1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most prevalent disorders among older adults, with over 55 million people worldwide suffering from dementia in 2025 [

1]. Chronic neuroinflammation can lead to neuronal damage and neurodegenerative diseases [

2]. Activated microglia can be a normal central nervous system response to damage, but chronic microglial activation leads to a pro-inflammatory state [

3]. Prospective population-based cohort studies indicate that serum levels of inflammatory markers are closely associated with dementia [

4]. The levels of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), arachidonic acid (AA), and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are elevated in the brain of cognitive impaired and AD patients compared to normal controls [

5,

6].

, These molecules can increase neuroinflammation in the brain with various mechanisms [

7]. Therefore, a complementary approach to treating neuroinflammation can be reducing dietary sources of inflammation. Lower intakes of dietary lipopolysaccharides (LPS), arachidonic acid (AA), and advanced glycation end products (AGEs)could decrease neuroinflammation and neuronal damage in the brain, and can be obtained by reducing foods containing the highest amounts of LPS, AA, and AGEs: These foods can enter the bloodstream and the brain, and also may contain high levels of saturated fatty acids, which may, over time, impair brain circulation.

This article discusses the mechanisms underlying the detrimental effects of LPS, AA, and AGE and hypothesizes that a reduction in the dietary intake of these molecules can both reduce risk of and treat cognitive impairment and AD.

2. LPS, Neuroinflammation, and Cognition

The potential sources of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) for humans are bacterial infection, colonic microbiota, and certain foods. For example, thin-crust cheese pizza can raise serum LPS 65 times in just a few hours [

8]. LPS is made up of about 80% of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. The terms LPS and endotoxin are used synonymously.

High levels of plasma LPS can trigger inflammatory immune activation, and LPS-induced inflammation is an initiator of inflammatory degeneration in AD [

9]. Consequently, LPS is implicated in increased progressive neurodegeneration in AD [

10]. Recent data clearly show that inflammatory immune activation in AD can have the capacity to increase the pathophysiology of AD [

6].

How LPS Increases Neuroinflammation

LPS can increase the production of three inflammatory cytokines: interleukin-1-beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα). AD patients had higher levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α than normal controls [

11]. LPS can stimulate astrocytes and microglia in the central nervous system to secrete cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, and interferon-gamma. Microglial activation preceded the apparent neuronal degeneration [

12]. Systemic inflammation triggered by LPS can induce microglial expression of IL-1β and can also increase neuronal apoptosis in the brain. Both peripheral and central inflammation can increase brain inflammation and neuronal death, increasing neurodegeneration [

13]. Microglia, activated by LPS can damage neurons via nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cytokines, and can lead to phagocytosis of synapses and neurons [

14]. In addition, LPS can express its neurotoxicity in the central nervous system by reducing neuron-specific neurofilaments and synaptic signaling proteins, promoting neurodegeneration [

15].

Toll-like receptor-4 is a surveillance receptor, triggering inflammation when LPS is present. In addition, higher circulating LPS levels increased toll-like receptor-4 protein expression two-fold (p<0.05). Higher LPS caused a significant increase in TNFα from 1 pg to 33 pg and IL-6 secretion from 2.7 ng/mL to 4.8 ng/mL [

16]. Nuclear factor kappa-B (NFқB) is clearly involved in this increase of cytokines because a NFқB inhibitor stopped the increase of IL-6.

Increases in IL-1β have been documented after LPS challenge. IL-1β can induce microglial proliferation, stimulate microglial expression of IL-6, and activate microglia. IL-1β may promote neurodegeneration through generation of ROS such as peroxynitrite, and also appears to be a mediator of apoptosis. Additional neurotoxic properties of IL-1β include blood-brain barrier damage and increased amyloid-β [

11].

LPS can contribute to early neuroinflammatory changes in AD by activating the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), which can amplify pro-inflammatory signaling and promote chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, particularly in brain regions sensitive to AD, such as the hippocampus [

17].

LPS Is Increased in the AD Brain

Recent investigations reported higher LPS levels in grey and white matter in brains from patients with AD, in comparison to those from participants free from dementia. Also, LPS was found to co-localize with Amyloid-β in amyloid plaques in AD brains [

18]. LPS is present and associated with white matter injury in AD [

4]. Another study reported three-fold higher LPS levels in the hippocampus of four AD brains compared to two age-matched control brains. In some advanced AD patients, the hippocampus exhibited up to a 26-fold increase in LPS concentration. Also, it was reported that plasma LPS levels were three-fold higher in 18 AD participants (mean 61 pg/mL) than in 18 healthy controls (mean 21 pg/mL). A Norwegian study also found increased levels of LPS in the hippocampus of patients with AD, compared to healthy age-matched controls [

4].

