Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

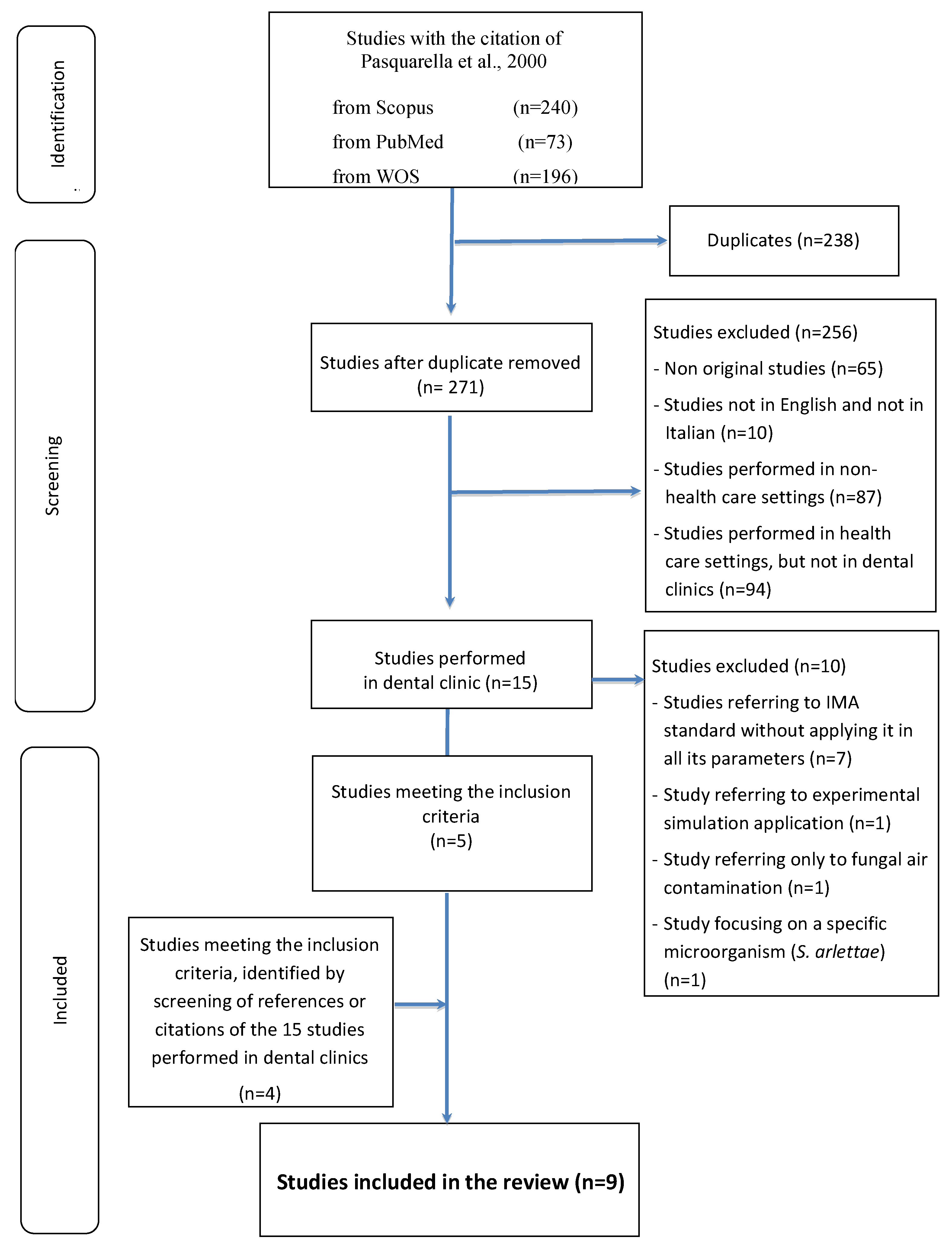

2. Materials and Methods

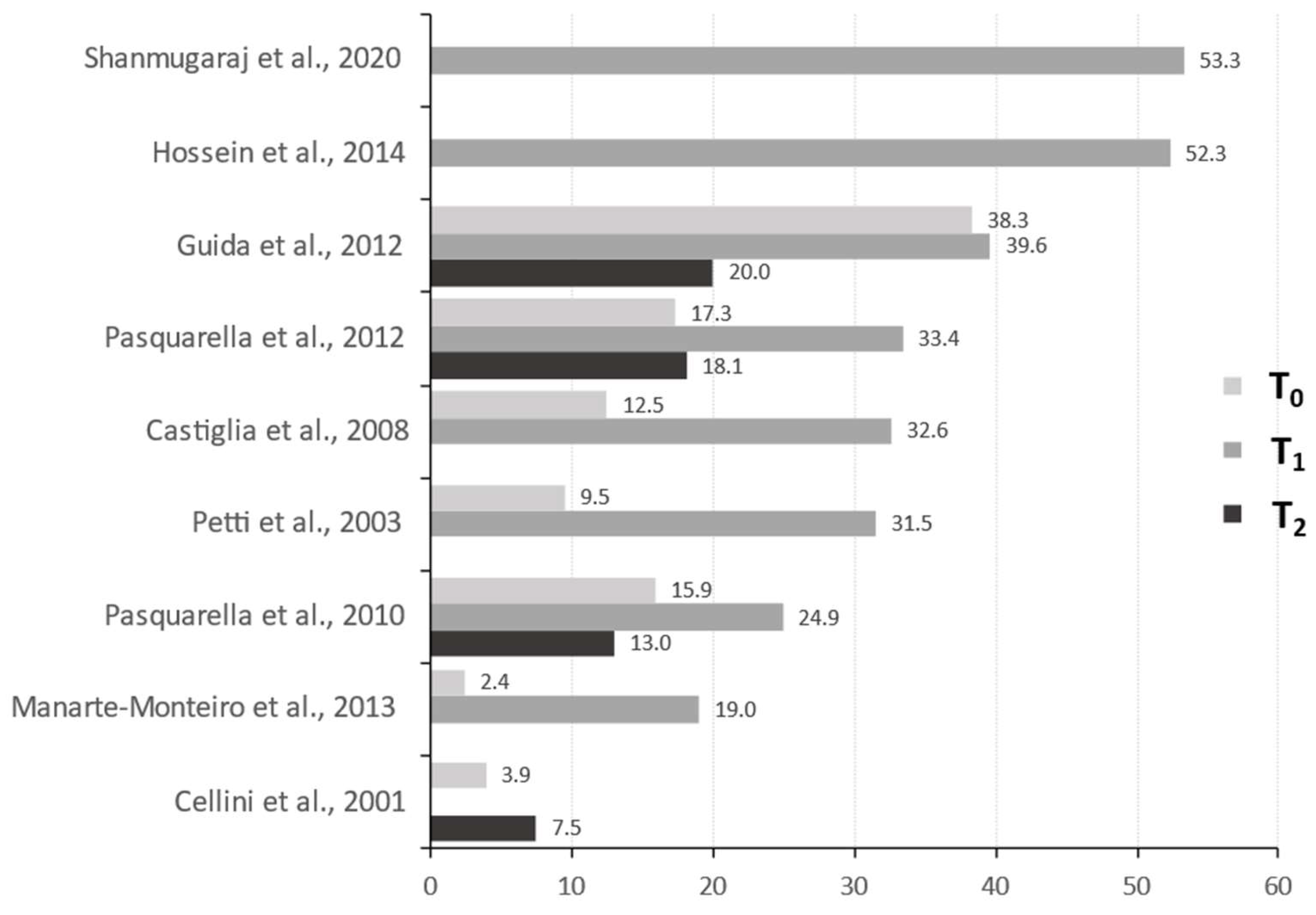

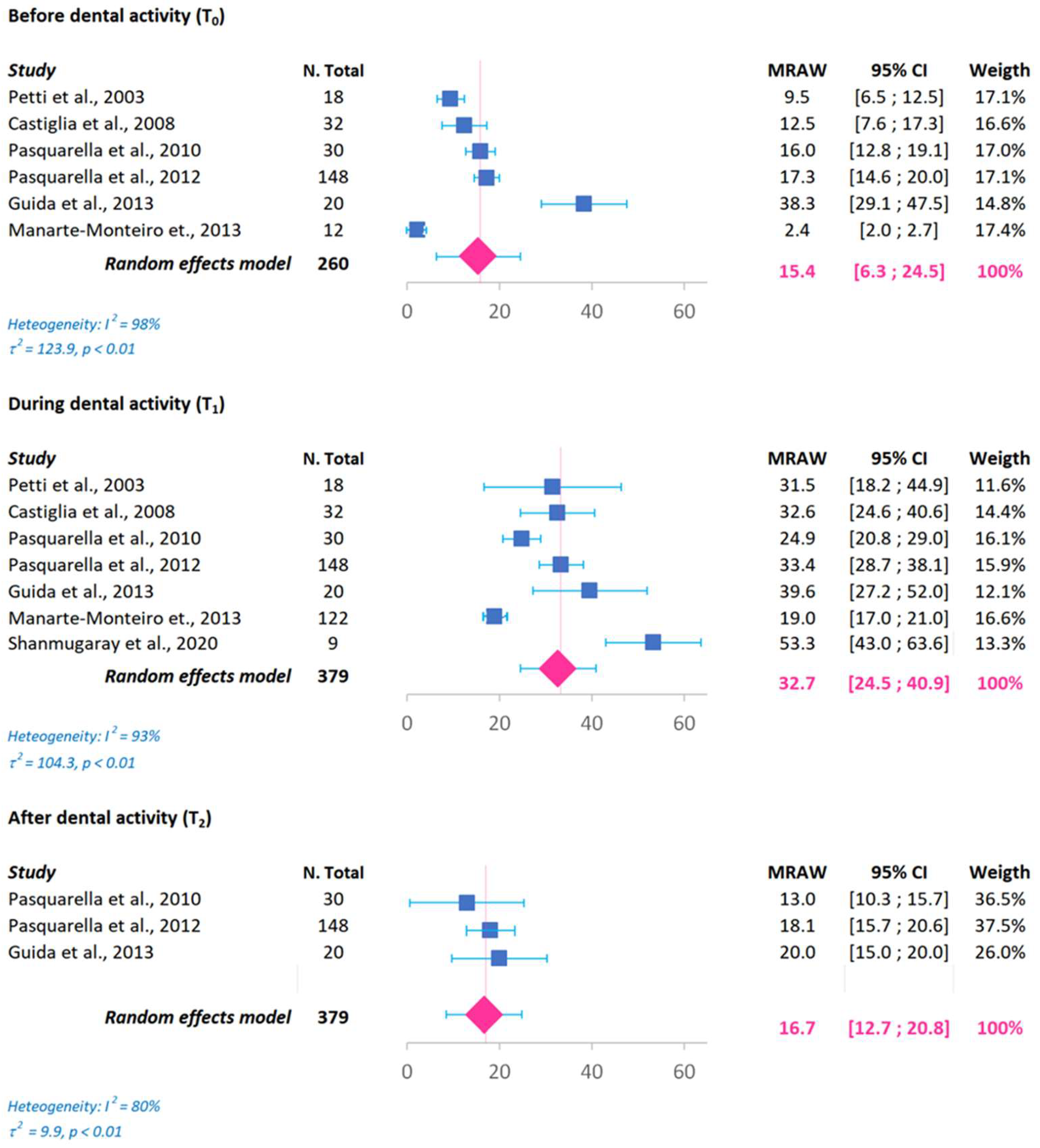

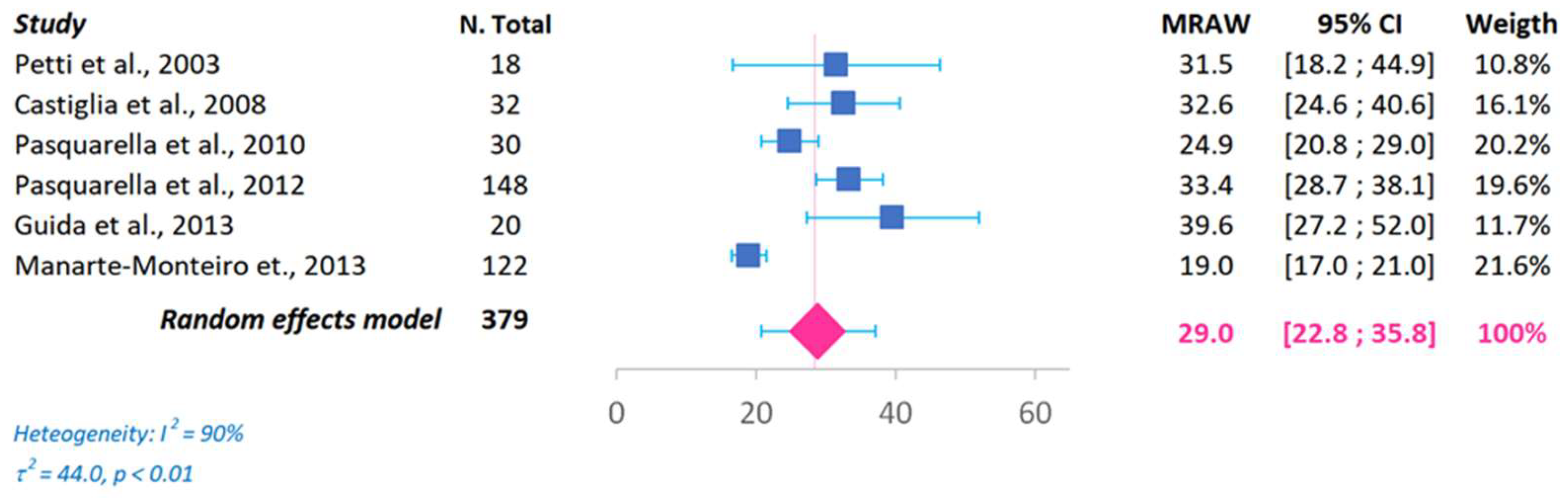

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings - 2003. MMWR 2003; 52(No RR-17):1-66. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5217.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2024.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectation for Safe Care. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; October 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dental-infection-control/media/pdfs/2024/07/safe-care2.