1. Introduction

Considering that the visual sense has the highest bandwidth among all human senses, an image is one of the most natural ways to receive large amounts of information. For this reason, science and technology have always shown a particular interest in understanding and modeling all aspects related to image formation, modification, storage, and transmission. Optics is the discipline that embodies this knowledge, accumulated over centuries, and provides a model for the propagation of information and energy through electromagnetic waves (in the visible spectrum) [

1].

However, it is in recent decades that photonic and optical techniques have emerged as powerful tools for processing the information contained in an image, especially as previously developed models have been implemented into computer-executable algorithms. In parallel, it has been necessary to develop systems and algorithms to protect this information from unauthorized access or data tampering [

2,

3,

4].

Among all these technologies, Computer-Generated Holograms (CGH) have proven to be a viable option for massive information storage, typically associated with text images or 2D and 3D scenes. This process requires a significant amount of computational resources, which, in some cases, exceed the capabilities of current computers if synthesis is to be performed within acceptable time frames.

Similarly, the information stored in the CGH must also be securely stored and transmitted. Consequently, specialized encryption techniques have been developed in parallel to safeguard the integrity of CGHs and prevent unauthorized access [

5,

6].

A widely used optical encryption method for image applications is Double Random Phase Encoding (DRPE) [

7]. In DRPE, the input image is represented by the amplitude of light, which is modulated by a random phase before being transformed by a Fourier transform. A second random phase mask is then applied in the Fourier domain as an encryption key. The resulting complex amplitude, either in the Fourier domain or in the spatial domain, is considered the encrypted information. An evolution of this approach is optical encryption using digital holography [

8]. This technique can also be modeled using algebraic procedures, such as vector-matrix multiplications [

9].

The double-phase encryption technique has been successfully tested using both static and dynamic keys. However, this method presents certain vulnerabilities to attacks, as recognized in the literature. If the process is purely linear, there is a possibility of breaking the encryption key [

10]. To enhance DRPE, various improvements have been proposed. One approach involves modifying pixels using chaotic functions [

11], while another leverages deep learning techniques [

12].

Traditionally, the phase masks proposed for Double Random Phase Encoding (DRPE) have aimed to ensure uniformity in both the amplitude of the hologram and the phase distribution of the encrypted Computer-Generated Hologram (CGH) to make unauthorized decryption more challenging. Various photosensitive materials (e.g., photorefractive media) have been used for their implementation [

13]. Currently, with advancements in spatial light modulator (SLM) technology, diffractive elements computed digitally (such as CGHs and phase masks) can be directly applied to a light beam in the laboratory. This enables both the encrypted data and the encryption keys to be dynamic.

In this article, we present an evolution of this technique by incorporating random pixel permutation. In

Section 2, we describe the complete workflow, starting from the generation of a 3D scene using Computer Graphics, its storage in a Computer-Generated Hologram (CGH), followed by the encryption and decryption processes, and concluding with its final visualization.

This work places particular emphasis on proposals related to the encryption phase. The novelty of this approach lies in the fact that it allows, if desired, the use of a single key for both the pixel permutation process and the phase modification, generating the encrypted CGH, which serves as the ciphertext. In

Section 3, we evaluate the obtained results using Pearson?s correlation coefficient as a metric to assess the similarity between the recovered images at different encryption levels of the same scene. Finally,

Section 4 highlights the main conclusions of this work.

