1. Introduction

Mental health of children and young people is a global health challenge and is one of the core fundamental elements for health definition of the World Health Organizations[

1]. Many research studies perform associations between mental health and sociodemographic characteristics and the extensive performance of burnout symptoms in schoolchildren and academic students [

2]. Results from surveys through several countries indicate that Portuguese medical students were diagnosed with mental ill before medical school, with 15% being diagnosed during medical school[

3], also, it is confirmed that healthcare students suffer from the consequences of stress and burnout signs[

4,

5] . So on, Swiss and Italian adolescences addressed with school burnout, in which Italian students showed higher fatigue and cynicism that their Swiss peers [

6] , the prevalence of burnout in French pediatric residents was 37.4%, which is not associated with COVID-19 outbreak[

4], on the other hand Danish schoolchildren seem to have in general good mental health[

5].

Over the last decade, students’ well-being has been introduced and many approaches took place to explain and measure the effectiveness of education system and their impact in mental health of students[

6]. However, current trends seem to reveal that more students than ever suffers from burnout symptoms[

7]. In several studies, burnout has been found that affect the schoolwork and the future academic life as well as students’ later health as adults[

3,

7]. The major issue of this is that studies have been shown the association between burnout directly with anxiety and depressive symptoms[

7,

8]. Students, due to the nature of education, are overwhelming with a variety of curriculum activities and accomplishments. Evidence supports that students in higher education develop mental health issues including academic burnout as a result of multiple stressors that they faces[

9].

Student burnout is defined as a psychological syndrome caused by long-term exposure in stress events and pressure in school or academic environment. It is described through the three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, cynicism and sense of inadequacy[

3], and there is a high risk for depression and anxiety. Emotional exhaustion can cause a lack of satisfaction in academic liabilities, cynicism is due the lack of interest of social activities and the last symptom causes a decreasing academic performance, competence and achievement[

9]. As research shows, burnout could be the consequence to drop out of studies. As a result, several impacts in social and personal costs may be appeared and they are associated with low mental and physical health which can be connected with the emergence of suicidal ideation[

10].

According to the above, early detection of burnout signs and symptoms is in a high demand, nowadays. Wearable artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a valuable instrument for researchers for non-invasive approach in psychobiological monitoring[

11]. Wearable AI technology seems to be promising, precisely, in stress and burnout student detection[

12]. Using the recording of biomarkers such as heart rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), and electrodermal activity (EDA) in real time and continues, the detection of stress and anxiety is possible[

13,

14]. The potential of this work is to delight the role of smartwatches in mental health assessment, especially, in stress and burnout detection, the comparative AI predictive models and algorithms, ethical issues, future challenges and perspectives.

2. Objectives

Considering the importance of burnout symptoms such as stress, fatigue or anxiety in education and their impact in mental health in combination with the availability of a variety of wearable technology, have been synthesized the necessity of retrospective work that summarizes previous experiences and gives clear future directions. Therefore, the present study constitutes a systematic review of existing empirical studies and reveals the research aspects of burnout syndrome in students. The objective of this systematic literature review was to uncover the current uses of smartwatch wearable devices in detection of early behavioral patterns related with burnout in student population. Although, the general aspect was to find evidences about the AI wearable devices effectiveness in burnout identification, the research questions (RQs) that oriented and built this review were as follows:

-

RQ1.

What are the research purposes, subjects and behavioral patterns of the reviewed studies?

-

RQ2.

Which wearable devices, AI technology and AI predictive models are adopted in the reviewed studies?

-

RQ3.

Which surveys have been used in the reviewed studies and which mental disorder have been verified?

-

RQ4.

What challenges and limitations are stated in the reviewed studies?

-

RQ5.

What are the ethical considerations that participants had to handle during the usage of wearable AI technology?

-

RQ6.

What are the accuracy and performance of the surveyed systems and how they are calculated?

-

RQ7.

How the results of each study are exploited and which are the main findings of them?

3. Materials and Methods

This review follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement[

29]. PRISMA Statement is the most commonly guidance that have been used by authors and reviewers, and reports the whole literature search procedure[

30]. Also, PRISMA ensures the quality of reports and solves methodological issues in search strategy and study assessment[

31]. Current study utilizes the PRISMA checklist to verify that each search component is completely reported and reproducible.

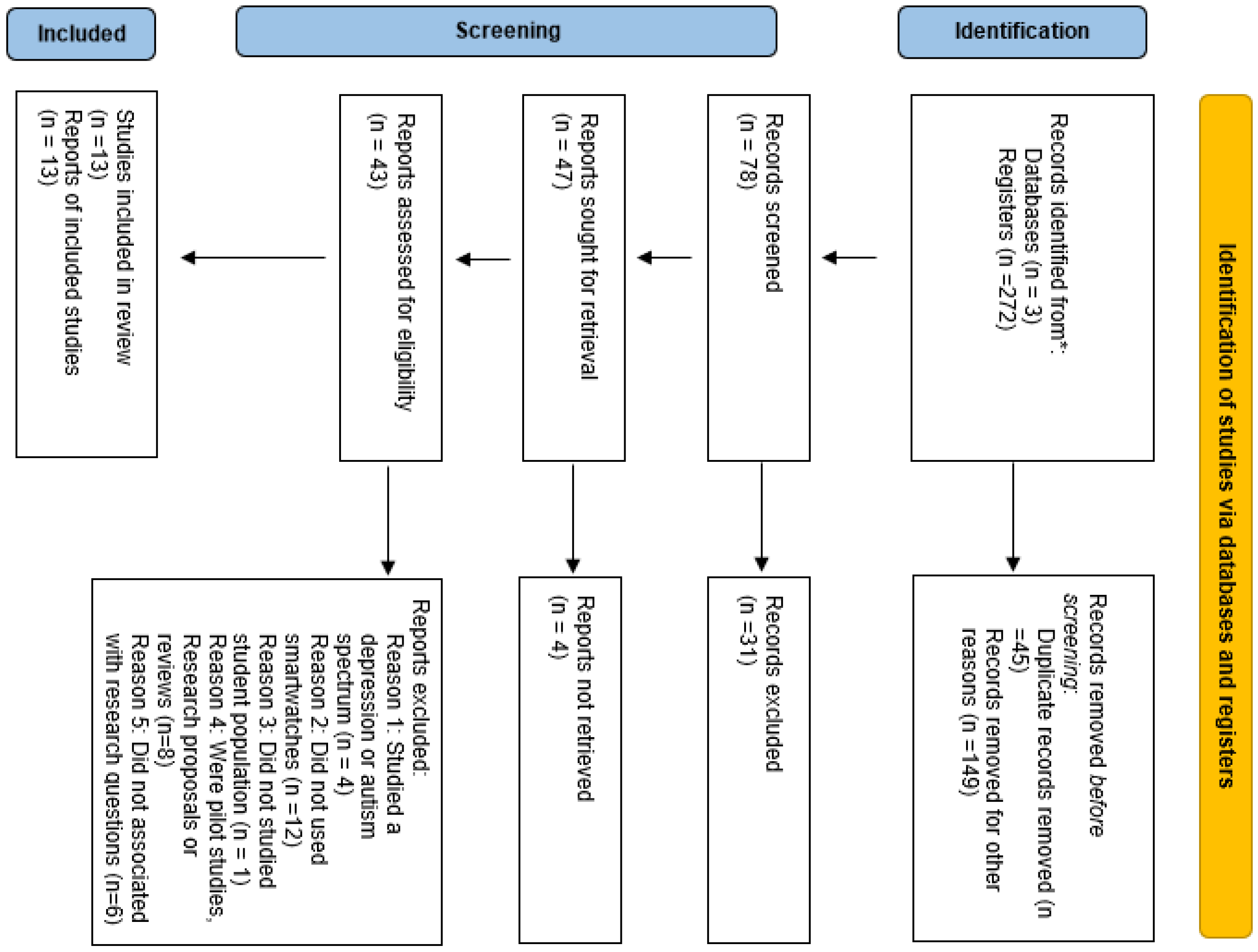

Figure 1 presents the steps of the reviewing progress. Firstly, it is identified the purposes and the specific research questions of present SLR which have been motivated this research. As follows, many digital databases were recruited with predetermined searching terms. Then, a primary selection of papers was performed and initial database inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. The final dataset of studies and records were coded and coincided with information associated with RQs. In the final step, the extracted information was organized, compared and discussed in order to achieve the research questions. Zotero 7 for windows[

