1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Challenge

The global food system, while essential for sustaining life, is also a major driver of environmental degradation and climate change. This paradox raises a critical question: can consumer choices help mitigate this crisis and steer the food system toward sustainability? Agriculture and livestock account for 24% of greenhouse gas emissions, 80% of deforestation, and 90% of fishery depletion (FAO, 2020; Mazhar & Zilahy, 2023). The situation emphasizes the urgent need for systemic change (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2019; Suh & Yoo, 2024).

Environmental challenges are further exacerbated by the social and economic consequences. Not only global supply chains are threaten by the reduction of agriculture productivity due to climate change, the overexploitation of natural resources is also jeopardizing food security for the vulnerable populations (Al-Daher, 2023; Poore & Nemecek, 2018). Unpredictable weather and droughts cause crop failures, raising food prices and reducing accessibility (Woodhill et al., 2022). Therefore, behavioural shift among consumers needs serious attention to address the interconnected crisis.

1.2. Global Sustainability Efforts

United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) prioritizes the shifting towards sustainable consumption patterns. SDG 12 emphasizes responsible consumption, while SDG 13 targets climate action through behavioural change (Chen, 2022; United Nations, 2024). Such goals reflect a growth in recognition of consumer’s role towards sustainable future.

However, progress remains limited because of economic constraints, misleading marketing, and scarce sustainable options (Rozenkowska, 2023; Vargas-Merino et al., 2023). On the affordability side, lower-income households are affected by affordability; on the trust side, misinformation saps trust in eco-labels (Meixner et al., 2021). Greater challenges to overcome, highlights the urgency to develop strong psychological frameworks through which consumers may overcome these challenges.

1.3. The Role of Consumer Behaviour

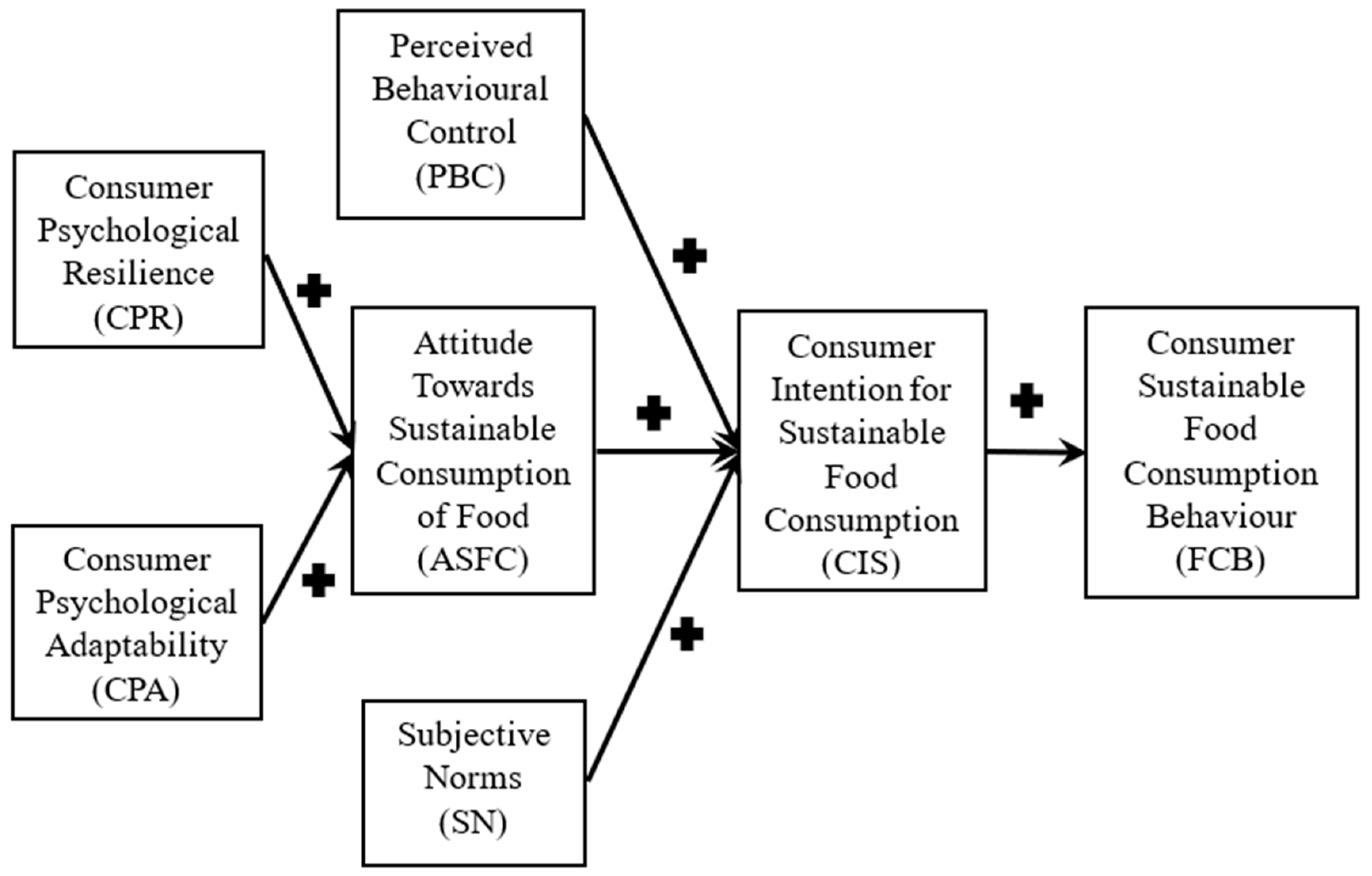

Being the final decision makers, consumer’s demands directly influence food production and distribution systems. Prominent theories like TPB offers a holistic overview of consumer decision-making processes. TPB identifies attitudes toward sustainable food consumption (ASFC), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioural control (PBC) as critical determinants of behaviour (Ajzen, 1985; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2008).

Despite explaining the cognitive drivers TPB does not adequately addresses the external pressures such as economic instability or environmental crises that disrupts consumer intentions (Rozenkowska, 2023; W. Sun, 2020). For instance, Pais et al. (2022) mention that consumer perceived value for the sustainable food practices deteriorate due to higher cost and limited availability of sustainable options in local markets. This gap underscores the need for additional constructs like consumer resilience and adaptability in the face of said challenges.

1.4. Introducing Psychological Constructs: CPR and CPA

Emerging research highlights the importance of constructs like psychological resilience and adaptability in fostering sustainable consumption behaviours (Azam et al., 2024; Ruggerio, 2021). CPR is referred to as a capacity to maintain sustainable practices despite external pressures, such as misleading marketing or financial constraints. Even in challenging circumstances, resilient consumers are highly likely to resist unsustainable temptations and prioritize environmentally conscious decisions (Glandon, 2015; Rew & Minor, 2018). For example, resilient consumers may continue to prioritize eco-labelled products despite financial constraints, demonstrating their commitment to sustainability.

Complementing CPR, CPA is the ability to modify behaviours in response to dynamic environmental and market conditions. CPA allows consumers to embrace sustainable practices such as adopting eco-labelled products (Folke et al., 2010; Sandra N. et al., 2021). For instance, Safdar et al. (2022) mentioned that consumers with high adaptability might shift towards plant-based diets or choose eco-labelled products during meat shortages. Combining, CPR and CPA form the Social-Ecological Systems (SES) theory, being drivers of sustainable trajectory, offers a framework for addressing the limitations of TPB, offering actionable insights into promotion of sustainable food consumption.

1.5. Research Gap

Verily, based upon SES, resilience and adaptability are key sustainability drivers (Bossel, 1999; Ruggerio, 2021); however, there application to individual-level consumer behaviour is limited, leaving critical gaps in addressing real-world challenges like affordability, misinformation, and behavioural inertia etc. Harmonizing these divides is essential for developing a comprehensive framework that addresses both theoretical limitations and practical applications.

1.6. Research Questions

To address these gaps, this study investigates the following questions:

How CPR and CPA can enhance the predictive power of TPB in sustainable food consumption?

What role does CPR and CPA plays in enabling consumers to maintain sustainable practices despite external pressures?

How integrating SES and TPB can provide actionable insights into fostering sustainable food consumption behaviour?

1.7. Research Objectives

This study aims:

To integrate SES and TPB to develop a framework for sustainable consumption of food.

To examine the influence of CPR and CPA on formations consumer attitudes for sustainable food consumption.

Proposing actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners to promote sustainable food practices.

2. Research Methodology

Study employs a systematic narrative literature review to integrate CPR and CPA. This method is particularly suitable for the emerging fields in embryonic stages. This method offers flexibility to explore the complex and interdisciplinary constructs (Budak et al., 2021; Ferrari, 2015). Through synthesis of insights form TPB and SES theory, the approach facilitates an understanding of the convoluted interaction between nature and human behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Folke et al., 2010).

Unlike meta-analyses requiring extensive quantitative data, narrative reviews synthesize diverse theoretical and empirical insights (Baumeister & Leary, 1997; Greenhalgh et al., 2018; Baethge et al., 2019; Varpio et al., 2021). These distinguished feature makes this approach ideal for the underexplored CPR and CPA while enriching the understanding and predictability of consumer behaviour.

2.1. Database Selection

Google scholar and SCOPUS were utilised to ensure the broad and quality coverage of the pertinent literature. The inclusion of SCOPUS is based upon its comprehensive indexing of peer-reviewed journals, specifically in the sustainability and social sciences research (Abdullahi et al., 2023; Gusenbauer, 2024). Google scholar was included to capture the emerging studies, conference papers, and grey literature that may not yet be indexed in SCOPUS (Haddaway et al., 2015; Schöpfel & Prost, 2020).

Study did not use other databases like Web of Science or ProQuest as they were either limited by access, domain specificity, or overlap with SCOPUS (Martín-Martín et al., 2018; Zhu & Liu, 2020). While Web of Science is regarded as a reliable data source, its coverage of the sustainability and consumer behaviour literature is limited (de Oliveira et al., 2022); additionally, ProQuest has a different focus on studies with a more applied perspective than a theoretical framework (Korkmaz & Altan, 2024). In light of the aforementioned factors, the final pipeline of SCOPUS and Google Scholar exhibited an appropriate balance of comprehensiveness, accessibility, and methodological rigour, signifying best practice choices for searches in systematic reviews (Gusenbauer, 2024).

