1. Introduction

Gum rosin—also known as rosin or colophony—is a natural, renewable resin obtained from the distillation of pine sap. Historically, it has been used in various applications, for example in varnishes, coatings, and adhesives [

1,

2]. The last few decades have marked significant progress in rosin research and the innovative applications, including in the field of drug delivery systems (DDS). Rosin has been used widely in biomedical applications due to its availability, cost-effectiveness, and inherent properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and chemical versatility [

3,

4,

5]. Study by Mardiah et al. (2023) shows that rosin is biodegradable and exhibits good film-forming capabilities, and so can be used in biomedical applications, such as antibacterial coatings [

6]. To further enhance the performance, numerous chemical modifications have been introduced. For example, a study synthesized water-soluble rosin-PEG derivatives using PEG 1500, achieving complete water solubility and a melting point of 40.6 °C. These derivatives improved wettability and pH-dependent aqueous solubility, making it suitable for controlled drug release applications [

7]. Additionally, rosin’s capacity to be transformed into polymerizable monomers has been applied in advanced DDS, including controlled and targeted drug delivery [

8]. These modifications of rosin enhance its functionality as a coating agent in various dosage forms and enable its integration into nanoparticles for controlled drug release [

9,

10].

The advancements in applications of rosin and the derivatives are already summarized in several review articles [

3,

11,

12]. A well written review on gum rosin modifications were published in 2019. However, the paper discussed broadly on various applications [

3], while we want to focus on rosin application in pharmaceutical field. Several review papers already focused specifically on drug delivery systems, unfortunately they were published not later than 2016 [

11,

13]. Therefore, this review aims to comprehensively evaluate the current state of rosin applications in DDS, emphasizing its potential in pharmaceutical formulations. We also address the challenges associated with using gum rosin—such as allergenic potential, brittleness, and excessive hydrophobicity—and discuss various strategies (including chemical modifications and polymer blending) that have been developed to overcome these limitations. In doing so, this paper serves as a reference for researchers seeking to design new methods for synthesizing rosin-based materials tailored for modern drug delivery applications.

2. Chemical and Physical Properties

Gum rosin is defined as the non-volatile residue obtained from the distillation of pine tree sap. This sap is sourced from various species of pine—for example, Pinus massoniana in China, Pinus elliotti in Brazil, and Pinus merkusii in Indonesia [

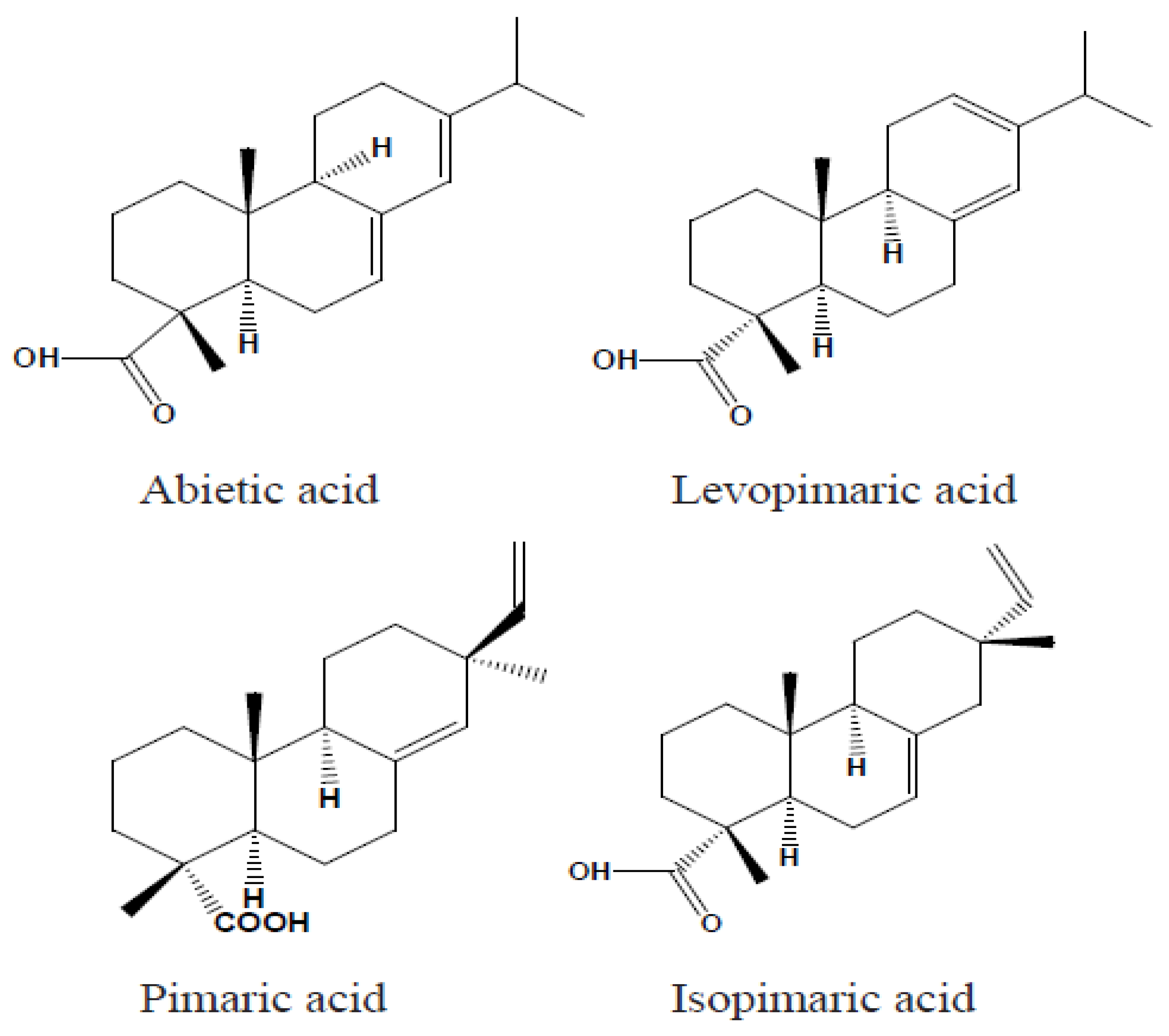

3]. Typically, gum rosin comprises 90–95% resin acids, which consist of a mixture of abietic-type and pimaric-type acids, while the remaining fraction is made up of non-acidic substances [

11]. Rosin acids are tricyclic diterpene monocarboxylic acids built around a phenanthrene nucleus and are generally represented by the molecular formula C₍₂₀₎H₍₃₀₎O₂. This complex structure features two primary reactive sites: the carbon–carbon double bonds and the carboxyl group. In abietic acids, the double bonds are conjugated, which is not the case for pimaric acids. Notable examples of abietic-type acids include abietic acid, neoabietic acid, palustric acid, and levopimaric acid. Moreover, rosin may contain trace amounts of aromatic dehydroabietic acid, and its overall composition can vary with the botanical and geographical origin of the resin. These compositional variations can complicate the precise quantification of individual resin acids.

Figure 1 illustrates the chemical structures of representative abietic and pimaric rosin acids [

11].

Gum rosin is generally a fragile, brittle solid with a characteristic pine aroma. In some instances, rosin can form crystals upon dissolution in solvents. At room temperature, the form is a hard and brittle material. However, when heated, it softens and becomes sticky. The melting point of rosin can vary, some samples become semi-fluid at the boiling point of water, while others require temperatures up to 120 °C for complete melting. Rosin exhibits low solubility in polar solvents but dissolves readily in many non-polar solvents, including alcohol, benzene, ether, chloroform, glacial acetic acid, various oils, carbon disulfide, and dilute solutions of fixed alkali hydroxides. One important characteristic of rosin is its low toxicity, which show the suitability for use in food, beverage, and pharmaceutical applications [

13]. Gum rosin can be classified based on the colour and softening point. Generally, a decrease in the softening point correlates with a darker colour. Lighter shades of rosin typically have higher softening points and acid numbers, whereas darker rosin tends to contain increased amounts of unsaponifiable matter, alcohol-insoluble components, and ash. In addition, the colour intensity of rosin is related to the abietic acid content—darker rosin indicates a higher concentration of abietic acid [

11,

13].

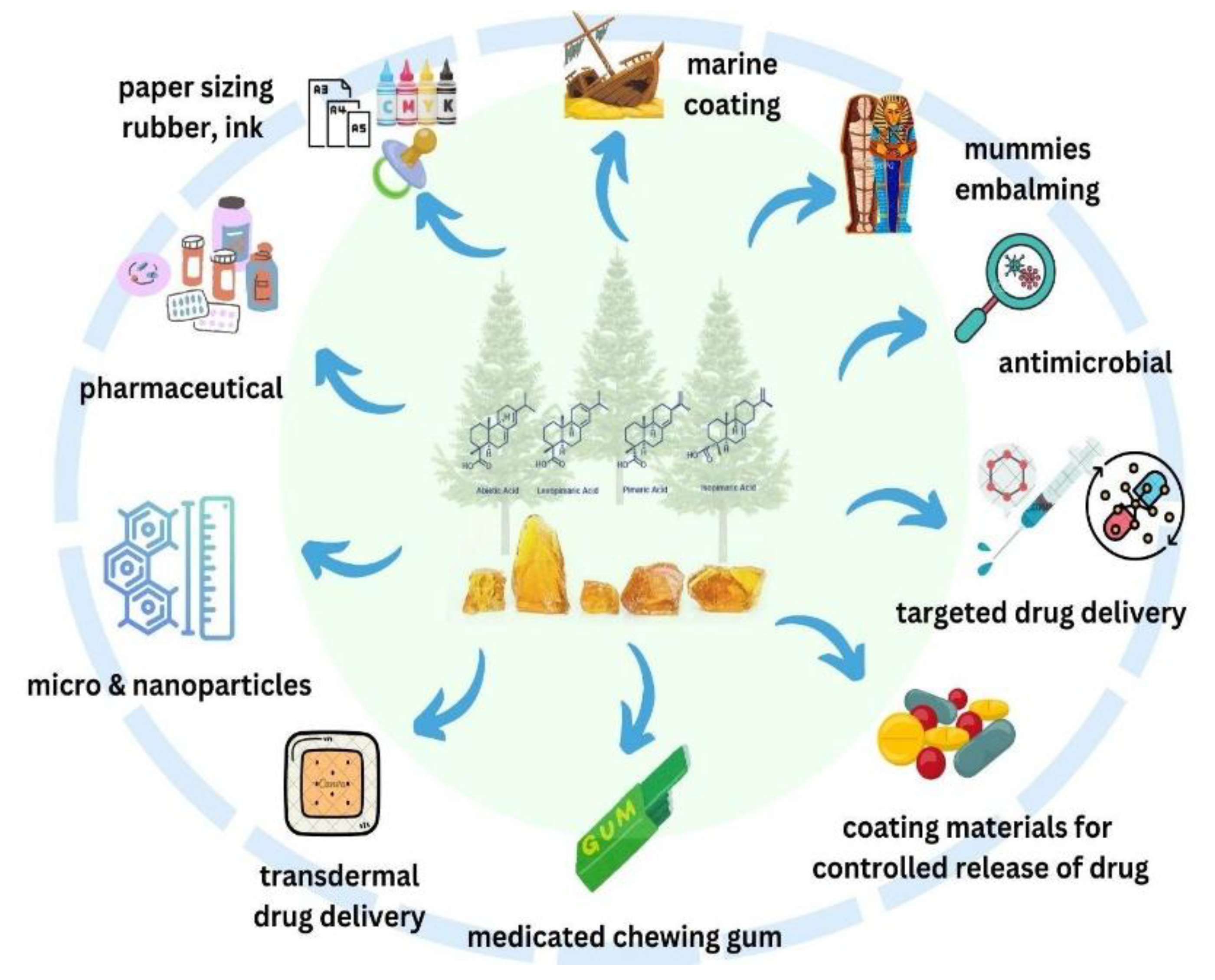

3. General Uses

Rosin and its derivatives can be employed in both solid and dissolved states, serving many purposes in their applications, as described in

Figure 2. The summary of general application can be seen in

Table 1. Ongoing researches are still being performed to improve the performances and to find wider applications.

