Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

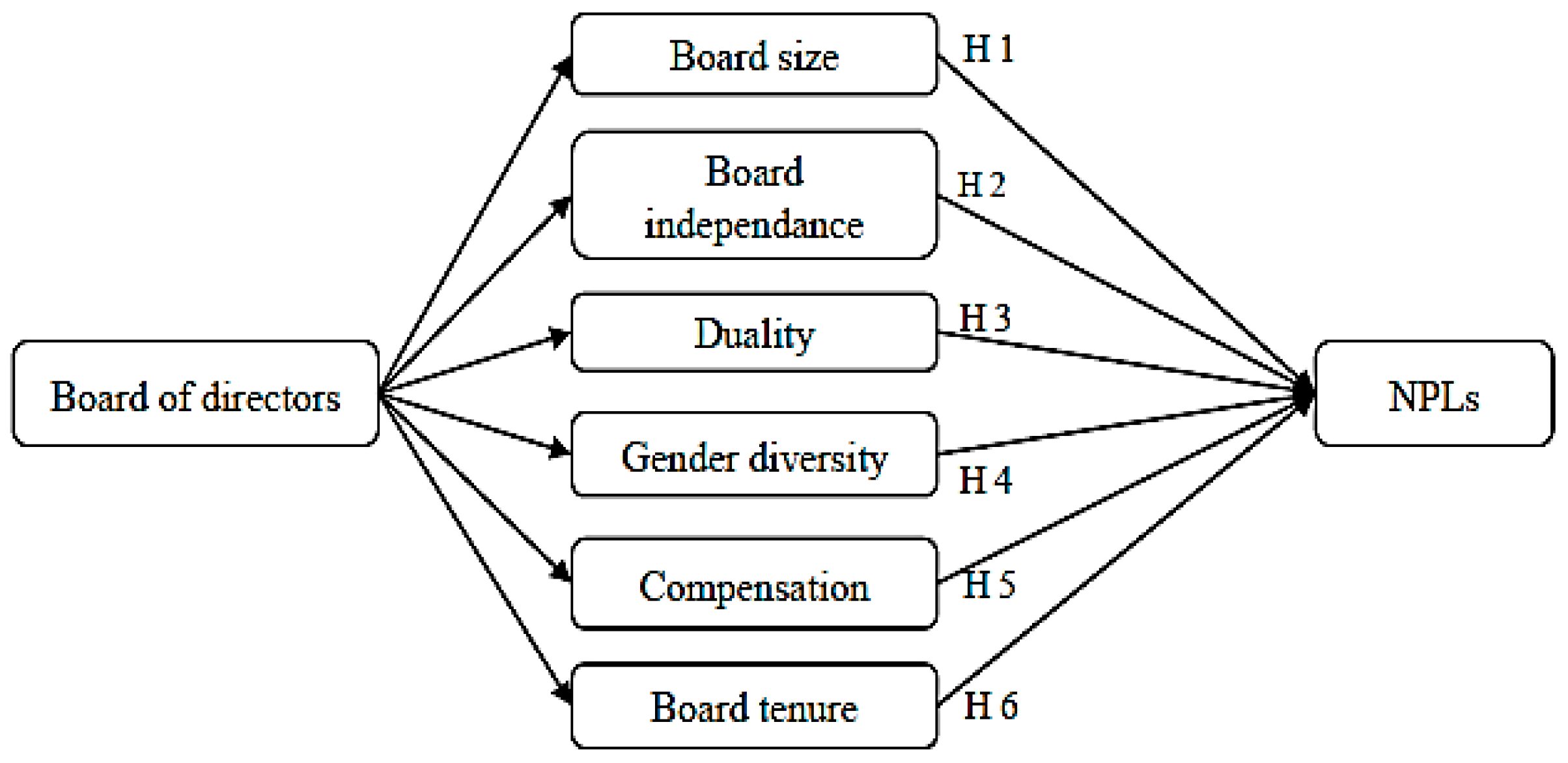

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Board Size and NPLs

2.2. Board Independence and NPLs

2.3. Duality and NPLs

2.4. Gender Diversity and NPLs

2.5. Board Tenure and NPLs