2.2. Keyword Development and Search Strings

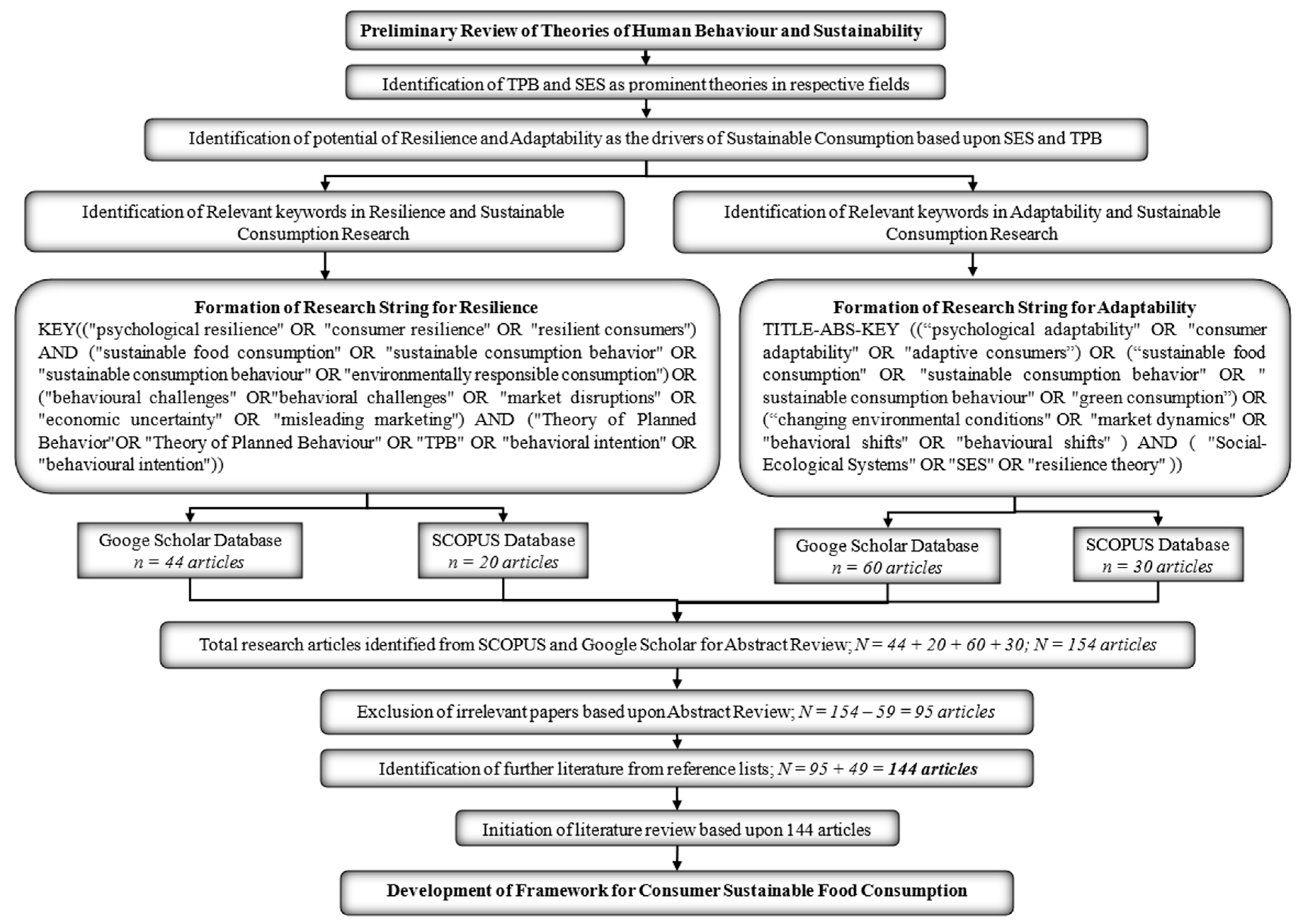

Preliminary review was conducted prior to initiating the literature search; as it helped to identify prominent theories in sustainability and human behaviour. The review identified SES and TPB as foundational, emphasizing resilience and adaptability as key drivers. Therefore, based upon preliminary review, relevant keywords were identified to guide the search process, focusing on resilience, adaptability, and sustainable consumption research. Search strings were crafted following established guidelines by Cairo et al. (2019) and are presented in

Figure 1. The search resulted in 44 and 20 articles in Google Scholar and SCOPUS, respectively, for resilience, and 60 and 30 articles, respectively, for adaptability. In a total of 154 articles were identified for abstract review.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion and inclusion criteria were systematically administered to ensure that the relevant literature offers highest standards of relevance, rigor, and alignment with the study’s objectives. Articles were included if conceptually, theoretically, or empirically relevant to CPR, CPA, SES, or TPB (Hogan, 2019; Snyder, 2019). Only peer-reviewed journal articles were included, ensuring methodological rigor, quality and credibility of findings (Fernandez-Olit et al., 2019). Articles lacking specificity, depth, or relevance were excluded (Chapman, 2021; Coombes, 2023). Non-English articles were also excluded due to translation limitations. Overall, application of these criteria resulted in the exclusion of 59 articles, leaving 95 articles for full-text review.

2.4. Reference List Screening

Reference lists were screened to identify additional literature. The process resulted 49 pertinent articles, bringing the total number of articles reviewed to 144. Complete methodology process is depicted in

Figure 1.

2.5. Thematic Analysis and Synthesis

A systematic identification of patterns and theoretical linkages was used through a thematic synthesis approach to analyse the selected literature. The analysis was conducted using a thematic framework in a structured iterative process of coding, theme identification and synthesis (Clarke & Braun, 2017; Nowell et al., 2017; Willig & Rogers, 2017).

A deductive as well as inductive coding approach was applied to allow for both theoretical alignment and detection of emerging patterns. Deductive coding was guided by pre-established themes from the SES and TPB frameworks, which ensured that findings were in line with existing literature (Folke, 2016; Klöckner, 2013). Employing the inductive coding approach, thereby, facilitated the emergence of new constructs and contextual factors shaping consumer sustainable food purchase behaviour and consumption behaviour, rather than being limited by existing theoretical assumptions (Gioia et al., 2013; Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

A manual thematic coding process ensured methodological soundness while keeping the deep and robust engagement the of literature. Key themes were organized according to conceptual relevance and empirical anchoring. The inter-related themes identified were: (i) psychological constructs associated with resilience and adaptability in consumer decision-making, (ii) an intersection between the SES and TPB regarding behavioral drivers, and (iii) barriers and facilitators to sustainable food consumption.

The study further enhanced the trustworthiness of synthesis by peer validation with domain experts to confirm coding consistency and theoretical rigor (Hemmler et al., 2022; Maher et al., 2018). Software like NVivo was considered but in order to remain close to the data, manual analysis was embraced to promote depth of interpretation and theoretical alignment.

The study tried to follows best practices in scoping reviews, providing methodological clarity and an extensive synthesis of accumulated knowledge. Hence, the conceptual framework presented in this study is based on the findings of the thematic synthesis and contributes to the psychological and behavioral literature on sustainable food consumption.

3. Literature Review

In contemporary epoch, aligning consumption with sustainable patterns is a challenge (Haider et al., 2022; Vermeir et al., 2020). These hurdles were provisioned by previous researchers such as the resource management theory of Hotelling (1931), the insights provided by the Club of Rome (Meadows et al., 1972) and the Brundtland Report (Hariem Brundtland, 1985). These historic and seminal works emphasized that current needs should be met only without compromising future generations with its needs (Ferreira da Cunha & Missemer, 2020; Kuhlman & Farrington, 2010). Hence, it is becoming essential to align consumption practices with ecological limits and societal goals (da Rocha Ramos et al., 2022; Hristov et al., 2021; Ibáñez-Rueda et al., 2020).

3.1. Understanding Consumer Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviour

Consumers are pivotal in driving sustainable food consumption by making responsible choices that align with environmental goals (Bhatti et al., 2019; Bouman et al., 2020; Lubowiecki-Vikuk et al., 2021). Although businesses play a supportive role, consumers’ behaviours ultimately shape demand, influencing market trends toward sustainability (Cherrier & Türe, 2022). Techniques of empowering consumers with knowledge, providing access to sustainable options and acknowledging their importance in current environmental crisis are critical in fostering sustainable consumption of food (Luo et al., 2023).

Consumer sustainable food consumption behaviour is referred to as choosing, purchasing, and using food in ways that minimize environmental impact while supporting economic and social sustainability (Akenji, 2014; Polzin et al., 2023). Earlier studies have explored environmentally conscious behaviours through demographics and social awareness (Kinnear et al., 1974; McCarty & Shrum, 1994). However, understanding of sustainable food consumption remains complex and underexplored (Bangsa & Schlegelmilch, 2020). Despite awareness, unsustainable practices persist, warranting further investigation (Trudel, 2019). Advancing research on sustainable food consumption behaviours is essential to promote environmentally responsible choices and align consumer actions with sustainability goals (Janssen et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2017). Hence, identifying novel determinants aligned with sustainability is essential to understanding and promoting consumer sustainable consumption behaviours.

