1. Introduction

With the increasing greenhouse gas emissions and the warming of the climate of the planet there is a growing interest in renewable energy technologies harvesting energy from the sun in various forms including, light, heat, waves and wind. Over 60% of urban surfaces are occupied by pavements and roofs that are generally covered by grey infrastructures (engineering structures or measures constructed by concrete or metals) (Akbari and Levinson, 2008). In cities, infrastructure absorbs and re-emits the Sun’s heat, resulting in a warmer-than-average environment that can easily reach 4–5 °C and may exceed 7–8 °C in many cases (Nichol and Wong, 2005; Santamouris et al., 2017, 2001). This phenomenon is referred to as the urban heat island effect. Also, to maintain the temperature inside buildings, vast amount of energy is consumed in the cooling systems (Santamouris et al., 2001). This variation of the temperature within inside and outside of buildings results a thermal gradient in building materials used in facades and thermal energy is lost as a result of convection (Reilly and Kinnane, 2017).

Thermoelectric (TE) effect describes the generation of energy that occurs when there is a thermal gradient. There are thermoelectric modules in the market utilising TE effect and developing heat from electricity and electricity by heat. These modules are commonly made of Bismuth Telluride (Bi₂Te₃) and Titanium Zirconate (TiZrO₃) which are toxic and expensive to use in large scale (Goldsmid, 2014). Also, current TE modules available on the market are targeted at smaller applications, like those of computers, or high temperature devices such as automotive or industrial cooling systems. Due to their high costs and low material stability and durability, they are unsuitable for large-scale use in buildings (Wang et al., 2021). Additionally, even if the modules were embedded into buildings, their inclusion weakens the overall structural integrity of the concrete (Wang et al., 2021).

Although cement-based materials have inherently poor electrical conductivity and TE properties, research into cement composites with conductive fillers began in the late 1990s, with (M. Sun et al., 1998) discovering that the addition of carbon fibre increases thermoelectric potential of cement. This led to further studies into TE properties of cement with carbon fibre and steel fibre fillers, which even led to the development of cement-based thermocouples (Wen and Chung, 2001, 2000, 1999). However, focus of research was mainly concentrated on using concrete itself as a sensor with thermoelectric properties playing an important role for engineering applications such as, non-destructive health monitoring and temperature sensing. With the abundance of concrete in urban settings and building surface temperatures reaching up to 65°C (Senevirathne et al., 2021) compared to inside temperatures that must be kept at 24-25°C, it is an ideal candidate for TE energy harvesting.

Green energy transition has sparked a new surge in studies on TE cement-based composite materials. Recently, researchers are increasingly using conductive carbon-based materials and transition metal oxides-based nanomaterials to enhance the TE properties of cement. The addition of fine particles, up to 125 microns in size, can improve mechanical properties of concrete by various mechanisms. These includes compactness by filling intergranular voids between cement particles, enhance hydration by acting as nucleation sites (becoming an integrated part of the cement paste) and react with a cement component, like calcium hydroxide, forming cement gel (Moosberg-Bustnes et al., 2004). In contrast, ionic, electronic and hole conduction all has an effect on TE properties of concrete (Mingqing Sun et al., 1998; Y. Wei et al., 2023).

The percolation phenomenon occurs when a high concentration of conductive substance in a composite creates a network of fibres, allowing conduction to occur through this network, rather than the cement itself (M. Sun et al., 1998). If the functional filler does not reach the percolation threshold required, conduction then occurs through the pores of the cement matrix rather than a conductive network of fibres (Y. Wei et al., 2023). Though addition of these fillers to increase the TE properties of cement paste have studied extensively, very little research has investigated the mechanical properties in parallel. Given the abundance of investigation into the feasibility of TE energy generation in cement-based materials, this paper focuses on exploring the practicality of cement composites in a structural setting. This will be achieved by experimentally testing cement composites with varying graphene oxide (GO) and manganese dioxide (MnO2) additive concentrations.

Graphene is a wonder material first isolated in 2004 and available in different forms such as graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) and Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO). It was found that adding GNP to cement composites at different concentrations improved electrical conductivity, reaching a maximum of 1620 S/m for the 20 wt.% composite. The Seebeck coefficient, remained nearly constant across all composites, with a peak value of 34 µV/°C at 70 °C for the 15 wt.% composite (Ghosh et al., 2019). The same authors discovered that combining Zinc Oxide (ZnO) with GNP resulted in 141 µV/°C at 70 °C for the 10 wt.% ZnO and 10% GNP composite (Ghosh et al., 2020). In another study, rGO is used to enhance the thermoelectric properties of cement composite and a reading of 1800 μV/◦C at ΔT = 56 °C was obtained by adding as little as 0.15 wt.% rGO (Cui and Wei, 2022). In this test, they have achieved a higher Seebeck coefficient as they tested the sample with free water. However, there are conflicting results in the literature regarding whether the thermoelectric properties of cement-based composites are significantly influenced by the free water in the cement matrix. Early research found that ion movement plays a small, if any, role in the Seebeck effect (Cao and Chung, 2005). In most recent studies it was found that the presence of free water in the cement matrix has a significant impact on the thermoelectric properties of cement-based composites due to the thermal diffusion of free-moving ions like Ca2+, Na+, K+, and OH− in the pore solution which is known as ionic thermoelectric effect (Cui and Wei, 2022).

More recent studies have identified metal oxides as a cost-effective additive that significantly enhances the Seebeck coefficient of cement composites when used as conductive fillers. Fe2O3, Bi2O3, ZnO and MnO2 are some of transition metal oxides that has been added to cement to enhance the thermoelectric properties (Ji et al., 2021, 2016; Wei et al., 2014). Recent research shows that MnO2 can be used as an supplementary material to achieve the high TE potential, even at lower concentrations (Ji et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). In one study, synthesised MnO2 powder having a nanorod structure with a diameter of about 50 nm and a length up to 1.4 μm was replaced with cement at 5 wt.% and achieved a Seebeck coefficient of 3,085 μV/°C (Ji et al., 2018). In another study by Ji et al., 2021, a hybrid concrete composite incorporating MnO2 and carbon fibre (with a diameter of 8 μm and a length of 4–6 mm) was examined. This composite achieved a remarkable Seebeck coefficient of 2880 µV/°C⁻¹ with just 0.8 wt.% MnO2 relative to the cement content. This value was 100 times higher than that of pure carbon fibre-reinforced concrete, indicating that the substantial improvement is largely attributable to the inclusion of the metal oxide. However, in another study by a different researcher, MnO2 is combined with Surface Enhanced Flake Graphite (SEFG), and the results showed that at 75°C, a composite containing 5 wt.% MnO2 (average diameter of 50 nm) and 10 wt.% SEFG (specific surface area of 27 m²/g and a size of 8 μm) achieved only Seebeck coefficient of 16.74 μV/°C (Liu et al., 2021). Note that the above testing has been conducted with different mixtures and different preparation methods, which could all affect the measured properties.

It is clear, in the research scale, that considerably higher thermoelectric properties have been achieved with cement composites. But the current immature technology and low thermoelectric conversion efficiency have limited the large-scale application of cement-based composites. On the other hand, current research is concentrated on the finding of material with the highest Seebeck voltage or the highest Figure of Merit, and less attention is given to the mechanical properties of the cement composite with the addition of the filler as well as the sample preparation method. Only Choi et al., 2022 and J. Wei et al., 2018 measured both compressive strength and thermoelectric properties of cement composite in a same study. However, because the testing procedures for mechanical and thermoelectric properties differed greatly, this was also carried out on different samples. Consequently, in addition to utilising GO and MnO2 in the same testing environment, this study will expand the testing to examine the mechanical properties of the cement composite, making it appropriate for structural applications outside of the lab. First, cement composite samples were tested for their Seebeck coefficient, which indicates the magnitude of the voltage output as a result of a temperature difference across the material. Then each of the samples were tested for the compressive strength to determine their suitability for use as a construction material. Finally, the microstructure of the two composites was studied for further understanding of the material. The objective of this study is to identify a cement mix that maximises its thermoelectric potential whilst still being a structurally sound construction material.

2. Methodology

2.1. Material

Portland cement was used in this study to serve as the base of the cement samples. The properties and chemical composition of the Portland cement is shown in

Table 1.

The standard filler concentration of steel fibres in cement, used in the preparation of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC), typically ranges from 1 wt.% to 1.5 wt.%, as concentrations exceeding this range can lead to a reduction in strength (Song and Hwang, 2004). If the filler is used as a supplementary cementitious material, such as fly ash or silica fume, the concentration can reach up to 30 wt.% and 25 wt.%, respectively, with optimal performance typically achieved at 10 wt.% and 15 wt.%, respectively (Fantu et al., 2021; Mazloom et al., 2004; Sarıdemir, 2013).