2. From the Synthesis of a 3D Scene to Its Safe Reception: Process Description

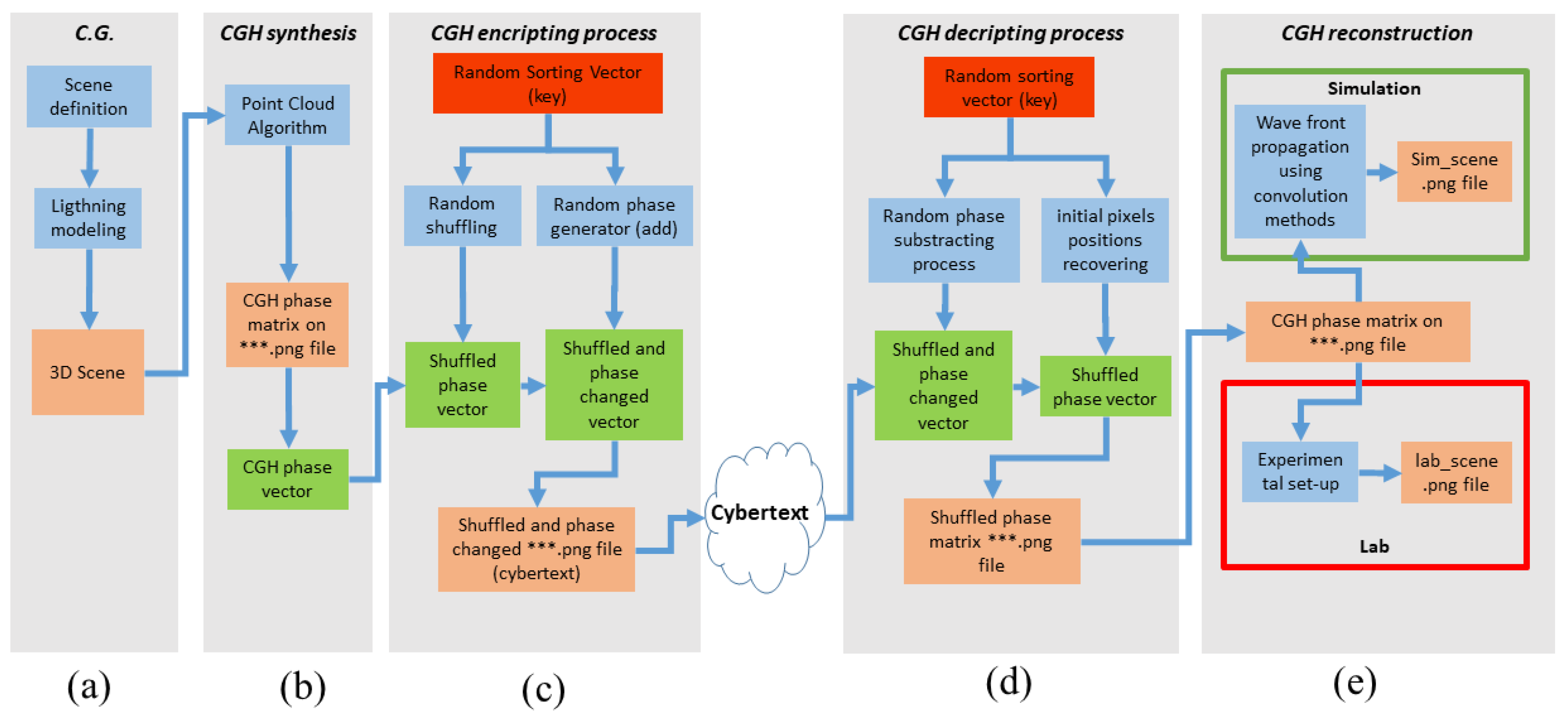

The flowchart for the proposed process is shown in

Figure 1. It illustrates the different stages required to securely transmit a scene that has been previously modeled using Computer Graphics techniques (

Figure 1.(a)), stored in a CGH (

Figure 1.(b)), encrypted (

Figure 1.(c)), decrypted (

Figure 1.(d)), and visualized (

Figure 1.(e)). Algorithms and procedures are shown in blue, results that can be visualized on an SLM or simulated via computer are in orange, vectors used to manipulate information during the encryption process are in green, and the key used for encryption or decryption is in red.