3.2. Identifying the Determinants of Consumer Sustainable Consumption Behaviour: Converging SES and TPB

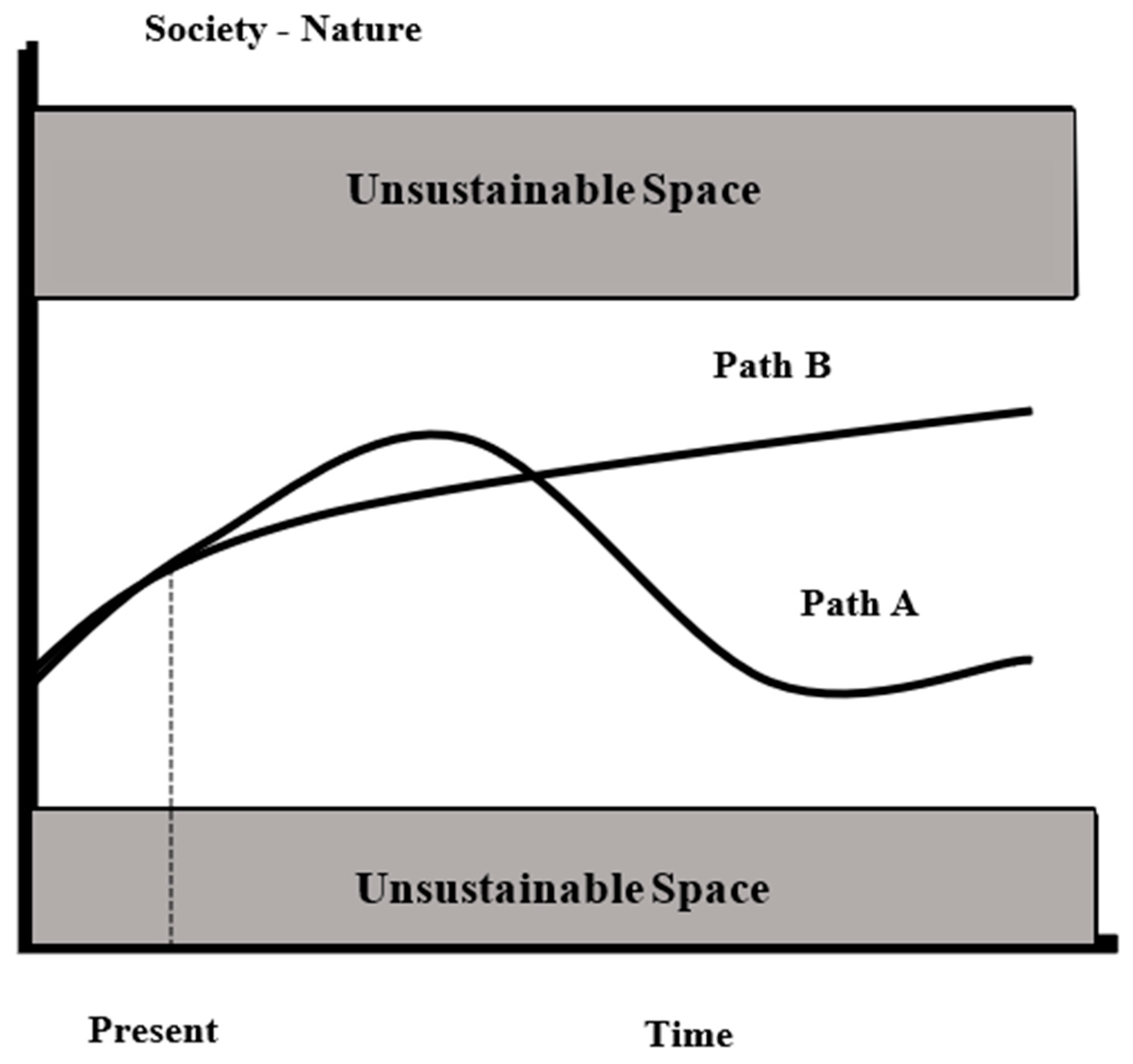

One of the prominent attempts to elaborate on sustainability is of Bossel (1999). Bossel (1999) devised the three categories of constraints. Where, the first are physical constraints, like resource availability and ecosystem capacity. Second category is focused on the nature of humans, their culture, social organization, technology and the indulgence of ethics and values. Third category includes the temporality of nature along with the anthropic processes and their respective evolution. Given these limits, Bossel (1999), devised the space (see

Figure 2) that limits the strategic as well as the political paths towards sustainability. Bossel’s concept of a sustainable space was presented in a simplified manner and it does not explain how society can traverse the sustainable path or identify the drivers that will lead to this path. In order to determine the drivers of future sustainable trajectory, based upon the seminal work of Holling (1973) and the respective SES theory; Holling (1973), Ludwig et al. (1997) and B. Walker et al. (2004) as endorsed by Ruggerio, (2021) stated that attributes crucial to achieving a sustainable trajectory are

resilience and

adaptability.

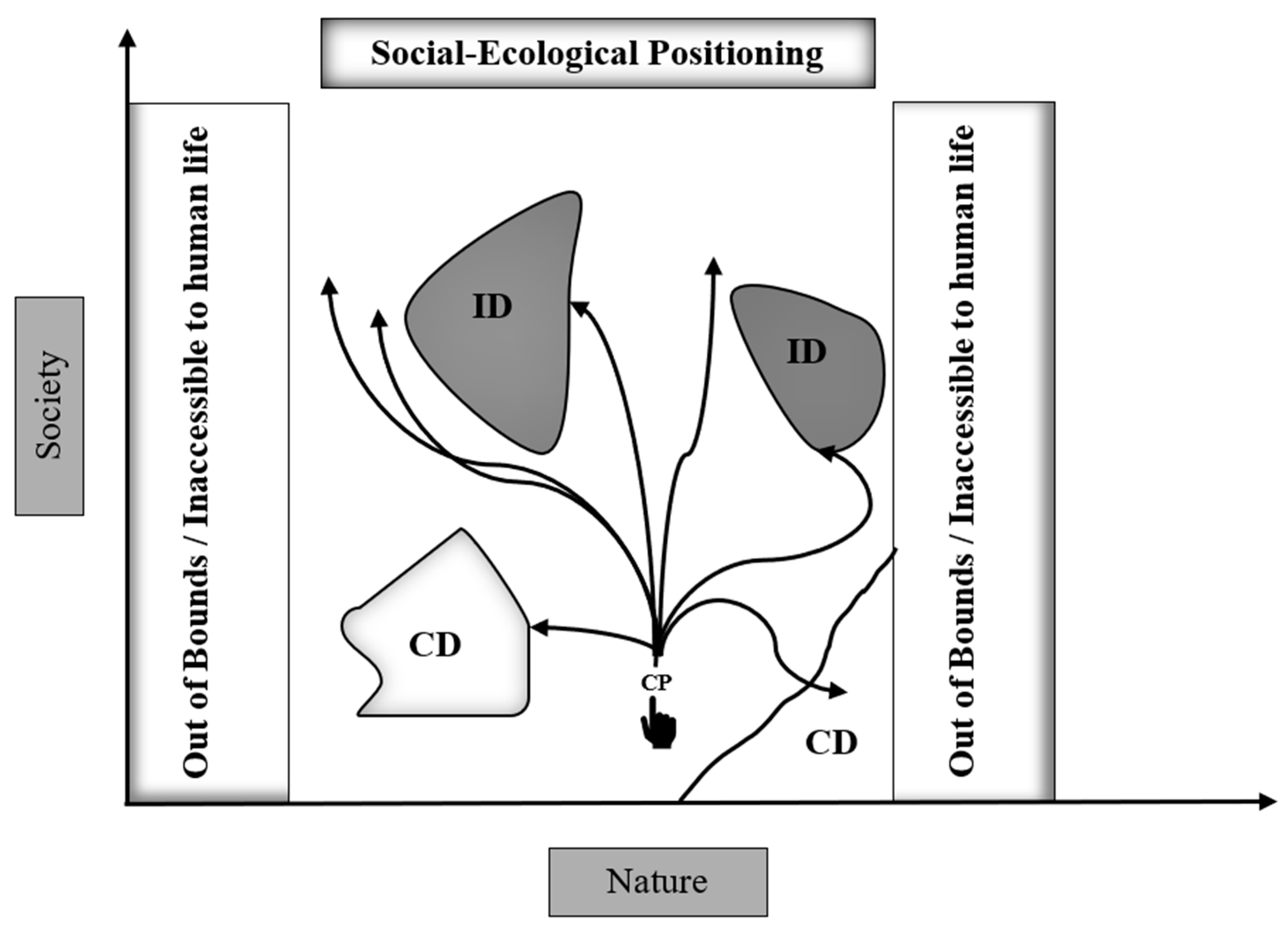

Ruggerio (2021) visualizes sustainability as the desired positioning between society and nature and acknowledges the presence of inaccessible domains (IDs) and catastrophic domains (CDs) or basins (see

Figure 3). IDs is the domain where, once entered, the system, society or consumer becomes rigid, unresponsive to change, and lacks flexibility. On the other hand, the CDs mean that the system, society or consumer is too sensitive to the changes and make transformation in the face of small perturbations. Maneuvering through these basins is convoluted as it depends upon the internal dynamics and the external perturbations. Therefore, resilience along with adaptability will decide the future positioning in the face of external adversaries and perturbations (Ruggerio, 2021).

Though the Theory of Planned behaviour (TPB) provides a framework for understanding consumer behaviour, it has been extensively criticised for its failure to account for complex real-world behaviours, especially in the area of sustainable consumption (Ayar & Gürbüz, 2021; Shen et al., 2022). High behavioral intentions do not always convert into behaviour and one of the crucial criticisms of TPB which further led researchers to identify this gap is the intention-behaviour gap (Lihua, 2022; More & Phillips, 2022). Empirical studies demonstrate that, despite positive pro-environmental attitudes, due to various external constraints like affordability, availability, convenience, consumers seldom engage in sustainable behaviours (Čapienė et al., 2021, 2022; Do & Do, 2024). In the case of sustainable food consumption, for example, the data suggests that though both subjective norm and attitude are significantly correlated with intention to consume sustainable foods, those intentions do not always translate into purchasing behaviour, often as a result of economic and structural barriers (Alam et al., 2024; He & Sui, 2024; Jakubowska et al., 2024).

A second major limitation is TPB’s undue focus on rational choice. The central assumption behind the framework is that people are rational and logical actors who consciously assess their attitudes, norms, and perceptions of control (Osiako & Szente, 2024). But, substantial research in behavioral science shows that many consumer behaviours are habitual, emotional, or based on unconscious biases (Chen, 2024; Mata-Marín et al., 2023; Sun, 2023). Research on sustainable consumption shows that impulse buys, marketing pressure and habitual consumption behavioural patterns often trump rational intentions to behave sustainably (Shen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). TPB fails to consider habit formation and automaticity and falls short in explaining unsustainable behaviours, where many people find it difficult to break the habit of unsustainable consumption (Ashaduzzaman et al., 2022; Çoker & van der Linden, 2022).

