Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected livelihoods, health, and economies globally.[

1] The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared it a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020, a status that remained until May 5, 2023.[

2] Although the PHEIC status was lifted, COVID-19 remains a global health threat.[

2] As of December 1, 2024, approximately 777 million cases and 7 million deaths had been reported.[

3] Despite occasional surges, COVID-19 incidence and mortality have declined. While early public health interventions like lockdowns contributed to containment efforts, vaccination has played a pivotal role in reducing infection with SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19-related mortality.[

4] To date, approximately 13∙6 billion vaccine doses have been administered globally.[

3]

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine received emergency use authorisation in December 2020 and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in August 2021,[

5] becoming the first authorised RNA vaccine. This milestone paved the way for rapid approval of subsequent vaccines.[

6] Accelerated development and deployment were driven by advanced technology, existing infrastructure, and prior research on related viruses like the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

(MERS-CoV).[

7] Although vaccination has significantly reduced COVID-19 incidence and mortality, SARS-CoV-2’s rapid evolution diminishes the effectiveness of existing vaccines. Moreover, immune responses from existing vaccines wane over time,[

8] with breakthrough infections occurring as early as nine post-vaccination.[

9] This highlights the continued need for COVID-19 vaccine research.[

10]

Since the onset of the pandemic, Africa has faced challenges such as limited research participation, slow vaccine rollout, and low uptake.[

11] The pandemic’s impact was exacerbated by weak healthcare infrastructure.[

12] Despite a pressing need for vaccines, African countries had minimal involvement in COVID-19 vaccine research and development. Evaluating vaccines across diverse demographics is crucial, as immune responses vary by factors like race,[

13] geography,[

14] and local immune microenvironments shaped by chronic infections and inflammation.[

15]

The self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) vaccine developed at Imperial College London was among the earliest SARS-CoV-2 vaccines evaluated in Africa. Its ability to self-amplify within cells allows for smaller doses, potentially facilitating expanded coverage and reducing production costs.[

16,

17] This vaccine demonstrated excellent safety and immunogenicity in non-human primates[

18] and in Phase 1/2a “COVAC1” trials in the United Kingdom.[

19,

20] In Uganda, the COVAC Uganda trial evaluated a second-generation saRNA vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein in SARS-CoV-2 seronegative and SARS-CoV-2 seropositive participants at the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit in Masaka, Uganda. This version featured a vector modification incorporating an ORF4 motif to reduce innate immune responses to the vector.[

21]

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

This single-centre, non-randomised phase 1 clinical trial assessed the safety and immunogenicity of a Lipid Nano Particle-new Corona Virus saRNA (LNP-nCOV saRNA-02) vaccine, administered at 0 and 4 weeks. Eligibility criteria included age 18-45 years, willingness to provide informed consent, and adherence to contraception requirements: female participants agreed to using highly effective contraception, while male participants committed to avoiding pregnancy with their partner from screening until 18 weeks after the second injection. Participants were required to avoid all vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines, from four weeks before the first dose until four weeks after the second. Those seeking Ministry of Health-recommended vaccines thereafter received appropriate information and referrals. Participants were also required to adhere to the 24-week visit schedule, document reactogenicity events in vaccine diaries, provide required samples, and grant access to trial-related and medical records. Details on eligibility criteria, screening, and enrolment are available in a previously published paper.[

22]

Procedures During the Screening Period

Screening was conducted within 42 days before enrolment. The schedule of study procedures is summarised in Supplementary Information S1. Participants received written information about the product, trial design, and data collection in English or Luganda and had the opportunity to ask questions. Those who agreed to participate provided written consent, completed a screening questionnaire and provided samples for screening investigations.

Data were collected on demographics, medical history, and current medications. Information on contraception use was collected to assess pregnancy risk. Screening included measurements of vital signs, weight (kg), height (cm), oxygen saturation, lymph node evaluation, and skin inspection for severe eczema. A comprehensive respiratory, cardiovascular, abdominal, and neurological examination was performed.

Blood samples were collected and analysed for complete blood count (Haemoglobin, lymphocytes, neutrophils, platelets) and biochemistry [creatinine, Aspartate Transaminase (AST), Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT), Alanine Transaminase (ALT), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, and non-fasting glucose)]. Additional tests included tests for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, SARS-CoV-2 antigen (if COVID-19 was suspected), Hepatitis C antibodies, and HIV antibodies, with HIV screening conducted per the Uganda Ministry of Health HIV testing algorithm [

23].

Urine dipstick tests screened for glucose, blood, white blood cells, nitrite and protein. Volunteers with Grade 1 abnormalities in haematology, biochemistry or urinalysis (per FDA toxicity grading scale for preventive vaccine clinical trials [

24]) were retested once. Those with normal repeat results could participate at the investigator's discretion, while those with persistent abnormalities were excluded and referred for management if needed. Female participants underwent a urine pregnancy test for Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin (HCG).