2.6. Board Compensation and NPLs

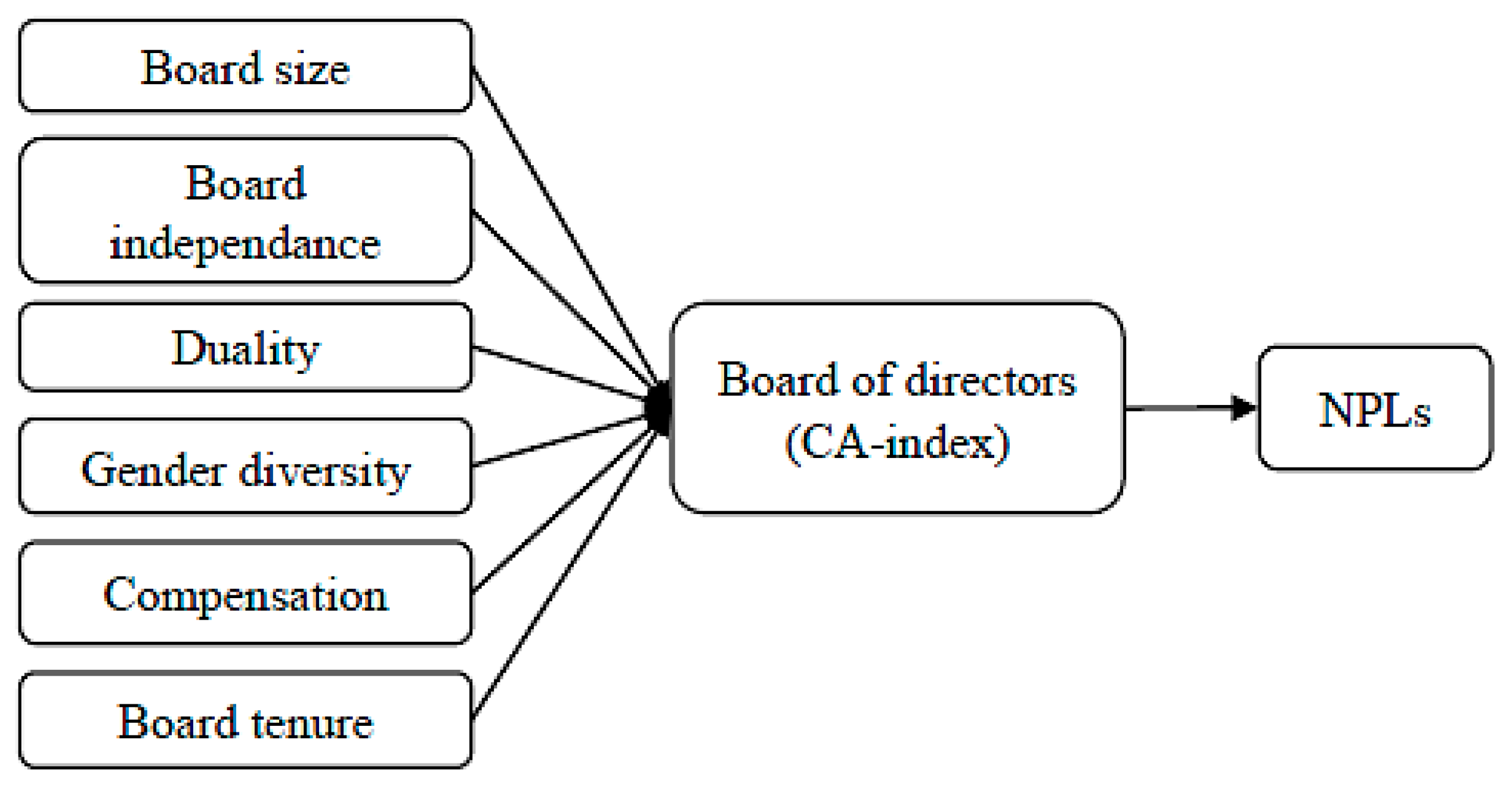

3. Methodology

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Empirical Approach and Model Specification

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Summary Statistics and Correlation Matrix

