1. Introduction

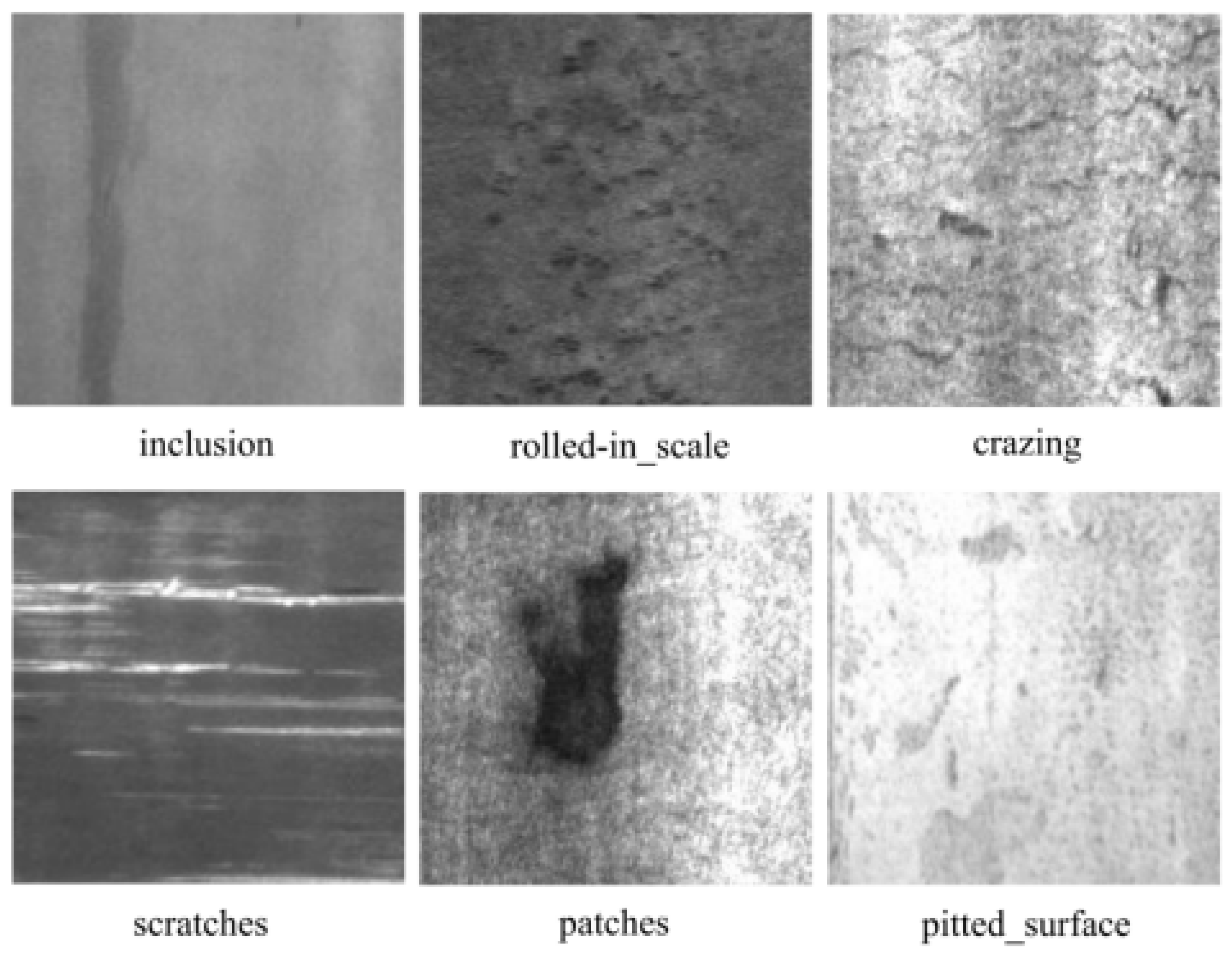

Thanks to its excellent plasticity and ease of forming, hot-rolled strip steel is not only essential for producing cold-rolled plates but also plays a critical role in fabricating large-scale structural elements, forgings, and automotive components [

1]. Nonetheless, limitations in production machinery and processes inevitably lead to surface imperfections. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the primary defects include inclusions, crazing, rolled-in marks, patches, pitted areas, and scratches. These flaws not only detract from the product’s appearance but, when the steel is used as a structural material, can act as stress concentrators that undermine performance and pose significant safety hazards [

2]. Consequently, developing precise and efficient defect detection methods proves crucial for manufacturing enterprises to implement rigorous quality control and enhance overall safety standards.

With the rise of the Internet and the vigorous development of deep learning technology, more and more machine vision tasks adopt deep learning models. Relative to established machine vision methodologies, deep learning-based machine vision defect detection methods typically exhibit superior detection accuracy, greater adaptability and a wider range of applications.

The YOLO series represents a prominent deep learning object detection approach. Initially proposed by Joseph et al. in 2015, YOLOv1 [

3] pioneered single-stage detection algorithms by significantly improving detection speed while maintaining reasonable accuracy. As a representative single-stage method, YOLO directly generates the existence probability and position coordinates of the de-tected objects during the detection process. Its characteristic is a relatively fast speed but at the expense of detection accuracy. YOLO algorithms directly predict target existence probability and positional coordinates during detection, offering rapid detection speeds at the expense of some precision reduction.

In contrast, the two-stage method illustrated by the Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (Faster R-CNN) [

4] first extracts candidate boxes and then outputs the detection results. It has an advantage in detection accuracy but has certain limitations in real-time performance. To address the accuracy-speed trade-off in defect detection, Feng et al. [

5] developed an enhanced RepVGG architecture integrated with spatial attention mechanisms. Building upon these developments, Shun et al. [

6] demonstrated superior performance over YOLOv4 through a YOLOv5-based framework optimized for hot-rolled steel strip surface defects. Further advancing feature extraction capabilities, researchers [

7] incorporated the BI-SPPFCSPC structure into YOLOv7’s feature pyramid, significantly improving small object detection precision. Zhang et al. [

8] introduced the Content-Aware Reassembly of Features (CARE) upsampling operator into the YOLOv8s model, effectively enhancing the feature extraction capability. Wang et al. [

9] introduced ShuffleNetv2 as the backbone network in YOLOv5s and, through depthwise separable convolution and channel shuffling techniques, This approach substantially reduces model parameters while maintaining high detection accuracy. The above studies continuously explore a reasonable balance between model lightweight and detection accuracy, effectively improving detection accuracy and reducing inference time. However, they have not achieved a perfect balance among model parameters, computational cost, model size, computational accuracy, and inference time, and thus cannot fully meet the requirements of real-time hot-rolled steel strip defect detection. Given the stringent real-time and edge deployment demands in industrial settings [

10], making the model more lightweight is extremely important.