Moreover, the restricted predictive validity of TPB in the context of sustainability research also constrains its applicability (Sharma et al., 2023; Tommasetti et al., 2018). Meta-analyses show that TPB alone can only explain 20% to 30% of the variance in actual consumer behaviour (Ahmmadi et al., 2021; Al-Sultan et al., 2024; Armitage & Conner, 2001), leaving a considerable amount of behaviour unexplained. This highlights the necessity for other psychological constructs that would increase the predictive power of TPB (Haider et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2022). By integrating Consumer Psychological Resilience (CPR) and Consumer Psychological Adaptability (CPA) into TPB, this study extends the framework to reflect how individuals maintain sustainable behaviours in the face of external pressures and adjust to new conditions. The Social-Ecological Systems (SES) theory asserts the inclusion of these dimensions (Azam et al., 2024; Walker et al., 2004) and thus the convergence of TPB and SES provides a more realistic and complete explanation of behavioral outcomes in the field of sustainable food consumption than TPB.

3.3. The Role of Consumer Psychological Resilience (CPR) in Shaping Consumer’s Attitudes Towards Sustainable Food Consumption (ASFC)

The SES framework emphasizes on the interplay of human and environmental systems and has regarded resilience as the crucial factor in sustainability (Berkes & Ross, 2013; Davidson et al., 2016; Holling, 1973). Therefore, consumer sustainable consumption behaviour is deeply intertwined with the SES principles, marking the interdependence between individuals and ecological systems (Crawford et al., 2020; Folke, 2016). As CPR reflects the individual’s capacity to cope and thrive amid adversity (Reyers et al., 2022), hence, is plays a transformative role in driving sustainable consumption. CPR emerges as a repertoire of behavioural tendencies fostering positive adaptation in the face of environmental challenges (Agaibi & Wilson, 2005; Ahern et al., 2008). In this frame of reference, integrating SES theory into consumer behaviour offers a strategic lens for bridging theory and practice. The said approach will also align sustainable consumption with social, economic, and ecological dimensions (Cairns et al., 2020; Walker et al., 2004).

CPR significantly shapes attitudes by enabling individuals to cope with adversity, manage emotions, and behaviours in response to environmental challenges (Rew & Cha, 2020; Southwick & Charney, 2012). CPR fosters cognitive flexibility, empowering consumers to reassess consumption habits, abandon unsustainable practices, and embrace sustainable alternatives (Reivich & Shatté, 2002). Essential resilience components—such as emotion regulation, optimism, and impulse control—further facilitate to develop attitudes toward sustainable consumption (Glandon, 2015; Rew & Minor, 2018). Therefore, resilient consumers better resist marketing influences, and are more inclined to make environmentally conscious decisions showcasing sustainable attitudes (Arnal Sarasa et al., 2020; Reivich & Shatté, 2002).

Psychological studies indicate that resilience promotes positive framing and gets expressed in good decisions made not only about our own lives, but in a variety of areas, environmental issues included. Resilient people have been found to keep pro-environmental attitudes under circumstances that are more challenging (Berenguer, 2010; Demski et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2023). Psychological resilience allows consumers to navigate external and potentially false pressures, creating stronger sustainable food attitudes. Thus, CPR is expected to positively influence attitudes toward sustainable food consumption (see

Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Impact of CPR on ASFC. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 4.

Impact of CPR on ASFC. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

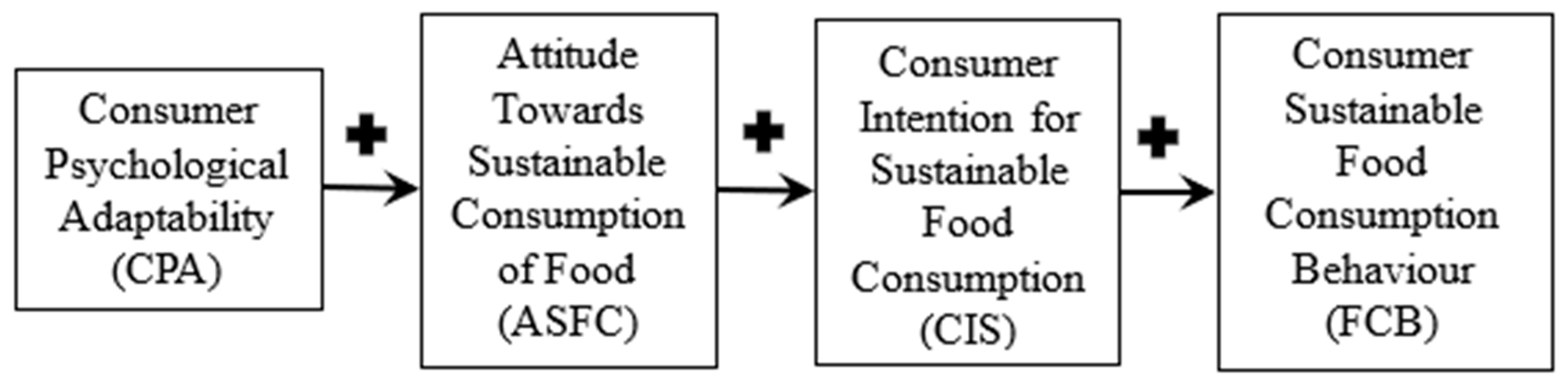

3.4. The Role of Consumer Psychological Adaptability (CPA) in Shaping Consumer’s Attitudes Towards Sustainable Food Consumption (ASFC)

Adaptability encourages continuous learning, emotional regulation, and problem-solving, helping consumers to adopt sustainable behaviours (Kodden, 2020; Wilson, 2021). As environmental disruptions threatens well-being, adaptable consumers proactively shift their attitudes toward sustainable consumption, contributing to the broader adaptive capacity of social-ecological systems (Fazey et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2021). CPA enhances individuals efforts toward sustainability by aligning personal flexibility with long-term environmental goals (Folke, 2016; Hasani et al., 2023; Sandra N. et al., 2021). Aligned with the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1985), psychological adaptability underpins shifts in attitudes and intentions toward sustainable consumption (Saari et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2022). Without embracing change and modifying attitudes, intentions, and behaviours; achieving sustainability becomes a formidable challenge (Shahzalal & Hassan, 2019).

Studies on adaptability indicate that individuals who demonstrate cognitive and behavioral flexibility are more likely to adopt new sustainable consumption behaviors (Barone et al., 2024; Gordon-Wilson, 2022; Lange & Dewitte, 2019). Adaptable consumers are more open to eco-friendly options, willing to adjust to sustainable food transitions, and develop positive sustainability attitudes. Therefore, CPA is expected to significantly influence ASFC by equipping consumers to respond effectively to environmental challenges and embrace sustainable practices (see

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Impact of CPA on ASFC. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 5.

Impact of CPA on ASFC. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

3.5. Formation of Consumer Intentions for Sustainable Food Consumption (CIS)

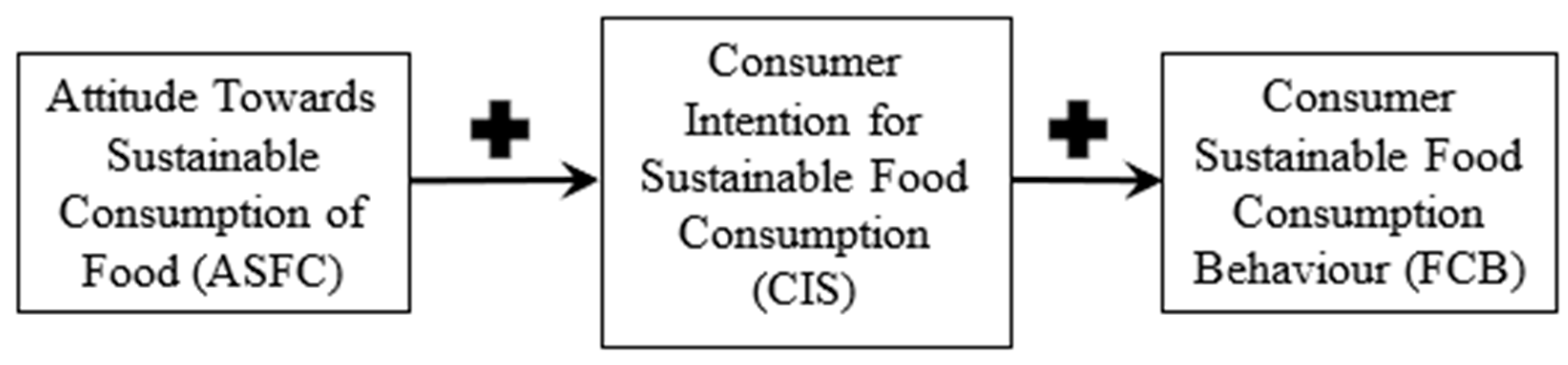

3.5.1. The Role of Attitudes in Shaping CIS

Attitudes are essential precursors to behavioural intentions (Ajzen, 1985; Sparks & Shepherd, 1992), influencing sustainable food consumption. Empirical studies highlight variability in this relationship between ASFC and CIS across cultural contexts—Boobalan and Nachimuthu (2020) report strong associations in India and USA (r = 0.771), while moderate association in Malaysia (r = 0.504) and weak in Pakistan (r = 0.238) (Ahmed et al., 2021). Verily, attitudes shape intentions, though strength of this relationship is complex and context-specific (Al Mamun et al., 2018; Biasini et al., 2021). However, it is well established through TPB that attitudes translates into intentions (Ajzen, 1985b; Islam et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2022); therefore, following relation is proposed (see

Figure 6):

Figure 6.

Role of ASFC in the formation of CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 6.