32], an open-access reference management tool was used to extract the duplicate papers, for citation tracking and sources synthesizing.

3.1. Inclusion and Exlusion Criteria

Following the PRISMA process, it is intended to assess the effectiveness of wearable devices in burnout prediction. Resulting this, it was utilizing studies that uses smartwatches or any other wrist band technology for data collection. Also, studies that included in this literature review were those that conducted in student population. The minimum range of age was defined as 6 years old and the maximum 28 years old. Also, the type of studies that included were pilot studies, randomized control trials, and experimental studies.

The exclusion criteria were determined for studies that conducted in adult population without the student identity and clinical populations. Moreover, studies associated with participants with any other mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis they were not excluded from this review. Also, was extracted the studies that were conducted in population with autism spectrum and any other learning disorder. As the primary goal of this SLR is to focus in the effectiveness of wearable devices, so, it was excluded studies using other wearable digital sensors. The publication data of research papers was defined in 10 years. Review papers were, also, excluded.

Table 1.

Reasons for excluded studies from present systematic review.

Table 1.

Reasons for excluded studies from present systematic review.

| Excluded Reasons |

Retrieved Studies |

| R1. Studied a mental disorder, eg. Depression, autism spectrum etc. |

[33,34,35,36] |

| R2. Did not used smartwatches |

[34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

| R3. Did not studied student population |

[48] |

| R4. Were pilot studies, research proposals or reviews |

[49,50,51,53,54,55,56] |

| R5. Did not associated with research questions |

[48,57,58,59,60,61] |

3.2 Searching Strategies

Three databases were recruited, totally: Pubmed, Scopus and Web of Science. A series of keywords such as “burnout”, “stress”, “wearable devices”, “smart watches”, “students”, were identified and formed as queries using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. Below, follows the search queries: for Pubmed database, ((burnout) OR (stress)) AND (wearable devices) or (smart watches), (anxiety)) AND (wearable devices) OR (smart watches), for Scopus database, (burnout) OR (stress) AND (wearable) AND (devices) AND (students) and for Web of Science database, ((TS=(wearable devices)) AND TS=(burnout OR stress)) AND TS=(students). Then, the obtained inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. After that, the metadata of retrieved studies, particularly, titles and abstracts were reviewed occurring for adequacy in research questions.

3.3. Open Data Repositories

Nowadays, there is a crucial need to support open science and data-driven healthcare innovations. As a consequence, public health related databases play a crucial role in advancing scientific research, offering diverse data ranking from a variety of physiological signals to social health determinants[

17]. There are many challenges emerged including access restriction and data standardization. Nevertheless, the increasingly number of open-access health related repositories has transformed scientific research, undoubtedly[

18]. These data warehouses offer researchers the opportunity to explore various aspects of healthcare sector[

19] by heath data mining. In current SLR, Kang et al. 2023, [

73] provides all the research data available in Zenodo data warehouse for future research utilization and management. Above, there is a pivot table of the most prominent public repositories based on their primary goal of health research.

Table 2.

Public datasets for health data mining.

Table 2.

Public datasets for health data mining.

| Public Databases |

Overview |

Reference |

| Zenodo |

Open-access repository developed by CERN for all research disciplines, including health and biomedical sciences. It provides broad interdisciplinary coverage, DOI assignment and integration with GitHub, |

[20] |

| Figshare |

Digital repository for research sharing outputs, datasets, figures and presentations. It provides user-friendly interface, high visibility and metadata support. |

[21] |

| Dryad |

Open repository for life science and medical research, primary for datasets underlying publications. It provides peer-revied datasets, integration with journal submissions. |

[22] |

| Open Science Framework |

Collaborative platform for sharing and managing research data, including mental health and epidemiology studies. It has strong version control and project management tools. |

[23] |

| PhysioNet |

Provides access to biomedical datasets, including physiological signals, such as ECG or EEG. It affords high-quality curated datasets, widely used in clinical and machine learning research. |

[24] |

| Dataverse |

Open-source repository developed by Harvard University, hosting various datasets, including public health data. There are a well-structured metadata and institutional support. |

[25] |

| OpenNeuro |

Public repository for neuroimaging datasets, including fMRI, EEG and MEG. Provides standardized format, integration with neuroimaging software. It is focused on neuroimaging data. |

[26] |

| European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) |

European initiative for research data, including biomedical datasets. |

[27] |

| Kaggle |

Online platform that hosts datasets, notebooks, and machine learning competitions, including health-related datasets. It is a large community with the strong support for data science and AI applications.

|

[28] |

4. Results

After a primary literature search, a total amount of 272 studies were gathered. Three scientific databases were recruited. In this initial search, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. The remained records were screened on their title and their abstract and studies which were found that did not meet all the study requirements were removed. Also, the duplicable records were removed using the Zotero software tool. 43 reports were accessed for eligibility and a total number of 31 records were excluded because they did not require to the review purposes. Finally, 13 studies were included in the present SLR. The majority of the papers were reported in journal articles and only one was published in conference proceedings. Two of these papers (15%) were published in International Journal of Artificial Intelligence and the remaining papers were published in Journal of Medical Internet Research, JMIR mHealth uHealth, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Scientific Data, Diagnostics, BMC Psychiatry, Achieves of Design Research, Sensors and Plos ONE. Furthermore, one paper was published in 2018 as the same for the years 2019 and 2021, followed by two papers (15%) in 2020, 2023 (15%) and 2024 (15%) respectively. Three (23%) of the reviewed papers were published in 2022. Above, follow the results according to the defined research questions.

4.1. Purposes, Subjects and Behavioral Patterns

Researchers have focused on various purposes for studying burnout symptoms and related behavioral patterns. The reviewed papers were summarized into four categories, depending on their research purposes: (a) the purpose of the study was to predict a mental disorder associated with burnout symptoms, (b) the purpose of the study was to assess the efficacy of a technological innovation, (c) the purpose was to detect burnout symptoms using an AI wearable application, and (d) the purpose was to manage a mental disorder using an AI smart device. In

Table 3, are presented the summarized categories.

In more detail, five studies (38%) were focused in one of the main objectives which is the prediction of stress levels using advanced AI technologies. Specifically, the use of deep learning machines has proven effective in predicting stress levels [

62]. Additionally, the prediction of mental stress, as well as general mental well-being, depression, anxiety, and stress, has been extensively studied [

63,

64]. Research has, also, focused on the predictive utility of pretreatment heart rate variability (HRV) in the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (GCBT) in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety [

65]. Lastly, the prediction of stress when individuals are exposed to an acute stressor has also been examined [

66].

