Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

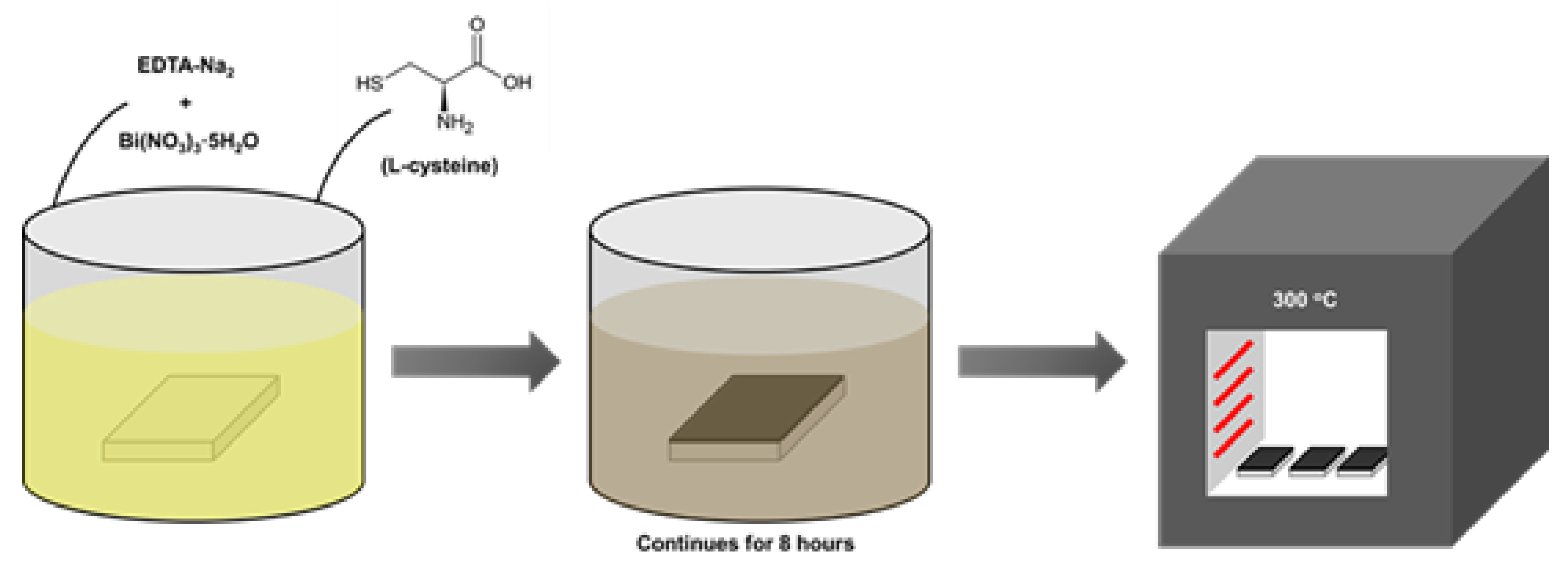

2.2. Formation of Bi2S3 Films

2.3. Characterization Methods of Bi2S3 Films

3. Results and Discussion

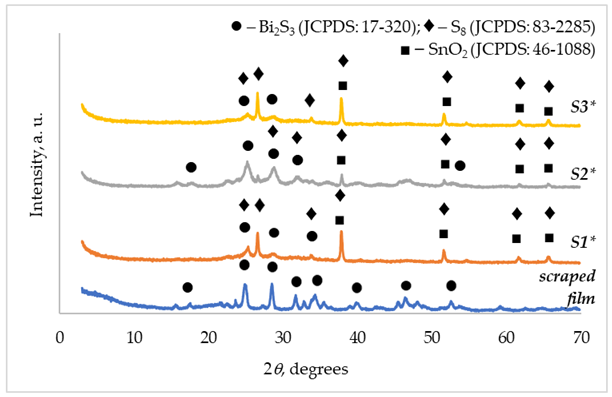

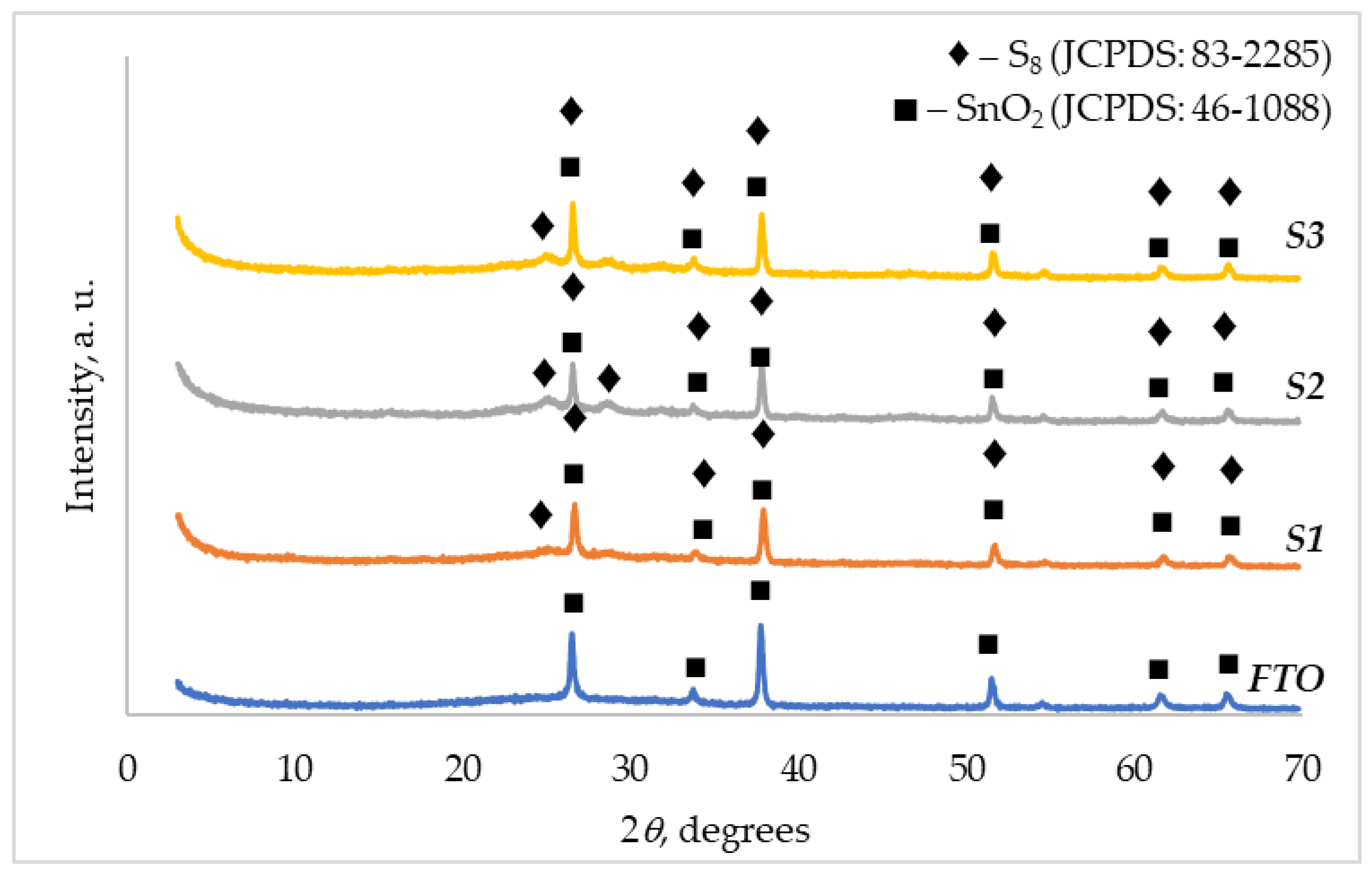

3.1. XRD Characterization

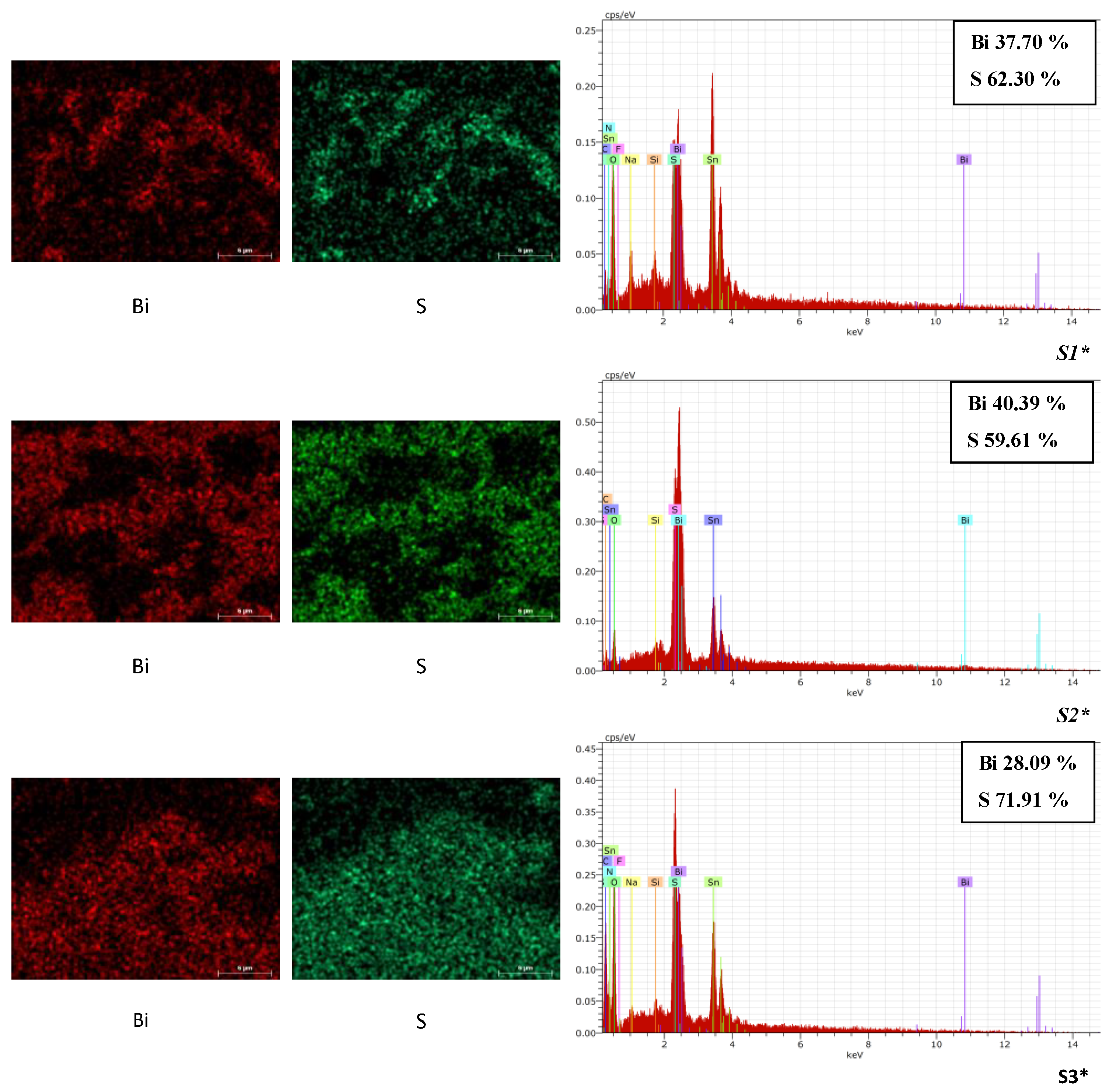

3.2. SEM/EDX Characterization

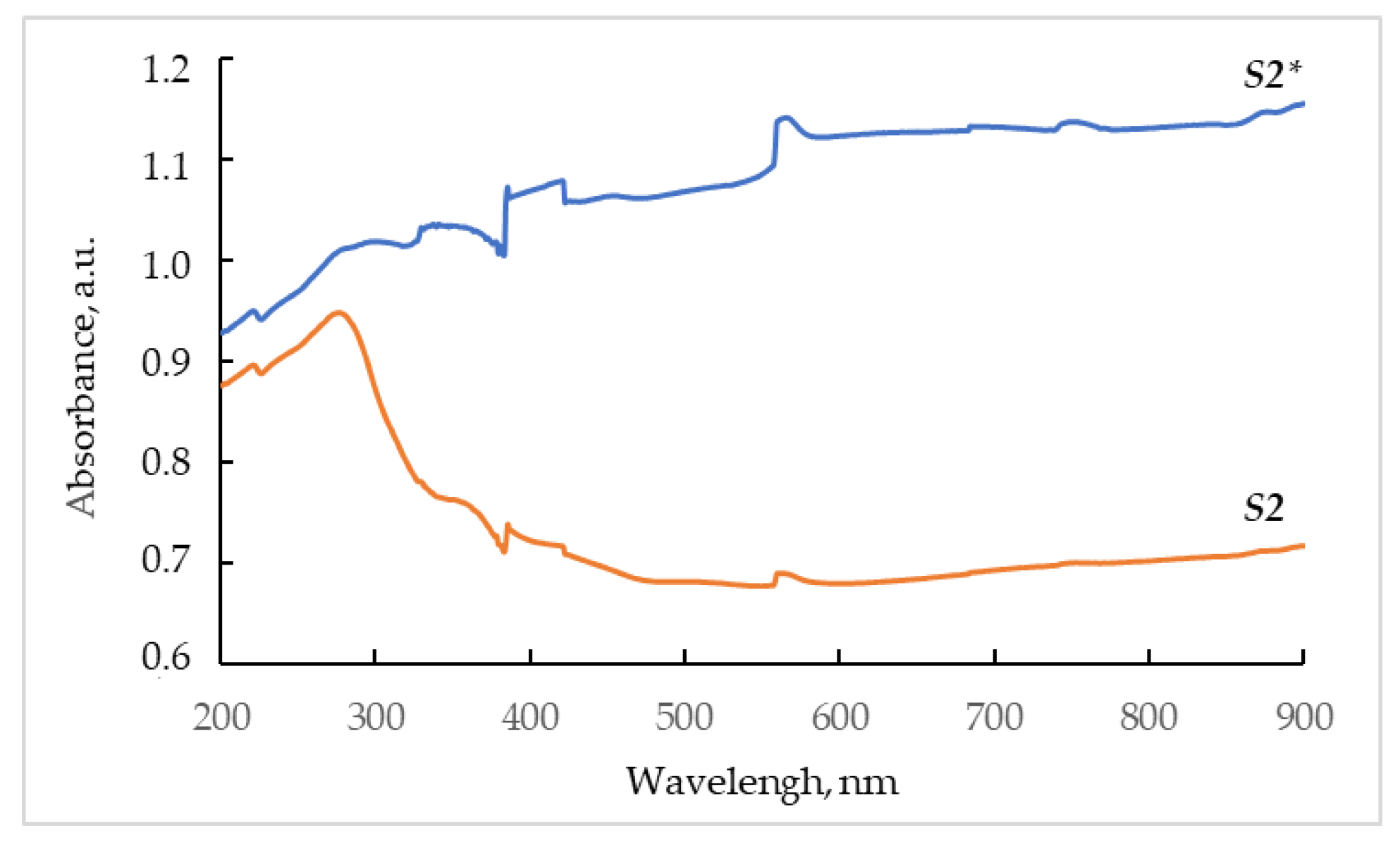

3.3. UV–Vis Spectroscopy Analysis

4. Conclusions

References

- A.T. Supekar, P.K. Bhujbal, S.A. Salunke, S.M. Rathod, S.P. Patole, H.M. Pathan, Bismuth Sulfide and Antimony Sulfide-Based Solar Cells: A