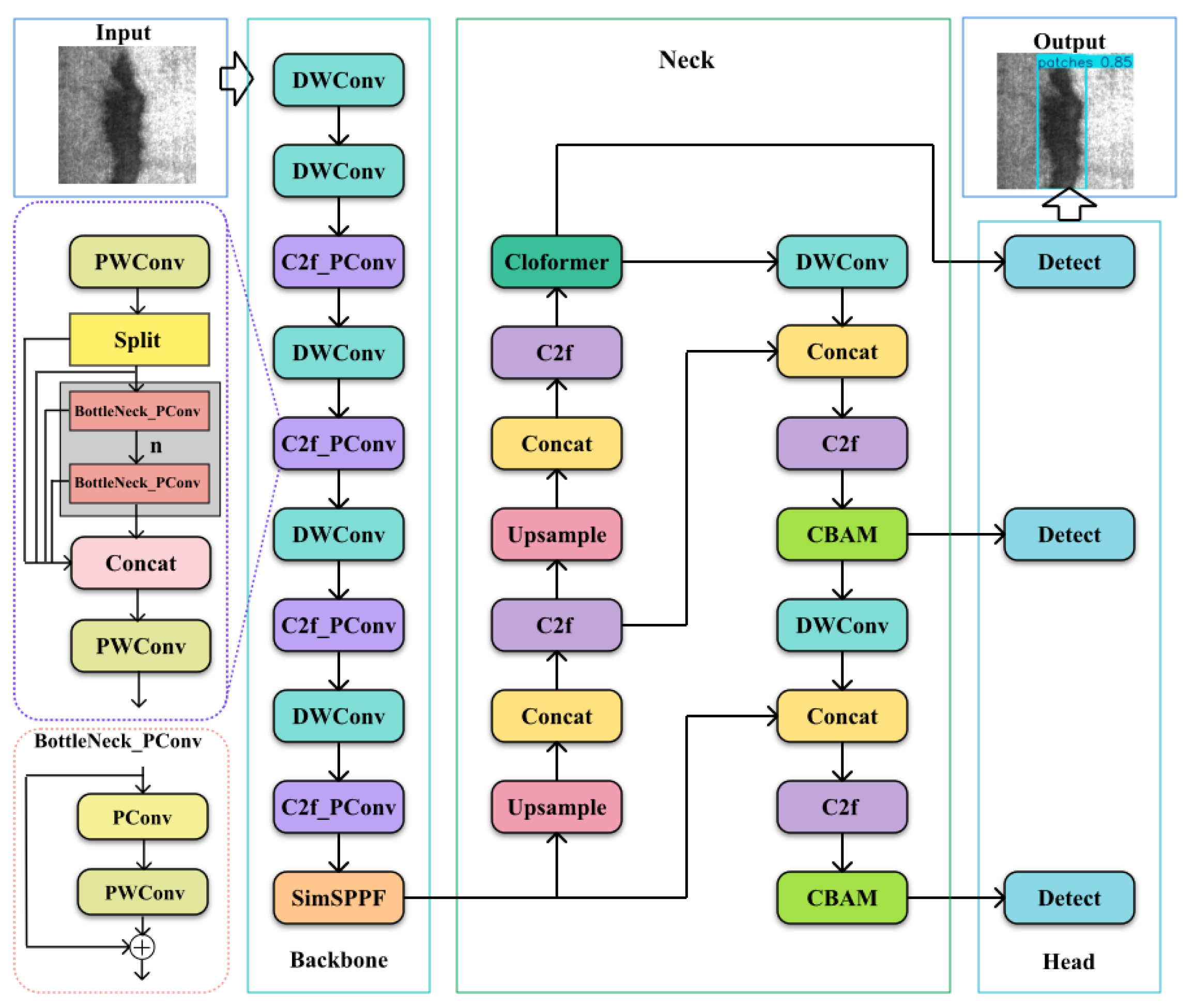

To meet stringent real-time detection requirements concerning surface faults in hot-rolled steel strips, this study optimizes the YOLOv8s network through three aspects: accuracy enhancement, model complexity reduction, and inference acceleration. First, by integrating Cloformer [

11] with CBAM [

12], the approach maximizes detection accuracy without a significant increase in model parameters. Second, the incorporation of depthwise separable convolution (DWconv) [

13] alongside partial convolution (Pconv) [

14] refines the backbone network and C2f module, substantially reducing both model parameters and computational complexity. Finally, SimSPPF [

15] is employed to effectively extract and merge multi-scale features, these modifications not only improve multi-scale target recognition but also accelerate inference speed. Together, these improvements enable the model to be deployed on-site, meeting the stringent speed and accuracy requirements necessary for real-time monitoring.

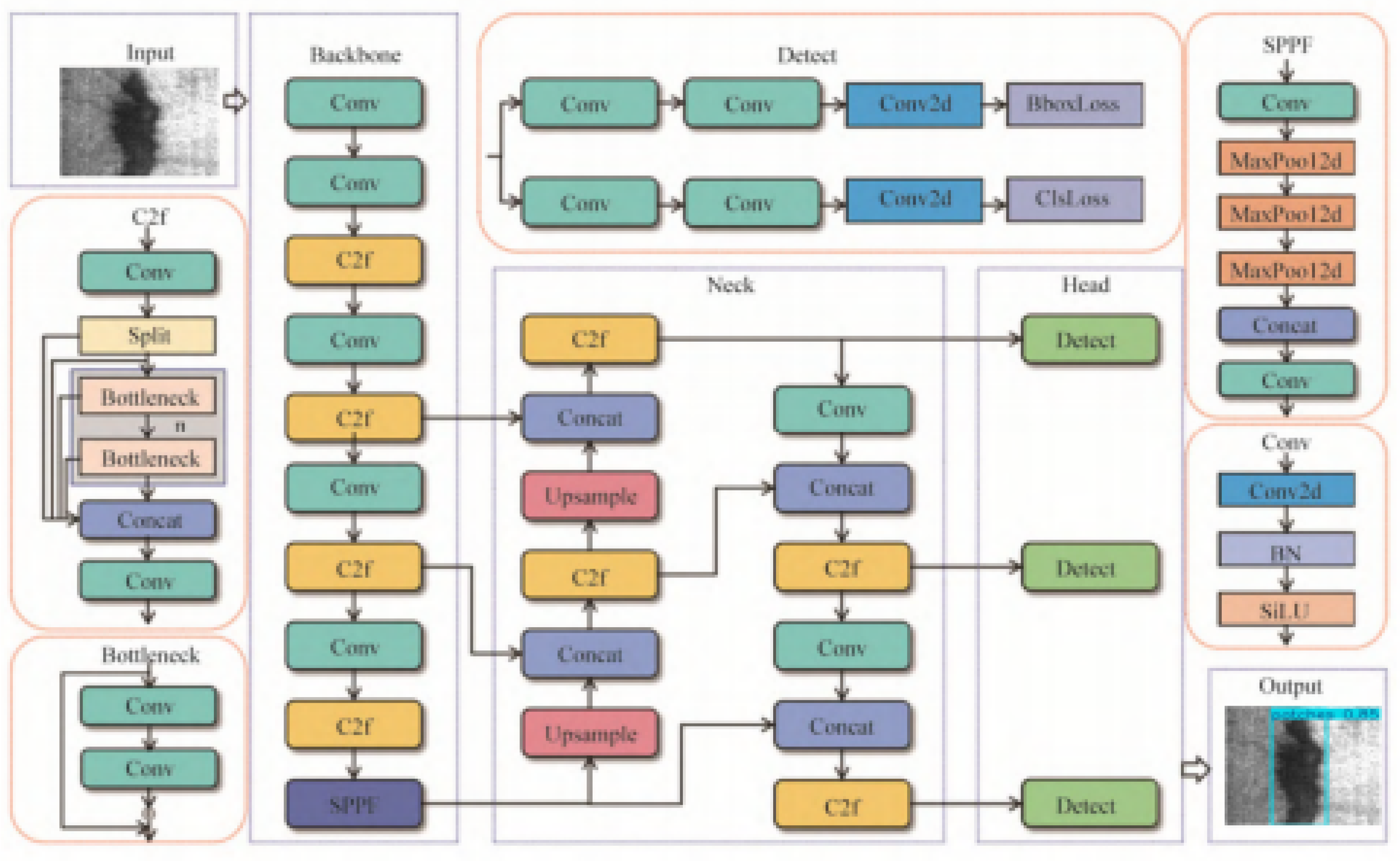

2. YOLOv8 Overview

The YOLO family of algorithms is renowned for its ability to perform real-time object detection while learning features effectively and generalizing well across complete images. Leveraging improvements from YOLOv5, the latest version, YOLOv8, achieves cutting-edge performance in object detection tasks [

16]. Based on network depth and width, YOLOv8 offers five model variants: YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x. For optimal balance between accuracy, speed, and model size in hot-rolled steel strip defect detection, YOLOv8s serves as the starting point for optimization. The YOLOv8s architecture is primarily arranged into four components: the input module, Backbone, Neck, and Head, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.1. Input End

The input of YOLOv8 is standardized images, supporting multi-scale input (such as 640×640, 1280×1280, etc.). The preprocessing includes image normalization, data augmentation, and adaptive scaling. Image normalization is responsible for normalizing pixel values from [0, 255] to [0, 1]. Data augmentation adopts Mosaic data augmentation (random cropping, rotation, flipping, etc.), and Mosaic is turned off in the later stage of training to improve accuracy and enhance convergence [

18]. Adaptive scaling maintains the aspect ratio of the image through the Letterbox method and fills gray borders to avoid distortion.

2.2. Backbone

The backbone module primarily handles feature extraction through three core components: the C2f module [

19] (cross-stage fusion with dual convolution and merging), SPPF module (fast spatial pyramid pooling), and fundamental convolutional blocks.

2.2.1. C2f

C2f replaces the C3 module in YOLOv5 with a design inspired by the ELAN structure in YOLOv7, incorporating multiple Bottleneck modules and cross-layer connections. Initial channel compression is achieved through 1×1 convolution., then splitting the output into two branches. One branch is processed through several Bottleneck modules, while the other is left unchanged. After merging these two branches, a 1×1 convolution is applied to restore the channel dimensions. Compared to C3, the C2f module reduces The number of variables by about 20% while strengthening gradient flow and feature reuse.

2.2.2. SPPF

The SPPF module achieves multi-scale feature fusion by concatenating multiple 5×5 max pooling layers in series. The input passes through three pooling layers (stride = 1, padding = 2) in sequence, and the results are concatenated and compressed through convolution. The proposed mechanism enhances spatial awareness through expanded receptive fields, enabling superior generalization to objects at disparate scales.

2.3. Neck

The Neck module employs an improved PAN-FPN structure for cross-scale feature combinatio. In this design, the FPN pathway [

20] conveys nuanced semantic patterns from smaller feature maps downwards, while the PAN [

21] pathway transmits low-level location details from larger feature maps upwards. The process involves first aligning feature map sizes via upsampling (for example, through nearest neighbor interpolation), then concatenating features from various Backbone stages, and finally applying the C2f module to further integrate the fused features.

2.4. Head

Head is responsible for object detection and classification, adopting a decoupled head and anchor-free mechanism.

2.4.1. Decoupled Head

The decoupled detection head utilizes binary cross-entropy loss (BCE Loss) for class prediction, combined with DFL loss [

22] and CIOU loss [

23] for bounding box coordinate regression.

2.4.2. Anchor-Free

It directly predicts the target center point (x, y) and width and height (w, h), eliminating the need to adjust hyperparameters of preset anchor boxes [

24]. The formula is:

where ,

,

are grid coordinates and

,

is the stride of the feature map.

