1. Introduction

Music is a form of art which involves an arrangement of sound and tones, and it has been long integrated with human societies. Its creation and performance shape and play a bigger role in human culture. The book titled “The Origins of Music”, pinpointed how music provides insights into human evolution, evidenced using tones on many social behaviours including rituals, praying, courting, and marrying [

1]. In addition, the authors also argued on the similarity of music to human language, even on its effect on human physiological functions. Within this subset of interest, a song is a type of music that consists of words and melody. The primary purpose of song composition is amusement as well as profit and thus songs are classified as literary works, being created by lyricists and composers within protection of copyright laws.

Songs have been viewed in social norms as a means for individuals to display their culture and distinguish one group of people apart from another [

2]. One of the most influential cultural movements in the realm of music is the rise of rap culture, which was initiated in the 1970s and reached its peak during the early 1990s. Hip-hop, another term used to identify rap music, is characterized by rhythmic speech, lyrical creativity, and a focus on socio-political commentary, used in expressing the struggles faced by young African Americans in those years [

3]. Rap and hip-hop lyrics frequently use derogatory and subordinating language to objectify, devalue, or oppress women [

4]. This is seen by the way that women are sexualized in music videos, which adds to the sexual objectification of women’s bodies. Nevertheless, the authors did not limit their analysis to the rap genre. As the statistical significance accepted the hypothesis suggesting the interrelationship between genres and derogatory topics, it is proven that other musical genres include obscene themes in their lyrics as such pop music.

Media plays an important role in shaping the experiences, perceptions, and behaviours of young people. Media influences younger males’ impressions of women, indicated by negative attitudes to women in positive roles shown by middle school-aged boys who had more exposure to mainstream media [

5]. Exposure to sexually explicit content has detrimental effects on children. Male adolescents who were exposed to sexual music lyrics have a higher sexting tendency [

6]. In comparison to pop listeners, rock enthusiasts showed a similar trend, with the former showing the largest peak of depression tendency throughout their teenage years. Additionally, this category has a greater susceptibility toward drug use and aggressive behavior [

7]. Hence, it becomes imperative to consider the potential consequences of media exposure on the well-being of the younger generation to ensure they can engage with media in a responsible and informed manner.

Technology advancements have already caused a shift in digital music media. The transition from ownership to access-based consumption has occurred in several industries due to high-speed network connectivity and the widespread use of smartphones and other mobile devices [

8]. Streaming services such as Spotify and Rhapsody have degraded the sales of ownership-based downloading [

9]. Consequently, this ease of access has extended to various age groups, including children, who now find themselves navigating through diverse and limitless selections of content. In this context, the importance of robust content moderation and explicit lyric filtering mechanisms becomes prominent. Implementation of explicit or inappropriate content filtering ensures a safer and more age-appropriate digital music experience.

The presence of sophisticated technologies, especially in artificial intelligence, allows advancements in music production, distribution, and consumption. One of the most developed technologies being applied in music streaming applications is the recommendation engine. In this system, a music curator compiles a playlist or soundtrack with songs that have a common tone and mood [

10]. Additionally, the system is also capable of giving recommendations based on similarity among users which fundamentally assumes that those users are more likely to have common music taste. In the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP), song lyrics are used in information retrieval and applied in different contexts. Lyrics can also be used to recognize genre which can be applied as additional input in the recommendation engine [

11]. In the business part of streaming platforms, sentiment analysis on users’ reviews was used to determine the market positioning of the platforms [

12]. In alignment with regulatory standards and to foster a secure user experience, explicit content filtering by using lyrics has been employed through various methods [

13]. These applications showcase the versatile integration of artificial intelligence across the music industry, not only ensuring users experience music in a way that aligns with their preferences but also adhering to regulations that make it suitable for all audiences, especially children, by filtering out explicit content.

The deteriorating effect of explicit content exposure to younger demographics and abundant numbers of easily accessible age-restricted songs pose a challenge for streaming service companies to deal with content moderation. Hence, there seems to be a need to leverage advanced techniques to effectively deal with content moderation, particularly through the analysis of easily obtainable lyrics. Classification algorithms can discover intricate relationships in the lyrics dataset, distinguishing between explicit and non-explicit elements. In addition, the analysis can further be enhanced by incorporating genre-specific features, resulting in a refined precision of content identification. The outcome of this study is to ensure a safer and more enjoyable digital music experience.

This study aims to develop and evaluate advanced machine learning techniques for the effective management, classification, and visualization of Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) data, drawing inspiration from content moderation approaches used in the music industry. By leveraging ICT tools for automated data processing, classification, and visualization, the study aims to compare two classification approaches— a two-stage classification method and a genre-incorporated dataset method— for differentiating explicit and non-explicit lyrics, with the goal of improving content moderation accuracy and providing a safer music experience, particularly for younger listeners.