Another important area of study is assessing the efficacy of specific interventions. Such a study was investigated the effectiveness of the Biobase application in managing anxiety and stress, with results showing positive effects [

67]. Researchers have also focused on stress levels detection in various contexts. They have studied stress levels using different methods and tools [

68,

69], as well as ecological stress resulted by everyday life [

70]. Furthermore, fatigue detection and the response to psychological stress in everyday life have been explored [

71,

72]. Finally, stress management is a key area of interest. A research study has examined the management of attention as a means of reducing stress [

73], as well as stress management through interventions using smart devices and cognitive processes [

74], has been advocated new guidelines that can be promising in future in improvement of quality of life.

4.2. Wearable Devices, AI Technology and AI Predictive Models

Table 3 presents the number of reviewed studies using each wearable device to examine each related mental symptom. The devices are grouped by which symptom is measured. Fitbit Versa 2 (Fitbit) ais extensively used by the most studies (46%) and measure anxiety, depression and four of them stress. Empatica E4 wristband have been used from the 23% of the studies, from which two of them assesses stress level and one fatigue. Follows Biobeam which is used by two research studies for anxiety and stress detection, Apple watch for stress and attention, Huawei Band 6 using photoplethysmography sensors using from two research studies explored stress and depression. Finally, one study used Microsoft Band 2 to underline stress levels of the participants. It is resulted, that stress is a core element of burnout and the majority (76,9%) of the reviewed studies have been utilized a variety of smart wrist devices for tracking. Moreover, 61.5% of the reviewed studied have been utilized AI supportive technology to intergrate the biomarkers database, Biopac MP150, OpenBCI helmet, K-Emo EPOC Headset, NetHealth dataset, MacBook, iPad, iPhone, 3-lead ECG and Fitbit API. Furthermore, four studies (30%), have been developed or use an already existing AI predictive models.

Table 3.

Numbers of research studies, AI smart device and measuring symptoms.

Table 3.

Numbers of research studies, AI smart device and measuring symptoms.

| |

Empatica E4 wristband |

Microsoft Band 2 |

Fitbit Versa 2/Fitbit |

BioBeam |

Smart wrist band(not specify) |

Huawei Band 6 with photoplethysmography sensors |

Apple watch |

| Anxiety |

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

| Depression |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

| Stress |

2 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

|

1 |

| Fatigue |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Attention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

4.3. Measuring Mental Disorders Using Physiological Signals, Mental Scales and AI Predictive Models

Many studies have explored the possibility of using various physiological signals to assess the presence of mental disorders. Some examples from that are electrocardiogram (ECG), electroencephalogram (EEG), galvanic skin temperature (GSR) and respiration. On the other hand, heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) seems to be the most common used in research studies[

42]. HRV depicts the increases and decreases between consecutive heartbeat intervals, reflecting the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system and the status of cardiovascular system. Taking into account all the above, measuring these biomarkers is formed the general cardiac activity which leads to identification of multiple stress levels, depression detection and burnout symptoms generally. Based on the above, wearable devices using a variety of sensors collect data to detect and approach the mental status of healthy or diseased population.

On the other hand, the most common methods, according to bibliography, for assessing mental status are based on self-reported scales, some of those including Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the Stress Response Inventory (SRI), and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for mental stress detecting as well as the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), the Beck Depression Inventory Scale (BDI), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V).

In

Figure 2, are represented data from the 13 reviewed research papers, showing association between physiological signal and burnout symptom detection, verified by a measure scale respectively. Results shows that stress is the most frequently measured mental status, spanning with all the physiological signals. 38,5% of the reviewed papers have been used HR for stress detection, 23% have been used HRV and they are ranked ecological momentary assessments (EMA) or ecological physiological assessments (EPA), ST and EDA in percentage 15%, respectively. Moreover, data related to activity patterns, like rest time, sleep, motion acceleration, steps and total physical activity (indoor and outdoor) where measured. 30% of the reviewed papers focused on the relaxation and rest phases, also, 30% incorporated time of walking acceleration and total steps used to calculate the activity level as an indicator of overall movement. Physical activity is estimated as an indicator in studies focused on stress assessment. 30,7 % of the reviewed studies were focused on behavioral traits like openness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, lifestyle, self-characteristics, feelings of arousal. Finally, behavioral patterns like event stress, emotion and attention were obtained incorporating into the applied accessing methods. From total studies, two of them (15%) have been used self-reported scales for stress verification, the same as anxiety. HRV has been used from depression assessment by one (7,6%) research study but two (15%) studies have been used self-reported scales. Finally, mental fatigue is, mostly, detected through HRV, HR, skin temperature (ST), ECG and EDA and it is mentioned by one (7,6%) reviewed study. In

Figure 2, also, it is further depicted that four (30,7%) research studies have been used additionally artificial predictive models to support stress detection, in combination with biomarkers values and self-reported scales.

4.4. Challenges and Limitations in the Reviewed Studies

Wearable biosensors are characterized by some challenges related to data reliability in real-world conditions. Some reviewed papers have mentioned that physiological data can be noisy, especially in non-laboratory settings. The need to despike and filter the data to reduce noise raises the concern of data manipulation and must be taken into account the integrity of the original signals [

70]. Also, wearable devices can be malfunctioned or participants may not follow the instructions properly, leading to low-quality of data. In the K-EmoPhone study, some participants provided faulty data due to device errors or failure to adhere to instructions, in consequence to dataset quality [

73]. Also, in the study of Cagnon et al, 2022, it is mentioned the variability in accuracy, especially during high-intensity activities or in stress conditions, as a significant challenge in reliability of wearables for precise stress monitoring. Sensor accuracy in achieving reliable and valid data, particularly in naturalistic settings is a core limitation of wearable technology [

68,

71].

Tutunji et al, 2023 has mentioned the challenge of result generalizability. Physiological responses vary widely between individuals and the development of algorithms that work across diverse populations will remain a difficult task. Considerations of this variability must be addressed by ensuring that AI models are personalized to avoid false positives or negatives, which could lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate interventions. Also, data variability can be caused from the different participants that are influenced by individuals’ differences. One method to address this is adjusting the threshold for each participant when analyzing subjective data such as self-reported stress or emotion [

73]. Individual variability as a challenge highlights the ethical concern of fairness in data interpretation. In one study, using machine learning models, the ego-centric data was a key predictor, suggesting that more personalized models could achieve higher accuracy. However, this reliance on personalization raises ethical concerns about overfitting to individual characteristics, which may result in biased outcomes[

64].

Some of the reviewed studies discussed limitations due to class imbalances (like the proportion of fatigue versus non-fatigue states) and small sample sizes. This is an ethical challenge since it may lead to biased or non-generalizable results. Increasing sample sizes and ensuring a balanced representation of various states (such as stress and non-stress conditions) are essential to improve the statistical validity of the results [

70]. Moreover, a small sample size in two of the reviewed studies may affect also the generalization of results and it is noted the demand of further larger studies[

68,

71].

A major challenge that is mentioned in two of the reviewed studies is participant compliance wearing a device and research dropout. Non-compliance can lead to skewed results, and participants with higher stress or mental health symptoms are more likely to drop out, leading to potential bias in outcomes [

65,

68].

