1. Introduction

The field of education has evolved over time. These changes primarily relate to the methods of mediation between the subject matter and the individuals involved in this process. This development opens up a field of research that involves listing variables and themes and examining their relationships. Accordingly, neurosciences are gaining prominence by focusing on aspects of teaching and learning and identifying the most effective practices or strategies for this process [

1]. Consequently, neurosciences can also affect students' motivation, beliefs in academic success, goal-setting, and academic persistence [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Another key construct of interest is self-efficacy, defined as an individual's belief in their own ability to achieve specific goals and complete tasks successfully [

6,

7]. According to Bandura [

8], self-efficacy has four main sources: (a) direct experience—based on one's own experiences; (b) vicarious experience—the ability to learn from others' experiences; (c) social persuasion—when the social environment fosters the perception that an individual has the necessary abilities; and (d) emotional states—which can influence how individuals perceive their ability and competence to address a specific situation.

In education, self-efficacy has been widely studied across various contexts and populations [

9,

10,

11]. Specifically, teachers’ self-efficacy refers to their perception of their capabilities to achieve desired outcomes in student engagement and learning [

12]. This construct profoundly influences teachers’ actions in educational settings, shaping their professional identity, instructional strategies, and assessments of students' learning potential [

13]. Research also indicates that teacher self-efficacy plays a critical role in teaching quality and effectiveness by positively influencing cognitive activation, classroom management, and student support [

14]. Teachers who exhibit higher self-efficacy often perform better in teaching evaluations [

15] and are more inclined to employ effective classroom strategies [

16]. Moreover, robust self-efficacy beliefs correlate with enhanced student outcomes, such as improved academic achievement and engagement [

17]. Because of its importance, promoting teacher self-efficacy through professional development programs can improve teaching effectiveness and foster better student performance [

18].

Several studies have examined how neuroscience training influences teachers' self-efficacy. For instance, a neuroscience program in Liberia enhanced teachers’ self-efficacy, sense of responsibility for student outcomes, and teaching motivation [

19]. In the United States, neuroscience programs designed for middle school science teachers reported increased enthusiasm about teaching among participants [

10]. Programs such as the BrainU workshops [

20] demonstrate that essential neuroscience concepts can be effectively conveyed to educators, positively influencing their professional development and ultimately affecting students’ perceptions of their learning [

10,

21]. Similar investigations have been conducted in Brazil. Lima et al. [

22] explored primary school teachers’ perceptions and knowledge of neuroscience before and after a continuing education course called “Neuroscience’s Course Applied to Education.” Twenty-eight teachers participated, and they unanimously deemed the course highly relevant for acquiring new neuroscience knowledge, agreeing that the concepts learned could improve their teaching practices and environments. Thus, exposure to neuroscience principles appears to positively influence teachers’ perceptions of their performance, capabilities, and professional confidence.

1.1. Current Study

The literature highlights the role of neurosciences in shaping teachers’ self-efficacy, raising questions about how these two domains intersect. A recent study by our group [

23] investigated whether prior neuroscience exposure (categorized as no exposure, extracurricular neuroscience courses, neuroscience-related classes, or both) predicts self-efficacy among undergraduate students. The findings revealed that students with greater neuroscience exposure (i.e., both neuroscience-related classes and extracurricular courses) demonstrated higher self-efficacy. Thus, this study underscores the potential of neuroscience-related content to improve an individual’s confidence in achieving goals, contingent on the relevant context. These results highlight a need for further investigation into whether prior exposure to neuroscience can similarly predict self-efficacy in other populations. If such an association holds among undergraduates regarding their perceived competencies in higher education, our current study questions whether the same relationship exists among teachers. Therefore, we aim to determine whether prior neuroscience exposure can serve as a predictor of teaching self-efficacy in Brazilian Basic Education teachers. In alignment with this objective, our study addresses the following research questions:

Does neuroscience knowledge differ among Brazilian Basic Education teachers based on institution type, educational level, length of teaching experience, and previous neuroscience exposure?

Does teaching self-efficacy vary across institution type, educational level, length of teaching experience, and previous neuroscience exposure in Brazilian Basic Education teachers?

What are the significant predictors of higher teaching self-efficacy among Brazilian Basic Education teachers, considering sociodemographic factors, teaching profiles, and previous neuroscience exposure?

In this regard, we hypothesized that prior exposure to neuroscience (i.e., extracurricular neuroscience courses) is associated with higher levels of teaching self-efficacy, even after accounting for sociodemographic factors and teaching profiles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This observational, cross-sectional study employed a snowball sampling technique. Participants were recruited via digital media platforms and email invitations, with data collected using an online self-report survey (Google Forms) from November 2022 to January 2023. Inclusion criteria were: age between 18 and 59 years, employment as a Brazilian middle or high school teacher, possession of a bachelor’s degree, voluntary consent to participate without compensation, and complete responses to all survey items. A total of 1120 participants met the inclusion criteria. The study: (1) assessed participants’ prior exposure to extracurricular neuroscience courses; (2) evaluated their general neuroscience knowledge through a multiple-choice (true/false) questionnaire; (3) measured teaching self-efficacy using the short version of the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (TSES); and (4) identified demographic and neuroscience-related predictors associated with self-efficacy. The study design followed a similar approach to [

21] in analyzing these variables within this target population.

2.2. Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences, and Letters of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (FFCLRP/USP; CAAE 47436621.3.0000.5407). Participants' personal data were handled following the guidelines of Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD, Law No. 13.709/2018). Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained electronically via the online form. Participants were informed about the study's objectives, potential risks, their rights, and provided with researcher contact information for further inquiries.