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care2.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2024.

- Cole, E.C.; Cook, C.E. Characterization of infectious aerosols in healthcare facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies. Am J Infect Control 1998, 26, 453-464. [CrossRef]

- Kumbargere Nagraj, S.; Eachempati, P.; Paisi, M.; Nasser M.; Sivaramakrishnan, G.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to reduce contaminated aerosols produced during dental procedures for preventing infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Oct 12 2020, 10(10), 1-122CD013686.

- Kumbargere Nagraj, S.; Eachempati, P.; Paisi, M.; Nasser, M.; Sivaramakrishnan, G.; Francis, T.; Verbeek, J.H. Preprocedural mouth rinses for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, 8, 1-122. [CrossRef]

- Laheij, A.M.; Kistler, J.O.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Välimaa H.; de Soet J.J. European Oral Microbiology Workshop (EOMW). Healthcare-associated viral and bacterial infections in dentistry. J Oral Microbiol 2012, 4. [CrossRef]

- Van der Weijden, F. Aerosol in the oral health-care setting: a misty topic. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 23-32.

- Zemouri C.; de Soet, H.; Crielaard, W.; Laheij, A. A scoping review on bioaerosols in healthcare and the dental environment. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178007. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Environmental infection Control in Health-Care Facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). 2003. Update: July 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/media/pdfs/Guideline-Environmental-H.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2024.

- Pankhurst, C.L.; Coulter, W.A. Do contaminated dental unit waterlines pose a risk of infection? J Dentistry 2007, 35, 712-720.