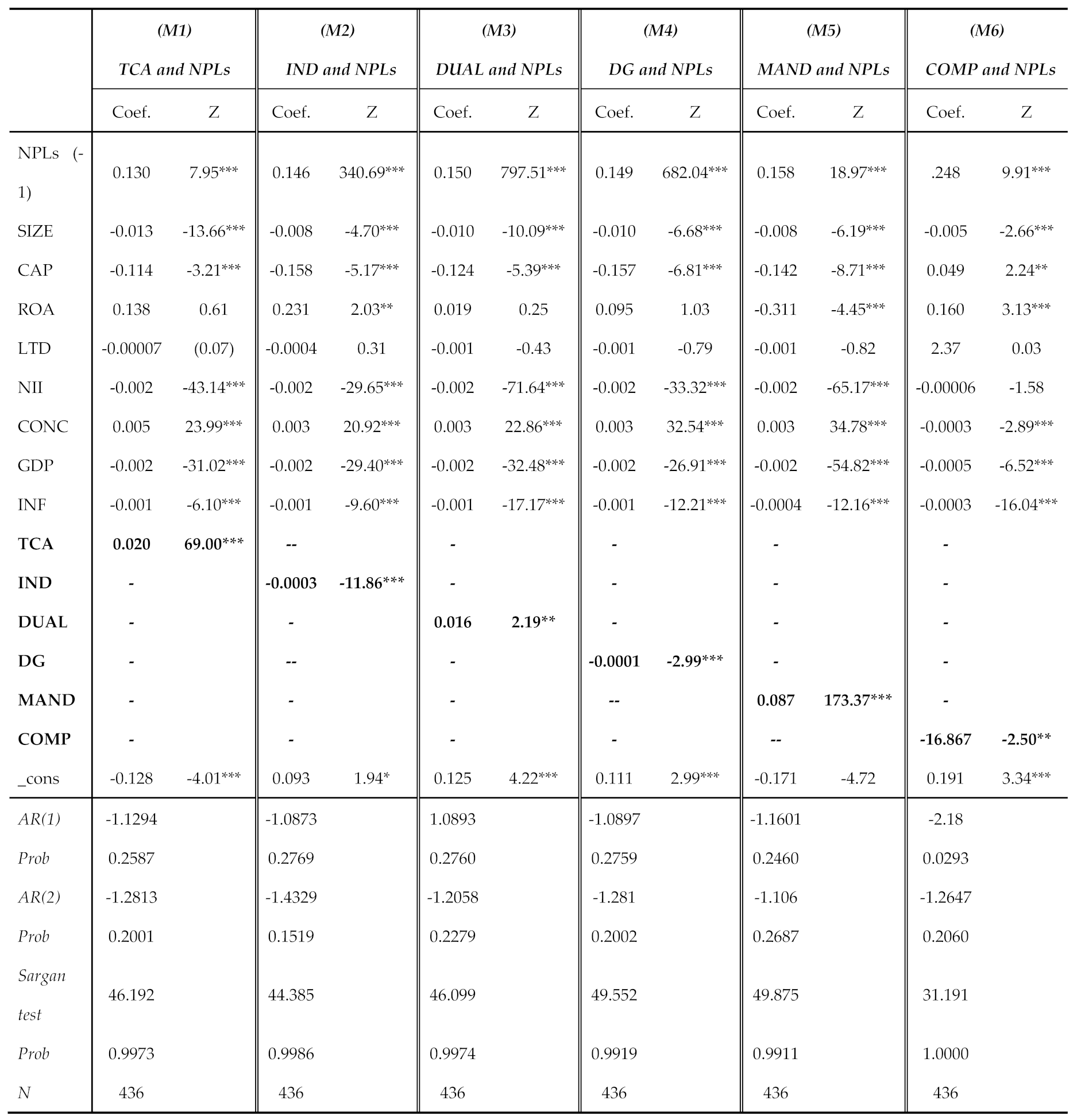

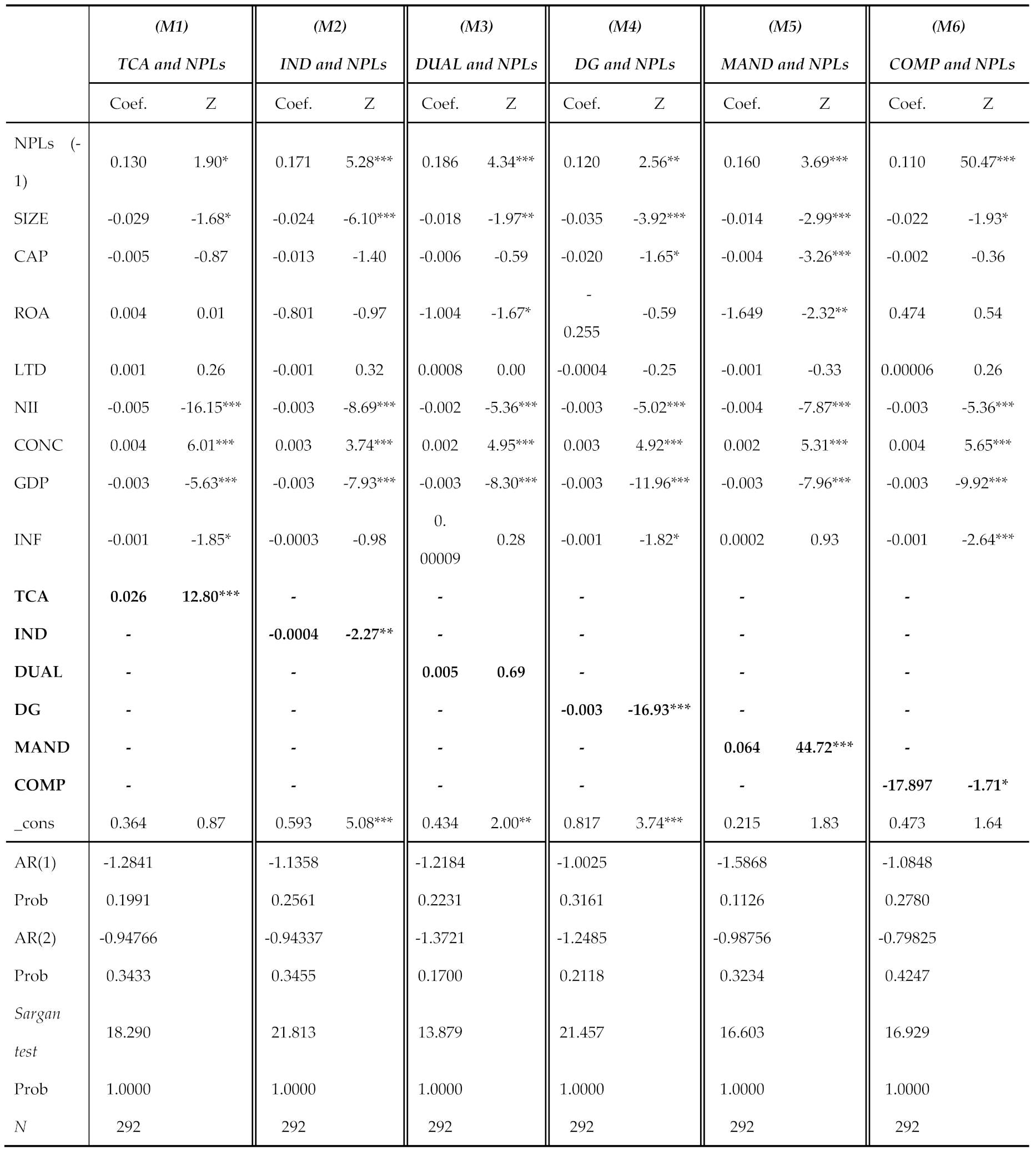

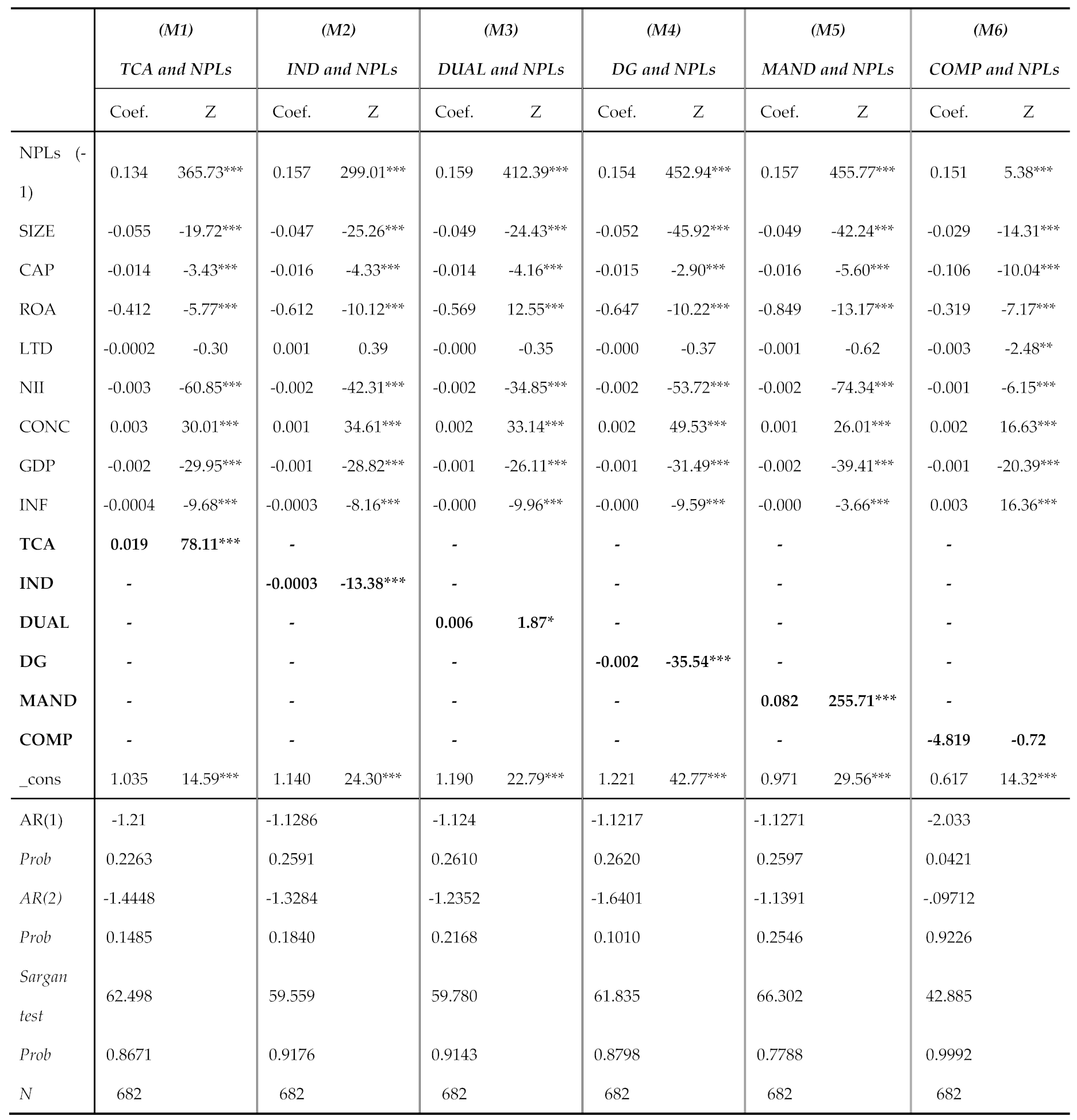

4.2. Discussion of the Empirical Findings

| MENA | GCC | NGCC | ||||

| Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | |

| NPLs (-1) | 0.156 | 313.48*** | 0.151 | 11.28*** | 0.104 | 2.28** |

| SIZE | -0.064 | -47.50*** | -0.028 | -15.77*** | -0.029 | -3.03*** |

| CAP | -0.017 | -8.75*** | -0.198 | -12.12*** | -0.017 | -1.76* |

| ROA | -0.787 | -12.53*** | -0.074 | -1.75* | -0.781 | -2.26** |

| LTD | -0.002 | 1.82 | -0.001 | -0.68 | -0.00001 | -0.01 |

| NII | -0.002 | -67.39*** | -0.001 | -27.27*** | -0.003 | -5.84*** |

| CONC | 0.002 | 43.96** | 0.003 | 32.00*** | 0.002 | 4.37*** |

| GDP | -0.001 | -39.08*** | -0.001 | -16.56*** | -0.003 | -4.49*** |

| INF | -0.000 | -5.09*** | -0.001 | -16.82*** | -0.000 | -2.07** |

| CA_index | -0.136 | -19.67*** | -0.094 | -8.20*** | -0.130 | -3.82*** |

| _cons | 1.476 | 40.63*** | 0.495 | 10.21*** | 0.709 | 3.21*** |

| AR(1) | -1.1312 | -1.1043 | -1.9127 | |||

| Prob | 0.2580 | 0.2694 | 0.0558 | |||

| AR(2) | -1.6633 | -1.3959 | -1.3593 | |||

| Prob | 0.0962 | 0.1627 | 0.1741 | |||

| Sargan test | 63.481 | 47.206 | 17.022 | |||

| Prob | 0.8467 | 0.9961 | 1.0000 | |||

| N | 682 | 436 | 292 | |||

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abid, A.; Gull, A.A.; Hussain, N.; Nguyen, D.K. Risk governance and bank risk-taking behavior: Evidence from Asian banks. J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 2021, 75, 101466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101466.

- Adusei, M.; Sarpong-Danquah, B. Institutional quality and the capital structure of microfinance institutions: the moderating role of board gender diversity. J. Institutional Econ. 2021, 17, 641–661, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744137421000023.