Studies have found that incorporating GO into cement at concentrations of up to 0.08 wt.% can significantly increase compressive strength; however, the addition of a polycarboxylic ether-based superplasticizer (PCE) is essential to maintain workability (Ginigaddara et al., 2022; Mohotti et al., 2022). In thermoelectric applications, rGO is typically used in much lower percentages (0–0.15 wt.%) than graphene nanoplatelets (GNP), which is employed in higher concentrations ranging from 5 wt.% to 20 wt.% (Cui and Wei, 2022; Ghosh et al., 2019). This is due to the fact that rGO has a higher surface area (approximately 137.2 m²/g) than GNP (approximately 6.5 m²/g) (Liu et al., 2024). It is also an expensive carbon compound in large quantities and from an economic standpoint, using large amounts of carbon-based materials is hence not feasible.

A study evaluating the mechanical properties of anodic MnO2 nanoparticles found that increasing the filler percentage from 0%, 5%, and 10% gradually increased compressive strength, especially with a 0.4 water cement (w/c) ratio. In higher w/c ratios (0.45 and 0.50), the addition of MnO2 recorded a reduced strength (Torre et al., 2024). In previous studies related to the thermoelectric properties of MnO2 cement composites, up to 5% MnO2 is investigated. In the study by X. Liu et al., 2021, in addition to MnO2, 10% of surface-enhanced flake graphite was used, totalling 15% of fillers. There are also other studies of using metal oxides up to 15% of the weight of cement (Ghosh et al., 2020, 2019; J. Wei et al., 2023). At present, MnO2 is significantly less expensive, costing more than 10 times less, compared to the graphene-based materials, and hence usages of up to 10% are economically justifiable.

In this study, GO and MnO

2 were introduced into the cement mixture at three different ratios. Graphene oxide was added in amounts of 0.025%, 0.05%, and 0.075% of the cement mass (wt.%). Ceylon Graphene Technologies (Sri Lanka) provided the GO in a water dispersion at a concentration of 4 g/L, which was diluted to achieve the required percentages. Chem-supply Pty Ltd (Australia) supplied the MnO

2 in the form of brown-black powder. The powder contained more than 74% manganese dioxide, 0-15% cryptomelane, 0-7% geothite, and 0-4 % quartz (crystalline silica). The powder is a chemically synthesised form of manganese dioxide (MnO

2) designed for use in laboratory and industrial chemical processes, including depolarizers for dry cell batteries, paint, and building materials. MnO

2 used in this study had a specific gravity of 5.026 g/cm³ at 20°C. This powder was first ultrasonically dispersed in water before using it to make cement composite. The study used three different weight ratios (2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 wt.%) of MnO

2.

Table 2 shows the composition of materials used in each mixture. To determine the combined effect of GO and MnO

2, the highest ratios of each material were combined in a single sample, denoted as "GO 0.075 wt.%; MnO

2 7.5 wt.%" in

Table 2.

A higher water-cement ratio increases porosity and overall surface area of the composite and thus promotes charge carrier interaction. It also increases pore connectivity, which aids electron transfer across the composite suggesting a higher water cement ratio (w/c) is preferable in terms of the thermoelectric properties (Cui & Wei, 2024). In contrast, it is known that increasing w/c has a negative effect on compressive strength; thus, a typical 0.4 water-cement ratio is used in this study.

2.2. Sample Preparation

The dimensions of the mould used to fabricate the composites play a pivotal role in improving the TE properties. This is because the increased distance between electrodes can enhance the temperature gradient (ΔT) which directly increases the thermoelectric voltage () according to the Seebeck effect equation (. However, increasing the distance between electrodes can increase the electrical resistance (R) of the material, which may reduce the power output ) even if the voltage increases (Hong et al., 2019). A study by Gandía-Romero et al., 2016 determined that a rectangular composite experiences higher and more linear electrical resistance due to the longer distance electrons are required to travel. The optimal distance between electrodes depends on the thermoelectric properties (Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity, and electrical conductivity) and the specific application. In most studies, which seek to determine the feasibility of different carbon-based additives in enhancing the TE potential of concrete, a rectangular bar is used (Ghosh et al., 2019; Ji et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2018). Several studies have also used a cubic shaped composites with the most common dimension being 50x50x50 mm (Dong et al., 2019; Ghahari et al., 2017; Zuo et al., 2012). In the study by Choi et al., 2022, different moulds were used to test for specific properties; a rectangular bar for electrical properties, a coin for thermal conductivity, and a cube to measure compressive strength. Since the feasibility of TE cement-based materials has been extensively tested over the past two decades with promising results, this project aims to also test the practicality of such materials in the built environment. Hence in this study cubic samples will be used for both thermoelectric and mechanical property testing.

Both GO and MnO

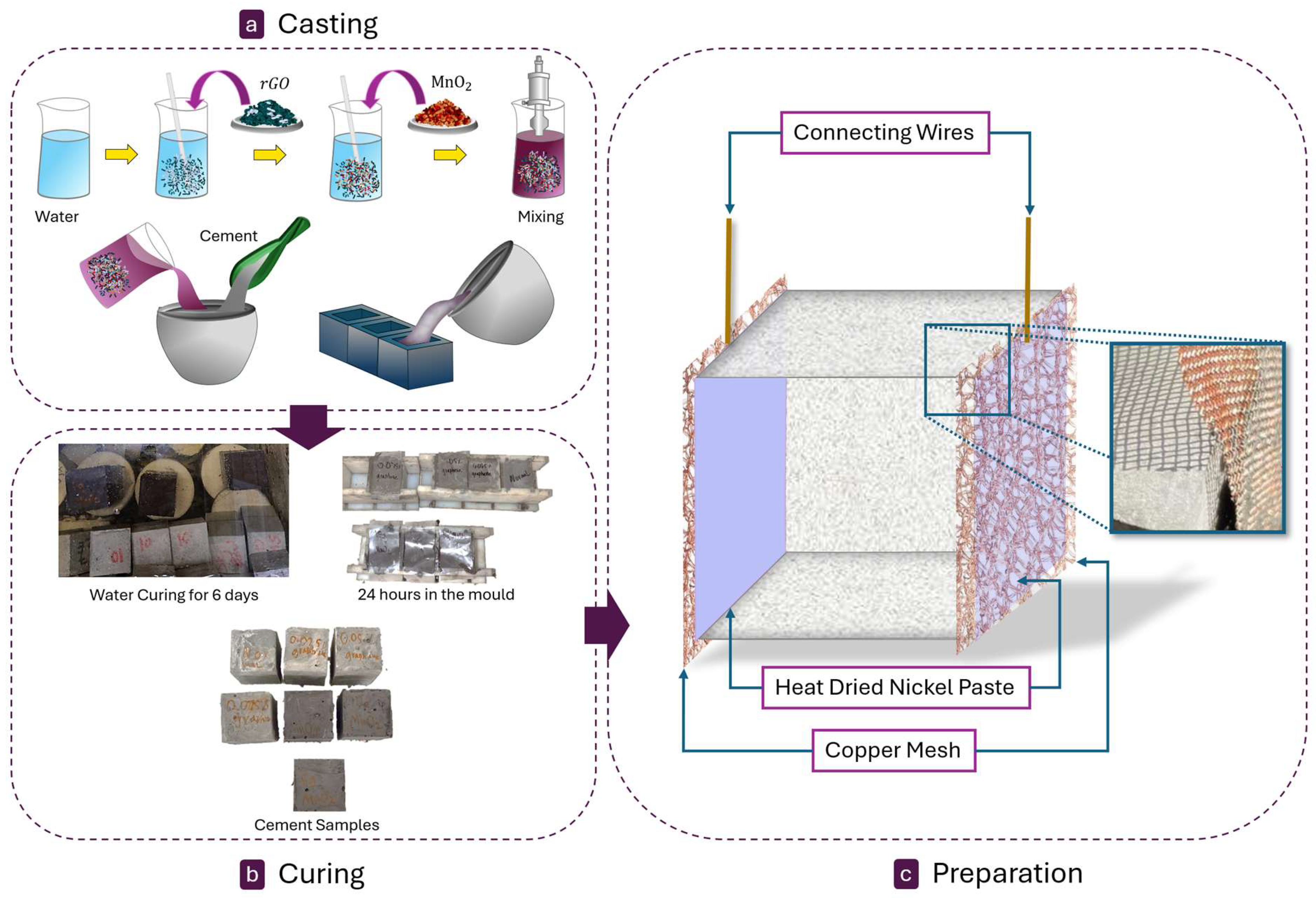

2 were pre-dispersed in the rest of the water required for the mix design. To create the aqueous solution, additives and water were combined and mixed at high speed (2000 rpm) for 30 minutes. To minimise other variables, GO and MnO₂ were mixed using the same technique. After all dry materials were mixed with a Polymix mixer at a speed of 600 r/min for 2 minutes dispersed water was added. Due to the small sample sizes, the mixer exhibited difficulties in mixing the material sufficiently. To reduce this, after the initial 2 minutes of mixing, a spatula was used to hand-mix and re-arrange materials for easier mixing. Then the mixture was mixed for another 2 minutes at a speed of 800 r/min. The prepared mixtures were poured into the moulds and vibrated with a vibrating table for 30 seconds. All samples were cured for 24 hours in the moulds under room temperature conditions. The laboratory storing the cement samples had a room temperature of 21±3 °C. After the initial 24 hours, the samples were removed from the moulds and placed in a water curing tank and cured for 6 days. Note that this curing tank is used for other purposes as well and hence the water had a higher alkalinity value with PH 10. Water curing with higher ions concentration was chosen as it would introduce more ionic thermoelectric properties into the sample, improving readings of the Seebeck coefficient. The process for preparing the samples is illustrated in

Figure 1.