3. Improved YOLOv8s Object Detection Algorithm

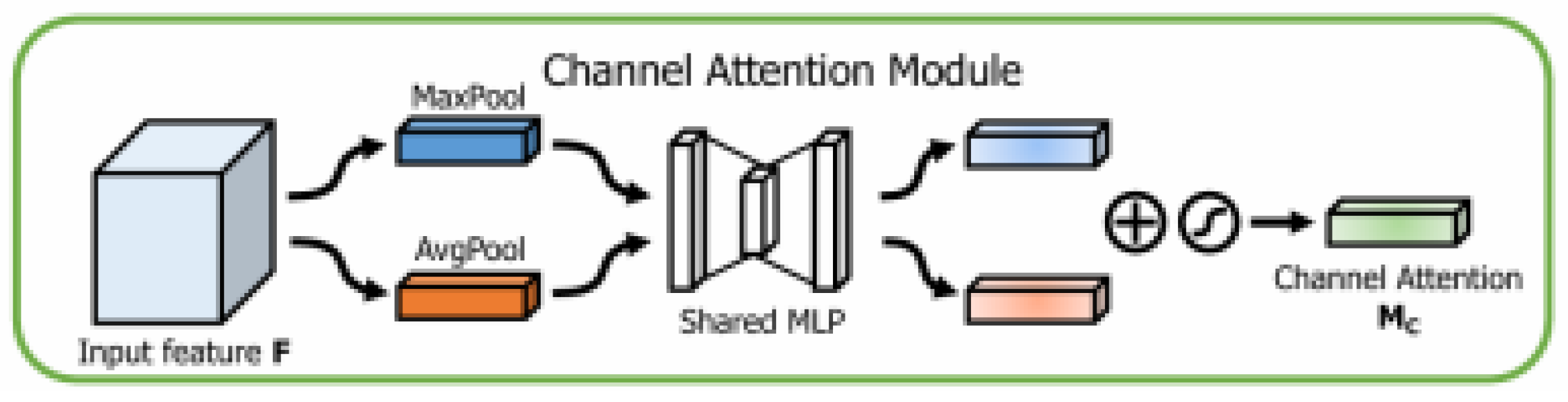

3.1. Cloformer and CBAM Attention Mechanism

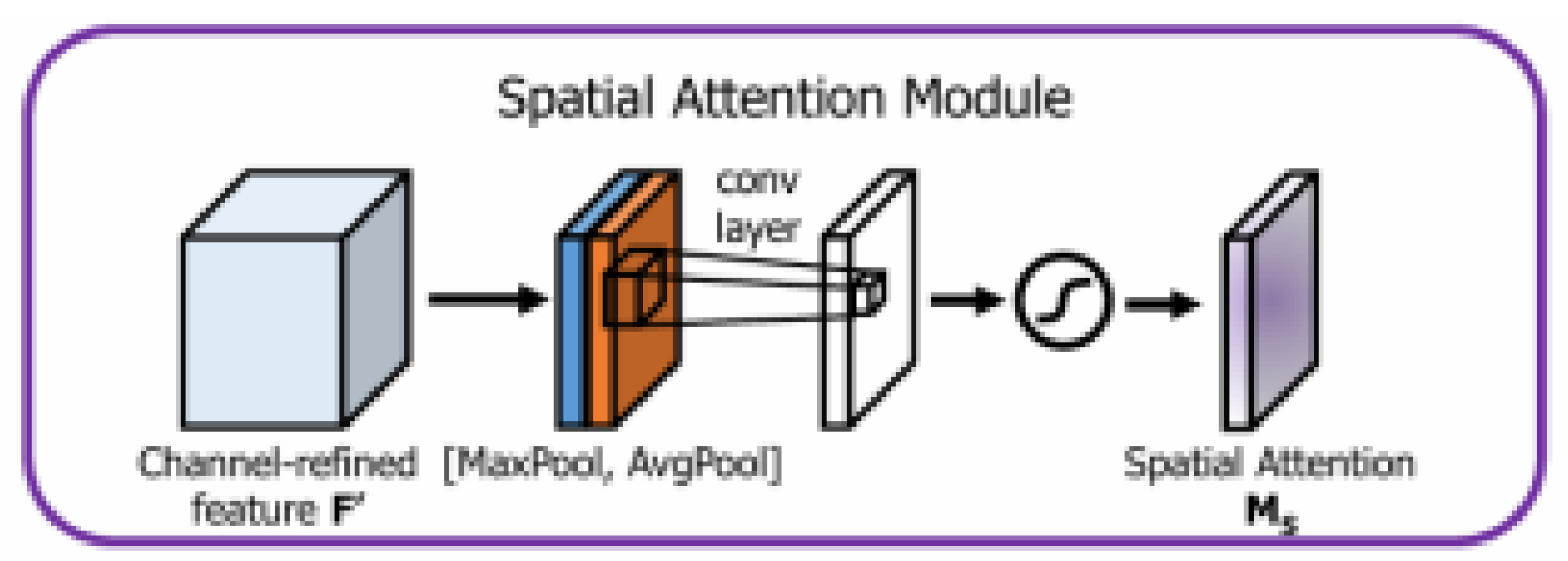

Lightweight surface flaw identification models for hot-rolled steel strips often suffer from insufficient accuracy. At the same time, YOLOv8 also has certain issues in defect detection. Due to the limited sensitivity of its default architecture to defect features, it is prone to missed or false detections when facing lightweight and subtle surface defects. Moreover, this architecture is difficult to effectively integrate feature information of different scales, resulting in poor adaptability of the model in complex scenes. A common solution to this problem is to introduce an attention mechanism. CBAM addresses traditional CNN limitations in processing multi-scale, shape, and orientation information through dual attention mechanisms: channel attention improves feature representation across channels, while spatial attention extracts critical spatial information. CBAM comprises two key components: channel attention module (C-channel) and positional attention module (S-channel), which can be integrated at different network levels to strengthen feature representation. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the operational principles of channel and spatial attention modules differ fundamentally. In CBAM, element-wise multiplication of both channel and positional attention mechanisms outputs produces enhanced attention features (

Figure 5). These refined features propagate through subsequent layers, effectively preserving critical information while filtering noise.

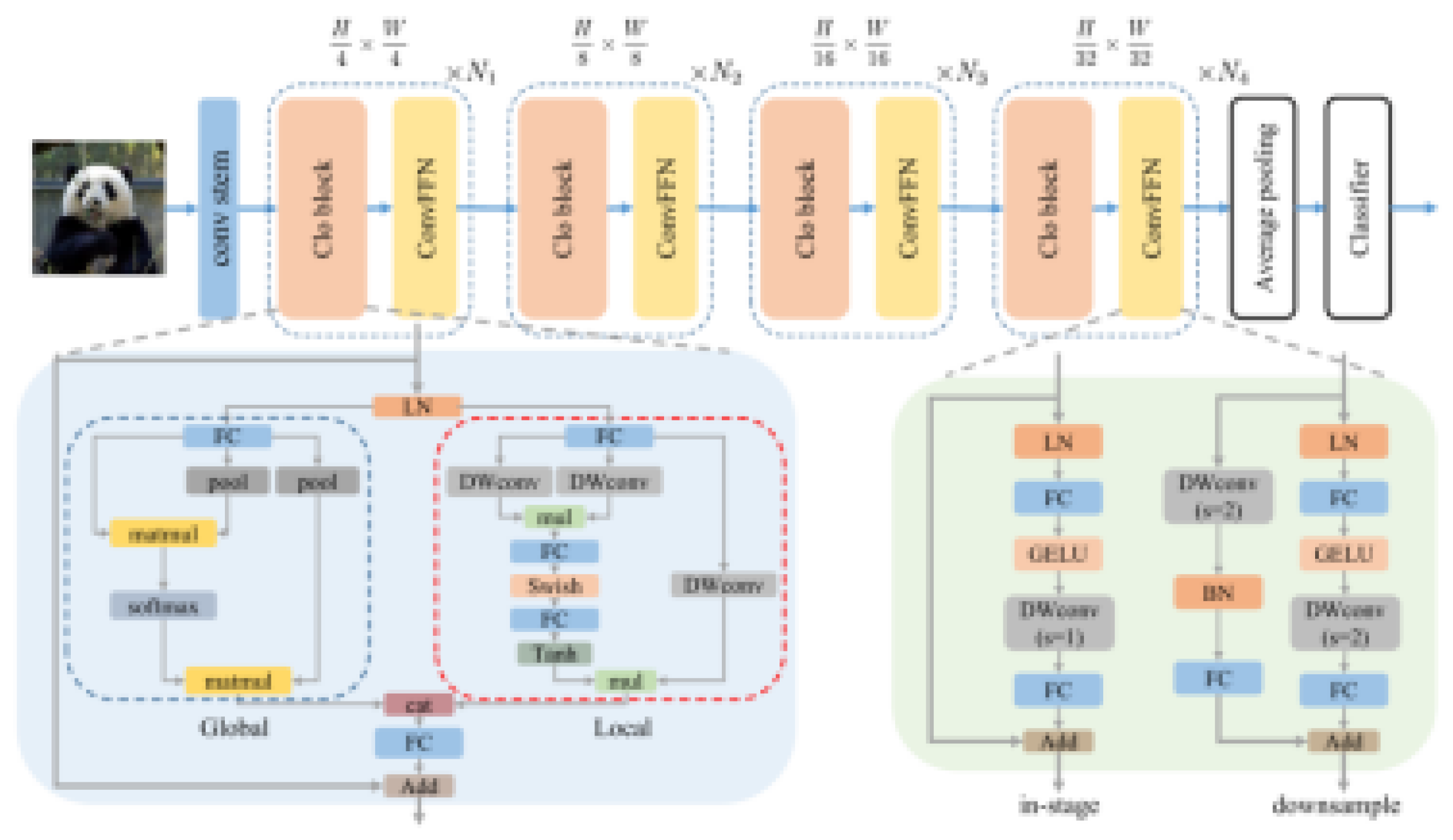

CloFormer introduces a module named AttnConv that combines the attention mechanism and convolution operation, capable of capturing high-frequency local information. Compared with traditional convolution operations, AttnConv employs shared weights and context-aware weighting to better process inter-position relationships. Experimental results demonstrate CloFormer’s superior classification performance for images, object detection, and semantic segmentation challenges.