- Pasquarella, C.; Veronesi, L.; Napoli, C.; Castiglia, P.; Liguori, G.; Rizzetto, R.; Montagna, M.T.; Rizzetto, R.; Torre, I.; Righi, E.; Farruggia, P.; Tesauro, M.; Torregrossa, M.V.; Montagna M.T.; Colucci, M.E. et al. Microbial environment contamination in Italian dental clinics: A multicenter study yielding recommendations for standardized sampling methods and threshold values. Sci Total Environ 2012, 420, 289-299. [CrossRef]

- Rautemaa, R.; Nordberg, A.; Wuolijoki-Saaristo, K.; Meurman, J.H. Bacterial aerosols in a dental practice - a potential hospital infection problem? 2006, 64, 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, J. Dental bioaerosols as an occupational hazard in a dentist’s workplace. Ann Agric Environ Med 2007, 14, 203-207.

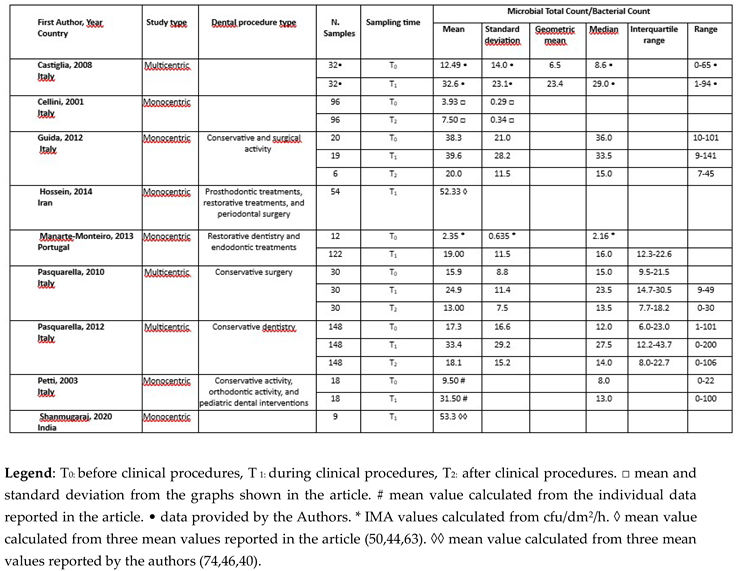

- Castiglia, P.; Liguori, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Napoli, C.; Pasquarella, C.; Bergomi, M.; Fabiani, L.; Monarca, S.; Petti, S. Italian multicenter study on infection hazards during dental practice: control of environmental microbial contamination in public dental surgeries. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 187-193. [CrossRef]

- Harrel, S.K.; Molinari, J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc 2004, 135(4), 429-437.

- King, T.B.; Muzzin, K.B.; Berry, C.V.; Anders, L.M. The effectiveness of an aerosol reduction device for ultrasonic scalers. J Periodontol 1997, 68, 45-49. [CrossRef]

- Puljich, A.; Jiao, K.; Lee, R.S.; Walsh, L.J.; Ivanovski, S.; Han, P. Simulated and clinical aerosol spread in common periodontal aerosol-generating procedures. Clin Oral Investig 2022, 26, 5751-5762. [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, M.F.; Menso, L.; Steinfort, J.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; van der Weijden, G.A. Atmospheric contamination during ultrasonic scaling. J Clin Periodontol 2004, 31, 458-462. [CrossRef]

- Kadailcifer, D.G.; Cotuk, A. Microbial contamination of dental unit waterlines and effect on quality of indoor air. Environ Monit Assess 2014, 186, 3431-3444.

- Szymanska, J. Biofilm and dental unit waterlines. Ann Agric Environ Med 2003, 10(2), 151-7.

- Szymańska, J.; Sitkowska, J. Bacterial contamination of dental unit waterlines. Environ Monit Assess 2013 May, 185(5), 3603-11. [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, J.; Basu, M.K.; Browne, R.M.; Burge, P.S.; Matthews, J.B. Survey of the use of personal protective equipment and prevalence of work-related symptoms among dental staff. Occup Environ Med 1997, 54, 125-134. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, M.W.; Andreana, S. Risk and prevention of transmission of infectious diseases in dentistry. Quintessence Int 2002, 33, 376-382.

