Submitted:

08 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

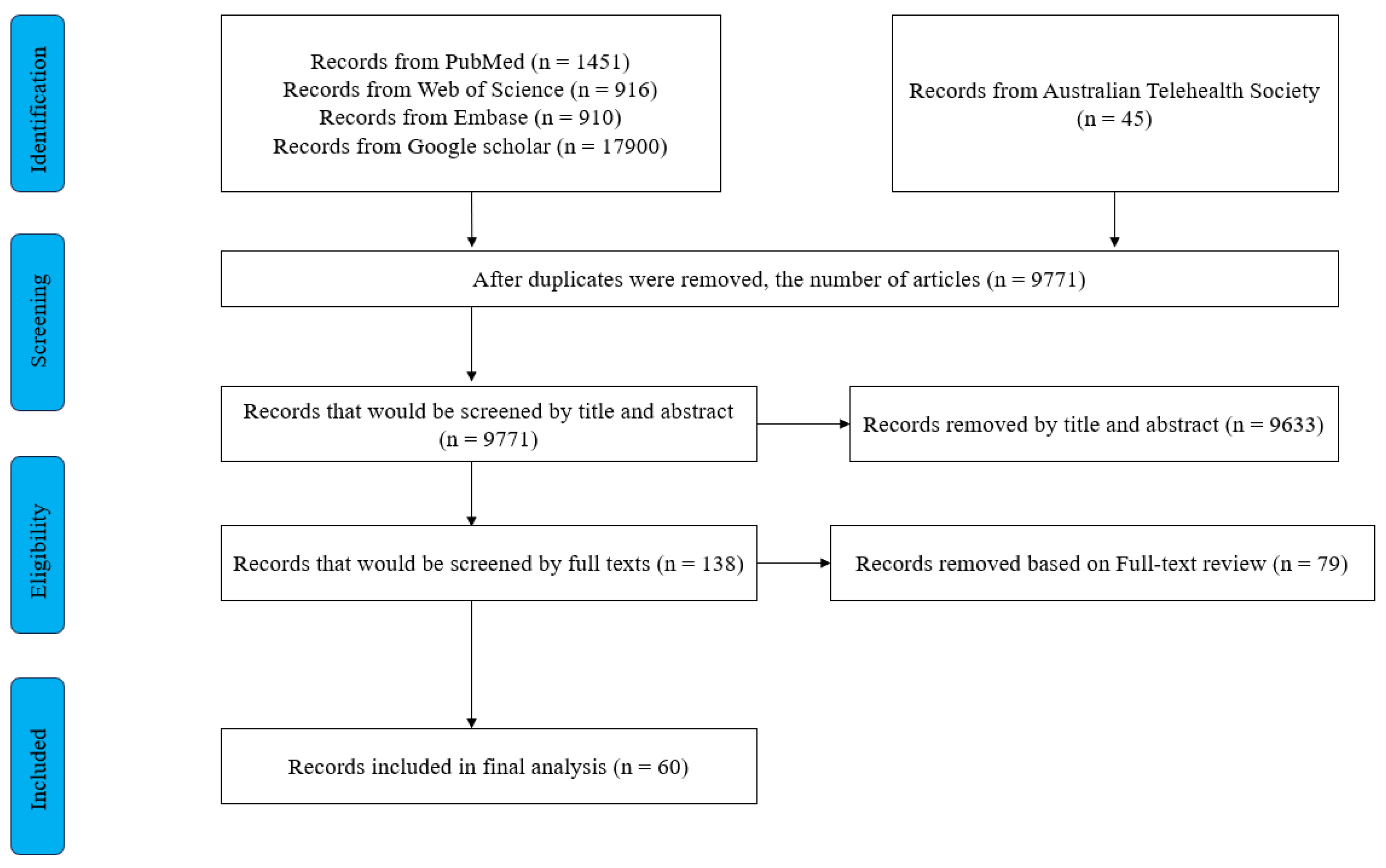

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Searching strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data extraction and analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies.

3.2. Critical characteristics of studies, success, and challenges of using digital health methods to promote primary health care in Australia.

3.2.1. Health service delivery (organised around the population)

3.2.2. Health Workforce

3.2.3. Health Information System (HIS)

3.2.4. Medicine, Vaccines, diagnostic and technologies

3.2.5. Community engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Tailored designs in DHIs are needed to help priority populations overcome cultural barriers.