Figure 6.

The illustration of CloFormer. CloFormer is constructed by connecting Clo block and ConvFFN in series. Alldepth-wise convolutions in the local branch have the stride of 1 [

11].

Figure 6.

The illustration of CloFormer. CloFormer is constructed by connecting Clo block and ConvFFN in series. Alldepth-wise convolutions in the local branch have the stride of 1 [

11].

Although CBAM is lightweight, its performance gains are modest. In contrast, while Cloformer can significantly boost accuracy, AttnConv employs shared weights and context-aware weighting to better process inter-position relationships. Experimental results demonstrate CloFormer’s superior performance in classifying images, detecting objects, and segmenting semantically. However, this method substantially increases both model parameters and computational overhead. To optimize accuracy without substantially inflating the model size, this paper integrates both CBAM and Cloformer into the Neck module and investigates how various combinations affect precision and detection speed. As illustrated in

Table 1, experiments 1-3 apply CBAM to the small, medium, and large object detection heads respectively, with the remaining heads receiving Cloformer input. Conversely, experiments 4-6 assign Cloformer to the small, medium, and large detection heads while using CBAM for the others. Scenarios that completely omit either CBAM or Cloformer are not considered, with the other two detection heads receiving input from CBAM. Scenarios that completely omit either CBAM or Cloformer were not considered in our experiments.

Taking into account model size, detection speed, and accuracy, this paper adopts the combination strategy from Experiment 4. In this setup, the medium and large object detection heads utilize outputs from CBAM, while the small detection head uses Cloformer outputs. This configuration improves detection accuracy by 1.42% with an increase of only 0.4M parameters.

3.2. Model Lightweight Design

Efforts to develop lightweight models for hot-rolled strip steel surface defect detection often involve replacing the backbone with networks such as MobileNet or ShuffleNet [

17].The improved YOLOv8 architecture needs to be deployed on edge devices while ensuring detection accuracy. Edge devices have relatively limited computing power and memory resources, which requires the model to not only accurately identify lightweight surface defects in hot-rolled steel strips, but also have low computational complexity and memory usage. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate lightweight design into the architecture design. However, this approach, while reducing computational load, it increases memory access overhead. Such approaches fail to effectively address network latency issues and may compromise inference speed, resulting in them being unsuitable for real-time surface defect detection in hot-rolled steel strips.

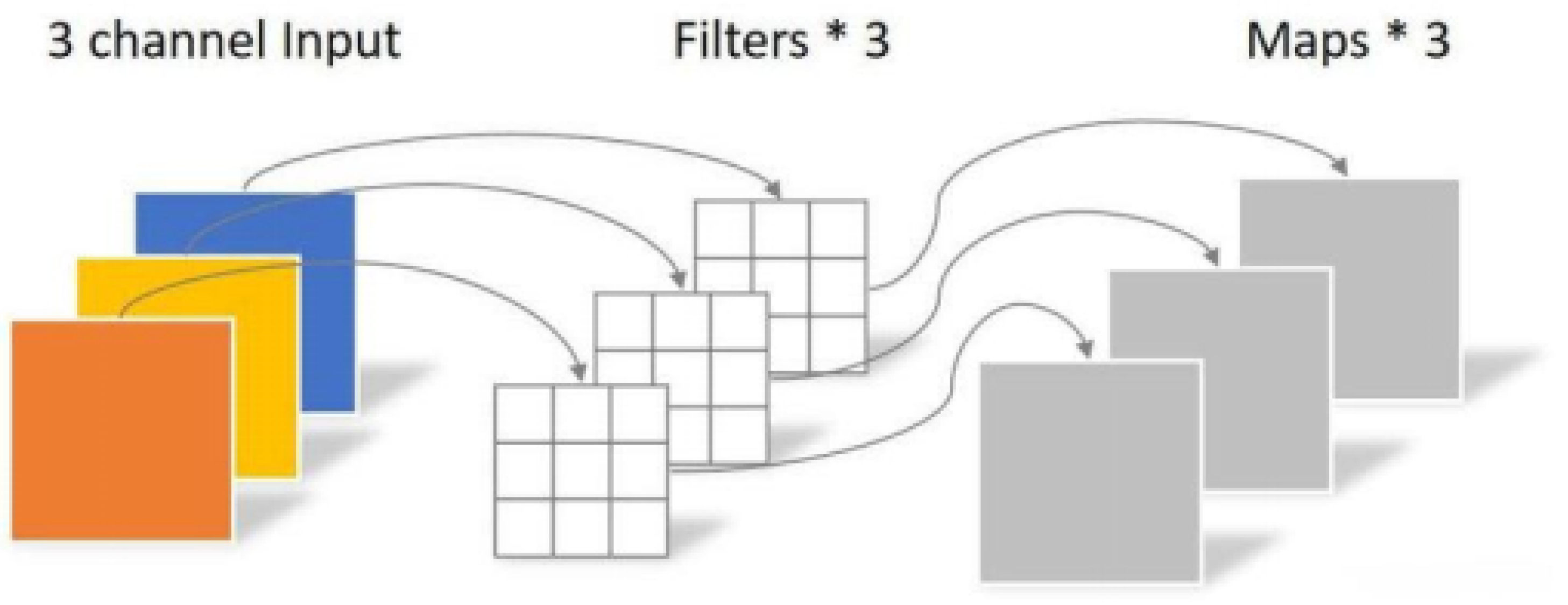

Depthwise separable convolution (DWConv) is a lightweight convolution operation method specifically designed to enhance memory access efficiency and operational speed.

Compared with standard convolution, depthwise separable convolution significantly reduces parameter count and computational load, alleviate overfitting, and improve inference speed and real-time detection performance. It has been proven to perform well in various lightweight models, substantially decreasing the computational and storage requirements of the model while maintaining consistent accuracy [

25]. DWConv can significantly reduce the computational complexity by decomposing standard convolution into two blocks: depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution [

26], as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. For a convolution kernel of size

, input channels M, output channels N, and output feature map dimensions

, standard convolution parameters and computational costs are:

The difference between depthwise convolution (DConv) and standard filtering process lies in that the depthwise convolution kernel is configured for single-channel operation, and convolution needs to be performed on each channel of the input. Thus, the output feature map will maintain the same channel dimension as the input feature map. That is, the number of input feature map channels = the number of output feature map channels. convolution kernels = the number of output feature map channels. Therefore, its parameter quantity and computational cost are:

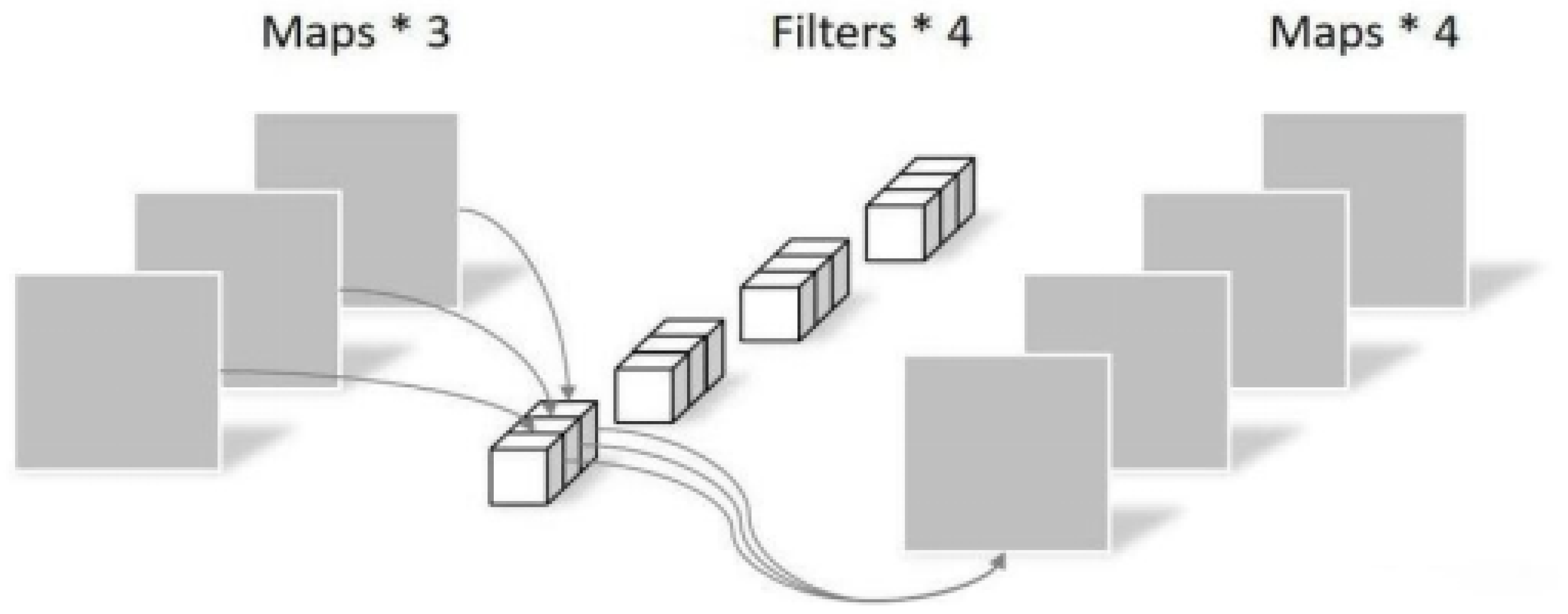

In depthwise convolution, identical channel counts for input features and convolution kernels may limit output feature diversity. Pointwise convolution (PWConv) addresses this through 1×1 convolution-based channel expansion, with parameters and computations being:

Combining depthwise and pointwise convolutions reduces parameters and computations to approximately

of standard convolution, particularly when N is large.

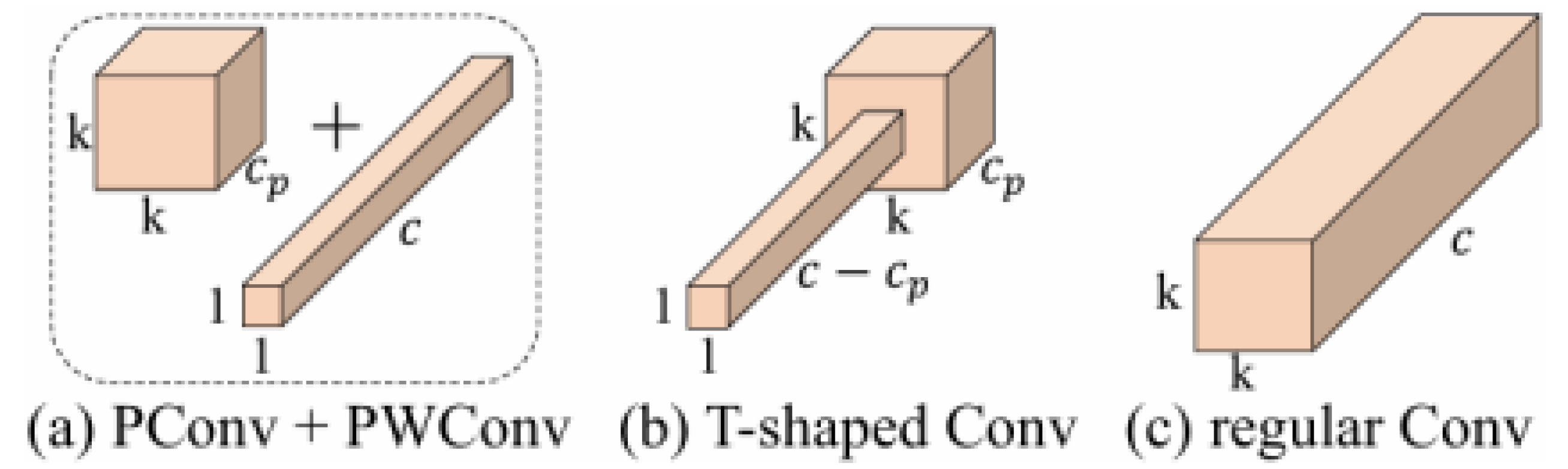

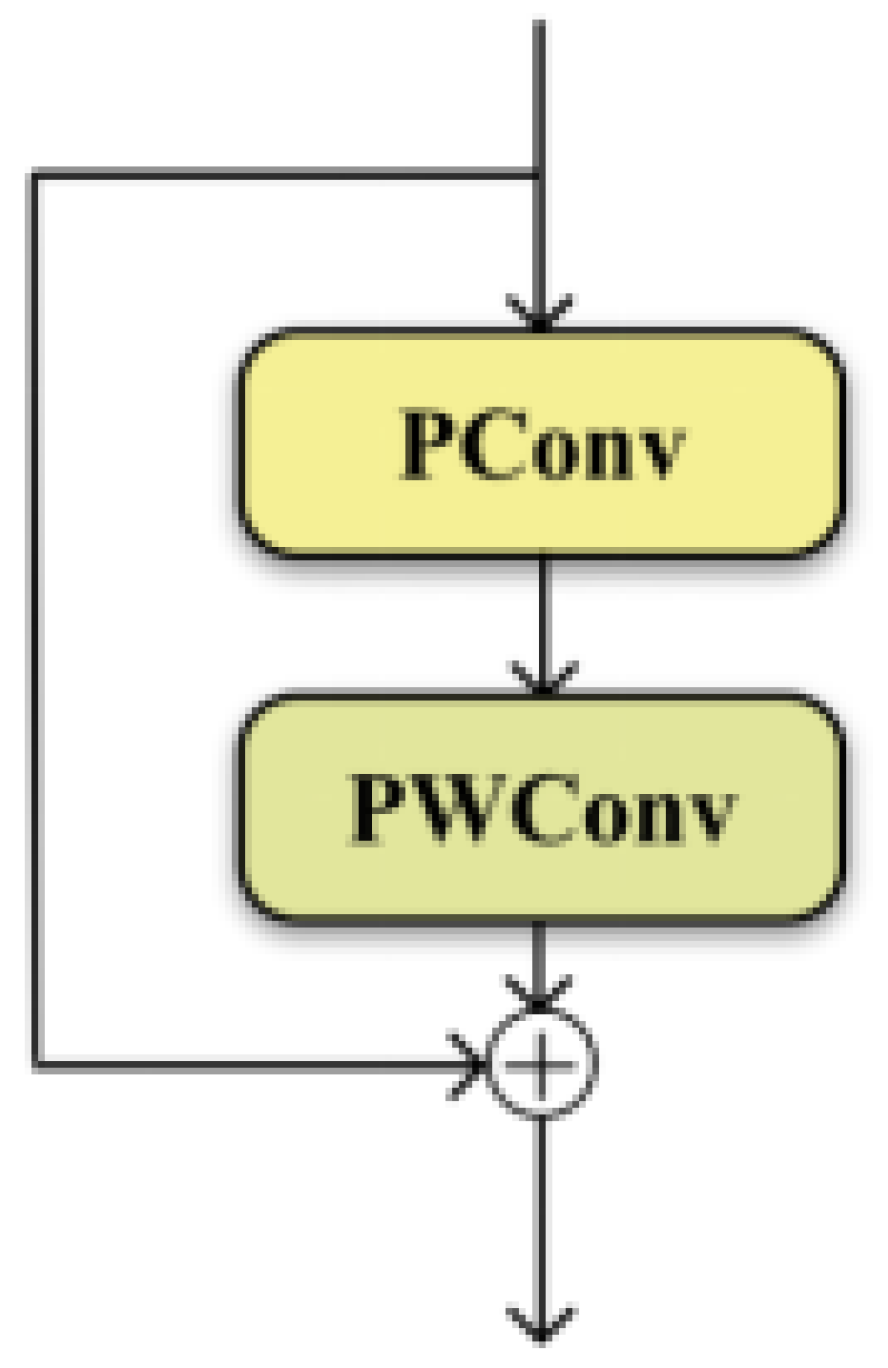

In addition, we have observed a significant redundancy among different channels in the feature maps. Partial convolution (PConv) leverages channel redundancy by applying standard convolution to a continuous subset (e.g., first/last c channels) while keeping others unchanged. This maintains input-output dimensional consistency while reducing computation and parameters.

To ensure full channel information utilization, pointwise convolution (PWConv) immediately follows PConv. Together, these operations create a receptive field with significant impact that resembles a T-shaped convolution, which emphasizes the central region more than standard convolution. This decomposition into PConv and PWConv further exploits the redundancy between filters and reduces FLOPS, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

Experiments have demonstrated that PConv demonstrates effectiveness in spatial feature extraction. By constructing a simple network composed of PConv and PWConv and training it on a dataset of feature maps extracted from a pre-trained ResNet50, the results show that PConv + PWConv achieves the lowest test loss and better approximates the feature transformation of conventional convolution, indicating that capturing spatial features from only partial feature maps is sufficient and efficient [

14].