- Polednik, B. Exposure of staff to aerosols and bioaerosols in a dental office. Building and Environment 2021, 187, 107388. [CrossRef]

- Bahador, M.; Alfirdous, R.A.; Alguria, T.A.; Griffin, I.; Tordik, P.A.; Martinho, F.C. Aerosols generated during endodontic treatment: a special concern during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. J Endod 2019, 47, 732-739. [CrossRef]

- Manea, A.; Crisan, D.; Baciut, G.; Baciut, M.; Bran, S.; Armencea, G.; Crisan, M.; Colosi, H.; Colosi, I.; Vodnar, D.; Aghorghiesei, A.; Aghorghiesei, O. The importance of atmospheric microbial contamination control in dental offices: Raised awareness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Appl Sci 2021, 11, 2359. [CrossRef]

- Ralli, M.; Candelori, F.; Cambria, F.; Greco, A.; Angeletti, D.; Lambiase, A.; Campo, F.; Minni, A.; Polimeni, A.; De Vincentiis, M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on otolaryngology, ophthalmology and dental clinical activity and future perspectives. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 9705-9971. [CrossRef]

- Suprono, M.S.; Savignano, R.; Won, J.B.; Lillard, S.; Zhong, Z.; Ahmed, A.; Roque-Torres, G.; Zhang, W.; Oyoyo, U.B.; Richardson, P.; Caruso, J.; Handysides, R.; Li, Y. Evaluation of microbial air quality and aerosol distribution in a large dental clinic. Am J Dent 2022, 35(5), 268-272.

- Wood D.; Da Silva K. A review of infection prevention and control guidelines for dental offices during the COVID-19 pandemic in mid-2020. Canadian Journal of Infection Control 2021, 36(3), 129-137.

- Li, Y.; Leung, G.M.; Tang, J.W.; Yang, X.; Chao, C.H.; Lin, J.Z.; Lu, J.W.; Nielsen, P.V.; Niu, J.; Qian, H.; Sleigh, A.C.; Su, H.J.; Sundell, J.; Wong, T.W.; Yuen, P.L. Role of ventilation in airborne transmission of infectious agents in the built environment - a multidisciplinary systematic review. Indoor Air 2007, 17, 2-18. [CrossRef]

- EN 17141:2020. Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments - Biocontamination control.

- ISO 14698-1:2003. Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments biocontamination control. Part 1: general principles and methods.

- Pasquarella, C.; Albertini, R.; Dall’Aglio, P.; Saccani, E.; Sansebastiano, G.E.; Signorelli, C. Air microbial sampling: The state of the art. Ig San Pubbl 2008, 64, 79–120.

- Pitzurra, M.; Savino, A.; Pasquarella, C. Microbiological environment monitoring (MEM). Ann Ig 1997, 9, 439–454.

- Whyte W.; Thomas A.M. Auditing the microbiological quality of the air in operating theatres. Bone Joint J 2024, 106-B(9), 887-891. [CrossRef]

- Viani, I.; Colucci, M.E.; Pergreffi, M.; Rossi, D.; Veronesi, L.; Bizzarro, A.; Capobianco, E.; Affanni, P.; Zoni, R.; Saccani, E.; Albertini, R.; Pasquarella C. Passive air sampling: the use of the index of microbial air contamination. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, 92-105. [CrossRef]

- Dybwad, M.; Skogan, G.; Blatny, J.M. Comparative Testing and Evaluation of Nine Different Air Samplers: End-to-End Sampling Efficiencies as Specific Performance Measurements for Bioaerosol Applications. Aerosol Science and Technology 2014, 48, 282-295.

- Whyte, W.; Green, G.; Albisu, A. Collection efficiency and design of microbial air samplers. Journal of Aerosol Science 2007, 38 (1), 97-110. ISSN 0021-8502. [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Pitzurra, O.; Savino, A. The index of microbial air contamination. J Hosp Infect 2000, 46, 241–256. [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team, 2024. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/.