Health risks and mental well-being of participants is another major issue that reviewed research studies have mentioned and must be handled due to the fact that participants have to face distress or anxiety caused by the continuing monitoring or because some of them become overly concerned about their health data. Thus, psychological impact of such studies must be considered [

73]. Also, recalling stressful events, such as in Pakhomov et al, 2023 study, or participating in conditions that may induce stress such as exams or arithmetic tasks, can cause excessive distress to participants

4.5. Ethical Considerations that Participants Had to Jandle During the Usage of Wearable AI Technology

All of the reviewed papers were complied in ethical considerations that are required obtaining an informed consent for research participation and health-related data handling. The participants were aware of the studies’ aims, procedures and potential risks that have been involved in researches related in mental health issues. Ethical clearance was obtained from regional review boards, ensuring that all the procedures of institutional and national or international ethical standards, such as Helsinki Declaration, were adhered.

Some of the reviewed papers highlight the need to safeguard participants’ privacy which is related to sensitive physiological data like heart rate, skin conductance, stress levels etc[

68,

70]. Protecting privacy is a significant ethical concern which is ensured through data anonymization, identification and informed consent. In the K-EmoPhone study, anonymity of sensitive data are ensured via encryption while GPS is used and due to the addition of noise [

73]. Similarly, in the NetHealth study, due to privacy concerns, some of the participants’ data are not shared publicly [

64].

4.6. Performance and Accuracy of the Surveyed Systems

Evaluating the accuracy and performance of applications used for physiological and psychological assessments is crucial for ensuring reliable outcomes. Various statistical and machine learning techniques have been employed to measure error rates, assess model generalizability, and identify the best predictive features for mental fatigue and other physiological states.

4.6.1. Statistical and Analytical Techniques

Oweis et al. evaluate application accuracy, using One-Way ANOVA and data analytics were employed [

69]. Analysis [

68] of the measurement error between the Biopac system and the Fitbit Versa 2 revealed a mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.87 (SD 6.57, 95% CI 3.57-8.16) beats per minute (bpm). This value is below the predefined clinically acceptable difference (CAD) of ±10 bpm, demonstrating good accuracy of the Fitbit Versa 2 in heart rate monitoring.

Correlations to self-reported mental fatigue levels were used by Ramírez-Moreno, M. et al. to calculate the best mental fatigue predictors. Three-class mental fatigue models were evaluated, and the best model obtained an accuracy of 88% using three features, β/θ (C3), and the α/θ (O2 and C3) ratios, from one minute of electroencephalography measurements [

72].

In the study of Lin et al., was aimed to predict the efficacy of Group Cognitive Behavior (GCBT) for depression and anxiety using heart rate variability though collected data via smart wearable devices. The accuracy and performance of proposed models were evaluated using statistical analysis, such as repeated measures ANOWA (RANOWA), Spearmans’ rank correlations, multiple linear regression. The best predictive model for depression achieved R2 =0.936 (p=0.02), indicating strong predictive accuracy. The best predictive model for anxiety achieved R2 =0.954 (p=0.002), demonstrating even stronger predictive performance.

Statistical analysis, using paired t-test, Holm-Bonferroni correction and Pearsons’ correlations, of collected data was used, also, by Chalmers et al. for accuracy and performance evaluation of a physiological algorithm for stress detection integrated into wearable technologies. The study demonstrated that HRV featured can predict stress responses, but the model’s accuracy depends on baseline stress levels and individual differences. Results suggested that future smartwatch-based stress detection algorithms should account for personal baseline states to improve prediction accuracy [

66].

Ponzo et al., was evaluate the BioBase mobile app and BioBeam wearable device in their efficacy to reduce stress and anxiety among university students. The collected data, both from physical biomarkers and psychometrics, were evaluated using Linear Mixed Models (LMMs), paired-sample t-tests and effect size analysis (Cohen’s d). Significance reduction in anxiety and depression were found after 4 weeks in the intervention group, sustained effects at 6-weeks follow-up and no correlation between app engagement and outcome measures, suggesting effect was not solely driven by user interaction [

67]. The same suggested model was proposed, also, by Pakhomov et al. to investigate whether Fitbit fitness trackers can detect physiological responses to psychosocial stress in everyday life. After model evaluation using the appropriate statistical controls, it is concluded that the Fitbit is able effectively to detect stress-included HR changed, supporting its use in real-world stress monitoring [

71].

4.6.2. Machine Learning Approaches

Various machine learning models, including random forest models, were applied to enhance accuracy in predicting physiological states. Detecting ecologically relevant stress states[

70] the robustness of used models where tested. Different cross-validation techniques such as the Leave-One-Beep-Out (LOBO) and Leave-One-Trial-Out (LOTO) methods were used against a bootstrap error distribution. The performance of the LOBO models was compared to that of the Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) method to determine the generalizability of machine learning models. Results indicated that all models performed significantly above chance at the individual level for all but one participant.

In Kang et al. proposed models’, performances for predicting valence, arousal, stress, and task were disturbance across different learning algorithms and oversampling usages. Overall, the performance of these prediction models surpassed that of the baseline model accuracy. Random Forest and XGBoost models were trained to classify states of valence, arousal, stress and task disturbance in high and low categories. Model performance was evaluated using Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) cross-validatrion ensuring that predictions generalized to unseen participants. performed better than the baseline and Random Forest, except for predicting arousal[

73]. The study demonstrates that multimodal data from smartphones and wearables can predict real-world emotional and cognitive states with reasonable accuracy.

Data Completion with Diurnal Regularizers (DCDR) and Temporally Hierarchical Attention (THAN)are proposed by Jiang et al. to deal with the data sparsity and precisely predict human stress level. It presented that diurnal behavioral patterns can significantly benefit missing data recovery while user behaviors can be more effectively captured by exploiting temporally hierarchical structures of sensor data. After the appropriate parameter sensitivity analysis to demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of proposed approach, it is concluded that the model does not require to train data for satisfactory prediction performance, also, parameter tuning is required to reach the best performance for both DCDR and THAN in sensor data completion and stress level prediction[

62].

In research work of Chandra & Sethia [

63] two machine learning classifiers are implemented, Random Forest and k-nearest neighbors, using the scikit-learn module of Python 3 on local computers. These proposed models classified stress into three levels: rest, moderate, and high. They achieved a classification accuracy of 99.98% using the EEG signals’ time-frequency domain features and an accuracy of 99.51% using the EDA, HR, and ST signals.

Overall, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) mood models exhibited superior performance in Tutunji et al. 2023, physiology-based models classified beeps with an accuracy difference of only 3.85% compared to mood models. Combination models, integrating multiple data sources, yielded the highest accuracy.

Deep learning methodology and conventional prediction algorithms are proposed by Saylam & Incel, 2024. The updated analysis for mental health multitask[

64] resulted that the baseline of Multitask Learning (MTL) performances align closely, with no significant improvement observed in the multitask scenario. RF and XGBoost results exhibit minimal differences, and substantial performance enhancements are achieved by incorporating the temporal aspect.

