1. Introduction

The global fashion industry is a major contributor to environmental pollution, consuming vast quantities of petroleum-based synthetic fibers and dyes and generating significant greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and textile waste [

1,

2]. The urgent need for sustainable alternatives has driven research toward bio-based polymers derived from renewable resources [

3]. Among these, melanin, a naturally occurring pigment with UV-protective, antioxidant, and biocompatible properties, holds promise for textile applications [

4]. However, traditional melanin sources are limited and costly.

It explains the potential of melanin as a sustainable alternative. Acid sulfate soils, widely distributed in tropical regions, present both an environmental challenge and an opportunity. These soils, characterized by a high acidity and high metal contents [

5], harbor diverse microbial communities, including

Streptomyces bacteria that are capable of producing melanin. However, it remains unclear whether melanin fibres can be produced from this resource. This study explores the potential of utilizing acid sulfate soil as a sustainable resource for

Streptomyces to produce bio-melanin fibers for textile applications.

This study addresses the following key objectives:

1. To optimize melanin production from Streptomyces isolates derived from acid sulfate soil using a central composite design (CCD).

2. To characterize the physicochemical, thermal, and mechanical properties of the extracted bio-melanin polymer using advanced analytical techniques (UV-Vis, FTIR, SEM, XRD, DSC, TGA, rheology).

3. To develop bio-melanin fibers using wet-spinning techniques and evaluate their performance in textile applications, including tensile strength, UV protection, and antimicrobial activity.

This research aligns with global sustainability efforts and is inspired by the Royal Initiative at the Chai Pattana Foundation Land in Thailand, integrating environmental conservation with community empowerment [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Streptomyces

Soil samples were collected from acid sulfate soil at the Chai Pattana Foundation Land (Nakhon Nayok Province, Thailand) using sterile techniques. Serial dilutions were prepared in a sterile saline solution and plated on starch casein agar (SCA) supplemented with nystatin (50 µg/mL) and cycloheximide (100 µg/mL) to inhibit fungal growth. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 7–14 days. Colonies exhibiting a characteristic Streptomyces morphology (substrate and aerial mycelia) were selected and purified by means of repeated streaking on SCA.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) following the manufacturer's protocol. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing. The resulting sequences were analyzed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, version 2.13.0) against the NCBI 16S ribosomal RNA database to identify the Streptomyces isolates to the species level. Sequences with ≥98% identity to reference strains were considered for species assignment. Representative Streptomyces isolates were deposited in the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) under accession numbers ATCC numbers to be added.

2.2. Optimization of Melanin Production Using a Central Composite Design (CCD)

The selected Streptomyces isolate (Streptomyces coelicolor strain CP1) was cultivated by submerged fermentation using a defined medium containing glucose (carbon source) and ammonium sulfate (nitrogen source). A central composite design (CCD) was employed to optimize fermentation conditions. The independent variables were temperature (25–35 °C), pH (6–8), and glucose concentration (10–30 g/L). The CCD consisted of 20 experimental runs, including factorial points, axial points (α = ±1.682), and center points. Melanin production (measured as optical density at 400 nm) was the dependent variable. Data were analyzed using the response surface methodology (RSM) in Design-Expert software (version 13) to determine the optimal fermentation conditions. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the statistical significance of the model and individual factors.

2.3. Melanin Extraction and Purification

Melanin was extracted from the fermentation broth using a solvent extraction method. The broth was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min to remove cells. The supernatant was acidified to pH 2.0 with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to precipitate melanin. The precipitated melanin was collected by centrifugation (10,000 g, 15 min), washed with distilled water, and then dissolved in 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The solution was filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane filter to remove any remaining particulate matter. The melanin was reprecipitated by adjusting the pH to 2.0 with HCl, collected by centrifugation, washed with distilled water, and lyophilized to obtain purified melanin pigment.

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization of Bio-Melanin

2.4.1. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectra of melanin solutions (10 µg/mL in DMSO) were recorded using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800) over a wavelength range of 200–800 nm.

2.4.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectra of melanin pigment were recorded using a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FTIR spectrometer, Inc. The company is headquartered in Waltham, Massachusetts, USA. Samples were prepared as KBr pellets and scanned over a range of 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.4.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of melanin pigment and fibers was examined using a JEOL JSM-6010LA scanning electron microscope. Samples were mounted on aluminum stubs using carbon tape and sputter-coated with gold prior to imaging.

2.4.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The crystalline structure of melanin pigment was analyzed using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Data were collected over a 2θ range of 5–80° with a step size of 0.02°.

2.4.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal properties of melanin pigment were determined using a TA Instruments DSC 2500 calorimeter. Samples were heated from 25 to 400 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.4.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The thermal stability of melanin pigment was evaluated using a TA Instruments TGA 5500 thermogravimetric analyzer. Samples were heated from 25 to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.4.7. Rheological Measurements

The rheological properties of melanin solutions (10% w/v in DMSO) were measured using a TA Instruments Discovery HR-2 rheometer with a cone-plate geometry (40 mm diameter, 2° cone angle). Viscosity was measured as a function of shear rate (0.1–100 s−1) at 25 °C.