Role of ASFC in the formation of CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

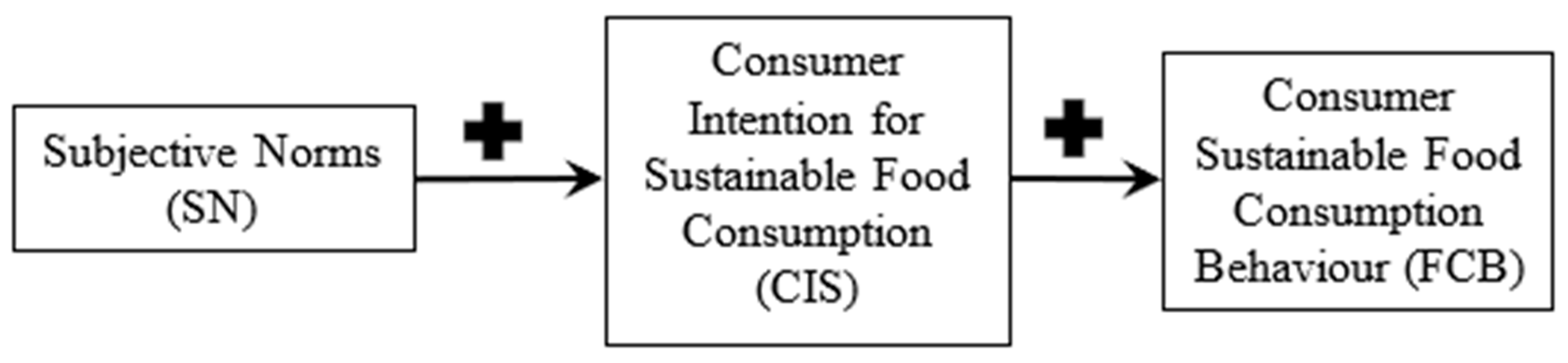

3.5.2. The Role of Subjective Norms in Shaping CIS

Subjective norms (SN) within the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) reflect the social pressures individuals perceive from significant others, such as family, peers, or friends, regarding acceptable behaviours. In sustainable consumption, individuals’ intentions are shaped by social expectations, creating a ripple effect that fosters pro-environmental behaviours (Borusiak et al., 2020). Leveraging SN promotes sustainable practices, reinforcing positive behavioural loops that encourage sustainable food consumption (Bhatti et al., 2019; Scalco et al., 2017). Given the importance, following relation is proposed (see

Figure 7):

Figure 7.

Impact of SN on the development of CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 7.

Impact of SN on the development of CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

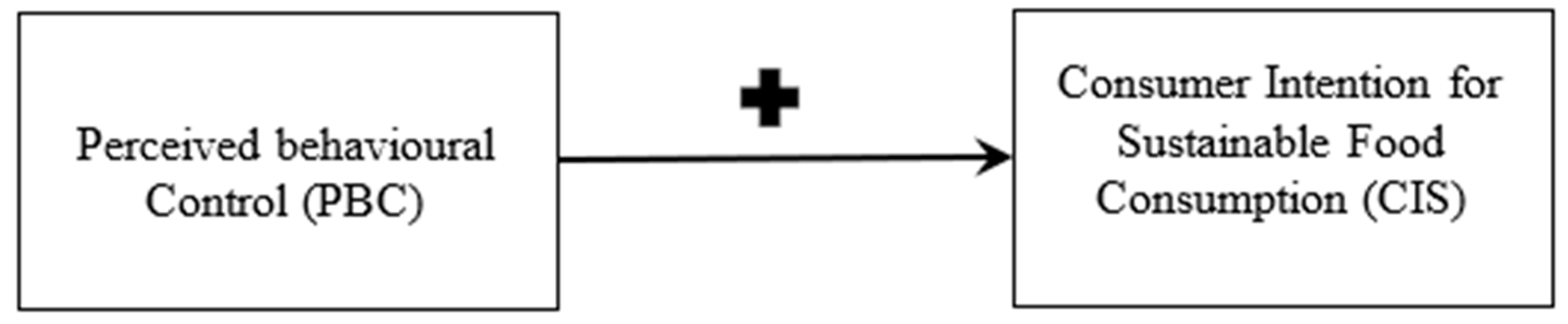

3.5.3. The Role of Perceived Behavioural Control in Shaping CIS

Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC), a key component of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), reflecting an individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty in performing a behaviour (Ajzen, 1985; Shen et al., 2022). PBC is shaped by control beliefs, which assess the availability of resources, opportunities, and the perceived influence on behaviour (Hwang et al., 2020). Beyond resource availability, PBC encapsulates the perceived feasibility and significance of those resources in achieving intended behaviours (Mead & Irish, 2022). PBC captures the challenges in adopting sustainable practices, such as navigating eco-labels and sourcing sustainable products, which directly influence intentions (Huang et al., 2024). Thus, the following relation is proposed (see

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Impact of PBC on CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 8.

Impact of PBC on CIS. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

3.6. From Intentions to Behaviour: The Intricacies of Sustainable Consumption of Food

Intentions play a pivotal role in shaping behaviours (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Zanna, 2014). Studies indicate correlations ranging from 0.45 to 0.62 across various domains (Albarracín, 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020; Wu & Chen, 2014). As per Ajzen (1985), intentions are the immediate determinant of human behaviour, i.e.

where,

Both, attitudes based on behaviour

and

have their relative weights

. Therefore,

where attitudes are shaped by the underlying beliefs of individuals. So,

SN are the function of beliefs called normative beliefs and the motivation provided by the referents, as presented in the following equation 04.

Putting the values of (3) and (4) in (2)

Putting the value of (5) in (1)

Based upon expression 6, Ajzen (1985) posits that intentions drive behaviour, shaped by behavioural beliefs, outcome evaluations, normative beliefs, and motivation, with varying weights and . It predicts behaviour accurately only, when under volitional control.

Addressing the Element of Non-Volitional Control

To address conundrum of non-volitional control Ajzen (1985) extends TRA by incorporating behavioural control. It posits that actual behaviour results from both behavioural intention and control. Hence,

As we already know from expression (2) behaviour is the sum of behavioural attitude and subjective norms, putting the values from equation (2) into (7).

In contrast to the TRA as in expression (3), TPB suggested that Attitude towards the behaviour is dependent upon the following as mentioned in expression (8)

In addition, the subjective norms for the behavioural attempt will be

Now, putting the values of (8) and (9) in (7)

Further expanding the expression to the belief and motivational level by switching values from (3) and (4) in (10)

From (11) it is clear that the behaviour is the function of attitudes and subjective norms. The element of control is also very important, however, at times given the practical constraints it is not feasible to measure the actual level of control (Reis et al., 2023). Hence, in such situations the perceived behavioural control of the consumer could be measured to analyse its impact on the formation of behavioural intention (Du et al., 2022; Reis et al., 2023); which is also proposed by the study (see

Figure 7). Based upon equations 1-11 embedded in theory of reasoned action (TRA) and TPB it has been established that the immediate predecessor of behaviours is behavioural intentions which are influenced by ASFC, CIS and PBC where ASFC is influenced by CPR and CPA. Consequently, the following relations R6,7&8 emerged (see

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11):

Figure 9.

Mediation of Intentions between Attitude and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 9.

Mediation of Intentions between Attitude and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 10.

Mediation of Intentions between Subjective Norms and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 10.

Mediation of Intentions between Subjective Norms and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 11.

Mediation of Intentions between Perceived Behavioral Control and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 11.

Mediation of Intentions between Perceived Behavioral Control and Behavior. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

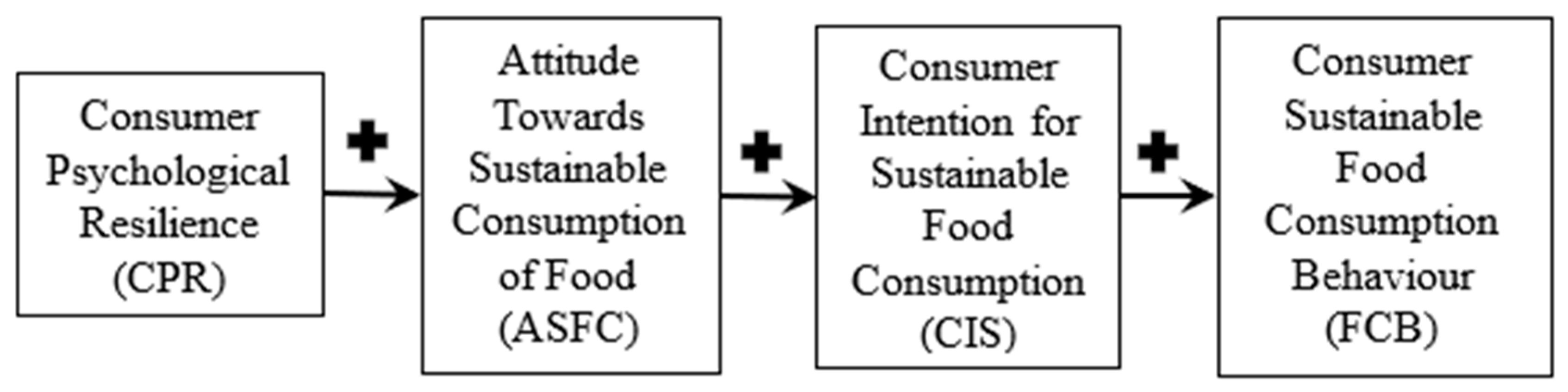

3.7. From Psychological Resilience and Adaptability to Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviour

As established previously, for any behaviour to be executed there is a chain of processes that gains the momentum that is ultimately translated into the action (also see equation 11). Starting from underlying beliefs and motivations to attitudes, attitudes to intentions, and intentions to behaviour. Given what has been said and expressed in R1-8, where the impact of the CPR and CPA has been elaborated on the formation of ASFC and then with the influence of ASFC and SN in the presence of PBC the intentions are formed to be translated into behaviours.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) underlies research indicating that attitudes towards sustainability influence consumer intentions, which predict sustainable food choices (Alam et al., 2020; Qi & Ploeger, 2021; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). Psychological resilience has also been shown to help people maintain sustainable attitudes in the face of external pressure (Gazdecki et al., 2021; Whatnall et al., 2019; Zanatta et al., 2022). We apply this logic and the previous elaborations to suggest a sequential mediation pathway for sustainable food consumption. Also, adaptability has been identified as critical for behavioral transitions under conditions for which sustainable decision making is required (Bodenheimer, 2018; Loorbach, 2007). By being more adaptable, individuals are more likely to foster positive attitudes on sustainable consumption which influence their intention and actual behaviours. Hence, based on the premise the following relations R9 &10 are proposed. (see.

