1. Introduction

Cellular injury represents a complicated interplay of physiological occurrences that highlights the complex response of cells to a range of stressors. Understanding the mechanisms that drive cellular adaptations is critical given that these adaptations lay the groundwork for identifying pathological alterations in tissues. Cells have some new anticsincluding atrophy, hypertrophy, metaplasia, hyperplasia, and dysplasiain to maintain the stability of the internal environment when facing a dogfight [

1]. However, if these measures are unsuccessful, injury can be expected under the aegis of free radical T in general and hypoxia itself more specifically. Free radical injury, often potentiated by pollutants in ambient air, creates orthospecies that can cause lasting damaging effects on cells [

2]. Hypoxia, characterized by a reduced oxygen supply, leads to a decrease in ATP production, an indispensable energy source, resulting in disruption of ion homeostasis and ensuing cellular swelling, attributable to the accumulation of sodium and water [

3]. This chain reaction underscores the significance of prompt interventions aimed at preventing irreversible injuries and potential necrosis, which may have extensive implications for overall health.

The ramifications of cellular injury go beyond single cells, significantly affecting the health of tissues as well as the functioning of organs [

4]. A thorough understanding of the various mechanisms underlying cellular injury is essential for the accurate diagnosis and management of numerous diseases in an effective manner. Identifying preliminary signs indicative of reversible injury can assist clinicians in making decisions regarding interventions, which may prevent irreversible injury that leads to cell death and consequent organ failure. Additionally, expounding on the influence of free radicals and hypoxia in relation to cell injury contributes to the understanding of pathophysiological processes that are essential to conditions such as ischemia and inflammation [

5]. Recognizing the complex interactions between cell injury and its physiological implications, clinicians are better prepared to handle the challenges associated with disease management and patient care.

Understanding the mechanisms underlying cellular injury is important for both clinical applications and the forward drive of biomedical research. The aim of this review was to investigate the diverse varieties of cellular adaptation and the pathophysiological processes that follow when injury occurs, including phenomena such as atrophy, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, metaplasia, and dysplasia. A thorough analysis of the various types of injury, mainly those caused by free radicals and hypoxia, will reveal how such elements disrupt the standard operations of cells, resulting in outcomes such as cellular swelling or necrosis. In addition, this review endeavors to clarify the differences between reversible and irreversible cellular injury, with a focus on medical treatment ramifications and comprehension of diseases. By underscoring the factors that affect cellular injury and the potential for recovery, this review aims to improve the understanding of pathophysiological alterations, ultimately contributing to the development of better therapeutic approaches. Achieving these aims is critical for developing interventions that can lessen cellular harm and foster recovery.

2. Definition of Cellular Injury

Beyond what is normal, cellular damage merges various operations that undercut structural integrity and existence; injuries resulting only secondarily from infection can enlarge these varied processes. There are also endless adaptations in this type, such as atrophia, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia ways of life. The common between all of them is that they form dysplasias, which can arise as responses _____ to harmful environments or injuries [

1]. While certain adaptations might be reversible, others could be irreversible, especially as seen in necrosis [

6]. Frequently, the mechanisms that lead to cellular injury involve ROS production of reactive oxygen species. When these complex structures go wrong, they can cause harmful factors such as harmful molecules or hypoxia, leading to hypoxic conditions in which there is not enough energy flowing through the cell to make ATP possible either--all doomed outcomes for cells and structures as big as our own bodies [

7]. Understanding that quite significant cellular injury is not just caused by nervous neural cells, how then could results go in the extreme opposite to medical intervention actually causing normal damage?