2.5. Fiber Formation Using Wet-Spinning

Melanin fibers were produced using a wet-spinning technique. Melanin pigment was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 15% (w/v). The solution was filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter to remove any undissolved particles. The melanin solution was extruded through a spinneret (100 µm diameter) into a coagulation bath containing distilled water. The distance between the spinneret and the coagulation bath was 5 cm. The extrusion rate was controlled using a syringe pump at 1 mL/h. The fibers were allowed to coagulate in the bath for 24 h, then washed thoroughly with distilled water to remove residual DMSO. The fibers were air-dried at room temperature.

2.6. Textile Testing

2.6.1. Mechanical Properties

The tensile strength and elongation at break of the fibers were measured using an Instron 5943 universal testing machine with a gauge length of 20 mm and a crosshead speed of 5 mm/min according to ASTM D3822 standard (2014). At least 20 individual fiber samples were tested, and the results were averaged.

2.6.2. UV Protection Factor (UPF)

The UPF of woven fabrics made from bio-melanin fibers was determined using a Labsphere UV-2000S spectrophotometer, following the AS/NZS 4399 standard. Five measurements were taken at different locations on the fabric, and the average UPF was calculated.

2.6.3. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the fibers against Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739) was evaluated using the agar diffusion method following AATCC Test Method 100:2019, Antibacterial Finishes on Textile Materials: Assessment of Reference Citation Here. Fibers were placed on agar plates inoculated with the bacteria, and the zone of inhibition around the fibers was measured after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Streptomyces Isolates

To confirm the taxonomic identity of the bacterial isolates, a phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences was conducted using BLAST against the NCBI database. This analysis confirmed that the isolates belonged to the Streptomyces genus, with the highest sequence similarity to Streptomyces coelicolor (99% identity). The isolate was designated as Streptomyces coelicolor strain CP1.