4.3. Language barriers faced by CALD and First Nations peoples are still significant.

4.4. The role of DHIs in relation to the regional digital divide faced by First Nations peoples.

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHIs | Digital Health Interventions |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| CALD | Culturally and Linguistically Diverse |

References

- World Health Organization. Universal health coverage (UHC) 2023 [cited 7 January, 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc).

- World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage n.a. [cited 7 January, 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1.

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata International Conference on Primary Health Care; Alma-Ata, USSR,1978.

- World Health Organization. Global diffusion of eHealth: making universal health coverage achievable: report of the third global survey on eHealth. World Health Organization; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Classification of digital health interventions v1.0. 2018.

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025. 2021.

- Kasteleyn MJ, Versluis A, van Peet P, Kirk UB, van Dalfsen J, Meijer E, et al. SERIES: eHealth in primary care. Part 5: A critical appraisal of five widely used eHealth applications for primary care - opportunities and challenges. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021;27(1):248-56.

- Erku D, Khatri R, Endalamaw A, Wolka E, Nigatu F, Zewdie A, et al. Digital Health Interventions to Improve Access to and Quality of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023;20(19):6854. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal C, Stolee P, Juzwishin D, Husereau D. Economic evaluations of eHealth technologies: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198112-e. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava D, Van Kessel R, Delgrange M, Cherla A, Sood H, Mossialos E. A Framework for Digital Health Policy: Insights from Virtual Primary Care Systems Across Five Nations. PLOS digital health. 2023;2(11):e0000382-e. [CrossRef]

- Health AIo, Welfare. Health expenditure Australia 2020-21. Canberra: AIHW; 2022.

- Endalamaw A, Erku D, Khatri RB, Nigatu F, Wolka E, Zewdie A, et al. Successes, weaknesses, and recommendations to strengthen primary health care: a scoping review. Arch Public Health. 2023;81(1):100-. [CrossRef]

- Fisher M, Freeman T, Mackean T, Friel S, Baum F. Universal Health Coverage for Non-communicable Diseases and Health Equity: Lessons From Australian Primary Healthcare. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(5):690-700. [CrossRef]

- Bradley C, Hengel B, Crawford K, Elliott S, Donovan B, Mak DB, et al. Establishment of a sentinel surveillance network for sexually transmissible infections and blood borne viruses in Aboriginal primary care services across Australia: The ATLAS project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):769-. [CrossRef]

- Henderson J, Javanparast S, MacKean T, Freeman T, Baum F, Ziersch A. Commissioning and equity in primary care in Australia: Views from Primary Health Networks. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(1):80-9. [CrossRef]

- Marcus K, Balasubramanian M, Short SD, Sohn W. Dental hesitancy: a qualitative study of culturally and linguistically diverse mothers. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2199-. [CrossRef]

- Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: A framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ong KS, Carter R, Kelaher M, Anderson I. Differences in primary health care delivery to Australias Indigenous population: A template for use in economic evaluations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):307-. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon B, Durham J, Wyld D, Roberts N, Toloo GS. Exploring equity in cancer treatment, survivorship, and service utilisation for culturally and linguistically diverse migrant populations living in Queensland, Australia: a retrospective cohort study. International journal for equity in health. 2023;22(1):175-. [CrossRef]

- Foley K, Freeman T, Ward P, Lawler A, Osborne R, Fisher M. Exploring access to, use of and benefits from population-oriented digital health services in Australia. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(4):1105-15. [CrossRef]

- Ziebland S, Hyde E, Powell J. Power, paradox and pessimism: On the unintended consequences of digital health technologies in primary care. Soc Sci Med. 2021;289:114419-. [CrossRef]

- Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47-53. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s business--strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. 2007.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Physical therapy. 2009;89(9):873-80.