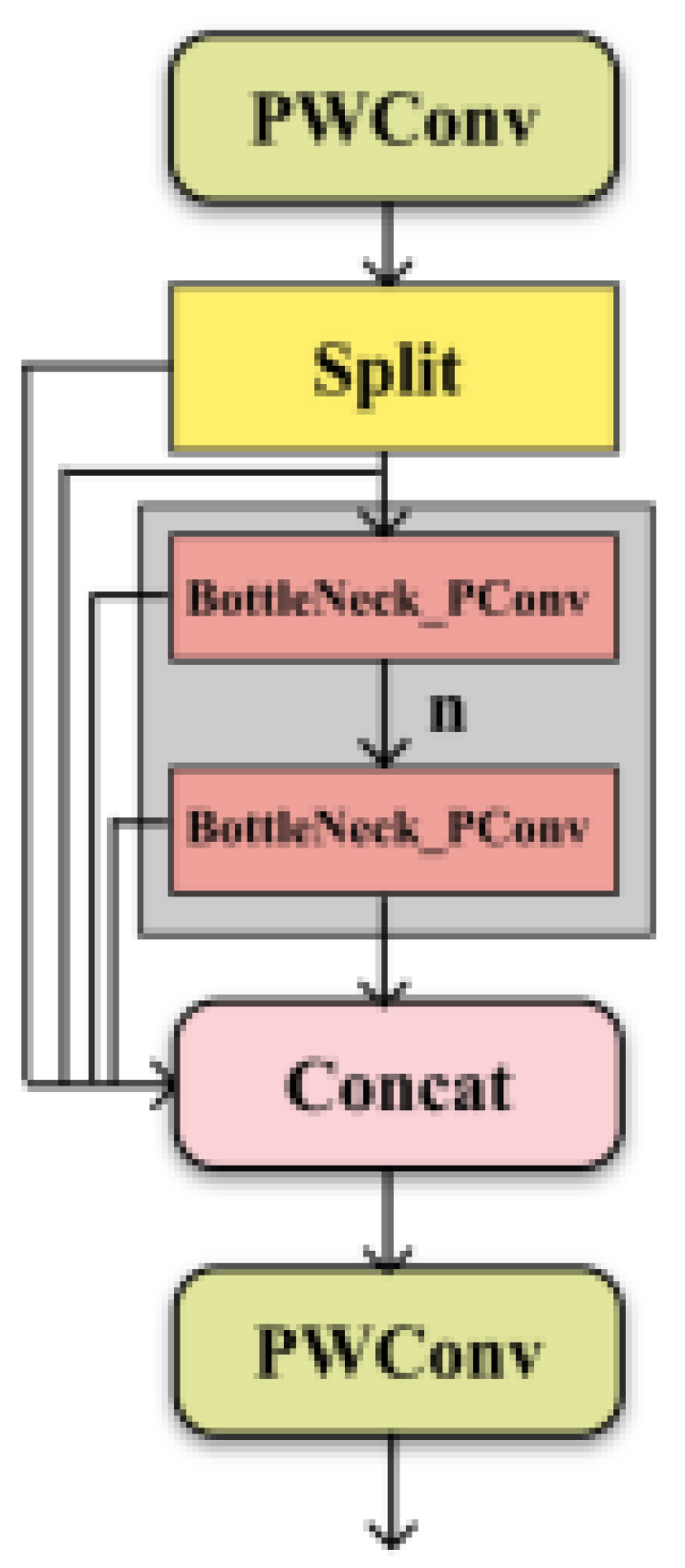

To integrate DWConv and PConv, this paper substitutes the standard convolution i in the backbone network by using DWConv and enhances the C2f module. Specifically, the conventional convolution operations in both the C2f module and the Bottleneck are substituted with a combination of PConv and PWConv, resulting in a notable drop in model parameters and improved accuracy. The architectures of the modified C2f module and Bottleneck are depicted in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

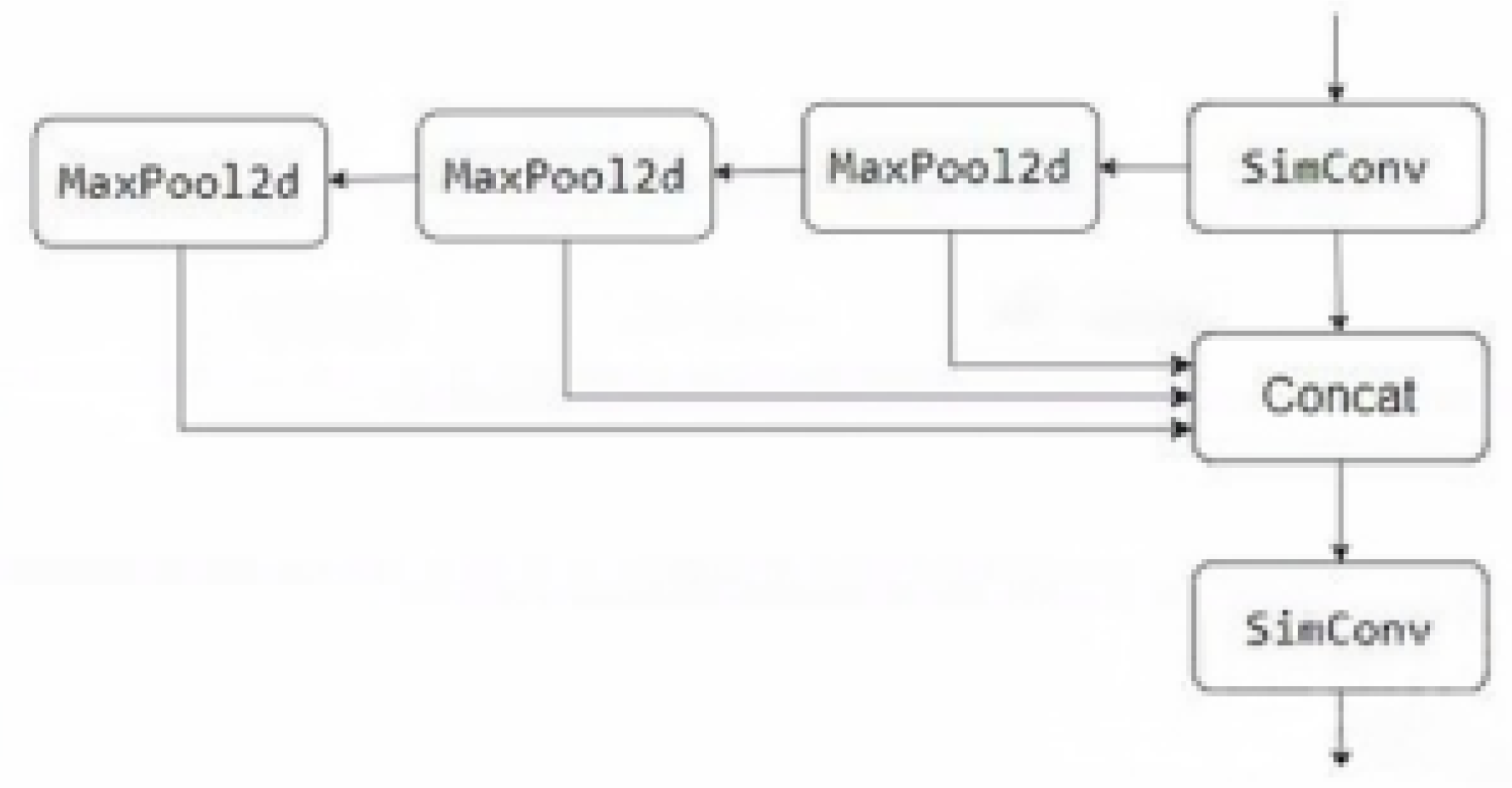

3.3. Improvement of the SPPF Module

Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) is mainly designed to address the issue of variable input image sizes. In traditional convolutional neural networks, it is usually required that input images have a fixed size, which brings many inconveniences in practical applications. Spatial pyramid pooling generates fixed-length outputs for variable-size inputs, enabling flexible image processing. SPPF represents an optimized version of this approach [

27]. However, while SPPF reduces the computational load, it increases the number of model parameters, which can have a certain impact on the training as well as the model’s inference performance. The SimSPPF module is introduced to further accelerate model detection.

Originally proposed in YOLOv6, SimSPPF serves as a simplified spatial pyramid pooling structure for efficient feature extraction in computer vision tasks. As illustrated in

Figure 12, SimSPPF comprises two primary components. The first component consists of a series of convolution operations, starting with an initial SimConv layer that processes the input feature map and reduces its channel count by half. SimConv is a custom module that integrates convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU activation; it generates features based on the input, accelerates training and stabilizes the model via batch normalization, and enhances expressive power through the nonlinearity provided by ReLU. The second component involves multiple max pooling and concatenation operations to fuse features from different scales, subsequently connected to a final SimConv layer that converts the fused feature map to the desired output channel number.

In order to enhance the inference speed of YOLOv8 model in steel defect detection, we replaced the SPPF module of the original model with SimSPPF module. The SimSPPF module has optimized the spatial pyramid pooling structure in its design. Compared to the SPPF module, it significantly reduces computational complexity by simplifying the operation process. In the process of steel defect detection, the complex surface texture and defect features require high computational efficiency of the model. The low computational load of SimSPPF module effectively reduces the computational burden of the model and accelerates the inference speed. After applying it to the surface defect detection of hot-rolled strip steel, the inference speed was increased by about 20%. In addition, the SimSPPF module exhibits good lightweight characteristics while maintaining model detection accuracy, which meets the deployment requirements on edge devices.

Figure 13 shows the overall network architecture of the enhanced YOLOv8.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Dataset

The NEU-DET public dataset for hot-rolled steel strips contains six defect types: Crazing (Cr), Inclusion (In), Patches (Pa), Pitted Surface (Ps), Rolled-in Scale (Rs), and Scratches (Sc). Each type includes 300 200×200 grayscale images, some containing multiple defects. Data is split 9:1 into training and test sets, with sample images shown in

Figure 1.