2.1. Scene and CGH Sysnthesis

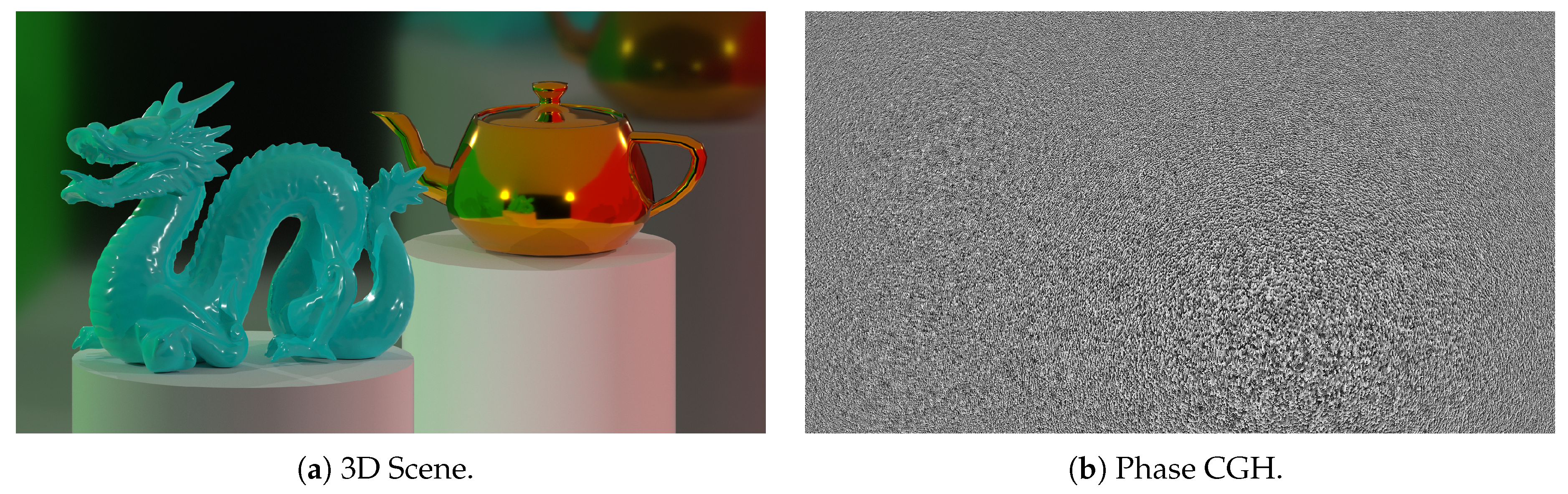

To illustrate the encryption algorithm used, a 3D scene has been designed with well-known objects in the field of Computer Graphics: a dragon and a teapot contained within a Cornell Box (

Figure 1(a)).

Using the ray tracing technique "path tracing" [

14], a CGH is computed and stored in a matrix of

elements (

Figure 1(b)). The phase information can be converted into a PNG-format image, which can then be displayed on an SLM?in our case, the Pluto Holoeye [

15], with a pixel size of

.

The CGH calculation already inherently includes the first phase mask described in the DRPE algorithm, and the presented procedure allows encoding both 2D and 3D scenes. This phase corresponds to

Figure 1 (b).

Figure 2(a) shows the proposed scene, and

Figure 2(b) displays the phase of the computed CGH in PNG format. The scene window matches that of the SLM (

). The detailed process of scene synthesis and CGH generation can be found in [

16].