2.3. Survey Development

A self-report questionnaire was developed to collect sociodemographic data, including age, gender, ethnicity, and teaching profile information such as educational level (bachelor’s degree, postgraduate certificate, or master’s/doctoral degree). In this study, a bachelor’s degree indicated basic undergraduate qualification, a postgraduate certificate represented specialized training beyond a bachelor's, and master’s/doctoral degrees indicated advanced academic and research training. Additional information collected included length of teaching experience, institution type (public, private, or both), grade levels taught (middle school, high school, or both), and teachers’ fields of knowledge. The fields of knowledge were grouped according to the São Paulo Research Foundation classification [

24] based on participants' bachelor’s degrees, and further categorized into five broad areas to facilitate analysis: (1) Natural Sciences (Biological Sciences, Health Sciences, Exact and Earth Sciences, and Agricultural Sciences), (2) Engineering and Technology, (3) Social Sciences (Applied Social Sciences and Humanities), (4) Arts and Humanities (Linguistics, Literature, and Arts), and (5) Interdisciplinary (fields not fitting other categories).

After completing the sociodemographic questions, participants responded to the neuroscience exposure questionnaire, the general neuroscience knowledge questionnaire, and the TSES. All survey materials were provided in Brazilian Portuguese. A detailed description of these measures is presented below.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Neuroscience Exposure

Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”) with the statements: (1) the dialogue between educators and neuroscientists is important, and (2) scientific knowledge about the brain and its influence on learning is valuable for my teaching practice. Further, participants reported on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “never” to 5 = “very frequently”) how often they: (1) read specialized scientific journals, (2) read popular science magazines, (3) received brain-related information at their workplace (e.g., lectures, workshops), and (4) sought scientific information on the internet [

25,

26]. Prior neuroscience exposure was also quantified by participants’ reported attendance at extracurricular neuroscience courses, categorized as no exposure, 1–3 courses, or 4 or more courses.

2.4.2. General neuroscience knowledge

General neuroscience knowledge was assessed using a questionnaire comprising 17 true/false statements about the brain, selected from previous studies [

25,

26] and previously adapted for Brazilian populations [

23,

27,

28,

29].

2.4.3. Teachers' Self-Efficacy Survey

Teachers' self-efficacy was evaluated using the short version of the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (TSES) [

12], previously adapted for the Brazilian context [

13]. This scale consists of 12 items divided into three dimensions (4 items each): (1) efficacy in student engagement, reflecting teachers' perceptions of their ability to motivate and engage students; (2) efficacy in instructional strategies, reflecting confidence in selecting, adapting, and implementing teaching and evaluation strategies; and (3) efficacy in classroom management, addressing teachers’ confidence in managing classroom behavior and effectively supervising students. The TSES uses a 10-point rating scale (0 = “nothing” to 10 = “a great deal”) and has demonstrated high validity and reliability [

13].

2.5. Variable Selection

Variables for inferential analysis were selected based on their relevance to understanding teaching self-efficacy in Brazilian basic education. Sociodemographic factors, including gender and age, were selected due to their established influence on teachers’ experiences and self-efficacy [

30,

31]. Teaching profile variables, including educational level, length of teaching experience, institution type, and prior neuroscience exposure, were chosen based on previously established or hypothesized relationships with teaching performance outcomes [

10,

15,

32].

Furthermore, in Brazil, public and private basic education institutions differ considerably in resources, infrastructure, and academic performance. Private schools often offer better facilities and greater operational efficiency, frequently leading to higher student achievement. Conversely, public schools face resource limitations and administrative challenges despite their foundational principles of equity and universal education [

33,

34].

Thus, these variables were selected to capture specific characteristics of the Brazilian educational system, allowing for meaningful comparisons and insights into how neuroscience knowledge and self-efficacy relate to teaching and demographic factors across diverse educational contexts.

2.6. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using Just Another Statistics Program (JASP 0.19.1.0). Data normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Internal consistency reliability of the TSES was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha (α). Homogeneity of variances was verified through Levene’s test before conducting analysis of variance (ANOVA). The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Descriptive statistics summarized sociodemographic characteristics, teaching profiles, previous neuroscience exposure, general neuroscience knowledge, and TSES results. One-way ANOVA compared TSES scores and general neuroscience knowledge performance across educational level, length of teaching experience, institution type, and neuroscience exposure levels (no exposure, 1–3 courses, and 4 or more extracurricular neuroscience courses). Effect sizes were calculated using eta squared (

η²), interpreted as small (0.01), medium (0.06), or large (0.14) [

35]. Post-hoc Tukey tests identified specific group differences. Cohen’s d assessed post-hoc effect sizes, with 0.20 indicating small, 0.50 medium, and 0.80 large effects [

35].

Three separate multiple linear regression analyses were conducted, one for each dimension of the TSES (instructional strategies, classroom management, and student engagement), to identify the predictive effects of neuroscience exposure, length of teaching experience, educational level, gender, and age on teacher self-efficacy. Linear model assumptions were assessed using residual and Q-Q plots. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at p < 0.05 unless stated otherwise. For certain multiple comparisons, statistical values are expressed as ranges. Levels of significance are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Teaching Profile

The total sample consisted of 1120 participants, with ages ranging from 21 to 59 years (M = 40.99, SD = 8.89). The gender distribution indicated that 72.41% were women and 27.59% were men. The mean age for women was 41.08 years (SD = 8.70), and for men, 40.77 years (SD = 9.39).

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and teaching profile of the sample.