4. Medical and Pharmaceutical Applications

It is of interest that rosin and its derivates can also be utilized in medical fields. Researchers have identified various functions of rosin gum in pharmaceutical applications, as detailed below.

4.1. Antimicrobial Agents

Pure spruce wood—a natural source of rosin—exhibits antibacterial effects against pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Salmonella enterica [

29]. Gamma irradiation has further been shown to enhance these antimicrobial properties [

30]. The antibacterial effect is primarily attributed to the presence of abietic-type resin acids in rosin, which disrupt bacterial cell walls (particularly in Staphylococcus aureus), thereby impeding cellular energy generation [

31]. Despite these promising properties, the high hydrophobicity of unmodified rosin limits its antimicrobial effectiveness in aqueous environments. To overcome this challenge, rosin has been chemically modified into its maleic anhydride adduct, which improves water solubility and enhances bioinhibitory performance against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [

32]. Moreover, blending rosin with biobased polymers such as cellulose acetate, poly(butylene succinate), and starch has yielded formulations with significant antimicrobial activity (Bezzekhami et al., 2023; Chang et al., 2020; Kanerva et al., 2020). It is important to note that the botanical origin of rosin, its incorporation into polymer matrices, and the mode of bacterial exposure can substantially influence its antibacterial response [

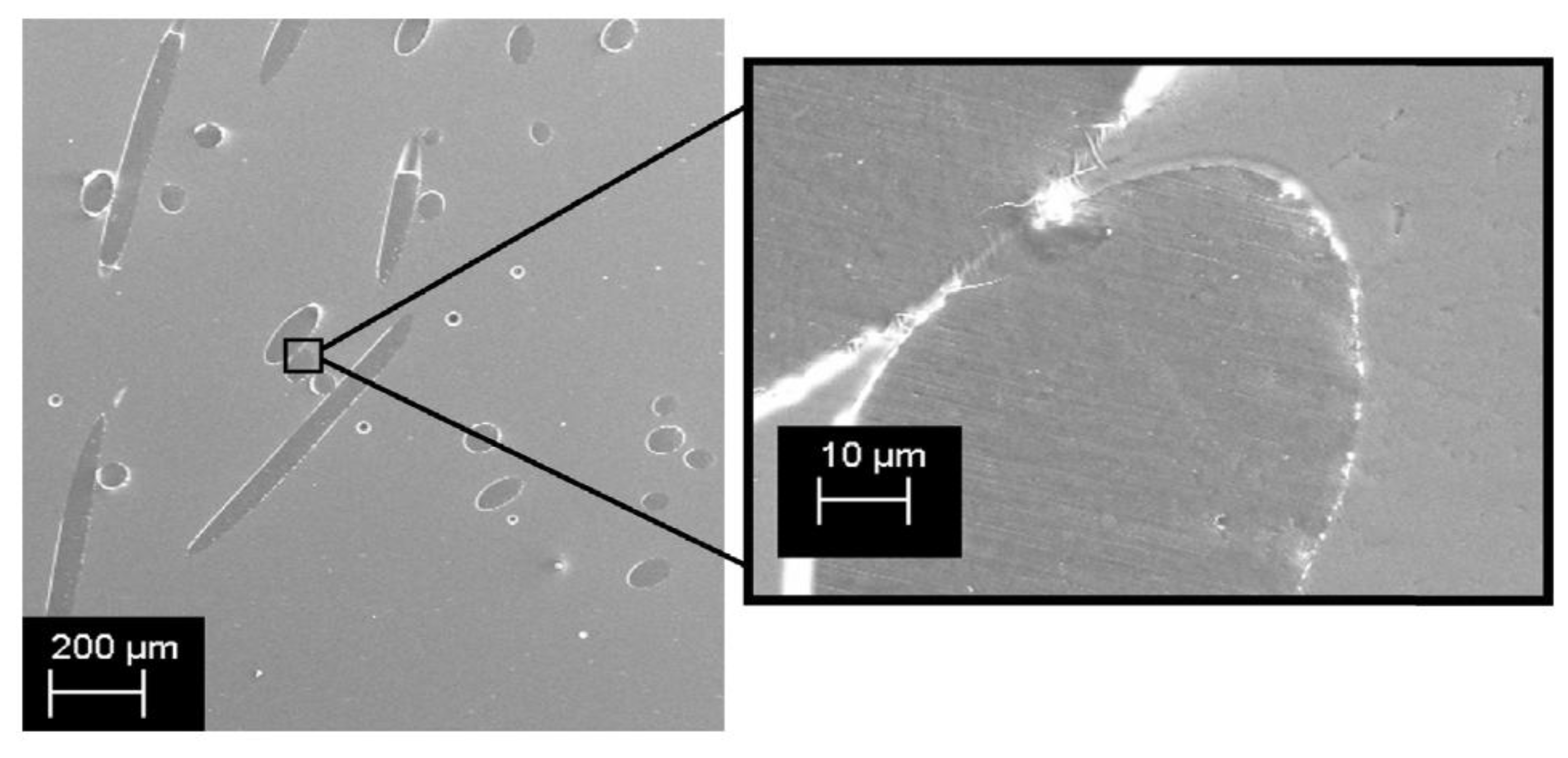

36]. For example, incorporating 10–20% rosin into polymers such as polyethylene (PE) to produce fibers or filaments has resulted in materials with both robust mechanical properties and effective antimicrobial performance, as evidenced by SEM images in

Figure 3. demonstrating good compatibility between rosin and PE and effective inhibition of E. coli and S. aureus [

37].

Additional modification strategies have focused on synthesizing biodegradable cationic antimicrobial compounds by combining rosin acid with quaternary ammonium groups. These cationic groups promote rapid adhesion to negatively charged bacterial cell surfaces, leading to cell lysis, and they preferentially target microbial cells over mammalian cells, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development. One study demonstrated that maleopimaric acid quaternary ammonium cations (MPA-N+) chemically bonded onto cotton textile surfaces (CT-g-MPA-N+) produced a wound dressing with potent antibacterial activity against both Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus). This modified dressing maintained its antibacterial effectiveness even after prolonged immersion in phosphate-buffered saline and inhibited bacterial biofilm formation [

39,

40]. Furthermore, Jindal et al. (2017) developed an iron oxide nanogel using a gum rosin–acrylamide copolymer matrix, which demonstrated significant antibacterial efficacy against both S. aureus and E. coli, with a notably stronger effect against S. aureus—a result attributed to differences in cell membrane charge that enhance interactions with the nanogel components [

41]. Recent study by Bezzekhami et al. (2023) using Nanoarchitectonics of Starch Nanoparticles Rosin shows the enhanced antimicrobial activity against several strains (Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and yeast), with the inhibition zone directly proportional to the degree of substitution, indicating their promising potential in biomedical and food-packaging applications [

21].

4.2. Anticancer Agents

Beside antimicrobial activity, several studies also showed that modification of gum rosin resulted substance with anti-cancer activity. A study performed by Fei et al. (2019) presented the rational synthesis of two chiral copper(II) complexes, [CuL4Cl]Cl·2CH2Cl2·H2O (1) and [CuL4Br]Br·2CH2Cl2 (2), derived from rosin and ligand L (2-amino-5-dehydroabietyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole). The obtained modified rosin exhibited significant in vitro and in vivo anticancer activities with tolerable toxicities. It induced cell death in MCF-7 cells through a combination of G1 phase arrest, apoptosis (involving both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways), anti-metastasis, anti-angiogenesis, and damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids. Autophagy, mediated by oxidative stress, was also evident. [

42]. Another study explored antioxidant activity of rosin-derived crude methanol extract (RD-CME) using 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, and assessed cytotoxicity of RD-CME against two types of breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB231) using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric. The results proved that a low concentration of RD-CME showed high antioxidant scavenging activities. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of test showed that RD-CME exhibited a high cytotoxicity against the two cancer cells, even higher than the control drug (doxorubicin) [

43].

4.3. Corrosion Retardant for Biodegradable Implants

The use of biodegradable implants in bone screws, plates, and pins is preferable to avoid the need of removing implants after they are no longer needed. Magnesium is a potential candidate, since it is degradable in physiological environment, and it is naturally found in bone tissues. However, magnesium degrades very quickly in aqueous environment, leading to quick formation of hydrogen gas and diminishing its mechanical integrity. Coating materials made of mixtures of gum rosin and beeswax were found to reduce the corrosion rate of magnesium alloys in NaCl solution. The coating itself is expected to be biodegradable and harmless to human body, in addition to be made from renewable resources [

44].

4.4. Remineralization-Promoting Tooth Varnish

Dental caries is one of the most common chronic childhood diseases caused by excessive demineralization of the teeth surfaces. The condition can be repaired by applying remineralization-promoting varnishes on the damaged surface. Gum rosin is a popular material used as a matrix of tooth varnish, carrying fluoride as a remineralization-promoting agent. Due to higher sensitivity towards fluoride found in children, some researches were performed to find safer remineralization promotors. It was found that gum rosin varnish containing peptide, bioactive glass, and egg shells performed similar mineralization promotion to fluoride-containing varnishes [

45,

46,

47].

4.5. Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms

The primary goal of drug delivery is to maximize therapeutical effect, minimize adverse effects and improve patients’ compliance by delivering the drugs directly to the site of action. The types of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) have evolved from small molecules (less than 900 daltons) to more complicated matters as peptides, proteins, antibodies, nucleic acids, and living cells. Each of these materials has specific characteristics, thus exhibit different challenges in formulating them into suitable drug delivery system [

48,

49]. The current trend towards utilization of sustainable materials in the development of biodegradable dosage forms has increased the interest in gum rosin as a potential excipients of drug delivery systems. This change is motivated by the growing necessity to reduce the reliance on petroleum-based synthetic polymers and harmful substances [

50,

51]. Some research examined the modification of abietic acid plentifully found in gum rosin. [

52]. Various reports described the use of gum rosin and its derivatives in drug delivery system, most were designed for small molecules drugs, ranging from relatively simple mechanisms to the more sophisticated ones. These works are explained in a dedicated section below.

5. Drug Delivery System

A study performed by Tewabe et al. (2021) provides a framework for understanding the develpoment of drug delivery technology, started from Generation 1: Conventional dosage forms: Capsule, tablet, emulsion, suspension; Generation 2: Modified action systems: enteric coating, repeat/prolong action; Generation 3: Controlled delivery systems: osmotically swelling & diffusion controlled systems; Generation 4: Targeted delivery systems: targeted, modulated, self-regulated delivery systems; and the advanced Generation 5: Nanorobots, gene therapy, biologicals, long-term delivery systems [

54]. Various materials have been used as excipients, and there is a growing trend in using natural resources in this application, including gum rosin. It can serve as a versatile film-forming material, providing film coatings enable sustained drug release. Gum rosin also plays a crucial role in the formation of microparticles with varied properties, from enhanced thermal stability to adjustable characteristics suitable for controlled-release drug administration and encapsulation. A study by Rosa-Ramirez (2023) showed that gum rosin esters proved to be effective, bio-based processability aids, offering enhanced flow properties and modest thermal and mechanical improvements with minimal downsides [

55]. Its multifaceted properties, biocompatibility, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendly nature further highlight its potential in the development of drug delivery systems. Various scientific papers reported the application of gum rosin and its derivatives in various drug dosage forms, includes plasters and ointments, matrix-forming in sustained-release tablet or medicated chewing gum (Generation 2), film-forming in transdermal film, coating agent in enteric-coated, sustained-released or microparticles dosage forms (Generation 3) and excipients for advanced drug delivery systems (Generation 4).

