1. Introduction

Endocrine hormones are critical for regulating various physiological processes in the human body by influencing pathways related to metabolism, growth and development, reproduction, and the body’s response to stress.[

1,

2] Previous epidemiological studies have established associations between levels of endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders.[

2] Among these associations, the co-occurrence of thyroid hormones and mental health disorders has been extensively reported, with several clinical observations of hypothyroidism including depression and cognitive impairment and even severe cases of thyroid failure linked to psychosis and schizophrenia;[

2,

3] in contrast, hyperthyroidism has been associated with markedly high occurrence of psychiatric conditions including depression affecting 30-70% of cases and anxiety disorders affecting 60% of cases.[

3] Additionally, levels of sex hormones have been linked with mental health disorders including androgen deficiency which has been associated with depressive symptoms, impaired mental concentration, and memory loss,[

4] and estrogen deprivation which has been associated with depression, sleep disruption, and anxiety.[

5,

6] Despite these well-documented associations, the mechanisms underlying these observed associations between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders has not yet been fully established.

Genetic correlation quantifies the shared genetic basis between two traits by analyzing genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics of common variants in the population. Previous studies have computed the genetic correlations for various complex traits and diseases, identifying shared genetic architectures that may explain co-occurring conditions and associations observed in epidemiological studies. However, thus far, the shared genetic basis between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders has been largely unexplored. To address this gap, we computed genetic correlations 1) among endocrine hormone metrics (including six thyroid hormone metrics and three sex hormone metrics), and 2) between endocrine hormones metrics and ten psychiatric disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining GWAS Summary Statistics for Endocrine Hormones and Psychiatric Disorders

All endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders for which we obtained GWAS summary statistics are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and involved individuals of predominantly European ancestry.[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] These endocrine hormone phenotypes included levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), estradiol, testosterone, and thyroid hormone metrics including levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (FT3), total triiodothyronine (TT3), and free thyroxine (FT4), and ratios of FT3/FT4 and TT3/FT4; GWAS sample sizes for these endocrine hormone metrics ranged from around 15,000 to over 380,000 individuals. Psychiatric disorders that were analyzed in this study included anorexia nervosa, Tourette's syndrome, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, schizophrenia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, Type 1 bipolar disorder, Type 2 bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder; GWAS sample sizes for these psychiatric disorders ranged from around 10,000 to over 800,000 individuals, with disorders such as schizophrenia, ADHD, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder each involving over >200,000 individuals, with other disorders such as Tourette’s syndrome, anorexia nervosa, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms each involving <100,000 individuals. All the endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders included in this study were selected based on prior work indicating the presence of a substantial genetic basis, with many of these traits having previously reported genome-wide significant loci.[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]

2.2. Harmonizing GWAS Summary Statistics

The genomic coordinates of all variants were converted to the GRCh37 human reference build using the liftOver software package.[

17] Baseline and effect alleles for variants were standardized across studies, as well as their effect sizes. For variants with missing minor allele frequencies annotations, we utilized allele frequencies from European individuals in the 1000 genomes project.[

18] After this variant harmonization, we annotated variants with their rsID using the dbSNP database.[

19] In order to maintain high consistency in the imputation quality of variants across all included analyzed phenotypes, we restricted variants to those included in the HapMap3 panel,[

20] which constitutes a set of common variants that tend to be well-imputed across studies.

2.3. Computing Genetic Correlations Between Endocrine Hormone Metrics and Psychiatric Disorders

We first used the LD score regression (LDSC) package[

21] to estimate pairwise genetic correlations between different endocrine hormone metrics, and subsequently, between each hormone metric and each psychiatric disorder. To perform this analysis, we input the harmonized GWAS summary statistics along with linkage disequilibrium reference panels that had been previously generated using HapMap3 variants[

20,

21] from European individuals in the 1000 Genomes Project.[

18] Since the GWAS summary statistics for the included endocrine hormone metrics and psychiatric disorders were developed using outcomes measured on varying scales (i.e. binary vs. continuous vs. transformed outcomes), the following results in the main text report only p-values and the directionality of each genetic correlation, rather than the magnitudes of each genetic correlation.