3.2. Previous Neuroscience Exposure and General Knowledge

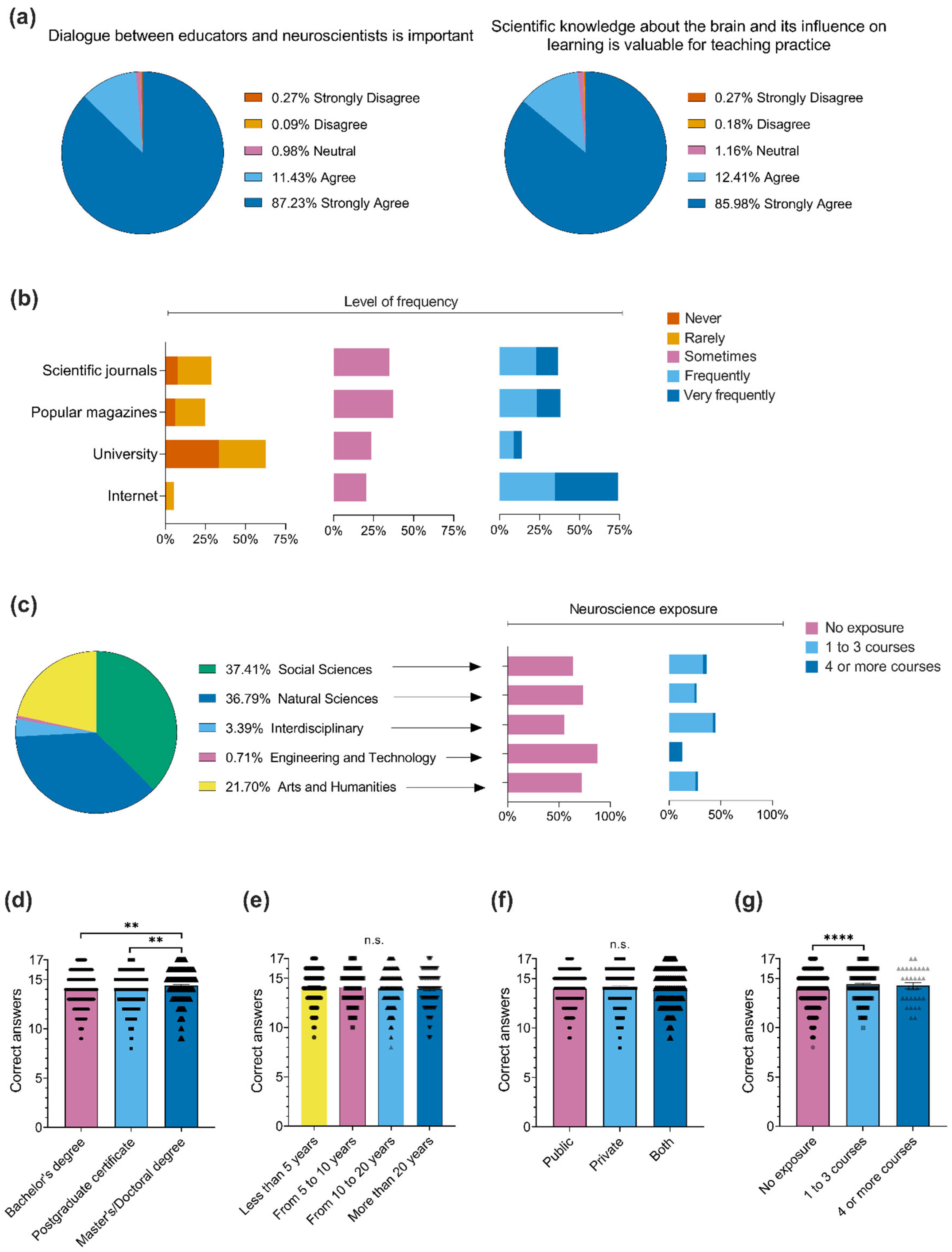

Regarding previous exposure to neuroscience extracurricular courses, 68.93% (n = 772) had not taken any, 28.30% (n = 317) had taken one to three courses, and 2.77% (n = 31) had taken four or more. With respect to participants' opinions on the relevance of neuroscience (

Figure 1a), 98.66% (n = 1105) either agreed or strongly agreed that dialogue between educators and neuroscientists is important. Furthermore, 98.39% (n = 1102) agreed or strongly agreed that scientific knowledge about the brain and its influence on learning is valuable for their teaching practice. Regarding prior exposure to scientific and neuroscientific knowledge (

Figure 1b), a considerable number of participants had never or rarely looked for information in scientific journals (28.57%, n = 320), in popular magazines (24.82%, n = 278), or received any brain-related information at their workplace (e.g., lectures, workshops) (62.50%, n = 700). However, most participants often or very frequently seek scientific information on the internet (62.70%, n = 702).

In terms of the distribution of participants across different fields of knowledge (

Figure 1c), 37.41% (n = 419) were in Social Sciences, 36.79% (n = 412) in Natural Sciences, 21.70% (n = 243) in Arts and Humanities, 3.39% (n = 38) in Interdisciplinary, and 0.71% (n = 8) in Engineering and Technology. Participants from the Interdisciplinary (44.74%, n = 17) and Social Sciences (36.52%, n = 153) fields reported the highest exposure to neuroscience (i.e., at least one extracurricular course).

Across the general neuroscience knowledge questionnaire, the average percentage of incorrect responses was 17.42%. Notably, items concerning the entry of substances into the nervous system, brain region functions, and brain learning had the highest error rates (

Table 2). Regarding participants’ performance on the neuroscience questionnaire, there were significant differences in performance based on educational level (

F(2,1117) = 6.26,

p = 0.002,

η² = 0.01,

Figure 1d). Specifically, participants with a master’s/doctoral degree scored significantly higher than those with a postgraduate certificate (

p = 0.003,

d = 0.27) and a bachelor's degree (

p = 0.005,

d = 0.26). However, there was consistent regardless of length of teaching experience (

F(3,1116) = 1.27,

p = 0.34,

η² = 0.003,

Figure 1e) and type of school institution (

F(2,1117) = 1.74,

p = 0.18,

η² = 0.002,

Figure 1f). Additionally, there were significant differences in performance across neuroscience exposure levels (

F(2,1117) = 10.81,

p < 0.001,

η² = 0.02,

Figure 1g). Participants who attended 1 to 3 courses scored significantly higher than those with no exposure (

p < 0.0001,

d = 0.36). Overall, these data suggest that while length of teaching experience does not significantly influence participants' general neuroscience knowledge, differences emerge based on educational levels and varying levels of neuroscience exposure.