2.2. Encryption of the CGH

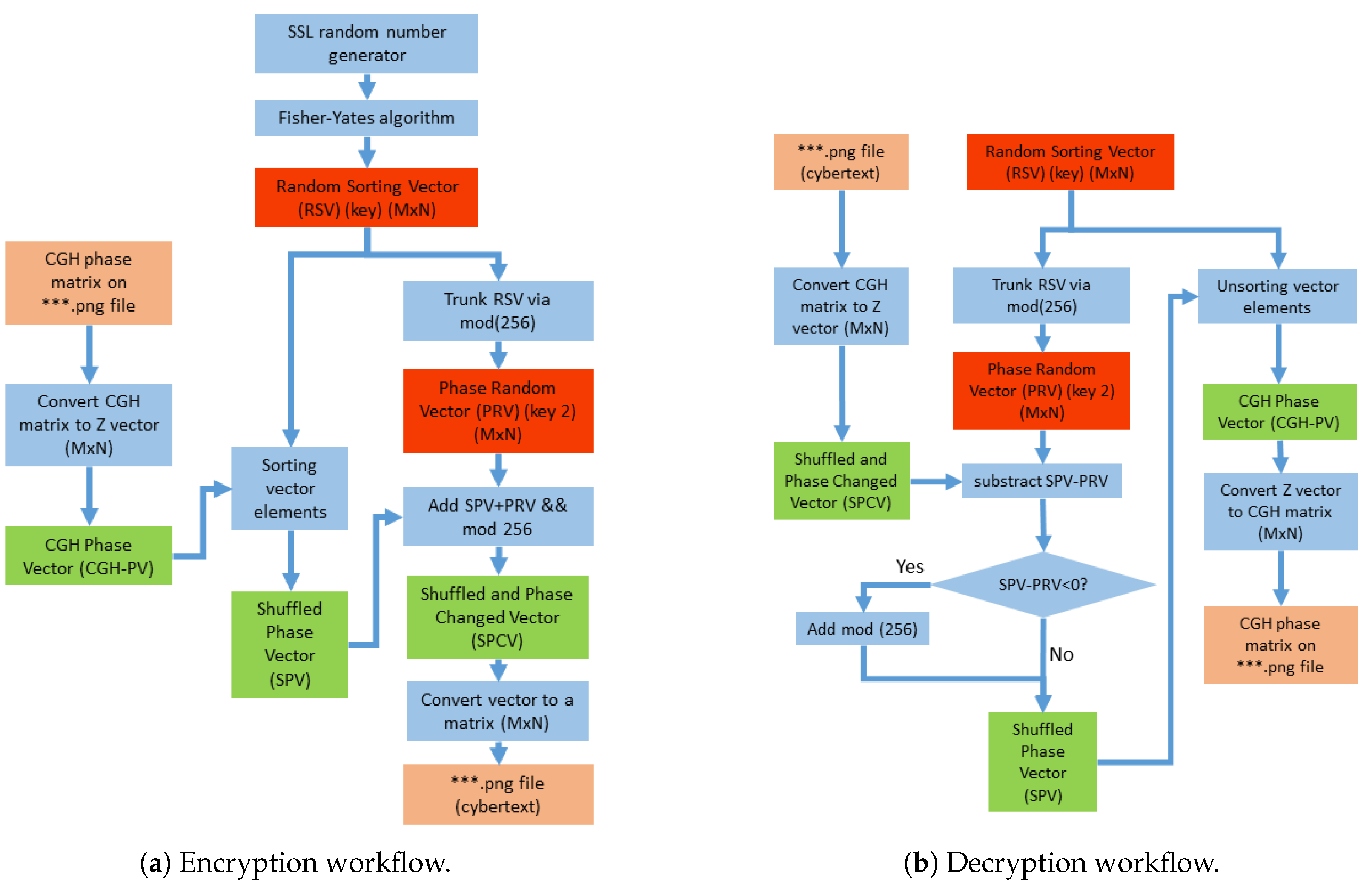

Figure 3(a) shows the flowchart for key generation and CGH encryption. The proposed method involves applying the DRPE algorithm for phase modification and pixel shuffling of the CGH. We will see that pixel shuffling creates a combinatorial explosion that is difficult to attack by brute force. Additionally, phase modification adds an extra layer of encryption to the information stored in the CGH. This stage corresponds to

Figure 1(c).

To select a truly random key, a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator (CSPRNG) must be used. In this work, the random function from MATLAB’s System.Security.Cryptography library has been used.

These numbers are used to feed the Fisher-Yates algorithm [

17], which is a classic algorithm for randomly and securely shuffling a set of elements. It works by traversing the elements of a vector in reverse order and generating a random index

j for each element

i, such that

, with

i being the index of the element being modified at each step. Finally, the elements

i and

j are swapped in position.

This information is stored in the Random Sorting Vector (RSV) of size

(

Figure 3(a)). The encryption process uses the phase matrix of the CGH, stored in a PNG file, to convert it into a CGH-PV vector of size

. Using the RSV shuffling vector, the positions of the CGH-PV are changed, resulting in the Shuffled Phase Vector (SPV).

From the RSV vector, a phase mask vector can be obtained through a truncation operation.

It is necessary to ensure that the values are within range through a modulo operation.

Depending on the required security level, the phase mask can be generated from the shuffling vector through a modulo operation on this vector, both in the encryption phase and in the decryption phase, or with a separate procedure.

This vector is added to the SPV to modify the phase pattern, resulting in the Shuffled and Phase Changed Vector (SPCV).

The SPCV vector is reordered to recover a matrix of size , which will be the ciphertext to be sent to a receiver.