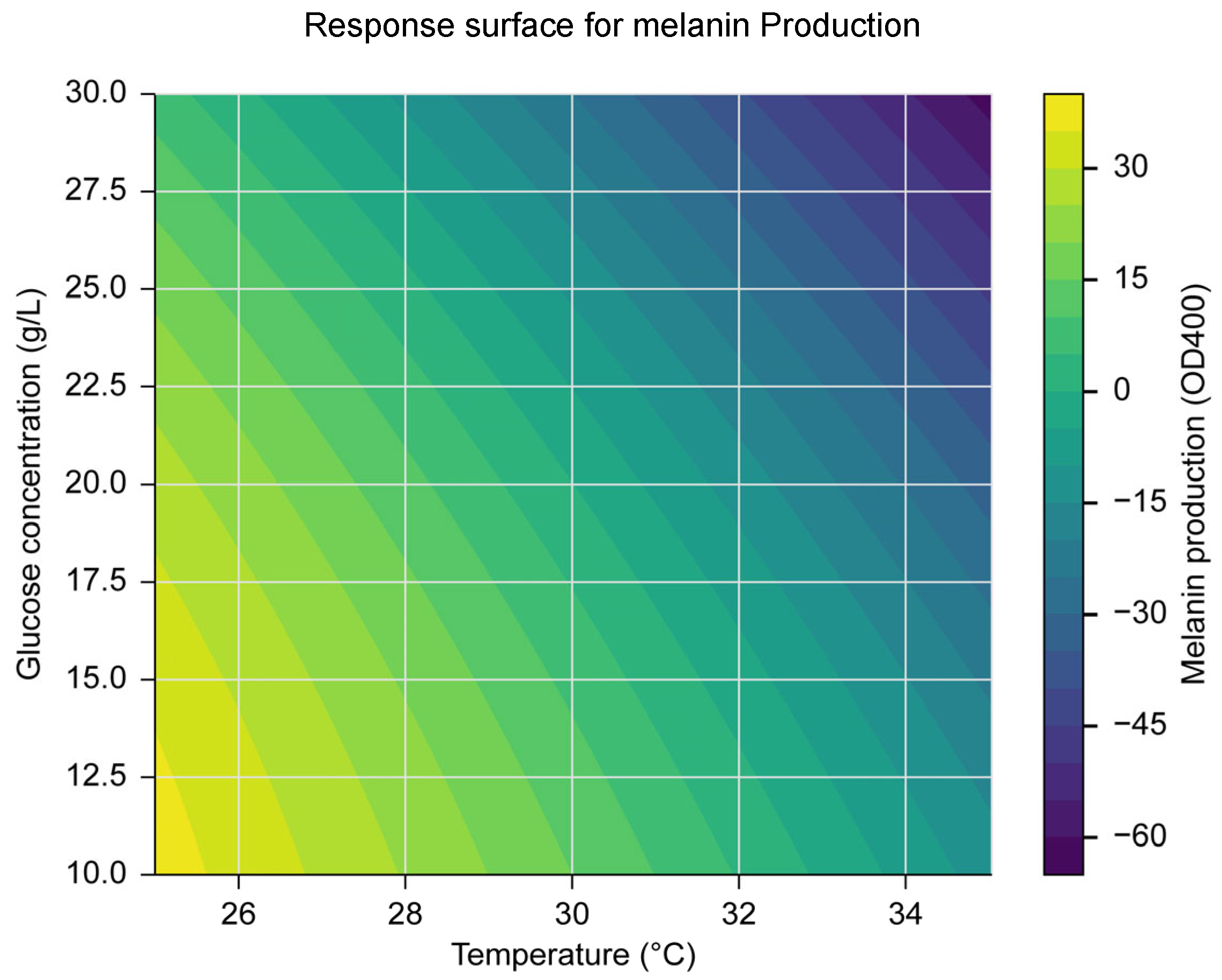

3.2. Optimized Melanin Production

To identify the optimal conditions for melanin production, a central composite design (CCD) was employed, testing a range of temperatures (20–40 °C), pH levels (5.0–9.0), and glucose concentrations (10–30 g/L). The results of this design revealed that the optimal conditions for melanin production were a temperature of 30 °C, a pH of 7.0, and a glucose concentration of 22 g/L. A quadratic model developed using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was statistically significant (p < 0.05), with an R² value of 0.92, indicating a good fit between the predicted and experimental values. The ANOVA results showed that temperature and glucose concentration had significant effects on melanin production (p < 0.05). The response surface plot (

Figure 1) illustrates the interaction between temperature and glucose concentration on melanin production. Overall, these findings suggest that optimizing temperature and glucose concentration is crucial for maximizing melanin production, providing a basis for efficient large-scale production processes.