4.2. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

Experiments employ an Intel Core i7-13700KF CPU with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060Ti GPU, running Windows 11, Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.6.0, and CUDA 12.6. In this paper, the initial learning rate for all YOLO models is 0.0003, which linearly decreases with the epochs, and the final learning rate is 1% of the initial value. The optimizer used is AdamW (Adam with Decoupled Weight Decay) [

28]. A batch size of 8 is used, the number of training rounds is 500, and an early stopping mechanism is adopted with a patience of 80. All input images are uniformly adjusted to 640px × 640px, and data augmentation is performed using Albumentations [

29].

4.3. Evaluation Indicators

Given multiple existing algorithms for hot-rolled steel strip defect detection, comprehensive evaluation metrics are essential for objective performance assessment.

This work employs conventional object detection metrics—such as model parameters (Params), computational complexity (FLOPs), defect-specific accuracy, we evaluate using Average Precision (AP), mean Average Precision (mAP), and processing speed (FPS)—to comprehensively assess performance. The Params and FLOPs metrics are used to evaluate the network’s lightweight characteristics, while FPS measures its real-time detection capability. Generally, achieving an FPS above 30 indicates that the model meets the on-the-fly detection requirements.

Accuracy metrics include precision (P) and recall (R). Precision measures correct predictions among all detections, while recall indicates detected true defects. Calculation formulas are:

In Equation (

10):

represents the number of correctly predicted positive samples;

represents the number of correctly predicted negative samples;

represents the number of incorrectly predicted negative samples;

represents the number of incorrectly predicted positive samples.

The calculation formulas for precision and average precision are:

The performance of mAP varies at different thresholds. The most commonly used one is mAP@0.5, which represents the average precision of all categories when the threshold IOU is 0.5.

4.4. Melting Experiments and Result Analysis

To evaluate how these five enhancements influence the model’s detection performance and complexity, we carried out ten experiments under consistent environmental and parameter conditions. Each experiment was trained five times, and the trial achieving the highest accuracy was recorded.

Table 2 presents the outcomes, where “✔” denotes the incorporation of the corresponding module.

Table 2 indicates that augmenting YOLOv8s with either CBAM or Cloformer substantially raises the average detection accuracy for identifying defects on hot-rolled steel strips. Conversely, introducing DWConv lowers the model’s parameter count and computational overhead, thereby markedly increasing detection speed while also improving accuracy. Although using partial convolution results in a slight 0.45% decrease in accuracy, its major benefits in lowering parameters and computational cost—and the corresponding speed gains—are considerable. Additionally, the combination with SimSPPF not only improves detection accuracy marginally but also increases inference speed by approximately 20%. Ultimately, the fully enhanced YOLOv8s model (YOLOv8s+CBAM+DWConv+PConv+Cloformer+SimSPPF) achieves superior performance in detection accuracy, precision, and recall. Its outstanding detection speed is particularly critical for industrial defect detection scenarios with high real-time demands. Therefore, the proposed improved algorithm delivers both high accuracy and exceptional real-time performance in detecting irregularities on the surface of hot-rolled steel strips, proving its effectiveness in practical applications.

4.5. Controlled Experiment

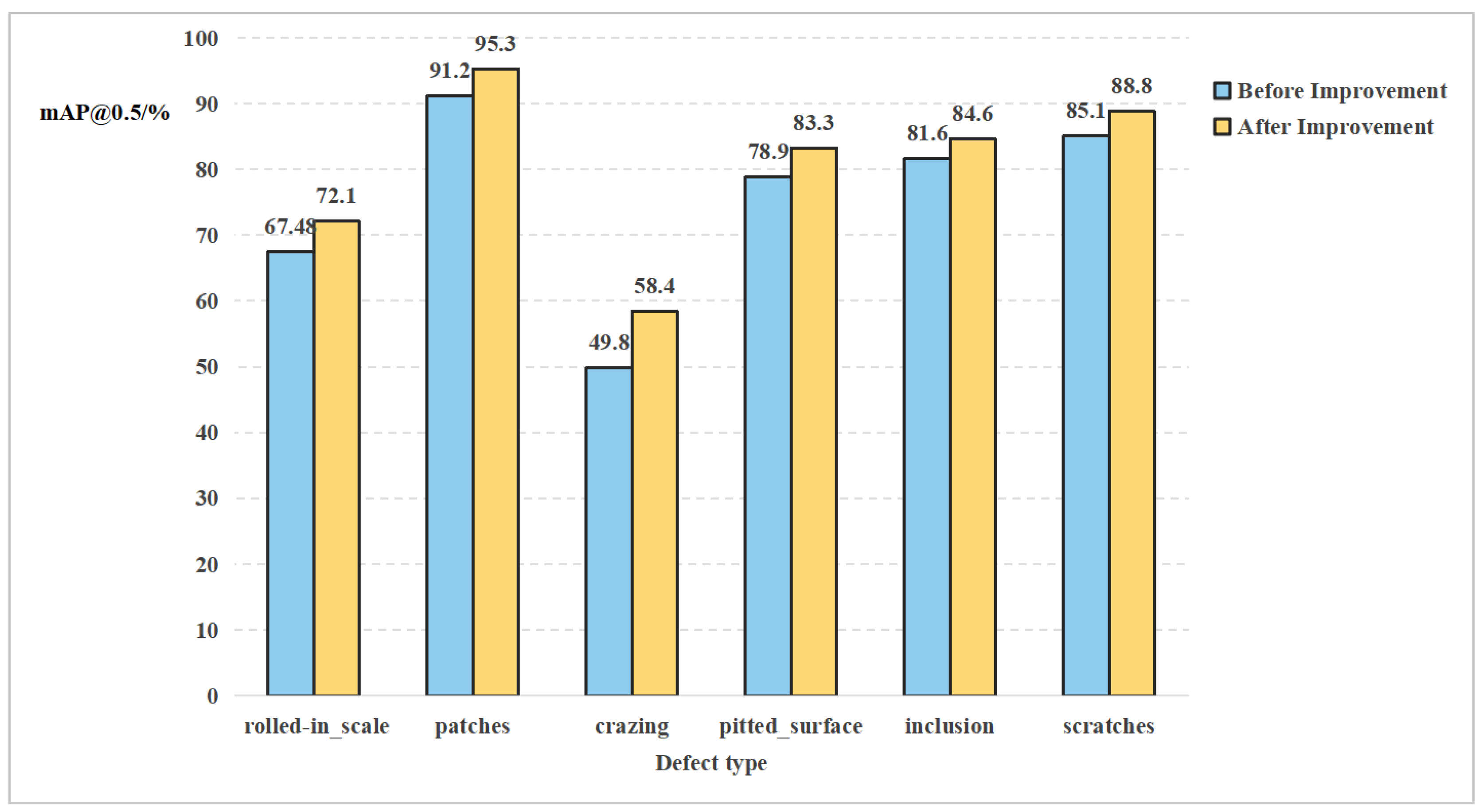

4.5.1. Comparison Before and After Improvement

To assess the effectiveness of the algorithm in detection tasks RM-YOLOv8 proposed in this paper on various types of surface imperfections in steel strips, the average precision of the original YOLOv8 and RM-YOLOv8 in detecting various types of defects on hot-rolled steel strips was compared. The results of the comparison are illustrated in

Figure 14.

As depicted in

Figure 14, the proposed algorithm demonstrates effective detection across all defect types.

Among them, the mAP of crazing defects increased by 8.6%, the mAP of rolled-in scale defects rose by 4.62%, and the mAP of the remaining defect types also increased by approximately 3–4% each.

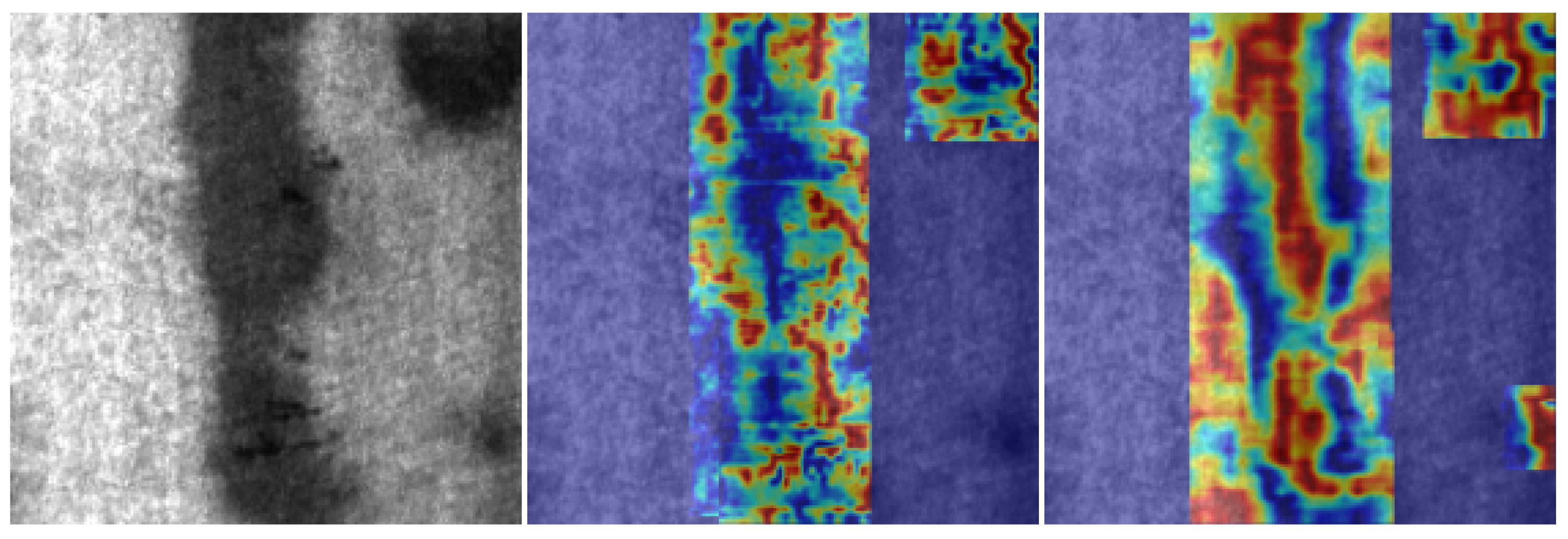

Furthermore, to assess the attention module’s focus on the target, To validate defect localization capability, Grad-CAM++ [

30] visualization is employed.