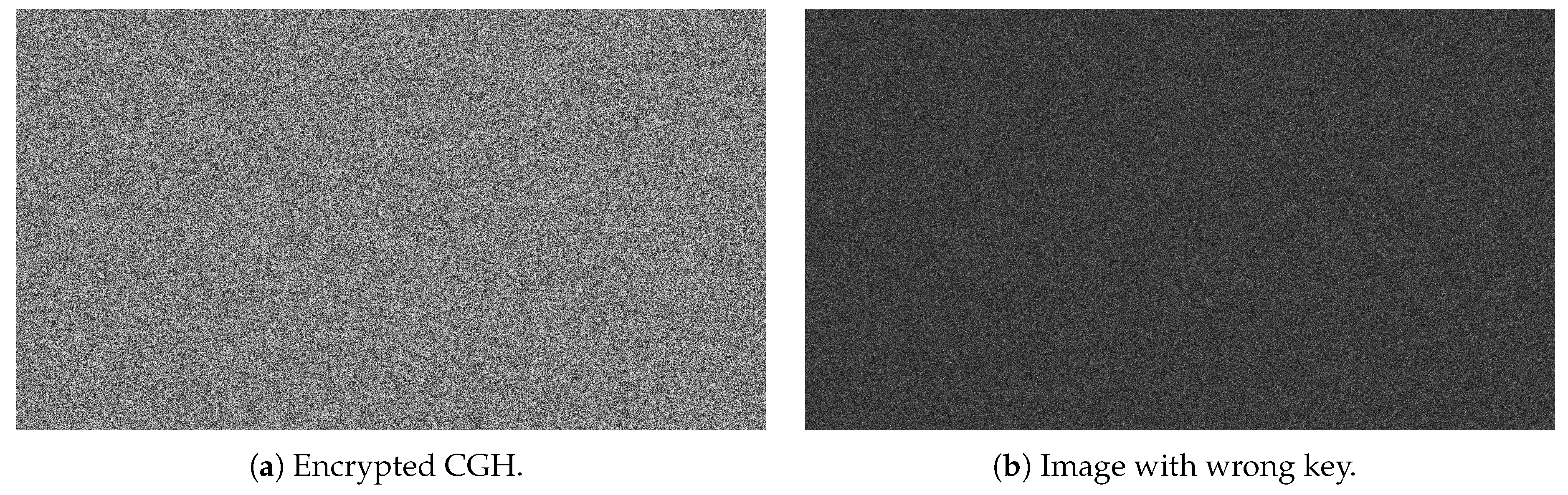

The result of the encrypted CGH obtained (the ciphertext) is shown in

Figure 4(a), and the image obtained with an incorrect key is shown in

Figure 4(b). As we will see in

Section 3, the histogram of

Figure 4(b) is nearly uniform.

2.3. Decryption and Visualization of the Scene Stored in the CGH.

Decryption (

Figure 1(d) and

Figure 3(b)) involves undoing the steps from the previous section. In the decryption process, this random phase contribution is subtracted from the SPVC to recover the SPV:

The original order is then restored to obtain the CGH-PV using the indices stored in the RSV vector (

Figure 3(b)). Negative values resulting from this subtraction are adjusted by adding the modulo to ensure they remain within the allowed range of phase values.

From this vector, the phase matrix of the CGH is obtained to recover an image file (png format). With the correctly decrypted CGH, the original scene can be recovered. This step corresponds to

Figure 1(e).

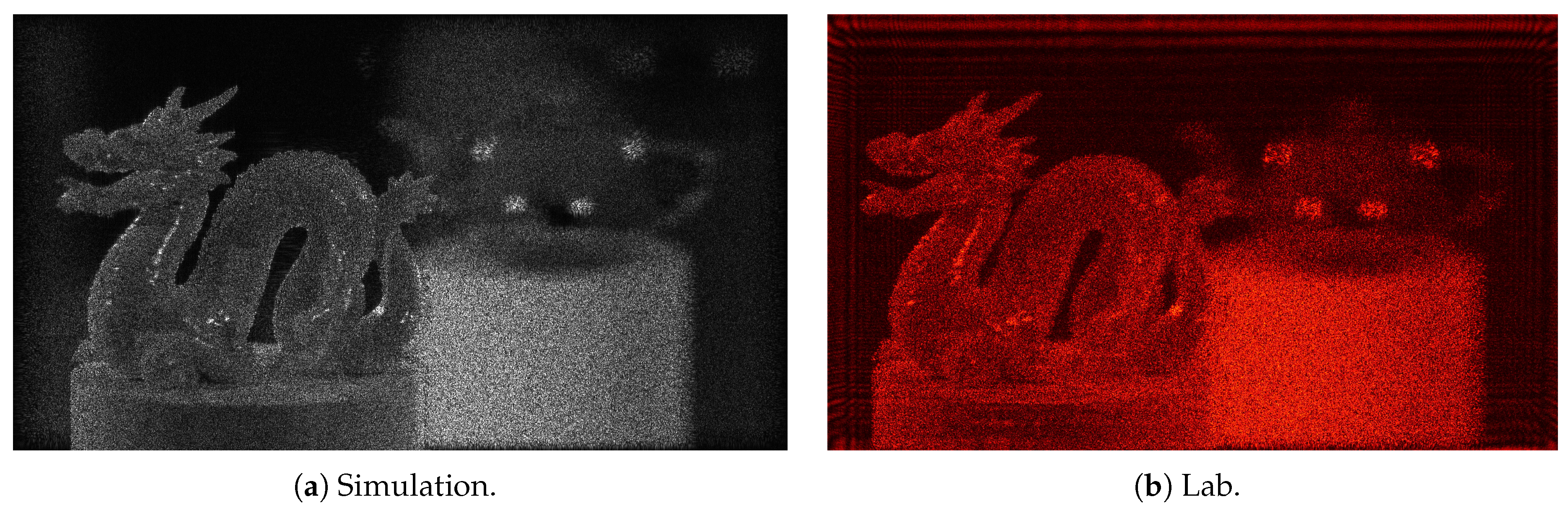

Figure 5 shows the results for phase holograms encoded with integer values

corresponding to images in PNG format. In our case, since the phase information is encoded with integer numbers, no information is lost.

The original scene can be recovered either by simulation (using convolution algorithms such as the angular spectrum [

1]) (see

Figure 5(a)) or in the laboratory (

Figure 5(b)). In both cases, the behavior of a plane wavefront disturbed by the phase information of the CGH at each pixel is visualized in a specific plane (which coincides with the position of the dragon’s head in the 3D scene). To obtain the image in

Figure 5(b), a CCD from a lensless camera is placed in this plane.