4.7. Results and Main Findings of Each Survey

Various studies have explored the accuracy and effectiveness of wearable devices, machine learning models, and statistical methods in monitoring physiological and psychological states. Oweis et al. (2018) used One-Way ANOVA and data analytics to evaluate application accuracy for Galvaric Skin Response (GSR) of students under pre-set conditions over a whole semester, using a wearable smartwatch. Findings of this work show significant correlations between GSR values and activity level, results that have been confirmed in future work, because, this is the first study if its kind. Similarly, Gagnon et al. (2022) assessed the measurement error of the Fitbit Versa 2 compared to the Biopac system, finding a mean absolute error of 5.87 bpm—well within the clinically acceptable difference, indicating good heart rate monitoring accuracy. These results support the use of Fitbit Versa 2 in capturing short-term stress variations. Although, Fitbit device presents acceptance levels of accuracy in HR measurement for stress recording, there is a poor agreement with the ECG gold standard, so Fitbit cannot replace ECG instruments when precision is utmost importance.

The reviewed studies indicate that machine learning models played a crucial role in mental fatigue and stress detection. Furthermore, Ramírez-Moreno et al. (2021) employed EEG-based features to develop three-class mental fatigue models, achieving an 88% accuracy in prediction. This pilot study demonstrates the viability and potential of short-calibration procedures and inter-subject classifiers in mental fatigue modeling. These results will support the use of wearable devices in developing tools aimed at enhancing the well-being of workers and students, as well as improving daily life activities. Lin et al. investigated the use of smart wearables in predicting the efficacy of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (GCBT) for depression and anxiety, with predictive models achieving strong accuracy (R² = 0.936 for depression and R² = 0.954 for anxiety). Consequently, findings of this study show that HRV may be useful predictor of GCBT treatment efficacy and by identifying predictors of treatment response can help in treatment personalization improving outcomes for individuals with depression and anxiety.

Chalmers et al. (2022) used statistical methods such as paired t-tests, Holm-Bonferroni correction, and Pearson’s correlations to validate a physiological algorithm for stress detection in wearable technology. The findings emphasized that HRV-based stress detection, with data collected wearing smart watches, depends on baseline stress levels and individual differences, suggesting future models should incorporate personal baseline states for improved accuracy.

Moreover, Ponzo et al. (2020) evaluated the BioBase mobile app and BioBeam wearable, confirming significant reductions in anxiety and depression after four weeks, with sustained effects at six weeks. Results of this study demonstrates the effectiveness of digital intervention in lowering self-reported anxiety and enhancing perceived well-being among Uk university students. The findings indicate that digital mental health interventions could offer an innovative approach to managing stress and anxiety in students, either as a standalone solution or in combination with existing therapeutic methods. Similarly, Pakhomov et al. (2020) confirmed Fitbit’s capability to detect physiological responses to stress in real-life settings. These findings align with previous laboratory research and suggest that consumer wearable fitness trackers could be a valuable tool for monitoring exposure to psychological stressors in real – world settings.

Machine learning techniques further enhanced physiological state predictions. Tutunji et al. (2023) applied various models, including random forests, testing their robustness using cross-validation techniques like Leave-One-Beep-Out (LOBO) and Leave-One-Trial-Out (LOTO). Results demonstrated that all models performed significantly above chance for nearly all participants. Kang et al. (2023) utilized multimodal data from smartphones and wearables, applying Random Forest and XGBoost models for predicting valence, arousal, stress, and task disturbances, outperforming baseline accuracy in most cases. These studies highlight the potential of wearable biosensors for monitoring stress-related mantal health. They emphasize the importance of psychological content in interpreting psychological arousal, as such responses can be linked to both positive and negative experiences. Additionally, the findings support a personalized approach, suggesting that stress is most accurately detected when compared to an individual’s own baseline data.

Jiang et al. (2019) proposed Data Completion with Diurnal Regularizers (DCDR) and Temporally Hierarchical Attention (THAN) to predict human stress levels despite data sparsity. Their findings highlighted the importance of diurnal behavioral patterns in missing data recovery. Chandra & Sethia (2024) implemented machine learning classifiers (Random Forest and k-nearest neighbors) for stress classification, achieving near-perfect accuracy (99.98% using EEG signals and 99.51% using EDA, HR, and SKT signals). The proposed machine models outperform all previous studies on stress classification using EEG, EDA, HR and SKT signals. This study is particularly innovative as demonstrates the effectiveness of wearable devices in developing accurate stress classification models, paving the way for real-time stress monitoring systems, conclusion that linked to the analysis results of Jiang et al. (2019) which show the robustness and effectiveness of proposed machine models. Meanwhile, Saylam & Incel (2024) compared deep learning and conventional prediction algorithms in a mental health multitask scenario, concluding that while multitask learning did not significantly outperform single-task models, incorporating temporal aspects substantially improved results.

Overall, ecological momentary assessment (EMA)-based mood models exhibited superior performance of Tutunji et al., (2023), while physiology-based models had only a slight accuracy gap (3.85%). Combining multiple data sources yielded the highest accuracy, emphasizing the potential of multimodal approaches in real-world psychological and physiological state monitoring.

5. Discussion

Findings of this systematic literature review highlight the increasing role of wearable AI technology, particularly smartwatches, in detecting and managing burnout symptoms among students. The reviewed studies emphasize the importance of physiological monitoring, AI-driven predictive models, and self-reported scales in assessing mental well-being. However, despite the promising potential of these technologies, several challenges and limitations must be addressed to enhance their effectiveness and reliability. This review mentions that stress is the most frequently studied burnout-related symptom, with heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) being the most commonly used biomarkers. Moreover, the consistent use of these physiological signals suggests their viability as indicators of stress and mental fatigue [

76]. Research focused on physical and mental monitoring encouraging supportive educational settings [

76].

However, the variability in sensor accuracy and the influence of individual physiological differences pose significant concerns. Wearable biosensors often encounter issues with noise and inconsistencies, particularly in non-controlled environments, raising concerns about data integrity and the risk of false positives or negatives. Future research should focus on improving data processing techniques and integrating multimodal sensor data to enhance reliability. Many research projects are very promising in this era [

77], improving both working places and mental health of individuals.

Another notable finding is the role of AI in supporting burnout detection [

78]. Several studies have leveraged machine learning algorithms to predict stress levels, focused in user attraction, reducing users’ dropouts from health monitoring[

19], yet the generalizability of these models remains limited due to small sample sizes and class imbalances. Personalized AI models have demonstrated potential in improving accuracy; however, they also introduce ethical concerns related to data privacy and fairness. Addressing these issues requires the development of standardized AI frameworks that ensure equitable and unbiased outcomes across diverse populations [

79].

The review also underscores the significance of self-reported mental health assessments, which are frequently used alongside physiological data for validation. Instruments such as the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) remain widely utilized, reinforcing the need for a hybrid approach that combines subjective self-assessments with objective physiological measurements. However, reliance on self-reported data introduces biases related to participants’ perceptions and reporting tendencies, which could impact the overall validity of results.

Ethical considerations remain a crucial aspect of wearable AI applications in mental health monitoring. Ensuring data security, participant privacy, and informed consent are paramount, given the sensitive nature of mental health data. Several studies highlight the importance of encryption and anonymization strategies to protect participant information. Additionally, ethical concerns due to continuous monitoring of physiological data are related to user privacy, data security and informed consent [

66]. Also, some users may feel discomfort with the level of surveillance involved in such monitoring. Future steps must incorporate privacy machine learning techniques, such as federated learning, where data remains on user’s device rather than being transferred to external servers [

41]. Ethical compliance must be ensured by transparent data government policies and user consent protocols.