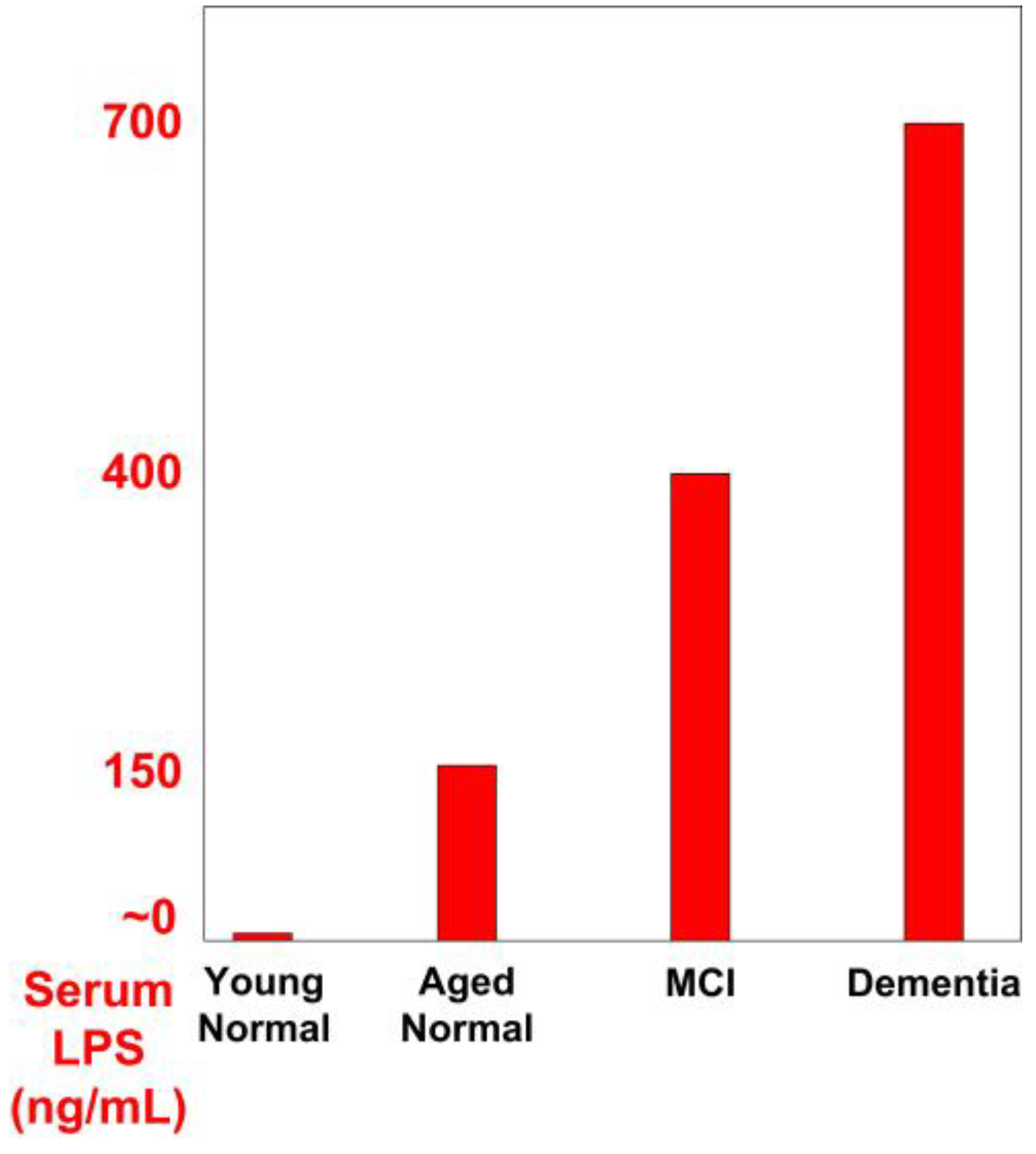

LPS was reported to be elevated in the blood and brain of AD patients [20]. Those with AD were found to have plasma LPS levels three times higher than controls [21]. In another study, subjects affected by mild cognitive impairment (MCI) had double the serum LPS levels, compared to normal aging controls. Also, those with dementia had almost double the serum LPS compared to MCI patients. Serum LPS was near zero in young normal people, 150 ng/mL in normal aged people, 400 ng/mL in patients affected by MCI, and 700 ng/mL in patients affected by dementia (

Figure 1) [22]. Another study confirmed that levels of LPS are increased in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with AD and in the serum of patients with MCI [23].

LPS Can Increase the Risk of AD and Cognitive Impairment

Higher plasma LPS has been correlated with cognitive decline and lower cognitive function: higher plasma LPS concentration can double the risk of MCI in participants without dementia [23].

LPS-induced inflammation may be a significant initiator of inflammatory degeneration in AD [4]. Systemic markers of inflammation, increased by LPS, are risk factors for late-onset AD. Microglial activation can be detected in around 50% of patients with MCI [24]. LPS can induce neuronal cell loss partly by greatly increasing TNFα and IL-1β [9]. Prospective population-based cohort studies indicated that higher serum levels of inflammatory markers can predict dementia [24].

LPS can infiltrate into the brain from the periphery and initiate the cascade of chronic neuroinflammatory reactions and neurodegenerative changes that can greatly increase risk of AD [7]. High levels of plasma LPS, via inflammatory immune activation, can have the capacity to facilitate and trigger the pathophysiology of AD [25]. Higher levels of lipopolysaccharide binding protein negatively impacted working memory/short-term verbal memory and the Digit Span Test [26]. In humans, low-dose LPS administration impaired both immediate and delayed recall [27].

LPS Can Work with Arachidonic Acid to Degrade Memory

Higher plasma LPS can degrade memory function partly due to arachidonic acid (AA) eicosanoid production, which is partially reversible with COX (cyclooxygenase) inhibitors [28]. Microglia treated with LPS produced 14 times the proinflammatory prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2), compared with untreated microglia. PGE2 from AA increases IL-6 inflammation [29]. Another study confirms that LPS can activate COX2 and increase production of ROS, for example, peroxides and superoxide [30].

How LPS from Food Can Enter the Bloodstream

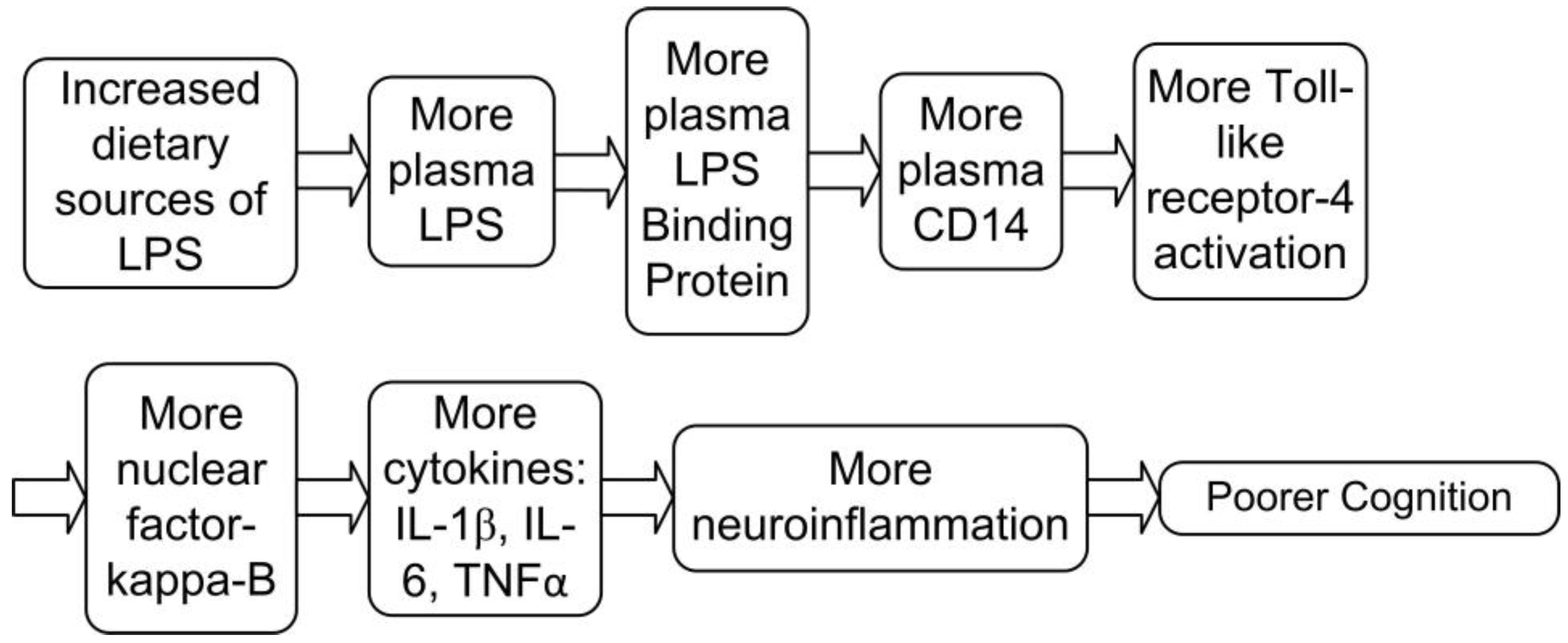

LPS is principally absorbed from certain foods after a meal, but can also enter the bloodstream from chronic dysbiosis (imbalanced gut bacteria), or infection [31]. Dietary LPS is absorbed and integrated into chylomicrons, which transport digested lipids into the bloodstream. Once LPS-laden chylomicrons are in the bloodstream, LPS is taken up by LPS binding protein (LBP), which is then transferred to the receptor

cluster of differentiation-14 (CD14). CD14 can bind the LPS-LBP complex to activate the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa-B (NFқB) via toll-like receptor-4. This signaling results in the release of a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα (

Figure 2) [31,32].

, It has been reported that excesses of these inflammatory cytokines can damage cognition.

Pro-inflammatory LPS co-absorbs with dietary saturated fatty acids, which increase intestinal absorption of LPS. Then, LPS is incorporated into chylomicrons, enters the bloodstream, and consequently contributes to postprandial endotoxemia and inflammation. LPS levels in chylomicrons increased from near zero up to half of a nanogram per milliliter after a high milk fat (40 g) meal. Milk fat triggered an early and sharp increase in LPS-laden chylomicrons at 60 min after ingestion [33]. High plasma LPS levels resulted in a robust cytokine response [34].