5.1. Taste Masking Agent

Many orally-administered drugs have unpleasant flavour, suggesting the need of taste masking agents. Gum rosin is widely known as a nontoxic and hydrophobic substance; thus, it can serve as film coating materials for taste-masking purposes. In a study by Jacob (2012), gum rosin, in combination with ethyl cellulose and PEG 400 as a plasticizer, was utilized as a taste masking film for ambroxol hydrochloride, an anti-mucolytic medicine. The study successfully produced smooth-surfaced microspheres with enhanced taste-masking characteristics and consistent diameters. This innovative approach proved that gum rosin is potential as coating excipient to improve the taste acceptability of pharmaceutical substances, offering a potential solution for the development of patient-centric, and enhancing patient adherence to medication [

56,

57].

5.2. Coating Materials for Controlled-release Dosage Forms

Chen et al. (2022) reported a durable, fluorine-free superhydrophobic coating made from sulfhydryl-modified rosin acid and silica nanoparticles (SiO₂). Rosin’s natural phenanthrene ring structure enhances chemical stability and mechanical strength without the environmental risks posed by fluorinated materials. These attributes position rosin-based superhydrophobic coatings as promising candidates for advanced applications in healthcare, including anti-fouling medical devices and antimicrobial dressings, where low toxicity and biodegradability are necessary [

58]. In similar study, Zaoui et al. (2020) found that rosin’s natural hydrophobic and renewable characteristics could be improved for sustainable applications, including the possibility of continuous processing and use in biomedical contexts such as tissue engineering [

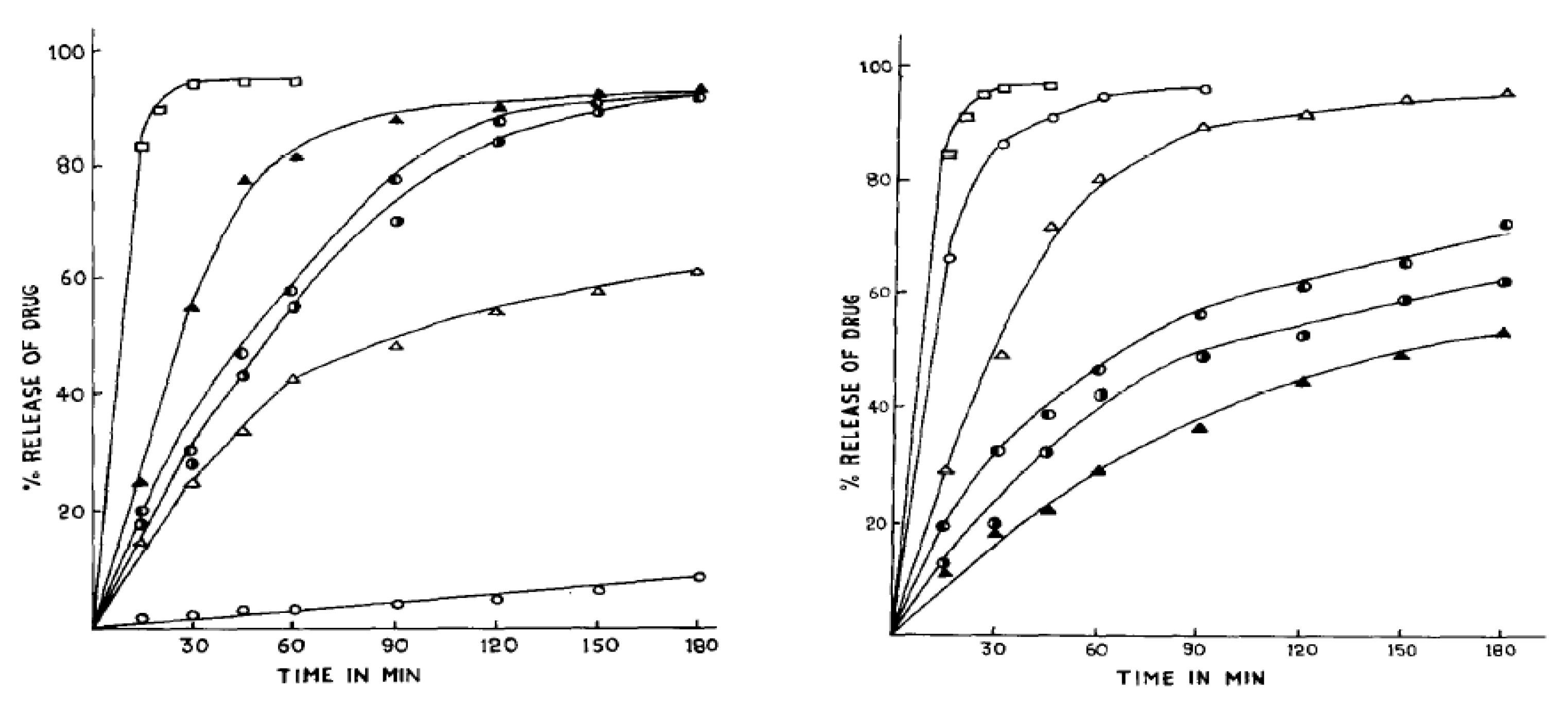

59]. Pathak et al. (1985) demonstrated that esterification of rosin with polyols such as glycerol, mannitol, or sorbitol produced effective film coatings that modulated the dissolution rate of aspirin tablets in simulated gastric and intestinal fluids [

60]. In subsequent studies, the same group compared various coating excipients—namely, unmodified rosin, rosin pentaerythritol ester (RPE), and rosin maleic acid adducts esterified with glycerol (RMEG) or pentaerythritol (RMEP). Their experiments revealed that both rosin and RPE provided exceptional moisture protection and unique drug release patterns (see

Figure 4) with RPE emerging as the most satisfactory coating for controlled release due to its superior ability to retain drug release in the intestinal medium [

61]. Recent study by Burakele (2023) showed that rosin films, particularly when combined with plasticizers, demonstrated suitability for coating captopril tablets, allowing for delayed drug release. The coated tablets exhibited slow, controlled drug release for up to 8 hours, ideal for chronotherapy targeting hypertensive crises, with stability studies confirming the formulations’ robustness over time [

62]. Wang et al. (2024) also found rosin-apatite hybrids demonstrate high adsorption capacity for phenol and a good drug loading capacity for adriamycin through π–π stacking interactions with the rosin moieties [

63].

5.3. Medicated Chewing Gum

Medicated chewing gum (MCG) has gained attention in drug delivery applications, as highlighted by a review from Thivya et al. (2021). This form of drug delivery has a broad range of applications, including drug delivery and nutraceuticals, with increasing demand, particularly for conditions related to oral hygiene and bad breath caused by smoking. MCGs offer non-invasiveness, easy administration, and faster metabolism through the liver or gut wall, making them popular for targeted drug delivery. MCGs, defined as a form of solid that can be chewed but not swallowed, contain bioactive or pharmaceutical compounds coated with a masticatory gum base. These compounds are released during the chewing process and absorbed in the oral mucosa, providing drug release for various oral diseases. Challenges in MCGs include factors affecting the release of active substances, such as membrane thickness, environmental conditions, chewing time, and solubility. Additionally, individual variability and formulation factors influence the efficiency of release. Despite these challenges, MCGs demonstrate efficacy in drug delivery, offering a fast onset time for systemic effects and reducing gastrointestinal and hepatic first-pass metabolism. Gum rosin played role as elastomer excipient in this type of dosage form [

64].

Another study by Pandit & Joshi (2006) developed a chewing gum formulation designed for buccal delivery of diltiazem hydrochloride, aiming to bypass first-pass metabolism and achieve rapid onset of action. They synthesized an ester derivative of rosin (a hydrophobic gum base) and incorporated the drug along with plasticizers (soybean oil or castor oil), beeswax, and sweeteners. In vitro and in vivo tests—measuring drug release into saliva and monitoring urinary excretion—showed that diltiazem hydrochloride was substantially absorbed via the buccal route within 15 minutes of chewing, with minimal residual drug in the gum [

65]. The findings suggest that medicated chewing gum using rosin derivatives can be a novel, convenient system for delivering diltiazem hydrochloride quickly and effectively, potentially lowering the required dose and reducing hepatic first-pass effects.

5.4. Transdermal Drug Delivery System

Skin is the largest organ in human body; thus, it can serve as an alternative absorption site. Transdermal administration is comfortable for patients and avoids first pass metabolism of the drugs. Despite its good film-forming ability, gum rosin is rarely used in transdermal drug delivery system, probably due to its dermal toxicity nature. However, this problem can be addressed by tailored modifications of the material. In a study by Satturwar, et.al. (2005), polymerized gum rosin-derived abietic acid (PR) was used in the formulation of matrix-type transdermal drug delivery systems, with the goal of achieving controlled drug release. The challenges addressed included the need for flexible films with enhanced mechanical characteristics that could modulate drug release kinetics and transdermal penetration. To address these challenges, the researchers combined PR, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and dibutyl phthalate to make flexible film matrices containing a model drug diltiazem hydrochloride (DTH). PR tended to retain the drug while PVP released the drug more easily. The modulation of drug and PR-PVP composition allowed for the regulation of drug release kinetics and transdermal penetration from these films. This methodology presents a promising opportunity for the advancement of transdermal patches, offering the potential for assessing pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in suitable animal models [

66]

5.5. Micro- and Nanoparticles

The invention of medications in micro- and nanoparticle forms is revolutionary, because they are capable of high concentration of drug active agent uptake in their matrix and enables the long-acting medicines with release period up to six months. Long-acting strategy reduces the frequency of medication, thus improving patients’ comfort and compliance. The micro and nano sizes also enable, although not limited to, drug administration via injections, thus avoiding possibility of degradation when the drugs are administered orally [

48,

49]. In vitro drug release studies demonstrated that nanoparticles incorporating gum rosin provided a controlled and sustained release of fluvastatin sodium over 48 hours. In vivo evaluations further supported these findings, as the rosin-containing formulations effectively reduced serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels in hyperlipidemic rat models [

67]. Joshi & Sing (2020) developed a gelatin–rosin gum complex nanoparticles (GGR NPs) via a complex coacervation method followed by glutaraldehyde crosslinking, designed for colon-targeted delivery of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Joshi & Singh, 2020). The optimized nanoparticles is confirmed to has a mesoporous and amorphous structure that facilitates controlled drug encapsulation. In vitro release studies in simulated gastrointestinal fluids demonstrated sustained 5-FU release over 16 hours, following first-order kinetics and a non-Fickian diffusion mechanism, while cytotoxicity assays showed enhanced efficacy of the drug-loaded nanoparticles.