Review, ES Energy and Environment 19 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Renuka Devee D, Sivanesan T, Muthukrishnan R․M, Pourkodee D, Mohammed Yusuf Ansari P, Abdul Kader S․M, Ranjani R. A novel photocatalytic activity of Bi2S3 nanoparticles for pharmaceutical and organic pollution removal in water remediation, Chemical Physics Impact 8 (2024) 100605. [CrossRef]

- F.S. Razavi, M.A. Mahdi, D. Ghanbari, E.A. Dawi, M.J. Abed, S.H. Ganduh, L.S. Jasim, M. Salavati-Niasari, Fabrication and design of four-component Bi2S3/CuFe2O4/CuO/Cu2O nanocomposite as new active materials for high performance electrochemical hydrogen storage application, J Energy Storage 94 (2024) 112493. [CrossRef]

- P. Rong, S. Gao, S. Ren, H. Lu, J. Yan, L. Li, M. Zhang, Y. Han, S. Jiao, J. Wang, P. Rong, S. Gao, S. Ren, Y. Han, S. Jiao, J. Wang, H. Lu, J. Yan, L. Li, M. Zhang, Large-Area Freestanding Bi2S3 Nanofibrous Membranes for Fast Photoresponse Flexible IR Imaging Photodetector, Adv Funct Mater 33 (2023) 2300159. [CrossRef]

- A. Singh, P. Chauhan, A. Verma, B.C. Yadav, Interfacial engineering enables polyaniline-decorated bismuth sulfide nanorods towards ultrafast metal–semiconductor-metal UV-Vis broad spectra photodetector, Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 7 (2024) 1–17. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, J. Xie, Y. Tang, Z. Lu, J. Hu, Y. Wang, Y. Cao, Oxygen Self-Doping Bi2S3@C Spheric Successfully Enhanced Long-Term Performance in Lithium-Ion Batteries, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 16 (2024) 52423–52431. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, Z. Hu, S.Y. Lien, Y. Yu, P. Gao, Self-Powered Thermoelectric Hydrogen Sensors Based on Low-Cost Bismuth Sulfide Thin Films: Quick Response at Room Temperature, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 14 (2022) 47696–47705. [CrossRef]