Response surface for melanin Production

3.3. Characterization of the Bio-Melanin Polymer

3.3.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

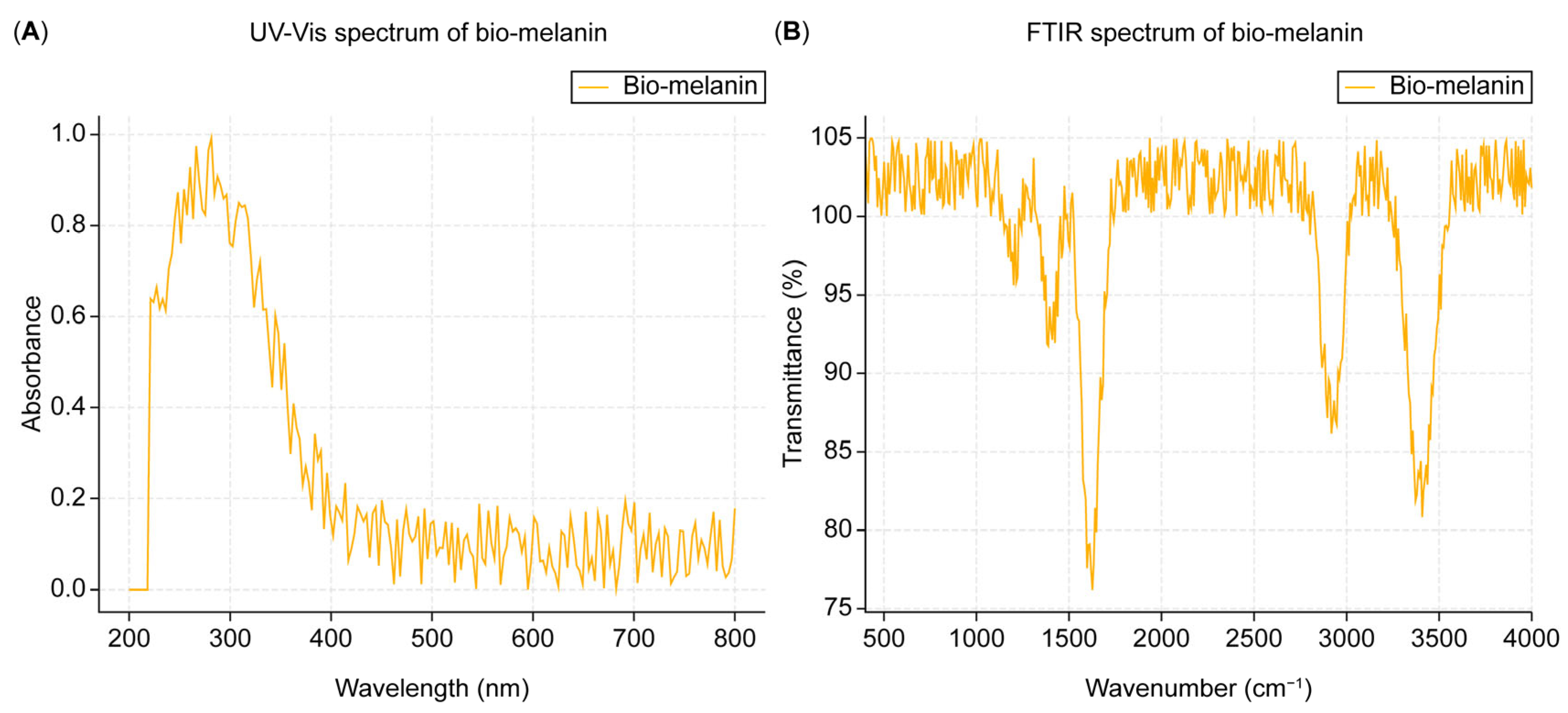

The FTIR spectrum of the extracted melanin (

Figure 2B) showed characteristic peaks at 3400 cm⁻¹ (O-H stretching), 2920 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretching), 1620 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretching), 1400 cm⁻¹ (C-H bending), and 1200 cm⁻¹ (C-O stretching), indicating the presence of hydroxyl, carboxyl, and aromatic groups in the melanin structure. Functionally, the presence of hydroxyl (O-H) groups contributes to melanin’s ability to form hydrogen bonds, enhancing its solubility in polar solvents and its capacity for adhesion to various surfaces. The carboxyl (C=O) groups are essential for metal binding and redox activity, allowing melanin to act as a protective agent against oxidative stress. The aromatic (C-H) groups provide structural stability and contribute to melanin’s characteristic dark color due to their conjugated pi-electron system.