2. Literature Review

Song lyrics as unstructured data can be used as input for machine learning models after going through data preparation processes. Salam et al. classified the toxicity of songs by labelling songs with explicit content [

14]. Random Forest gave the best performance in terms of accuracy and f1-score, standing at 93.52% and 94% on a balanced dataset, compared to Logistic Regression and XG Boost. Libraries that are used in pre-processing steps in Natural Language Processing are usually provided in the English language. However, this does not limit the study on explicit content moderation to be constructed by autonomous machine learning algorithms. Chin et al. conducted a study to filter out songs with the label ‘Unqualified (Fail) for broadcasting’ gathered by the South Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) [

15]. The work started with data collection and labelling of ‘Pass’ and ‘Fail’ for every observation, resulting in a dataset consisting of around 27 thousand lyrics. Only several parts of speech (POS) were used before the transformation of lyrics into TF-IDF vector. Tree-based classification algorithms, Adaboost and Bagging, were employed with input datasets of both full-sized vectors and selected vocabulary. The best performance was observed in the dataset with selected vocabulary using Bagging where precision, recall, and f1-score for ‘Fail’ stood at 0.70, 0.55, and 0.62 respectively. Some explicit songs were not easily identified by machine learning algorithms as they contained metaphorical expressions.

The incorporation of additional data is proven to improve the performance of explicit content classification. Bergelid included music metadata that was provided by Spotify API to enhance the performance of machine learning algorithm in differentiating songs with explicit remarks [

16]. The metadata included the artist’s name, release year, energy, and valance. The study compared two datasets, the first containing only lyrics while the other had metadata being incorporated, to determine possible performance differences by the addition of these data. Better performance of the Random Forest model was observed in the balanced dataset with metadata where precision, recall, and f1-score of 0.926, 0.758, and 0.834 compared to those using lyrics only of 0.917, 0.751, and 0.826.

The interrelation between genre and explicitness may be apparent in the study by Mayerl et al. where in their work, the aim was to build a genre classification model [

17]. The work started with the random assignment of genre to the observation which became the baseline model to be compared to other models being built in their work. Textual features were derived from song lyrics which included token count and stop word ratio. Lyrics were also being used by transforming them into TF-IDF vectors along with 25-topics Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). The genre classification model with the use of at least one feature outperformed the line model where the best performance was observed in the model using TF-IDF vector as its feature. This finding highlighted the possible relationship between lyrics and genre. As the f1-score increased from 0.156 to 0.179 in the model using only explicit flags, it also occurred that explicitness may be inherited in the genre. In addition, previous works which are related to explicit lyrics detection and genre classification along with the resulting model performance are listed in

Table 1 [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

3. Materials and Methods

In this project, we utilize a secondary dataset that is sourced from the open-source repository Kaggle.com. This dataset provides a comprehensive foundation for our analysis. Additionally, we enrich our data by obtaining the explicit content flag from the Spotify API, ensuring we capture the necessary attributes related to song explicitness. To further enhance our dataset, we scrape genre-related data from the Last.fm API. This multi-source approach allows us to incorporate diverse and relevant information, enhancing the robustness and depth of our analysis. A summary of the dataset is presented in

Table 2, showcasing the various attributes and their sources. This integrative method ensures a well-rounded dataset, providing a solid basis for our research.

When dealing with unstructured data such as song lyrics, several meticulous data preparation steps are necessary before the data can be utilized as input for model building. The data preparation process begins with language filtering to remove all non-English instances, ensuring that only relevant lyrics are retained for analysis. This step is crucial because language variations can introduce noise and inconsistencies in the dataset. Following language filtering, the next step involves converting all text to lowercase. This standardization helps in treating words like ’Love’ and ’love’ as the same entity, thereby reducing redundancy. After lowercasing, contractions such as “can’t” and “won’t” are expanded to their full forms (“cannot” and “will not”), which aids in maintaining consistency in the dataset.

Subsequently, punctuation and symbols are removed from the text. This step helps in cleaning the data and preventing non-alphanumeric characters from interfering with the analysis. The clean text is then tokenized, breaking down the sentences into individual words or tokens. Tokenization is a fundamental step that prepares the text for further processing and analysis. Once tokenized, stopwords—common words such as ’and’, ’the’, and ’is’ that carry little semantic value—are removed from the text. This removal enhances the model’s focus on more meaningful words that contribute to the context and sentiment of the lyrics. Lemmatization follows, where words are reduced to their base or root forms (e.g., ’running’ to ’run’), ensuring that variations of a word are treated uniformly.

The processed textual data is then transformed into a numerical representation, as most machine learning models require numerical inputs. One common method for this transformation is Term Frequency - Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF). TF-IDF converts the text into a sparse vector matrix, where each entry represents the importance of a word in a document relative to the entire dataset. This technique helps in highlighting significant words while downplaying the common ones, thus improving the model’s ability to discern patterns and relationships in the data.