- H. Kan, W. Yang, Z. Guo, M. Li, Highly sensitive room-temperture NO2 gas sensor based on Bi2S3 nanorods, Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 35 (2024) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- P. Terdalkar, D.D. Kumbhar, S.D. Pawar, K.A. Nirmal, T.G. Kim, S. Mukherjee, K. V. Khot, T.D. Dongale, Revealing switching statistics and artificial synaptic properties of Bi2S3 memristor, Solid State Electron 225 (2025) 109076. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, Y. Tao, Q. Huang, J. Huang, J. Kuang, R. Gu, P. Zeng, H.Y. Li, H. Liang, H. Liu, Electrochemical Biosensor Employing Bi2S3 Nanocrystals-Modified Electrode for Bladder Cancer Biomarker Detection, Chemosensors 10 (2022) 48. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yang, L. Wang, J. Zhang, J. Liu, X. Yu, Application of bismuth sulfide based nanomaterials in cancer diagnosis and treatment, Nano Today 49 (2023) 101799. [CrossRef]

- M. Bouachri, M. Oubakalla, H. El Farri, C. Díaz-Guerra, J. Mhalla, J. Zimou, A. El-Habib, M. Beraich, K. Nouneh, M. Fahoume, P. Fernández, A. Ouannou, Substrate temperature effects on the structural, morphological and optical properties of Bi2S3 thin films deposited by spray pyrolysis: An experimental and first-principles study, Opt Mater (Amst) 135 (2023) 113215. [CrossRef]

- K. Rodríguez-Rosales, J. Cruz-Gómez, J. Santos Cruz, A. Guillén-Cervantes, F. de Moure-Flores, M. Villagrán-Muniz, Plasma emission spectroscopy for studying Bi2S3 produced by pulsed laser deposition and effects of substrate temperature on structural, morphological, and optical properties of thin films, Materials Science and Engineering: B 312 (2025) 117867. [CrossRef]

- U. Atamtürk, E. Jung, T. Fischer, S. Mathur, Tale of Two Bismuth Alkylthiolate Precursors’ Bifurcating Paths in Chemical Vapor Deposition, Chemistry of Materials 34 (2022) 7344–7356. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ran, Y. Song, X. Jia, P. Gu, Z. Cheng, Y. Zhu, Q. Wang, Y. Pan, Y. Li, Y. Gao, Y. Ye, Y. Ran, Y. Song, X. Jia, P. Gu, Z. Cheng, Y. Zhu, Q. Wang, Y. Pan, Y. Li, Y. Gao, Y. Ye, Large-Scale Vertically Interconnected Complementary Field-Effect Transistors Based on Thermal Evaporation, Small 20 (2024) 2309953. [CrossRef]

- T.O. Ajiboye, D.C. Onwudiwe, Bismuth sulfide based compounds: Properties, synthesis and applications, Results Chem 3 (2021) 100151. [CrossRef]

- S. Fischetti, D. Marolf, A.C. Wall -, M. Rangamani, T. Wiseman -, N. Mukurala, R. Kumar Mishra, S. Hun Jin, A. Kumar Kushwaha, Sulphur precursor dependent crystallinity and optical properties of solution grown Cu2FeSnS4 particles, Mater Res Express 6 (2019) 085099. [CrossRef]

- C. Behera, R. Samal, A.K. Panda, C.S. Rout, S.L. Samal, Synthesis of flower and biconcave shape CuS: Enhancement of super-capacitance properties via Ni–CuS nanocomposite formation, Solid State Sci 117 (2021) 106631. [CrossRef]

- T. Fazal, S. Iqbal, M. Shah, B. Ismail, N. Shaheen, A.I. Alharthi, N.S. Awwad, H.A. Ibrahium, Correlation between structural, morphological and optical properties of Bi2S3 thin films deposited by various aqueous and non-aqueous chemical bath deposition methods, Results Phys 40 (2022) 105817. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Xiao, X.J. Liao, H. Wang, S.W. Ren, J.T. Cao, Y.M. Liu, In Situ Formation of Bi2MoO6-Bi2S3 Heterostructure: A Proof-Of-Concept Study for Photoelectrochemical Bioassay of l-Cysteine, Front Chem 10 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Yan, K. Chang, T. Ni, K. Li, l-cysteine assisted synthesis of Bi2S3 hollow sphere with enhanced near-infrared light harvesting for photothermal conversion and drug delivery, Mater Lett 245 (2019) 158–161. [CrossRef]