3.3. Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Previous Neuroscience Exposure

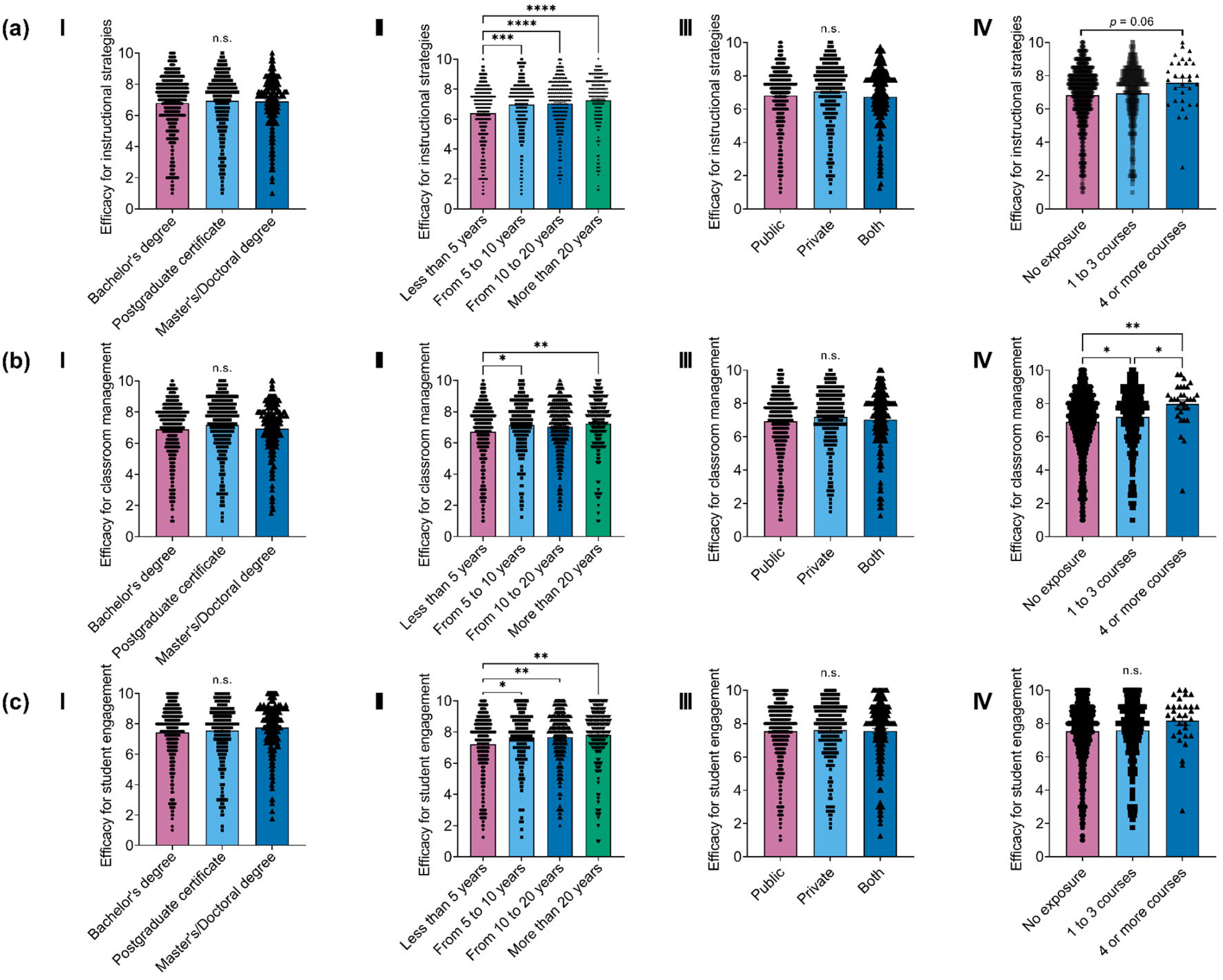

The TSES scores were analyzed across three dimensions. The results showed that efficacy for instructional strategies had the highest mean (M = 7.57, SD = 1.79) with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94). Efficacy for student engagement was intermediate (M = 7.02, SD = 1.78), also with strong internal consistency (α = 0.91). In contrast, efficacy for classroom management had the lowest mean (M = 6.88, SD = 1.80), though it still demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.93). This high reliability suggests that items within each dimension are internally consistent, supporting the scale's validity and reliability. The results of the comparisons in the three TSES dimensions are presented in

Figure 2.

Participants’ efficacy for instructional strategies did not significantly differ by educational level (

F(2,1117) = 0.61,

p = 0.54,

η² = 0.001,

Figure 2a-I) or type of school institution (

F(2,1117) = 2.58,

p = 0.08,

η² = 0.005,

Figure 2a-III). However, it was higher in individuals with longer teaching experience (

F(3,1116) = 11.95,

p < 0.001,

η² = 0.03,

Figure 2a-II) and those with previous neuroscience exposure (

F(2,1117) = 2.96,

p = 0.05,

η² = 0.005,

Figure 2a-IV). Specifically, participants with more than 20 years of experience (

p < 0.0001,

d = 0.49), 10 to 20 years (

p < 0.0001,

d = 0.37), and 5 to 10 years (

p < 0.001,

d = 0.32) reported significantly higher efficacy for instructional strategies than those with fewer than 5 years. Additionally, those who had attended four or more extracurricular neuroscience courses had marginally higher scores than those with no previous neuroscience exposure (

p = 0.06,

d = 0.42).