Another study focusing in breast cancer therapy also applied the 5-fluorouracil (5FU) loaded PEG/rosin-pentaerythritol-ester (RPE). In vitro tests on breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) revealed significantly higher cytotoxicity of 5FU-NPs and CAR-NPs at lower concentrations than free 5FU or CAR, while normal HUVEC cells remained largely unaffected. Mechanistic assays further demonstrated that ceramidase (ASAH1) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) expression decreased, alongside reduced Bcl-2, suggesting enhanced induction of apoptosis [

69]. In studies focusing on metabolic disorders, Thymoquinone (TQ) loaded gum rosin nanocapsules, when used in combination with other agents like glycyrrhizin, demonstrated significant antihyperglycemic effects in diabetic rat models by effectively reducing blood glucose levels, glycation of hemoglobin, and improving lipid profiles [

70]. Singh & Malviya (2018) presents a novel strategy to enhance the delayed, colon-specific release of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) by creating hybrid nanoparticles composed of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and gum rosin [

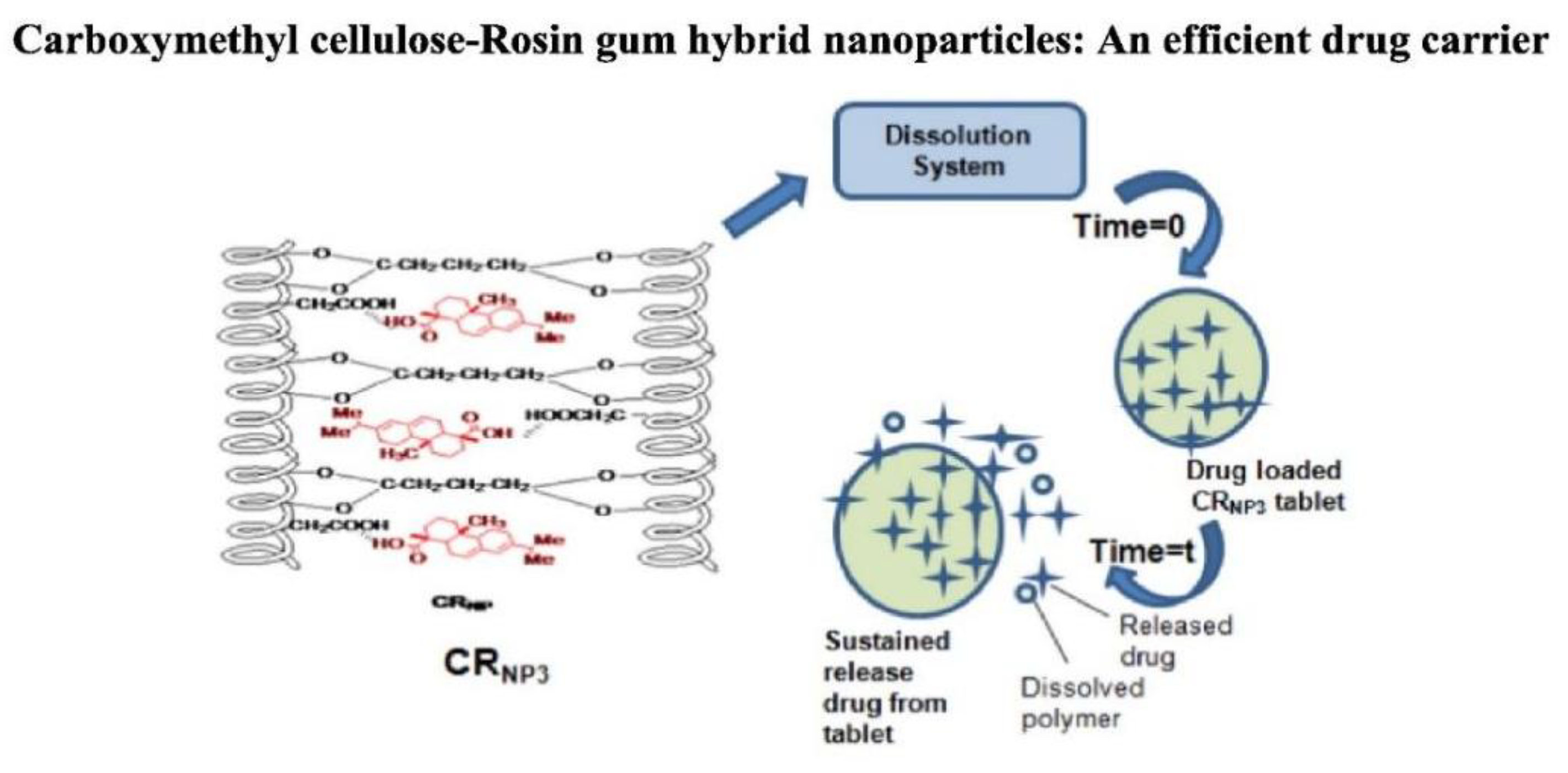

72]. The result showed the potential of the CMC–gum rosin hybrid nanoparticles to delay drug release until the lower GI tract, thereby enhancing local drug bioavailability.

5.6. Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

Targeted drug delivery is one of the most sophisticated strategy in the drug delivery system [

53]. It is one of the realizations of the “magic bullet” concept introduced by Paul Ehrlich, a winner of Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1908. In this concept, drugs can be delivered exactly to the targeted area in the body without affecting healthy cells, tissues, or organs. Hence the amount of the required medicine can be lowered, and the adverse effect to healthy parts can be minimized [

74]. The ability of gum rosin and its derivates as film-forming and matrix forming excipients allowed this material to produce nano- and microparticles, not only for oral administration, but also for parenteral-targeted drug delivery system. Various active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) have been studied and series of studies has explored the versatility of rosin and its derivatives in the field of targeted drug delivery.

5.6.1. Targeted delivery for anticancer drugs

Gum rosin was studied for its potential as carrier for anti-cancer/ chemotherapy drugs. Joshi and Singh (2020) incorporated 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) into gelatine-rosin gum nanoparticles (GGR NPs) and found that 5-FU GGR NPs exhibited first-order kinetics drug release profile and a combination of diffusion and erosion mechanisms. The network configuration of the nanoparticles facilitated a sustained release of the drug, and cytotoxicity evaluations on A549 (lung cancer) cells demonstrated higher toxicity of 5-FU-laden nanoparticles compared to those without drug loading. These findings suggest that the modification of gum rosin in the form of GGR NPs offers a viable and secure approach for delivering chemotherapeutic drugs, with the potential to improve effective effects[

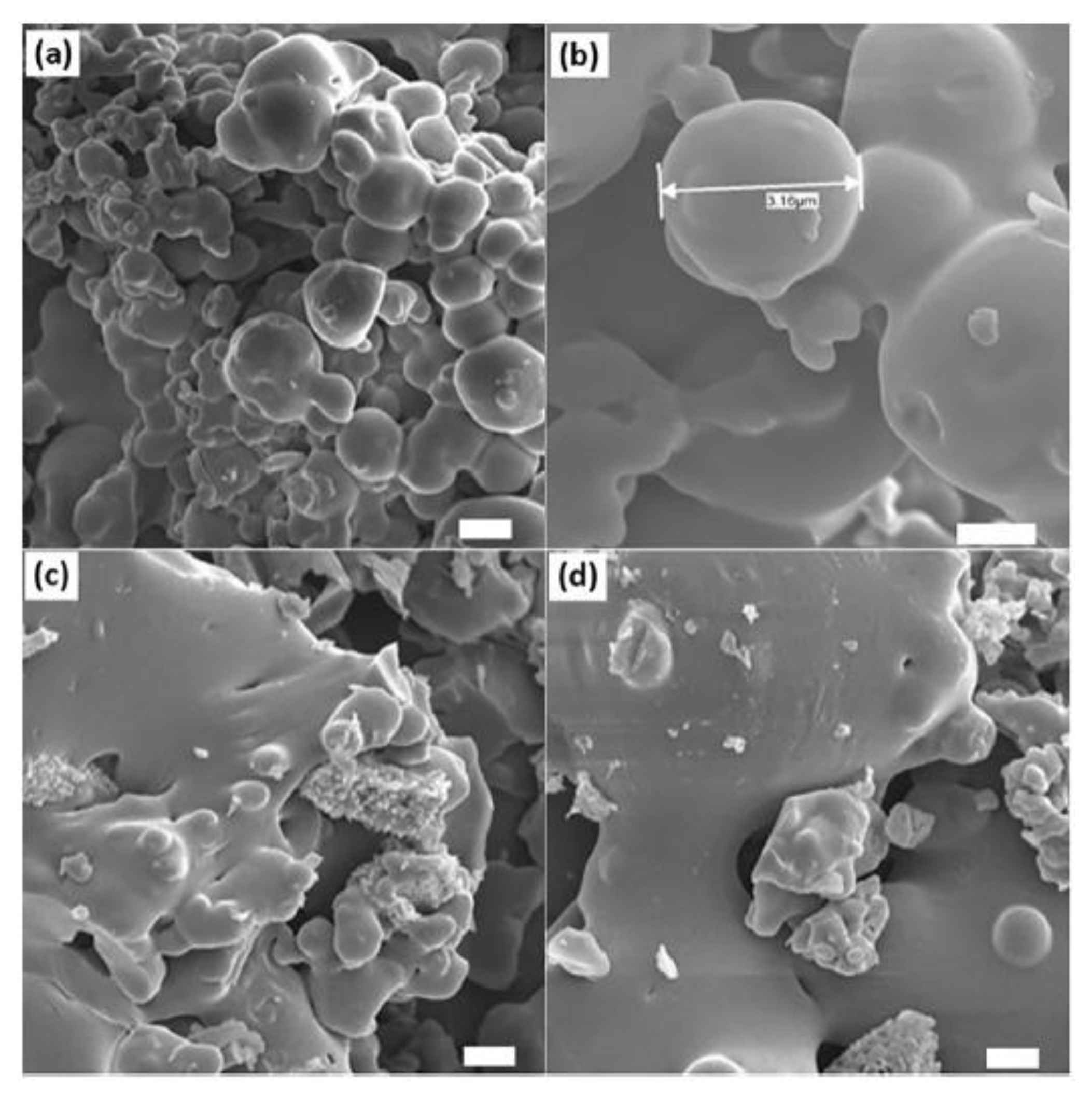

9]. Madhavi et al. (2023) introduced a novel controlled release mechanism for the anticancer agent 6-Thioguanine (6-TG). In this study, 6-Thioguanine (6-TG) was encapsulated in biodegradable microsphere of gum rosin (GR) and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) using double emulsion solvent evaporation technique [

73]. Microspheres with and without the active agent were successfully made, as shown in

Figure 5. The microspheres demonstrated encapsulation efficiencies ranging from 64.32% to 72.42% and the in vitro release profiles exhibited diverse patterns, suggesting the potential for tailoring drug delivery profiles for specific requirements[

73].