3. Results

3.1. The Shared Genetic Architecture of Endocrine Hormones

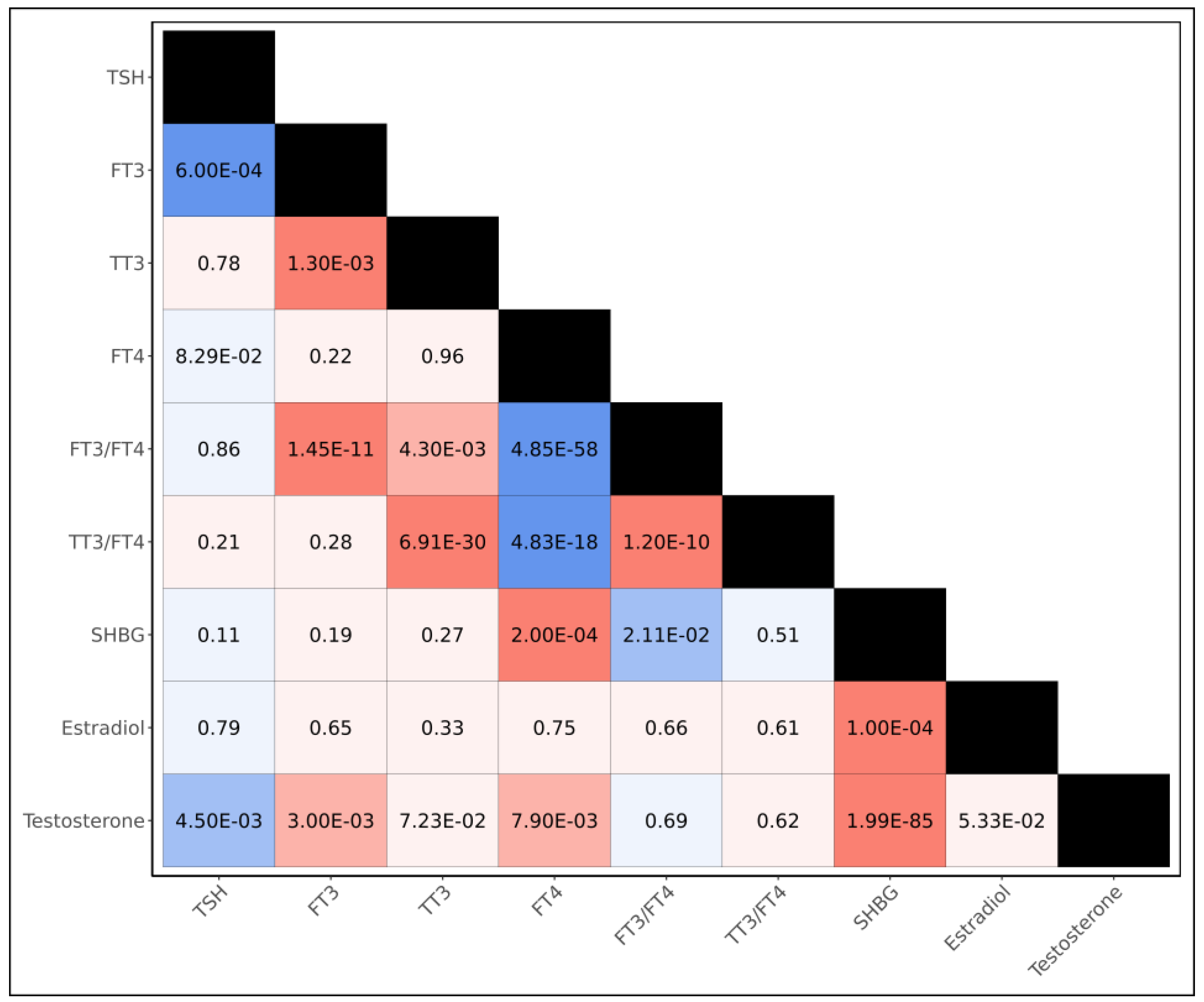

Prior to examining the shared genetic architecture between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders, we first computed genetic correlations between each of the thyroid and sex hormone metrics (

Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2). We observed the genetic bases of thyroid hormone metrics tended to be strongly shared, with all six thyroid hormone metrics yielding statistically significant genetic correlations with at least one other thyroid hormone metric at the Bonferroni threshold of significance (p<1.39x10

-3); in particular, we observed negative genetic correlations between FT4 and both FT3/FT4 (p=4.85x10

-58) and TT3/FT4 (p=4.83x10

-18), and a positive genetic correlation between TSH and FT3 (p=6.00x10

-4). Among sex hormones, we observed positive genetic correlations between SHBG and both estradiol (p= 1.00x10

-4) and testosterone (p=1.99x10

-85) at the Bonferroni-threshold of significance. When examining the genetic overlap between thyroid hormones and sex hormones, we observed positive genetic correlations between testosterone and both FT3 (p=3.00x10

-3) and FT4 (p=7.90x10

-3), as well as a Bonferroni-significant positive genetic correlation between FT4 and SHBG (p=2.00x10

-4); we additionally observed a negative genetic correlation between testosterone and TSH (p=4.50x10

-3).