A recent study found that the largest dietary risk factor for AD was meat consumption [10]. LPS levels were found to be highest in beef, pork, and turkey. An average serving of turkey contains 67,000 ng LPS [35].

A study of toll-like receptors indicated that a processed food meal may contain an average of about 200,000 ng LPS [35]. Examples of processed food meals are included in

Table 1. By comparison, intravenous injection of only 49 ng LPS can impair verbal and nonverbal declarative memory functions and decrease immediate and delayed recall [36]. This suggests that the quantity of LPS in a processed food meal can be up to 4,000-fold higher than is required to damage memory, compared to LPS given by injection (

Table 1) [37].

Common foods can contain LPS, and the greatest concentrations were present in meat-based and cheese products. Unprocessed fruit, vegetables, grains, and potato are quite low in LPS [35].

Restricting dietary LPS could reduce plasma LPS levels to significantly reduce neuroinflammation [36]. On the other hand, higher intakes of fruit and legumes were associated with 34% and 20% less circulating LPS, respectively. Only fruit and legumes were significantly associated with lower LPS levels in a large prospective study with 912 participants. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was also significantly associated with lower circulating LPS when compared to a Western Diet [19,37].,

3. AGEs, Neuroinflammation, and Impaired Cognition

Animal-derived foods, when cooked at high heat, contain high levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Heating of proteins and lipids using methods such as frying, roasting, grilling, or baking stimulates AGE formation [38]. It has been proposed that AGEs can contribute to the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [5]. AGEs may increase oxidation and death of brain neurons. Cell death from oxidation of cellular membranes may be one of the neuropathological mechanisms of AD [39].

How AGEs Can Increase Neuroinflammation and Impair Cognition

RAGE (Receptor for advanced glycation end products) is located on the cell surface of cerebral vessels, neurons, and microglia, and serves as a receptor for AGEs and amyloid-β. RAGE can regulate amyloid-β transport across the blood–brain barrier and can increase its accumulation in the brain [40]. RAGE can activate a cascade of intracellular reactions leading to increased oxidative stress and the production of proinflammatory cytokines via the activation of NF-κB [41].

AGEs can contribute to memory impairment partially through RAGE-mediated mechanisms. When amyloid-β is crosslinked to AGEs, the amyloid-β is more toxic to neurons, compared to non-glycated amyloid-β [40]. Cognitive impairment and dementia may worsen when amyloid-β binds to AGEs. In this situation, there is an increase in ROS that can promote amyloid-β, senile plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles (tau tangles) [42]. Interactions between AGEs and amyloid-β and tau may be important in the pathogenesis of dementia and cognitive impairment [43].

The activation of RAGE by AGEs leads to an inflammatory cascade that begins with the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and the transcription factor NF-κB, a master regulator of proinflammatory genes [44,45]., This can increase inflammation through TNF-α, IL-6, and C-reactive protein. AGEs, by binding to RAGE, have been associated to an increase of neurodegeneration as well as atherosclerosis and stroke risk [46]. RAGE also can transport circulating amyloid-β across the blood–brain barrier, where the AGE-Amyloid-β interaction can lead to reduced cerebral blood flow [47].

AGEs in Food and Neuroinflammation

Limiting dietary AGE intake may lead to a decrease in inflammation and chronic diseases related to inflammatory status, such as AD. A reduction of dietary AGE intakes can lead to a reduction of inflammatory markers. In fact, five studies demonstrated a decrease in circulating concentrations of inflammatory indicators with a low-AGE diet [44]. Dietary restriction of AGEs can decrease the concentration of circulating AGEs [47]. A sustained reduction in dietary AGEs may result in effective suppression of inflammatory molecules [48]. It has been reported that AGE restriction can reduce inflammation in humans [49].

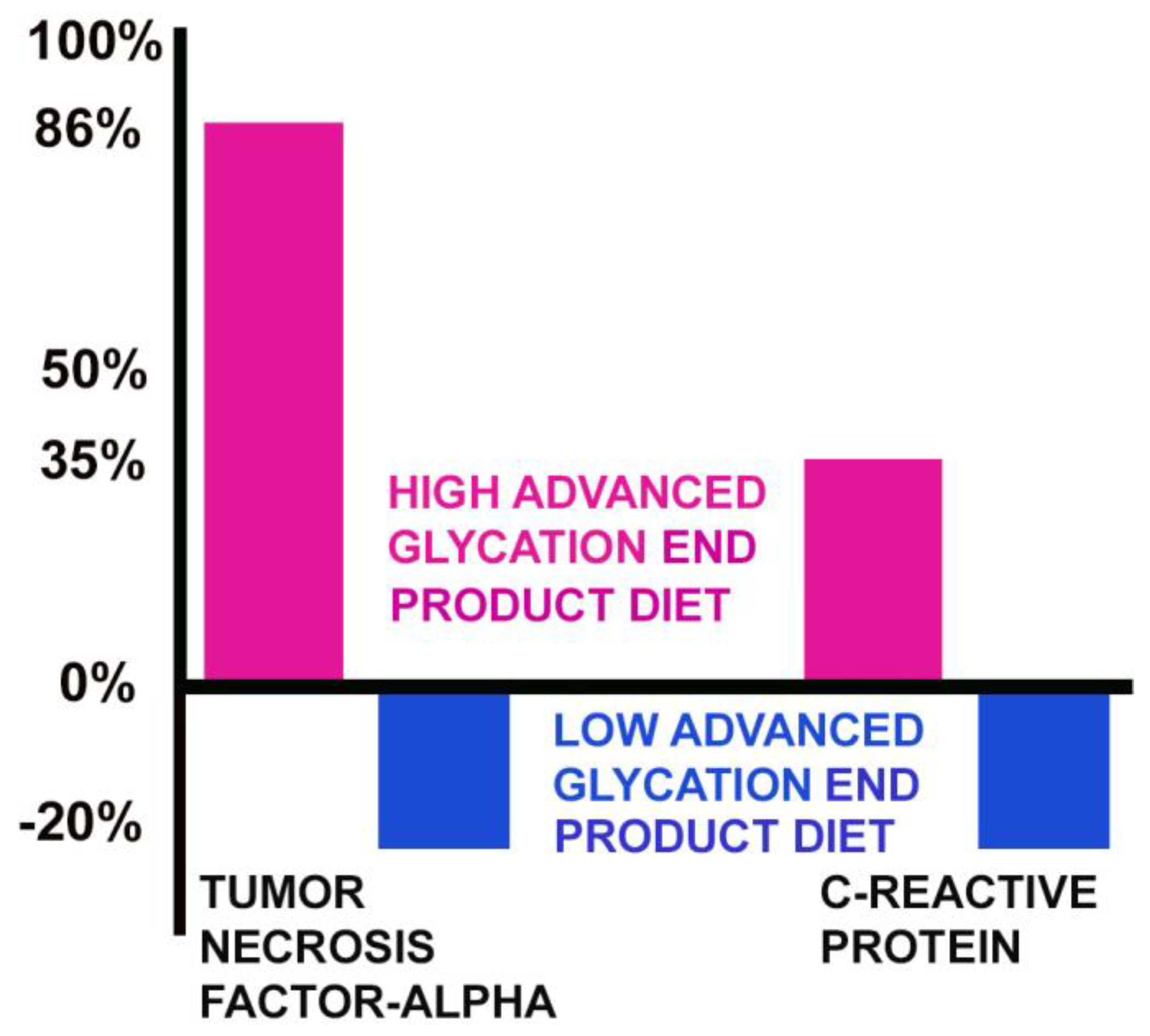

Moreover, the consumption of foods rich in AGEs can increase production of C-reactive protein and inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α [41]. After a dietary reduction of AGEs, a reduction in serum AGE concentrations is accompanied by a simultaneous reduction in markers of inflammation [50]. Conversely, a diet high in AGEs increased many inflammatory markers. Cytokines are inducible by AGEs via increased activation of NF-κB [46].