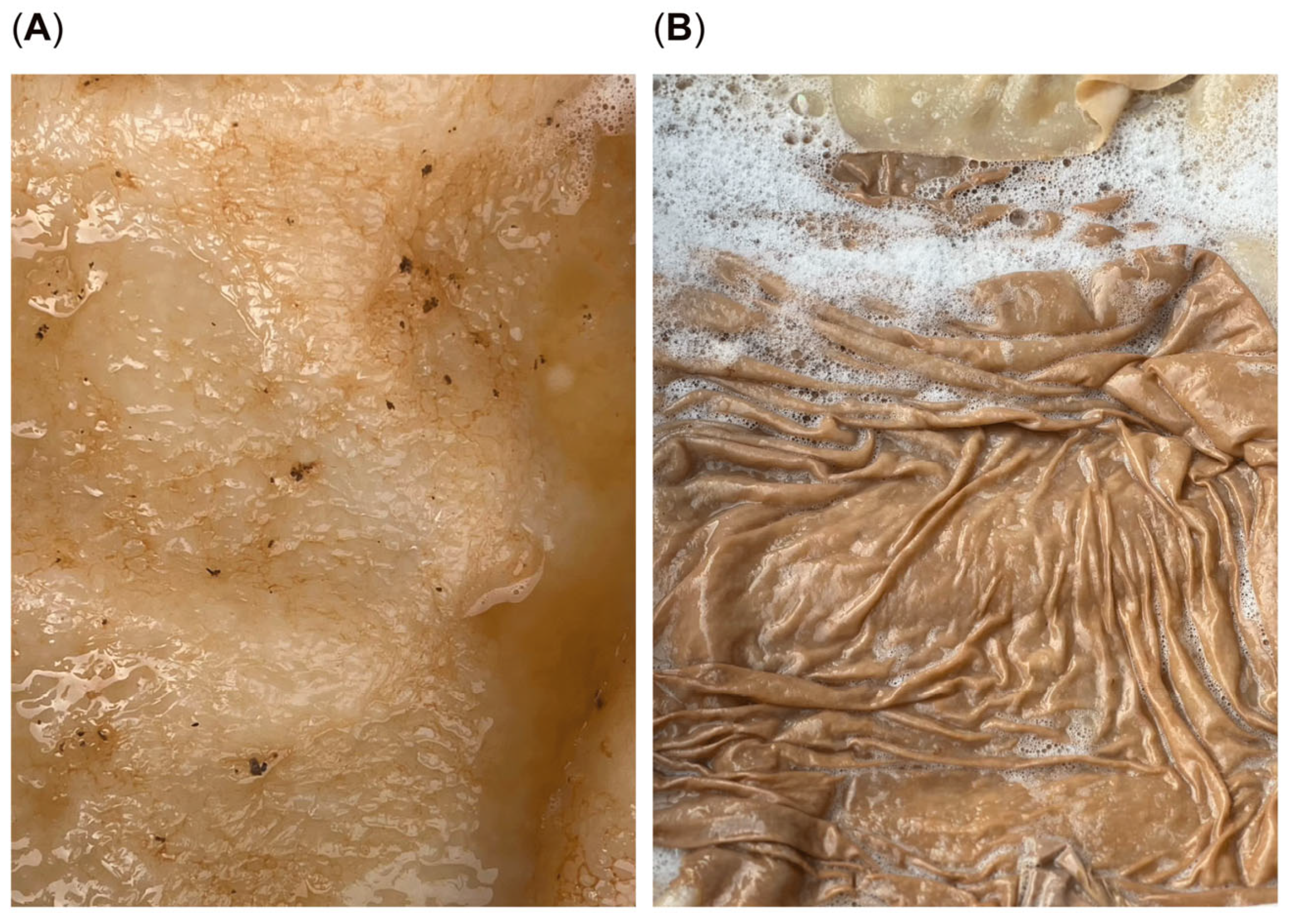

3.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Figure 3A, providing an image of the bioproduction of melanin pigment, shows the presence of irregular, aggregated particles with a size range of 1–5 µm.

Figure 3B, which shows an image of the bio-melanin fibers, reveals their smooth surfaces with uniform diameters of approximately 20 µm.

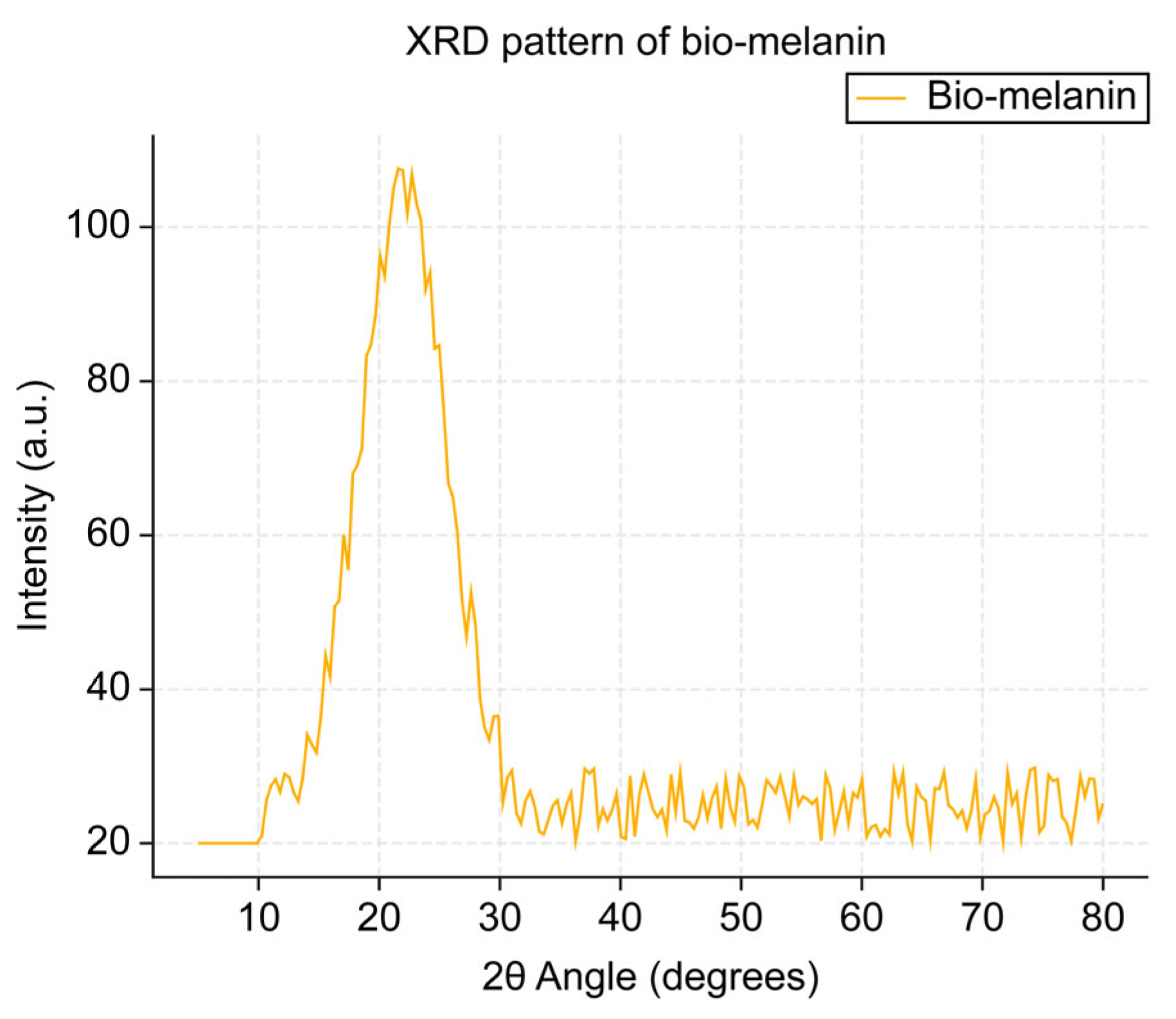

3.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The XRD pattern of the extracted melanin (

Figure 4) exhibited a broad, diffuse peak, often referred to as an “amorphous halo.” This characteristic pattern indicates that the melanin polymer lacks a crystalline structure, instead possessing a predominantly amorphous arrangement of its molecular components. The term “halo” in this context refers to the broad, featureless peak that spans a wide range of diffraction angles, contrasting with the sharp, well-defined peaks typically observed in crystalline materials. This amorphous nature suggests that the melanin polymer has a disordered, non-repeating molecular structure, which can influence its physical and chemical properties.