- Alnabulsi, K.; Kozarević, E.; Hakimi, A. Assessing the determinants of non-performing loans under financial crisis and health crisis: evidence from the MENA banks. Cogent Econ. Finance 2022, 10, 2124665. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2124665.

- Andres, P. & Vallelado. E. (2008) Corporate governance in banking: The role of the board of directors. Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 32, pp. 2570–2580.

- Bashir, U.; Yu, Y.; Hussain, M.; Wang, X.; Ali, A. Do banking system transparency and competition affect nonperforming loans in the Chinese banking sector?. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 1519–1525, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1305082.

- Beasley, M.S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 443–465.

- Bebchuk, L.A., & Spamann, H. (2009). Regulating Bankers’ Pay, Harvard Law and Economics Discussion Paper 641.

- Beltratti, A. & Stulz, R. M. (2009). Why Did Some Banks Perform Better during the Credit Crisis? A Cross- Country Study of the Impact of Governance and Regulation. Charles A Dice Center Working Paper No. 2009-12, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1433502.

- Berger, A.N.; Kick, T.; Schaeck, K. Executive board composition and bank risk taking. J. Corp. Finance 2014, 28, 48–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.11.006.

- Boussaada, R, Hakimi, A., & Karmani, M. (2020). Is there a threshold effect in the liquidity risk–nonperforming loans relationship? A PSTR approach for MENA banks. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 1‑13. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1002/ijfe.2248.

- Boussaada, R., & Labaronne, D. (2015). Ownership Concentration, Board Structure and Credit Risk: The Case of MENA Banks. Bankers, Markets & Investors.

- Boussaada, R., Ammari, A., & Ben arfa, N. (2018). Board characteristics and MENA banks’ credit risk : A fuzzy-set analysis. Economics Bulletin, 38, 2284-2303.