- Aquino de Muro, M.; Shuryak, I.; Uhlemann, A-C.; Tillman, A.; Seeram, D.; Zakaria, J.; Welch, D.; Erde, S.M.; Brenner, D.J. The abundance of the potential pathogen Staphylococcus hominis in the air microbiome in a dental clinic and its susceptibility to far-UVC light. MicrobiologyOpen 2023, 12, e1348. [CrossRef]

- Decraene V.; Ready, D.; Pratten, J.; Wilson, M. Air-borne microbial contamination of surfaces in a UK dental clinic. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2008, 54, 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Kherdekar, R.S.; Dixit, A.; Kothari, A.; Pandey K.P.; Advani, H.; Gaurav, A.; Omar, B.J. Unusually isolated Staphylococcus arlettae in intra-oral sutures - Case series. Access Microbiol 2023, 5, 000555.v4. [CrossRef]

- Manarte-Monteiro, P.; Carvalho, A.; Pina, C.; Olivira, H.; Conceicao Manso, M. Air quality assessment during dental practice: Aerosols bacterial counts in an universitary clinic. Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxillofac 2013, 54, 2-7. [CrossRef]

- Montalli, V.A.M.; Garcez, A.S.; de Oliveira, L.V.C.; Sperandio, M.; Napimoga, M.H.; Motta, R.H.L. A novel dental biosafety device to control the spread of potentially contaminated dispersion particles from dental ultrasonic tips. PLoS One 2021, 6(2), e0247029. [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Veronesi, L.; Castiglia, P.; Liguori, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Napoli, C.; Rizzetto, R.; Torre, I.; Masia, M.D.; Di Onofrio, V.; Colucci, M.E.; Tinteri, C.; Tanzi, M. Italian multicentre study on microbial environmental contamination in dental clinics: a pilot study. Sci Total Environ 2010, 408, 4045-4051. [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Vitali, P.; Saccani, E.; Manotti, P.; Boccuni, C.; Ugolotti, M.; Signorelli, C.; Mariotti, F.; Sansebastiano, G.E.; Albertini, R. Microbial air monitoring in operating theatres: experience at the University Hospital of Parma. J Hosp Infect 2012, 81(1), 50-7. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaraj, G.B.; Rao, A. A study to assess the microbial profile and index of microbial air contamination in dental operatories. Indian J Dent Res 2020, 31, 465-469. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.D.; De Carvalho, M.A.; De Resende, M.A.; De Menezes Cussiol, N.A.; Alvarez-Leite, M.E.; Dos Santos, S.G.; de Oliveira, M.B.; De Magalhães, T.F.; Silva, M.X.; Nicoli, J.R.; de Macêdo Farias, L. Isolation of clinically relevant fungal species from solid waste and environment of dental health services. Lett Appl Microbiol 2010, 51, 370-376. [CrossRef]

- Zemouri, C.; Volgenant, C.M.C.; Buijs, M.J.; Crielaard, W.; Rosema, N.A.M.; Brandt, B.W.; Laheij, A.M.G.A.; De Soet, J.J. Dental aerosols: microbial composition and spatial distribution. J Oral Microbiol 2020, 12, 1762040. [CrossRef]

- Cellini, L.; Di Campli, E.; Di Candia, M.; Chiavaroli, G. Quantitative microbial monitoring in a dental office. Public Health 2001, 115, 301-305. [CrossRef]

- Guida M.; Gallé, F.; Di Onofrio, V.; Nastro, R.A.; Battista, M.; Liguori, R.; Battista, F.; Liguori, G. Environmental microbial contamination in dental setting: a local experience. J Prev Med Hyg 2012, 53, 207-212.

- Hossein, M.; Hossein, K.; Mojtaba, S.; Davood, E. Relation of bacteriological water and air quality in dentistry center. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2014, 8, 681-692.

- Petti, S.; Iannazzo, S.; Tarsitani, G. Comparison between different methods to monitor the microbial level of indoor air contamination in the dental office. Ann Ig 2003, 15, 725-733.

- Tellier, R.; Li, Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Tang, J.W. Recognition of aerosol transmission of infectious agents: a commentary. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19, 101. [CrossRef]

- Kedjarune, U.; Kukiattrakoon, B.; Yapong, B.; Chowanadisai, S.; Leggat, P. Bacterial aerosols in the dental clinic: effects of time, position and type of treatment. Int Dent J 2000, 50, 103-107.