- Dai Z, Sezgin G, Hardie RA, McGuire P, Pearce C, McLeod A, et al. Sociodemographic determinants of telehealth utilisation in general practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Intern Med J. 2023;53(3):422-5. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin G, Dai Z, McLeod A, Pearce C, Georgiou A. Difference in general practice telehealth utilisation associated with birth country during COVID-19 from two Australian states. Ethics Med Public Health. 2023;27:100876. [CrossRef]

- Staples LG, Webb N, Asrianti L, Cross S, Rock D, Kayrouz R, et al. A Comparison of Self-Referral and Referral via Primary Care Providers, through Two Similar Digital Mental Health Services in Western Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2). [CrossRef]

- Estai M, Kruger E, Tennant M, Bunt S, Kanagasingam Y. Challenges in the uptake of telemedicine in dentistry. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(4):3915. [CrossRef]

- Baker AEZ, Procter NG, Ferguson MS. Engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse communities to reduce the impact of depression and anxiety: a narrative review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2016;24(4):386-98. [CrossRef]

- Bowden M, McCoy A, Reavley N. Suicidality and suicide prevention in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health. 2020;49(4):293-320. [CrossRef]

- Bradford NK, Caffery LJ, Smith AC. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(4):3808.

- Caffery LJ, Bradford NK, Wickramasinghe SI, Hayman N, Smith AC. Outcomes of using telehealth for the provision of healthcare to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(1):48-53. [CrossRef]

- Edelman A, Grundy J, Larkins S, Topp SM, Atkinson D, Patel B, et al. Health service delivery and workforce in northern Australia: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health. 2020;20(4):6168. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin BC, Zajdlewicz L, Stiller A, Johnston EA, Myers L, Aitken JF, et al. What are the post-treatment information needs of rural cancer survivors in Australia? A systematic literature review. Psychooncology. 2023;32(7):1001-12. [CrossRef]

- Luu B, Fox L, McVeigh MJ, Ravulo J. Effectively supporting Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) young people with their mental health and wellbeing - does this matter or exist in Australia? Social Work in Mental Health. 2023.

- O’Sullivan B, Couch D, Naik I. Using Mobile Phone Apps to Deliver Rural General Practitioner Services: Critical Review Using the Walkthrough Method. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(1):e30387. [CrossRef]

- Parker S, Prince A, Thomas L, Song H, Milosevic D, Harris MF. Electronic, mobile and telehealth tools for vulnerable patients with chronic disease: a systematic review and realist synthesis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e019192. [CrossRef]

- Sibthorpe B, Gardner K, Chan M, Dowden M, Sargent G, McAullay D. Impacts of continuous quality improvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander primary health care in Australia. J Health Organ Manag. 2018;32(4):545-71. [CrossRef]

- Carroll J, Butler-Henderson K. MyHealthRecord in Australian Primary Health Care: An Attitudinal Evaluation Study. J Med Syst. 2017;41(10):158. [CrossRef]

- Cheung JM, Menczel Schrire Z, Aji M, Rahimi M, Salomon H, Doggett I, et al. Embedding digital sleep health into primary care practice: A triangulation of perspectives from general practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231180970. [CrossRef]

- Fisher K, Tapley A, Ralston A, Davey A, Fielding A, van Driel M, et al. Video versus telephone for telehealth delivery: a cross-sectional study of Australian general practice trainees. Fam Pract. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Halcomb EJ, Ashley C, Dennis S, McInnes S, Morgan M, Zwar N, et al. Telehealth use in Australian primary healthcare during COVID-19: a cross-sectional descriptive survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e065478. [CrossRef]

- Jawad D, Taki S, Baur L, Rissel C, Mihrshahi S, Wen LM. Resources used and trusted regarding child health information by culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia: An online cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2023;177. [CrossRef]

- Buss VH, Varnfield M, Harris M, Barr M. Remotely Conducted App-Based Intervention for Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Risk Awareness and Prevention: Single-Group Feasibility Trial. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(3):e38469. [CrossRef]

- Lepre B, Job J, Martin Z, Kerrigan N, Jackson C. The Queensland Virtual Integrated Practice (VIP) partnership program pilot study: an Australian-first model of care to support rural general practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1183. [CrossRef]

- Power R, Ussher JM, Hawkey A, Missiakos O, Perz J, Ogunsiji O, et al. Co-designed, culturally tailored cervical screening education with migrant and refugee women in Australia: a feasibility study. Bmc Womens Health. 2022;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Taki S, Lymer S, Russell CG, Campbell K, Laws R, Ong KL, et al. Assessing User Engagement of an mHealth Intervention: Development and Implementation of the Growing Healthy App Engagement Index. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(6):e89. [CrossRef]

- Tiong SS, Koh ES, Delaney G, Lau A, Adams D, Bell V, et al. An e-health strategy to facilitate care of breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(2):181-7. [CrossRef]

- Australasian Telehealth Society. Telehealth and the NBN: A submission to the Australian House of Representatives Infrastructure and Communications Committee Inquiry into the role and potential benefits of the National Broadband Network 2011 Febuary.