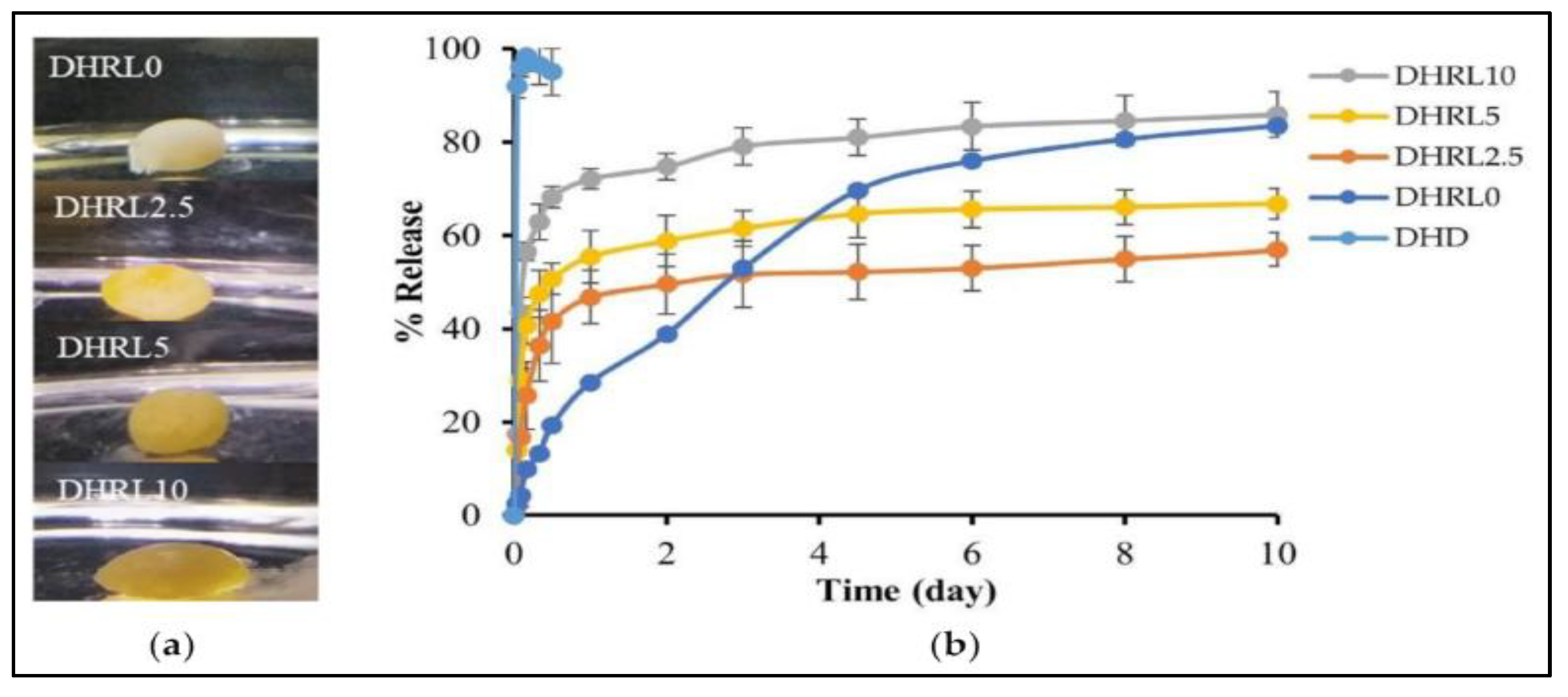

5.6.2. Targeted delivery of 5-ASA, an anti-inflammatory drug

Singh et al. (2018) utilized gum rosin to deliver and control release mechanism of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), an anti-inflammatory medication commonly used for ulcerative colitis treatment. 5-ASA was encapsulated in synthesized hybrid nanoparticles known as carboxymethyl cellulose-rosin gum nanoparticles (CRNP3)[

71]. These nanoparticles exhibited a controlled release of 72% of the drug over 12 hours when exposed to simulated intestinal fluid, contrasting with the complete release of 100% observed between 5 to 8 hours from the original materials.

Figure 6.

Targeted drug delivery of 5-ASA, an anti-inflammatory drug. Reproduced from ref (V. Singh et al., 2018) with permission. Copyright © 2018, Elsevier.

Figure 6.

Targeted drug delivery of 5-ASA, an anti-inflammatory drug. Reproduced from ref (V. Singh et al., 2018) with permission. Copyright © 2018, Elsevier.

Controlled and delayed release mechanisms were identified as advantageous for enhancing the bioavailability of 5-ASA, particularly in the colon. The modification of gum rosin in the form of CRNP3 nanoparticles demonstrated zero-order kinetics and a non-Fickian diffusion mechanism, indicating the potential effectiveness of these hybrid nanoparticles as a targeted drug administration method in the gastrointestinal tract. The concept of this work is depicted in [

71].

5.6.3. Targeted delivery of periodontitis medication

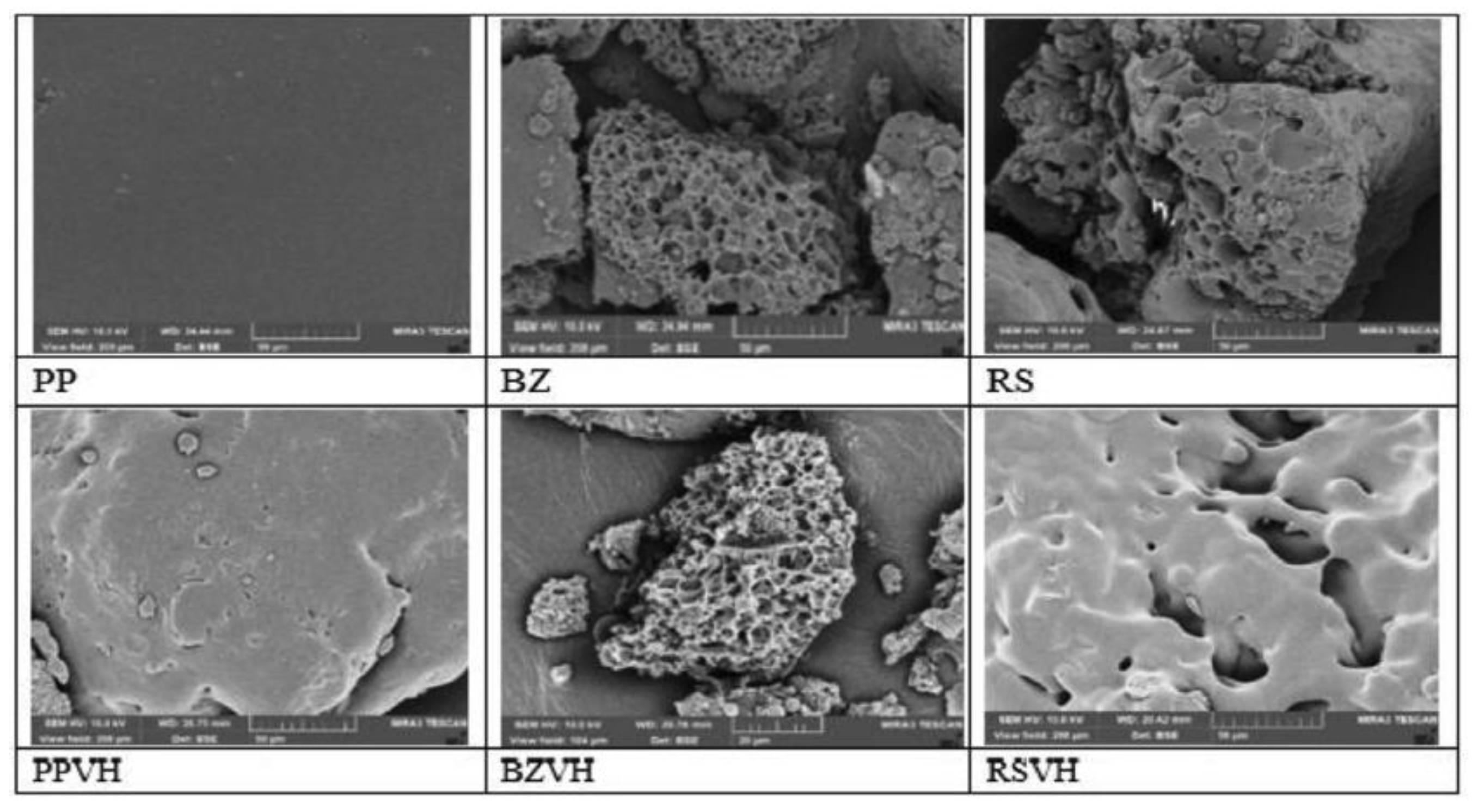

Besides its film-forming ability, gel-forming properties of rosin has been also investigated for its application to form in-situ gel for periodontal disease. Khaing et al. (2021) explored the use of rosin (RS) along with other natural resins including benzoin (BZ) and propolis (PP), in the development of in situ forming gels (ISGs) as a delivery method for vancomycin hydrochloride (VH). 35% w/v of the resins were dissolved in DMSO, and then subjected to solvent exchange procedure with water to form the gels. The study found that the rosin-based ISGs exhibited a pseudo-plastic flow characteristic, contributing to the injectability and mechanical properties. However, in comparison to benzoin and propolis-based ISGs, rosin-based ISGs slower release of VH. SEM images of dried gels based on RS and BZ indicated the presence of homogeneous porous system, while pores did not appear on PP-based gels (

Figure 7). The images of dried VH-loaded gels after drug release showed that the BZ-based gel contained more pores than the RS-based gel, indicating that more VH left the BZ-based ISG than the other. VH was deposited on the surface of PP-based ISG, enabling its relatively easy release [

77].

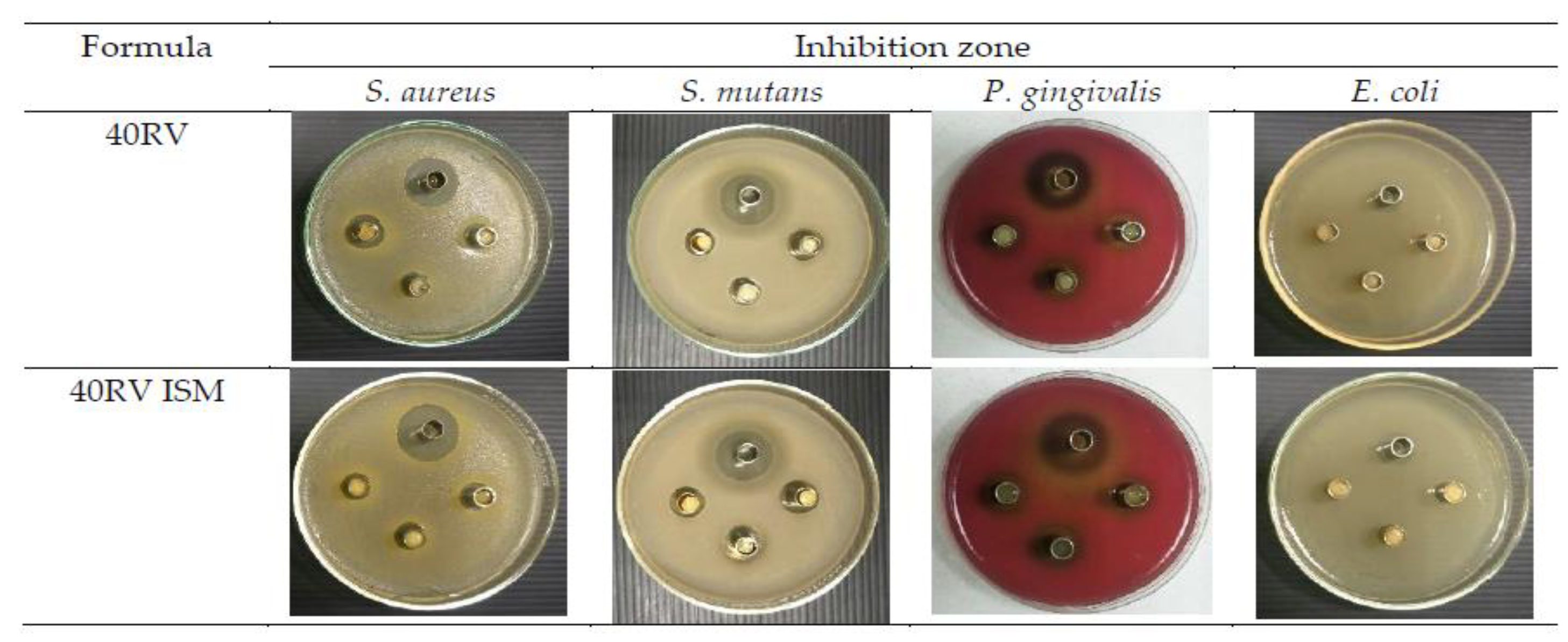

The study to utilize rosin as an ISG was continued by the same group, as reported by Chuenbarn et al. in 2022. Rosin was chosen because it prevented initial VH release, which is important to prevent side effects and antibiotic resistance. This study successfully showed the effectiveness of rosin-based ISG and in situ forming microparticles (ISM) as localized delivery vehicles for VH. ISG was made using the same procedure as the previous study [

76] with varied rosin concentration. ISM was produced from a mixture of rosin solution with a solution of glyceryl monostearate in olive oil as an external oil phase. The study found that both ISG and ISM exhibited a pH range of 5.02 to 6.48, ease of injectability, and satisfactory stability, with ISM showing enhanced injection performance due to the lubricating properties of the external oil phase. The modification of gum rosin in these systems resulted in formulations that demonstrated flexibility throughout the phase change process, allowing them to conform to the contours of a patient’s gum cavity. Moreover, the concentration of rosin influenced the size of microparticles, and formulations with higher rosin concentrations exhibited higher ability to delay the drug release.