SARS-CoV-2 Serology Testing

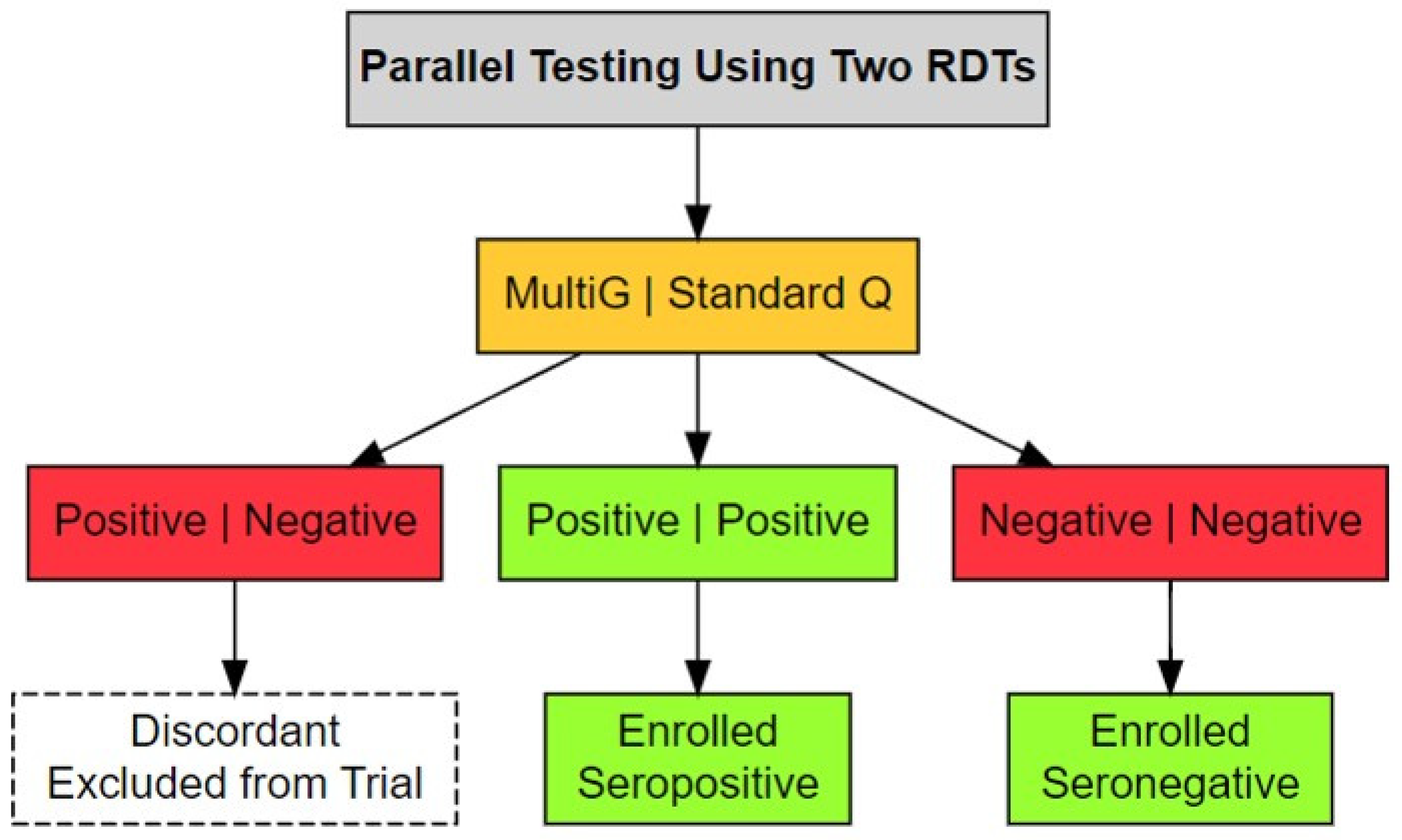

Blood samples obtained by venepuncture were tested using two SARS-CoV-2 serology rapid test kits: i) Multi G (MGFT3), Multi-G bvba, Belgium; ii) Standard Q (Standard Q COVID-19 IgM/IgG Plus), SD Biosensor, Inc., South Korea. Both kits, which detect IgM and IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in serum, plasma, or whole blood, demonstrated

≥98% specificity and sensitivity in a validation study in Uganda.[

25] Participants were classified as SARS-CoV-2 seropositive if both test kits detected antibodies and seronegative status if neither did. Those with discordant results (positive on one kit, negative on the other) were categorised as having indeterminate serostatus and excluded from the trial (

Figure 1). Stored enrolment samples were rested using rapid tests and ELISA, with participant’s final SARS-CoV-2 serostatus determined from these results.

Eligibility Assessment and Procedures at Enrolment

At the enrolment visit, a study clinician confirmed eligibility by reviewing screening results, updating medical history, assessing COVID-19 vaccination status, medications, and contraceptive use, and conducting a repeat physical examination. Female participants underwent a pregnancy test, with only those testing negative proceeding to enrolment. Eligible participants were then enrolled, had blood samples collected for safety and immunogenicity assessments, and received the first vaccine dose.