The quality of the final image is usually affected by several factors: Working with only the phase and encoding it with integer numbers within the allowed range impacts the final scene quality. The dynamic range or the pixel size of the SLM (real or simulated) also directly affects the final quality. Additionally, speckle phenomena always appear, which are not attributable to the encryption technique. To improve the final image, the process can be iterated by generating multiple CGHs and applying statistical filtering techniques [

18,

19].

3. Results Discussion

The proposed procedure is robust to different types of attacks, as it:

CGH Storage: The 3D scene is stored within a CGH. Vulnerability to Statistical Analysis is avoided since methods such as intensity histograms cannot reveal patterns or facilitate partial image reconstruction. It is also resistant to partial transformations, as modifying a subset of pixels in the CGH does not compromise the integrity of the stored information.

Pixel Shuffling: As will be shown next, pixel shuffling can be robust against brute force attacks when the number of possible pixel permutations is sufficiently large.

Random Phase Modification: This adds an additional layer of complexity to the encryption, as it modifies the phase disturbance that each pixel of the CGH presents to the reconstruction wavefront. It also alters the phase histogram of the ciphertext, further complicating attacks using statistical tools.

3.1. Remarks on Pixel Shuffling

The data size to be managed in this work is a matrix of integer values, which can range between ; that is, 256 different values.

Let us assume that each pixel value appears a certain number of times, denoted as ; that is, , where can take a value within the interval , with the restriction that the sum of all values will equal Z.

Let us assume that we start with the Z pixels placed in a bag, and we extract them one by one without replacement to place them into a matrix of size pixels. Therefore, Z extractions must be performed. The extractions are assumed to be statistically independent.

Probability that the first selected pixel matches the first pixel of the image: Suppose the first pixel has the value

j within the range [0-255], and it appears

times, then

Probability that the second extraction matches the second pixel of the image: Suppose the second pixel has the value

k within the range

, and it appears

times, then

however, it is also possible that it has the value

j, in which case the probability would be

Following this reasoning, the probability that the

L-th extraction matches the

L-th pixel of the image: Suppose the

L-th pixel has the value

m within the range

, and it appears

times but has already appeared

n times previously, then

Iterating this process, the final probability of successfully reconstructing the image by extraction would be given by the probability of matching all the pixels of the CGH; that is:

The combinatorial explosion depends on the range of values that can be taken and the size of the matrix. In our case, the range is

and the size is

. To make an estimation, we know that the histograms of the phases encoded in a png file are practically uniform; that is, the frequency values in these histograms tend to satisfy the following equality:

. In this case, we can make the following estimation:

The factorial is an extraordinarily large number. Using Stirling’s approximation [

20], an estimation can be made:

To determine the size of this number, we can calculate the number of digits it has.

That is, around 11 million digits. Therefore, the probability of reconstructing the matrix is effectively zero. If a processing machine were used that took per possibility, it would take , which is an incomprehensibly long time compared to any human or even geological timescale.

This pixel shuffling method of a scene, in which a mathematical transformation operation has been previously applied (the synthesis of a CGH can be likened to this operator), already provides a fairly robust encryption against statistical analysis (the phase distribution in a histogram is practically flat) or brute force attacks.

3.1.1. Key Size Issues.

The proposed key is a vector of

integer values and whose size increases as a function of the CGH resolution, which may result in keys of considerable size. One should consider the option of compressing this information using arithmetic encoding techniques [

21] that guarantee to avoid loss of information in order to have a lighter key.

3.2. Remarks on DRPE Phase Mask

Let us recall that we have the key, which is a vector containing the permutations of the pixels, and a vector in which the permuted phases are stored. Now we will modify these values as follows: another vector will be constructed to store the modifications of the phase values, based on the vector containing the pixel permutations. Since Z is a number greater than the phase range encoded in the CGH , the proposed procedure is to truncate (modulo 256) each component of the pixel shuffling vector (the key) and add it to the phase in the same position in the phase vector. In this way, for each pixel in the CGH, a new phase value is obtained, which can range between . A brute-force attack would involve modifying the positions and values of the pixels.

The phase hologram obtained after these operations and its reconstruction using well-known convolution methods in the literature [

1] are shown in

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 4(b), respectively.

Following a similar approach to the previous subsection, we assume that we have

Z elements of a matrix with values in the range

. Adding a random phase implies that each of these

Z elements can have any value within the mentioned range. The probability of recovering the original phase of pixel

i in the CGH is:

Since each pixel is an independent case, the probability of correctly recovering all the phases would be:

The probability of finding the correct phase match is also very small (the denominator has nearly 5 million digits) and adds another layer of security to the CGH encryption, breaking any pattern that could have existed in the phase histogram.