- Brewer, E., Hunter, W.C., & Jackson, W., E. (2004). Investment opportunity, product mix, and the relationship between bank CEO compensation and risk-taking. Working Paper n°36, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

- Byrd, J.; Cooperman, E.S.; Wolfe, G.A. Director tenure and the compensation of bank CEOs. Manag. Finance 2010, 36, 86–102, https://doi.org/10.1108/03074351011014523.

- Carter, C.B. & Lorsch, J. (2004). Back to the drawing Board: Designing corporate boards for a complex world. Harvard Business School Press.

- Chaibi, H.; Ftiti, Z. Credit risk determinants: Evidence from a cross-country study. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2015, 33, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.06.001.

- Chen, C.R.; Steiner, T.L.; Whyte, A.M. Does stock option-based executive compensation induce risk-taking? An analysis of the banking industry. J. Bank. Finance 2006, 30, 915–945, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.06.004.

- Daily, C.M. & Dalton, D.R. (1994). Corporate governance and the bankrupt firm: An empirical assessment. Strategic Management Journal, Wiley Blackwell, vol. 15(8), pages 643-654, October.

- DeYoung, R.; Torna, G. Nontraditional banking activities and bank failures during the financial crisis. J. Financial Intermediation 2013, 22, 397–421, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2013.01.001.

- Djebali, N.; Zaghdoudi, K. Corporate Governance in Banks and its Impact on Credit and Liquidity Risks: Case of Tunisian Banks. Asian J. Finance Account. 2019, 11, 148–168, https://doi.org/10.5296/ajfa.v11i2.13929.

- Doğan, B.; Ekşi, İ.H. The effect of board of directors characteristics on risk and bank performance: Evidence from Turkey. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2020, 6, 88–104, https://doi.org/10.18559/ebr.2020.3.5.