On a high AGE diet, the level of TNF-α increased by 86%, while the level of TNF-α decreased by 20% on a low AGE diet. C-reactive protein increased by 35% on a high AGE diet and was reduced by 20% on a low AGE diet (

Figure 3) [48].

AGEs Are Increased in the AD Brain

A higher AGE content has been consistently reported in amyloid-β plaques in AD brains, compared to normal brains [49]. Higher levels of AGEs can accelerate the accumulation of AGE-modified amyloid-β in cells and tissues [46]. The brains of AD patients typically contain a 5- to 10-fold greater number of amyloid plaques, compared to age-matched healthy controls [51].

AGE accumulation has been demonstrated in senile plaques in different cortical areas and in glial cells in the AD brain [45]. AGEs can increase the size of amyloid-β deposits. In AD patients, an increase of the percentage of AGE-damaged neurons (and AGE-damaged astroglia) with the progression of the disease has been reported [52]. AGE-modified amyloid-β was found to be more toxic than non-glycated amyloid-β to synaptic proteins [53]. AGEs were increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of subjects with AD. The decline in cognitive function in AD subjects correlated to protein glycation [54].

How AGEs from Food Can Enter the Bloodstream

About 10 percent of dietary AGEs are absorbed into the bloodstream, and two-thirds of absorbed AGEs are stored in tissues [5]. Once irreversibly cross-linked, AGEs are quite persistent [55]. This is why they are called “end products.” A low-AGE diet decreased serum AGEs by 30 percent, while a high-AGE diet increased serum AGEs by 65 percent in humans. The two diets were similar, other than their AGE content. Alterations in circulating AGEs occurred within 2 weeks of the diet change [48].

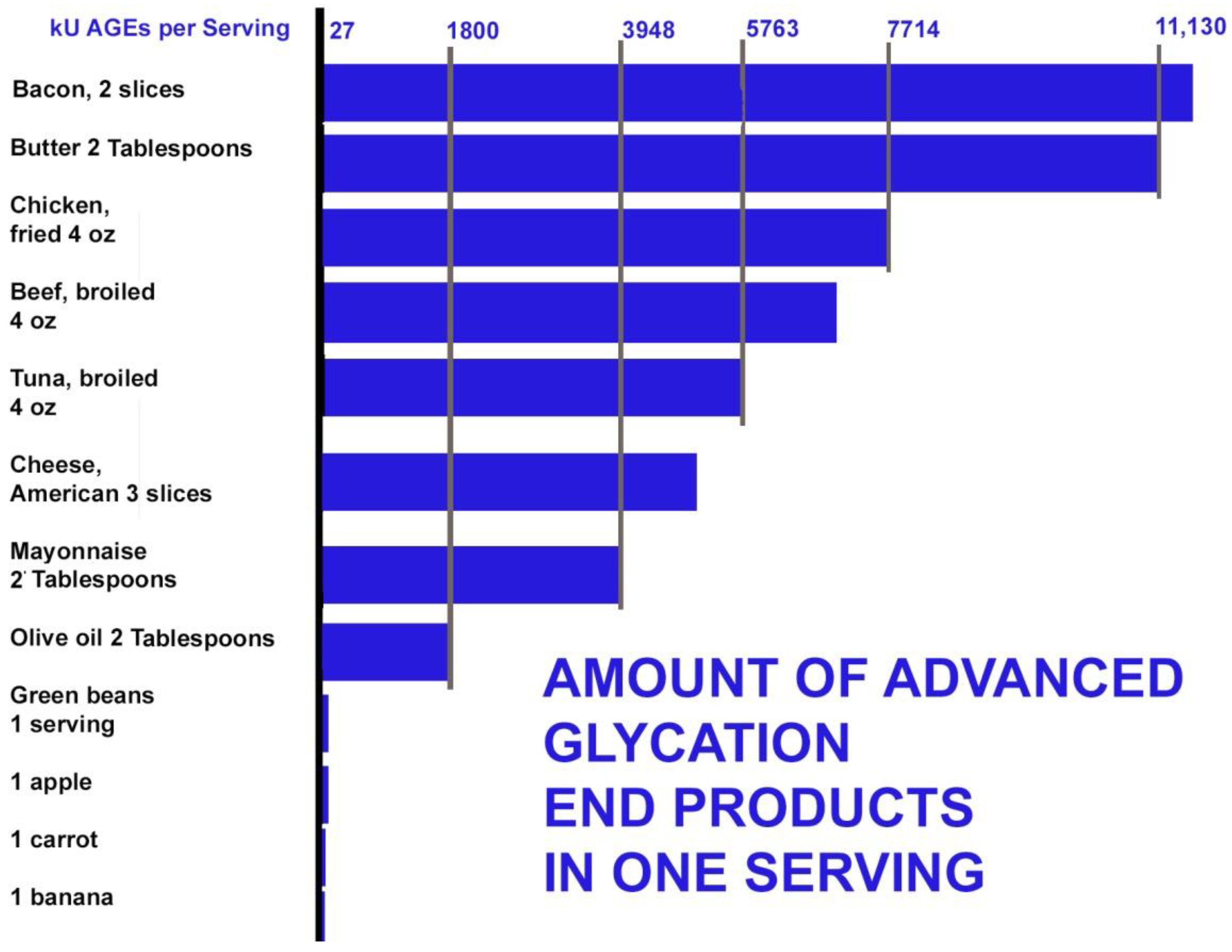

AGEs can be formed inside the body under conditions of oxidation and excess glucose. The highest dietary sources of AGEs were found in beef, cheese, poultry, pork, fish, and eggs. Butter also contains high levels of AGEs. The average dietary AGE intake in a cohort of normal adults from the New York City area was recently found to be 14,700 AGE kU/day (kU=kilounits). People who consume a diet rich in grilled or roasted meats can increase dietary AGE intake to more than 20,000 kU/day [56]. Meat alone can contribute 80% of dietary AGEs. Bacon contains extremely high levels of AGEs (11,905 kU/serving) [47]. By the 18th day following the Atkins diet, the level of methylglyoxal (an AGE precursor) was observed to increase sevenfold, leading to a large increase in AGEs [57].

Heating of proteins using methods such as frying, roasting, grilling, or baking food at high temperatures stimulates AGE formation by Schiff-base adducts and the Maillard reaction. Excessive AGE accumulation from these foods, cooked by these methods, may play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive disorders [38]. Water and antioxidants in whole plant foods can inhibit the formation of AGEs. Grains, fruits, and vegetables were generally found to be low in AGEs (under 28 kU/serving). Amounts of AGEs in some common foods are shown in

Figure 4 [58].

Dietary AGEs Increase Risk of AD and Cognitive Impairment

A reduced intake of food-derived AGEs has been considered an effective strategy to reduce risk of neurodegenerative diseases, and an association has been shown between high serum AGEs and cognitive decline [59]. It has been widely reported that lower levels of serum AGEs were associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline [60]. In a group of cognitively intact elder subjects, those with lower serum levels of methylglyoxal, an AGE precursor, showed a reduced rate of cognitive decline [52]. Among 4041 elderly Japanese, those with the highest AGE levels had the lowest cognitive scores, while those with the lowest levels of AGEs had the highest cognitive scores [61].