Procedures for Assessing Safety

Local and systemic solicited adverse events were monitored after each vaccination. Participants remained at the clinic for up to 60 minutes post-vaccination to observe any immediate reactions. They were given a vaccine diary card to record and grade adverse events occurring within seven days. A study nurse reviewed the vaccine diary card with participants, providing instructions on how to complete it. Blood samples were collected at each visit for safety evaluations, and appropriate action taken for abnormal results. Vital signs were measured at each visit, along with physical examinations, including injection site assessments, on the day of vaccination and one week later. Symptom-directed physical examinations were conducted at follow-up visits. Participants were routinely asked about COVID-19 symptoms and instructed to report any symptoms to facilitate timely SARS-CoV-2 testing. Unsolicited adverse events were documented at each study visit and via telephone follow-up two days after vaccination, with study doctors recording diagnoses, symptoms, onset and resolution dates.

Procedures for Assessing Primary Immunogenicity Endpoint

Blood samples were collected at weeks 0, 4, 6, and 12 to assess immune responses to the vaccine (

S1). The primary outcomes included serum IgG antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein, measured by ELISA two weeks after the first and second vaccinations. Functional antibody responses were assessed by a pseudovirus neutralisation assay (PNA) two weeks after the second vaccination.[

26] All assays were performed at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit laboratories in Entebbe, Uganda.

Statistical Methods

The sample size calculation aimed to detect a difference of 0∙7 on the log10 IC50 scale (corresponding to a slope of 1∙4) for SARS-CoV-2 neutralisation at six weeks (two weeks post-second vaccination) between seropositive and seronegative participants, with a 97% power (2α=0∙05) and an estimated standard deviation of approximately 1∙5 for neutralisation log10 IC50 values. Data were captured in electronic case report forms using the REDCap software (Westlake, TX, USA) and transferred to Stata 18∙0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for cleaning and analysis. A CONSORT flow diagram was used to illustrate participant enrolment, follow-up, and analysis. Baseline characteristics and safety outcomes were summarised as counts and percentages and compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test. Given the skewed distribution of the neutralisation data, an offset from zero was added to the markers before the analysis. Linear mixed-effects models, with a random participant term and adjustments for age and sex, were used for data analysis.