Figure 8 shows the bacteria-inhibiting test of ISG with 40% rosin (40RV) and ISM with an equivalent rosin concentration (40RV ISM), compared to a saline solution (yielding in large inhibition areas). The small inhibition areas made by the ISM and ISG demonstrated the delayed drug release, which were effective against S. mutans and P. gingivalis [

78].

Rosin-based in-situ forming gel was also used in delivering doxycycline hyclate (HC) and lime peel oil as a prospective injectable therapy for localized treatment of periodontitis. 55% w/w of rosin was dissolved in DMSO and N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP) solvents, along with doxycycline hyclate and varied amount of lime peel oil. As shown in

Figure 9, the inclusion of LO was seen to decelerate the process of gel formation, marginally elevate viscosity and injectability, diminish gel hardness, and augment adhesion. The drug release exhibited a non-Fickian diffusion mechanism and demonstrated greater efficacy in the formulation with LO addition throughout a 10-day timeframe. Significantly, the incorporation of a 10% LO concentration demonstrated enhanced antibacterial properties against Porphyromonas gingivalis and Staphylococcus aureus in the formulation, suggesting the potential utility of LO in the efficacious management of periodontitis [

80].

6. Challenges of Gum Rosin as Pharmaceutical Excipient for Frug Delivery System

6.1. Allergenic Activity and Occupational Exposure

The allergenic potential of gum rosin is primarily attributed to the presence of oxidized resin acids—especially those of the abietadiene-type—that form when rosin is exposed to air. Karlberg et al. (1988) identified 15-Hydroperoxyabietic acid, an oxidation product, as a prominent allergen in unaltered gum rosin [

82]. Several subsequent studies have successfully isolated and identified various oxidized resin acids as contact allergens [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Although chemical modifications such as hydrogenation and esterification with polyalcohols can reduce the sensitizing potential of rosin, concerns regarding the allergenic effects of unmodified rosin persist in many products even after such modifications [

89,

90,

91,

92]. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) associated with rosin—commonly known as colophonium in the International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients (INCI)—is a well-documented adverse reaction. In clinical settings, patch testing with a 20% concentration of gum rosin in petrolatum is routinely used to identify individuals sensitive to rosin [

93]. Epidemiological studies have reported a prevalence of rosin hypersensitivity ranging from 0.45% to 2.0% in various European populations, with data from Germany indicating rates between 0.6% and 1.4% over a 10-year period. Moreover, several studies from Denmark, Sweden, and other European countries have noted a higher incidence of rosin allergy in teenagers and older individuals, likely due to prolonged or repeated exposure [

94,

95,

96,

97,

98].

Occupational exposure further exacerbates the risk of rosin-induced allergic reactions. Workers handling rosin-containing products—such as adhesives, leg ulcer treatments, epilating waxes, cosmetics, and shoe linings—are particularly vulnerable to developing ACD [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104]. Additionally, musicians (especially string and percussion instrument players), soldering workers in the electronics industry, textile workers, and machinists exposed to rosin in metalworking fluids face an increased risk of contact dermatitis. The potential for exposure is also elevated in industries dealing with paper products, diapers, and sanitary pads, as well as in certain wooden items like toilet seats [

105,

106,

107]. Furthermore, inhalation of rosin fumes has been linked to occupational asthma; for instance, Elms et al. (2005) reported that approximately 5% of newly diagnosed cases of occupational asthma in the United Kingdom in 1994 were related to exposure to rosin-containing solder vapors[

108]. This respiratory reaction is thought to be mediated by IgE antibodies, which can induce airway inflammation and bronchoconstriction[

108].

6.2. Other Challenging Characteristics

Besides its potentially allergic-inducing nature, gum rosin also exhibits several challenging characteristics. Its melting point of 70 - 85°C and its hydrophobic nature provides suitable characteristics as matrix and coating materials for various controlled-release dosage forms includes tablets, microcapsules, nanoparticles and films. However, the film obtained from rosin gum is brittle, non-flexible and highly hydrophobic. Unmodified rosin film was found to be too hydrophobic, too brittle, and containing pores that allow for relatively high water-vapor transmission rate when applied as drugs coating [

59]. Gum rosin is able to retain the drug release up to more than 24 hours. This may lead to over-retained drug release from the dosage forms and cause insufficient drug concentration in the site of action/ site of absorption. Therefore, gum rosin was never applied as a single excipient, especially for oral-administered dosage forms. Furthermore, it is important to modify its structure to improve the functional characteristics of gum rosin.

7. Strategies to Optimize the Application of Gum Rosin

In order to expand the application of gum rosin, its functional characteristics should be improved. There are several strategies can be employed, including performing physical and chemical modification on gum rosin. Combining gum rosin with other polymers such as ethyl cellulose [

55] and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [

66] have been proved to be effective to improve functional characteristics the obtained film. Furthermore, combinations of gum rosin with gelatine [

9]produced nanoparticles with controlled release drug profile, while its combination with carboxymethyl cellulose successfully produced colon-targeting dosage forms which exhibit zero-order kinetics and a non-Fickian diffusion mechanism [

71]. Addition of plasticizer such as PEG 400 or dibutyl phthalate successfully further improved the flexibility of the film matrices. Chemical modification of gum rosin further improved its characteristics. Modification of gum rosin into rosin pentaerythritol ester (RPE) resulted in coating film with exceptional moisture protection properties and satisfactory controlled release profile in the simulated intestinal fluid [

60]. These studies showed that physical and chemical modification on gum rosin may result in materials with better characteristics, thus open new opportunities to use these modified substances for broader applications in pharmaceutical fields.

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, rosin, a natural resin extracted from pine trees, has proven to be a remarkably versatile and valuable resource across various industries. Its applications in textiles have led to the development of antimicrobial cotton textiles, green biopolymer packaging nanocomposites, and protective coatings for wood, enhancing durability and functionality. Within the pharmaceutical field, rosin’s significance is highlighted by its role in controlled drug delivery, enabling precise regulation of drug release, as well as in targeted drug delivery systems with tailored release profiles. Furthermore, rosin-based nanogels have demonstrated potential in the development of effective antimicrobial drugs. Rosin’s natural origin, biocompatibility, and diverse range of properties position it as a key asset with multifaceted utility, contributing to advancements in both textile and pharmaceutical industries. Physical and chemical modification on gum rosin might improve its characteristics to be suitable for various dosage forms. Its continued exploration and innovative applications hold promise for further advancements in these fields and beyond.

Author Contributions

Sonita A.P. Siboro: Writing - Original Draft, investigation, and visualization. Sabrina Aufar Salma: visualization, Writing – Review and Editing. Syuhada: Investigation. Kurnia Sari Setio Putri: Investigation, Writing – Review and Editing. Frita Yuliati: Writing - Original Draft, Supervision. Won Ki Lee: Investigation. Kwon Taek Lim: Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Research Organization for Nanotechnology and Materials – National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) research grant 2025. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF-2023R1A2C1002954).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Ni, C.; Yu, L. Preparation and Evaluation of Natural Rosin-Based Zinc Resins for Marine Antifouling. Prog Org Coat 2021, 157, 106270. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Tai, H.-C. String Theories: Chemical Secrets of Italian Violins and Chinese Guqins. AsiaChem Magazine 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kugler, S.; Ossowicz, P.; Malarczyk-Matusiak, K.; Wierzbicka, E. Advances in Rosin-Based Chemicals: The Latest Recipes, Applications and Future Trends. Molecules 2019, 24, 1651. [CrossRef]

- Morkhade, D.M.; Nande, V.S.; Barabde, U. V; Joshi, S.B. Study of Biodegradation and Biocompatibility of PEGylated Rosin Derivatives. J Bioact Compat Polym 2017, 32, 628–640. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.R.; Mahendra, V.; Sousa, D. Biopolymers Based on Rosin. Curr Res Biopolymers 2018, 2018.

- Mardiah, M.; Samadhi, T.W.; Wulandari, W.; Aqsha, A.; Situmorang, Y.A.; Indarto, A. Recent Progress on Catalytic of Rosin Esterification Using Different Agents of Reactant. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 2155–2169. [CrossRef]

- Kanlaya, P.; Sumrit, W.; Amorn, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Water Soluble Rosin-Polyethylene Glycol 1500 Derivative. International Journal of Chemical Engineering and Applications 2016, 7, 277–281. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, J.K.; Chandel, A.K.; Sharma, L.; Mallick, N.; Singh, S.P. Biomedical Applications of Microbially Engineered Polyhydroxyalkanoates: An Insight into Recent Advances, Bottlenecks, and Solutions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 103, 2007–2032. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Singh, V. Gelatin–Rosin Gum Complex Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization and Colon Targeted Delivery of 5-Fluorouracil. Chemical Papers 2020, 74, 4241–4252. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.K.; Gidwani, B.; Vyas, A. Rosin: Recent Advances and Potential Applications in Novel Drug Delivery System. J Bioact Compat Polym 2016, 31, 111–126. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.K.; Gidwani, B.; Vyas, A. Rosin: Recent Advances and Potential Applications in Novel Drug Delivery System. J Bioact Compat Polym 2016, 31, 111–126. [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, V. Rosin Product Review. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2019, 890, 77–91. [CrossRef]

- Pratapwar, A.S.; Sakarkar, D.M. Applications of Rosin Derivatives in the Development of Novel Drug Delivery System (NDDS): A Contemporary View. Journal of Quality Assurance and Pharma Analysis 2015, 1, 100–109.