It has been reported that when AGE levels rose to just half of the highest AGE levels measured in healthy people, the risk of MCI rose 640% (OR=6.402), and this was after adjustment for age and brain atrophy measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Both brain atrophy and AGE content were significantly higher in patients with MCI [62]. In a large prospective study, higher levels of AGEs were associated with lower global cognitive function, and this effect was stronger for carriers of the apolipoprotein-ε4 allele. Conversely, lower AGEs were associated with better cognition in 2890 individuals in a Dutch study [42].

A recent 4-year study found that higher AGEs were found to be significantly associated with a worse clinical dementia rating, even after adjustment for age, sex, education level, and apolipoprotein ε4 status. Importantly, patients with lower AGEs exhibited a slower decline in cognition [63]. Each standard deviation increase of AGEs increased AD and dementia risk 21-22% [64].

4. Arachidonic Acid, Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Impairment

Arachidonic acid (AA) is an omega-6, 20-carbon chain with 4 points of desaturation (C20:4 ω-6). AA is the second most common fatty acid in the brain (after DHA), comprising about 20% of neuronal membrane fatty acids [65]. AA is needed in the brain and humans can make sufficient AA from linoleic acid. However, dietary AA can increase the content of AA in the membrane phospholipids to increase neuroinflammation [66].

How Excess Dietary AA Creates Neuroinflammation in AD

AAis released from neuronal cell membrane phospholipids by the enzyme phospholipase-A2 (PL-A2), and then converted by cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX1 and COX2) into prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2), which contributes to the occurrence and progression of neuroinflammation. COX-2 over-expression in the brain of AD patients has been reported and correlated with the progression of AD in several studies [67]. The finding of elevated levels of AA and PL-A2 in AD brains supports the hypothesis that there is an active inflammatory process occurring in AD. PL-A2 can contribute to the inflammatory effects of amyloid-β 1-42 peptide in astrocytes and microglial cells [68].

Microglia, when activated by LPS, can synthesize PGE2 when extra AA is available. PGE2 can lead to a rapid increase of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 [29]. Excess dietary AA can increase levels of phospholipase-A2, releasing AA, activating COX-2 to convert AA into PGE2, and increasing production of inflammatory leukotrienes by 5-lipoxygenase (5LOX). High levels of dietary AA also can increase gene expression levels of NF-κB. As a result, pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and Il-1β) were up-regulated by AA [69].

Leukotriene-A4, made from AA via 5LOX, is associated with reduced neuronal survival and reduced neurogenesis, increased formation of amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and more neuroinflammation [70].

AA is converted by 5LOX into the highly inflammatory leukotriene-A4. Leukotriene-A4 has a strong impact on increasing amyloid-β peptide production and tau phosphorylation in neuronal cells [65]. 5LOX has been found to be expressed in the brain: extremely high levels of 5LOX have been found in the hippocampus and other brain areas in those with AD. 5LOX levels are high in neurofibrillary structures and amyloid-beta-containing plaques. 5LOX is involved in pathological inflammatory cascades that could perpetuate neuronal degenerationand loss of synapses in AD [71]. Lower leukotriene-A4 and 5LOX levels were associated with a slower decline in psychomotor processing speed [72].

It has been reported that decreasing dietary AA can 1) reduce neuroinflammation, 2) reduce amyloid-beta oligomer production, 3) reduce the amyloid-beta oligomer-induced apoptotic neuronal death, and 4) reduce neurotoxicity. In addition, AA was found to compete with the incorporation of protective DHA in neuronal membrane phospholipids. Reducing dietary AA could be of interest in preventive and therapeutic strategies in AD [73].

Excess Brain Arachidonic Acid Is Found in AD Brains

AA incorporation in the AD brain is increased compared with control brains, both throughout the brain, and in regional brain areas demonstrating inflammatory neuropathology on postmortem. Positron emission tomography imaging of AA incorporation may become a marker of AD neuroinflammation for early diagnosis and evaluation of disease progression. It has been reported that AD patients had 23% increased brain AA [74]. Phospholipase-A2 was higher in AD brains compared to controls, indicating more release of AA and higher production of inflammatory PGE2 and leukotriene-A4. COX-2 was over-expressed in the brains of AD patients and has been reported to correlatewith the progression of the disease [65].

An accumulation of AA was observed in both the periphery and in the brain in patients with AD. Plasma AA was 37% higher in AD (5.40µM in control patients versus 7.38µM in AD) [75]. Blood lipid analyses show that higher AA in cell membrane phospholipids was able to identify patients at higher risk of AD [76]. Those with higher prostaglandin-F2-alpha, an eicosanoid made from AA, had a 45% increased risk of all-cause dementia [77].

Excess Dietary Arachidonic Acid Can Impair Cognition

LPS and AA can work synergistically to damage memory. Higher plasma LPS can affect memory functioning partly due to AA eicosanoid production, which is partially reversible with COX inhibitors [28]. Microglia treated with LPS produced 14 times the PGE2 from AA to increase IL-6 inflammation [29]. Another study confirms that LPS can activate COX2 to process AA and increase production of ROS, including peroxides and superoxide [30]. Leukotrienes made from AA can increase inflammation and programmed cell death in the brain [78]. Several studies reported that COX-2 is over-expressed in the cortex and hippocampus of patients affected by AD. If excess AA is available, the resulting increase of PGE2 can increase neuroinflammation [66].

In a crossover study with controlled diets, a group of men ate normal Western AA diets (210 mg/day) or normal diets supplemented to 1.5 g AA daily. A 41% increase in thromboxane was noted in the high AA group (prostacyclin offsets this effect partially) [79]. Also, dietary AA can amplify the amyloid-beta induced alteration of cognitive abilities and synaptotoxicity [66]. Thromboxane, when made from AA, is a powerful inducer of platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction that may contribute to thrombosis, vascular dementia, or stroke risk [79].