- WA Country Health Service. Telehealth Awareness Week 2018. Government of Western Australia; 2018 25-29 June.

- Amanda R, Rana K, Saunders P, Tracy M, Bridges N, Poudel P, et al. Evaluation of the usability, content, readability and cultural appropriateness of online alcohol and other drugs resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e069756. [CrossRef]

- Lee KSK, Wilson S, Perry J, Room R, Callinan S, Assan R, et al. Developing a tablet computer-based application (’App’) to measure self-reported alcohol consumption in Indigenous Australians. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(1):8.

- Macnamara J, Camit M. Effective CALD community health communication through research and collaboration: an exemplar case study. Communication Research and Practice. 2017;3(1):92-112. [CrossRef]

- Osborn E, Ritha M, Macniven R, Agius T, Christie V, Finlayson H, et al. “No One Manages It; We Just Sign Them Up and Do It”: A Whole System Analysis of Access to Healthcare in One Remote Australian Community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5). [CrossRef]

- Parker SM, Barr M, Stocks N, Denney-Wilson E, Zwar N, Karnon J, et al. Preventing chronic disease in overweight and obese patients with low health literacy using eHealth and teamwork in primary healthcare (HeLP-GP): a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(11):e060393. [CrossRef]

- Bowden JL, Lamberts R, Hunter DJ, Melo LR, Mills K. Community-based online survey on seeking care and information for lower limb pain and injury in Australia: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e035030. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Johnson CE, Saunders C, Licqurish S, Chua D, Mitchell G, et al. Provision of end-of-life care in primary care: a survey of issues and outcomes in the Australian context. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e053535. [CrossRef]

- Green D, Russell DJ, Zhao Y, Mathew S, Fitts MS, Johnson R, et al. Evaluation of a new medical retrieval and primary health care advice model in Central Australia: Results of pre- and post-implementation surveys. Aust J Rural Health. 2023;31(2):322-35. [CrossRef]

- Page ZA, Croot K, Sachdev PS, Crawford JD, Lam BP, Brodaty H, et al. Comparison of Computerised and Pencil-and-Paper Neuropsychological Assessments in Older Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Australians. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2022;28(10):1050-63.

- Snoswell CL, Caffery LJ, Whitty JA, Soyer HP, Gordon LG. Cost-effectiveness of Skin Cancer Referral and Consultation Using Teledermoscopy in Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(6):694-700. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani AS, Sheikh M, Wiley K, Heywood AE. Australian Hajj pilgrims’ infection control beliefs and practices: Insight with implications for public health approaches. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13(4):329-34. [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi H, Mc Namara K, Browning C. Time to question diabetes self-management support for Arabic-speaking migrants: exploring a new model of care. Diabet Med. 2017;34(3):348-55. [CrossRef]

- Ayre J, Bonner C, Bramwell S, McClelland S, Jayaballa R, Maberly G, et al. Implications for GP endorsement of a diabetes app with patients from culturally diverse backgrounds: a qualitative study. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2020;26(1):52-7. [CrossRef]

- Carrigan A, Roberts N, Clay-Williams R, Hibbert P, Austin E, Pulido DF, et al. What do consumer and providers view as important for integrated care? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Easpaig BNG, Tran Y, Winata T, Lamprell K, Pulido DF, Arnolda G, et al. Providing outpatient cancer care for CALD patients: a qualitative study. Bmc Research Notes. 2021;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Field P, Franklin RC, Barker R, Ring I, Leggat PA. Cardiac rehabilitation in rural and remote areas of North Queensland: How well are we doing? Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30(4):488-500.

- Hughson JA, Marshall F, Daly JO, Woodward-Kron R, Hajek J, Story D. Health professionals’ views on health literacy issues for culturally and linguistically diverse women in maternity care: barriers, enablers and the need for an integrated approach. Australian Health Review. 2018;42(1):10-20.