Regarding participants’ efficacy for classroom management, it was also consistent across educational level (

F(2,1117) = 2.79,

p = 0.06,

η² = 0.005,

Figure 2b-I) and type of school institution (

F(2,1117) = 2.41,

p = 0.09,

η² = 0.004,

Figure 2b-III), but was higher among individuals with longer teaching experience (

F(3,1116) = 4.72,

p = 0.003,

η² = 0.01,

Figure 2b-II) and previous neuroscience exposure (

F(2,1117) = 7.50,

p < 0.001,

η² = 0.01,

Figure 2b-IV). Participants with more than 20 years of experience (

p < 0.01,

d = 0.30) and 5 to 10 years (

p = 0.02,

d = 0.25) reported significantly higher efficacy for classroom management than those with fewer than 5 years. Moreover, those who had attended one to three (

p = 0.05,

d = 0.16) and four or more (

p < 0.01, d = 0.60) extracurricular neuroscience courses had significantly higher efficacy than participants with no neuroscience exposure. Notably, participants with four or more courses also had higher scores than those with one to three (

p = 0.05,

d = 0.45).

With respect to participants’ efficacy for student engagement, it was consistent across educational level (

F(2,1117) = 2.41,

p = 0.09,

η² = 0.004,

Figure 2c-I), type of school institution (

F(2,1117) = 0.14,

p = 0.87,

η² = 0.0003,

Figure 2c-III), and previous neuroscience exposure (

F(2,1117) = 1.91,

p = 0.15,

η² = 0.003,

Figure 2c-IV). However, it was higher in individuals with longer teaching experience (

F(3,1116) = 6.30,

p < 0.001,

η² = 0.02,

Figure 2c-II). Participants with more than 20 years of experience (

p < 0.001,

d = 0.34), 10 to 20 years (

p = 0.004,

d = 0.26), and 5 to 10 years (

p = 0.01,

d = 0.26) reported significantly higher efficacy for student engagement than those with fewer than 5 years.

3.4. Analysis of Predictors for Teachers' Self-Efficacy

Multiple linear regression models were constructed to examine predictors of the three dimensions of the TSES. Each model was progressively expanded by incorporating additional control variables to evaluate their impact on efficacy for instructional strategies (

Table 3), classroom management (

Table 4), and student engagement (

Table 5). For all three dimensions, Model 1 included educational level, length of teaching experience, type of school institution, and neuroscience exposure as predictors. Model 2 introduced gender, while Model 3 added age as a control variable.

3.4.1. Efficacy for Instructional Strategies

In Model 1 (Adjusted R² = 0.03, F(7,1112) = 6.33, p < 0.001), longer teaching experience emerged as a positive predictor of efficacy for instructional strategies (B = 0.29, p < 0.001). Conversely, working in a public school (B = -0.29, p = 0.02) or in both public and private institutions (B = -0.38, p = 0.02) was associated with lower self-efficacy. Additionally, higher levels of neuroscience exposure (i.e., 4 or more extracurricular courses) also predicted increased self-efficacy (B = 0.71, p = 0.03).

In Model 2 (Adjusted R² = 0.04, F(8,1111) = 6.05, p < 0.001), gender (i.e., men) was a significant positive predictor (B = 0.24, p = 0.05). The overall findings remained similar: teaching experience (B = 0.30, p < 0.001) and neuroscience exposure (B = 0.73, p = 0.03) continued to be significant positive predictors of efficacy for instructional strategies, while working in a public school (B = -0.30, p = 0.02) or both public and private institutions (B = -0.41, p = 0.01) remained negative predictors.

In Model 3 (Adjusted R² = 0.03, F(9,1110) = 5.37, p < 0.001), age did not significantly predict efficacy for instructional strategies (B = 0.001, p = 0.91). The significance of the other predictors remained stable, with teaching experience (B = 0.29, p < 0.001) and neuroscience exposure (B = 0.73, p = 0.03) continuing to have a positive effect, while working in a public school (B = -0.30, p = 0.02) or both public and private institutions (B = -0.41, p = 0.01) remained negative predictors. Additionally, gender (men) retained its significance (B = 0.24, p = 0.05), reinforcing the trend observed in Model 2.

3.4.2. Efficacy for Classroom Management

For efficacy in classroom management, Model 1 (Adjusted R² = 0.02, F(7,1112) = 4.61, p < 0.001) showed that length of teaching experience was a positive predictor (B = 0.15, p < 0.01). Education level did not show significant effects, while working in public schools (B = −0.28, p = 0.02) had a negative impact on self-efficacy. The number of neuroscience courses attended was significant for participants who completed one to three (B = 0.24, p = 0.04), and four or more courses (B = 1.01, p < 0.01).

In Model 2 (Adjusted R² = 0.02, F(8,1111) = 4.10, p < 0.001), adding gender did not result in a significant effect (B = 0.09, p = 0.47). Length of teaching of experience (B = 0.15, p < 0.01), participation in one to three (B = 0.24, p = 0.04) and four or more neuroscience courses (B = 1.01, p < 0.01), and working in public schools (B = −0.28, p = 0.02) remained significant predictors.

Finally, in Model 3 (Adjusted R² = 0.02, F(9,1110) = 4.04, p < 0.001), the inclusion of age as a control variable reduced the significance of teaching experience (B = 0.09, p = 0.12), suggesting that age may account for part of the effect previously attributed to experience. However, working in public schools (B = −0.29, p = 0.02), and participation in one to three (B = 0.25, p = 0.03) and four or more neuroscience courses (B = 1.01, p < 0.01) remained significant predictors.

3.4.3. Efficacy for Student Engagement

In Model 1 (Adjusted R² = 0.01, F(7,1112) = 3.04, p < 0.01), length of experience was a significant predictor of the efficacy for student engagement (B = 0.18, p < 0.001). Educational level did not have a significant effect, and working in public (B = −0.09, p = 0.45) or both types of school institutions (B = −0.09, p = 0.57) did not influence this dimension. Additionally, completing four or more courses had only a marginally significant effect (B = 0.58, p = 0.08).