After 6 days of water curing (a total of 7 days), the samples were removed from the curing tank and dried on paper towels. The two opposite surfaces of specimen were then sanded with 80 and 240 grit aluminium oxide sandpaper to create a scabbled edge for mesh adhesion preparation. Copper mesh was cut to fit the size of the cement blocks, with an extra overhang for testing, and adhered to the cement sample with high-performance Nickel paste, which had a thermal conductivity of 2.6 W/mK. Nickel paste was then exposed to a heat gun for 2 minutes on each side to solidify and improve adhesion. In the experiment, using an embedded mesh would have required extending the specimen in one direction to accommodate the mesh, then trimming and resizing to produce standard 50 mm cubic samples for compression testing. Hence, an externally applied copper mesh was selected as the preferred option to simplify the preparation process while ensuring compatibility with the testing stages.

2.3. Seebeck Coefficient Testing

A hotplate with variable temperature was used to simulate unidirectional heat ranging from room temperature (21±2 °C) to 65 °C. The specimen was placed on the hot plate with one copper mesh side directly in contact with the plate. One

K type thermocouple was used in between the composite samples to measure the real temperature at the surface without depending on the results of the hot plate. Readings from the thermocouple were connected to 12 channel temperature recorder by Lutron (BTM-4208SD). A digital multimeter (Micron Q1134A) was connected to each copper mesh through connecting wires. Since the measurements were taken from different devices, a timer was used to record readings. The test setup used for the thermoelectric testing is shown in

Figure 2 (a). Readings were taken at every 10 s until the hotplate surface temperature reaches 65 °C or more. The hotplate was provided sufficient time to return to room temperature before testing another sample to maintain consistency. These results were used to calculate the Seebeck coefficient of the material. During the experiment, the temperature on one side of the sample was measured with a thermocouple, while the temperature on the other side was not directly measured and was assumed to be room temperature. It was identified that thermal convection from the heated side may cause the temperature at the opposite end to increase above room temperature over time. However, assuming this end to be at room temperature results in a higher calculated thermal gradient and, consequently, a lower Seebeck coefficient than the actual value, which represents a conservative estimate.

2.4. Compression Testing

After completion of the thermoelectric testing, same samples were further prepared for the compression testing. This way, the need for multiple samples of each proportion to average out the variations in two separate tests were not needed. Attached copper sheets were first removed from the heat dried nickel paste and the nickel paste was scraped out. Though the sample could have been tested in the same direction as the thermoelectric test, it was tested for another direction as removing the nickel paste developed uneven surface. Compression testing of the samples was carried out 28 days after the initial casting. A Technotest compression machine with a load capacity of 3000 kN as shown in

Figure 2 (b) was used for compression testing.

2.5. Microstructral Analysis

The surface morphology and elemental composition of the cement-based composites after 28 days of aging were analysed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) coupled with Electron Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS). Only GO 0.075 wt.%, MnO

2 7.5 wt.% and GO 0.075 wt.% + MnO

2 7.5 wt.% samples were used in these characterisations. Selection of these samples was based on the results of the Seebeck coefficient and compression testing results. These techniques allowed the observation of the hydration characteristics of three mixtures within their hydrated matrix. The observation surface of each specimen was polished to eliminate any irregularities that could interfere with the spectroscopy analysis. This was done by sequentially polishing the surface with sandpaper grits of 120, 200, 400, 800, 1000, 1500 and 2000, followed by diamond 1 µm polishing paper with compatible 1 µm lubricant. To prevent interference from surface charge accumulation during scanning electron microscopy, each sample surface was then made conductive by applying a 5 nm carbon coating. Specimens prepared for the chemical characterisation are shown in

Figure 2 (c).

Backscattered electron imaging (BSE) in a SEM detects electrons that are deflected after elastic collisions with atoms, making it more sensitive to the atomic number of the elements involved in the interaction volume. In this study, BSE imaging was used for qualitative identification, visualization of microphase distribution, and porosity quantification at each hydration stage, employing the Hitachi8 SU7000 instrument with a working distance of 10 mm, an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, and a beam current of 78 µA. Electron Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) imaging allows for the qualitative identification of elemental distribution using the X-rays emitted from elements across a defined planar area. A beam calibration was conducted using polished copper (Cu) to ensure the stability of the current. Chemical elemental maps were obtained using the EDS Oxford Aztec system, which is equipped with a 100 mm² X-Max silicon drift detector. The resolution for acquiring the EDS hypermaps was set to 365×319, and the scanning time for each location was approximately 30 minutes, with a dwell time of 100 seconds. The maps were configured to display the atomic concentration of the specimen. To minimize noise during the data acquisition process, it is essential to optimize the signal at the information level, as shorter acquisition times can result in elevated noise levels. To address this, the binning function was utilized during the map scanning process, combining signals from adjacent points to generate an averaged signal, thereby reducing the overall noise.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Thermoelectric Power Generation

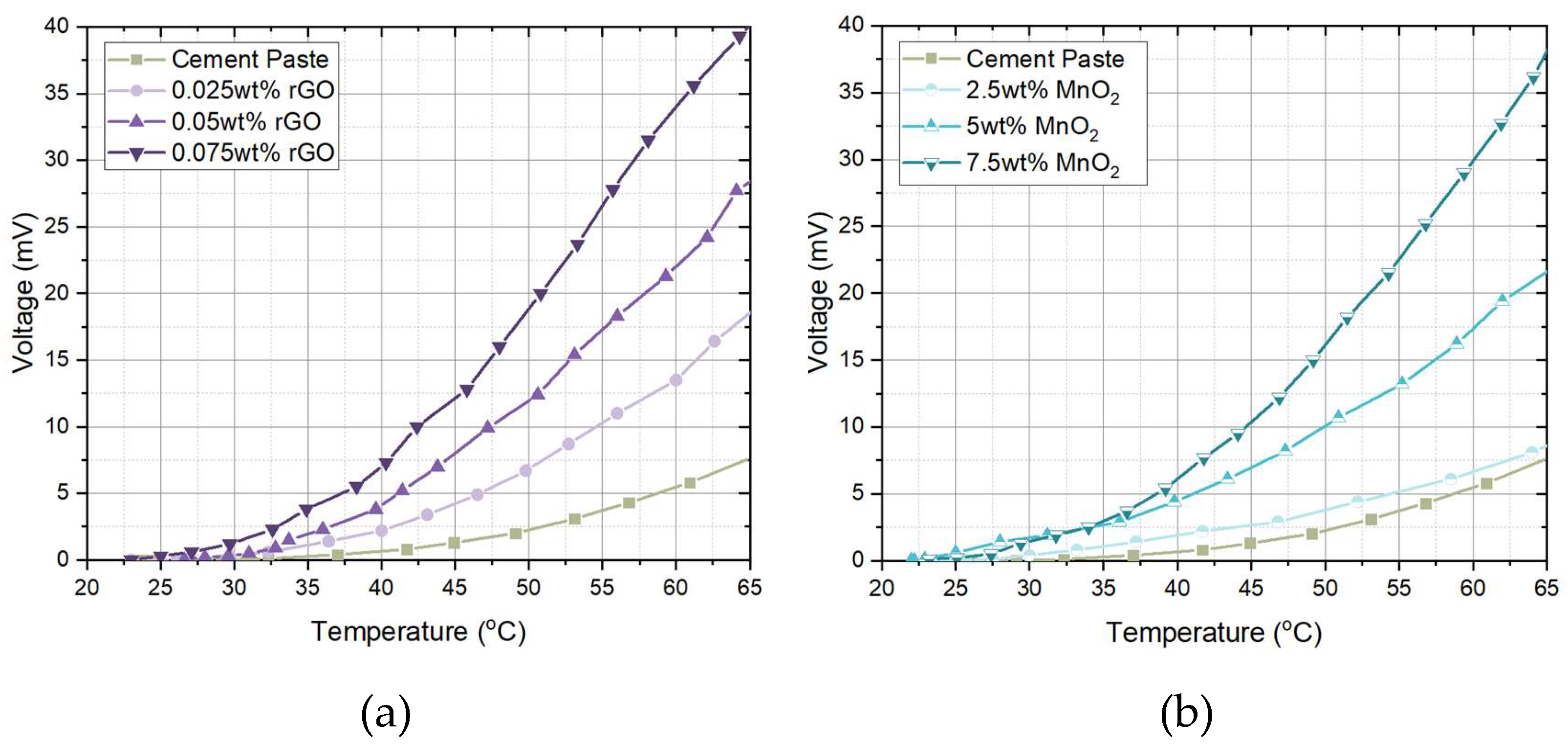

As the first stage of the testing, all seven composites underwent testing to measure the ability of generating voltage when supplied with a thermal gradient. Each sample was tested separately at the same room temperature and all thermal and electrical measurements were recorded at given time intervals. The results of the voltage and the temperature at the surface touching the hot plate are illustrated in

Figure 3. In every sample the amount of thermoelectricity generated increased with the increasing temperature gradient. The control sample, which was not dried before testing, was expected to produce a certain amount of thermoelectricity, resulting in a thermoelectric voltage of 7.5 mV at 65°C.