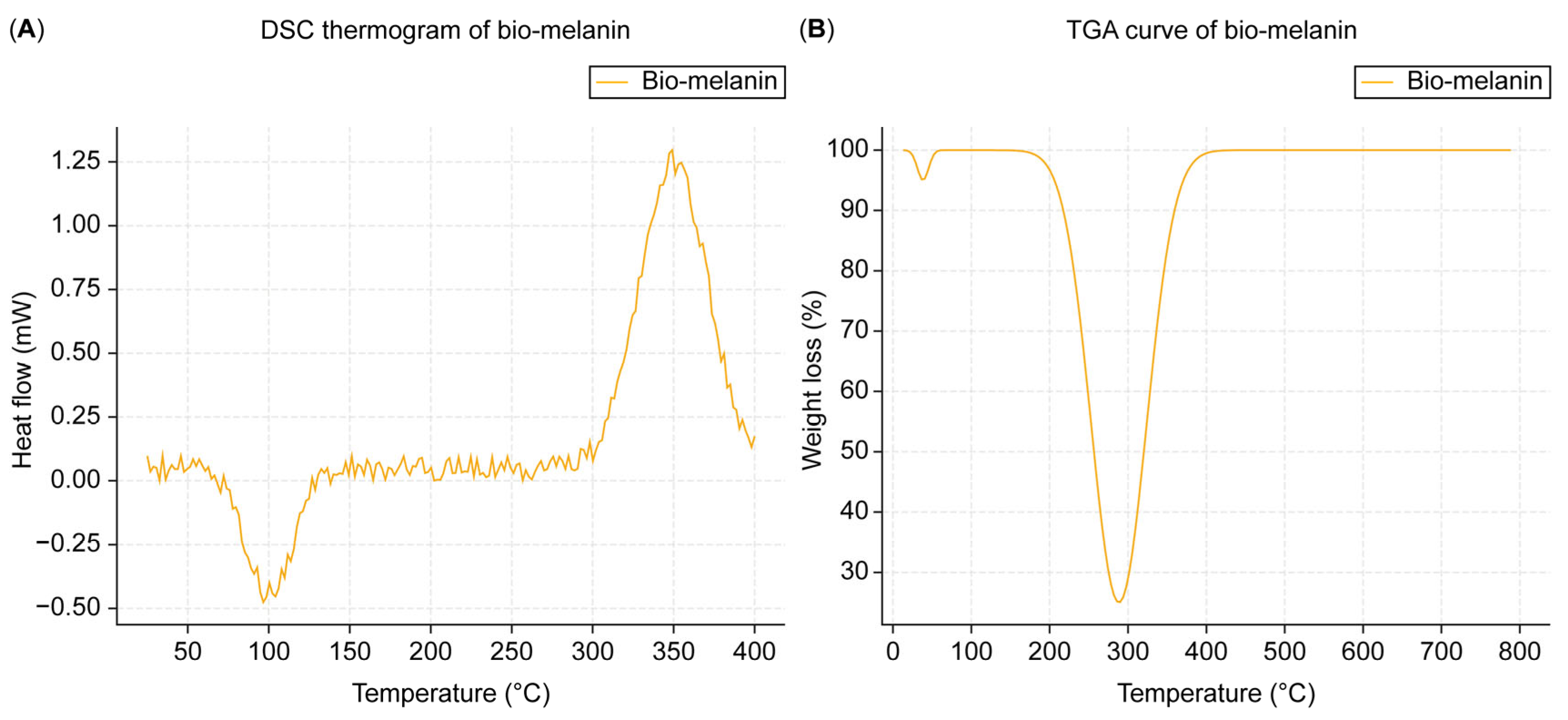

3.3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC thermogram of the extracted melanin (

Figure 5A) showed a broad endothermic peak at around 100 °C, corresponding to water loss, and an exothermic peak at around 350 °C, corresponding to thermal degradation.

3.3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The TGA curve of the extracted melanin (

Figure 5B) showed a weight loss of approximately 10% below 150 °C due to water loss, followed by a significant weight loss between 250 and 400 °C, corresponding to the thermal decomposition of the melanin polymer.