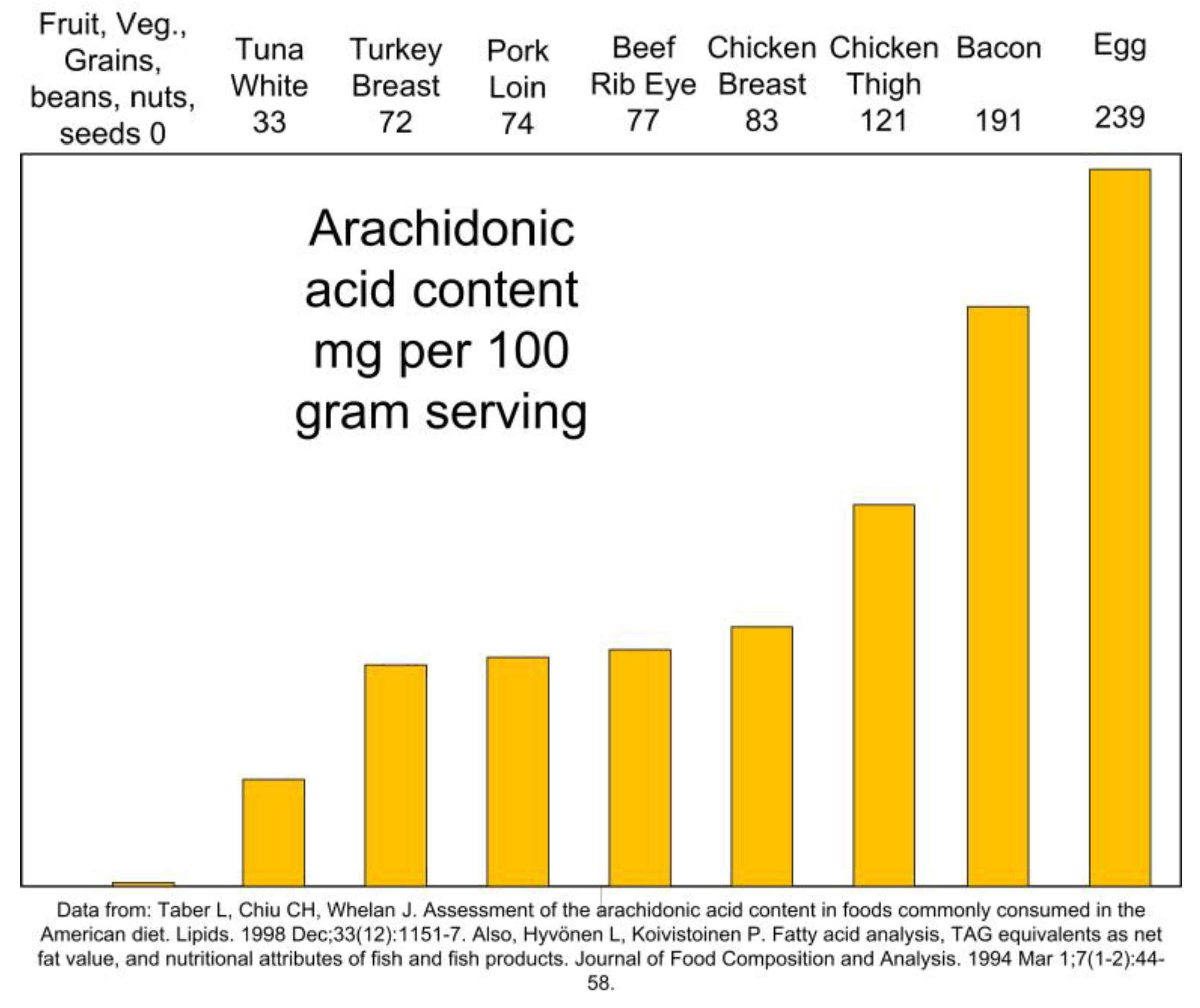

Sources of Arachidonic Acid in Food

Dietary AA is found only in animal foods [80]. AA highest dietary sources are meat, poultry, pork, and eggs (

Figure 5) [81]. On the contrary, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds contain no AA.

Humans can convert the plant-based omega-6 linoleic acid to AA in the amounts needed. Deficiency of linoleic acid is rare [82], and increasing dietary linoleic acid does not increase tissue AA content in adults consuming Western-type diets [83]. Excess AA from animal fats can increase neuroinflammation. AA amounts increased in the last 40 years in the western diets and the influence of dietary AA on the occurrence of AD is an important issue for the prevention and reduced progression of the disease.

AA in the diet can be efficiently absorbed and incorporated into neuronal membranes, resulting in an increased production of inflammatory thromboxane-A2 by platelets [79]. Plasma AA has been shown to be stable even with a higher dietary intake of the plant-based linoleic acid (C18:2 ω-6). However, a meta-analysis of 36 studies showed an association between dietary AA and higher AA amounts in blood. Brain AA content variations likely depend on dietary AA intake. More than 80% of dietary AA is provided by meat and egg, especially poultry [66]. In another study, a quarter gram of dietary AA (e.g. one egg) increased plasma AA by over 20% [83].

AA is concentrated in the membrane phospholipids of lean meats. Also, the concentration of AA in the visible fat portion of meats also may be significant. The visible fat of meat contained a significant quantity of AA, ranging from 20 to 180 mg/100 g fat, whereas the AA content of the lean portion of meat was lower, ranging from 30 to 99 mg/100 g lean meat. The highest level of AA in lean meat was in duck (99 mg/100 g), whereas pork fat had the highest concentration in the visible fats (180 mg/100 g) [84].

5. Conclusions

Research supports the hypothesis that higher dietary sources of LPS, AA, and AGEs can increase inflammation in the body and in the brain, while a lower dietary intake can reduce neuroinflammation and slow cognitive impairment [5,6].,. Therefore, neuroinflammation and risk of cognitive impairment and AD can be counteracted by avoiding foods that are highest in LPS, AGEs, and AA, such as dairy products, pork, poultry, beef, and seafood, and emphasizing in the diet foods lowest in LPS, AGEs, and AA, like fruits, vegetables, boiled whole grains, beans, raw nuts, and seeds. This approach may be useful for professionals and open the way to a comprehensive management of neurodegeneration, which should also include the quality of the diet. Future studies that reduce dietary sources of LPS, AA, and AGEs in AD are warranted to confirm the impact on neuroinflammation and the consequent reduction of the risk and progression of cognitive impairment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.; validation, C.B., L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., T.H., M.H., P.B.; visualization, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

(AD) Alzheimer’s disease, (AGEs) advanced glycation end products, (AA) arachidonic acid, (CD14) cluster of differentiation-14, (COX) cyclooxygenase, (IL-1β) interleukin-1-beta, (IL-6) interleukin-6, (LBP) LPS binding protein, (5LOX) 5-lipoxygenase, (LPS) lipopolysaccharide, (MCI) mild cognitive impairment, (NFқB) Nuclear factor kappa-B, (PGE2) prostaglandin-E2, (PL-A2) phospholipase-A2, (RAGE) receptor for advanced glycation end-products, (ROS) reactive oxygen species, (TNFα) tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

References

- Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed March, 2025).

- Saitgareeva AR, Bulygin KV, Gareev IF, Beylerli OA, Akhmadeeva LR. The role of microglia in the development of neurodegeneration. Neurological Sciences. 2020 Dec;41:3609-15. [CrossRef]

- Gorica E, Calderone V. Arachidonic acid derivatives and neuroinflammation. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders). 2022 Feb 1;21(2):118-29.

- Arnesen PM, Wettergreen M, You P, Fladby T. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes are differentially expressed upon Lipopolysaccharide stimulation in a myelogenic cell model. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2023 Dec;19:e080112. [CrossRef]

- Blake S, Baroni L, Sherzai D, Blake CP, Harding T, Piboolnurak P, Borman P, Harding M. Reducing dietary advanced glycation end products to slow progression of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Blake S, Harding T, Baroni L, Harding M, Blake C, Piboolnurak P, Grant W. Reducing dietary lipopolysaccharides to slow progression of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Brain Sciences. 2024 Jul 9;7(1):10-8488. [CrossRef]

- Szczechowiak K, Diniz BS, Leszek J. Diet and Alzheimer’s dementia–Nutritional approach to modulate inflammation. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2019 Sep 1;184:172743. [CrossRef]

- Henning, A., Venable, A., Vingren, J., Hill, D., & McFarlin, B. (2018). Consumption of a high-fat meal was associated with an increase in monocyte adhesion molecules, scavenger receptors, and propensity to form foam cells. Cytometry Part B: Cli.

- Gayle DA, Ling Z, Tong C, Landers T, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced dopamine cell loss in culture: roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and nitric oxide. Developmental Brain Research. 2002 Jan 31;133(1):27-3.

- Grant WB, Blake SM. Diet’s role in modifying risk of Alzheimer’s disease: History and present understanding. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023 Jan 1(Preprint):1-30.

- Wilson CJ, Finch CE, Cohen HJ. Cytokines and cognition—the case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002 Dec;50(12):2041-56.