Figure 12 &

Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Sequential mediation of ASFC and CIS between CPR and FCB. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 12.

Sequential mediation of ASFC and CIS between CPR and FCB. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 13.

Sequential mediation of ASFC and CIS between CPR and FCB. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Figure 13.

Sequential mediation of ASFC and CIS between CPR and FCB. Note. This figure is designed by author for the study.

Because of the limited availability of direct empirical validation of what was proposed, the hypotheses of this study are theoretically-induced, specifically derived from realizing a systematic synthesis of literature on resilience, adaptability, and sustainable consumer behaviour. Combining CPR and CPA with TPB and SES serves as a novel conceptual framework that should be tested empirically in future research. As recommended in

Section 6, this study attempts to lay the theoretical groundwork for such validation. Based upon the relationships R1-R10 and

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, a comprehensive theoretical research framework has been devised (see

Figure 14) to understand the intricacies of consumer sustainable food consumption behaviour.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Integration

Adapting Social-Ecological Systems (SES) theory, which is frequently used at the macro-system level, to the individual consumer context must be explicitly justified. SES theory was introduced with resilience and adaptability as higher-order system characteristics fundamental for negotiating environmental shocks and conserving ecological stability (Cinner & Barnes, 2019; Li et al., 2020). This paper introduces the constructs of CPR and CPA in a novel fashion such that pioneering in applying the constructs to individual consumer behaviours.

The theoretical basis for this transformation is the understanding that individual consumers are parts of larger social-ecological systems, which means that system sustainability, includes behavioral contributions of individuals (Čapienė et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2023). Similar to the capacity of resilience and adaptability at the macro-level, which allows societies or ecosystems to cope with disturbances more effectively (Folke, 2016), individual-level resilience (CPR)—the ability to withstand stressors—and adaptability (CPA) are psychological capacities that help consumers to cope with external pressures (e.g., false advertisement, economic limitations) while gradually shifting their behaviours towards sustainability.

Moreover, considering that consumer behaviours are often embedded in wider ecological and market conditions, adopting SES within consumer psychology strengthens the analytical framework by bridging individual psychological processes and ecological facts. Therefore, SES principles operating at the individual level do not diminish their theoretical coherence but rather broaden their explanatory capacity by integrating individual actors into the dynamic complexity of their environmental contexts. This theoretical bridging provides an explicit response to recent calls within the academic literature for integrative frameworks capable of addressing the multi-level nature of sustainability challenges (Ahmed et al., 2019; El Bilali, 2020; Toussaint et al., 2022).

CPR helps sustain practices under adversity, while CPA enables dynamic adaptation to challenges (Azam et al., 2024; Kahiluoto, 2020; Michel-Villarreal, 2022). This combination offers a comprehensive lens for analyzing and promoting FCB amidst evolving environmental and market contexts. Therefore, the integration of SES and TPB provides the robust theoretical basis to address challenges of fostering sustainable food consumption. SES emphasizes that resilience and adaptability are critical attributes for maintaining system functionality amid disruptions. As Folke et al. (2010) and Melton (2023) highlighted that resilience connects ecological and social dimensions to foster adaptive capacity, enabling systems to maintain core functions during periods of change. Similarly, Hertel et al. (2021) and Walker et al. (2004) emphasize that resilience allows systems to absorb shocks and recover functionality effectively. Traditionally applied at the macro-system level, SES principles are contextualized in this study at the individual level through CPR and CPA. This operationalization bridges a critical gap, aligning ecological and behavioural insights to explain consumer decision-making in the face of socio-environmental pressures.

TPB encapsulates attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behaviour control to be the predictors of intentions (Alam et al., 2024). Yet, TPB’s explanatory power is limited by its confined consideration of external barriers faced by the consumers e.g. affordability or misinformation. Klöckner (2013) and Qin and Song (2022) argue that TPB underestimates external constraints, limiting understanding of complex consumer environments. The framework integrates CPR and CPA with TPB to address barriers through psychological capacities. This integration strengthens TPB’s predictive accuracy while enhancing its relevance in sustainability research, as recently noted by Tridapalli and Elliott (2023)

Although the integration of SES and TPB based upon the inclusion of CPR and CPA provides a strong theoretical base, the use of such psychological domains may vary notably on the basis of cultural norms and socio economic environment (Heyes, 2024; Sng et al., 2018). Due to cultural frames, availability of income, and resources; past research demonstrates that resilience and adaptability are culture contingent (Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Vieira et al., 2018). Consumers with a higher socioeconomic background may find it easier to adapt given more options for sustainable products but consumers from less affluent contexts might have to become more resilient to maintain the pro-environmental behaviours despite lack of income or being overinformed (Krsnik & Erjavec, 2024; Zhong et al., 2024). Consequently, there should be explicit consideration of cross-cultural and socio-economic dimensions in the future empirical validation of the proposed integrated framework, to usefully inform our understanding in diverse contexts.

4.1.1. Operationalizing CPR and CPA

Although this paper primarily conceptually integrates CPR and CPA into SES and TPB, operationalising these constructs for future empirical validation is desirable. Rooted in the extant literature on psychological resilience (e.g. Reivich & Shatté, 2002; Rew & Minor, 2018), CPR could be operationalized through established psychological scales intended to measure individual resilience to outside stresses, emotion regulation skills, cognitive flexibility, and optimism. Examples of questionnaire tools to measure resilience include the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) by Connor and Davidson (2003) or the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) by Friborg et al. (2003), as established measures of individual psychological resilience

Similarly, CPA can be realized as scales measuring an individual’s readiness to adopt changes in external environments or market fluctuations. Ployhart and Bliese (2006) developed the individual adaptability measure (I-ADAPT), which assesses the adaptability constructs of flexibility in regard to problem-solving, openness to change, and changing behaviours according to new information or constraints. Additionally, Fielding et al. (2008) also presented a scale measuring adaptability. The adoption or adaptation of these validated scales for CPR and CPA in future empirical studies will serve to support methodological rigour and enable the precise measurement of these constructs in a wider range of sustainability contexts.

4.2. Alignment with Existing Literature

Attempted integration of resilience and adaptability to sustainable consumption expands prior research. The role of resilience in enabling systems to endure shocks and recover has been underscored by existing studies (e.g. Fazey, 2021; Meuwissen et al., 2021). Based on these insights, this study illustrates how CPR helps people to continue sustainable behaviour despite affordability challenges or misleading marketing. More resilient consumers are cognitively flexible and optimistic, prioritizing long term environmental benefits over short term conveniences (Kursan Milaković, 2021).

These findings complement CPA by examining dynamic external conditions. Although it has been recognized that adaptability is critical for responding to environmental changes, its application at the level of the individual consumer has not been studied (Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Vargas-Merino et al., 2023). According to Lee et al. (2014), adaptability enables consumers to make more informed decisions about purchasing products in resource scarce periods or with regards to regulatory changes. This framework operationalizes CPA in order to show how consumers are conditioned to adapt their behaviour as a result of market disruptions. E.g. during meat shortages and price hikes consumers adopt plant-based diets. This aligns with the findings of Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) who indicate that adaptable consumers are more behaviourally flexible and are able to overcome sustainability challenges.

Although TPB is widely used to study human behaviour however, it has failed to consider the dynamic external forces. Therefore, this study has integrated CPA and CPR to address the said limitations and to offer holistic framework for consumer decision making. Similar problems were highlighted in the works of the previous authors including but not limited to Gupta and Ogden (2009); Miceli et al. (2021) and Suriyankietkaew et al., (2022). It has been argued that resilience-focused constructs enhance the applicability of the TPB framework in sustainability contexts. The frameworks based upon these constructs could go beyond the rationality-based models and can offer a more holistic understanding of consumer behaviour. Furthermore, the operationalization of SES principles at individual level will enable to fill the critical gap in research by demonstrating how resilience and adaptability drives sustainable consumption behaviours.

The integration of CPR and CPA based upon SES into the TPB framework presents unique theoretical contributions compared to prior studies in the sustainable consumption literature. While existing studies recognize resilience as a way of coping with disruptions (Fazey, 2021; Meuwissen et al., 2021) and adaptability as essential for accommodating changes (Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Lema-Blanco et al., 2023), these constructs are almost exclusively examined separately at macro or community levels. Studies such as Gupta and Ogden (2009), Miceli et al. (2021) and Suriyankietkaew et al. (2022); despite critiques of TPB authors have not yet integrated psychological constructs of SES theory through an individual consumer lens and applied them to individual-level assessments among consumers. Building on previous research, this study provides a novel individual-level perspective of the TPB by directly integrating CPR and CPA to operationalize SES concepts, bridging mental and ecological aspects into one model. Such novel integration contributes to deepening the theoretical basis and augmenting the predictive validity of TPB, offering thus more comprehensive explanation for sustainable consumer actions.

4.3. Framework Contributions

A substantial contribution to sustainability research is the inclusion of SES theory-based constructs of CPR and CPA as extensions to TPB framework. Although SES framework is generally used at the macro levels to evaluate the system’s adaptation and resilience (Schäufele-Elbers & Janssen, 2023), this study innovatively operationalizes the SES principles in the context of sustainable food consumption behaviour at the individual levels. Consequently, in in-lined with Kenny et al. (2023), this integration extends and enriches this view by combining ecological understanding and psychological drivers to explain why resilience and adaptability matter to consumer decision making.

In order to address the critiques of TPB’s narrow focus on external constraints (Kovacs & Keresztes, 2022; Shen et al., 2022); integration of CPR and CPA has enhanced the predictive capacity of TPB. The practical relevance of TPB is strengthened by the emergence of positive feedback mechanisms grounded in CPA. At the same time, CPR helps maintaining sustainable behaviour in the face of socio-environmental barriers (Gupta & Ogden, 2009; Klöckner, 2013). CPR and CPA together improve the capability of the framework to explain the formation and execution of behaviours in complex and challenging situations.

The contributions of this framework are further broadened by applying SES principles at the individual level. Framed as such, the proposed framework connects these constructs to TPB and better reflects the complex mutual influence of ecological, psychological, and cognitive influences that ultimately define sustainable food consumption behaviour. Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) note that integrative frameworks are needed to move sustainability research forward. These frameworks have both theoretical depth and are practically applicable. Thus, study delivers a solid basis upon which future empirical work in diverse sustainability contexts can be developed.