Another major limitation is the variability in individual physiological responses to stress. Stress perception and physiological reactions differ widely across individuals due to genetic, behavioral and contextual factors [

41]. Current machine learning models are trained to manage data from wide population often fail to adapt to personal baseline differences, as a consequence reducing the predictive accuracy [

75]. Future approaches should incorporate personalized modeling techniques capable to adjust to individual’s patterns.

Moreover, reviewed studies utilize diverse methodologies, as a result findings are difficult to compare and validate across different datasets. Researchers adopt various statistical techniques, including Linear Mixed Methods (LMMs), ANOVA and machine learning classifiers RF and XGBoost, each with district assumptions and limitations [

67]. The absence of standardized evaluation frameworks results in inconsistent conclusions. To move forward, researchers must establish uniform validation criteria, standardized datasets and benchmarking protocols for stress detection and mental health prediction models.

Despite these challenges, wearable AI technology offers a promising, non-invasive means of identifying early signs of burnout in student populations. Future perspectives should prioritize the development of personalized, multimodal and real-world adaptive systems. To achieve this, researchers must adjust AI models in sensor accuracy, develop adaptive machine learning models, standardize validation methods and enhance the applicability and reliability of findings. Research of Koulouris et al. promote the utilization of gamification techniques to boost the users’ physical activities [

80]. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between mental health professionals, AI researchers, and wearable technology developers is essential to ensure that these tools are effectively integrated into academic and clinical settings.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, while wearable AI devices present a transformative approach to burnout detection and stress management, their implementation must be accompanied by rigorous validation, ethical safeguards, and continuous refinement to maximize their potential benefits.

This systematic literature review underscores the potential of wearable AI devices in the early detection and management of burnout symptoms among students. The integration of physiological monitoring, AI predictive models, and self-reported assessments presents a comprehensive approach to understanding mental health trends in academic settings. However, several limitations, including sensor accuracy, data reliability, ethical considerations, and model generalizability, must be addressed to optimize the effectiveness of these technologies.

While existing studies have focused on stress detection in students remains a lack of research on whether burnout symptoms are capable to be detected during academic studies or not. Building upon prior research, we proposed a research approach to burnout detection by integrating wearables devices in collaboration of complex data using a Large Language Model (LLM). In particular, we designed a research methodology that is supposed to track various metrics that influence a student's academic performance and well-being. It includes both academic data, such as course teaching and lab hours, and physiological data, such as HRV, heart rate, and stress levels, gathered over a seven-day moving average. This model also captures the student’s academic performance, their workload (including extracurricular activities and deadlines), and personalized learning interventions. By tracking these attributes, it can be monitored students’ stress levels, identifying workload imbalances, and making necessary adjustments to help students manage their academic responsibilities.

Moving forward, future studies should focus on refining AI algorithms, enhancing wearable sensor capabilities, and ensuring ethical safeguards for data privacy and participant well-being. Collaborative efforts among researchers, healthcare professionals, and technology developers are crucial in advancing the application of AI-driven wearable devices in mental health monitoring. By overcoming current challenges, wearable AI technology can become a vital tool in promoting student well-being and preventing long-term mental health consequences associated with burnout.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, P.L. and I.M.; methodology, P.L; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, P.L.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, I.M.; visualization, I.M.; supervision, I.M.; project administration, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| HR |

Heart Rate |

| HRV |

Heart Rate Variability |

| EDA |

Electrodermal Activity |

| EMA |

Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| EPA |

Ecological Physiological Assessment |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| ST |

Skin Temperature |

| CGBT |

Cognitive Behavior Therapy |

| GST |

Galvanic Skin Temperature |

| PSS |

Perceived Stress Scale |

| SRI |

Stress Response Inventory |

| STAI |

State Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| HAMD |

Hamilton Depression Scale |

| BDI |

Beck Depression Inventory Scale |

| DSM-IV |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| LMMs |

Linear Mixed Methods |

| LOBO |

Leave-One-Beep-Out |

| LOSO |

Leave-One-Subject-Out |

| LOTO |

Leave-One-Trial-Out |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| DCDR |

Data Completion Diurnal Regularizes |

| THAN |

Temporally Hierarchical Attention |

| MTL |

Multitask Learning |

References

- WHO | Basic documents [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 29]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/.

- Burnout and Engagement in University Students: A Cross-National Study - Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Isabel M. Martínez, Alexandra Marques Pinto, Marisa Salanova, Arnold B. Bakker, 2002 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 29]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022022102033005003. [CrossRef]

- Almeida T, Kadhum M, Farrell SM, Ventriglio A, Molodynski A. A descriptive study of mental health and wellbeing among medical students in Portugal. International Review of Psychiatry. 2019 Nov 17;31(7–8):574–8. [CrossRef]

- Di Mario S, Rollo E, Gabellini S, Filomeno L. How Stress and Burnout Impact the Quality of Life Amongst Healthcare Students: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Teaching and Learning in Nursing [Internet]. 2024 May 11 [cited 2024 Jun 22]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1557308724000842. [CrossRef]

- Silva E, Aguiar J, Reis LP, Sá JOE, Gonçalves J, Carvalho V. Stress among Portuguese Medical Students: the EuStress Solution. J Med Syst. 2020 Jan 2;44(2):45. [CrossRef]

- Gabola P, Meylan N, Hascoët M, De Stasio S, Fiorilli C. Adolescents’ School Burnout: A Comparative Study between Italy and Switzerland. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2021 Aug 11;11(3):849–59. [CrossRef]

- Treluyer L, Tourneux P. Burnout among paediatric residents during the COVID-19 outbreak in France. Eur J Pediatr. 2021 Feb;180(2):627–33. [CrossRef]

- Beck MS, Fjorback LO, Juul L. Associations between mental health and sociodemographic characteristics among schoolchildren. A cross-sectional survey in Denmark 2019. Scand J Public Health. 2022 Jun;50(4):463–70. [CrossRef]

- Govorova E, Benítez I, Muñiz J. How Schools Affect Student Well-Being: A Cross-Cultural Approach in 35 OECD Countries. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Mar 25 [cited 2024 Aug 29];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00431/full. [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli C, De Stasio S, Di Chiacchio C, Pepe A, Salmela-Aro K. School burnout, depressive symptoms and engagement: Their combined effect on student achievement. International Journal of Educational Research. 2017 Jan 1;84:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Zhang R, Wang H, Rule A, Wang M, Abbey C, et al. Association between anxiety, depression symptoms, and academic burnout among Chinese students: the mediating role of resilience and self-efficacy. BMC Psychol. 2024 Jun 7;12(1):335. [CrossRef]

- Al-Awad, FA. Academic Burnout, Stress, and the Role of Resilience in a Sample of Saudi Arabian Medical Students. Med Arch. 2024;78(1):39–43. [CrossRef]

- Chirkowska-Smolak T, Piorunek M, Górecki T, Garbacik Ż, Drabik-Podgórna V, Kławsiuć-Zduńczyk A. Academic Burnout of Polish Students: A Latent Profile Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 9;20(6):4828. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq A, Alajlani M, Ahmad R, AlSaad R, Aziz S, Ahmed A, et al. The Performance of Wearable AI in Detecting Stress Among Students: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Jan 31;26:e52622. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal AK, Gonzales R, Scott K, Merchant R. Investigating the Feasibility of Using a Wearable Device to Measure Physiologic Health Data in Emergency Nurses and Residents: Observational Cohort Study. JMIR Form Res. 2024 Feb 22;8:e51569. [CrossRef]

- Mason R, Godfrey A, Barry G, Stuart S. Wearables for running gait analysis: A study protocol. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(9 September). [CrossRef]

- Wack M, Coulet A, Burgun A, Rance B. Enhancing clinical data warehousing with provenance data to support longitudinal analyses and large file management: The gitOmmix approach for genomic and image data. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2025 Mar 1;163:104788. [CrossRef]

- Tang C, Ma J, Zhou L, Plasek J, He Y, Xiong Y, et al. Improving Research Patient Data Repositories From a Health Data Industry Viewpoint. J Med Internet Res. 2022 May 11;24(5):e32845. [CrossRef]

- Solberg LM, Duckworth LJ, Dunn EM, Dickinson T, Magoc T, Snigurska UA, et al. Use of a Data Repository to Identify Delirium as a Presenting Symptom of COVID-19 Infection in Hospitalized Adults: Cross-Sectional Cohort Pilot Study. JMIR Aging. 2023 Nov 30;6:e43185. [CrossRef]

- Zenodo | openscience.eu [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://openscience.eu/article/infrastructure/zenodo.