Accuracy:

Accuracy quantifies the proportion of properly predicted cases to all predictions the model has made. Nevertheless, it might not be a useful statistic in datasets where one class significantly outnumbers the other as it may mislead to a higher value due to a higher likelihood of correctly predicting the majority class.

Precision

Assesses the reliability of the model by calculating the ratio of true positive predictions to the total positive predictions (true positives and false positives). High precision indicates a model’s accuracy in predicting positive instances.

Recall

Measures the model’s ability to identify all positive instances in the dataset by dividing true positives by the sum of true positives and false negatives.

F1-score

The F1-Score is a valuable metric for evaluating datasets with an imbalanced class distribution where the calculation is based on both precision and recall.

The process begins by transforming textual lyrics into numerical representations using TF-IDF vectorization, resulting in a sparse matrix with high-dimensional columns representing words. Data preprocessing reduces the number of distinct expressions by removing unusable and meaningless words.

In the baseline model, various machine learning models, including Random Forest, SVM, and Naïve Bayes, are trained using the lyrics-only dataset. This dataset is represented as a sparse TF-IDF vector, and an 80-20 train-test split is used, with stratification to address data imbalance. Predictions on the test set are made using the predict() function. To further improve the performance of the models on imbalanced data, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) is utilized to artificially create additional data for the minority class, ensuring a more balanced dataset.

The two-stage classification approach combines the outputs of a dictionary-based method with those of machine learning. Initially, predictions are generated using a predefined dictionary of explicit words, returning a 1 if any word exists in the input text, and 0 otherwise. For all negative predictions (0) made by the machine learning model, these predictions are updated based on the dictionary-based method. The final results are stored in a data frame y_pred_final, providing a more robust prediction mechanism by leveraging both approaches.

In the genre-incorporated model, both lyrics and genre are included as input variables. Since both come in textual format, they are transformed into numerical representations using TF-IDF vectorization, resulting in two separate sparse matrices. These matrices are then combined horizontally using the hstack function. The model training and prediction processes are like those of the baseline model, utilizing the sklearn library. Additionally, SMOTE is applied to obtain a balanced dataset, ensuring that the model is trained on a representative sample of data. The results of this genre-incorporated model are then evaluated and compared to those of the baseline and two-stage classification models.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Two-Stage Classification

The aim of building a two-stage classification is to obtain a model that is robust and less affected by class imbalance that always exists in explicit songs. It involves a lookup dictionary, containing numerous explicit terms. Two-stage classification refines the negative output from the baseline model by comparing every non-explicit predicted lyric with a dictionary lookup. If any of these lyrics contain one of these terms, the prediction is changed into positive (explicit). This means that the second stage has more discriminatory power and results in a higher number of captured true positives (higher recall compared to the baseline model). However, this comes with the cost of much lower precision. This happens because the dictionary-based approach is relatively simplistic and does not account for context or nuance. For instance, words that might be explicit in certain contexts could appear in non-explicit lyrics without any inappropriate connotation. The word “bastard” would be interpreted differently based on the context where “You bastard!” is considered offensive while “He’s a lucky bastard for winning the lottery” is often used more light-heartedly and may not be considered explicit in the same way. As a result, lyrics that are not explicit may be incorrectly flagged as explicit, reducing the overall precision of the model. The performance of the two-stage classification method is shown in

Table 3.

3.2. Genre Incorporated Model

17 different genres can be associated with every song lyric in which every observation can belong to more than one genre. This genre information is encoded using a Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer. The TF-IDF representation of the genres is then concatenated with the TF-IDF matrix of the lyrics, resulting in an additional 17 columns in the sparse input matrix. The performance of machine learning models trained on this dataset is detailed in

Table 4. The models are evaluated based on metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. Notably, the models trained on imbalanced data are compared against those trained on sampled oversampled datasets denoted by “S.”. Three machine learning algorithms are considered namely Random Forest “RF”, Support Vector Machine “SVM”, and Multinominal Naïve Bayer “MNB”. Lyrics only dataset is denoted as “L” while those with genre-incorporated are “LG”.

As observed from

Table 4, each algorithm that is trained on a dataset enriched with genre-related features has better performance in terms of their F1-Score compared to their counterparts. This signifies a finding by Mayerl et al. in which they pinpointed the possible correlation between lyrical features and genre [

17]. Genres often capture semantic relationships between songs, including themes and topics that are common within explicit lyrics. For example, certain themes related to explicit content might be more commonly observed in hip-hop compared to country music. Additionally, certain explicit words or phrases might be common in one genre but rare in another, and the genre information helps the model account for these differences. By leveraging these semantic relationships, the model can learn more robust and nuanced decision boundaries, leading to improved classification performance. It can better understand the context in which explicit content appears, making more accurate predictions.