5. Policy Implications

Integrating constructs of CPR, CPA, with SES and TPB provides a conceptual framework highlighting suitable intervention points to promote more eco-sustainable food consumption behaviours. Studies have referred and identified that consumers are more receptive of sustainable consumption messages and incentives if they are resilient and adaptable (Azam et al., 2024; Masud et al., 2016; Pelletier et al., 1998). As a result, policy options proposed in this paper implicitly focus on improving CPR and CPA capacity among consumers, thus directly supporting the attitudinal (ASFC) and intentional (CIS) pathways traced within this study.

Education efforts need to focus specifically on consumer groups that are most impacted by affordability and misinformation barriers. Workshops and interactive online courses about interpreting eco-labels, understanding and contextualizing the environmental impacts of dietary choices, and developing the means to adapt should be offered (De-loyde et al., 2025; Potter et al., 2021). Novel approaches to delivering information via community seminars, interactive digital platforms, and social media campaigns may present opportunities to engage with a wide variety of the population, especially those who are older, students and those living in economically less-privileged areas will assist sustainable consumption behaviours (Bryła et al., 2022; Iliopoulou et al., 2024). Policymakers would be able to test and improve these educational initiatives over time to produce sustainable impact using assessment from pre- and post-program surveys or behavioural tracking studies.

With respect to incentives, policy-makers could try targeted subsidies or tax reductions for eco-labelled or sustainably sourced food items, thus addressing affordability constraints (Bastounis et al., 2021; Taillie et al., 2024). Direct subsidies to retailers selling sustainable options, for instance, could lower prices for consumers, increasing access to sustainable choices (Tarola & Vergari, 2024). Consumer-facing loyalty or reward programs could also encourage continued sustainable purchasing behaviour. For large-scale implementation, feasibility studies will need to assess the sustainability of these incentive schemes and their acceptance among stakeholders. Their impact can be measured through pilot programs, leading to important insights as to how consumers are changing as they work through sustainable consumption choices.

Standardized and clearly communicated eco-labels must be established and mandated to verify claims, with the help of authorities that are both independent and trusted (Tiboni-Oschilewski et al., 2024). Developing certifying systems that are made transparent, together with independent audits, can considerably increase consumer confidence in sustainable labels and eco-friendly claims (Damberg et al., 2024). Public information campaigns and specific platforms for certified and standardized information may also help consumers make trusted and consistent choices when choosing sustainable products (Morone et al., 2021). Monitoring consumer feedback and evaluations regularly can maintain effectiveness and credibility of these information dissemination strategies.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

The study points to the importance of CPR for sustainable consumption practices when consumers are exposed to adversities and the importance of CPA for the management of such changes and volatility. CPA gives consumers the opportunity to face extensive pressures including affordability and misinformation etc. The study has examined psychological antecedents of sustainable consumption behaviour, particularly from extrinsic and intrinsic perspective. Furthermore, the framework has also provided an application of the SES principles at a level lower than the system level, and offered guidance for simulating and understanding consumer’s sustainable behaviour change.

CPR and CPA has been integrated, thus providing the possibility of empirical testing in diverse areas of research including sustainable consumption. This framework should be extended to future research, along with cross-validation of the hypothesized model. This involves the application of the comparisons in the cross-cultural settings using data analytics techniques to develop further insights on sustainable consumption. In addition to offering this sustainability perspective, this framework provides the policy makers and businesses with a way to design interventions for sustainable consumption behaviour; enabling consumers to use their resilience and adaptability for a sustainable behaviour in the long run.

In addition, for suture researchers it would be of interest to explore methodologies to expand the framework and empirically demonstrate it. Quantitative approaches, for example, surveys or experimental designs, could therefore be tested for the effects of CPR and CPA on the respective attitudes, intention and behaviours. These same variables need to be demonstrated in diverse socio-environmental spheres, which are best done with longitudinal studies. A second dimension is that policy-oriented research should investigate the strategies and implications of how consistency between government and organizational strategy increases consumer resiliency and consumer adaptability. For example, campaigning for eco-labelled products or for plant-based diets might demand adaptive behaviour etc. The possible extension of this framework to energy use or waste management is also possible given the broad applicability of CPR and CPA (Ceschi et al., 2021; Lema-Blanco et al., 2023).

The scope of this paper is limited to being a conceptual paper and future research needs to test the proposed framework empirically in diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts. Cultural drivers e.g., collectivism vs individualism, societal norms and economic constrains etc. can also play substantially into drivers of resilience and adaptation. Therefore, future empirical research should perform comparative cross-cultural studies to compare the impact of different contexts (e.g., developed vs. developing regions; collectivist vs. individualist societies) on the relationships proposed in this framework. Not only will these analyses confirm the generalizability of the model, but they will also uncover actionable solutions targeted at specific consumer groups, which will enhance the practical relevance of SES and TPB integration.

Future studies are encouraged to empirically examine how cultural values, socio-economic status, and regional differences shape the relationships among CPR, CPA, and sustainable food consumption, thereby further refining the model. Further, artificial and digital twin technology represents another future prospect of exploration such that they hold the ability to capture real time consumer data and offer accurate predictive insights. Therefore, this can be refined into personalized interventions to promote sustainable consumption behaviour (Haider et al., 2022). These avenues will validate the framework and will offer deep sustainability insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the readability of the paper. After utilizing this tool, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

Notes

| 1 |

B = behaviour; I = intentions |

| 2 |

= attitude based upon that behaviour;

= subjective norms

|

| 3 |

bi = behavioural beliefs; ei = evaluation of outcomes |

| 4 |

bj = subjective beliefs; mj = motivations based upon beliefs |

| 5 |

= behavioural control; = behavioural attempt

|

| 6 |

= behavioural intention based upon attempted behaviour;= attitude towards attempted behaviour;= subjective norms related to attempted behaviours

|

| 7 |

;= Attitude based upon success;= Attitude based upon failure;= subjective probability of success;= subjective probability of failure

|

| 8 |

= Subjective Norms related to attempted behaviours;= referent’s perceived probability of success and 0

|

References

- Abdullahi, U.; Mohamed, A. M.; Senasi, V. Exploring global trends of research on organizational resilience and sustainability: a bibliometric review. Journal of International Studies 2023, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaibi, C. E.; & Wilson, J. P.; Wilson, J. P. Trauma, PTSD, and Resilience: A Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2005, 6, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, N. R. , Ark, P., & Byers, J. Resilience and coping strategies in adolescents – additional content. Paediatric Care 2008, 20, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. , Downs, S., & Fanzo, J. Advancing an Integrative Framework to Evaluate Sustainability in National Dietary Guidelines. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmadi, P. , Rahimian, M., & Movahed, R. G. Theory of planned behavior to predict consumer behavior in using products irrigated with purified wastewater in Iran consumer. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1985a). From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1985b). From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L. Consumer scapegoatism and limits to green consumerism. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 63, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A. , Mohamad, Mohd. R., Yaacob, Mohd. R. B., & Mohiuddin, M. Intention and behavior towards green consumption among low-income households. Journal of Environmental Management 2018, 227, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. S. , Ahmad, M., Ho, Y.-H., Omar, N. A., & Lin, C.-Y. Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Sustainable Food Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. S. , Ho, Y.-H., Ahmed, S., & Lin, C.-Y. Predicting Eco-labeled Product Buying Behavior in an Emerging Economy through an Extension of Theory of Planned Behavior. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental 2024, 18, e6220–e6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, I. A. , Martin Fishbein, Sophie Lohmann, Dolores. (2018). The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes, Volume 1: Basic Principles (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Al-Daher, H. Criminal Consequences of Unsustainable Food Systems: Ethical Issues and Future Prospects. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies 2023, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sultan, S. , Almousa, M., & Aloud, A. Determinants of Food Ordering Applications Adoption among Saudi Consumers and their Effect on Dietary Habits. American Journal of Health Behavior 2024, 48, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C. J. , & Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnal Sarasa, M. , de Castro Pericacho, C., & Martín Martín, M. P. Consumption as a social integration strategy in times of crisis: The case of vulnerable households. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2020, 44, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaduzzaman, M. , Jebarajakirthy, C., Weaven, S. K., Maseeh, H. I., Das, M., & Pentecost, R. Predicting collaborative consumption behaviour: A meta-analytic path analysis on the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Marketing 2022, 56, 968–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayar, I. , & Gürbüz, A. Sustainable Consumption Intentions of Consumers in Turkey: A Research Within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211047563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, H. , Muhamad, N., & Syazwan Ab Talib, M. A review of psychological resilience: Paving the path for sustainable consumption. Cogent Business & Management 2024, 11, 2408436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C. , Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsa, A. B. , & Schlegelmilch, B. B. Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: Insights from a systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 245, 118902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A. M. , Grappi, S., & Romani, S. Investigating environmentally sustainable consumption: A diary study of home-based consumption behaviors. Business Strategy and the Environment 2024, 33, 6275–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastounis, A. , Buckell, J., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Cook, B., King, S., Potter, C., Bianchi, F., Rayner, M., & Jebb, S. A. The Impact of Environmental Sustainability Labels on Willingness-to-Pay for Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Discrete Choice Experiments. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F. , & Leary, M. R. Writing Narrative Literature Reviews. Review of General Psychology 1997, 1, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The Effect of Empathy in Environmental Moral Reasoning. Environment and Behavior 2010, 42, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. , & Ross, H. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Society & Natural Resources 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S. H. , Saleem, F., Zakariya, R., & Ahmad, A. The determinants of food waste behavior in young consumers in a developing country. British Food Journal 2019, 125, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasini, B. , Rosi, A., Giopp, F., Turgut, R., Scazzina, F., & Menozzi, D. Understanding, promoting and predicting sustainable diets: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 111, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, M. (2018). Beyond technology: Towards sustainability through behavioral transitions (Working Paper S05/2018). Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobalan, K. , & Nachimuthu, G. S. Organic consumerism: A comparison between India and the USA. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 53, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B. , Szymkowiak, A., Horska, E., Raszka, N., & Żelichowska, E. Towards Building Sustainable Consumption: A Study of Second-Hand Buying Intentions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossel, H.; (1999). Indicators for sustainable development: Theory, method, applications. International Institute for Sustainable Development Winnipeg. Available online: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/300/iisd/measurement_assessment/indicators/balatonreport.pdf.