In Model 2 (Adjusted R² = 0.01, F(8,1111) = 2.97, p < 0.01), gender (men) was not significant for self-efficacy in student engagement (B = 0.18, p = 0.12). Length of experience remained a significant predictor (B = 0.19, p < 0.001), while the effect of completing four or more neuroscience courses remained marginally significant (B = 0.59, p = 0.07).

Finally, in Model 3 (Adjusted R² = 0.01, F(9,1110) = 2.71, p < 0.01), adding age did not alter the significance of teaching experience (B = 0.21, p < 0.001) or the marginal effect of greater neuroscience exposure (B = 0.59, p = 0.07). However, age itself was not a significant predictor of self-efficacy for student engagement (B = −0.01, p = 0.42).

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether prior exposure to neuroscience predicts teaching self-efficacy among Brazilian Basic Education teachers. Specifically, this study sought to answer three primary research questions: (1) does neuroscience knowledge differ among Brazilian Basic Education teachers based on institution type, educational level, length of teaching experience, and previous neuroscience exposure? (2) Does teaching self-efficacy vary across institution type, educational level, length of teaching experience, and previous neuroscience exposure in Brazilian Basic Education teachers? (3) What are the significant predictors of higher teaching self-efficacy among Brazilian Basic Education teachers, considering sociodemographic factors, teaching profiles, and previous neuroscience exposure? Based on these questions, it has been hypothesized that prior exposure to neuroscience is associated with higher levels of teaching self-efficacy.

Our findings confirmed this hypothesis and provided the following answers to the research questions: (1) Neuroscience knowledge levels did not differ significantly by institution type or teaching experience. However, teachers with higher educational levels (master’s/doctoral degrees) and those with some exposure to extracurricular neuroscience courses (one to three courses) scored significantly better. This suggests that advanced academic training and direct engagement with neuroscience courses contribute to a deeper understanding and improved retention of neuroscience knowledge. (2) Self-efficacy did not differ significantly by institution type or educational level but was notably higher in teachers with more teaching experience across all three TSES dimensions. Moreover, instructors exposed to extracurricular neuroscience courses showed significantly higher efficacy in instructional strategies and classroom management. These findings highlight the roles of professional experience and neuroscience education in enhancing teachers’ confidence in their abilities. (3) Teaching experience emerged as a significant predictor in all three TSES dimensions. For instructional strategies and classroom management, attendance at multiple extracurricular neuroscience courses corresponded to higher self-efficacy, whereas teaching in public institutions was consistently associated with lower self-efficacy. Additionally, male teachers reported slightly higher self-efficacy in instructional strategies, while age did not significantly affect any dimension. These results underscore the influence of professional experience, neuroscience education, and institutional context on teachers’ confidence and expand our previous data among undergraduate students which showed that previous exposure to neuroscience was also associated with higher levels of self-efficacy [

23]. Even more, previous neuroscience exposure was a significant predictor of enhanced self-efficacy in this group. The discussion focuses on the contributions of neuroscience education to enhancing teaching self-efficacy.

4.1. Previous Neuroscience Exposure

In our sample, nearly 70% of participants reported no prior exposure to extracurricular neuroscience courses. This finding suggests that, despite the availability of such courses in Brazil [

22], many Brazilian primary school teachers have not pursued them—possibly due to limited access, institutional constraints, or the absence of supportive public policies [

29]. Nonetheless, almost the entire sample recognized the importance of dialogue between educators and neuroscientists and valued scientific knowledge about the brain and its influence on learning. This discrepancy between teachers’ positive perceptions of neuroscience and their low enrollment in relevant courses signals a clear need for increased training opportunities.

Another notable outcome is that teachers with higher educational levels (master’s/doctoral degrees) and previous neuroscience course exposure scored better on the general neuroscience knowledge questionnaire, mirroring results from prior research [

26]. This aligns with the view that advanced academic training and direct engagement with neuroscience topics are critical for acquiring and retaining accurate knowledge. Consequently, incorporating neuroscience into both initial and continuing teacher training programs is vital, especially in Brazil, where educators’ neuroscience awareness remains limited [

29].

Together, these findings reinforce the urgency of improving communication between neuroscientists and educators. Inaccurate beliefs about the brain, known as

neuromyths, remain widespread and can negatively affect teaching practices [

28,

29]. Previous studies [

36,

37] have shown that educators often hold misconceptions about how the brain functions. While debunking these myths is important, a broader emphasis on accurate neuroscience knowledge can be more effective. Well-structured neuroscience education initiatives are essential to promote evidence-based teaching and bridge the gap between neuroscience and educational practice.

4.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy

Our results indicate that teacher self-efficacy was significantly influenced by professional experience and exposure to extracurricular neuroscience courses. Teachers with longer careers reported higher levels of self-efficacy in student engagement, instructional strategies, and classroom management, consistent with Bandura’s [

6,

7] emphasis on direct experience as a primary source of self-efficacy. Notably, having a higher educational level (e.g., a postgraduate certificate or master’s/doctoral degree) did not yield significantly different self-efficacy scores compared with lower educational levels, possibly because advanced degrees do not necessarily translate into more direct teaching experience [

38].

Moreover, exposure to neuroscience courses significantly predicted teacher self-efficacy, particularly for classroom management and instructional strategies. These findings resonate with previous studies [

10,

19,

20,

21] suggesting that familiarity with neuroscientific concepts fosters teachers’ motivation and sense of responsibility for student outcomes. The impact of neuroscience exposure was especially pronounced among more experienced teachers, who may be better equipped to integrate new knowledge into their existing pedagogical framework. Less experienced teachers, however, may struggle to apply neuroscientific concepts without adequate institutional support, underscoring the need for well-structured policies and professional development programs—particularly relevant in Brazil, where neuroscience literacy among educators remains limited [

29].