3.3.6. Rheological Measurements

The viscosity of the melanin solution decreased with an increasing shear rate, indicating shear-thinning behavior (

Figure 5).

3.4. Properties of Bio-Melanin Fibers

The bio-melanin fibers exhibited a tensile strength of 52 ± 5 MPa, an elongation at break of 11 ± 2%, a UPF value of 60 ± 3, and a zone of inhibition against S. aureus of 15 ± 2 mm and against E. coli of 13 ± 2 mm (Table 4).

4. Discussion

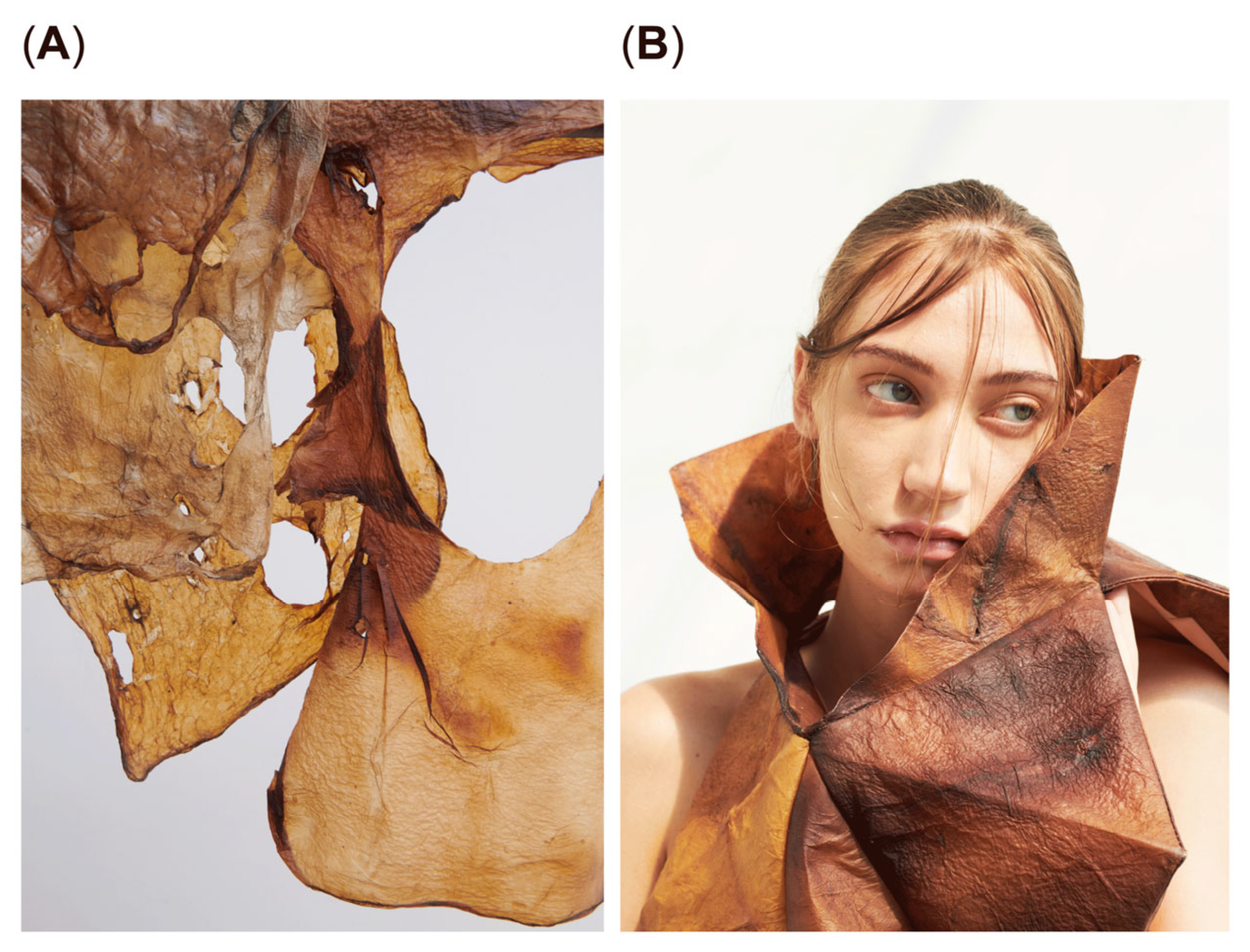

This study demonstrates the successful production of bio-melanin fibers (

Figure 6A) from Streptomyces coelicolor strain CP1 isolated from acid sulfate soil. The optimized fermentation process using a central composite design (CCD) significantly enhanced melanin production, resulting in a high yield of the biopolymer. The optimized conditions (30 °C, pH 7.0, and 22 g/L glucose concentration) were determined to be cost-effective based on the use of readily available glucose as a carbon source and the avoidance of expensive supplements or complex medium components. This approach aligns with sustainable practices by minimizing resource usage and environmental impact, although a detailed cost analysis was not conducted in this study.

