Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The need for early diagnosis of diseases, especially severe and rare diseases, has increased the demand for developing better biosensors for diagnosis. These tools can diagnose diseases at their early stage and sometimes even before the onset of symptoms. This review is focused on the analysis of the methods of biosensor creation and their application for early disease diagnosis. This review includes various categories of biosensors, including nanomaterials, aptamers, and peptides. The focus is on developing these sensors and employing the right materials. Different fabrication techniques are presented, including thin-film deposition, lithography, printing, and microfluidics, due to their merits and disadvantages. This review also examines the effectiveness of these biosensors in clinical practice and various laboratory tests. We also focus on enhancing performance and sensitivity when nanomaterials and nanotechnology are employed. Additionally, we discuss scalability, reproducibility, and suggest ways to overcome these issues. We also describe current and emerging developments in advanced biosensors, including point-of-care and biosensor fusion systems. This review will be helpful for scholars, practitioners, and decision-makers because it concentrates on biosensor design and implementation technology.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

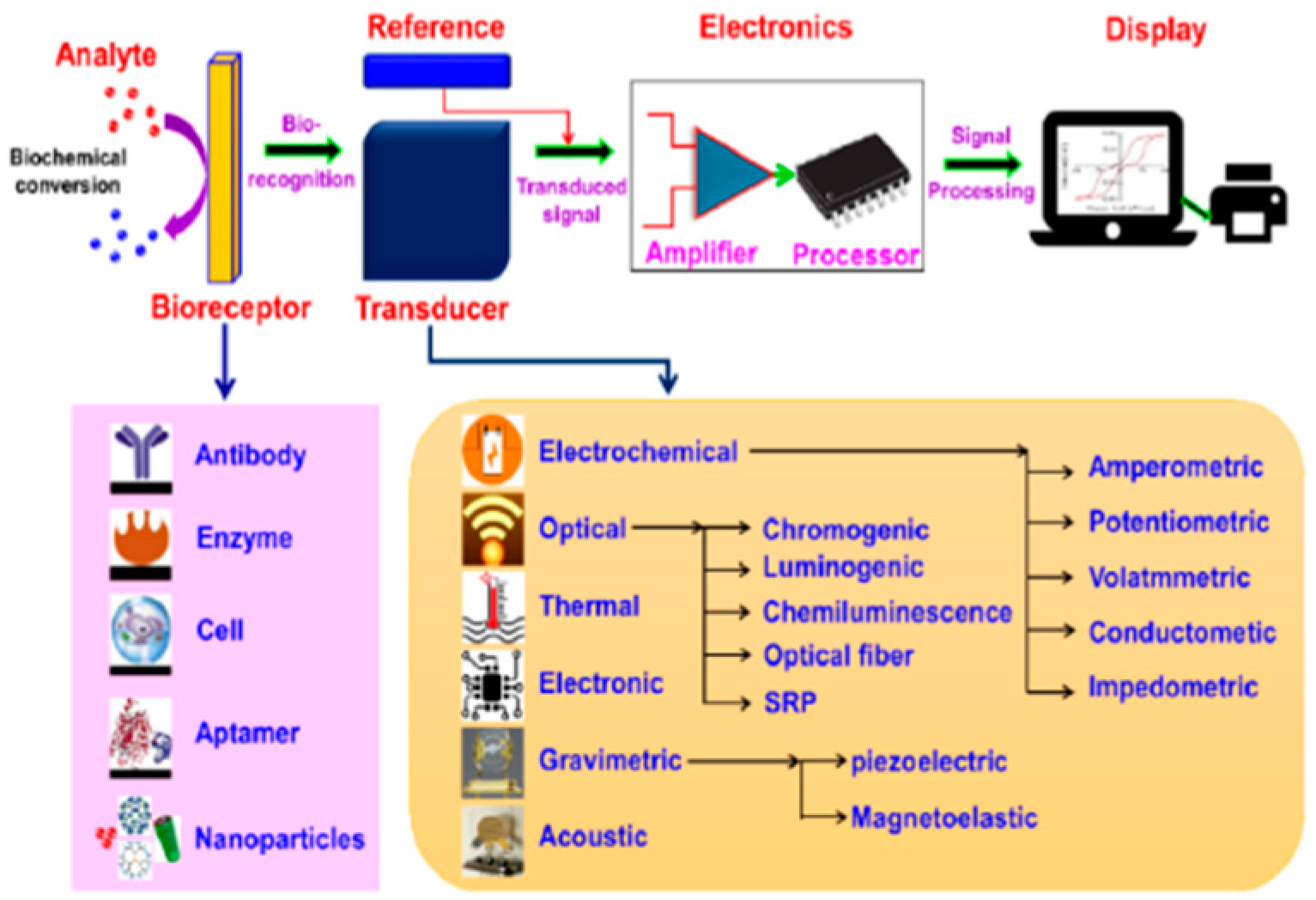

2. Biosensor Overview

2.1. Components Used in Biosensors

2.1.1. Biological Recognition Elements

2.1.2. Transducer

2.1.3. Signal Processing System

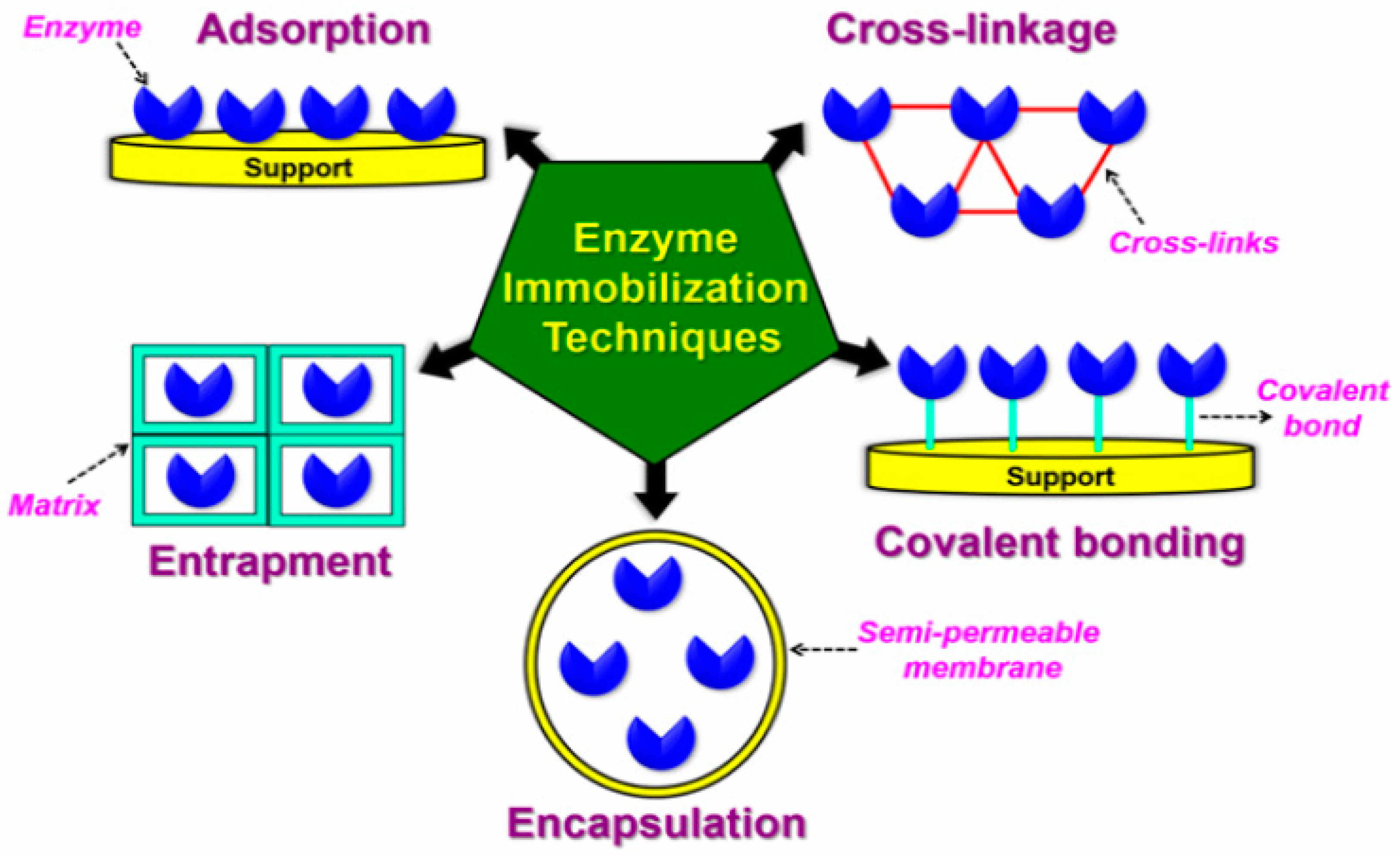

2.2. Method of Surface Modification

|

Biosensor |

Surface Modification Technique |

Immobilization Technique |

Working Principle of BS |

Reference |

| Aptamer | Biomolecule Immobilization | Physical Adsorption | Fluorescence proportional to AFP concentration | [53] |

| Electrochemical | Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) | Molecular Imprinting | Measures changes in sensing electrode potential | [54] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification- Spacer Deposition: Introduction of Cross-Linkers |

Cross Linking | Electro kinetics-assisted molecular trapping | [55] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification (CSPE-COOH-AuNPs)-Amino Coupling Protocol. Chemical Modification (CSPE-AuNPs-SAM)-SAM Formation |

CSPE-COOH-AuNPs: Covalent Bonding; CSPE-AuNPs-SAM: Covalent Bonding | Electrochemical signals from anti-CRP and CRP interaction | [56] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification- Functionalization: GDY (Graphdiyne); Antifouling: with PEG (Polyethylene Glycol). |

Physical Entrapment | Signals from biomarker binding to imprinted polymer sites | [1] |

| Electrochemical | Physical Adsorption- Use of gold (Au) nanowires grown on a Poly Carbonate (PC) substrate | Adsorption | CRP binding to anti-CRP enhances immunosensor signal | [57] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification- Salinization: Assembly of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) on the surface of ITO using a hydrolyzed polymer of (3-aminopropyl) trimethoxy silane (APTMS). |