Another relevant finding is that teachers in public institutions reported lower self-efficacy in instructional strategies and classroom management compared to their counterparts in private institutions. These results reflect the structural and resource disparities between public and private schools in Brazil, where public institutions often face challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, excessive workloads, and administrative constraints [

33,

34]. Such factors may undermine teachers' confidence in their ability to implement effective pedagogical practices, regardless of their training or exposure to neuroscience.

Finally, men teachers reported slightly higher self-efficacy in instructional strategies than women teachers, mirroring research on gender differences in teacher self-efficacy [

30,

31]. Cultural and educational backgrounds may contribute to these differences, as observed in science teaching, where men teachers generally report greater personal self-efficacy [

39]. However, factors such as heavier workloads and elevated job stress, which often affect women teachers, can also influence self-efficacy levels [

40]. These findings underscore the need for professional development programs that provide equitable support to both men and women educators.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its large sample (n = 1120) of Brazilian Basic Education teachers, enhancing the representativeness of our findings and permitting nuanced analyses across various institutional contexts, educational levels, and demographic profiles. Our use of the well-validated TSES further bolsters confidence in the reliability of our measures. Additionally, the combination of descriptive analyses, group comparisons, and multiple linear regression models yielded a comprehensive investigation of the predictors of teacher self-efficacy, building on earlier work that emphasizes self-efficacy as a mediator of professional performance.

Despite identifying significant predictors of teaching self-efficacy, this study has several limitations. First, the low Adjusted R² values (0.01–0.04) indicate that the independent variables explain only a small proportion of variance in self-efficacy, implying that additional unmeasured factors—such as school environment, institutional policies, peer support, personality traits, and prior teaching experiences—may also shape teachers’ perceptions of their capabilities. Second, the use of snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias, as participants with an existing interest in neuroscience or education-related topics could be overrepresented, limiting the generalizability of these findings to the broader population of Brazilian teachers. Third, this study relied on self-reported data for both previous neuroscience exposure and teacher self-efficacy, which may be subject to social desirability or recall biases. Fourth, the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inferences regarding whether neuroscience exposure directly enhances self-efficacy or whether teachers with higher self-efficacy are more inclined to seek neuroscience-related knowledge. Fifth, professional performance was not directly assessed, although it is a crucial outcome potentially influenced by self-efficacy. In the Brazilian context, variations in evaluation methods across different teaching institutions and educational levels pose additional challenges to such assessments. Finally, our sample was limited to Brazilian middle and high school teachers, which may affect the generalizability of the results to other cultural, institutional, or educational contexts.

Nonetheless, this study contributes valuable insights into the importance of continuing education in neuroscience for teachers. By reinforcing the connection between neuroscience exposure and higher levels of self-efficacy, it supports targeted educational interventions aimed at strengthening teaching confidence and effectiveness. Future longitudinal studies should incorporate standardized measures of classroom performance and consider additional contextual or psychological variables, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of how neuroscience education influences teacher development over time.

4.4. Implications for Practice

These findings have significant implications for educational practice, particularly regarding teacher training. Integrating neuroscience into both initial and continuing education programs appears to deepen teachers’ knowledge and enhance their confidence and competence in the classroom. Such programs can tackle common neuromyths and offer practical strategies rooted in evidence-based neuroscience. They can also be tailored to meet the specific needs of different educational contexts, including public and private schools, where resource gaps may influence teacher self-efficacy.

Equally important is the need for public policies that promote equitable access to neuroscience-oriented professional development, particularly in public institutions where teachers reported lower self-efficacy. Providing infrastructure, mentorship, and institutional support can help mitigate the disparities observed in this study. Future research should further examine the effects of specific neuroscience training programs through longitudinal designs, investigating both teacher self-efficacy and student learning outcomes. It would also be valuable to explore how different training formats influence teachers’ retention and application of neuroscientific knowledge. Additionally, qualitative methods could provide deeper insights into teachers’ experiences as they integrate neuroscientific knowledge into real-world classroom settings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a robust relationship between prior neuroscience exposure and teaching self-efficacy among Brazilian Basic Education teachers. Both professional experience and extracurricular neuroscience courses emerged as key predictors of higher self-efficacy, indicating that continued professional development in neuroscience can improve teachers’ pedagogical confidence and competence. Teachers with advanced educational levels and multiple neuroscience courses also showed better knowledge retention and reported greater efficacy in their instructional practices. These findings underscore the critical role of sustained, evidence-based professional development in supporting effective teaching and maximizing student outcomes.

Author Contributions

Ana Julia Ribeiro: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rafael Lima Dalle Mulle: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing — original draft, Writing — review & editing. Fernando Eduardo Padovan-Neto: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