Results

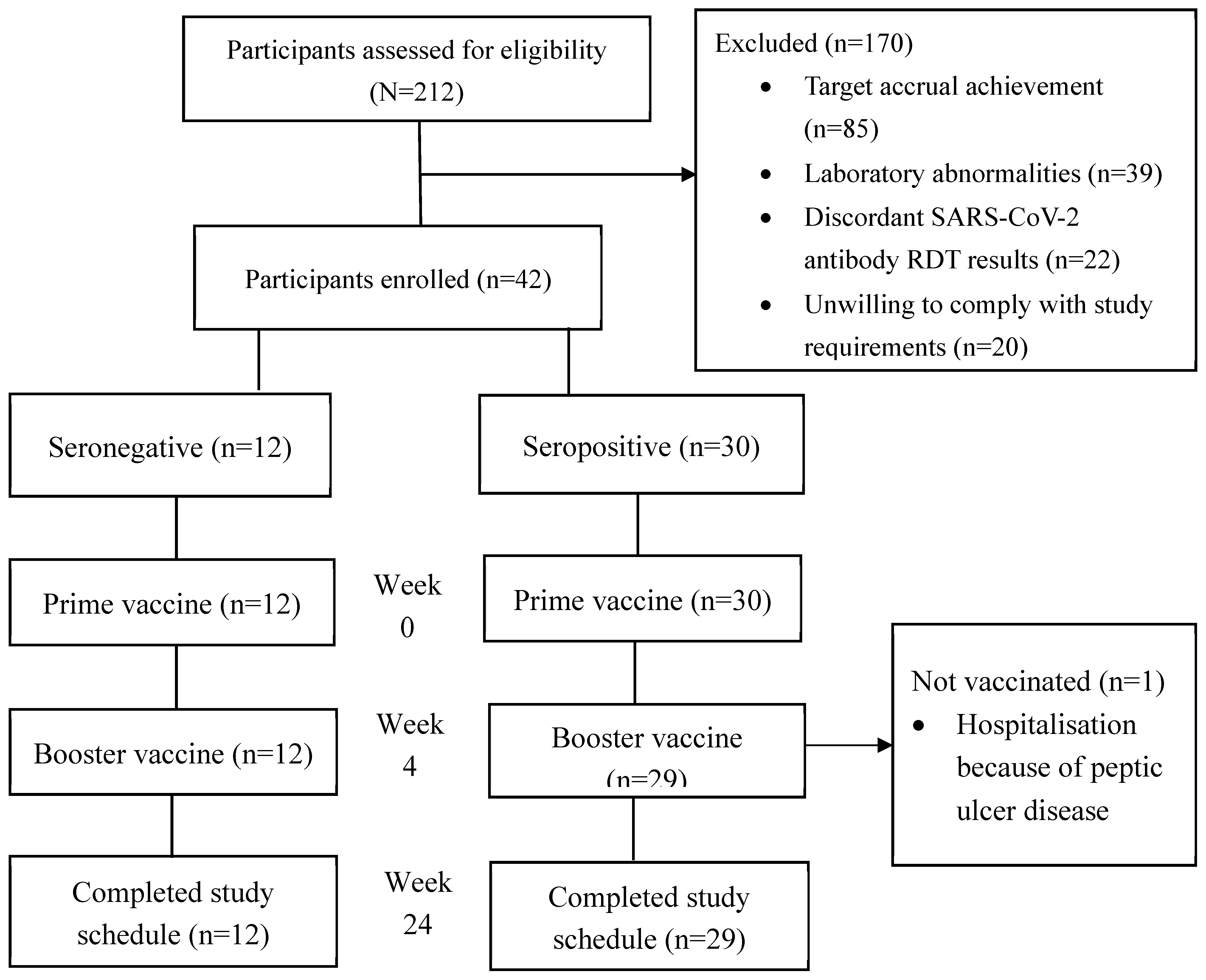

A total of 212 participants (51% male, n=109) were screened between December 2021 and April 2022. Of these, 42 participants were enrolled, with 21 initially classified as seronegative and 21 as seropositive for SARS-CoV-2. Exclusion reasons included closure of enrolment after achieving target accrual (n=85), laboratory abnormalities (n=39), discordant SARS-CoV-2 antibody rapid test results (n=22), unwillingness to comply with study requirements (n=20), and other reasons (n=43) as shown in

Figure 2 (Trial Profile). Repeat screening of enrolment samples revealed seroconversion in 9 initially seronegative participants, resulting in 30 being assigned to the seropositive arm and 12 to the seronegative arm.

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the enrolled participants. The mean age was 30∙2 (SD±8∙3) years. The distribution of participants characteristics was similar across both arms.

Reactogenicity

Systemic reactions were similar across study arms following both the prime and booster vaccinations. The most common reactions following the prime vaccination were fatigue/malaise (47∙6%), headache (42∙9%) and chills/shivering (40∙1%). After the booster, these reactions occurred more frequently: fatigue/malaise (63∙4%), headache (61∙0%), and chills/shivering (58∙5%). No grade 3 or higher systemic reactions were reported following the prime vaccination, but one participant in the seropositive arm experienced ≥grade 3 chills/shivering and headache after the booster. Local reactions, mostly grade 1 and 2, were comparable between arms, with pain (71∙4%) and tenderness (66∙7%) being the most common after the prime vaccination. No erythema or swelling was reported. Comparable reactions and frequencies were observed after the booster vaccination. A summary of reactogenicity events is provided in

Table 2.

Other Adverse Events

One serious adverse event, a prolonged hospitalization due to peptic ulcer disease exacerbation in a SARS-CoV-2 seropositive participant, was reported. While the event was considered unlikely to be related to vaccination, the Trial Steering Committee advised against a booster dose, citing the participant’s ineligibility due to active disease and the inability to fully exclude vaccine-related exacerbation. Unsolicited clinical adverse events were more common after the booster dose (n=137) than the prime dose (n=32), with similar distribution across seropositive and seronegative arms.

Grade 3 or higher laboratory abnormalities were more frequent after the second vaccination than the first (39 vs. 9) (

Table 3), with neutropenia, lymphopenia, glucose abnormalities being most common. These abnormalities were more prevalent in the SARS-CoV-2 seropositive arm compared to the SARS-CoV-2 seronegative arm after both the first (7 vs. 2) and second vaccinations (27 vs. 12), with notable differences in thrombocytopenia (first: 4 vs. 0; second: 8 vs. 0). None of the grade 3 or higher clinical AEs or laboratory abnormalities were attributed to the vaccine.

Immunogenicity

Significant Elevation of Spike-Specific IgG Binding Antibodies Following Two Vaccinations