Adsorption | Electrochemical luminescence of luminol for C-peptide detection | [58] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification: Assembly of Nafion solution soaked Ru(II)-organic complex (Ru-PEI-ABEI) onto the electrode surface. | Covalent Bond | C-peptide detection via DNA and dopamine quenching ECL signal | [59] |

| Electrochemical | Plasma Treatment- Oxygen Plasma Cleaning; Chemical Modification- Salinization with APTES(3-Aminopropyl-triethoxysilane); Functionalization: Glutaraldehyde (Glu) Modification |

Covalent Bond | Binding alters surface charge and conductance | [60] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification-Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Coating Deposition- Physical deposition: Deposition of Gold Nanoparticles Chemical Modification-Functionalization: With Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) |

Covalent Bond | Reduction current on gold electrode proportional to antibody concentration | [61] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification – Functionalization: Cysteamine was utilized to create a self-assembled monolayer of alkyl amine groups |

Covalent Bond | SWV reduction peak current change with antibody/antigen binding | [62] |

| Electrochemical | Electrochemical Activation- Involved cycling the potential from -0.200V to 1.20V for 10 cycles at a rate of 100 mV/s. Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD)-Drop casting a suspension of Carbon nanodots (CD) |

Adsorption | Target DNA hybridization results in an electrochemical signal | [63] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Modification- Functionalization: Modifying Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor (MOSFET) with an electrolyte solution containing ions to create an Ion-Sensitive Field Effect Transistor (ISFET). |

- | Source-drain current modulated by gate potential and analyte concentration | [64] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Adsorption-Drop-casting solution containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes-graphene-ionic liquid (MWCNTs-Gr-IL). Chemical Deposition-Deposition of 4-amino-N, N, N-trimethylamine (ATA) + 4-amino benzenesulfonate (ABS) by applying electrochemical potential. |

Covalent Bond using Electrochemical Immobilization | Bioanalyte-biopreceptor binding reduces response to probe molecules | [65] |

| Electrochemical | Chemical Adsorption- By graphene-multiwalled carbon nanotubes; Chemical Adsorption-Drop-casting of chitosan-1-ethyl-3- methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethyl sulfonyl) imide (CS-IL); Coating- Electrodeposition: Deposition of amine-functionalized AuPb NPs |

Covalent Bond | Bioreceptor-bio analyte coupling alters impedimetric and amperometric responses | [66] |

| Electrochemical | - | Covalent Bond | Electroconductivity change with bacteria capture on the electrode | [67] |

| Electrochemical | Coating- Electrodeposition: Deposition of Pb NPs by cyclic voltammetry (CV) to increase the sensor's surface area |

Covalent Bond | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic (EIS) response change | [68] |

| Gravimetric | Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) | Thiol immobilization | Mass change is inversely proportional to crystal frequency change | [69] |

| Immunosensor | Chemical Modification- Functionalization: Electroreduction of carboxyphenyl diazonium salt |

Covalent Bond | Protein binding changes the electrochemical signal in SWV | [70] |

| Immunosensor | Chemical Modification- Functionalization: Treating potassium hydroxide (KOH); Chemical Modification- Attaching amine-functionalized silver nanoparticles (AgNp) using chemical linker Glutaraldehyde |

Covalent Bond using Glutaraldehyde | Procalcitonin-antibody interaction changes electrode current response | [71] |

| Nanoparticle | - | Physical Adsorption: Coating the micro-wells with E. granulosus antigen using the sodium carbonate method | Color change by nanoparticle detected by spectrophotometer | [72] |

| Nucleic Acid | Coating- Electrodeposition: Deposition of Cysteamine/AuNPs on the surface of Au electrodes |

- | DNA hybridization changes biosensor electrochemical behavior detected by SWV | [73] |

| Optical | - | - | Sensor responds to CDK6 activity via fluorescence changes | [74] |

| Optical | Chemical Modification- Surface Functionalization: Modification using luminol@Au/Ni-Co nanocages. |

Covalent Bond | Quenching luminescence for I27L detection via RET | [75] |

| Optical | Biomolecule Immobilization | Physical Adsorption | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | [12] |

| Optical | - | - | Refractive index change in PSM measured by near-infrared laser | [76] |

| Optical | Chemical Modification- Silanization: with a silane compound, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES). |

Covalent Bonding-Glutaraldehyde Immobilization | Fluorescence and reflection in porous silicon (PSi) | [77] |

| Optical | Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD)-Sputtering silver nanoparticles onto the porous silicon substrate. | - | Surface-enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | [3] |

| Optical | Chemical Modification- Functionalization: With Protein A |

Covalent Bonding: Antigen was immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane | Antibody presence causes color change in the complex | [78] |

| Optical | GQDs exhibit inherent surface characteristics based on their synthesis conditions | - | Fluorescence quenching in graphene quantum dots by chloride ions | [9] |

| Optical | Chemical Conjugation-Attachment of thiolated DNA probes onto gold nanoparticles (GNPs) | Adsorption | Capillary action binds target DNA to streptavidin, showing a red line | [79] |

| Optical | Coating- Electron Beam Deposition: On glass surfaces, with titanium (Ti) and gold (Au) coatings. Cleaning Process- By sonication in solvents of high polarity; Chemical Modification: Self Self-assembled monolayer (SAM) formation of thiol. |

Covalent Bond | SPR with PPRH probe recognizing DNA sequences | [80] |

| Optical (FRET) | Coating- Coating the surface with nickel | Coordination Bond: Between the His-tag and nickel coating | FRET signal decreases with fluorescent protein separation | [81] |

| Optical Microfiber | Chemical Modification- Salinization: with APTES(3-Aminopropyl-triethoxysilane) |

Cross Linking | Evanescent wave absorption by GNPs near fiber surface | [82] |

| Peptide | Surface Patterning-Use of screen printed electrode; Coating- Electrodeposition: of 4-amino-N, N, N-trimethylamine, and 4-amino benzenesulfonate. |