As shown in

Figure 3 (a), increasing GO content results in a higher voltage at all temperatures. 0.075 wt.% GO sample generated the highest amount of voltage at the 65°C of value 40 mV. As shown in

Figure 3 (b), increasing MnO

2 content also results in higher voltage at all temperatures. Highest amount of voltage 37 mV was recorded with the 7.5 wt.% replacement of MnO

2 with cement. The sample containing both materials (GO 0.075 wt.% and MnO

2 7.5 wt.%) achieved the highest thermoelectric voltage of 56 mV at 65 °C as shown in

Figure 3 (c). More than 7.5 mV is considered as a usable amount of voltage in IoT related applications (Wu et al., 2023). With GO, MnO

2 and GO+MnO

2 this was achieved at surface temperatures of 41 °C, 43 °C and 38°C, which is common in surface of a concrete that is exposed to the sun during a summer month.

3.2. Seebeck Coefficient

Seeback coefficient changes with the thermal gradient and the results shown in

Figure 4 are calculated at the hotplate temperature of 65 °C or thermal difference of 44 °C. Results found that GO and MnO

2 both increased the Seebeck coefficient of the samples with increasing weight percentages. A maximum Seebeck coefficient of 920μV/°C was achieved with 7.5 wt.% MnO

2. This is comparable to the maximum coefficient of 900 μV/°C achieved by 0.075 wt.% of GO. The addition of MnO

2 and GO together in the same sample improved the Seebeck coefficient of the cement composite up to 1320 μV/°C. This represents a 45% increase compared to the highest values observed in GO-only or MnO₂-only composite samples, indicating that neither GO nor MnO₂ reached the percolation threshold at their individual maximum additive concentrations. This verifies that the inclusion of cheaper alternative metal oxides like MnO

2, graphene enhanced concrete can achieve efficient thermoelectric properties while reducing total costs. A comparison of the results achieved in the current study with relevant studies from the literature is presented in

Figure 5, highlighting the comparatively significant thermoelectric performance observed in this work. Notably, this study with 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 and 0.075 wt.% GO demonstrated a 7765% improvement in thermoelectric performance compared to the study by X. Liu et al., 2021, which combined 5 wt.% MnO

2 with 10% SEFG. Additionally, it showed a 916% improvement compared to the study by Ghosh et al., 2020, which combined 10 wt.% ZnO with 10% GNP. However, the comparison of these studies should be approached with caution, as the experimental conditions employed in the respective studies differ significantly.

3.3. Strength Testing

The compressive strengths of the composites are presented in

Figure 6. The control sample demonstrated a compressive strength of 37 MPa. The addition of rGO 0.025 wt.% increased the compressive strength to 46.5 MPa; however, further increases in GO content led to a reduction in compressive strength. This trend contrasts with findings from other researchers, who observed a consistent increase in compressive strength with GO additions up to 0.08 wt.% (Ginigaddara et al., 2022; Mohotti et al., 2022). The difference is due to the fact that no PCE is used in sample preparation, and this has affected the workability of the cement. In this case, when preparing the GO-incorporated samples, materials agglomerated during the mixing process. As a result, the sample may have been set with increased porosity, weakening its overall structure and making it more susceptible to failing under compressive forces. The effect of admixtures such as polycarboxylic ether-based superplasticizer on the thermoelectric properties of cementitious materials has not yet been investigated in the literature, hence no plasticiser or admixture used in this study.

The compressive strength of the cement composite improved significantly with the addition of MnO2, though further increases resulted in only minor enhancements. The strength increment observed in this study aligns with findings from the literature for a 0.4 w/c ratio (Torre et al., 2024). When preparing the samples, the incorporation of MnO2 had the opposite effect of GO, resulting in a very fluid mixture with no agglomeration. This facilitated easier sample moulding and most likely reduced porosity, resulting in a higher compressive strength up to 63 MPa. Surprisingly, the sample with combined GO and MnO2 resulted in poor compressive strength properties though it recorded the highest thermoelectric properties. The compressive strength result of this sample was lower than those of the control sample, with a recorded value of 12.5 MPa.

As discussed, the effect of GO and MnO₂ on the workability of the mixture played a significant role in the compressive strength results. However, the workability comparison between mixtures is not quantitatively discussed in this paper, as only two main parameters (strength and Seebeck coefficient) are considered within the scope of this multi-objective analysis. It is acknowledged that maintaining the other parameters as closely as possible would lead to a better comparison; however, achieving identical workability is challenging with two distinct types of fillers and could result in differing w/c ratios, which are far more critical to keep constant. Interested readers can refer to (Torre et al., 2024) for additional comparisons involving the addition of MnO₂ and to (Fonseka et al., 2024) for comparisons involving the addition of GO.