- James S, Ashley C, Williams A, Desborough J, McInnes S, Calma K, et al. Experiences of Australian primary healthcare nurses in using telehealth during COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e049095. [CrossRef]

- Javanparast S, Roeger L, Kwok Y, Reed RL. The experience of Australian general practice patients at high risk of poor health outcomes with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):69. [CrossRef]

- Kearns R, Gardner K, Silveira M, Woodland L, Hua M, Katz M, et al. Shaping interventions to address waterpipe smoking in Arabic-speaking communities in Sydney, Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1379. [CrossRef]

- Mathew S, Fitts MS, Liddle Z, Bourke L, Campbell N, Murakami-Gold L, et al. Telehealth in remote Australia: a supplementary tool or an alternative model of care replacing face-to-face consultations? BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):341.

- McCulloch K, Murray K, Cassidy E. Bridging Across the Digital Divide: Identifying the Extent to Which LGBTIQ plus Health Service Websites Engage Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Users. Journal of Homosexuality. 2023;70(11):2395-417. [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan C, Dharmagesan GG, Roy J, Dharmagesan V, Loukas P, Harris-Roxas B. Enhancing equitable access to cancer information for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities to complement beliefs about cancer prognosis and treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(10):5957-65. [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan C, Tran A, Tam N, Wen LM, Harris R. Promoting the get healthy information and coaching service (GHS) in Australian-Chinese communities: facilitators and barriers. Health Promot Int. 2022;37(2). [CrossRef]

- O’Connor R, Slater K, Ball L, Jones A, Mitchell L, Rollo ME, et al. The tension between efficiency and effectiveness: a study of dietetic practice in primary care. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2019;32(2):259-66. [CrossRef]

- Pung A, Fletcher SL, Gunn JM. Mobile App Use by Primary Care Patients to Manage Their Depressive Symptoms: Qualitative Study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(9):e10035. [CrossRef]

- Seale H, Harris-Roxas B, Heywood A, Abdi I, Mahimbo A, Chauhan A, et al. Speaking COVID-19: supporting COVID-19 communication and engagement efforts with people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1257. [CrossRef]

- Seale H, Kaur R, Mahimbo A, MacIntyre CR, Zwar N, Smith M, et al. Improving the uptake of pre-travel health advice amongst migrant Australians: exploring the attitudes of primary care providers and migrant community groups. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:213. [CrossRef]

- Song HJ, Dennis S, Levesque JF, Harris MF. What matters to people with chronic conditions when accessing care in Australian general practice? A qualitative study of patient, carer, and provider perspectives. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):79. [CrossRef]

- Tan MS, Patel BK, Roughead EE, Ward M, Reuter SE, Roberts G, et al. Opportunities for clinical decision support targeting medication safety in remote primary care management of chronic kidney disease: A qualitative study in Northern Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 2023:1357633x231204545. [CrossRef]

- Toll K, Spark L, Neo B, Norman R, Elliott S, Wells L, et al. Consumer preferences, experiences, and attitudes towards telehealth: Qualitative evidence from Australia. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273935. [CrossRef]

- Watson MJG, McCluskey PJ, Grigg JR, Kanagasingam Y, Daire J, Estai M. Barriers and facilitators to diabetic retinopathy screening within Australian primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):239.

- Mistry SK, Harris E, Harris MF. Learning from a codesign exercise aimed at developing a navigation intervention in the general practice setting. Family Practice. 2022;39(6):1070-9.

- True A, Janamian T, Dawda P, Johnson T, Smith G. Lessons from the implementation of the Health Care Homes program. Med J Aust. 2022;216 Suppl 10(Suppl 10):S19-s21. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S, Agarwal S, Glenton C, Henschke N, Tamrat T, Bergman H, et al. Tracking health commodity inventory and notifying stock levels via mobile devices: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2020(10):CD012907-CD. [CrossRef]

- Lall P, Rees R, Law GCY, Dunleavy G, Cotič Ž, Car J. Influences on the implementation of mobile learning for medical and nursing education: Qualitative systematic review by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e12895-e. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead L, Talevski J, Fatehi F, Beauchamp A. Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations: Qualitative Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25(1):e42719-e. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez C, Early J, Gordon-Dseagu V, Mata T, Nieto C. Promoting Culturally Tailored mHealth: A Scoping Review of Mobile Health Interventions in Latinx Communities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23(5):1065-77. [CrossRef]

- Radu I, Scheermesser M, Spiess MR, Schulze C, Händler-Schuster D, Pehlke-Milde J. Digital Health for Migrants, Ethnic and Cultural Minorities and the Role of Participatory Development: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023;20(20):6962. [CrossRef]

- Botfield JR, Newman CE, Lenette C, Albury K, Zwi AB. Using digital storytelling to promote the sexual health and well-being of migrant and refugee young people: A scoping review. Health education journal. 2018;77(7):735-48.