Figure 15 shows brighter, concentrated color regions indicating accurate defect positioning.

Based on the heat map in

Figure 15, incorporating both the CBAM and Cloformer attention mechanisms noticeably enhances the model’s focus on steel strip defects, the improved YOLOv8s model exhibits a stronger response at the steel strip’s defect locations compared to the original YOLOv8s.

4.5.2. Comparison with Other Algorithms

Further validation of the improved algorithm’s detection performance is conducted, a comprehensive comparison was conducted on the NEU-DET dataset under consistent experimental conditions and parameter settings. The evaluation included representative models such as SSD [

31], Faster R-CNN, EfficientDet-D1 [

32], RT-DETR-1 [

33], GoldYOLO-n [

34],along with classic and latest YOLO series models. The experimental results are detailed in

Table 3.

Comprehensive evaluations highlight that the enhanced YOLOv8s achieves optimal compromise between detection accuracy and computational efficiency on the NEU-DET dataset. When benchmarked against the conventional two-stage Faster R-CNN, our enhanced YOLOv8s model achieves a 4.01% increase in mAP, cuts down parameters by 80.2%, and delivers an 8.3-fold improvement in inference speed. Moreover, compared to YOLOv5s, it attains a 4.8% higher detection accuracy while keeping the inference speed nearly unchanged.Although GoldYOLO-n excels in lightweight design, its mAP50 is still lower than that of our model.Notably, RT-DETR-1 based on Transformer, despite having a comparable accuracy about 80.3%, has significantly higher computational cost and slower inference speed than our model, making it difficult to meet the real-time detection requirements in industrial applications. Additionally, the community-improved models YOLOv12-n and YOLOv11-n, despite having extremely low parameter counts, neither surpass our model in terms of accuracy nor speed, thus verifying the necessity of the modular optimization in this study. These results confirm the proposed method’s advantages in industrial defect detection: high precision with low resource consumption.

5. Discussion

The excellent performance of the improved YOLOv8s on the NEU-DET dataset validates the effectiveness of lightweight design and task-specific optimization. As opposed to YOLOv5s, although model parameter size has slightly increased, the mAP has improved by 4.8%, mainly owing to the implementation of the Cloformer and CBAM modules, which significantly enhance the model’s ability to locate tiny cracks. Meanwhile, by introducing DWConv and PConv, the model significantly reduces redundant computations while retaining the ability to extract key features. The number of parameters is 80.2% less than that of Faster R-CNN, and the computational cost is only 26.3% of SSD300. However, it was observed that when defect size falls below 10×10 pixels (as with crazing defects), detection accuracy drops by around 20%. This decline is likely due to the low-resolution limitations of the feature pyramid at the lower levels. Moreover, the deployment efficiency of the model on embedded devices has not been verified and still requires further experimental verification and optimization. Future research will explore the joint optimization of super-resolution reconstruction and detection tasks to further enhance the sensitivity to microscopic defects.

6. Conclusions

Addressing lightweight network design and small target recognition challenges in hot-rolled steel strip defect detection, this study presents an optimized YOLOv8s model. Results show significant improvements over the original model in accuracy, model size, and inference speed. Moreover, when measured against current mainstream surface defect detection algorithms, the improved YOLOv8s not only boosts detection speed but also offers a lightweight design that is well-suited for edge deployment in industrial scenarios. These results provide valuable insights and serve as a reference for advancing surface defect detection in hot-rolled strip steel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,B.T.Q.; methodology,B.T.Q.; software,B.T.Q.; validation, B.T.Q.; resources,B.T.Q.; writing—original draft preparation,B.T.Q.; writing—review and editing,B.T.Q.; visualization, B.T.Q.; supervision,B.T.Q.; project administration,B.T.Q.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. The data presented in this study can be requested from the authors.

Acknowledgments

When reviewing and preparing the methods mentioned in this manuscript, the deepseek artificial intelligence language model was utilized to enhance the readability and grammatical accuracy of the text. The authors reviewed and revised the generated content to ensure its accuracy and consistency with the original work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fang, F.; Hu, X.-j.; Zhang, B.-m.; Xie, Z.-h.; Jiang, J.-q. Deformation of dual-structure medium carbon steel in cold drawing. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2013, 583, 78–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gong, J.; Li, B. Image Information Restoration of Automotive Strip Steel Surface Based on Sparse Representation. Hunan Daxue Xuebao/Journal of Hunan University Natural Sciences 2021, 48, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.K.; Girshick, R.B.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2015, 779–788.

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Gao, X.-w.; Luo, L. X-SDD: A New Benchmark for Hot Rolled Steel Strip Surface Defects Detection. Symmetry 2021, 13, 706.

- Li, S.; Wang, X. YOLOv5-based Defect Detection Model for Hot Rolled Strip Steel. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2171, 012040. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shi, T.; Liao, J. Surface Defect Detection Algorithm of Hot-Rolled Strip Based on Improved YOLOv7. IAENG International Journal of Computer Science 2024, 51, 345-354.

- Zhang, W.K.; Liu, J. Steel Surface Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8s. Journal of Beijing Information Science & Technology University (Natural Science Edition) 2023, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Gong, Z.Z.; Liang, Z.Q. Surface Defect Detection of Strip Steel Based on Improved YOLOv5s Algorithm. Machine Tool & Hydraulics 2024, 181–186. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Cheng, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; Tang, X. Real-Time AIoT for UAV Antenna Interference Detection via Edge-Cloud Collaboration. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Huang, H.; Guan, J.; He, R. Rethinking Local Perception in Lightweight Vision Transformer. 2023.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. Springer, Cham 2018.

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 21-26 July 2017, 2017; pp. 1800-1807.

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.h.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 17-24 June 2023, 2023; pp. 12021-12031.

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. ArXiv 2022, abs/2209.02976.

- Hussain, M. YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the Rise of YOLO and Its Complementary Nature toward Digital Manufacturing and Industrial Defect Detection. Machines 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Li, G.W.; Chang, D.F.; Du, J.W. A Surface Defect Detection Method for Hot-Rolled Strip Steel Based on Improved YOLOv8s. Ship Engineering 2025, 124–131. [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. ArXiv 2020, abs/2004.10934.

- Sun, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N. Context-aware Cross-level Fusion Network for Camouflaged Object Detection. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 21-26 July 2017, 2017; pp. 936-944.

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 18-23 June 2018, 2018; pp. 8759-8768.

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized Focal Loss: Learning Qualified and Distributed Bounding Boxes for Dense Object Detection. ArXiv 2020, abs/2006.04388.

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. ArXiv 2019, abs/1911.08287.

- Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yu, Y. DenseBox: Unifying Landmark Localization with End to End Object Detection. ArXiv 2015, abs/1509.04874.

- Wu, C.K.; Huang, F.; Li, B.; Gu, L.L.; Liu, L.; Fang, Y.M. DMS-YOLOv8 Slab Detection Algorithm Based on Improved Depthwise Separable Convolution and Hybrid Attention Mechanism. Metallurgical Automation 2024, 31–39.

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. ArXiv 2017, abs/1704.04861.

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Borovec, J.; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; ... Thanh Minh, M. ultralytics/yolov5: v6.0-YOLOv5n ’Nano’ models, Roboflow integration, TensorFlow export, OpenCV DNN support. Zenodo 2021.

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017.

- Buslaev, A.V.; Parinov, A.; Khvedchenya, E.; Iglovikov, V.I.; Kalinin, A.A. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. ArXiv 2018, abs/1809.06839.

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized Gradient-Based Visual Explanations for Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 12-15 March 2018, 2018; pp. 839-847.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2015.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 13-19 June 2020, 2020; pp. 10778-10787.

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2024, pp. 16965–16974.

- Wang, C.; He, W.; Nie, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Han, K. Gold-YOLO: Efficient Object Detector via Gather-and-Distribute Mechanism. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; Levine, S., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2023, Vol. 36, pp. 51094–51112.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).