3. Overview of Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Relevance to Disease Processes

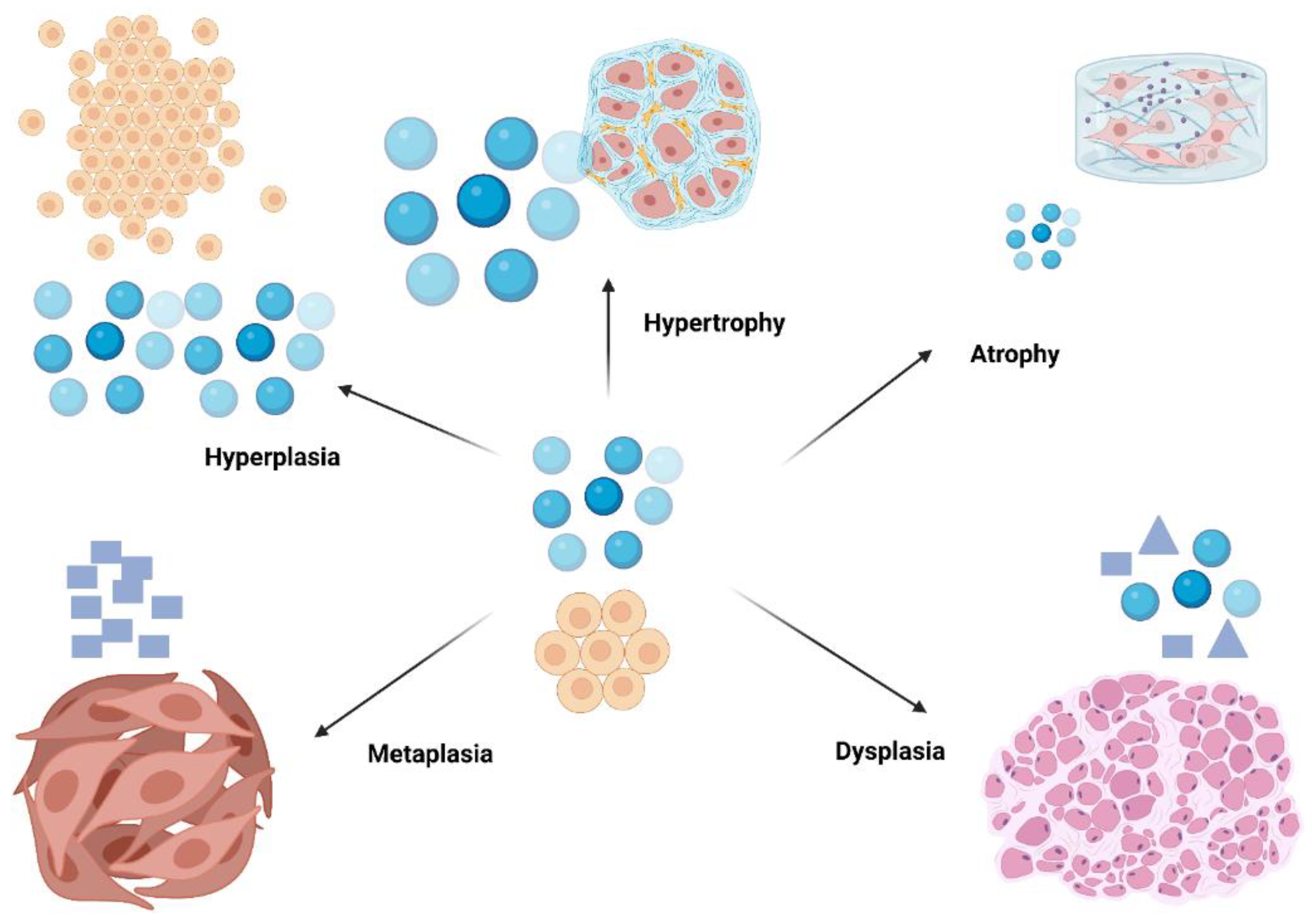

Within the body, cells are always influenced by many kinds of stimuli, whether they come from the inside or the outside. This may also cause cells to respond in ways that are good for themselves or that influence their flavor. There are many different cellular processes during pathology that result from trauma. Cells might undergo atrophy or hypertrophy, enter a hyperplastic state, undergo metaplasia in response to injury, and then transform to dysplasia in an attempt to exit from the path they are on (

Figure 1) [

8].

To illustrate, atrophy signifies a reduction in the size of cells, which may occur because of a decrease in workload or inadequate nutrient supply. On the other hand, hypertrophy signifies an enlargement in cell size that arises from increased demand, a phenomenon often seen in muscle tissues, particularly during periods of exercise [

8]. Alternatively, hyperplasia results in an increase in cell quantity, as observed by particular hormonal activities (

Figure 1). Hypoxic injury indicates the importance of oxygen supply; it terminates in reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and ensues cellular swelling due to ionic imbalances, thereby emphasizing the relationship between environmental stressors and cellular dysfunction [

9]. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for devising therapeutic interventions aimed at reducing cellular injury and promoting recovery.

Cellular injury is of fundamental importance in the progression of numerous disease mechanisms, especially in scenarios characterized by ischemia or oxidative stress. The underlying mechanisms associated with such injuries are primarily outlined by alterations that can be either reversible or irreversible and have the potential to result in notable clinical consequences [

10]. For example, injury caused by free radicals, which arise from metabolic activities and external factors, leads to harm across different cellular structures, thereby disturbing homeostasis. In patients with post-cardiac arrest brain injuries, the course of events following ischemic depolarization is definite progression. When untreated, this inevitably leads to the mutual death of neurons [

11]. Similarly, in the neurodegenerative pathology seen in Parkinson’s disease, there are many examples of malfunction within human cells that are incorporated into the tissue and can greatly increase symptoms, which underlines how medical intervention must be tightly focused [

12]. Understanding these mechanisms not only helps clarify the multifaceted nature of diseases but also underscores the pressing need for early intervention and preventive measures in medical care.

4. Types of Cellular Injury

4.1. Reversible Versus Irreversible Injury

In the pathophysiological domain, the differences between reversible and irreversible cellular injuries have vital significance. Reversible injury occurs when cells can return to homeostasis following stress has been resolved; a phase often marked by phenomena such as cellular swelling or fatty deposition in response to hypoxia or damage induced by free radicals show that this is how well adapted and clever organisms operate under pressure [

13].

Yet once injury becomes persistent or exceeds a certain limit, one sees the transformation of such reversible damage into irreparable harm which brings onto pathological processes like necrosis (major cell death) and/or apoptosis (programmatic cell death) actually sets up an irreversible situation. Cellular death occurs with irreversible injury, followed directly by tissue impairment of a subsequent nature that alters the function of the entire organ involved [

14].

Intrigues observed in cases of severe hypoxia include a decrease in ATP synthesis, exacerbating intracellular swelling and leading to an acidotic environment that threatens cellular integrity [

15]. Consequently, the classification of injury to cellular structures documents a continuum from which it should be emphasized that rapid intervention might prevent irreversible damage. In other words, early diagnosis and treatment of disease conditions are critical in clinical practice [

16].

4.2. Acute Versus Chronic Cellular Injury

On the other hand, chronic cellular injury develops more slowly, often because of extended exposure to damaging agents, which leads to adaptations such as hypertrophy or hyperplasia, as the cells try to sustain homeostasis. This swift occurrence can trigger inflammation and subsequent healing processes, which, although vitally important for recovery, might also induce additional cellular strain if the original injury is not addressed [

17]. Chronic injury often results in maladaptive modifications such as fibrosis or dysplasia, potentially making cells more susceptible to malignancy [

18]. Thus, identifying the distinction between these types is vital for comprehending the pathophysiological results and informing therapeutic approaches.