Covalent Bond | ESI measures the change in Rct with protein binding | [83] |

3. Advancements in Fabrication Methodology

3.1. Electrochemical Biosensor

3.2. Optical Biosensor

3.3. Nanomaterial Biosensors

3.4. Biological Biosensors

4. Application of Biosensing Techniques

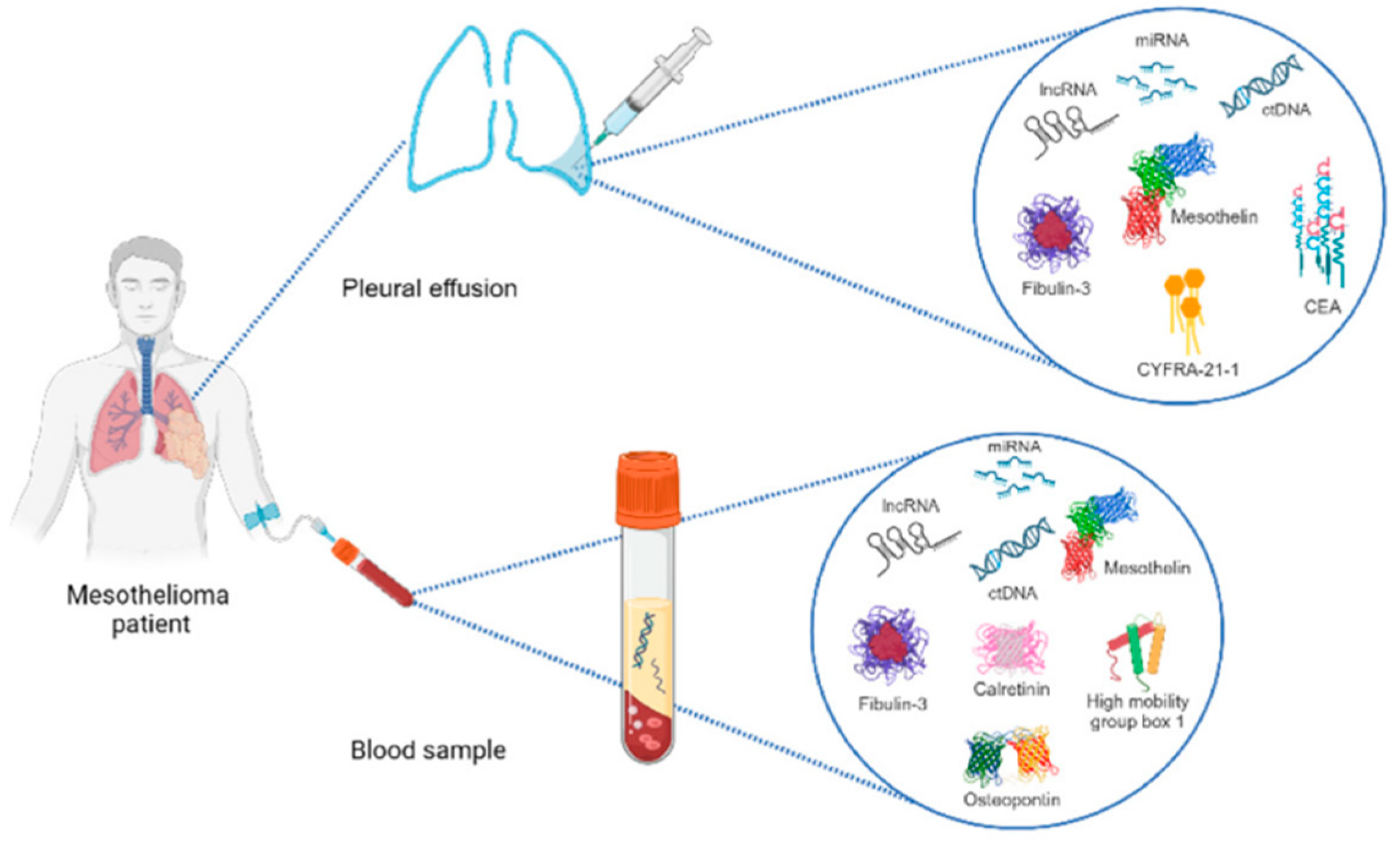

4.1. Mesothelioma

4.2. Hepatoblastoma

4.3. Cystic Echinococcosis

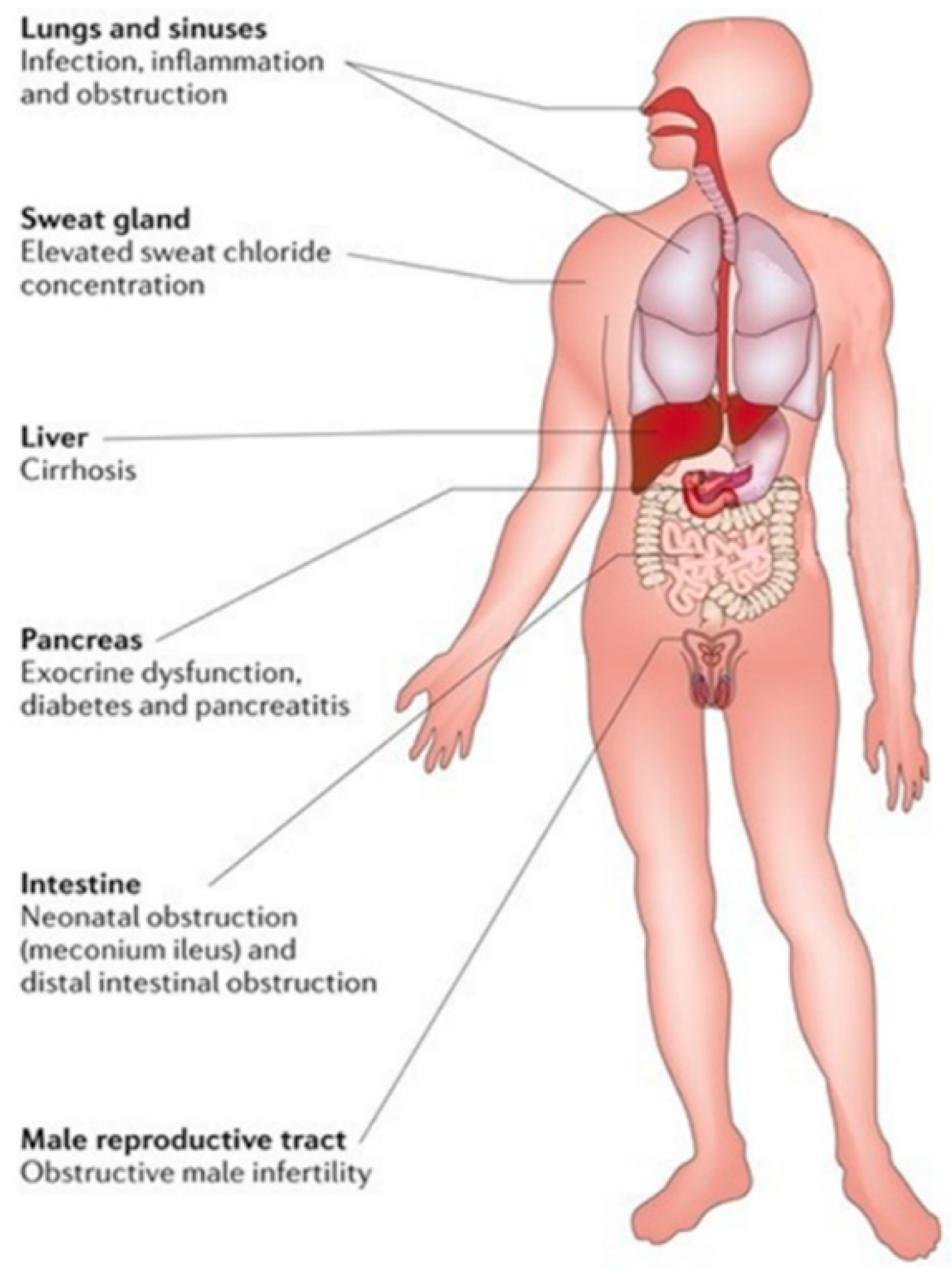

4.4. Cystic Fibrosis

4.5. MODY

4.6. Pneumonia

|

Disease |

Biosensor |

Bio analyte |

Accessibility |

Transducer |

Bioreceptor |

Type of Bioreceptor |

Dynamic Range of BS |

LOD |

Year |

|||

|

MPM |

Electrochemical |

HAPLN1 |

Serum |

Golden Electrode |

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) |

Amino Acid |

- |

10-9 M |

2013 [54] |

|||

| MPM | Optical | CDK-6 | Jurkat Cell Extract | TAMRA Dye | Phosphoamino Acid Binding Domain and 6-phosphofructokinase | Peptide | - | - | 2020 [74] | |||

| MPM | Gravimetric | Mesothelin | - | Golden Electrode | Mesothelin Antibody | Antibody | 100pg/mL- 50 ng/mL | - | 2023 [69] | |||

| HNF1A-MODY | Optical | I27L gene | - | Bare Glassy Carbon Electrode | Hairpin DNA (S1) | Nucleic Acid | 0.0001 - 100 nM | 23 fM | 2022 [75] | |||

| Inflammation; MODY | Electrochemical | CRP | Serum | Electronic Chip with Circularly Arranged Electrodes | Anti-CRP | Antibody | 102 - 107 pg/mL | 1 pg/mL | 2022 [55] | |||

| MODY | Electrochemical | CRP | Serum | Carbon Screen Printed Electrodes | Anti-CRP | Antibody | 1 - 100 ug/mL | 0.058 ug/mL for CSPE-COOH-AuNPs ; 0.085 uG/mL for CSPE-AuNPs-sam | 2021 [56] | |||

| MODY | Electrochemical | CRP | Blood Sample | Glassy Carbon Electrode | C-reactive protein (CRP) molecularly imprinted polymers (C-MIPs). | Polymer | 10- 5 -103 ng/mL | 0.41 × 10-5 ng/mL | 2021 [1] | |||

| MODY | Electrochemical | CRP | Blood Sample | Golden Nanowire | Anti-CRP | Antibody | 5 - 220 fg/mL | 2.25 fg/mL | 2019 [57] | |||

| MODY | Electrochemical | C-peptide | Serum | Indium Tin Oxide Electrode | Anti-C-Peptide | Antibody | 0.05 ng /mL -100 ng/mL | 0.0142 ng/mL | 2018 [58] | |||

| MODY | Electrochemical | C-peptide | serum | Glassy Carbon Electrode | Anti-C-Peptide | Antibody | 50 fg/mL - 16 ng/mL | 16.7 fg/mL. | 2017 [59] | |||

| Hepatoblastoma | Aptamer | AFP | - | Magnetic Beads | AFP Aptamer | Nucleic Acid | 0.5 - 104 ng/mL | 0.170 ng / mL | 2022 [53] | |||

| Hepatoblastoma | Optical | AFP; CEA | - | Silver Nanoclusters | AFP and CEA Aptamer | Nucleic Acid | - | AFP is 2.4 nM; CEA is 5.6 nM | 2019 [12] | |||

| Hepatoblastoma | Optical Microfiber | AFP | - | Single-Mode Optical Fiber | AFP Antibody | Antibody | - | 0.2 ng/mL in PBS; 2 ng/mL in bovine serum | 2013 [82] | |||

| Hepatoblastoma | Electrochemical | AFP | - | Silicon Nanowire | AFP Antibody | Antibody | 0.1 - 1 ng/mL | 0.1 ng/mL | 2015 [60] | |||

| Hydatidosis | Electrochemical | Immunoglobulin G Anti-Echinococcus Granulosus Antibodies | Serum | Gold Electrode | E. Granulosus Antigen | Antigen | - | 0.091 ng/ ml | 2010 [61] | |||

| Cystic Hydatid | Optical | Cystic Hydatid Antigens | - | Porous Silicon | - | - | 0.5 - 20 ng/mL | 0.16 ng/ml | 2017 [76] | |||

| Hydatid Disease | Optical | Egp38 Antigen | - | Porous Silicon | Rabbit Anti-p38 | Antibody | 0.5 - 15 pg/mL | 0.3 pg/mL | 2017 [77] | |||

| CE; AE | Optical | - | Blood Serum | Porous Silicon with Silver Composite Substrate | - | - | - | - | 2019 [3] | |||

| CE | Electrochemical | Hydatid Antigen and Antibody | - | Gold Electrode | Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody or Recombinant Antigen B (AgB) | Antigen-Antibody | Antigen:0.001-100 ng/mL; Antibody:0.001-10 ng/mL | Antigen:0.4 pg/mL; Antibody:0.3 pg/mL | 2020 [62] | |||

| CE | Optical | Anti-Echinococcus Granulosus Antibodies | Blood Sample | Gold Nanoparticles | Hydatid Cyst Antigen | Antigen | - | - | 2021 [78] | |||

| Hydatid Cyst | Nanoparticle | Anti-E. Granulosus Antibody | Tissue and Serum | Gold Nanoparticles | E. Granulosus Antigen | Antigen | 0.001–200 µg/ mL | 0.001 μg/ mL | 2022 [72] | |||

| Inflammation and CF | Optical (FRET) | NE | - | Cyan Fluorescent Protein (CFP) and Yellow Fluorescent Protein (YFP) | Phe-Ile-Arg-Trp (FIRW) sequence | Peptide Linker | - | - | 2016 [81] | |||

| CF | Electrochemical | 373-bases PCR amplicon of exon 11 of CFTR | Blood Smaple | Gold Electrode | CFTR gene | Peptide | - | 0.16 nM | 2017 [63] | |||

| SMA; CF; DMD | Immunosensor | SMN1, CFTR, and DMD proteins | Blood Sample | Carbon Nanofiber | anti-SMN1; anti-CFTR; anti-DMD | Antibody | - | CFTR:0.9 pg/mL, DMD:0.7 pg/mL and SMN1:0.74 pg/mL | 2018 [70] | |||

| CF | Optical | Clˉ | Sweat Sample | Graphine Quantum Dots (GQD) | ND | ND | 10 - 90 mM | 10 mM | 2022 [9] | |||

| CF | Electrochemical | Clˉ | Sweat Sample | Ion-Sensitive Field Effect Transistor (ISFET) | Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) | Polymer | - | 0.004 mol/m3 | 2023 [64] | |||

| Pneumonia | Immunosensor | Pro-calcitonin | - | Interdigitated Microelectrode (IDME) | Anti-procalcitonin | Antibody | - | 10 ng/mL | 2023 [71] | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Electrochemical | L-ascorbate 6-phosphate lactonase (AG) | Serum | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | S7 Peptide | Peptide | - | - | 2023 [65] | |||

| Mycoplasma Pneumonia | Optical | MP Genome | Sputum Specimen | Golden Nano Particle | ssDNA modified with Thiol (Probe) | Nucleic Acid | 3 - 3 × 106 copies | 3 copies | 2023 [79] | |||

| Pneumonia | Electrochemical | ssDNA of Pneumococcus | - | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Single-stranded DNA modified with Thiol (Probe) | Nucleic Acid | - | impedimetric technique- 3.4 μg/mL; amperometric technique- 21 μg/mL | 2022 [66] | |||

| Pneumonia | Electrochemical | GN/GP Bacteria | Sputum Specimen | Colistin- and Vancomycin- Electrodes | Colistin- and Vancomycin- Polymer Dot | Polymer | - | gram-negative:3.0 CFU/mL, R2:0.995 and gram-positive:3.1 CFU/mL, R2:0.994 | 2022 [67] | |||

| Pneumonia, Meningitis | Electrochemical | ss DNA of SPB | - | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | DNA sequence specific to SPB | Aptamer | - | 0.0022 ng/mL | 2022 [68] | |||

| Pneumocystis Pneumonia | Optical | mtLSU rRNA gene (P. jirovecii) | Lung Fluid | Golden Chip | Poly-Purine Reverse-Hoogsteen PPRH (Probe) | Nucleic Acid | - | 2.11 nM | 2020 [80] | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Peptide | UlaG | Serum | Carbon Electrode | Aniline-modified S7 Peptide | Peptide | 50 - 5 × 104 CFU/mL (25% human serum) | - | 2019 [83] | |||

| Legionnaires (severe pneumonia) | Nucleic Acid | L. pneumophila mip gene | - | Gold Electrode | Probe DNA | Nucleic Acid | 1 μM -1 ZM | 1 Zepto-molar | 2019 [73] | |||