- Yamaguchi, T.; Nasu, D.; Masani, K. Effect of Grip-Enhancing Agents on Sliding Friction between a Fingertip and a Baseball. Commun Mater 2022, 3, 92. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Yan, Q.; Fu, H. Study on Novel Rosin-based Polyurethane Reactive Hot Melt Adhesive. Polym Adv Technol 2021, 32, 4415–4423. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Kundu, S.; Debnath, S. Tall Oil Rosin: A Substitute for Gum Rosin in Development of Offset Printing Ink. NIP & Digital Fabrication Conference 2018, 34, 44–48. [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.S.F.; Bilatto, S.; Paschoalin, R.T.; Soares, A.C.; Moreira, F.K.V.; Oliveira, O.N.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Bras, J. Eco-Friendly Gelatin Films with Rosin-Grafted Cellulose Nanocrystals for Antimicrobial Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 165, 2974–2983. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Abdalkarim, S.Y.H.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, Y. Bifunctional Reinforcement of Green Biopolymer Packaging Nanocomposites with Natural Cellulose Nanocrystal–Rosin Hybrids. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3, 1944–1954. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, H.; El Kissi, N.; Abou-Kandil, A.I.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; Dufresne, A. PLA/PBAT Bionanocomposites with Antimicrobial Natural Rosin for Green Packaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9, 20132–20141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; An, X.; Liu, H.; Nie, S.; Cao, H.; Xu, Q.; Lu, B. Improving Sizing Performance of Middle Layer of Liquid Packaging Board Containing High-Yield Pulp. Cellulose 2020, 27, 4707–4719. [CrossRef]

- Bezzekhami, M.A.; Belalia, M.; Hamed, D.; Bououdina, M.; Berfai, B.B.; Harrane, A. Nanoarchitectonics of Starch Nanoparticles Rosin Catalyzed by Algerian Natural Montmorillonite (Maghnite-H+) for Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater 2023, 33, 193–206. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Shang, S.; Song, Z.; Song, J. Preparation and Properties of Room Temperature Vulcanized Silicone Rubber Based on Rosin-Grafted Polydimethylsiloxane. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 14684–14693. [CrossRef]

- Rosu, L.; Mustata, F.; Rosu, D.; Varganici, C.-D.; Rosca, I.; Rusu, T. Bio-Based Coatings from Epoxy Resins Crosslinked with a Rosin Acid Derivative for Wood Thermal and Anti–Fungal Protection. Prog Org Coat 2021, 151, 106008. [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Degen, G.; Engel, K.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; Husøy, T.; Manco, M.; et al. Follow-up of the Re-evaluation of Glycerol Esters of Wood Rosins (E 445) as a Food Additive. EFSA Journal 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sapbamrer, R.; Naksata, M.; Hongsibsong, S.; Chittrakul, J.; Chaiut, W. Efficiency of Gum Rosin-Coated Personal Protective Clothing to Protect against Chlorpyrifos Exposure in Applicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 2594. [CrossRef]

- Naksata, M.; Watcharapasorn, A.; Hongsibsong, S.; Sapbamrer, R. Development of Personal Protective Clothing for Reducing Exposure to Insecticides in Pesticide Applicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3303. [CrossRef]

- Phun, L.; Snead, D.; Hurd, P.; Jing, F. Industrial Applications of Pine-Chemical-Based Materials. In Sustainable Polymers from Biomass; Wiley, 2017; pp. 151–179.

- Gu, S.; Liu, M.; Xu, R.; Han, X.; Lou, Y.; Kong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Shang, S.; Song, Z.; Song, J.; et al. Ecofriendly Controlled-Release Insecticide Carrier: PH-/Temperature-Responsive Rosin-Derived Hydrogels for Avermectin Delivery against Mythimna Separata (Walker). Langmuir 2024, 40, 10992–11010. [CrossRef]

- Vainio-Kaila, T.; Hänninen, T.; Kyyhkynen, A.; Ohlmeyer, M.; Siitonen, A.; Rautkari, L. Effect of Volatile Organic Compounds from Pinus Sylvestris and Picea Abies on Staphylococcus Aureus, Escherichia Coli, Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Holzforschung 2017, 71, 905–912. [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.M.; Awadallah-F, A.; Azzam, A.M.; Mady, A.H. Influence of Gamma Irradiation on Rosin Properties and Its Antimicrobial Activity. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4500. [CrossRef]

- Sipponen, A.; Peltola, R.; Jokinen, J.J.; Laitinen, K.; Lohi, J.; Rautio, M.; Männistö, M.; Sipponen, P.; Lounatmaa, K. Effects of Norway Spruce (Picea Abies) Resin on Cell Wall and Cell Membrane of Staphylococcus Aureus. Ultrastruct Pathol 2009, 33, 128–135. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, Z.; Mushtaq, M.; Ajab, Z.; Guan, Q.; Mahnashi, M.H.; Alqahtani, Y.S.; Ahmad, B. Rosin Maleic Anhydride Adduct Antibacterial Activity against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Polímeros 2020, 30, e2020022. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, M.; Matrenichev, V.; Layek, R.; Takala, T.M.; Laurikainen, P.; Sarlin, E.; Elert, A.M.; Yudin, V.; Seitsonen, J.; Ruokolainen, J.; et al. Comparison of Rosin and Propolis Antimicrobials in Cellulose Acetate Fibers against Staphylococcus Aureus. Bioresources 2020, 15, 3756–3773. [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Lata, R.; Rohindra, D. Study of Mechanical, Enzymatic Degradation and Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(Butylene Succinate)/Pine-Resin Blends. Polymer Bulletin 2020, 77, 3621–3635. [CrossRef]

- Bezzekhami, M.A.; Belalia, M.; Hamed, D.; Bououdina, M.; Berfai, B.B.; Harrane, A. Nanoarchitectonics of Starch Nanoparticles Rosin Catalyzed by Algerian Natural Montmorillonite (Maghnite-H+) for Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater 2023, 33, 193–206. [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, R.; Woo-il, B.; Navamathavan, R.; Kalpana, D.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.Y. Influence of Antimicrobial Additives on the Formation of Rosin Nanofibers via Electrospinning. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2013, 104, 262–267. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, M.; Puolakka, A.; Takala, T.M.; Elert, A.M.; Mylläri, V.; Jönkkäri, I.; Sarlin, E.; Seitsonen, J.; Ruokolainen, J.; Saris, P.; et al. Antibacterial Polymer Fibres by Rosin Compounding and Melt-Spinning. Mater Today Commun 2019, 20, 100527. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, M.; Puolakka, A.; Takala, T.M.; Elert, A.M.; Mylläri, V.; Jönkkäri, I.; Sarlin, E.; Seitsonen, J.; Ruokolainen, J.; Saris, P.; et al. Antibacterial Polymer Fibres by Rosin Compounding and Melt-Spinning. Mater Today Commun 2019, 20, 100527. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Ma, L.; Shang, S.; Song, Z. Construction of Antimicrobial and Biocompatible Cotton Textile Based on Quaternary Ammonium Salt from Rosin Acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 150, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.P.; Yao, K.; Wilbon, P.A.; Zhang, W.; Ren, L.; Zhou, J.; Nagarkatti, M.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; et al. Robust Antimicrobial Compounds and Polymers Derived from Natural Resin Acids. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 916–918. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, R.; Sharma, R.; Maiti, M.; Kaur, A.; Sharma, P.; Mishra, V.; Jana, A.K. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Reduced Gum Rosin-Acrylamide Copolymer-Based Nanogel and Their Investigation for Antibacterial Activity. Polymer Bulletin 2017, 74, 2995–3014. [CrossRef]

- Fei, B.L.; Tu, S.; Wei, Z.; Wang, P.; Qiao, C.; Chen, Z.F. Optically Pure Chiral Copper(II) Complexes of Rosin Derivative as Attractive Anticancer Agents with Potential Anti-Metastatic and Anti-Angiogenic Activities. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 176, 175–186. [CrossRef]

- El-Hallouty, M.S.; Soliman, A.F.A.; Nassrallah, A.; Salamatullah, A.; Alkaltham, S.M.; Kamal, Y.K.; Hanafy, A.E.; Gaballa, S.H.; Aboul-Soud, A.M.M. Crude Methanol Extract of Rosin Gum Exhibits Specific Cytotoxicity against Human Breast Cancer Cells via Apoptosis Induction. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2020, 20, 1028–1036.

- Gumelar, M.D.; Putri, N.A.; Anggaravidya, M.; Anawati, A. Corrosion Behavior of Biodegradable Material AZ31 Coated with Beeswax-Colophony Resin. AIP Conf Proc 2018, 1964, 20035. [CrossRef]

- Abou Neel, E.A.; Aljabo, A.; Strange, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Coathup, M.; Young, A.M.; Bozec, L.; Mudera, V. Demineralization-Remineralization Dynamics in Teeth and Bone. Int J Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 4743–4763. [CrossRef]

- TULUMBACI, F.; GUNGORMUS, M. In Vitro Remineralization of Primary Teeth with a Mineralization-Promoting Peptide Containing Dental Varnish. Journal of Applied Oral Science 2020, 28.

- Durmuş, E.; Kölüş, T.; Çoban, E.; Yalçınkaya, H.; Ülker, H.E.; Çelik, İ. In Vitro Determination of the Remineralizing Potential and Cytotoxicity of Non-Fluoride Dental Varnish Containing Bioactive Glass, Eggshell, and Eggshell Membrane. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2023, 24, 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Vargason, A.M.; Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. The Evolution of Commercial Drug Delivery Technologies. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 5, 951–967. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Otte, A.; Park, K. Evolution of Drug Delivery Systems: From 1950 to 2020 and Beyond. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 342, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Jelvehgari, M.; Montazam, S.H. Comparison of Microencapsulation by Emulsion-Solvent Extraction/ Evaporation Technique Using Derivatives Cellulose and Acrylate- Methacrylate Copolymer as Carriers. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2012, 7, 144–152.

- Geraili, A.; Xing, M.; Mequanint, K. Design and Fabrication of Drug-Delivery Systems toward Adjustable Release Profiles for Personalized Treatment. View 2021, 2, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yao, K.; Lee, J.; Chandler, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; Tang, C. Well-Defined Renewable Polymers Derived from Gum Rosin. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 5922–5924. [CrossRef]

- Tewabe, A.; Abate, A.; Tamrie, M.; Seyfu, A.; Abdela Siraj, E. Targeted Drug Delivery — From Magic Bullet to Nanomedicine: Principles, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. J Multidiscip Healthc 2021, Volume 14, 1711–1724. [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa-Ramírez, H.; Dominici, F.; Ferri, J.M.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Pentaerythritol and Glycerol Esters Derived from Gum Rosin as Bio-Based Additives for the Improvement of Processability and Thermal Stability of Polylactic Acid. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 5446–5461. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S. Rosin Microspheres as Taste Masking Agent in Oral Drug Delivery System. IJPSR 2012, 3, 3116–3124.

- M.P., R.; G.R., K.; R.S., A. Natural Polymers in Fast Dissolving Tablets. Res J Pharm Technol 2021, 2859–2866. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Qing, Y.; Wu, Y. Rosin Acid and SiO2 Modified Cotton Fabric to Prepare Fluorine-Free Durable Superhydrophobic Coating for Oil-Water Separation. J Hazard Mater 2022, 440, 129797. [CrossRef]

- Zaoui, A.; Mahendra, V.; Mitchell, G.; Cherifi, Z.; Harrane, A.; Belbachir, M. Design, Synthesis and Thermo-Chemical Properties of Rosin Vinyl Imidazolium Based Compounds as Potential Advanced Biocompatible Materials. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 3723–3730. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Y. V.; Nikore, R.L.; Dorle, A.K. Study of Rosin and Rosin Esters as Coating Materials. Int J Pharm 1985, 24, 351–354. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Y.V.; Dorle, A.K. Study of Rosin and Rosin Derivatives as Coating Materials for Controlled Release of Drug. Journal of Controlled Release 1987, 5, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Y. V.; Dorle, A.K. Study of Rosin and Rosin Derivatives as Coating Materials for Controlled Release of Drug. Journal of Controlled Release 1987, 5, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Burakale, P.; Sudke, S.; Bhise, M.; Tare, H.; Kachave, R. Exploring Film Forming Ability of Newly Synthesized Rosin Esters. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG DELIVERY TECHNOLOGY 2023, 13, 908–912. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Liu, L. Preparation and Application of Rosin@apatite Hybrid Material with New Natural Surfactants Based on In-Situ Reaction by Sol-Gel Method. Mater Res Express 2024, 11, 075003. [CrossRef]

- Thivya, P.; Durgadevi, M.; Sinija, V.R.N. Biodegradable Medicated Chewing Gum: A Modernized System for Delivering Bioactive Compounds. Future Foods 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.P.; Joshi, S.B. Formulation Development of Chewing Gum as a Novel Drug Delivery System for Diltiazem Hydrochloride. Indian Drugs 2006, 43, 724–728.

