversion to open surgery when necessary.

4. Prevention

Knowledge of anatomy in urological surgeries is one of the cornerstones in the prevention of vascular complications, especially in highly complex surgeries performed through minimally invasive approaches [

22]. This knowledge stems from both the surgeo

n’s experience and their skill. Therefore, we believe that due to the complexity of surgeries involving vascular components, such as retroperitoneal rescues and large renal masses [

23], these procedures should be performed by experienced surgeons. This situation underscores the need for residents and fellows to receive training for such scenarios, including simulation, artificial models, and assisting in surgeries [

24].

The concept of precision surgery has widely entered the urologic field. Urology encompasses interventions whose technique may differ according to individual features. These include not only the patient’s characteristics, which may vary and prompt different approaches, but also disease features (stage and invasion of closer structures) that should be preoperatively known to plan the most accurate and tailored strategy. During the last decade, three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction from 2D cross-sectional imaging has been given widespread attention and gained popularity among the urological scientific community [

25,

26,

27]. Three-dimensional models embody the concept of personalized precision surgery [

28], since they are derived from individual features and developed to tailor the intervention to the singular patient. The 3D virtual models provide the surgeon with a better understanding of the surgical anatomy of each case and also an opportunity to highlight anatomical details of interest.

Surgical planning is one of the primary roles of 3D imaging; it involves the creation of a customized surgical roadmap that increases the surgeons’ confidence and guides the decision-making process [

29].

5. Recommendation for Training and Simulation

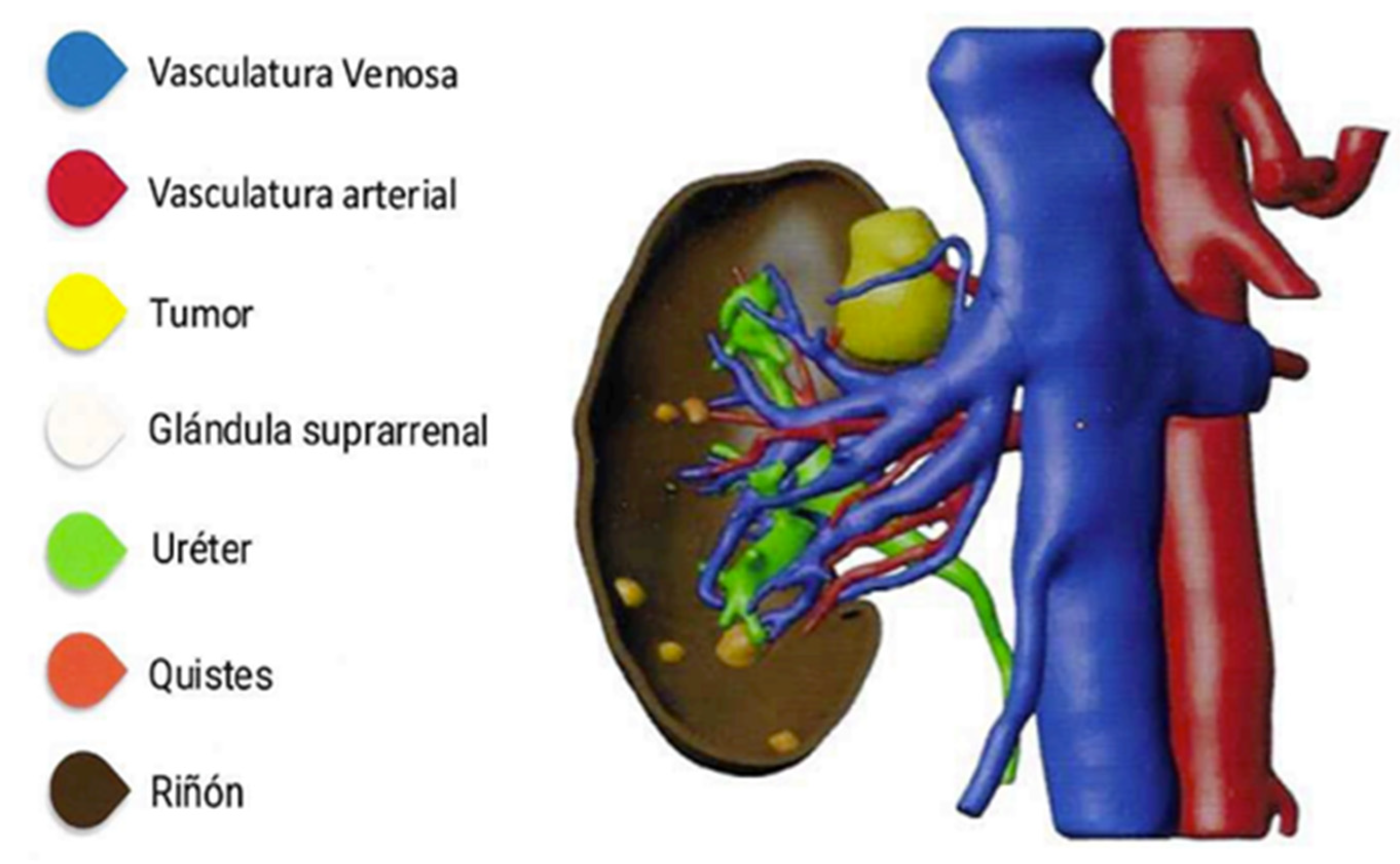

To further reduce the risk of MVI, surgical training should incorporate advanced simulation techniques, such as using 3D models for rehearsal and planning (

Figure 1). These programs can help improve surgical skills and reduce the likelihood of vascular injuries, particularly in high-risk procedures. Incorporating simulation-based learning, as well as providing hands-on experience in real surgeries, would be beneficial for residents and fellows [

25].