6. Conclusion and Future Work

Funding

Abbreviation

| CFTR | Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator |

| MODY | Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young |

| 3D | Three Dimensional |

| RBP4 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| AlN | Aluminum Nitride |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| AlGaN | Aluminum Gallium Nitride |

| GaN | Gallium Nitride |

| HEMTs | High Electron Mobility Transistors |

| MOSHEMT | Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor High Electron Mobility Transistor |

| SAWs | Surface Acoustic Waves |

| BAWs | Bulk Acoustic Waves |

| CRISPR‒Cas | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated protein |

| FET | Field-Effect Transistor |

| DYRK1A | Dual-specificity Tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated Kinase 1A |

| aM | Attomolar |

| pM | Picomolar |

| GFET | Graphene Field-Effect Transistor |

| SiO2 | Silicon dioxide |

| APDMS | 3-ethoxy dimethylsilyl propylamine |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| PVD | Physical vapor deposition |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| PA-CVD | Plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition |

| HIPIMS | High-power impulse magnetron sputtering |

| SPCEs | Screen-printed carbon electrodes |

| CLL | Colloidal Lithography |

| NiTi | Nickel-Titanium (Nitinol) |

| CDs | Carbon Dots |

| QDs | Quantum Dots |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| CNFs | Carbon Nanofibers |

| GQDs | Graphene Quantum Dots |

| GDY | Graphdiyne |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| IFE | Inner Filter Effect |

| NF-kB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| SiNW-FETs | Silicon nanowire field-effect transistors |

| AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| AuPb NPs | Gold-lead bimetallic alloy nanoparticles |

| CS-IL | Trifluoromethylsulfonylimide |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| KOH | Potassium Hydroxide |

| PDs | Polymer Dots |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| D-Ala-D-Ala | D-Alanyl-D-Alanine |

| PD-Colis | Polydopamine-Colistin |

| PD-Vanco | Polydopamine-Vancomycin |

| SEAP | Secreted Alkaline Phosphatase |

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| BSA-T | Bovine Serum Albumin-Tween |

| 5kPEG | 5k Polyethylene Glycol |

| MCU-T | Mercaptoundecanol-Tween |

| ICP | Ion Concentration Polarization |

| Rct | Charge Transfer Resistance |

| EDC/NHS | N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide/N-Hydroxysuccinimide |

| CRISPR/Cas12a | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 12a |

| HCR | Hybridization Chain Reaction |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| Cas12a | CRISPR-associated protein 12a |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | CRISPR associated protein 9 |

| MIT | Molecular Imprinting Technology |

| MIPs | Molecular Imprinting Polymers |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| PDA | Polydopamine |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| GCE | Glassy Carbon Electrode |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| SAM | Self-Assembled Monolayers |

| SH-ssDNA | Thiol-Modified Single-Stranded DNA |

| HS-C11-(EG)3-OCH2-COOH | Polyethylene Glycol-Thiol HS-C11-(EG)3-OCH2-COOH |

| SBP-SPA | Streptavidin-Binding Protein-Streptavidin Protein A |

| 11-MUA | 11-Mercaptoundecanoic Acid |

| DTDPA | Dithiobis [succinimidyl propionate] |

| MHDA | Mercaptohexadecanoic Acid |

| MUD | Mercaptoundecanol |

| n-DEP | Negative Dielectrophoresis |

| DS‒PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate‒Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| ssDNA | Single-Stranded DNA |

| –SH | Sulfhydryl |

| sgRNA | Single Guide RNA |

| QCM | Quartz Crystal Microbalance |

| kDa | kilodaltons |

| TRX | Thioredoxin |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| HB | Hepatoblastoma |

| SiNW | Silicon Nanowire |

| ARHGEF2 | Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor 2 |

| TMED3 | Transmembrane Emp24 Protein Transport Domain Containing 3 |

| TCF3 | Transcription Factor 3 |

| STMN1 | Stathmin 1 |

| RAVER2 | Ribonucleoprotein, PTB-Binding 2 |

| RIU | Refractive Index Unit |

| Cor | Correlation |

| CXCL7 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7 |

| MIF | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor |

| IL-25 | Interleukin-25 |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| A-AgNCs | Adenine-Ag nanoclusters |

| C-AgNCs | Cytosine-Ag nanoclusters |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| FL | Fluorescence |

| PDANs | Polydopamine nanoparticles |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| SAT-HCR | Signal Amplification by Templated Hybridization Chain Reaction |

| ECP | Eosinophilic cationic protein |

| PET-CTI | Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography Imaging |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| AuNP | Gold nanoparticles |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| RS | Raman Spectroscopy |

| SERS | Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy |

| CE | Cystic Echinococcosis |

| Eg-cMDH | Echinococcus granulosus cytoplasmic Malate Dehydrogenase |

| Eg-CS | Echinococcus granulosus Citrate Synthase |

| egr-miR-2a-3p | Echinococcus granulosus microRNA-2a-3p |

| sCD14 | soluble CD14 |

| ROC-AUC | Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve |

| Cl | Chloride |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| GCK-MODY 2 | Glucokinase-Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young 2 |

| HNF1A-MODY 3 | Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1 Alpha-Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young 3 |

| TD1 | Type 1 Diabetes |

| TD2 | Type 2 Diabetes |

| hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| IL-17A | Interleukin 17A |

| IL-23 | Interleukin 23 |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HNF1A-MODY | Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1 Alpha - Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young |

| GCK | Glucokinase |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| IDME | Interdigitated Microelectrode |

| HPLC-UV | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography - Ultraviolet |

| LLOQ | Lower Limit of Quantification |

| CAP | Community-Acquired Pneumonia |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar Lavage |

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

Availability of data and material

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

References

- Cui, M.; et al. A graphdiyne-based protein molecularly imprinted biosensor for highly sensitive human C-reactive protein detection in human serum. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 431, 133455. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, I.; et al. ERS/ESTS/EACTS/ESTRO guidelines for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery 2020, 58(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; et al. Rapid and label-free screening of echinococcosis serum profiles through surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2020, 412, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; et al. Understanding CFTR Functionality: A Comprehensive Review of Tests and Modulator Therapy in Cystic Fibrosis. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 2024, 82(1), 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tuerxunyiming, M.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of serum proteins uncovers a protein signature related to Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY). Journal of proteome research 2018, 17(1), 670–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mandell, L.A.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clinical infectious diseases 2007, 44(Supplement_2), S27–S72. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasetti, M.; et al. ATG5 as biomarker for early detection of malignant mesothelioma. BMC Research Notes 2023, 16(1), 61. [Google Scholar]

- Schnater, J.M.; et al. Where do we stand with hepatoblastoma? Cancer 2003, 98(4), 668–678. [Google Scholar]

- Ifrah, Z.; et al. Fluorescence quenching of graphene quantum dots by chloride ions: A potential optical biosensor for cystic fibrosis. Frontiers in Materials 2022, 9, 857432. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y., Z. Guo, and G. Ge, Enzyme-Based Biosensors and Their Applications. Biosensors 2023, 13(4), 476–476.

- Meskher, H.; et al. Recent trends in carbon nanotube (CNT)-based biosensors for the fast and sensitive detection of human viruses: a critical review. Nanoscale advances 2023, 5(4), 992–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y., Y. Tang, and P. Miao, Polydopamine nanosphere@ silver nanoclusters for fluorescence detection of multiplex tumor markers. Nanoscale 2019, 11(17), 8119–8123. [CrossRef]

- Enrico, A.; et al. Cleanroom-Free Direct Laser Micropatterning of Polymers for Organic Electrochemical Transistors in Logic Circuits and Glucose Biosensors. Advanced Science 2024, 2307042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmara, G.; et al. Functional 3D printing: Approaches and bioapplications. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 175, 112849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruncillo, S.; et al. Lithographic processes for the scalable fabrication of micro-and nanostructures for biochips and biosensors. ACS sensors 2021, 6(6), 2002–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, V. and N. Lee, A review on biosensors and recent development of nanostructured materials-enabled biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21(4), 1109. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-F., Z.-B. Guo, and G.-B. Ge, Enzyme-Based Biosensors and Their Applications. Biosensors 2023, 13(4), 476.

- Bilge, S.; et al. Recent trends in core/shell nanoparticles: their enzyme-based electrochemical biosensor applications. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191(5), 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Research on Fiber Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors: A Review. Photonic Sensors 2024, 14(2), 240201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; et al. Recent advances in biological applications of aptamer-based fluorescent biosensors. Molecules 2023, 28(21), 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira-Antunes, B. and H.A. Ferreira, Nucleic Acid Aptamer-Based Biosensors: A Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11(12), 3201.

- Park, J.-H., Y.-S. Eom, and T.-H. Kim, Recent advances in aptamer-based sensors for sensitive detection of neurotransmitters. Biosensors 2023, 13(4), 413.

- Léguillier, V., B. Heddi, and J. Vidic, Recent Advances in Aptamer-Based Biosensors for Bacterial Detection. Biosensors 2024, 14(5), 210.