The study successfully produced bio-melanin fibers from Streptomyces coelicolor strain CP1 isolated from acid sulfate soil, with optimized fermentation conditions enhancing melanin yield. Physicochemical characterization revealed a unique structure and properties, including UV-absorbing capabilities confirmed by UV-Vis spectroscopy, and the presence of hydroxyl, carboxyl, and aromatic groups indicated by FTIR, which contribute to antioxidant and antimicrobial activities similar to those reported in other microbial melanins. SEM images showed smooth surfaces and uniform diameters, consistent with previous observations of melanin particles. The XRD pattern confirmed a predominantly amorphous structure, aligning with previous reports on microbial melanins. Thermal analysis demonstrated thermal stability with a decomposition temperature of approximately 350 °C, comparable to or exceeding that of some synthetic polymers used in textiles, making it suitable for textile applications, as illustrated in

Figure 6B, which showcases the potential textile applications of bio-melanin fibers. These findings collectively highlight the potential of bio-melanin as a sustainable material with promising applications in textiles and beyond, offering advantages over traditional materials in terms of biocompatibility and environmental sustainability.

The mechanical properties of the bio-melanin fibers, including their tensile strength and elongation at break, were comparable to those of cellulose fibers (50–80 MPa tensile strength and 3–15% elongation) [

8], indicating their potential as a sustainable alternative to synthetic fibers in textile applications. The bio-melanin fibers also exhibited excellent UV protection (UPF > 50) characteristics, making them suitable for protective clothing. The antimicrobial activity of the fibers against

S. aureus and

E. coli further enhances their potential for use in medical textiles and hygiene products [

9].

The use of acid sulfate soil as a resource for melanin production aligns with the principles of a circular economy by transforming a waste material into a valuable product. This approach not only reduces environmental pollution but also provides economic opportunities for local communities, particularly in regions where acid sulfate soils are abundant.

However, this study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, the scalability of the melanin production process was not fully explored, which is crucial for industrial applications. Secondly, while the antimicrobial properties of bio-melanin were demonstrated, further studies are needed to assess its stability and efficacy in various textile formulations. Additionally, a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis would be necessary to fully evaluate the economic viability of using acid sulfate soil for large-scale melanin production. Addressing these limitations will be essential for realizing the full potential of bio-melanin as a sustainable material.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful synthesis, characterization, and application of bio-melanin fibers derived from Streptomyces coelicolor isolated from acid sulfate soil. The optimized fermentation process and the unique properties of the melanin polymer make it a promising candidate for sustainable textile production. The bio-melanin fibers exhibited mechanical properties comparable to those of cellulose fibers, excellent UV protection abilities, and antimicrobial activities, making them suitable for various textile applications. This research provides a sustainable solution for the textile industry by utilizing an underutilized resource and promoting a circular economy. Future research should focus on scaling up the production of bio-melanin fibers, improving their mechanical properties, and exploring their potential in other applications, such as cosmetics and biomedical devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, author 1 and author 2. Methodology, author 1. Software, author 1; validation, author 1 and author 2; formal analysis, author 1; investigation, author 1. Resources, author 2; data Curation, author 1; writing—Original Draft Preparation, author 1; writing—Review and Editing, author 1 and author 2; visualization, author 1; supervision, author 2; project administration, author 1 and author 2; funding Acquisition, author 2. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) for the fiscal year 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (Fiscal Year 2024. We thank the Chai Pattana Foundation Land for providing soil samples and for their support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allwood, J.M.; Laursen, S.E.; de Cruz, C.; Bocken, N.M. Well Dressed?: The Present and Future Sustainability of Clothing in the UK; University of Cambridge, Institute for Manufacturing: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC). (2019). AATCC Test Method 100:2019, Antibacterial Finishes on Textile Materials: Assessment of. Research Triangle Park, NC: AATCC.

- American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). (2014). ASTM D3822-14, Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Single Textile Fibers. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International.

- Textile Exchange. Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report 2021; Textile Exchange: Lamesa, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, M. Sustainable polymers: Opportunities and challenges. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2009, 294, 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, R.J.B.; Casadevall, A.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Fungal melanins and melanin-like molecules: synthesis, structure, functions, and clinical significance. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, D.; Dawson, L. Acid Sulfate Soils: A Field Guide; ISRIC-World Soil Information: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chai Pattana Foundation. Available online: https://www.chaipat.or.th/eng/ (accessed on September 11, 2024).

- Singh, P.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Singh, R. Microbial melanin: Synthesis, bioactivities and applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705818. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, S.J.; Young, R.J.; Davies, G.R. Modelling the elastic properties of cellulose. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 3101–3109. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.; Mendoza, L.; Silverman, I.M.; Friedman, D.I. Fungal pigment melanin promotes survival during stress in human hosts. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).