- Thelwall M, Kousha K. Figshare: a universal repository for academic resource sharing? Online Information Review. 2016 Jun 13;40(3):333–46. [CrossRef]

- Vision TJ. Open Data and the Social Contract of Scientific Publishing. BioScience. 2010 May 1;60(5):330–1. [CrossRef]

- Foster ED, Deardorff A. Open Science Framework (OSF). J Med Libr Assoc. 2017 Apr;105(2):203–6. [CrossRef]

- PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet | Circulation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215. [CrossRef]

- King, G. An Introduction to the Dataverse Network as an Infrastructure for Data Sharing. Sociological Methods & Research. 2007 Nov 1;36(2):173–99.e215. [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz CJ, Gorgolewski KJ, Feingold F, Blair R, Halchenko YO, Miller E, et al. The OpenNeuro resource for sharing of neuroscience data. Kahnt T, Baker CI, Dosenbach N, Hawrylycz MJ, Svoboda K, editors. eLife. 2021 Oct 18;10:e71774. [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). Turning FAIR into reality: final report and action plan from the European Commission expert group on FAIR data [Internet]. Publications Office of the European Union; 2018 [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/1524. [CrossRef]

- Kaggle: Your Machine Learning and Data Science Community [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021 Jan 26;10(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Amir-Behghadami M, Janati A. Reporting Systematic Review in Accordance With the PRISMA Statement Guidelines: An Emphasis on Methodological Quality. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Oct;15(5):544–5. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, DE. Zotero as a teaching tool for independent study courses, honors contracts, and undergraduate research mentoring. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2024 Aug 19;e0013224. [CrossRef]

- Islam TZ, Wu Liang P, Sweeney F, Pragner C, Thiagarajan JJ, Sharmin M, et al. College Life is Hard! - Shedding Light on Stress Prediction for Autistic College Students using Data-Driven Analysis. In: 2021 IEEE 45th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. p. 428–37. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9529720. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen J, Cardy RE, Anagnostou E, Brian J, Kushki A. Examining the effect of a wearable, anxiety detection technology on improving the awareness of anxiety signs in autism spectrum disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Mol Autism. 2021 Nov 14;12(1):72. [CrossRef]

- Van Laarhoven TR, Johnson JW, Andzik NR, Fernandes L, Ackerman M, Wheeler M, et al. Using Wearable Biosensor Technology in Behavioral Assessment for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Intellectual Disabilities Who Experience Anxiety. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2021 Jun;5(2):156–69. [CrossRef]

- Conderman G, Van Laarhoven T, Johnson J, Liberty L. Wearable technologies for students with disabilities. Support Learn. 2021 Nov;36(4):664–77. [CrossRef]

- Thammasan N, Stuldreher I, Schreuders E, Giletta M, Brouwer AM. A Usability Study of Physiological Measurement in School Using Wearable Sensors. Sensors. 2020 Sep;20(18):5380. [CrossRef]

- Lim KYT, Nguyen Thien MT, Nguyen Duc MA, Posada-Quintero HF. Application of DIY Electrodermal Activity Wristband in Detecting Stress and Affective Responses of Students. Bioengineering. 2024;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Harvey RH, Peper E, Mason L, Joy M. Effect of Posture Feedback Training on Health. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback. 2020;45(2):59–65. [CrossRef]

- Chiovato A, Demarzo M, Notargiacomo P. Evaluation of Mindfulness State for the Students Using a Wearable Measurement System. J Med Biol Eng. 2021 Oct;41(5):690–703. [CrossRef]

- Lin B, Prickett C, Woltering S. Feasibility of using a biofeedback device in mindfulness training-a pilot randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021 Mar 24;7(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Jiao Y, Wang X, Liu C, Du G, Zhao L, Dong H, et al. Feasibility study for detection of mental stress and depression using pulse rate variability metrics via various durations. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2023 Jan 1;79:104145. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan S, Duvvuru A, Kamarthi SV. Investigating Discrete Event Simulation Method to Assess the Effectiveness of Wearable Health Monitoring Devices. Procedia Economics and Finance. 2014 Jan 1;11:838–56. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Xu H, Yan M, Huang J, Yan W, Lan K, et al. Longitudinal Changes and Recovery in Heart Rate Variability of Young Healthy Subjects When Exposure to a Hypobaric Hypoxic Environment. Frontiers in Physiology. 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Pirbhulal S, Zhang H, Mukhopadhyay SC. Quantitative Assessment for Self-Tracking of Acute Stress Based on Triangulation Principle in a Wearable Sensor System. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2019;23(2):703–13. [CrossRef]

- Nelson BW, Harvie HMK, Jain B, Knight EL, Roos LE, Giuliano RJ. Smartphone Photoplethysmography Pulse Rate Covaries With Stress and Anxiety During a Digital Acute Social Stressor. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2023;85(7):577–84. [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska K, Doniec RJ, Sieciński S, Piaseczna NJ, Pachoński M, Tkacz EJ. The relationship between stress levels measured by a questionnaire and the data obtained by smart glasses and finger pulse oximeters among polish dental students. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 2021;11(18). [CrossRef]

- Abromavičius V, Serackis A, Katkevičius A, Kazlauskas M, Sledevic T. Prediction of exam scores using a multi-sensor approach for wearable exam stress dataset with uniform preprocessing. Technology and Health Care. 2023;31(6):2499–511. [CrossRef]

- Choi A, Ooi A, Lottridge D. Digital Phenotyping for Stress, Anxiety, and Mild Depression: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2024;12:e40689. [CrossRef]

- Odaka T, Misaki D. A PROPOSAL FOR THE STRESS ASSESSMENT OF ONLINE EDUCATION BASED ON THE USE OF A WEARABLE DEVICE. Journal of Research and Applications in Mechanical Engineering. 2021;9(2).

- de Arriba Perez F, Santos-Gago JM, Caeiro-Rodriguez M, Fernandez Iglesias MJ. Evaluation of Commercial-Off-The-Shelf Wrist Wearables to Estimate Stress on Students. J Vis Exp. 2018 Jun;(136):e57590. [CrossRef]

- Yunusova A, Lai J, Rivera AP, Hu S, Labbaf S, Rahmani AM, et al. Assessing the mental health of emerging adults through a mental health app: Protocol for a prospective pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2021;10(3). [CrossRef]

- de Arriba-Perez F, Caeiro-Rodrigues M, Manuel Santos-Gago J. Towards the use of commercial wrist wearables in education. In: PROCEEDINGS OF 2017 4TH EXPERIMENT@INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE (EXPAT’17) [Internet]. New York: IEEE; 2017 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. p. 323–8. (Experiment at International Conference). Available from: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000412842600081. [CrossRef]

- Johnson J, Conderman G, Van Laarhoven T, Liberty L. Wearable Technologies: A New Way to Address Student Anxiety. Kappa Delta Pi Record. 2022;58(3):124–9.