- Chen, S.; et al. Advances in Synthetic-Biology-Based Whole-Cell Biosensors: Principles, Genetic Modules, and Applications in Food Safety. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(9), 7989. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, C.-y., M.-q. Liu, and Y. Guo, Synthetic bacteria designed using ars operons: a promising solution for arsenic biosensing and bioremediation. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 40(6), 192.

- Mallozzi, A.; et al. A general strategy to engineer high-performance mammalian Whole-Cell Biosensors. bioRxiv, 2024 2024,02. 28.582526.

- Lo, P.K. , Nanometre-Scale Biosensors Revolutionizing Applications in Biomedical and Environmental Research. Biosensors 2023, 13(11), 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban Hanoglu, S.; et al. Recent Approaches in Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Biosensors of miRNA Detection. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; et al. Advances in Engineered Nano-Biosensors for Bacteria Diagnosis and Multidrug Resistance Inhibition. Biosensors 2024, 14(2), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, D.; et al. Recent Progress of Electrochemical Aptasensors toward AFB1 Detection (2018–2023). Biosensors 2024, 14(1), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; et al. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors: Applications, challenges, and future scope. Biosensors 2021, 11(9), 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, A.; et al. Recent advances in optical biosensors for sensing applications: a review. Plasmonics 2023, 18(2), 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; et al. A High-Sensitivity Gravimetric Biosensor Based on S1 Mode Lamb Wave Resonator. Sensors 2022, 22(15), 5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nian, L.; et al. Preparation, Characterization, and Application of AlN/ScAlN Composite Thin Films. Micromachines 2023, 14(3), 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; et al. Acoustic radiation-free surface phononic crystal resonator for in-liquid low-noise gravimetric detection. Microsystems & nanoengineering 2021, 7(1), 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, N., J. Wang, and Y. Zhou, Rapid Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand of Water Using a Thermal Biosensor. Sensors 2014, 14(6), 9949–9960.

- Bouguenna, A.; et al. Performance Analysis of AlGaN MOSHEMT Based Biosensors for Detection of Proteins. Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials 2023, 24(3), 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, A.M.; et al. A dielectrically modulated GaN/AlN/AlGaN MOSHEMT with a nanogap embedded cavity for biosensing applications. IETE Journal of Research 2023, 69(3), 1419–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, M.P., A.J.T. Teo, and K.H.H. Li, Acoustic Biosensors and Microfluidic Devices in the Decennium: Principles and Applications. Micromachines 2022, 13(1), 24.

- Plikusiene, I. and A. Ramanaviciene, Investigation of biomolecule interactions: Optical-, electrochemical-, and acoustic-based biosensors. Biosensors 2023, 13(2), 292.

- Zhang, X.; et al. Asymmetric Schottky Barrier-Generated MoS2/WTe2 FET Biosensor Based on a Rectified Signal. Nanomaterials 2024, 14(2), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.L.; et al. Efficient Chemical Surface Modification Protocol on SiO2 Transducers Applied to MMP9 Biosensing. Sensors 2021, 21(23), 8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; et al. Surface Modification Strategies for Biomedical Applications: Enhancing Cell–Biomaterial Interfaces and Biochip Performances. BioChip Journal 2023, 17(2), 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichou, H.; et al. Exploring the advancements in physical vapor deposition coating: a review. Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion 2024, 10(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, Z.; et al. A comprehensive calibration of integrated magnetron sputtering and plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition for rare-earth doped thin films. Journal of Materials Research 2024, 39(1), 150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Osaki, S.; et al. Surface Modification of Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode through Oxygen Plasma to Enhance Biosensor Sensitivity. Biosensors 2024, 14(4), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, R. Nanotechnology-enabled biosensors: a review of fundamentals, materials, applications, challenges, and future scope. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2024, 2(2), 759–777. [Google Scholar]

- Minati, L.; et al. Plasma assisted surface treatments of biomaterials. Biophysical Chemistry 2017, 229, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Topor, C.-V., M. Puiu, and C. Bala, Strategies for Surface Design in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensing. Biosensors 2023, 13(4), 465.

- Casalini, S.; et al. Self-assembled monolayers in organic electronics. Chemical Society Reviews 2017, 46(1), 40–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharath Kumar, J., R. Kumar, and R. Verma, Surface Modification Aspects for Improving Biomedical Properties in Implants: A Review. Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters) 2024, 37(2), 213–241.

- Safavi, M.S.; et al. Surface modified NiTi smart biomaterials: Surface engineering and biological compatibility. Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 2023, 25, 100429. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; et al. A functionalized magnetic nanoparticle regulated CRISPR-Cas12a sensor for the ultrasensitive detection of alpha-fetoprotein. Analyst 2022, 147(14), 3186–3192. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, A.; et al. Development of a biosensor for detection of pleural mesothelioma cancer biomarker using surface imprinting. PLoS One 2013, 8(3), e57681. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, H.-J.; et al. Electrochemical biosensor with electrokinetics-assisted molecular trapping for enhancing C-reactive protein detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2022, 210, 114338. [Google Scholar]

- Guillem, P.; et al. A low-cost electrochemical biosensor platform for C-reactive protein detection. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2021, 31, 100402. [Google Scholar]

- Vilian, A.E.; et al. Efficient electron-mediated electrochemical biosensor of gold wire for the rapid detection of C-reactive protein: A predictive strategy for heart failure. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 142, 111549. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; et al. A sensitive electrochemiluminescent biosensor based on AuNP-functionalized ITO for a label-free immunoassay of C-peptide. Bioelectrochemistry 2018, 123, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; et al. High-sensitive electrochemiluminescence C-peptide biosensor via the double quenching of dopamine to the novel Ru (II)-organic complex with dual intramolecular self-catalysis. Analytical chemistry 2017, 89(20), 11076–11082. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; et al. Highly sensitive, label-free and real-time detection of alpha-fetoprotein using a silicon nanowire biosensor. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 2015, 75(7), 578–584. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, S.V.; et al. Microfluidic immunosensor with gold nanoparticle platform for the determination of immunoglobulin G anti-Echinococcus granulosus antibodies. Analytical biochemistry 2011, 409(1), 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Eissa, S., R. Noordin, and M. Zourob, Voltammetric Label-free Immunosensors for the Diagnosis of Cystic Echinococcosis. Electroanalysis 2020, 32(6), 1170–1177.

- García-Mendiola, T.; et al. Carbon nanodots based biosensors for gene mutation detection. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 256, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- la Grasta, A.; et al. Potentiometric Chloride Ion Biosensor for Cystic Fibrosis Diagnosis and Management: Modeling and Design. Sensors 2023, 23(5), 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, F.; et al. A novel chemometric-amperometric biosensor for selective and ultra-sensitive determination of Streptococcus pneumoniae based on detection of a protein marker: A suitable and reliable alternative method. Microchemical Journal 2023, 193, 109122. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi, A.; et al. An efficiently engineered electrochemical biosensor as a novel and user-friendly electronic device for biosensing of Streptococcus Pneumoniae bacteria. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2022, 36, 100494. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.J.; et al. Rapid and selective electrochemical sensing of bacterial pneumonia in human sputum based on conductive polymer dot electrodes. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 368, 132084. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi, A.; et al. A novel electrochemical biosensor as an efficient electronic device for impedimetric and amperometric quantification of the pneumococcus. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2022, 37, 100506. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, H.C.; et al. Development of a quartz crystal microbalance-based immunosensor for the early detection of mesothelin in cancer. Sensors International 2023, 4, 100248. [Google Scholar]

- Eissa, S.; et al. Carbon nanofiber-based multiplexed immunosensor for the detection of survival motor neuron 1, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy proteins. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2018, 117, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-based point-of-care lateral flow biosensor with improved performance for rapid and robust detection of Mycoplasma pneumonia. Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1257, 1257, 341175. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, F.; et al. Design of highly sensitive nano-biosensor for diagnosis of hydatid cyst based on gold nanoparticles. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2022, 38, 102786. [Google Scholar]

- Mobed, A.; et al. An innovative nucleic acid based biosensor toward detection of Legionella pneumophila using DNA immobilization and hybridization: A novel genosensor. Microchemical Journal 2019, 148, 708–716. [Google Scholar]

- Soamalala, J.; et al. Fluorescent peptide biosensor for probing CDK6 kinase activity in lung cancer cell extracts. ChemBioChem 2021, 22(6), 1065–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.; et al. A stochastic DNA walker electrochemiluminescence biosensor based on quenching effect of Pt@ CuS on luminol@ Au/Ni-Co nanocages for ultrasensitive detection of I27L gene. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 434, 134681. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P., Z. Jia, and G. Lü, Hydatid detection using the near-infrared transmission angular spectra of porous silicon microcavity biosensors. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 44798.

- Li, Y.; et al. Detection of Echinococcus granulosus antigen by a quantum dot/porous silicon optical biosensor. Biomedical optics express 2017, 8(7), 3458–3469. [Google Scholar]

- Safarpour, H.; et al. Development of optical biosensor using protein a-conjugated chitosan–gold nanoparticles for diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Biosensors 2021, 11(5), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; et al. Synthesised silver nanoparticles mediate interdigitated nanobiosensing for sensitive Pneumonia identification. Materials Express 2023, 13(2), 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Lozano, O.; et al. Fast and Accurate Pneumocystis Pneumonia Diagnosis in Human Samples Using a Label-Free Plasmonic Biosensor. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 10(6), E1246–E1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenburg, C.; et al. A FRET-based biosensor for the detection of neutrophil elastase. Analyst 2016, 141(5), 1645–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; et al. Gold nanoparticle amplified optical microfiber evanescent wave absorption biosensor for cancer biomarker detection in serum. Talanta 2014, 120, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.-H.; et al. An antifouling peptide-based biosensor for determination of Streptococcus pneumonia markers in human serum. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2020, 151, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavignac, N., C.J. Allender, and K.R. Brain, Current status of molecularly imprinted polymers as alternatives to antibodies in sorbent assays. Analytica chimica acta 2004, 510(2), 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Jeyachandran, Y.L.; et al. Efficiency of blocking of non-specific interaction of different proteins by BSA adsorbed on hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces. Journal of colloid and interface science 2010, 341(1), 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; et al. Electrochemical Aptasensor Developed Using Two-Electrode Setup and Three-Electrode Setup: Comprising Their Current Range in Context of Dengue Virus Determination. Biosensors 2022, 13(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randriamahazaka, H. and J. Ghilane, Electrografting and controlled surface functionalization of carbon based surfaces for electroanalysis. Electroanalysis 2016, 28(1), 13–26. [CrossRef]

- Belanger, D. and J. Pinson, Electrografting: a powerful method for surface modification. Chemical Society Reviews 2011, 40(7), 3995–4048. [CrossRef]

- Cugnet, C.; et al. A novel microelectrode array combining screen-printing and femtosecond laser ablation technologies: Development, characterization and application to cadmium detection. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2009, 143(1), 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, M.; et al. A HepG2 cell-based biosensor that uses stainless steel electrodes for hepatotoxin detection. Biosensors 2022, 12(3), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Towards genoelectronics: electrochemical biosensing of DNA hybridization. Chemistry–A European Journal 1999, 5(6), 1681–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Paleček, E. , Past, present and future of nucleic acids electrochemistry. Talanta 2002, 56(5), 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mendiola, T.; et al. Dyes as bifunctional markers of DNA hybridization on surfaces and mutation detection. Bioelectrochemistry 2016, 111, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esteban, M., C. Arino, and J. Díaz-Cruz, Chemometrics in electroanalytical chemistry. Critical reviews in analytical chemistry 2006, 36(3-4), 295–313.