- Gallegos-Rejas VM, Kelly JT, Lucas K, Snoswell CL, Haydon HM, Pager S, et al. A cross-sectional study exploring equity of access to telehealth in culturally and linguistically diverse communities in a major health service. Australian health review. 2023;47(6):721-8. [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Rejas VM, Kelly JT, Snoswell CL, Haydon HM, Banbury A, Thomas EE, et al. Does the requirement for an interpreter impact experience with telehealth modalities, acceptability and trust in telehealth? Results from a national survey including people requiring interpreter services. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2023;29(10_suppl):24S-9S. [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs DH, Kretzer MM, Davis EE. Mapping the online language ecology of multilingual COVID-19 public health information in Australia. European journal of language policy. 2022;14(2):133-62. [CrossRef]

- Freyne J, Bradford D, Pocock C, Silvera-Tawil D, Harrap K, Brinkmann S. Developing digital facilitation of assessments in the absence of an interpreter: Participatory design and feasibility evaluation with allied health groups. JMIR Form Res. 2018;20(1):e1-e. [CrossRef]

- Hwang K, Williams S, Zucchi E, Chong TWH, Mascitti-Meuter M, LoGiudice D, et al. Testing the use of translation apps to overcome everyday healthcare communication in Australian aged-care hospital wards—An exploratory study. Nurs Open. 2022;9(1):578-85. [CrossRef]

- Beh THK, Canty DJ. English and Mandarin translation using Google Translate software for pre-anaesthetic consultation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43(6):792-3.

- Panayiotou A, Gardner A, Williams S, Zucchi E, Mascitti-Meuter M, Goh AMY, et al. Language translation apps in health care settings: Expert opinion. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(4):e11316-e. [CrossRef]

- Koh A, Swanepoel DW, Ling A, Ho BL, Tan SY, Lim J. Digital health promotion: promise and peril. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(Supplement_1):i70-i80. [CrossRef]

- Walker J. ‘It keeps dropping out!’: The need to address the ongoing digital divide to achieve improved health and well-being benefits for older rural Australians. Australas J Ageing. 2017;36(4):262-3. [CrossRef]

- Warr D, Luscombe G, Couch D. Hype, evidence gaps and digital divides: Telehealth blind spots in rural Australia. Health (London). 2023;27(4):588-606. [CrossRef]

| Health System Building Blocks (Number of Relevant Studies) | Populations (Number of Relevant Studies) |

Successes | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and stewardship for health systems [3] | General [3] | n/a | 1. The overall health governance was fragmented [49]. 2. Lack of transparency and consistency across policies [58]. 3. lack of regulatory control over information on the online platform [56]. |

| First Nations peoples [1] | n/a | 1. First Nations peoples’ health problems have not been addressed at a national level [49]. | |

| CALD [1] | n/a | 1. lack of regulatory control over information on the online platform [56]. | |

| Health workforce [6] | General [4] | 1. Online training has been implemented [57]. 2. DHIs could help overcome staff shortages [40]. 3. Skill improvements in using DHIs stimulated by Covid-19 [40]. |

1. Current funding for health workers could not satisfy the extra needs brought by DHIs [68]. 2. No appropriate technology to use [40,68]. 3. Training affordability and extra workload [40]. 4. Hard to establish familiarity with new technologies [68,82]. |

| First Nations peoples [2] | 1. Enable vulnerable health workers access to patients during the COVID-19 [71]. | 1. Inadequate rural health workforce [33,71]. 2. Extra workload and low translation skills [71]. |

|

| Health Information System [7] | General [4] | 1. Current HIS improved efficiency and expanded the data source [27,75]. 2. Current HIS increased the accessibility for both patients and healthcare providers [39]. |

1. Real-time sharing of health information function was unavailable in some areas [57]. 2. Some disadvantaged patients could not access some HIS [39]. |

| First Nations peoples [3] | 1. Current HIS ensures healthcare providers access good quality data [38,80]. 2. Substantial improvements in providing PHC have been led [33]. |