3.3. Partial Encryption of the CGH

Given the large number of possible permutations, the question arises: Is it possible to reduce the number of permutations (that is, reduce the computational costs) while maintaining a secure level of encryption?

The answer is conditioned by the very nature of the CGH creation process. All points in the scene contribute to all pixels of the CGH, so a practically complete shuffling is necessary to fully conceal the recorded information. The same applies to an encryption process in which only the phase mask is used to hide the information.

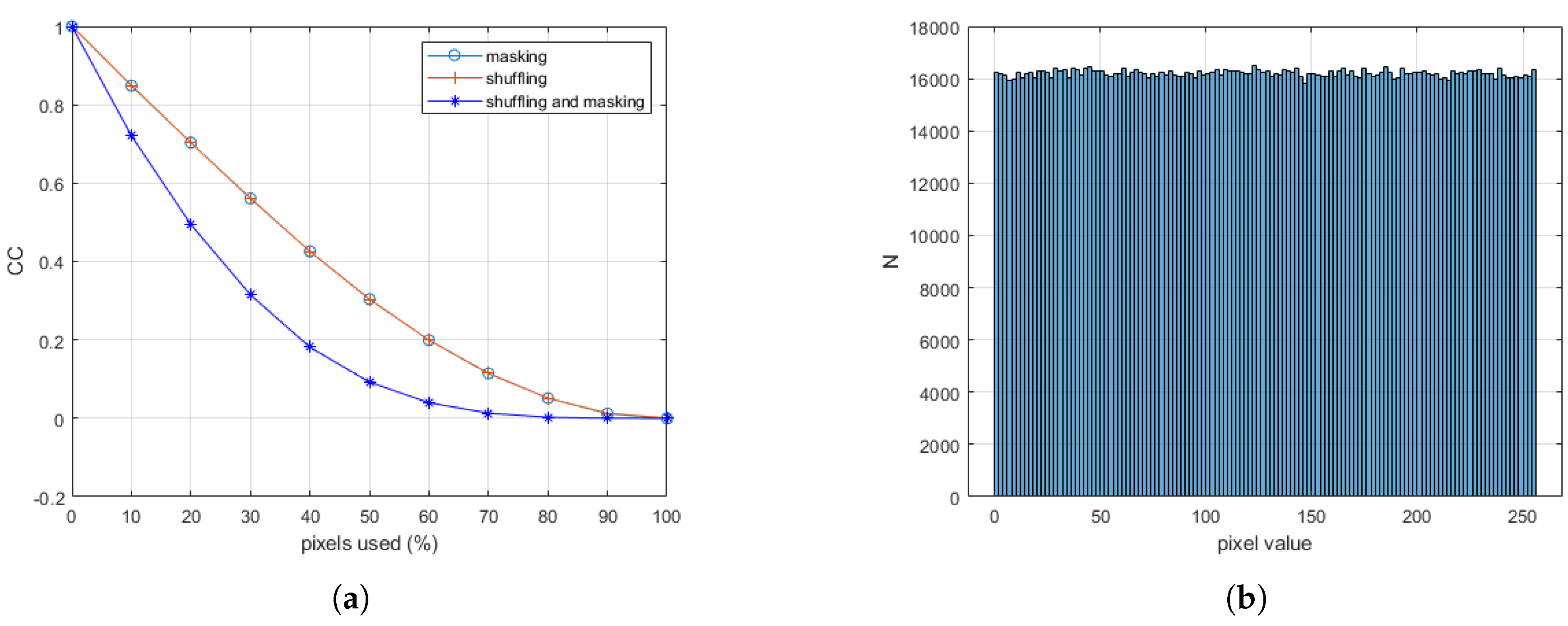

A method to quantify this statement is by using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient to measure the similarity between images. In

Figure 6(a), this coefficient is shown as a function of the percentage of shuffled pixels, pixels with modified phase, and pixels where both phase and position are modified, between the original reconstructed image (

Figure 5(a)) and those obtained with different percentages. Only when all pixels are shuffled is the absence of correlation guaranteed. For the calculation of the Correlation Coefficient (CC) shown in

Figure 6(a), the reference image is

Figure 5(a). In the case of

shuffled pixels, it is compared with itself (

). This value decreases, reaching (

) when

of the pixels are modified (

Figure 4(b)).

The

Figure 6(b) shows the histogram of the encrypted CGH, where it is observed that the phase value distribution is nearly flat, which helps to hinder statistical analysis-based hacking attempts.

These graphs can aid in managing the trade-off between encryption computation time and the required level of security. Additionally, other factors complicate the process of unauthorized decryption, such as the wavelength used for CGH synthesis or the geometry of the recording process (the distance between the scene and the CGH plane). In a trial-and-error process, the computation time should also account for the cost of calculating the convolution integral to reconstruct the scene from the CGH.