- Grabaric, B., R. O'Halloran, and D. Smith, Resolution enhancement of ac polarographic peaks by deconvolution using the fast fourier transform. Analytica Chimica Acta 1981, 133(3), 349–358.

- Dauphin-Ducharme, P.; et al. Simulation-based approach to determining electron transfer rates using square-wave voltammetry. Langmuir 2017, 33(18), 4407–4413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Putzbach, W. and N.J. Ronkainen, Immobilization techniques in the fabrication of nanomaterial-based electrochemical biosensors: A review. Sensors 2013, 13(4), 4811–4840.

- Prakash, J., J. Pivin, and H. Swart, Noble metal nanoparticles embedding into polymeric materials: From fundamentals to applications. Advances in colloid and interface science 2015, 226, 187–202.

- Sau, T.K.; et al. Properties and applications of colloidal nonspherical noble metal nanoparticles. Advanced Materials 2010, 22(16), 1805–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. An energetic CuS–Cu battery system based on CuS nanosheet arrays. ACS nano 2021, 15(3), 5420–5427. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, S., D. Sarkar, and G. Madras, Hierarchical design of CuS architectures for visible light photocatalysis of 4-chlorophenol. ACS omega 2017, 2(7), 4009–4021.

- Singh, B.; et al. Electrochemical transformation of Prussian blue analogues into ultrathin layered double hydroxide nanosheets for water splitting. Chemical Communications 2020, 56(95), 15036–15039. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. Electrochemical conversion of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles to electroactive Prussian blue analogues for self-sacrificial label biosensing of avian influenza virus H5N1. Analytical chemistry 2017, 89(22), 12145–12151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; et al. PtCo nanocubes/reduced graphene oxide hybrids and hybridization chain reaction-based dual amplified electrochemiluminescence immunosensing of antimyeloperoxidase. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 142, 111548. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; et al. Prussian blue analogues in aqueous batteries and desalination batteries. Nano-micro letters 2021, 13, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, C.; et al. High Performance Biosensor for Detection of the Normal and Cancerous Liver Tissues Based on 1D Photonic Band Gap Material Structures. Sensing and Imaging 2023, 24(1), 27. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, A.H.; et al. MATLAB simulation-based theoretical study for detection of a wide range of pathogens using 1D defective photonic structure. Crystals 2022, 12(2), 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.H.; et al. Study on a one-dimensional defective photonic crystal suitable for organic compound sensing applications. RSC advances 2021, 11(52), 32973–32980. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, A.H.; et al. Detection of reproductive hormones in females by using 1D photonic crystal-based simple reconfigurable biosensing design. Crystals 2021, 11(12), 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S. and S.R. Emory, Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. science 1997, 275(5303), 1102–1106.

- Casteleiro, B.; et al. Encapsulation of gold nanoclusters by photo-initiated miniemulsion polymerization. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2022, 648, 129410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. One Stone, Three Birds: Multifunctional Nanodots as “Pilot Light” for Guiding Surgery, Enhanced Radiotherapy, and Brachytherapy of Tumors. ACS Central Science 2023, 9(10), 1976–1988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; et al. GSH-triggered sequential catalysis for tumor imaging and eradication based on star-like Au/Pt enzyme carrier system. Nano Research 2020, 13, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; et al. Electrochemical aptasensor based on DNA-templated copper nanoparticles and RecJf exonuclease-assisted target recycling for lipopolysaccharide detection. Analytical Methods 2024, 16(3), 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W. Zhou, W. and S. Dong, A new AgNC fluorescence regulation mechanism caused by coiled DNA and its applications in constructing molecular beacons with low background and large signal enhancement. Chemical communications 2017, 53(91), 12290–12293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; et al. Thermal Probing Techniques for a Single Live Cell. Sensors 2022, 22(14), 5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, F.P.; et al. The chiral nano-world: chiroptically active quantum nanostructures. Nanoscale Horizons 2016, 1(1), 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Chemical etching of pH-sensitive aggregation-induced emission-active gold nanoclusters for ultra-sensitive detection of cysteine. Nanoscale 2019, 11(1), 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. and E. Wang, Metal nanoclusters: new fluorescent probes for sensors and bioimaging. Nano Today 2014, 9(1), 132–157. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; et al. Research on measurement conditions for obtaining significant, stable, and repeatable SERS signal of human blood serum. IEEE Photonics Journal 2017, 9(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krismastuti, F.S., S. Pace, and N.H. Voelcker, Porous silicon resonant microcavity biosensor for matrix metalloproteinase detection. Advanced functional materials 2014, 24(23), 3639–3650. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; et al. Spectrometer-free biological detection method using porous silicon microcavity devices. Optics Express 2015, 23(19), 24626–24633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dorfner, D.; et al. Optical characterization of silicon on insulator photonic crystal nanocavities infiltrated with colloidal PbS quantum dots. Applied Physics Letters 2007, 91(23). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. and B.T. Cunningham, Enhanced quantum dot optical down-conversion using asymmetric 2D photonic crystals. Optics Express 2011, 19(5), 3908–3918.

- Liu, C.; et al. Enhancement of QDs' fluorescence based on porous silicon Bragg mirror. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2015, 457, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; et al. Detection of CRISPR-dCas9 on DNA with solid-state nanopores. Nano letters 2018, 18(10), 6469–6474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; et al. Skin pigmentation-inspired polydopamine sunscreens. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28(33), 1802127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. High Relaxivity Gadolinium-Polydopamine Nanoparticles. Small 2017, 13(43), 1701830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. Optical lateral flow test strip biosensors for pesticides: Recent advances and future trends. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 144, 116427. [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Torralba, A.; et al. Toward next generation lateral flow assays: Integration of nanomaterials. Chemical Reviews 2022, 122(18), 14881–14910. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; et al. Rapid lateral flow immunoassay for the fluorescence detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2020, 4(12), 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mao, M.; et al. Design and optimizing gold nanoparticle-cDNA nanoprobes for aptamer-based lateral flow assay: Application to rapid detection of acetamiprid. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2022, 207, 114114. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; et al. Development of a lateral flow strip membrane assay for rapid and sensitive detection of the SARS-CoV-2. Analytical Chemistry 2020, 92(20), 14139–14144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cherkaoui, D.; et al. Harnessing recombinase polymerase amplification for rapid multi-gene detection of SARS-CoV-2 in resource-limited settings. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 189, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; et al. Multiplex assay of viruses integrating recombinase polymerase amplification, barcode—anti-barcode pairs, blocking anti-primers, and lateral flow assay. Analytical chemistry 2021, 93(40), 13641–13650. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; et al. Rapid authentication of mutton products by recombinase polymerase amplification coupled with lateral flow dipsticks. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2019, 290, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; et al. Multiplexed electrical detection of cancer markers with nanowire sensor arrays. Nature biotechnology 2005, 23(10), 1294–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Arizti-Sanz, J.; et al. Streamlined inactivation, amplification, and Cas13-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nature communications 2020, 11(1), 5921. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, J.P.; et al. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nature biotechnology 2020, 38(7), 870–874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; et al. CRISPR/Cas12a based fluorescence-enhanced lateral flow biosensor for detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 351, 130906. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H.; et al. Advances in clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based diagnostic assays assisted by micro/nanotechnologies. ACS nano 2021, 15(5), 7848–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajian, R.; et al. Detection of unamplified target genes via CRISPR–Cas9 immobilized on a graphene field-effect transistor. Nature biomedical engineering 2019, 3(6), 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; et al. Porous silicon optical microcavity biosensor on silicon-on-insulator wafer for sensitive DNA detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2013, 44, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; et al. Hybridization assay of insect antifreezing protein gene by novel multilayered porous silicon nucleic acid biosensor. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2013, 39(1), 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, C.M. and R.G. Compton, The use of nanoparticles in electroanalysis: a review. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2006, 384, 601–619. [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, V.; et al. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots for DNA labeling and its electrochemical, fluorescent and electrophoretic characterization. Chemical Papers 2015, 69(1), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., I. Willner, and J. Wang, Electroanalytical and Bioelectroanalytical Systems Based on Metal and Semiconductor Nanoparticles. Electroanalysis 2004, 16(1-2), 19–44. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Carbon nanodots: synthesis, properties and applications. Journal of materials chemistry 2012, 22(46), 24230–24253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Ionic liquid-functionalized fluorescent carbon nanodots and their applications in electrocatalysis, biosensing, and cell imaging. Langmuir 2014, 30(49), 15016–15021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots as a new substrate for sensitive glucose determination. Sensors 2016, 16(5), 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Horseradish peroxidase immobilization on carbon nanodots/CoFe layered double hydroxides: direct electrochemistry and hydrogen peroxide sensing. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2015, 64, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.-L.; et al. Label-free and ratiometric detection of nuclei acids based on graphene quantum dots utilizing cascade amplification by nicking endonuclease and catalytic G-quadruplex DNAzyme. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2016, 81, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-J.; et al. Synthesis of ruthenium (II) complexes and characterization of their cytotoxicity in vitro, apoptosis, DNA-binding and antioxidant activity. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2010, 45(7), 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; et al. Mechanisms behind excitation-and concentration-dependent multicolor photoluminescence in graphene quantum dots. Nanoscale 2020, 12(2), 591–601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; et al. Effects of elemental doping on the photoluminescence properties of graphene quantum dots. RSC advances 2016, 6(94), 91225–91232. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; et al. Recent advances in graphene quantum dots for sensing. Materials today 2013, 16(11), 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; et al. Luminescent graphene quantum dots as new fluorescent materials for environmental and biological applications. TrAC trends in analytical chemistry 2014, 54, 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., W. Pisula, and K. Müllen, Graphenes as potential material for electronics. Chemical reviews 2007, 107(3), 718–747.