- X. Tao, X. Hu, Z. Wen, Y. Ming, J. Li, Y. Liu, R. Chen, Highly efficient Cr(VI) removal from industrial electroplating wastewater over Bi2S3 nanostructures prepared by dual sulfur-precursors: Insights on the promotion effect of sulfate ions, J Hazard Mater 424 (2022) 127423. [CrossRef]

- R. Guo, G. Zhu, Y. Gao, B. Li, J. Gou, X. Cheng, Synthesis of 3D Bi2S3/TiO2 NTAs photocatalytic system and its high visible light driven photocatalytic performance for organic compound degradation, Sep Purif Technol 226 (2019) 315–322. [CrossRef]

- P. Coppens, Y.W. Yang, R.H. Blessing, W.F. Cooper, F.K. Larsen, The Experimental Charge Distribution in Sulfur Containing Molecules. Analysis of Cyclic Octasulfur at 300 and 100 K, J Am Chem Soc 99 (1977) 760–766. [CrossRef]

- Pekoite, CuPbBi 11 S 18 , a new member of the bismuthinite-aikinite mineral series; its crystal structure and relationship with naturally- and synthetically-formed members | The Canadian Mineralogist | GeoScienceWorld, (n.d.). https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/mac/canmin/article-abstract/14/3/322/11114/Pekoite-CuPbBi-11-S-18-a-new-member-of-the (accessed March 11, 2025).

- R. Ivanauskas, L. Samardokas, M. Mikolajunas, D. Virzonis, J. Baltrusaitis, Polyamide–thallium selenide composite materials via temperature and pH controlled adsorption–diffusion method, Appl Surf Sci 317 (2014) 818–827. [CrossRef]

- A. Ivanauskas, R. Ivanauskas, I. Ancutiene, Effect of In-Incorporation and Annealing on CuxSe Thin Films, Materials 2021, Vol. 14, Page 3810 14 (2021) 3810. [CrossRef]

- P. Makuła, M. Pacia, W. Macyk, How To Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV-Vis Spectra, Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 9 (2018) 6814–6817. [CrossRef]

| Sample No. | Solution and cocentration, mol/L | L-Cysteine | Total volume of solution, mL | ||

| Bi(NO3)3 × 5H2O | EDTA-Na2- | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.025 | ||||

| Volume of solutions taken for the experiment, mL | Weight, g | Concentration, mol/L | |||

| S1 | 25 | 30 | 1.0 | 0,15 | 55 |

| S2 | 25 | 30 | 1.5 | 0.23 | 55 |

| S3 | 25 | 30 | 2.0 | 0.30 | 55 |

| Concentration of solutions used for the experiment, mol/L | |||||

| 0.0055 | 0.0014 | – | – | 55 | |

| XRD pattern name | Symbol in Figure 2 and Figure 3 – crystallographic phase (JCPDS file number): peak positions 2θ, degrees | |

| S1 | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 25.02; 26.66; 33.87; 37.91; 51.69; 61.74; 65.72 |

| S2 | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 25.01; 26.59; 28.63; 33.85; 37.81; 51.64; 61.74; 65.70 |

| S3 | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 24.98, 26.61; 33.86; 37.89; 51.65; 61.72; 65.71 |

| FTO | (■) SnO2 (JCPDS: 46-1088) | 26.66; 33.87; 37.91; 51.69; 61.74; 65.72 |

| S1* | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 26.66; 33.87; 37.91; 51.69; 61.74; 65.72 |

| (●) Bi2S3 (JCPDS: 17-320) | 25.21; 33.83; | |

| S2* | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 28.63; 31.89; 37.81; 51.58; 61.64; 65.60 |

| (●) Bi2S3 (JCPDS: 17-320) | 17.69; 25.20; 28.75; 31.89; 52.56 | |

| S3* | (◆) S8 (JCPDS: 83-2285) | 26.57; 33.76; 37.82; 51.60; 61.67; 65.61 |

| (●) Bi2S3 (JCPDS: 17-320) | 25.20 | |

| Scraped film | (●) Bi2S3 (JCPDS: 17-320) | 17.43; 24.98; 28.67; 31.85; 35.51; 39.92; 46.42; 52.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).