3.4. Comparision of Multifuctional properties

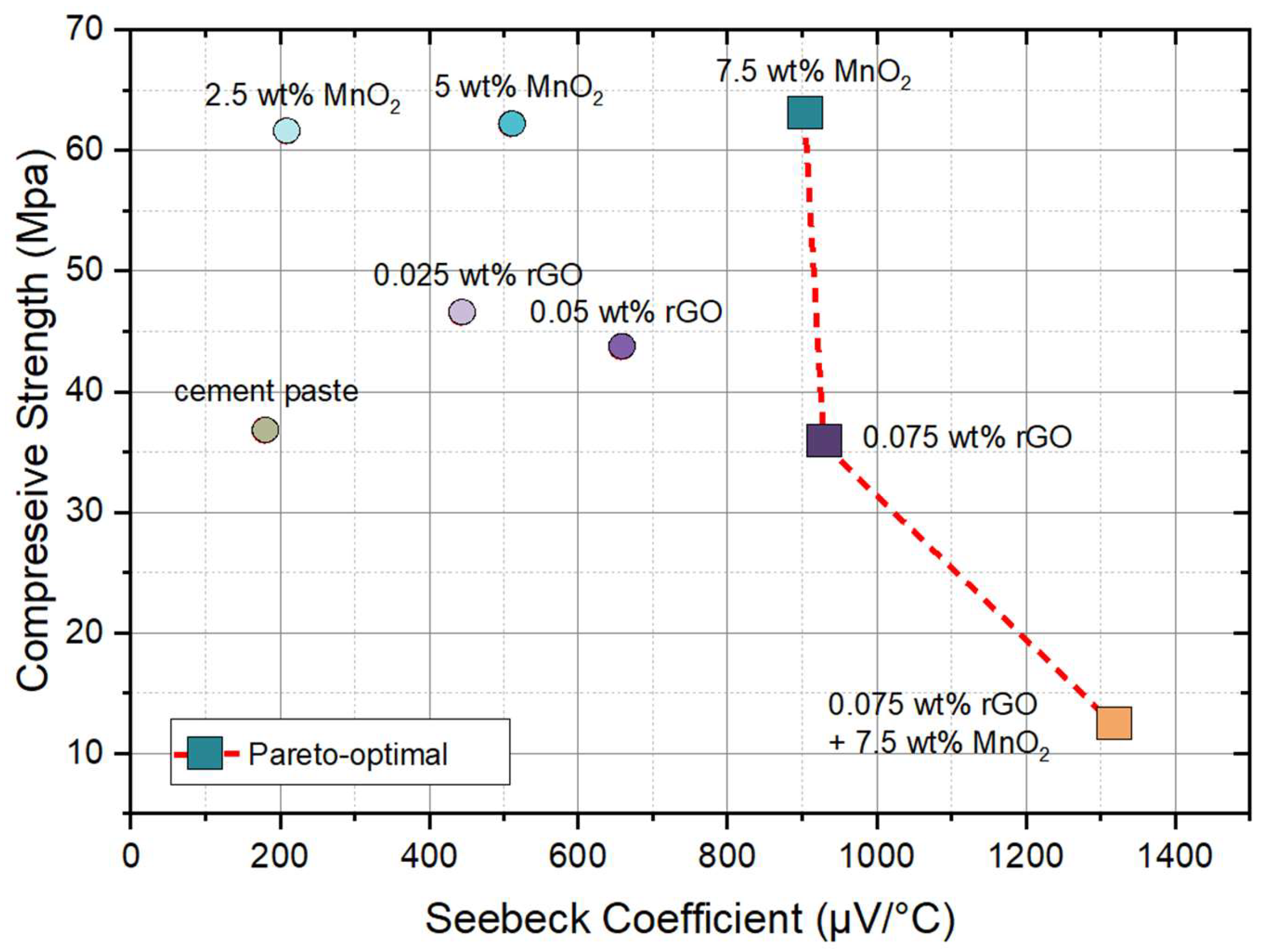

A Pareto analysis was performed as illustrated in

Figure 7 to identify non-dominated solutions among the eight formulations based on the two key objectives: Seebeck coefficient and compressive strength. Three samples emerged as Pareto-optimal: (i) 0.075 wt% GO + 7.5 wt% MnO₂, (ii) 7.5 wt% MnO₂, and (iii) 0.075 wt% GO. The 7.5 wt% MnO₂ sample offers the highest compressive strength (63.07 MPa) while maintaining a relatively high Seebeck value (903.67 μV/K). In contrast, 0.075 wt% GO + 7.5 wt% MnO₂ sample maximizes the Seebeck coefficient (1319.20 μV/K) but exhibits substantially lower compressive strength (12.43 MPa). 0.075 wt% GO sample provides an intermediate balance, featuring a Seebeck coefficient of 929.08 μV/K and a compressive strength of 35.8 MPa. These non-dominated points demonstrate that no single composition can achieve both thermoelectric and strength merits optimally. Hence, it is recommended that researchers and practitioners must priorities thermoelectrical versus mechanical performance when selecting Pareto-optimal solutions for their specific applications.

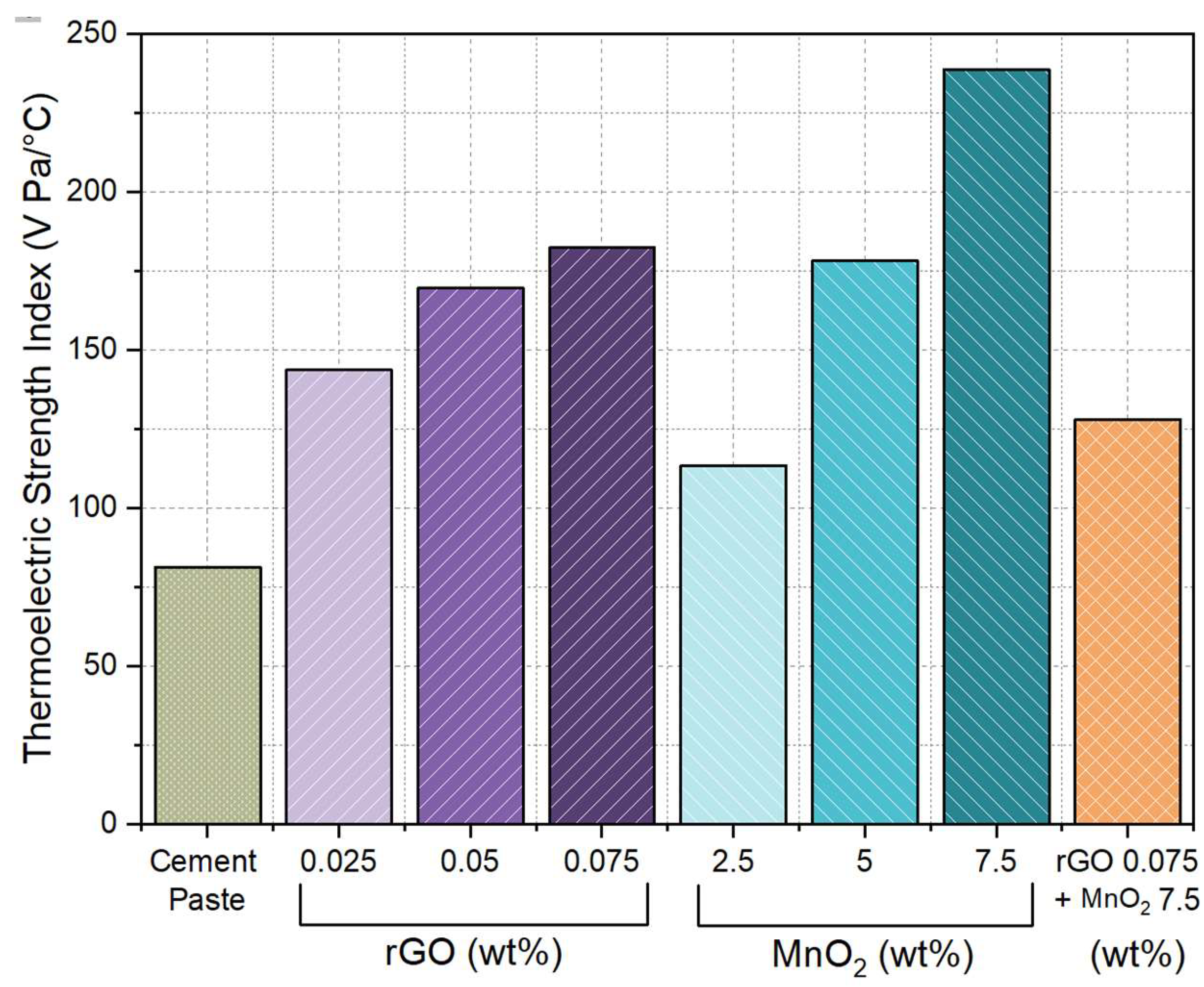

Figure of merit (ZT) and Power Factor (PF) are used to find new superior thermoelectric materials or compare thermoelectric materials dimensionless. Similarly, in this paper, we introduce the Thermoelectric Strength Index (TSI) as given in Eq. 1 for evaluation of material in terms of both thermoelectric and strength properties considering equal weights. In this equation,

is the compressive strength of the material,

is the voltage difference and

is the temperature difference between the samples. Calculated TSI factors for all seven samples are shown in

Figure 8. From these results also it is evident that the MnO

2 7.5 wt.% is the best composite for thermoelectric modules that are both structurally viable and efficient.