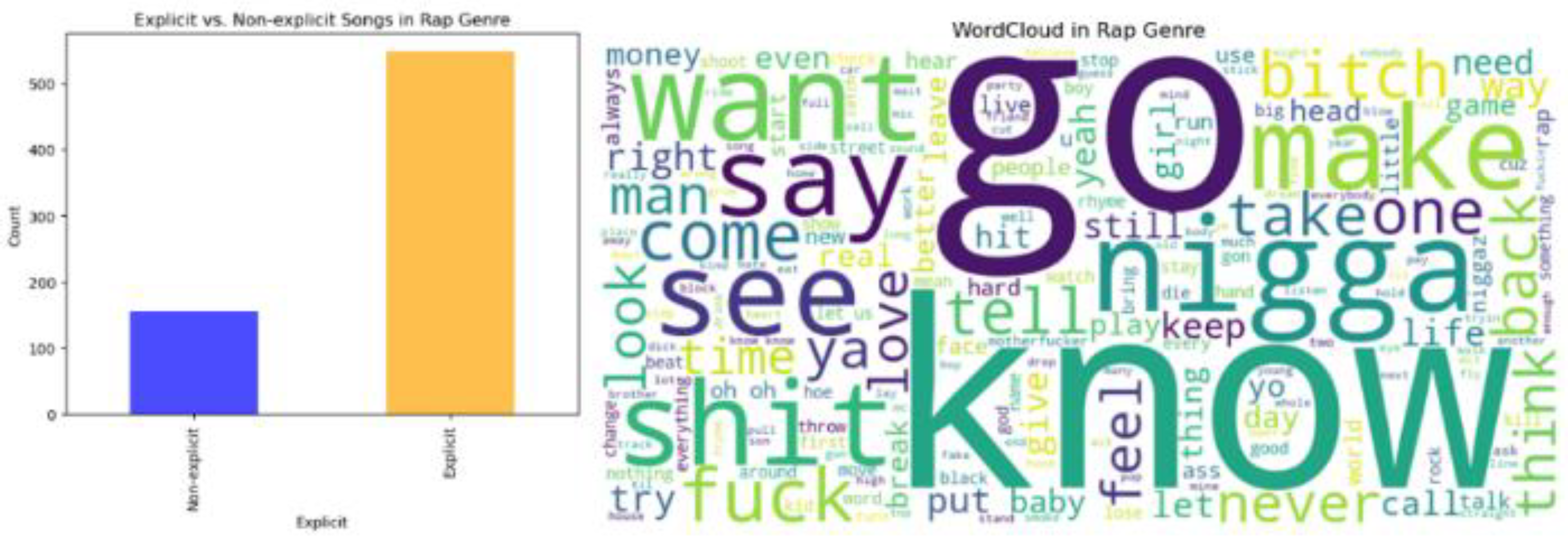

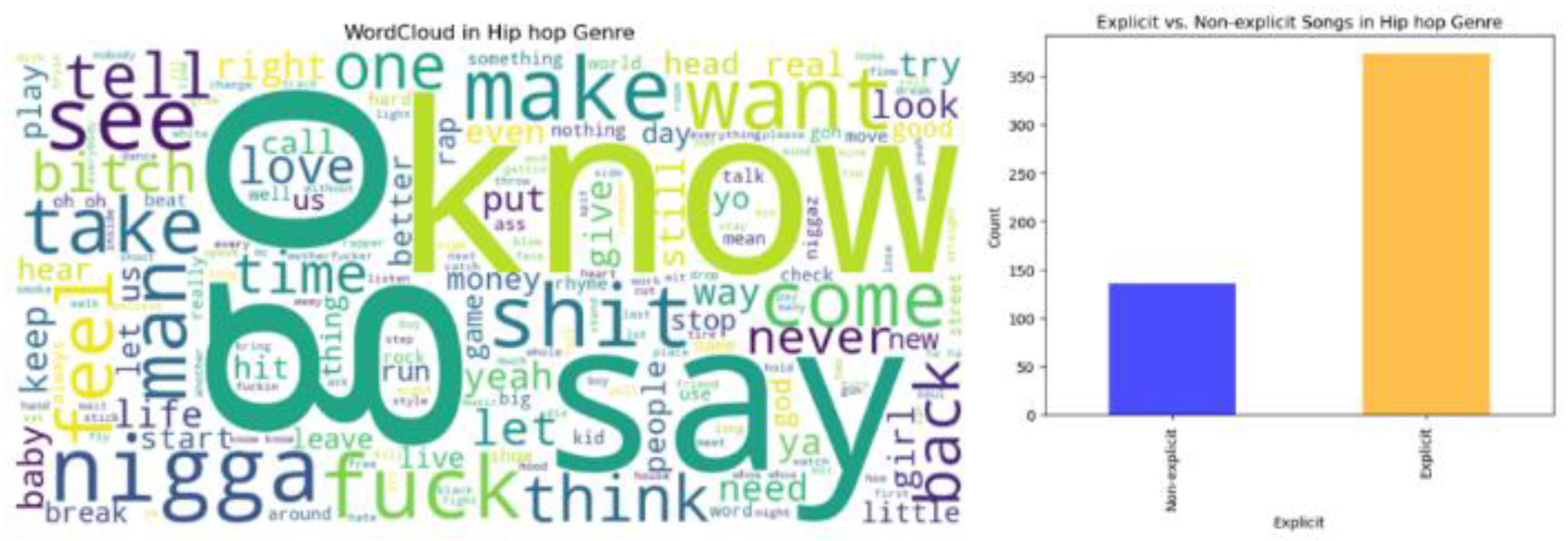

The relation between genre and explicit song becomes more prominent through textual analysis as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. In the rap genre, the bar chart reveals a significant prevalence of explicit songs over non-explicit ones, highlighting a trend towards more mature or potentially offensive content. The same trend is also being observed in the hip-hop genre where the bar shows a higher count of explicit observations. The word clouds for both genres further illuminate this phenomenon in the lyrics. In both categories, some of the frequently used derogatory terms stand out, namely “nigga”, “bitch”, “fuck”, and “shit”, suggesting a shared lyrical style and subject matter between the two genres. These visualizations together suggest that both rap and hip hop heavily feature explicit content and revolve around a set of similar themes and expressions in their lyrics.