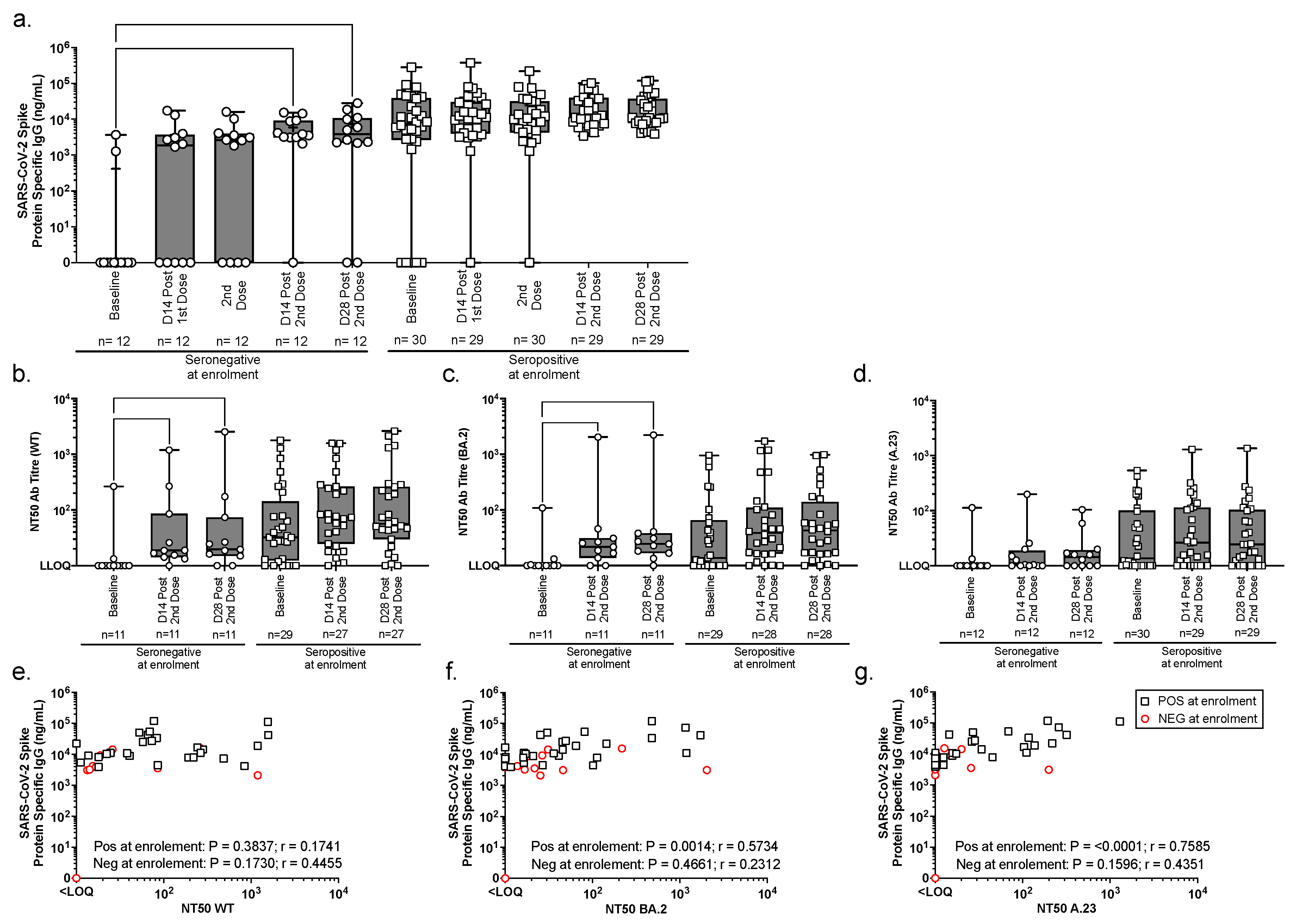

SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IgG antibodies increased significantly after two vaccinations, as evidenced by the serum IgG binding antibody concentrations measured by ELISA at baseline and two-weeks post-immunisation in 42 participants (

Figure 3a). Among 12 seronegative participants at enrolment, 91∙6% (11/12) developed IgG responses. The median IgG concentration rose from 0 ng/mL at baseline to 3,695 ng/mL (IQR 3101-9109) at 14 days post-second dose (p=0∙0003 at 14 days; p=0∙0001 at 28 days) (

Figure 3a,

Table 5). All initially seropositive participants remained so post-vaccination, with median IgG levels rising from 7,496 ng/mL (IQR 2,662-3,8969) at baseline to 11,028 ng/mL (IQR 7828-37563) at 14 days post-second dose (

Figure 3a,

Table 5). Although this approximately two-fold increase was not statistically significant, it suggests a boosting effect. These findings highlight the vaccine’s strong immunogenicity in seronegative individuals and its potential to enhance pre-existing immunity (

Figure 3,

Table 4).

Improved Neutralising Antibody Response Post-Second Vaccination Across Multiple SARS-CoV-2 Variants

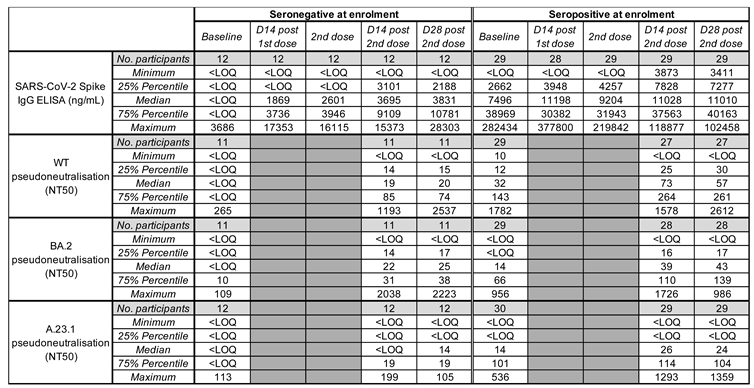

Neutralising activity of serum antibodies was assessed using a pseudoneutralisation assay with circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants [wild-type (WT), BA.2, and A.23.1]. Assays were conducted on serum samples collected at baseline, 14 and 28 days after the second vaccination. Among seronegative participants at enrolment, median NT50 neutralising titres 14 days after vaccination were: WT (19; IQR 14-85), BA.2 (22; IQR 14-31), and A.23.1 [<limit of quantification (LOQ); IQR <LOQ-19]. Significant increases in neutralisation titres were observed for WT (p=0∙0120 and p=0∙0315) and BA.2 (p=0∙0315 and p=0∙0013) at 14 and 28 days (

Figure 3b-d,

Table 5). Although A.23.1 neutralisation remained low, notable response rates were observed: from 2/11 to 10/11 for WT, 3/11 to 9/11 for BA.2, and 2/12 to 7/12 for A.23.1, indicating an overall improvement post-vaccination.