3.5. Microstructral Properties

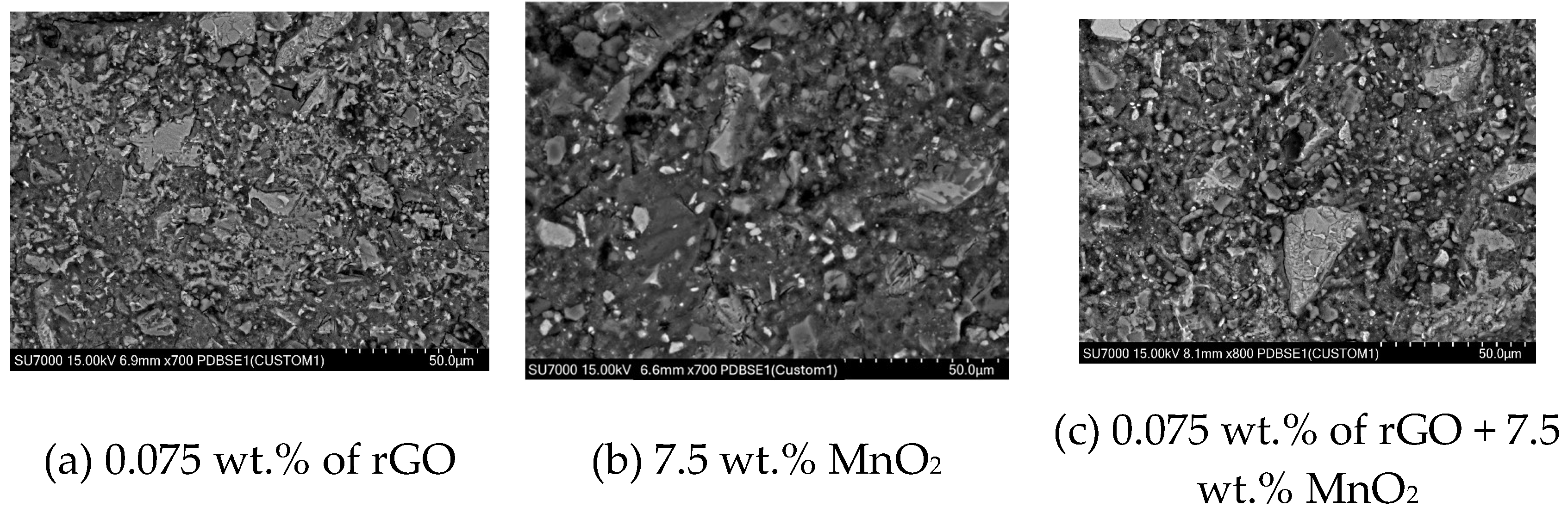

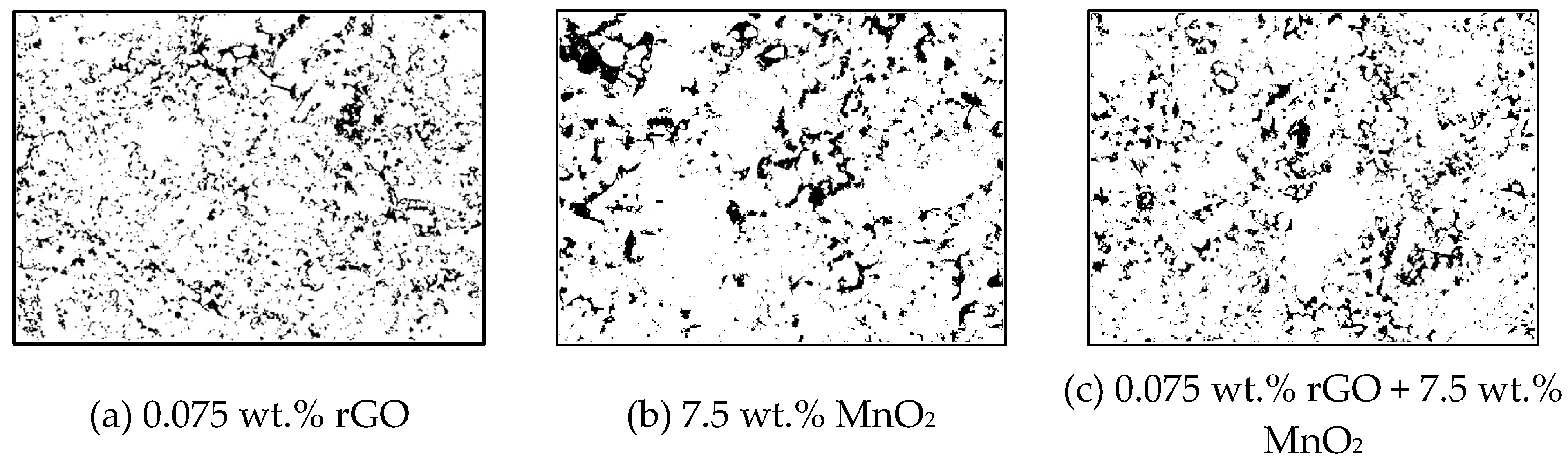

The backscattered electron (BSE) imaging results, as depicted in

Figure 9, provide a visual representation of the specimens under investigation. Analysis revealed that the specimen containing 0.075 wt.% GO exhibited a lower degree of hydration and increased porosity in comparison to the sample incorporating 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 (

Figure 9 (a) &(b)). This is associated with the rapid water absorption in the GO mixture during the preparation phase, which reduces water availability for cement hydration and increases porosity during casting process without any additional water retarding admixtures. When analysing the microstructure of 0.075 wt.% GO + 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 specimen, a higher porosity and loose particles were visible on the surface (

Figure 9 (c)). This was also noticed during the polishing of the specimen, that the surface lost its particles very easily. These increased porosity and loose particles further validating the low compressive strength observation in this sample.

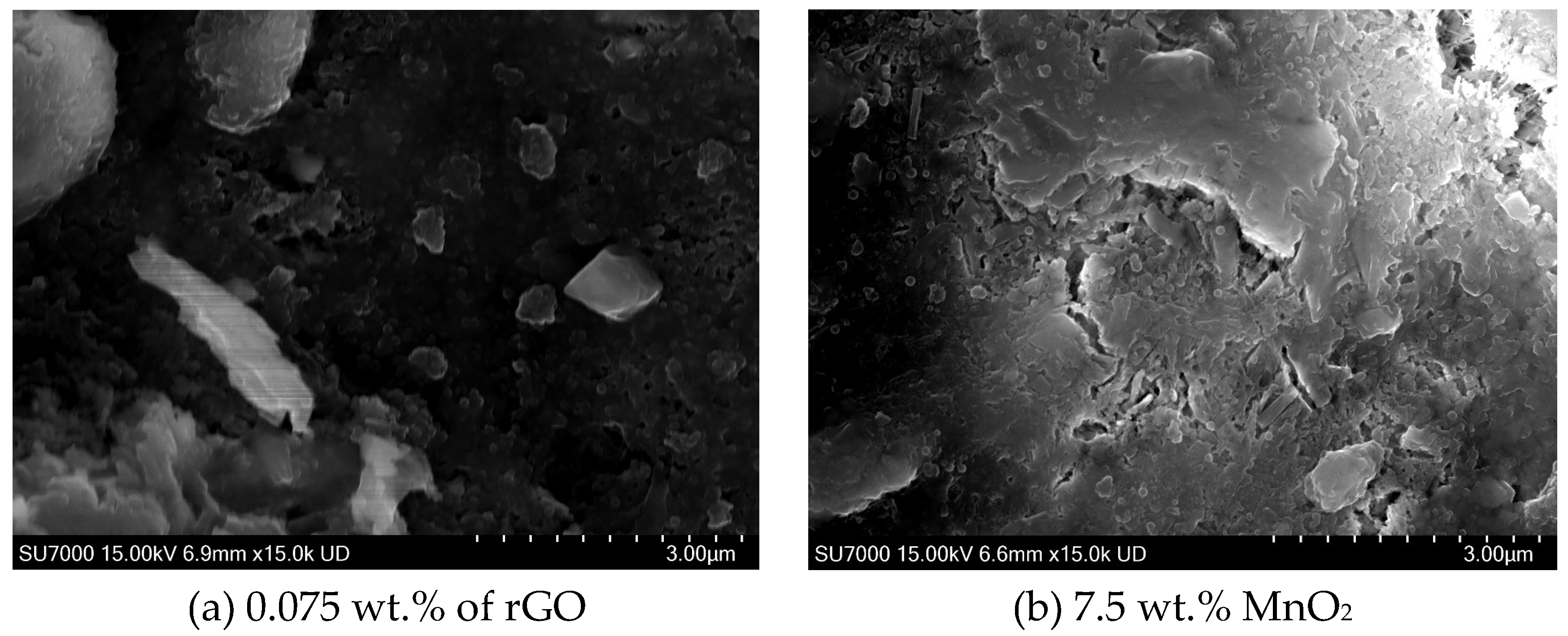

Figure 10 shows the BSE imaging results at higher magnification for specimens containing 0.075 wt.% GO and 7.5 wt.% MnO

2. The particulate material shown in

Figure 10 (a) is unreacted cement hydration growth. From

Figure 10, microscale porosity is evident in the cement matrix containing 7.5 wt.% MnO

2, whereas the matrix incorporating 0.075 wt.% GO exhibits comparatively reduced microporosity (

Figure 10). This is due to the GO nucleation site distribution throughout the matrix and these sites have reduced the formation of micro scale capillary pore formation.

Since the surface of the specimen was polished to facilitate accurate elemental analysis using EDS, qualitative information on the undisturbed crystallography and surface topography of microphases on the specimen surface was observed by scanning larger air void areas using secondary electron imaging (

Figure 10). The morphology of the hydrated region in the 0.075 wt.% GO and 7.5 wt.% MnO₂ specimens is shown in

Figure 10. The hydrated matrix in the 7.5 wt.% MnO₂ specimen has formed a densely packed calcium silicate hydrate structure, compared to the hydrated region in the 0.075 wt.% GO specimen, which exhibits comparatively higher porosity.

The thermoelectric conductivity of concrete is related to the interconnection between the conductive filler as well as the porous. Using the BSE imaging, micro porosity can be segmented through specifically developed MATLAB programs. The microporosity in the 0.075 wt.% GO + 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 mixture (

Figure 11(c)) is more evenly distributed throughout the material compared to that of 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 mixture (

Figure 11(b)), because addition of GO calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) nucleation sites. This enhanced distribution of interconnected microporosity and resulted in ionic thermoelectricity can be identified as the contributing factor for the improved thermoelectricity in 0.075 wt.% GO + 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 sample. Further, the strength variation in three specimen types is also linked to the porosity distribution. Gel pores do not adversely influence the strength of concrete, although capillary porosity and air voids do. The number of pores in the hydrated region of both 0.075 wt.% GO and 0.075 wt.% GO + 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 specimens is higher, whereas the hydrated matrix in 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 specimen has very small amount of porosity (

Figure 9(b)).

Micro-porosity significantly affects both thermoelectric conductivity and strength. Interconnected micro-porosity can beneficially contribute to the conductivity of the concrete (Wei et al., 2020). However, excessive porosity can lead to a reduction in mechanical strength, as the presence of voids weakens the structure and makes it more susceptible to cracks. This, in turn, can negatively impact the durability. Therefore, a balanced level of micro-porosity is crucial to optimize both thermoelectric conductivity and strength, ensuring long-term performance and stability of the material in various applications.