- Satturwar, P.M.; Fulzele, S. V.; Dorle, A.K. Evaluation of Polymerized Rosin for the Formulation and Development of Transdermal Drug Delivery System: A Technical Note. AAPS PharmSciTech 2005, 6, E649–E654. [CrossRef]

- Gudigennavar, A.S.; Chandragirvar, P.C.; Gudigennavar, A.S. Role of Fluvastatin Sodium Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Hyperlipidemia: Fabrication and Characterization. German Journal of Pharmaceuticals and Biomaterials 2023, 1, 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Singh, V. Gelatin–Rosin Gum Complex Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization and Colon Targeted Delivery of 5-Fluorouracil. Chemical Papers 2020, 74, 4241–4252. [CrossRef]

- Danışman-Kalındemirtaş, F.; Birman, H.; Karakuş, S.; Kilislioğlu, A.; Erdem-Kuruca, S. Preparation and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Fluorouracil and Carmofur Loaded Polyethylene Glycol / Rosin Ester Nanocarriers as Potential Anticancer Agents and Ceramidase Inhibitors. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2022, 73, 103456. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, C.; Rathbone, M.J.; Chellappan, D.K.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Pinto, T.D.J.A.; Dureja, H.; Hemrajani, C.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K.; Negi, P. Nanocarriers: More than Tour de Force for Thymoquinone. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2020, 17, 479–494. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Joshi, S.; Malviya, T. Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Rosin Gum Hybrid Nanoparticles: An Efficient Drug Carrier. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 112, 390–398. [CrossRef]

- Strebhardt, K.; Ullrich, A. Paul Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet Concept: 100 Years of Progress. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8, 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, C.; Kumara Babu, P.; Sreekanth Reddy, O.; Ujwala, G.; Subha, M.C.S. Formulation and Evaluation of 6-Thioguanine-Loaded Gum Rosin/ Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Blend Microspheres for Controlled Release Applications. Mater Today Proc 2023, 92, 892–898. [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, C.; Kumara Babu, P.; Sreekanth Reddy, O.; Ujwala, G.; Subha, M.C.S. Formulation and Evaluation of 6-Thioguanine-Loaded Gum Rosin/ Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Blend Microspheres for Controlled Release Applications. Mater Today Proc 2023, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Joshi, S.; Malviya, T. Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Rosin Gum Hybrid Nanoparticles: An Efficient Drug Carrier. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 112, 390. [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Intaraphairot, T.; Chuenbarn, T.; Chantadee, T.; Phaechamud, T. Natural Resin-Based Solvent Exchange Induced in-Situ Forming Gel for Vancomycin HCl Delivery to Periodontal Pocket. Mater Today Proc 2021, 47, 3585–3593. [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Intaraphairot, T.; Chuenbarn, T.; Chantadee, T.; Phaechamud, T. Natural Resin-Based Solvent Exchange Induced in-Situ Forming Gel for Vancomycin HCl Delivery to Periodontal Pocket. Mater Today Proc 2021, 47, 3585–3593. [CrossRef]

- Chuenbarn, T.; Sirirak, J.; Tuntarawongsa, S.; Okonogi, S.; Phaechamud, T. Design and Comparative Evaluation of Vancomycin HCl-Loaded Rosin-Based In Situ Forming Gel and Microparticles. Gels 2022, 8, 231. [CrossRef]

- Chuenbarn, T.; Sirirak, J.; Tuntarawongsa, S.; Okonogi, S.; Phaechamud, T. Design and Comparative Evaluation of Vancomycin HCl-Loaded Rosin-Based In Situ Forming Gel and Microparticles. Gels 2022, 8, 231. [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Mahadlek, J.; Okonogi, S.; Phaechamud, T. Lime Peel Oil–Incorporated Rosin-Based Antimicrobial In Situ Forming Gel. Gels 2022, 8, 169. [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Mahadlek, J.; Okonogi, S.; Phaechamud, T. Lime Peel Oil–Incorporated Rosin-Based Antimicrobial In Situ Forming Gel. Gels 2022, 8, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A. -T; Bohlinder, K.; Boman, A.; Hacksell, U.; Hermansson, Jö.; Jacobsson, S.; Nilsson, J.L.G. Identification of 15-Hydroperoxyabietic Acid as a Contact Allergen in Portuguese Colophony. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 1988, 40, 42–47. [CrossRef]

- GÄfvert, E.; Nilsson, U.; Karlberg, A.T.; Magnusson, K.; Nilsson, J.L.G. Rosin Allergy: Identification of a Dehydroabietic Acid Peroxide with Allergenic Properties. Arch Dermatol Res 1992, 284, 409–413. [CrossRef]

- Gäfvert, E.; Shao, L.P.; Karlberg, A.T.; Nilsson, U.; Nilsson, J.L.G. Contact Allergy to Resin Acid Hydroperoxides. Hapten Binding via Free Radicals and Epoxides. Chem Res Toxicol 1994, 7, 260–266. [CrossRef]

- Hausen, B.M.; Hessling, C. Contact Allergy Due to Colophony (VI). The Sensitizing Capacity of Minor Resin Acids and 7 Commercial Modified-Colophony Products. Contact Dermatitis 1990, 23, 90–95. [CrossRef]

- Sadhra, S.; Foulds, I.S.; Gray, C.N. Identification of Contact Allergens in Unmodified Rosin Using a Combination of Patch Testing and Analytical Chemistry Techniques. British Journal of Dermatology 1996, 134, 662–668. [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.P.; Gäfvert, E.; Nilsson, U.; Karlberg, A.T.; Nilsson, J.L.G. 15-Hydroperoxydehydroabietic Acid-a Contact Allergen in Colophony from Pinus Species. Phytochemistry 1995, 38, 853–857. [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Saeed, M.A. 13β, 14β-Dihydroxy-13α-isopropylabietic Acid, an Elicitor of Contact Allergy. J Pharm Sci 1994, 83, 909–910. [CrossRef]

- Gäfvert, E.; Shao, L.P.; Karlberg, A.; Nilsson, U.; Nilsson, J.L.G. Allergenicity of Rosin (Colophony) Esters. Contact Dermatitis 1994, 31, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Illing, H.P.A.; Malmfors, T.; Rodenburg, L. Skin Sensitization and Possible Groupings for ‘Read across’ for Rosin Based Substances. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2009, 54, 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A.; Lidén, C. Comparison of Colophony Patch Test Preparations. Contact Dermatitis 1988, 18, 158–165. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, C.C.; Tucker, S.C.; Gäfvert, E.; Karlberg, A. -T.; Beck, M.H. Contact Dermatitis from Modified Rosin in Footwear. Contact Dermatitis 1999, 41, 102–103. [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A.; Lidén, C. Comparison of Colophony Patch Test Preparations. Contact Dermatitis 1988, 18, 158–165. [CrossRef]

- Schnuch, A.; Uter, W.; Geier, J.; Gefeller, O. Epidemiology of Contact Allergy: An Estimation of Morbidity Employing the Clinical Epidemiology and Drug-Utilization Research (CE-DUR) Approach. Contact Dermatitis 2002, 47, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Linneberg, A.; Menné, T.; Johansen, J.D. The Epidemiology of Contact Allergy in the General Population - Prevalence and Main Findings. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 57, 287–299. [CrossRef]

- Diepgen, T.L.; Ofenloch, R.F.; Bruze, M.; Bertuccio, P.; Cazzaniga, S.; Coenraads, P.J.; Elsner, P.; Goncalo, M.; Svensson; Naldi, L. Prevalence of Contact Allergy in the General Population in Different European Regions. British Journal of Dermatology 2016, 174, 319–329. [CrossRef]

- Lagrelius, M.; Wahlgren, C.F.; Matura, M.; Kull, I.; Lidén, C. High Prevalence of Contact Allergy in Adolescence: Results from the Population-Based BAMSE Birth Cohort. Contact Dermatitis 2016, 74, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Mortz, C.G.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Andersen, K.E. Prevalence, Incidence Rates and Persistence of Contact Allergy and Allergic Contact Dermatitis in the Odense Adolescence Cohort Study: A 15-Year Follow-Up. British Journal of Dermatology 2013, 168, 318–325. [CrossRef]

- Barbaud, A.; Collet, E.; Le Coz, C.J.; Meaume, S.; Gillois, P. Contact Allergy in Chronic Leg Ulcers: Results of a Multicentre Study Carried out in 423 Patients and Proposal for an Updated Series of Patch Tests. Contact Dermatitis 2009, 60, 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Christoffers, W.A.; Coenraads, P.J.; Schuttelaar, M.L. Bullous Allergic Reaction Caused by Colophonium in Medical Adhesives. Contact Dermatitis 2014, 70, 256–257. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, A.; Armingaud, P.; Avenel-Audran, M.; Begon-Bagdassarian, I.; Constandt, L.; Giordano-Labadie, F.; Girardin, P.; Coz, C.J.L.E.; Milpied-Homsi, B.; Nootens, C.; et al. An Epidemic of Allergic Contact Dermatitis Due to Epilating Products. Contact Dermatitis 2002, 47, 67–70. [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.; Leow, Y.H.; Goh, C.L. Occupational Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Singapore. Science of The Total Environment 2001, 270, 97–101. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Gao, B.A.; Cheng, H.Y.; Li, L.F. Survey of Occupational Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Patch Test among Clothing Employees in Beijing. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Suuronen, K.; Aalto-Korte, K.; Piipari, R.; Tuomi, T.; Jolanki, R. Occupational Dermatitis and Allergic Respiratory Diseases in Finnish Metalworking Machinists. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2007, 57, 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A.T.; Gäfvert, E.; Lidén, C. Environmentally Friendly Paper May Increase Risk of Hand Eczema in Rosin-Sensitive Persons. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995, 33, 427–432. [CrossRef]

- Raison-Peyron, N.; Nilsson, U.; Du-Thanh, A.; Karlberg, A.T. Contact Dermatitis from Unexpected Exposure to Rosin from a Toilet Seat. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 149–150. [CrossRef]

- Wujanto, L.; Wakelin, S. Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Colophonium in a Sanitary Pad - An Overlooked Allergen? Contact Dermatitis 2012, 66, 161–162. [CrossRef]

- Elms, J.; Fishwick, D.; Robinson, E.; Burge, S.; Huggins, V.; Barber, C.; Williams, N.; Curran, A. Specific IgE to Colophony? Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2005, 55, 234–237. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Y. V.; Dorle, A.K. Study of Rosin and Rosin Derivatives as Coating Materials for Controlled Release of Drug. Journal of Controlled Release 1987, 5, 63–68. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

). Reproduced from ref (Pathak & Dorle, 1987) with perm with permission. Copyright © 1987, Elsevier.

). Reproduced from ref (Pathak & Dorle, 1987) with perm with permission. Copyright © 1987, Elsevier.

). Reproduced from ref (Pathak & Dorle, 1987) with perm with permission. Copyright © 1987, Elsevier.

). Reproduced from ref (Pathak & Dorle, 1987) with perm with permission. Copyright © 1987, Elsevier.