3.2. Genetic Correlations Between Endocrine Hormones and Psychiatric Disorders

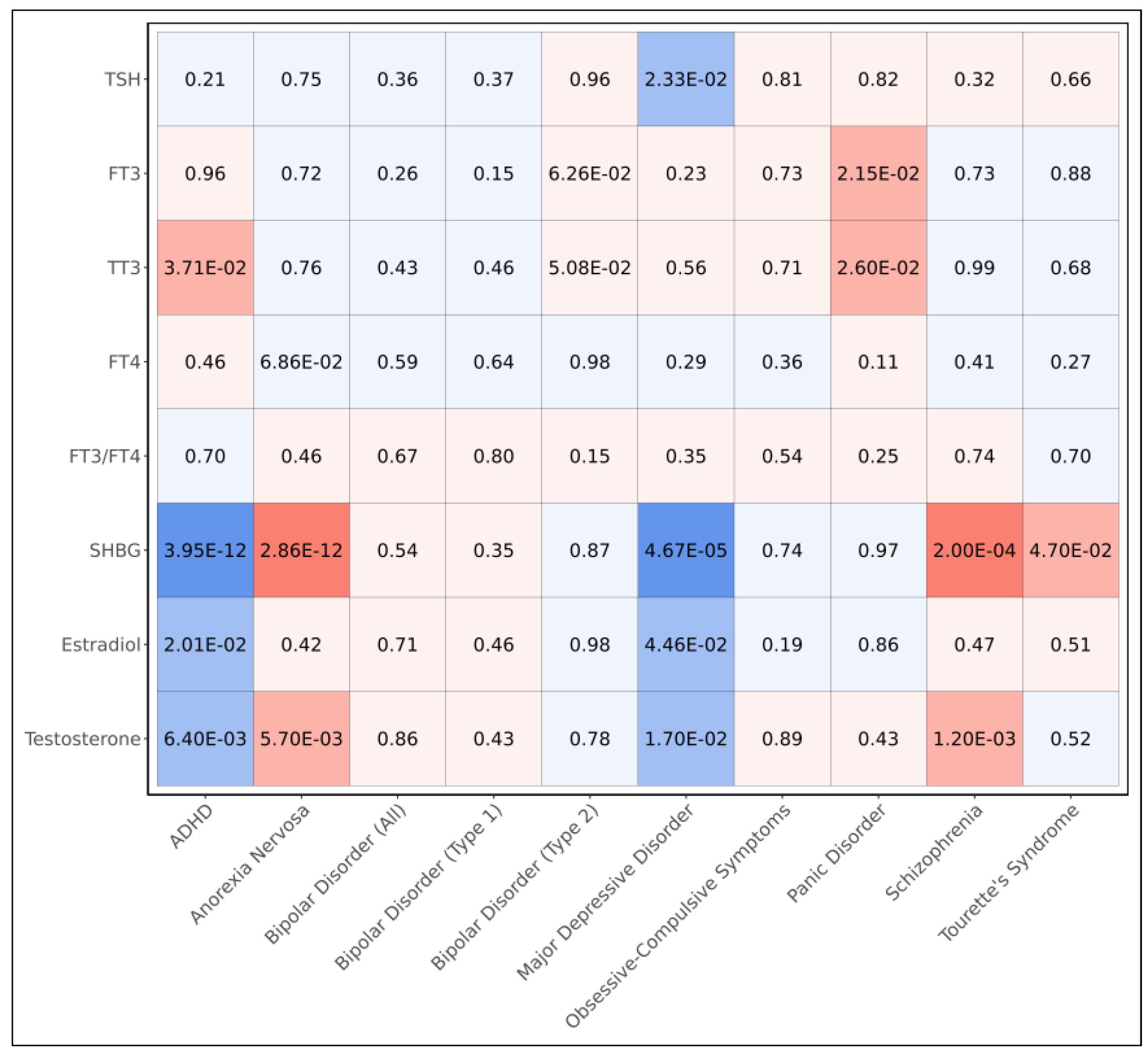

To evaluate the shared genetic bases between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders, we computed pairwise genetic correlations (

Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). We observed sex hormones exhibited many genetic correlations with psychiatric disorders including SHBG, which had negative genetic correlations with ADHD (p=3.95x10

-12) and major depressive disorder (p=4.67x10

-5) and positive genetic correlations with anorexia nervosa (p=2.86x10

-12) and schizophrenia (p=2.00x10

-4), all at the Bonferroni threshold of significance (p<5.56x10

-4) (

Figure 2); we also observed a nominally significant positive genetic correlation between SHBG and Tourette’s syndrome (p=4.70x10

-2). In addition, we observed both testosterone and estradiol were negatively correlated with both ADHD (p=2.01x10

-2 and p=6.40x10

-3, respectively) and major depressive disorder (p=4.46x10

-2 and p=1.70x10

-2, respectively); furthermore, we observed positive correlations between testosterone and both anorexia nervosa (p=5.70x10

-3) and schizophrenia (p=1.20x10

-3).

Though we did not observe any Bonferroni-significant (p<5.56x10

-4) genetic correlations between thyroid hormone metrics and psychiatric disorders, we observed positive correlations between TT3 and both ADHD (p=3.71x10

-2) and panic disorder (p=2.60x10

-2) and between FT3 and panic disorder (p=2.15x10

-2) (

Figure 2). We additionally observed a nominal negative correlation between TSH and major depressive disorder (p=2.33x10

-2).

4. Discussion

In this study, we systematically examined the shared genetic architecture of common variants underlying 1) different endocrine hormones and 2) the shared etiology between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders by computing genetic correlations between endocrine hormone metrics – including thyroid and sex hormones – and ten psychiatric disorders using GWAS summary statistics involving predominantly European-ancestry individuals. While we observed extensive genetic correlations among sex hormones and among thyroid hormones separately, we also identified several genetic correlations between sex and thyroid hormones, suggesting a shared genetic architecture across different endocrine hormones. Furthermore, when examining genetic correlations between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders, we identified significant shared genetic architectures, particularly involving sex hormones; notably, SHBG showed significant genetic correlations with multiple psychiatric conditions even after controlling for multiple testing. While the genetic correlations between thyroid hormones and psychiatric disorders did not remain significant after controlling for multiple testing, several nominal associations were identified, suggesting a potential link in the genetic regulation of thyroid hormone levels and the risk of developing psychiatric disorders.

This study enhances our understanding of the shared genetic basis linking sex hormones and psychiatric disorders by demonstrating that genetic correlations derived from common variants broadly align with prior epidemiological findings. Previous observational and causal inference studies have suggested a potential involvement of SHBG in various psychiatric disorders. Notably, a recent Mendelian Randomization study – which utilizes variants as instruments to mimic random assignment – provided evidence that SHBG is causally associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia[

22]; this finding was supported by our identification of a Bonferroni-significant positive genetic correlation between SHBG levels and schizophrenia. Moreover, clinical observations indicate that males newly diagnosed with a first-episode psychosis exhibit higher SHBG levels than controls, further supporting the positive genetic correlation identified in our study.[

23] Additionally, observational studies have demonstrated SHBG was negatively correlated with symptoms of ADHD in boys[

24] and positively associated with anorexia nervosa amongst kwashiorkor patients,[

25] which was corroborated by negative and positive Bonferroni-significant genetic correlations in our study, respectively. Furthermore, another Mendelian Randomization study demonstrated SHBG had a negative causal association with major depression in males,[

26] which was supported by our observation of a negative genetic correlation between the two. Interestingly, for each Bonferroni-significant genetic correlation we observed between SHBG and the evaluated psychiatric disorders, either testosterone, estradiol, or both also showed nominally significant genetic correlations in the same direction. This pattern highlights the shared genetic architecture among SHBG, testosterone, and estradiol that we observed when computing genetic correlations between different sex hormones, further emphasizing the relevance of common variants that influence all three of these sex hormones in psychiatric disorders.