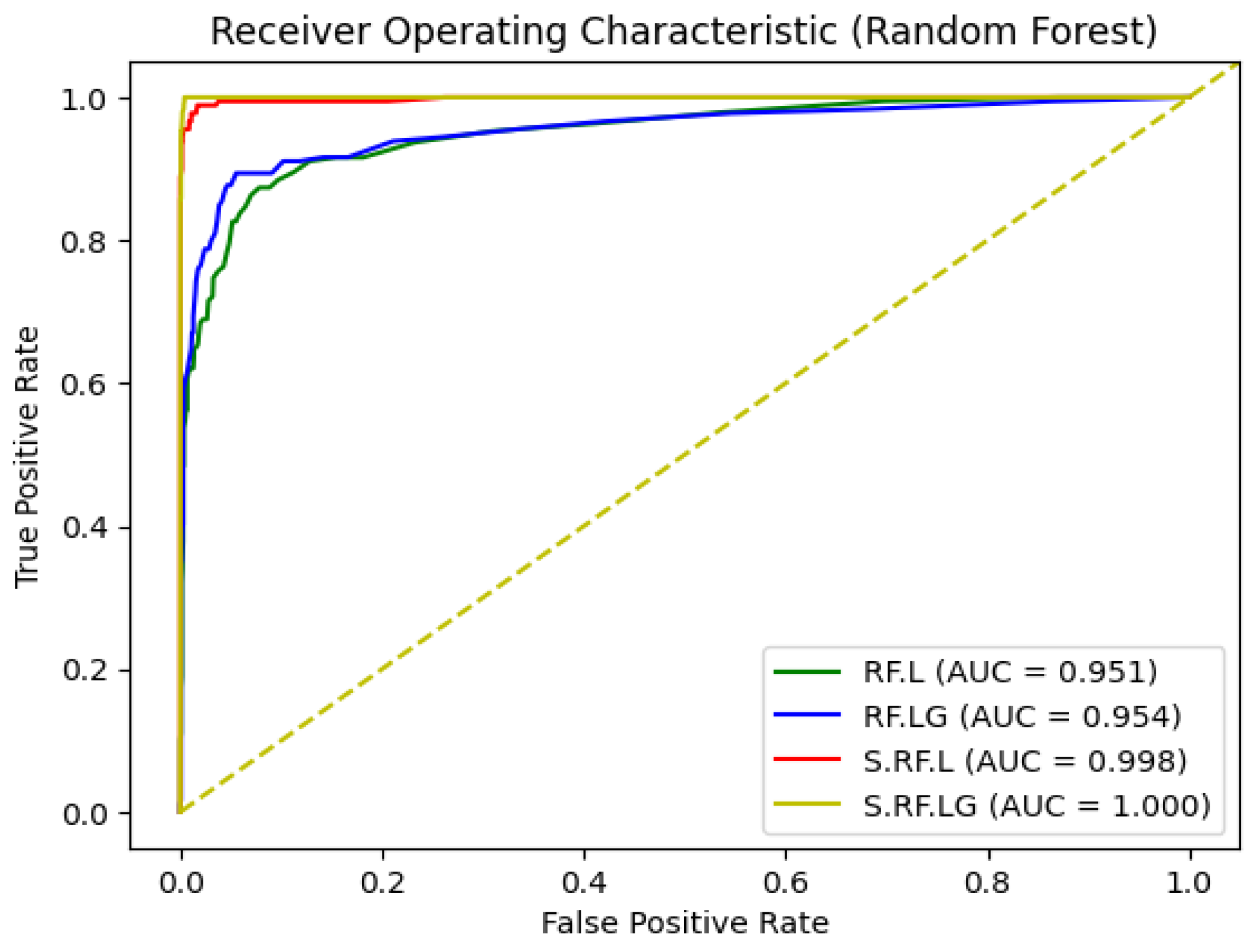

Imbalanced data, where certain classes are underrepresented, often leads to biased models that perform well on the majority class but poorly on the minority class. Addressing this issue, resampling techniques such as SMOTE are employed in this study. The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve shown in

Figure 3 is a visualization of the performance of Random Forest models in various thresholds. Models that are trained on oversampled data seem to have higher performance compared to those of imbalanced thus indicating the importance of resampling in mitigating this issue.

3.3. Practical Implications

The machine learning model developed in the current study to distinguish explicit instances of songs is beneficial for music streaming platforms. By incorporating genre-specific features, streaming services can significantly improve the accuracy of their explicit content detection. Whenever a new song is added to the platform, it is processed by the trained model to classify the content as explicit or non-explicit by analyzing the conjunction of lyrics with genre information. The explicit content labels and genre information are stored in a database alongside other song metadata. However, obtaining accurate genre data can be challenging due to the dynamic nature of musical genres. Despite this challenge, the trained model that uses lyrics alone has proven to be quite effective. Even without genre information, the model demonstrates a high level of accuracy in detecting explicit content, making it a valuable tool for streaming platforms. The models ensure that the classification data is readily available for content moderation and user interface functionalities. In addition, younger listeners would be prevented from unwanted content exposure and the implementation of robust parental controls where parents can confidently filter out explicit content.

The deployment of explicit content detection models must be guided by principles of responsible use, ensuring the respect of rights and dignity for both artists and listeners. To mitigate potential negative effects, it is crucial to provide clear guidelines and policies regarding the use of these models. These include on discussion on how the models function and what they detect as they are essential to building trust among users and artists. Additionally, it is important to support artists who might be impacted using these models. Providing resources such as policies and agreements on how explicit songs are handled in music streaming platforms can help artists navigate potential issues and maintain their creative freedom. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of the models are also necessary to identify and address any unintended consequences as well as to refine the models, ensuring they serve the intended purpose without compromising the listener experience.