Among seropositive participants, neutralising antibody titres (NT50) increased against all variants 14 days after the second vaccine dose, though these changes were not statistically significant. Median NT50 values rose from 32 (IQR 12-143) to 73 (IQR 25-264) for WT, 14 (IQR <LOQ-66) to 39 (IQR 16-110) for BA.2, and 14 (IQR <LOQ-101) to 26 (IQR <LOQ-114) for A.23.1 (

Figure 3b-d,

Table 5). The proportion of participants with detectable neutralising responses also increased: for WT, from 79∙3% (23/29) at baseline to 96∙3% (26/27) post-immunisation, for BA.2, from 62∙1% (18/29) to 89∙3% (25/28); and for A.23.1, from 63∙3% (19/30) to 79∙3% (23/29). A significant correlation between SARS-CoV-2 serum IgG levels and neutralising activity was found in seropositive participants post-second dose, particularly for BA.2 (p=0∙0014) and A.23.1 (p<0∙0001) (

Figure 3e-g).

The results suggest enhanced neutralising antibody responses post-vaccination, particularly against the WT and BA.2 variants, with broader activity, including A.23.1. The data demonstrate the vaccine's ability to boost neutralising antibody levels in both seronegative and seropositive individuals, emphasising its potential to enhance immune protection across diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Table 5 presents geometric mean (GM) and adjusted geometric mean (aGM) titres of spike-specific IgG binding and neutralising antibody responses, stratified by SARS-CoV-2 serostatus. Data cover two weeks post-first and second vaccine doses. aGM values, adjusted for baseline antibody levels, sex, and age, compare responses between seropositive and seronegative participants. 'ND' denotes unavailable data. The aGM titres illustrate the impact of prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure on vaccine-induced immunity.

The aGM of spike-specific IgG binding antibodies was significantly higher in the seropositive group compared to the seronegative group two weeks post-vaccination, after both the first (aGM: 1∙72, 95% CI: 1∙06–2∙37) and second dose (aGM: 1∙41, 95% CI: 0∙87–1∙94). Similarly, the aGM for nucleocapsid-specific IgG was higher in seropositive participants, reflecting prior exposure. However, neutralising antibody titres did not differ significantly between groups across the three variants tested after the second dose (

Table 5).

Discussion

We present findings from COVAC Uganda, a phase 1 trial evaluating the safety and immunogenicity of LNP-nCOV saRNA-02, a saRNA vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein, in seronegative and seropositive Ugandan participants. To our knowledge, this is the first saRNA vaccine trial reported from Africa.

Our findings demonstrate that the vaccine was safe and well tolerated, with mostly mild to moderate transient reactogenicity. Similarly, the UK-based COVAC1 phase 1 trial, which evaluated a similar saRNA vaccine, demonstrated its safety and tolerability. COVAC1, a dose-finding trial, administered doses from 0∙1μg to 10∙0 μg, with a booster at the same dose after four weeks.[

26] However, moderately severe reactogenicity events were more frequent in COVAC1 than in COVAC Uganda.

A phase 2a trial also in the UK, which included a more diverse demographic with older participants and individuals with co-morbidities, evaluated the same vaccine at fixed doses of 1 μg (prime) and 10 μg (boost) administered 14 weeks apart. That study did not find any safety concerns.[

20] However, tolerability was dose-dependent, with higher frequency and severity of adverse reactions after the 10 μg dose, where 17% of recipients experienced grade 3 adverse events. In both UK trials, adverse reactions were more common in the younger participants, a trend not observed in COVAC Uganda, likely due to a less diverse age profile.

In our trial, reactogenicity was similar between participants with and without prior infection, with only mild to moderate local and systemic reactions reported. Thrombocytopenia occurred more frequently after the boost dose, particularly in the seronegative arm, but all cases were asymptomatic and resolved before follow-up completion. Thrombocytopenia has been observed with other COVID-19 vaccines where some cases presented with symptoms.[

27,

28] The study recorded one serious adverse event: hospitalization for exacerbated peptic ulcer disease in the SARS-CoV-2 seropositive arm after the prime dose, considered unlikely to be vaccine-related.

The vaccine elicited strong humoral responses in SARS-CoV-2 seronegative participants, with 91∙6% developing Spike-specific IgG antibodies 14 days after the boost. Antibody levels in these individuals matched or exceeded those in seropositive individuals, highlighting the vaccine's ability to prime naïve immune systems. These findings align with evidence that saRNA has potential to elicit robust humoral responses in unexposed populations.[

29] However, durability remains uncertain, as data from other platforms suggest neutralising antibodies may decline within six months following vaccination.[

30,

31] Given the rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants, antibody longevity and breadth are key considerations for future vaccine design.[

32,

33]

SARS-CoV-2 seropositive participants exhibited a moderate antibody boost, reinforcing pre-existing immunity, consistent with findings from other COVID-19 vaccines.[

34] Despite higher baseline antibody levels, their post-vaccination increase was less pronounced than in seronegative participants, likely due to a ceiling effect.[

34] The nearly two-fold increase in IgG levels, though not statistically significant, suggests a strong boost response.

The lack of a significant difference in neutralising antibody titres between seropositive and seronegative groups, despite higher binding antibody levels, suggests a potential dissociation between humoral response and neutralisation capability. This stem from the spike glycoprotein's antigenic structure, which induces binding but not necessarily neutralising antibodies.[

35] While the saRNA vaccine elicits strong humoral responses, further research is needed to fully elucidate its functional protective mechanisms.