The genetic correlations we computed between thyroid hormone metrics and psychiatric disorders partially align with findings in previous epidemiological studies. We identified a nominal negative genetic correlation between TSH and major depressive disorder, which corroborates a large population-based cross-sectional study based in the United States that reported low levels of TSH was associated with a higher odds of clinically relevant depression.[

27] In contrast, some of our other observations differed from prior studies; for instance, while it has been reported that a reduction in FT3 levels has been implicated in panic disorders[

28,

29], we identified a positive genetic correlation between FT3 levels and panic disorder. Additionally, while previous Mendelian Randomization studies have indicated FT4 has a protective effect on bipolar disorders,[

30,

31,

32] including Type 1 bipolar disorder,[

30] our study did not identify any nominally significant genetic correlations between FT4 and any subtypes of bipolar disorder. These inconsistencies may partially be attributed to the much lower sample sizes utilized in the GWAS studies for thyroid hormone metrics; this decreased statistical power may potentially result in less reliable genetic correlation estimates. Furthermore, the effects of additional sociodemographic, environmental, and genetic factors beyond common variants in the genome may be insufficiently captured in genetic correlation analyses.[

33]

Despite identifying multiple genetic correlations that support a shared genetic architecture between endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders, this study had several limitations. First, for several psychiatric disorders including anorexia nervosa, Tourette’s syndrome, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and panic disorder, the sample sizes of GWAS studies we utilized were comparatively low, which may partially explain the general lack of strong genetic correlations of these disorders with endocrine hormones, apart from with SHBG, which derived summary statistics from a well-powered GWAS. Increasing sample sizes involved in future GWAS studies for these hormone metrics and psychiatric disorders, as well as inclusion of participants from diverse populations will be needed to validate the associations identified in this study. Additionally, genetic correlations in this study were restricted to HapMap3 variants, as these are commonly well-imputed across studies and are recommended by the LDSC package for calculating genetic correlations; however, this approach may limit our ability to identify shared genetic architectures located in genomic regions not represented in the HapMap3 panel.

In conclusion, our study reveals genetic correlations between levels of endocrine hormones, particular sex hormones such as SHBG, and multiple psychiatric disorders, thereby highlighting shared genetic architecture driven by common variants. These genetic correlations are generally consistent with prior observational and causal inference studies, thus supporting the biological relevance of sex hormones in the etiology of psychiatric disorders. Although genetic correlations involving thyroid hormones were attenuated after correcting for multiple testing, several nominally significant correlations warrant further investigation. Increasing sample sizes for GWAS studies of endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders, diversity of participants utilized in these studies, as well as genome coverage to include variants outside of those in the HapMap3 set will help validate the correlations we identified and further improve our understanding of the genetic co-regulation of endocrine hormones and psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of genome-wide association studies included in this study. Supplementary Table 2. Genetic correlations among different endocrine hormone metrics. Supplementary Table 3. Genetic correlations between endocrine hormone metrics and psychiatric disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.L.; methodology, J.L.L.; formal analysis, J.L.L.; investigation, J.L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.L.; visualization, J.L.L.; funding acquisition, J.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, grant number T32GM007281, and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, grant numbers TREND21675016 and SAC210203.

Informed Consent Statement

All GWAS studies from which summary statistics used in this study had been generated had previously obtained informed consent from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the support staff of Randi, a high-performance computing cluster maintained by the University of Chicago’s Center for Research Informatics. The author would like to thank the Cancer Health Equity Training Program and the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of Chicago for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GWAS |

Genome-wide association study |

| ADHD |

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| SHBG |

Sex hormone-binding globulin |

| TSH |

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

| FT3 |

Free Triiodothyronine |

| TT3 |

Total Triiodothyronine |

| FT4 |

Free Thyroxine |

References

- Hiller-Sturmhöfel S, Bartke A. The Endocrine System. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(3):153–64.

- Salvador J, Gutierrez G, Llavero M, Gargallo J, Escalada J, López J. Endocrine Disorders and Psychiatric Manifestations. In: Portincasa P, Frühbeck G, Nathoe HM, editors. Endocrinology and Systemic Diseases [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 9]. p. 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Feldman AZ, Shrestha RT, Hennessey JV. Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of Thyroid Disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013 Sep 1;42(3):453–76. [CrossRef]

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;95(6):2536–59.

- Mauas V, Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC. Depressive symptoms in the transition to menopause: the roles of irritability, personality vulnerability, and self-regulation. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014 Aug 1;17(4):279–89. [CrossRef]

- Studd J. Hormone therapy for reproductive depression in women. Post Reprod Health. 2014 Dec 1;20(4):132–7. [CrossRef]

- Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. [CrossRef]

- Sterenborg RBTM, Steinbrenner I, Li Y, Bujnis MN, Naito T, Marouli E, et al. Multi-trait analysis characterizes the genetics of thyroid function and identifies causal associations with clinical implications. Nat Commun. 2024 Jan 30;15(1):888.

- Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, Hübel C, Coleman JRI, Gaspar HA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat Genet. 2019 Aug;51(8):1207–14. [CrossRef]

- Yu D, Sul JH, Tsetsos F, Nawaz MS, Huang AY, Zelaya I, et al. Interrogating the Genetic Determinants of Tourette’s Syndrome and Other Tic Disorders Through Genome-Wide Association Studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 1;176(3):217–27. [CrossRef]

- Strom NI, Burton CL, Iyegbe C, Silzer T, Antonyan L, Pool R, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms including 33,943 individuals from the general population. Mol Psychiatry. 2024 Sep;29(9):2714–23. [CrossRef]

- Trubetskoy V, Pardiñas AF, Qi T, Panagiotaropoulou G, Awasthi S, Bigdeli TB, et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature. 2022 Apr;604(7906):502–8. [CrossRef]

- Demontis D, Walters GB, Athanasiadis G, Walters R, Therrien K, Nielsen TT, et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat Genet. 2023 Feb;55(2):198–208.

- Mullins N, Forstner AJ, O’Connell KS, Coombes B, Coleman JRI, Qiao Z, et al. Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nat Genet. 2021 Jun;53(6):817–29. [CrossRef]

- Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Mar;22(3):343–52. [CrossRef]

- Forstner AJ, Awasthi S, Wolf C, Maron E, Erhardt A, Czamara D, et al. Genome-wide association study of panic disorder reveals genetic overlap with neuroticism and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Aug;26(8):4179–90. [CrossRef]

- Perez G, Barber GP, Benet-Pages A, Casper J, Clawson H, Diekhans M, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025 Jan 6;53(D1):D1243–9.

- Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Oct;526(7571):68–74. [CrossRef]

- Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001 Jan 1;29(1):308–11. [CrossRef]

- Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010 Sep;467(7311):52–8.

- Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015 Mar;47(3):291–5. [CrossRef]

- Ou M, Du Z, Jiang Y, Zhou Q, Yuan J, Tian L, et al. Causal relationship between schizophrenia and sex hormone binding globulin: A Mendelian randomization study. Schizophr Res. 2024 May 1;267:528–33. [CrossRef]

- Petrikis P, Tigas S, Tzallas AT, Karampas A, Papadopoulos I, Skapinakis P. Sex hormone levels in drug-naïve, first-episode patients with psychosis. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020 Mar;24(1):20–4.

- Wang LJ, Lee SY, Chou MC, Lee MJ, Chou WJ. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, free testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin on susceptibility to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 May 1;103:212–8. [CrossRef]

- Pascal N, Amouzou EKS, Sanni A, Namour F, Abdelmouttaleb I, Vidailhet M, et al. Serum concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin are elevated in kwashiorkor and anorexia nervosa but not in marasmus1,2,3. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Jul 1;76(1):239–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Sun Y, Guo S, Zhou Q, Jiang Y, Shen Y, et al. Causal relationship between sex hormone-binding globulin and major depression: A Mendelian randomization study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2023 Nov;148(5):426–36. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, LeMahieu AM, Stan MN, Seshadri A, Ozerdem A, Pazdernik V, et al. The Association Between Thyroid Stimulating Hormone And Depression: A Historical Cohort Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023 Jul;98(7):1009–20.

- Kirkegaard C, Faber J. The role of thyroid hormones in depression. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998 Jan 1;138(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mason GA, Walker CH, Prange AJ. L-Triiodothyronine: Is this Peripheral Hormone a Central Neurotransmitter? Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993 May;8(3):253–8.

- Li JL. The Causal Role of Thyroid Hormones in Bipolar Disorders: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2024;7(6):e70009. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Lv H, Zhang X, Gao Y, Liu X, Gu C, et al. Assessment of the relationships between genetic determinants of thyroid functions and bipolar disorder: A mendelian randomization study. J Affect Disord. 2022 Feb 1;298(Pt A):373–80. [CrossRef]

- Gan Z, Wu X, Chen Z, Liao Y, Wu Y, He Z, et al. Rapid cycling bipolar disorder is associated with antithyroid antibodies, instead of thyroid dysfunction. BMC Psychiatry. 2019 Dec 2;19(1):378. [CrossRef]

- Rowland TA, Marwaha S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018 Apr 26;8(9):251–69. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).