- Bouman, T. , Verschoor, M., Albers, C. J., Böhm, G., Fisher, S. D., Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., & Steg, L. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Global Environmental Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. , Chatterjee, S., & Ciabiada-Bryła, B. The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Consumer Engagement in Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 16637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, J. , Rajh, E., Slijepčević, S., & Škrinjarić, B. Conceptual Research Framework of Consumer Resilience to Privacy Violation Online. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R. , Hielscher, S., & Light, A. Collaboration, creativity, conflict and chaos: Doing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustainability Science 2020, 15, 1711–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, L. S., Carneiro, G., Monteiro, M., & Abreu, F. B. e. (2019). Towards the Use of Machine Learning Algorithms to Enhance the Effectiveness of Search Strings in Secondary Studies. Proceedings of the XXXIII Brazilian Symposium on Software Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Čapienė, A. , Rūtelionė, A., & Krukowski, K. Engaging in Sustainable Consumption: Exploring the Influence of Environmental Attitudes, Values, Personal Norms, and Perceived Responsibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapienė, A. , Rūtelionė, A., & Tvaronavičienė, M. Pro-Environmental and Pro-Social Engagement in Sustainable Consumption: Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschi, A. , Sartori, R., Dickert, S., Scalco, A., Tur, E. M., Tommasi, F., & Delfini, K. Testing a norm-based policy for waste management: An agent-based modeling simulation on nudging recycling behavior. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 294, 112938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K. Characteristics of systematic reviews in the social sciences. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 2021, 47, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Behavioral Economics: Understanding the Psychological Factors Driving Consumer Decisions. International Journal of Global Economics and Management 2024, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Predicting College Students’ Bike-Sharing Intentions Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. , & Türe, M. Blame work and the scapegoating mechanism in market status-quo. Journal of Business Research 2022, 144, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J. E. , & Barnes, M. L. Social Dimensions of Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. One Earth 2019, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V. , & Braun, V. Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoker, E. N. , & van der Linden, S. Fleshing out the theory of planned of behavior: Meat consumption as an environmentally significant behavior. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K. M. , & Davidson, J. R. T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, P. (2023). Systematic Review Research in Marketing Scholarship: Optimizing Rigor. International Journal of Market Research. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J. , Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Magni, P. A., & Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching 2020, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha Ramos, L. A. , Zecca, F., & Del Regno, C. Needs of Sustainable Food Consumption in the Pandemic Era: First Results of Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damberg, S. , Saari, U. A., Fritz, M., Dlugoborskyte, V., & Božič, K. Consumers’ purchase behavior of Cradle to Cradle Certified® products—The role of trust and supply chain transparency. Business Strategy and the Environment 2024, 33, 8280–8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. L. , Jacobson, C., Lyth, A., Dedekorkut-Howes, A., Baldwin, C. L., Ellison, J. C., Holbrook, N. J., Howes, M. J., Serrao-Neumann, S., Singh-Peterson, L., & Smith, T. F. Interrogating resilience: Toward a typology to improve its operationalization. Ecology and Society 2016, 21, art27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, U. R. , Gomes, T. S. M., de Oliveira, G. G., de Abreu, J. C. A., Oliveira, M. A., da Silva César, A., & Aprigliano Fernandes, V. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-loyde, K. , Pilling, M. A., Thornton, A., Spencer, G., & Maynard, O. M. Promoting sustainable diets using eco-labelling and social nudges: A randomised online experiment. Behavioural Public Policy 2025, 9, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demski, C. , Capstick, S., Pidgeon, N., Sposato, R. G., & Spence, A. Experience of extreme weather affects climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. Climatic Change 2017, 140, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, V. T. H. , & Do, L. T. Downward social comparison in explaining pro-environmental attitude-sustainable consumption behavior gap. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2024, 37, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M. N. , Wong-On-Wing, B., & Yang, D. Cross-Cultural Differences in Perceived Control Effectiveness: The Role of Cognition. Behavioral Research in Accounting 2022, 34, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H. Transition heuristic frameworks in research on agro-food sustainability transitions. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2020, 22, 1693–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in action 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fazey, C. Social dynamics of community resilience building in the face of climate change: The case of three Scottish communities. Sustainability Science 2021, 16, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I. , Fazey, J. A., Fischer, J., Sherren, K., Warren, J., Noss, R. F., & Dovers, S. R. Adaptive capacity and learning to learn as leverage for social–ecological resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2007, 5, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Olit, B. , Martín, J., & González, E. (2019). Systematized literature review on financial inclusion and exclusion in developed countries. International Journal of Bank Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Cunha, R. , & Missemer, A. The Hotelling rule in non-renewable resource economics: A reassessment. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique 2020, 53, 800–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K. S. , McDonald, R., & Louis, W. R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecology and Society 2016, 21, art44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. , Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecology and Society 2010, 15, art20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friborg, O. , Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Martinussen, M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 2003, 12, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazdecki, M. , Goryńska-Goldmann, E., Kiss, M., & Szakály, Z. Segmentation of Food Consumers Based on Their Sustainable Attitude. Energies 2021, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A. , & Islam, T. (2023). Factors leading to sustainable consumption behavior: An empirical investigation among millennial consumers. Kybernetes, ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A. , Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glandon, D. M. Measuring resilience is not enough; we must apply the research. Researchers and practitioners need a common language to make this happen. Ecology and Society 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Wilson, S. Consumption practices during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2022, 46, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T. , Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. , & Ogden, D. T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2009, 26, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Beyond Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science: An evaluation of the backward and forward citation coverage of 59 databases’ citation indices. Research Synthesis Methods 2024, 15, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R. , Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M. , Shannon, R., & Moschis, G. P. Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariem Brundtland, G. World Commission on environment and development. Environmental Policy and Law 1985, 14, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A. , Tojari, F., & Manouchehri, J. Relationship between psychological and personality traits with consumer behavior factors. Shenakht Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry 2023, 9, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. , & Sui, D. Investigating college students’ green food consumption intentions in China: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmler, V. L. , Kenney, A. W., Langley, S. D., Callahan, C. M., Gubbins, E. J., & Holder, S. Beyond a coefficient: An interactive process for achieving inter-rater consistency in qualitative coding. Qualitative Research 2022, 22, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, T. , Elouafi, I., Ewert, F., & Tanticharoen, M. (2021). Building Resilience to Vulnerabilities, Shocks and Stresses. [CrossRef]

- Heyes, C. Rethinking Norm Psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2024, 19, 12–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D. B. (2019). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Conducting Systematic Reviews in Sport, Exercise, and Physical Activity. [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. The Economics of Exhaustible Resources. Journal of Political Economy 1931, 39, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I. , Appolloni, A., Chirico, A., & Cheng, W. The role of the environmental dimension in the performance management system: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 293, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. , Solangi, Y. A., Magazzino, C., & Solangi, S. A. Evaluating the efficiency of green innovation and marketing strategies for long-term sustainability in the context of Environmental labeling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 450, 141870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. , Kim, I., & Gulzar, M. A. Understanding the Eco-Friendly Role of Drone Food Delivery Services: Deepening the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Rueda, N. , Guillén-Royo, M., & Guardiola, J. Pro-Environmental Behavior, Connectedness to Nature, and Wellbeing Dimensions among Granada Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, E. , Koronaki, E., Vlachvei, A., & Notta, O. From Knowledge to Action: The Power of Green Communication and Social Media Engagement in Sustainable Food Consumption. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J. U. , Thomas, G., & Albishri, N. A. From status to sustainability: How social influence and sustainability consciousness drive green purchase intentions in luxury restaurants. Acta Psychologica 2024, 251, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, D. , Dąbrowska, A. Z., Pachołek, B., & Sady, S. Behavioral Intention to Purchase Sustainable Food: Generation Z’s Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. , Chang, B. P. I., Hristov, H., Pravst, I., Profeta, A., & Millard, J. Changes in Food Consumption During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Consumer Survey Data From the First Lockdown Period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T. , Iqbal, S., Ayub, A., Fatima, T., & Rasool, Z. Promoting Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior through Sustainability Marketing: The Boundary Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Image. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. H. , Ready, E., & Pisor, A. C. Want climate-change adaptation? Evolutionary theory can help. American Journal of Human Biology 2021, 33, e23539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiluoto, H. Food systems for resilient futures. Food Security 2020, 12, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, T. , Woodside, J., Perry, I., & Harrington, J. Consumer attitudes and behaviors toward more sustainable diets: A scoping review. Nutrition Reviews 2023, 81, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T. C. , Taylor, J. R., & Ahmed, S. A. Ecologically Concerned Consumers: Who are They?: Ecologically concerned consumers CAN be identified. Journal of Marketing 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C. A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Global Environmental Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodden, B. (2020). The Ability to Adapt. In B. Kodden (Ed.), The Art of Sustainable Performance: A Model for Recruiting, Selection, and Professional Development (pp. 25–30). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A. N. , & Altan, M. U. A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainable Consumer Behaviours in the Context of Industry 4.0 (I4.0). Sustainability 2024, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, I. , & Keresztes, E. R. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Willingness to Pay for Credence Product Attributes of Sustainable Foods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsnik, S. , & Erjavec, K. Comprehensive Study on the Determinants of Green Behaviour of Slovenian Consumers: The Role of Marketing Communication, Lifestyle, Psychological, and Social Determinants. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T. , & Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursan Milaković, I. Purchase experience during the COVID-19 pandemic and social cognitive theory: The relevance of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability for purchase satisfaction and repurchase. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 45, 1425–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F. , & Dewitte, S. Cognitive Flexibility and Pro–Environmental Behaviour: A Multimethod Approach. European Journal of Personality 2019, 33, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. , Conklin, M., Cranage, D. A., & Lee, S. The role of perceived corporate social responsibility on providing healthful foods and nutrition information with health-consciousness as a moderator. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2014, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema-Blanco, I. , García-Mira, R., & Muñoz-Cantero, J.-M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]