- Sanghavi, B.J.; et al. Real-time electrochemical monitoring of adenosine triphosphate in the picomolar to micromolar range using graphene-modified electrodes. Analytical chemistry 2013, 85(17), 8158–8165. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, M.; et al. Electrocatalytic processes promoted by diamond nanoparticles in enzymatic biosensing devices. Bioelectrochemistry 2016, 111, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Swami, N.S., C.-F. Chou, and R. Terberueggen, Two-potential electrochemical probe for study of DNA immobilization. Langmuir 2005, 21(5), 1937–1941.

- Qi, B.-P.; et al. An efficient edge-functionalization method to tune the photoluminescence of graphene quantum dots. Nanoscale 2015, 7(14), 5969–5973. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; et al. Antibacterial activity of graphdiyne and graphdiyne oxide. Small 2020, 16(34), 2001440. [Google Scholar]

- Min, H.; et al. Synthesis and imaging of biocompatible graphdiyne quantum dots. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11(36), 32798–32807. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; et al. Graphene biosensors for bacterial and viral pathogens. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2020, 166, 112471. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.Y.; et al. Investigating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses elicited by silver nanoparticles using high-throughput reporter genes in HepG2 cells: effect of size, surface coating, and intracellular uptake. Toxicology in vitro 2013, 27(6). [Google Scholar]

- Stępkowski, T., K. Brzóska, and M. Kruszewski, Silver nanoparticles induced changes in the expression of NF-κB related genes are cell type specific and related to the basal activity of NF-κB. Toxicology in Vitro 2014, 28(4), 473–478.

- Chen, J.; et al. Inflammatory MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways differentiated hepatitis potential of two agglomerated titanium dioxide particles. Journal of hazardous materials 2016, 304, 370–378. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; et al. A cell-based biosensor for nanomaterials cytotoxicity assessment in three dimensional cell culture. Toxicology 2016, 370, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Thurn-Albrecht, T.; et al. Ultrahigh-density nanowire arrays grown in self-assembled diblock copolymer templates. Science 2000, 290(5499), 2126–2129. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; et al. Optical properties of the ZnO nanotubes synthesized via vapor phase growth. Applied Physics Letters 2003, 83(9), 1689–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiate, P.; et al. High sensitive and selective C-reactive protein detection by means of lossy mode resonance based optical fiber devices. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2017, 93, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. High-throughput fabrication of compact and flexible bilayer nanowire grid polarizers for deep-ultraviolet to infrared range. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B 2014, 32(3), 031206. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; et al. Recent progress in metal nanowires for flexible energy storage devices. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10, 920430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-J.; et al. An integrated chip for rapid, sensitive, and multiplexed detection of cardiac biomarkers from fingerprick blood. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 28(1), 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; et al. Silicon-nanowire-based CMOS-compatible field-effect transistor nanosensors for ultrasensitive electrical detection of nucleic acids. Nano letters 2011, 11(9), 3974–3978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-J.; et al. Label-free direct detection of MiRNAs with silicon nanowire biosensors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2009, 24(8), 2504–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-J.; et al. Silicon nanowire biosensor for highly sensitive and rapid detection of Dengue virus. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2010, 146(1), 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-I., B.-R. Li, and Y.-T. Chen, Silicon nanowire field-effect transistor-based biosensors for biomedical diagnosis and cellular recording investigation. Nano today 2011, 6(2), 131–154.

- Lieber, C.M. , Semiconductor nanowires: A platform for nanoscience and nanotechnology. Mrs Bulletin 2011, 36(12), 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-S.; et al. Monitoring extracellular K+ flux with a valinomycin-coated silicon nanowire field-effect transistor. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2012, 31(1), 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patolsky, F. and C.M. Lieber, Nanowire nanosensors. Materials today 2005, 8(4), 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; et al. Label-free immunodetection with CMOS-compatible semiconducting nanowires. Nature 2007, 445(7127), 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunimovich, Y.L.; et al. Quantitative real-time measurements of DNA hybridization with alkylated nonoxidized silicon nanowires in electrolyte solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2006, 128(50), 16323–16331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, W.D. Geoghegan, W.D. and G.A. Ackerman, Adsorption of horseradish peroxidase, ovomucoid and anti-immunoglobulin to colloidal gold for the indirect detection of concanavalin A, wheat germ agglutinin and goat anti-human immunoglobulin G on cell surfaces at the electron microscopic level: a new method, theory and application. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 1977, 25(11), 1187–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Büchel, C.; et al. Localisation of the PsbH subunit in photosystem II: a new approach using labelling of His-tags with a Ni2+-NTA gold cluster and single particle analysis. Journal of molecular biology 2001, 312(2), 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecka, M. and M. Hepel, Double-shell gold nanoparticle-based DNA-carriers with poly-L-lysine binding surface. Biomaterials 2011, 32(12), 3312–3321. [CrossRef]

- Veigas, B.; et al. One nanoprobe, two pathogens: gold nanoprobes multiplexing for point-of-care. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2015, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, A. and F. Farjami, Electrodeposition of gold–platinum alloy nanoparticles on ionic liquid–chitosan composite film and its application in fabricating an amperometric cholesterol biosensor. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 26(5), 2547–2552.

- Bjørklund, G.; et al. A review on coordination properties of thiol-containing chelating agents towards mercury, cadmium, and lead. Molecules 2019, 24(18), 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Kalajahi, M.; et al. Electrodeposition of taurine on gold surface and electro-oxidation of malondialdehyde. Surface Engineering 2015, 31(3), 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jadzinsky, P.; et al. Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1 A resolution. Science (New York, NY) 2007, 318(5849), 430–433. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, T.; et al. Platinum black/gold nanoparticles/polyaniline modified electrochemical microneedle sensors for continuous in vivo monitoring of pH value. Polymers 2023, 15(13), 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, C.; et al. Hyper crosslinked polymer supported NHC stabilized gold nanoparticles with excellent catalytic performance in flow processes. Nanoscale Advances 2023, 5(4), 1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, S., S. Mukherji, and S. Mukherji, Size-controlled silver nanoparticles synthesized over the range 5–100 nm using the same protocol and their antibacterial efficacy. Rsc Advances 2014, 4(8), 3974–3983.

- Talib, Z.; et al. Frequency Behavior of a Quartz Crystal Microbalance (Qcm) in Contact with Selected Solutions. American Journal of Applied Sciences 2006, 3(5), 1853–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; et al. Electrochemiluminescence detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 based on a novel polydopamine surface imprinted polymer biosensor. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9(6), 5430–5436. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.D., R. Gangopadhyay, and A. De, Highly sensitive electrochemical biosensor for glucose, DNA and protein using gold-polyaniline nanocomposites as a common matrix. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2014, 190, 348–356.

- Kurra, N.; et al. Laser-derived graphene: A three-dimensional printed graphene electrode and its emerging applications. Nano Today 2019, 24, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.G.; et al. Mitochondria-targeted ROS-and GSH-responsive diselenide-crosslinked polymer dots for programmable paclitaxel release. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2021, 99, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Robby, A.I.; et al. GSH-responsive self-healable conductive hydrogel of highly sensitive strain-pressure sensor for cancer cell detection. Nano Today 2021, 39, 101178. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; et al. Facilely synthesized pH-responsive fluorescent polymer dots entrapping doped and coupled doxorubicin for nucleus-targeted chemotherapy. Journal of materials chemistry B 2017, 5(16), 2921–2930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kosasih, F.U.; et al. Nanometric chemical analysis of beam-sensitive materials: a case study of STEM-EDX on perovskite solar cells. Small Methods 2021, 5(2), 2000835. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; et al. Magnetic quantum dot based lateral flow assay biosensor for multiplex and sensitive detection of protein toxins in food samples. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 146, 111754. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. and C. Wang, Precise analysis of nanoparticle size distribution in TEM image. Methods and Protocols 2023, 6(4), 63.

- Pilot, R.; et al. A review on surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Biosensors 2019, 9(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; et al. Fluorescent turn-on sensing of bacterial lipopolysaccharide in artificial urine sample with sensitivity down to nanomolar by tetraphenylethylene based aggregation induced emission molecule. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2016, 85, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J. and S.Z. Hua, An overview of recent strategies in pathogen sensing. Sensors 2009, 9(6), 4483–4502.

- Xiao, L.; et al. Colorimetric biosensor for detection of cancer biomarker by Au nanoparticle-decorated Bi2Se3 nanosheets. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9(8), 6931–6940. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Carrión, C., B.M. Simonet, and M. Valcárcel, Colistin-functionalised CdSe/ZnS quantum dots as fluorescent probe for the rapid detection of Escherichia coli. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 26(11), 4368–4374.

- Shin, C.; et al. Rapid naked-eye detection of Gram-positive bacteria by vancomycin-based nano-aggregation. RSC advances 2018, 8(44), 25094–25103. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, G.; et al. Vancomycin-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles for selective recognition and killing of pathogenic gram-positive bacteria over macrophage-like cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013, 5(21), 10874–10881. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.S.; et al. Magnetic Extraction of Acinetobacter baumannii Using Colistin-Functionalized γ-Fe2O3/Au Core/Shell Composite Nanoclusters. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9(32), 26719–26730. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.S.; et al. Ultra-fast and universal detection of Gram-negative bacteria in complex samples based on colistin derivatives. Biomaterials science 2020, 8(8), 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khadka, N.K., C.M. Aryal, and J. Pan, Lipopolysaccharide-dependent membrane permeation and lipid clustering caused by cyclic lipopeptide colistin. ACS omega 2018, 3(12), 17828–17834.