5. Hypoxic Injury and Its Implications

Cellular metabolism is fundamentally dependent on the presence of oxygen, which is why injuries caused by low oxygen levels, or hypoxia, can pose serious threats to the integrity of tissues [

19]. When cells encounter a scarcity of oxygen, there is a notable reduction in the production of ATP, which disrupts the balance of ions, resulting in the accumulation of sodium and water inside the cells, thereby leading to cellular swelling and possible rupture [

20]. Additionally, the transition toward anaerobic metabolism generates lactic acid, which can lead to a significant drop in pH, further worsening cellular damage. The implications of this process are especially severe for tissues with high metabolic rates, including the brain, where irreversible injury may manifest within a few minutes of a lack of oxygen, highlighting the critical need for swift medical intervention [

21]. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms underlying hypoxic injury is crucial, as such conditions can initiate irreversible cell death, thereby amplifying the overall detrimental effects on organ systems and resulting in complications such as gangrene [

22]. Therefore, timely recognition and restoration of the oxygen supply are imperative to reduce these harmful outcomes.

6. Chemical Injury and Toxic Agents

Exposure to a variety of toxic agents can trigger notable changes in the functioning and survival of cells, frequently resulting in irreversible damage. Notably, chemical agents arising from environmental pollutants, industrial substances, or excessive pharmaceutical intake can cause cellular impairment via several different routes [

23]. For example, free radicals resulting from these toxic substances can inflict harm on cellular membranes and genetic material, thus setting off a chain reaction marked by oxidative stress that disrupts normal metabolic functions and leads to cellular dysfunction [

23].

Furthermore, some toxic agents can elicit specific biological responses, such as apoptosis or necrosis, which are contingent on factors such as the concentration and duration of exposure. The buildup of lactic acid due to anaerobic metabolism, particularly a potential result of hypoxic conditions or worsened by the presence of toxins, can result in acidotic environments that are harmful to cellular stability [

24].

In summary, the work of chemicals in biological systems and the body’s response to these agents underscores the importance of toxicology, a skillful science in its own right; both from this standpoint is not just that we should study all kinds developed by man as well traditional medicines; we have a bent Simply thinking about this goes a long way toward coming up with ideas for action, prevention, and therapeutics to lessen cellular injury.

7. Infectious Agents and Cellular Damage

The function of infectious agents and the cellular injury it causes is a typical aspect of pathophysiology. Many kinds of pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi (and others), can cause injury to cells by various means, resulting in extensive damage to tissues and organ systems, as well as specific dysfunction [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. For example, certain bacterial species produce exotoxins that interfere with cellular operations, whereas viruses effectively command the host’s cellular machinery to propagate, eventually leading to cell rupture and demise [

35].

Furthermore, the immune response triggered by infections may worsen cellular harm, and although inflammation is crucial for the eradication of these pathogens, it can also inflict unintended damage as immune cells discharge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteolytic enzymes [

36]. In addition to expulsion of infectious agents, the host cellular structure itself must be safeguarded, which holds the highest expectations. For should damage not be resolved earlier, its evolution could grow out of control and therefore resemble irreversible injury-like necrosis.Thus recovery becomes even more problematic, although this does not contradict the possibility that it may also contribute inch-wastingly towards the pathogenesis of associated diseases [

36]. Gaining insights into these interactions is important for the formulation of effective therapeutic modalities.