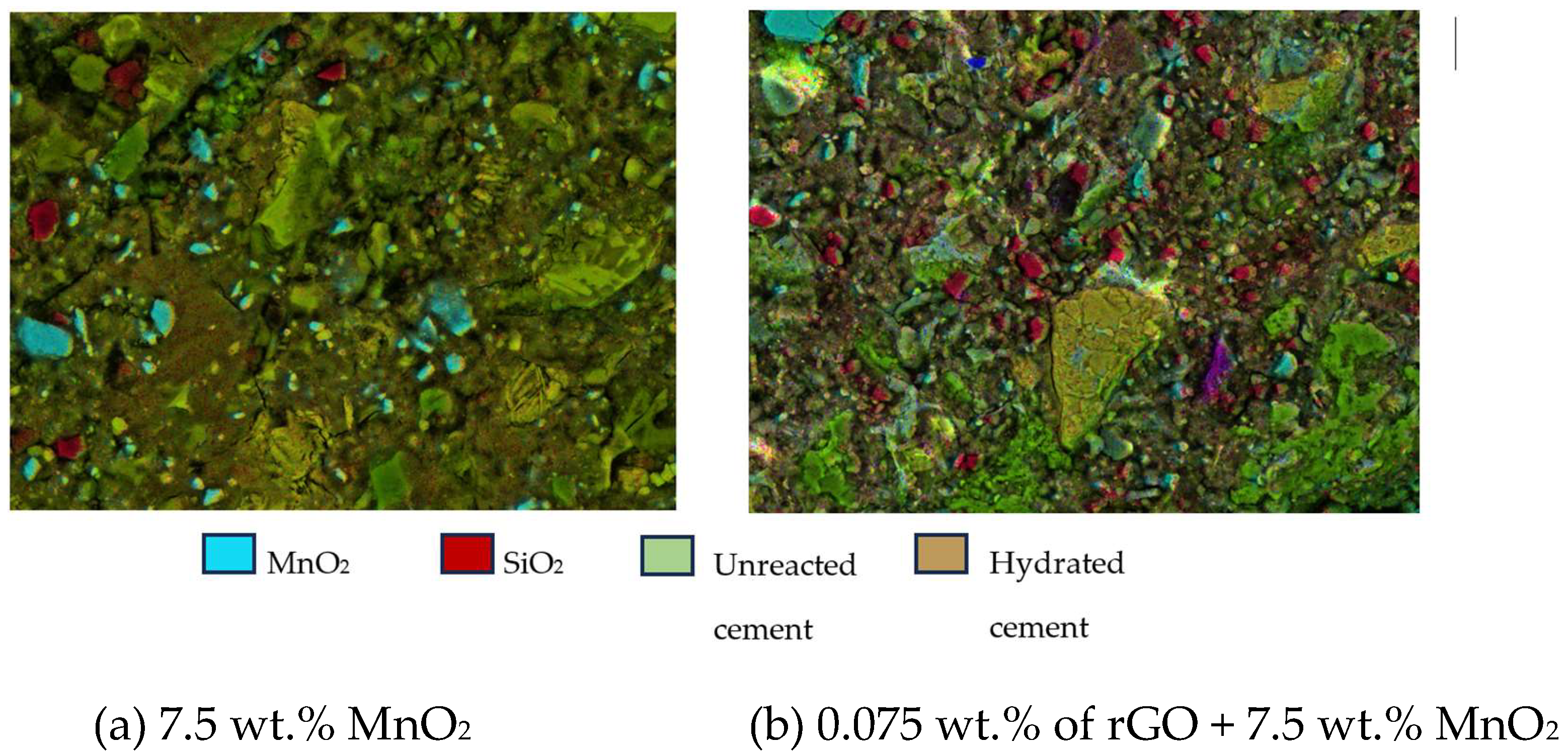

When observing the manganese (Mn) elemental map of 7.5 wt.% MnO

2 specimen, unreacted Mn particles were visible, and Mn concentrations were visible in the hydrated areas in lower pixel intensities (

Figure 12). This indicates that MnO

2 has contributed to densifying the hydrated matrix. Although many studies suggest that MnO

2 mostly stays as a filler with less reactivity, it has been observed that manganese dioxide with nanometric-sized particles absorbs water forming nucleation sites in cement hydration, contributing to improving concrete in compressive and flexural strength. In order to visualize the unreacted particle distribution, phases were segmented separately using EDS elemental mapping as shown in

Figure 12. Since the 0.075 wt.% GO + 7.5 wt.% MnO₂ specimen exhibited low strength, it wore off easily during polishing due to abrasion, preventing the surface from achieving the similar smoothness as the other two specimens. This observation was evident in

Figure 12(b), where many unreacted cement particles, SiO₂, and MnO₂ particles resurfaced due to the damaged hydrated matrix due polishing. In contrast, the 7.5 wt.% MnO₂ specimen maintained its structural integrity in the hydrated matrix during polishing, resulting in a smoother surface.

3.6. Testing Limitations

During the Seebeck coefficient testing, slight inconsistencies in heating rates were observed across the experiments. Achieving accurate voltage readings as a function of temperature requires a constant rate of temperature increase (Ghahari et al., 2017; J. Wei et al., 2023). However, this condition could not be maintained in our study due to the limitation of the hot plate. Therefore, for the calculation, variation of the temperature and voltage was measured at fixed time intervals.

The samples were heated only until the hotplate reached the 65°C limit, under the assumption that the opposite end of the sample remained at room temperature. This was practically achieved by heating the samples at a rapid rate, reaching 65°C within a 2–3-minute time window. Additionally, this study did not assess the effect of the heating rate on the Seebeck coefficient readings, which could also influence the results. Utilizing a Peltier thermal system could have allowed precise control over the heating rate, potentially improving the reliability and consistency of the measurements.

Another limitation of this study was the use of nickel paste instead of silver paste to enhance thermal contact between the hotplate and the cement composites. Although silver paste, known for its superior thermal conductivity, has been widely used in previous studies (Wen and Chung, 2000; Ji et al., 2021; Cui and Wei, 2022), its significantly higher cost hindered its use. While nickel paste is a viable alternative, its lower thermal conductivity (2.61 W/m·K) compared to silver paste (9.61 W/m·K) could have influenced the test results, particularly given the low magnitude of the readings obtained.

In this study, the Seebeck coefficient is used to compare the thermoelectric properties of the material, in the same way that compressive strength is used to compare mechanical strength. In the future, other parameters, such as thermoelectric efficiency as measured by the figure of merit and tensile strength, should be considered in the optimisation analysis.

To accurately measure compressive strength, it is standard practice to test multiple samples of the same composite and average the results. However, this study was limited to a single sample for compressive strength testing. To supplement this limitation, microstructural analysis was conducted to evaluate the consistency of the composite. The small volume of material used in this study also compromised the mixing process, which may have affected the results.

Furthermore, the development of compressive strength for GO and MnO2 may differ from that of standard cement paste, but this aspect was not investigated in the current study. Notably, MnO2 has been observed to provide high early strength compared to ordinary cement, suggesting that compressive strength testing should be conducted at different time intervals to capture these variations.

4. Conclusions & Recommendations

Both MnO2 and GO significantly improved thermoelectric properties when compared to the control sample. Increasing MnO2 and GO resulted in increased thermoelectric properties, indicating that the percolation threshold was not met within the experimental filler limits. The combination of GO and MnO2 resulted in 40% higher voltage readings than the highest concentration of GO- or MnO2- alone reaching a Seebeck coefficient of 1320 μV/°C and maximum voltage of 56 mV. The combination of GO and MnO2 samples showed the highest Seebeck coefficient but the lowest compressive strength results.

To identify the trade-offs, a Pareto analysis is performed. Non-dominated points in the Pareto-optimal front demonstrate that no single composition can achieve both thermoelectric and strength merits optimally. A new parameter, the thermoelectric strength index, was hence developed to measure the combined properties of the composite and found 7.5 wt.% MnO2 produced the best strength and thermoelectric performance showcasing the best structural viable and efficient composite from the materials tested.

When investigating the microstructural characteristics through conventional SEM/EDS characterization, it was observed that the GO batch used in this study appeared to adsorb free water from the mix because the hydrated matrix seemed to be less porous compared to other mixes. However, MnO2 seemed to be hydrated in the cement matrix along with the cement hydration and the unreacted MnO2 seemed to be acting as a filler and at the same time, contributing to the formation of a denser hydrated matrix. When MnO2 and GO are combined, the matrix formation is weak, and it is recommended to determine the optimum GO dosage to increase the mechanical performance of MnO2 and GO combined composite to retain the strength while increasing the thermoelectric properties.