6. Conclusion

Major vascular injuries during laparoscopic urological surgery, though rare, represent a significant clinical challenge due to their potential for severe complications and high mortality rates. Early identification of the injury site, adherence to a structured management protocol, and consideration of the surgeon’s expertise are crucial to improving patient outcomes. Continued advancements in laparoscopic techniques, combined with enhanced training and awareness, are essential to further reduce the incidence and impact of MVI in urological practice. By prioritizing early recognition and systematic management, the risks associated with MVI can be minimized, ensuring safer and more effective laparoscopic urological surgeries.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Ignacio Castillón Vela for his generous and selfless contribution in providing images of 3D models used in his case studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Lin, Y.-H.; et al. Complications of Pure Transperitoneal Laparoscopic Surgery in Urology: The Taipei Veterans General Hospital Experience. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 70, 481 (2007).

- Guo, J. , Zeng, Z., Cao, R. & Hu, J. Intraoperative serious complications of laparoscopic urological surgeries: a single institute experience of 4,380 procedures. Int. braz j urol. 45, 739–746 (2019).

- Furriel, F. T. G. , Laguna, M. P., Figueiredo, A. J. C., Nunes, P. T. C. & Rassweiler, J. J. Training of European urology residents in laparoscopy: results of a pan-European survey. BJU Int 112, 1223–1228 (2013).

- Guillonneau, B.; et al. Proposal for a ‘European Scoring System for Laparoscopic Operations in Urology’. Eur Urol 40, 2–6; discussion 7 (2001).

- Ghavamian, R. Complications of Laparoscopic and Robotic Urologic Surgery. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

- Gaur, D. D. Retroperitoneal and pelvic extraperitoneal laparoscopy: an international perspective. Urology 52, 566–571 (1998).

- Makai, G. & Isaacson, K. Complications of Gynecologic Laparoscopy. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 52, 401 (2009).

- Saidi, M. H.; et al. Complications of major operative laparoscopy. A review of 452 cases. J Reprod Med 41, 471–476 (1996).

- Vascular trauma secondary to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: Laparoscopy. The American Journal of Surgery 135, 651–655 (1978).

- Major vascular injuries during laparoscopic procedures. The American Journal of Surgery 169, 543–545 (1995).

- Laparoscopic Entry: A Review of Techniques, Technologies, and Complications. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 29, 433–447 (2007).

- Azevedo, J. L. M. C.; et al. Injuries caused by Veress needle insertion for creation of pneumoperitoneum: a systematic literature review. Surgical Endoscopy 23, 1428–1432 (2009).

- Castillo, O. A. , Peacock, L., Vitagliano, G., Pinto, I. & Portalier, P. Laparoscopic repair of an iliac artery injury during radical cystoprostatectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 18, 315–318 (2008).

- Roviaro, G. C.; et al. Major vascular injuries in laparoscopic surgery. Surgical Endoscopy And Other Interventional Techniques 16, 1192–1196 (2002).

- Website. [CrossRef]

- Simforoosh, N.; et al. Major vascular injury in laparoscopic urology. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons 18, (2014).

- Management of major vascular injury in laparoscopic urology. Laparoscopic, Endoscopic and Robotic Surgery 3, 107–110 (2020).

- Dunne, N. , Booth, M. I. & Dehn, T. C. B. Establishing pneumoperitoneum: Verres or Hasson? The debate continues. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 93, 22–24 (2011).

- Lafullarde, T. , Van Hee, R. & Gys, T. A safe and simple method for routine open access in laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc 13, 769–772 (1999).

- Jafari, M. D. & Pigazzi, A. Techniques for laparoscopic repair of major intraoperative vascular injury: case reports and review of literature. Surg Endosc 27, 3021–3027 (2013).

- Li, P. , Mao, D., Zhou, J. & Sun, H. Management of inferior vena cava injury and secondary thrombosis after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a case report. J Int Med Res 49, 3000605211058868 (2021).

- Rogers, C. G. , Singh, A., Blatt, A. M., Linehan, W. M. & Pinto, P. A. Robotic partial nephrectomy for complex renal tumors: surgical technique. Eur Urol 53, 514–521 (2008).

- Gill, I. S.; et al. Comparison of 1,800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol 178, 41–46 (2007).

- Simhan, J.; et al. Perioperative outcomes of robotic and open partial nephrectomy for moderately and highly complex renal lesions. J Urol 187, 2000–2004 (2012).

- Piramide, F.; et al. Three-dimensional Model-assisted Minimally Invasive Partial Nephrectomy: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Eur Urol Oncol 5, 640–650 (2022).

- Checcucci, E.; et al. 3D imaging applications for robotic urologic surgery: an ESUT YAUWP review. World J Urol 38, 869–881 (2020).

- Cacciamani, G. E.; et al. Impact of Three-dimensional Printing in Urology: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. A Systematic Review by ESUT-YAUWP Group. Eur Urol 76, 209–221 (2019).

- Kang, S. K.; et al. DWI for Renal Mass Characterization: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Performance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205, 317–324 (2015).

- Sighinolfi, M. C.; et al. Three-Dimensional Customized Imaging Reconstruction for Urological Surgery: Diffusion and Role in Real-Life Practice from an International Survey. J Pers Med 13, (2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).