1. The lack of connectivity between HISs across different services is challenging [33]. 2. Staff perceived difficulties in operating the HIS, then caused negative results [80]. 3. Inappropriate tools are used in operating HIS [38]. 4. Updating the current HIS is difficult [38]. |

|

| Medicine, Vaccines, diagnostics and technologies [14] | General [3] | 1. Some technologies were considered to assist clinical practice [75]. | 1. Low affordability of technologies for some healthcare providers or patients [41,82] |

| First Nations peoples [4] | n/a | 1. low accessibility and utilisation of telehealth hardware [49,66,71]. 2. The system-level uptake of telehealth technologies is slow [49]. 3. In rural areas, the quality of some current technologies is low [80] 4. Some technologies do not have some essential functions [66]. 5. Current technologies seldom specialised for clinical purposes [49]. |

|

| CALD [7] | 1. Current mental diagnosis delivered by DHIs is more accurate and stable [59]. | 1. Low availability or low quality of hardware devices to apply DHIs [35,46,63,64,77,81]. | |

| Health service delivery [51] | General [15] | 1. DHIs increased the overall efficiency of PHC delivery [28,58,60,75]. 2. DHIs improved patients’ access to PHC, especially for disadvantaged patients or those in the COVID-19 context [27,50,69]. 3. DHIs have good coordination with other levels of care and organisations [50,58,69]. 4. DHIs could support a wide range of health services, indicating high comprehensiveness [27,37]. 5. The use of DHIs in rural/remote Australia is increasing [31]. 6. Patients received quality PHC delivered by DHIs [27,50,76,84]. |

1. DHIs could only be tools to support treatments [76]. 2. The utilisation of more effective DHIs is low [41] 3. For elderly patients, the utilisation of DHIs is low [44]. 4. DHIs presented ineffectiveness in some PHC areas [44,47,68]. 5. Concerns raised on DHIs due to the fear of addiction [76]. |

| First Nations peoples [6] | 1. DHIs improved rural access to PHCs [36,45,80]. 2. Another DHI improved the quality-of-service delivery [45,51]. 3. Online resources were widely used [34]. 4. DHIs improved First Nations peoples’ efficiency in accessing PHC services [71]. |

1. DHIs could not cover some emergency care [12]. 2. Challenges in accessibility caused by language or knowledge barriers still exist [51,71]. 3. The utilisation and independence of DHIs are low [54,71]. |

|

| CALD [22] | 1. DHIs successfully improved the efficiency of health service delivery [81]. 2. The overall access to health services was improved [29,42,48,78,79,81] 3. DHIs contributed to the success of health communication programs [46,53]. 4. Current DHIs were helpful in assisting administrative work [79]. 5. Except for searching for health information [56], the utilisation of DHIs among CALD people is low [25]. 6. DHIs can help CALD people overcome the language barrier [43]. 7. Characteristics of DHI, including privateness and confidentiality, showed high person-centeredness [29]. 8. Some online health education programs gained acceptance from CALD communities [43,70]. |

1. Technical difficulties became barriers to accessibility [48] 2. Language barrier still exists [42]. 3. DHIs could be low-quality or ineffective in multiple situations [42,55,56,64,81]. 4. The low translation quality is especially critical for CALD people [63,67]. 5. Low-quality online health information caused negative effects [43,61,83]. 6. Due to problems with interpreters or English sources of online health information in the predominant position, the language barrier has not been completely overcome [26,43,65,74,77] 7. There is a challenging trend of DHI utilisation in CALD communities [26,62,83]. 8. Some CALD communities with high health demands have been ignored [77]. |

|

| Community engagement [10] | First Nations peoples [5] | 1. However, some successful community engagement has been achieved by DHIs tailored for First Nations peoples [32,51,52]. | 1. Digital GP apps are designed in a way that is against community values and reduces community involvement [36]. 2. The coordination with different social groups needed to be improved [66]. |

| First Nations peoples [6] | 1. Successes in involvement and empowerment were emphasised on a tailored program [46]. 2. Social media apps provided a platform to cooperate with local community leaders [77]. |

1. Some DHIs failed to satisfy the cultural needs of CALD people [30,63,72]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).