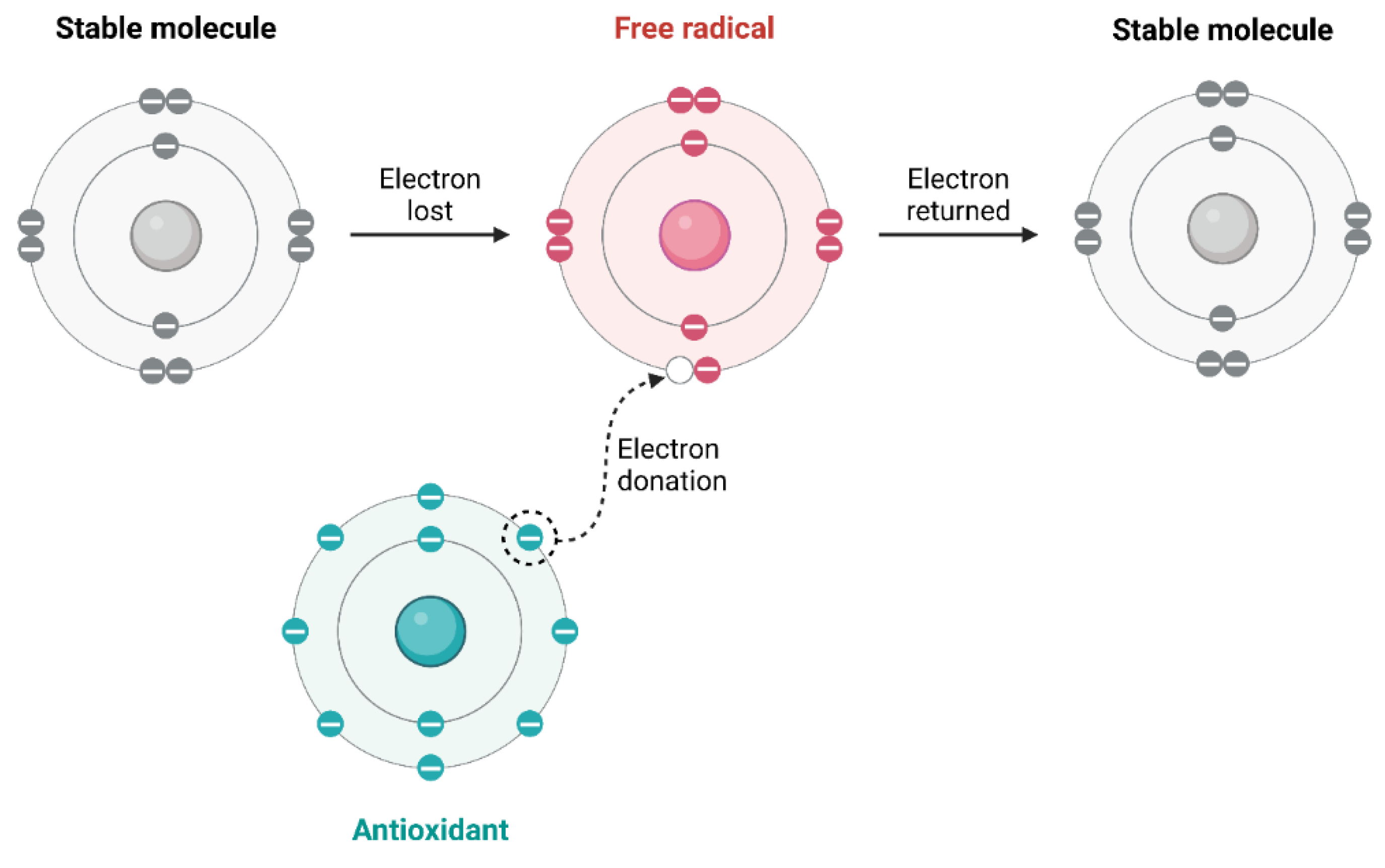

8. Physical Agents Causing Cellular Injury

Among various environmental and physical agencies, coming together to hurt cell damage is vitally important. This occurs mainly through processes that upset the natural balance of life within cells. Generated primarily from environmental conditions, such as pollution and ultraviolet radiation, free radicals have a greater effect on cellular antioxidant defenses. This leads to oxidative stress and the possibility of injury to cells (

Figure 2) [

37]. Additionally, physical forces and extreme temperatures can prompt immediate responses at the cellular level, leading to structural impairments. For instance, injuries due to trauma can cause direct damage, whereas physiological reactions of the body can cause secondary injuries that aggravate the original harm [

38]. Adaptations may occur in different forms, indicating their vulnerability to varying environmental conditions [

8]. This complex interaction among these elements highlights the need for effective therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing the impact of physical agents on cellular well-being and illustrating the pathophysiological consequences associated with such injuries.

9. Mechanisms of Cellular Injury

Cellular injury occurs in several ways, including free radical damage and low oxygen levels. Free radicals are reactive molecules that are produced during metabolism or originate from the environment. They can initiate a series of oxidative stress reactions that harm various cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and DNA [

39]. When this happens, it usually undermines the cell’s structure and how it works, often leading to cell death if the damage is sufficiently severe. In contrast, hypoxia, which refers to a lack of oxygen, results in a notable decrease in ATP production, disturbing the balance of ions within the cell. This disruption mainly concerns sodium and water, which cause the cells to swell because these substances build up inside [

39]. In addition, shifting to anaerobic metabolism results in lactic acid build-up, which lowers intracellular pH and worsens cellular damage [

40]. Understanding these mechanisms is vital for clarifying the pathophysiology of cellular injury and its role in tissue survival.

9.1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Cellular well-being is fundamentally conditional on the adequate operation of mitochondria, often called the powerhouse of the cell, which is primarily responsible for the production of ATP. Abnormalities in mitochondrial function may substantially lead to cellular harm, frequently resulting in damage that cannot be reversed [

41].

Mitochondrial dysfunction can emerge from a multitude of factors, such as oxidative stress, which produces free radicals that compromise the integrity of mitochondria, in addition to hypoxic environments that reduce ATP generation, consequently impacting cellular metabolism and ion equilibrium. This kind of disruption sets off a chain of events, producing a sustained swelling of the cell--one that cannot be stopped until its cause (the disturbed balance between sodium and water) has been corrected, which means the state energy is compromised [

42]. Long-term damage to mitochondria does not occur only within the context of acute cellular injury; it also lies at the heart of degenerative diseases, and its role in both health and pathology is indispensable [

43]. An understanding of mitochondrial damage mechanisms and their effects is fundamental for the development of rationally targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring cellular integrity.

9.2. Disruption of Cellular Membranes

Cell injury is frequently indicated by disruption of cell membranes, which is essential for sustaining cellular integrity and function. When cell membranes are subjected to various inhospitable factors, such as the formation of free radicals or lack of oxygen, their permeability increases, and the regulatory capacity of the environment within them risks being lost. This change results in an increase in sodium and water volume in a cell, swelling it; this is generally recognized as a reversible injury. As a result, while ion gradients dissipate and production is reduced by ATP, the selectivity for passage of materials across the membranes further diminishes, rendering them increasingly open to permanently damaging acts [

44]. In situations of irreversible damage, such as extended hypoxia, lysosomal membranes can rupture and release hydrolytic enzymes. These plains extend necrosis, that is, uncontrolled cell death, leading to greater injury [

45]. Understanding the dynamics of cellular membranes is vital for comprehending the complications caused by cellular injury because the extent of damage to them is crucial in determining whether a particular state will culminate in pathological chronic disease.

9.3. Impaired Protein Synthesis

Protein synthesis is essential for preserving cellular function; however, various causes of cellular injury greatly interfere with this crucial process. Under hypoxic or oxidative stress conditions, essential components necessary for protein synthesis, including RNA and ribosomes, may be impaired. This not only handicaps the cell’s capability to generate essential proteins, but also its vital life functions. However, it can also induce cell architecture and enzyme function failures, thus giving rise to abnormal growth phenomena such as hypertrophy or dysplasia [

46]. Furthermore, inadequate ATP during times of nutritional deprivation or metabolic disturbances prevents energy-dependent processes. This greatly impedes the synthesis of proteins necessary for health, and may lead to serious pathological problems [

47]. Ultimately, the impaired state of protein synthesis represents both immediate cellular dysfunction and potential longer-lasting effects, such as apoptosis or necrosis if the primary lesion is not dealt with [

48].