- Faccio, M., Marchica, M.T., & Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 193-209.

- Fernandes, J.G.; Olsson, I.A.S.; de Castro, A.C.V. Do aversive-based training methods actually compromise dog welfare?: A literature review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 196, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2017.07.001.

- Ghosh, A. Sector-specific analysis of non-performing loans in the US banking system and their macroeconomic impact. J. Econ. Bus. 2017, 93, 29–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2017.06.002.

- Golden, B.R.; Zajac, E.J. When will boards influence strategy? inclination × power = strategic change. Strat. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 1087–1111, https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.202.

- Golliard, J.T. & Poder, L. (2007). Optimal Capital Structure of capital in the banking sector.

- Hakimi, A., & Khemiri, M. A. (2024). Bank diversification and non-performing loans in the MENA region: The moderating role of financial inclusion. In Elsevier eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-44-313776-1.00204-x.

- Hakimi, A.; Boussaada, R.; Karmani, M. Is the relationship between corruption, government stability and non-performing loans non-linear? A threshold analysis for the MENA region. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2020, 27, 4383–4398, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2377.

- Hakimi, A.; Boussaada, R.; Karmani, M. Financial inclusion and non-performing loans in MENA region: the moderating role of board characteristics. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 2900–2914, https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2203456.

- Hassan, M.K.; Khan, A.; Paltrinieri, A. Liquidity risk, credit risk and stability in Islamic and conventional banks. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2019, 48, 17–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.10.006.

- Huang, S.; Hilary, G. Zombie Board: Board Tenure and Firm Performance. J. Account. Res. 2018, 56, 1285–1329, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679x.12209.

- Jabbouri, I., Naili, M., Almustafa, H., & Jabbouri, R. (2022). Does ownership concentration affect banks’ credit risk? Evidence from MENA emerging markets. Bulletin of Economic Research, 1‑22. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1111/boer.12345.

- Jenkins, H.; Alshareef, E.; Mohamad, A. The impact of corruption on commercial banks' credit risk: Evidence from a panel quantile regression. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2021, 28, 1364–1375, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2481.

- Jensen, C, M. (1993). The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems. In American Finance Association, The Journal of Finance: Vol. XLVIII (Issue 3, pp. 831–833).

- Jensen, C, M. (1993). The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems. In American Finance Association, The Journal of Finance: Vol. XLVIII (Issue 3, pp. 831–833).

- John, K., De Masi, S., & Paci, A. (2016). Corporate Governance in Banks. Corporate Governance: An International Review, (pp. 303–321), https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12161.

- John, K., De Masi, S., & Paci, A. (2016). Corporate Governance in Banks. Corporate Governance: An International Review, (pp. 303–321), https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12161.

- Karadima, M.; Louri, H. Non-performing loans in the euro area: Does bank market power matter? Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 2020, 72, 101593, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101593.

- Karismaulia, A., Ratnawati, K., & Wijayanti, R. (2023). The Effect of Macroeconomic and Bank-Specific Variables on Non-Performing Loans with Bank Size as A Moderating Variable. The International Journal of Social Sciences World, 5(1), 381-393.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8056076.

- Kervin, J.B. Kervin, J.B. (1992). Methods for business research. Harper Collins, New York.

- Kinateder, H.; Choudhury, T.; Zaman, R.; Scagnelli, S.D.; Sohel, N. Does boardroom gender diversity decrease credit risk in the financial sector? Worldwide evidence. J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 2021, 73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101347.

- Kramer, V.W., Konrad, A.M., & Erkut, S. (2006). Critical mass on corporate boards: Why three or more women enhance governance. Wellesley Center for Women, Report No. WCW 11.

- Kumar, R. R., Stauvermann, J. P., Patel, A., & Prasad, S. S. (2018). Determinants of non-performing loans in small developing economies: A case of Fiji’s banking sector. Accounting Research Journal, 1‑28. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-06-2015-0077.

- Lu, J.; Boateng, A. Board composition, monitoring and credit risk: evidence from the UK banking industry. Rev. Quant. Finance Account. 2017, 51, 1107–1128, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0698-x.

- Lückerath-Rovers, M. Women on boards and firm performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2013, 17, 491–509, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9186-1.

- Manz, F. Determinants of non-performing loans: What do we know? A systematic review and avenues for future research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2019, 69, 351–389, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00156-7.

- Massi, M. L. G. (2016). Effectiveness Of Best Practices in Corporate Governance in Combating Corruption. Revista Científica Hermes, 15–15, 122–141. https://doi.org/10.21710/rch.v15i0.268.

- Mohsni, S.; Otchere, I.; Shahriar, S. Board gender diversity, firm performance and risk-taking in developing countries: The moderating effect of culture. J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 2021, 73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101360.

- Muchemwa, M.R.; Padia, N.; Callaghan, C.W. Board composition, board size and financial performance of Johannesburg stock exchange companies. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 497–513, https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v19i4.1342.

- Naili, M.; Lahrichi, Y. The determinants of banks' credit risk: Review of the literature and future research agenda. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2020, 27, 334–360, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2156.