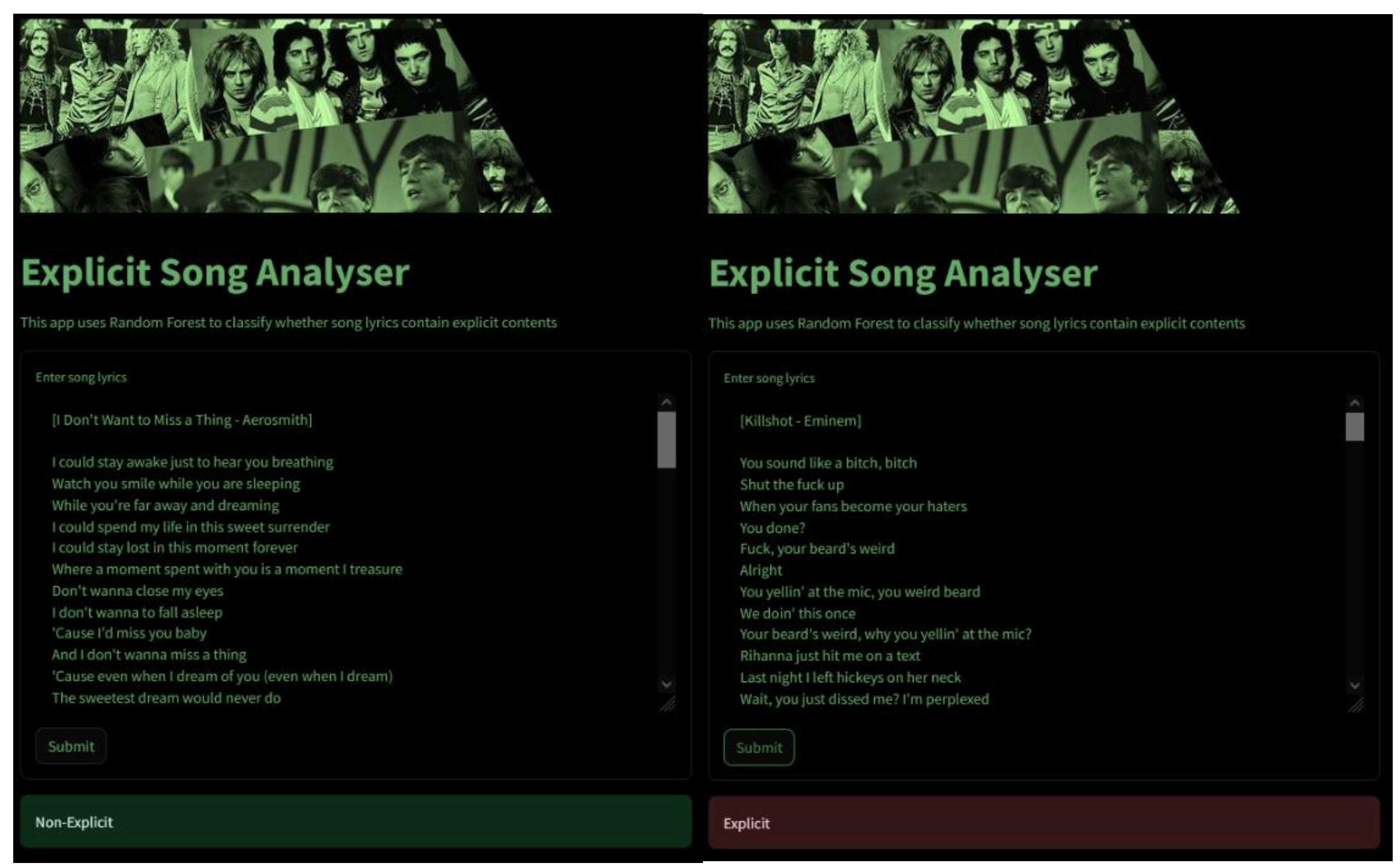

3.3. Deployment

The Streamlit application is a pivotal part of the deployment phase, transforming the theoretical model into a practical tool that end-users can interact with. It was also developed to demonstrate the capability of a trained machine learning model which allows users to input song lyrics and determine whether the lyrics contain explicit content using a pre-trained Random Forest classifier. The model that is trained in balanced data is used as it provides the highest performance. The interface is clean and intuitive, with clear instructions guiding users through the process of inputting lyrics and submitting them to the system as shown in

Figure 4. This application provides real-time feedback, with classification results displayed instantly after submission.

4. Conclusions

The current study addresses significant societal concerns regarding the impact of explicit content in song lyrics, particularly on younger audiences. Additionally, it also improves the efficiency of content moderation on digital music platforms. This is crucial given the impracticality of manual filtering due to the vast and rapidly growing number of songs available online. Automated systems based on the study’s findings can significantly reduce the workload on human moderators and increase the consistency and speed of identifying explicit content.

A comprehensive dataset for explicit song classification by integrating lyrics and genre-specific information was constructed by sourcing data from publicly available repositories and APIs, specifically from platforms such as Spotify and last.fm. The dataset included an explicit flag as the target variable and genre-related tags, ensuring a robust foundation for the classification tasks.

The impact of incorporating genre-specific features on the classifier’s performance is also being evaluated in the current study, especially on how these features influenced the accuracy and overall performance of the classification models. It is known that integration of genre information enhanced the models’ ability to detect explicit content. This improvement was evident in the evaluation metrics, which showed higher accuracy, precision, and recall for three models that utilized genre-specific features compared to those that did not.