9.4. Altered Calcium Homeostasis

Disturbance of calcium levels within cells is important for the advancement of cellular harm, resulting in a range of pathological consequences. When homeostasis is altered, an overabundance of intracellular calcium can initiate a series of harmful enzymatic actions, such as those involving proteases and endonucleases, which aid in cellular deterioration and apoptosis [

49]. This abnormal increase in calcium levels is frequently related to different factors, including hypoxia, oxidative stress, or ischemic conditions, stimulating the release of stored calcium from the mitochondria into the cytosol [

50].

An imbalance in calcium homeostasis reduces ATP generation and leads to cellular swelling by disturbing ion equilibrium. This is due to energy-dependent ion pump dysfunction causing sodium entry to slow down again.Finally, a sustained calcium overload ends in irreversible damage, which can take various forms: Necrosis results from complete cell death local to an area, also adding insult to tissue injury and impairing organ function Moreoverit is important to sustain the balance of circulating calcium It stands to reason that for the body to work normally, this must be attained on cellular level as well as extracellularly. Any maladjustment in homeostatic mechanisms or regulatory processes could change the outcome of damage right down to what kind of tissue remains [

51].

10. Clinical Implications of Cellular Injury

The consequences of cellular injury are not confined to a single cell. They reach out and influence existence at different levels such as tissue stability, organ function, and overall patient health. For example, within cells, reversible or irreversible adaptations are responsible for some of the differences in clinical results. This is particularly evident in conditions such as heart failure, where myocardial hypertrophy may lay the groundwork on which negative consequences will follow [

52]. Free radical injury and hypoxic injury--meaning comprehensive knowledge of the many types with which cells can be wounded–are essential in a practical sense so that treatments might focus specifically on what is wrong instead of general relief [

53]. Free radicals are introduced into the cell from metabolic processes and other environmental factors, leading to injury in cells and inflammation, which in turn causes complications for recovery. In another example of hypoxia, loss of ATP production immediately causes top-level problems such as cell death, which will be irreversible if not acted upon quickly [

54]. Hence, a proper understanding of the clinical effects of cellular injury not only provides guidelines for treatment, but also indicates how urgent it becomes to intervene early so that the resulting problems can be mitigated.

10.1. Cellular Injury in Ischemic Heart Disease

The balance between oxygen supply and demand is upset and this cellular metabolic disorder exhibits many signs of ischemic heart disease. The basic pathophysiological change is that because there is no oxygen to supply, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy molecule in short supply under hypoxia, suffers a marked drop in production. This disturbs ionic equilibrium within individual heart cells [

55]. Consequently, there is an intracellular buildup of sodium and water, which leads to cellular swelling, which is a key indicator of early reversible injury. If the ischemic state continues, this situation may progress to irreversible injury. This is particularly observable through the accumulation of lactate resulting from anaerobic metabolic processes, which induces acidosis and additional metabolic derangement. The delicate balance is most readily upset in the myocardium, where necrosis can occur within a few minutes. Ultimately, this leads to tissue damage and destructive structural changes (remodeling) of the heart. Knowledge of these processes is crucial, as they dictate what can be achieved in therapies aimed at reestablishing blood flow and reducing cell damage during ischemic heart disease [

55].

10.2. Role of Cellular Injury in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Impairments in cellular integrity are being acknowledged as essential for the advancement of neurodegenerative disorders. In diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases, cellular damage is observed mainly through oxidative stress and hypoxia, which disturb normal cell functions and result in neuronal death. The imbalance between free radicals and defensive antioxidants incites oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, which causes cellular adaptations that might temporarily mitigate stress, ultimately leading to cell dysfunction and apoptosis. Furthermore, insufficient oxygen and nutrient delivery worsens these injuries, further impeding ATP creation and resulting in a series of energy depletion effects, particularly in tissues with high metabolic demands, such as the brain. This overall cumulative cellular harm not only triggers neuroinflammation but also establishes a foundation for lasting damage, ultimately resulting in cognitive decline and deterioration of motor capabilities in affected individuals [

56].

10.3. Impact on Cancer Development

In addition to disrupting normal cellular functions, cellular injury is of cardinal importance in the process of cancer formation.Were cells to undergo stressful events like hypoxia or damage from free radicals, their responses may even produce set conditions favorable for the development of a tumour, such as dysplasia or metaplasia. These adaptive changes, hearkening back to our original analogy of chronic stress evolving over time into a powerful enough strain to alter stones, eventually generating genetic mutations and epigenetic adjustments that increase one’s chances of suffering from cancer. Moreover, because the accumulation of metabolic products, especially under hypoxic conditions, contributes to an inflammatory microenvironment, it effectively increases the cancerous potential of tumors [

57,

58,

59,

60]. This complex interaction illustrates how the impact of cellular injury extends not only to individual cells but also provides a basis upon which cancer will advance, which means that any population at risk can be greatly helped by early interventions and specific therapies to prevent cancer [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

10.4. Cellular Injury in Autoimmune Disorders

The complex interplay between the immune system and cellular damage can be seen clearly in autoimmune disorders when an organism mistakenly identifies its own cells as intruders. Such misidentification leads to prolonged inflammation and injury of healthy tissues, as manifested by cellular changes signifying disordered growth (dysplasia) or even transformation to other types of tissue (metaplasia). This kind of injury can be closely related to genetics, environmental factors and immune responses [

66]. Autoimmune diseases generally coincide with the generation of free radicals, which increase cell damage and cause oxidative stress to the concerned tissues, as this is a function of free radical-related injury mechanisms. At the end of this process, all cells lose their normal stability, as indicated by a decline in ATP synthesis and necrosis that follows hypoxia, quite apart from tiny clots operating within capillary beds. Thus, it becomes difficult for researchers to develop appropriate treatments. The outcome of these phenomena as a society in general ultimately generates more harm than benefits to humans [

67]. It is important to understand cellular injury situations using these models for the provision of targeted therapies.

11. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Cellular Injury

In a clinical setting, comprehensive treatment approaches are required to properly address cell injury and its consequences on cells. Injured tissues require treatment strategies that focus on addressing the essential mechanisms that cause injury at the cellular level. For example, in sepsis, endothelial dysfunction is deeply involved in multiple organ failure syndrome (MODS), so it is necessary to take measures that essentialize the endothelial integrity [

68]. With emerging research, it has been discovered that small molecules can be used to regulate endothelial function to mitigate the harmful effects of sepsis-sourced injuries. Similarly, in addressing Ischemic Reperfusion Injury, certain therapeutic targets such as control over oxidative stress and stopping inflammation have shown prospects for protecting cells from injury by an insufficient blood supply [

69]. Targeting specific pathophysiological pathways, such as those highlighted above, that emphasize the significant role played by oxidative stress and hypoxia, these therapeutic strategies hold the promise of either reversing or putting a brake on the tragic outcomes of cellular injury. This indicates the imperative need for undertakings aimed at boosting cellular resilience.

12. Implications for Clinical Practice

Knowing why cells are damaged has important implications for medical practice, especially when diagnosing and treating different kinds of illnesses. For instance, the recognition of various kinds of cellular responses allows clinicians to study the underlying pathophysiology of diseases and tailor appropriate treatment. Moreover, making a distinction between injuries that may get better and those that go on to necrosis permits health care professionals to include time-critical therapeutic measures, such as in cases of hypoxic injury, where immediate restoration of oxygen supply is essential if irreversible damage is to be avoided. Furthermore, the recognition that free radicals contribute to damaged cells reemphasizes the value of antioxidant treatments, which can relieve the long-term consequences of oxidative stress. In short, a detailed understanding of cellular pathophysiology can provide doctors with vital insights into the design of effective treatment strategies and better patient outcomes.

13. Future Directions in Research and Treatment

Cell injury in the subtleties calls for novel strategies of research and treatment that focus on precluding it as well as taking new impetus from preventive care targets. Future research might also look more thoroughly into the mechanisms of injury from both free radicals and hypoxia, in order to develop focused therapies that can turn away their detrimental effects on cells. For example, one might think about using antioxidants, we see the effects of free radicals as speculation, while maintaining the oxygen supply to hypoxic tissues could be especially important in sustaining a good tissue structure. By prodding in the future with the leading edge of stem cell research direction, we have reason to be glad for regenerative medicine even on occasions where damage is both grave and irreversible; here, cell injury, apoptosis, and necrosis form root elements in the underlying pathology. Analyzing the pathways responsible for the increased incidence of dysplasia and the eventual transformation from normal cells to abnormal forms may provide a fresh perspective on methods of attacking cancer. Finally, an integrated approach that takes elements from molecular biology, pharmacology, and regenerative medicine will be essential for what is termed understanding and intervening in cell injuries.

14. Conclusion

However, a critical issue in medical science is understanding the subtle differences between cellular injury and its pathophysiological consequences. The spectrum of cellular adaptations is exemplified by atrophy, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, metaplasia, and dysplasia, which also highlights how cell reactions vary when exposed to different stimuli both inside and outside the cell. Reversible or irreversible adaptations underscore the importance of altering normal cellular activities when damage results from free radicals or hyperoxia, which are particularly important in clinical medicine. These results indicate that this damage appears in the form of either apoptosis or necrosis, making it essential to effectively downregulate these pathways. Recent studies have warned that rapid elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for cellular injury is essential for minimizing tissue damage and promoting full recovery. Ultimately, it is only in understanding the pathogenesis of cellular injury that we can further develop novel therapeutic approaches for improving patient outcomes.