The strong immune responses observed in our study contrast sharply with the results observed in the UK trials, where similar saRNA vaccines elicited weaker responses.[

20,

26,

36] This difference may partly be attributable to the inclusion of the ORF4a gene, which could modulate immune responses.[

21] Ongoing investigations, including a transcriptomics study, aim to further characterise the innate immunity and T-cell responses in this Ugandan cohort.

saRNA technology is still novel, with few vaccines assessed globally. The first approved saRNA vaccine, ARCT-154 (CSL and Arcturus Therapeutics), received approval in Japan in November 2023 based on a phase 3 trial demonstrating superior immunogenicity and a safety over BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.[

37], Our findings support the immunogenic potential of saRNA platforms to elicit high antibody titres with small doses due to their self-amplifying nature.

A potential limitation of this study is the small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the results. However, the consistent trends observed in both seronegative and seropositive participants provide valuable insights into the immunogenic potential of saRNA vaccines, particularly in an African population where vaccine trials remain limited. Larger and more diverse studies are needed to validate these findings. Additionally, the 42-day screening period led to some participants who tested SARS-CoV-2 negative acquiring the virus before enrolment, as confirmed by repeat testing. This resulted in an imbalance between two groups, with a higher number of seropositive than seronegative individuals. Lastly, the absence of a placebo group limits the ability to attribute all observed effects solely to the vaccine.

In conclusion, this study provides important evidence of the immunogenicity of a novel saRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine in an African population, showing strong induction of spike-specific binding antibodies in both seronegative and seropositive individuals. While binding antibody responses were robust, the relatively modest neutralising antibody responses suggest that the potential for further optimisation of the vaccine platform. These findings enhance the understanding of saRNA vaccines and highlight their potential role in priming naïve immune systems and boosting pre-existing immunity, offering important insights for future vaccine development and pandemic preparedness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to the data and accept responsibility for publication. JS, AA, JL, HMC, have accessed, analysed, and verified all the data reported in the trial. All authors have read and reviewed the final manuscript. PK, RJS, and ER conceptualised the trial; JS, HMC, LK, FN, GKO, BG, SJ, JKS, and LRM, conducted laboratory analyses and assays; RJS and PK acquired funding; JK, ER, SJo, and BFP undertook the project administration; JK, JS, JL, and wrote the first draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care using UK Aid funding and is managed by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, grant number: EP/R013764/1). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all study participants, the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Masaka Community Advisory Board, the Trial Steering Committee, and all members of the study team at the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the protocol, institutional Standard Operating Procedures, Good Participatory Practice, and International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines and regulatory requirements. The protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee (Ref: GC/127/829), the National Drugs Authority (Ref: CTA 0186), the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Ref: HS164/ES), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 26510), and Imperial College London Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 21IC6703). Written informed consent was obtained before study procedures. Participants diagnosed with HIV or other chronic conditions received counselling and referrals for comprehensive care.

Data Sharing

The de-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article are stored in a non-publicly available repository (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine [LSHTM] Data Compass), together with a data dictionary. Data are available on request. Researchers who would like to access the data may submit a request through LSHTM Data Compass, detailing the data requested, the intended use for the data, and evidence of relevant experience and other information to support the request. The request will be reviewed by the Principal Investigator in consultation with the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute (MRC/UVRI) and LSHTM data management committee, with oversight from the UVRI and LSHTM ethics committees. In line with the MRC policy on data sharing, there will have to be a good reason for turning down a request. Patient Information Sheets and consent forms specifically referenced making anonymised data available and this has been approved by the relevant ethics committees. Researchers given access to the data will sign data sharing agreements which will restrict the use to answering pre-specified research questions.

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- WHO. Impact of COVID-19 on people's livelihoods, their health and our food systems. 2020.

- Wise, J. Covid-19: WHO declares end of global health emergency. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2023.

- WHO. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. 2024. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines?n=c (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Hernández Bautista, P.F.; Grajales Muñiz, C.; Cabrera Gaytán, D.A.; et al. Impact of vaccination on infection or death from COVID-19 in individuals with laboratory-confirmed cases: Case-control study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0265698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: First Full Regulatory Approval of a COVID-19 Vaccine, the BNT162b2 Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccine, and the Real-World Implications for Public Health Policy. Med Sci Monit 2021, 27, e934625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhud, D.D.; Zokaei, S. A brief overview of COVID-19 vaccines. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2021, 50, i–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, K.; Sitar, S.; Graham, B.S.; Mascola, J.R. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: Milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity 2021, 54, 1636–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Joyal-Desmarais, K.; Ribeiro, P.A.B.; et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: Findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2023, 11, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwanga, J.; Ankunda, V.; Katende, J.S.; Baine, C.; Oluka, G.K.; Odoch, G.; Nantambi, H.; Mugaba, S.; Namuyanja, A.; Ssali, I.; et al. Sustained S-IgG and S-IgA Antibodies to Moderna's mRNA-1273 Vaccine in a Sub-Saharan African Cohort Suggests Need for the Vaccine Booster Timing Reconsiderations. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1348905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wu, C.; Gu, S.; Lu, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, C. WHO declares the end of the COVID-19 global health emergency: Lessons and recommendations from the perspective of ChatGPT/GPT-4. Int J Surg 2023, 109, 2859–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telegraph. 'Huge' impact on deaths and economies if Africa left behind for Covid vaccine, top official warns. 27 November 2020.