- Agodi, A.; Auxilia, F.; Barchitta, M.; Cristina, M.L.; D’Alessandro, D.; Mura, I.; Nobile, M.; Pasquarella, C. Italian Study Group of Hospital Hygiene. Operating theatre ventilation systems and microbial air contamination in total joint replacement surgery: results of the GISIO-ISChIA study. J Hosp Infect 2015, 90, 213-219. [CrossRef]

- Cristina, M.L.; Spagnolo, A.M.; Ottria, G.; Schinca, E.; Dupont, C.; Carbone, A.; Oliva, M.; Sartini, M. Microbial Air Monitoring in Turbulent Airflow Operating Theatres: Is It Possible to Calculate and Hypothesize New Benchmarks for Microbial Air Load? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021 Oct 2, 18(19), 10379. PMID: 34639680; PMCID: PMC8507732. [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, L.; Colucci, M.E.; Napoli, C.; Castiglia, P.; Liguori, G.; Torre, I.; Righi, E.; Farruggia, P.; Tesauro, M.; Montagna, M.T.; Gallè, F.; Masia, M.D.; Di Onofrio, V.; Caggiano, G.; Tinteri, C.; Panico, M.; Pennino, F.; Cannova, L.; Pasquarella, C. Air microbial contamination in dental clinics: comparison between active and passive methods. Acta Biomed 2020 Apr 10, 91(3-S), 165-167. PMID: 32275284; PMCID: PMC7975899. [CrossRef]

- Perdelli, F.; Sartini, M.; Orlando, M.; Secchi, V.; Cristina, M.l. Relationship between settling microbial load and suspended microbial load in operating rooms. Ann Ig 2000, 12, 373-380.

- European Commission. EU Guidelines to Good Manufacturing Practice Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use Revision to Annex 1. Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products. Brussels, 2022. 22 August. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-08/20220825_gmp-an1_en_0.pdf Accessed August 8, 2024.

- Napoli, C.; Marcotrigiano, V.; Montagna, M.T. Air sampling procedures to evaluate microbial contamination: a comparison between active and passive methods in operating theatres. BMC Public Health 2012, 2, 12, 594. [CrossRef]

- Orpianesi, C.; Cresci, A.; La Rosa, F.; Saltalamacchia, G.; Tarsi, R. Evaluation of microbial contamination in a hospital environment. Comparison between the Surface Air System and the traditional method. Nuovi Ann Ig Microbiol 1983, 34, 171-185.

- Pitzurra, M.; Morlunghi, P. Contaminazione microbica dell’aria atmosferica: correlazione fra due diverse metodiche di rilevazione. Ig Mod 1978, 71, 490-502.

- Verhoeff, A.P.; van Wijnen, J.H.; Bolej, J.S.; Brunekreef, B.; van Reenen-Hoekstra, E.S.; Samson, R.A. Enumeration and identification of airborne viable mould propagules in houses. A field comparison of selected techniques. Allergy 1990, 45, 275-284. [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W. Sterility assurance and models for assessing airborne bacterial contamination. Parenter Sci Technol 1986, o40, 188–97.

- Chawla, H.; Anand, P.; Garg, K.; Bhagat, N.; Varmani, S.G.; Bansal, T.; McBain, A.J.; Marwah, R.G. A comprehensive review of microbial contamination in the indoor environment: sources, sampling, health risks, and mitigation strategies. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1285393. [CrossRef]

- Najotra, D.K.; Malhotra, A.S.; Slathia, P.; Raina, S.; Dhar, A. Microbiological Surveillance of Operation Theatres: Five Year Retrospective Analysis from a Tertiary Care Hospital in North India. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2017, 7(3), 165-168. [CrossRef]

- Oulkheir, A.; Safouan, H.; El Housse, F.; Aghrouch, M.; Ounine, K.; Douira, A.; Chadli, S. Assessment of microbiological indoor air quality in a public hospital in the city of Agadir, Morocco. Periodicum Biologorum 2021, 123(1-2), 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Poletti, L.; Pasquarella, C.; Pitzurra, M.; Savino, A. Comparative efficiency of nitrocellulose membranes versus RODAC plates in microbial sampling on surfaces. J Hosp Infect 1999, 41(3), 195-201. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).