References

- Jang, B.; Coffey, R.J.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, H.; Choi, E.; Goldenring, J.R.; Won, Y.; Kaji, I. Dynamic tuft cell expansion during gastric metaplasia and dysplasia. The journal of pathology. Clinical research 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrer, J.P.; Klotz, L.-O. Free radicals and related reactive species as mediators of tissue injury and disease: implications for Health. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2015, 45, 765–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, B.; Miao, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Dong, H.; Zhang, Z. A decrease of ATP production steered by PEDF in cardiomyocytes with oxygen-glucose deprivation is associated with an AMPK-dependent degradation pathway. International Journal of Cardiology 2018, 257, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Luo, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; Yu, X.; Yang, M.; Jiang, T. Observing single cells in whole organs with optical imaging. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, K.; Hagberg, H. Free radicals, mitochondria, and hypoxia–ischemia in the developing brain. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2005, 40, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, V.P.; Li, W.-M.; Patrick, B.O.; Lofroth, J.; Zeb, M.; Bott, T.M.; Lee, C.H. A specific dispiropiperazine derivative that arrests cell cycle, induces apoptosis, necrosis and DNA damage. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, S.; Papanikolaou, N.A. Reactive Oxygen Species Mechanisms that Regulate Protein-Protein Interactions in Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.L. Kidney atrophy vs hypertrophy in diabetes: which cells are involved? Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 1683–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.J.; Koh, J.S.; Kim, J.C.; Choi, J. Changes in Adenosine Triphosphate and Nitric Oxide in the Urothelium of Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Detrusor Underactivity. The Journal of urology 2017, 198, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Zhi, Z.; Jian, Z.; Ye, Y.; Gu, L. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation to Prevent Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkias, A.; Xanthos, T. Post-cardiac arrest brain injury: Pathophysiology and treatment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2012, 315, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Hargreaves, I.P. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Disorders: Role of Nutritional Supplementation. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, M.W.; Moeller, B.; Cao, Y. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nature Reviews Cancer 2008, 8, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas Lacerda, R.; Gonçalves Da Silva, A.; Sena Romano, I.C. NEURODEGENERATION PROCESSES GO FAR BEYOND NECROSIS AND APOPTOSIS! Multidisciplinary Sciences Reports 2021, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L. Withaferin A Enhances Mitochondrial Biogenesis and BNIP3-Mediated Mitophagy to Promote Rapid Adaptation to Extreme Hypoxia. Cells 2022, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. Early diagnosis and treatment strategies for pediatric growth hormone deficiency. Theoretical and Natural Science 2024, 29, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeux, J.; Caesar, C.; Adesina, S.; Woodard-Grice, A.; Naylor, P.B. Dysregulated Inflammation in Response to Hypoxia-Confounded Injury. The FASEB Journal 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzolla, C.E.; Schnatz, P.F.; Bansal, R.; Mandavilli, S.; Sorosky, J.I.; O’Sullivan, D.M. Dysplasia and Malignancy in Endocervical Polyps. Journal of Women’s Health 2007, 16, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.L.; Zhang, G. Boron PLA for oxygen sensing & hypoxia imaging. Materials Today 2009, 12, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.G.G.; Ferguson, S.A.; Dey, D.; Schröder, K.; Aung, H.L.; Carbone, V.; Attwood, G.T.; Ronimus, R.S.; Meier, T.; Janssen, P.H.; Cook, G.M. A1Ao-ATP Synthase of Methanobrevibacter ruminantium Couples Sodium Ions for ATP Synthesis under Physiological Conditions. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 39882–39892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engoren, M.; Evans, M. Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production and lactic acid during normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion 2000, 15, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, B.D.; Rouch, J.D.; Wang, M.; Meldrum, D.R. Toll-like receptor 4 ablation improves stem cell survival after hypoxic injury. Journal of Surgical Research 2012, 177, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Xi, Z.; Lin, B.; Geng, Y. Molecular mechanisms underlying mitochondrial damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and oxidative stress induced by environmental pollutants. Toxicology Research 2023, 12, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğünç Keçeci, Y.; İncesu, Z. Aglycemia induces apoptosis under hypoxic conditions in A549 cells. Cell Biochemistry and Function 2024, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erukhimovitch, V.; Huleihel, M.; Huleihil, M. Identification of Contaminated Cells with Viruses, Bacteria, or Fungi by Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy. Journal of Spectroscopy 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Al Maqbali, M.; Zihlif, M. Investigating the human rhinovirus co-infection in patients with asthma exacerbations and COVID-19. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abed, A.; Abu-Samak, M.; Alshammari, F.; Alshammari, B. Etiologies of Acute Bronchiolitis in Children at Risk for Asthma, with Emphasis on the Human Rhinovirus Genotyping Protocol. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abed, A.; Al Shawabkeh, M.J.; Aldarawish, R.R.; Al-Shajlawi, M.; Alabbas, N. Human Rhinovirus: Molecular and Clinical Overview. Pharmacy Practice (Granada) 2024, 22, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abed, A.; Jarrar, Y.B.; Alshammari, F.; Alshammari, B.; Basheti, I.A.; Zihlif, M. Alteration of the Respiratory Microbiome in Hospitalized Patients with Asthma–COPD Overlap during and after an Exacerbation. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abed, A.; Khader, H.A.; Al-Shdifat, L.M.; Hasoun, L.; Al-Rshaidat, M.M.; Alkhatib, M.; Zihlif, M. Molecular Accounting and Profiling of Human Respiratory Microbial Communities: Toward Precision Medicine by Targeting the Respiratory Microbiome for Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abed, A.; Khader, H.A.; Hasoun, L.; Al Maqbali, M.; Al Shawabkeh, M.J. The role of human rhinovirus in COPD exacerbations in Abu Dhabi: molecular epidemiology and clinical significance. Libyan Journal of Medicine 2024, 19, 2307679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alkhatib, M.; Al Maqbali, M.; Al-Najjar, M.A.A.; Al-Rshaidat, M.M. A comprehensive clinical guide for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: A missing therapeutic target in HIV-uninfected patients. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2022, 16, 1167–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Hasoun, L.; Khader, H.A.; Abu-Samak, M.S.; Al-Shdifat, L.M.; Al-Shammari, B.; Maqbali, M.A. Co-infection of COVID-19 patients with atypical bacteria: A study based in Jordan. Pharmacy Practice 2023, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Talib, W.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Daoud, S.; Al Maqbali, M. The first detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii in asthmatic patients post-COVID-19 in Jordan. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 2022, 22, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, A.J.; Moayeri, M.; Leppla, S.H. Bacterial Exotoxins and the Inflammasome. Frontiers in Immunology 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Song, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Yan, X.; Dong, Q.; Liu, X.; Yang, L. Roles of reactive oxygen species in inflammation and cancer. MedComm 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, K.; Birch-Machin, M. Oxidative Stress and Ageing: The Influence of Environmental Pollution, Sunlight and Diet on Skin. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenberger, R.J.; Ganetzky, B.; Wassarman, D.A. Age and Diet Affect Genetically Separable Secondary Injuries that Cause Acute Mortality Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Drosophila. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2016, 6, 4151–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.D.; Karki, K.; Pande, D.; Negi, R.; Khanna, R.S. Inflammation, Free Radical Damage, Oxidative Stress and Cancer. Interdisciplinary Journal of Microinflammation 2014, 1, 1000109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, B.; Rahfiludin, Z.; Setyaningsih, Y.; Nurjazuli, N. Ergonomic Risk, Muscle Tension, Lactic Acid, and Work Performance on Transport Workers at Fish Auction. Media Kesehatan Masyarakat Indonesia 2022, 18, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Duan, X.; Fu, S.; Zhao, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wen, Q.; Fan, J.; Luo, L.; Yang, J.; Peng, J.; Wu, J. TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator is indispensable for mitochondria quality control and degradation following damage. Oncology letters 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussipbek, B.A.; López, L.C.; Ablaikhanova, N.T.; Murzakhmetova, M.K. OXIDATIVE STRESS AND MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION. Series of biological and medical 2020, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.L.H.; Bae, D.-H.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Sahni, S.; Richardson, D.R.; Chiang, S. The Role of the Antioxidant Response in Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Degenerative Diseases: Cross-Talk between Antioxidant Defense, Autophagy, and Apoptosis. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2019, 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtscher, M.; Mairer, K.; Wille, M.; Sumann, G.; Gatterer, H.; Faulhaber, M.; Ruedl, G. Short-term exposure to hypoxia for work and leisure activities in health and disease: which level of hypoxia is safe? Sleep and Breathing 2011, 16, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehendale, H.M. Once initiated, how does toxic tissue injury expand? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2012, 33, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasuri, K.; Zhang, L.; Keller, J.N. Oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and the balance of protein degradation and protein synthesis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2012, 62, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, C.; Cahoon, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, D. Dexmedetomidine post-treatment exacerbates metabolic disturbances in septic cardiomyopathy via α2A-adrenoceptor. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 170, 115993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Molecular mechanisms of liver injury: Apoptosis or necrosis. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology 2014, 66, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhong, J.; Dou, X.; Cheng, C.; Huang, Z.; Sun, X. Effects of ApoE on intracellular calcium levels and apoptosis of neurons after mechanical injury. Neuroscience 2015, 301, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, W.J.; Nazarewicz, R.R.; Parihar, M.S.; Ghafourifar, P. Hypoxia/Reoxygenation of isolated rat heart mitochondria causes cytochrome c release and oxidative stress; evidence for involvement of mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2007, 43, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Calcium Homeostasis Following Traumatic Neuronal Injury. Current Neurovascular Research 2004, 1, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurrens, K.; Schluter, K.; Schleef, R.; Ruf, S.; Vonholt, K.; Ross, G. Smoking accelerates the progression of hypertension-induced myocardial hypertrophy to heart failure in spontaneously hypertensive rats☆. Cardiovascular Research 2007, 76, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Mittal, R.; Khanna, H.D.; Basu, S. Free Radical Injury and Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e722–e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Jie, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, C.; Xin, T.; Yang, D. Renal tubular cell death and inflammation response are regulated by the MAPK-ERK-CREB signaling pathway under hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction 2019, 39, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.; Cao, F.; Xie, X. Mitochondrial Metabolism in Myocardial Remodeling and Mechanical Unloading: Implications for Ischemic Heart Disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunomura, A.; Smith, M.; Zhu, X.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.; Moreira, P.; Castellani, R. Neuronal Death and Survival Under Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets 2007, 6, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Abed, I.; Raad, D.; Alomari, R.K.; Jamal, A.; Jabbar, R.; Alhasan, E.O.A.; Alshaeri, H.K.; Alasmari, M.M.; Law, D. Targeting Cancer Hallmarks Using Selected Food Bioactive Compounds: Potentials for Preventive and Therapeutic Strategies. Foods 2024, 13, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Ahmed Jum’AH, D.A.; Attallah, Z.S.; Jallad, M.S.; Al Kury, L.T.; Hadi, R.W.; Mahmod, A.I. Role of vitamins A, C, D, E in cancer prevention and therapy: Therapeutic potentials and mechanisms of action. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 10, 1281879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abuawad, A.; Daoud, S.; Mahmod, A.I. Melatonin in cancer treatment: current knowledge and future opportunities. Molecules 2021, 26, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Alsayed, A.R.; Barakat, M.; Abu-Taha, M.I.; Mahmod, A.I. Targeting drug chemo-resistance in cancer using natural products. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Mahmod, A.I.; Kamal, A.; Rashid, H.M.; Alashqar, A.M.; Khater, S.; Jamal, D.; Waly, M. Ketogenic diet in cancer prevention and therapy: molecular targets and therapeutic opportunities. Current issues in molecular biology 2021, 43, 558–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Alsayed, A.R.; Farhan, F.; Al Kury, L.T. Resveratrol and tumor microenvironment: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic targets. Molecules 2020, 25, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihlif, M.A.; Afifi, F.; SHARAB, A.; MAROOF, P.; ALSAYED, A.R. Antimicrobial potency of red and yellow varieties of grapefruit (Citrus Paradisi Macfad) grown in Jordan. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Zihlif, M.; Khader, H.A.; Hasoun, L.; Al-Imam, A.; Al Shawabkeh, M.J.; Fino, L.B.; Alsa’d, A.A.; Al-Shajlawi, M.; Alsayed, A.R. Natural agents’ role in cancer chemo-resistance prevention and treatment: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Khader, H.A.; Basheti, I.A.; Permana, A.D. Bovine Colostrum Treatment of Specific Cancer Types: Current Evidence and Future Opportunities. Molecules 2022, 27, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ali, E.H.; Mohammed, H.O. Autoimmune Disorders Unraveled: The Interplay Between Genetics and the Immune System. International Journal of Medical Science and Dental Health 2024, 10, 01–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, S.; Dalal, V.; Biswas, S.; Paul, A.; Pathak, A. Oxidative Stress in Autoimmune Diseases: An Under Dealt Malice. Current Protein & Peptide Science 2020, 21, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zhao, X.-L.; Xu, L.-Y.; Zhang, J.-N.; Ao, H.; Peng, C. Endothelial dysfunction: Pathophysiology and therapeutic targets for sepsis-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 178, 117180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Banerjee, S.K.; Sood, S.; Dinda, A.K.; Maulik, S.K. Extract from Clerodendron colebrookianum Walp protects rat heart against oxidative stress induced by ischemic–reperfusion injury (IRI). Life Sciences 2005, 77, 2999–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).