- Niehaus I, Lange JH. Endotoxin: is it an environmental factor in the cause of Parkinson’s disease?. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2003 May 1;60(5):378-. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham C, Wilcockson DC, Campion S, Lunnon K, Perry VH. Central and systemic LPS challenges exacerbate the local inflammatory response and increase neuronal death during chronic neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005 Oct 5;25(40) . [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. C. (2019). The endotoxin hypothesis of neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 16(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Sharfman, N. M., Jaber, V. R., & Lukiw, W. J. (2019). Down-regulation of essential synaptic components by GI-tract microbiome-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in LPS-treated human neuronal-glial (HNG) cells in primary culture: Releva . [CrossRef]

- Creely SJ, McTernan PG, Kusminski CM, Fisher FM, Da Silva NF, Khanolkar M, Evans M, Harte AL, Kumar S. Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Ph. [CrossRef]

- McGrattan AM, McGuinness B, McKinley MC, Kee F, Passmore P, Woodside JV, McEvoy CT. Diet and inflammation in cognitive ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Current nutrition reports. 2019 Jun;8:53-65. [CrossRef]

- André P, Samieri C, Buisson C, Dartigues JF, Helmer C, Laugerette F, Feart C. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, soluble CD14, and the long-term risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a nested case-control pilot study of older community dwellers from t . [CrossRef]

- André P, Laugerette F, Féart C. Metabolic endotoxemia: a potential underlying mechanism of the relationship between dietary fat intake and risk for cognitive impairments in humans? Nutrients. 2019 Aug 13;11(8):1887.

- Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. Gastrointestinal-tract, microbiome-derived lipopolysaccharide and other pro-inflammatory neurotoxins in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021 Dec;17:e055635.

- Zhang R, Miller RG, Gascon R, Champion S, Katz J, Lancero M, Narvaez A, Honrada R, Ruvalcaba D, McGrath MS. Circulating LPS and systemic immune activation in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS). Journal of neuroimmunology. 2009 Jan 3;206(1-2):121-4. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tapia M, Mimenza-Alvarado A, Granados-Domínguez L, Flores-López A, López-Barradas A, Ortiz V, Pérez-Cruz C, Sánchez-Vidal H, Hernández-Acosta J, Ávila-Funes JA, Guevara-Cruz M. The Gut Microbiota–Brain Axis during Aging, Mild Cognitive.

- Saji N, Saito Y, Yamashita T, Murotani K, Tsuduki T, Hisada T, Sugimoto T, Niida S, Toba K, Sakurai T. Relationship between plasma lipopolysaccharides, gut microbiota, and dementia: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2022.

- Eikelenboom P, Van Exel E, Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller AJ, Van Gool WA. Neuroinflammation–an early event in both the history and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2010 Feb 13;7(1-3):38-41.

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2015 Jun;16(6):358-72. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Navarrete JM, Blasco G, Puig J, Biarnés C, Rivero M, Gich J, Fernandez-Aranda F, Garre-Olmo J, Ramio-Torrenta L, Alberich-Bayarri A, García-Castro F. Neuroinflammation in obesity: circulating lipopolysaccharide-binding protein associate . [CrossRef]

- DellaGioia N, Hannestad J. A critical review of human endotoxin administration as an experimental paradigm of depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010 Jan 1;34(1):130-43. [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011 Feb 1;25(2):181-213.

- Fiebich BL, Hüll M, Lieb K, Schumann G, Berger M, Bauer J. Potential link between interleukin-6 and arachidonic acid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. In Alzheimer’s Disease—From Basic Research to Clinical Applications 1998 Jan 1 (pp. 269-278.

- Berk, M., Williams, L. J., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Pasco, J. A., Moylan, S. Byrne, M. L. (2013). So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Medicine, 11(1), 200.

- Laugerette F, Alligier M, Bastard JP, Drai J, Chanséaume E, Lambert-Porcheron S, Laville M, Morio B, Vidal H, Michalski MC. Overfeeding increases postprandial endotoxemia in men: Inflammatory outcome may depend on LPS transporters LBP and sCD1 . [CrossRef]

- Laugerette F, Vors C, Peretti N, Michalski MC. Complex links between dietary lipids, endogenous LPSs and metabolic inflammation. Biochimie. 2011 Jan 1;93(1):39-45.

- Vors C, Drai J, Pineau G, Laville M, Vidal H, Laugerette F, Michalski MC. Emulsifying dietary fat modulates postprandial endotoxemia associated with chylomicronemia in obese men: a pilot randomized crossover study. Lipids in Health and Disease . [CrossRef]

- White AJ, Wijeyekoon RS, Scott KM, Gunawardana NP, Hayat S, Solim IH, McMahon HT, Barker RA, Williams-Gray CH. The peripheral inflammatory response to alpha-synuclein and endotoxin in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in neurology. 2018 Nov 20;9: . [CrossRef]

- Erridge C. Accumulation of stimulants of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 and TLR4 in meat products stored at 5 C. Journal of food science. 2011 Mar;76(2):H72-9.

- Brown BI. Nutritional Management of Metabolic Endotoxemia: A Clinical Review. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine. 2017 Jul 1;23(4).

- Faraj TA. Regulation of cardiometabolic risk factors by dietary Toll-like receptor stimulants (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester) 2017.

- Kellow NJ, Coughlan MT, Reid CM. Association between habitual dietary and lifestyle behaviours and skin autofluorescence (SAF), a marker of tissue accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), in healthy adults. European journal of nu . [CrossRef]

- Blake S, King G, Kerr N, Blake C, Harding T, Borman P, Moss K, Adapon P, Liow KK. Hawaii Dementia Prevention Trial: A Randomized Trial Evaluating a Multifaceted Nutritional Intervention to Slow Cognitive Decline in Mild Cognitive Impairment Pa . [CrossRef]

- Li XH, Du LL, Cheng XS, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Lv BL, Liu R, Wang JZ, Zhou XW. Glycation exacerbates the neuronal toxicity of beta-amyloid. Cell death & disease. 2013 Jun;4(6):e673-. [CrossRef]

- Xanthis A, Hatzitolios A, Koliakos G, Tatola V. Advanced glycosylation end products and nutrition—a possible relation with diabetic atherosclerosis and how to prevent it. Journal of food science. 2007 Oct;72(8):R125-9. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Mooldijk SS, Licher S, Waqas K, Ikram MK, Uitterlinden AG, Zillikens MC, Ikram MA. Assessment of advanced glycation end products and receptors and the risk of dementia. JAMA network open. 2021 Jan 4;4(1):e2033012-. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Ansari VA, Mahmood T, Ahsan F, Wasim R, Shariq M, Parveen S, Maheshwari S. Receptor for advanced glycation end products: dementia and cognitive impairment. Drug Research. 2023 Mar 8. [CrossRef]

- Van Puyvelde K, Mets T, Njemini R, Beyer I, Bautmans I. Effect of advanced glycation end product intake on inflammation and aging: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews. 2014 Oct 1;72(10):638-50. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Liu D, Sun L, Lu Y, Zhang Z. Advanced glycation end products and neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and perspective. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2012 Jun 15;317(1-2):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Nedi O, Rattan SI, Grune T, Trougakos IP. Molecular effects of advanced glycation end products on cell signalling pathways, ageing and pathophysiology. Free Radical Research. 2013 Aug 1;47(sup1):28-38. [CrossRef]

- Perrone L, Grant WB. Observational and ecological studies of dietary advanced glycation end products in national diets and Alzheimer’s disease incidence and prevalence. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015 Jan 1;45(3):965-79. [CrossRef]

- Vlassara H, Cai W, Crandall J, Goldberg T, Oberstein R, Dardaine V, Peppa M, Rayfield EJ. Inflammatory mediators are induced by dietary glycotoxins, a major risk factor for diabetic angiopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Cai W, Uribarri J, Zhu L, Chen X, Swamy S, Zhao Z, Grosjean F, Simonaro C, Kuchel GA, Schnaider-Beeri M, Woodward M. Oral glycotoxins are a modifiable cause of dementia and the metabolic syndrome in mice and humans. Proceedings of the National . [CrossRef]

- Uribarri J, del Castillo MD, de la Maza MP, Filip R, Gugliucci A, Luevano-Contreras C, Macías-Cervantes MH, Markowicz Bastos DH, Medrano A, Menini T, Portero-Otin M. Dietary advanced glycation end products and their role in health and disease. [CrossRef]

- Vitek MP, Bhattacharya K, Glendening JM, Stopa E, Vlassara H, Bucala R, Manogue K, Cerami A. Advanced glycation end products contribute to amyloidosis in Alzheimer disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994 May 24;91(11):47. [CrossRef]

- Angeloni C, Zambonin L, Hrelia S. Role of methylglyoxal in Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed research international. 2014 Oct;2014.