4. Conclusions

Encoding information using CGH and random phases (DPRE) has proven to be a robust technique for information encryption in the past. However, brute force attacks reduce the success time as the available computational power increases to find the decryption key.

We present an evolution of DRPE that adds the random permutation of pixels. This proposal allows the use of a single key to generate the CGH that serves as ciphertext or the use of two independent keys: one for the permutation and another for the synthesis of the random phase mask.

The entire process can be simulated on a computer or demonstrated in a laboratory. The permutation possibilities add a new layer of complexity against attacks.

Encoding the information in a CGH makes the generated ciphertext robust to localized modifications, the random phase modification makes the phase histogram distribution more resilient to statistical attacks, and the shuffling of already-encrypted pixels significantly increases the combinatorial possibilities to explore, rendering a brute-force attack unfeasible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and F.S.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B., F.S.; formal analysis, A.B., F.S.; investigation, A.B., F.S.; resources, A.B., F.S.; data curation, A.B., F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, F.S.; visualization, A.B., F.S.; supervision, A.B., F.S.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This initiative is carried out within the framework of the EU-funded "Plan de de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia" (Next Generation). Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad (INCIBE) (Spain).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Diego Sanz (trainee student of Department of Computer Science at the University of Zaragoza) for his contribution in the design and synthesis of

Figure 2(a).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodman, J.W. Introduction to Fourier optics. Introduction to Fourier optics, 3rd ed., by JW Goodman. Englewood, CO: Roberts & Co. Publishers, 2017 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Javidi, B.; Chen, X. Advances in optical security systems. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2014, 6, 120–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishchal, N.K. Optical Cryptosystems; 2019; pp. 1–180. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, A.K. A comprehensive survey on encryption techniques for digital images. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 11155–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, B.; Carnicer, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Nomura, T.; Pérez-Cabré, E.; Millán, M.S.; Nishchal, N.K.; Torroba, R.; Barrera, J.F.; He, W.; et al. Roadmap on optical security. Journal of Optics 2016, 18, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, B.; Chen, J. Optical image encryption and authentication using phase-only computer-generated hologram. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2021, 146, 106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refregier, P.; Javidi, B. Optical image encryption based on input plane and Fourier plane random encoding. Optics Letters, Vol. 20, Issue 7, pp. 767-769 1995, 20, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajahuerce, E.; Javidi, B. Encrypting three-dimensional information with digital holography. Applied Optics, Vol. 39, Issue 35, pp. 6595-6601 2000, 39, 6595–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, M.; Nakano, K.; Suzuki, H.; Yamaguchi, M. Encrypted imaging based on algebraic implementation of double random phase encoding. Applied Optics, Vol. 53, Issue 14, pp. 2956-2963 2014, 53, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer, A.; Montes-Usategui, M.; Arcos, S.; Juvells, I. Vulnerability to chosen-cyphertext attacks of optical encryption schemes based on double random phase keys. Opt. Lett. 2005, 30, 1644–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamadi, I.A.; Jamal, R.K.; Mousa, S.K. Image encryption based on computer generated hologram and Rossler chaotic system. Optical and Quantum Electronics 2022, 54, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Ying, Y.; Sun, X.; Jin, W. The recovery scheme of computer-generated holography encryption–hiding images based on deep learning. Optics Communications 2023, 529, 129100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Javidi, B. Optical encryption based on the input phase mask designed for the space bandwidth of the optical system. In Proceedings of the Optical Information Systems III; Javidi, B.; Psaltis, D., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, Vol. 5908; 2005; p. 59080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiya, J.T. The rendering equation. SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1986, 20, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLUTO-2 Phase Only Spatial Light Modulator (Reflective) | HOLOEYE Photonics AG.

- Magallón, J.A.; Blesa, A.; Serón, F.J. Monte–Carlo Techniques Applied to CGH Generation Processes and Their Impact on the Image Quality Obtained. Engineering Reports 2025, 7, e13109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durstenfeld, R. Algorithm 235: Random permutation. Communications of the ACM 1964, 7, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Memmolo, P.; Leo, M.; Montresor, S.; Distante, C.; Paturzo, M.; Picart, P.; Javidi, B.; Ferraro, P. Strategies for reducing speckle noise in digital holography. Light: Science and Applications 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, D.; Birnbaum, T.; Ito, T.; Shimobaba, T. The state-of-the-art in computer generated holography for 3D display. Light: Advanced Manufacturing 2022, 3, 572–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1997. Includes discussion on Stirling’s approximation in combinatorial analysis.

- Witten, I.H.; Neal, R.M.; Cleary, J.G. Arithmetic coding for data compression. Commun. ACM 1987, 30, 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).