The two-stage classification model involved an initial machine learning-based prediction, refined by a dictionary-based approach, is proved to be highly effective in enhancing recall as the dictionary-based refinement allowed for more accurate identification of explicit content through manual filtering. However, this trade-off results in significantly reduced precision. This occurs because the dictionary-based method is relatively simplistic and fails to account for the context. This model is preferable when the primary goal is to ensure that as much explicit content as possible is identified, even at the cost of increasing false positives. It is highly effective in scenarios where recall is more critical than precision. On the contrary, the genre-incorporated model is superior in contexts where a balanced approach is needed. It provides better classification performance by considering genre-specific features, making it more suitable for applications where minimizing false positives is essential. This is shown by each algorithm that is trained on a dataset enriched with genre-related features having better performance in terms of their F1-Score compared to their counterparts. The highest performance is achieved by the Random Forest model being trained in the genre-incorporated dataset, having accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score standing at 99.52%, 98.40%, 97.37%, and 97.88% respectively.

This study has provided valuable insights and established a foundation for ongoing and future research into explicit content detection using machine learning models. Even though the current approach has demonstrated effectiveness, several key areas can be further improved and explored to enhance the robustness, accuracy, and user-friendliness of these systems. Here are some detailed recommendations aimed at advancing these systems:

It is advisable to employ more sophisticated classification techniques, such as neural networks, that can better capture the intricate relationships among various content features.