This research was supported by a scholarship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (146008/2023-5), as well as a scholarship from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (2023/09339-2) awarded to Ana Julia Ribeiro.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences, and Letters of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (FFCLRP/USP; CAAE 47436621.3.0000.5407).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Open Science Framework (OSF) at http://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X9N5J.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research team, the Department of Psychology, the Academic Excellence Program (PROEX) and Culture and Extension Committees (CCEx) of Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters of Ribeirão Preto, from University of São Paulo (USP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gkintoni, E.; Dimakos, I.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Antonopoulou, H. Contributions of Neuroscience to Educational Praxis: A Systematic Review. Emerging Science Journal 2023, 7, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, L.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S. Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement across an Adolescent Transition: A Longitudinal Study and an Intervention. Child Development 2007, 78, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, H.S.; Moran, T.P.; Donnellan, M.B.; Moser, J.S. Mindset Induction Effects on Cognitive Control: A Neurobehavioral Investigation. Biological Psychology 2014, 103, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mindsets That Promote Resilience: When Students Believe That Personal Characteristics Can Be Developed. Educational Psychologist 2012, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Hanselman, P.; Walton, G.M.; Murray, J.S.; Crosnoe, R.; Muller, C.; Tipton, E.; Schneider, B.; Hulleman, C.S.; Hinojosa, C.P.; et al. A National Experiment Reveals Where a Growth Mindset Improves Achievement. Nature 2019, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman: New York, 1997; ISBN 9780716728504. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency: Pathways and Reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2018, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artino, A.R. Academic Self-Efficacy: From Educational Theory to Instructional Practice. Perspectives on Medical Education 2012, 1, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNabb, C.; Schmitt, L.; Michlin, M.; Harris, I.; Thomas, L.; Chittendon, D.; Ebner, T.J.; Dubinsky, J.M. Neuroscience in Middle Schools: A Professional Development and Resource Program That Models Inquiry-Based Strategies and Engages Teachers in Classroom Implementation. CBE—Life Sciences Education 2006, 5, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jederlund, U.; von Rosen, T. Teacher–Student Relationships and Students’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs. Rationale, Validation and Further Potential of Two Instruments. Education Inquiry 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher Efficacy: Capturing an Elusive Construct. Teaching and Teacher Education 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, D.C.G.; Azzi, R.G. Personal and Collective Efficacy Beliefs Scales to Educators: Evidences of Validity. Psico-USF 2015, 20, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I. ; Krešimir Jakšić; Balaž, B. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Teaching Quality: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Investigation. International Journal of Psychology 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M.; Tze, V.M.C. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy, Personality, and Teaching Effectiveness: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Research Review 2014, 12, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M.S.; Reddy, L.A.; Dudek, C.M. Relation of Teacher Self-Efficacy and Classroom Practices: A Preliminary Investigation. School Psychology International 2019, 40, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.N.; John, J.E. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs for Teaching Math: Relations with Teacher and Student Outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2020, 61, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.N.; Calkins, C.; Part, R. Teacher Self-Efficacy Profiles: Determinants, Outcomes, and Generalizability across Teaching Level. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2019, 58, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, K.; Cooper, J.L.; Mason, L.; Faeflen, S.; Monmia, J.; Dubinsky, J.M. Tiered Neuroscience and Mental Health Professional Development in Liberia Improves Teacher Self-Efficacy, Self-Responsibility, and Motivation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, J.M.; Guzey, S.S.; Schwartz, M.S.; Roehrig, G.; MacNabb, C.; Schmied, A.; Hinesley, V.; Hoelscher, M.; Michlin, M.; Schmitt, L.; et al. Contributions of Neuroscience Knowledge to Teachers and Their Practice. The Neuroscientist 2019, 25, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, J.M.; Roehrig, G.; Varma, S. Infusing Neuroscience into Teacher Professional Development. Educational Researcher 2013, 42, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.R.; Lopes, L.F.; Marks, N.; Franco, R.M.; Maria, E.; Mello-Carpes, P.B. Formação Continuada Em Neurociência: Percepções de Professores Da Educação Básica. Revista Brasileira de Extensão Universitária 2020, 11, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.J.; Ruggiero, R.N.; Padovan-Neto, F.E. Previous Neuroscience Exposure Predicts Self-Efficacy among Undergraduate Students. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2025, 38, 100251–100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAPESP Tabela de Áreas. Available online: https://fapesp.br/2000/tabela-de-areas.

- Dekker, S.; Lee, N.C.; Howard-Jones, P.; Jolles, J. Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence and Predictors of Misconceptions among Teachers. Frontiers in Psychology 2012, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, K.; Germine, L.; Anderson, A.; Christodoulou, J.; McGrath, L.M. Dispelling the Myth: Training in Education or Neuroscience Decreases but Does Not Eliminate Beliefs in Neuromyths. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonchoroski, T. Neurociências Na Educação: Conhecimento E Opiniões de Professores. Trabalho de conclusão de curso, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2014.

- Herculano-Houzel, S. Do You Know Your Brain? A Survey on Public Neuroscience Literacy at the Closing of the Decade of the Brain. The Neuroscientist 2002, 8, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoes, E.; Foz, A.; Petinati, F.; Marques, A.; Sato, J.; Lepski, G.; Arévalo, A. Neuroscience Knowledge and Endorsement of Neuromyths among Educators: What Is the Scenario in Brazil? Brain Sciences 2022, 12, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hadi, S. Interpersonal Self Efficacy among Teachers in Light of Two Variables: Gender (Male/Female) and Years of Experience. Psychology and Education Journal 2020, 57, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, R. Comparison of Self-Efficacy between Male and Female Pre-Service Early Childhood Teachers. Early Child Development and Care 2015, 185, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, J.; McGhie-Richmond, D.; Loreman, T.; Mirenda, P.; Bennett, S.; Gallagher, T.; Young, G.; Metsala, J.; Aylward, L.; Katz, J.; et al. Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms: Efficacy and Beliefs of Canadian Preservice Teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2015, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, B.; Guimarães, J. Diferenças de Eficiência Entre Ensino Público E Privado No Brasil. Economia Aplicada 2009, 13, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.R. ; Maria Habilidades Cognitivas de Escolares Do Ensino Público E Privado: Estudo Comparativo de Pré-Competências Para a Aprendizagem Acadêmica. Revista Psicopedagogia 2017, 34, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 9780805802832. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, J.A.; Childers, G.; Dawson, B.L. A Rationale for Promoting Cognitive Science in Teacher Education: Deconstructing Prevailing Learning Myths and Advancing Research-Based Practices. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2023, 33, 100209–100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, J.I.; Alami, M.; Abdelaziz, L.; Souirti, Z. Brain Knowledge and Predictors of Neuromyths among Teachers in Morocco. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2020, 20, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmers, E.; Baeyens, D.; Petry, K. Attitudes and Self-Efficacy of Teachers towards Inclusion in Higher Education. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2019, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviet, A.M.; Mji, A. Sex Differences in Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Elementary Science Teachers. Psychological Reports 2003, 92, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M.; Chiu, M.M. Effects on Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job Stress. Journal of Educational Psychology 2010, 102, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).