Although cement-based thermoelectric composites exhibit promising potential for practical civil engineering applications, such as building facades and pavements, further investigation into the mechanical performance and durability of cement-based thermoelectric composites is necessary to fully establish their suitability. Also, this study employed the traditional lower limit of the water-cement ratio, 0.4 maximising the strength properties, but future research could investigate the effect of water-cement ratio and effect of water retarding admixtures in enhancing the thermoelectric properties of cement composites along with the mechanical properties by using the developed thermoelectric strength index parameter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jude Shalitha Perera; Formal analysis, Jude Shalitha Perera, Anuradha Silva, Aathavan Kuhanandha, Lochlan Hau and Philip Trinh; Investigation, Anuradha Silva, Aathavan Kuhanandha, Lochlan Hau and Philip Trinh; Methodology, Jude Shalitha Perera, Shanaka Baduge, Aathavan Kuhanandha, Lochlan Hau and Philip Trinh; Project administration, Priyan Mendis and Shanaka Baduge; Resources, Jude Shalitha Perera, Priyan Mendis and Shanaka Baduge; Supervision, Jude Shalitha Perera, Priyan Mendis and Shanaka Baduge; Validation, Aathavan Kuhanandha, Lochlan Hau and Philip Trinh; Visualization, Anuradha Silva; Writing – original draft, Jude Shalitha Perera and Anuradha Silva.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available on request from the authors. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding support provided by the University of Melbourne through capstone budget allocation. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Thusitha Ginigaddara, Danula Udumulla and Pasadi Devapura for their technical assistance.

References

- Akbari, H., & Levinson, R. (2008). Evolution of Cool-Roof Standards in the US. Advances in Building Energy Research, 2(1), 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., & Chung, D. D. L. (2005). Role of moisture in the Seebeck effect in cement-based materials. Cement and Concrete Research, 35(4), 810–812. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K., Kim, D., Chung, W., Cho, C., & Kang, S.-W. (2022). Nanostructured thermoelectric composites for efficient energy harvesting in infrastructure construction applications. Cement and Concrete Composites, 128, 104452. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., & Wei, Y. (2022). Mixed “ionic-electronic” thermoelectric effect of reduced graphene oxide reinforced cement-based composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, 128, 104442. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W., Li, W., Long, G., Tao, Z., Li, J., & Wang, K. (2019). Electrical resistivity and mechanical properties of cementitious composite incorporating conductive rubber fibres. Smart Materials and Structures, 28(8), 085013. [CrossRef]

- Fantu, T. , Alemayehu, G., Kebede, G., Abebe, Y., Selvaraj, S. K., & Paramasivam, V. (2021). Experimental investigation of compressive strength for fly ash on high strength concrete C-55 grade. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46, 7507–7517. [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Romero, J. M. , Ramón, J. E., Bataller, R., Palací, D. G., Valcuende, M., & Soto, J. (2016). Influence of the area and distance between electrodes on resistivity measurements of concrete. Materials and Structures 50(1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S. , Ghafari, E., & Lu, N. (2017). Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on thermoelectric properties of cement composite for waste heat harvesting. Construction and Building Materials 146, 755–763. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. , Harish, S., Ohtaki, M., & Saha, B. B. (2020). Enhanced figure of merit of cement composites with graphene and ZnO nanoinclusions for efficient energy harvesting in buildings. Energy 198, 117396. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. , Harish, S., Rocky, K. A., Ohtaki, M., & Saha, B. B. (2019). Graphene enhanced thermoelectric properties of cement based composites for building energy harvesting. B. ( 202, 109419. [CrossRef]

- Ginigaddara, T. , Ekanayake, J., Mendis, P., Devapura, P., Liyanage, A., & Vaz-Serra, P. (2022). An Introduction to High Performance Graphene Concrete. Electronic Journal of Structural Engineering, 22, Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmid, H. J. (2014). Bismuth Telluride and Its Alloys as Materials for Thermoelectric Generation. Materials, 7, 2577–2592. [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-H. , Chong, S.-H., & Cho, G.-C. (2019). Theoretical Study on Geometries of Electrodes in Laboratory Electrical Resistivity Measurement. Applied Sciences, 9, Article 19. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T. , Zhang, S., He, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., & Li, W. (2021). Enhanced thermoelectric property of cement-based materials with the synthesized MnO2/carbon fiber composite. Journal of Building Engineering, 43, 103190. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T. , Zhang, X., & Li, W. (2016). Enhanced thermoelectric effect of cement composite by addition of metallic oxide nanopowders for energy harvesting in buildings. Construction and Building Materials 115, 576–581. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., & Li, W. (2018). Effect of Manganese Dioxide Nanorods on the Thermoelectric Properties of Cement Composites. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 30. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. , Lin, K., Zhou, M., Wallwork, A., Bissett, M. A., Young, R. J., & Kinloch, I. A. (2024). Mechanism of gas barrier improvement of graphene/polypropylene nanocomposites for new-generation light-weight hydrogen storage. Composites Science and Technology, 249, 110483. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Qu, M., Nguyen, A. P. T., Dilley, N. R., & Yazawa, K. (2021). Characteristics of new cement-based thermoelectric composites for low-temperature applications. Construction and Building Materials, 304, 124635. [CrossRef]

- Mazloom, M. , Ramezanianpour, A. A., & Brooks, J. J. (2004). Effect of silica fume on mechanical properties of high-strength concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites, 26, 347–357. [CrossRef]

- Mohotti, D. , Mendis, P., Wijesooriya, K., Fonseka, I., Weerasinghe, D., & Lee, C.-K. (2022). Abrasion and Strength of high percentage Graphene Oxide (GO) Incorporated Concrete. Electronic Journal of Structural Engineering, 22, Article 01. [CrossRef]

- Moosberg-Bustnes, H., Lagerblad, B., & Forssberg, E. (2004). The function of fillers in concrete. Materials and Structures, 37(2), 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Nichol, J., & Wong, M. S. (2005). Modeling urban environmental quality in a tropical city. Landscape and Urban Planning, 73(1), 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, A., & Kinnane, O. (2017). The impact of thermal mass on building energy consumption. Applied Energy, 198, 108–121. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. , Ding, L., Fiorito, F., Oldfield, P., Osmond, P., Paolini, R., Prasad, D., & Synnefa, A. (2017). Passive and active cooling for the outdoor built environment – Analysis and assessment of the cooling potential of mitigation technologies using performance data from 220 large scale projects. Solar Energy, 154, 14–33. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. , Papanikolaou, N., Livada, I., Koronakis, I., Georgakis, C., Argiriou, A., & Assimakopoulos, D. N. (2001). On the impact of urban climate on the energy consumption of buildings. Solar Energy, 70, 201–216. [CrossRef]

- Sarıdemir, M. (2013). Effect of silica fume and ground pumice on compressive strength and modulus of elasticity of high strength concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 49, 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Senevirathne, D. M. , Jayasooriya, V. M., Dassanayake, S. M., & Muthukumaran, S. (2021). Effects of pavement texture and colour on Urban Heat Islands: An experimental study in tropical climate. Urban Climate, 40, 101024. [CrossRef]

- Song, P. S. , & Hwang, S. (2004). Mechanical properties of high-strength steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 18, 669–673. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. , Li, Z., Mao, Q., & Shen, D. (1998a). Study on the hole conduction phenomenon in carbon fiber-reinforced concrete. Cement and Concrete Research, 28, 549–554.

- Sun, M. , Li, Z., Mao, Q., & Shen, D. (1998b). Thermoelectric percolation phenomena in carbon fiber-reinforced concrete. Cement and Concrete Research, 1712, 1707–1712. [CrossRef]

- Torre, A. , Shuan, L., Quintana, N., Moromi, I., Basurto, J., Mosquera, L., & Cortez, N. (2024). Effect of the Addition of Manganese Dioxide Nanoparticles on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete against Carbonation and Sulfate Attack. Buildings, 14, Article 10. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. , Hao, L., He, G., & Yang, C. (2014). Enhanced thermoelectric effect of carbon fiber reinforced cement composites by metallic oxide/cement interface. Ceramics International, 40, 8261–8263. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. , Zhao, L., Zhang, Q., Nie, Z., & Hao, L. (2018). Enhanced thermoelectric properties of cement-based composites with expanded graphite for climate adaptation and large-scale energy harvesting. Energy and Buildings, 159, 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. , Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Miao, Z., Guo, Y., Zhang, H., Li, X., Wang, Z., & Shi, Z. (2023). A large-sized thermoelectric module composed of cement-based composite blocks for pavement energy harvesting and surface temperature reducing. Energy, 265, 126398. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y. , Cui, Y., & Wang, Y. (2023). Ionic thermoelectric effect of pure cement paste and its temperature sensing performance. Construction and Building Materials 364, 129898. [CrossRef]

- Wen, S. , & Chung, D. D. L. (1999). Seebeck effect in carbon fiber-reinforced cement. Cement and Concrete Research, 1993; 29, 1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S. , & Chung, D. D. L. (2000). Seebeck effect in steel fiber reinforced cement. Cement and Concrete Research 30(4), 661–664.

- Wen, S. , & Chung, D. D. L. (2001). Cement-based thermocouples. Cement and Concrete Research, 31, 507–510.

- Wu, C. , Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., & Zeng, Y. (2023). A 7.5-mV Input and 88%-Efficiency Single-Inductor Boost Converter with Self-Startup and MPPT for Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting. Micromachines, 14, Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J. Q. , Yao, W., Qin, J. J., & Cao, H. Y. (2012). Measurements of Thermoelectric Behavior and Microstructure of Carbon Nanotubes/Carbon Fiber-Cement Based Composite. Key Engineering Materials, 492, 242–245. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).