User-annotated tag obtained from last.fm API may be utilized instead of only utilizing genre-related terms which may result in more accurate identification of explicit contents as specific tags applied by users themselves may also capture mood, artist influences, and other personalized descriptors.

Utilization of natural language processing (NLP) techniques like n-grams may help in capturing the contextual meaning of phrases and sentences, thereby improving the accuracy of explicit content detection in further study.

References

- Wallin, N. L., Merker, B., & Brown, S., “The Origins of Music” in Google Books, MIT Press, (2001).

- Petrušić, D., “New Challenges to Education: Lessons from around the World” in BCES Conference Books, (2021).

- Ramadhan, L., “American Subculture: An Identity Transformation of Hip Hop” in Rubikon, (2023), pp. 190.

- Frisby, C. M., & Behm-morawitz, E., “Undressing the Words: Prevalence of Profanity, Misogyny, Violence, and Gender Role References in Popular Music from 2006-2016” in Media Watch, (2019).

- Steinke, J., Lapinski, M., Zietsman-Thomas, A., Nwulu, P., Crocker, N., Williams, Y., Higdon, S., & Kuchibhotla, S., “Middle School-Aged Children’s Attitudes toward Women in Science, Engineering, and Technology and the Effects of Media Literacy Training” in Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, (2007), pp. 295–323. [CrossRef]

- Keenan-Kroff, S. L., Coyne, S. M., Shawcroft, J., Sheppard, J. A., James, S. L., Ehrenreich, S. E., & Underwood, M., “Associations between Sexual Music Lyrics and Sexting across Adolescence” in Computers in Human Behavior, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bogt, T. T., Hale, W. W., & Becht, A., “Wild Years: Rock Music, Problem Behaviors and Mental Well-being in Adolescence and Young Adulthood” in Journal of Youth and Adolescence, (2021).

- Im, H., Song, H., & Jung, J., “The Effect of Streaming Services on the Concentration of Digital Music Consumption” in Information Technology & People, (2019). [CrossRef]

- RIAA, “Year-End 2022 RIAA Revenue Statistics” in RIAA, (2022).

- Anantrasirichai, N., & Bull, D., “Artificial Intelligence in the Creative Industries: A Review” in Artificial Intelligence Review, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Y., Shanker, R. G. R., & Alluri, V., “Transformer-Based Approach Towards Music Emotion Recognition from Lyrics” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (2021), pp. 167–175. [CrossRef]

- Incekas, A. B., & Asan, U., “Data Driven Positioning Analysis of Music Streaming Platforms” in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, (2023), pp. 634–641. [CrossRef]

- Fell, M., Cabrio, E., Corazza, M., & Gandon, F., “Comparing Automated Methods to Detect Explicit Content in Song Lyrics”, (2019).

- Salam, A., Ghosh, R., Gosh, K., & Sarker, I., “Toxicity Classification on Music Lyrics Using Machine Learning Algorithms” in International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), (2021). [CrossRef]

- Chin, H., Kim, J., Kim, Y., Shin, J., & Yi, Mun. Y., “Explicit Content Detection in Music Lyrics Using Machine Learning” in IEEE Xplore, (2018)sing Machine Learning” in IEEE Xplore, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bergelid, L., “Classification of Explicit Music Content Using Lyrics and Music Metadata” in Unpublished, (2018).

- Mayerl, M., Vötter, M., Moosleitner, M., & Zangerle, E., “Comparing Lyrics Features for Genre Recognition” in ACLWeb, (2020).

- Egivenia, Setiawan, G. R., Mintara, S. S., & Suhartono, D., “Classification of Explicit Music Content Based on Lyrics, Music Metadata, and User Annotation” in 6th International Conference on Sustainable Information Engineering and Technology 2021, (2021).

- Bolla, B. K., Pattnaik, S. R., & Patra, S., “Detection of Objectionable Song Lyrics Using Weakly Supervised Learning and Natural Language Processing Techniques” in Procedia Computer Science, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rospocher, M., “Explicit Song Lyrics Detection with Subword-Enriched Word Embeddings” in Expert Systems with Applications, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rospocher, M., “On Exploiting Transformers for Detecting Explicit Song Lyrics” in Entertainment Computing, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Akalp, H., Furkan Cigdem, E., Yilmaz, S., Bolucu, N., & Can, B., “Language Representation Models for Music Genre Classification Using Lyrics” in 2021 International Symposium on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering, (2021).

- Li, Y., Zhang, Z., Ding, H., & Chang, L., “Music Genre Classification Based on Fusing Audio and Lyric Information” in Multimedia Tools and Applications, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C., “Lyric-Based Classification of Music Genres Using Hand-Crafted Features” in Reinvention: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research, (2021).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).