- Ba S, Hu X. Measuring emotions in education using wearable devices: A systematic review. Comput Educ. 2023 Jul;200:104797. [CrossRef]

- Price M, Hidalgo JE, Bird YM, Bloomfield LSP, Buck C, Cerutti J, et al. A large clinical trial to improve well-being during the transition to college using wearables: The lived experiences measured using rings study. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2023;133. [CrossRef]

- Takpor TO, Atayero AA. Integrating Internet of Things and EHealth Solutions for Students’ Healthcare. In: Ao SI, Gelman L, Hukins DWL, Hunter A, Korsunsky AM, editors. WORLD CONGRESS ON ENGINEERING, WCE 2015, VOL I [Internet]. Hong Kong: Int Assoc Engineers-Iaeng; 2015 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. p. 265–8. (Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science). Available from: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000380592400052.

- Trevor Bopp, Joshua D. Vadeboncoeur. “It makes me want to take more steps”: Racially and economically marginalized youth experiences with and perceptions of Fitbit Zips® in a sport-based youth development program [Internet]. Journal of Sport for Development. 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 30]. Available from: https://jsfd.org/2021/10/01/it-makes-me-want-to-take-more-steps-racially-and-economically-marginalized-youth-experiences-with-and-perceptions-of-fitbit-zips-in-a-sport-based-youth-development-program/.

- Shui X, Chen Y, Hu X, Wang F, Zhang D. Personality in Daily Life: Multi-Situational Physiological Signals Reflect Big-Five Personality Traits. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023 Jun;27(6):2853–63. [CrossRef]

- Yen, HY. Smart wearable devices as a psychological intervention for healthy lifestyle and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Qual Life Res. 2021 Mar 1;30(3):791–802. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Park Y, Lee J. The Validity of Heart Rate Variability (HRV) in Educational Research and a Synthesis of Recommendations. Educ Psychol Rev. 2024 Jun;36(2):42. [CrossRef]

- Jiang JY, Chao Z, Bertozzi AL, Wang W, Young SD, Needell D. Learning to Predict Human Stress Level with Incomplete Sensor Data from Wearable Devices. In: PROCEEDINGS OF THE 28TH ACM INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INFORMATION & KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT (CIKM ’19) [Internet]. New York: Assoc Computing Machinery; 2019 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. p. 2773–81. Available from: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000539898202144. [CrossRef]

- Chandra V, Sethia D. Machine learning-based stress classification system using wearable sensor devices. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence. 2024;13(1):337–47. [CrossRef]

- Saylam B, Incel OD. Multitask Learning for Mental Health: Depression, Anxiety, Stress (DAS) Using Wearables. Diagnostics. 2024 Mar;14(5):501. [CrossRef]

- Lin Z, Zheng J, Wang Y, Su Z, Zhu R, Liu R, et al. Prediction of the efficacy of group cognitive behavioral therapy using heart rate variability based smart wearable devices: a randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024 Mar 6;24(1):187. [CrossRef]

- Chalmers T, Hickey BA, Newton P, Lin CT, Sibbritt D, McLachlan CS, et al. Stress Watch: The Use of Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability to Detect Stress: A Pilot Study Using Smart Watch Wearables. Sensors. 2022 Jan;22(1):151. [CrossRef]

- Ponzo S, Morelli D, Kawadler JM, Hemmings NR, Bird G, Plans D. Efficacy of the Digital Therapeutic Mobile App BioBase to Reduce Stress and Improve Mental Well-Being Among University Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020 Apr 6;8(4):e17767. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon J, Khau M, Lavoie-Hudon L, Vachon F, Drapeau V, Tremblay S. Comparing a Fitbit Wearable to an Electrocardiogram Gold Standard as a Measure of Heart Rate Under Psychological Stress: A Validation Study. JMIR Form Res. 2022 Dec;6(12):e37885. [CrossRef]

- Oweis K, Quteishat H, Zgoul M, Haddad A. A Study on the Effect of Sports on Academic Stress using Wearable Galvanic Skin Response. In: 2018 12TH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON MEDICAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY (ISMICT) [Internet]. New York: IEEE; 2018 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. p. 99–104. (International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology). Available from: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000458679300042. [CrossRef]

- Tutunji R, Kogias N, Kapteijns B, Krentz M, Krause F, Vassena E, et al. Detecting Prolonged Stress in Real Life Using Wearable Biosensors and Ecological Momentary Assessments: Naturalistic Experimental Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2023;25(1). [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov SVS, Thuras PD, Finzel R, Eppel J, Kotlyar M. Using consumer-wearable technology for remote assessment of physiological response to stress in the naturalistic environment. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3). [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Moreno MA, Carrillo-Tijerina P, Candela-Leal MO, Alanis-Espinosa M, Tudón-Martínez JC, Roman-Flores A, et al. Evaluation of a fast test based on biometric signals to assess mental fatigue at the workplace—A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(22). [CrossRef]

- Kang S, Choi W, Park CY, Cha N, Kim A, Khandoker AH, et al. K-EmoPhone: A Mobile and Wearable Dataset with In-Situ Emotion, Stress, and Attention Labels. Sci Data. 2023 Jun 2;10(1):351. [CrossRef]

- Kang J, Park D. Stress Management Design Guideline with Smart Devices during COVID-19. Archives of Design Research. 2022;35(4):115–31. [CrossRef]

- Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):e14. [CrossRef]

- Maglogiannis I, Trastelis F, Kalogeropoulos M, Khan A, Gallos P, Menychtas A, et al. AI4Work Project: Human-Centric Digital Twin Approaches to Trustworthy AI and Robotics for Improved Working Conditions in Healthcare and Education Sectors. In: Mantas J, Hasman A, Demiris G, Saranto K, Marschollek M, Arvanitis TN, et al., editors. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics [Internet]. IOS Press; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://ebooks.iospress.nl/doi/10.3233/SHTI240581. [CrossRef]

- Zlatintsi A, Filntisis PP, Garoufis C, Efthymiou N, Maragos P, Menychtas A, et al. E-Prevention: Advanced Support System for Monitoring and Relapse Prevention in Patients with Psychotic Disorders Analyzing Long-Term Multimodal Data from Wearables and Video Captures. Sensors. 2022 Jan;22(19):7544. [CrossRef]

- Vouzis E, Maglogiannis I. Prediction of Early Dropouts in Patient Remote Monitoring Programs. SN Comput Sci. 2023 Jun 22;4(5):467. [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos A, Rachiotis T, Maglogiannis I. An Overview of Tools and Technologies for Anxiety and Depression Management Using AI. Appl Sci. 2024 Jan;14(19):9068. [CrossRef]

- Koulouris D, Menychtas A, Maglogiannis I. An IoT-Enabled Platform for the Assessment of Physical and Mental Activities Utilizing Augmented Reality Exergaming. Sensors. 2022 Jan;22(9):3181. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).