- Tessema, G.A.; Kinfu, Y.; Dachew, B.A.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare systems in Africa: A scoping review of preparedness, impact and response. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e007179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valier, M.R.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Mu, Y.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Children and Adolescents Aged 5-17 Years and Parental Intent to Vaccinate Their Children - National Immunization Survey-Child COVID Module, United States, December 2020-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluka, G.K.; Sembera, J.; Katende, J.S.; et al. Long-Term Immune Consequences of Initial SARS-CoV-2 A.23.1 Exposure: A Longitudinal Study of Antibody Responses and Cross-Neutralization in a Ugandan Cohort. Vaccines 2025, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dorst, M.; Pyuza, J.J.; Nkurunungi, G.; et al. Immunological factors linked to geographical variation in vaccine responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2024, 24, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Schnierle, B.S. Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccine Candidates: Alternative Platforms for mRNA Vaccine Development. Pathogens 2023, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourseif, M.M.; Masoudi-Sobhanzadeh, Y.; Azari, E.; et al. Self-amplifying mRNA vaccines: Mode of action, design, development and optimization. Drug Discovery Today 2022, 27, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruggi, G.; Mallett, C.P.; Westerbeck, J.W.; et al. A self-amplifying mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate induces safe and robust protective immunity in preclinical models. Mol Ther 2022, 30, 1897–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, K.M.; Cheeseman, H.M.; Szubert, A.J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine against COVID-19: COVAC1, a phase, I.; dose-ranging trial. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, A.J.; Pollock, K.M.; Cheeseman, H.M.; et al. COVAC1 phase 2a expanded safety and immunogenicity study of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakney, A.K.; McKay, P.F.; Bouton, C.R.; Hu, K.; Samnuan, K.; Shattock, R.J. Innate Inhibiting Proteins Enhance Expression and Immunogenicity of Self-Amplifying RNA. Mol Ther 2021, 29, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitonsa, J.; Kamacooko, O.; Ruzagira, E.; et al. A phase I COVID-19 vaccine trial among SARS-CoV-2 seronegative and seropositive individuals in Uganda utilizing a self-amplifying RNA vaccine platform: Screening and enrollment experiences. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2023, 19, 2240690. [Google Scholar]

- MoH. National HIV Testing Services Policy and Implementation Guidelines - Uganda. 2022. Available online: http://library.health.go.ug/communicable-disease/hivaids/national-hiv-testing-services-policy-and-implementation-guidelines-0.

- FDA. Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials. 2007.

- Lutalo, T.; Nalumansi, A.; Olara, D.; et al. Evaluation of the performance of 25 SARS-CoV-2 serological rapid diagnostic tests using a reference panel of plasma specimens at the Uganda Virus Research Institute. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 112, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, K.M.; Cheeseman, H.M.; Szubert, A.J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine against COVID-19: COVAC1, a phase, I.; dose-ranging trial. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Jariwal, R.; Adebayo, M.; Jaka, S.; Petersen, G.; Cobos, E. Immune Thrombocytopenia following COVID-19 Vaccine. Case Rep Hematol 2022, 2022, 6013321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H. COVID-19 vaccination and immune thrombocytopenia: Cause for vigilance, but not panic. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2023, 7, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.G.; de Alwis, R.; Chen, S.; et al. A phase I/II randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of a self-amplifying Covid-19 mRNA vaccine. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayart, J.L.; Douxfils, J.; Gillot, C.; et al. Waning of IgG, Total and Neutralizing Antibodies 6 Months Post-Vaccination with BNT162b2 in Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.P.; Zeng, C.; Carlin, C.; et al. Neutralizing antibody responses elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination wane over time and are boosted by breakthrough infection. Science Translational Medicine 2022, 14, eabn8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, N.; Zeinali, T.; Joukar, F.; et al. Mutational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: Impact on future COVID-19 vaccine strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, N.Z.; Liew, H.L.; Farouk, I.A.; et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Implications on Immune Escape, Vaccination, Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Viruses 2023, 15, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankunda, V.; Katende, J.S.; Oluka, G.K.; Sembera, J.; Baine, C.; Odoch, G.; Ejou, P.; Kato, L.; Kaleebu, P.; Serwanga, J.; et al. The Subdued Post-Boost Spike-Directed Secondary IgG Antibody Response in Ugandan Recipients of the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 Vaccine Has Implications for Local Vaccination Policies. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1325387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.O.; Jette, C.A.; Abernathy, M.E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 2020, 588, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, A.J.; Pollock, K.M.; Cheeseman, H.M.; et al. COVAC1 phase 2a expanded safety and immunogenicity study of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRNewswire. Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Approves CSL and Arcturus Therapeutics' ARCT-154, the first Self-Amplifying mRNA vaccine approved for COVID in adults. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).