- Chung, H.J.; et al. Ubiquitous detection of gram-positive bacteria with bioorthogonal magnetofluorescent nanoparticles. ACS nano 2011, 5(11), 8834–8841. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; et al. Structures of Staphylococcus aureus cell-wall complexes with vancomycin, eremomycin, and chloroeremomycin derivatives by 13C {19F} and 15N {19F} rotational-echo double resonance. Biochemistry 2006, 45(16), 5235–5250. [Google Scholar]

- Magar, H.S., R.Y. Hassan, and A. Mulchandani, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS): Principles, construction, and biosensing applications. Sensors 2021, 21(19), 6578.

- Berger, J.; et al. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase: a powerful new quantitative indicator of gene expression in eukaryotic cells. Gene 1988, 66(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; et al. Development of complex-shaped liver multicellular spheroids as a human-based model for nanoparticle toxicity assessment in vitro. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2016, 294, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.; et al. Development of a simple and convenient cell-based electrochemical biosensor for evaluating the individual and combined toxicity of DON, ZEN, and AFB1. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2017, 97, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbaied, T., A. Hogan, and E. Moore, Electrochemical Detection and Capillary Electrophoresis: Comparative Studies for Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Release from Living Cells. Biosensors 2020, 10(8), 95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, M.V.; et al. Optimizing blocking of nonspecific bacterial attachment to impedimetric biosensors. Sensing and bio-sensing research 2016, 8, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; et al. Simulation and experimental study of ion concentration polarization induced electroconvective vortex and particle movement. Micromachines 2021, 12(8), 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.J.; et al. Excellent quality microchannels for rapid microdevice prototyping: Direct CO 2 laser writing with efficient chemical postprocessing. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics 2019, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.-Y., B.-R. Li, and Y.-K. Li, Silicon nanowire field-effect-transistor based biosensors: From sensitive to ultra-sensitive. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2014, 60, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; et al. Graphene oxide signal reporter based multifunctional immunosensing platform for amperometric profiling of multiple cytokines in serum. ACS sensors 2018, 3(8), 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, H.A.M. and V. Zucolotto, Label-free electrochemical DNA biosensor for zika virus identification. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 131, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.V.; et al. Immittance electroanalysis in diagnostics. Analytical chemistry 2015, 87(2), 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.-M.; et al. Facile fabrication of a sensor with a bifunctional interface for logic analysis of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM)-coding gene. ACS Sensors 2016, 1(2), 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.-R.; et al. Rapid construction of an effective antifouling layer on a Au surface via electrodeposition. Chemical communications 2014, 50(51), 6793–6796. [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre, M.; et al. Identification of quinazolinone analogs targeting CDK5 kinase activity and glioblastoma cell proliferation. Frontiers in Chemistry 2020, 8, 691. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; et al. Polydopamine-based molecular imprinted optic microfiber sensor enhanced by template-mediated molecular rearrangement for ultra-sensitive C-reactive protein detection. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 387, 124074. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; et al. Antifouling sensors based on peptides for biomarker detection. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 127, 115903. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; et al. Electrochemical aptasensor for ultralow fouling cancer cell quantification in complex biological media based on designed branched peptides. Analytical chemistry 2019, 91(13), 8334–8340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; et al. Mixed self-assembled aptamer and newly designed zwitterionic peptide as antifouling biosensing interface for electrochemical detection of alpha-fetoprotein. ACS sensors 2017, 2(4), 490–494. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, H.K. and G. Basu, Conformational landscape of substituted prolines. Biophysical Reviews 2020, 12(1), 25–39.

- Goode, J., J. Rushworth, and P. Millner, Biosensor regeneration: a review of common techniques and outcomes. Langmuir 2015, 31(23), 6267–6276.

- Xu, M., X. Luo, and J.J. Davis, The label free picomolar detection of insulin in blood serum. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2013, 39(1), 21–25.

- Thangamuthu, M., C. Santschi, and O. JF Martin, Label-free electrochemical immunoassay for C-reactive protein. Biosensors 2018, 8(2), 34.

- Bing, X. and G. Wang, Label free C-reactive protein detection based on an electrochemical sensor for clinical application. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2017, 12(7), 6304–6314.

- Kim, C.-H.; et al. CRP detection from serum for chip-based point-of-care testing system. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2013, 41, 322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.H.; et al. AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistor-based biosensor for the detection of C-reactive protein. Sensors 2015, 15(8), 18416–18426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakanya, W.M. and I.E. Tothill, Detection of the inflammation biomarker C-reactive protein in serum samples: towards an optimal biosensor formula. Biosensors 2014, 4(4), 340–357.

- Lin, S.-C.; et al. A low sample volume particle separation device with electrokinetic pumping based on circular travelling-wave electroosmosis. Lab on a Chip 2013, 13(15), 3082–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-C.; et al. An in-situ filtering pump for particle-sample filtration based on low-voltage electrokinetic mechanism. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2017, 238, 809–816. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C., Y.-C. Tung, and C.-T. Lin, A frequency-control particle separation device based on resultant effects of electroosmosis and dielectrophoresis. Applied Physics Letters 2016, 109(5).

- Petsalaki, E.I.; et al. PredSL: a tool for the N-terminal sequence-based prediction of protein subcellular localization. Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics 2006, 4(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schägger, H. and G. Von Jagow, Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Analytical biochemistry 1987, 166(2), 368–379.

- Pagar, A.D.; et al. Recent advances in biocatalysis with chemical modification and expanded amino acid alphabet. Chemical Reviews 2021, 121(10), 6173–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; et al. A novel ECL biosensor for the detection of concanavalin A based on glucose functionalized NiCo2S4 nanoparticles-grown on carboxylic graphene as quenching probe. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2017, 96, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.L.; et al. Matrix effects demystified: Strategies for resolving challenges in analytical separations of complex samples. Journal of Separation Science 2023, 46(23), 2300571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, M.; et al. Serum biomarkers in patients with mesothelioma and pleural plaques and healthy subjects exposed to naturally occurring asbestos. Lung 2014, 192, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; et al. Droplet digital PCR as a novel system for the detection of microRNA-34b/c methylation in circulating DNA in malignant pleural mesothelioma. International journal of oncology 2019, 54(6), 2139–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pass, H.I.; et al. Fibulin-3 as a blood and effusion biomarker for pleural mesothelioma. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367(15), 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorino, C.; et al. Pleural Mesothelioma: Advances in Blood and Pleural Biomarkers. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(22), 7006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; et al. m 6 A mRNA methylation regulates CTNNB1 to promote the proliferation of hepatoblastoma. Molecular Cancer 2019, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; et al. Construction of a combined random forest and artificial neural network diagnosis model to screening potential biomarker for hepatoblastoma. Pediatric Surgery International 2022, 38(12), 2023–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, P.; et al. High STMN1 expression is associated with cancer progression and chemo-resistance in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2017, 24, 4017–4024. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; et al. A novel rapid quantitative method reveals stathmin-1 as a promising marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer medicine 2018, 7(5), 1802–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; et al. Inflammation factors in hepatoblastoma and their clinical significance as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2017, 52(9), 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mussa, A.; et al. Defining an optimal time window to screen for hepatoblastoma in children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Pediatric blood & cancer 2019, 66(1), e27492. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; et al. Assessment of survival of pediatric patients with hepatoblastoma who received chemotherapy following liver transplant or liver resection. JAMA network open 2019, 2(10), e1912676–e1912676. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H. and L.E. Locascio, Polymer microfluidic devices. Talanta 2002, 56(2), 267–287.

- Hotz, J.F.; et al. Evaluation of eosinophilic cationic protein as a marker of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Pathogens 2022, 11(2), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Sinner, W.N. , New diagnostic signs in hydatid disease; radiography, ultrasound, CT and MRI correlated to pathology. European journal of radiology 1991, 12(2), 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P. , Detection of specific circulating antigen, immune complexes and antibodies in human hydatidosis from Turkana (Kenya) and Great Britain, by enzyme-immunoassay. Parasite immunology 1986, 8(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Salah, E.B.; et al. Novel biomarkers for the early prediction of pediatric cystic echinococcosis post-surgical outcomes. Journal of Infection 2022, 84(1), 87–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; et al. Propofol Induces the Expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 in Echinococcus granulosus via the JNK and p38 Pathway In Vitro. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2023, 8(6), 306. [Google Scholar]

- Meoli, A.; et al. State of the Art on Approved Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) Modulators and Triple-Combination Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14(9), 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, B.S.; et al. Plasma sCD14 as a biomarker to predict pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 2014, 9(2), e89341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.-H.; et al. Optimal polymerase chain reaction amplification for preimplantation diagnosis in cystic fibrosis ((Delta) F508). BMJ 1995, 311(7004), 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, P.M. , Chloride impermeability in cystic fibrosis. Nature 1983, 301(5899), 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, C.Z.; et al. Skin biomarkers for cystic fibrosis: A potential non-invasive approach for patient screening. Frontiers in pediatrics 2018, 5, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.M.; et al. Early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening prevents severe malnutrition and improves long-term growth. Pediatrics 2001, 107(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeGrys, V.A.; et al. Diagnostic sweat testing: the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines. The Journal of pediatrics 2007, 151(1), 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P.; et al. An electrochemical sensing strategy for ultrasensitive detection of glutathione by using two gold electrodes and two complementary oligonucleotides. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2009, 24(11), 3347–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. , Electrochemical biosensors: towards point-of-care cancer diagnostics. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2006, 21(10), 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleček, E.; et al. Electrochemical biosensors for DNA hybridization and DNA damage. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 1998, 13(6), 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diren, A.; et al. Cytokine Profile in Patients With Maturity onset Diabetes of the Young. In Vivo 2022, 36(5), 2490–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acaralp, S. and H. Akhondi, Systematic Survey of Creatinine-Based Versus Cystatin C-based Estimated GFR in People with Diabetes. HCA Healthcare Journal of Medicine 2020, 1(4), 231–246.

- Seckinger, K.M.; et al. Nitric oxide activates β-cell glucokinase by promoting formation of the “glucose-activated” state. Biochemistry 2018, 57(34), 5136–5144. [Google Scholar]

- Demus, D.; et al. Interlaboratory evaluation of plasma N-glycan antennary fucosylation as a clinical biomarker for HNF1A-MODY using liquid chromatography methods. Glycoconjugate journal 2021, 38, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demus, D.; et al. Development of an exoglycosidase plate-based assay for detecting α1-3, 4 fucosylation biomarker in individuals with HNF1A-MODY. Glycobiology 2022, 32(3), 230–238. [Google Scholar]