- Olaoye, F.O.; Adewumi, A.A. Corporate Governance and the Earnings Quality of Nigerian Firms. Int. J. Financial Res. 2020, 11, 161, https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v11n5p161.

- Park, J. Corruption, soundness of the banking sector, and economic growth: A cross-country study. J. Int. Money Finance 2012, 31, 907–929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2011.07.007.

- Pathan, S. Strong boards, CEO power and bank risk-taking. J. Bank. Finance 2009, 33, 1340–1350, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.02.001.

- Ploix. H. (2003). Bâle II et le capital-investissement. Revue d'Économie Financière, vol. 73(4), pages 189-200.

- Polat, A. Macroeconomic Determinants of Non-Performing Loans: Case of Turkey and Saudi Arabia. J. Bus. Res. - Turk 2018, 10, 693–709, https://doi.org/10.20491/isarder.2018.495.

- Post, C., Rahman. N., &Rubow. E. (2011). Diversity in the Composition of Board of Directors and Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility (ECSR), Business & Society 49 (forthcoming).

- Rose, C. The relationship between corporate governance characteristics and credit risk exposure in banks: implications for financial regulation. Eur. J. Law Econ. 2016, 43, 167–194, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9535-2.

- Salas, V. & Saurina, J. (2003). Deregulation, market power and risk behaviour in Spanish banks. European Economic Review, 47, 1061–1075.

- Saliba, C.; Farmanesh, P.; Athari, S.A. Does country risk impact the banking sectors’ non-performing loans? Evidence from BRICS emerging economies. Financial Innov. 2023, 9, 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00494-2.

- Sallemi, M.; Ben Hamad, S.; Ellili, N.O.D. Impact of board of directors on insolvency risk: which role of the corruption control? Evidence from OECD banks. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 17, 2831–2868, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00605-w.

- Setiawan, R.; Khoirotunnisa, F. The Impact of Board Gender Diversity on Bank Credit Risk. Int. J. Bus. Rev. (The Jobs Rev. 2020, 3, 47–52, https://doi.org/10.17509/tjr.v3i2.28158.

- Srairi, S.; Bourkhis, K.; Houcine, A. Does bank governance affect risk and efficiency? Evidence from Islamic banks in GCC countries. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manag. 2021, 15, 644–663, https://doi.org/10.1108/imefm-05-2020-0206.

- Sumner, S., & Webb, E., (2005). Does corporate governance determine bank loan portfolio choice ? Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, vol. 5, issue 2.

- Switzer, L.N.; Wang, J. Default Risk Estimation, Bank Credit Risk, and Corporate Governance. Financial Mark. Institutions Instruments 2013, 22, 91–112, https://doi.org/10.1111/fmii.12005.

- Tarchouna, A.; Jarraya, B.; Bouri, A. Do board characteristics and ownership structure matter for bank non-performing loans? Empirical evidence from US commercial banks. J. Manag. Gov. 2021, 26, 479–518, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09558-2.

- Vafeas, N. Length of Board Tenure and Outside Director Independence. J. Bus. Finance Account. 2003, 30, 1043–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. | |||||

| GCC countries | NGCC countries | ||||

| Countries | N | % | Countries | N | % |

|

1. Saudi Arabia 2. Bahrain 3. United Arab Emirates 4. Kuwait 5. Qatar 6. Oman |

10 2 11 7 7 5 |

14.28% 2.86% 15.71% 10% 10% 7.14% |

7. Egypt 8. Jordan 9. Lebanon 10. Morocco 11. Tunisia 12. Turkey |

3 4 1 2 10 8 |

4.28% 5.71% 1.43% 2.86 14.28% 11.43% |

| Total | 42 | 60% | Total | 28 | 40% |

| Variables | Definitions | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| NPLs | Non-performing loans | Non-performing loans to total loans ratio (%). |

| Board characteristics | ||

| TCA | Board size | Total number of directors within a Board of Directors |

| IND | Independent directors | Proportion of independent directors on a Board of Directors |

| DUAL | Duality | Binary variable takes 1 if the CEO is the Chairman of the Board, 0 otherwise. |

| BGD | Gender diversity | Women on the Board as a percentage of the total number of directors. |

| MAND | Board Tenure | The term length of a Board of Directors. |

| COMP | Compensation | Total compensation of directors in US dollars relative to total assets (%). |

| CA_INDEX | Board characteristics index | Composite index of board characteristics based on the PCA method, ranging from 0 to 1, with '1' indicating an effective board and '0' otherwise. |

| Control variables | ||

| SIZE | Bank size | The natural logarithm of the total assets of each bank |

| CAP | Capital | Equity to total assets (%). |

| LTD | Liquidity risk | Loan-to-deposit ratio, (%). |

| ROA | Bank performance | Return on assets (ROA), (%) |

| NII | Bank diversification | Non-interest income as a percentage of total assets. |

| CONC | Concentration | The share of the five biggest banks' assets to all banks' assets (%). |

| GDP | Economic growth | Annual GDP growth rate, (%) |

| INF | Inflation rate | Annual growth of CPI, (%) |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPLs | 7.3 | 1.8 | 4.01 | 261 |