- Sharma A, Weber D, Raupbach J, Dakal TC, Fließbach K, Ramirez A, Grune T, Wüllner U. Advanced glycation end products and protein carbonyl levels in plasma reveal sex-specific differences in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Redox biology. 2 . [CrossRef]

- Ahmed N, Ahmed U, Thornalley PJ, Hager K, Fleischer G, Münch G. Protein glycation, oxidation and nitration adduct residues and free adducts of cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease and link to cognitive impairment. Journal of neurochemist . [CrossRef]

- Prasad C, Davis KE, Imrhan V, Juma S, Vijayagopal P. Advanced glycation end products and risks for chronic diseases: intervening through lifestyle modification. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2019 Jul;13(4):384-404. [CrossRef]

- Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, Cai W, Chen XU, Pyzik R, Yong A, Striker GE, Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010 Jun 1 . [CrossRef]

- Beisswenger BG, Delucia EM, Lapoint N, Sanford RJ, Beisswenger PJ. Ketosis leads to increased methylglyoxal production on the Atkins diet. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005 Jun;1043(1):201-10. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg T, Cai W, Peppa M, Dardaine V, Baliga BS, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004 Aug 1;104(8):1287-91. [CrossRef]

- Palimeri S, Palioura E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Current perspectives on the health risks associated with the consumption of advanced glycation end products: recommendations for dietary management. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targe . [CrossRef]

- Abate G, Marziano M, Rungratanawanich W, Memo M, Uberti D. Nutrition and AGE-ing: Focusing on Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2017 Oct;2017. [CrossRef]

- Tabara Y, Yamanaka M, Setoh K, Segawa H, Kawaguchi T, Kosugi S, Nakayama T, Matsuda F, Nagahama Study Group. Advanced glycation end product accumulation is associated with lower cognitive performance in an older general population: the Nagaham . [CrossRef]

- Igase M, Ohara M, Igase K, Kato T, Okada Y, Ochi M, Tabara Y, Kohara K, Ohyagi Y. Skin autofluorescence examination as a diagnostic tool for mild cognitive impairment in healthy people. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017 Jan 1;55(4):1481-7. [CrossRef]

- Chou PS, Wu MN, Yang CC, Shen CT, Yang YH. Effect of advanced glycation end products on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019 Jan 1;72(1):191-7. [CrossRef]

- Mooldijk SS, Lu T, Waqas K, Chen J, Vernooij MW, Ikram MK, Zillikens MC, Ikram MA. Skin advanced glycation end products and the risk of dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2022 Dec;18:e061469. [CrossRef]

- Thomas MH, Olivier JL. Arachidonic acid in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology & Neuromedicine. 2016 Dec 12;1(9). [CrossRef]

- Thomas MH, Pelleieux S, Vitale N, Olivier JL. Dietary arachidonic acid as a risk factor for age-associated neurodegenerative diseases: Potential mechanisms. Biochimie. 2016 Nov 1;130:168-77. [CrossRef]

- Fujimi K, Noda K, Sasaki K, et al. Altered expression of COX-2 in subdivisions of the hippocampus during aging and in Alzheimer’s disease the Hisayama Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(6): 423 31. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson DT, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Clemens JA. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) immunoreactivity is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiology of disease. 1996 Feb 1;3(1):51-63. [CrossRef]

- Bao Y, Shen Y, Wu Z, Tao S, Yang B, Zhu T, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Jiao L, Wang Z. High dietary arachidonic acid produces excess eicosanoids, and induces hepatic inflammatory responses, oxidative stress and apoptosis in juvenile Acanthopagrus . [CrossRef]

- Michael J, Marschallinger J, Aigner L. The leukotriene signaling pathway: a druggable target in Alzheimer’s disease. Drug discovery today. 2019 Feb 1;24(2):505-16. [CrossRef]

- Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Uz T, Manev H, DeKosky ST. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 2008 Dec;56(12):1065-73. [CrossRef]

- Xiong LY, Ouk M, Wu CY, Rabin JS, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Black SE, Edwards JD, Swardfager W. Leukotriene receptor antagonist use is associated with slower cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021 Dec;17:e057523. [CrossRef]

- Thomas M, Pelleïeux S, Allouche A, Colin J, Oster T, Malaplate-Armand C, Olivier JL. Control of Intracellular Levels of Free Arachidonic Acid: A Target in Therapeutic or Preventive Strategies against Alzheimer’s desease?. Arachidonic Acid: Sou.

- Rapoport SI, Carson RE, Bhattacharjee A, Schapiro MB, Herscovitch P, Eckelman W, Esposito G. Imaging neuroinflammation in Alzheimer disease with [1–11C] arachidonic acid and positron emission tomography. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2005 Jul 1;1(1).

- Hammouda S, Ghzaiel I, Khamlaoui W, Hammami S, Mhenni SY, Samet S, Hammami M, Zarrouk A. Genetic variants in FADS1 and ELOVL2 increase level of arachidonic acid and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the Tunisian population. Prostaglandins, Le . [CrossRef]

- Abdullah L, Evans JE, Emmerich T, Crynen G, Shackleton B, Keegan AP, Luis C, Tai L, LaDu MJ, Mullan M, Crawford F. APOE ε4 specific imbalance of arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid in serum phospholipids identifies individuals with precl.

- Trares K, Gào X, Perna L, Rujescu D, Stocker H, Möllers T, Beyreuther K, Brenner H, Schöttker B. Associations of urinary 8-iso-prostaglandin F2? levels with all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia incidence: results from.

- Maccarrone M, Melino G, Finazzi-Agro A. Lipoxygenases and their involvement in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ.2001; 8: 776–784. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti A, Nelson GJ, Schmidt PC, Kelley DS, Bartolini G, Flanagan VP. Increased dietary arachidonic acid enhances the synthesis of vasoactive eicosanoids in humans. Lipids. 1997 Apr;32(4):435-9. [CrossRef]

- Blake S, Piboolnurak P, Borman P, Harding T, Blake C. Reducing Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease with Dietary Compounds. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022 Feb 2;18(02):026-37. [CrossRef]

- Pinchaud K, Maguin-Gaté K, Olivier JL. Dietary arachidonic acid: a Janus face actor in brain and Alzheimer’s disease?. OCL. 2018 Jul 1;25(4):D406. [CrossRef]

- Whelan J, Fritsche K. Linoleic acid. Adv Nutr. 2013 May 1;4(3):311-2. PMID: 23674797; PMCID: PMC3650500. [CrossRef]

- Rett BS, Whelan J. Increasing dietary linoleic acid does not increase tissue arachidonic acid content in adults consuming Western-type diets: a systematic review. Nutrition & metabolism. 2011 Dec;8:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Ng A, Mann NJ, Sinclair AJ. Contribution of meat fat to dietary arachidonic acid. Lipids. 1998 Apr;33:437-40. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).