| TCA | 10.52 | 1.95 | 5.02 | 19 |

| IND | 28.81 | 23.48 | 13.1 | 100 |

| DG | 6.62 | 8.41 | 1.4 | 40 |

| MAND | 3.10 | 0.59 | 1 | 6 |

| COMP | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.18 |

| SIZE | 23.74 | 1.22 | 20.94 | 26.51 |

| CAP | 16.7 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 42.9 |

| ROA | 1.4 | 0.8 | -3.8 | 6.3 |

| LTD | 98.76 | 5.84 | 1.4 | 162 |

| NII | 38.44 | 17.26 | 9.55 | 96 |

| CONC | 82.20 | 13.36 | 56.04 | 100 |

| GDP | 3.12 | 4.07 | -2.4 | 19.59 |

| INF | 4.83 | 10.96 | -3.75 | 29.5 |

| DUAL | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 599 | 87.79% |

| 1 | 83 | 12.21% |

| Total | 682 | 100% |

| NPLs | TCA | IND | DUAL | DG | MAND | COMP | SIZE | CAP | ROA | LTD | NII | CONC | GDP | INF | |

| NPLs | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||||

| TCA | 0.2801* | 1.0000 | |||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||||||||||

| IND | -0.1264* | -0.0729 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||

| (0.0023) | (0.0790) | ||||||||||||||

| DUAL | 0.0562 | 0.1680* | -0.0999* | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| (0.1765) | (0.0000) | (0.0147) | |||||||||||||

| DG | 0.2524* | 0.2375* | -0.1397* | -0.0833* | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0007) | (0.0428) | ||||||||||||

| MAND | -0.0235 | 0.0537 | -0.1279* | 0.3443* | -0.0853* | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| (0.5765) | (0.2014) | (0.0020) | (0.0000) | (0.0407) | |||||||||||

| COMP | 0.1480* | -0.0474 | -0.2020* | 0.1559* | 0.3829* | -0.0748 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| (0.0111) | (0.4169) | (0.0005) | (0.0072) | (0.0000) | (0.2066) | ||||||||||

| SIZE | -0.1867* | -0.0606 | 0.0904* | 0.1377* | -0.3643* | 0.0912* | -0.5102 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.1662) | (0.0376) | (0.0015) | (0.0000) | (0.0380) | (0.0000) | |||||||||

| CAP | -0.1057* | -0.0414 | 0.1254* | 0.0712 | -0.1474* | 0.2518* | -0.3640* | 0.1943* | 1.0000 | ||||||

| (0.0023) | (0.3213) | (0.0024) | (0.0843) | (0.0004) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000 | ||||||||

| ROA | -0.1725* | -0.0358 | -0.0224 | -0.0530 | 0.0695 | -0.0307 | 0.1635* | 0.1648*) | 0.0823* | 1.0000 | |||||

| (0.0000) | (0.3876) | (0.5854) | (0.1956) | (0.0910) | (0.4591) | (0.0048) | (0.0000 | (0.0149) | |||||||

| LTD | -0.0520 | 0.0380 | -0.0515 | -0.0430 | 0.1046* | -0.0191 | -0.0184 | -0.0411 | 0.0197 | 0.0950* | 1.0000 | ||||

| (0.1298) | (0.3617) | (0.2136) | (0.2980) | (0.0116) | (0.6478) | (0.7524) | (0.2804) | (0.5680) | (0.0050) | ||||||

| NII | -0.0016 | 0.0723 | -0.0744 | 0.0164 | -0.1013* | 0.3225* | -0.1536* | 0.3106* | 0.1425* | -0.0791* | 0.0853* | 1.0000 | |||

| (0.9643) | (0.0814) | (0.0699) | (0.6902) | (0.0138) | (0.0000) | (0.0083) | (0.0000) | (0.0001) | (0.0256) | (0.0176) | |||||

| CONC | -0.2255* | -0.3393* | 0.2763* | -0.1467* | -0.4319* | 0.0805 | -0.5140* | 0.2194* | 0.2336* | -0.0099 | -0.1181* | -0.0298 | 1.0000 | ||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0004) | (0.0000) | (0.0538) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.7689) | (0.0006) | (0.4088) | ||||

| GDP | -0.0666 | 0.1410* | -0.0188 | 0.0578 | 0.0442 | 0.0737 | - 0.0813 | 0.0757* | 0.0386 | 0.3077* | 0.0578 | 0.1127* | -0.0360 | 1.0000 | |

| (0.0521) | (0.0006) | (0.6469) | (0.1586) | (0.2834) | (0.0758) | (0.1632) | (0.0462) | (0.2547) | (0.0000) | (0.0885) | (0.0014) | (0.2879) | |||

| INF | 0.0638 | 0.1093* | 0.0283 | 0.0279 | 0.1209* | -0.2337* | 0.3666* | 0.0022 | -0.0548 | 0.1216 | 0.0732* | -0.0661 | -0.2669* | 0.0281 | 1.0000 |

| (0.0625) | (0.0082) | (0.4898) | (0.4954) | (0.0032) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.9533) | (0.1054) | (0.0002) | (0.0309) | (0.0622) | (0.0000) | (0.3981) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).